1. Introduction

The management of waste, both solid and liquid, from hospitals and residential facilities during pandemics poses a significant level of risk to human life and environmental health. Cities in developing countries generate massive amounts of solid and liquid waste in an environment where there is poor waste management, ranging from non-existing collection systems to ineffective disposal, causing air, water, and soil contamination. Since the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic there has been particular attention to handwashing globally as the first line of protecting oneself against viral disease. According to the World Health Organization (WHO), the provision of safe water, sanitation and hygiene (WASH) and waste management practices is essential in preventing transmission of COVID-19 in homes, communities, healthcare facilities, schools and other public spaces. Furthermore, governments across the globe have imposed varying degrees of curfew and lockdown as drastic measures to contain the spread of the disease. These measures have had both social and economic implications on service providers in the healthcare sector, the sanitation service sector as well as the citizenry.

The first case of COVID-19 was recorded in March 2020 in Ghana (Kosi & Saba, 2020). Shortly after confirming this case, the government’s initial response was to pass the Imposition of Restriction Act 2020 which gave the President of the republic the emergency powers to take actions such as closing of schools, banning public gatherings, closing borders as well as imposing lockdowns on areas considered as hotspots for the spread of the virus. In April 2020, the President of the republic announced policies deemed fit to contain the economic hardships because of the lockdown following from the pandemic. These policies/strategies included supplying Ghanaians with water for up to about six months free of charge starting from April 2020 and highly subsidized electricity. It is widely believed that provision of continuous WASH services is the best way to defend against COVID-19 and prevent future pandemics. Sanitation service providers and workers are very important for operational support in the COVID-19 era and any potential future pandemic. Workers along the sanitation service chain are encouraged to follow standard operating procedures including the wearing of appropriate personal protective equipment (PPEs) such as safety boots, protective outerwear, heavy-duty gloves, medical masks, goggles and/or face shield; reducing spillage during pulling and/or dislodging; washing dedicated tools and clothing; performing hand hygiene regularly; obtaining vaccination for sanitation-related diseases as well as monitoring oneself frequently for symptoms of COVID-19 or other infectious diseases (Alemi et al., 2022). There is also the need to protect staff of sanitation companies as well as informal faecal sludge emptiers by prioritizing systematic supply of PPE while raising their awareness of the importance of adhering to all Covid-19 protocols when at duty post.

However, little or no attention has been paid during the pandemic to sanitation service providers as the focus in COVID-19 responses across the world has been on healthcare systems, developing vaccines and treatments, and the safety of healthcare workers. However, equally important are the availability of clean water and access to safe sanitation services. There is therefore a threat of neglecting the operational and economic aspects of the pandemic on the sanitation service providers especially those dealing with fecal sludge management. This study examines the operational and economic effect of the COVID-19 pandemic on sanitation service providers in Ghana. Specifically, the study attempts to identify the coping mechanisms and measures put in place by sanitation service providers to ensure continuous service delivery. The study also identifies a circular economy approach to build resilience of the multiple sectors and actors to COVID-19 pandemic-shocks, along the water and sanitation service chains. It identifies promising circular economy solutions for water and fecal sludge reuse which can simultaneously yield benefits for water, waste, and food systems.

2. Literature

2.1. An Overview of the Sanitation Value Chain

Sanitation value chain has gained prominence as a common terminology since the year 2008 to describe the components of sustainable urban sanitation (Tilley et al., 2014). These components are described as the user interface. They could be either private facilities, compound shared facility or public facilities, storage systems such as septic tanks, conveyance or transportation services provided by septic tank emptier, treatment, use and/or safe disposal of waste. In the context of sanitation services, on-site sanitation systems (OSSs), such as septic tanks and pit latrines are the predominant sanitation systems in rural and urban areas in most developing countries including Ghana.

Figure 1 depicts the sanitation service chain for OSSs which comprises of access to toilets, emptying, transport, treatment and disposal or reuse. The chain is used as a framework for analyzing the physical flow of FS through the system (Blackett et al., 2014; Hawkins et al., 2014).

The development of an efficient sanitation chain depends on technological, organizational, social, and institutional innovations which are interconnected to demonstrate the value dimensions (van Welie et al., 2019). According to (Tilley et al., 2014), on-site sanitation is characterized by waste management systems in which excreta together with wastewater are collected and stored on the plot where they are generated. However, the treatment of the same takes place either on the plot or conveyed to a different location for treatment. This is also known as an off-site sanitation system where excreta and wastewater are conveyed to other places for treatment. The most common system practiced in Ghana is where the excreta is conveyed for either treatment and reuse or disposal elsewhere. This to a very large extent makes the transportation service provider an integral actor along the sanitation value chain requiring a deeper understanding of their operations in terms of quality and safety before the outbreak of Covid-19 pandemic, during the peaks of COVID-19 and post COVID-19 era. What are the regulatory frameworks governing these operators’ business? What effects did COVID-19 have on emptying service provision? What has changed in terms of their operations? In line with the Sustainable Development Goals aimed at safely managed sanitation for all by the year 2030 (Andersson et al., 2018; van Welie et al., 2019), safely managed on-site sanitation in recent times have received some considerable attention in research as a way of improving sanitation services especially in cities and peri-urban areas in developing countries. The quest to improve sanitation services in these areas come with associated challenges since on-site sanitation service providers are confronted with lack of regulations, institutional constraints, socio-cultural resistance as well as inadequate government support which is needed to create a supportive enabling environment (Lüthi et al., 2011). Furthermore, the financial viability of on-site sanitation services is a source of challenge for entrepreneurs and usually not affordable for poor city households. For instance, Mbéguéré et al. (2010) and Parkinson and Quader (2008) have provided evidence of challenges in cost recovery for emptying services. (van Welie et al., 2019) gives an account of how on-site sanitation innovations in Nairobi, Kenya have evolved in the past few decades. One of such innovative projects targeted improving the conveyance of sanitation waste through the professionalization of manual pit emptiers where they received management training and were also equipped with personal protective clothes as well as specialized mechanical pumps to empty pit latrines. However, the project could not be sustained and that was attributed to encroachment of slum dwellers around the designated disposal points. Eventually, pit emptiers went back to what van Wilie et al. (2019) describe as ‘illegal’ business of dumping the waste into nearby rivers and open spaces.

2.2. Emptying and Transport Services during COVID-19

Unlike the user interface and storage component along the sanitation chain, the conveyance/waste transportation segment has not seen a lot of innovation. Very few innovations have focused on improving efficiency to lower the cost of collection for low-income households to be able to afford the services. These have been done along the lines of individual initiatives. According to van Wilie et al. (2019), relatively few research and experimentation have been conducted to develop the waste transportation segment. The most common means of transporting waste from generation point to disposal or treatment facilities are by wheelbarrows, handcarts, and trucks. More research in the conveyance segment of the sanitation chain is required because waste collection in most city settlements could be challenging and without proper collection and transportation, on-site sanitation systems are likely to produce significant negative side effects. Studies have shown that waste is collected and transported on a relatively small scale by private/individual sanitation service providers (Sagoe et al., 2019). In as much as the segment is confronted with socio-cultural challenges such as stigma surrounding human waste collection, sensitivity, and issues of dignity, safety, clean and reliability, studies have shown that market exist for human waste collection and transportation services in the cities of most African countries including Ghana (van Wilie et al., 2019). Waste transportation services are predominantly provided by manual pit latrine emptiers and exhaust truck operators. However, this market is believed not to be adequately regulated and controlled meanwhile such human waste is dumped on a regular basis. Sagoe et al. (2019) conducted a GIS analysis of fecal sludge management in the Greater Accra Metropolitan Area, Ghana and this provides data useful for rationalizing the fecal sludge emptying and transportation cost in their study area. Their study further shows that about 20 to 30 percent of the localities within the study area were outside the 15 to 25 km sustainable maximum transport distance as recommended by various studies. In countries such as Ireland and Uganda, GIS analysis has been deployed to aid infrastructural gaps and fecal sludge transport services to the betterment of emptying service providers (Sagoe et al., 2019).

The knowledge of distances from collection points to treatment plants is important for calculating haulage cost per cubic meter of fecal sludge collected for transportation. The two main parameters relevant for such calculations are travel distance and travel time which are easily obtained by GIS to aid in optimizing fecal sludge management in Ghana in terms of reasonable service charges by vacuum truck operators (Sagoe et al., 2019). Fair charges in the collection and transport services in the waste management chain are very key to the achievement of SDG 6 (i.e., clean water and sanitation). Furthermore, beyond the cost rationalization proper siting of fecal treatment plants is important to reduce fuel consumption and consequently decrease greenhouse gas emissions to contribute to the global sustainability agenda (Sagoe et al., 2019). Faecal sludge could be either treated in specialized plants on-site or off-site. Local government authorities may consider siting faecal sludge transfer stations near health facilities to reduce the time and monetary cost as well as the potential for uncontrolled dislodging into open drains and agricultural lands. Sanitary workers who encounter untreated sewage should always wear standard PPEs when handling or transporting sludge off-site while taking measures to avoid splashing and spraying droplets. It is highly recommended that after handling the waste and there is no risk of further exposure, sanitation workers/transporters and their assistants should safely remove PPEs and make sure hand hygiene is performed before they finally enter trucks to recess. Furthermore, soiled PPEs should be put in sealed for safe handling and laundering after work. It is also recommended that transporters are properly trained in how to wear and remove PPEs before and after use respectively. As a measure to contain the spread of viruses during pandemics untreated sludge and wastewater from both residential and health facilities especially must not be dumped onto agricultural land (WHO, 2020).

Literature suggests there are about 148 vacuum trucks providing emptying and haulage services in the Greater Accra Metropolitan Area and surrounding communities (Sagoe et al., 2019). This represents about 19 percent increment in what existed in the same area in the year 2017

1. These trucks are registered under two service operator associations and most of these trucks discharge at the Lavender Hill FTP (Sagoe et al., 2019). Majority of the trucks are privately owned with the remaining owned by the state and parastatal institutions such as SSNIT, Ghana police service, Ghana army, prisons service etc. The limited participation of state institutions such as waste management departments of district assemblies in the collection and transport of fecal sludge is linked to inadequate allocation of resources for sanitation management by the government (Sagoe et al., 2019)

2. The focus of this current study is to investigate for better understanding of relevant stakeholders the issues of quality services, safety of emptying practices to both operators and customers as well as the health implications of the fecal collection and transportation service provision amidst COVID-19 pandemic.

In the past, Accra has had about three major fecal sludge treatment plants in Achimota, Teshie-Nungua and Korle Gonno/Old Lavender Hill with varying capacities to serve the needs of Accra and its environs, yet the high cost of fecal sludge collection and haulage poses a significant challenge to fecal sludge management. Specifically, the closure of the Achimota WSP which served the localities in Accra north is one of the possible causes of the rise in waste haulage cost because truck drivers are only left with the option of transporting over long distances (Sagoe et al., 2019). The treatment component of the sanitation chain in recent years has seen many innovations because of increased research activities by international research institutes and universities. This research has focused on recovering reusable resources from waste products such as soil nutrients from human excreta. The development in the treatment segment has been necessitated by anaerobic digestion and co-composting technologies usually with funding from international donors. On the other hand, several reused products have been developed based on technological innovation systems such as fertilizers, animal feed and biogas in the use or safe disposal segment of the sanitation chain.

At the policy level, waste as a business paradigm contributes to the legitimacy of reusing human waste. For instance, in the year 2009 the Implementation Plan for Sanitation of the Ministry of Water and Irrigation permits that facilities receiving high volumes of effluent such as on-site sanitation facilities in public places and organizations should be designed in a way that considers reuse of effluent to produce biogas, fertilizers and water for irrigation in the cities of Kenya (van Wilie et al., 2019). This idea is to ensure the protection of the environment whiles generating the advantages of sanitation for production. Overall, the legitimation for on-site sanitation has progressed in recent years especially at the policy level because many African governments and state institutions have seen that as an appropriate option for managing human waste. However, the cultural-related issues when it comes to handling of human waste continues to inhibit the creation of legitimacy in the individual components of the sanitation chain as described especially the conveyance or waste transportation service segment. The conveyance segment is further hindered by widespread notion that sewerage systems are superior form of sanitation management (van Wilie et al., 2019).

2.3. Determinants of FS Collection and Sustainable Transportation Service

The type of sanitation system used in an area, population density and income levels have been found in literature to be significant determinants of the level of service provided by vacuum truck operators (Schoebitz et al., 2017; Sagoe et al., 2019). Specifically, the number of people inhabiting a geographic area determines the quantum of fecal generated over a certain period with a corresponding collection and transportation service required. Sagoe et al. (2019) found out that densely populated areas in Accra Metropolis have lower income levels and the reverse is true. Furthermore, upper echelon neighbourhoods recorded higher discharge frequencies which is an indication of higher service delivery. And that in densely populated areas such as slums truck services were not just limited by their characteristic low-income levels but also inaccessibility to containment systems by trucks which warrants the manual emptying. Emptying and transportation services along the sanitation management chain may be said to be sustainable if it has both economic and social benefit with minimal or no negative impact on the environment. The key indicators of sustainable waste transportation service include reduced air pollution, greenhouse gas emissions as well as transportation cost to customers (Sagoe et al., 2019). This implies that longer haulage distances contribute to increased air pollution, greenhouse gas emissions and transport cost and by extension hindering the achievement of the sustainable development goals 3, 6, 12 and 13 (i.e., good health and well-being, clean water and sanitation, responsible consumption and production, climate action respectively). There is no documented threshold by relevant international bodies pointing to the maximum sustainable haulage distance for fecal transport. However, some studies have suggested sustainable haulage distances based on study area conditions which may vary across locations. For instance, Gill et al. (2018) suggested 25 km for Ireland; whiles others have also recommended maximum sustainable transport distance of between 15 km to 20 km for developing countries.

2.4. Regulations on Cost of FS Collection and Transportation

The National Environmental Sanitation Policy (2010) revised in 2011 is the main policy document on environmental sanitation in Ghana. It stipulates that private entities can undertake provision and management of septage tankers on full commercial basis subject to fulfilling licensing requirements and the setting of maximum tariffs by the responsible assemblies (Boamah, 2011; Sagoe et al., 2019). It is however on record that even though tariffs have been set for the hiring of trucks owned by MMDAs, revised annually in the imposition of rates and fee-fixing resolution documents of the assemblies there are still no tariff regime for private operators. As mentioned earlier, the cost of waste transport is mainly determined by the travel distance, the truck capacity, the nature of roads to the fecal sludge source and the travel time (which is also determined by the level of traffic congestion of the route). The cost of emptying a cesspit by vacuum truck operators in the Greater Accra Metropolis ranges between GHS 150 to GHS 600 (i.e., USD 20 – UDS 125) per trip (Sagoe et al., 2019). This cost is considered high in literature compared to what pertains in the cities of other African countries like Dakar, Senegal (USD 50); Adis Ababa, Ethopia (USD 9.3 – USD 36); Kisumu, Kenya (USD 25) and in India (USD 25 – USD 30) per trip even though the discharge fee paid by operators fall within the same range (USD 2.0 – USD 6.2) per trip. Sagoe et al. (2019) attributes the relatively high cost charged by Ghanaian vacuum truck operators partially to the nonexistence of a well-structured haulage cost regime. This results in operators charging collection and transport fees to customers arbitrarily. Nevertheless, leaders of vacuum truck operators’ associations could regulate the prices charged by their members to the public in the absence of tariffs set by the regulating bodies in charge

3. This is a bit tricky because leaders of such associations are equally owners of trucks, hence the issue of conflict comes to play which makes it difficult for free and fair decisions on such matters to be taken. In the Ghanaian context, service providers predominantly determine service charges even though the association of vacuum tanker operators operate under the Environmental Services Providers Association which is charged with the mandate to regulate the activities of service providers.

2.5. Measures for Sanitation Service Provision during the Pandemic

According to Bessonova (2020), COVID-19 has demonstrated the risks associated with the current dependence on weak global supply chains of water, sanitation, and hygiene (WASH)

4. These risks may be well addressed by installing circular productive sanitation systems – developing a self-reliant base of local resources. The World Health Organization (WHO and UNICEF, 2020) has summarized key information concerning water, sanitation and hygiene and SARS-Cov-2 (i.e., the virus which causes COVID-19) in an interim guidance as follows:

Frequent and correct handwashing is vital for preventing infection with the virus, therefore water, sanitation, and hygiene practitioners as well as providers should endeavor to inform and encourage frequent and regular hand hygiene exercises.

Water disinfection and waste treatment has the potential to reduce the virus and spread. Therefore, sanitation workers should be given the right training and access to PPEs and an appropriate combination of the PPEs is highly recommended.

The application of good hygiene practices and waste management in the era of a pandemic such as COVID-19 can also prevent other infectious diseases.

A study by WHO reports that every US dollar invested in sanitation delivers a nearly six-fold return because of the reduced cost to the general health system, increased spending power among poor households, reduced constraint to other services, increased productivity as well as fewer premature deaths. COVID-19 presents a situation that raises concerns about national governments’ responses. According to Oppong (2020), there are reasons to be certain about the ability of most African countries to deal with COVID-19 such as the aggressive responses by governments, track record of ingenuity and innovation in disease testing and treatment as well as past experiences with HIV/AIDS and Ebola which helped countries in the continent to learn how to swiftly respond to health crisis. There have been many successful responses by African governments to the COVID-19 pandemic. For example, the free water initiative in Ghana even though it is not the only country in the continent to have implemented such a strategy, but it is the most comprehensive (Smiley et al., 2020). Very key to future containment of pandemics such as what the world is experiencing now is for all actors; government, private sector, civil society, development partners and the citizenry to collaborate effectively in responding to such pandemics.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Data Type, Source, and Analysis

The study uses cross-sectional data obtained from 56 vacuum truck operators engaged in collection and transportation of fecal sludge between January – March 2021 using a semi-structured interview questionnaire. For the survey, a computer assisted personal interview (CAPI) tool was used which is a free mobile data collection and managing tool suitable for the current situation to take precaution in the face of the pandemic as it avoids use of paper-based interviews. The vacuum truck operators operate in the Accra, Tema and Ashaiman metropolitan and municipal assemblies. Currently, there are about 148 vacuum trucks providing emptying and haulage services in the Greater Accra Metropolitan Area and surrounding communities. However, the respondents for this study were purposively selected based on their availability and willingness to grant an interview. The snowball procedure was employed to reach as many as possible respondents. During the interview, vacuum truck operators were asked about their business operations pre COVID-19 and post COVID-19 (during the pandemic). The sanitation service providers were asked to identify the major operational and economic impact of the pandemic on their business as well as the coping mechanisms and measures put in place to ensure continuous service delivery. Descriptive statistics of key variables relevant to the study are presented in the form of tables, and graphs. Furthermore, thematic analysis of relevant data supported with some narrative review serves as the starting point for analyzing the data obtained for this study. Narrative reviews rather than systematic reviews are relied on to argue some of the issues. Whiles systematic reviews are most appropriate for narrow and well-defined questions and often considered quantitative, narrative reviews are more useful for providing rationales for future research and speculation of new types of interventions by presenting broad perspectives and synthesizing a lot of information into a readable format.

4. Results and Discussions

4.1. Sanitation Service Providers’ Specific Characteristics

Table 1 presents characteristics of surveyed vacuum truck operators. The majority of the surveyed vacuum truck operators are private entities belonging to an association with a business permit from relevant authorities. This shows that majority of the surveyed truck operators are formal businesses. The vacuum trucks are usually operated by a hired driver based on agreed owner-driver terms with only 11% of the drivers also doubling as owners of the trucks owning on average one truck. This indicates that fecal sludge collection and transportation in Ghana is done on a relatively small scale by private sanitation operators. The average age of the truck drivers was 38 years with the youngest being 23 years and the eldest being 59 years. This is an indication that the truck drivers fall within the working age population (i.e., 15 – 64 years) as defined by OECD

5. With regards to educational level, most of the drivers have had at least primary (55%) and secondary education (34%) with varying degree of experience ranging from 1 year to 24 years with an average of 8 years of experience in operating septic trucks.

According to the Accra Metropolitan Assembly (AMA), it is expected that every business operating within its jurisdiction acquires permit which is the license that enables the business entity to do legitimate business

6. Majority of the surveyed respondents (79%) have acquired business permit which follows through several processes such as registration of vehicle with the Driver and Vehicle Licensing Authority (DVLA) and obtaining certificate of incorporation from the Registrar General’s department. In addition to these, having an appropriate business name and contact details as well as the business location were relevant for acquiring the business permit. In monetary terms the average cost of acquiring the business operating permit is GHS 380, paid periodically to local government. More than 95% of surveyed vacuum truck operators reach their clients by posting their business contact numbers on their vehicles as this is considered the cheapest and simplest way of advertising their businesses. These are usually in the form of an embossment on the truck with the company name and their location. This is followed by distribution of their business cards to the client door-to-door (77%) and posting their business contact on clients’ gates or walls in the form of a flyer (43%). In addition to these, other means of reaching clients included recommendation by other clients, clients walking up to the stations where the truck drivers are located, social media handles. Majority of them do not have a database of their clients with only 25% of drivers indicating that they have a database of the clients they serve which comes in many different forms such as keeping records of transaction (e.g., receipts); stored contact numbers in cell phones; and record books solely dedicated for customer contacts. However, majority of the truck drivers (98%) do have regular clients they serve. More than half of the surveyed truck operators indicated that the fee is based on factors such as change in fuel prices, cost of maintenance and spare-parts, distance to the source of fecal sludge and the designated dumping sites. In addition, leaders of the vacuum truck operators association set and regulate fees charged by their members to the public.

Majority of the surveyed vacuum truck operators belong to service providers’ associations. The vacuum truck operator associations are located around the areas where they provide services and they include the Achimota Waste Tankers Association (60 members), City Waste Management (45 members) and Korle Gonno Cesspit Workers Association (100 members). Such associations are important in providing regulatory mechanisms for the effective delivery of services by their members (Sagoe et al. 2019). For instance, in the absence of tariffs set by the local government, leaders of the groups of vacuum truck operators set and monitor the prices charged by their members within a certain geographical location. This exemplifies the case of other transport unions in Ghana such as the Ghana Private Road Transport Union (GPRTU), the Progressive Transport Owners Association (PROTOA) among others. It is worth noting that even though the associations of vacuum tanker operators are under the Environmental Services Association (ESPA) which in a way regulates their activities, service charges are determined by individual service providers (Sagoe et al., 2019). Members of the vacuum truck operators’ associations have obligations and benefits. Some of the key obligations include payment of membership dues, providing good service to clients, avoid dumping of fecal sludge at an unauthorized dumping site and wearing of appropriate PPEs. The benefits of membership include support on matters of welfare such as supporting members in financing of funeral, wedding and child naming ceremonies.

4.2. Key Operational Regulations and Clients Served

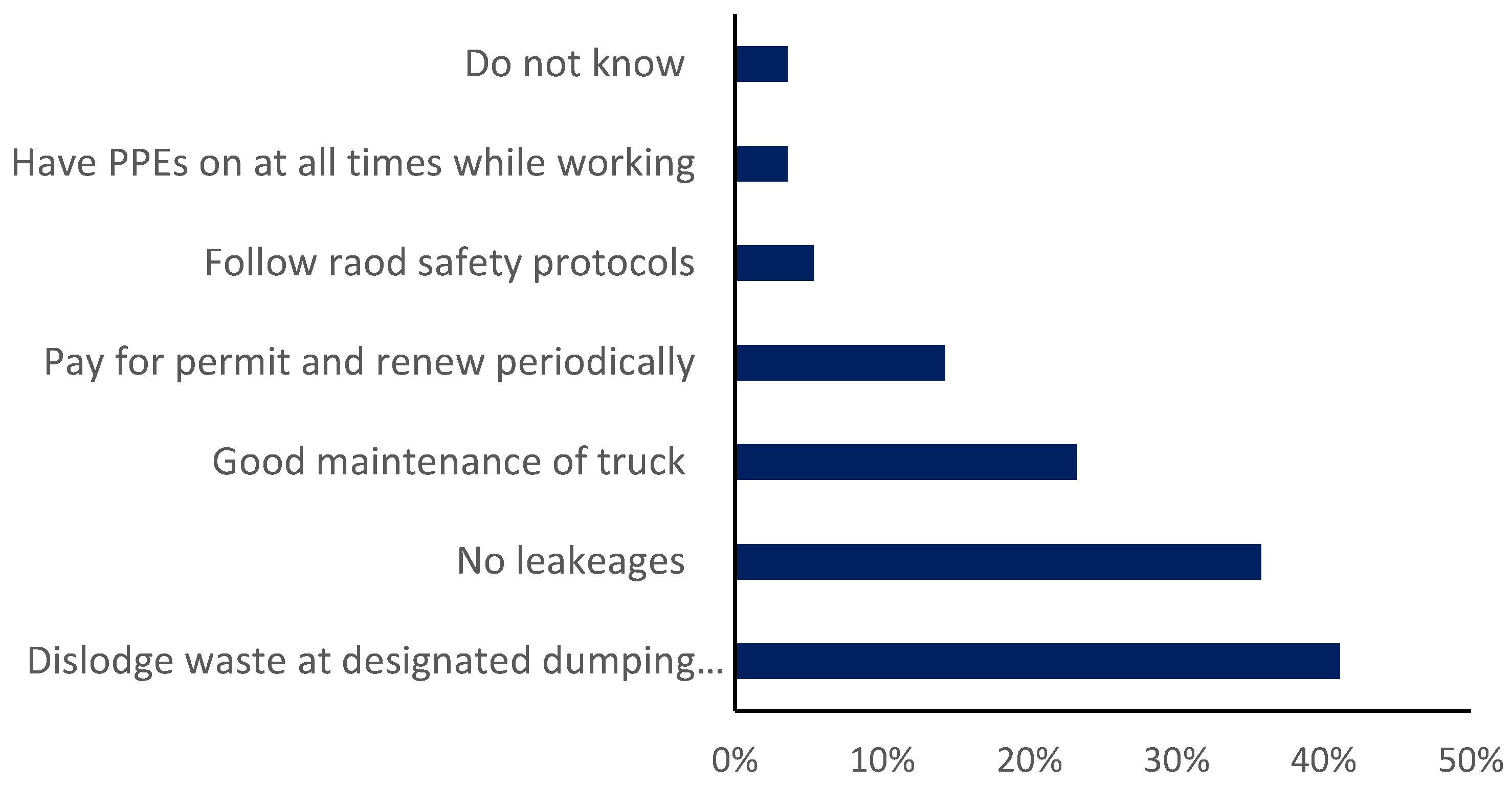

Several operational regulations are required to be adhered by septic truck operators which include acquiring of business permit, dislodging of fecal sludge in designated areas and ensuring that there are no leakages during emptying and transportation of fecal sludge. Truck drivers were asked to identify the major operational regulations that they should follow from the local authorities for their business activity. They were asked to list key operational regulations related to their business operations.

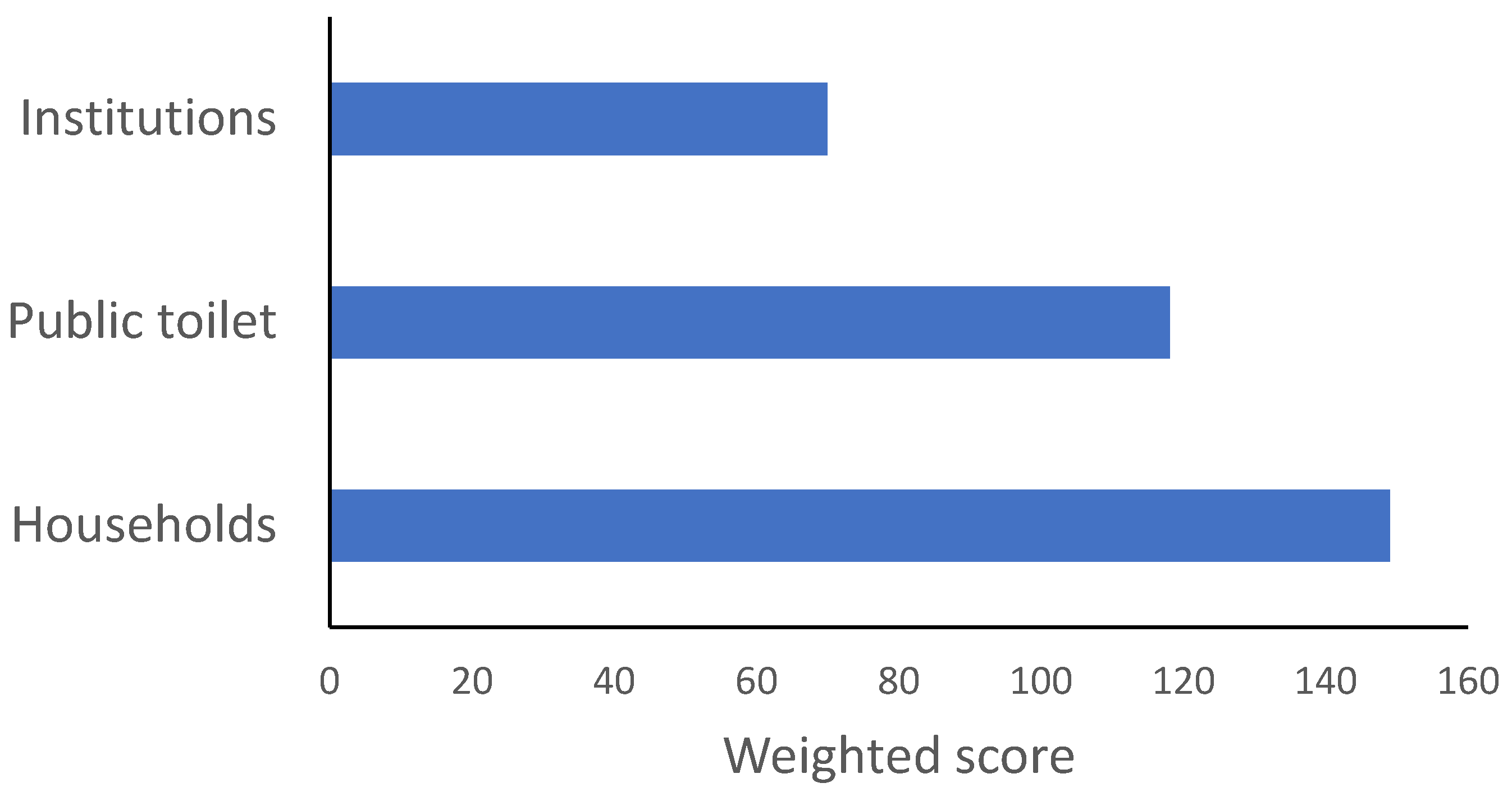

Figure 2 shows the percentage of vacuum truck operators perceiving each factor as a key regulation to their business activity. The top three operational regulations identified by the vacuum truck operators were dislodging waste at designated dumping sites, ensuring no leakages after service and good maintenance of vacuum trucks. Always Wearing PPEs while on duty was only mentioned by 3% of the vacuum truck operators as one of the key operational regulations indicating that ensuring safety was not a top priority for the service providers. Major clients served, ranked in order of importance, are households, public toilets and institutional facilities (

Figure 3). In addition to these clients, other clients include occasional contracts with major waste management company such as Zoomlion Ltd. to complement their services.

On average 32 households, 16 public toilets and 7 institutions are served monthly by the service providers (

Table 2). The average haulage distance is about 14 km and ranges between 2 km to 20 km. Emptying frequency varies from one client to the other. In a public toilet, frequency of emptying is one to six months while in households and institutions, it is six months to one year. Fee charged to clients is determined based on distance, volume of septic tank, nature of the roads leading to the source of the fecal sludge and type of client. A fee of GHS 453, GHS 432, and GHS 469 are charged for services provided to households, public toilets and institutions respectively

7. According to a study by Sagoe et al. (2019), the fee charged by vacuum truck operators in the Greater Accra Metropolis ranges between GHS 150 to GHS 600 per trip. The fees charged by the surveyed vacuum truck operators are set arbitrarily as there is not a well-structured tariff regime set by the MMDAs for private operators. Thus, service fees are either set by the service providers association or by the individual vacuum truck owners. Dislodging of feacal sludge at the designated dumping sites plant attracted an average of about GHS 30.67 per trip and on daily basis truck drivers dump on average 4 times.

4.3. Business Operation during COVID-19

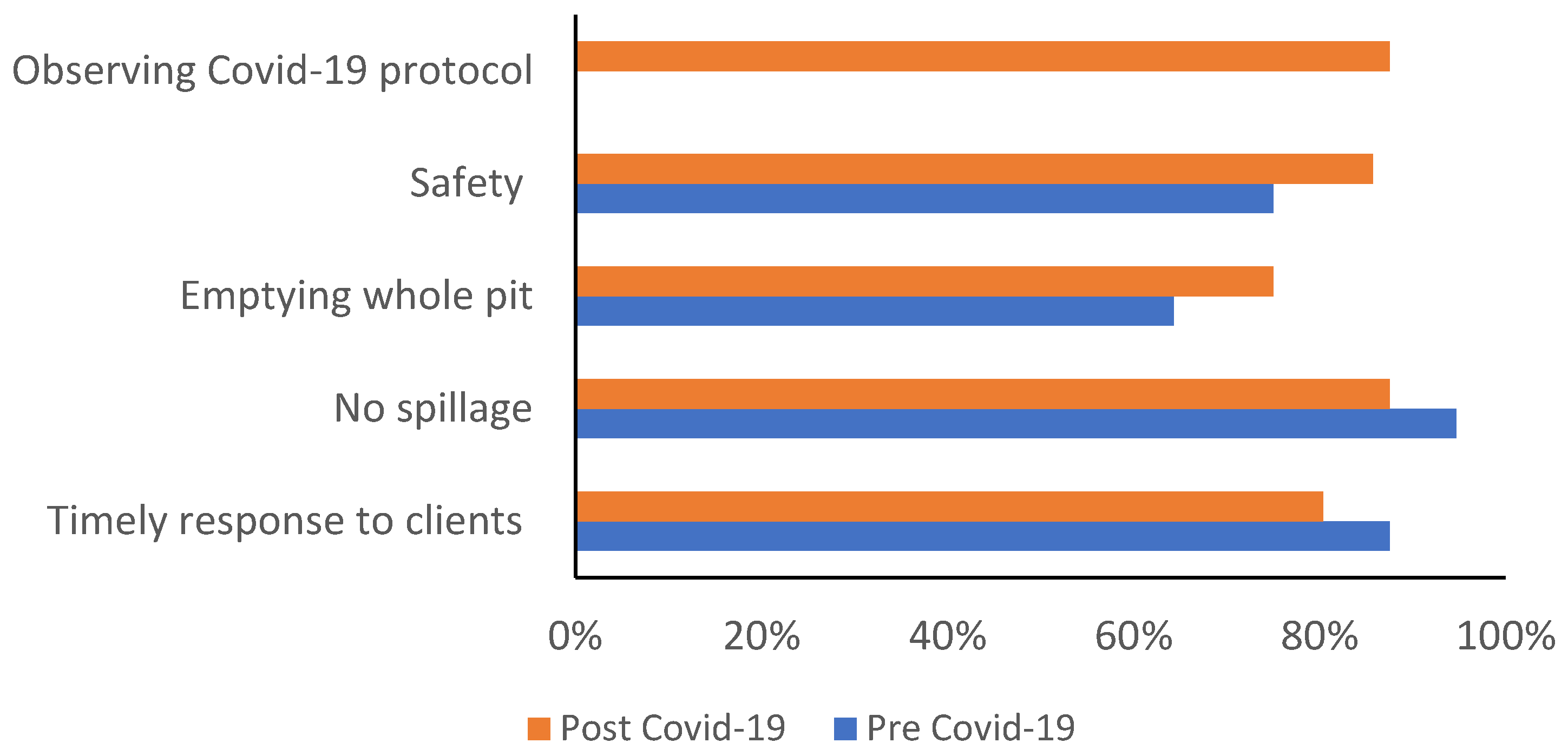

Vacuum truck drivers’ perception of good or a standard service pre and post COVID-19 era are assessed along the lines of how they respond to client call for service on timely manner; making sure there are no spillages when emptying clients’ septic tanks; ensuring that whole pit is emptied; endeavor to follow safety procedures and observe all COVID-19 protocols among others.

Figure 4 shows the percentage of vacuum truck operators perceiving each measure as key to a good service provision. While ensuring no spillage and timely response to clients’ request were the top ranked indicators for good service provision during pre-Covid-19 era, safety measures including observing Covid-19 safety protocol were the top ranked measures put in place by service providers. More than 85% respondents identified safety measures including no spillage as key to a good service provision during the pandemic. These were followed by timely response to clients and emptying the whole pit where more than two third of respondents identified these factors as key measures. Majority of truck drivers indicated that they respond to clients’ request for service on the same day. The client lead time (i.e., the time it takes for a client to receive service after placing an order) can be viewed as a general measure of efficiency of service delivery and can have implications for the efficiency of the entire sanitation vale chain.

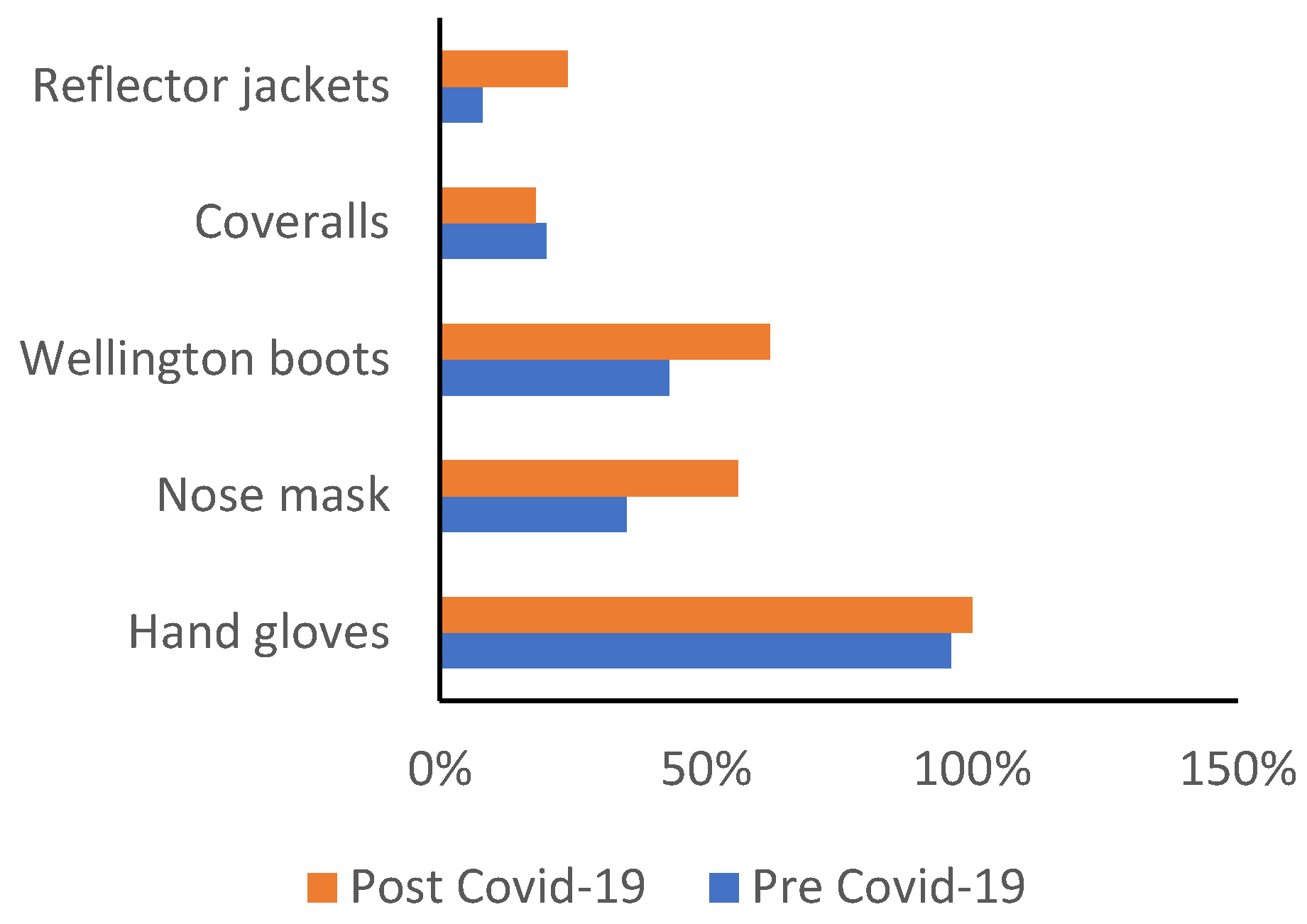

Sanitation service providers who come into contact with untreated sludge should wear standard PPEs such as safety boots, protective outerwear, heavy-duty gloves, medical masks, goggles always when handling or transporting sludge while taking measures to avoid spillage to ensure safety of staff and clients (WHO, 2020). The use of PPEs by vacuum truck operators have increased during the pandemic however the type of PPEs used varies across the service providers. In the pre-COVID 19 era, majority of respondents (about two third) indicated that they use two PPEs mainly gloves and another equipment such as mask or boots and only 22% indicated that they use multiple PPEs such as gloves, boots, mask and overalls at one time (

Figure 5). During the pandemic more respondents (about two third) indicated that they used multiple PPEs indicating that more sanitation service providers started using more PPEs. In terms of the type of PPEs, hand gloves are used by all or majority of vacuum truck operators both during the pandemic (100%) and pre COVID-19 era (96%) while more truck drivers started using nose masks (56%) and wellington boots (62%) during the pandemic compared to the pre COVID-19 era (

Figure 6). Other PPEs such as coveralls and reflector jackets are used by a smaller number of truck operators both during and pre COVID-19 era.

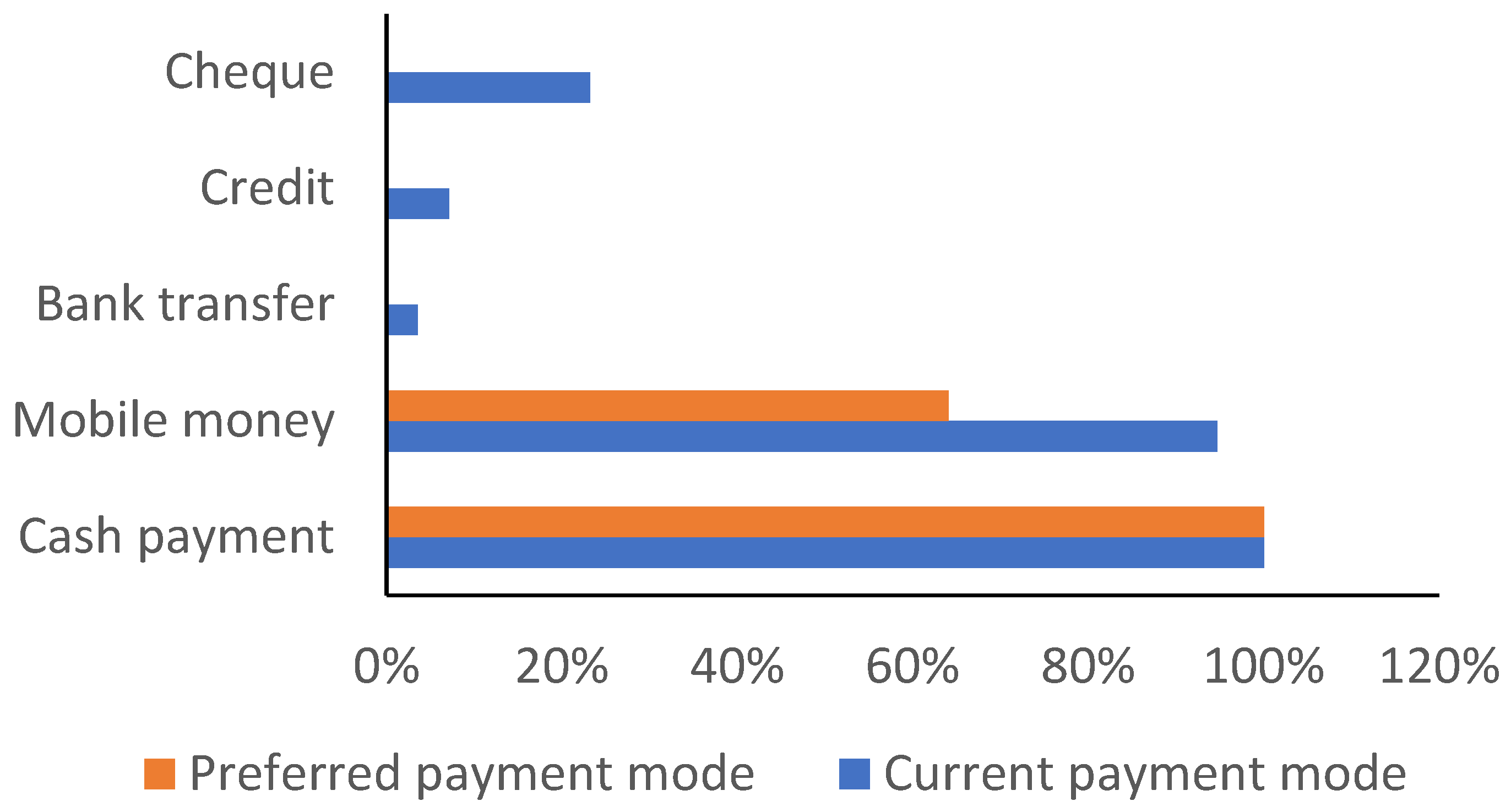

Figure 7 suggests that the most preferred medium of payment by the vacuum truck operators is cash payment after service followed by mobile money payment. In the face of the pandemic the exchange of cash could potentially be a cause for the spread of COVID-19. Electronic payment platforms are highly recommended by experts to be one of the possible means of containing the spread of COVID-19. In May 2020, the government of Ghana launched a digital financial services (DFS) policy. Even though the policy is believed to have been years in the making, the policy will support various measures the government is taking to leverage DFS in its COVID-19 response

8. It is estimated that about 19 million adults have 14.5 million active mobile money accounts which is good for the government’s effort in promoting the use of digital financial services. It is worth nothing that the DFS policy was not developed in response to COVID-19 but it is seen as a forward-looking policy that should help ensure government and citizens to have digital financial tools needed to cope with the new normal of social distancing as well as the growing economic uncertainties (Buruku, 2020).

4.4. Effect of COVID-19 on Business Operation

Understanding the impact of the pandemic on the operations and performance of sanitation service providers is important in designing coping mechanisms in the face of current and future pandemic. To understand the impacts, we first begin by examining service providers’ perceptions of the impact of the pandemic on their operations, revenue and cost items followed by objective measures of same before and during the pandemic. Majority of surveyed service providers indicated that the major impacts of the pandemic were:

Reduction in number of clients served during the lock down but it has gradually started to pick up ones lock down was eased or lifted.

Clients’ request for a reduction in fees for service rendered due to a reduction in their income caused by the pandemic.

Reduction in number of institutions requiring service during lock down.

Reduction in emptying frequency of clients.

Police hostility during lock down.

Major impact of the pandemic include reduction in the number of clients served and reduction in fees charged for services rendered. Number of clients served during COVID-19 has decreased on average by 20%, 24% and 29% for households, public toilet and institutions respectively (

Table 3). Moreover, fee charged for services rendered has decreased on average by 19% across all clients. The reduction in number of clients and the fee charged for services has consequently reduced revenue generation and income during the pandemic.

4.5. Operational Challenges and Training Need Assessment during the Pandemic

Sanitation service providers face a number of operational challenges and these are compounded by the pandemic. Key operational challenges that were already existing before the pandemic are poor road network, long que at the dumping sites, no permanent station for the vacuum trucks and no incentive mechanisms from the government (

Table 4). In addition to these, the sanitation service providers faced challenges caused by the pandemic included reduction in number of clients, reduced ability of clients to pay fees for services, occurrence of conflicts and police hostility.

Majority of surveyed vacuum truck operators did not receive any public support during the pandemic and only 16% of surveyed vacuum truck operators indicated that they have received some form of training pertaining to safe and effective service delivery during the pandemic which was provided by the public sector agencies responsible for their activities at the local government. This indicates that little to no attention has been paid to sanitation service providers by the public sector or other relevant stakeholders such as non-governmental organizations. More than 90% of the surveyed service providers indicated that there is a need for training on how to safely and effectively deliver service to clients. The areas where the different sanitation service providers felt that they needed capacity building to foster growth in their business operation included:

COVID-19 protocol for safe operations including how to deal with clients in the face of the pandemic.

Safety measures against hazards i.e., how to clean septic tanks while keeping safe from hazards

Dislodging without spillage and leakage

Quality customer service and record keeping of clients

Maintenance of vacuum truck

5. Opportunities for Circular Economy Solutions to Build Resilience to Pandemic

The COVID-19 pandemic and the associated government responses to the pandemic have restricted the movement of millions of people, impacting lives and jobs, disrupting international food supply chains and bringing global economies to a halt. In doing so, the pandemic and the lockdown measures have revealed our system’s exposure to a variety of risks (Ellen MacArthur Foundation, 2020). The economic turbulence because of the pandemic has hit a lot of industries and sectors of the world economy and many entrepreneurial ventures have struggled to survive (Costanza, 2020). In the context of the pandemic, the existing imbalance between available water supply and demand is expected to increase due to, among others, higher water consumption. Furthermore, during the pre-COVID19 era, in tandem with rapid urbanization, especially in the developing world, there has been an increase in waste generation in urban settings. Cities in developing countries generate massive amounts of solid and liquid waste in an environment where there is poor waste management, ranging from non-existing collection systems to ineffective disposal, causing air, water and soil contamination. This is exacerbated by the pandemic due to increased use of water and generation of more liquid and solid waste. However, opportunities also exist to adopt circular economy approaches connected with waste management, environmental awareness and local productive resilience (Costanza, 2020).

In the last decade, there has been a growing attention to the concept and development of a circular economy with the aim to provide a better alternative to the current practice which is largely linear, “take-make-dispose” economy (Ellen Macarthur Foundation, 2012). In contrast to today’s largely linear economy, a circular economy is seen as a new model with the aim to decouple economic growth from the use of natural resources (Ghisellini et al., 2015). One of the essential dimensions of promoting a CE is through creating and capturing value remaining in otherwise waste materials and maximizing that value to promote sustainable development. This involves improved waste collection combined with promoting resource recovery and reuse such as energy, water and nutrient recovery from different waste streams.

Circular business models mobilize local resources to reduce import dependence and diversify supplies for greater resilience. Recovering the water, energy, nutrients and other materials embedded in fecal sludge and wastewater is a key opportunity and is gaining more attention in developing countries. However, changing the business-as-usual scenario in the sanitation sector is a big challenge and requires much more efforts in the form of capacity development and the exploration of strong incentive systems for inter-sectoral collaboration to build new alliances along with the interlinked targets around water, energy, rural-urban linkages and food security.

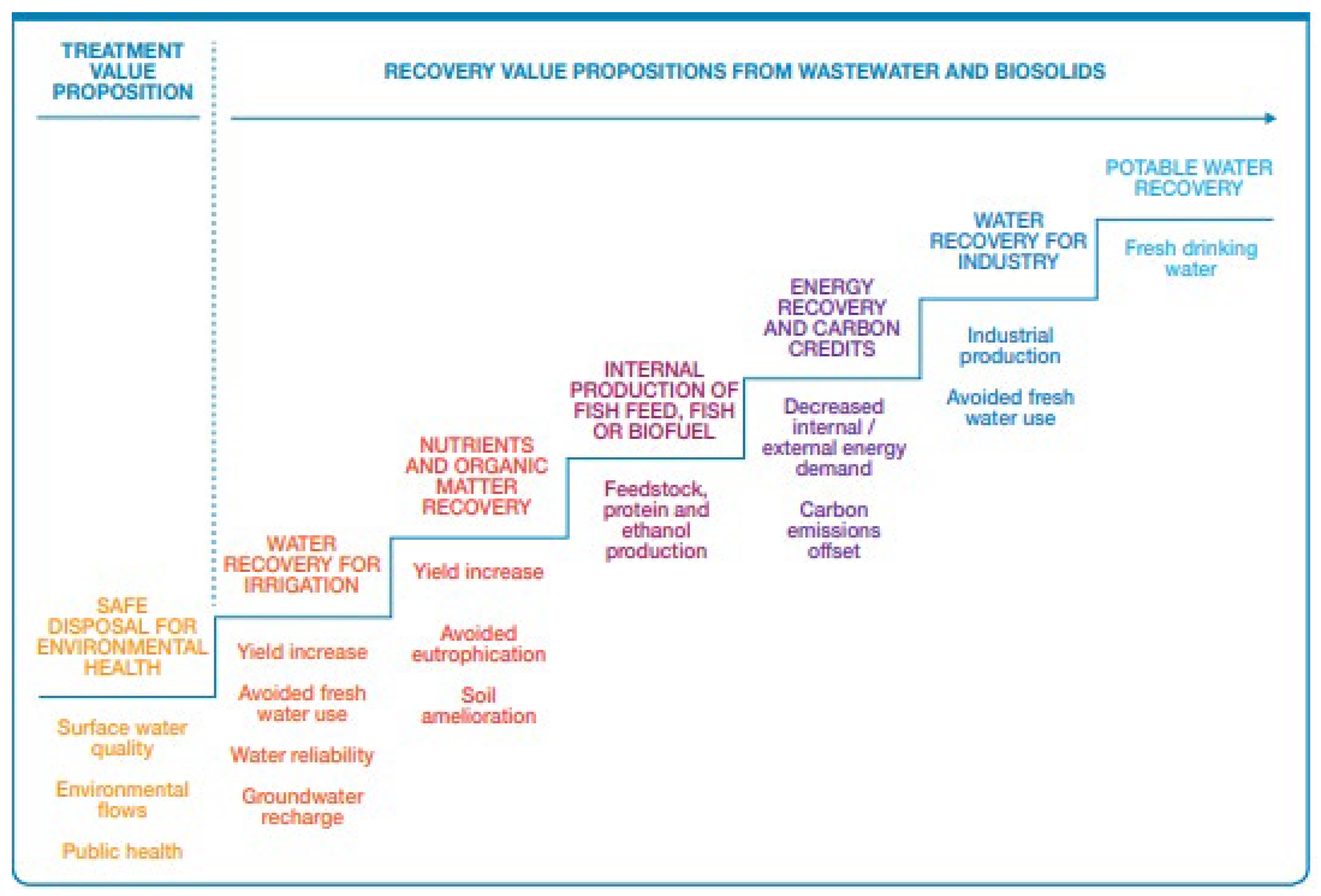

In view of the sanitation situation in Ghana, there is the need for a paradigm shift in the sanitation sector towards cost recovery, which is increasingly being supported by different organizations such as donors, government organizations and research institute pushing for private sector participation and waste to-wealth programs. This development advocates for a shift from waste ‘treatment for disposal’ to ‘treatment for reuse’ as the latter offers options for business development and cost recovery for the sanitation sector. Fecal sludge and wastewater offer a variety of options for recovering resources. In identifying potential businesses, it is important to understand the key challenges and service gaps in the sanitation service chain and develop a plan of action to address the needs. In doing this, all stages in the sanitation service chain (as depicted in

Figure 1) should be considered. For example, in fecal sludge management (FSM), there is the need to go beyond the provision of toilets to have efficient emptying and transport services and proper treatment and reuse. Fecal sludge is rich in water, nutrients and organic compounds and can be used as a source of energy and thus providing multiple value propositions.

5.1. Circular Economy Opportunities in Wastewater and Fecal Sludge

Figure 8 shows the variety of selected value propositions and options for cost recovery from wastewater and FS treatment and reuse ranging from the recovery of water for irrigation to potable water. This indicates that wastewater and FS reuse implementers have a wide range of options to select depending on the existing wastewater and FS collection and treatment infrastructure, the technology used for treatment, the available financing and the target end use. Stakeholder engagement in identifying the potential sanitation businesses is key to get buy-in from local implementers or stakeholders for successful implementation. The most common applications of the circular economy approach in wastewater and fecal sludge management in Africa are water reuse for irrigation, water reuse for aquaculture, nutrient and energy recovery from fecal sludge.

5.1.1. Water Reuse for Irrigation

Cities generate wastewater from domestic and other sources such as from industrial use. This wastewater represents a waste product which must be either disposed of safely or re-used as a resource. Apart from its value as water, it also contains nutrients which are beneficial for agricultural production. Agricultural production close to cities is the most cost-effective use of recycled urban water and more so during the pandemic. Circular economy approach within the context of urban food supply chains plays a key role in contributing towards resilience of the food production systems. Studies show that irrigated urban agriculture could produce as much as 90% of the leafy vegetables consumed in a city, particularly in Africa (Drechsel et al., 2007). As urban food supply chains are at high risk of being negatively affected by the COVID-19 pandemic, one of the key strategy and recommendation for maintaining urban food supply is promoting urban agriculture and shorter food chains (Drechsel, 2020). However, with the surge in use of water during the pandemic, use of untreated or partially treated wastewater for irrigation may pose health risks to farmers and consumers as the SARS-CoV-2 can occur in grey water, including hand washing water from different facilities which may not be transported to treatment facilities. Grey water from such facilities should be handled with care and appropriately disposed of to avoid possible infection.

5.1.2. Water Reuse for Aquaculture

The development of an integrated wastewater treatment plant and aquaculture production system in developing countries represents a low-cost option for wastewater treatment and a source of food production. The use of treated wastewater for aquaculture, i.e., growing fish, fingerling and animal feed in treated wastewater-fed ponds, is a unique system that has potential to create viable fish-farming businesses, support livelihoods and ensure food security while recovering costs for treatment facilities in low-income countries. The development of an integrated wastewater treatment plant and aquaculture system has been promoted by international organizations such as the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP), the World Bank and the International Water Management Institute (IWMI) in developing countries because it represents a low-cost option for wastewater treatment and a source of food production (Otoo and Drechsel 2018). IWMI has implemented a water reuse aquaculture business model in Kumasi, Ghana by setting up a public private partnership between the Kumasi Metropolitan Assembly and private entity.

While a wastewater-fed aquaculture system presents an opportunity for a viable business, success of these systems depends, among other factors, on compliance with national or international safety guidelines. In this type of production system, there are health concerns, which should be addressed to safeguard workers’ and consumers’ health. The producer should ensure that the quality of water in waste stabilization ponds meets required standards for fish and/or aquatic crop production and good personal hygiene as well as good handling and cooking practices are maintained to ensure food safety. In the face of the pandemic, it is important to study contribution of wastewater in the transmission of the SARS-CoV-2 corona virus, human health risks it poses and how it can be inactivated or eliminated from the wastewater so that it doesn’t find route into the food system. The World Health Organization (WHO) has developed guidelines for defining appropriate levels of treatment needed for different types of water reuse, including for aquaculture, to ensure public health protection (WHO 2006). Our study (in component 2) shows that SARS-CoV-2 can be transported through sewers into wastewater treatment plants but are possibly inactivated rapidly within the wastewater treatment system due to the adverse water quality measures of the wastewater. This implies that water reuse for aquaculture poses less or no risks to users.

5.1.3. Nutrient and Energy Recovery

Millions of tons of human excreta are generated every day and collected as fecal sludge in developing countries. This waste is rich in water, nutrients and organic compounds and can be used as a source of energy. Yet in many parts of the world, including Ghana where resources are scarce, the potential value of reusing this waste remains largely untapped. Sustainable fecal sludge management (FSM) can be achieved with integrated circular economy business models that go beyond standard sanitation services and turn FS into valuable resources such as nutrient, organic matter and energy.

Recycling of solid and liquid waste to produce safe compost and co-compost products for use in agriculture, has the potential to provide a win-win situation by reducing waste flows, ensuring environmental health, enhancing soil properties and creating livelihoods. The compost products offer safe FS products which can be tailored for different agricultural uses, consequently, turning a sanitation challenge into source of revenue that improves the financial and organizational sustainability of the sanitation value chain. The successful recovery of nutrient from FS and other organic waste streams for agricultural use should be based on a strong partnership with key actors bridging between sanitation and agriculture and includes different actors such as the private sector and government entities. IWMI has implemented FS to compost business models in Ghana by establishing public private partnerships.

6. Conclusion and policy implication

In this era of pandemic, the management of waste, both solid and liquid poses significant level of risk. Since the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic there has been particular attention to handwashing globally to protect against viral disease. According to WHO, the provision of safe water, sanitation and hygiene (WASH) and waste management practices are essential in preventing transmission of COVID-19. Sanitation service providers and workers are very important for operational support in the COVID-19 era and any potential future pandemic. Despite the recognition that continuous WASH services are the best way to defend against COVID-19, little attention has been paid during the pandemic to sanitation service providers as the focus in COVID-19 responses across the world has been on healthcare systems, developing vaccines and treatments and the safety of healthcare workers. However, equally important are the availability of clean water and access to safe sanitation service. This study assessed the operational and economic impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on sanitation service providers specifically vacuum truck operators providing emptying and transportation services to various sectors in the Greater Accra Metropolitan Assembly.

- -

Major impact of the pandemic on the operations of sanitation service providers are reduction in the number of clients served and reduction in fees charged for services rendered. Number of clients served by the vacuum truck operators during COVID-19 has decreased on average by 20%, 24% and 29% for households, public toilet and institutions respectively while fee charged for services rendered was reduced on average by 19% across all clients consequently reducing revenue generation and income during the pandemic.

- -

Electronic payment platforms such as mobile money can be used as one of the possible means of curtailing the spread of COVID-19. The predominant and preferred medium of payment for service rendered by vacuum truck operators is cash payment after service followed by mobile money. While cash payment could potentially contribute to spread of COVID-19, using electronic payment platforms are one of the possible means to reduce the spread of COVID-19. Government of Ghana could leverage on its Digital Financial Services (DSF) policy in its COVID-19 response.

- -

Wearing PPEs always was not considered as one of the key operational regulations in the pre-COVID-19 period. Operational measures such as desludging of fecal sludge at designated dumping site and ensuring that there is no leakage while providing service to clients were listed as the major operational regulations.

- -

Need for professionalization of vacuum truck operators: The use of PPEs by vacuum truck operators have increased during the pandemic however the type of PPEs used varies across the service providers indicating that use of PPEs while emptying is subject to the behaviour of service providers. Wearing of PPEs while on duty are critical in protecting the sanitation service providers as well as clients against COVID-19. However not all sanitation providers wear appropriate PPEs. Thus, there is a need to enforce the wearing of PPEs by relevant public authorities. To improve affordability of PPEs, there is a need to provide incentive mechanisms or partial subsidization of PPEs by the government to promote wider use.

- -

Need for training on service provision and coping mechanisms in the face of the pandemic: Most vacuum truck operators did not receive any public support during the pandemic and only few indicated that they have received some form of training pertaining to safe and effective service delivery during the pandemic which was provided by the public sector agencies responsible for their activities at the local government level. As part of the professionalization of sanitation service providers, we recommend that training on how to provide quality customer service while ensuring safety be provided by waste management experts within the metropolitan and municipal assemblies.

- -

Circular economy approaches in wastewater and fecal sludge management that have potential for building resilience against the pandemic include water reuse for irrigation, water reuse for aquaculture, nutrient and energy recovery from fecal sludge

- -

Circular economy approach within the context of urban food supply chains plays a key role in contributing towards resilience of the food production systems. As urban food supply chains are at high risk of being negatively affected by the COVID-19 pandemic, promoting urban agriculture and shorter food chains are key strategies recommended to maintain urban food supply.

References

- Alemi, S., Nakamura, K., Seino, K., & Hemat, S. (2022). Status of water, sanitation, and hygiene and standard precautions in healthcare facilities and its relevance to COVID-19 in Afghanistan. Environmental Health and Preventive Medicine, 27(1). [CrossRef]

- Andersson, K., Otoo, M., & Nolasco, M. (2018). Innovative sanitation approaches could address multiple development challenges. In Water Science and Technology (Vol. 77, Issue 4, pp. 855–858). IWA Publishing. [CrossRef]

- Auerbach, D. (2016). Sustainable sanitation provision in urban slums - the Sanergy case study. In A. E. Thomas (Ed.), Broken pumps and promises: Incentivizing impact in environmental health (pp. 217–245).

- Blackett, I., Hawkins, P., & Heymans, C. (2014). Targeting the urban poor and improving services in small towns. The missing link in sanitation service delivery: A review of fecal sludge management in 12 cities.

- Boamah, L. A. (2011). The Environmental Sanitation Policy of Ghana (2010) and Stakeholder Capacity: A Case Study of Solid Waste Management in Accra and Koforidua. UPPSALA UNIVERSITET.

- Caruso, B. A., & Freeman, M. C. (2020). Shared sanitation and the spread of COVID-19: risks and next steps. The Lancet Planetary Health, 4(5), 173.

- Gill, L., Mahon, J. Mac, Knappe, J., Gharbia, S., & Pilla, F. (2018). Desludging Rates and Mechanisms for Domestic Wastewater Treatment System Sludges in Ireland. www.epa.ie.

- Hawkins, P., Blackett, I., & Heymans, C. (2014). The missing link in sanitation service delivery : a review of fecal sludge management in 12 cities. Water and Sanitation Program: Research Brief, April, 1–8. http://documents.worldbank.org/curated/en/2014/04/19549016/targeting-urban-poor-improving-services-small-towns-missing-link-sanitation-service-delivery-review-fecal-sludge-management-12-cities.

- Kosi, C., & Saba, S. (2020). COVID-19: Implications for food, water, hygiene, sanitation, and environmental safety in Africa-A case study in Ghana. [CrossRef]

- Lüthi, C., Morel, A., Tilley, E., & Ulrich, L. (2011). Community-Led Urban Environmental Sanitation Planning: CLUES Complete Guidelines for Decision-Makers with 30 Tools.

- Mbéguéré, M., Gning, J. B., Dodane, P. H., & Koné, D. (2010). Socio-economic profile and profitability of faecal sludge emptying companies. Resources, Conservation and Recycling, 54(12), 1288–1295. [CrossRef]

- Oppong, J. R. (2020). The African COVID-19 anomaly. African Geographical Review, 39(3), 282–288. [CrossRef]

- Parkinson, J., & Quader, M. (2008). The challenge of servicing on-site sanitation in dense urban areas: Experiences from a pilot project in Dhaka. Waterlines, 27(2), 149–163. [CrossRef]

- Sagoe, G., Danquah, F. S., Amofa-Sarkodie, E. S., Appiah-Effah, E., Ekumah, E., Mensah, E. K., & Karikari, K. S. (2019). GIS-aided optimisation of faecal sludge management in developing countries: the case of the Greater Accra Metropolitan Area, Ghana. Heliyon, 5(9). [CrossRef]

- Smiley, S. L., Agbemor, B. D., Adams, E. A., & Tutu, R. (2020). COVID-19 and water access in Sub-Saharan Africa: Ghana’s free water directive may not benefit water insecure households. African Geographical Review, 39(4), 398–404. [CrossRef]

- Tilley, Elizabeth., Ulrich, Lukas., Lüthi, Christoph., Reymond, Philippe., & Zurbrügg, Christian. (2014). Compendium of sanitation systems and technologies. Eawag.

- Tweneboah Kodua, T., & Asomanin Anaman, K. (2020). Indiscriminate open space solid waste dumping behaviour of householders in the Brong-Ahafo region of Ghana: a political economy analysis. Cogent Environmental Science, 6(1). [CrossRef]

- van Welie, M. J., Truffer, B., & Yap, X. S. (2019). Towards sustainable urban basic services in low-income countries: A Technological Innovation System analysis of sanitation value chains in Nairobi. Environmental Innovation and Societal Transitions, 33, 196–214. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q., & Liu, L. (2021). On the Critical Role of Human Feces and Public Toilets in the Transmission of COVID-19: Evidence from China. Sustainable Cities and Society, 75. [CrossRef]

| 1 |

There were about 120 trucks in GAMA in the year 2017 (Sagoe et al., 2019). |

| 2 |

The unavailability of funds to manage state-owned logistics and infrastructure for fecal sludge management is what has resulted in the dominance of private truck operators along the sanitation service chain in Accra. |

| 3 |

In a fashion like Ghana Private Road Transport Union (GPRTU) and the Progressive Transport Owners Association (PROTOA). |

| 4 |

|

| 5 |

|

| 6 |

|

| 7 |

Exchange rate at the time of survey was GHS 1 = USD 0.1741. |

| 8 |

|

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).