Submitted:

23 July 2024

Posted:

24 July 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Patients and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Tissue Samples

2.2. Mucociliary Transport Velocity (MCTV) Measurement

2.3. Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM)

2.4. Total RNA Extraction and Quantitative RT-PCR Analysis

2.5. Immunohistochemistry and Laser Scanning Confocal Microscopy (LSCM) Imaging

2.6. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Background and Characteristics of Subjects in the Study

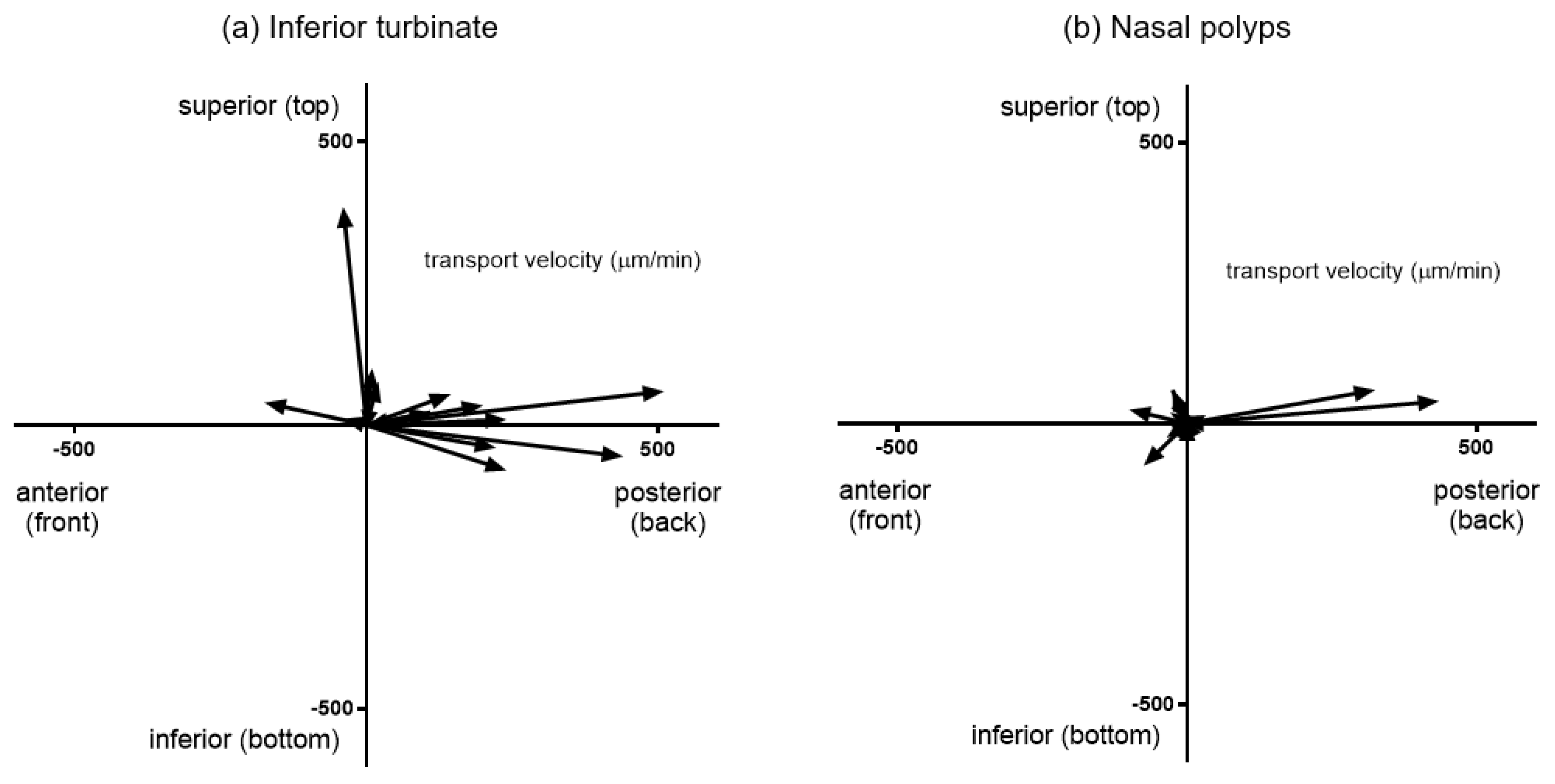

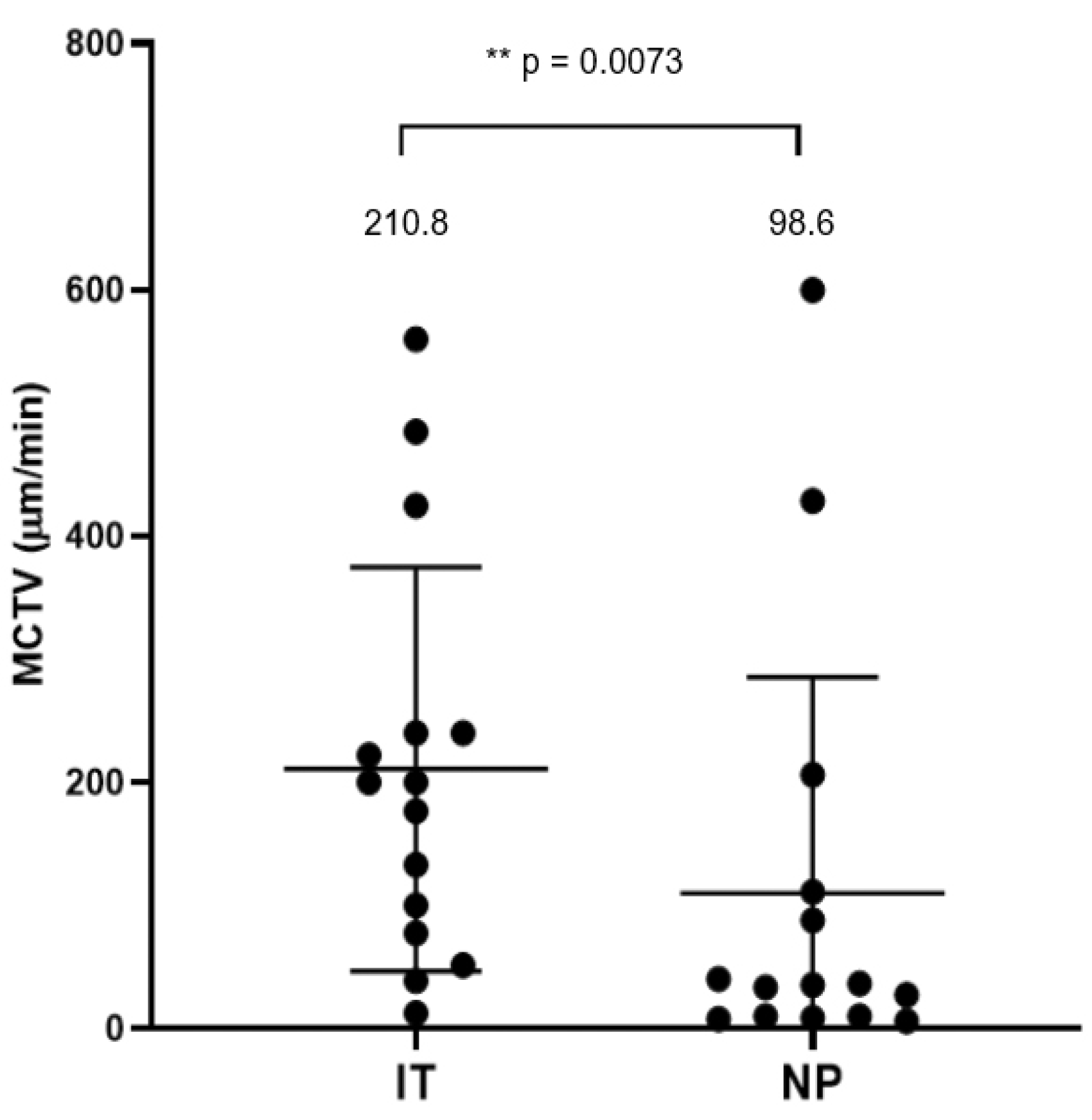

3.2. Mucociliary Transport Velocity Assessment

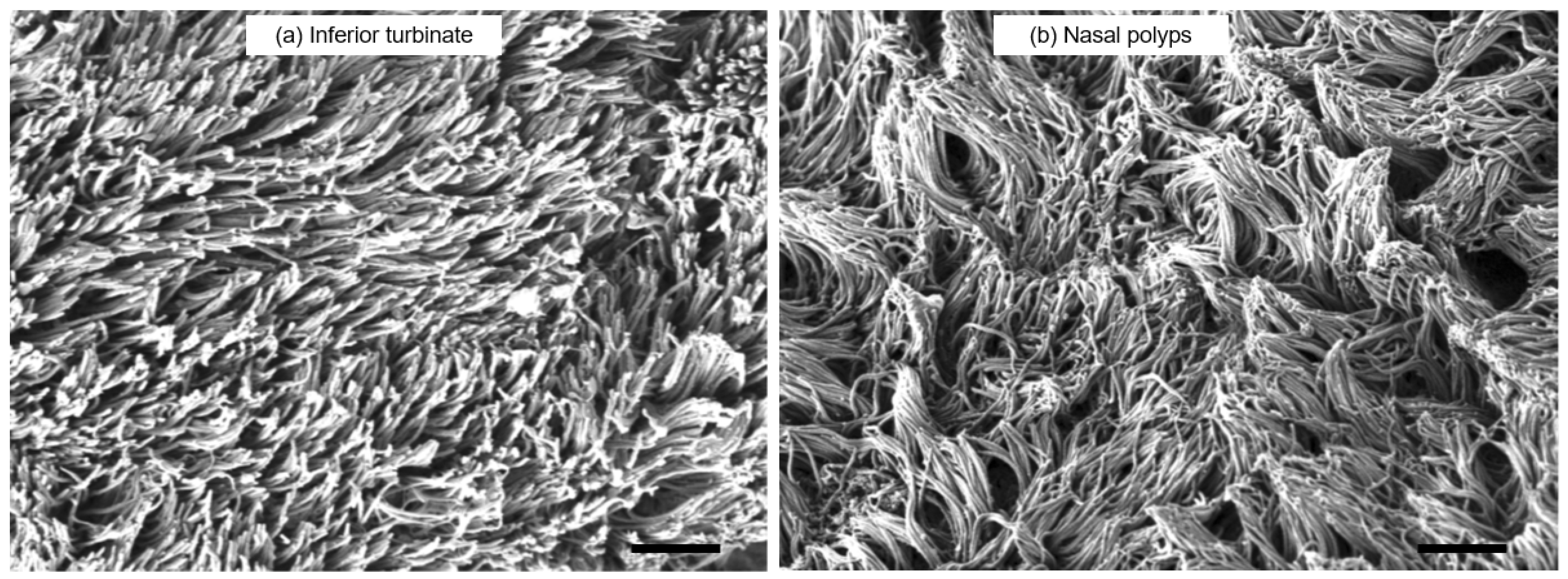

3.3. SEM Observation

3.4. Target Gene Expressions in Sinonasal Mucosa and Nasal Polyps

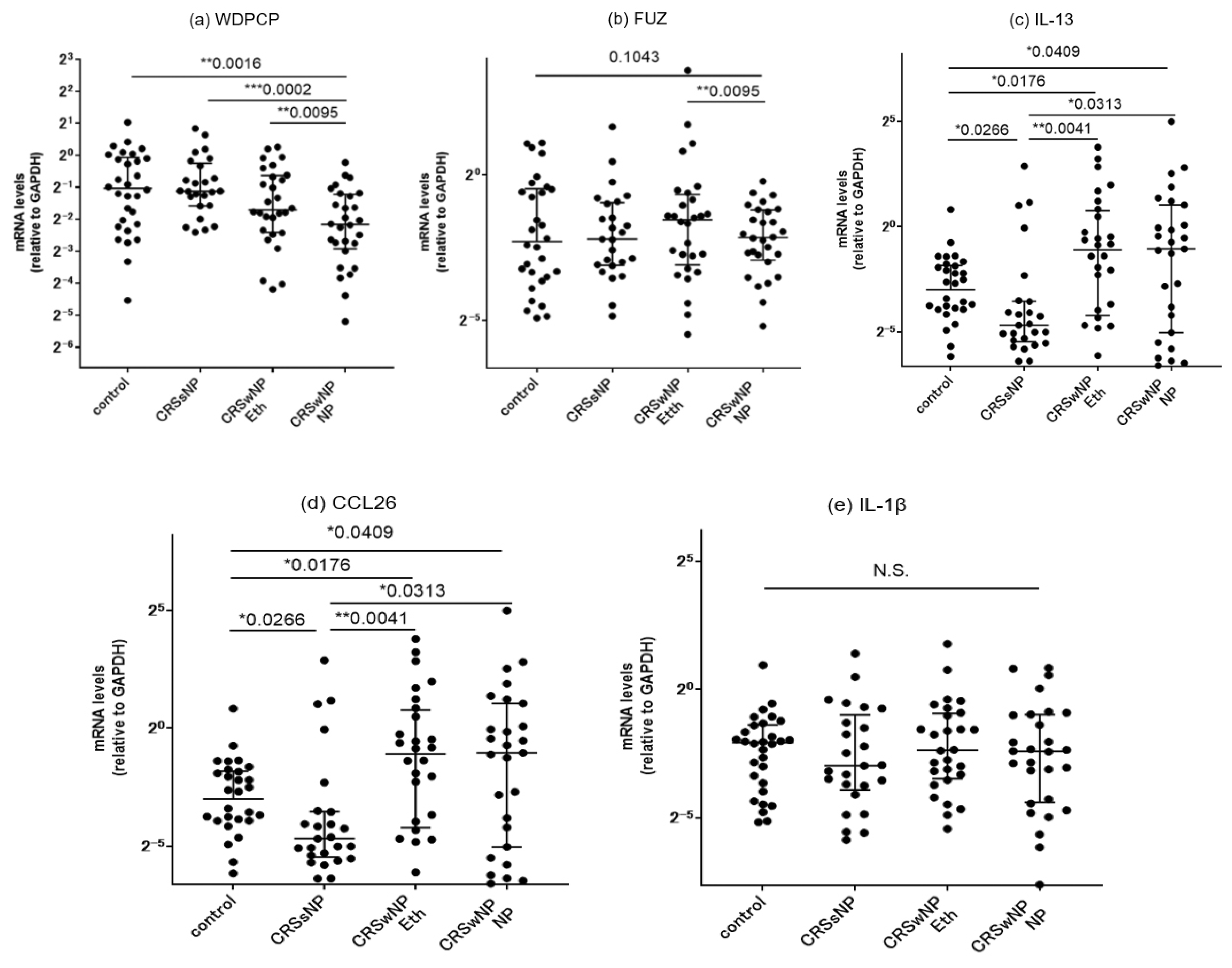

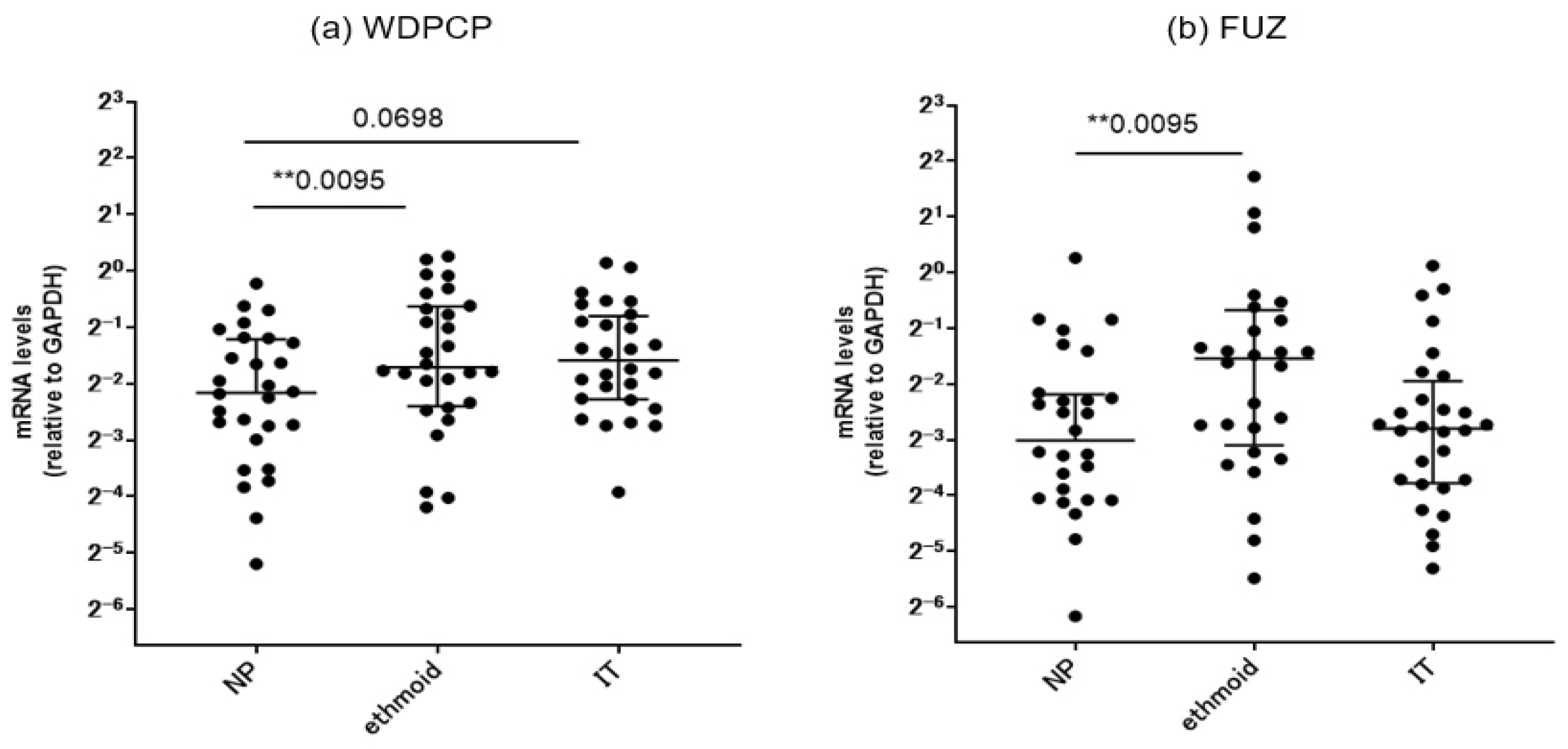

3.4.1. Comparison of mRNA Expressions of PCP Proteins between the Controls and CRS Patients

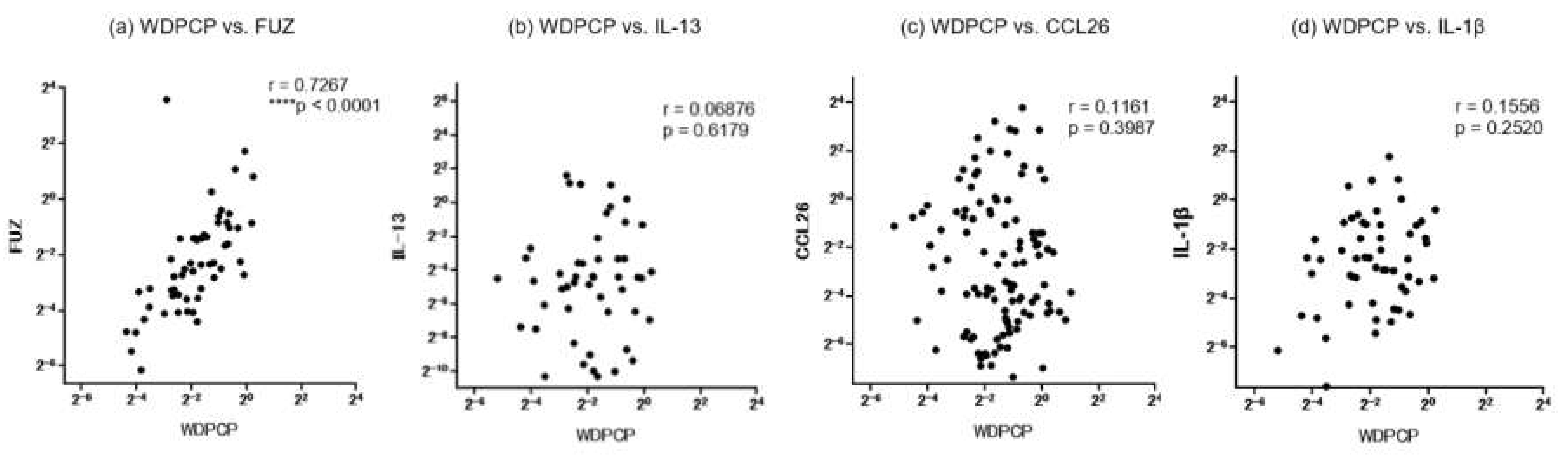

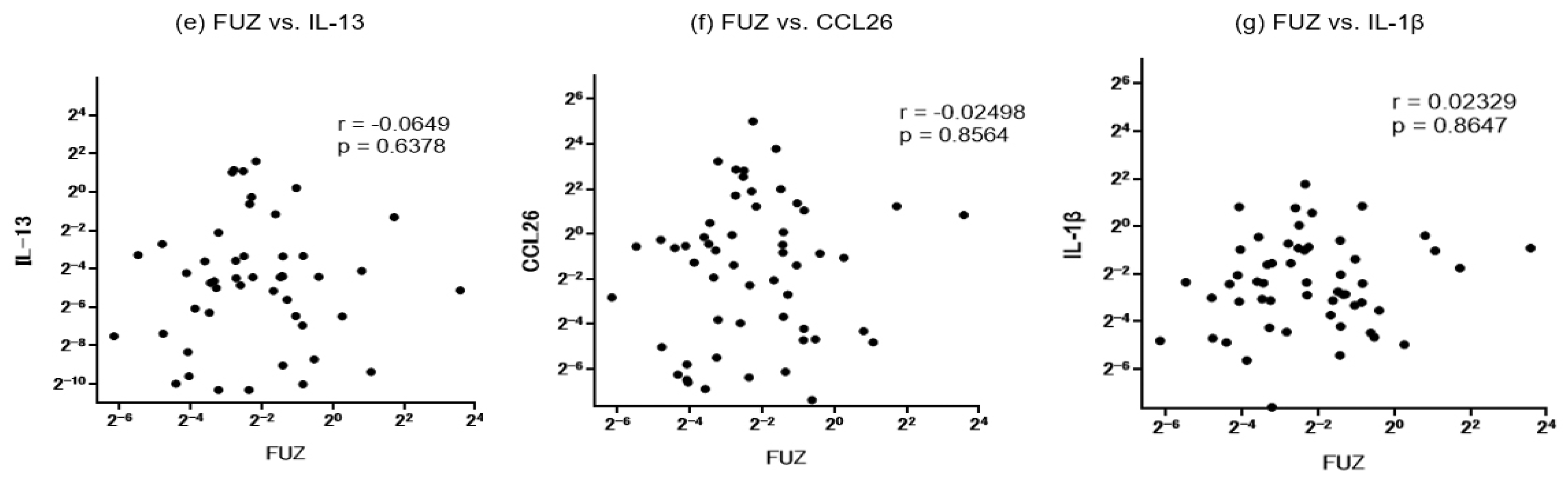

3.4.2. Correlation with Inflammatory Cytokines

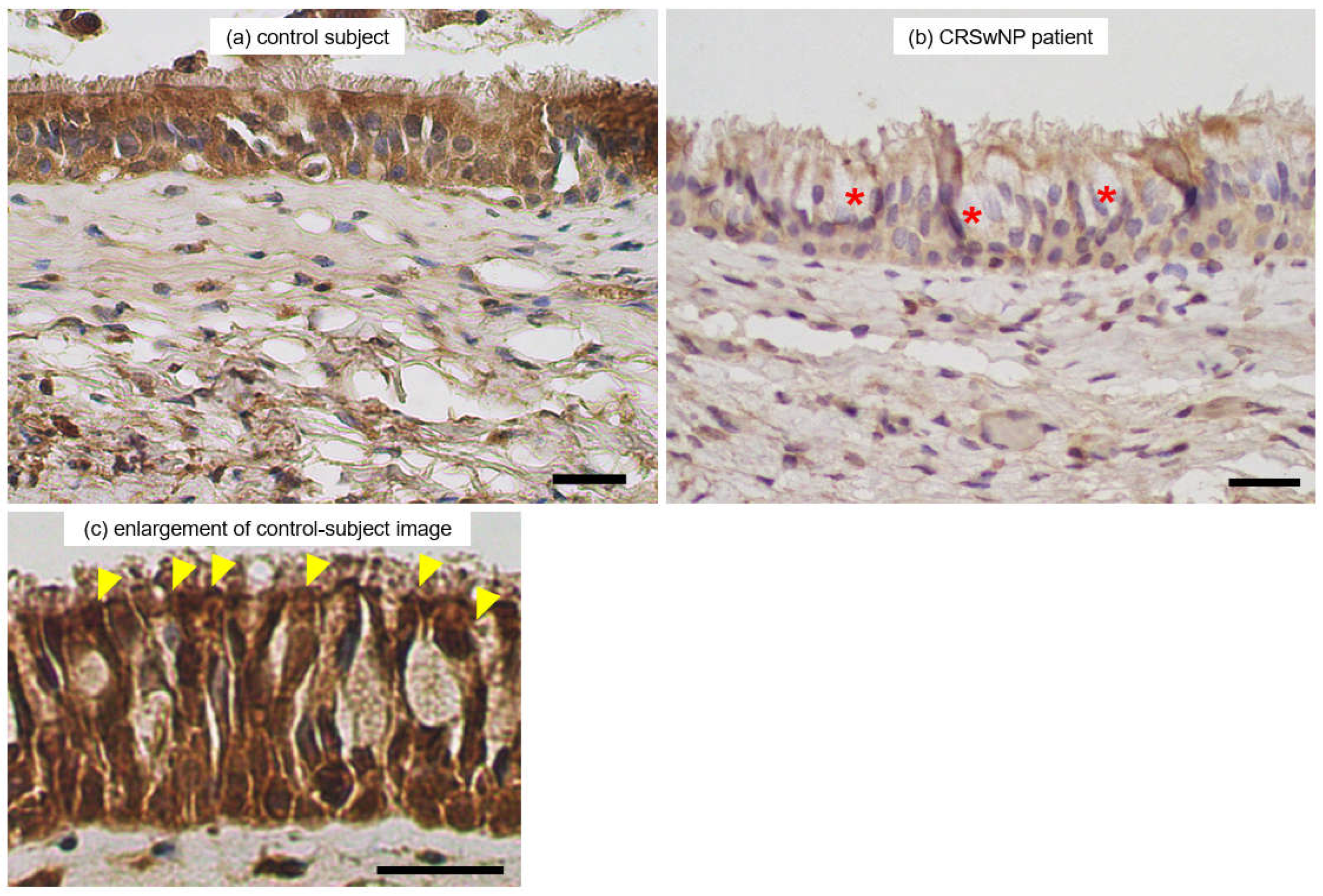

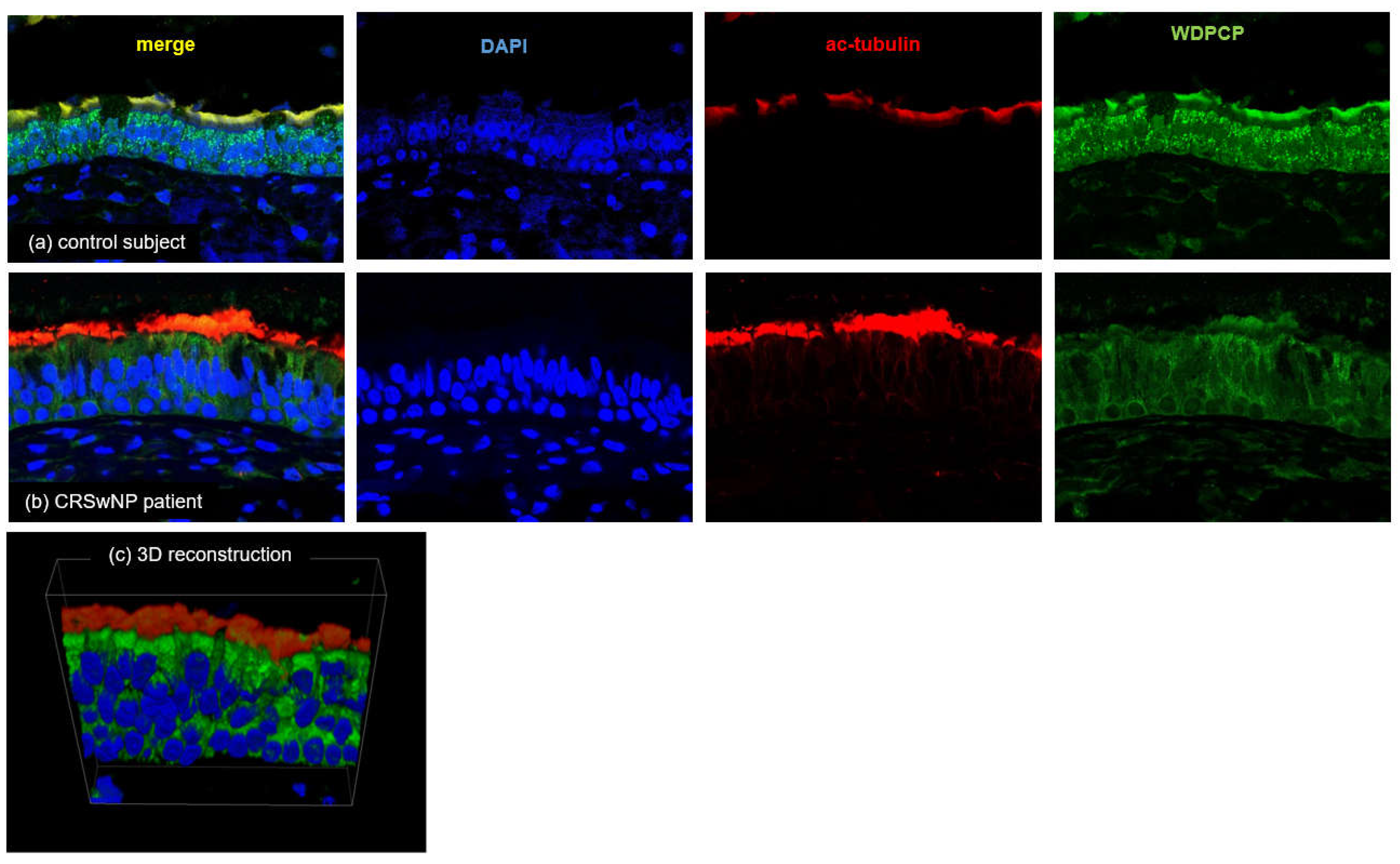

3.5. Immunohistochemistry and Laser Scanning Confocal Microscopy (LSCM) Imaging

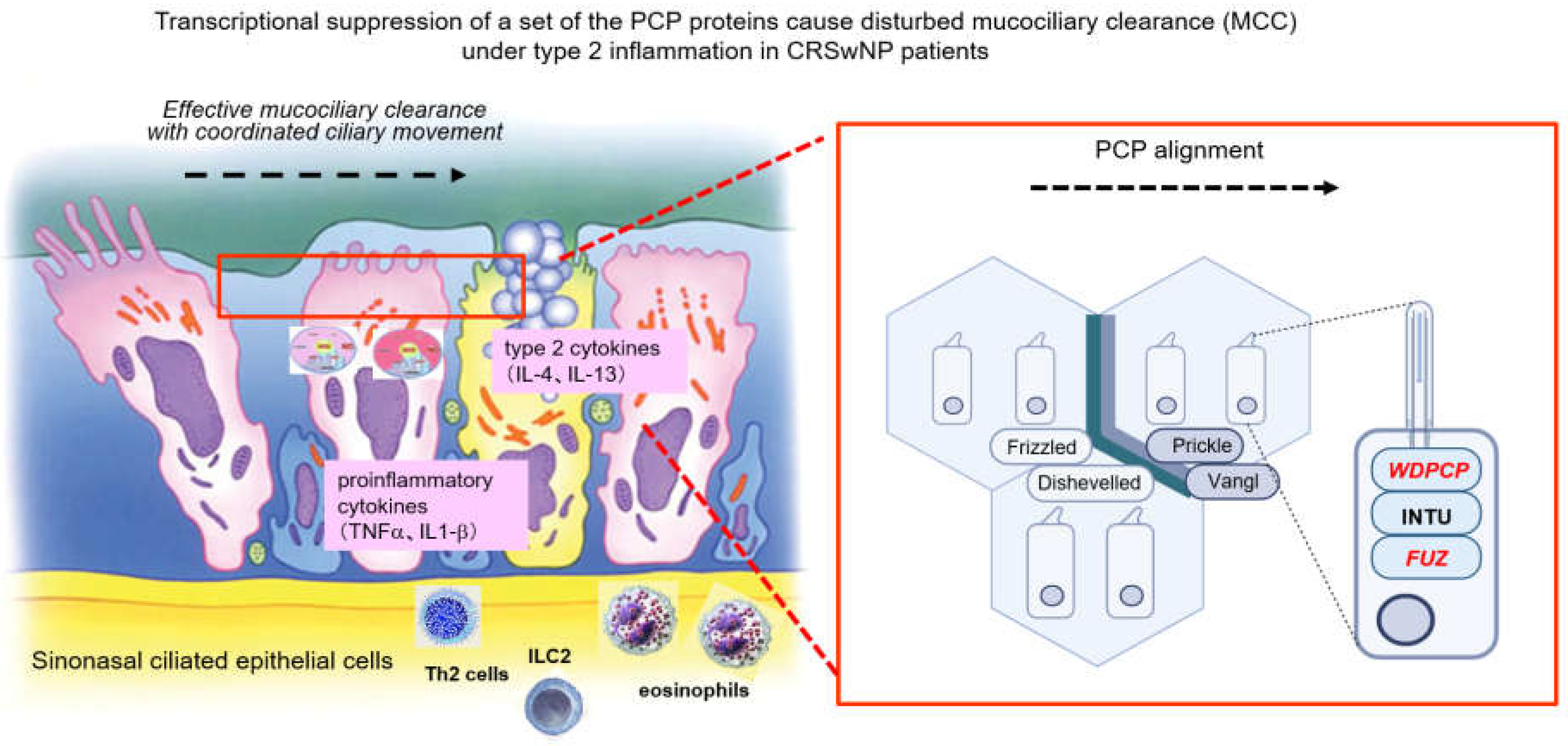

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Cohen, N.A. Sinonasal mucociliary clearance in health and disease. Ann. Otol. Rhinol. Laryngol. Suppl. 2006, 196, 20–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hamilos, D.L. Host-microbial interactions in patients with chronic rhinosinusitis. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2013, 131, 1263-4, 1264.e1-6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Teff, Z.; Priel, Z.; Gheber, L.A. The forces applied by cilia depend linearly on their frequency due to constant geometry of the effective stroke. Biophys. J. 2008, 94, 298–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Majima, Y.; Kurono, Y.; Hirakawa, K.; Suzaki, H.; Haruna, S.; Kawauchi, H.; Ichimura, K.; Moriyama, H. Reliability and validity assessments of a Japanese version of QOL 20-Item Sino-Nasal Outcome Test for chronic rhinosinusitis. Auris Nasus Larynx. 2010, 37, 443–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kato, A.; Schleimer, R.P.; Bleier, B.S. Mechanisms and pathogenesis of chronic rhinosinusitis. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2022, 149, 1491–1503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Metson, R.B.; Gliklich, R.E. Clinical outcomes in patients with chronic sinusitis. Laryngoscope 2000, 110, 24–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dennis, S.K.; Lam, K.; Luong, A. A Review of Classification Schemes for Chronic Rhinosinusitis with Nasal Polyposis Endotypes. Laryngoscope Investig. Otolaryngol. 2016, 1, 130–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cho, S.H.; Bachert, C.; Lockey, R.F. Chronic Rhinosinusitis Phenotypes: An Approach to Better Medical Care for Chronic Rhinosinusitis. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. Pract. 2016, 4, 639–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grayson, J.W.; Hopkins, C.; Mori, E.; Senior, B.; Harvey, R.J. Contemporary Classification of Chronic Rhinosinusitis Beyond Polyps vs No Polyps: A Review. JAMA Otolaryngol. Head Neck Surg. 2020, 146, 831–838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tokunaga, T.; Sakashita, M.; Haruna, T.; Asaka, D.; Takeno, S.; Ikeda, H.; Nakayama, T.; Seki, N.; Ito, S.; Murata, J.; et al. Novel scoring system and algorithm for classifying chronic rhinosinusitis: The JESREC Study. Allergy 2015, 70, 995–1003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fokkens, W.J.; Lund, V.J.; Hopkins, C.; Hellings, P.W.; Kern, R.; Reitsma, S.; Toppila-Salmi, S.; Bernal-Sprekelsen, M.; Mullol, J.; Alobid, I.; et al. European Position Paper on Rhinosinusitis and Nasal Polyps 2020. Rhinology 2020, 58, 1–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Takeno, S.; Hirakawa, K.; Ishino, T. Pathological mechanisms and clinical features of eosinophilic chronic rhinosinusitis in the Japanese population. Allergol. Int. 2010, 59, 247–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fujieda, S.; Imoto, Y.; Kato, Y.; Ninomiya, T.; Tokunaga, T.; Tsutsumiuchi, T.; Yoshida, K.; Kidoguchi, M.; Takabayashi, T. Eosinophilic chronic rhinosinusitis. Allergol. Int. 2019, 68, 403–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khan, A.; Vandeplas, G.; Huynh, T.M.T.; Joish, V.N.; Mannent, L.; Tomassen, P.; Van Zele, T.; Cardell, L.O.; Arebro, J.; Olze, H.; et al. The Global Allergy and Asthma European Network (GALEN rhinosinusitis cohort: A large European cross-sectional study of chronic rhinosinusitis patients with and without nasal polyps. Rhinology 2019, 57, 32–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ishino, T.; Takeno, S.; Takemoto, K.; Yamato, K.; Oda, T.; Nishida, M.; Horibe, Y.; Chikuie, N.; Kono, T.; Taruya, T.; et al. Distinct Gene Set Enrichment Profiles in Eosinophilic and Non-Eosinophilic Chronic Rhinosinusitis with Nasal Polyps by Bulk RNA Barcoding and Sequencing. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 5653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Inoue, N.; Hirota, T.; Hatano, A.; Nakano, M.; Nakashima, D.; Nakayama, T.; Tamari, M.; Yoshikawa, M. Clinical characteristics in Japanese patients with chronic rhinosinusitis who underwent endoscopic sinus surgery. Auris Nasus Larynx. 2024, 51, 286–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Soler, Z.M.; Sauer, D.; Mace, J.; Smith, T.L. Impact of mucosal eosinophilia and nasal polyposis on quality-of-life outcomes after sinus surgery. Otolaryngol. Head Neck Surg. 2010, 142, 64–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abdalla, S.; Alreefy, H.; Hopkins, C. Prevalence of sinonasal outcome test (SNOT-22) symptoms in patients undergoing surgery for chronic rhinosinusitis in the England and Wales National prospective audit. Clin. Otolaryngol. 2012, 37, 276–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, Y.T.; Yeh, T.H. Studies on Clinical Features, Mechanisms, and Management of Olfactory Dysfunction Secondary to Chronic Rhinosinusitis. Front. Allergy 2022, 3, 835151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stevens, W.W.; Schleimer, R.P.; Kern, R.C. Chronic Rhinosinusitis with Nasal Polyps. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. Pract. 2016, 4, 565–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kawasumi, T.; Takeno, S.; Ishikawa, C.; Takahara, D.; Taruya, T.; Takemoto, K.; Hamamoto, T.; Ishino, T.; Ueda, T. The Functional Diversity of Nitric Oxide Synthase Isoforms in Human Nose and Paranasal Sinuses: Contrasting Pathophysiological Aspects in Nasal Allergy and Chronic Rhinosinusitis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 7561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuek, L.E.; McMahon, D.B.; Ma, R.Z.; Miller, Z.A.; Jolivert, J.F.; Adappa, N.D.; Palmer, J.N.; Lee, R.J. Cilia Stimulatory and Antibacterial Activities of T2R Bitter Taste Receptor Agonist Diphenhydramine: Insights into Repurposing Bitter Drugs for Nasal Infections. Pharmaceuticals (Basel) 2022, 15, 452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, W.; Xu, Y.; Wang, L.; Zhu, Z.; Aodeng, S.; Chen, H.; Cai, M.; Huang, Z.; Han, J.; Wang, L.; et al. Single-cell profiling identifies mechanisms of inflammatory heterogeneity in chronic rhinosinusitis. Nat. Immunol. 2022, 23, 1484–1494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ha, J.G.; Cho, H.J. Unraveling the Role of Epithelial Cells in the Development of Chronic Rhinosinusitis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 14229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, Z.Q.; Liu, J.; Sun, L.Y.; Ong, H.H.; Ye, J.; Xu, Y.; Wang, D.Y. Updated epithelial barrier dysfunction in chronic rhinosinusitis: Targeting pathophysiology and treatment response of tight junctions. Allergy 2024, 79, 1146–1165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wanner, A.; Salathé, M.; O’Riordan, T.G. Mucociliary clearance in the airways. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 1996, 154, 1868–1902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, K.Q.; Cowan, A.T.; Lee, R.J.; Goldstein, N.; Droguett, K.; Chen, B.; Zheng, C.; Villalon, M.; Palmer, J.N.; Kreindler, J.L.; et al. Molecular modulation of airway epithelial ciliary response to sneezing. FASEB J. 2012, 26, 3178–3187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, S.K.; Shindo, A.; Park, T.J.; Oh, E.C.; Ghosh, S.; Gray, R.S.; Lewis, R.A.; Johnson, C.A.; Attie-Bittach,T. ; Katsanis, N.; et al. Planar cell polarity acts through septins to control collective cell movement and ciliogenesis. Science 2010, 329, 1337–1340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gray, R.S.; Abitua, P.B.; Wlodarczyk, B.J.; Szabo-Rogers, H.L.; Blanchard, O.; Lee, I.; Weiss, G.S.; Liu, K.J.; Marcotte, E.M.; Wallingford, J.B.; et al. The planar cell polarity effector Fuz is essential for targeted membrane trafficking, ciliogenesis and mouse embryonic development. Nat. Cell Biol. 2009, 11, 1225–1232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cui, C.; Chatterjee, B.; Lozito, T.P.; Zhang, Z.; Francis, R.J.; Yagi, H.; Swanhart, L.M.; Sanker, S.; Francis, D.; Yu, Q.; et al. Wdpcp, a PCP protein required for ciliogenesis, regulates directional cell migration and cell polarity by direct modulation of the actin cytoskeleton. PLoS. Biol. 2013, 11, e1001720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, T.J.; Kim, S.K.; Wallingford, J.B. The planar cell polarity effector protein Wdpcp (Fritz) controls epithelial cell cortex dynamics via septins and actomyosin. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2015, 456, 562–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, Y.; Sun, Y.; Jiang, L.; Zuo, K.; Chen, H.; Guo, J.; Chen, F.; Lai, Y.; Shi, J. WDPCP regulates the ciliogenesis of human sinonasal epithelial cells in chronic rhinosinusitis. Cytoskeleton (Hoboken) 2017, 74, 82–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bottier, M.; Thomas, K.A.; Dutcher, S.K.; Bayly, P.V. How Does Cilium Length Affect Beating? Biophys. J. 2019, 116, 1292–1304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Takemoto, K.; Lomude, LS.; Takeno, S.; Kawasumi, T.; Okamoto, Y.; Hamamoto, T.; Ishino, T.; Ando, Y.; Ishikawa, C.; Ueda, T. Functional Alteration and Differential Expression of the Bitter Taste Receptor T2R38 in Human Paranasal Sinus in Patients with Chronic Rhinosinusitis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 4499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lund, V.J.; Kennedy, D.W. Quantification for staging sinusitis. The Staging and Therapy Group. Ann. Otol. Rhinol. Laryngol. Suppl. 1995, 167, 17–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wake, M.; Takeno, S.; Hawke, M. The uncinate process: A histological and morphological study. Laryngoscope 1994, 104, 364–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sonoyama, T.; Ishino, T.; Takemoto, K.; Yamato, K.; Oda, T.; Nishida, M.; Horibe, Y.; Chikuie, N.; Kono, T.; Taruya, T.; et al. Deep Association between Transglutaminase 1 and Tissue Eosinophil Infiltration Leading to Nasal Polyp Formation and/or Maintenance with Fibrin Polymerization in Chronic Rhinosinusitis with Nasal Polyps. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 12955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ishikawa, C.; Takeno, S.; Okamoto, Y.; Kawasumi, T.; Kakimoto, T.; Takemoto, K.; Nishida, M.; Ishino, T.; Hamamoto, T.; Ueda, T.; et al. Oncostatin M’s Involvement in the Pathogenesis of Chronic Rhinosinusitis: Focus on Type 1 and 2 Inflammation. Biomedicines 2023, 11, 3224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schleimer, R.P. Immunopathogenesis of Chronic Rhinosinusitis and Nasal Polyposis. Annu. Rev. Pathol. 2017, 12, 331–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, X.; Zhang, N.; Bo, M.; Holtappels, G.; Zheng, M.; Lou, H.; Wang, H.; Zhang, L.; Bachert, C. Diversity of TH cytokine profiles in patients with chronic rhinosinusitis: A multicenter study in Europe, Asia, and Oceania. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2016, 138, 1344–1353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lou, H.; Zhang, N.; Bachert, C.; Zhang, L. Highlights of eosinophilic chronic rhinosinusitis with nasal polyps in definition, prognosis, and advancement. Int. Forum Allergy Rhinol. 2018, 8, 1218–1225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stevens, W.W.; Peters, A.T.; Tan, B.K.; Klingler, A.I.; Poposki, J.A.; Hulse, K.E.; Grammer, L.C.; Welch, K.C.; Smith, S.S.; Conley, D.B.; et al. Associations Between Inflammatory Endotypes and Clinical Presentations in Chronic Rhinosinusitis. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. Pract. 2019, 7, 2812–2820.e3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bachert, C.; Hicks, A.; Gane, S.; Peters, A.T.; Gevaert, P.; Nash, S.; Horowitz, J.E.; Sacks, H.; Jacob-Nara, J.A. The interleukin-4/interleukin-13 pathway in type 2 inflammation in chronic rhinosinusitis with nasal polyps. Front. Immunol. 2024, 15, 1356298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ikegami, K.; Sato, S.; Nakamura, K.; Ostrowski, L.E.; Setou, M. Tubulin polyglutamylation is essential for airway ciliary function through the regulation of beating asymmetry. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2010, 107, 10490–10495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, K.; Tai, J.; Lee, S.H.; Kim, T.H. Advances in the Knowledge of the Underlying Airway Remodeling Mechanisms in Chronic Rhinosinusitis Based on the Endotypes: A Review. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Takabayashi, T.; Schleimer, R.P. Formation of nasal polyps: The roles of innate type 2 inflammation and deposition of fibrin. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2020, 145, 740–750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berger, G.; Gass, S.; Ophir, D. The histopathology of the hypertrophic inferior turbinate. Arch. Otolaryngol. Head Neck Surg. 2006, 132, 588–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Do, H.B.; Ohbuchi, T.; Yokoyama, M.; Kitamura, T.; Wakasugi, T.; Ohkubo, J.I.; Suzuki, H. Decreased ciliary beat responsiveness to acetylcholine in the nasal polyp epithelium. Clin Otolaryngol. 2019, 44, 356–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaya, S.; Ercan, M.T.; Laleli, Y. Measurement of nasal mucociliary activity in man with 99mTc-labelled resin particles. Arch. Otorhinolaryngol. 1984, 239, 267–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Passali, D.; Cappello, C.; Passali, G.C.; Cingi, C.; Sarafoleanu, C.; Bellussi, L.M. Nasal Muco-ciliary transport time alteration: Efficacy of 18 B Glycyrrhetinic acid. Multidiscip. Respir. Med. 2017, 12, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paul, B.; Menon, S.S.; Vasthare, R.; Balakrishnan, R.; Acharya, S. Effect of bidi smoking on nasal mucociliary clearance: A comparative study. J. Laryngol. Otol. 2018, 132, 1077–1082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sahin, E.; Hamamcı, M.; Kantekin, Y. Measurement of mucociliary clearance in the patients with multiple sclerosis. Eur. Arch. Otorhinolaryngol. 2020, 277, 469–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zahm, J.M.; Pierrot, D.; Hinnrasky, J.; Fuchey, C.; Chevillard, M.; Gaillard, D.; Puchelle, E. Functional activity of ciliated outgrowths from cultured human nasal and tracheal epithelia. Biorheology 1990, 27, 559–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chevillard, M.; Hinnrasky, J.; Pierrot, D.; Zahm, J.M.; Klossek, J.M.; Puchelle, E. Differentiation of human surface upper airway epithelial cells in primary culture on a floating collagen gel. Epithelial Cell Biol. 1993, 2, 17–25. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Adam, E.C.; Schumacher, D.U.; Schumacher, U. Cilia from a cystic fibrosis patient react to the ciliotoxic Pseudomonas aeruginosa II lectin in a similar manner to normal control cilia--a case report. J. Laryngol. Otol. 1997, 111, 760–762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Slater, A.; Smallman, L.A.; Logan, A.C.; Drake-Lee, A.B. Mucociliary function in patients with nasal polyps. Clin. Otolaryngol. Allied Sci. 1996, 21, 343–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bleier, B.S.; Mulligan, R.M.; Schlosser, R.J. Primary human sinonasal epithelial cell culture model for topical drug delivery in patients with chronic rhinosinusitis with nasal polyposis. J. Pharm. Pharmacol. 2012, 64, 449–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Y.Y.; Li, C.W.; Chao, S.S.; Yu, F.G.; Yu, X.M.; Liu, J.; Yan, Y.; Shen, L.; Gordon, W.; Shi, L.; et al. Impairment of cilia architecture and ciliogenesis in hyperplastic nasal epithelium from nasal polyps. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2014, 134, 1282–1292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vladar, E.K.; Nayak, J.V.; Milla, C.E.; Axelrod, J.D. Airway epithelial homeostasis and planar cell polarity signaling depend on multiciliated cell differentiation. JCI Insight 2016, 1, e88027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Busuttil, A.; More, I.A.; McSeveney, D. A reappraisal of the ultrastructure of the human respiratory nasal mucosa. J. Anat. 1977, 124, 445–458. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Pazour, G.J.; Agrin, N.; Leszyk, J.; Witman, G.B. Proteomic analysis of a eukaryotic cilium. J. Cell Biol. 2005, 170, 103–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Toriyama, M.; Lee, C.; Taylor, S.P.; Duran, I.; Cohn, D.H.; Bruel, A.L.; Tabler, J.M.; Drew, K.; Kelly, M.R.; Kim, S.; et al. The ciliopathy-associated CPLANE proteins direct basal body recruitment of intraflagellar transport machinery. Nat. Genet. 2016, 48, 648–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, T.J.; Haigo, S.L.; Wallingford, J.B. Ciliogenesis defects in embryos lacking inturned or fuzzy function are associated with failure of planar cell polarity and Hedgehog signaling. Nat. Genet. 2006, 38, 303–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, S.K.; Shindo, A.; Park, T.J.; Oh, E.C.; Ghosh, S.; Gray, R.S.; Lewis, R.A.; Johnson, C.A.; Attie-Bittach, T.; Katsanis, N.; et al. Planar cell polarity acts through septins to control collective cell movement and ciliogenesis. Science 2010, 329, 1337–1340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vladar, E.K.; Königshoff, M. Noncanonical Wnt planar cell polarity signaling in lung development and disease. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 2020, 48, 231–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Strutt, D.I. Asymmetric localization of frizzled and the establishment of cell polarity in the Drosophila wing. Mol. Cell. 2001, 7, 367–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Axelrod, J.D. Unipolar membrane association of Dishevelled mediates Frizzled planar cell polarity signaling. Genes. Dev. 2001, 15, 1182–1187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vladar, E.K.; Bayly, R.D.; Sangoram, A.M.; Scott, M.P.; Axelrod, J.D. Microtubules enable the planar cell polarity of airway cilia. Curr. Biol. 2012, 22, 2203–2212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dreyer, C.A.; VanderVorst, K.; Carraway, K.L. 3rd. Vangl as a Master Scaffold for Wnt/Planar Cell Polarity Signaling in Development and Disease. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2022, 10, 887100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, Y.; Tian, P.; Zhong, H.; Wu, F.; Zhang, Q.; Liu, X.; Dang, H.; Chen, Q.; Zou, H.; Zheng, Y. WDPCP Modulates Cilia Beating Through the MAPK/ERK Pathway in Chronic Rhinosinusitis With Nasal Polyps. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2021, 8, 630340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nguyen, T.N.; Koga, Y.; Wakasugi, T.; Kitamura, T.; Suzuki, H. Nasal polyps show decreased mucociliary transport despite vigorous ciliary beating. Braz. J. Otorhinolaryngol. 2024, 90, 101377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| controls | CRSsNP | CRSwNP | |

|---|---|---|---|

| n (male/female) | 30 (17/13) | 25 (13/12) | 28 (15/13) |

| Age, mean±SD | 44.0 ± 17.7 | 60.4 ± 15.0††† | 54.9 ± 10.2†† |

| BMI, kg/mm2, mean±SD | 22.9±4.0 | 22.4 ± 2.8 | 22.6 ± 2.8 |

| Allergic rhinitis, % | 19 (63.3%) | 12 (48%) | 19 (67.8%) |

| Bronchial asthma, % | 2 (6.7%) | 0 (0%) | 9 (32.14%)**,† |

| CT score, mean±SD | NA | 3.75 ± 3.5 | 12.75 ± 4.98**** |

| Blood eosinophils, %; median, range | 4.4 (0.3–4.4) | 1.9 (0.3–14.4) | 5.55 (0.3–13.9)*** |

| Tissue eosinophils, cells/HPF; median, range | 4.8 (0.0–103.3) | 2.6 (0.0–45) | 74.2 (0.0–333.3)*** |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).