Submitted:

20 July 2024

Posted:

22 July 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

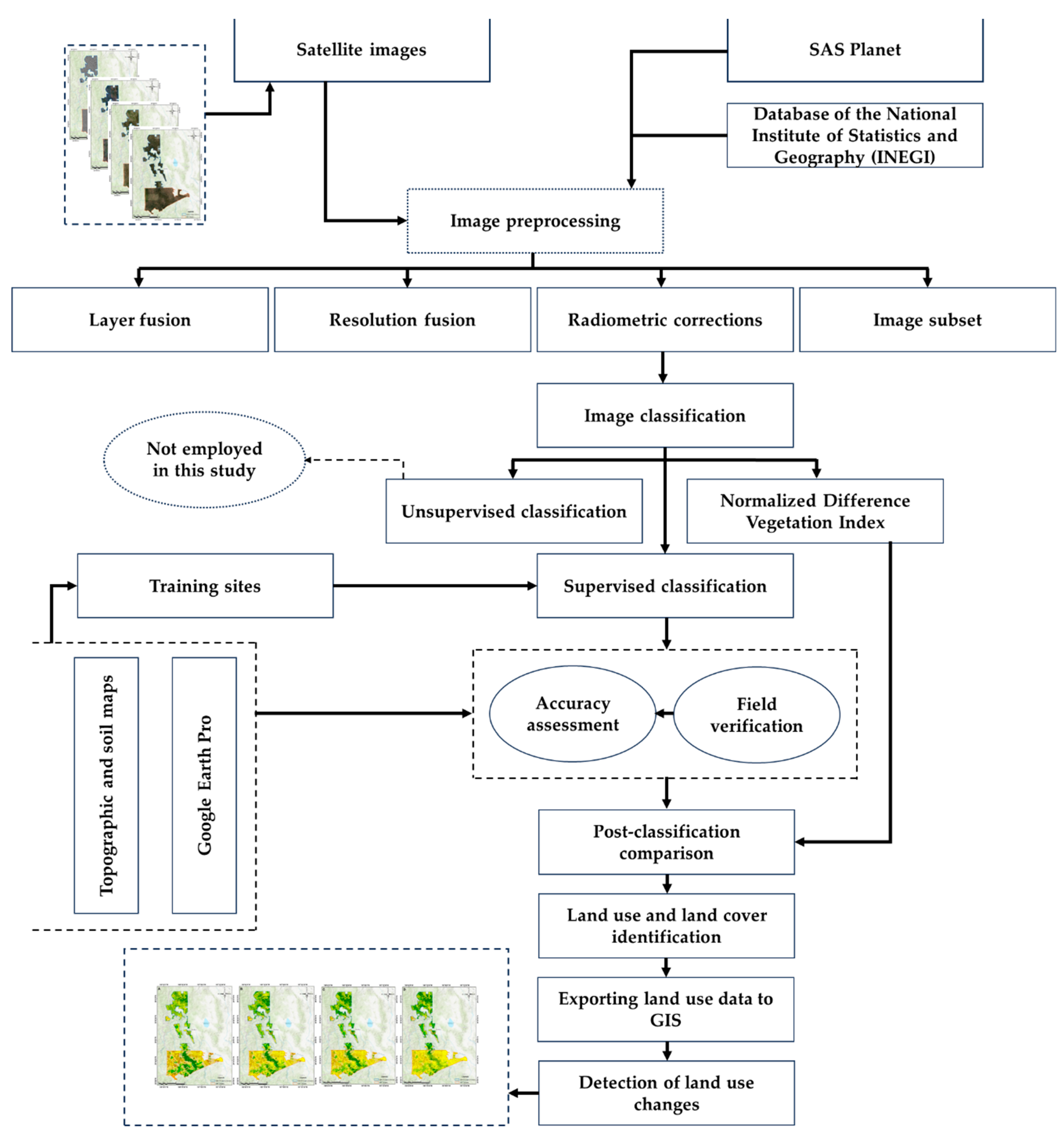

2. Materials and Methods

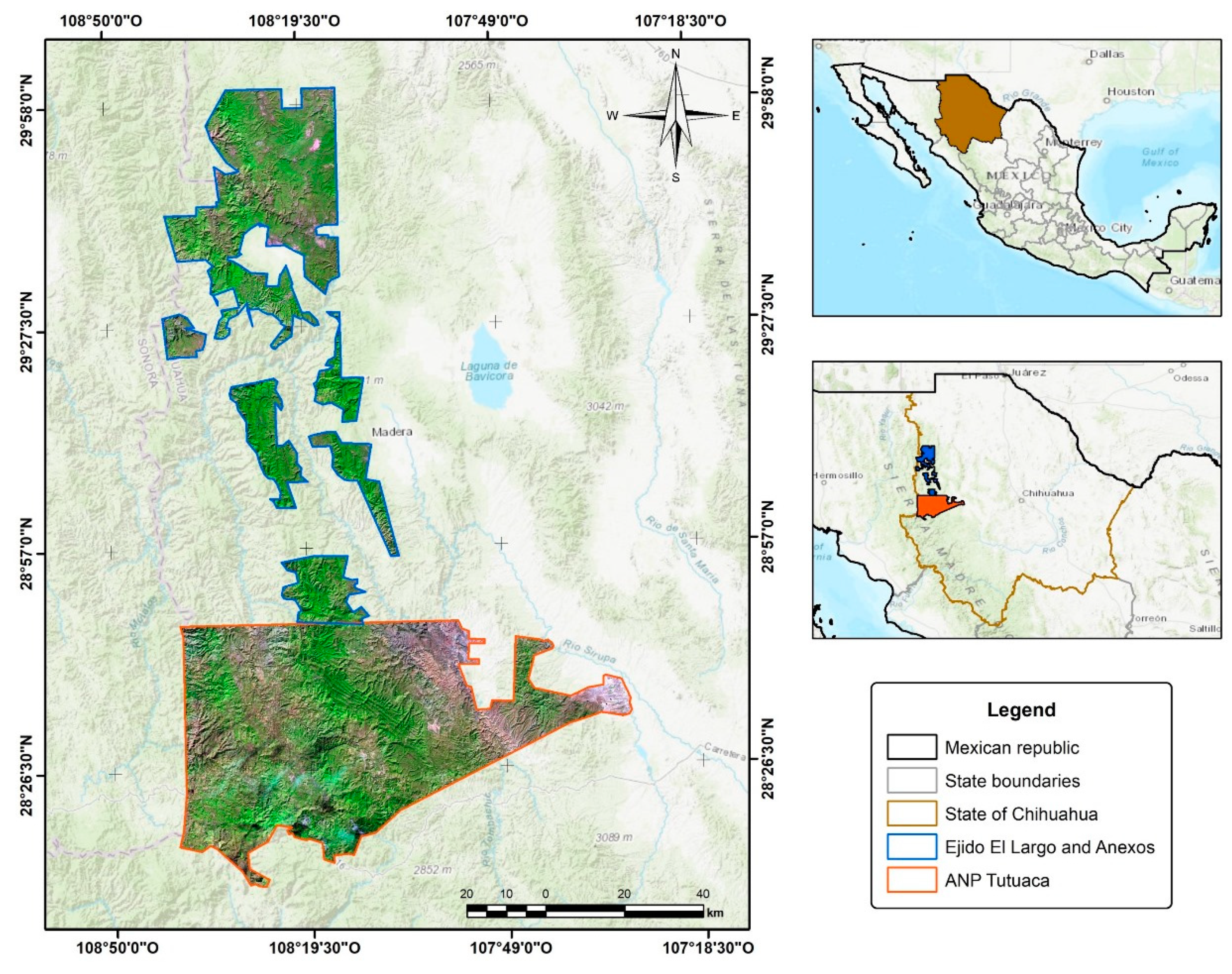

2.1. Study Area

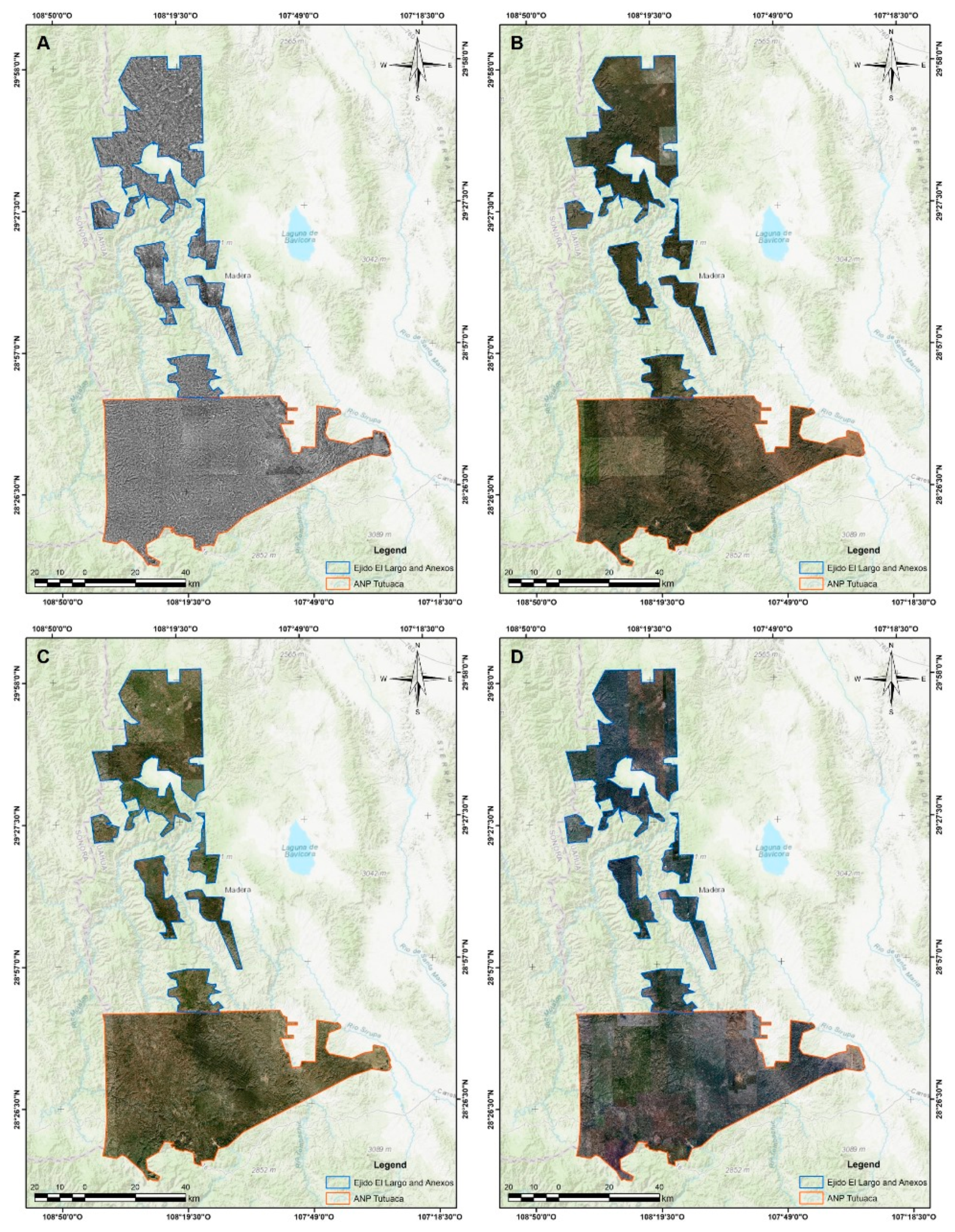

2.2. Image Acquisition

2.3. Digitization of Images

2.4. Multitemporal Analysis

2.5. Determination of Losses and Gains in Coverage

2.6. Annual Deforestation Rate

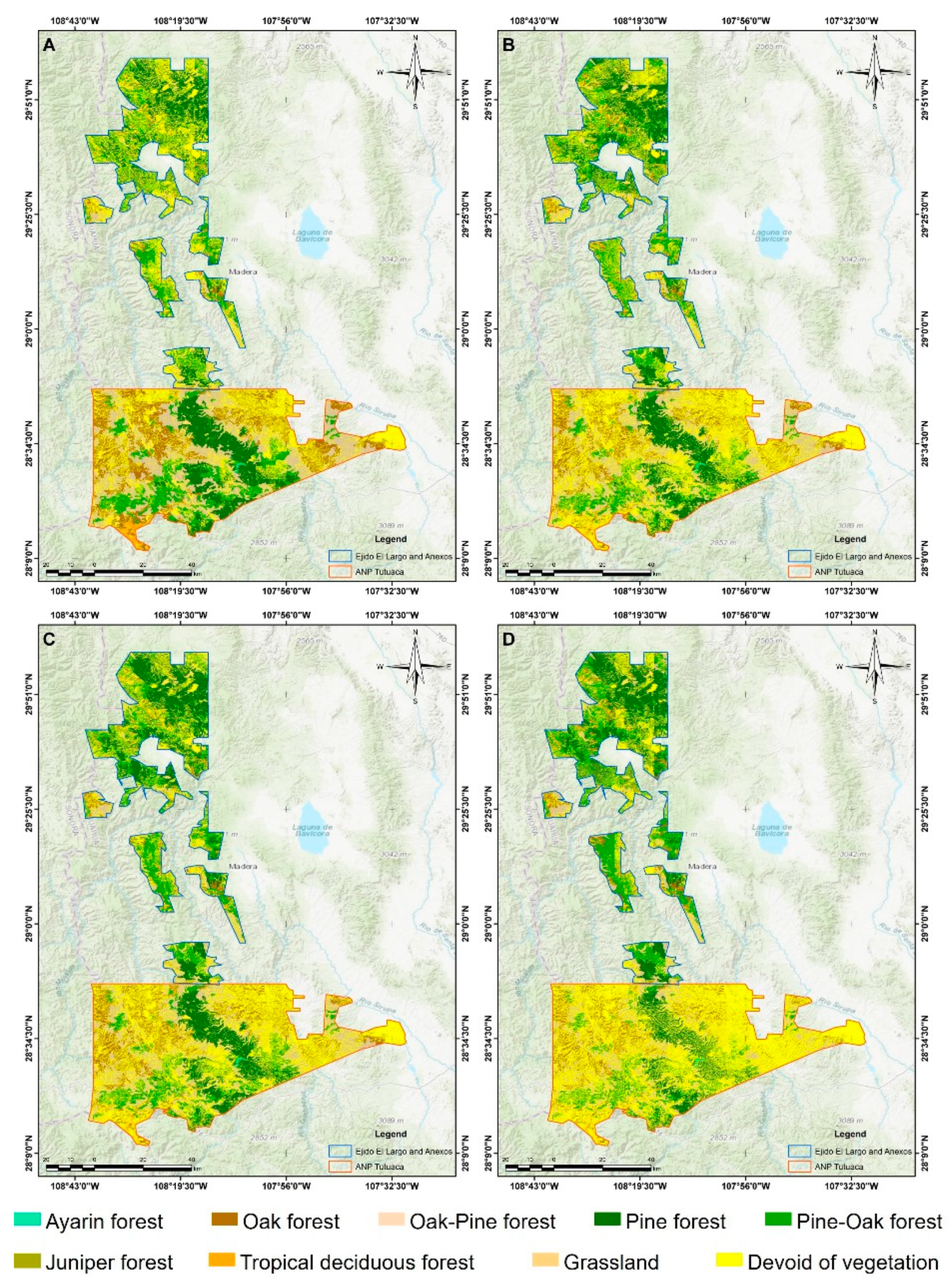

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

References

- Bera, D.; Chatterjee, N.D.; Ghosh, S.; Dinda, S.; Bera, S.; Mandal, M. Assessment of forest cover loss and impacts on ecosystem services: Coupling of remote sensing data and people's perception in the dry deciduous forest of West Bengal, India. Journal of Cleaner Production 2022, 356, 131763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, L.; Wang, L.; Chen, W.; Sun, J.; Cao, Q.; Wang, S.; Wang, L. Identifying the impacts of natural and human factors on ecosystem service in the Yangtze and Yellow River Basins. Journal of Cleaner Production 2021, 314, 127995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Yang, F.; He, F. Reconstruction of Forest and Grassland Cover for the Conterminous United States from 1000 AD to 2000 AD. Remote Sensing 2023, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Ye, Y.; Fang, X.; Li, H.; Wei, X. Synergistic Modern Global 1 Km Cropland Dataset Derived from Multi-Sets of Land Cover Products. Remote Sensing 2019, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FAO. El estado de los bosques del mundo 2020. Los bosques, la biodiversidad y las personas; Roma, Italia, 2020; p. 197 p. [Google Scholar]

- CONAFOR. Estimación de la tasa de deforestación bruta en México para el período 2001-2018 mediante el método de muestreo. Documento Técnico; Jalisco, México, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Wrońska-Pilarek, D.; Rymszewicz, S.; Jagodziński, A.M.; Gawryś, R.; Dyderski, M.K. Temperate forest understory vegetation shifts after 40 years of conservation. Science of The Total Environment 2023, 895, 165164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nascibem, F.G.; Da Silva, R.F.B.; Viveiro, A.A.; Gonçalves Junior, O. The Role of Private Reserves of Natural Heritage (RPPN) on natural vegetation dynamics in Brazilian biomes. Land Use Policy 2023, 132, 106820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandoval-García, R.; González-Cubas, R.; Jiménez-Pérez, J. Análisis multitemporal del cambio en la cobertura del suelo en la Mixteca Alta Oaxaqueña. Revista Mexicana de Ciencias Forestales 2021, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosero, C.; Otero, X.; Bravo, C.; Frey, C. Multitemporal Incidence of Landscape Fragmentation in a Protected Area of Central Andean Ecuador. Land 2023, 12, 500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguirre-Calderón, O.A. Manejo forestal en el siglo XXI. Madera y Bosques 2015, 21, 17–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kucsicsa, G.; Bălteanu, D. The influence of man-induced land-use change on the upper forest limit in the Romanian Carpathians. European Journal of Forest Research 2020, 139, 893–914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kouba, Y.; Alados, C.L. Spatio-temporal dynamics of Quercus faginea forests in the Spanish Central Pre-Pyrenees. European Journal of Forest Research 2012, 131, 369–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gopalakrishnan, R.; Kauffman, J.S.; Fagan, M.E.; Coulston, J.W.; Thomas, V.A.; Wynne, R.H.; Fox, T.R.; Quirino, V.F. Creating Landscape-Scale Site Index Maps for the Southeastern US Is Possible with Airborne LiDAR and Landsat Imagery. Forests 2019, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solberg, S.; Kvaalen, H.; Puliti, S. Age-independent site index mapping with repeated single-tree airborne laser scanning. Scandinavian Journal of Forest Research 2019, 34, 763–770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bontemps, J.-D.; Bouriaud, O. Predictive approaches to forest site productivity: recent trends, challenges and future perspectives. Forestry: An International Journal of Forest Research 2014, 87, 109–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodbody, T.R.H.; Coops, N.C.; Luther, J.E.; Tompalski, P.; Mulverhill, C.; Frizzle, C.; Fournier, R.; Furze, S.; Herniman, S. Airborne laser scanning for quantifying criteria and indicators of sustainable forest management in Canada. Canadian Journal of Forest Research 2021, 51, 972–985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tompalski, P.; Coops, N.C.; White, J.C.; Wulder, M.A.; Pickell, P.D. Estimating Forest Site Productivity Using Airborne Laser Scanning Data and Landsat Time Series. Canadian Journal of Remote Sensing 2015, 41, 232–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blaga, L.; Ilieș, D.C.; Wendt, J.A.; Rus, I.; Zhu, K.; Dávid, L.D. Monitoring Forest Cover Dynamics Using Orthophotos and Satellite Imagery. Remote Sensing 2023, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Li, M.; Li, Y. Improving estimation of forest aboveground biomass using Landsat 8 imagery by incorporating forest crown density as a dummy variable. Canadian Journal of Forest Research 2019, 50, 390–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, L.; Li, Z.; Liu, X.; Zhu, L.; Tang, Y.; Zhang, B.; Xu, B.; Liu, M.; Meng, Y.; Liu, B. Multi-Type Forest Change Detection Using BFAST and Monthly Landsat Time Series for Monitoring Spatiotemporal Dynamics of Forests in Subtropical Wetland. Remote Sensing 2020, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elhag, M.; Boteva, S.; Al-Amri, N. Forest cover assessment using remote-sensing techniques in Crete Island, Greece. 2021, 13, 345–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erfanifard, Y.; Lotfi Nasirabad, M.; Stereńczak, K. Assessment of Iran’s Mangrove Forest Dynamics (1990–2020) Using Landsat Time Series. Remote Sensing 2022, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández-Cavazos, M.C.; Sandoval-García, R.; Molina-Guerra, V.M.; Alanís-Rodríguez, E. Análisis multitemporal del cambio de uso de suelo en el municipio de Linares, Nuevo León. Ecosistemas y Recursos Agropecuarios 2023, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Estrada-Murrieta, Ó.; Rodríguez-García, S.G. Más de 100 años de cultivo al bosque en Chihuaua. Caso Ejido El Largo y Anexos. 2022; p. 143 p. [Google Scholar]

- CONANP. Programa de Manejo Área de Protección de Flora y Fauna Tutuaca; 2014; p. 162 p. [Google Scholar]

- Gao, J.; O’Neill, B.C. Mapping global urban land for the 21st century with data-driven simulations and Shared Socioeconomic Pathways. Nature Communications 2020, 11, 2302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liang, X.; Guan, Q.; Clarke, K.C.; Liu, S.; Wang, B.; Yao, Y. Understanding the drivers of sustainable land expansion using a patch-generating land use simulation (PLUS) model: A case study in Wuhan, China. Computers, Environment and Urban Systems 2021, 85, 101569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Li, X.; Zhang, C.; Yu, L.; Wang, J.; Wu, X.; Hu, Z.; Zhai, Z.; Li, Q.; Wu, G.; et al. Assessing spatiotemporal variations and predicting changes in ecosystem service values in the Guangdong–Hong Kong–Macao Greater Bay Area. GIScience & Remote Sensing 2022, 59, 184–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuervo-Robayo, A.P.; Téllez-Valdés, O.; Gómez-Albores, M.A.; Venegas-Barrera, C.S.; Manjarrez, J.; Martínez-Meyer, E. An update of high-resolution monthly climate surfaces for Mexico. International Journal of Climatology 2014, 34, 2427–2437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hastie, T.; Tibshirani, R.; Friedman, J. The Elements of Statistical Learning. 2009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- QGIS Development Team. QGIS Geographic Information System. Available online: https://qgis.org (accessed on.

- INEGI. Conjunto de datos vectoriales de uso del suelo y vegetación. Escala 1:250, 000. Serie VII (Conjunto Nacional). 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Palacio-Prieto, J.L.; Sánchez-Salazar, T.M.; Casado-Izquierdo, J.M.; Propin-Frejomil, E.; Delgado-Campos, J.; Velázquez-Montes, A.; Chias-Becerril, L.; Ortiz-Álvarez, M.I.; González-Sánchez, J.; Negrete-Fernández, G.; et al. Indicadores para la caracterización y el ordenamiento territorial; Instituto Nacional de Ecología, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Meshesha, T.W.; Tripathi, S.; Khare, D. Analyses of land use and land cover change dynamics using GIS and remote sensing during 1984 and 2015 in the Beressa Watershed Northern Central Highland of Ethiopia. Modeling Earth Systems and Environment 2016, 2, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puyravaud, J.-P. Standardizing the calculation of the annual rate of deforestation. Forest ecology and management 2003, 177, 593–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brennan, R.L.; Prediger, D.J. Coefficient kappa: Some uses, misuses, and alternatives. Educational and psychological measurement 1981, 41, 687–699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feizizadeh, B.; Darabi, S.; Blaschke, T.; Lakes, T. QADI as a New Method and Alternative to Kappa for Accuracy Assessment of Remote Sensing-Based Image Classification. Sensors 2022, 22, 4506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feizizadeh, B.; Blaschke, T.; Tiede, D.; Moghaddam, M.H.R. Evaluating fuzzy operators of an object-based image analysis for detecting landslides and their changes. Geomorphology 2017, 293, 240–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kvålseth, T.O. Measurement of Interobserver Disagreement: Correction of Cohen’s Kappa for Negative Values. Journal of Probability and Statistics 2015, 2015, 751803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foody, G.M. Explaining the unsuitability of the kappa coefficient in the assessment and comparison of the accuracy of thematic maps obtained by image classification. Remote Sensing of Environment 2020, 239, 111630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verma, P.; Raghubanshi, A.; Srivastava, P.K.; Raghubanshi, A. Appraisal of kappa-based metrics and disagreement indices of accuracy assessment for parametric and nonparametric techniques used in LULC classification and change detection. Modeling Earth Systems and Environment 2020, 6, 1045–1059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiménez-Pérez, J.; Sandoval-García, R.; Alanís-Rodríguez, E.; Yerena-Yamallel, J.I.; Aguirre-Calderón, O.A. Dinámica de cambio en ecosistemas urbanos y periurbanos en el área metropolitana de Monterrey, México. Revista Cubana de Ciencias Forestales 2022, 10, 278–291. [Google Scholar]

- Mendes, D.F.; Da Silva, S.; Ferreri, J.; Dos Santos, A.; García, R.F. Acurácia temática do classificador por máxima verossimilhança em imagem de alta resolução espacial do satélite Geoeye-1. Nucleus 2015, 12, 107–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamel, M. Monitoring of Land Use and Land Cover Change Detection Using Multi-temporal Remote Sensing and Time Series Analysis of Qena-Luxor Governorates (QLGs), Egypt. Journal of the Indian Society of Remote Sensing 2020, 48, 1767–1785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vivekananda, G.N.; Swathi, R.; Sujith, A. RETRACTED ARTICLE: Multi-temporal image analysis for LULC classification and change detection. European Journal of Remote Sensing 2021, 54, 189–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira-Andreoli, E.Z.; Moraes, M.C.P.d.; Faustino, A.d.S.; Vasconcelos, A.F.; Costa, C.W.; Moschini, L.E.; Melanda, E.A.; Justino, E.A.; Di Lollo, J.A.; Lorandi, R. Multi-temporal analysis of land use land cover interference in environmental fragility in a Mesozoic basin, southeastern Brazil. Groundwater for Sustainable Development 2021, 12, 100536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meli Fokeng, R.; Gadinga Forje, W.; Meli Meli, V.; Nyuyki Bodzemo, B. Multi-temporal forest cover change detection in the Metchie-Ngoum Protection Forest Reserve, West Region of Cameroon. The Egyptian Journal of Remote Sensing and Space Science 2020, 23, 113–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anzoategui, L.V.; Gil-Leguizamón, P.A.; Sanabria-Marin, R. Frontera agrícola y multitemporalidad de cobertura vegetal en Páramo del Parque Regional Natural Cortadera (Boyacá, Colombia). Bosque (Valdivia) 2023, 44, 159–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallardo-Cruz, J.A.; Peralta-Carreta, C.; Solórzano, J.V.; Fernández-Montes de Oca, A.I.; Nava, L.F.; Kauffer, E.; Carabias, J. Deforestation and trends of change in protected areas of the Usumacinta River basin (2000–2018), Mexico and Guatemala. Regional Environmental Change 2021, 21, 97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, T.R.; Minteer, B.A.; Malan, L.-C. The new conservation debate: The view from practical ethics. Biological Conservation 2011, 144, 948–957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S.; Shwetank, *!!! REPLACE !!!*; Jain, K. A Multi-Temporal Landsat Data Analysis for Land-use/Land-cover Change in Haridwar Region using Remote Sensing Techniques. Procedia Computer Science 2020, 171, 1184–1193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bocco, G.; Mendoza, M.; Masera, O.R. La dinámica del cambio del uso del suelo en Michoacán. Una propuesta metodológica para el estudio de los procesos de deforestación. Investigaciones Geográficas 2001, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castelán Vega, R.; Ruiz Careaga, J.; Linares Fleites, G.; Pérez Avilés, R.; Tamariz Flores, V. Dinámica de cambio espacio-temporal de uso del suelo de la subcuenca del río San Marcos, Puebla, México. Investigaciones Geográficas 2009, 0. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rascón Solano, J.; Galván Moreno, V.S.; Aguirre Calderón, O.A.; García García, S.A. Caracterización estructural y carbono almacenado en un bosque templado frío censado en el noroeste de México. Revista Mexicana de Ciencias Forestales 2022, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García García, S.A.; Alanís Rodríguez, E.; Aguirre Calderón, O.A.; Treviño Garza, E.J.; Graciano Ávila, G. Regeneración y estructura vertical de un bosque de Pseudotsuga menziesii (Mirb.) Franco en Chihuahua, México. Revista Mexicana de Ciencias Forestales 2020, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, Y.; Wang, X.; Wei, Y. Land use change analysis of Daishan Island using multi-temporal remote sensing imagery. Arabian Journal of Geosciences 2020, 13, 741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azari, M.; Billa, L.; Chan, A. Multi-temporal analysis of past and future land cover change in the highly urbanized state of Selangor, Malaysia. Ecological Processes 2022, 11, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dangulla, M.; Manaf, L.A.; Mohammad, F.R. Spatio-temporal analysis of land use/land cover dynamics in Sokoto Metropolis using multi-temporal satellite data and Land Change Modeller. 2020 2020, 52, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capolupo, A.; Monterisi, C.; Saponaro, M.; Tarantino, E. Multi-temporal analysis of land cover changes using Landsat data through Google Earth Engine platform; SPIE, 2020; Volume 11524. [Google Scholar]

- Figueredo Fernández, J.L.; Ramon Puebla, A.M.; Barrero Medel, H. Análisis multitemporal del cambio de cobertura vegetal en el área de manejo "Los Números" Guisa, Granma. Revista Cubana de Ciencias Forestales 2020, 8, 1–15. [Google Scholar]

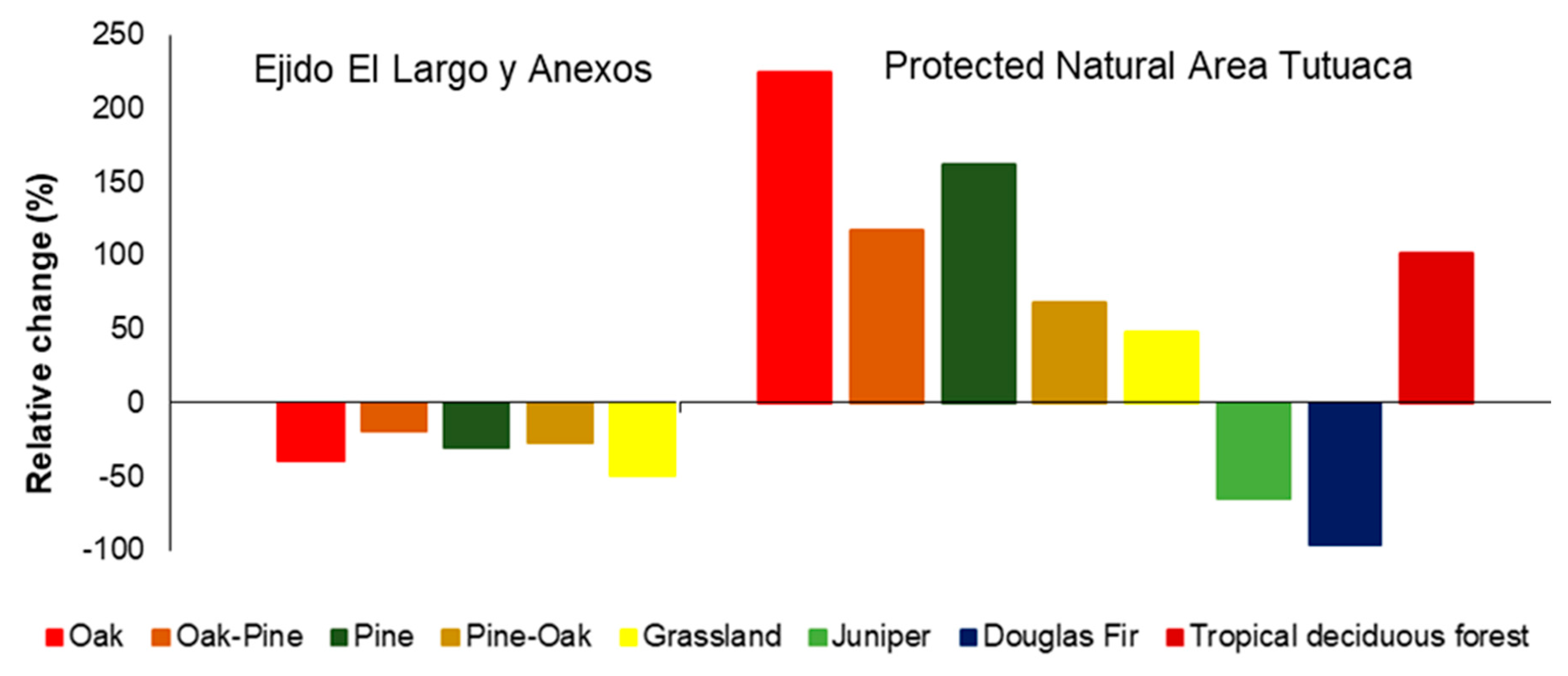

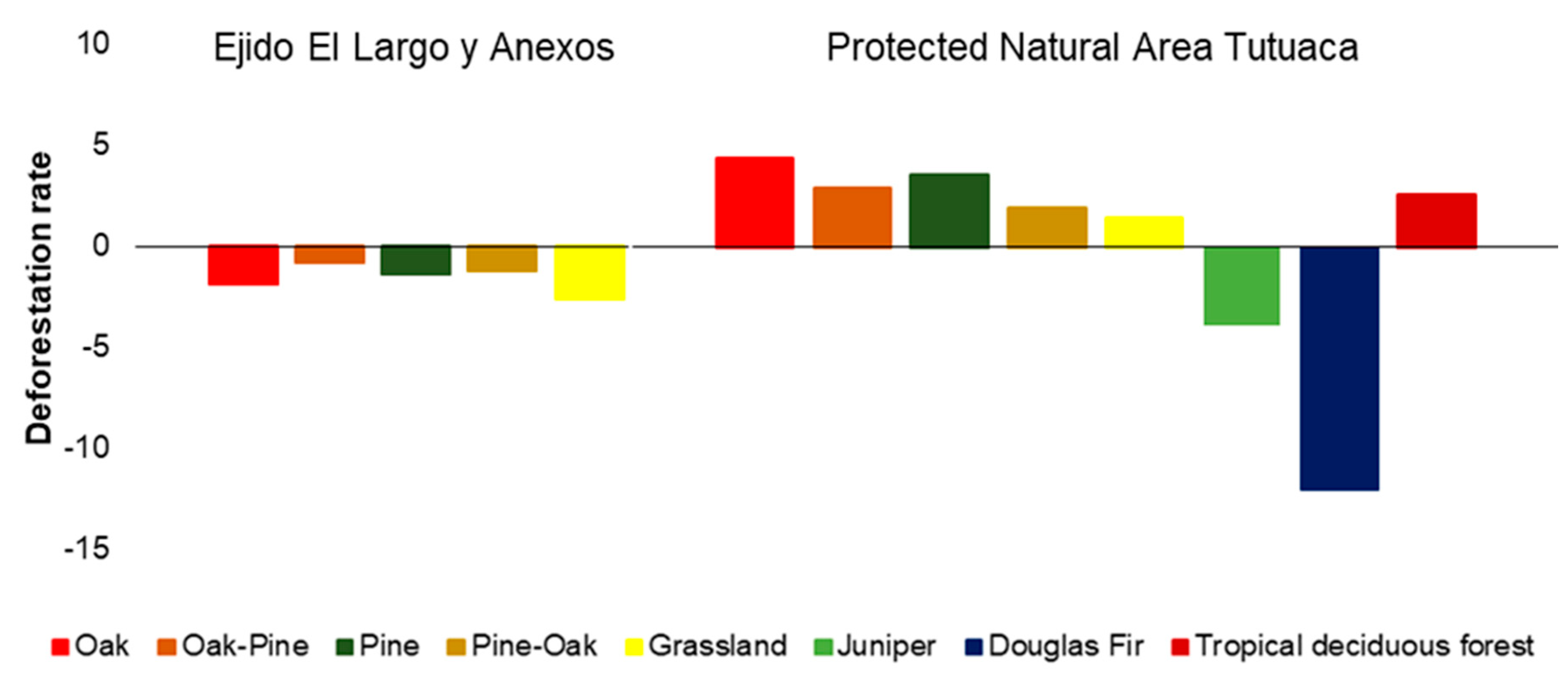

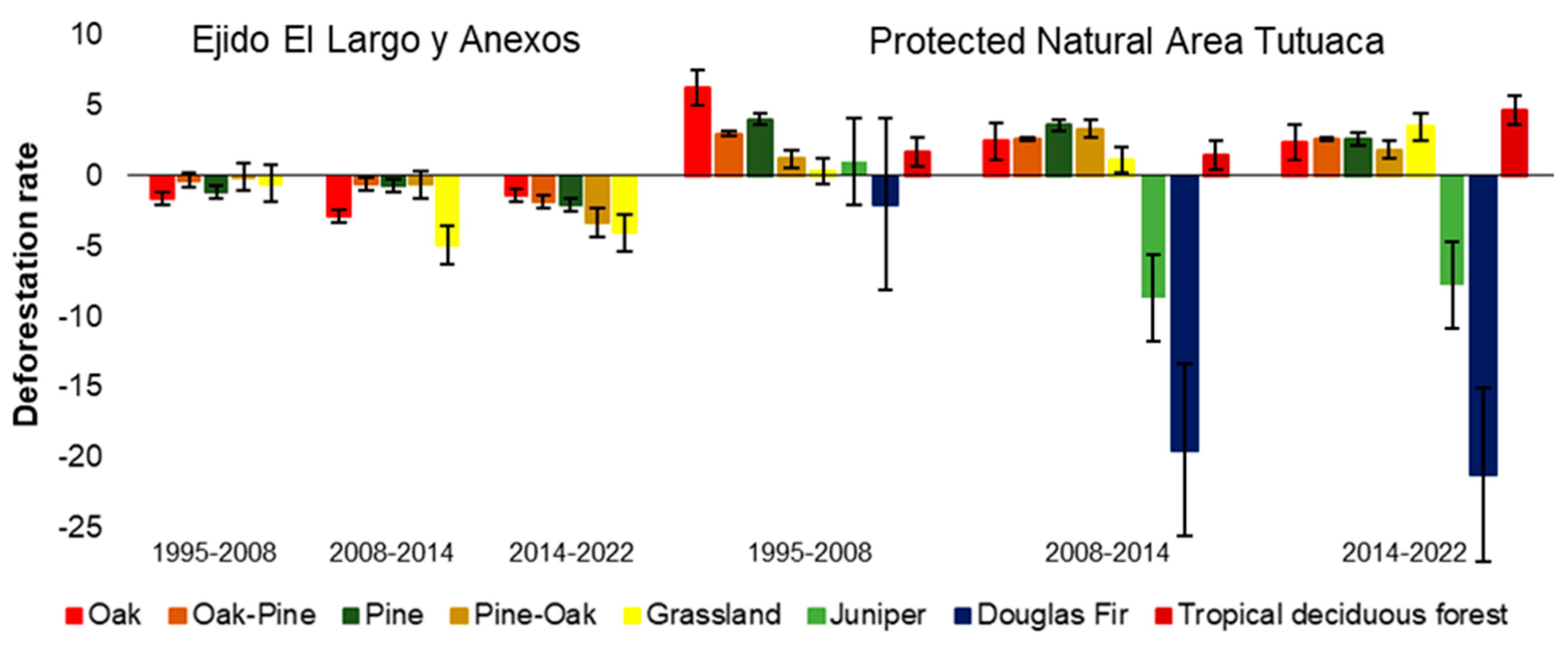

| Ecosystem | 1995 | 2008 | 2014 | 2022 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ha | % | ha | % | ha | % | ha | % | |

| Ejido El Largo y Anexos | ||||||||

| Oak | 23,972 | 22.81 | 19,325 | 20.32 | 16,237 | 18.38 | 14,501 | 19.89 |

| Oak-Pine | 13,969 | 13.29 | 13,421 | 14.11 | 12,972 | 14.69 | 11,230 | 15.40 |

| Pine | 29,915 | 28.46 | 25,708 | 27.03 | 24,643 | 27.90 | 20,871 | 28.62 |

| Pine-Oak | 33,323 | 31.71 | 32,986 | 34.69 | 31,755 | 35.95 | 24,347 | 33.39 |

| Grassland | 3,922 | 3.73 | 3,657 | 3.85 | 2,716 | 3.08 | 1,965 | 2.69 |

| Summation | 105,101 | 100.00 | 95,097 | 100.00 | 88,323 | 100.00 | 72,914 | 100.00 |

| Protected Natural Area Tutuaca | ||||||||

| Douglas Fir | 242 | 0.27 | 184 | 0.13 | 56 | 0.03 | 10 | 0.00 |

| Oak | 22,621 | 25.55 | 51,981 | 36.75 | 60,354 | 36.38 | 73,249 | 35.93 |

| Oak-Pine | 28,770 | 32.49 | 42,824 | 30.28 | 50,296 | 30.32 | 62,442 | 30.63 |

| Pine | 8,461 | 9.55 | 14,373 | 10.16 | 17,896 | 10.79 | 22,135 | 10.86 |

| Pine-Oak | 15,880 | 17.93 | 18,648 | 13.19 | 22,879 | 13.79 | 26,621 | 13.06 |

| Juniper | 7 | 0.01 | 8 | 0.01 | 5 | 0.00 | 2 | 0.00 |

| Grassland | 11,085 | 12.52 | 11,547 | 8.16 | 12,374 | 7.46 | 16,413 | 8.05 |

| Tropical deciduous forest | 1,487.83 | 1.68 | 1,865.96 | 1.32 | 2,044.22 | 1.23 | 2,998 | 1.47 |

| Summation | 88,553.85 | 100.00 | 141,430.13 | 100.00 | 165,903.94 | 100.00 | 203,870 | 100.00 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).