1. Introduction

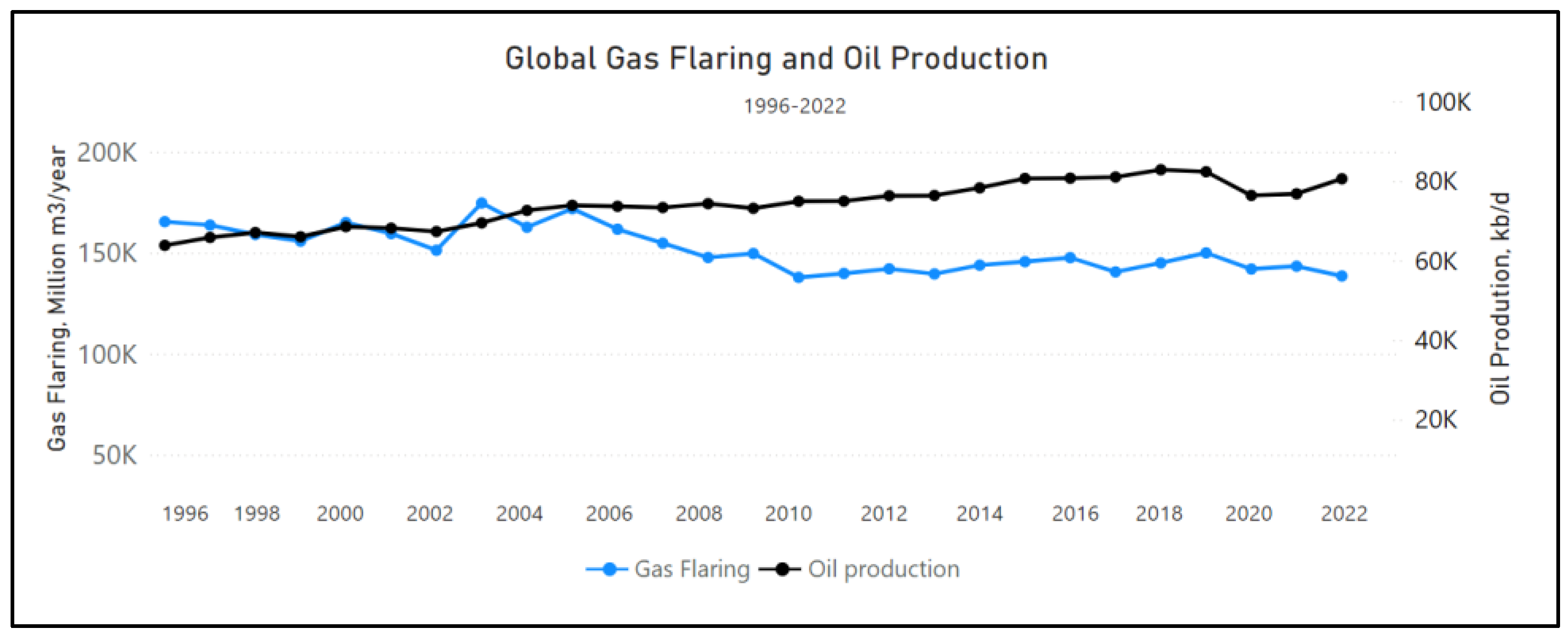

In petroleum industry, flares used to burn gases that cannot be processed or stored due to technical, economical and safety reasons. Generally, flares used to burn either large volumes of gases during start-up or shut-down process, or small amounts of gases during routine operation [

1]. Flares used not only in petroleum industry but also in other industries, such as; sewage digester, ammonia fertilizer and coal gasification [

1,

2]. Recently, the carbon emissions produced from the flares’ operation considered as a major challenge to climate change [

1,

3,

4]. The undesirable by-products from flares’ operation affect local population and the environment through noise, thermal radiation, smoke, and (NOx, SOx, soot, CO2 and CO) emissions. To reduce the impact of these by-products, flares design and operation should be according to standards [

5].

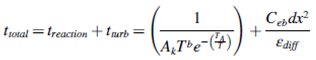

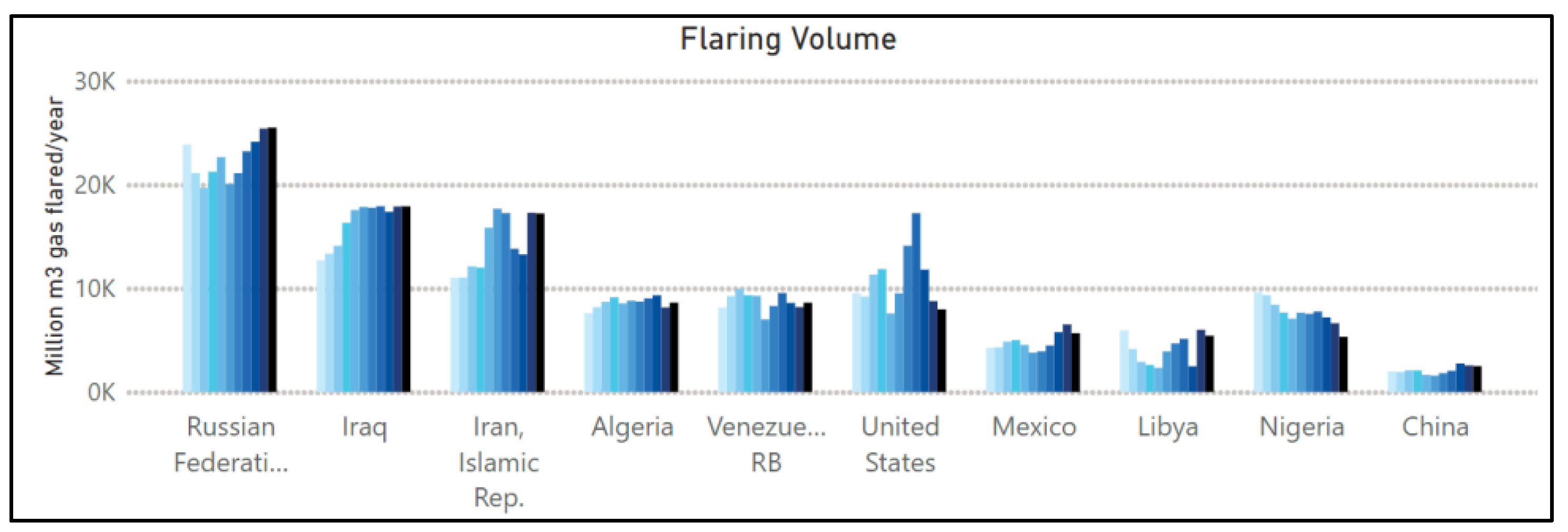

Generally, the top oil producing countries are the main contributors to the increase in the flaring volume due the increase in oil production rates.

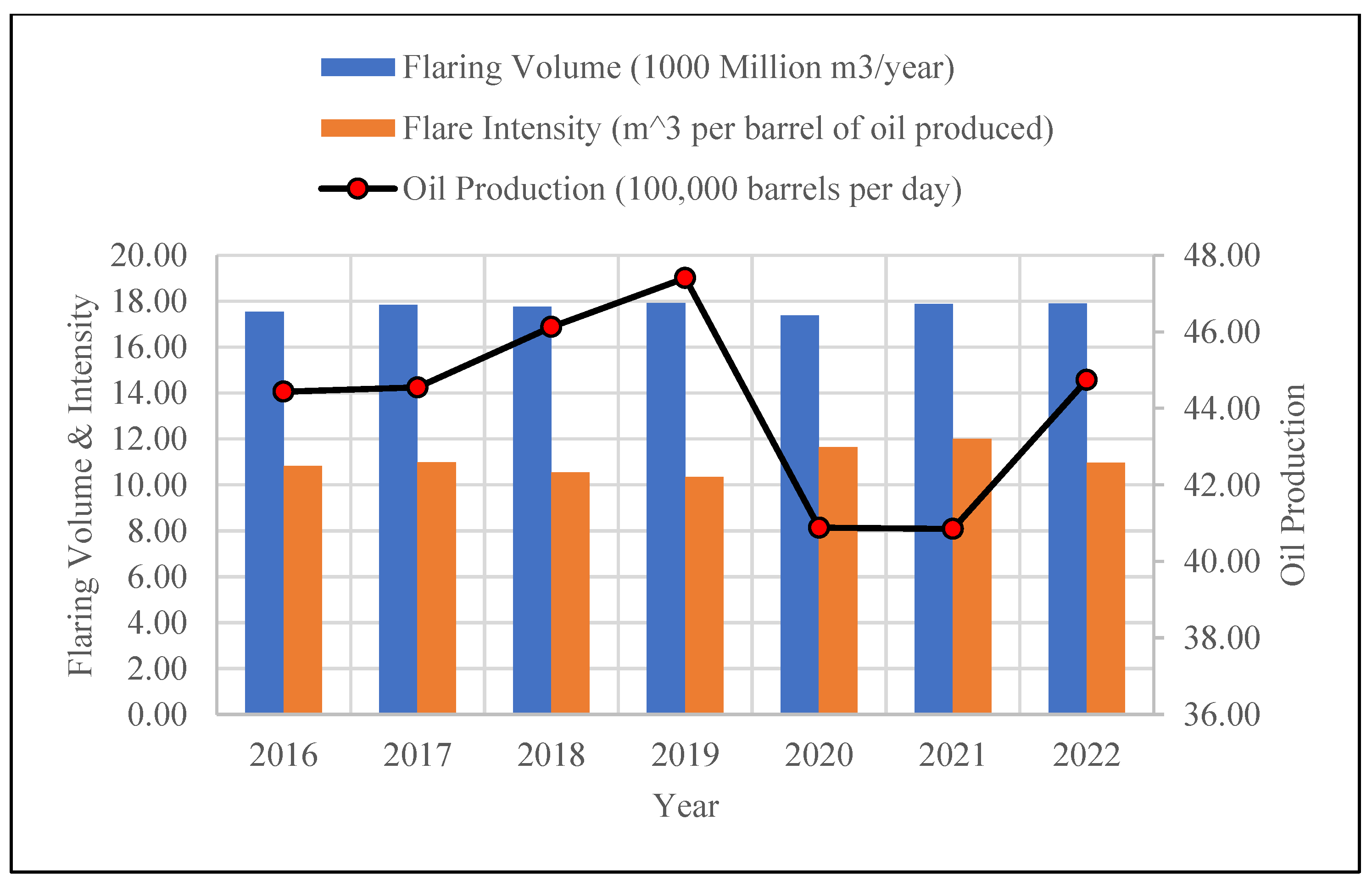

Figure 1 shows the rate of flaring volume due to oil production. Moreover,

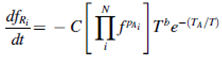

Figure 2 shows the gas flaring volume in the top 10 country between 2012 and 2022. According to these data, Iraq is the second largest flaring country after Russia. This is related directly to oil production rate and improper flare design and operation.

Figure 3 shows the correlation between oil production, flaring volume and intensity in Iraq between 2016 and 2022.

Flares’ performance usually measured using two important parameters; Combustion Efficiency (CE) and Destruction and Removal Efficiency (DRE) [7

12]. The first parameter, CE, measures the amount of CO2 produced due to complete combustion of the fuel, while, the second one, DRE, measures the amount of consumed original fuel converted to CO and CO

2 [

13,

16]. According to studies, a good DRE indicates a flame stability [13

17]. Moreover, factors like tip velocity and gas heating value affect flame stability. Usually, flares produce emissions under unstable operation conditions [

18,

19]. The combustion efficiency found also affected by flame lift-off when the tip velocity exceeds the burning velocity of the flare gas. USEPA recommended flare operation with tip velocity less than the maximum allowable tip velocity measured using tip diameter, the density of the flared vent gas and the air, combustion zone gas composition. Generally, the flame stability affects by factors such as; flammability limits, flame speed, cross wind speed and ignition temperature [19

21]. Field observations observed high combustion efficiencies at high flow conditions [

14,

22] while low combustion efficiencies below 98-99% noticed by some field measurements at low flow conditions [23

27]

. Studies showed that several factors cause low combustion efficiencies at low flow conditions. For example, the velocity of vent gas and flammability of the vent gas mixture [

28].

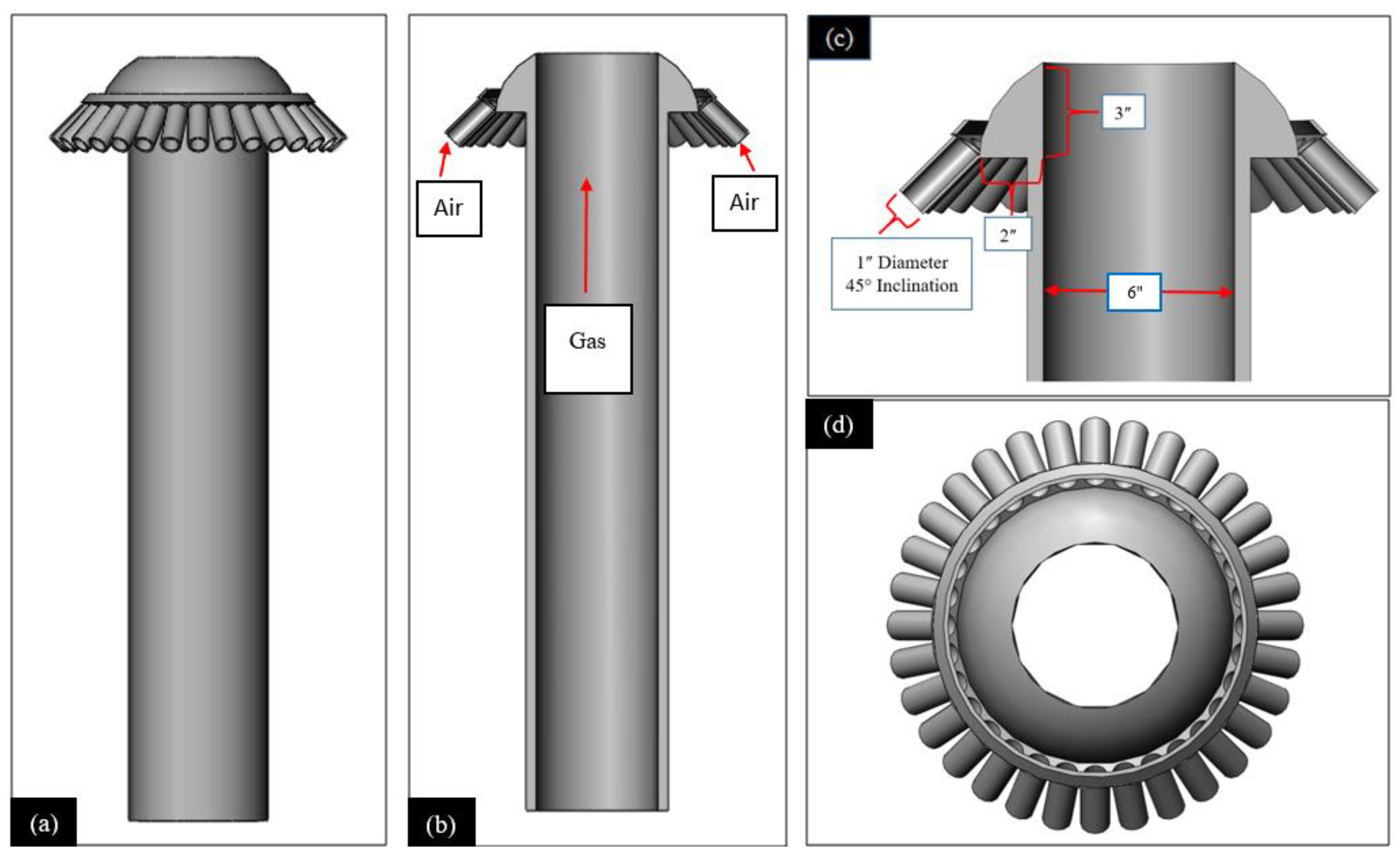

The current study tests a new air assisted flare tip design to enhance the performance by improving the CE and DRE, and reducing the soot formation and other greenhouse gases. The proposed idea includes 32 small pipes (1" ID) around the stack near the tip to inject air at high velocity toward the flame to achieve smokeless operation. The design also includes a curved surface (Coanda effect) in front of the air injectors to produce homogenous flow from all directions and entrain more air toward the flame.

Figure 4 shows the proposed new air assisted flare tip design. The effect of air on combustion studied by considering three air flow rates with the same gas flow rate. These tests considered stoichiometric air fuel ratio of the combustion. Moreover, to show the relation between flare gas flow rate and soot formation, three gas flow rates tested and monitored using utility flare. The highest gas flow rate used in the air assisted flare tests due the high soot formation and to show the effect of air on combustion more clearly.

The principle of injecting a jet into the crossflow is observed in many applications; for example, combustion equipment, mixing tanks, quenching systems, and drying systems. The distribution of flow in the domain of crossflow was reported affected by many factors including jet geometry, jet exhaust velocity, and the characteristics of the crossflow and injecting fluids [

29]. Both computational and experimental approaches have been used to study the effects of different factors on the flow properties of jet gas injected into crossflow [30

34]. The Coanda effect can be explained as “when a jet of fluid is passed over a curved surface, it bends to follow the surface, entraining large amounts of air as it does so". In other words, the Coanda effect can be defined as the tendency of a fluid to attach to a nearby surface and stay attached to it even if the surface curves away from the direction of the initial jet [35

38]. Coanda principle can be found in various natural and man-made examples (such as medicine, industrial processes, maritime technology, and aerodynamics) due to the improvement in turbulent levels and entrainment [

37,

38]. On the other hand, the major problem of the Coanda effect is the detachment of the jet flow due to high static pressure at the nozzle exit. Therefore, to prevent or delay this problem is through reducing the static pressure at the nozzle exhaust. For example, using a convergent-divergent nozzle can significantly lower the static pressure and solve the problem [

39,

40]. In petroleum industry, the Coanda principle has been used to improve flare operation by designing Coanda flares. Since the Coanda effect entrains large amounts of air, this kind of flare compared to other types produces higher combustion efficiency, better smokeless operation, and less thermal radiation. Furthermore, the Coanda principle has been also used in aircraft for thrust vectoring for short take-off and landing [40

43].

Figure 1.

Global Gas Flaring and Oil Production Between 1996 and 2022 [

5].

Figure 1.

Global Gas Flaring and Oil Production Between 1996 and 2022 [

5].

Figure 2.

Top Ten Flaring Countries (2012-2022) [

5].

Figure 2.

Top Ten Flaring Countries (2012-2022) [

5].

Figure 3.

Relation between flaring volume, flaring Intensity and oil production in Iraq (2016-2022) [

5].

Figure 3.

Relation between flaring volume, flaring Intensity and oil production in Iraq (2016-2022) [

5].

Figure 4.

The new air assisted flare tip design; (a) Side view, (b) Cross sectional view, (c) Tip cross sectional view, (d) Top view.

Figure 4.

The new air assisted flare tip design; (a) Side view, (b) Cross sectional view, (c) Tip cross sectional view, (d) Top view.

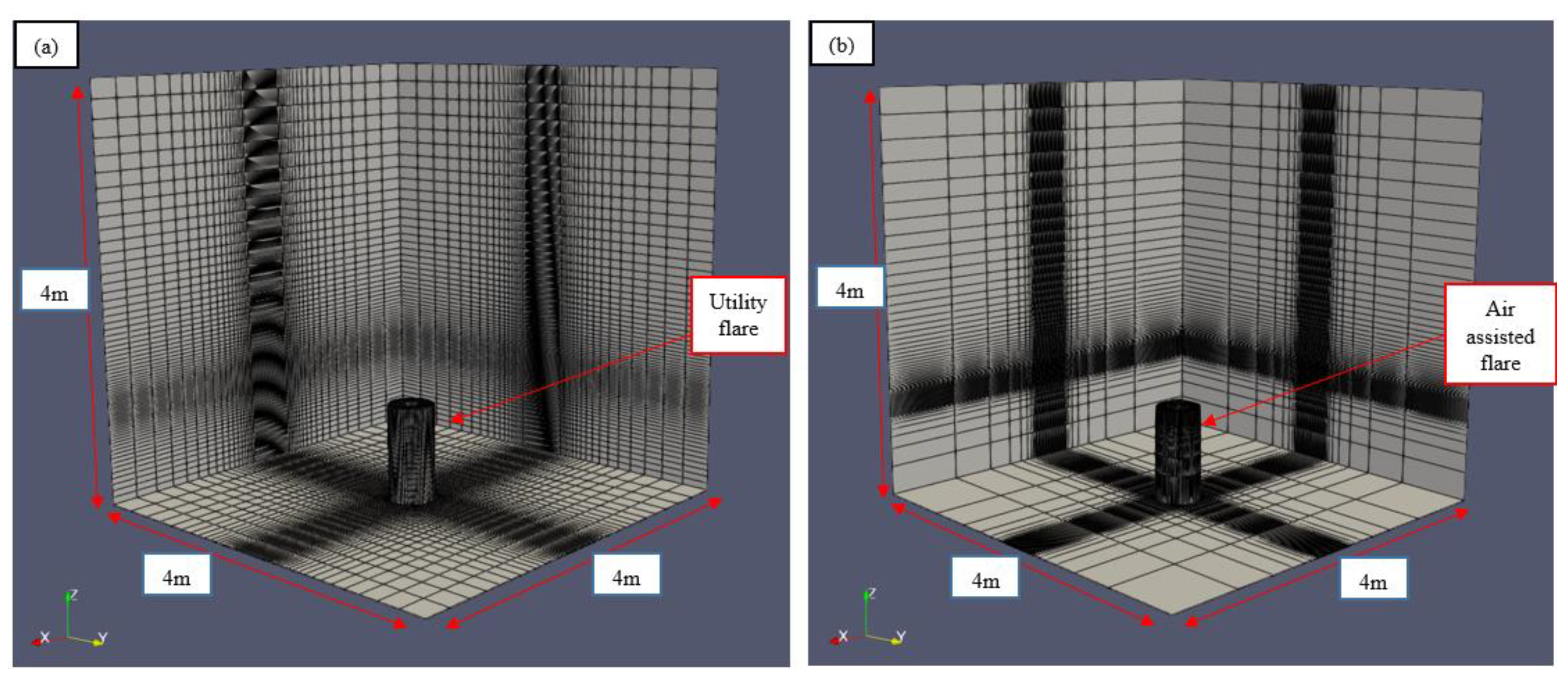

Figure 5.

CFD domain mesh and size; (a) Utility flare case, (b) Air assisted flare case.

Figure 5.

CFD domain mesh and size; (a) Utility flare case, (b) Air assisted flare case.

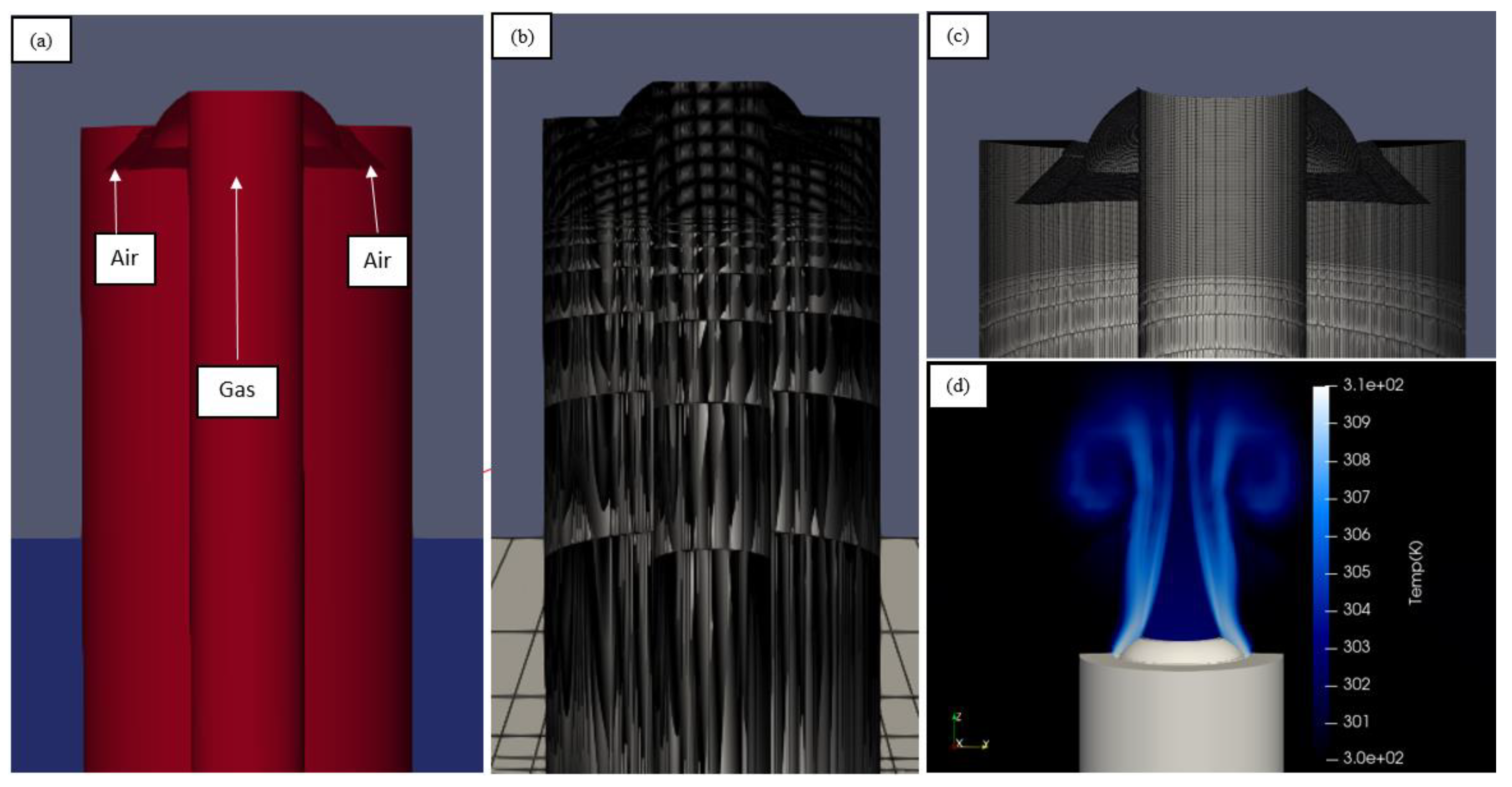

Figure 6.

Flare CFD model and mesh; (a) Cross sectional view, (b) Model meshing, (c) Tip meshing, (d) Cold flow (air flow).

Figure 6.

Flare CFD model and mesh; (a) Cross sectional view, (b) Model meshing, (c) Tip meshing, (d) Cold flow (air flow).

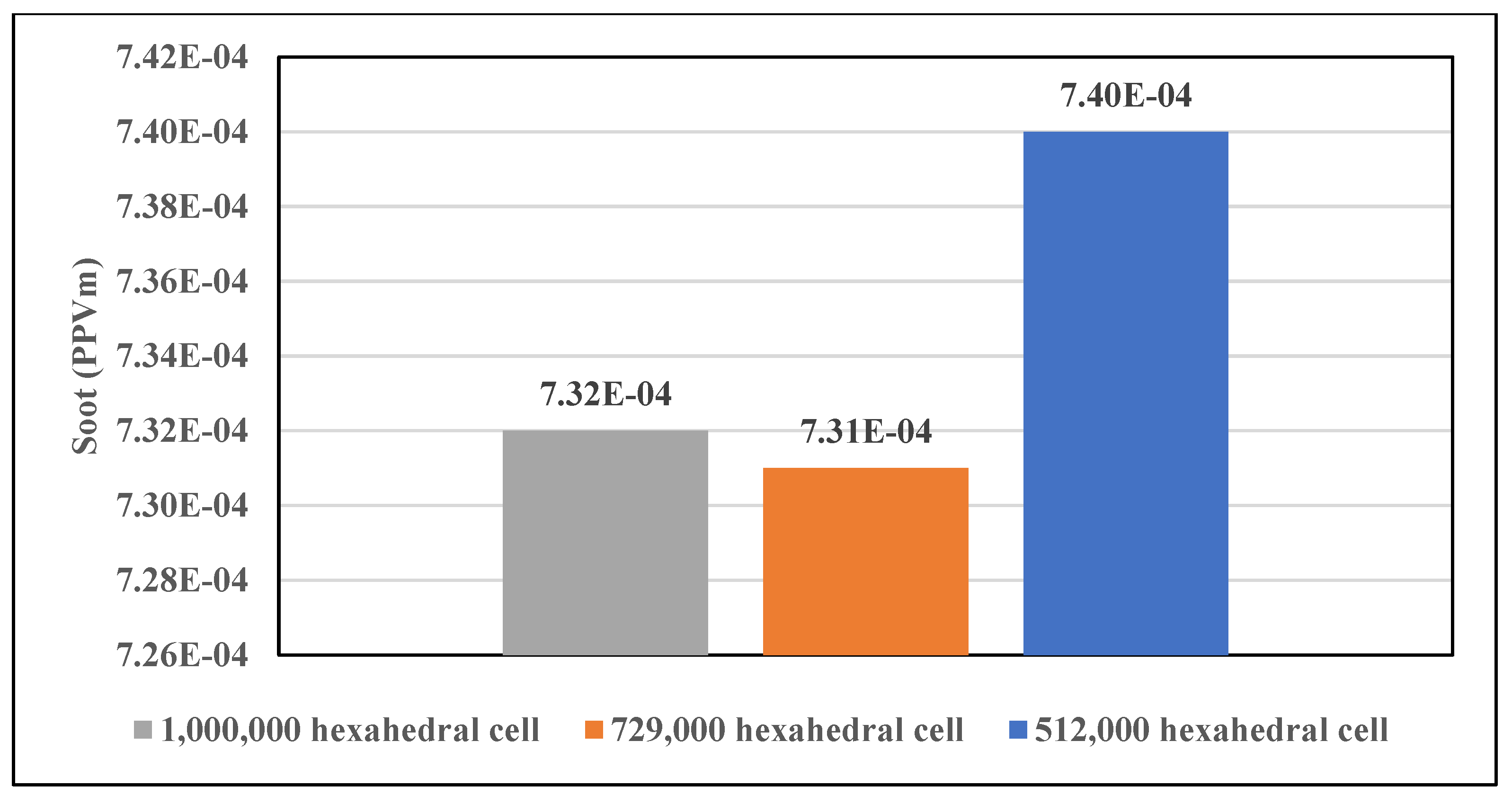

Figure 7.

Mesh independence study for air assisted flare case (0.42kg/min gas and 5.7kg/min air) at location 3.5m sampling point.

Figure 7.

Mesh independence study for air assisted flare case (0.42kg/min gas and 5.7kg/min air) at location 3.5m sampling point.

Figure 8.

Mesh independence study for utility flare case (0.42kg/min gas) at location 3.5m sampling point.

Figure 8.

Mesh independence study for utility flare case (0.42kg/min gas) at location 3.5m sampling point.

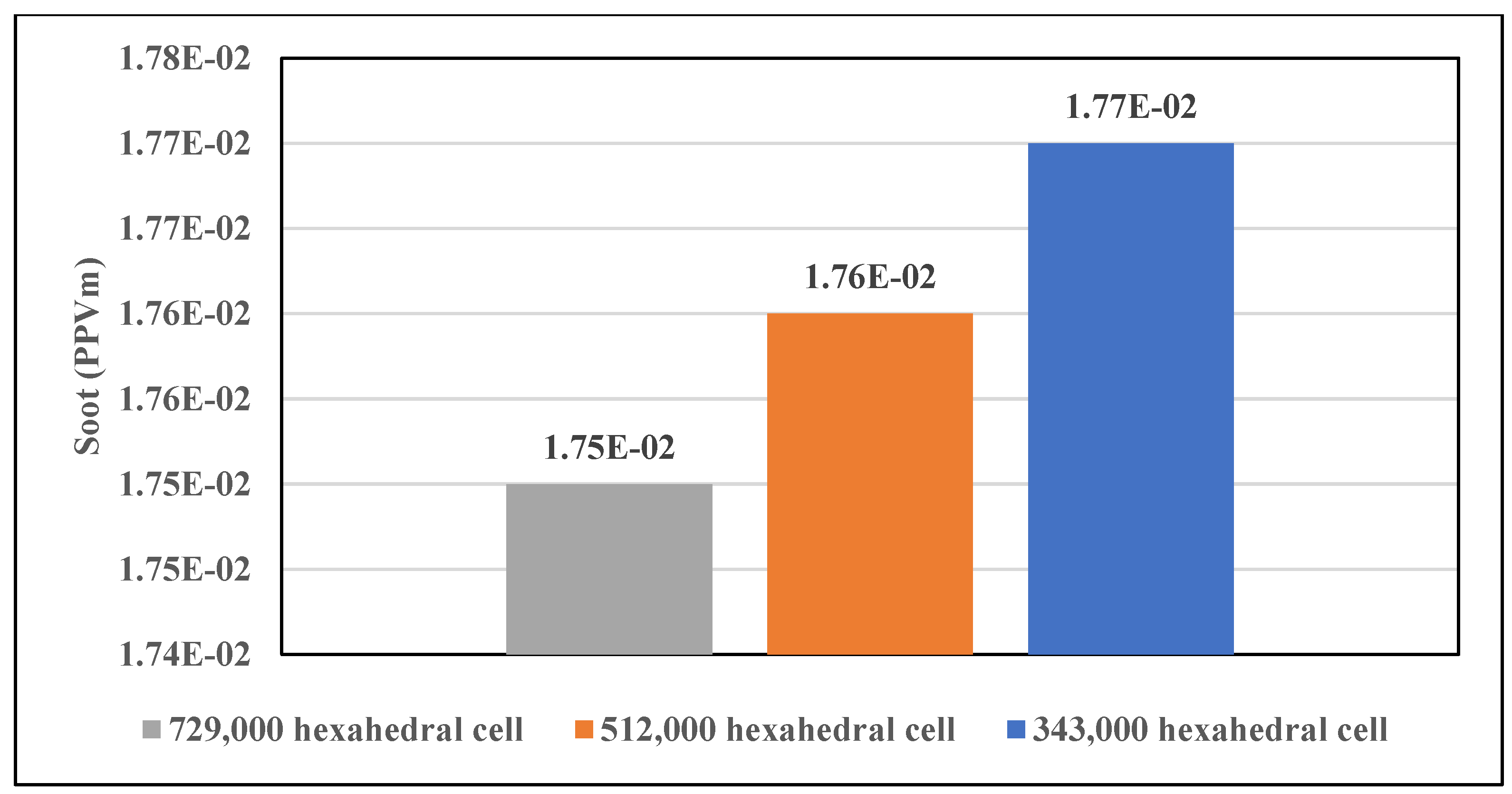

Figure 9.

Utility and air assisted flare Cases’ simulation stability.

Figure 9.

Utility and air assisted flare Cases’ simulation stability.

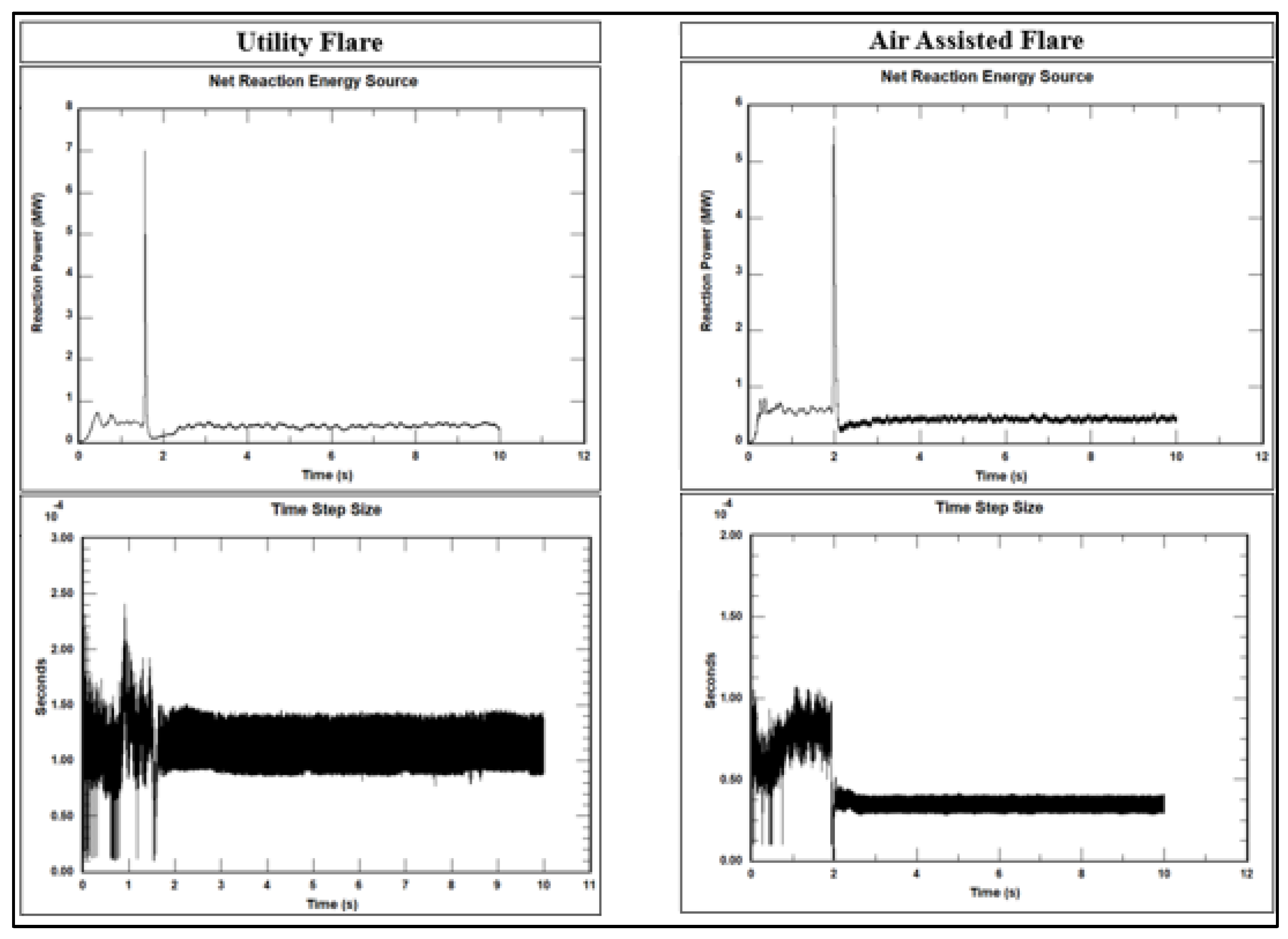

Figure 10.

Utility flare cases; (a) 0.3kg/min gas, (b) 0.36kg/min gas, (c) 0.42kg/min gas.

Figure 10.

Utility flare cases; (a) 0.3kg/min gas, (b) 0.36kg/min gas, (c) 0.42kg/min gas.

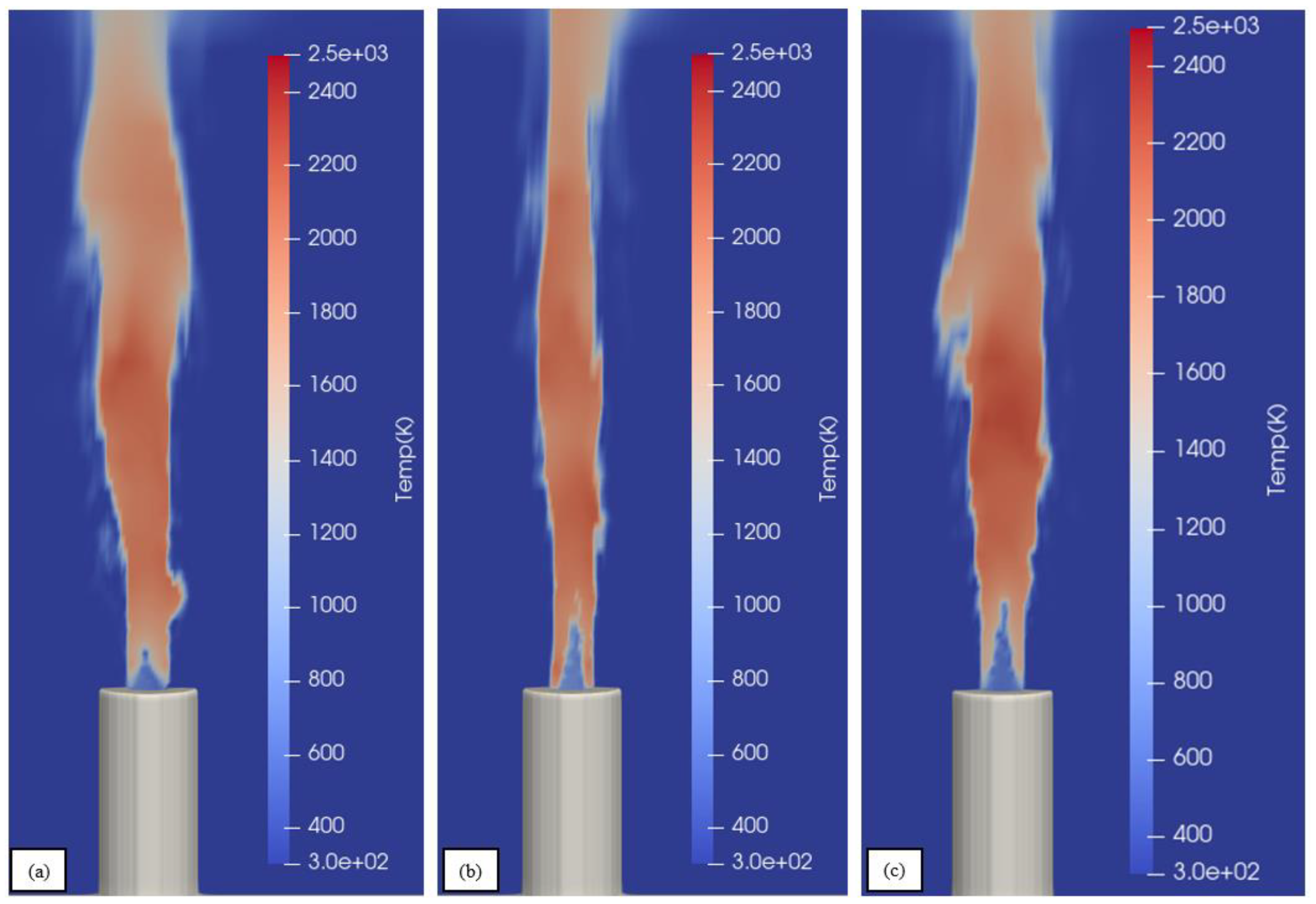

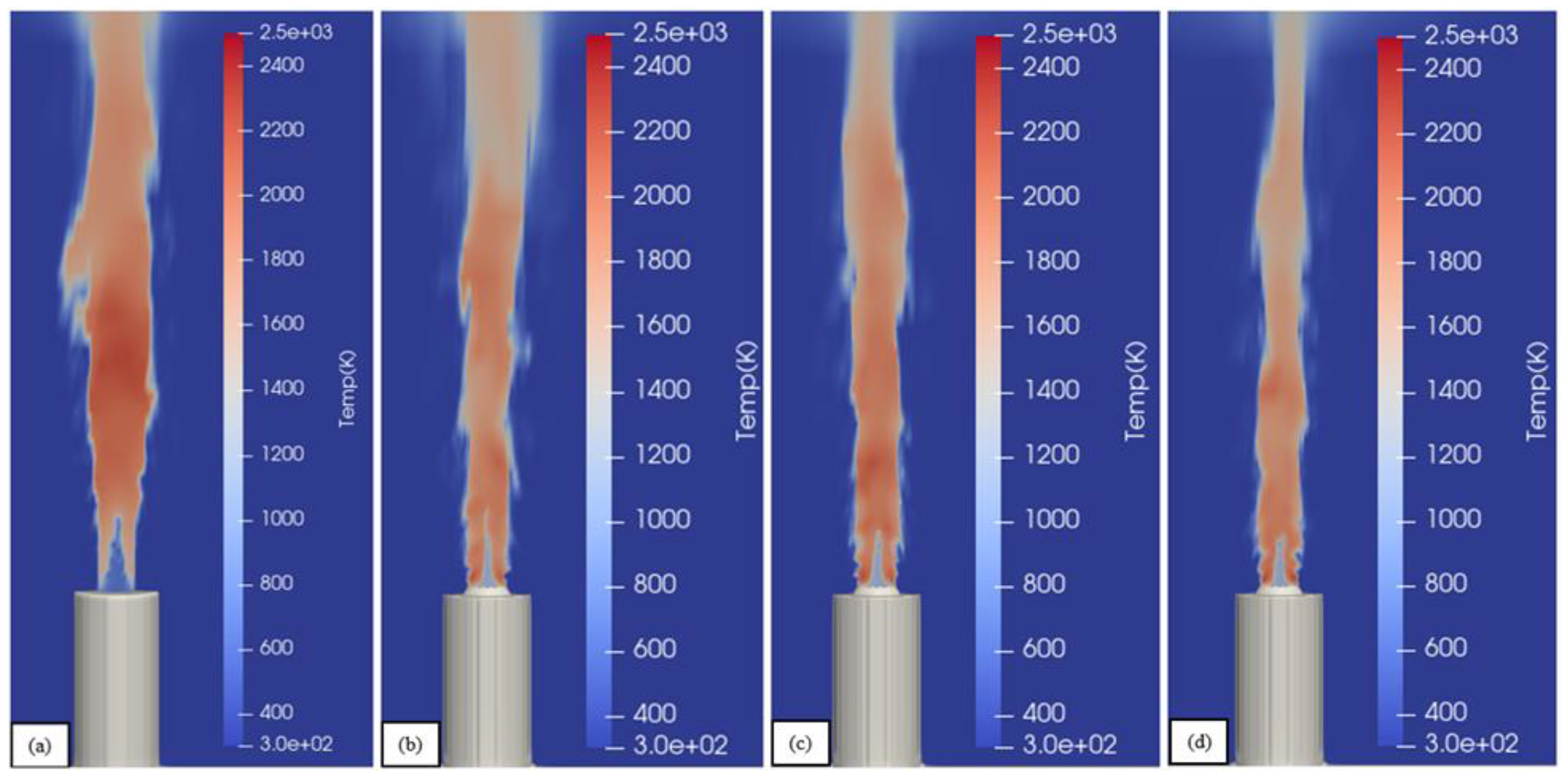

Figure 11.

Utility flare versus air assisted flare operation; (a) 0.42kg/min gas and 0kg/min air, (b) 0.42kg/min gas and 5.7kg/min air, (c) 0.42kg/min gas and 6.6kg/min air, (d) 0.42kg/min gas and 8.2kg/min air.

Figure 11.

Utility flare versus air assisted flare operation; (a) 0.42kg/min gas and 0kg/min air, (b) 0.42kg/min gas and 5.7kg/min air, (c) 0.42kg/min gas and 6.6kg/min air, (d) 0.42kg/min gas and 8.2kg/min air.

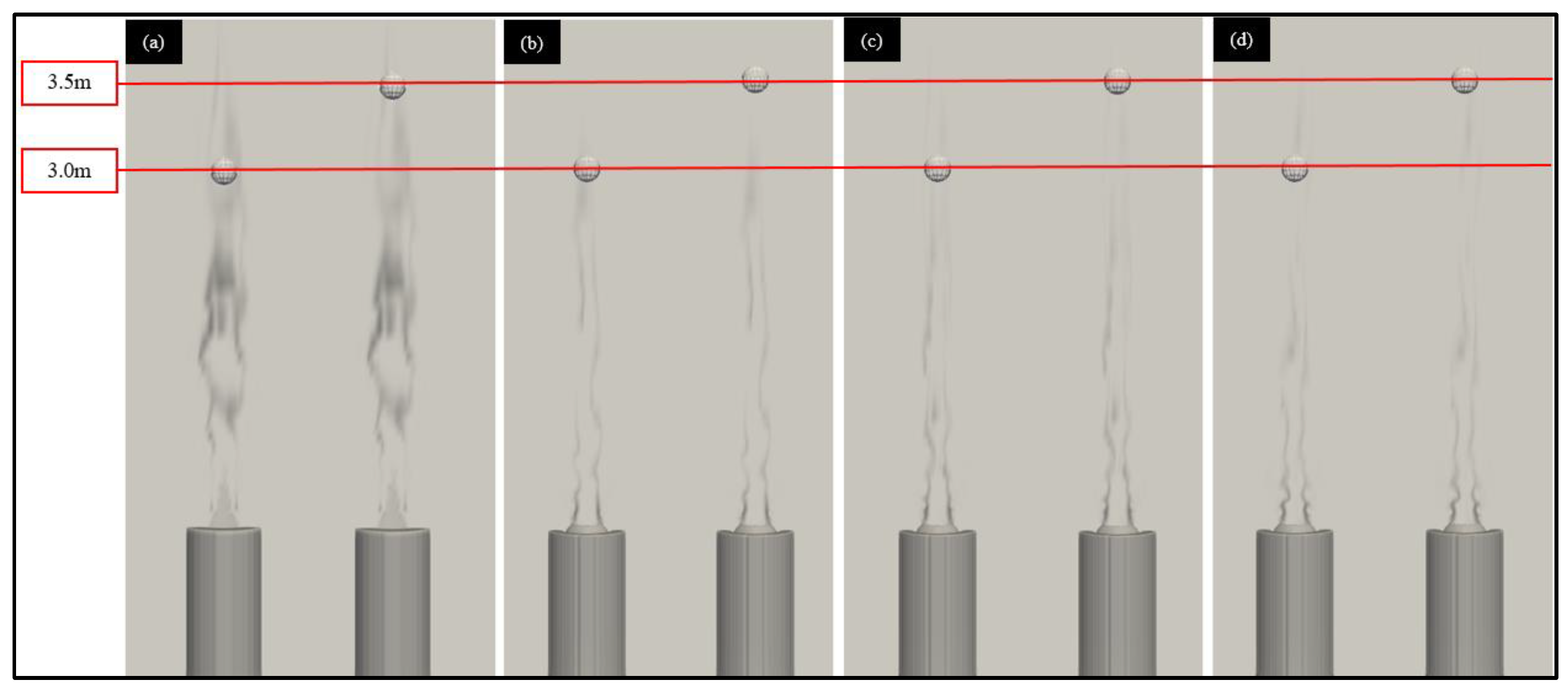

Figure 12.

Data sampling locations: (a) 0.42kg/min gas and 0kg/min air, (b) 0.42kg/min gas and 5.7kg/min air, (c) 0.42kg/min gas and 6.6kg/min air, (d) 0.42kg/min gas and 8.2kg/min air.

Figure 12.

Data sampling locations: (a) 0.42kg/min gas and 0kg/min air, (b) 0.42kg/min gas and 5.7kg/min air, (c) 0.42kg/min gas and 6.6kg/min air, (d) 0.42kg/min gas and 8.2kg/min air.

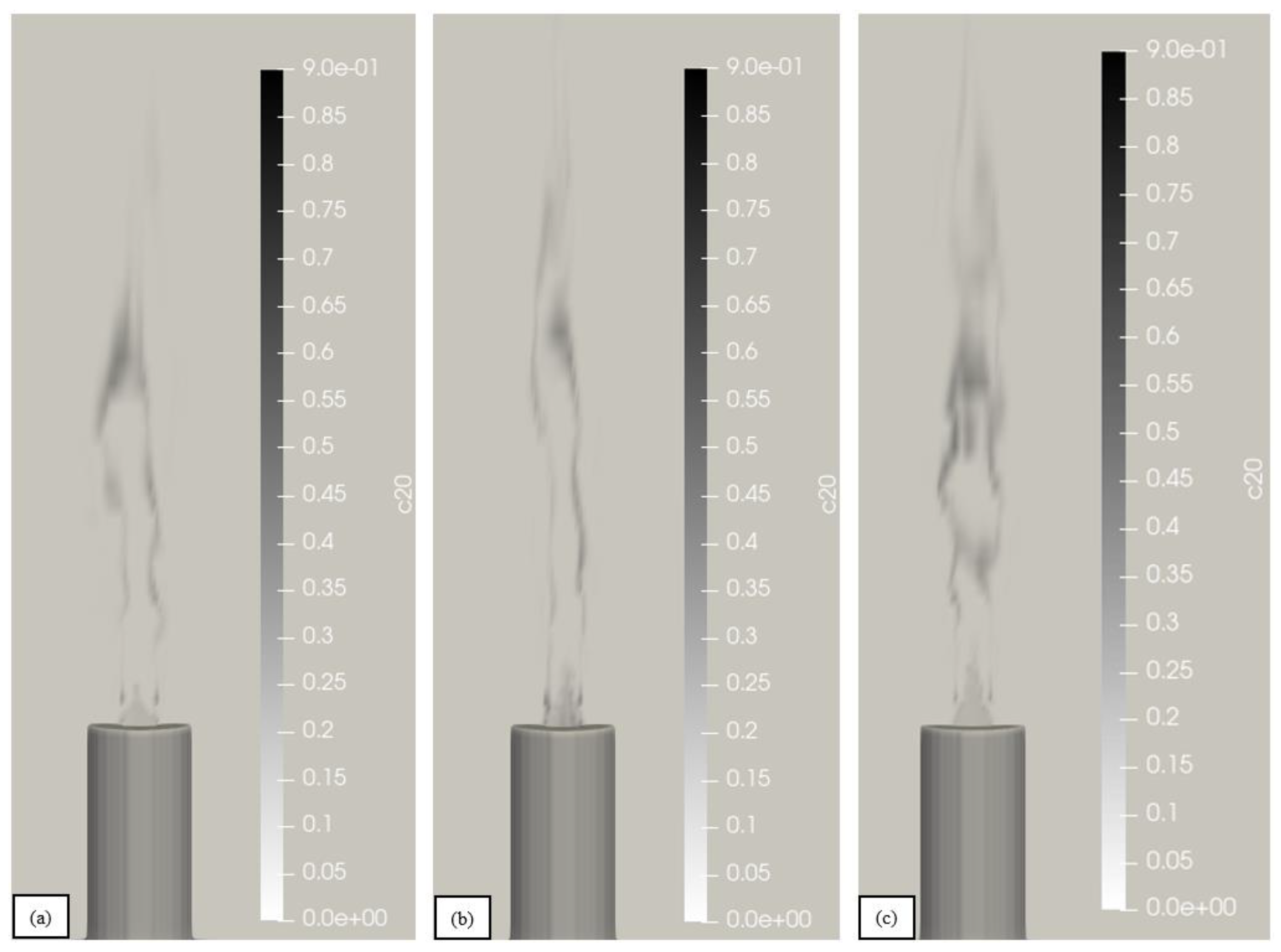

Figure 13.

Utility flare soot formation; (a) 0.3kg/min gas, (b) 0.36kg/min gas, (c) 0.42kg/min gas.

Figure 13.

Utility flare soot formation; (a) 0.3kg/min gas, (b) 0.36kg/min gas, (c) 0.42kg/min gas.

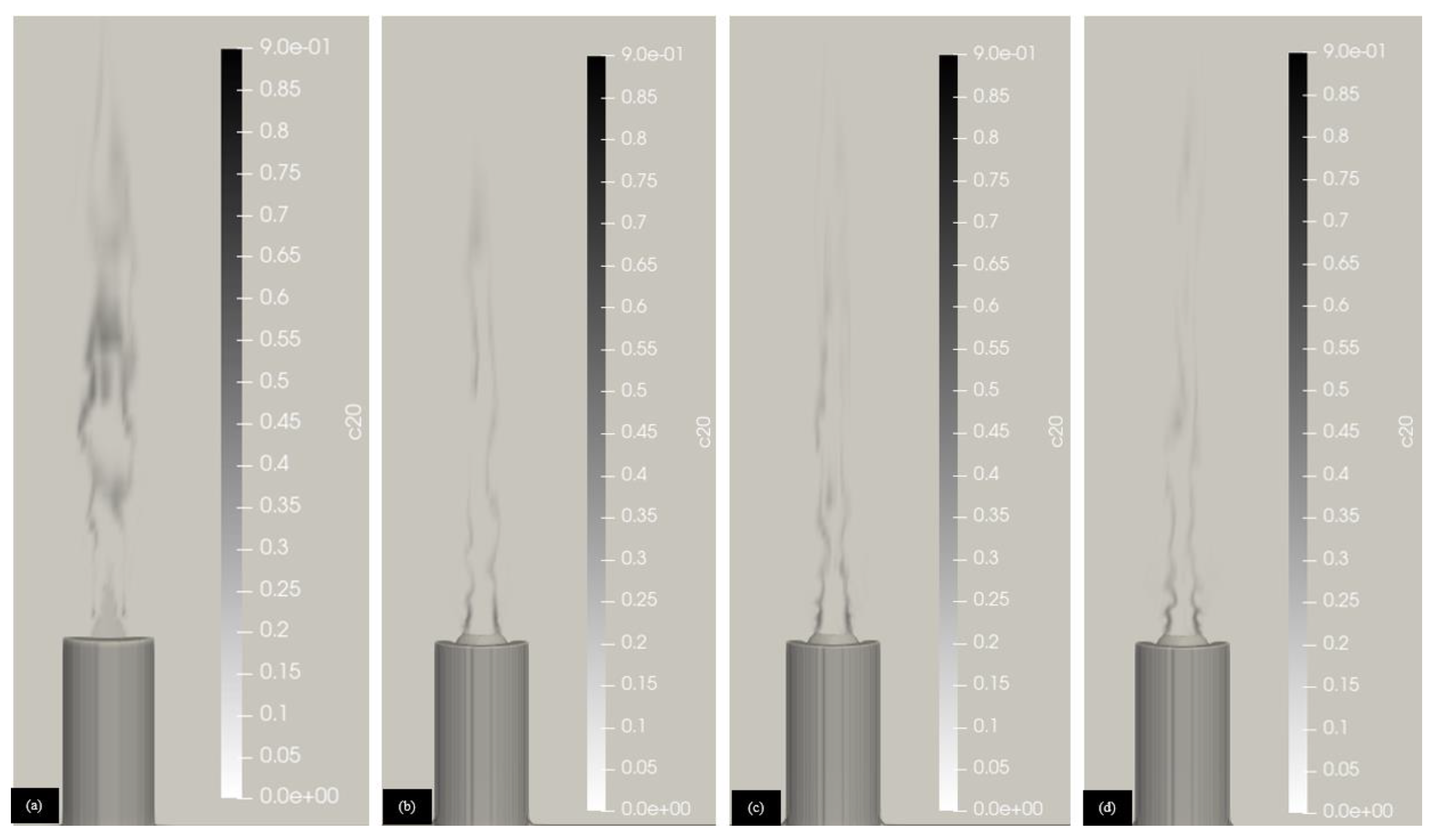

Figure 14.

Utility flare versus air assisted flare soot formation; (a) 0.42kg/min gas and 0kg/min air, (b) 0.42kg/min gas and 5.7kg/min air, (c) 0.42kg/min gas and 6.6kg/min air, (d) 0.42kg/min gas and 8.2kg/min air.

Figure 14.

Utility flare versus air assisted flare soot formation; (a) 0.42kg/min gas and 0kg/min air, (b) 0.42kg/min gas and 5.7kg/min air, (c) 0.42kg/min gas and 6.6kg/min air, (d) 0.42kg/min gas and 8.2kg/min air.

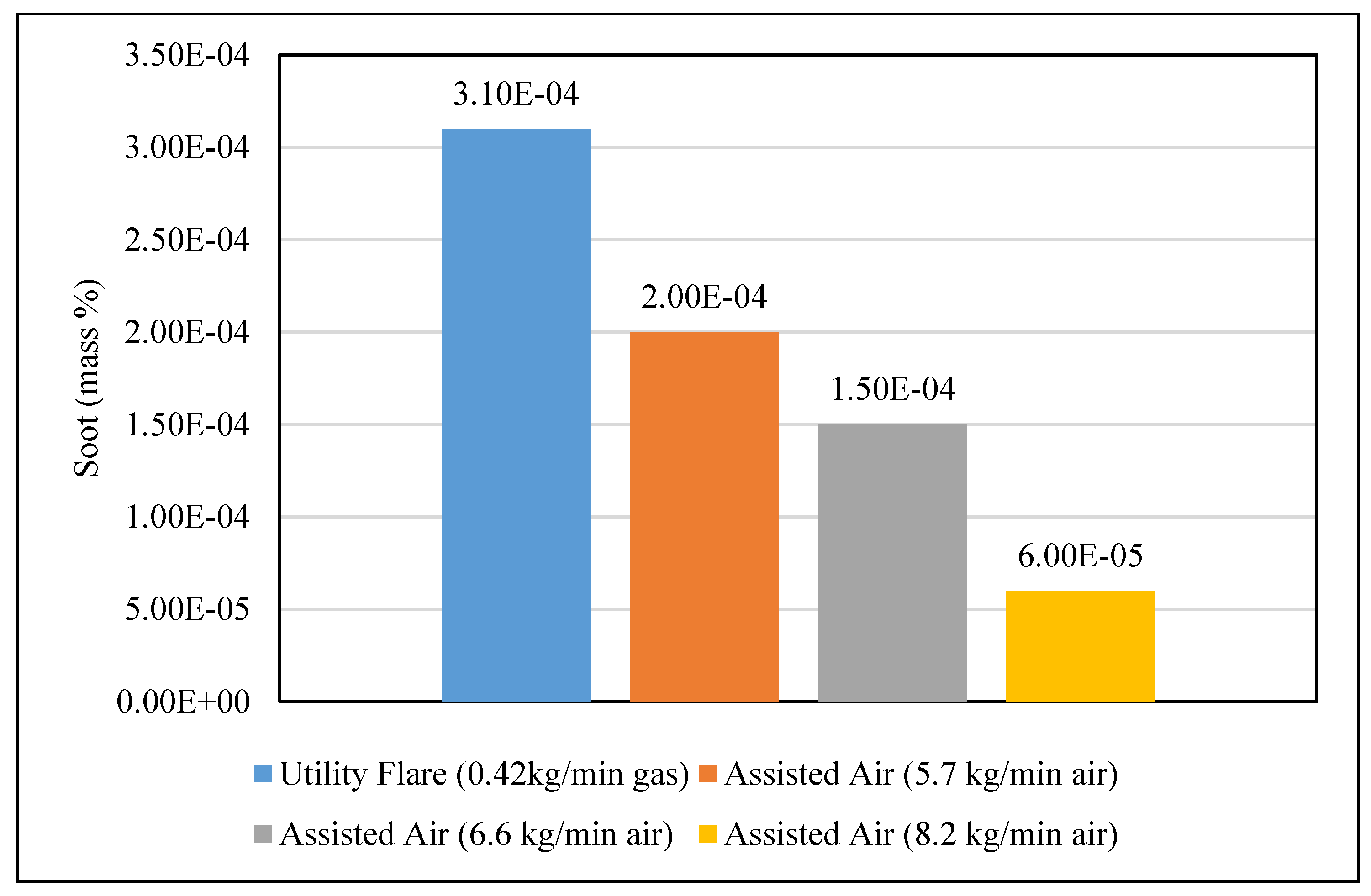

Figure 15.

Soot formation (mass %) of the utility and air assisted cases at sampling location 0m x-axis, 0m y-axis, 3m z- axis.

Figure 15.

Soot formation (mass %) of the utility and air assisted cases at sampling location 0m x-axis, 0m y-axis, 3m z- axis.

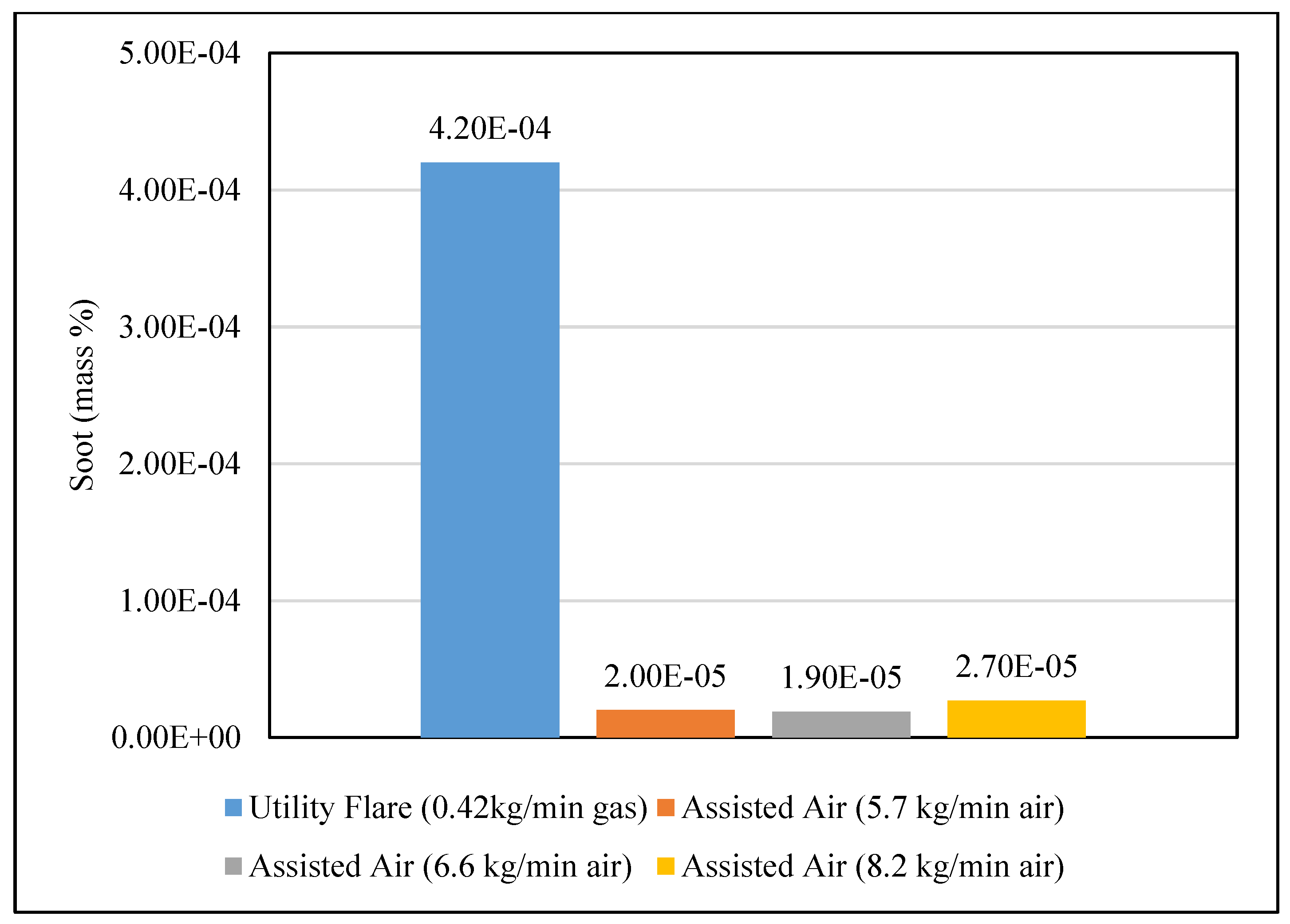

Figure 16.

Soot formation (mass %) of the utility and air assisted cases at sampling location 0m x-axis, 0m y-axis, 3.5m z-axis.

Figure 16.

Soot formation (mass %) of the utility and air assisted cases at sampling location 0m x-axis, 0m y-axis, 3.5m z-axis.

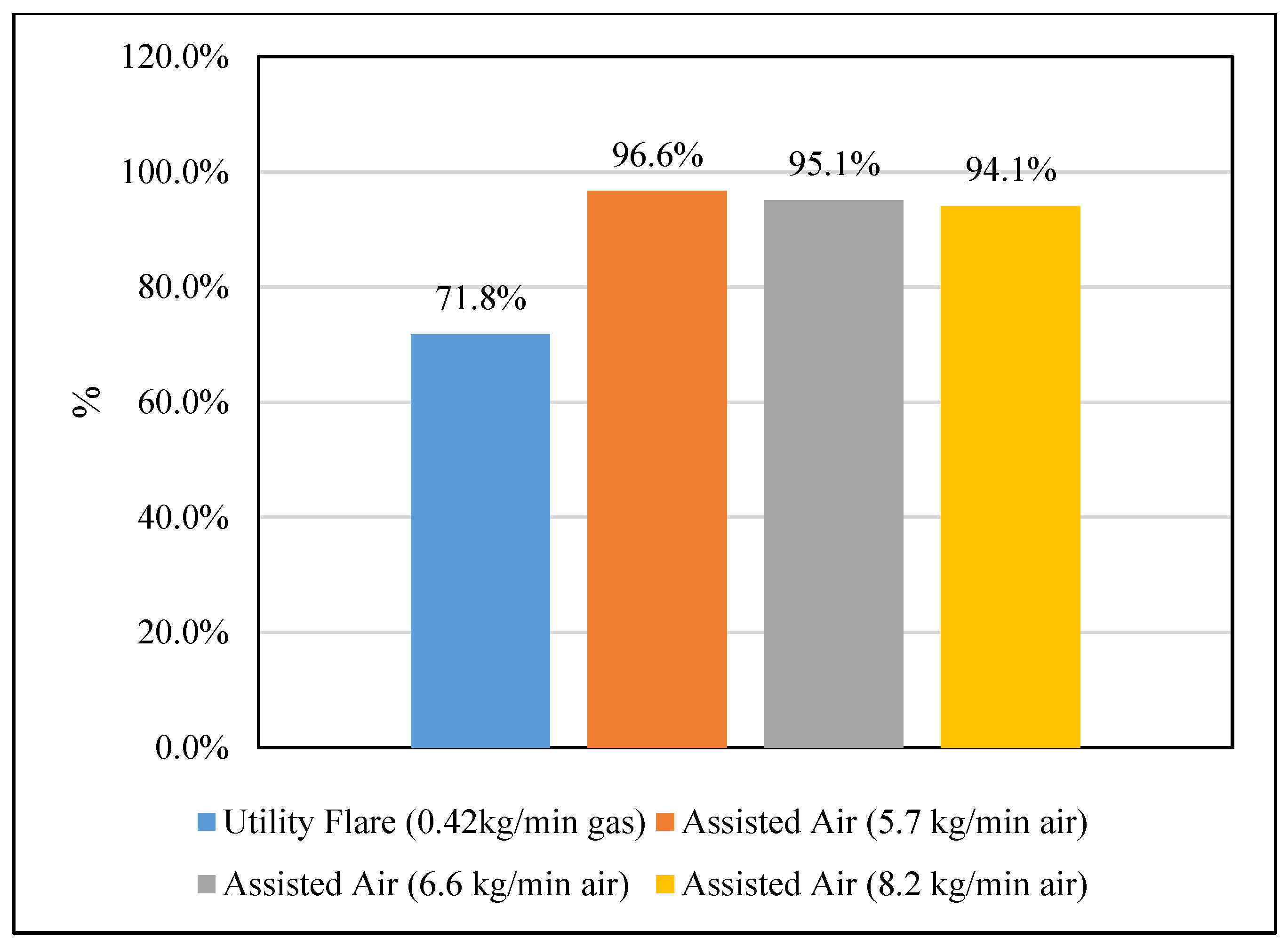

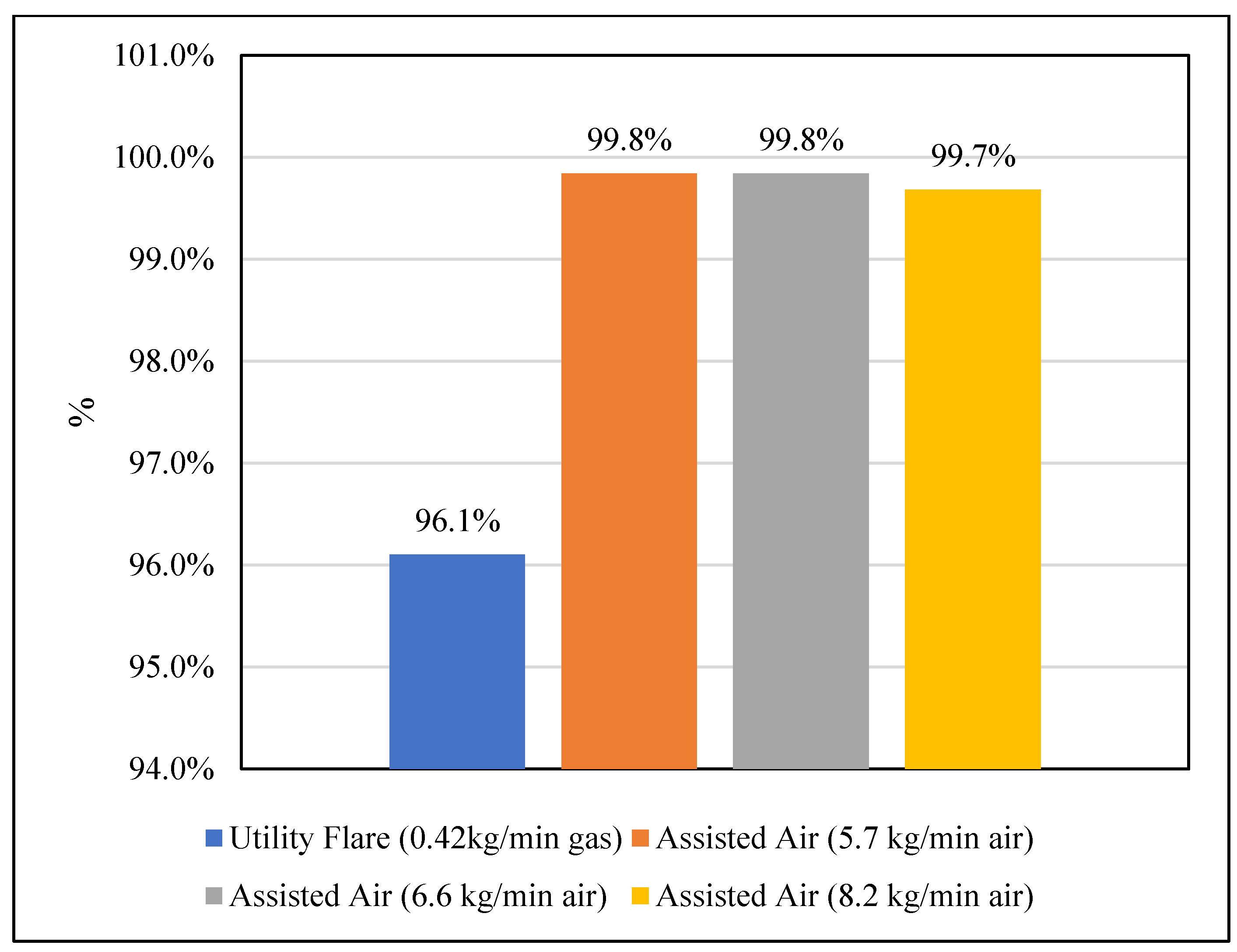

Figure 17.

CE of the utility and air assisted flare at sampling location 0m x-axis, 0m y-axis, 3m z-axis.

Figure 17.

CE of the utility and air assisted flare at sampling location 0m x-axis, 0m y-axis, 3m z-axis.

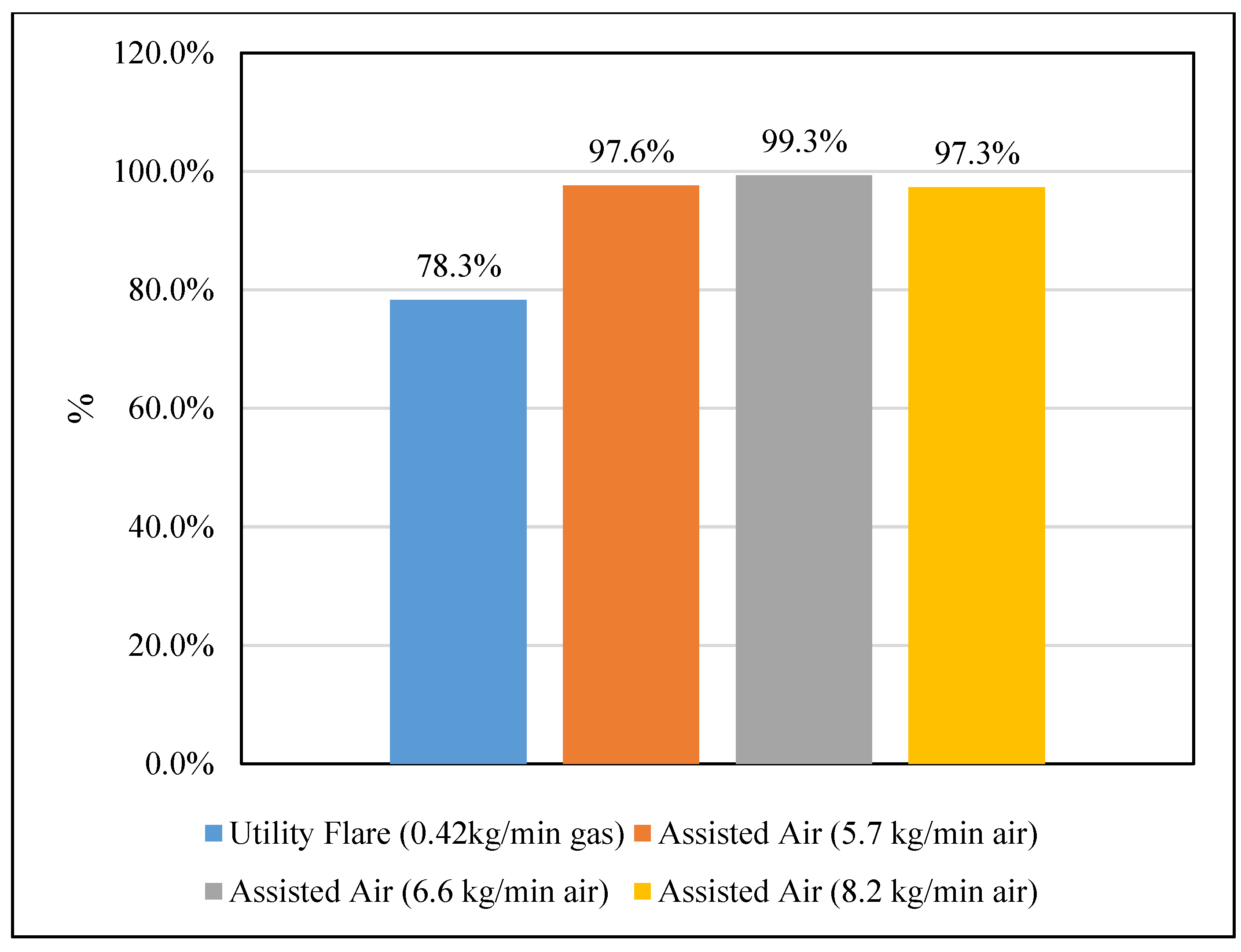

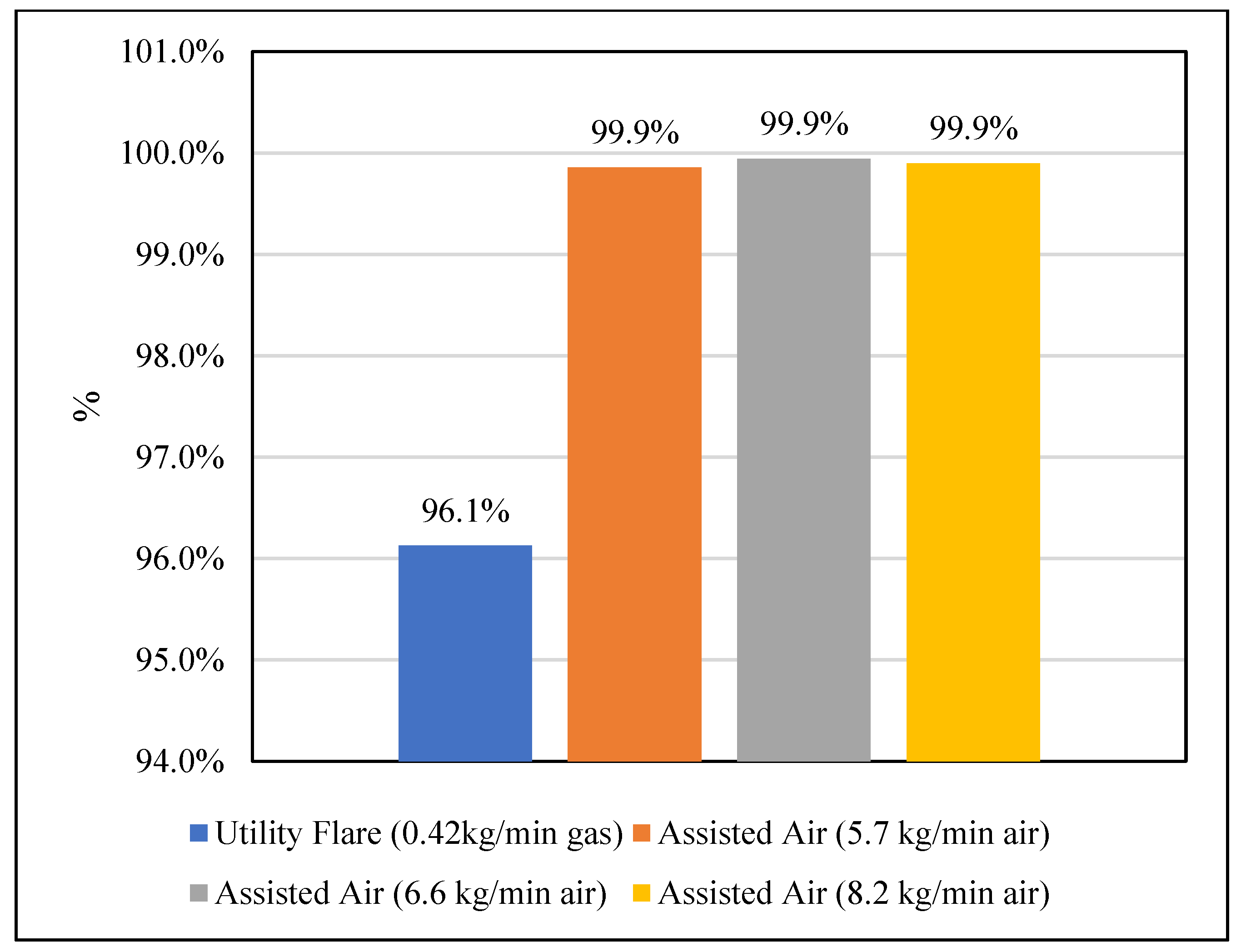

Figure 18.

CE of the utility and air assisted flares at sampling location 0m x-axis, 0m y-axis, 3.5m z-axis.

Figure 18.

CE of the utility and air assisted flares at sampling location 0m x-axis, 0m y-axis, 3.5m z-axis.

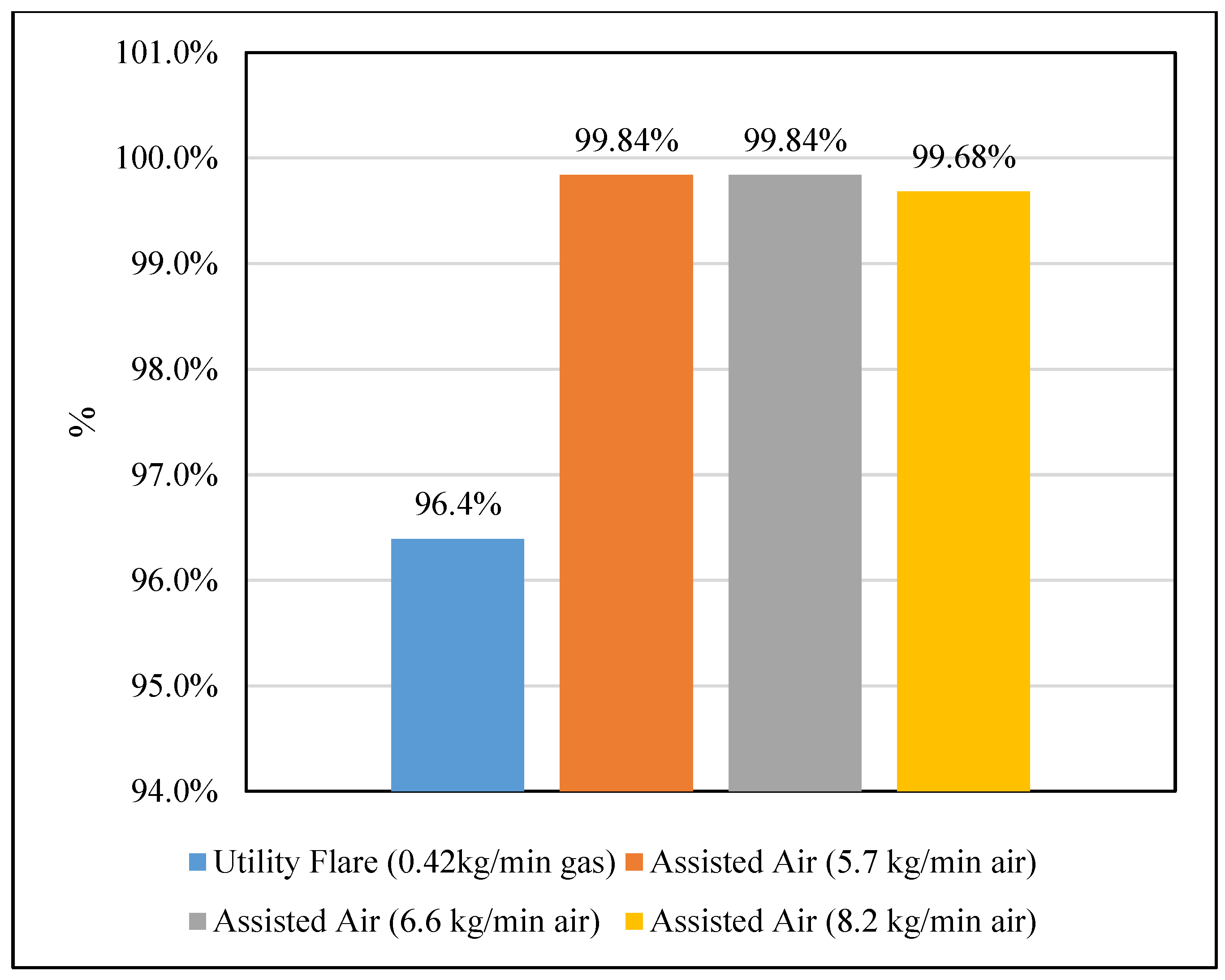

Figure 19.

DRE of the utility and air assisted flare at sampling location 0m x-axis, 0m y-axis, 3m z-axis.

Figure 19.

DRE of the utility and air assisted flare at sampling location 0m x-axis, 0m y-axis, 3m z-axis.

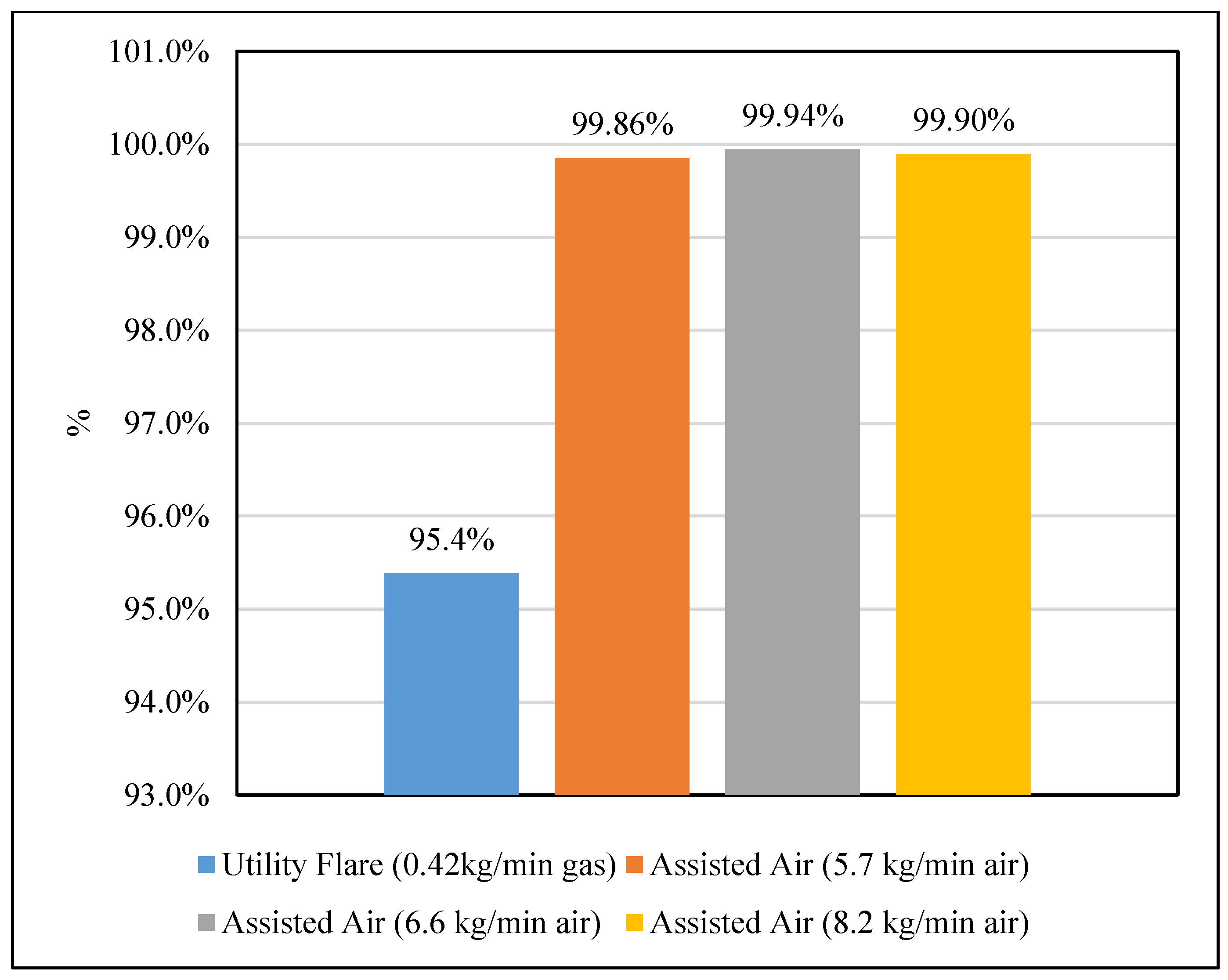

Figure 20.

DRE of the utility and air assisted flare at sampling location 0m x-axis, 0m y-axis, 3.5m z-axis.

Figure 20.

DRE of the utility and air assisted flare at sampling location 0m x-axis, 0m y-axis, 3.5m z-axis.

Figure 21.

DRECH4 of the utility and air assisted flare at sampling location 0m x-axis, 0m y-axis, 3m z-axis.

Figure 21.

DRECH4 of the utility and air assisted flare at sampling location 0m x-axis, 0m y-axis, 3m z-axis.

Figure 22.

DRECH4 of the Utility and air assisted flare at sampling location 0m x-axis, 0m y-axis, 3.5m z-axis.

Figure 22.

DRECH4 of the Utility and air assisted flare at sampling location 0m x-axis, 0m y-axis, 3.5m z-axis.

Table 1.

Case study gas composition.

Table 1.

Case study gas composition.

| Basis = 100 kgmole/h |

|---|

| Components |

Mole (%) |

Kg mole |

MWt |

Kg |

Mass (%) |

| C1 |

83.34 |

83.34 |

16 |

1333.44 |

0.693 |

| C2 |

9.501 |

9.501 |

30 |

285.03 |

0.148 |

| C3 |

3.391 |

3.391 |

44 |

149.204 |

0.078 |

| C6+ |

0.232 |

0.232 |

86 |

19.952 |

0.010 |

| CO2 |

1.713 |

1.713 |

44 |

75.372 |

0.039 |

| H2S |

1.816 |

1.816 |

34 |

61.744 |

0.032 |

| N2 |

0.007 |

0.007 |

28 |

0.196 |

0.000 |

| Total |

100 |

100.00 |

|

1925 |

1 |

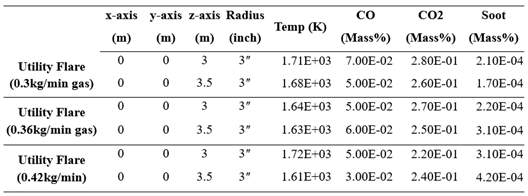

Table 2.

Utility flare cases average temp, CO, CO2 and soot at both sampling locations.

Table 2.

Utility flare cases average temp, CO, CO2 and soot at both sampling locations.

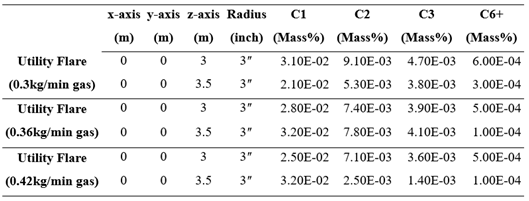

Table 3.

Utility flare cases average C1, C2, C3 and C6+ at both sampling locations.

Table 3.

Utility flare cases average C1, C2, C3 and C6+ at both sampling locations.

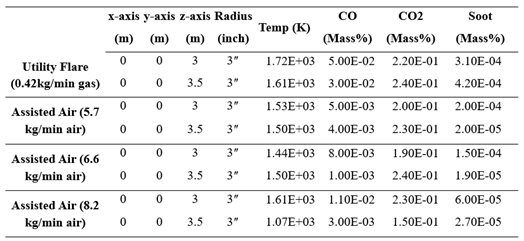

Table 4.

Utility and air assisted flare average temp, CO, CO2 and soot at both sampling locations.

Table 4.

Utility and air assisted flare average temp, CO, CO2 and soot at both sampling locations.

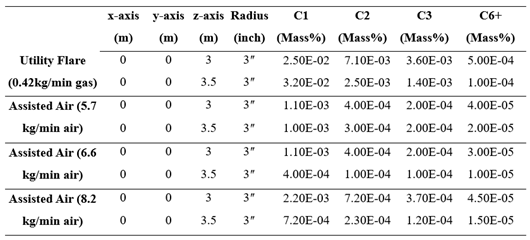

Table 5.

Utility and air assisted flare average C1, C2, C3 and C6+ at both sampling locations.

Table 5.

Utility and air assisted flare average C1, C2, C3 and C6+ at both sampling locations.

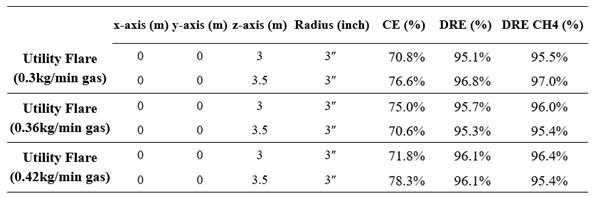

Table 6.

Combustion Efficiency (CE) & Destruction and Removal Efficiency (DRE) of the utility flare cases.

Table 6.

Combustion Efficiency (CE) & Destruction and Removal Efficiency (DRE) of the utility flare cases.

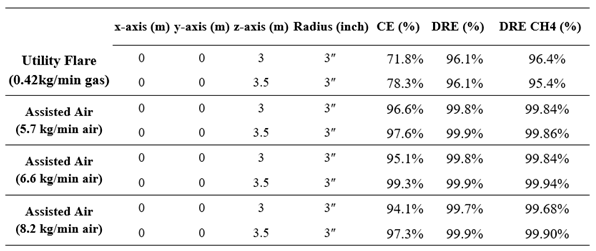

Table 7.

Combustion Efficiency (CE) & Destruction and Removal Efficiency (DRE) of the utility and air assisted flares.

Table 7.

Combustion Efficiency (CE) & Destruction and Removal Efficiency (DRE) of the utility and air assisted flares.

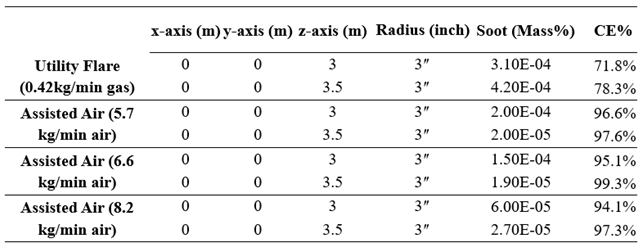

Table 8.

Soot formation and CE of the utility and air assisted flares.

Table 8.

Soot formation and CE of the utility and air assisted flares.

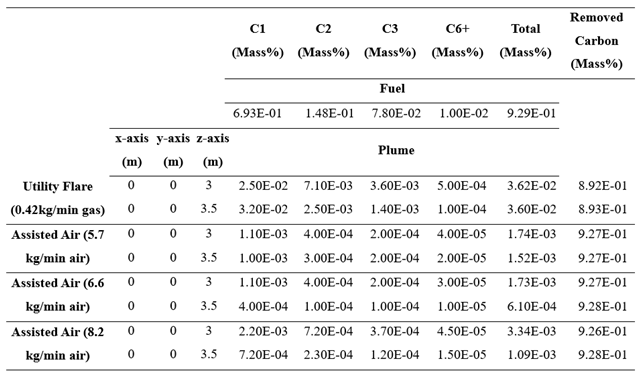

Table 9.

Fuel carbon balance for the utility and air assisted flares.

Table 9.

Fuel carbon balance for the utility and air assisted flares.