Submitted:

22 July 2024

Posted:

23 July 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

Article Highlights

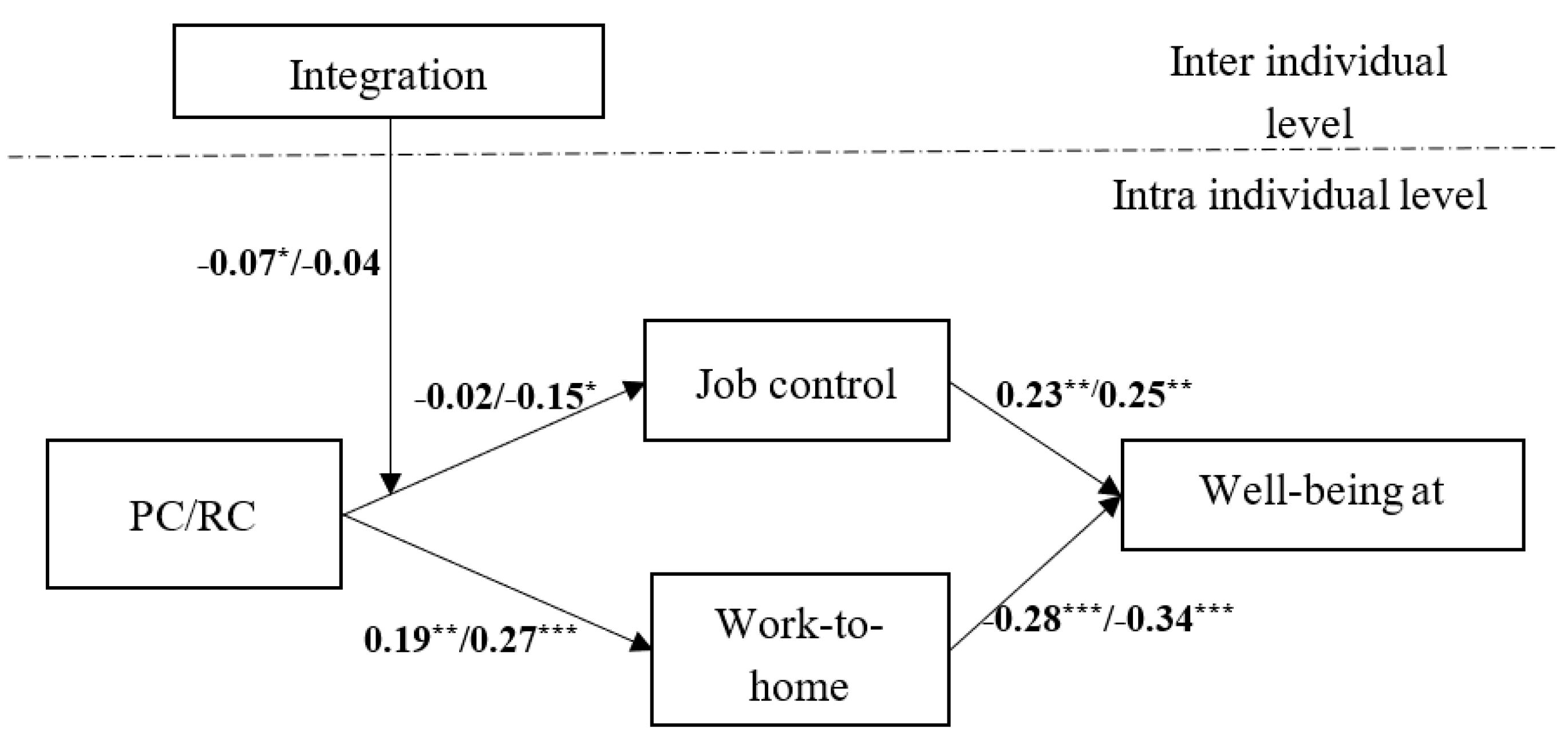

- To clarify the complexity of the impact of WCBA on well-being at work. we divided WCBA into proactive WCBA (PC) and reactive WCBA (RC), and examined the double-edged sword effect of WCBA on well-being at work

- PC has an inverted U-shaped effect on job control.

- Job control and work–to-home conflict mediated the relationship between WCBA and well-being at work.

- Integration preference moderates the mediated effect of the work–to-home conflict of the relationship between work-to-home conflict and PC on well-being at work.

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review and Hypotheses

2.1. PC and RC

2.2. Work Domain Path: PC/RC, Job Control, and Well-Being at Work

2.3. Family Domain Paths: PC/RC, Work-to-Home Conflict, and Well-Being at Work

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Sample and Procedures

3.2. Measurements

4. Results

4.1. Confirmatory Factor Analysis and Common Method Variance

4.2. Descriptive Statistics and Correlations

4.3. Hypothesis Testing

5. Conclusions and Discussion

5.1. Theoretical Contributions

5.2. Practical Implications

6. Limitations and Future Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ren, S.; Hu, J.; Tang, G.; Chadee, D. Digital Connectivity for Work after Hours: Its Curvilinear Relationship with Employee Job Performance. Personnel Psychology 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, F.; Gao, Y.; Chen, X. Freedom or Bondage? The Double-Edged Sword Effect of Work Connectivity Behavior After-Hours on Employee Occupational Mental Health. Chinese Management Studies 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richardson, K.; Benbunan-Fich, R. Examining the Antecedents of Work Connectivity Behavior during Non-Work Time. Information and Organization 2011, 21, 142–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong S, Li H, Xia M, Zhu J. Are You Asked to Work Overtime? Exploring Proactive and Reactive Work Connectivity Behaviors After-hours and Their Multi-path Effects on Emotional Exhaustion[J]. Management Review, 2024, 36(2): 154-166. URL: http://123.57.61.11/jweb_glpl/EN/.

- Yang, Y.; Yan, R.; Meng, Y. Can’t Disconnect Even After-Hours: How Work Connectivity Behavior After-Hours Affects Employees’ Thriving at Work and Family. Frontiers in Psychology 2022, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nurmi, N.; Hinds, P. J. Work Design for Global Professionals: Connectivity Demands, Connectivity Behaviors, and Their Effects on Psychological and Behavioral Outcomes. Organization Studies 2020, 41, 1697–1724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ten Brummelhuis, L. L.; ter Hoeven, C. L.; Toniolo-Barrios, M. Staying in the Loop: Is Constant Connectivity to Work Good or Bad for Work Performance? Journal of Vocational Behavior 2021, 128, 103589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sonnentag, S.; Niessen, C. To Detach or Not to Detach? Two Experimental Studies on the Affective Consequences of Detaching from Work during Non-Work Time. Frontiers in Psychology 2020, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elshaer, I.A., Azazz, A.M.S. and Fayyad, S. 2024. Work-related mobile internet usage during off-job time and quality of life: The role of work family conflict and off-job control. International Journal of Innovative Research and Scientific Studies. 7, 3 (May 2024), 1268–1279. 20 May. [CrossRef]

- Wang, F.; Zhang, Z.; Shi, W. Relationship between Daily Work Connectivity Behavior after Hours and Work–Leisure Conflict: Role of Psychological Detachment and Segmentation Preference. PsyCh Journal 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, S.; Lu, J.; Wang, H.; Montgomery, J. J. W.; Gorny, T.; Ogbonnaya, C. Excessive Technology Use in the Post-Pandemic Context: How Work Connectivity Behavior Increases Procrastination at Work. Information Technology & People 2023. [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Chen, H.; Wang, L.; Bao, J. Tit for Tat? A Study on the Relationship between Work Connectivity Behavior After-Hours and Employees’ Time Banditry Behavior. Frontiers in psychology 2024, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, X.; Zhu, W.; Zhao, H.; Zhang, C. Erratum: Employee Well-Being in Organizations: Theoretical Model, Scale Development, and Cross-Cultural Validation. Journal of Organizational Behavior 2015, 36, 645–647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gadeyne, N.; Verbruggen, M.; Delanoeije, J.; De Cooman, R. All Wired, All Tired? Work-Related ICT-Use outside Work Hours and Work-To-Home Conflict: The Role of Integration Preference, Integration Norms and Work Demands. Journal of Vocational Behavior 2018, 107, 86–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barber, L. K.; Santuzzi, A. M. Please Respond ASAP: Workplace Telepressure and Employee Recovery. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology 2015, 20, 172–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kossek, E. E.; Lautsch, B. A.; Eaton, S. C. Telecommuting, Control, and Boundary Management: Correlates of Policy Use and Practice, Job Control, and Work–Family Effectiveness. Journal of Vocational Behavior 2006, 68, 347–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, K.; Cao, X.; Guo, L.; Xia, Q. Work Connectivity Behavior After-Hours and Job Satisfaction: Examining the Moderating Effects of Psychological Entitlement and Perceived Organizational Support. Personnel Review 2021, ahead-of-print (ahead-of-print). [CrossRef]

- Xie, J.; Ma, H.; Zhou, Z. E.; Tang, H. Work-Related Use of Information and Communication Technologies after Hours (W_ICTs) and Emotional Exhaustion: A Mediated Moderation Model. Computers in Human Behavior 2018, 79, 94–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, F.; Zhang, Z.; Shi, W. Relationship between Daily Work Connectivity Behavior after Hours and Work–Leisure Conflict: Role of Psychological Detachment and Segmentation Preference. PsyCh Journal 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, S. C. Work/Family Border Theory: A New Theory of Work/Family Balance. Human Relations 2000, 53, 747–770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, H.; Li, D.; Zhou, Y.; Zhang, P. The Spillover Effect of Work Connectivity Behaviors on Employees’ Family: Based on the Perspective of Work-Home Resource Model. Frontiers in Psychology 2023, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Büchler, N.; ter Hoeven, C. L.; van Zoonen, W. Understanding Constant Connectivity to Work: How and for Whom Is Constant Connectivity Related to Employee Well-Being? Information and Organization 2020, 30, 100302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kreiner, G. E. Consequences of Work-Home Segmentation or Integration: A Person-Environment Fit Perspective. Journal of Organizational Behavior 2006, 27, 485–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, Y.; Liu, Y.; Headrick, L. When Work Is Wanted after Hours: Testing Weekly Stress of Information Communication Technology Demands Using Boundary Theory. Journal of Organizational Behavior 2020, 41, 518–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schlachter, S.; McDowall, A.; Cropley, M.; Inceoglu, I. Voluntary Work-Related Technology Use during Non-Work Time: A Narrative Synthesis of Empirical Research and Research Agenda. International Journal of Management Reviews 2017, 20, 825–846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jarvenpaa, S. L.; Lang, K. R. Managing the Paradoxes of Mobile Technology. Information Systems Management 2005, 22, 7–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wajcman, J.; Rose, E. Constant Connectivity: Rethinking Interruptions at Work. Organization Studies 2011, 32, 941–961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazmanian, M.; Orlikowski, W. J.; Yates, J. The Autonomy Paradox: The Implications of Mobile Email Devices for Knowledge Professionals. Organization Science 2013, 24, 1337–1357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bader, V.; Kaiser, S. Autonomy and Control? How Heterogeneous Sociomaterial Assemblages Explain Paradoxical Rationalities in the Digital Workplace. management revu 2017, 28, 338–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huth, K. B. S.; Chung-Yan, G. A. Quantifying the Evidence for the Absence of the Job Demands and Job Control Interaction on Workers’ Well-Being: A Bayesian Meta-Analysis. Journal of Applied Psychology 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Greenhaus, J. H.; Beutell, N. J. Sources of Conflict between Work and Family Roles. The Academy of Management Review 1985, 10, 76–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martineau, É.; Trottier, M. How Does Work Design Influence Work-Life Boundary Enactment and Work-Life Conflict? Community, Work & Family 2022, 1–17. [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Bai, Q.; Yuan, Y.; Li, B.; Liu, P.; Liu, D.; Guo, M.; Zhao, L. Impact of Work Connectivity Behavior After-Hours on Employees’ Unethical Pro-Family Behavior. Current psychology 2023, 43, 11785–11803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, M.; Zhang, T.; Li, Y.; Ren, Z. The Effect of Work Connectivity Behavior After-Hours on Employee Psychological Distress: The Role of Leader Workaholism and Work-To-Family Conflict. Frontiers in Public Health 2022, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baek, S.-U.; Yoon, J.; Jong Uk Won. Association between Constant Connectivity to Work during Leisure Time and Insomnia: Does Work Engagement Matter? Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, W.-S.; Kang, S.-W.; Suk Bong Choi. The Dark Side of Mobile Work during Non-Work Hours: Moderated Mediation Model of Presenteeism through Conservation of Resources Lens. Frontiers in public health 2024, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- George Yui-Lam Wong; Kwok, R.; Zhang, S.; Gabriel Chun-Hei Lai; Li, Y.; Jessica Choi-Fung Cheung. Exploring the Consequence of Information Communication Technology-Enabled Work during Non-Working Hours: A Stress Perspective. Information Technology & People 2023. [CrossRef]

- Sefidgar, Y. S.; Jörke, M.; Suh, J.; Saha, K.; Iqbal, S.; Ramos, G.; Czerwinski, M. Improving Work-Nonwork Balance with Data-Driven Implementation Intention and Mental Contrasting. Proceedings of the ACM on human-computer interaction 2024, 8, 1–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michaelides, G.; Niven, K.; Wood, S.; Ilke Inceoglu. A Dual-Process Model of the Effects of Boundary Segmentation on Work–Nonwork Conflict. Journal of occupational and organizational psychology 2024. [CrossRef]

- Carlson, D. S.; Kacmar, K. Michele.; Williams, L. J. Construction and Initial Validation of a Multidimensional Measure of Work–Family Conflict. Journal of Vocational Behavior 2000, 56, 249–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podsakoff, P. M.; MacKenzie, S. B.; Lee, J.-Y.; Podsakoff, N. P. Common Method Biases in Behavioral Research: A Critical Review of the Literature and Recommended Remedies. Journal of Applied Psychology 2003, 88, 879–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaltiainen, J.; Hakanen, J. J. Why Increase in Telework May Have Affected Employee Well-Being during the COVID-19 Pandemic? The Role of Work and Non-Work Life Domains. Current Psychology 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| variables | M | SD | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | ICC(1)and inter Individual variance percentage |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intra individual level | |||||||||

| 1.PC | 3.19 | 1.48 | 0.72(28%) | ||||||

| 2.RC | 3.67 | 1.66 | 0.57*** | 0.71(29%) | |||||

| 3.JC | 2.89 | 1.21 | -0.15* | -0.23*** | 0.78(21%) | ||||

| 4.WC | 2.57 | 1.02 | 0.22** | 0.32*** | -0.22*** | 0.74(26%) | |||

| 5.WW | 3.44 | 1.56 | -0.35** | -0.29** | 0.28*** | -0.61*** | 0.83(17%) | ||

| 6. PC*PC | 2.26 | 2.37 | 0.36*** | 0.35*** | -0.24*** | 0.14* | 0.15** | ||

| intra individual level | |||||||||

| 1.GE | 1.60 | 0.49 | |||||||

| 2.AG | 29.78 | 6.71 | -0.19 | ||||||

| 3.ED | 2.46 | 0.85 | -0.06 | -0.10 | |||||

| 4.MA | 2.61 | 2.51 | -0.33*** | 0.17** | 0.44*** | ||||

| 5.WT | 6.72 | 7.27 | -0.13* | 0.24*** | 0.35*** | -0.36*** | |||

| 6.IP | 2.83 | 0.64 | -0.12* | -0.11* | 0.07 | -0.25*** | -0.36*** | 0.01 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).