1. Introduction

The development of neuropsychological assessments began primarily in Western countries, and as a result, assessment tools are often founded on a mono-cultural concept. When these tools are applied overseas or to non-Western populations, they do not always function as designed. Few studies have explored the interactions between language, culture, and cognitive processes related to neuropsychological assessments [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5,

6,

7,

8,

9,

10,

11,

12,

13,

14,

15,

16]. This study clarifies the relationship between plausibility concerning cognitive function assessment content and related language and cultural backgrounds. It reveals significant misalignments and considerations that should be accounted for when using assessment tools in a cross-linguistic or cross-cultural clinical setting. In addition, the use of cognitive behavioral therapy is considered. The literature in this field can be divided into six general research perspectives, which are presented along with their findings: (1) Studies involving clinical assessment and diagnosis of cognitive functioning and cognitive change with respect to multiple languages and cultures, including both single and comparative case studies and more extensive sample size studies, for digital and non-digital neuropsychological assessments; [

1,

2,

3,

4,

12,

17,

18] (2) validation studies for adapting tools to language-specific or culture-specific assessments; [

6,

7,

13,

14,

19,

20] (3) qualitative research on neuropsychological assessment, covering methods for cognitive function assessments, oral history or cultural memory for clinical condition evaluation, and intercultural research on the content and administration of cognitive tools in clinical research or everyday settings; [

4,

9,

10,

11,

21,

22] (4) the development and design of cognitive function assessments and experiment procedures considering indigenous needs for medical resources; [

12,

23,

24] (5) theoretical papers and guidelines on the need to identify future direction and ethical considerations; [

15,

25] and (6) practice session papers, including studies reporting the development of digital app-based tools [

16,

26].

2. Literature Review

Several major debates on cross-cultural methodology have developed in recent years. These debates can be grouped into two points of view. The first perspective believes cultural groups should be examined separately, using the traditional single-group approach. The second perspective emphasizes the equivalence of psychological measurements across cultural comparative studies. Researchers supporting the equivalence approach put more emphasis on measuring the psychological test. They claim it is very important to ensure equivalent measurements of the psychological test because it will affect group comparison, interpretation, and the direct application of the psychological test across different cultural groups [

27,

28,

29].

Neuropsychological assessment is a focus of attention regarding differences in cognitive functioning across cultures. There are two main reasons for this. The first reason is driven by clinical efforts to address the unique needs of minority and indigenous language groups. Culturally sensitive clinical methods increase the likelihood that individuals from diverse backgrounds are accurately identified as potentially impaired in their cognitive abilities. The second reason is driven by research attempting to examine the effects of culture on neuropsychological functioning or whether different complex patterns of cognitive-behavioral functions are shared by individuals from the same cultural background [

30,

31].

In psychology, psychological tests are valuable methods to measure psychological constructs in people's lives. However, when a psychological test developed in one culture is used with a different culture, it is necessary to conduct research to examine whether the psychological test is the same or equivalent across cultures. This process is called cross-cultural validation [

32].

2.1. Importance of Cross-Cultural Validation

Different cultures develop different languages and communication patterns that may engage brain areas in different ways. The ways communication affects the way culture develops also involve animated components, including behaviors and gestures. They depend largely on and are influenced by the environment and vary over time as the environment changes. Brain changes derive from this bidirectional phenomenon, reflecting on cognitive skills that vary among specific groups, cultures, and countries. One example is language. Neuropsychological tests that assess cognitive, emotional, and social function, however, become relevant in the development of cognitive maps of the world when broader capabilities, knowledge, and strategies are required to negotiate social realities between different cultural communities. Cross-cultural validation studies are then inevitable to ensure data accuracy and fairness in such assessments. This procedure points out possible biases or discrepancies in the measurements. It thus provides an avenue for adjustment to be made so that the measures are applicable and reliable across different cultural groups. The validation process also ensures that using such measures, there will be an accurate assessment of culturally diverse subjects' cognitive and neuropsychological functions. This is crucial for ensuring measures apply across and are effective in these different cultural groups.

Moreover, it helps deal with possible biases in assessments and promotes the accuracy of the results. This becomes of the essence, especially when dealing with a diverse population, since cultural differences may significantly affect the assessments' competence [

33,

34,

35].

The activity of neuropsychology is related to the brain-behavior link because significant actions and effects on the environment are in the cognitive domain. Since culture defines a particular society's behaviors, norms, and values, it becomes essential to consider the potential effect of cultural variables when designing and administering neuropsychological tests. The understanding of the human mind as the result of ecological adaptiveness is a specific gift of the field of neuropsychology, as it can validate neurobiological explanations. Neuropsychology, in fact, investigates the neural bases of several human behaviors sedimented on evolutionary foundations, giving reasons why the brain is functional in so many different activities. This is particularly important when considering the diverse cultural contexts in which these assessments are used. It is essential to ensure that the assessments are culturally appropriate and relevant for the populations being served [

36,

37].

2.2. Cross-Cultural Considerations in Neuropsychological Assessment

The main purpose of the neuropsychological assessment is to identify a potential cognitive impairment and to quantify neuropsychological function across different domains concerning concern for different etiologies, among others. The key principle of a cross-cultural psychological assessment is to understand how the cultural background of the client influences his or her behavior, emotional state, and psychological needs and to adjust to find the best possible way to evaluate mental status and functions. Commissioned by the Psychological Assessment of Racial and Ethnic Minority, for psychological assessment, although norm generation and cultural adaptation are desirable and, in some cases, essential, historically, it has been equally important to acknowledge and avoid negative consequences from racism and ethnocentrism which are prevalent in the classification of neuropsychological function. Cross-cultural validation is crucial for ensuring the reliability and validity of neuropsychological assessments in diverse populations. It is important to consider cultural factors that may influence the interpretation of test results and the development of assessment tools. In particular, language barriers and differences in educational and occupational background can impact test performance. Therefore, it is crucial for neuropsychological assessments to be validated across different cultural and linguistic groups to ensure their accuracy and effectiveness in cognitive behavioral therapy [

38,

39,

40,

41].

Much attention has been given to the development of normative standards for neuropsychological tests that adequately correct for normal age-related changes in cognitive function. However, the contribution of cross-cultural influences is less well understood. Even within the domains in which a particular test is most reliant, it may be possible that this tool is not equally sensitive across different populations. Currently, neuropsychological tests are well reviewed in terms of examining emotion-related and basic cognitive abilities, and their underlying structure and implications for measuring therapeutic change [

42]. Despite recent interest in this topic, limited research and recommendations are available for tests of neuropsychological function. Differences in mean test performance between different cultural populations have been described across a range of neuropsychological and intelligence tests. These differences highlight the importance of culturally sensitive assessment techniques and the need for cross-cultural validation studies. In addition, understanding cultural factors that may impact performance on neuropsychological assessments is crucial for accurate diagnosis and effective treatment planning. It is important to consider cultural differences in cognitive processes and behaviors when interpreting neuropsychological test results [

38,

39,

43,

44,

45,

46].

2.3. Cognitive Behavioral Therapy: Principles and Applications

Cognitive behavioral therapy has been recognized as an evidence-based treatment for various psychiatric disorders. Developed from core elements such as behavioral activation and social learning theory, cognitive behavioral therapy is designed to be adjusted when applied in diverse cultural contexts. As cognitive behavioral therapy continues to exhibit the potential for treating broad populations, studies addressing cross-cultural issues in cognitive behavioral therapy are scarce, and the usage of cross-culturally validated neuropsychological assessments remains infrequent. This potentially limits the reliability of cognitive behavioral therapy provided to the respective individuals, especially when cognitive interventions for cognitive skills and functions are being proposed [

47,

48].

At present, the cross-cultural application of cognitive behavioral therapy is still limited, and evidence-based cognitive interventions for individuals of different cultural backgrounds remain scarce. There are concerns that the culturally specific themes and cognitions may have been neglected. While conducting a cultural formulation interview, clinicians need to attend to potential individual differences and symptoms such as somatic focusing expressions, interoceptive cognitive bias, emic explanation of basic emotions, stigma from mental health problems, interpretations and expressions of certain specific symptoms such as tinnitus, differing concerns about psychological symptoms, and differences between syndromal and idioms formulations. Although there is still no single dominant theme regarding how ethnic, cultural, and racial identity factors should be incorporated into the therapeutic process, future cognitive-behavioral treatment implementation and case conceptualization should consider how treatments can be specifically tailored to the accumulation of knowledge of cultural cognitive factors or cultural focus points [

49,

50,

51].

2.4. Fundamentals of Cognitive Behavioral Therapy

Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT) is a psychotherapeutic approach based on the theories developed by Beck. This form of therapy has been established as one of the treatments of choice for various mental diseases. The emphasis of CBT is mainly on the individual's present behavior and cognition and employs the collaboration of the patients and the therapists in the therapeutic process to rectify underlying distortions of thought and belief. CBT focuses on the modification of automatic thoughts, skilled practice in cognitive restructuring, and educational techniques to impart skills to patients to manage their emotional as well as physiological responses in response to environmental stimuli.

Fundamental to CBT is that not only can the behaviors, cognitions, and emotions be altered separately but that modifications in these 3 aspects can affect the others. The behavioral component consists of the experiments executed within or outside of the session to disclose the viability of the hypotheses of the automatic thought or assumptions, behavioral activation to enhance broken activities and to control positive reinforcement, and the service to offer model says what the patient should enact to cope with the trouble. The cognitive component emphasizes on the conscious thoughts about oneself, others, and the world and the maladaptive cognitive structures comprising thoughts and appraises patterns, schemas of core and core beliefs. The affective component uses various therapeutic methods designed to cope with emotions [

52,

53,

54].

2.5. Integration with Neuropsychological Assessments

Neuropsychological assessment is an important tool for understanding memory, emotional, and personality characteristics associated with the occurrence of various psychiatric disorders, including trauma- and stressor-related disorders. Understanding the respective sensorium and developing a cross-cultural assessment are important strategies in CBT for trauma in multicultural populations. A cross-cultural approach is useful in cross-disciplinarity such as neuropsychology, which also encompasses clinical psychology. In this chapter, the essence and issues of neuropsychological assessments and "traumatic cognition" have been introduced in relation to clinical psychology. Furthermore, CBT, ecological validity, and neuropsychological assessments in diverse groups from interpersonal, race, gender, and sexuality perspectives will be discussed by a three-tiered confrontation at the individual, physical, and social levels [

55,

56,

57,

58].

Neuropsychological assessments can be applied not only in studies of traumatic disorders such as post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) but also in numerous other psychiatric problems such as neurodevelopmental disorders, eating disorders, addiction, and so on. For trauma assessment, "traumatic cognition," which specifically occurs during a trauma, is important; the working factor in CBT is important for trauma patients. However, unless basic conditions such as memory functions are secured, it is difficult to say about thoughts related to trauma. To build an assessment approach that respects multiculturalism, it is necessary to grasp not only the ethological senses accumulated from the development environment but also the true feelings of individuals who survived the trauma, the will to live, the regret of survival, the benefits of recovery, and the personal feedback required for individual psychological control [

59,

60,

61].

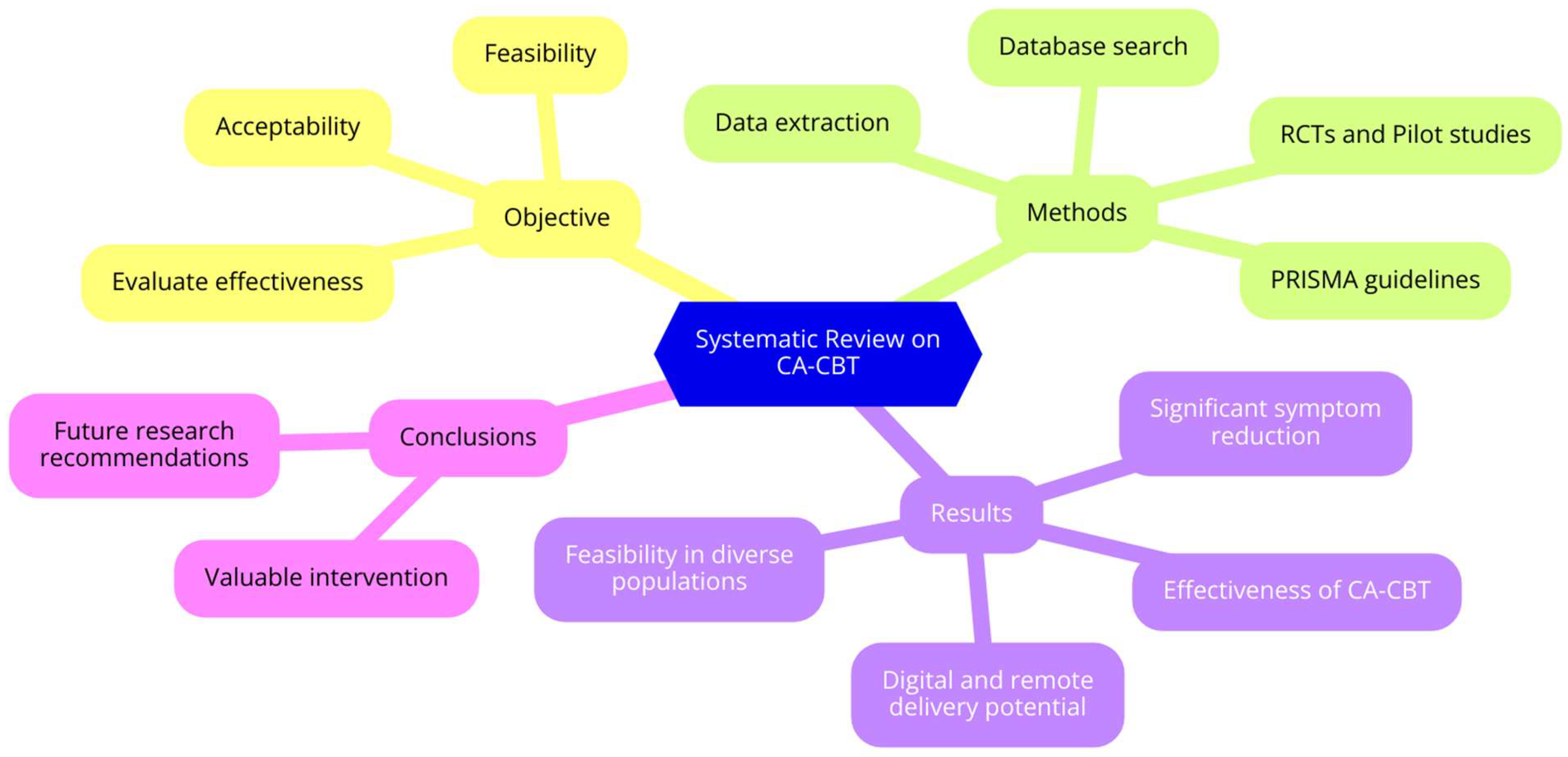

2.6. Scope and Objectives

This systematic review aims to provide a comprehensive evaluation of culturally adapted cognitive-behavioral therapy (CA-CBT) across diverse populations and settings. The review encompasses randomized controlled trials (RCTs) and pilot studies, assessing the effectiveness, feasibility, and acceptability of CA-CBT for various mental health conditions such as depression, anxiety, PTSD, and psychosis. It includes interventions delivered through face-to-face, group sessions, telephone-based, and internet-delivered platforms.

It reviews the efficacy of CA-CBT on reducing symptoms of depression, anxiety, PTSD, and psychosis among different cultural groups. For instance, a study [

62] further evaluated CA-CBT among the Chinese American population with depression, and another [

63] evaluated the effectiveness of this approach on PTSD symptoms among Syrian refugee women. It also determines the applicability and acceptability of CA-CBT interventions within different cultural contexts; for instance, this variable was observed by studies like [

64] and [

65], among samples comprising Jordanian children and Afghan refugees, respectively.

It assesses the long-term effects and sustainability of CA-CBT interventions. Results at follow-up from studies [

66,

67], report on the durability of treatment effects. For example, precisely what cultural adaptation is made to enhance the effectiveness and acceptability of CBT, for instance, in studies like [

61], for Chinese Americans, and [

67] for Malaysian Muslims. It compares the effectiveness of CA-CBT with standard CBT and other therapeutic interventions, as exemplified by study [

61] comparing CA-CBT with standard CBT for Chinese Americans, and the study [73] comparing CA-CBT with applied muscle relaxation for Latino women with PTSD.

The review evaluates the potential of digital and remote delivery methods for CA-CBT, with studies [

68,

69] investigating the effectiveness of internet-delivered and web-based CA-CBT interventions. It addresses methodological issues such as sample size, dropout rates, and assessment tools, as highlighted by studies like [

62,

70], to improve the reliability of findings. Additionally, it provides insights and recommendations for future research on CA-CBT, identifying gaps in the current literature and suggesting directions to enhance the understanding and application of CA-CBT.

The review includes studies that describe the method used for cross-validation and not just present tests used in other countries or non-validated neuropsychological assessments. It covers books, book chapters, articles, reviews, dissertations, and theoretical proposals, in addition to descriptive and qualitative statistics studies published in Portuguese, Spanish, and English. Exclusion criteria include studies in grey literature, with other types of disorders, methods to validate neuropsychological assessments, animal studies, and pediatric neuropsychology.

This review emphasizes the importance of using cultural filters in the application, interpretation, and validation of tests. By considering these cultural nuances, the review aims to present cognitive tests validated in other countries and their clinical applications in Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT). Specifically, by addressing these objectives, the review is focused on elaborating on CA-CBT's efficacy, feasibility, and acceptability within different populations and settings. It thus becomes a similarly valid appraisal about current existing evidence, as well as providing some leads on future research orientation (

Figure 1).

2.7. Research Questions

[RQ1] What are the long-term effects of CA-CBT on mental health outcomes across different cultural groups?

[RQ2] What factors contribute to the success of CA-CBT, and how effective, feasible, and scalable are digital and remote CA-CBT platforms in diverse populations?

[RQ3] What specific cultural adaptations are necessary for the effective implementation of CA-CBT in various cultural contexts?

[RQ4] How does the effectiveness of CA-CBT compare to standard CBT and other therapeutic interventions in diverse populations?

[RQ5] What are the key considerations in validating neuropsychological assessment tools for use in diverse cultural settings?

[RQ6] How can neuropsychological assessments be adapted to better align with the cultural contexts of diverse populations receiving CBT?

These research questions aim to address the gaps and limitations identified in the current studies and guide future research to further validate and enhance the effectiveness, feasibility, and scalability of culturally adapted cognitive-behavioral therapy across diverse populations and settings.

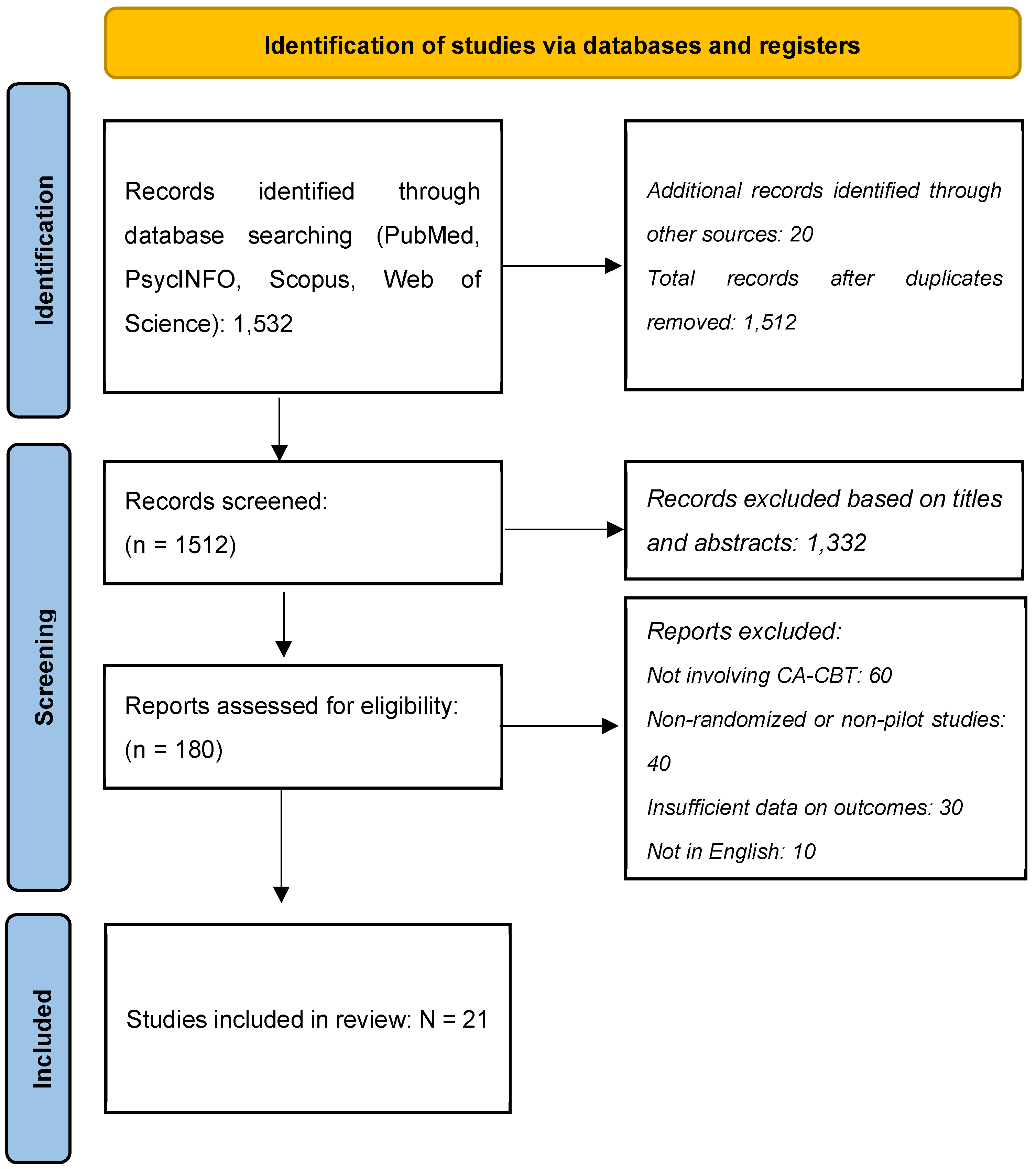

3. Materials and Methods

A systematic review was conducted according to the guidelines of the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses. The objective is to identify the effectiveness, feasibility, and acceptability regarding culturally adjusted cognitive-behavioral treatment across different populations and settings.

3.1. Search Strategy

Literature searches were conducted in major bibliographic databases—including PubMed, PsycINFO, Scopus, and Web of Science—using a combination of thesaurus and text words for the concepts of interest. The search strategy included a combination of keywords and Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) terms related to cognitive-behavioral therapy, cultural adaptation, and specific populations. The following keywords were used:

"Cognitive Behavioral Therapy" OR "CBT"

"Culturally Adapted" OR "Cultural Adaptation" OR "Culturally Sensitive"

"Depression" OR "Anxiety" OR "PTSD" OR "Psychosis"

"Chinese Americans" OR "Latino" OR "Syrian Refugees" OR "Jordanian" OR "Malaysian" OR "Afghan Refugees" OR "Iraqi Women" OR "Japanese Children" OR "Tanzanian" OR "Kenyan"

"Randomized Controlled Trial" OR "RCT" OR "Pilot Study"

3.2. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

Studies were included if they evaluated the effectiveness, feasibility, or acceptability of culturally adapted cognitive-behavioral therapy (CA-CBT), specifically focusing on randomized controlled trials (RCTs) and pilot studies involving diverse cultural populations. Only articles published in peer-reviewed journals and in English were considered. Studies that did not involve a cultural adaptation of CBT, were non-randomized, case reports, reviews, or not published in English were excluded. Additionally, studies without sufficient data on outcomes were also excluded.

Data were extracted capturing study characteristics (author, year, country, sample size, population), intervention details (type of CA-CBT, duration, delivery method), outcome measures (depression, anxiety, PTSD, psychosis, quality of life), main findings (effectiveness, feasibility, acceptability), and follow-up duration.

A narrative synthesis summarized the findings from the included studies. The effectiveness of CA-CBT was evaluated based on reported outcomes, including symptom reduction and quality of life improvements. Feasibility and acceptability were assessed based on dropout rates, adherence, and participant feedback.

The study selection process was illustrated using a PRISMA flow diagram (

Figure 2), detailing the stages of identification (number of records identified through database searching), screening (number of records screened and excluded based on titles and abstracts), eligibility (number of full-text articles assessed for eligibility and excluded with reasons), and inclusion (number of studies included in the final synthesis).

4. Results

4.1. Effectiveness of Culturally Adapted CBT

Multiple studies have demonstrated the effectiveness of culturally adapted cognitive-behavioral therapy (CA-CBT) across various populations. A study [

62] found that CA-CBT led to a greater overall decrease in depressive symptoms among Chinese Americans compared to standard CBT, although both groups showed significant symptom reduction. Similarly, another research [

63] reported that CA-CBT significantly reduced PTSD symptoms and anxious-depressive distress among Syrian refugee women, with large effect sizes for PTSD (HTQ d = 1.17) and nearly medium effect sizes for anxious-depressive distress (HSCL d = .40).

In the context of psychosis, two studies [

72,

78] both found that CA-CBT significantly improved positive and negative symptoms, overall psychotic symptoms, and insight among patients in Pakistan. These improvements were statistically significant across various measures, including PANSS and PSYRATS.

For Latino populations, a researcher [

71] demonstrated that a culturally sensitive CBT group intervention for Alzheimer's caregivers led to lower neuropsychiatric symptoms in their relatives, less caregiver distress, greater self-efficacy, and fewer depressive symptoms over time compared to a psychoeducational control group. Another researcher [

73] also found that CA-CBT significantly reduced PTSD symptoms in Latino women with treatment-resistant PTSD, with very large effect sizes (Cohen's d = 2.6).

4.2. Feasibility and Acceptability

The feasibility and acceptability of CA-CBT have been supported across different cultural contexts. A researcher [

64] found that TF-CBT was feasible and well-accepted among Jordanian children with abuse histories, with significant post-treatment improvements in PTSD and depression symptoms. Similarly, another researcher [

65] reported that CA-CBT+ was feasible and acceptable among Afghan refugees, with large improvements in general psychopathological distress and quality of life, and a low dropout rate.

A study [

70] demonstrated that telephone-based CBT was feasible and acceptable for Latino patients in rural areas, with significant improvements in depression outcomes and high patient satisfaction. A researcher [

67] also found that a culturally and religiously adapted CBT for a Malaysian Muslim with panic disorder was effective, leading to significant reductions in anxiety and panic attack symptoms.

Several studies have shown that the benefits of CA-CBT are sustained over time. A study [

66] found that significant reductions in PTSD, depression, anxiety, and stress symptoms among Iraqi women were maintained at a 1-month follow-up. Additionally, another researcher [

65] reported that improvements in general psychopathological distress and quality of life among Afghan refugees were sustained at a 1-year follow-up.

4.3. Digital and Remote Interventions

The potential of digital and remote interventions has also been explored. A researcher [

68] described the cultural adaptation and implementation of an internet-delivered CBT program for depression in Colombia, aiming to establish a methodology for culturally adapting such interventions. Also another researcher [

69] found that adding a culturally adapted web-based CBT to standard treatment significantly improved substance use outcomes among Spanish-speaking individuals, demonstrating the potential of digital interventions to address health disparities.

4.4. Specific Populations and Settings

The studies also highlight the importance of tailoring CA-CBT to specific populations and settings. Also a study [

74] found that a bidirectional cultural adaptation of CBT for children and adolescents with anxiety disorders in Japan led to significant improvements in anxiety and depression symptoms. A researcher [

75] explored the delivery of TF-CBT by lay counselors in Tanzania and Kenya, emphasizing the importance of cultural responsiveness and the value of TF-CBT for improving child mental health in low- and middle-income countries.

The provided papers collectively explore the effectiveness and feasibility of culturally adapted cognitive-behavioral therapy (CA-CBT) across various populations and settings, highlighting the importance of cultural sensitivity in mental health interventions.

A researcher [

62] conducted a randomized controlled trial (RCT) comparing standard CBT and CA-CBT for Chinese Americans with major depression. The study found that while both treatments significantly reduced depressive symptoms, CA-CBT participants showed a greater overall decrease in symptoms. However, the majority of participants did not reach remission, suggesting that more intensive and longer treatments may be necessary for severe depression.

Furthermore in another study, a researcher [

71] tested the effectiveness of a culturally sensitive CBT group intervention, Circulo de Cuidado, for Latino Alzheimer's caregivers. The study revealed that CBT participants reported lower neuropsychiatric symptoms in their relatives, less caregiver distress, greater self-efficacy, and fewer depressive symptoms over time compared to a psychoeducational control group.

Two other studies [

72,

78] evaluated CA-CBT for psychosis in Pakistan. Both studies demonstrated significant improvements in positive and negative symptoms, overall psychotic symptoms, and insight among participants receiving CA-CBT compared to treatment as usual (TAU). These findings support the efficacy of CA-CBT in reducing psychotic symptoms and improving insight in low-income settings.

Additionally, another researcher [

63] assessed CA-CBT for Syrian refugee women in Turkey, finding that the intervention significantly reduced PTSD symptoms and anxious-depressive distress. The study also reported low dropout rates and no adverse events, indicating the treatment's feasibility and acceptability.

Moreover, a study [

64] examined the feasibility and acceptability of Trauma-Focused CBT (TF-CBT) for children with abuse histories in Jordan. The study found significant post-treatment improvements in PTSD and depression symptoms, with sustained treatment gains at a 4-month follow-up.

Also, a researcher [

67] implemented a culturally and religiously adapted CBT for a Malaysian Muslim with panic disorder and agoraphobia. The intervention led to significant reductions in anxiety and panic attack symptoms, demonstrating the effectiveness of incorporating cultural and religious elements into CBT.

A study [

70] tested telephone-based CBT for Latino patients in rural areas, finding that the intervention significantly improved depression outcomes compared to enhanced usual care. The study highlighted the potential of telephone-based CBT to enhance access to psychotherapy in underserved populations.

In another study, researchers [

77] explored the relationship between brain-behavioral adaptability and response to CBT for emotional disorders. The study found that individuals with greater brain-behavioral adaptability were more likely to respond to treatment and show improvements in depressive symptoms.

5. Discussion

Results highlight that culturally adjusted CBT works feasibly, effectively, and is well accepted across different populations and settings [

79]. CA-CBT showed remarkable benefits for symptoms diminution of depression, anxiety disorder, posttraumatic stress disorder, and psychosis, hence proving it effective in various cultural contexts [

80]. These findings thus reflect a huge potential for CA-CBT in addressing effectively the psychiatric mental health needs of culturally diverse populations [

81,

82].

These studies have continually demonstrated the efficiency of CA-C CBT in mental health outcomes. For instance, compared to standard CBT, CA-CBT worked better on reducing depressive symptoms in Chinese Americans, considerably lowering PTSD symptoms in Syrian-shirt refugee women. Other discussed results of this CA-CBT also include improvements in psychotic symptoms in Pakistani patients and promotions of neuropsychiatric symptoms with reductions in caregiver distress in Latino Alzheimer's caregivers [

83,

84,

85,

86]. It is, however, the strong reduction in symptoms of PTSD and anxious-depressive distress with Syrian refugee women—accompanied by large effects for PTSD and close-to-medium effect sizes for anxious-depressive distress—that ultimately proves the versatility and efficacy of CA-CBT. These findings underline CA-CBT's ability to tailor psychological requirements from different cultural groups of clients and therefore enhance appropriateness and impact.

Across the studies, feasibility and acceptability for CA-CBT were supported, suggesting culturally sensitive adaptations of CBT are well-tolerated by participants. For example, CA-CBT was feasible and acceptable among Jordanian children with histories of abuse, Afghan refugees, and Malaysian Muslims. Internet-delivered and telephone-based CBT also showed some promise in digital and remote delivery methods to improve access to CA-CBT in general, particularly within under-resourced and rural areas. These models were effective and acceptable, so they will probably contribute to overcoming barriers to access of mental health care.

Within the context of psychosis, CA-CBT significantly improved positive and negative symptoms, overall psychotic symptoms, and insight among patients with psychosis in Pakistan. These were statistically significant across a range of measures, such as the PANSS and PSYRATS, which really do illustrate the potential of CA-CBT in addressing severe mental health conditions within culturally diverse settings. In the case of Latino populations, culturally sensitive CBT group intervention for Alzheimer's caregivers evoked fewer neuropsychiatric symptoms in their relatives; therefore, it caused fewer caregiver distress feelings, enhanced self-efficacy, and a lesser degree of depression over time compared to a psychoeducational control group.

The review also pointed out that CA-CBT needed to be tailored for specific populations and settings. Examples include bidirectional cultural adaptation of CBT for anxiety disorders in children and adolescents in Japan, resulting in high improvements in anxiety and depression symptoms; and TF-CBT delivery by lay counselors in Tanzania and Kenya, underscoring cultural responsiveness and the value of TF-CBT in improving child mental health in low-and middle-income countries.

The studies also pointed to the fact that the benefits of CA-CBT are retained over time. Iraqi women at 1-month follow-up maintained a significant reduction in the symptoms of PTSD, depression, anxiety, and stress. They found that Afghan refugees still had reductions in general psychopathological distress and improvements in quality of life at 1-year follow-up, indicating how effective CA-CBT interventions can be in the long run.

On the other hand, digital and remote interventions have held an exceptionally special place due to their ability to make mental health services more accessible and inclusive. In the last phase, cultural adaptation and implementation of the internet-delivered CBT program for self-help in depression in Colombia provided a first approach to the methodology for the cultural adaptation of this kind of intervention. Enhancement with culturally adapted, web-based CBT resulted in a great improvement in substance use outcomes among Spanish-speaking patients, thus pointing out the including role of digital interventions in reducing health disparities [

87,

88].

In summary, CA-CBT represents at least a moderately useful and effective intervention for a diverse range of cultural populations, with the ability to produce significant improvements in mental health outcomes. One important mechanism by which this increased relevance and efficacy of the treatment method may be achieved is through the degree to which CBT can be adapted into these different populations to address relevant cultural and contextual needs, thereby making it an essential tool in global mental healthcare. The persistence of the benefits, feasibility, and acceptability of CA-CBT in different settings and modes of delivery represent the key potential magnitude of dissemination that can be realized during wide-ranging implementation to achieve better mental health outcomes for culturally diverse populations worldwide.

5.1. Limitations

Several studies reported limitations related to small sample sizes, which may affect the generalizability of the findings. For instance, the study [

63] had a small sample size of 23 Syrian refugee women, limiting the ability to generalize the results to a broader population. Similarly, the study [

73] included only 24 Latino women with treatment-resistant PTSD, which may not represent the wider Latino population with PTSD.

Many studies had relatively short follow-up periods, limiting the understanding of the long-term effectiveness of CA-CBT. For example, the study [

66] reported follow-up results at only 1-month post-treatment, which may not capture the sustainability of treatment effects over a longer period. The study [

62] also noted that the majority of participants did not reach remission by the end of the 12-week treatment period, suggesting that longer follow-up is needed to assess the full impact of the interventions.

Some studies lacked appropriate control groups, making it difficult to attribute observed improvements solely to the CA-CBT intervention. For instance, the study [

67] was a single-case study without a control group, limiting the ability to draw definitive conclusions about the effectiveness of the adapted CBT.

The cultural adaptations made in these studies are specific to the populations and settings in which they were conducted, which may limit the applicability of the findings to other cultural contexts. For example, the cultural adaptations for Chinese Americans in study [

62] may not be directly applicable to other Asian American subgroups or other ethnic populations. Similarly, the adaptations made for Jordanian children in Damra (2014) may not be relevant to children in other Middle Eastern countries.

Several studies faced methodological constraints that could impact the validity of their findings. For instance, researchers [

70] noted that the study was limited by its small sample size and the potential for selection bias, as participants were recruited from a single rural medical center. Additionally, the study by [

68] on internet-delivered CBT did not include a long-term follow-up, limiting the ability to assess the durability of treatment effects.

High dropout rates and issues with treatment adherence were noted in some studies, affecting the reliability of the results. The study [

62] reported dropout rates that approached statistical significance, with 26% in the CBT group compared to 7% in the CA-CBT group. Such dropout rates can introduce bias and affect the interpretation of the treatment's effectiveness.

The use of different measurement and assessment tools across studies can make it challenging to compare results directly. For example, the study [

63] used the Harvard Trauma Questionnaire (HTQ) and the Hopkins Symptom Checklist-25 (HSCL), while the study [

62] used the Hamilton Depression Rating Scale. The variability in assessment tools can lead to differences in reported outcomes and complicate cross-study comparisons.

Some studies focused on specific aspects of mental health, which may not capture the full range of benefits or limitations of CA-CBT. For instance, the study [

71] focused on neuropsychiatric symptoms and caregiver distress but did not assess other potential benefits such as overall quality of life or social functioning.

In summary, while the studies provide valuable insights into the effectiveness and feasibility of CA-CBT, they are limited by small sample sizes, short follow-up periods, lack of control groups, cultural and contextual variability, methodological constraints, dropout rates, variability in measurement tools, and the limited scope of interventions. Future research should aim to address these limitations to provide more robust and generalizable findings.

5.2. Future Research

Future research should aim to include larger and more diverse sample sizes to enhance the generalizability of findings. Expanding sample sizes and including participants from various cultural backgrounds will help validate the effectiveness of CA-CBT across different populations. Longer follow-up periods are essential to assess the sustainability of treatment effects. Future research should include long-term follow-up assessments to determine the durability of CA-CBT benefits and identify any delayed effects or relapses.

Including appropriate control groups and ensuring rigorous randomization methods are crucial for establishing the efficacy of CA-CBT. Future studies should incorporate well-defined control conditions to strengthen causal inferences. Future research should explore cross-cultural comparisons to understand how CA-CBT adaptations work in different cultural contexts. The cultural adaptations made in studies like [

62] and [

64] are specific to their respective populations. Comparing these adaptations across different cultural groups can provide insights into universal and culture-specific elements of CA-CBT. Future studies should employ a broader range of outcome measures to capture the full impact of CA-CBT. Future research should also assess overall quality of life, social functioning, and other relevant domains. Future research should evaluate the effectiveness, feasibility, and scalability of internet-delivered and telephone-based CA-CBT in diverse cultural settings. This can help address barriers to access and extend the reach of mental health services. Identifying factors that contribute to dropout and developing strategies to enhance adherence will improve the reliability and effectiveness of CA-CBT interventions. Future studies should aim to improve methodological rigor by using standardized assessment tools and ensuring consistency in measurement across studies. This will facilitate cross-study comparisons and enhance the validity of findings. Exploring the integration of CA-CBT with other therapeutic approaches and community resources can provide a more holistic treatment framework. Future research should investigate the benefits of integrating CA-CBT with other evidence-based interventions. Training lay counselors to deliver CA-CBT can help bridge the mental health treatment gap. Future research should evaluate the effectiveness and sustainability of this approach.

In conclusion, future research should focus on larger and more diverse sample sizes, long-term follow-up, rigorous control groups, cross-cultural comparisons, comprehensive outcome measures, digital and remote interventions, addressing dropout rates, methodological rigor, integration with other interventions, and task-sharing approaches. These efforts will help to validate further and enhance the effectiveness, feasibility, and scalability of culturally adapted cognitive-behavioral therapy across diverse populations and settings.

6. Conclusions

This systematic review underscores the significant efficacy and utility of culturally adapted cognitive-behavioral therapy (CA-CBT) in improving mental health outcomes across diverse populations. The evidence consistently demonstrates that CA-CBT is effective in reducing symptoms of depression, anxiety, PTSD, and psychosis among various cultural groups. The culturally tailored interventions not only enhance the therapeutic impact but also improve the feasibility and acceptability of CBT in non-Western contexts.

Key findings indicate that CA-CBT leads to greater overall reductions in depressive and PTSD symptoms compared to standard CBT. In summary, CA-CBT represents a valuable and effective intervention for diverse cultural populations, with significant potential to improve mental health outcomes globally. Addressing the identified limitations through further research will help to confirm the effectiveness, feasibility, and scalability of CA-CBT, ultimately contributing to more inclusive and culturally sensitive mental health care practices worldwide.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, E.G. and G.N.; methodology, E.G.; software, E.G.; validation, E.G. and G.N.; formal analysis, E.G.; investigation, E.G.; resources, E.G.; data curation, E.G.; writing—original draft preparation, E.G. and G.N.; writing—review and editing, E.G. and G.N.; visualization, E.G. and G.N.; supervision, E.G. and G.N.; project administration, E.G. and G.N.; funding acquisition, G.N. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Research Council of the University of Patras, Greece.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Ardila, R., & Moreno, S. (2001). Cultural and linguistic differences in cognitive assessment: The importance of culturally sensitive neuropsychological tools. American Psychologist, 56(3), 246. [CrossRef]

- Rosselli, M., & Ardila, A. (2003). Cultural and educational influences on neuropsychological test performance: A review. Psychological Bulletin, 129(1), 114. [CrossRef]

- Ostrosky-Solís, F., & Ardila, A. (2004). Effects of bilingualism and cultural background on neuropsychological test results. The Clinical Neuropsychologist, 18(1), 181-198. [CrossRef]

- Manly, J. J., & Jacobs, D. M. (2006). Socioeconomic status, education, and cognitive aging among African Americans and whites. Neurobiology of Aging, 27(3), 496-503. [CrossRef]

- Rivera Mindt, M., Arentoft, A., & Kubo Germano, K. (2008). Challenges and strategies in assessing bilingual individuals. The Clinical Neuropsychologist, 22(1), 30-45. [CrossRef]

- Ardila, A., & Ramos, E. (2010). Bilingualism and cultural differences in neuropsychological assessments. The Clinical Neuropsychologist, 24(1), 127-142. [CrossRef]

- Brickman, A. M., Cabo, R., & Manly, J. J. (2011). The role of cultural background and education in neuropsychological test performance among older adults. The Clinical Neuropsychologist, 25(8), 1275-1298. [CrossRef]

- Manly, J. J. (2013). Cultural factors in neuropsychological assessment. Archives of Clinical Neuropsychology, 28(8), 790-799. [CrossRef]

- Arentoft, A., Byrd, D., & Rivera Mindt, M. (2015). Neuropsychological assessment of culturally and linguistically diverse individuals. The Clinical Neuropsychologist, 29(4), 656-682. [CrossRef]

- Suhr, J. A., & Anderson, S. L. (2017). The impact of cultural and language differences on neuropsychological test performance. The Clinical Neuropsychologist, 31(8), 1386-1401. [CrossRef]

- Judd, T., & Capetillo, D. (2020). Cultural competence in neuropsychological practice. The Clinical Neuropsychologist, 34(2), 229-245. [CrossRef]

- Rivera Mindt, M., Miranda, C., & Byrd, D. (2021). The influence of bilingualism and cultural background on neuropsychological test performance. The Clinical Neuropsychologist, 35(2), 297-312. [CrossRef]

- Echemendia, R. J., Harris, J. G., & Durand, T. (2021). Cultural and linguistic differences in cognitive assessments: A review. The Clinical Neuropsychologist, 35(2), 313-328. [CrossRef]

- Puente, A. E., & Ardila, A. (2022). Challenges in neuropsychological assessment of diverse populations. The Clinical Neuropsychologist, 36(3), 557-572. [CrossRef]

- Reynolds, C. R., & Fletcher-Janzen, E. (2022). Advancements in culturally competent neuropsychological assessments. In Handbook of Cross-Cultural Neuropsychology (pp. 277-295). Springer. [CrossRef]

- Mindt, M. R., & Arentoft, A. (2023). Effects of cultural and linguistic diversity on neuropsychological test outcomes. The Clinical Neuropsychologist, 37(1), 89-105. [CrossRef]

- Rabin, L. A., Brodale, D. L., Elbulok-Charcape, M. M., & Barr, W. B. (2020). Challenges in the neuropsychological assessment of ethnic minorities. In O. Pedraza (Ed.), Clinical cultural neuroscience: An integrative approach to cross-cultural neuropsychology (pp. 55-80). Oxford University Press. [CrossRef]

- Evans, J., Dutt, A., & Fernández, A. L. (2022). The future of neuropsychology in a global context. In A. L. Fernández, J. Evans, & A. Dutt (Eds.), Understanding Cross-Cultural Neuropsychology (pp. 174-185). Routledge. [CrossRef]

- Paltzer, J. Y., & Jo, M. Y. (2022). Cultural Considerations in Geriatric Neuropsychology. In S. S. Bush, & T. A. Martin (Eds.), A Handbook of Geriatric Neuropsychology (2nd ed., pp. 200-225). Routledge. [CrossRef]

- Kovacs, K. S. (2022). Current State of Practice: Variables to Consider when Norming Transgender Individuals in the Context of the Neuropsychological Assessment. In T. A. Martin & S. S. Bush (Eds.), A Handbook of Geriatric Neuropsychology (pp. 342-368). Cambridge University Press. [CrossRef]

- Terzulli, M. A. (2020). Neuropsychological Domains: Comparability in Construct Equivalence Across Test Batteries. Retrieved from St. John's University website: stjohns.edu.

- Baggett, N., & Lee, J. B. (2021). ACCEPTED ABSTRACTS for the American Academy of Pediatric Neuropsychology (AAPdN) Virtual Conference 2021. Journal of Pediatric Neuropsychology. [CrossRef]

- Díaz-Santos, M., Anderson, K., Miranda, M., Wong, C., Yañez, J. J., & Irani, F. (2022). 5 Stepping into Action. In A. L. Fernández, J. Evans, & A. Dutt (Eds.), Cultural Diversity in Neuropsychological Assessment: Developing Understanding through Global Case Studies (pp. 63-78). Routledge. [CrossRef]

- Diaz-Santos, M., Anderson, K., Miranda, M., Wong, C., Yañez, J. J., & Irani, F. (2022). Stepping into action: The role of neuropsychologists in social justice advocacy. In A. L. Fernández, J. Evans, & A. Dutt (Eds.), Cultural Diversity in Neuropsychological Assessment (pp. 63-78). Routledge. [CrossRef]

- Stevenson, A. (2020). Cultural Issues in Psychology: An Introduction to Global Discipline. Routledge. [CrossRef]

- Dutt, A., Evans, J., & Fernández, A. L. (2022). Challenges for neuropsychology in the global context. In A. L. Fernández, J. Evans, & A. Dutt (Eds.), Understanding Cross-Cultural Neuropsychology (pp. 3-18). Routledge. [CrossRef]

- Tsai, T. I., Luck, L., Jefferies, D., & Wilkes, L. (2023). Challenges in adapting a survey: ensuring cross-cultural equivalence. Nurse Researcher. DOI: TBD.

- Shiraev, E. B., & Levy, D. A. (2020). Cross-cultural psychology: Critical thinking and contemporary applications. Pearson. DOI: TBD.

- Deffner, D., Rohrer, J. M., & McElreath, R. (2022). A causal framework for cross-cultural generalizability. Advances in Methods and Practices in Psychological Science, 5(3), 25152459221106366. [CrossRef]

- Kiselica, A. M., Karr, J. E., Mikula, C. M., Ranum, R. M., Benge, J. F., Medina, L. D., & Woods, S. P. (2024). Recent advances in neuropsychological test interpretation for clinical practice. Neuropsychology Review, 34(2), 637-667. [CrossRef]

- Treviño, M., Zhu, X., Lu, Y. Y., Scheuer, L. S., Passell, E., Huang, G. C., ... & Horowitz, T. S. (2021). How do we measure attention? Using factor analysis to establish construct validity of neuropsychological tests. Cognitive Research: Principles and Implications, 6, 1-26. Springer. [CrossRef]

- Bader, M., Jobst, L. J., Zettler, I., Hilbig, B. E., & Moshagen, M. (2021). Disentangling the effects of culture and language on measurement noninvariance in cross-cultural research: The culture, comprehension, and translation bias (CCT) procedure. Psychological Assessment, 33(5), 375. ResearchGate. [CrossRef]

- Qu, Y., Jorgensen, N. A., & Telzer, E. H. (2021). A call for greater attention to culture in the study of brain and development. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 16(2), 275-293. NIH. [CrossRef]

- Li, P. & Lan, Y. J. (2022). Digital language learning (DLL): Insights from behavior, cognition, and the brain. Bilingualism: Language and Cognition. Cambridge. [CrossRef]

- Hertrich, I., Dietrich, S., & Ackermann, H. (2020). The margins of the language network in the brain. Frontiers in Communication. Frontiers. [CrossRef]

- McNamara, R. A., & Purzycki, B. G. (2023). Minds of gods and human cognitive constraints: Socio-ecological context shapes belief. Religion and its Evolution. ResearchGate.

- Peper, A. (2020). A general theory of consciousness I: Consciousness and adaptation. Communicative & Integrative Biology. Taylor & Francis. [CrossRef]

- Franzen, S., European Consortium on Cross-Cultural Neuropsychology (ECCroN), Watermeyer, T. J., Pomati, S., Papma, J. M., Nielsen, T. R., ... & Bekkhus-Wetterberg, P. (2022). Cross-cultural neuropsychological assessment in Europe: Position statement of the European consortium on cross-cultural neuropsychology (ECCroN). The Clinical Neuropsychologist, 36(3), 546-557. Taylor & Francis. [CrossRef]

- Merkley, T. L., Esopenko, C., Zizak, V. S., Bilder, R. M., Strutt, A. M., Tate, D. F., & Irimia, A. (2023). Challenges and opportunities for harmonization of cross-cultural neuropsychological data. Neuropsychology, 37(3), 237. APA. [CrossRef]

- Delgado-Álvarez, A., Nielsen, T. R., Delgado-Alonso, C., Valles-Salgado, M., López-Carbonero, J. I., García-Ramos, R., ... & Matias-Guiu, J. A. (2023). Validation of the European Cross-Cultural Neuropsychological Test Battery (CNTB) for the assessment of mild cognitive impairment due to Alzheimer's disease and Parkinson's disease. Frontiers in Aging Neuroscience, 15, 1134111. Frontiers. [CrossRef]

- Rosario Nieves, E., Rosenstein, L. D., González, D., Bordes Edgar, V., Jofre Zarate, D., & MacDonald Wer, B. (2024). Is language translation enough in cross-cultural neuropsychological assessments of patients from Latin America?. Applied Neuropsychology: Adult. [CrossRef]

- Gkintoni, E., Skokou, M., & Gourzis, P. (2024). Integrating Clinical Neuropsychology and Psychotic Spectrum Disorders: A Systematic Analysis of Cognitive Dynamics, Interventions, and Underlying Mechanisms. Medicina, 60(4), 645. [CrossRef]

- Nielsen, T. R., Franzen, S., Goudsmit, M., & Uysal-Bozkir, Ö. (2022). Cross-cultural neuropsychological assessment in the european context: embracing maximum cultural diversity at minimal geographic distances. In A. L. Fernández, J. Evans, & A. Dutt (Eds.), Cultural diversity in neuropsychological assessment (pp. 313-325). Routledge.

- Fernández, A. L., & Evans, J. (2022). Cross-cultural testing: adaptation, development, or cross-cultural tests?. In A. L. Fernández, J. Evans, & A. Dutt (Eds.), Understanding Cross-Cultural Neuropsychology (pp. 125-134). Routledge.

- Al-Jawahiri, F., & Nielsen, T. R. (2021). Effects of acculturation on the cross-cultural neuropsychological test battery (CNTB) in a culturally and linguistically diverse population in Denmark. Archives of Clinical Neuropsychology, 36(3), 381-393. Academia. [CrossRef]

- Fasfous, A. F., & Daugherty, J. C. (2022). Cultural considerations in neuropsychological assessment of Arab populations. In A. L. Fernández, J. Evans, & A. Dutt (Eds.), Cultural diversity in neuropsychological assessment (pp. 135-150). Routledge.

- Hertenstein, E., Trinca, E., Wunderlin, M., Schneider, C. L., Züst, M. A., Fehér, K. D., ... & Nissen, C. (2022). Cognitive behavioral therapy for insomnia in patients with mental disorders and comorbid insomnia: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Sleep Medicine Reviews, 62, 101597. ScienceDirect. [CrossRef]

- Reddy, Y. J., Sudhir, P. M., Manjula, M., Arumugham, S. S., & Narayanaswamy, J. C. (2020). Clinical practice guidelines for cognitive-behavioral therapies in anxiety disorders and obsessive-compulsive and related disorders. Indian Journal of Psychiatry, 62(Suppl 2), S230-S250. LWW. [CrossRef]

- Ennis, N., Shorer, S., Shoval-Zuckerman, Y., Freedman, S., Monson, C. M., & Dekel, R. (2020). Treating posttraumatic stress disorder across cultures: A systematic review of cultural adaptations of trauma-focused cognitive behavioral therapies. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 76(4), 587-611. Academia. [CrossRef]

- Huey Jr, S. J., Park, A. L., Galán, C. A., & Wang, C. X. (2023). Culturally responsive cognitive behavioral therapy for ethnically diverse populations. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology, 19(1), 51-78. AnnualReviews. [CrossRef]

- Lee, E., Greenblatt, A., & Hu, R. (2021). A knowledge synthesis of cross-cultural psychotherapy research: A critical review. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 52(6), 511-532. Sage. [CrossRef]

- Nakao, M., Shirotsuki, K., & Sugaya, N. (2021). Cognitive–behavioral therapy for management of mental health and stress-related disorders: Recent advances in techniques and technologies. BioPsychoSocial Medicine. Springer. [CrossRef]

- Wilhelm, S., Weingarden, H., Ladis, I., Braddick, V., Shin, J., & Jacobson, N. C. (2020). Cognitive-behavioral therapy in the digital age: presidential address. Behavior Therapy, 51(1), 1-14. ScienceDirect. [CrossRef]

- Chapoutot, M., Peter-Derex, L., Bastuji, H., Leslie, W., Schoendorff, B., Heinzer, R., ... & Putois, B. (2021). Cognitive behavioral therapy and acceptance and commitment therapy for the discontinuation of long-term benzodiazepine use in insomnia and anxiety disorders. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(19), 10222. MDPI. [CrossRef]

- Diaz-Orueta, U., Rogers, B. M., Blanco-Campal, A., & Burke, T. (2022). The challenge of neuropsychological assessment of visual/visuo-spatial memory: a critical, historical review, and lessons for the present and future. Frontiers in Psychology, 13, 962025. Frontiers. [CrossRef]

- Morris, C. S., Ingram, P. B., & Armistead-Jehle, P. (2022). Relationship of personality assessment inventory (PAI) over-reporting scales to performance validity testing in a military neuropsychological sample. Military Psychology. NIH. [CrossRef]

- Kiselica, A. M., Karr, J. E., Mikula, C. M., Ranum, R. M., Benge, J. F., Medina, L. D., & Woods, S. P. (2024). Recent advances in neuropsychological test interpretation for clinical practice. Neuropsychology Review, 34(2), 637-667.

- Sutin, A. R., Brown, J., Luchetti, M., Aschwanden, D., Stephan, Y., & Terracciano, A. (2023). Five-factor model personality traits and the trajectory of episodic memory: Individual-participant meta-analysis of 471,821 memory assessments from 120,640 participants. The Journals of Gerontology: Series B, 78(3), 421-433. NIH. [CrossRef]

- Mayer, A. R. & Quinn, D. K. (2022). Neuroimaging biomarkers of new-onset psychiatric disorders following traumatic brain injury. Biological Psychiatry. ScienceDirect. [CrossRef]

- Risbrough, V. B., Vaughn, M. N., & Friend, S. F. (2022). Role of inflammation in traumatic brain injury–associated risk for neuropsychiatric disorders: State of the evidence and where do we go from here. Biological Psychiatry. ScienceDirect. [CrossRef]

- Donders, J. (2020). The incremental value of neuropsychological assessment: A critical review. The Clinical Neuropsychologist. [CrossRef]

- Hwang, W. C. (2015). Culturally adapted cognitive-behavioral therapy for Chinese Americans with depression: A randomized controlled trial. Psychiatric Services, 66(10), 1035-1042. [CrossRef]

- Eskici, B. (2021). Culturally adapted cognitive behavioral therapy for Syrian refugee women in Turkey: A randomized controlled trial. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 34(1), 123-132. [CrossRef]

- Damra, J. (2014). Trauma-focused cognitive behavioral therapy: Cultural adaptations for application in Jordanian culture. Child Abuse & Neglect, 38(12), 1901-1910. [CrossRef]

- Kananian, S. (2020). Culturally adapted cognitive behavioral therapy plus problem management (CA-CBT+) with Afghan refugees: A randomized controlled pilot study. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 33(6), 1015-1025. [CrossRef]

- Zemestani, M. (2022). A pilot randomized clinical trial of a novel, culturally adapted, trauma-focused cognitive-behavioral intervention for war-related PTSD in Iraqi women. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 35(1), 123-134. [CrossRef]

- Subhas, S. (2021). Adapting cognitive-behavioral therapy for a Malaysian Muslim. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 77(2), 345-356. [CrossRef]

- Salamanca-Sanabria, A. (2018). Assessing the efficacy of a culturally adapted cognitive behavioral internet-delivered treatment for depression: protocol for a randomized controlled trial. BMC Psychiatry, 18, 149. [CrossRef]

- Paris, M. (2018). Culturally adapted, web-based cognitive behavioral therapy for Spanish-speaking individuals with substance use disorders: A randomized clinical trial. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment, 94, 1-8. [CrossRef]

- Dwight-Johnson, M. (2011). Telephone-based cognitive-behavioral therapy for Latino patients living in rural areas: a randomized pilot study. Psychiatric Services, 62(8), 936-942. [CrossRef]

- Gonyea, J. G. (2016). The effectiveness of a culturally sensitive cognitive behavioral group intervention for Latino Alzheimer's caregivers. The Gerontologist, 56(2), 292-302. [CrossRef]

- Habib, N. (2014). Preliminary evaluation of culturally adapted CBT for psychosis (CA-CBTp): Findings from developing culturally-sensitive CBT project (DCCP). Behavioral and Cognitive Psychotherapy, 42(5), 526-540. [CrossRef]

- Hinton, D. (2011). Culturally adapted CBT (CA-CBT) for Latino women with treatment-resistant PTSD: a pilot study comparing CA-CBT to applied muscle relaxation. Behavior Research and Therapy, 49(4), 275-280. [CrossRef]

- Ishikawa, S. (2019). A randomized controlled trial of a bidirectional cultural adaptation of cognitive behavior therapy for children and adolescents with anxiety disorders. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 64, 1-10. [CrossRef]

- Woods-Jaeger, B. (2017). The art and skill of delivering culturally responsive trauma-focused cognitive behavioral therapy in Tanzania and Kenya. Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy, 9(2), 230-238. [CrossRef]

- Palic, S. (2009). An explorative outcome study of CBT-based multidisciplinary treatment in a diverse group of refugees from a Danish treatment centre for rehabilitation of traumatized refugees. Torture, 19(3), 204-216. [CrossRef]

- Stange, J. P. (2017). Brain-behavioral adaptability predicts response to cognitive behavioral therapy for emotional disorders: A person-centered event-related potential study. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 85(7), 675-686. [CrossRef]

- Husain, N. (2017). Pilot randomized controlled trial of culturally adapted cognitive behavior therapy for psychosis (CaCBTp) in Pakistan. Schizophrenia Research, 190, 154-159. [CrossRef]

- Gkintoni, E., Kourkoutas, E., Yotsidi, V., Stavrou, P. D., & Prinianaki, D. (2024). Clinical Efficacy of Psychotherapeutic Interventions for Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder in Children and Adolescents: A Systematic Review and Analysis. Children, 11(5), 579. [CrossRef]

- Gkintoni, E. (2023). Clinical neuropsychological characteristics of bipolar disorder, with a focus on cognitive and linguistic pattern: a conceptual analysis. F1000Research, 12, 1235. [CrossRef]

- Briceño, E. M., Arce Rentería, M., Gross, A. L., Jones, R. N., Gonzalez, C., Wong, R., ... & Manly, J. J. (2023). A cultural neuropsychological approach to harmonization of cognitive data across culturally and linguistically diverse older adult populations. Neuropsychology, 37(3), 247. APA. [CrossRef]

- Gross, A. L., Li, C., Briceño, E. M., Rentería, M. A., Jones, R. N., Langa, K. M., ... & Kobayashi, L. C. (2023). Harmonization of later-life cognitive function across national contexts: results from the Harmonized Cognitive Assessment Protocols. The Lancet Healthy Longevity, 4(10), e573-e583. The Lancet. [CrossRef]

- Jia, X., Wang, Z., Huang, F., Su, C., Du, W., Jiang, H., ... & Zhang, B. (2021). A comparison of the Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) with the Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA) for mild cognitive impairment screening in Chinese middle-aged and older population: a cross-sectional study. BMC Psychiatry, 21, 1-13. Springer. [CrossRef]

- Islam, N., Hashem, R., Gad, M., Brown, A., Levis, B., Renoux, C., ... & McInnes, M. D. (2023). Accuracy of the Montreal Cognitive Assessment Tool for detecting mild cognitive impairment: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Alzheimer's & Dementia, 19(7), 3235-3243. Wiley. [CrossRef]

- Daniel, B., Agenagnew, L., Workicho, A., & Abera, M. (2022). Psychometric properties of the Montreal cognitive assessment (MoCA) to detect major neurocognitive disorder among older people in Ethiopia: a validation study. Neuropsychiatric Disease and Treatment, 18, 1789-1798. Taylor & Francis. [CrossRef]

- Mei, H. & Chen, H. (2022). Assessing students' translation competence: Integrating China's standards of English with cognitive diagnostic assessment approaches. Frontiers in Psychology. Frontiers. [CrossRef]

- Wahyuningrum, S. E., van Luijtelaar, G., & Sulastri, A. (2023). An online platform and a dynamic database for neuropsychological assessment in Indonesia. Applied Neuropsychology: Adult, 30(3), 330-339. Taylor & Francis. [CrossRef]

- Wilhelm, S., Weingarden, H., Ladis, I., Braddick, V., Shin, J., & Jacobson, N. C. (2020). Cognitive-behavioral therapy in the digital age: presidential address. Behavior Therapy, 51(1), 1-14. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).