1. Introduction

In recent decades, there has been an increasing emphasis on the need to capture patients’ perspectives on healthcare service quality (Leatherman et al. 2010; Almeida et al., 2015; Mattarozzi et al. 2017; Jessup et al. 2020). It has been widely recognized that putting the patient’s needs at the centre enhances the patient’s experiences of service use and that accommodating preferences means significantly affecting service quality (Stewart 2001; Doyle et al. 2013; Almeida et al. 2015; Schroeder et al. 2022).

Previous research highlights how neglecting patients’ perspectives can lead to various negative outcomes: discontinuity of care, compromise of patient safety, patient dissatisfaction and inefficient use of valuable resources, both in unnecessary investigations and physician worktime as well as economic consequence (Vermeir et al. 2015). Conversely, valuing patients’ perspective can lead to better health outcomes: improved control of the chronic condition, decreased hospitalizations and readmissions (Simpson and House 2002), improved emotional and physical health status (Haskard et al. 2009), greater satisfaction with the overall quality of care (Crawford et al. 2002; Castro et al. 2016) and improved quality of health care system (Gleeson et al. 2016).

The emphasis on the need to capture patients’ perspectives is also motivated by a different view of the patients: they are no longer identified with their disease and are no longer viewed as passive recipients, but recognized as a bio-psycho-social unit, characterised by emotions, values, expectations that inevitably mediate their patterns of use and evaluation of health services (Kaba and Sooriakumaran 2007; Gluyas 2015; Langberg et al. 2019; Venuleo et al. 2023). This means that even in the most traditional model of medical practice — where patients are expected to be instructed by clinicians and to follow their suggestions — health outcomes (good and bad) are coproduced (Batalden et al. 2016). They depend, for instance, on how clinician and patient communicate effectively, develop a shared understanding of the problem and generate a mutually acceptable evaluation and management plan.

On the other hand, the interactions between professionals and patients does not happen in a social vacuum. The healthcare system (its structure and its functions) and the large-scale social forces at work in the wider community support and constraints theses interactions; the ability of professionals and patients to work together to co-produce value shift across time, setting and circumstance (Batalden et al. 2016). Just think about the COVID-19 outbreak when hospitalized patients and their family members were unable in any way to make decisions about their lives or to be questioned about their needs and experience.

The acknowledgment of the value of the patient’s perspective entails for researchers understanding how to capture this perspective. Traditionally, user views of health care have been collected through patient satisfaction surveys which nevertheless force patients to express themselves within categories defined beforehand by the researcher (Jha et al. 2007; Mattarozzi et al. 2017). Furthermore, patients’ satisfactions studies have often reported high levels of satisfaction that do not necessarily reflect a lack of problems or problematic experiences with the health care system, rather gratitude or social desirability response bias, enacting the role of the passive patient, as well as beliefs in the legitimacy of their own expectations and lack of willingness to voice discontent (Schneider and Palmer 2002). Think again of what happened during the COVID-19 pandemic: although most surveys conducted during this period on patient satisfaction show no significant changes (Traiki et al. 2020), qualitative research highlights how the subjective experience of patients and family members appears to have been significantly impaired (Moretti et al. 2022; Telatar et al. 2022). So, it was suggested that qualitative approach may be more successful in accessing patients’ view of the quality of care received, since it gives the opportunity for the users to express themselves in their own terms (Ofili 2014; Pyo et al. 2023; Schneider and Palmer 2002).

Qualitative complaint analysis is increasingly recognised as unique channel for collecting spontaneous and unsolicited information (Gallagher et al. 2015; Pearce et al. 2021; Reader et al. 2014). Several authors have recognized the “patient complaint” as a unique and relatively low-cost indicator of the quality of care provided (Adams et al. 2018; Mattarozzi et al. 2017; Mirzoev and Kane 2018). Mattarozzi and colleagues (2017) emphasize how patients may have a privileged view of issues or problems that health care providers fail to recognize or deal with, such as what may occur before a visit or admission, or immediately after; from this perspective, complaints may obviate this blind spot in the process. Similarly, Newdick and Danbury (2015) underline how complaint analysis could be particularly important in a system that culturally prevents staff from independently raising issues regarding quality and safety.

This study analyses complaints, appreciations and requests for information sent by patients, family members, or law firms to a public relations service (URP) of a health care agency in southern Italy. The specific task of the URP is to implement, through listening to citizens and internal communication, the processes of verifying the quality of services and their satisfaction. URP, thus, provides a privileged context to explore expectations, values and evaluation criteria, that users express with respect to the relationship of assistance and care.

The study was launched in 2023, in the aftermath of the health emergency linked to the COVID-19 pandemic, a period characterised, among other elements, by overworked health workers, a ban on visiting hospitalised relatives, and the exacerbation of organisational problems linked to the lack of material and human resources in places of care and treatment (Parsons Leigh et al. 2021). Therefore, it was also considered useful to explore whether and how contents and meaning of users’ communications had varied according to the pre-pandemic, pandemic and post-pandemic periods; the hypothesis is that the pandemic scenario has confronted new challenges and new problems in the relationship with the health care system and therefore made specific content in the communication with the URP meaningful.

2. Materials and Methods

Complaints, appreciations and requests for information received by the URP of a local health agency in Southern Italy were collected, through collaboration with the office, which first stripped the texts of their sensitive data (e.g., first name, last name, contact).

Consistently with the objective to explore whether and how contents and meaning of users’ communications had varied according to the pre-pandemic, pandemic, and post-pandemic periods, URP was asked for all communications received in the following three time:

September 2019 to February 2020 (Pre-Pandemic Period)

March 2020 to August 2020 (Pandemic Period)

September 2022 to February 2023 (Post-Pandemic Period)

The communications were written by patients and family members, sometimes with the assistance of advocacy workers (e.g., from Patients’ Rights Tribunal) and sent to the URP through various channels, such as email, physical desk at the office, portal (from the official website) and via social media (i.e., Facebook page). Communications were eligible for inclusion if, following verification, they had been classified by the investigators as relating to complaints, appreciations towards the health system, or requests for information, while communications containing requests inconsistent with the nature of the service were excluded. Of the 555 texts collected, 501 were considered eligible for analysis (262 sent by women and 239 by men).

As

Table 1 shows, 19,2% of communications were collected in the pre-pandemic period, 38,7% in the pandemic period and 42,1% in the post-pandemic period. 73,4% of the communications were in the nature of complaints, 16% were appreciations and only 10,6% requests for information; a fact that already signals a certain way of interpreting the function of the URP and of using it.

3. Data Analysis

Traditionally, the handling of users’ communication is done on an individual basis. Responses are given on on a case-by-case basis and then generally the file is archived. However, there is increasing recognition of the importance of analysing this source of information in aggregate to understand the macro- and micro-areas most frequently mentioned by users (Adams et al. 2018). This approach also could provide the organization with an insider’s key on user culture both in terms of service use and expectations regarding care and treatment. To this end, an Automatic Procedure for Content Analysis (ACASM; Salvatore et al. 2012, 2017), performed using the T-Lab software (version T-Lab 10.2 Lancia 2023), was applied to the entire corpus of collected texts, preliminarily stripped of ritual formulas, such as,

cordial greetings, cordially, egregious. ACASM is a kind of semantic analysis sensitive to the contextual nature of linguistic meaning, that is to the assumption that the meaning of any word is not fixed but depends on its combination with other words in the dynamic context of discourse. Unlike most semantic analysis methods that focus on the co-occurrence of lexical units, ACASM adopts a single sentence or a small group of sentences, called Elementary Context Units (ECUs), as the context unit. Lexical forms within ECUs are categorized according to their corresponding lemmas. Lemmas are the labels that indicate the lexical forms/classes to which a word refers, regardless of its syntactic form (Pottier 1974). For example, lexical forms “treat,” “treats,” “treated,” and “treating” would be transformed into the single lemma “to treat.” Within this unit, co-occurrences are detected. The multidimensional procedure is applied to the data matrix composed of the segments into which the text is divided (i.e., paragraphs) as rows, lemmas as columns and presence/absence values in cells.

Table 2 describes the characteristics of the dataset.

The analysis was performed in two steps. Firstly, the T-LAB software analysis “Thematic Analysis of Elementary Contexts” has been performed. It enables the construction of a representation of corpus content through the identification of meaningful thematic clusters (Lancia et al. 2012). Each cluster is defined by a set of ECUs characterized by the same keyword patterns and is described through the lexical units (lemmas) and variables (in our case, the typology of communication - info, complaint or acknowledgement and temporal block - pre-pandemic, pandemic, or post-pandemic) that most characterize the elementary contexts of which it is composed. The outcome of this analysis is a detailed mapping of general or specific themes (Rastier 2002), highlighting the presence of distinct semantic traits. Interpreting clusters means identifying the thematic core shared by different representational contents conveyed by each grouping. We consider each cluster as the expression of a specific way of representing (of having an opinion, of connoting) the various objects of experience on which users express themselves. For each cluster, we identify the percentage of texts related to each of the temporal block considered (pre-pandemic, pandemic and pot-pandemic) and typology (info, complaints and acknowledgment). Then, in order to investigate the dimensions of meanings which explain similarities and dissimilarities among the texts collected, a Lexical Correspondence Analysis (LCA) – a factor analysis procedure for nominal data (Benzécri 1973) — was applied on the contingency table lexical units x clusters (Benzécri 1984; Greenacre 1984; Lebart and Salem 1994), to retrieve the factorial dimensions describing lemmas with higher degrees of association, i.e., occurring together many times.

Broadly speaking, LCA breaks down and reorganizes the relations between lemmas in terms of a multidimensional structure of opposed factorial polarities; where each polarity is characterized by a set of lemmas that tend to co-occur and do not occur in the event of the occurrence of an opposite set. Accordingly, this structure can be interpreted as the operationalization of the semantic structure of the textual corpus under investigation, with any factorial dimension to be seen as a marker of a dimension of semantic variability. Interpreting each dimension means understanding which common meaning emerges from the subset of lemmas that characterize one polarity and which from the subset of lemmas that characterize the other polarity, as well as understanding the second-order meaning that emerges from their aggregation (Venuleo and Guacci 2014). In the present study, we interpret the first two factor dimensions that correspond to the Latent Dimensions of Meanings that best explain the variability of the data.

It is possible to graphically represent the associations between words and texts on planes bounded by two orthogonal axes. Conventionally, the first factor is represented by the horizontal axis where the negative polarity (-) is placed on the left and the positive (+) polarity on the right, while the second factor is represented by the vertical axis where the negative polarity (-) is placed at the bottom and the positive polarity (+) at the top of the graph. Each factor is associated with a label that identifies a specific mode of symbolization as opposed to another mode, identifying the other pattern (Venuleo and Guacci 2014).

The variable period of production of the text (pre-pandemic, pandemic, post-pandemic), as well as the nature of the text (complaint, appreciation or request for information) have been included in the analysis as illustrative variables: they, therefore, did not contribute to the definition of factor dimensions; rather, they have been used as a criterion of comparison once their definition has been obtained, to analyse their positioning in symbolic space.

4. Results

4.1. The Main Semantic Cores

The analysis of the clusters allowed to identification of four main semantic cores. Some of the main segments (“typical phrases”) that characterize them are shown in italics. Where reference to names of specific doctors or other professionals or specific departments appeared in the text, the name was blacked out and replaced with ‘xxx’.

Cluster 1: The right to be cared for and respected

They don’t know where to go and they don’t know how long they have to wait to check the course of their disease. Therefore, the TDM (patients’ court) understands the difficulty of patients, respecting the right to access: every individual has the right to access health services that his or her state of health requires.

Other waiting patients complained about being greeted with profanity in the background when ringing the doorbell of the ward. I assure you that while it can be irritating for the staff to receive patients, it is certainly not a walk in the park for the patients to come to the hospital in this situation.

When I went to the ward, I found the patient with the following conditions: open windows with the power going right on the patient; sun beating down on the medications and on the patient; foot bent to the bedside certainly for hours with severe injuries to the foot with related bleeding and sores.

Every sick person has the right to quality continuity of care, both in and out of the hospital; the right to be welcomed into services by qualified staff who are willing to listen and fully trained as well as the right to have their specificity arising from age and health conditions recognized.

Do patients remain patients from ward to ward? What happened to the right of a wife, a mother, a child to see a suffering relative in need of 10 minutes of affection? Does the Covid precaution start from the relatives of patients or from the staff serving in the wards, given the absence of the planned protective device?

Cluster 1 collects discourses that refer to the patient’s right to be treated and respected and to circumstances in which this right has been lost: for example, waiting lists for access to care that are evoked that are incompatible with the urgency of the diagnostic question; there are also mentioned situations of neglect towards the hospitalized patient, inadequate communication methods towards patients waiting for an outpatient visit, as well as – with reference to the health emergency – the possibility denied to family members to be close to the suffering relative in the name of a principle of health protection that seems to be denied by health workers without personal protective equipment

Cluster 2: Barriers to access to care

Premise: I had been trying to get a visit through CUP (unique reservation centre) for a long time, but since everything was blocked, I decided to find a visit even for a fee. All the facilities contacted told me that the visit was 80 € + 50 for the ultrasound examination. So, all facilities, including xxx, told us that the full visit was 132 €.

I took my disabled mother-in-law for a visit for ALPI (ALPI represents an additional paid service provided by the Local Health Authority to the user who can freely choose the doctor and the service.) activities with doctor xxx, paid the €82 co-pay regularly and waited in vain in the clinics. After some time, I noticed that no one was there to do the examination, I went to the ward to ask for an explanation and the medical staff told me that the doctor was not at work.

The prescription for the examination to be done before the visit, I made it back in April as indicated in the attachment, but to date it has not been possible to have the reservation due to the known delays. I have been suggested to have the examination in other hospitals, but I do not have the possibility to go outside xxx.

I went to the health directorate to complain and after contacting the on-call doctor of xxx ward he/she refused to do the exam stating that ALPI was working in charge of another doctor. I made myself available to regularize the ticket in his name but in vain. After several hours of waiting, I returned at 6 p.m. without performing any examination.”

So, after several checks, a nurse tookmy prescription and went to the CUP where he was printed the receipt of my reservation, only then I was informed that the doctor’s visit was at another facility. Once I got my car, I went to xxx hospital where I waited for the doctor to call me to make the visit.

Cluster 2 collects discourses that refer to the difficulties in accessing assistance: economic difficulties in undergoing specialist examinations in the private sector due to long waiting times required by the public service, but also difficulties related to inefficiencies (the absence of the doctor in the face of a visit by appointment; the vain wait to be received) and unclear or incomplete communications (for example on the place of the appointment).

Cluster 3: The impossibility of contact

I have called many times, and it is always busy, or rings and they don’t answer. The answering machine picks up, tells me the operator is busy and to call from 9 a.m. to 12 p.m. and two days a week in the afternoon; but I call but will I ever be lucky to get the line, what should I do?

A week ago, I had called the ASL in xxx, since they were not answering I called the one in xxx, I had talked to an operator and asked if the ASL in xxx should make a reservation to do withdrawals, they answered and told me that I could go without a reservation. Today, however, when I showed up at the ASL of xxx I was told that I had to make a reservation.

I confirm that no one answers and having contacted the xxx switchboard to get more information; the receptionist confirmed that complaints are widespread and daily because the service staff does not answer the numbers given, despite the fact that it is a paid service.

I would like to report that the reservation centre is not answering the phone. After two days of continuous phone calls in the afternoon, no one answered. I had to go directly, in a pregnant state, to the counter located on the ground floor of xxx hospital to find out, cell phone in hand, that the phone at the booking point did not make a sound.

Good morning, I’m txt, I’ve been trying to book the various exams for prevention for days, but at the numbers they gave me and found on the Puglia Salute website no one answers. Can you tell me how we can make reservations? There is a lot of talk about prevention, but it is impossible to make an appointment over the phone

Cluster 3 collects discourses that refer to the difficulty/impossibility of getting in touch with operators and services responsible for booking examinations and visits: telephones that are always busy, operators that do not answer, telephone numbers that are not active.

Cluster 4: The value of the doctor-patient relationship

Good morning, I am the daughter of Mr. and Mrs. xxx who came to you on the day for a xxx in the emergency room of the xxx presidio. The emergency room promptly assisted dad and mom, thanks also to you. I would like to take this opportunity to thank and express our gratitude for how the team at xxx hospital extended care for my dad. A heartfelt thank you to the head doctor Dr. xxx.

This is meant to be a praise to Dr. xxx, not to mention the invaluable intervention of the team that performed the operation. All of us, relatives and friends of the patient, wish to express our deep and sincere thanks to the said Doctor, as a doctor with professionalism and great humanity.

At a sad and desperate time in our lives, I met exceptional people. People who work hard in your hospital and whom you can be proud of. I wanted you to share my thoughts for the doctor who, with great professionalism, contributes prestige. I have sent you an attached letter. I hope it may be appreciated.

On behalf of myself and my entire family, I want to extend a simple thank you for the dedication and determination shown by all the teams, but in particular an endless thank you to the doctors of the xxx department. I ask that all departments in the hospital be as efficient as xxx’s department is, thank you.

I wanted you to share my thoughts for the doctor who, with great professionalism, gave his life. I have sent you a letter attached. Thank you from the bottom of my heart. Letter: To the doctor with infinite gratitude. sometimes it is difficult to express in words what is in one’s heart.

Cluster 4 collects discourses that refer to gratitude for the care received, emphasizing characteristics such as timeliness, determination, humanity and dedication shown by specific health professionals or entire hospital teams in the care and care of the sick.

4.2. The Latent Dimensions of Meaning

Table 3 and

Table 4 illustrate, respectively, the first and the second factorial dimensions obtained by the LCA. For each polarity of the two dimensions, the lemmas with the highest level of association (V-Test) are reported, as well as their interpretation in terms of labelling of their meaning. Henceforth, we adopt capital letters for labelling the dimensions of meaning and italics for the interpretation of polarities.

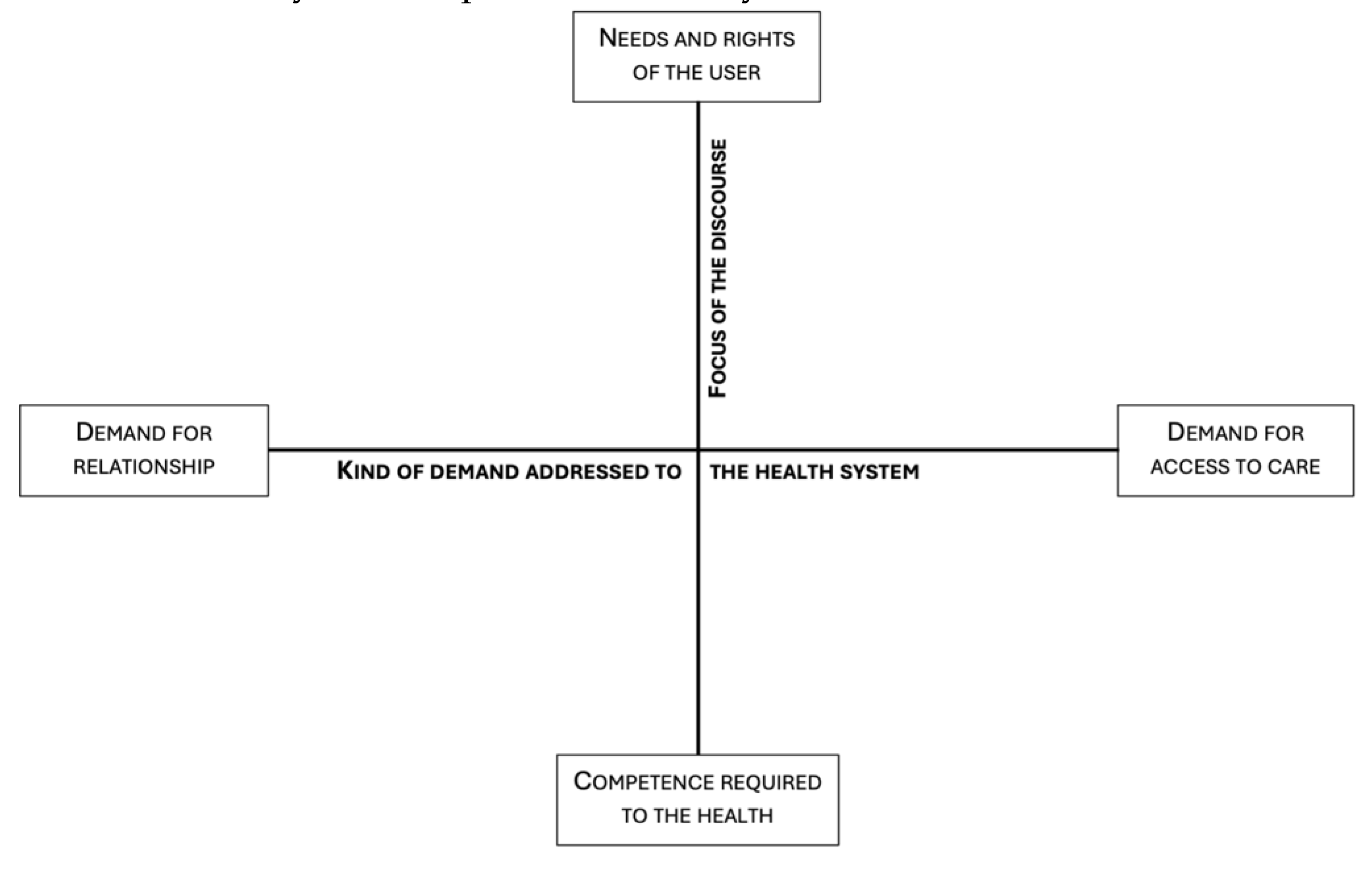

FIRST DIMENSION: KIND OF DEMAND ADDRESSED TO THE HEALTH SYSTEM

The first dimension organizes two different types of demand addressed to the health system that can be interpreted in terms of the dialectic:

Demand for relationship vs Demand for access to care (

Table 3).

(-) Demand for relationship. On this polarity, lemmas that refer to a dimension of gratitude (thank you, to thank, thanksgiving, gratitude), co-occur with lemmas that refer to the doctor-patient relationship, qualifying it, positively or negatively (violation) with respect to dimensions of humanity, competence, professionalism, and with reference to the context of hospitalization (hospital, ward) and critical health conditions (illness, life), of oneself as a patient or of a family member (mom). On the whole, the polarity seems to refer to the close relationship drawn by the writer between relationship and care.

(+) Demand for access to care. On this polarity, lemmas referring to procedural dimensions (booking, to book, payment, prescription), communication channels (telephone, number, email) and service (CUP, office) that mediate access to the health system (visit, appointment, examination, check-up), co-occur with lemmas that refer to contact by the user to receive answers to their questions (call, ask, contact, request, communicate, office, to ask, ask, to answer).

SECOND DIMENSION: FOCUS OF DISCOURSE

The second factor accounts for two different focuses of the discourse: on the one hand, the

competence required of the health profession and

, on the other hand

, the

needs and rights of the service user (

Table 4).

(-) Competence required to the health profession. On this polarity, lemmas that refer to communication (call, to contact, office, answer, word) and to professionalism and competence (doctor, professionalism, professional, competence) co-occur with lemmas that refer to specific affective relationships (mom, dad, son) and the experience of seeing the patient recognized in his totality and specificity (person, suffering, particular, to feel, humanity) with related feelings of gratitude (thank you, thanksgiving) or the denial of this experience (violation), as when the perceived experience is of being treated as a number.

(+) Needs and rights of the user. On this polarity, lemmas that refer to different phases of hospital assistance and intervention (to access, intervention, first aid, assistance, to recover, surgery, hospitalized, therapeutic, drug), qualified in terms of quality parameters, co-occur with lemmas that recognize the user of the health system (health service, system, health) both as a patient in need of assistance and treatment (patient, hospitalized, affection, pathology, serious) and as a citizen with rights.

Figure 1 describes the symbolic space bounded by the two factorial dimensions described above.

4.3. Relationships between Dimensions of Meaning and Texts’ Characteristics

Both the period of receipt of the communications and their typology (complaints, appreciations and requests for information) show a different association with the first factorial dimension (

Kind of demand addressed to the health system) obtained by the LCA (

Table 5). More particularly, appreciations and texts collected during the pre-pandemic and pandemic periods – months characterized by the overload of health systems, and by anti-contagion measures that prohibited or severely limited the access of family members to visits – tend to be placed on the negative polarity (

Request for relationship), organized by the recognition of a close connection between the treatment of the disease and the care of the relationships. On the other hand, complaints, requests for information texts collected in the post-pandemic period tend to be placed on the positive polarity (

Demand for access to care) organized by the demand for access to care and the procedural and organizational difficulties that hinder the satisfaction of this demand.

The period of production of the texts and their nature present specific associations with respect to the polarities of the second factorial dimension (

Focus of the discourse) (

Table 5). Appreciations, requests for information and texts produced in the pre-pandemic period tend to be placed on the lower polarity (

Competence required to the health profession), where the client’s demand is to be supported, in his/her treatment pathway, both from the point of view of technical competence and from a relational and emotional point of view. On the contrary, complaints and texts produced in the post-pandemic period tend to be placed on the higher polarity (

Needs and rights of the user of the service), where the client’s demand is to be recognized not only as a patient suffering from a pathology and therefore in need of care, but also as a citizen, with specific rights of assistance and care.

As

Table 6 shows, also the clusters present specific associations with the two factorial dimensions identified. More particularly, along the first dimension, the cluster 1 “The right to be treated and respected” and the cluster 4 “The value of the doctor-patient relationship” relate to the demand for relationship polarity, while the cluster 2 “Barriers to access to care “ and the cluster 3 “The impossibility of contact” related to the opposite polarity

Demand for access to care. , With regard to the second factorial dimension, only the cluster 3 “The impossibility of contact” relate to the negative polarity (

Competence required to the health profession); the other clusters relate to positive polarity

(Needs and rights of the service use ).

5. Discussion

The study aimed to explore thematic contents and evaluation criteria characterizing the communications sent by citizens to the URP of a Local Health Agency of Southern Italy, so to capture what went wrong and what gone right in the subjective experience of the users. Findings highlights the importance of both interpersonal skills in service delivery and organisational aspects that allow access to care at the right time.

Cluster analysis led to the identification of four semantic cores. It is interesting to note that two of them focus on relational competence skills required from those working in the health care system. Attention to the relationship is both asserted as a right, which users claim when they feel they have been treated insensitively and/or have been poorly listened to (cluster 1 “The right to be cared for and respected”) and recognized as a value, qualifying the service received, when empathy, attention, humanity were perceived in the operator (cluster 4 “The value of the doctor-patient relationship”). The other two semantic cores focus on more organisational aspects, which constrain and, in some cases, prevent the very use of services (cluster 3 “The impossibility of contact” and cluster 2 “Barriers to access to care”).

The URP (to whom communications are addressed) therefore, on the one hand is called upon to act as guardian and guarantor of crucial aspects for the smooth functioning of the service, which sometimes seem to be missing or faltering, such as the right to be cared for, to receive answers, and to have empathetic and respectful relationships with professionals, and on the other hand to mediate communications of appreciation when these same aspects of the functioning of the health system seem to be working well.

Regarding the results of LCA, findings show how the texts collected are guided by two fundamental dimensions of meaning. One concerns the kind of demand addressed to the health system and can be described in terms of the dialectic between Demand for relationship and Demand for access to care.

The Demand for relationship polarity – which mainly characterizes appreciations, texts collected during the pre-pandemic and pandemic periods and texts falling within Cluster 1 “The right to be treated and respected” and the Cluster 4 “The value of the doctor-patient relationship” – brings to foreground the value of being treated with respect, empathy, compassion, humanity, to be listened to, welcomed and contained in their own concerns. In this case, the discourses focus on the ability or inability of healthcare personnel to meet the standards expected of a formal social encounter (e.g., showing up or not showing up), the time given to the encounter with the patient, the use of sensitive or offensive verbal and non-verbal communication, the willingness or unwillingness to answer questions posed by the user, the empathy or emotional distance shown towards the patient’s needs and concerns. Users’ communications, thus, invite us to consider that practitioners’ knowledge and technical skills constitute only one side of the healthcare role, which must include compassion, kindness, listening, recognizing the user not just as a patient with a disease but as a biopsychosocial being, bearer of fears, anxieties, concerns which ask to be contained (Bush et al. 2019). Analysis of literature show how unsatisfactory communication or failings in respect and empathic staff responses are common. Hogg and colleagues (2018) report that each year with NHS Scotland and associated contractors such as general practitioners, the most commonly mentioned problems are communication issues (47%) and staff attitudes and behaviour (42%), followed by medical treatment (35%). van Mook and colleagues (2015), in a study of unprofessional behaviour in health care, highlight how complaints about relational aspects of professionalism (such as attention, empathy, communication skills) far outnumber complaints about specifically technical and cognitive skills, such as medical mistakes. Complaints about unsatisfactory communication focused mainly on “insufficient clarification/unclear information.” This included lack of clarity in explanations of diagnosis and treatment, often due to the excessive use of medical jargon and failure to provide written information materials, such as pamphlets, to patients. Taylor, Wolfe, and Cameron (2002) reported that 32% of complaints about an Australian emergency department related to communication including poor staff attitude, discourtesy and rudeness. It has been observed how within a biomedical approach, focused on the diagnosis and treatment of illness, caring for the emotional aspects of the doctor-patient relationship is often not considered an integral part of the professional role (Checkland et al. 2008). On the contrary, stereotypes and professional implicit norms often foster health providers’ emotional detachment (Halpern 2001; Martínez-Morato et al. 2021), within a view of emotional involvement as an obstacle to care and, thus, unprofessional and inconvenient (Meier et al. 2001; You et al. 2015). However, unrecognized emotions in the healthcare providers’ experience may prevent the adoption of a patient-centred style of care and may be associated with harmful behaviours, such as neglecting patients’ psychological issues (Smith et al. 2005). Research shows how failure to take care of the relationship, affect patient outcomes in terms of their feelings and their confidence in the outcomes of current and future healthcare encounters (Hogg et al. 2018). On the opposite, being treated with dignity is linked to higher patient therapy adherence and satisfaction, also at the end of life (Beach et al. 2025).

The Demand for access to care polarity – which mainly characterize complaints, requests for information, texts collected during the post-pandemic period and texts falling within the cluster 2 “Barriers to access to care” and the cluster 3 “The impossibility of contact” – brings to foreground the need to overcome structural barriers to health. Complaints mainly relate to not being able to get in touch with health services and not having access to health care or aids, due to operators not answering the phone and biblical waiting times to get a medical examination. As suggested by Santana and colleagues (2023), healthcare is ‘appropriate’ not only when it is cost-effective but also when it is provided in the right environment and at the right time. Characteristics of health resources play a central role in facilitating or impeding the use of services by potential users. Policies and organisational aspects of care should be targeted to improve access, which is determined by factors such as the availability, price and quality of health resources, goods and services (Levesque et al. 2013). Long waiting times for elective procedures are already recognized as a major problem and one of most important health policy concerns in most OECD countries (Siciliani et al. 2014). In Italy, the context of the current study, excessive waiting lists have been widely documented by independent and National agencies (CENSIS/RBM 2018; ISTAT 2023), especially in the southern regions of the country (Ferré, et al. 2014). Long waiting times in turn inhibit the demand of citizens for public health services and foster inequities in accessing care since the ability to turn to private health care, paying additional fees, increases with socioeconomic status (Baldini and Turati 2012; European Commission et al. 2018). Research has suggested that even countries with a universal and egalitarian public health care system, like Italy, exhibit a certain degree of SES-related horizontal inequity in health services utilization (Glorioso and Subramanian 2014). Glorioso and Subramanian (2014), in a study focused on Italy, found a significant amount of pro-rich inequity in the utilization of specialist care, diagnostic services, and basic medical tests. It is worth to observe that excessive waiting time for care and clients’ disinformation about the reasons for waiting has been documented also as a key factor kindling violence against health workers (Caruso et al. 2022).

The second factorial dimension highlight how users’ communications focus alternately on the Competence required to the health profession or on the Needs and rights of the user of the service. The first polarity – which mainly characterize appreciations, requests for information, texts collected during the pre-pandemic period ad texts falling within the cluster 3 “The impossibility of contact” and the cluster 4 “The value of the doctor-patient relationship” – the value of patient-centred care and treatment, which implies both attention to responding to the patient’s needs within a lawful timeframe and attention not to make the user feel like a number, to respect their dignity, to listen to their needs, to treat them with kindness and sensitivity.. The other polarity – Needs and rights of the user of the service – which mainly characterize complaints, texts collected during the post-pandemic period and texts falling within the cluster 1 “The right to be treated and respected”– identifies a different area of meaning, where the patient’s need for timely clinical investigation, examination, specific treatment, is asserted as a right. Critical medical conditions and suffering are evoked, where sometimes the patient’s life is at stake and where therefore any inefficiency in responding to their needs is particularly critical. The communications, sometimes written by the Tribunal for Patients’ Rights, to which the patient or a family member has turned to complain about a lack of care, often refer to Article 32 of the Italian Constitution, according to which the Italian healthcare system is built on a universalistic concept of solidarity and promises to ensure care and assistance to all, regardless of nationality, residence, and income. Other times reference is made to the Hippocratic Oath, which in its modern version dating back to the 21st century A.D., refers to principles such as the doctor’s duty to pursue the defence of life, the protection of physical and mental health, the treatment of pain and the relief of suffering with respect for the dignity and freedom of the person. The long waiting times to receive the requested service, in the face of the urgency with which the user is confronted, together with the economic impossibility of turning to a private party, are perceived and presented as a violation of these principles and rights of the citizens.

It is interesting to observe how appreciations and communications received during the pre-pandemic and pandemic periods tend to be characterised by an emphasis on the relational aspects of care. In contrast, complaints and communications received during the post-pandemic period concern more organisational and structural aspects. It is possible to hypothesise that being treated with humanity, kindness, compassion is not taken for granted in the experience of users, so that when they are confronted with relationally competent operators, they feel they have received more than they expected. This is all the more understandable during the pandemic period. Previous studies have highlighted the idealization of the figure of the health workers that took place during the pandemic (Cassandro 2020), in the recognition of the effort made to save lives in a tragic historical period and in front of the limited resources received to cope with the battle. On the other hand, the COVID-19 scenario, characterised - among other elements - by important measures restricting family visits to hospitalised patients, has made the need and demand for relationally competent health workers more cogent. As suggested by Morley and colleagues (2020), the challenge for health and social workers was to temper the potentially dehumanising scenario.

Complaints occur when the users feel denied minimum levels of care and the right to care, due the difficulty of getting in touch with the health system to book a medical examination or perform a diagnostic test; it is not surprising that such complaints mainly characterize the post-pandemic period. In Italy, the context of the current study, the COVID-19 health emergency happened within a health system already suffering from a progressive decrease in resources allocated for health-related research and public health, characterized by insufficient availability of medical personnel, products, and physical structures. Lockdown measures and access restrictions in hospitals have delayed the demand for diagnostic tests and access to treatment by non-COVID-19 patients, further lengthening waiting lists in the post-pandemic period (Lamberti-Castronuovo et al. 2022).

A last comment on the interpretation of the function of the URP, as it emerges by the typology of the communication sent by the users: in some cases, the URP is used as a channel of appreciations – where timely and relationally competent assistance has been recognized; in other cases, the majority, it is used as a receptacle for complaints, frustrations, claims for rights of assistance that have been perceived to be violated. By this perspective, the major function recognized to the URP by the users seems to be that to exercise a control function with respect to the inappropriate behaviour of those who work in the health system (not only health workers, but also those who work at the counter, at reception and booking services) and to guarantee the right to be treated promptly by removing the obstacles (long waiting lists, booking difficulties, inadequate medical examinations...) that deny this right.

Authors should discuss the results and how they can be interpreted from the perspective of previous studies and of the working hypotheses. The findings and their implications should be discussed in the broadest context possible. Future research directions may also be highlighted.

6. Conclusions

Embracing the patient’s experience of care in its complexity means for health systems to have a unique opportunity to improve patient satisfaction and quality of care. It is worth to underline how welcoming the patients’ point of view does not mean responding to the manifest problem and closing a bureaucratic issue but recognise their communications as a signal of what matters to users, hence the criteria they use to evaluate their experience and relationship with the service. Complaints and appreciations offer a “window of opportunity” to improve health services (Paterson 2002) giving insights into aspects of healthcare that traditional quality and safety reporting systems fail to capture (Råberus et al. 2019; Reader et al. 2014).

In recounting above all their positive experiences with the healthcare system, users emphasise the importance of communication skills, respect for patient views, empathy, which build mutual trust, affect information processing and people’s health choices, as highlight by previous research (Barello and Graffigna 2020). Equipping healthcare providers with such psychosocial abilities should become an integral aim of medical education (Bush et al. 2019). An ethic of care would involve a health professional being sympathetically understanding of the experience of patients and family members, sensitive and responsive to their emotional and knowledge needs, engaged to prevent and relieve suffering throughout an illness experience and until the end of life (Sheahan and Brennan 2020; Venuleo et al., 2022.). Tailored training initiatives in self-awareness, communications skills to convey empathy, de-escalation techniques, could be useful to this end.

At the same time, it is worth to recognize how many complaints focus on the very denial of the right of access to care, signalled by very long waiting lists and the absence of answers to urgent care needs. Limited economic and personnel also represent important sources of physical and mental fatigue, stress, anxiety, and burnout among health workers (Adams & Walls, 2020; Marinaci et al. 2020, 2021), and these components compromise the health-care workers capacity to provide respectful and compassionate care and to assure effective communication with patients and family members. So, it is equally important to emphasize the need for adequate institutional responses. People’s vulnerability and health workers capacity to assure appropriate responses are also constructed by economic and political conditions.

Limitations

The results of the present study should be considered in light of some methodological limitations. First, the results cannot be generalized and have to be related to the specific socio-cultural context under analysis. Because evaluation criteria and meanings through which people interpret quality service depend on their working also on sociohistorical conditions and are placed within the sphere of social discourses, we might suppose that, in other local health agency and countries, complaints and appreciations focus on different components of the health system. Consider, for example, how in Italy there is a considerable north–south divide in the quality of health care facilities and services provided to the population. It is possible that the focus on aspects related to the right of access to care would have been less pregnant if we had analysed communications addressed to the Public Relations Office of a Local Health Agency in Northern Italy.

Second, our study could not consider could the role of variables such as sociodemographic characteristics, psychological well-being, longer or shorter life expectancy, perceived social support, trust in institutions in influencing the type of evaluations, expectations expressed by the users.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, C.V. and T.M.; methodology, C.V. and T.M.; formal analysis, T.M.; investigation, C.C and S.G.; data curation, C.C. and S.G.; writing—original draft preparation, C.V.; writing—review and editing, T.M., C.C. and S.G. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

All procedures used in this research comply with the ethical standards of the relevant national and institutional committees on human experimentation and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2008. The study was carried out within the framework of the memorandum of understanding established between the Local Health Agency (ASL) of Lecce and the Department of Human and Social Sciences of the University of Salento for the implementation of initiatives for training, professional qualification and research in the field of psychology (date (protocol n.: 111199 of July 2023). All procedures were approved by the Ethics Commission for Research in Psychology of the Department of Human and Social Sciences of the University of Salento (prot. N. 144542 of 12/07/2023).

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable. The data were provided anonymously by the user communication reporting system of the Public Relations Office of the Local Health Agency of Lecce (Italy); none of the names or other personal information of patients, relatives, healthcare professionals in the communications were obtained.

Data Availability Statement

Data will be made available on request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Adams M, Maben J, Robert G (2018) ‘It’s sometimes hard to tell what patients are playing at’: How healthcare professionals make sense of why patients and families complain about care. Health 22(6):603-623. [CrossRef]

- Adams JG, Walls RM (2020) Supporting the health care workforce during the COVID-19 global epidemic. JAMA 323(15):1439-1440. [CrossRef]

- Almeida RSD, Bourliataux-Lajoinie S, Martins M (2015) Satisfaction measurement instruments for healthcare service users: a systematic review. Cad Saude Publica 31:11-25. [CrossRef]

- Baldini M, Turati G (2012) Perceived quality of public services liquidity constraints and the demand of private specialist care. Empir Econ 42 487-511. [CrossRef]

- Barello S, Graffigna G (2020) Caring for health professionals in the COVID-19 pandemic emergency: toward an “epidemic of empathy” in healthcare. Front psychol 11 548845. [CrossRef]

- Batalden M, Batalden P, Margolis P, Seid M, Armstrong G, Opipari-Arrigan L, Hartung H (2016) Coproduction of healthcare service. BMJ Qual Saf 25(7):509-517. [CrossRef]

- Beach MC, Sugarman J, Johnson RL, Arbelaez JJ, Duggan PS, Cooper LA (2005) Do patients treated with dignity report higher satisfaction adherence and receipt of preventive care? Ann Fam Med 3(4) 331-338. [CrossRef]

- Bennett PN, Wang W, Moore M, Nagle C (2017) Care partner: A concept analysis. Nurs Outlook 65(2) 184-194. [CrossRef]

- Benzécri JP (1973) L’analyse des données [Data Analysis] Vol 2. Dunod.

- Benzécri JP (1984) Description des textes et analyse documentaire. Les cahiers de l’analyse des données 9(2):205-211.

- Bloemer J, De Ruyter KO (1999) Customer loyalty in high and low involvement service settings: The moderating impact of positive emotions. J Mark Manag 15(4):315-330. [CrossRef]

- Busch IM, Moretti F, Travaini G, Wu AW, Rimondini M (2019) Humanization of care: Key elements identified by patients, caregivers, and healthcare providers. A systematic review. Patient 12:461-474. [CrossRef]

- Caruso R, Toffanin T, Folesani F, Biancosino B, Romagnolo F, Riba MB,... Grassi L (2022) Violence against physicians in the workplace: trends, causes, consequences, and strategies for intervention. Curr Psychiatry Rep 24(12):911-924. [CrossRef]

- Cassandro D. (2020) Siamo in guerra! Il coronavirus e le sue metafore [We are at war. The Coronavirus and its metaphors]. L’Internazionale. https://www.internazionale.it/opinione/daniele-cassandro/2020/03/22/coronavirus-metafore-guerra?fbclid=IwAR0kZCnNmLZLENFTAPUIFtkq8bqrabqMe-vEoZpQZ6Wig55XdPEWlzdzRkE Accessed 18 June 2024.

- Castro EM, Van Regenmortel T, Vanhaecht K, Sermeus W, Van Hecke A (2016) Patient empowerment, patient participation and patient-centeredness in hospital care: A concept analysis based on a literature review. Patient Educ Couns 99(12):1923-1939. [CrossRef]

- CENSIS/RBM (2018) VIII Rapporto RMB – CENSIS sulla Sanità Pubblica, Privata ed Intermediata. La Salute è un Diritto. Di Tutti [VIII RBM - Censis Report on Public, Private and Intermediate Health Care. Health is a Right. Everyone’s]. https://www.quotidianosanita.it/allegati/allegato5933767.pdf Accessed 18 June 2024.

- Checkland K, Harrison S, McDonald R, Grant S, Campbell S, Guthrie B (2008) Biomedicine, holism and general medical practice: responses to the 2004 General Practitioner contract. Sociol Health Il 30(5):788-803. [CrossRef]

- Committee On Hospital Care, Institute For Patient, Family-Centered Care (2012) Patient- and family-centered care and the pediatrician’s role. Pediatrics 129(2):394–404. [CrossRef]

- Crawford MJ, Rutter D, Manley C, Weaver T, Bhui K, Fulop N, Tyrer P (2002) Systematic review of involving patients in the planning and development of health care. Bmj 325(7375):12-63. [CrossRef]

- Doyle C, Lennox L, Bell D (2013A) systematic review of evidence on the links between patient experience and clinical safety and effectiveness. BMJ Open 3: e001570. 3, e001570. [CrossRef]

- Dragoi L, Munshi L, Herridge M (2022) Visitation policies in the ICU and the importance of family presence at the bedside. Intensive Care Med 48(12):1790-1792. [CrossRef]

- Edvardsson B (2005) Service quality: beyond cognitive assessment. Manag Serv Qual Int J 15(2):127-131. [CrossRef]

- European Commission, Directorate-General for Employment, Social Affairs and Inclusion, Baeten R, Spasova S, Coster S (2018) Inequalities in access to healthcare: a study of national policies. Publications Office.. https://data.europa.eu/doi/10.2767/371408.

- Ferré F, de Belvis AG, Valeria L, Longhi S, Lazzari A, Fattore G,... Maresso A (2014) Italy: health system review. Health Syst Transit 16(4) 1-68.

- Gallagher TH, Mazor KM, (2015) Taking complaints seriously: using the patient safety lens. BMJ Qual Saf 24(6):352-355. [CrossRef]

- Gleeson H, Calderon A, Swami V, Deighton J, Wolpert M, Edbrooke-Childs J (2016) Systematic review of approaches to using patient experience data for quality improvement in healthcare settings. BMJ open 6(8) e011907. [CrossRef]

- Glorioso V, Subramanian SV (2014). Equity in access to health care services in Italy. Health Serv. Res. 49(3) 950-970. [CrossRef]

- Gluyas H. (2015). Patient-centred care: improving healthcare outcomes. Nurs Stand 30(4) 50-59. [CrossRef]

- Greenacre MJ. Vrba ES (1984). Graphical display and interpretation of antelope census data in African wildlife areas, using correspondence analysis. Ecology 65(3) 984-997. [CrossRef]

- Halpern J. (2001). From detached concern to empathy: humanizing medical practice. Oxford University Press. [CrossRef]

- Haskard KB, Williams SL. Dimatteo MR (2009) Physician-patient communication: Psychosocial care, emotional well-being, and health outcomes. In Brashers D.E. & Goldsmith D. J. (ed) Communicating to Manage Health and Illness. Routledge (pp. 23-48). [CrossRef]

- Hogg R. Hanley J. Smith P (2018). Learning lessons from the analysis of patient complaints relating to staff attitudes, behaviour and communication, using the concept of emotional labour. J. Clin. Nurs. 27(5-6) e1004-e1012. [CrossRef]

- ISTAT (2023) Indagine conoscitiva sulle forme integrative di previdenza e di assistenza sanitaria nel quadro dell’efficacia complessiva dei sistemi di welfare e di tutela della salute [Survey on supplementary forms of social security and health care in the context of the overall effectiveness of welfare and health protection systems]. https://www.quotidianosanita.it/allegati/allegato1678270270.pdf. Accessed 18 June 2024.

- Jessup R. Putrik P. Buchbinder R. Nezon J. Rischin K. Cyril S.... O’Connor D. A. (2020). Identifying alternative models of healthcare service delivery to inform health system improvement: scoping review of systematic reviews. BMJ open 10(3) e036112. [CrossRef]

- Jha V, Bekker HL, Duffy SR, Roberts TE (2007) A systematic review of studies assessing and facilitating attitudes towards professionalism in medicine. J. Med. Educ. 41(8) 822-829. [CrossRef]

- Kaba R., Sooriakumaran P. (2007) The evolution of the doctor-patient relationship. Int. J. Surg. 5(1) 57-65. [CrossRef]

- Lamberti-Castronuovo A, Parotto E, Della Corte F, Hubloue I, Ragazzoni L, Valente M (2022) The COVID-19 pandemic response and its impact on post-corona health emergency and disaster risk management in Italy. Front Public Health 10 1034196. [CrossRef]

- Lancia F (2012) T-LAB Pathways to Thematic Analysis. http://www.tlab.it/en/tpathways.php. Accessed 18 June 2024.

- Langberg EM, Dyhr L, Davidsen A S (2019) Development of the concept of patient-centredness-A systematic review. Patient Educ Couns 102(7) 1228-1236. [CrossRef]

- Leatherman S, Ferris TG, Berwick D, Omaswa F, Crisp N (2010) The role of quality improvement in strengthening health systems in developing countries. Int J Qual Health Care 22(4) 237-243. [CrossRef]

- Lebart L, Salem A (1994) Statistique textuelle. Dunod.

- Levesque JF Harris MF., Russell G (2013) Patient-centred access to health care: conceptualising access at the interface of health systems and populations. Int. J. Equity Health 12 1-9. [CrossRef]

- Marinaci T, Carpinelli L, Venuleo C, Savarese G, Cavallo P (2020) Emotional distress, psychosomatic symptoms and their relationship with institutional responses: A survey of Italian frontline medical staff during the Covid-19 pandemic. Heliyon, 6(12). [CrossRef]

- Marinaci T, Venuleo C, Savarese G. The COVID-19 Pandemic from the Health Workers’ Perspective: Between Health Emergency and Personal Crisis. Hu Arenas (2021). [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Morato S, Feijoo-Cid M,. Galbany-Estragués P, Fernández-Cano M I, Arreciado Marañón A (2021) Emotion management and stereotypes about emotions among male nurses: a qualitative study. BMC Nurs. 20(1) 114. [CrossRef]

- Mattarozzi K, Sfrisi F, Caniglia F, De Palma A, Martoni M (2017) What patients’ complaints and praise tell the health practitioner: implications for health care quality. A qualitative research study. Int J Qual Health Care 29(1):83-89. [CrossRef]

- Meier D E, Back AL, Morrison RS (2001) The inner life of physicians and care of the seriously ill. Jama 286(23) 3007-3014. [CrossRef]

- Mirzoev, Kane S (2018) Key strategies to improve systems for managing patient complaints within health facilities–what can we learn from the existing literature? Glob. Health Action 11(1) 1458938. [CrossRef]

- Moretti C, Collaro C, Terzoni C, Colucci G, Copelli M, Sarli L, Artioli G (2022) Dealing with uncertainty. A qualitative study on the illness’ experience in patients with long-COVID in Italy. Acta Biomed: Atenei Parmensis, 93(6): e2022349. [CrossRef]

- Morley G., Grady C., McCarthy J., Ulrich CM (2020). Covid-19: Ethical challenges for nurses. Hastings Center Report, 50(3), 35-39. [CrossRef]

- Newdick C, Danbury C (2015) Culture, compassion and clinical neglect: probity in the NHS after Mid Staffordshire. J. Med. Ethics 41(12) 956-962. [CrossRef]

- Ofili OU (2014) Patient satisfaction in healthcare delivery - a review of current approaches and methods. Eur. Sci. J. 10(25). [CrossRef]

- Parsons Leigh, J., Kemp, L.G., de Grood, C. et al. (2021) A qualitative study of physician perceptions and experiences of caring for critically ill patients in the context of resource strain during the first wave of the COVID-19 pandemic. BMC Health Serv Res 21:374. [CrossRef]

- Paterson R (2002) The patients’ complaints system in New Zealand. Health Aff. 21(3) 70-79. [CrossRef]

- Pearce M, Wilkins V, Chaulk D (2021) Using patient complaints to drive healthcare improvement: a narrative overview. Hosp Pract 49(sup1) 393-398. [CrossRef]

- Pottier B (1974) Linguistique Générale, Théorie et Description [General Linguistic, Theory and Description]. Paris: Klincksieck.

- Pyo J, Lee W, Choi EY, Jang SG, Ock M (2023) Qualitative research in healthcare: necessity and characteristics. J Prev Med Public Health 56(1) 12. [CrossRef]

- Råberus A, Holmström IK, Galvin K, Sundler AJ (2019) The nature of patient complaints: a resource for healthcare improvements. Int J Qual Health C. 31(7) 556-562. [CrossRef]

- Rastier F, Cavazza M, Abeillè A (2002) Semantics for Descriptions. Chicago University Press.

- Reader TW, Gillespie A, Roberts J, (2014) Patient complaints in healthcare systems: a systematic review and coding taxonomy. BMJ Qual. Saf. 23(8) 678-689. [CrossRef]

- Rosa RG, Falavigna M, da Silva DB, Sganzerla D, Santos M MS, Kochhann R.... Brazilian Research in Intensive Care Network BRICNet (2019) Effect of flexible family visitation on delirium among patients in the intensive care unit: the ICU visits randomized clinical trial. Jama 322(3) 216-228. [CrossRef]

- Roy SK, Lassar WM, Ganguli S, Nguyen B,Yu X (2015) Measuring service quality: a systematic review of literature. Int. J. Serv. Econ. Manag. 7(1):24-52. [CrossRef]

- Salvatore S, Tonti M, Gennaro A (2017). How to model sensemaking. A contribution for the development of a methodological framework for the analysis of meaning. In M Han, C. Cunha (Eds.) The Subjectified and Subjectifying Mind Charlotte NC: Information Age Publishing, 245–268.

- Salvatore S. Gennaro A. Auletta A. F. Tonti M. and Nitti M. (2012). Automated method of content analysis: a device for psychotherapy process research. Psychother. Res. 22 256–273. [CrossRef]

- Santana IR, Mason A, Gutacker N, Kasteridis P, Santos R, Rice N (2023) Need, demand, supply in health care: working definitions, and their implications for defining access. Health Econ. Policy Law 18(1), 1-13. [CrossRef]

- Schembri S., Sandberg J (2011) "The experiential meaning of service quality" Mark. Theory 11(2):165-186. [CrossRef]

- Schneider H, Palmer N (2002) Getting to the truth? Researching user views of primary health care. Health Policy Plan. 32-41. [CrossRef]

- Schroeder K, Bertelsen N, Scott J, Deane K,. Dormer L, Nair D... Brooke N (2022) Building from patient experiences to deliver patient-focused healthcare systems in collaboration with patients: a call to action. Therapeutic Innovation & Regulatory Science 56(5) 848-858. [CrossRef]

- Sheahan L, Brennan F (2020) What matters? Palliative care, ethics, and the COVID-19 pandemic. J Bioeth Inq 17(4) 793-796. [CrossRef]

- Siciliani L, Moran V, Borowitz M (2014) Measuring and comparing health care waiting times in OECD countries. Health policy 118(3) 292-303. [CrossRef]

- Simpson E L, House A O (2002) Involving users in the delivery and evaluation of mental health services: systematic review. Bmj 325(7375) 1265. [CrossRef]

- Smith RC, Dwamena FC, Fortin AH (2005) Teaching personal awareness. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 20 201-207. [CrossRef]

- Stewart M (2001) Towards a global definition of patient centred care: the patient should be the judge of patient centred care. Bmj 322(7284) 444-445. [CrossRef]

- Taylor DM, Wolfe R, Cameron PA (2002) Complaints from emergency department patients largely result from treatment and communication problems. Emerg. Med. 14(1) 43-49. [CrossRef]

- Telatar TG, Telatar A, Hocaoğlu Ç, Hızal A, Sakın M, Üner S (2022) COVID-19 Survivors’ Intensive Care Unit Experiences and Their Possible Effects on Mental Health: A Qualitative Study. J Nerv Ment 210(12):925-929. [CrossRef]

- Traiki TAB. AlShammari SA, AlAli MN, Aljomah NA, Alhassan NS. Alkhayal KA... Zubaidi AM (2020) Impact of COVID-19 pandemic on patient satisfaction and surgical outcomes: A retrospective and cross sectional study. Ann. Med. Surg. 58 14-19. [CrossRef]

- van Mook WN, Gorter SL, Kieboom W, Castermans MG, de Feijter J, de Grave WS... van der Vleuten C P (2012) Poor professionalism identified through investigation of unsolicited healthcare complaints. Postgrad. Med. J. 88(1042) 443-450. [CrossRef]

- Venuleo C, Gelo O, Marinaci T, AURORA@COVID19-EU team (2022). Manual for Direct Agents – Articulating a Unified Response to the Covid-19 Outbreak Reconstruction After Loss in Europe. Available at https://auroragriefcovid19.eu/. Accessed 17 April 2024.

- Venuleo C, Guacci C (2014). The general psychologist. A case study on the image of the psychologist’s role and integrated primary care service expressed by paediatricians and general practitioners. Psicol. Salute 1, 73–97. [CrossRef]

- Venuleo C, Marinaci T, Savarese G, Venezia A (2023) Images of the Patient–Physician Relationship Questionnaire (IPPRQ): An Instrument for Analyzing the Way Patients Make Sense of the Relationship with the Physician. In Salvatore S, Veltri GA, Mannarini T (Eds) Methods and Instruments in the Study of Meaning-Making. Springer Cham. [CrossRef]

- Vermeir P, Vandijck D, Degroote S, Peleman R, Verhaeghe R, Mortier E... Vogelaers D. (2015). Communication in healthcare: a narrative review of the literature and practical recommendations. Int. J. Clin. Pract. 69(11), 1257-1267. [CrossRef]

- Visetti YM, Cadiot P (2002) Instability and the theory of semantic forms: starting from the case of prepositions. In Feigenbaum S., Kurzon D (Eds) Prepositions in their Syntactic Semantic and Pragmatic Context - Typological Studies in Language Amsterdam: John Benjamins Publishing Company), 9–40. [CrossRef]

- You JJ, Downar J, Fowler RA, Lamontagne F, Ma I,W. Jayaraman D... Canadian Researchers at the End of Life Network (CARENET. (2015) Barriers to goals of care discussions with seriously ill hospitalized patients and their families: a multicenter survey of clinicians. JAMA Intern. Med. 175(4) 549-556. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).