Introduction

Type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) is associated with a substantial economic and clinical burden, and its incidence is expected to grow in decades to come [

1]. By 2045, this is projected that the the prevalence will reach 629 million. The disease affects around 8.3% of adults around the world, with the greatest number of patients between the ages of 40 and 59 [

2].MENA(Middle east and North Africa) was the highest age-adjusted prevalence in 12.2%, with one in eight adults living with diabetes [

3].

The age-adjusted prevalence of diabetes in Iraq had been 19.7%, with 55.7% of those with diabetes being previously undiagnosed. In Iraq, 8.7% of individuals had been diagnosed with diabetes, and 11% were found to have undiagnosed diabetes with screening. In addition, 29.1% of the population screened had prediabetes, resulting in a prevalence of hyperglycemia of 48.8%, with only 51.2% of the screened population being normoglycemic. The prevalence of diabetes in both sexes peaked in the years of 46 and 60. Slightly more females than males had diabetes, and about 70.3% of individuals had a body mass index of 25 kg/m2.

Diabetes is very common Basra, Iraq, affecting one in five adults. The diabetes epidemic will result in a strain on health care systems' financial resources [

4].

Clinical inertia is defined as the failure of providers to alter therapy in the face of clear indications [

5].Poor glycemic control is multifactorial and could be due to healthcare workers-related factors, patient-related factors like poor adherence, or factors related to the disease itself [

6]. Late initiation and refusal of insulin therapy have been identified to be among the main causes of poor glycemic control and the development of irreversible complications [

7]

The aim of this study was to identify patient beliefs about insulin that may be barriers in type 2 diabetes patients to initiating insulin treatment when recommended by their physician.

Objective

The aim of this study was to identify patient beliefs about insulin that may be barriers in type 2 diabetes patients to initiating insulin treatment when recommended by their physician.

Methods

This cross-sectional observational study involved 671 individuals with poorly controlled type 2 diabetes mellitus, with HbA1c levels exceeding 10%. These patients required either the initiation or escalation of their current insulin therapy. All participants were referred to the Thi-Qar Specialized Diabetes Endocrine and Metabolism Center (TDEMC) for their first consultation between January 2022 and July 2022.

Initial demographic, clinical, and biochemical data were collected during the first assessment. Various therapeutic options were discussed, including different insulin therapy regimens tailored to each patient. Patients' attitudes toward beginning insulin therapy, both positive and negative, were documented. Those who avoided treatment provided various reasons, which were recorded verbatim.

The main reasons for refusing insulin therapy, discussed during interviews between the clinician (the researcher) and the patients with poorly controlled T2DM, included: fear of injections, concerns about dependence, belief that insulin is a last-resort option, fear of hypoglycemia, potential complications, cost, difficulty in dose calculation, negative opinions from others, social stigma, inconvenience with lifestyle, interference with work, storage difficulties, fear of weight gain, reliance on others, and lack of confidence in the drug.

For statistical analysis, IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 26.0 (Armonk, NY: IBM Corp.) was used to analyze various variables. Data were expressed as mean ± standard deviation (SD) or frequency (%). Pie charts were employed for graphical representation of the data.

Results

The table summarizes the characteristics of individuals with Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus (T2DM) at presentation. The cohort consisted of 46.6% men and 53.4% women, with a mean age of 50.20 ± 8.50 years, ranging from 25 to 79 years. Household roles were common, with 48.0% being housewives. The mean duration of T2DM was 8.22 ± 3.91 years, varying from 1 to 23 years. Most participants were married (96.0%) and non-smokers (86.9%). Educational levels varied, with primary school education (28.0%) and illiteracy (21.9%) being prevalent. Over half had a family history of diabetes (52.6%). The mean Body Mass Index (BMI) was 29.14 ± 4.96 kg/m². Average systolic and diastolic blood pressures were 136 ± 23 mmHg and 76 ± 11 mmHg, respectively. Common comorbidities included hypertension (44.4%), peripheral neuropathy (31.9%), and retinopathy (31.6%). The mean glycated hemoglobin (HbA1c) was 13.29 ± 1.53%, while mean random and fasting plasma glucose levels were 252.28 ± 82.66 mg/dl and 198.8 ± 45.51 mg/dl, respectively. Blood urea averaged 32.64 ± 10.6 mg/dl, and serum creatinine averaged 0.77 ± 0.20 mg/dl. Average total cholesterol was 184.13 ± 46.92 mg/dl, and triglycerides averaged 220.48 ± 121.76 mg/dl.

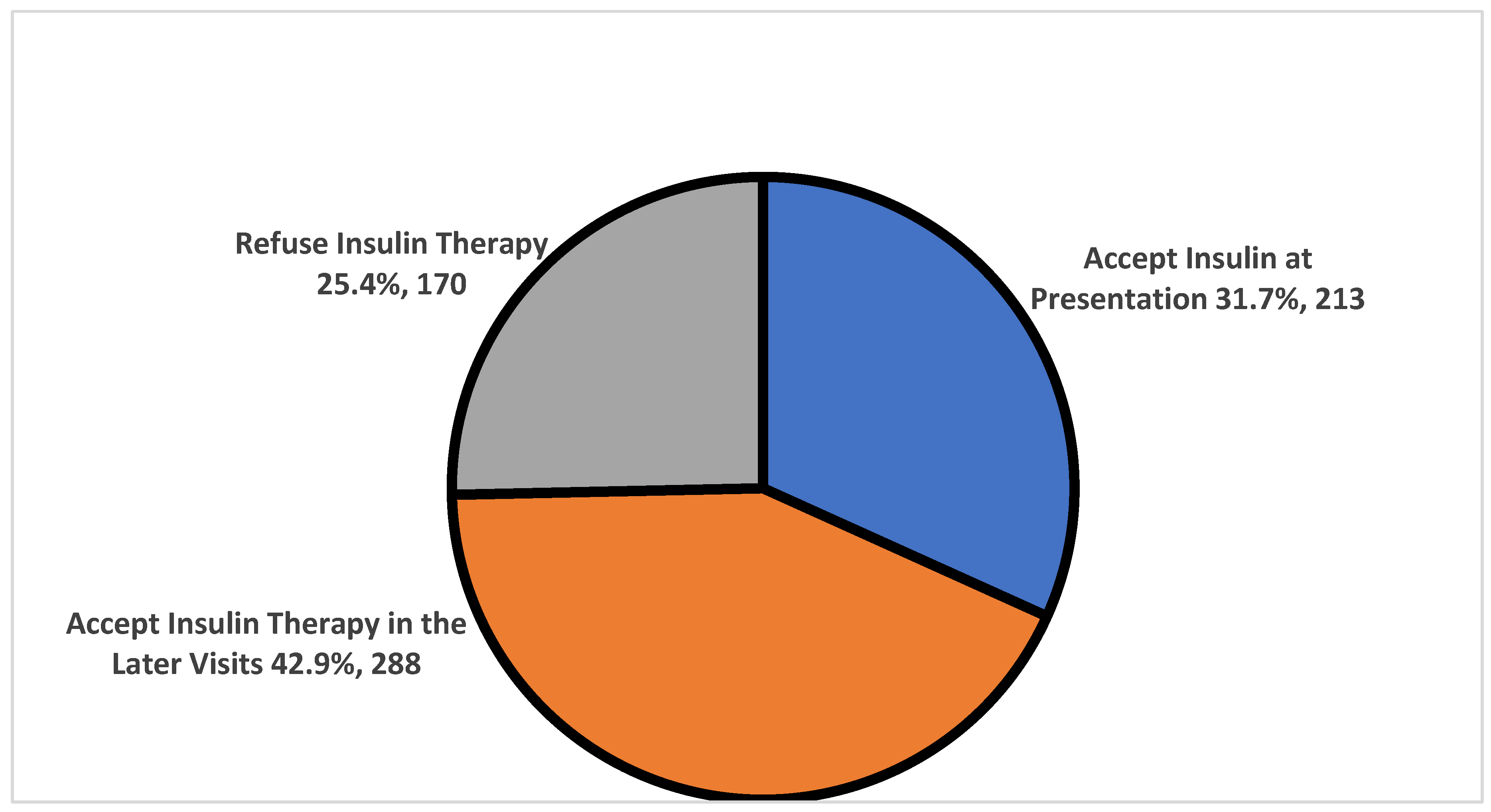

About 25% of the enrolled cohort (n=170) refused the initiation of the insulin therapy, about 32% (n=213) accepted insulin therapy directly at presentation. The rest 43% (n=288) accepted insulin initiation at later visits. The median duration to start insulin for individuals with T2DM was (4 ± 0.4 months) with a range between (0 – 32 months) as shown in (

Figure 1).

The median duration to start insulin for individuals with T2DM was (4 ± 0.4 months) with a range between (0 – 32 months).The causes of insulin prescription inertia among 458 individuals with T2DM who refused insulin therapy as initial therapy are presented in

Table 2. The most common cause reported was fear from injection, accounting for 28.8% of the reported causes. 37.9% of individuals believed that insulin therapy causes dependence. 22.1% thought that insulin therapy was the last choice for treatment. Hypoglycemia was cited as a cause of inertia by 13.9% of individuals, while 16.5% were concerned about complications. Cost was reported as a cause by 4.9% and 9.4% found it difficult to calculate the insulin dose. Negative opinions from others were reported by 28.5% of individuals. Social stigma, inconvenience with life, interference with job, difficult storage, fear from weight gain, depend on others, and lack of confidence in the drug were also reported as causes, ranging from 3.3% to 13.1%.

The patients on different antidiabetic therapy as shown in (

Table 3).

The modalities of therapy used at presentation for individuals with T2DM are presented in

Table 3. Metformin was the most commonly used therapy (94.0%), followed by gliclazide MR 60 mg (86.3%), DPP inhibitors (47.2%), pioglitazone 15 mg (44.3%), and SGLT2i (39.8%). Less commonly used therapies included glargine (16.2%), NPH (13.1%), Premixed insulin (1.3%), Insulin degludec/insulin aspart (0.9%), and Actrapid (0.1%).

Discussion

The results of this study provide insight into the clinical and demographic characteristics of individuals with T2DM at presentation in a population. The mean age of 50.20 ± 8.50 years is consistent with a recent meta-analysis that demonstrated an age range of 47-62 years in T2DM populations [

8]. The high prevalence of female participants (53.4%) may be due to the higher susceptibility of women to developing T2DM [

9].

Hypertension was found to be a common comorbidity in this cohort, which is in line with other studies that have demonstrated a strong link between T2DM and hypertension [

10]. Given the high prevalence of hypertension in this population, it is imperative that clinicians monitor and manage hypertension appropriately in patients with T2DM to prevent cardiovascular complications.

The mean BMI of 29.14 ± 4.96 kg/m² is consistent with the obesity epidemic that is linked to T2DM. A higher BMI is a known risk factor for T2DM, and obesity is associated with worse glycemic control and increased risk of complications [

10]. The high prevalence of housewives and low educational levels in this population may contribute to the observed high prevalence of obesity, as individuals with lower education and sedentary lifestyles are at higher risk for obesity [

11].

The high mean HbA1c levels (13.29 ± 1.53%) suggest poor glycemic control among the study participants. This is concerning, as uncontrolled hyperglycemia is a major contributor to the development and progression of diabetic complications. The mean fasting plasma glucose levels (198.8 ± 45.51 mg/dl) and random plasma glucose levels (252.28 ± 82.66 mg/dl) were also high, indicating significant hyperglycemia [

12].

the results of this study indicate that a significant proportion of patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) may be hesitant to initiate insulin therapy. The reluctance to use insulin therapy may be due to various reasons, including fear of injections, concerns about hypoglycemia, and negative attitudes towards insulin therapy. The finding that 25% of the enrolled cohort refused insulin therapy is consistent with previous studies that have reported a refusal rate of up to 40% [

13,

14].

On the other hand, the finding that about one-third of the study subjects accepted insulin therapy directly at presentation suggests a more positive attitude towards insulin therapy. This higher acceptance rate may be attributed to better patient education and counseling or a greater understanding of the benefits of early insulin therapy initiation. A recent systematic review and meta-analysis found that early insulin initiation can improve glycemic control and reduce the risk of diabetic complications [

15].

The prolonged median duration (4 ± 0.4 months) to start insulin therapy in those who accepted insulin initiation at later visits highlights the potential gap in patient education and counseling regarding the importance of early initiation of insulin therapy. The delay in insulin initiation may contribute to suboptimal glycemic control, leading to increased risk of diabetic complications. Several studies have reported that early insulin initiation can improve HbA1c levels and reduce the risk of complications compared to delayed initiation [

16].

The results from

Table 2 of this study provide insight into the reasons why individuals with T2DM may be hesitant to initiate insulin therapy, leading to insulin prescription inertia. One of the most common reasons for insulin prescription inertia was the fear of dependence on insulin, with 37.9% of individuals reporting this as a concern. In addition, negative opinions from others and social stigma were reported as reasons for insulin prescription inertia by 28.5% and 13.1% of individuals, respectively. These findings are consistent with previous studies that have reported fear of injections, anxiety about self-injection, and concerns about social stigma as barriers to insulin therapy [

13].

Another significant reason for insulin prescription inertia among individuals with T2DM was the perception that insulin therapy is the last resort, with 22.1% of individuals expressing this concern. This perception is not necessarily accurate, as some studies have shown that early insulin therapy initiation can improve glycemic control and reduce the risk of complications [

17].Insulin prescription inertia may also be due to concerns about hypoglycemia and complications, as seen in 13.9% and 16.5% of individuals, respectively.

Additional reasons for insulin prescription inertia reported by individuals with T2DM include the cost of insulin, difficulty in dose calculation, inconvenience with daily life, interference with job responsibilities, and difficulty in storage. These concerns highlight the need for patient education and support to address practical barriers to insulin therapy.

Table 3 of this study outlines the modalities of therapy at presentation for individuals with T2DM. The most commonly prescribed medication at presentation was metformin, given to 94% of individuals. This reflects the current standard of care, as metformin is recommended as first-line therapy for T2DM due to its ability to improve glucose control and reduce cardiovascular disease risk [

12].

Insulin therapy was initiated in a relatively small proportion of individuals, with glargine and NPH being the most commonly prescribed insulins. Premixed insulin, insulin degludec/insulin aspart, and short-acting insulin were used in a very limited number of cases. The use of insulin therapy is consistent with current guidelines that recommend insulin therapy for individuals with T2DM who have not achieved glycemic control with other medications or who have significant symptoms or hyperglycemia [

12]. However, previous studies have reported a reluctance to initiate insulin therapy among patients with T2DM due to various concerns, as mentioned in

Table 2 [

18].

DPP inhibitors and SGLT2 inhibitors were prescribed to nearly half and 40% of the enrolled individuals, respectively. These medications are newer classes of medications for T2DM that have shown efficacy in improving glycemic control and reducing the risk of cardiovascular and renal events [

12,

19]. However, the use of these medications may be limited by their cost and insurance coverage, and they may not be appropriate for all patients with T2DM [

20].

Conclusion

The study emphasizes the significant impact of Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus (T2DM) and its associated comorbidities on the population. Effective management strategies, particularly education and lifestyle changes, are essential to mitigate diabetic complications and improve health outcomes. Findings indicate that patient education and counseling are crucial to overcoming barriers to insulin therapy, promoting shared decision-making, and personalized treatment plans to enhance patient acceptance and adherence. The study also notes the prevalent use of metformin as per current guidelines, while the limited use of insulin and newer medications may reflect preferences and concerns of both patients and providers. Ongoing education and support about medication benefits and risks are necessary to improve adherence and outcomes in T2DM.

Acknowledgments

Author would like to thank all enrolled individuals for their cooperation in performing this study.

Conflict of Interest

The authors had no conflict of interest, The authors received no funding for this article.

References

- Romera I, Diaz S, Sicras-Mainar A, Lopez-Simarro F, Dilla T, Artime E, et al. Clinical Inertia in Poorly Controlled Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus Patients with Obesity: An Observational Retrospective Study. Diabetes Ther. 2020;11(2):437-51.

- Cho NH, Shaw J, Karuranga S, Huang Y, da Rocha Fernandes J, Ohlrogge A, et al. IDF Diabetes Atlas: Global estimates of diabetes prevalence for 2017 and projections for 2045. 2018;138:271-81.

- Chivese T, Hoegfeldt CA, Werfalli M, Yuen L, Sun H, Karuranga S, et al. IDF Diabetes Atlas: The prevalence of pre-existing diabetes in pregnancy–A systematic review and meta-analysis of studies published during 2010–2020. 2021:109049.

- Mansour AA, Al-Maliky AA, Kasem B, Jabar A, Mosbeh KA. Prevalence of diagnosed and undiagnosed diabetes mellitus in adults aged 19 years and older in Basrah, Iraq. Diabetes Metab Syndr Obes. 2014;7:139-44.

- Almigbal TH, Alzarah SA, Aljanoubi FA, Alhafez NA, Aldawsari MR, Alghadeer ZY, et al. Clinical Inertia in the Management of Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus: A Systematic Review. Medicina (Kaunas). 2023;59(1).

- Yosef T, Nureye D, Tekalign E. Poor Glycemic Control and Its Contributing Factors Among Type 2 Diabetes Patients at Adama Hospital Medical College in East Ethiopia. Diabetes Metab Syndr Obes. 2021;14:3273-80.

- Al Futaisi A, Alosali M, Al-Kazrooni A, Al-Qassabi S, Al-Gharabi S, Panchatcharam S, et al. Assessing Barriers to Insulin Therapy among Omani Diabetic Patients Attending Three Main Diabetes Clinics in Muscat, Oman. Sultan Qaboos University Medical Journal. 2022;22(4):525.

- Saeedi P, Petersohn I, Salpea P, Malanda B, Karuranga S, Unwin N, et al. Global and regional diabetes prevalence estimates for 2019 and projections for 2030 and 2045: Results from the International Diabetes Federation Diabetes Atlas, 9(th) edition. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2019;157:107843.

- Tsimihodimos V, Gonzalez-Villalpando C, Meigs JB, Ferrannini E. Hypertension and Diabetes Mellitus. Hypertension. 2018;71(3):422-8.

- Lee SW, Kim HC, Lee JM, Yun YM, Lee JY, Suh I. Association between changes in systolic blood pressure and incident diabetes in a community-based cohort study in Korea. Hypertens Res. 2017;40(7):710-6.

- Aslani A, Faraji A, Allahverdizadeh B, Fathnezhad-Kazemi A. Prevalence of obesity and association between body mass index and different aspects of lifestyle in medical sciences students: A cross-sectional study. Nurs Open. 2021;8(1):372-9.

- Introduction: Standards of Medical Care in Diabetes—2021. Diabetes Care. 2020;44(Supplement_1):S1-S2.

- Peyrot M, Rubin RR, Khunti K. Addressing barriers to initiation of insulin in patients with type 2 diabetes. Prim Care Diabetes. 2010;4 Suppl 1:S11-8.

- Stark Casagrande S, Fradkin JE, Saydah SH, Rust KF, Cowie CC. The prevalence of meeting A1C, blood pressure, and LDL goals among people with diabetes, 1988-2010. Diabetes Care. 2013;36(8):2271-9.

- Meneghini, L. Early Insulin Treatment in Type 2 Diabetes. Diabetes care. 2009;32 Suppl 2:S266-9.

- Said E, Farid S, Sabry N, Fawzi M. Comparison on efficacy and safety of three inpatient insulin regimens for management of non-critical patients with type 2 diabetes. Pharmacology & Pharmacy. 2013;4(07):556-65.

- Hanefeld M, Fleischmann H, Siegmund T, Seufert J. Rationale for timely insulin therapy in type 2 diabetes within the framework of individualised treatment: 2020 update. Diabetes Therapy. 2020;11(8):1645-66.

- Peyrot M, Rubin RR, Khunti K. Addressing barriers to initiation of insulin in patients with type 2 diabetes. Primary Care Diabetes. 2010;4:S11-S8.

- Perkovic V, Jardine MJ, Neal B, Bompoint S, Heerspink HJ, Charytan DM, et al. Canagliflozin and renal outcomes in type 2 diabetes and nephropathy. New England journal of medicine. 2019;380(24):2295-306.

- Zelniker TA, Braunwald E. Cardiac and renal effects of sodium-glucose co-transporter 2 inhibitors in diabetes: JACC state-of-the-art review. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 2018;72(15):1845-55.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).