Preprint

Article

The Effect of Glutathione on Recurrence and Progression in Non-Muscle Invasive Bladder Cancer

This version is not peer-reviewed.

Submitted:

22 July 2024

Posted:

23 July 2024

You are already at the latest version

A peer-reviewed article of this preprint also exists.

Abstract

Background: Glutathione and its related enzymes constitute one of the most important antioxidant defense mechanisms against oxidative stress and cancer formation in the body. Bladder cancer is the second most common urological malignancy after prostate cancer. Oxidative stress plays a significant role in the development and prognosis of bladder cancer. The aim of this study was to examine the effect of glutathione on the prognosis of non-muscle-invasive bladder cancer.

Methods: The 98 patients with bladder tumors were those with T1G3 pathology who had undergone intravesical Bacillus Calmette-Guérin therapy, while the 30 controls were healthy individuals with no history of transitional cell carcinoma of the bladder. The 128 participants were divided into four groups: Group 1 comprised 41 patients who did not experience recurrence during follow-up, Group 2 included 28 patients who had recurrent tumors, Group 3 consisted of 29 patients who progressed to muscle-invasive stages, and Group 4 was composed of 30 healthy volunteers. Blood samples were collected from all participants. Glutathione levels were measured, and statistical analysis were performed.

Results: There was a statistically significant difference in reduced glutathione levels among the groups (p < 0.001), attributed to Group 4 exhibiting higher reduced glutathione levels compared to Groups 1, 2, and 3 (p < 0.001). No significant differences were observed in reduced glutathione levels between Groups 1 and 2, Groups 1 and 3, or Groups 2 and 3 (p > 0.999). Total glutathione levels varied significantly among the groups (p < 0.001), with Group 4 having higher levels than Groups 1, 2, and 3 (p < 0.001). However, there were no significant differences between Groups 1 and 2, Groups 1 and 3, or Groups 2 and 3 in terms of total glutathione levels (p = 0.473, p = 0.747, and p > 0.999, respectively). Regarding oxidized glutathione levels, a significant difference was observed (p < 0.001), with Group 4 showing lower levels than the remaining three groups (p < 0.001). No significant differences were found between Groups 1 and 2, Groups 1 and 3, or Groups 2 and 3 in relation to oxidized glutathione levels (p > 0.999, p = 0.171, and p > 0.999, respectively).

Conclusions: The current study revealed that glutathione is a factor influencing the development of new bladder cancer but did not affect its prognosis. Nevertheless, we recommend that future studies with larger bladder cancer patient cohorts should be conducted to comprehensively determine the effect of glutathione on the prognosis of bladder cancer.

Keywords:

Bladder cancer

; Oxidative stress

; Glutathione

; Oxidants-antioxidants

; 1. Introduction

Glutathione (L-gamma-glutamyl-L-cysteinyl glycine) is a crucial antioxidant that protects cells from the toxic effects of peroxides, free radicals, and heavy metals. It is a tripeptide composed of cysteine, glutamic acid, and glycine. As one of the most abundant intracellular antioxidants, glutathione is predominantly found in the liver but is also present in all tissues and organs. Glutathione exists in both reduced (GSH) and oxidized (GSSG) forms, with over 90% typically in the active GSH form. An increased GSSG/GSH ratio is indicative of oxidative stress. GSSG is converted back to GSH by the enzyme glutathione reductase [1]. Other enzymes also play vital roles in maintaining glutathione activity. For example, glutathione peroxidase (GPX) is an enzyme responsible for reducing hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) and organic peroxides (GSH + H2O2 →SSG + 2H2O, GSH + ROOH → GSSG + H2O), existing in selenium-dependent and selenium-independent forms. The selenium-dependent enzyme reduces H2O2 and lipid hydroperoxides, whereas the selenium-independent enzyme only reduces lipid hydroperoxides. To date, eight different isoenzymes of this enzyme, encoded by distinct genetic loci, have been identified (GPX 1-8) [2]. Another enzyme, Glutathione-S-transferase (GSTs), is a phase 2 detoxifying enzyme responsible for the elimination of xenobiotics (environmental carcinogens, drug metabolites, chemotherapeutics, pesticides, herbicides, food preservatives, sweeteners, etc.). This enzyme also requires GSH to perform its function. GSTs catalyze the conjugation of xenobiotics with GSH, preventing damage to essential intracellular proteins and nucleic acids. Sixteen genes expressed on seven different chromosomes result in eight distinct cytosolic GSTs isoenzymes, with GST alpha, mu, pi, and theta being the most well-known [3].

According to GLOBOCAN data, bladder cancer is the second most common urological malignancy after prostate cancer, with over 600,000 cases diagnosed globally in 2022 and more than 220,000 deaths attributed to the disease in the same year [4]. The incidence of bladder cancer varies between countries due to differences in risk factors and healthcare systems. Risk factors implicated in the development of this cancer include tobacco smoking, dietary habits, genetic predispositions, occupational and environmental exposure to carcinogens, and oxidative stress. Several studies suggest that oxidative stress plays a significant role in the development and prognosis of bladder cancer [5,6,7,8]. For instance, in a study comparing patients with bladder cancer to healthy volunteers in terms of oxidative stress markers, such as plasma protein carbonyls, thiol groups, lipid peroxidation, and DPPH· and ABTS·+ radicals, Wigner et al. reported that all these markers were higher in the bladder cancer group compared to the control group [8]. Similarly, within the bladder cancer group itself, individuals with high-grade tumors exhibited higher levels of these markers compared to those with low-grade tumors, suggesting that oxidative stress might influence the development and prognosis of bladder cancer [8].

This study aimed to examine the effect of glutathione, one of the most important antioxidants, on the prognosis of non-muscle-invasive bladder cancer (NMIBC). To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to investigate the relationship between glutathione levels and the prognosis of NMIBC.

2. Materials and Methods

Following approval from the local ethics committee (decision number: 131/09), this study included 98 patients diagnosed with bladder tumors and 30 healthy individuals as a control group, all treated and monitored at the Urology Clinic of the Health Sciences University Diskapi Yildirim Beyazit Training and Research Hospital. The 98 patients with bladder tumors were those with T1G3 pathology who had undergone intravesical Bacillus Calmette-Guérin (BCG) therapy, while the 30 controls were healthy individuals with no history of transitional cell carcinoma of the bladder. The 128 participants were divided into four groups: Group 1 comprised 41 patients who did not experience recurrence during follow-up, Group 2 included 28 patients who had recurrent tumors, Group 3 consisted of 29 patients who progressed to muscle-invasive stages, and Group 4 was composed of 30 healthy volunteers.

Blood samples (3 mL) were collected from all participants to measure GSH, GSSG, and total glutathione levels. The study utilized various chemical reagents and solutions from Sigma-Aldrich, including 5,5′-Dithiobis (2-nitrobenzoic acid) (DTNB, Ellman’s reagent), methanol, ethylenediamine tetraacetic acid (EDTA), Tris, hydrochloric acid (HCl), trichloroacetic acid (TCA), sodium borohydride (NaBH4), sodium hydroxide (NaOH) and sodium chloride. Measurements were conducted using a Siemens Advia 1800® (Siemens Healthineers, Erlangen, Germany) device. A novel method described by Alışık et al. was employed to measure glutathione levels [9]. Samples were washed with a 0.9% NaCl solution, lysed with distilled water, and proteins were precipitated using a 20% TCA solution. TCA-treated samples were reduced with NaBH4 and NaOH, and the pH was adjusted using NaOH. Excess NaBH4 was neutralized with HCl to prevent further reduction of DTNB molecules and reoxidation of glutathione. NaBH4 was used as a reductant. After the reduction process was completed, an HCl solution was added to remove the remaining NaBH4 to prevent further reduction of DTNB molecules and re-oxidation of glutathione molecules. Glutathione levels were measured using the Ellman method, modified by Hu, with a 500 mM Tris solution (pH: 8.2). In this method, the thiol residues of glutathione reduce DTNB molecules to 2-nitro-5-benzoic acid. Glutathione levels were measured before and after the reduction process. The GSSG levels were calculated by subtracting the GSH levels from the total measured glutathione levels and then dividing the result by two.

Statistical Analysis

Kolmogorov-Smirnov and Levene’s tests were used to investigate whether the assumptions of the normality of data distribution and homogeneity of variances were met. Categorical data were expressed as numbers (n) and percentages (%), while the quantitative data were given as mean ± standard deviation or median (25th–75th) percentiles. The mean differences in ages among groups were evaluated using the one-way analysis of variance test. The Fisher-Freeman-Halton test was applied for the comparison of the gender distribution. The Kruskal-Wallis test was employed to determine the significance of differences in GSH, GSSG, and total glutathione levels among groups. When the p-values from the Kruskal-Wallis test statistics were statistically significant, the Dunn-Bonferroni multiple comparison test was conducted to ascertain the group that caused the difference. Data analysis was performed using IBM SPSS Statistics version 25 (IBM Corporation, Armonk, NY, US) package program. A p-value less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

3. Results

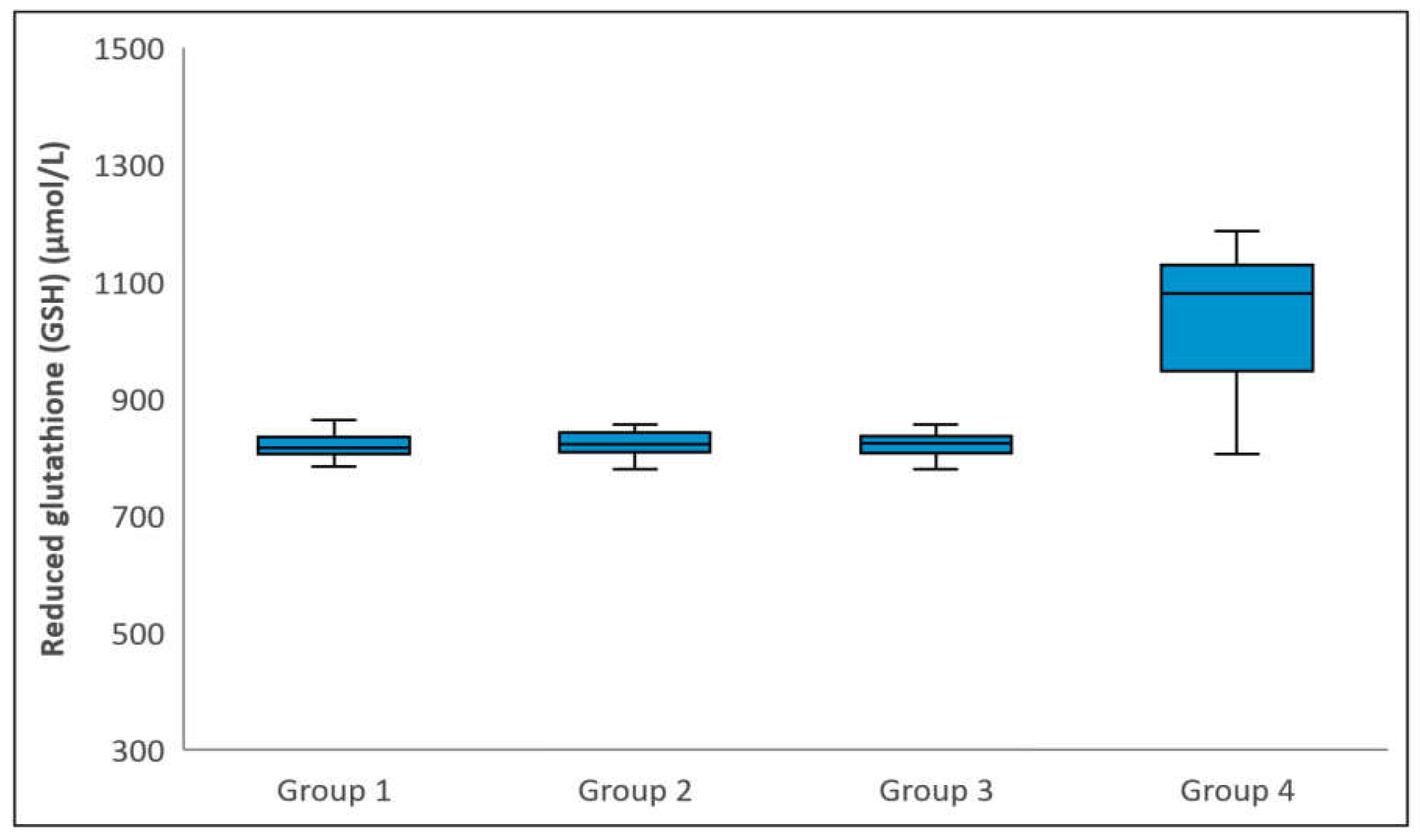

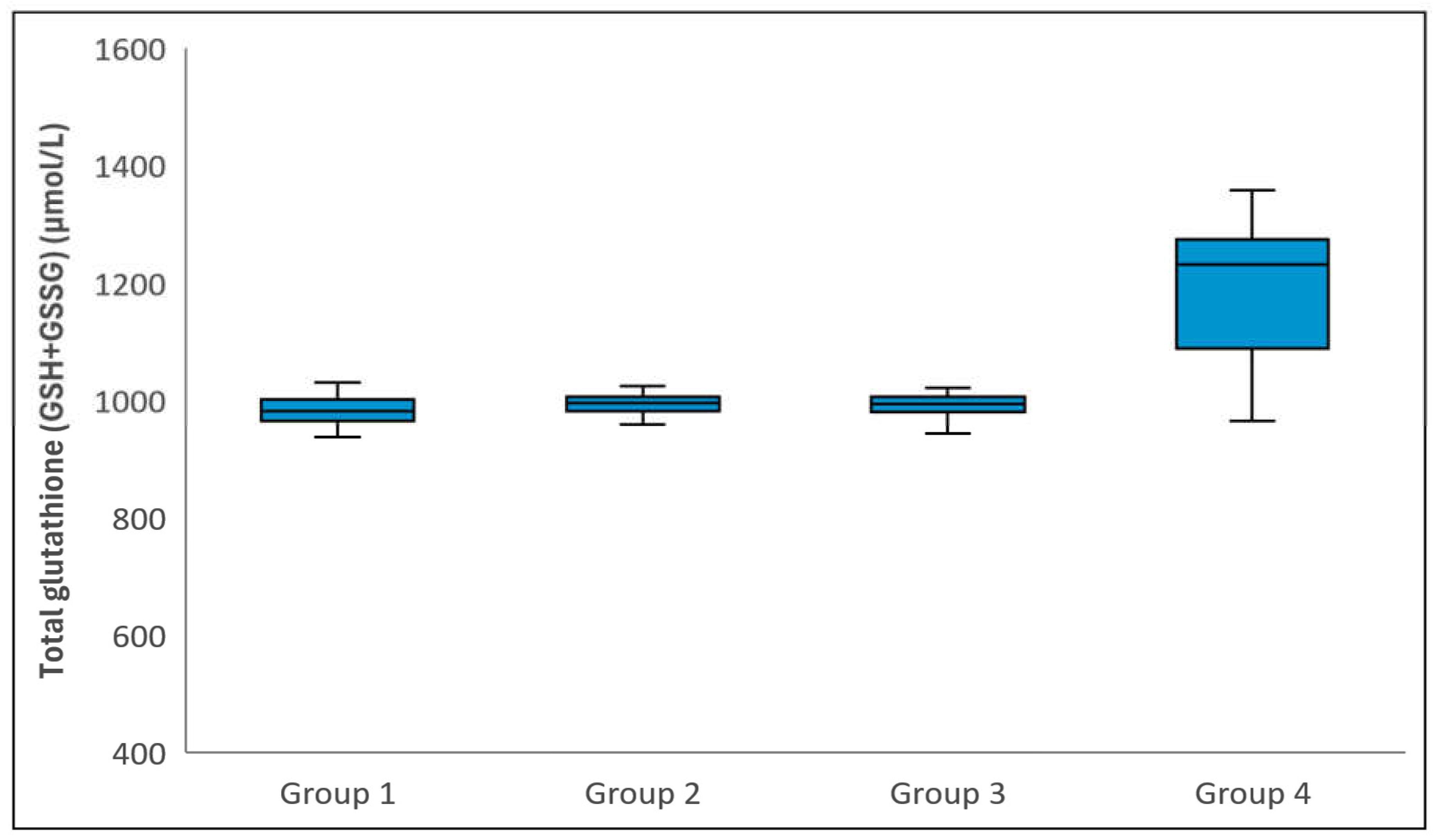

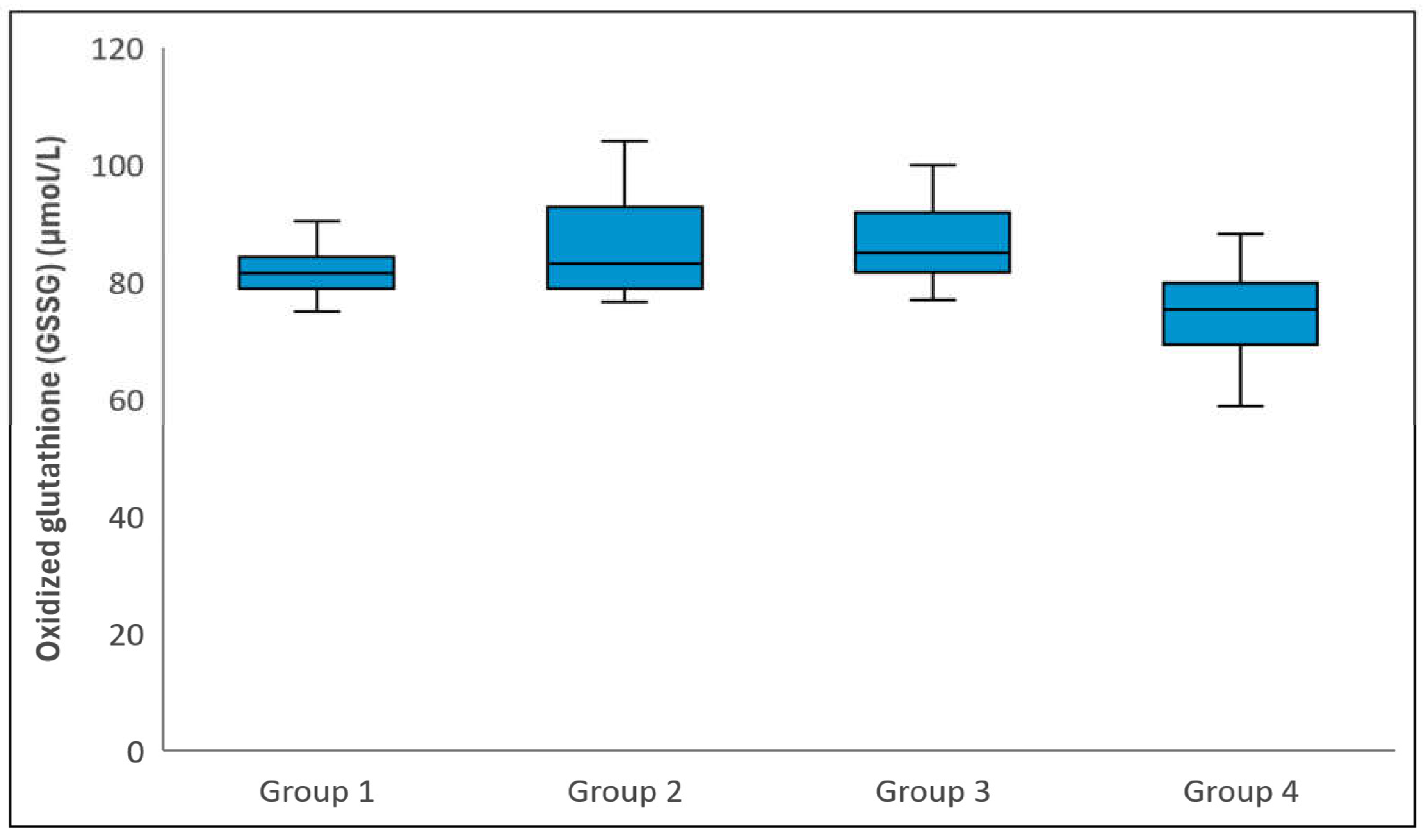

Statistical analysis revealed no significant differences between the groups in terms of the mean age or gender distribution (p = 0.310 and p = 0.376, respectively). However, there was a statistically significant difference in GSH levels among the groups (p < 0.001), attributed to Group 4 exhibiting higher GSH levels compared to Groups 1, 2, and 3 (p < 0.001). No significant differences were observed in GSH levels between Groups 1 and 2, Groups 1 and 3, or Groups 2 and 3 (p > 0.999) (Figure 1). Total glutathione levels varied significantly among the groups (p < 0.001), with Group 4 having higher levels than Groups 1, 2, and 3 (p < 0.001). However, there were no significant differences between Groups 1 and 2, Groups 1 and 3, or Groups 2 and 3 in terms of total glutathione levels (p = 0.473, p = 0.747, and p > 0.999, respectively) (Figure 2). Regarding GSSG levels, a significant difference was observed (p < 0.001), with Group 4 showing lower levels than the remaining three groups (p < 0.001). No significant differences were found between Groups 1 and 2, Groups 1 and 3, or Groups 2 and 3 in relation to GSSG levels (p > 0.999, p = 0.171, and p > 0.999, respectively) (Figure 3). Table 1 provides a comparative analysis of demographic characteristics and biochemical measurements across the groups.

4. Discussion

Bladder cancer is one of the most common urogenital malignancies, predominantly presenting as NMIBC at initial diagnosis. NMIBC can be stratified into low, intermediate, and high-risk categories based on recurrence and progression probabilities. For patients with high-risk NMIBC characterized by T1G3 pathology, adjuvant intravesical BCG therapy is the standard to improve prognosis. However, intravesical BCG can lead to severe adverse effects and, occasionally, mortality. Despite BCG therapy, which is associated with serious side effects, the majority of patients still experience tumor recurrence, and a significant portion progress to more advanced tumor stages. Interestingly, patients initially diagnosed with NMIBC who progress to the muscle-invasive bladder cancer (MIBC) stage during follow-up have a worse prognosis and survival rate compared to those diagnosed with MIBC at the time of diagnosis [10]. This underscores the importance of identifying new predictive factors for determining the prognosis in high-risk NMIBC patients. Currently, clinical and pathological data, such as concurrent CIS, T category, tumor grade, gender, age, number of tumors, tumor diameter, and prior recurrence rate are utilized for the assessment of NMIBC prognosis. However, it is clear that the development of new markers in addition to these clinicopathological factors is necessary to enhance the accuracy of prognostic prediction.

Given the bladder’s role as a reservoir for urine, it is exposed to oxidative waste for prolonged periods. Publications indicate significant roles of antioxidant mechanisms in the development and prognosis of bladder cancer [5,6,7,8]. Glutathione and related enzymes constitute one of the body’s most crucial antioxidant defense systems. Several studies have examined the effects of these enzymes and their genetic variants on bladder cancer prognosis [7,11,12]. For instance, in a study of 112 patients with bladder cancer, Minato et al. demonstrated that decreased GPX2 expression detected by immunohistochemistry in pathology specimens might be associated with cancer invasion [7]. Another study involving 7,236 patients with bladder cancer identified that the GSTP1 gene 313 A/G (rs1695) polymorphism increased the risk of bladder cancer development [12]. A study reported by MD Anderson Cancer Center investigated the effects of various glutathione pathway genes on the prognosis following NMIBC treatment (transurethral resection [TUR] alone or TUR + BCG) [11]. In that study, 414 patients with NMIBC were individually examined for 114 single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) in 21 glutathione pathway genes, and it was found that seven SNPs were associated with recurrence in the TUR alone group, and 15 SNPs were associated with recurrence in the TUR + BCG group. The likelihood of recurrence increased with an increasing number of unfavorable genotypes in the glutathione pathway in both groups[11] (9). In another study, the genotype of the leucine (Leu) to proline (Pro) polymorphism at codon 198 of GPX1 was determined by PCR in patients with bladder cancer and healthy controls. The study concluded that the Pro/Leu genotype of GPX1 was associated with an increased risk of bladder cancer development compared to the Pro/Pro genotype [13]. Furthermore, within the bladder cancer group, the Pro/Leu genotype of GPX1 was more prevalent in cases with stage T2-4 tumors compared to Ta-1 tumors, indicating its association with advanced tumor stages [13]. Therefore, the Leu allele in GPX1 was identified as a risk allele both for the development of bladder cancer and for having advanced tumor stages in those who developed bladder cancer [13]. Albarakati et al. investigated the effect of genetic variants of phase 2 detoxifying enzymes GSTs on the prognosis of bladder cancer [14]. Genomic DNA was extracted from tissue samples obtained through bladder resection from 93 patients with bladder cancer. The analysis of the extracted samples revealed that the GSTM1 null genotype and GSTP1 (AG/GG) genotype were significantly associated with poor overall survival [14]. These studies underscore the significant role of glutathione metabolism-related enzymes and their genetic variants in the development of bladder cancer.

Despite existing studies on the effects of enzymes responsible for glutathione activity and their genetic variants on bladder cancer, research directly examining the impact of glutathione itself on bladder cancer is limited. One such study by Güneş et al. measured serum GSH levels in patients with bladder cancer and healthy controls, finding significantly lower GSH levels in the former, suggesting the role of oxidative stress in the etiopathogenesis of bladder cancer [15]. However, the study did not assess the impact of GSH on recurrence and progression of bladder cancer [15]. To our knowledge, our study is the first to evaluate the relationship between GSH, GSSG, and total glutathione levels in blood and the recurrence and progression of NMIBC. Our results indicate higher GSH and total glutathione levels in the control group compared to the bladder cancer group, while GSSG levels, an indicator of oxidative stress, were higher in patients with bladder cancer. However, no significant differences were found among the three patient groups (non-recurrent, recurrent, and progressing to muscle-invasive stage) regarding glutathione levels. Thus, our study suggests that disruption in the GSSG/GSH balance, a marker of oxidative stress, may play a role in the etiopathogenesis of bladder cancer development but does not impact its prognosis. The limitations of our study include the relatively small sample size and the timing of blood sample collection not coinciding with initial diagnosis in patients with bladder cancer. Therefore, further prospective studies with larger patient cohorts are warranted to fully elucidate the impact of glutathione on the prognosis of bladder cancer.

5. Conclusions

The identification of new markers to predict the prognosis of bladder cancer is crucial. The current study revealed that glutathione, one of the most important antioxidants, was a factor influencing the new development of bladder cancer but did not affect its prognosis. Nevertheless, we recommend that future studies with larger bladder cancer patient cohorts be conducted to comprehensively determine the effect of glutathione on the prognosis of bladder cancer.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Tarık Küçük; Methodology, Gamze Gök, Alper Gök, Özcan Erel and Muhammet Abdurrahim İmamoğlu; Software, Göksel Göktuğ; Formal analysis, Gamze Gök and Özcan Erel; Investigation, Gamze Gök, Göksel Göktuğ and Özcan Erel; Resources, Tarık Küçük; Data curation, Tarık Küçük and Muhammet Abdurrahim İmamoğlu; Writing – original draft, Gamze Gök, Alper Gök and Muhammet Abdurrahim İmamoğlu; Writing – review & editing, Sertac Cimen; Visualization, Sertac Cimen.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study protocol was approved by University Health Science Diskapi Yildirim Beyazit Training and Research Hospital Ethics Commission (approval code 131/09, date 21 Feb 2022).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Averill-Bates, D.A., The antioxidant glutathione, in Vitamins and hormones. 2023, Elsevier. p. 109-141.

- Flohé, L., S. Toppo, and L. Orian, The glutathione peroxidase family: Discoveries and mechanism. Free Radical Biology and Medicine, 2022. 187: p. 113-122. [CrossRef]

- Vaish, S., et al., Glutathione S-transferase: a versatile protein family. 3 Biotech, 2020. 10: p. 1-19. [CrossRef]

- Ferlay J, E.M., Lam F, Laversanne M, Colombet M, Mery L, Piñeros M, Znaor A, Soerjomataram I, Bray F, GLOBOCAN 2022. Global Cancer Observatory: Cancer Today. Lyon, France: International Agency for Research on Cancer. (30 Jun. 2024).

- Cao, M., et al., Single-nucleotide polymorphisms of GPX1 and MnSOD and susceptibility to bladder cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Tumor Biology, 2014. 35: p. 759-764.

- Ishaq, M., et al., Gambogic acid induced oxidative stress dependent caspase activation regulates both apoptosis and autophagy by targeting various key molecules (NF-κB, Beclin-1, p62 and NBR1) in human bladder cancer cells. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA)-General Subjects, 2014. 1840(12): p. 3374-3384.

- Minato, A., et al., Reduced expression level of GPX2 in T1 bladder cancer and its role in early-phase invasion of bladder cancer. in vivo, 2021. 35(2): p. 753-759. [CrossRef]

- Wigner, P., et al., Oxidative stress parameters as biomarkers of bladder cancer development and progression. Scientific Reports, 2021. 11(1): p. 15134. [CrossRef]

- Alisik, M., S. Neselioglu, and O. Erel, A colorimetric method to measure oxidized, reduced and total glutathione levels in erythrocytes. Journal of Laboratory Medicine, 2019. 43(5): p. 269-277. [CrossRef]

- Lambert, E.H., et al., The increasing use of intravesical therapies for stage T1 bladder cancer coincides with decreasing survival after cystectomy. BJU international, 2007. 100(1): p. 33-36.

- Ke, H.-L., et al., Genetic variations in glutathione pathway genes predict cancer recurrence in patients treated with transurethral resection and bacillus calmette–guerin instillation for non-muscle invasive bladder cancer. Annals of surgical oncology, 2015. 22: p. 4104-4110. [CrossRef]

- Song, Y., et al., Glutathione S-Transferase Pi 1 (GSTP1) Gene 313 A/G (rs1695) polymorphism is associated with the risk of urinary bladder cancer: Evidence from a systematic review and meta-analysis based on 34 case-control studies. Gene, 2019. 719: p. 144077. [CrossRef]

- Ichimura, Y., et al., Increased risk of bladder cancer associated with a glutathione peroxidase 1 codon 198 variant. The Journal of urology, 2004. 172(2): p. 728-732. [CrossRef]

- Albarakati, N., et al., The prognostic impact of GSTM1/GSTP1 genetic variants in bladder cancer. BMC cancer, 2019. 19: p. 1-11.

- Günes, M., et al., Oxidant-antioxidant levels in patients with bladder tumours. The Aging Male, 2020. 23(5): p. 1176-1181. [CrossRef]

Figure 1.

Comparison of Reduced glutathione (i.e. GSH) levels among groups. The horizontal lines in the middle of each box indicate the median, while the top and bottom borders of the box mark the 25th and 75th percentiles, respectively. The whiskers above and below the box mark the maximum and minimum GSH levels.

Figure 1.

Comparison of Reduced glutathione (i.e. GSH) levels among groups. The horizontal lines in the middle of each box indicate the median, while the top and bottom borders of the box mark the 25th and 75th percentiles, respectively. The whiskers above and below the box mark the maximum and minimum GSH levels.

Figure 2.

Comparison of Total glutathione (i.e. GSH+GSSG) levels among groups. The horizontal lines in the middle of each box indicate the median, while the top and bottom borders of the box mark the 25th and 75th percentiles, respectively. The whiskers above and below the box mark the maximum and minimum GSH+GSSG levels.

Figure 2.

Comparison of Total glutathione (i.e. GSH+GSSG) levels among groups. The horizontal lines in the middle of each box indicate the median, while the top and bottom borders of the box mark the 25th and 75th percentiles, respectively. The whiskers above and below the box mark the maximum and minimum GSH+GSSG levels.

Figure 3.

Comparison of Oxidized glutathione (i.e. GSSG) levels among groups. The horizontal lines in the middle of each box indicate the median, while the top and bottom borders of the box mark the 25th and 75th percentiles, respectively. The whiskers above and below the box mark the maximum and minimum GSSG levels.

Figure 3.

Comparison of Oxidized glutathione (i.e. GSSG) levels among groups. The horizontal lines in the middle of each box indicate the median, while the top and bottom borders of the box mark the 25th and 75th percentiles, respectively. The whiskers above and below the box mark the maximum and minimum GSSG levels.

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics and biochemical measurements regarding for study groups.

| Group 1 (n=41) | Group 2 (n=28) | Group 3 (n=29) | Group 4 (n=30) |

p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 66.1±7.3 | 67.4±8.1 | 65.8±9.7 | 63.3±9.0 | 0.310† |

| Gender | 0.376‡ | ||||

| Male | 39 (95.1%) | 26 (92.9%) | 24 (82.8%) | 28 (93.3%) | |

| Female | 2 (4.9%) | 2 (7.1%) | 5 (17.2%) | 2 (6.7%) | |

| Reduced glutathione (GSH) (µmol/L) | 815.5 (804.8-833.5)a | 822.3 (807.8-841.0)b | 822.9 (806.5-835.5)c | 1079.1 (947.5-1128.1)a,b,c | <0.001¶ |

| Total glutathione (GSH+GSSG) (µmol/L) | 980.5 (965.1-1000.8)a | 994.2 (980.5-1005.6)b | 993.0 (980.2-1005.6)c | 1231.8 (1088.0-1274.1)a,b,c | <0.001¶ |

| Oxidized glutathione (GSSG) (µmol/L) | 81.5 (78.8-84.2)a | 83.2 (78.8-92.8)b | 84.9 (81.6-91.8)c | 75.2 (69.2-79.7)a,b,c | <0.001¶ |

Data were displayed as mean ± SD or median (25th – 75th) percentiles; where appropriate. † One-Way ANOVA, ‡ Fisher Freeman Halton test, ¶ Kruskal Wallis test, a: Group 1 vs Group 4 (p<0.001), b: Group 2 vs Group 4 (p<0.001), c: Group 3 vs Group 4 (p<0.001).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Copyright: This open access article is published under a Creative Commons CC BY 4.0 license, which permit the free download, distribution, and reuse, provided that the author and preprint are cited in any reuse.

Downloads

177

Views

96

Comments

0

Subscription

Notify me about updates to this article or when a peer-reviewed version is published.

MDPI Initiatives

Important Links

© 2025 MDPI (Basel, Switzerland) unless otherwise stated