1. Introduction

Since oral infections affect people’s health and the country’s economy, they are a cause for concern [

1,

2]. As per the World Health Organization (WHO) report 2022 [

3], approximately 3.5 billion people worldwide are affected by oral diseases. Dental caries are particularly noteworthy, affecting an estimated 2.4 billion people globally in 2017 [

4].

Although Brazil is one of the countries with the highest number of dentists and the second largest producer of scientific dental articles in the world [

5], the concept of a nation that values smiles and oral health remains characteristic of a select, privileged segment of the Brazilian population. The integration of these professionals into public policies, such as dental clinics in Family Health Units (USF), is relatively recent [

6]. Their distribution between public and private sectors is unequal, potentially creating barriers to dental care access in Brazil [

7].

Biological and sociocultural factors, particularly economic deprivation and the sociosanitary conditions of the population [

8], can influence the formation of dental biofilm and therefore the development of various oral diseases that impact the quality of life [

9].

Among these oral manifestations, biofilm is considered a significant etiological factor for caries and other periodontal diseases. Biofilm promotes the proliferation of microorganisms such as Streptococcus spp. and lactobacilli, which in turn lead to progressive dental demineralization, both painful and nonpainful carious lesions, and eventual tooth loss [

10,

11]. Among bacteria, Streptococcus mutans is recognized as the primary etiological and determinant factor of dental caries [

12]. However, other species such as S. mitis, S. sanguinis, and S. salivarius have also been associated with dental caries [

13].

Therefore, assessing Streptococcus species in the oral cavity along with sociocultural factors may improve understanding of oral health and aid in the development of educational initiatives. The aim of the present study was to compare the effect of sociocultural factors on biofilm colonization of dental surfaces in subjects attending public and private dental clinics.

2. Materials and Methods

Study Design and Query

For this study, sample collection and sociodemographic surveys involved dental patients from both public health clinics and private clinics. The research was conducted from March 23 to August 17, 2022, in two study sites: the dental clinic of the USF Manoel Cipriano and a private dental clinic (PC), both located in the city of Ipiaú, state of Bahia, Brazil. All subjects gave their informed consent for inclusion before they participated in the study.

A total of 100 participants were enrolled in the study, with 50 participants from each site. Inclusion criteria were individuals aged ≥ 18 years, of either sex, not undergoing dental treatment, no antibiotics for at least 15 days, and having at least three teeth in the mouth. Participants had also brushed their teeth at least two hours prior to sample collection. Women were not pregnant at the time of sample collection. Exclusion criteria included oral microbiological alterations, comorbidities, oral cancer, being edentulous, or having a positive COVID-19 diagnosis at the time of enrollment.

Participants were recruited by reviewing the USF medical and dental clinical records on the day and time of their consultation, either at the USF or at the private clinic. Research objectives were explained, and participants were given the opportunity to read the Informed Consent Form (ICF) and ask questions at this time. In addition, consenting patients were asked about symptoms such as colds, coughs, and shortness of breath, and when they last brushed their teeth. In cases where collection at USF was not feasible, researchers made appointments with community health workers (CHWs) and visited participants in the community. After obtaining consent, a semi-structured questionnaire was administered to assess clinical and socioepidemiological aspects (accessible from:

https://figshare.com/s/330f0ce9e136ba85c5ea).

Dental Biofilm Collection and Analysis

Dental biofilm samples were collected by rubbing a sterile swab on the tooth surface near the gingival margin. The swab was then placed in a Stuart transport medium tube (Absorve, Cral). Immediately after biofilm collection, a sample of spontaneous saliva was collected in a sterile 15 mL polystyrene tube for the Snyder test. Both samples were transported to the Laboratório de Microbiologia Aplicada at Universidade Estadual de Santa Cruz, city of Ilhéus, Bahia within three hours of collection.

Each swab was transferred to a 1.5 mL polypropylene tube containing 600 μL of 0.9% NaCl solution. After homogenization, 100 μL of the solution were transferred onto Mitis-Salivarius agar (MS; HiMedia) and spread evenly across the plate using a sterile swab. Plates were then incubated for 24 hours at 37 ± 0.1 °C in a candle jar as per described in a previous study [

14].

Colonies with the following characteristics were analyzed and counted: 0.5–1 mm in diameter, convex, wavy, opaque, light blue, granular with a “ground glass” appearance, and rough margins, sometimes exhibiting a shiny bubble on the colony surface or along its margin. After counting, one colony was selected and co-cultured on blood agar, then incubated for 24 hours at 37±0.1°C in a candle jar. Colony morphology, Gram staining, and catalase tests were then performed to confirm genus identity as Streptococcus. In addition, a salt tolerance test was performed to differentiate it from Enterococcus faecalis. Bacteria were inoculated into 6.5% NaCl medium and incubated for 48 hours at 37 ± 0.1 °C in a candle glass. Control samples included medium without bacteria and medium inoculated with Enterococcus faecalis (Andrewes and Horder) Schleifer and Kilpper-Balz (ATCC 5129), known for their tolerance to salt. Turbidity of the medium indicated the ability of bacterial isolates to tolerate salt concentrations and distinguished Streptococcus species (nonturbid) from E. faecalis (turbid/flocculation) [

15]. After identification, one colony was selected and cultured in Brain and Heart Infusion (BHI) broth supplemented with 5% blood and a 20% glycerol solution (LGCBIO, Brazil) and incubated for 24 hours at 37 °C in a microaerophilic atmosphere. The colony was then stored at -20 °C.

Sucrose, sorbitol, and mannitol tests were performed to confirm the Streptococcus species. For this, stored bacteria were cultured in 5% blood BHI broth under microaerophilic conditions for 24 hours, then cultured on blood agar and incubated for another 24 hours at 37 ± 0.1 °C in a candle jar. A negative control of sugar-free medium was included. Samples were then incubated for 72 hours at 37 ± 0.1 °C in a candle jar. Any utilization of sugar by bacteria was deemed indicative of S. mutans [

15].

Colony counts were expressed as colony forming units per 100 μL (CFU/100 μL) and samples were classified into five categories: ≥500 CFU; 200-499 CFU; 100-199 CFU; 1-99 CFU; and zero CFU.

Statistical Analysis

Findings were analyzed descriptively and analytically. Graphs were generated using Prism, version 5 for Windows (GraphPad Prism Software Inc., 2007). Multiple Correspondence Analysis (MCA) of categorical variables (sociodemographic aspects and biofilm colonization) across different dental services was performed using R statistical software [

17]. Pearson’s test with significance set at p < 0.05 and 95% confidence interval was applied to correlate the use of medicinal plants, brushing habits, salivary acidity, and CFU density.

3. Results

In the present study, socioeconomic data (

Table 1) showed a preponderance of women over men in both public and private dental services. The majority of participants were married or in stable relationships. The mean age of participants was 42.0 ± 11.9 years, with notable age groups being 25–39 years (39%; nT=39/100) and 40–59 years (44%; nT=44/100).

Both the public and private services reflected typical Brazilian miscegenation, with approximately half of the participants identifying as brown and more self-identified black individuals in the public service.

Level of education was similar between the two groups; however, private service participants appeared to have a slightly higher level of education than public service participants. Social status was similar between the two groups, as indicated by the number of people living in the same household.

Regarding employment status, participants living in rural areas were more likely to have informal work than those living in urban areas and attending private dental services. Unemployment rates were low in both study groups, with only 3% (nPC = 2/50; nUSF = 1/50) reporting unemployment.

Among the sociocultural aspects (

Table 2), the habits of tooth brushing and alcohol consumption stand out. Overall, approximately half of the participants reported brushing their teeth an average of three times a day, but participants from private clinics reported a higher frequency of tooth brushing than those from public services (

Figure 2). Additionally, alcohol consumption was more prevalent among participants from private services.

Regarding the use of medicinal plants in the last six months, there was no statistical difference between the two services, but there was a greater tendency to use medicinal plants among participants from the public service located in a rural area (78%; n = 31/50). Notably, none of the groups reported using medicinal plants specifically for oral conditions.

Concerning the use of antibiotics by the participants three months prior to the study, most of them reported not to have used any. Among those who reported use, amoxicillin, azithromycin, cephalexin and ciprofloxacin were reported as antimicrobials.

Observing medicinal plants used by the participants in the six months prior to the survey (

Table 3), the responses were quantitatively equivalent between the two groups. However, the types of plants reported differed significantly between participants in private and public services.

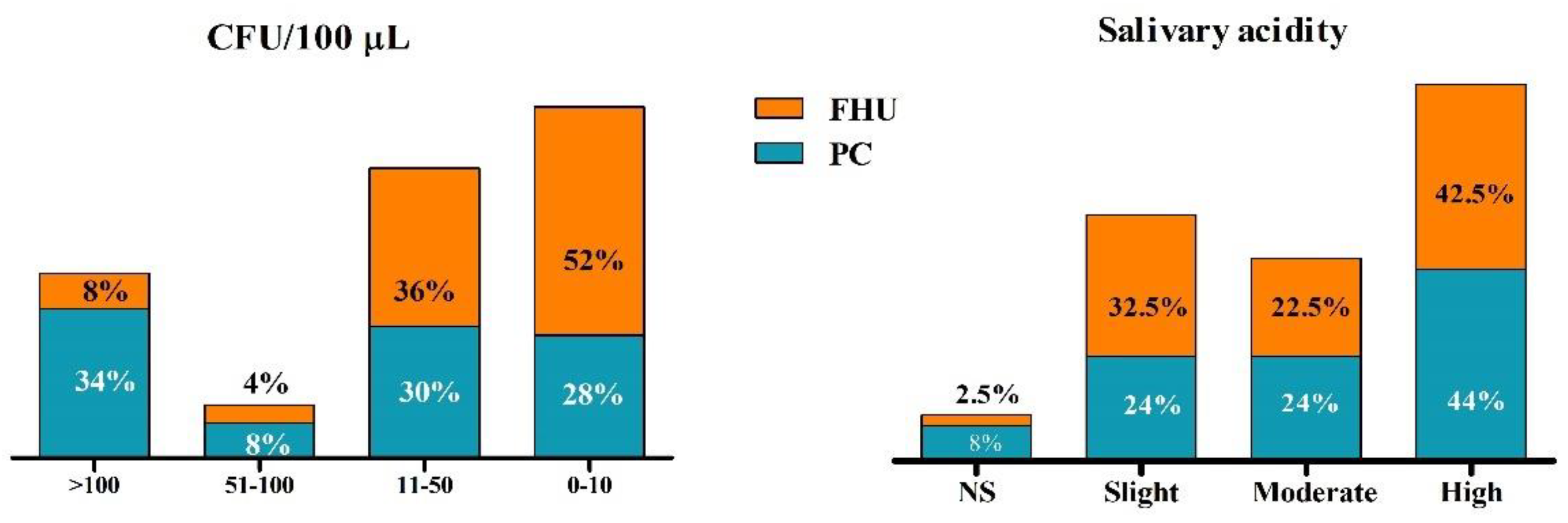

Colony forming unit enumeration and isolate identification were performed by laboratory experiments and are detailed in the Supplementary Material. Regarding the quantification of typical Streptococcus colonies isolated from dental biofilm and their tendency to cause dental caries, the findings indicated a higher density of CFU/100 μL in participants from private clinics (

Figure 1), while both groups had a similar tendency towards salivary acidification. However, when both variables were evaluated together, no significant association was observed (r = 0.15).

Of the selected colonies, presumptive identification of Streptococcus species by biochemical testing confirmed the presence of nine S. mutans colonies, 43 non-mutans Streptococcus colonies, and 10 inconclusive samples.

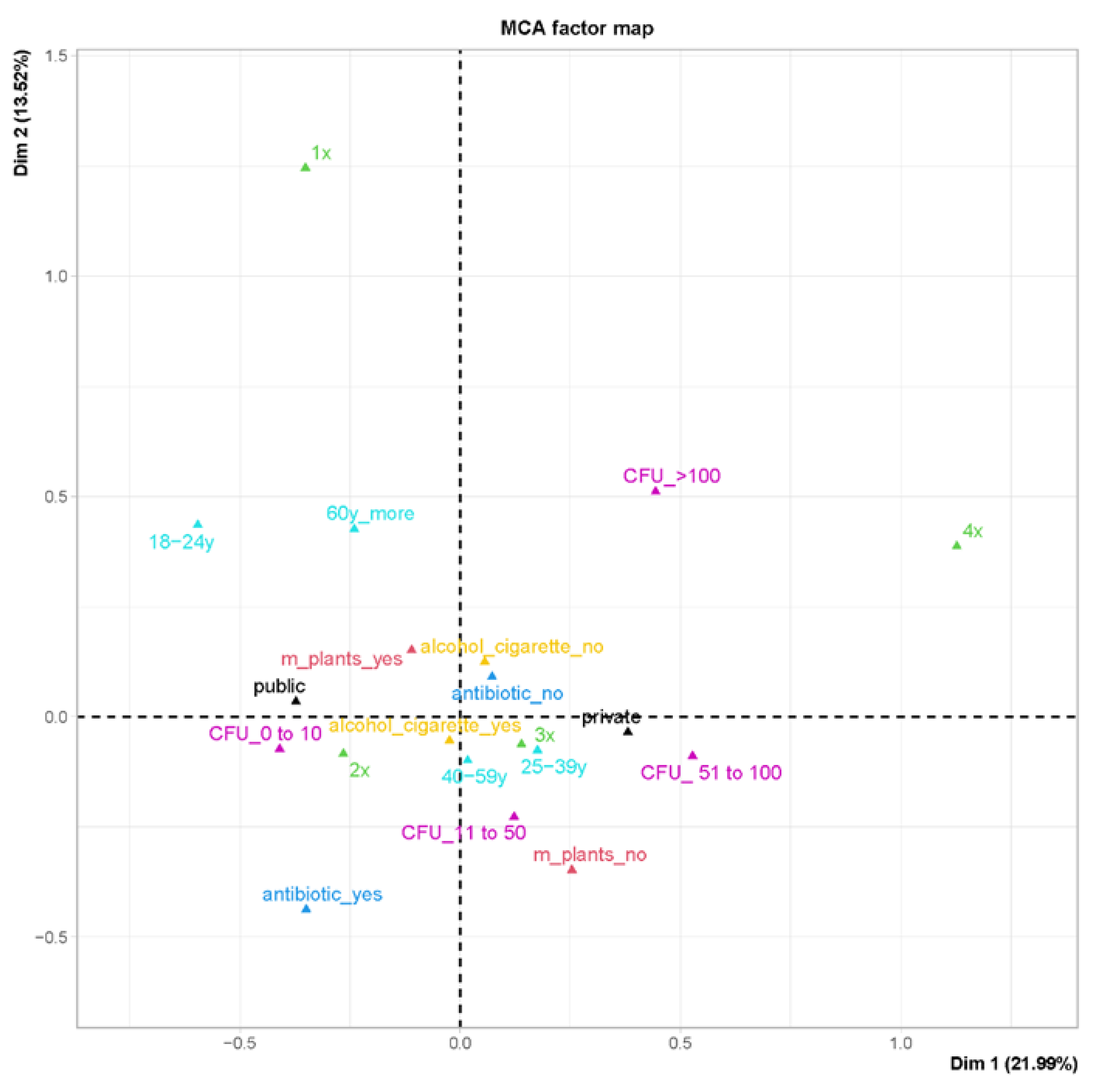

When multiple correspondence analysis was performed, the association between sociodemographic aspects, biofilm colonization (Streptococcus CFU/100µL) and distinct dental services (

Figure 2) in the community studied led to the inference that 1) participants served at private dentistry service are more prone to consume alcohol and cigarette; 2) the possibility of having dental problems (high number of UFC/100µL) was not associated with good oral hygiene practices; 3) the use of antimicrobials is more related to access to health care; and 4) the use of medicinal plants is highly associated with public health service.

Figure 2.

Multiple correspondence analysis (MCA) of sociodemographic aspects of categorical variables, antimicrobial and medicinal plant use, and biofilm colonization according to different dental services (public versus private). Legend: Age range (light blue) in years (y) - 18-24y, 25-39y, 40-59y, 60y_more; alcohol and cigarette consumption (yellow) (alcohol_cigarette_no/alcohol_cigarette_yes); antibiotic use in the last 3 months (cian blue) (antibiotic_yes/antibiotic_no); use of medicinal plants in the last 6 months (light red) (m_plants_no/m_planst_yes); and colony forming unit (CFU) rank (pink) (CFU_0 to 10/CFU_11 to 50/CFU50 to 100; CFU_>100); frequency of toothbrushing/day (green) 1x, 2x, 3x, and 4x.

Figure 2.

Multiple correspondence analysis (MCA) of sociodemographic aspects of categorical variables, antimicrobial and medicinal plant use, and biofilm colonization according to different dental services (public versus private). Legend: Age range (light blue) in years (y) - 18-24y, 25-39y, 40-59y, 60y_more; alcohol and cigarette consumption (yellow) (alcohol_cigarette_no/alcohol_cigarette_yes); antibiotic use in the last 3 months (cian blue) (antibiotic_yes/antibiotic_no); use of medicinal plants in the last 6 months (light red) (m_plants_no/m_planst_yes); and colony forming unit (CFU) rank (pink) (CFU_0 to 10/CFU_11 to 50/CFU50 to 100; CFU_>100); frequency of toothbrushing/day (green) 1x, 2x, 3x, and 4x.

4. Discussion

The present study has demonstrated the influence of sociodemographic and cultural factors on Streptococcus species biofilm colonization in two different contexts of dental service: public health and private clinic.

First, contrary to expectations, there was no simple relationship between toothbrushing habits and biofilm colonization in either group. Although participants from the private clinics reported a higher frequency of tooth brushing, they had a higher density of Streptococcus colonization. According to the literature, higher brushing frequency is typically associated with less biofilm formation and fewer bacteria adhering to tooth surfaces [

18]. In this study, the higher density of CFU/100µL in the private clinic samples may be attributed to the minimal time since last brushing. Participants reported brushing their teeth the night before sample collection, approximately eight hours prior to sample collection. While participants were instructed to avoid brushing within two hours of sample collection, the maximum allowable time since brushing was not clearly communicated to the first ten participants. This lack of clarity may have contributed to the uncountable CFU (20%) observed in the private clinic group.

Another point to consider is the analysis of CFU/100µL and the Snyder test together. Although no association was found between Snyder test findings and CFU counts, patients from private clinics showed a greater tendency to salivary acidification. As reported in the literature [

19], individuals from private clinics are more prone to dental caries than participants from rural areas. Also, the lower density of Streptococcus in the samples from the public service participants may be related to the number of dental remnants observed during sampling. Of the 50 participants, 28 had partial and/or full dentures, indicating a significant number of edentulous individuals.

A third point to note is that the high reported rates of daily tooth brushing observed in this study may not accurately reflect the actual habits of the participants. Positive responses regarding the frequency of daily tooth brushing may be influenced by social norms and oral hygiene programs [

20].

Alcohol consumption was also significant in this study, with notable differences between the two populations studied. Due to ethical restrictions and study design, neither the prevalence of dental caries nor the frequency of alcohol consumption was determined. However, it is well documented that excessive alcohol consumption may contribute to dental erosion [

21]. Combined with cigarette and marijuana use and the high prevalence of dental caries among participants attending private clinics, these findings underscore the need for further study and more robust oral health promotion campaigns among this population.

5. Conclusions

Ultimately, the different characteristics of the users of two Brazilian dental care systems reflect both social inequalities and the exchange of knowledge between neighboring social groups. Inequalities are more pronounced in terms of public health investment for populations with accessibility problems than in terms of cultural or educational diversity. Therefore, investments in oral health improvement campaigns should be implemented in both populations to address these challenges.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Edmone Eça, Luciana Carvalho and Aline Conceição; Data curation, Aline Conceição; Formal analysis, Marcelo Ferraz, Luciana Carvalho and Aline Conceição; Investigation, Edmone Eça, Mariana Oliveira, Valdineia Oliveira and Aline Conceição; Methodology, Edmone Eça, Luciana Carvalho and Aline Conceição; Project administration, Aline Conceição; Supervision, Aline Conceição; Validation, Edmone Eça, Luciana Carvalho and Aline Conceição; Visualization, Mariana Oliveira, Valdineia Oliveira, Marcelo Ferraz, Luciana Carvalho and Aline Conceição; Writing – original draft, Edmone Eça, Luciana Carvalho and Aline Conceição; Writing – review & editing, Edmone Eça, Mariana Oliveira, Valdineia Oliveira, Marcelo Ferraz, Luciana Carvalho and Aline Conceição.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and the informed consent process was conducted in accordance with the guidelines approved by the Human Research Ethics Committee at Universidade Estadual de Santa Cruz under CAAE registry number 51682321.7.0000.5526.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors on request.

Acknowledgments

We thank the community of Ipiaú, Bahia, Brazil, for participating in the research. We also thank the municipality of Ipiaú and the owner of the Vivace clinic for granting access to the research sites.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Peres, M.A.; Macpherson, L.M.D.; Weyant, R.J.; Daly, B.; Venturelli, R.; Mathur, M.R.; Listl, S.; Celeste, R.K.; Guarnizo-Herreño, C.C.; Kearns, C.; et al. Oral Diseases: A Global Public Health Challenge. Lancet 2019, 394, 249–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Brien, K.J.; Forde, V.M.; Mulrooney, M.A.; Purcell, E.C.; Flaherty, G.T. Global Status of Oral Health Provision: Identifying the Root of the Problem. Public Heal. Challenges 2022, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization (WHO) Global Oral Health Status Report: Towards Universal Health Coverage for Oral Health by 2030; Geneva, 2022.

- Bernabe, E.; Marcenes, W.; Hernandez, C.R.; Bailey, J.; Abreu, L.G.; Alipour, V.; Amini, S.; Arabloo, J.; Arefi, Z.; Arora, A.; et al. Global, Regional, and National Levels and Trends in Burden of Oral Conditions from 1990 to 2017: A Systematic Analysis for the Global Burden of Disease 2017 Study. J. Dent. Res. 2020, 99, 362–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vieira, A.R.; Castro, R.D. de Brazilian Dentistry Is Among the Best in the World. Is It True? Pesqui. Bras. Odontopediatria Clin. Integr. 2022, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaves, S.C.L.; Almeida, A.M.F. de L.; Reis, C.S. dos; Rossi, T.R.A.; Barros, S.G. de Política de Saúde Bucal No Brasil: As Transformações No Período 2015-2017. Saúde em Debate 2018, 42, 76–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cascaes, A.M.; Dotto, L.; Bomfim, R.A. Tendências Da Força de Trabalho de Cirurgiões-Dentistas No Brasil, No Período de 2007 a 2014: Estudo de Séries Temporais Com Dados Do Cadastro Nacional de Estabelecimentos de Saúde. Epidemiol. e Serviços Saúde. [CrossRef]

- Silva, J.V. da; Machado, F.C. de A.; Ferreira, M.A.F. As Desigualdades Sociais e a Saúde Bucal Nas Capitais Brasileiras. Cien. Saude Colet. 2015, 20, 2539–2548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rosane de Souza Ramos A Influência Dos Aspetos Culturais e Sociais Na Saúde Bucal, Universidade Federal de Minas Gerais, 2011.

- Fejerskov, O.; Kidd, E. Cárie Dentária: A Doença e Seu Tratamento Clínico; Livraria Santos: São Paulo, 2005; ISBN 85-7288-515-3. [Google Scholar]

- Pereira, R.O., Fontes, N.M., Batista, M.I.H. de M., Eds.; Menezes, M.L.F.V. de; Macedo, Y.V.G. de; Ferraz, N.M.P.; Matos, K. de F.; Pereira, R.O.; Fontes, N.M.; Batista, M.I.H. de M.; Paulino, M.R. A Importância Do Controle Do Biofilme Dentário: Uma Revisão Da Literatura. Rev. Eletrônica Acervo Saúde 2020, e3698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirthiga, M.; Murugan, M.; Saikia, A.; Kirubakaran, R. Risk Factors for Early Childhood Caries: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Case Control and Cohort Studies. Pediatr. Dent. 2019, 41, 95–112. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Veenman, F.; van Dijk, A.; Arredondo, A.; Medina-Gomez, C.; Wolvius, E.; Rivadeneira, F.; Àlvarez, G.; Blanc, V.; Kragt, L. Oral Microbiota of Adolescents with Dental Caries: A Systematic Review. Arch. Oral Biol. 2024, 161, 105933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-Mudallal, N.H.A.; Al-Jumaily, E.F.A.; Muhimen, N.A.A.; Al-Shaibany, A.A.-W. Isolation and Identification of Mutan’s Streptococci Bacteria from Human Dental Plaque Samples. J. Al-Nahrain Univ. Sci. 2008, 11, 98–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koneman, E.W.; Allen, S.D.; Janda, W.M.; Schrec kenberger, P.C.; Winn, W.C. Capítulo XII - Cocos Gram-Positivos, Parte II - Estreptococos, Enterococos e Bactérias ‘Similares a Estreptococos.’ In Color Atlas and Textbook of Diagnostic Microbiology; MEDSI: São Paulo, 2001; pp. 589–659. [Google Scholar]

- Lilienthal, B.; Reid, H. A New Laboratory Test for Acid Production in Saliva-Carbohydrate Mixtures and Its Comparison with the Lactobacillus Count and the Snyder Test. Arch. Oral Biol. 1959, 1, 125–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- R Core Team R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing 2023.

- Müller, L.K.; Jungbauer, G.; Jungbauer, R.; Wolf, M.; Deschner, J. Biofilm and Orthodontic Therapy. In; 2021; pp. 201–213.

- Pinelli, C.; Loffredo, L. de C.M.; Serra, M.C. Reprodutibilidade de Um Teste Microbiológico Para Estreptococos Do Grupo Mutans TT - Reproducibility of a Simplified Microbiological Test Formutans Streptococci. Pesqui. Odontológica Bras. 2000, 14.

- Scabar, L.F.; Amaral, R.C. do; Narvai, P.C.; Frazao, P. Validity of an Indirect Assessment Instrument on the Frequency of Brushing with Toothpaste. Revista Brasileira de Odontologia. Revista Brasileira de Odontologia. Rev. Bras. Odontol. 2016, 73, 39–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Çetinkaya, H.; Romaniuk, P. Relationship between Consumption of Soft and Alcoholic Drinks and Oral Health Problems. Cent. Eur. J. Public Health 2020, 28, 94–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).