Submitted:

24 July 2024

Posted:

25 July 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

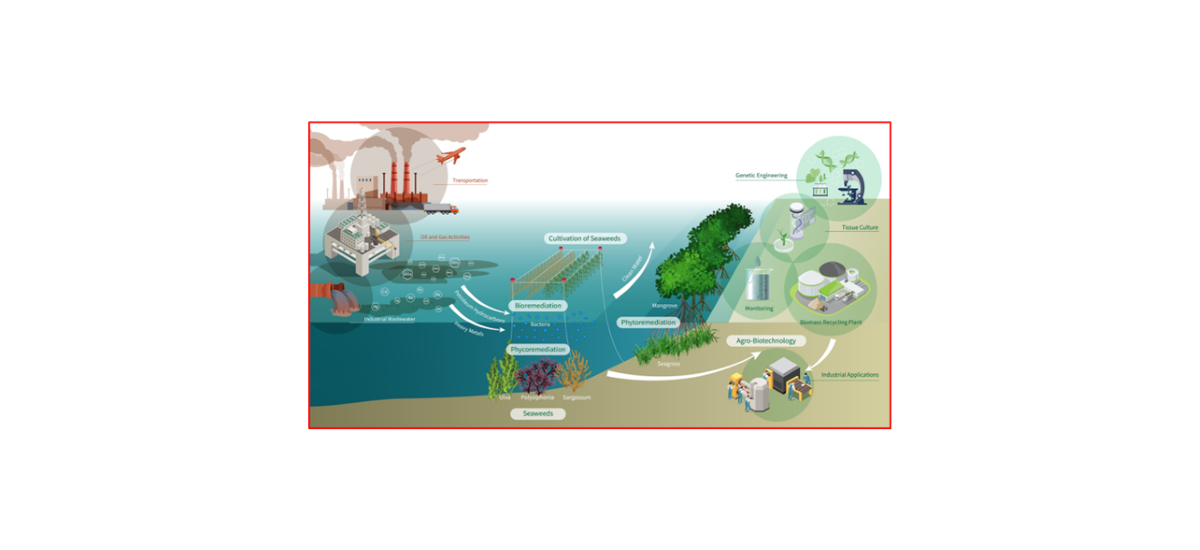

1. Introduction

1.1. Metabolic Reactions and Modern Biotechnology

1.2. Genetic Factors and Modern Biotechnology

2. Mangrove Plants and Associated Microorganisms

2.1. Phytoremediation

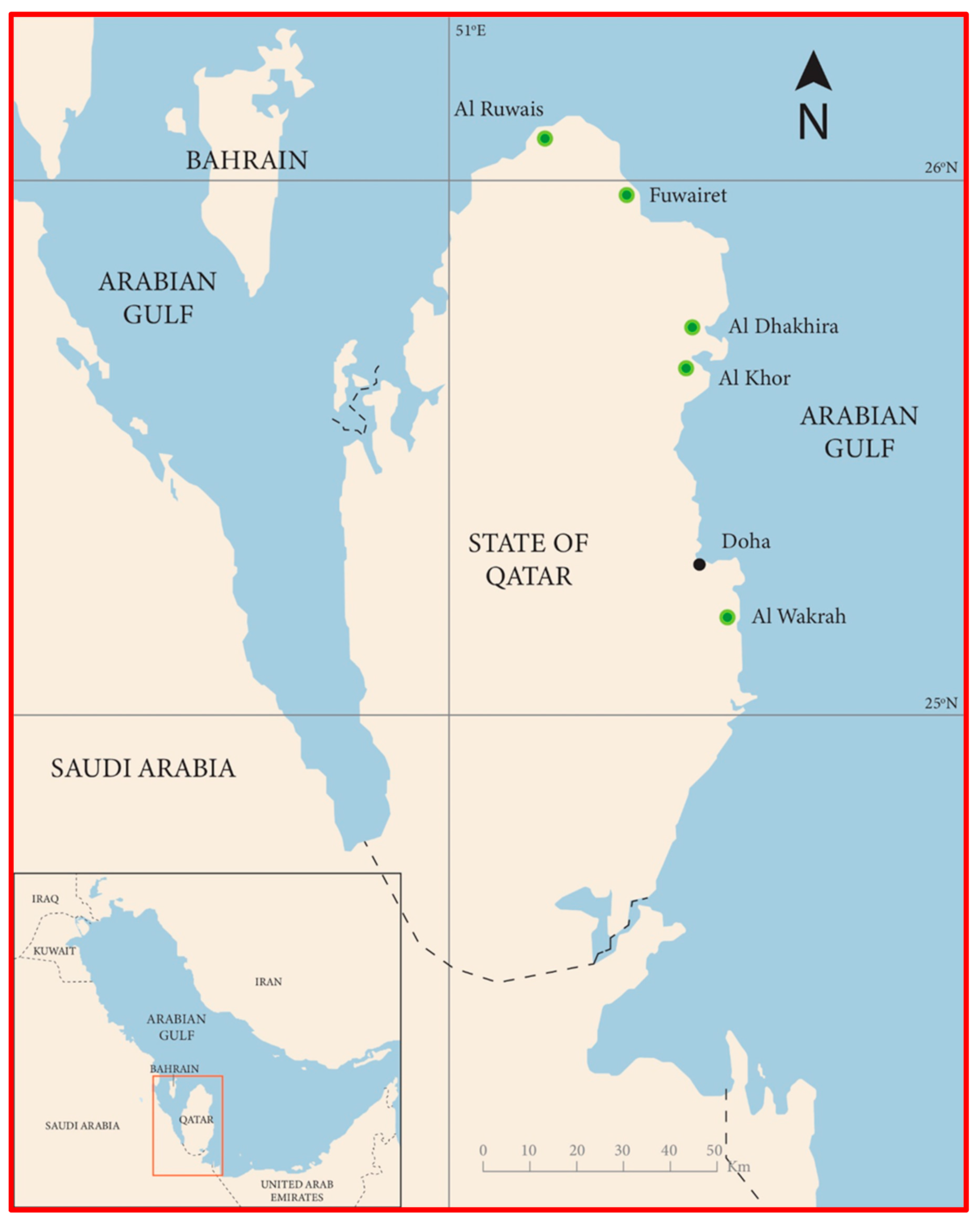

2.2. Perspectives of Cultivation of Mangroves in Qatar

3. Seagrasses

3.1. Halodule uninervis (Forssk.), Syn. Zostera uninervis Forssk

3.2. Halophila ovalis (R.Br.) Hook.f., Syn. Caulinia ovalis R. Br. (1810)

3.3. Thalassia hemprichii

4. Seaweeds

4.1. Chemical Constituents and Uses

4.2. Phycoremediation

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Acknowledgments

References

- Ghazanfar, S.A.; Böer, B.; Al Khulaidi, A.W.; El-Keblawy, A.; Alateeqi, S. Plants of Sabkha Ecosystems of the Arabian Peninsula. In Sabkha Ecosystems, Tasks for Vegetation Science; Gul, B., Böer, B., Khan, M., Clüsener-Godt, M., Hameed, A., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland; 2019; Volume 49, pp. 55–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Aken, B.; Correa, P.A.; Schnoor, J.L. Phytoremediation of polychlorinated biphenyls: new trends and promises. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2010, 44, 2767–2776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kamath, R.; Rentz, J.A.; Schnoor, J.L.; Alvarez, P.J.J. Phytoremediation of hydrocarbon-contaminated soils: principles and applications, Chapter 16. Studies in Surface Science and Catalysis 2004, 151, 447–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Ding, M.; Yuan, Y. Bioengineering for the Microbial Degradation of Petroleum Hydrocarbon Contaminants. Bioeng. 2023, 10, 347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alkorta, I.; Garbisu, C. Phytoremediation of organic contaminants in soils. Bioresour Technol. 2001, 79, 273–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vidali, M. Bioremediation. An overview. Pure Appl. Chem. 2001, 73, 1163–1172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Beilen, J.B.; Funhoff, E.G.; van Loon, A.; Just, A.; Kaysser, L.; Bouza, M.; Holtackers, R.; Rothlisberger, M.; Li, Z.; Witholt, B. Cytochrome P450 alkane hydroxylases of the CYP153 family are common in alkane-degrading eubacteria lacking integral membrane alkane hydroxylases. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2006, 72, 59–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ben Chekroun, K.; Sanchez, E.; Baghour, M. The role of algae in bioremediation of organic pollutants. Int. Res. J. Public Environ. Health 2014, 1, 19–32. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Thani, R.F.; Yasseen, B.T. Solutes in native plants in the Arabian Gulf region and the role of microorganisms: Future research. J. Plant Ecology 2018, 11, 671–684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Thani, R.F.; Yasseen, B.T. Phytoremediation of polluted soils and waters by native Qatari plants: Future perspectives. Environ. Pollut. 2020, 259, 113694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gkorezis, P.; Daghio, M.; Franzetti, A.; Van Hamme, J.D.; Sillen, W.; Vangronsveld, J. The interaction between plants and bacteria in the remediation of petroleum hydrocarbons: an environmental perspective. Front. Microbiol. 2016, 7, 1836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, X.; Kostka, J.E. Hydrocarbon-degrading microbial communities are site specific, and their activity is limited by synergies in temperature and nutrient availability in surface ocean waters. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2019, 85, e00443-19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, Q.; Kirk, M.F. pH as a primary control in environmental microbiology: 1. Thermodynamic perspective. Sec. Microbiol. Chem. & Geomicrobiol. 2018, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obahiagbon, K.O.; Amenaghawon, A.N.; Agbonghae, E.O. Effect of initial pH on the bioremediation of crude oil polluted water using a consortium of microbes. The Pacific J. Sci. & Technol. 2014, 15, 452–457. [Google Scholar]

- Li, H.; Lai, R.; Jin, Y.; Fang, X.; Cui, K.; Sun, S.; Gong, Y.; Li, H.; Zhang, Z.; Zhang, G.; Zhang, Z. Directional culture of petroleum hydrocarbon degrading bacteria for enhancing crude oil recovery. J. Hazard. Mater. 2020, 390, 122160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martirani-Von Abercron, S.; Marín, P.; Solsona-Ferraz, M.; Castañeda-Cataña, M.A.; Marqués, S. Naphthalene biodegradation under oxygen-limiting conditions: community dynamics and the relevance of biofilm-forming capacity. Microb. Biotechnol. 2017, 10, 1781–1796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bian, H.; Li, C.; Zhu, J.; Xu, L.; Li, M.; Zheng, S.; He, N. Soil moisture affects the rapid response of microbes to labile organic C addition. Front. Ecol. Evol. Sec. Biogeography & Macroecology 2022, 10, 857185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Thani, R.F.; Yasseen, B.T. Halo-Thermophilic bacteria, and heterocyst cyanobacteria found adjacent to halophytes at Sabkhas–Qatar: Preliminary study and possible roles. Afr. J. Microbiol. Res. 2017, 11, 1346–1354. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Thani, R.F.; Yasseen, B.T. Biological soil crusts and extremophiles adjacent to native plants at Sabkhas and Rawdahs, Qatar: The possible roles. Front. Environ. Microbiol. 2018, 4, 55–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Thani, R.F.; Yasseen, B.T. Perspectives of future water sources in Qatar by phytoremediation: Biodiversity at ponds and modern approach. Int. J. Phytoremediat. 2021, 23, 866–889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Thani, R.F.; Yasseen, B.T. Microbial ecology of Qatar, the Arabian Gulf: Possible roles of microorganisms. Front. Mar. Sci. 2021, 8, 697269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abou Khalil, C.; Prince, V.L.; Prince, R.C.; Greer, C.W.; Lee, K.; Zhang, B.; Michel, C.; Boufadel, M.C. Occurrence and biodegradation of hydrocarbons at high salinities. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 762, 143165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Teamkao, P.; Thiravetyan, P. Bioremediation of MEG, DEG, and TEG: potential of Burhead plant and soil microorganisms. World Academy of Science, Engineering and Technology International Journal of Biotechnology and Bioengineering. International Scholarly and Scientific Research & Innovation 2012, 6, 947–950. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Sulaiti, M.Y.; Al-Shaikh, I.M.; Yasseen, B.T.; Ashraf, S.; Hassan, H.M. Ability of Qatar’s native plant species to phytoremediate industrial wastewater in an engineered wetland treatment system for beneficial water reuse. Qatar Foundation Annual Research Forum Proceedings 2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Thani, R.F.; Yasseen, B.T. Possible future risks of pollution consequent to the expansion of oil and gas operations in Qatar. Environ. Pollut. 2023, 12, 12–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hutchinson, S.L.; Schwab, A.P.; Banks, M.K. Biodegradation of Petroleum Hydrocarbons in the Rhizosphere, Chapter 11. In Phytoremediation: Transformation and Control of Contaminants; McCutcheon, S.C., Schnoor, J.L., Eds.; 2003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eze, M.O.; Amuji, C.F. Elucidating the significant roles of root exudates in organic pollutant biotransformation within the rhizosphere. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 2359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kvesitadze, E.; Sadunishvili, T.; Kvesitadze, G. Mechanisms of organic contaminants uptake and degradation in plants. Int. J. Biomedic. & Biolog. Engin. 2009, 3, 361–371. [Google Scholar]

- Moe¨nne-Loccoz, Y.; Mavingui, P.; Combes, C.; Normand, P.; Steinberg, C. Microorganisms and Biotic Interactions, Chapter 11. In Environmental Microbiology: Fundamentals and Applications: Microbial Ecology; Bertrand, J.-C., et al., Eds.; 2015; (accessed on 21 April 2024). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhawi, F. The Role of plant growth-promoting microorganisms (PGPMs) and their feasibility in hydroponics and vertical farming. Metabolites 2023, 13, 247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- French, K.E. Engineering mycorrhizal symbioses to alter plant metabolism and improve crop health. Front. Microbiol. 2017, 8, 1403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hestrin, R.; Hammer, E.C.; Mueller, C.W.; Lehmann, J. Synergies between mycorrhizal fungi and soil microbial communities increase plant nitrogen acquisition. Commun. Biol. 2019, 2, 233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ratna, S.; Rastogi, S.; Kumar, R. Phytoremediation: A Synergistic Interaction Between Plants and Microbes for Removal of Unwanted Chemicals/Contaminants. In Microbes and Signaling Biomolecules Against Plant Stress; Springer: Singapore, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, N.; Chandran, P. Microbial degradation of petroleum hydrocarbon contaminants: an overview. Biotechnol. Res. Int. 2011, 2011, 941810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dave, S.; Das, J. Role of Microbial Enzymes for Biodegradation and Bioremediation of Environmental Pollutants: Challenges and Prospects. In Bioremediation for Environmental Sustainability; 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurzbaum, E.; Kirzhner, F.; Armon, R. A hydroponic system for growing gnotobiotic vs. sterile plants to study phytoremediation processes. Int. J. Phytoremediat. 2014, 16, 267–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kawasaki, A.; Okada, S.; Zhang, C.; Delhaize, E.; Mathesius, U.; Richardson, A.E.; Watt, M.; Gilliham, M.; Ryan, P.R. A sterile hydroponic system for characterizing root exudates from specific root types and whole-root systems of large crop plants. Plant Methods 2018, 14, 114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gogoi, B.; Das, I.; Begum, S.; Dutta, G.; Kumar, R.; Borah, D. Microbes and Their Genes Involved in Bioremediation of Petroleum Hydrocarbon. In Sustainable Materials: Bioremediation for Environmental Pollutants; Bentham Books; 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pal, S.; Kundu, A.; Banerjee, T.D.; Mohapatra, B.; Roy, A.; Manna, R.; Sar, P.; Kazy, S.K. Genome analysis of crude oil degrading Franconibacter pulveris strain DJ34 revealed its genetic basis for hydrocarbon degradation and survival in oil contaminated environment. Genomics 2017, 109, 374–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Thani, R.F.; Abd-El-Haleem, D.; Al-Shammri, M. Isolation, biochemical and molecular characterization of 2-chlorophenol degrading Bacillus isolates. Afric. J. Biotechnol. 2007, 6, 2675–2681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Thani, R.F.; Abd-El-Haleem, D.A.; Al-Shammri, M. Isolation and characterization of polyaromatic hydrocarbons-degrading bacteria from different Qatar soils. Afric. J. Micro. Res. 2009, 3, 761–766. [Google Scholar]

- Fotedar, R. Identification of Bacteria from the Marine Environment Surrounding Qatar. In Proceedings of the Qatar Foundation Annual Research Forum Proceedings; Hamad bin Khalifa University Press (HBKU Press): Ar Rayyan, 2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anand, A.; Zeyara, A.; Al-Malaki, A.; Al-Ghanim, M.M.; Hitha, P.K.; Taj-Aldeen, S.; Al-Marri, S.; Fotedar, R. Isolation and identification of potentially pathogenic vibrio species from Qatari coastal seawaters. In Proceedings of the Qatar Foundation Annual Research Conference Proceedings; Hamad bin Khalifa University Press (HBKU Press): Ar Rayyan, 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashfaq, M.Y.; Al-Ghouti, M.A.; Qiblawey, H.; Rodrigues, D.F.; Hu, Y.; Zouari, C. Isolation, identification, and biodiversity of antiscalant degrading seawater bacteria using MALDI-TOF-MS and multivariate analysis. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 656, 910–920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Catania, V.; Cappello, S.; Di Giorgi, V.; Santisi, S.; Di Maria, R.; Mazzola, A.; Vizzini, S.; Quatrini, P. Microbial communities of polluted sub-surface marine sediments. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2018, 131, 396–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hoshino, T.; Doi, H.; Uramoto, G.-I.; Wörmer, L.; Adhikari, R.R.; Xiao, N.; Morono, Y.; D’Hondt, S.; Hinrichs, K.-U.; Inagaki, F. Global diversity of microbial communities in marine sediment. PNAS 2020, 117, 27587–27597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhuang, J.; Zhang, R.; Zeng, Y.; Dai, T.; Ye, Z.; Gao, Q.; Yang, Y.; Guo, X.; Li, G.; Zhou, J. Petroleum pollution changes microbial diversity and network complexity of soil profile in an oil refinery. Fron. Microbiol. Terrestrial Microbiology 2023, 14, 1193189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.; Tang, J.; Bai, Z.; Hecker, M.; Giesy, J.P. Distribution of petroleum degrading genes and factor analysis of petroleum contaminated soil from the Dagang Oilfield. Sci. Rep. 2015, 5, 11068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Epstein, E.; Norlyn, J.D.; Rush, D.W.; Kingsbury, R.W.; Kelly, D.B.; Cummingham, G.A.; Wrona, A.F. Saline culture of crops: a genetic approach. Science 1980, 210, 399–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Svoboda, K.K.H.; Reenstra, W.R. Approaches to studying cellular signaling: a primer for morphologists. Anat. Rec. 2002, 269, 123–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Czako, M.; Feng, X.; He, Y.; Liang, D.; Marton, L. Genetic modification of wetland grasses for phytoremediation. Z. Naturforsch. C. J. Biosci. 2005, 60, 285–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hussain, M.S.; Fareed, S.; Ansari, S.; Rahman, M.A.; Ahmad, I.Z.; Saeed, M. Current approaches toward production of secondary plant metabolites. J. Pharm. Bioallied. Sci. 2012, 4, 10–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yasseen, B.T. Phytoremediation of Industrial Wastewater from Oil and Gas Fields using Native Plants: The Research Perspectives in the State of Qatar. Cent. Eur. J. Biol. 2014, 3, 6–23. [Google Scholar]

- Yan, A.; Wang, Y.; Tan, S.N.; Yusof, M.L.M.; Ghosh, S.; Chen, Z. Phytoremediation: A promising approach for revegetation of heavy metal-polluted land. Front. Plant Sci. 2020, 11, 359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-Khayat, J.A.; Balakrishnan, P. Avicennia marina around Qatar: Tree, seedling, and pneumatophore densities in natural and planted mangroves using remote sensing. Int. J. Sci. 2014, 3, 18–27. [Google Scholar]

- Karimi, Z.; Abdi, E.; Deljouei, A.; Cislaghi, A.; Shirvany, A.; Schwarz, M.; Hales, T.C. Vegetation-induced soil stabilization in coastal area: An example from a natural mangrove forest. CATENA 2022, 216, 106410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friis, G.; Killilea, M.E. Mangrove Ecosystems of the United Arab Emirates. In A Natural History of the Emirates; Burt, J.A., Ed.; Springer: Cham, 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farshid, Z.; Balef, R.M.; Zendehboudi, T.; Dehghan, N.; Mohajer, F.; Kalbi, S.; Hashemi, A.; Afshar, A.; Bafghi, T.H.; Baneshi, H.; Tamadon, A. Reforestation of grey mangroves (Avicennia marina) along the northern coasts of the Persian Gulf. Wetl. Ecol. Manag. 2023, 31, 115–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zouhaier, B.; Hussain, A.A.; Saleh, K. Traits allowing Avicennia marina propagules to overcome seawater salinity. Flora 2018, 242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akram, H.; Hussain, S.; Mazumdar, P.; Chua, K.O.; Butt, T.E.; Harikrishna, J.A. Mangrove Health: A review of functions, threats, and challenges associated with mangrove management practices. Forests 2023, 14, 1698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatting, M.; Al-Maslamani, I.; Walton, M.; Skov, M.W.; Kennedy, H.; Husrevooglu, Y.S.; Vay, L.L. Future mangrove carbon storage under climate change and deforestation. Front. Mar. Sci. 2022, 9, 781876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asari, N.; Suratman, M.N.; Ayob, N.A.M.; Abul Hamid, N.H. Mangrove as a Natural Barrier to Environmental Risks and Coastal Protection. Mangroves: Ecology, Biodiversity, and Management 2021, 13, 305–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rizk, A.M. The Phytochemistry of the Flora of Qatar; Scientific and Applied Research Centre, University of Qatar: Kingprint, Richmond, U.K., 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Mossa, J.S.; Al-Yahya, M.A.; Al-Meshal, I.A. Medicinal Plants in Sudi Arabia; King Saud University Libraries: Riyadh, Saudi Arabia, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Rizk, A.M.; El-Ghazaly, A. Medicinal and Poisonous Plants of Qatar; Scientific and Applied Research Centre, University of Qatar: P.O. Box 2713, Doha, Qatar, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Kafle, A.; Timilsina, A.; Gautam, A.; Adhikari, K.; Bhattarai, A.; Aryal, N. Phytoremediation: Mechanisms, plant selection and enhancement by natural and synthetic agents. Env. Adv. 2022, 8, 100203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Usman, K.; Al-Ghouti, M.A.; Abu-Dieyeh, M.H. The assessment of cadmium, chromium, copper, and nickel tolerance and bioaccumulation by shrub plant Tetraena qataranse. Sci. Rep. 2019, 5658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yasseen, B.T.; Al-Thani, R.F. Endophytes and halophytes to remediate industrial wastewater and saline soils: Perspectives from Qatar. Plants 2022, 11, 1497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moreira, I.T.A.; de Oliveira, O.M.C.; Triguis, J.A.; Queiroz, A.; Ferreira, S.L.C.; Martins, C.M.S.; Silva, A.C.M.; Falcão, B.A. Phytoremediation in mangrove sediments impacted by persistent total petroleum hydrocarbons (TPH's) using Avicennia schaueriana. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2012, 67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivorra, L.; Cardoso, P.G.; Chan, S.K.; Cruzeiro, C.; Tagulao, K.A. Can mangroves work as an effective phytoremediation tool for pesticide contamination? An interlinked analysis between surface water, sediments, and biota. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 295, 126334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, S.; Peng, T.; Pratush, A.; Huang, T.; Hu, Z. Interactions between heavy metals and bacteria in mangroves. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2021, 172, 112846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdel Bari, E.M.; Yasseen, B.T.; Al-Thani, R.F. Halophytes in the State of Qatar; Qatar University (Sponsered by Environmental Studies Centre), 2007; ISBN 99921-52-98-2. [Google Scholar]

- Moreira, I.T.A.; Oliveira, O.M.C.; Triguis, J.A.; Queiroz, A.F.S.; Ferreira, S.L.C.; Martins, C.M.S.; Silva, A.C.M.; Falcão, B.A. Phytoremediation in mangrove sediments impacted by persistent total petroleum hydrocarbons (TPH’s) using Avicennia schaueriana. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2013, 67, 130–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moradi, B.; Maivan, H.Z.; Hashtroudi, M.S.; Sorahinobar, M.; Rohloff, J. Physiological responses and phytoremediation capability of Avicennia marina to oil contamination. Acta Physiol. Plant. 2021, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Araji, S.; Theresa, A.; Grammer, T.A.; Gertzen, R.; Anderson, S.D.; Mikulic-Petkovsek, M.; Veberic, R.; Phu, My.L.; Solar, A.; Leslie, C.A.; Dandekar, A.M.; Escobar, M.A. Novel roles for the polyphenol oxidase enzyme in secondary metabolism and the regulation of cell death in Walnut. Plant Physiol. 2014, 164, 1191–1203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Mello-Farias, P.C.; Chaves, A.L.S.; Lencina, C.L. Transgenic Plants for Enhanced Phytoremediation-Physiological Studies, Chapter 16. In Genetic Transformation; Alvarez, M., Ed.; Intech Open, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Mahadik, S.; Ghosh, S.; Banerjee, S. Mangroves as potential agents of phytoremediation: A review. Res. J. Chem. Environ. 2022, 26, 138–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jadia, C.D.; Fulekar, M.H. Phytoremediation of heavy metals: Recent technique. Afr. J. Biotechnol. 2009, 8, 921–928, ISSN 1685-5315. http://www.academicjournals.org/AJB.

- Yuliasni, R.; Kurniawan, S.B.; Marlena, B.; Hidayat, M.R.; Kadier, A.; Ma, P.C.; Imron, M.F. Recent progress of phytoremediation-based technologies for industrial wastewater treatment. J. Ecol. Eng. 2023, 24, 208–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varjani, S.J. Microbial degradation of petroleum hydrocarbons. Bioresour. Technol. 2017, 223, 277–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reichenauer, T.G.; Germida, J.J. Phytoremediation of organic contaminants in soil and groundwater. Chem. Sus. Chem. 2008, 1, 708–817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carvalho, K.M.; Martin, D.F. Removal of aqueous selenium by four aquatic plants. J. Aquat. Plant Manage. 2001, 39, 33–36. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, S.; Wang, Y.; Yu, L.; Oakey, J. Volatilization of mercury, arsenic and selenium during underground coal gasification. Fuel 2006, 85, 1550–1558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pang, Y.L.; Quek, Y.Y.; Lim, S.; Shuit, S.H. Review on phytoremediation potential of floating aquatic plants for heavy metals: A promising approach. Sustainability 2023, 15, 1290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almahasheer, H. Spatial coverage of mangrove communities in the Arabian Gulf. Environ. Monit. Assess. 2018, 190, 85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yasseen, B.T.; Al-Thani, R.F. Ecophysiology of Wild Plants and Conservation Perspectives in the State of Qatar, Chapter 3. In Agricultural Chemistry; Stoytcheva, M., Zlatev, R., Eds.; InTech, 2013; pp. 37–70. ISBN 978-953-51-1026-2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Khayat, J.A.; Abdulla, M.A.; Alatalo, J.M. Diversity of benthic macrofauna and physical parameters of sediments in natural mangroves and in afforested mangroves three decades after compensatory planting. Aquat. Sci. 2019, 81, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Khayat, J.A.; Vethamony, P.; Nanajkar, M. Molluscan diversity influenced by mangrove habitat in the Khors of Qatar. Wetlands 2021, 41, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yasseen, B.T.; Abu-Al-Basal, M.A. Ecophysiology of Limonium axillare and Avicennia marina from the Coastline of Arabian Gulf-Qatar. J. Coast. Conserv. 2008, 12, 35–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Naimi, N.; Al-Ghouti, M.A.; Balakrishnan, P. Investigating chlorophyll and nitrogen levels of mangroves at Al-Khor, Qatar: an integrated chemical analysis and remote sensing approach. Environ. Monit. Assess. 2016, 188, 268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Larcher, W. Physiological Plant Ecology, Ecophysiology and Stress Physiology of Functional Groups, 4th ed.; Springer: Berlin, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Jian, Z.; Huang, D.; Fang, Y.; Cui, L.; Zhao, C.; Liu, S.; Wu, Y.; Chen, Q.; Ranvilage, C.I.P.M.; He, J.; Huang, X. Home for marine species: seagrass leaves as vital spawning grounds and food source. Front. Mar. Sci. 2020, 7, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, G.; Suonan, Z.; Kim, S.H.; Hwang, D.-W.; Lee, K.-S. Heavy metal accumulation and phytoremediation potential by transplants of the seagrass Zostera marina in the polluted bay systems. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2019, 149, 110509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- James, R.K.; Lynch, A.; Herman, P.M.J.; van Katwijk, M.M.; van Tussenbroek, B.I.; Dijkstra, H.A.; van Westen, R.M.; der Boog, C.G.; Klees, R.; Slobbe, C.; Bouma, T.J. Tropical biogeomorphic seagrass landscapes for coastal protection: persistence and wave attenuation during major storms events. Ecosystems 2021, 24, 301–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montero-Hidalgo, M.; Tuya, F.; Otero-Ferrer, F.; Haroun, R.; Santos-Martín, F. Mapping and assessing seagrass meadows changes and blue carbon under past, current, and future scenarios. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 872, 162244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ganguly, D.; Singh, G.; Ramachandran, P.; Selvam, A.P.; Banerjee, K.; Ramachandran, R. Seagrass metabolism and carbon dynamics in a tropical coastal embayment. Ambio. 2017, 46, 667–679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bu-Olayan, A.H.; Thomas, B.V. Accumulation, and translocation of trace metals in Halodule uninervis, in the Kuwait coast. Biosci. Biotechnol. Res. Asia 2010, 7, 25–32. [Google Scholar]

- Durako, M.J.; Kenworthy, W.J.; Fatemy, S.M.R.; Valavi, H.; Thayer, G.W. Assessment of the toxicity of Kuwait crude oil on the photosynthesis and respiration of seagrasses of the northern Gulf. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 1993, 27, 223–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalafallah, A.A.; Geneid, Y.A.; Shaetaey, S.A.; Shaaban, B. Responses of the seagrass Halodule uninervis (Forssk.) Aschers. to hypersaline conditions. Egypt. J. Aquat. Res. 2013, 39, 167–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Arbash, A.; Al-Bader, D.; Suleman, P. Structural and biochemical responses of the seagrass Halodule uninervis to changes in salinity in Kuwait Bay, Doha area. Kuwait J. Sci. 2016, 43, 131–142. [Google Scholar]

- Akinpelu, A.A.; Nazal, M.K.; Abuzaid, N. Adsorptive removal of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons from contaminated water by biomass from dead leaves of Halodule uninervis: kinetic and thermodynamic studies. Biomass Convers. Biorefin. 2023, 13, 8301–8313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ralph, P.J.; Burchett, M.D. Impact of petrochemicals on the photosynthesis of Halophila ovalis using chlorophyll fluorescence. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 1998, 36, 429–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ralph, P.J.; Burchett, M.D. Photosynthetic response of Halophila ovalis to heavy metal stress. Environ. Pollut. 1998, 103, 91–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, S.; Lal, M.M.; Southgate, P.C.; Wairiu, M.; Singh, A. Trace metal content in sediment cores and seagrass biomass from a tropical southwest Pacific Island. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2021, 171, 112745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ralph, P.J. Herbicide toxicity of Halophila ovalis assessed by chlorophyll a fluorescence. Aquat. Bot. 2000, 66, 141–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Runcie, J.; Macinnis-Ng, C.; Ralph, P. The Toxic Effects of Petrochemicals on Seagrasses: Literature Review. Report Prepared by Institute for Water and Environmental Resource Management and Department of Environmental Sciences University of Technology, Sydney, for Australian Maritime Safety Authority, Canberra; 2005; (accessed on 7 June 2024). [Google Scholar]

- Tupan, C.I.; Uneputty, P.A. Concentration of heavy metals lead (Pb) and cadmium (Cd) in water, sediment, and seagrass Thalassia hemprichii in Ambon Island waters. AACL Bioflux 2017, 10, 1610–1617. [Google Scholar]

- McKenzie, L.J.; Yoshida, R.L.; Aini, J.W.; Andréfouet, S.; Colin, P.L.; Cullen-Unsworth, L.C.; Hughes, A.T.; Payri, C.E.; Rota, M.; Shaw, C.; Tsuda, R.T.; Vuki, V.C.; Unsworth, R.K.F. Seagrass ecosystem contributions to people's quality of life in the Pacific Island Countries and Territories. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2021, 167, 112307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yasseen, B.T. Physiology of Water Stress in Plants; University of Mosul: Mosul, Iraq, Arabic, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Yasseen, B.T.; Al-Thani, R.F.; Alhadi, F.A.; Abbas, R.A.A. Soluble sugars in plants under stress at the Arabian Gulf region: Possible roles of microorganisms. J. Plant Biochem. Physiol. 2018, 6, 224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nazal, M.K.; Ditta, M.; Rao, G.D.; Abuzaid, N.S. Treatment of water contaminated with petroleum hydrocarbons using a biochar derived from seagrass biomass as low-cost adsorbent: isotherm, kinetics, and reusability studies. Sep. Sci. & Technol. 2022, 57, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilding, C.; Tillin, H.; Stewart, E.J.; Lubelski, A.; Burrows, M.; Smale, D. Hand Harvesting of Seaweed: Evidence Review to Support Sustainable Management; NRW Evidence Report Series Report No: 573; NRW: Bangor, 2021; 275p. [Google Scholar]

- Available online: https://www.mba.ac.uk/wp-content/uploads/2022/05/Wilding_et_al_2021_NRW_Hand-harvesting-seaweed.pdf (accessed on 20 March 2024).

- Al-Homaidan, A.A.; Al-Ghanayem, A.A.; Al-Qahtani, H.S.; Alabbad, A.; Alabdullatif, J.A.; Alwakeel, S.; Ameen, F. Effect of sampling time on the heavy metal concentrations of brown algae: A bioindicator study on the Arabian Gulf coast. Chemosphere 2021, 263, 127998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ameen, F.; Al-Homaidan, A.A.; Al-Mahasheer, H.; Dawoud, T.; Al-Wakeel, S.; Al-Maarofi, S. Biomonitoring coastal pollution on the Arabian Gulf and the Gulf of Aden using macroalgae: A review. Mar. Pollut. Bulletin. 2022, 175, 113156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lourenço-Lopes, C.; Garcia-Oliveira, P.; Carpena, M.; Fraga-Corral, M.; Jimenez-Lopez, C.; Pereira, A.G.; Prieto, M.A.; Simal-Gandara, J. Scientific approaches on extraction, purification and stability for the commercialization of fucoxanthin recovered from brown algae. Foods 2020, 9, 1113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choudhary, P.; Subhash, G.V.; Khade, M.; Savant, S.; Musale, A.; Kumar, G.R.K.; Chelliah, M.S.; Dasgupta, S. Empowering blue economy: From underrated ecosystem to sustainable industry. J. Environ. Mang. 2021, 291, 112697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rizk, A.M.; Al-Easa, H.S.; Kornprobst, J.M. The Phytochemistry of the Macro and Blue-Green Algae of the Arabian Gulf; Faculty of Science: P.O. Box 2713, Doha, Qatar, Printed and bound in Qatar at the Doha Modern Printing Press Ltd.; 1999; ISBN 999921-46-64-8. [Google Scholar]

- Koul, B.; Sharma, K.; Shah, M.P. Phycoremediation: A sustainable alternative in wastewater treatment (WWT) regime. Environ. Technol. Inno. 2022, 25, 102040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogundele, O.D.; Adewumi, A.J.; Oyegoke, D.A. Phycoremediation: Algae as an effective agent for sustainable remediation and waste water treatment. EESRJ 2023, 10, 7–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ankit; Bauddh, K.; Korstad, J. Phycoremediation: Use of algae to sequester heavy metals. Hydrobiol. 2022, 1, 288–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, A.; Ponmani, S.; Sharma, G.K.; Sangavi, P.; Chaturvedi, A.K.; Singh, A.; Malyan, S.K.; Kumar, A.; Khan, S.A.; Shabnam, A.A.; Jigyasu, D.K.; Gull, A. Plummeting toxic contaminates from water through phycoremediation: Mechanism, influencing factors and outlook to enhance the capacity of living and non-living algae. Environ. Res. 2023, 239, 117381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heiba, H.I.; Dorgham, M.M.; Al-Nagdy, S.A.; Rizk, A.M. Phytochemical studies on the marine algae of Qatar, Arabian Gulf. Qatar Univ. Sci. Bull. 1990, 10, 99–113, Cited by Rizk et al. 1999 (Ref. 118). [Google Scholar]

- Garcia, E.M.; Reyes Gil, R.E. Bioconcentration of Hg in Acetabularia caliculus: Evidence of a polypeptide in whole cells and anucleated cells. Toxicol. Environ. Chem. 1996, 55, 11–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freije, A.M. Heavy metal, trace element and petroleum hydrocarbon pollution in the Arabian Gulf: Review. J. Assoc. Arab Univ. Basic Appl. Sci. 2015, 17, 90–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henriques, B.; Rocha, L.S.; Lopes, C.B.; Figueira, P.; da Costa Duarte, A.; Garcia do Vale CAPardal, M.A.; Pereira, E. A macroalgae-based biotechnology for water remediation: Simultaneous removal of Cd, Pb and Hg by living Ulva lactuca. J. Environ. Manag. 2017, 191, 275–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hawas, U.W.; Abou El-Kassem, L.T.; Al-Farawati, R.; Shaher, F.M. Halo-phenolic metabolites and their in vitro antioxidant and cytotoxic activities from the Red Sea alga Avrainvillea amadelpha. Z. Naturforsch C. J. Biosci. 2021, 76, 213–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prasada Rao, N.V.S.A.V.; Sastry, K.V.; Venkata, R.K. Studies on Indian seaweed polysaccharides, Part 1. Isolation and characterization of the sulphated polysaccharides of Spongomorpha indica and Boodlea struveoides. Indian J. Pharm. Sci. 1982, 44, 144–146, Cited by Rizk et al. 1999 (Ref. 118). [Google Scholar]

- Hori, H.; Miyazawa, K.; Ito, K. Isolation and characterization of polyconjugate-specific isoagglutinins from a marine green algae Boodlea coacta (Dickie) Murray et De Toni. Bot. Mar. 1986, 29, 323–328, Cited by Rizk et al. 1999 (Ref. 118). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mshigeni, K.E.; Durgham, M.M. Benthic Marine Algae of Qatar: A Preliminary Survey; UNESCO Regional Office Report; Doha, Qatar, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Praveen, P.J.; Singh, K.; Naik, B.G.; Parameswaran, P.S. Phytochemical studies of marine green algae Boodlea composita from Ukha, west coast of India. J. Indian Chem. Soc. 2017, 94, 637–640. [Google Scholar]

- Koul, B.; Sharma, K.; Shah, M.P. Phycoremediation: A sustainable alternative in wastewater treatment (WWT) regime. Environ. Technol. & Inno. 2022, 25, 102040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.; Kim, H.T.; Jung, S.H.; Han, J.W.; Jo, S.; Kim, I.G.; Kim, R.K.; Kahm, Y.J.; Choi, T.I.; Kim, C.H.; Lee, J.H. A Novel anticancer peptide derived from Bryopsis plumosa regulates proliferation and invasion in non-small cell lung cancer cells. Mar. Drugs 2023, 21, 607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rushdi, M.I.; Abdel-Rahman, I.A.M.; Attia, E.Z.; Abdelraheem, W.M.; Saber, H.; Madkour, H.A.; Amin, E.; Hassan, H.M.; Abdelmohsen, U.R. A review on the diversity, chemical and pharmacological potential of the green algae genus Caulerpa. South Afr. J. Bot. 2020, 132, 226–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landi, S.; Santini, G.; Vitale, E.; Di Natale, G.; Maisto, G.; Arena, C.; Esposito, S. Photosynthetic, molecular, and ultrastructural characterization of toxic effects of zinc in Caulerpa racemosa indicate promising bioremediation potentiality. Plants 2022, 11, 2868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Caronni, S.; Quaglini, L.A.; Franzetti, A.; Gentili, R.; Montagnani, C.; Citterio, S. Does Caulerpa prolifera with its bacterial coating represent a promising association for seawater phytoremediation of diesel hydrocarbons? Plants 2023, 12, 2507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bohnic, P.; Korbar-Samid, J.; Sedej, A. Saponins in the sea lettuces (Ulvaceae). Farm. Vestn. (Ljubljana) 1973, 24, 125–129, Cited by Rizk et al. 1999 (Ref. 118). [Google Scholar]

- Shun, M.; Kasuyuki, W. Gas chromatographic analysis of cell/wall polysaccharides in certain siphonocladalean and cladophoralean algae. Rep. Usa Mar. Biol. Inst. Karachi Univ. 1985, 7, 9–14, Cited by Rizk et al. 1999 (Ref. 118). [Google Scholar]

- Williams, J.O.; Ntorn, Q. Remediation of a crude oil polluted river in B-Dere in orgonila and rivers State using Chaetomorpha and Nostoc species. IOSR J. Environ. Sci. Toxicol. & Food Technol. 2019, 13, Ser. 1, 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Aquilino, F.; Paradiso, A.; Trani, R.; Longo, C.; Pierri, C.; Corriero, G.; de Pinto, M.C. Chaetomorpha linum in the bioremediation of aquaculture wastewater: Optimization of nutrient removal efficiency at the laboratory scale. Aquaculture 2020, 523, 735133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alsafran, M.; Saleem, M.H.; Al Jabri, H.; Rizwan, M.; Usman, K. Principles and Applicability of Integrated Remediation Strategies for Heavy Metal Removal/Recovery from Contaminated Environments. J. Plant Growth Regul. 2023, 42, 3419–3440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chmielewská, E.; Medved, J. Bioaccumulation of heavy metals by green algae Cladophora glomerata in a refinery sewage lagoon. Croatica Chemica Acta 2001, 74, 135–145. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, Y.-C.; Chang, S.-P. The biosorption of heavy metals from aqueous solution by Spirogyra and Cladophora filamentous macroalgae. Bioresour. Technol. 2011, 102, 5297–5304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Michalak, I.; Messyasz, B. Concise review of Cladophora spp.: Macroalgae of commercial interest. J. Appl. Phycol. 2021, 33, 133–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ross, M.E.; Stanley, M.S.; Day, J.G.; Semião, A.J.C. Removal of metals from aqueous solutions using dried Cladophora parriaudii of varying biochemical composition. J. Environ. Manag. 2021, 290, 112620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khan, S.; Ullah, A.; Ayaz, T.; Aziz, A.; Aman, K.; Habib, M.; Yilmaz, S.; Farid, A.; Yasmin, H.; Ali, Q. Phycoremediation of industrial wastewater using Vaucheria debaryana and Cladophora glomerata. Environ. Monit. Assess. 2023, 195, 825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- El-Beltagi, H.S.; Mohamed, A.A.; Mohamed, H.I.; Ramadan, K.M.A.; Barqawi, A.A.; Mansour, A.T. Phytochemical and potential properties of seaweeds and their recent applications: A review. Mar. Drugs 2022, 20, 342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tarfeen, N.; Ul Nisa, K.; Hamid, B.; Bashir, Z.; Yatoo, A.M.; Ashraf Dar, M.; Mohiddin, F.A.; Amin, Z.; Ahmad, R.A.; Sayyed, R.Z. Microbial remediation: A promising tool for reclamation of contaminated sites with special emphasis on heavy metal and pesticide pollution: A review. Processes 2022, 10, 1358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalaf, F.I.; Gab-Alla, A.A.-F.; Ahmed, A.I. Ecological study of the impact of oil pollution on the fringing reef of Ras Shukeir, Gulf of Suez, Red Sea, Egypt. Egypt. J. Biol. 2002, 4, 119–126. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Shwafi, N.A.; Rushdi, A.I. Heavy metal concentrations in marine green, brown, and red seaweeds from coastal waters of Yemen, the Gulf of Aden. Environ. Earth Sci. 2008, 55, 653–660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mearns, A.J.; Reish, D.J.; Oshida, P.S.; Morrison, A.M.; Rempel-Hester, M.A.; Arthur, C.; Rutherford, N.; Pryor, R. Effects of pollution on marine organisms. Water Environ. Res. 2016, 88, 1693–1807. https://www.jstor.org/stable/26662431. [CrossRef]

- Jacques, N.R.; McMartin, D.W. Evaluation of algal phytoremediation of light extractable petroleum hydrocarbons in subarctic climates. Remediation J. 2009, 20, 119–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ben Chekroun, K.; Baghour, M. The role of algae in phytoremediation of heavy metals: A review. J. Mater. Environ. Sci. 2013, 4, 873–880, ISSN: 2028-2508 CODEN: JMESCN 873. [Google Scholar]

- Baghour, M. Effect of seaweeds in phyto-remediation, Chapter Book. In Biotechnological Applications of Seaweeds; 2017; pp. 47–83. ISBN 978-1-53610-968-9. [Google Scholar]

- Agarwal, S.; Albeshr, M.F.; Mahboobb, S.; Atique, U.; Pramanick, P.; Mitra, A. Bioaccumulation factor (BAF) of heavy metals in green seaweed to assess the phytoremediation potential. J. King Saud Univ. Sci. 2022, 34, 102078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danouche, M.; El Ghachtouli, N.; El Arroussi, H. Phycoremediation mechanisms of heavy metals using living green microalgae: physicochemical and molecular approaches for enhancing selectivity and removal capacity. Heliyon 2021, 7, e07609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krupina, M.V. Use of Cystoseira and Ulva macrophytes for monitoring marine pollution by heavy metals. Deposited Doc. VINITI 1981, 5484-81, 33–34, Cited by Rizk et al. 1999 (ref. 118).. [Google Scholar]

- Areco, M.M.; Salomone, V.N.; Afonso, M.S. Ulva lactuca: A bioindicator for anthropogenic contamination and its environmental remediation capacity. Mar. Environ. Res. 2021, 171, 105468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Akl, F.M.A.; Ahmed, S.I.; El-Sheekh, M.M.; Mofida, E.M.; Makhlof, M.E.M. Bioremediation of n-alkanes, polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons, and heavy metals from wastewater using seaweeds. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2023, 30, 104814–104832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- El-Mahrouk, M.E.; Dewir, Y.H.; Hafez, Y.M.; El-Banna, A.; Moghanm, F.S.; El-Ramady, H.; Mahmood, Q.; Elbehiry, F.; Brevik, E.C. Assessment of bioaccumulation of heavy metals and their ecological risk in sea lettuce (Ulva spp.) along the coast Alexandria, Egypt: Implications for sustainable management. Sustainability 2023, 15, 4404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dadolahi-Sohrab, A.; Nikvarz, A.; Nabavi, S.M.B.; Safahieh, A.; Mohseni, M.K. Environmental monitoring of heavy metals in seaweed and associated sediment from the Strait of Hormuz, I.R. Iran. World J. Fish & Mar. Sci. 2011, 3, 576–589. [Google Scholar]

- El Asri, O.; Ramdani, M.; Latrach, L.; Haloui, B.; Ramdani, M.; Afilal, M.E. Comparison of energy recovery after anaerobic digestion of three Marchica lagoon algae (Caulerpa prolifera, Colpomenia sinuosa, Gracilaria bursa-pastoris). Sustain. Mater. Techno. 2017, 11, 47–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alprol, A.E.; Mansour, A.T.; Abdelwahab, A.M.; Ashour, M. Advances in green synthesis of metal oxide nanoparticles by marine algae for wastewater treatment by adsorption and photocatalysis techniques. Catalysts 2023, 13, 888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blanco-Vieites, M.; Suárez-Montes, D.; Delgado, F.; Álvarez-Gil, M.; Hernández Battez, A.; Rodríguez, E. Removal of heavy metals and hydrocarbons by microalgae from wastewater in the steel industry. Algal Res. 2022, 64, 102700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kravtsova, A.; Milchakova, N.; Frontasyeva, M. Elemental accumulation in the black sea brown algae Cystoseira studied by neutron activation analysis. Ecological Chemistry and Engineering S 2014, 21, 9–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koshlaf, E.; Ball, A.S. Soil bioremediation approaches for petroleum hydrocarbon polluted environments. AIMS Microbiol. 2017, 3, 25–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, G.S.; Yadav, G.; Tiwari, S. Bioremediation of heavy metals: A new approach to sustainable agriculture. Restoration of wetland ecosystem. In Restoration of Wetland Ecosystem: A Trajectory Towards a Sustainable Environment; 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdullahi, U.; Khandaker, M.M.; Alias, N.; Shaari, E.M.; Alam, M.A.; Badaluddin, N.A.; Mohd, K.S. Sea weed effects on plant growth and environmental remediation: A review. J. Phytol. 2021, 13, 6903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahhou, A.; Layachi, M.; Akodad, M.; El-Ouamari, N.; Aknaf, A.; Skalli, A.; Oudra, B.; Kolar, M.; Imperl, J.; Petrova, P.; Baghour, M. Analysis and health risk assessment of heavy metals in four common seaweeds of Marchica lagoon (a restored lagoon, Moroccan Mediterranean). Arabian J. Chem. 2023, 16, 105281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Homaidan, A.A.; Al-Ghanayem, A.A.; Al-Qahtani, H.S.; Ameen, F. Effect of sampling time on the heavy metal concentrations of brown algae: A bioindicator study on the Arabian Gulf coast. Chemosphere 2020, 263, 127998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahmed, H.; Heneidak, S.; El Shoubaky, G.A.; Rasmey, A.-H.M. In vitro comparative antimicrobial potential of bioactive crude and fatty acids extracted from abundant marine macroalgae, Egypt. Front. Sci. Res. Technol. 2023, 7, 11–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osman, N.A.H.K.; Abd-Elazeem, O.M.; Al-Eisa, R.A.; El-Shenawy, N.S. Anticancer and antimicrobial evaluation of extract from brown algae Hormophysa cuneiformis. J. Appl. Biomed. 2023, 21, 121–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Engdahl, S.; Mamboya, F.; Mtolera, M.; Semesi, A.K.; Björk, M. The brown macroalga Padina boergesenii as an indicator of heavy metal contamination in the Zanzibar channel. AMBIO 1998, 27, 694–700. [Google Scholar]

- Mantiri, D.M.H.; Kepel, R.C.; Manoppo, H.; Paulus, J.J.H.; Nasprianto, D.S.P. Metals in seawater, sediment and Padina australis (Hauck, 1887) algae in the waters of North Sulawesi. AACL Bioflux 2019, 12, 840–851. http://www.bioflux.com.ro/aacl.

- Foday, E.H., Jr.; Bo, B.; Xiaohui, X. Removal of toxic heavy metals from contaminated aqueous solutions using seaweeds: A review. Sustainability 2021, 13, 12311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samar, J.; Butt, G.Y.; Shah, A.A.; Shah, A.N.; Ali, S.; Jan, B.L.; Abdelsalam, N.R.; Hussaan, M. Phycochemical and biological activities from different extracts of Padina antillarum (Kützing) Piccone. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 929368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vijayaraghavan, K.; Teo, T.T.; Balasubramanian, R.; Joshi, U.M. Application of Sargassum biomass to remove heavy metal ions from synthetic multi-metal solutions and urban storm water runoff. J. Hazard. Mater. 2009, 164, 1019–1023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar, M.; Aparna Seth, A.; Singh, A.K.; Rajput, M.S.; Mohd Sikandar, M. Remediation strategies for heavy metals contaminated ecosystem: A review. Environ. Sustain. Ind. 2021, 12, 100155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández, L.A.G.; Frometa, A.E.N.; Alvarez, C.C.; Ramirez, R.F.; Flores, P.E.D.; Ramos, V.C.; Polo, M.S.; Martin, F.C.; Castillo, N.A.M. Valorization of Sargassum Biomass as Potential Material for the Remediation of Heavy-Metals-Contaminated Waters. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 2559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rangabhashiyam, S.; Vijayaraghavan, K. Biosorption of Tm (III) by free and polysulfone-immobilized Turbinaria conoides biomass. J. Ind. Eng. Chem. 2019, 80, 318–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukherjee, A.; Sarkar, D.; Sasmal, S. A review of green synthesis of metal nanoparticles using algae. Front. Microbiol. 2021, 12, 693899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elhady, S.S.; Habib, E.S.; Abdelhameed, R.F.A.; Goda, M.S.; Hazem, R.M.; Mehanna, E.T.; Helal, M.A.; Hosny, K.M.; Diri, R.M.; Hassanean, H.A.; Ibrahim, A.K.; Eltamany, E.E.; Abdelmohsen, U.R.; Ahmed, S.A. Anticancer effects of new Ceramides isolated from the Red Sea, red algae Hypnea musciformis in a model of ehrlich ascites carcinoma: LC-HRMS analysis profile and molecular modeling. Mar. Drugs 2022, 20, 63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, P.K.; Ranjan, S.; Gupta, S.K. Phycoremediation of petroleum hydrocarbon-polluted sites: Application, challenges, and future prospects. In Application of Microalgae in Wastewater Treatment; Springer, 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jimenez-Lopez, C.; Pereira, A.G.; Lourenço-Lopes, C.; Garcia-Oliveira, P.; Cassani, L.; Fraga-Corral, M.; Prieto, M.A.; Simal-Gandara, J. Main bioactive phenolic compounds in marine algae and their mechanisms of action supporting potential health benefits. Food Chem. 2021, 341, 128262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murphy, C. An Investigation into the Bioaccumulation of Chromium by Macroalgae. Ph.D. Thesis, Waterford Institute of Technology, Ireland, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Augier, H.; Gilles, G.; Ramonda, G. The benthic red alga Ceramium ciliatum var. robustum (J.Ag.) G. Mazoyer is a remarkable biological indicator of littoral mercury pollution (Translated from French). C. R. Acad Hebd Seances Acad Sci. D. 1977, 284, 445–447, Cited by Rizk et al. 1999 (Ref. 118). [Google Scholar]

- Gaur, N.; Flora, G.; Yadav, M.; Tiwari, A. A review with recent advancements on bioremediation-based abolition of heavy metals. Environ. Sci. Process Impacts 2014, 16, 180–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jitar, O.; Teodosiu, C.; Oros, A.; Plavan, G.; Nicoara, M. Bioaccumulation of heavy metals in marine organisms from the Romanian sector of the Black Sea. New Biotech. 2015, 32, 369–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stout, E.P.; Kubanek, J. Marine macroalgal natural products. In Reference Module: Chemistry, Molecular Sciences and Chemical Engineering Comprehensive Natural Products II Chemistry and Biology; 2010; Volume 2, pp. 41–65. [Google Scholar]

- Amasha, R.H.; Aly, M.M. Removal of dangerous heavy metal and some pathogens by dried green algae collected from Jeddah coast. Pharmacophore 2019, 10, 3–13. [Google Scholar]

- El-Malek, F.; Rofeal, M.; Zabed, H.M.; Nizami, A.-S.; Rehan, M.; Qi, X. Microorganism-mediated algal biomass processing for clean products manufacturing: status, challenges, and outlook. Fuel 2022, 311, 122612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rathinam, A.; Maharshi, B.; Janardhanan, S.K.; Jonnalagadda, R.R.; Nair, B.U. Biosorption of cadmium metal ion from simulated wastewaters using Hypnea valentiae biomass: A kinetic and thermodynamic study. Bioresour. Technol. 2010, 101, 1466–1470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fawzy, M.A. Phycoremediation and adsorption isotherms of cadmium and copper ions by Merismopedia tenuissima and their effect on growth and metabolism. Environ. Toxicol. Pharmacol. 2016, 46, 116–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qari, R.; Siddiqui, S.A. A comparative study of heavy metal concentrations in red seaweeds from different coastal areas of Karachi, Arabian Sea. Indian J. Mar. Sci. 2010, 39, 27–42. [Google Scholar]

- Hamdy, S.M.; Shaban, A.M.; Abdel Aziz, Y.S.; Mahmoud, A.M.; Moemen, L.A.; Ibrahim, W.M.; Gad, N.S. Ameliorative role of Jania rubens alga against toxicity of heavy metal polluted water in male rats. Sci. Technol. & Public Policy 2018, 2, 38–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nonomura, A.M. Development of Janczewskia morimotoi (Ceramiales) on its host Laurencia nipponica (Ceramiales, Rhdophyceae). J. Phycol. 1979, 15, 154–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.-K.; Vo, T.-S.; Ngo, D.-H. Potential application of marine algae as antiviral agents in medicinal food. Adv. Food Nutr. Res. 2011, 64, 245–254. [Google Scholar]

- Baweja, P.; Kumar, S.; Sahoo, D.; levine, I. Biology of seaweeds, Chapter 3. Seaweed in Health and Disease Prevention 2016, 41–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kowanga, K.; Mauti, G.O.; Mauti, E.M. Biosorption for lead (II) ions from aqueous solutions by the biomass of Spyridia filamentosa algal species found in Indian Ocean. J. Sci. Innov. Res. 2015, 4, 218–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valarmathi, N.; Ameen, F.; Almansob, A.; Kumar, P.; Arunprakash, S.; Govarthanan, M. Utilization of marine seaweed Spyridia filamentosa for silver nanoparticles synthesis and its clinical applications. Mate. Lett. 2020, 263, 127244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osuji, L.C.; Onojake, C.M. Trace heavy metals associated with crude oil: a case study of Ebocha-8 oil-spill-polluted site in Niger Delta, Nigeria. Chem. Bio. Divers. 2004, 1, 1708–1715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baghour, M. Algal degradation of organic pollutants. In Handbook of Eco-materials; Martínez, L., Kharissova, O., Kharisov, B., Eds.; Springer: Cham, 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juhmani, A.-S.; Vezzi, A.; Wahsha, M.; Buosi, A.; De Pascale, F.; Schiavon, R.; Sfriso, A. Diversity and dynamics of seaweed associated microbial communities inhabiting the lagoon of Venice. Microorganisms 2020, 8, 1657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Menaa, F.; Wijesinghe, P.A.U.I.; Thiripuranathar, G.; Uzair, B.; Iqbal, H.; Khan, B.A.; Menaa, B. Ecological and industrial implications of dynamic seaweed-associated microbiota interactions. Mar. Drugs 2020, 18, 641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ren, C.-G.; Liu, Z.-Y.; Wang, X.-L.; Qin, S. The seaweed holobiont: from microecology to biotechnological applications. Microb. Biotechnol. 2022, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fei, X. Solving the coastal eutrophication problem by large scale seaweed cultivation. Hydrobiologia 2004, 512, 145–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mocek-Płóciniak, A.; Mencel, J.; Zakrzewski, W.; Roszkowski, S. Phytoremediation as an effective remedy for removing trace elements from ecosystems. Plants 2023, 12, 1653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laurens, L.M.L.; Lane, M.; Nelson, R.S. Sustainable seaweed biotechnology solutions for carbon capture, composition, and deconstruction. Trends Biotechnol. 2020, 38, 1232–1244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butt, M.A.; Voronkov, G.S.; Grakhova, E.P.; Kutluyarov, R.V.; Kazanskiy, N.L.; Khonina, S.N. Environmental monitoring: A comprehensive review on optical waveguide and fiber-based sensors. Biosensors 2022, 12, 1038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Species | Family | Main constituents | Possible roles | References |

| Acetabularia caliculus | Polyphysaceae | Proteins (4.5%), lipids (4.2%), carbohydrates (33.4%), and ash including minerals (57.3%), others (0.6%) as secondarymetabolites such as phenolic compounds and terpenoids | Phycoremediation of: Cd, Cr, Cu, Hg, Ni, Pb, and Zn, organic components, and nutrients such as nitrogen and phosphorus, antioxidants | [118,123,124] |

| Avrainvillea amadelpha | Dichotomosiphonaceae | Rawsonol a, isorawsonol-steroids, bromophenols, Sulfono-glycolipid |

Antioxidants, anticancer, H2O2 scavenging activity, hemagglutination, antibacterial, heavy metal phycoremediation: (Cd, Cu, Pb) | [118,125,126,127] |

| Boodlea composita | Boodleaceae | β-sitosterol, loliolide b and 13²-hydroxy-(13²-S)-phaeophytin-a, fatty acids, sterols, sulphated polysaccharide, agglutinins, glycinebetaine, prolinebetaine | Possible remediation role in polluted saline waters | [118,128,129,130,131,132] |

| Bryopsis implexa | Bryopsidaceae | Xylan, carotenoids, free amino and fatty acids, sterols, bryopsin, kahalalide F | Possible role in remediating polluted and saline waters, anticancer action | [114,118,125,133] |

| Caulerpa mexicana | Caulerpaceae | Siphonaxanthin c, siphonein d, various polysaccharides, fatty acids, amino acids | Degradation of petroleum hydrocarbons, possible removing heavy metals, nutritional uses, medical uses: antiviral, antibacterial, etc. | [118,134,135,136] |

| Chaetomorpha spp., (5 species): C. aerea, C. indica, C. linum, C. koeiei, C. patentarama | Cladophoraceae | Sulphated polysaccharides; containing arabinose, and galactose, and other sugars such as glucose, xylose, and fucose, haemolytic saponin | Anticoagulant activities (antithrombin type), possible toxic, remediation of IWW | [118,137,138,139,140,141] |

| Cladophora spp., (3 species): C. koeie, C. patentirama, C. sericoides | Cladophoraceae | Pigments such as β-carotene, xanthophyll, xanthphyll-epoxide, violaxanthin, and other related pigments, water soluble sulphated polysaccharides, other related compounds, various types of amino acids | Phytoremediation of petroleum hydrocarbons, antibacterial and antiviral activities, antimitotic and cytotoxic activities, monitoring heavy metals such as Cd, Co, Cr, Cu, Fe, Hg, Mn, Ni, Pb, and Zn | [118,142,143,144,145,146] |

| Cladophoropsis sundanensis | Boodleaceae | Xanthophyll, loroxanthin siphonaxanthin | Little about role in phytoremediation; needs more investigation | [118,147,148] |

| Dictyosphaeria cavernosa | Siphonocladaceae | Alkylxanthate, bicyclic lipid, dictyosphaerin, some heavy metals, | Possible phycoremediation of heavy metals, anti-mosquito larvae | [118,123,149,150,151] |

| Enteromorpha spp., (2 species): E. kylinii, E. ramulosa | Ulvaceae | Water soluble polysaccharides, fatty acids and sterol, essential amino acids | Bioactivity such as hypocholesterolemic effect, antibacterial and diuretic activities, mutagenic activity, indicator of pollution | [118,152,153,154,155] |

| Rhizoclonium kochianum | Cladophoraceae | Scanty information, crystalline cellulose | Antibacterial, beta-blocker, 5-hydroxytryptamine blocker, folk medicine for burns, vermifuge, possible phycoremediation of heavy metals and organic compounds, nutritional value |

[118,156] |

| Ulva purtusa | Ulvaceae | Polysaccharides, fatty acids, non-acidic glycolipid fractions, monogalactosyl, diglyceride, isofucosterol, amino acids, ascorbic acid (vitamin C), heavy metals such as Fe, Mn, Ti, Ni, Cu, Pb, and others | Bioindicator of seawater pollution, remediation of petroleum hydrocarbons and heavy metals | [118,154,157,158,159,160] |

| Species | Family | Main constituents | Possible roles | References |

| Colpomenia sinuosa | Scytosiphonaceae | Cytotoxic fractions with complex mixture of saturated and unsaturated fatty acids, carotenoid fucoxanthin, some amino acids | Possible role of heavy metal remediation, its presence is a sign of pollution | [118,161,162,163] |

| Cystophyllum muricatum | Ceratophyllaceae | Little information available, presence of some fatty acids | Possible remediation of heavy metals and organic components | [118,164] |

| Cystoseira spp., (2 species): C. myrica, C. trinodis | Sargassaceae | A sulphated polysaccharide containing some soluble sugars, fucoidan, glycinebetaine and related compounds, alginic acid, uronic acid, laminaran, mannitol, amino acids, palmitic acid, lipid components, diterpenoids, etc. | Remediation of heavy metals in seawater | [114,118,159,165,166,167] |

| Dictyota cervicornis | Dictyotaceae | Fucoidan, diterpenes, diterpenoids, sterols such as fucosterol, phloroglucinol as toxic compound | Cytotoxic effects, many deterred feedings by some sea animals such as fish and sea urchins etc., possible phytoremediation of heavy metals and petroleum hydrocarbons | [118,168] |

| Ectocarpus mitchellae | Ectocarpaceae | Mannitol, ectocarpene, fucoidan, alginin, ectocarpene | Sexual pheromone, hemagglutinin activity, possible remediation of heavy metals and petroleum hydrocarbons | [118,154,169] |

| Giffordia mitchellae | Acinetosporaceae | Giffordene, stereoisomers | Hemagglutinin activity, no reports about remediation, needs to be tested for phycoremediation | [118] |

| Hormophysa cuneiformis | Sargassaceae | Carbohydrates (59%), proteins (9%), lipids (7%), and ash (25%), sterols, fatty acids, amino acids, some heavy metals are found such as Fe, Zn, Co, Pb, Cu, Mn, and Al | Bioindicators for heavy metal pollution, anticancer and possible antimicrobial potential | [118,170,171,172] |

| Padina australis | Dictyotaceae | Sulphated heteropolysaccharides, fucan contained monosaccharides, neutral sugars such as arabinose, fucose, galactose, glucose, mannose, rhamnose, and xylose, other sugar components complexes are found such as uronic acid, fucosterol, fatty and amino acids, acids such as glutamic acid, arginine, and proline | Anticoagulation activity, human HL-60 leukemia cell-line, bioactive primary and secondary metabolites with antibacterial activity, against Bacillus spp, and Staphylococcus spp., monitoring heavy metals, high capacity of the polyphenols for the chelating of heavy metals, possible heavy metal phycoremediation | [118,173,174,175,176] |

| Sargassum spp., (2 species): S. aquifolium, S. boveanum | Sargassaceae | Polysaccharides, sargassan: many monosaccharides in this compound are found, amino acids are found in the peptide portion, high fucoidan content containing some complex polysaccharides, high percentage of alginate, mannitol, fatty acids of various types are found, glycerides, and many other complex compounds, etc. | High nutritional values, trace elements are found such as Ag, Al, As, Au, Ba, Ce, Co, Cr, Sr, Cs, Fe, Mn, Sb, Sc, Te, V, U, and Zn, remediation of trace elements is very likely, biological activities, antitumor activity, interferon-activity, immunosuppressive effects, anticoagulant activity, hypo-cholesterolemic activity, other medical uses were reported | [118,159,177,178,179] |

| Turbinaria conoides | Sargassaceae | Alginic acid, alginate, laminaran, fucan complex contains monosaccharides, D-mannitol, fucosterol, antibiotic sarganin, antifungal activity, turbinaric acid | Antibacterial and antifungal activities, cytotoxic activity, herbivorous activity, possible phycoremediation activity of some heavy metals: thulium, role in biosynthesis of nanoparticles | [118,180,181,182] |

| Species | Family | Main constituents | Possible roles | References |

| Amphiroa fragilissima | Corallinaceae | Cholesterol, non-protein amino acids, low molecular-weight carbohydrates, floridoside, mannoglyceric acid, bioactive compounds such as ellagic acid, gallic acid, and phenolic compounds, major polyamines are found, trace elements are found such as Fe, Zn, Co, Pb, Mn, Cu, Al, etc. | Possible role of remediation in polluted water, ellagic acid may help prevent cancer cells to grow, gallic acid contains antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, and antineoplastic properties, phenolic compounds may have more roles: antitumoral, anticoagulant, antiviral, and hypocholesterolemic | [118,183,184] |

| Centroceras calvulatum | Ceramiaceae | Rich in protein, non-protein amino acids, fatty acids, cholesterol, rich in vitamin C | Might be non-conventional food and feed, possible remediation role of polluted sea water | [118,185] |

| Ceramium luetzelbergii | Ceramiaceae | Agar, some complex compounds containing monosaccharides are found, carotenoids, cholesterols, bromoperoxidase containing vanadium (V), trimethylamine, nitrate, choline, crystalline sulphure, Hg is found in some species of Ceramium | Possible indicator of Hg, possible universal monitor for heavy metals, antibacterial activity, antimitotic acitivity, agglutinin activity, folk medicine used for chest diseases | [118,186,187,188] |

| Chondria armata | Rhodomelaceae | Polysaccharides composed of mannose and galactose, xylogalactan sulphate, chondriol: a halogenated acetylene, volatile acids: sarganin and chonalgin, amino acids with some new amino acids, chondriamides, hemmagglutinins, cyclic polysuphides, some trace elements are found such as: Fe, Zn, Co, Pb, Mn, Cu, and Al | Possible role in remediation of heavy metals, antibiotic action, cytotoxic activity, activity against animal erythrocytes, other medical activities were recorded such as antitumor, antimicrobial, and antiviral effects | [54,118,189] |

| Digenea simplex | Rhodomelaceae | Agar contains: galactose, glucose, xylose, etc., agarose, sulphate ester, pectin analysis showed the presence of galactose, fructose, and arabonic acid, floridoside, digenic acid (kainic acid) | Some constituents can be used in medicine, food industry, cosmetic, digenic acid is effective in expelling ascaris, possible to remediates heavy metals and organic compounds | [118,190,191] |

| Hypnea spp., (2 species): H. cervicornis, H. valentiae | Cystocloniaceae | Sulphated galactans, carotenoids, such as α-carotene, β-carotene, lutein, and possibly others, peptidic agglutanins, phycolloid containing ƙ-carrageenan, various forms of sterols and fatty acids, contain some elements such as Ca, Mg, K, Al, Fe, Mn, Cr, Ni, Cd, and Co | Food and animal feed, some agglutanins have agglutinating activity towards a variety of biological cells, including tumour, against human blood groups A, B, O, and animal erythrocytes, sulphated polysaccharides might have role in supporting bones and may be used as anti-inflammatory agents and other medical uses, pharmacological constituents could play various roles such as muscle relaxant, hypothermic activity, phytoremediation of heavy metals such as Cd | [115,118,182,192,193] |

| Jania spp. (2 species were recorded): J. adhaerens, J. ungulata | Corallinaceae | Various carotenoids such as β-carotene, zeaxanthin, fucoxanthin, 9͂-cis-fucoxanthin, fucoxanthinol, 9͂-cis-fucoxanthinol, and epimeric mutatoxanthins, other organic compounds might be found, some heavy metals might be found | Phytoremediation of heavy metals is possible, not much information is available for some species, ameliorative effect to the toxicity of heavy some heavy metals for some animals and possibly humans | [118,194,195] |

| Laurencia spp. (6 species were recorded): L. elata, L. glandulifera, L. intermedia, L. paniculata, L. papillosa, L. perforata | Rhodymeniaceae | Various types of polysaccharides, sesquiterpenoides, diterpenoids, triterpenoids, other compounds such as C15-acetogensis, secondary metabolites such as sterols, fatty acids, amino acids, mineral elements: K, Na, Ca, Mg, Fe, Zn, Pb, Co, Cu, Mn, Al, possibly others: Cr, Ni, Cd, etc. | Various roles played by this macro-alga as food, medicine, numerous ecological roles*, refuge for marine organisms, hosts of various microorganisms and parasitic algae (such as Janczewskia), they are fed on by some grazers such as crabs, queen conch, and sea hares, possible roles in phycoremediation | [118,147,196] |

| Polysiphonia spp. (4 species were recorded): P. brodiei, P. crassicolis, P. ferulacea, P. kampsaxii | Rhodomelaceae | Sulphated galactans; polysaccharides belong to the agar class and agarose, other related residues such as mannitol and trehalose, etc., bromophenols, fatty acids, phospholipids, polar lipids, some structural components | Antibiotic (antibacterial & antifungal) and antioxidant activities, other roles such as antimitotic, increase survival of vorticellids and serum lipolytic activity, agglutinin, heavy metals are found such as As, Cd, Cr, Cu, Fe, Hg, Mn, Mo, Ni, Pb, Ti, V, and Zn, possible phycoremediation of petroleum hydrocarbons | [118,159,197,198] |

| Spyridia filamentosa | Callithamniaceae | Sterols such as cholesterol, fatty acids, agglutinin is found in some species, main elements found: Al, Ca, Co, Cu, Fe, K, Mg, Mn, Na, Pb, and Zn | Antifungal activity of aqueous extracts, biosynthesis of silver nanoparticles, removing heavy metals from industrial wastewater | [118,199,200] |

| Wurdemannia miniatat | Solieriaceae | Little information about the chemical constituents (needs to be investigated) | No reported roles of this species | [118] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).