Submitted:

19 July 2024

Posted:

22 July 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

Methods

Participants

Instrument

- -

- Three control scales to assess possible response biases (inconsistency, negative impression, and positive impression)

- -

- Scales of emotional and behavioural problems, divided into four different blocks:

- -

- Internalized, predominantly emotional problems, such as depression, anxiety, social anxiety, somatic complaints, obsession-compulsion, and post-traumatic symptomatology.

- -

- Externalized problems, disruptive behaviours, such as hyperactivity and impulsivity, attention deficit, aggressiveness, defiant behaviour, anger management problem, antisocial behaviour.

- -

- Contextual problems (problems with family, problems with school, and problems with peers).

- -

- Specific problems (developmental delay, eating disorders, learning disabilities, schizophrenia, substance use, ...)

- -

- Vulnerability scales that evaluate a more severe problem, such as emotional regulation problems and sensation seeking.

- -

- Scales of protective psychological resources in the face of different problems, such as: self-esteem, integration and social competence and awareness of problems.

Data Collection

Statistical Procedure

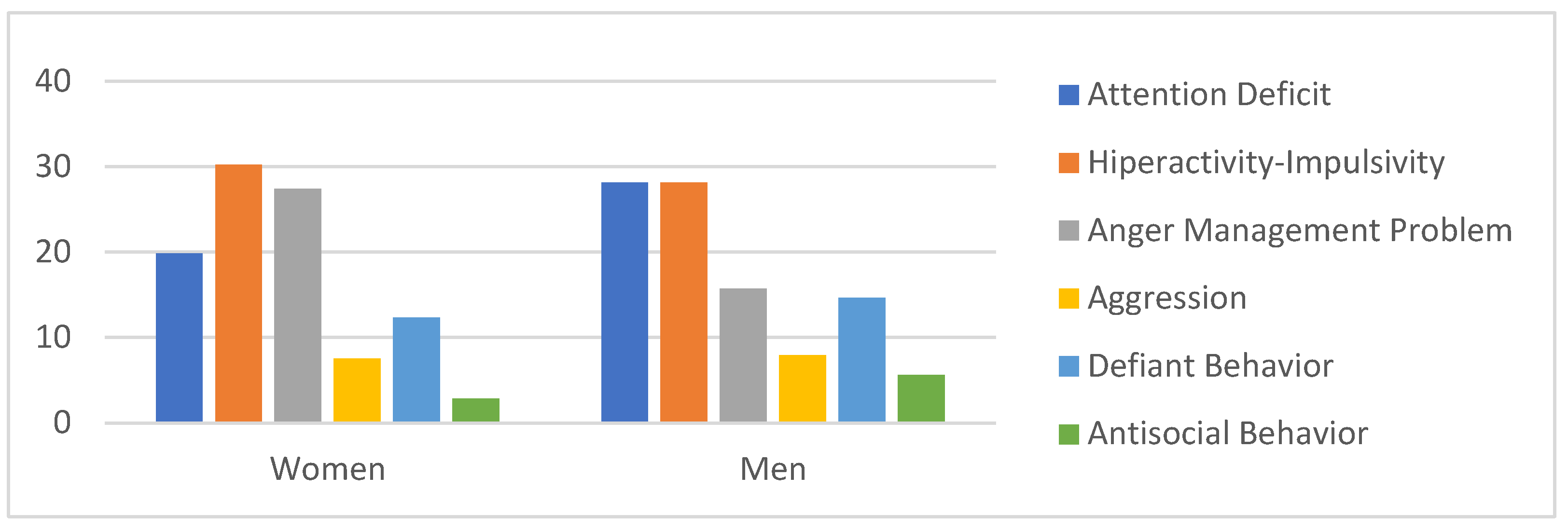

3. Results

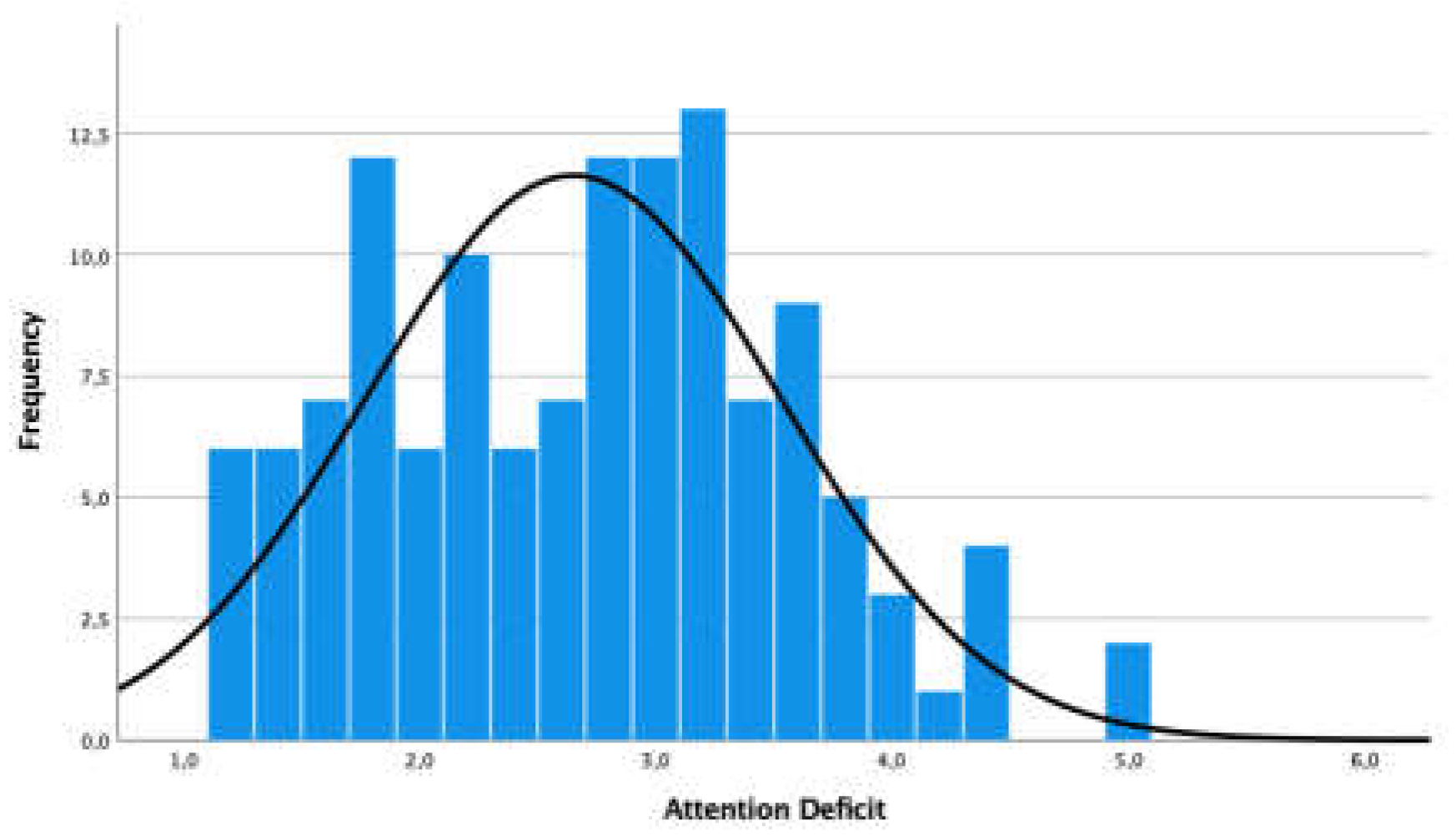

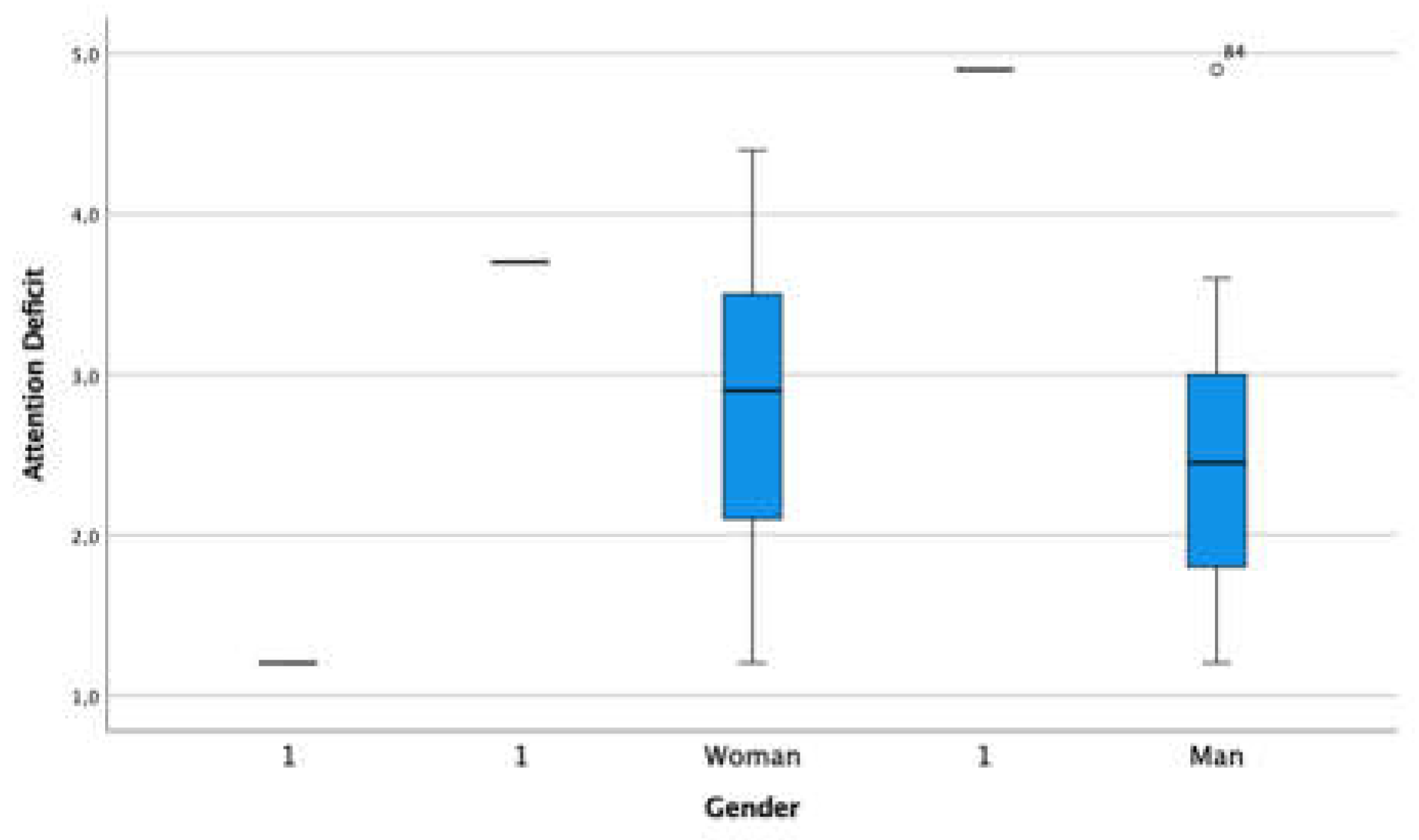

3.1. Externalized Problem - Attention Deficit

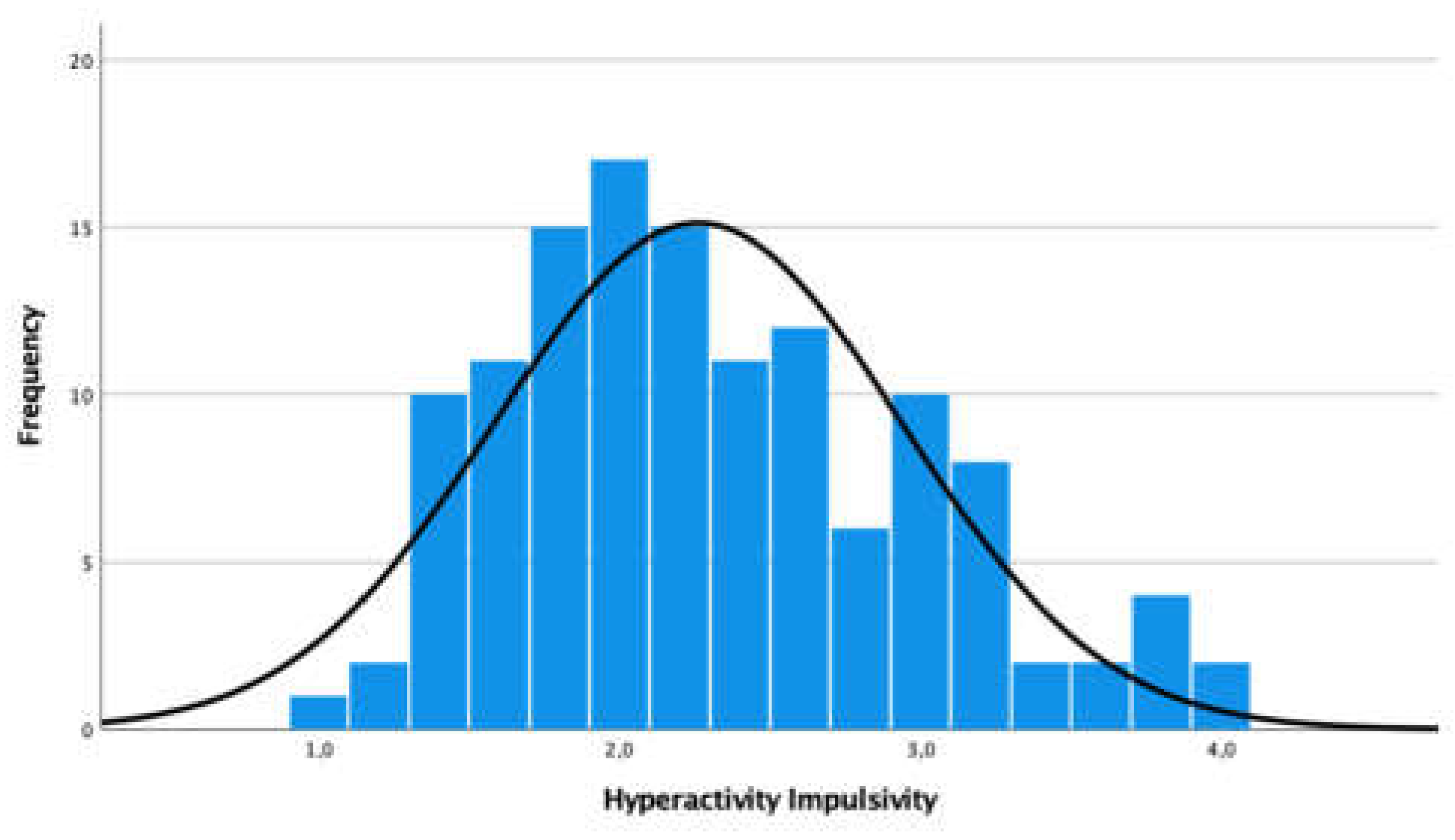

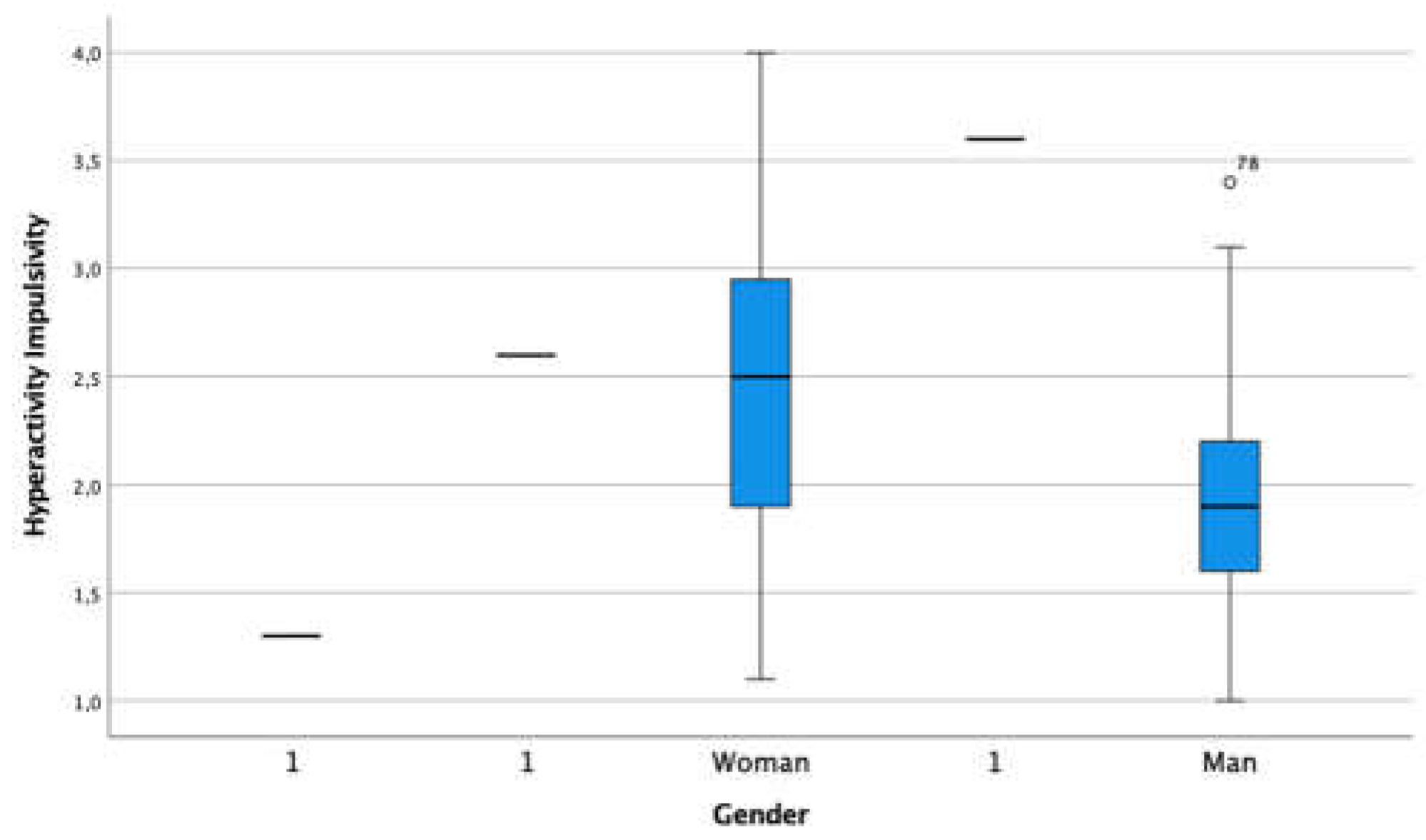

3.2. Externalized Problem - Hyperactivity- Impulsivity

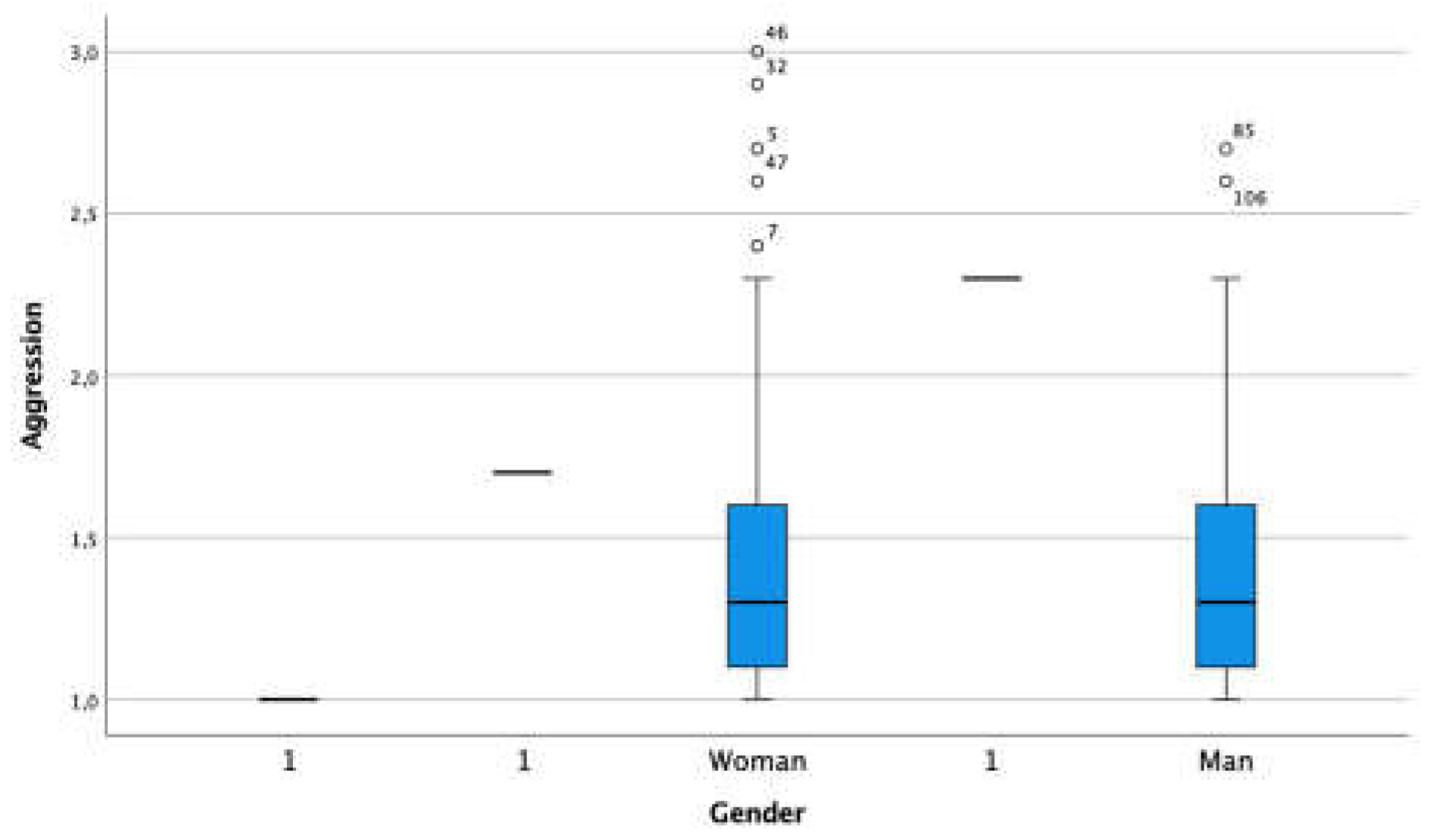

3.3. Externalized Problem - Aggression

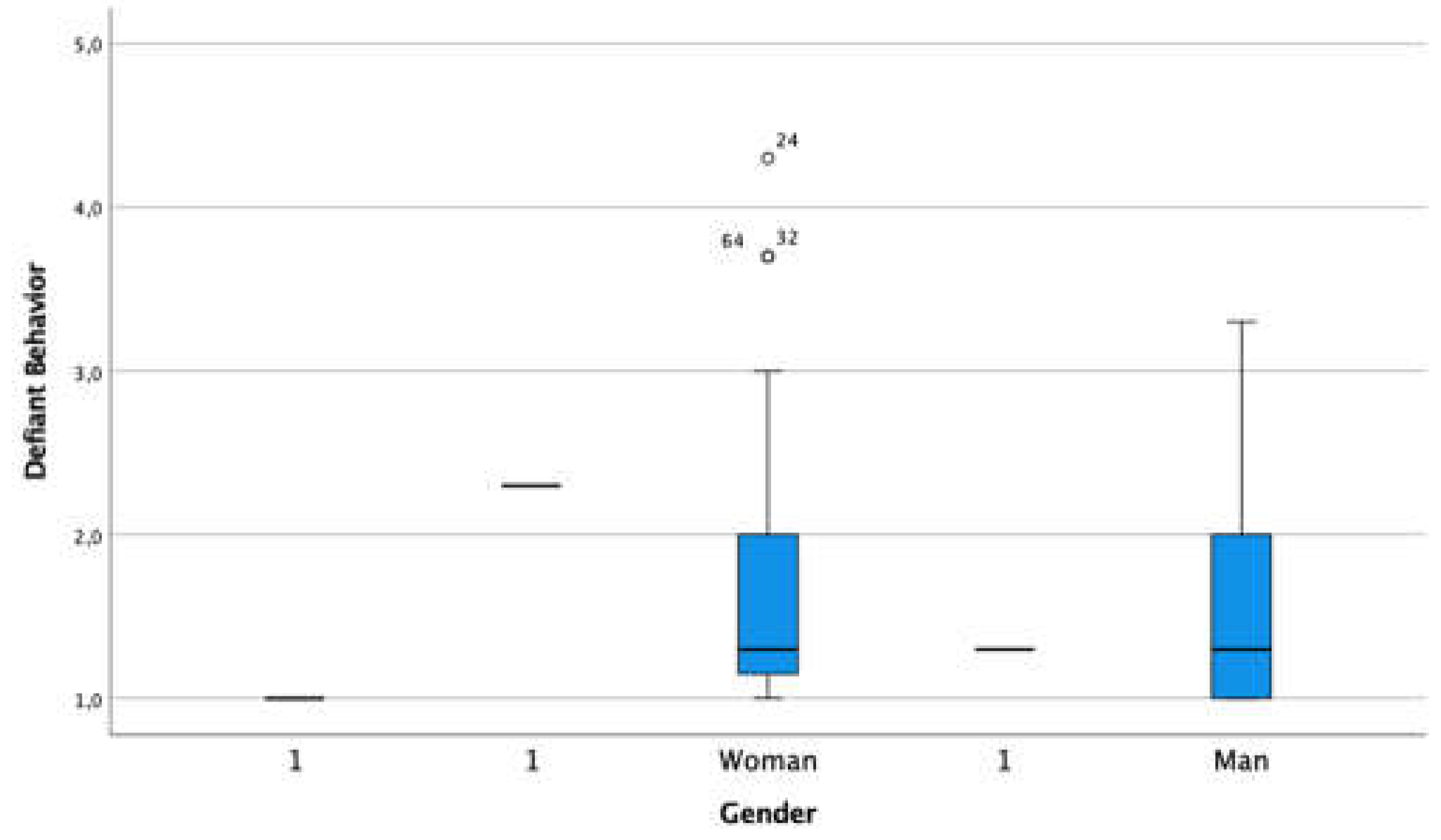

3.4. Externalized Problem 4- Defiant Behaviour

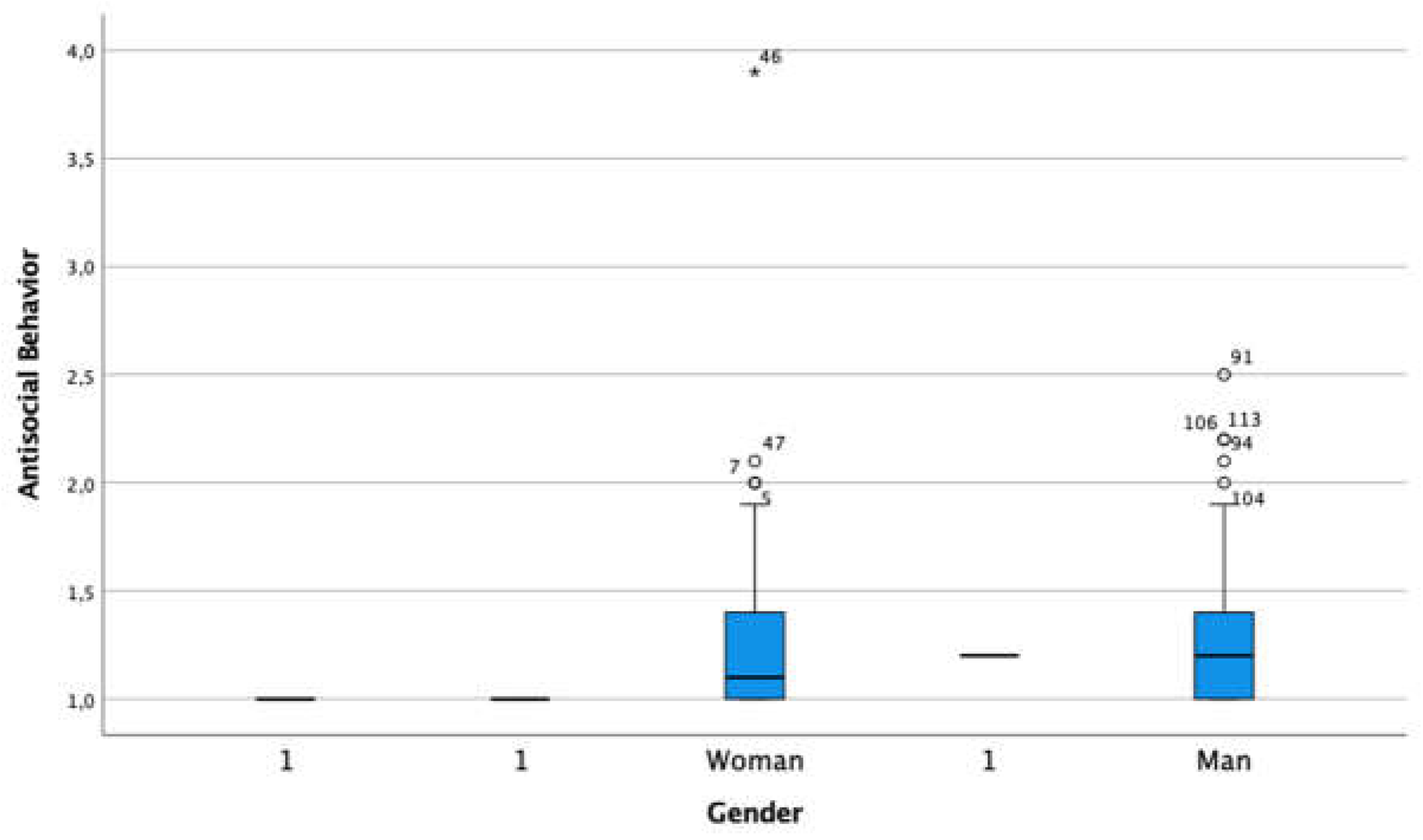

3.5. Externalized Problem - Antisocial Behaviour

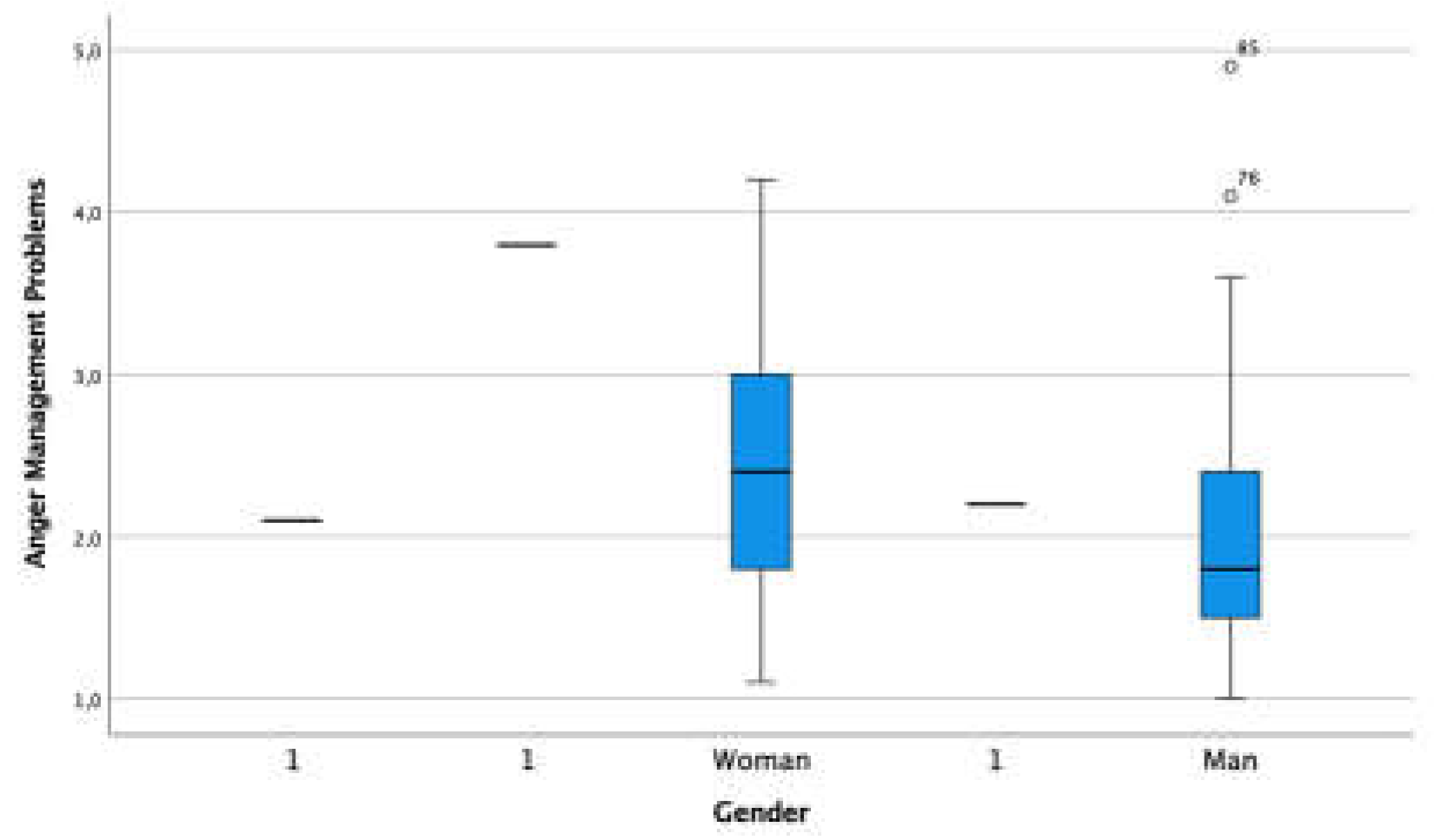

3.6. Externalized Problem - Anger Management Problem

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Alaka Mani, T.L.; Sharma, M.K.; Omkar, S.N.; Nagendra, H.R. Holistic assessment of anger in adolescents–Development of a rating scale. Journal of Ayurveda and Integrative Medicine 2018, 9, 195–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- David, M.; Mason, R.A.; Davis, J.L.; Gregori, E.; Lei, Q.; Lory, C.; Wang, D. School-Based Interventions Targeting Challenging Behavior of Adolescents with Developmental Disabilities: A Meta-Analysis. Journal of Developmental and Physical Disabilities 2023, 35, 17–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caamaño-Navarrete, F.; Del-Cuerpo, I.; Arriagada-Hernández, C.; Alvarez, C.; Gaya, A.R.; Reuter, C.P.; Delgado-Floody, P. Association between Active Commuting and Lifestyle Parameters with Mental Health Problems in Chilean Children and Adolescent. Behav. Sci. 2024, 14, 554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, O.L.K.; Bann, D.; Patalay, P. The gender gap in adolescent mental health: A cross-national investigation of 566,829 adolescents across 73 countries. SSM - Population Health 2021, 13, 100742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuadra, A.; Veloso, C.; Vega, G.; Zepeda, A. Ideación Suicida Y relación con la Salud Mental en Adolescentes Escolarizados no Consultantes. Redalyc 2021, 46, 217–223. [Google Scholar]

- Eddy, L.S. Behavioral disorders. Journal of Continuing Education of the Spanish Society of Adolescent Medicine 2020, VIII. [Google Scholar]

- Eysenk, S.B.; Eysenk, H.J. The place of impulsiveness in a dimensional system of personality description. Br J Soc Clin Psychol 1977, 16, 57–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Estevez, E.; Emler, N.P.; Cava, M.J.; Inglés, C.J. Ajuste psicosocial en adolescentes populares agresivos y rechazados agresivos en el colegio. Psychosocial Adjustment in Aggressive Popular and Aggressive Rejected Adolescents at School. Psychosocial Intervention 2014, 23, 57–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández, M.; Fernández Parra, A. Behavioral problems, emotional problems, and care problems in children and adolescents living in residential care. Psychology 2017, 11, 57–70. [Google Scholar]

- Gallardo-Saavedra, G.A.; Martínez-Wbaldo, M.d.C.; Padrón-García, A.L. Prevalence of ADHD in Mexican schoolchildren through screening with the Conners 3 scales. Actas Esp Psiquiatr 2019, 47, 45–53. [Google Scholar]

- Garcia, L.; Quintana, O.C.; Rey, L. Cybervictimization and life satisfaction in adolescents: Emotional intelligence as a mediating variable. Journal of Clinical Psychology with Children and Adolescents 2020, 7, 38–45. [Google Scholar]

- Kreuze, L.J.; de Jong, P.J.; Bennik, E.C.; Nauta, M.H. Anger Responses in Adolescents: Relationship with Punishment and Reward Sensitivity. Child Psychiatry and Human Development 2022, 53, 1174–1185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Øen, K.; Johan Krumsvik, R. Teachers’ attitudes to inclusion regarding challenging behaviour. European Journal of Special Needs Education 2022, 37, 417–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, J.; Hadwin, J.A. The roles of sex and gender in child and adolescent mental health. JCPP Advances 2022, 2, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mateu, A.; Pascual, A.; Martínez, M.; Hickey, N.; Nicholls, D.; Kramer, T.; Schäfer, M. Salud mental en adolescentes víctimas y/o agresores de ciberbullying. Revista de Psicopatología y Salud Mental Del Niño y Del Adolescente 2021, 33, 43–58. [Google Scholar]

- Merchán Clavellino, A.; Martínez García, C.; Medina Mesa, Y.; Cruces Montes, S.J. Predictive model of emotional intelligence and impulsivity traits in sensation-seeking in young university students: A gender comparison. International Journal of Developmental and Educational Psychology: INFAD. Journal of Psychology 2019, 5, 291–300. [Google Scholar]

- Paredes, I.M.C.; Patiño, G.L.A. Health risk behaviors in adolescents. University and Health 2020, 22, 58–69. [Google Scholar]

- Ramírez, C.; Arcila, W. Violence, conflict and aggressiveness in the school setting. Education and Educator 2013, 16, 411–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramos Brieva, A.; Ramón y Cajal, G.-Z. Impulse Control Scale. Bank of Mental Health Instruments and Methodologies. 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Romero, E.; Gómez, F.X.A.; Villar, P.; Rodríguez, R. Indicated prevention of behavioral problems: Training of social-emotional skills in the school context. Journal of Clinical Psychology with Children and Adolescents 2019, 6, 39–47. [Google Scholar]

- Tabares, A.; Núñez, C.; Osorio, M.P.; Aguirre, A. Risk and Suicidal Ideation and its Relationship with Impulsivity and Depression in School-Age Adolescents. Ibero-American Journal of Diagnosis and Psychological Evaluation 2020, 54, 147–163. [Google Scholar]

- Vidal, A.; Matamala, M. Child and adolescent asthma and psychiatric disorders. Chilean Journal of Respiratory Diseases 2013, 29, 14–23. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. Adolescent Mental Health; WHO: Geneva, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Gámez, G.M.; Almendros, C.; Rodríguez, M.L.; Mateos, P.E. Online self-harm among Spanish adolescents: Analysis of prevalence and motivations. Journal of Clinical Psychology with Children and Adolescents 2020, 7, 9–15. [Google Scholar]

- Martinez, J. Child Development: A Review. Revista investigaciones Andina 2014, 29, 1118–1137. [Google Scholar]

- Marco, S.S.; Mayoral, A.M.; Valencia, A.F.; Roldán, D.L.; Espliego, F.A.; Delgado, L.C.; Hervás, T.G. Family Functioning in Adolescents at Risk for Suicide with Suicidal Traits. Revista de Psicología Clínica con Niños y Adolescentes 2020, 7, 50–55. [Google Scholar]

- Mestre, V.; Samper, P.; Tur-Porcar, A.M. Aggression in Adolescence. Univesrsitas Psychologica 2012, 11, 1263–1275. [Google Scholar]

- Patrón, R.; Limiñana, R.M. Victims of Family Violence: Psychological Consequences in Children of Abused Mothers. Annals of Psychology 2005, 21, 11–17. [Google Scholar]

- Hojjat, S.K.; Rezaei, M.; Namadian, G.; Hatami, S.E.; Norozi Khalili, M. Effectiveness of Emotional Intelligence Group Training on Anger in Adolescents with Substance-Abusing Fathers. Journal of Child and Adolescent Substance Abuse 2017, 26, 24–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Li, W.; Gao, L.; Wang, X. How is Trait Anger Related to Adolescents’ Cyberbullying Perpetration? A Moderated Mediation Analysis. Journal of Interpersonal Violence 2022, 37, 9–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Institute of Health Metrics and Evaluation Global Health Data Exchange 2021.

- Crespo, F.; Sánchez, C. Impacto del Trastorno Mental Grave en el ámbito educativo de niños y adolescentes. Revista Complutense de Educación 2019, 30, 205–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Directorate-General for Territorial Coordination and Deconcentration. Informe de Progreso 2022. 2022.

- Férnandez- Pinto, I.; Santamaría, P.; Sánchez-Sánchez, F.; Carrasco-Ortiz, M.A.; del Barrio-Gándara, V. SENA: Sistema de Evaluación de Niños y Adolescentes-Manual Técnico. TEA. 2015.

- Council of International Organizations. Pautas éticas internacionales para la investigación relacionada con la salud con seres humanos. Consejo de Organizaciones Internacionales de las Ciencias Médicas (CIOMS) en colaboración con la Organización Mundial de la Salud. 2022.

- Merchán Clavellino, A.; Martínez García, C.; Medina Mesa, Y.; Cruces Montes, S.J. Modelo predictivo de la inteligencia emocional y rasgos de impulsividad en la búsqueda de sensaciones en jóvenes universitarios: Una comparación de género. International Journal of Developmental and Educational Psychology: INFAD. Revista de Psicología 2019, 5, 291–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herdoiza-Arroyo, P.; Chóliz, M. Impulsividad en la Adolescencia: Utilización de una Versión Breve del Cuestionario UPPS en una Muestra de Jóvenes Latinoamericanos y Españoles. Revista Iberoamericana de Diagnóstico y Evaluación - e Avaliação Psicológica 2019, 1, 123–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallardo-Saavedra, G.A.; Martínez-Wbaldo, M.d.C.; Padrón-García, A.L. Prevalencia de TDAH en escolares mexicanos a través de un cribado con las escalas de Conners 3. Actas Esp Psiquiatr 2019, 47, 45–53. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Tabares, A.; Núñez, C.; Osorio, M.P.; Aguirre, A. Riesgo e Ideación Suicida y su Relación con la Impulsividad y la Depresión en Adolescentes Escolares. Revista Iberoamericana de Diagnóstico y Evaluacion Psicologica 2020, 54, 147–163. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, J.; Li, W.; Gao, L.; Wang, X. How is Trait Anger Related to Adolescents’ Cyberbullying Perpetration? A Moderated Mediation Analysis. Journal of Interpersonal Violence 2022, 37, 9–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patterson, G.R.; DeGarmo, D.S.; Knutson, N. Hyperactive and antisocial behaviors: Comorbid or two points in the same process? Development and Psychopathology 2000, 12, 91–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Children’s Age Female Group | Frequency | Percentage | Accumulative Percentage |

| 12 | 13 | 10.2 | 10.2 |

| 13 | 21 | 16.4 | 26.6 |

| 14 | 15 | 11.7 | 38.3 |

| 15 | 17 | 13.3 | 51.6 |

| 16 | 1 | 0.8 | 52.3 |

| Children’s Age Male Group | Frequency | Percentage | Accumulative Percentage |

| 12 | 9 | 7 | 7 |

| 13 | 13 | 10.2 | 17.2 |

| 14 | 13 | 10.2 | 27.4 |

| 15 | 21 | 16.4 | 43.8 |

| 16 | 2 | 1.6 | 45.4 |

| N | Mean | Standard deviation | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Attention Deficit | 128 | 2.65 | .88 |

| Hyperactivity-Impulsivity | 128 | 2.26 | .68 |

| Aggression | 128 | 1.43 | .45 |

| Challenging conduct | 128 | 1.63 | .67 |

| Antisocial behavior | 128 | 1.28 | .41 |

| Anger Management Problems |

128 | 2.27 | .85 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).