Study 1 was conducted in person and participants filled out basic demographic questionnaires, a problem-solving ability questionnaire, and several other questionnaires including emotional intelligence and positive problem-solving attitudes. Participants also completed an autobiographical event memory form in which they recalled and described two pleasant and two unpleasant problem-solving and non-problem-solving events and rated the initial affect, current affect, and rehearsals for those events. Study 1 tested the hypotheses that were mentioned at the end of the general introduction.

2.1.1. Method

Participants

The final sample of the current study consisted of responses from 284 participants who attended a small, public university in the southeastern United States. The participants for this study were recruited through Sona Systems (SONA), which is an online scheduling system used to record research participation credit and allow students to view and register for studies at their university. Data were collected from the Fall of 2020 to Fall of 2022. After recruitment, participants were provided with a scheduled time for an in-person lab study. The participants included undergraduate students from a small, public, southeastern university who were enrolled in a psychology class. Participants received class credit for their participation. The demographic composition of the sample primarily included Caucasian (78%), Christian (63%) women (55%). The study received approval from the internal review board (IRB) of the university. Accordingly, participants were treated with the guidelines as specified by the American Psychological Association (APA, 2023), which included briefing, consent, and debriefing. Participants were informed that they could leave the study at any time without penalty, and they were told that their data would be kept confidential under lock and key.

Materials and Measures

The materials included a consent form, which contained a briefing, a general description of the procedures, as well as contact information for the principal investigator, the IRB chair, and counseling services. The consent form also provided a place for participants to sign their names. The questionnaires assessed general demographic information (e.g., age, race, sex, religion, and sexual orientation) and the 40-item Mini Markers (Big Five; Saucier, 1994), which included our targeted neuroticism measure. The questionnaires also included the 20-item positive and negative affect schedule (PANAS; Watson et al., 1988), the brief, 21-item depression, anxiety, and stress scale (DASS; Lovibond & Lovibond, 1995), the 10-item Grit scale, the 19-item Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI; Buysse et al. 1989), the 33-item Schutte Self Report Emotional Intelligence Test (SSEIT; Schutte et al. 1998), the 30-item Inventory of Problem-Solving Abilities scale (IAPSA; Tsai, 2010), which assessed attitudes about problem-solving abilities, and the self-reported, problem-solving and non-problem-solving events questionnaire. For each event, the event questionnaire asked for the date of event occurrence, a brief, four-line, event description, the initial event affect (at occurrence), and the final event affect (currently/at test), as well as three different rehearsal ratings.

The 40-item Mini Markers scale. The brief version of the Big Five Personality Factors was utilized as the first psychological measure in this study. This measure is also known as the 40-item Mini Markers Scale (Saucier, 1994). This item is designed to measure the participants' openness, conscientiousness, extraversion, agreeableness, and neuroticism. For this study, however, only neuroticism was used. This sub-questionnaire lists various self-descriptive terms (e.g., energetic, imaginative, moody, bashful). Participants were asked to rate the extent to which they felt these terms described themselves on a scale ranging from 1 (extremely inaccurate) to 9 (extremely accurate). Two items had to be reversed scored, and then average neuroticism was calculated with high scores indicating high neuroticism. Cronbach’s alpha for neuroticism was .713.

Positive and Negative Affect Schedule (PANAS). The Positive and Negative Affect Schedule (PANAS; Watson et al., 1988) measures positive and negative affect with 20 questions about positive and negative emotions and the extent to which they have been felt by the participant in the last hour. Scores range from 1 (very slightly or not at all) to 6 (extremely). An example of one of the questions is “nervous” or “determined.” The items' scores were averaged; Cronbach’s alpha for the Positive PANAS scale was .844, and Cronbach’s alpha for the Negative PANAS scale was .808.

Brief Depression, Anxiety, and Stress Survey (DASS-21). The brief Depression, Anxiety, and Stress Scale (DASS-21; Lovibond & Lovibond, 1995) was used to measure participants’ depression, anxiety, and stress, as these variables have been negatively related to the FAB in past research (e.g., Gibbons et al., 2017). The questionnaire included statements about depression, anxiety, and stress in which participants rated the strength the statement applied to themselves. Scores ranged from 0 (did not apply to me at all) to 3 (applied to me very much or most of the time). An example statement is “I felt that life was meaningless.” Certain items pertain to stress, anxiety, or depression, and these certain items were added and scored with low scores indicating low levels of the relevant emotion. The scores from the items were averaged and Cronbach’s alpha for the depression portion of the DASS-21 scale was .882. Cronbach’s alpha for the anxiety portion of the DASS-21 scale was .762. The Cronbach’s alpha for the stress portion of the DASS-21 scale was .738.

Grit. The Grit Scale (Duckworth et al., 2009) uses 10 statements about grit. An example statement is “I have overcome setbacks to conquer an important challenge.” Participants indicated the degree that each statement resonated with them on a 5-point Likert-type scale with responses ranging from 1 (not at all) to 5 (very much). The odd-numbered items on the scale were asked in the opposite way as the even-numbered items. Therefore, the answers to the odd-numbered questions were reversed-scored and the average was calculated for the entire scale. Cronbach’s alpha for the GRIT scale was .811.

Sleep. The Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI; Buysse et al. 1989) is a questionnaire with open-ended questions and Likert-type statements used to measure sleep quality and sleep disturbances. The open-ended questions approached the sleep duration with four questions, such as “during the past month, what time have you usually gone to bed at night?” Additionally, the seven closed-ended questions asked for the frequency of sleep disturbances with statements, such as, “during the past month, how often have you had trouble sleeping because you cannot get to sleep within 30 minutes?” Answers were given on a 4-point Likert-type scale ranging from 1 (Not during the past month) to 4 (Three or more times a week). Furthermore, participants were given a space to name any disturbance not named by the questionnaire, with a scale to provide the frequency the item was experienced. The scores from the items were averaged and Cronbach’s alpha for the PSQI scale was .685.

Emotional intelligence. The Schutte Self Report Emotional Intelligence Test (Schutte et al., 1998) is a 33-item questionnaire that measures emotional intelligence. An example statement is “I have control over my emotions.” Responses ranged from scores of 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). Certain items were reverse scored with low scores indicating high levels of emotional intelligence. The scores from the items were averaged and Cronbach’s alpha for the SSEIT was .815.

Positive problem-solving attitudes. The Inventory for Attitudes to Problem-Solving Ability (IAPSA; Tsai, 2010) is a 30-item scale that measures attitudes to problem-solving ability. Participants indicate the extent to which they feel an item applies to them on a scale from 1 (never) to 5 (always). An example statement is “I can make an independent decision by myself.”. Certain items were reverse scored with low scores indicating high attitudes to problem-solving ability. The scores from the items were averaged and Cronbach’s alpha for the IAPSA was .717.

Fading affect and rehearsal for events. The questionnaire prompted participants to describe eight events: two pleasant problem-solving events, two unpleasant problem-solving events, two pleasant non-problem-solving events, and two unpleasant non-problem-solving events. The order in which participants rated the different events was counterbalanced using a Latin square. As each kind of event, created by crossing event type and event affect, included two events, participants dated, described, and rated both events, and then they moved on to the next kind of event in the Latin square. Each event was rated for initial and current affect and rehearsals. Unpleasant events were initially rated on a single-item -3 (very unpleasant) to -1 (slightly unpleasant) scale and pleasant events were initially rated on a single-item 1 (slightly pleasant) to 3 (very pleasant) scale. The initial rating for pleasant events was positive, and the initial rating for unpleasant events was negative. Both unpleasant and pleasant events were rated for their current (at test) affect on the same single-item scale ranging from -3 (very unpleasant) to 3 (very pleasant). The current rating for an event could be positive, negative, or neutral. If event affect changed, participants wrote the amount of time it took for that change to occur in days, hours, minutes, and seconds.

For initially pleasant events, fading affect was calculated by subtracting the current affect from the original affect. For initially unpleasant events, fading affect was calculated by subtracting initial affect from the current affect. These calculations ensured that positive fading affect meant that event affect reduced over time, whereas negative fading affect meant that event affect increased over time. Each event was also rated for the frequency it was thought about, talked about, or both combined with a single-item scale ranging from 0 (never/infrequently) to 6 (always/very frequently). We initially examined fading affect for the 2267 events provided by participants but affect ratings and event descriptions were not provided for some events or event descriptions, or they were incorrectly rated, which resulted in 2121 remaining, usable events.

Procedure

Participants signed up for the study through SONA, and they were provided a timeslot to complete the in-person study. Upon arrival, participants received a consent form, in which they were informed that their consent was being sought for participation in the research study, their participation was completely voluntary, and they were allowed to stop the study at any time without any negative repercussions. Participants were also briefed on the fact that the study examined the emotions tied to pleasant and unpleasant event memories involving and not involving problem-solving, as well as rehearsal ratings for these events. Participants were told that they should only provide events that do not cause emotional pain and, therefore, the experimental procedure should provide no known risks to them.

Participants were informed that the experiment would demand up to 90 minutes of their time and they would receive equitable class credit for their participation. Participants were told that the information that they provided was confidential and would only be examined by research assistants or the Principal Investigator of the study. Participants were also informed that their data were encrypted and placed under lock and key. Participants were then given the contact information of the Principal Investigator and the Chair of the IRB. Participants were also given the contact information of the university counseling center to be used in the unlikely case that they experienced emotional discomfort. After receiving all the information in the briefing, participants signed the consent form before engaging in the procedure.

Following the briefing, participants completed a packet of questionnaires, which included general demographics, personality, mood, psychological distress, grit, emotional intelligence, positive problem-solving attitudes, and sleep quality. Then, participants recalled an event, they provided information about the event, and then they repeated that procedure for another event that was the same kind of event. The four kinds of types included pleasant and unpleasant problem-solving and non-problem-solving events. Participants were told that problem-solving events involved an attempted solution (e.g., my car broke down, so I fixed it), and non-problem-solving events involved no attempted solution (e.g., simply drinking coffee). The participants were told that they had to describe events from their perspective, and the events had to involve the participant.

For each event, participants reported the date that the event occurred (as specific as possible), and they wrote a brief, four-line, event description disclosing as much information as they felt comfortable sharing. Participants then provided an initial/original emotion for the way they felt at the time of the event. Participants were told that unpleasant events should initially be rated using a negative number ranging from -3 (very unpleasant) to -1 (mildly unpleasant) and pleasant events should be initially rated using a positive number ranging from 1 (mildly pleasant) to 3 (very pleasant). Participants were asked to rate the way they currently (at test) felt about the event, and they rated their current emotion on a scale ranging from -3 (very unpleasant) to +3 (very pleasant). Participants then provided the frequency they thought about the event, talked about it, and both thought and talked about it on a rating scale ranging from 0 (never/infrequently) to 6 (always/very frequently). Finally, participants rated whether event affect had stopped changing, and they recorded the amount of time in days, hours, minutes, and seconds required for that change to finish, or they could mark that their event affect was still changing. Finally, participants were given a debriefing form, they were asked to read it in its entirety, and they were asked if they had any questions. Participants were given credit through SONA following their debriefing.

The four kinds of events were presented in an order that was counterbalanced using a Latin square, which created four order conditions. The first order consisted of two pleasant problem-solving events, two pleasant non-problem-solving events, two unpleasant problem-solving events, and two unpleasant non-problem-solving events. The second order consisted of two pleasant non-problem-solving events, two unpleasant non-problem-solving events, two pleasant problem-solving events, and two unpleasant problem-solving events. The third order was the reverse of the second order and the fourth order was the reverse of the first order. Similarly, the rehearsal ratings were presented in one of two orders. Specifically, the combined thinking and talking rehearsals occurred either first or last with the individual rehearsals always beginning with thinking rehearsals followed by talking rehearsals. These counterbalancing controls created eight different order conditions in the study.

Analytic Strategy

For each analysis, each event was the unit of analysis. Unusable data were removed and not analyzed. We first tested the two-way interaction of initial event affect (pleasant vs. unpleasant) and event type (problem-solving and non-problem solving) on both fading affect and initial affect intensity using a 2 (Initial Event Affect) x 2 (Event Type) completely between-groups analysis of variance with initial event affect (pleasant or unpleasant) and event type (problem-solving or non-problem-solving) as the independent variables. Follow-up independent groups t-tests were used to examine interactions if they were significant. We then employed the Process macro via IBM SPSS (Hayes, 2013) to test for two-way and three-way interactions involving initial event affect and continuous variables as predictors of fading affect. For any statistically significant finding for these interaction analyses produced by the Process macro, we reported the indirect effect, the corresponding standard error, t-value, p-value, 95% CI lower- and upper-estimates, as well as effect size at each level of the moderators.

We used Model 1 of the Process macro to examine fading affect, y, across initial event affect, x, conditional upon levels of self-reported individual difference variables, w. These variables included neuroticism, positive and negative PANAS, depression, anxiety, stress, grit, poor sleep via the PSQI, talking rehearsals, thinking rehearsals, and talking and thinking rehearsals, as well as self-reported emotional intelligence (SSEIT), and problem-solving ability attitudes (IAPSA). In Process Model 1, we controlled a nominal-level participant variable to control for clustered data in each model. We used the Johnson-Neyman technique to indicate where along an individual difference variable the FAB was weak or strong, which avoids drawing an arbitrary line to determine “low” and “high” groups (Preacher et al., 2006).

To test for any significant three-way interactions, we again utilized the Process macro to examine fading affect, y, among four categories of events across the spectrum of the individual difference variables. Specifically, Model 3 enabled the specification of the two-way interaction between initial event affect, x, and event type or positive problem-solving attitudes (IAPSA) or emotional intelligence (SSEIT), m, while controlling for the nominal-level, participant variable, conditional upon levels of self-reported individual difference variables, w. These variables included neuroticism, positive and negative PANAS, depression, anxiety, stress, Grit, and poor sleep via the PSQI. We examined fading affect across the spectrum of individual difference variables for each of the four events (pleasant and unpleasant problem-solving and non-problem-solving) using the Johnson-Neyman technique. We also examined the interactive effect of initial event affect and positive problem-solving attitudes (IAPSA) or emotional intelligence (SSEIT) using the Johnson-Neyman technique. The goal of these analyses was to indicate the exact value for the variable where 1) the effect of event type on FAB was large and small, and 2) the relation of positive problem-solving attitudes (IAPSA) or emotional intelligence (SSEIT) was strong and weak.

We also evaluated possible mediators of the three-way interaction with the Process macro. We examined each of the three event rehearsal frequency ratings as a mediator of significant relations between fading affect and initial event affect (i.e., FAB) to individual difference variables across event type or positive problem-solving attitudes (IAPSA) or emotional intelligence (SSEIT). Process Model 11 enables the replication of the three-way interaction (i.e., Model 3 is tested within Model 11), as well as evaluations of the mediators for this effect. In Model 11, we hypothesized that initial event affect (unpleasant vs. pleasant), x, would interact with event type (problem-solving and non-problem solving), z, or positive problem-solving attitudes or emotional intelligence, z, to predict fading affect, y, across levels of individual difference variables, w, and this effect of x*w*z on y may occur through event rehearsal frequency, m. We reported the conditional indirect effect of x*w*z on y through m, examining the indirect effect of x on y through m at levels of the moderators, w and z. In each model, we tested for mediation in any significant three-way interactions, controlling for the potential influence of participants.

2.1.2. Results

Discrete Two-way Interactions

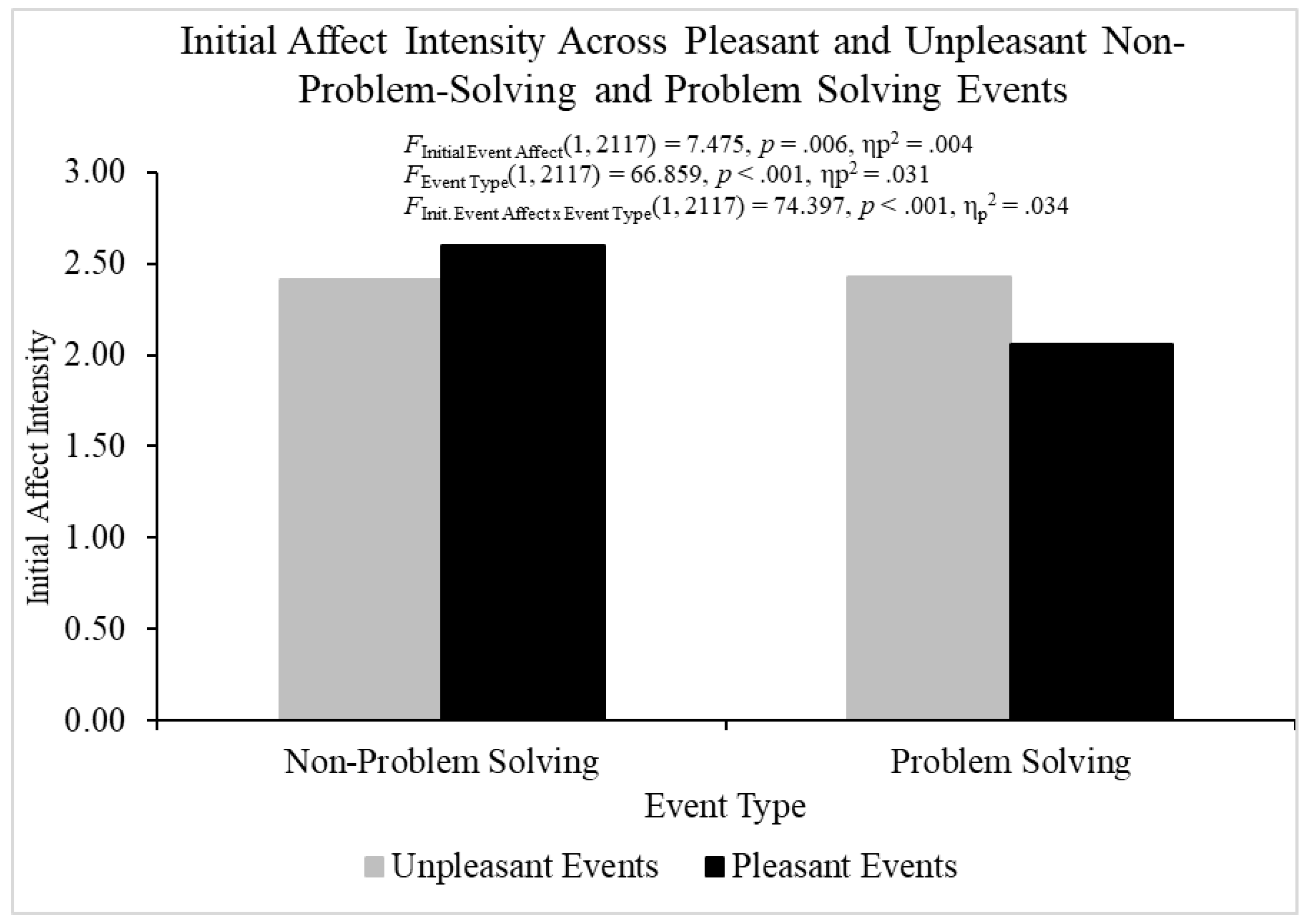

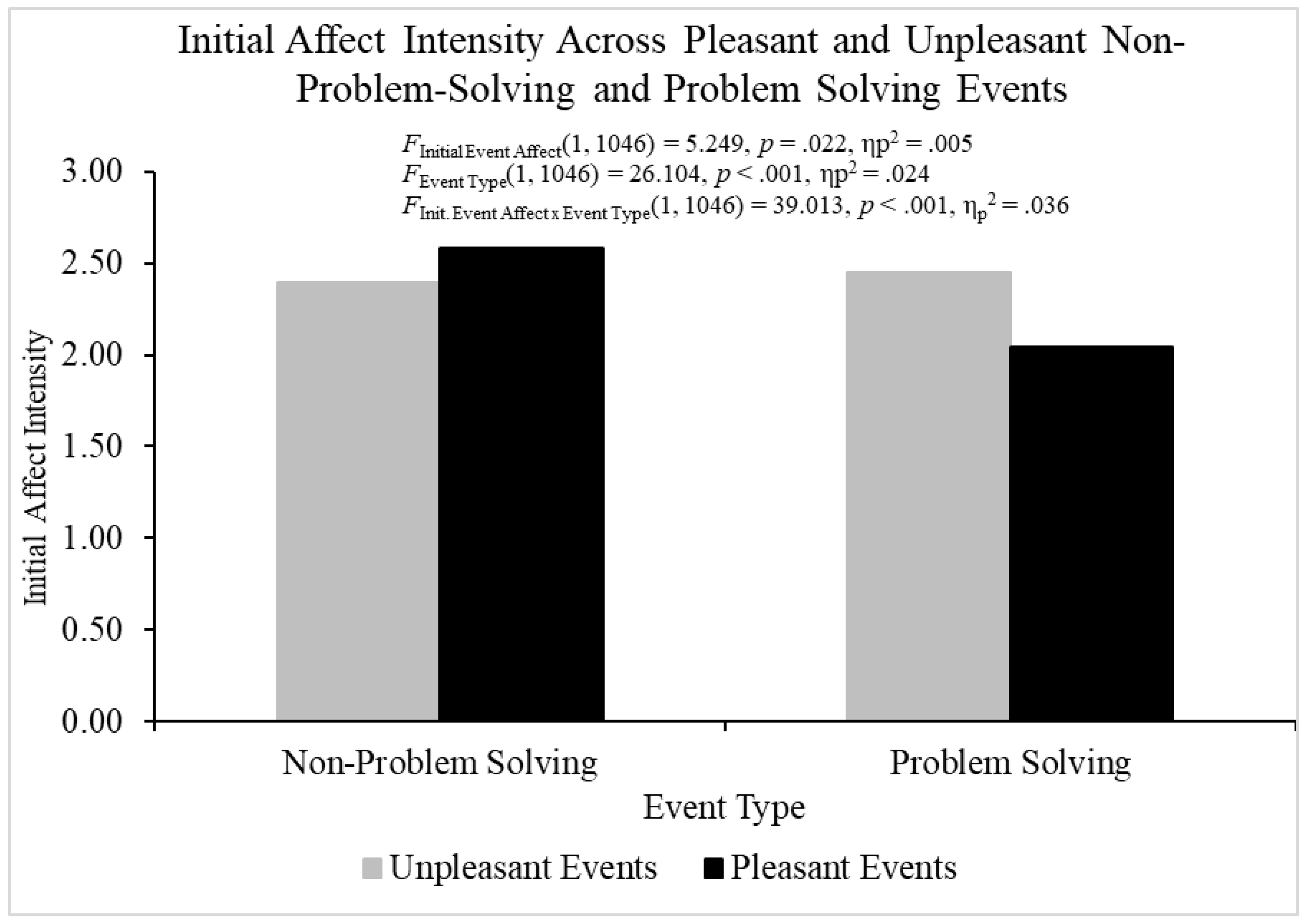

The ANOVA produced heterogeneity, but this parametric assumption violation is not a problem if the sample sizes are relatively equal, defined by a ratio of largest to smallest sample sizes equal or less than 1.5 (Statistics Solutions, 2023). The sample size ratios calculated for initial event affect, event type, and the ratios were all less than 1.5, and, therefore, relatively equal. The overall analysis of variance investigating initial affect intensity was statistically significant, F(3, 2117) = 49.387, p < .001, ηp2 = .065 (

Figure 1). Pleasant events (M = 2.330, SE = 0.023) were initially more intense than unpleasant events (M = 2.418, SE = 0.023), F(1, 2117) = 7.475, p < .01, ηp2 = .004, which does not support regression-to-the-mean as an explanation for FAB effects. The problem-solving events (M = 2.242, SE = 0.024) were initially less intense than the non-problem events (M = 2.506, SE = 0.022), F(1, 2117) = 66.859, p < .001, ηp2 = .031.

The Initial Event Affect x Event Type interaction was statistically significant for initial affect intensity, F(1, 2117) = 74.397, p < .001, ηp2 = .034, and additional analyses were conducted to break down this interaction. For problem-solving events, initial affect intensity was larger for unpleasant (M = 2.425, SE = 0.032) than pleasant events (M = 2.059, SE = 0.035), t(1055) = -7.697, p < .001, ηp2 = .053, but initial affect intensity was smaller for unpleasant (M = 2.411, SE = 0.032) than pleasant (M = 2.600, SE = 0.029) non-problem-solving events, t(1062) = 4.362, p < .001, ηp2 = .018. These results indicated that regression-to-the-mean could potentially explain FAB effects for problem-solving events. Therefore, we statistically controlled for initial affect intensity when conducting all the analyses with fading affect as the dependent variable.

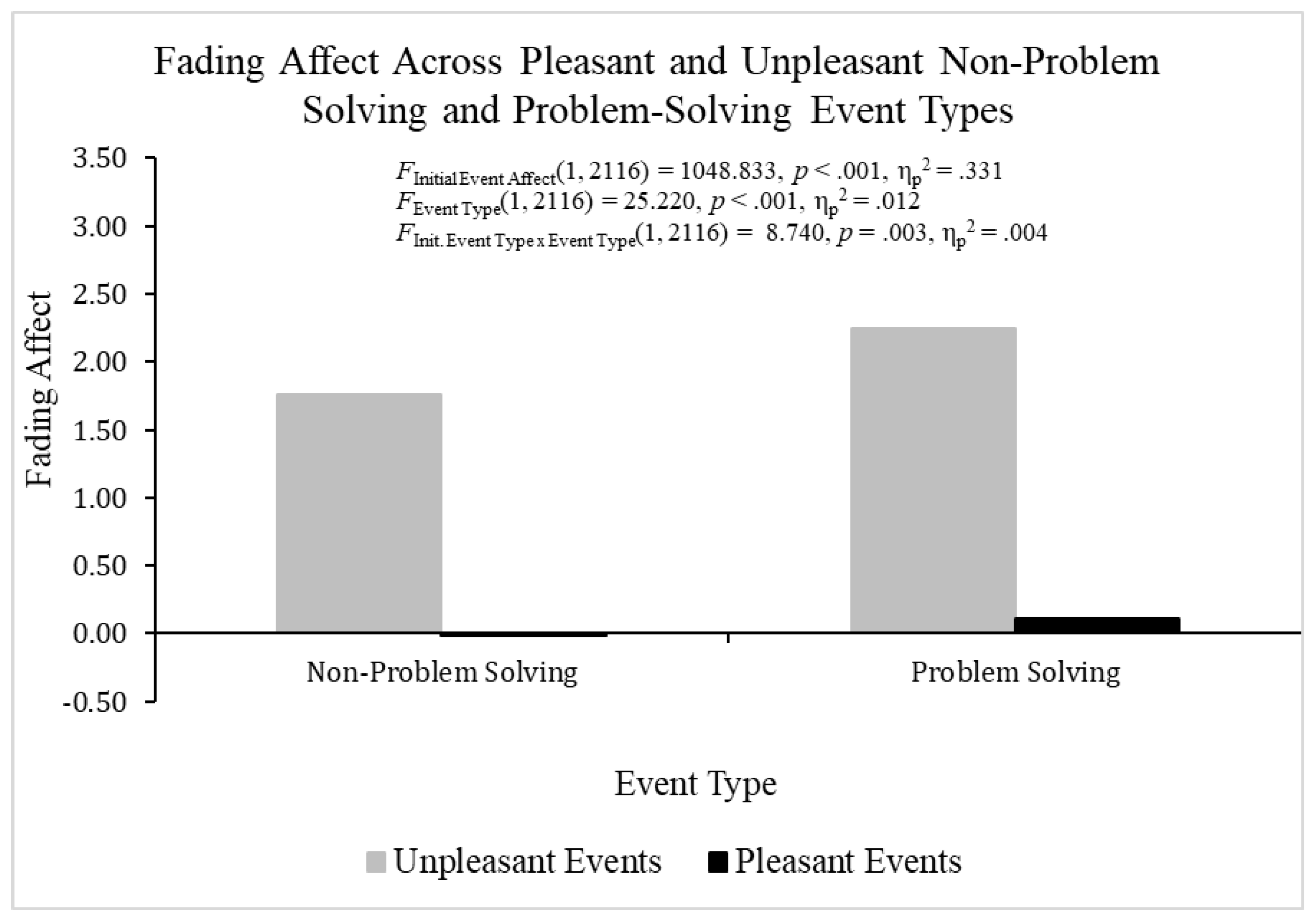

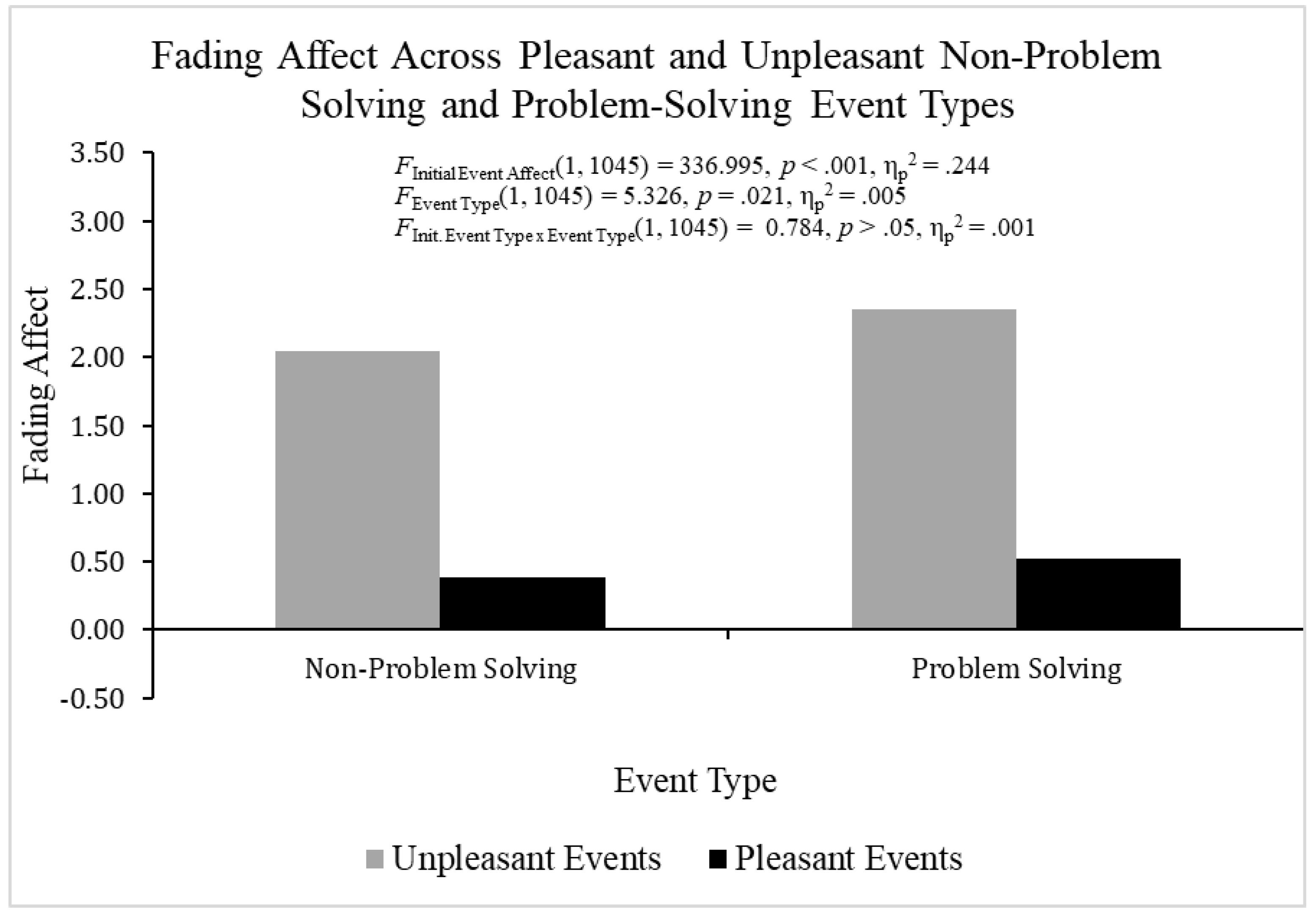

When analyzing FAB effects with fading affect as the dependent variable, heterogeneity was found but it was not an issue for the same reasons mentioned previously. The overall ACNOVA was statistically significant, F(3, 2116) = 363.994, p < .001, ηp2 = .408 (

Figure 2). Pleasant events (M = 0.050, SE = 0.034) showed lower fading affect than unpleasant events (M = 2.001, SE = 0.055), F(1, 2116) = 1048.833, p < .001, ηp2 = .331, which demonstrated a robust FAB. Non-problem solving events (M = 0.872, SE = 0.043) showed lower fading affect than problem-solving events (M = 1.179, SE = 0.043), F(1, 2116) = 25.220, p < .001, ηp2 = .012. The Initial Event Affect x Event Type was statistically significant, F(1, 2116) = 8.740, p < .01, ηp2 = .004. Additional analyses breaking down this interaction showed that the fading affect bias (greater fading affect for unpleasant than pleasant events) was larger for problem-solving events, t(1054) = -22.560, p < .001, ηp2 = .326, than non-problem-solving events, t(1061) = -22.231, p < .001, ηp2 = .318. However, the two events showed small differences in the magnitude of the t-values and the FAB effect sizes.

Continuous Two-Way Interactions

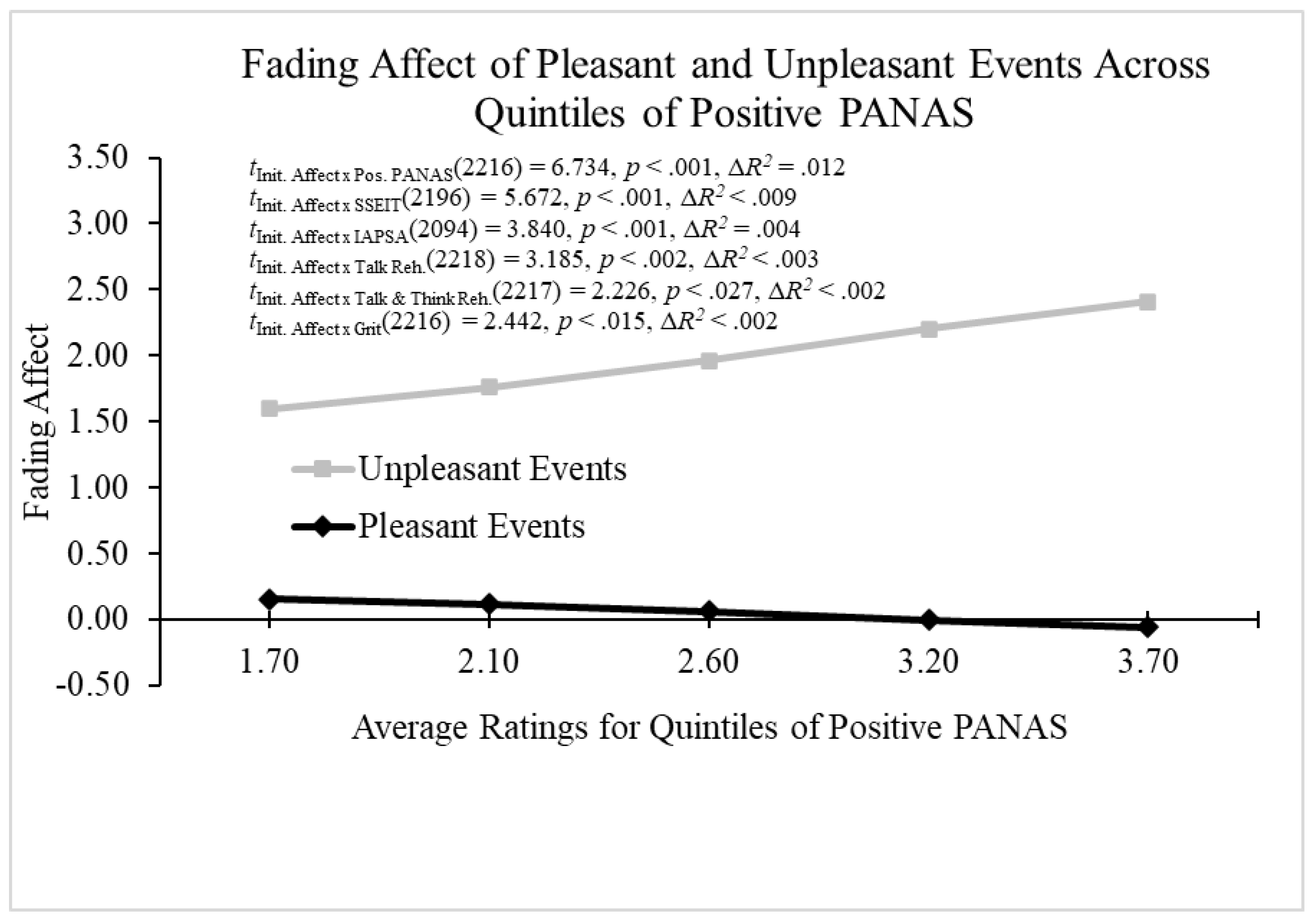

As previously stated, we statistically controlled for initial affect intensity when conducting the analyses with fading affect as the dependent variable. We used Process Model 1 (Hayes, 2022) to examine whether individual difference variables predicted the FAB. These variables included positive PANAS, emotional intelligence, positive problem-solving attitudes, talking rehearsal ratings, thinking and talking rehearsal ratings, grit, neuroticism, negative PANAS, depression, anxiety, stress, and poor sleep. The continuous variables that predicted FAB included talking rehearsal ratings, thinking and talking rehearsal ratings, grit, positive PANAS, emotional intelligence, positive problem-solving attitudes, depression, anxiety, and stress. When observing positive PANAS as a predictor for the FAB, all main effects (initial event affect, positive PANAS, initial affect intensity, and participant) were significant. In addition, the results from Process Model 1 (Hayes, 2022) revealed a significant two-way interaction between positive PANAS and initial event affect, B = 0.511 (SE = 0.076), t(2216) = 6.734, p < .001, 95% CI [0.362, 0.660], Model ΔR2 (due to the two-way interaction) = .012, overall Model R2 = .409, p < .001.

Figure 3 displays that the FAB increased with positive PANAS because fading affect increased for unpleasant events as positive PANAS increased.

When evaluating emotional intelligence (SSEIT) as a predictor for the FAB, the main effects of initial event affect, SSEIT, initial affect intensity, and participant were significant. Additionally, the results from Process Model 1 (Hayes, 2022) revealed a significant two-way interaction between SSEIT and initial event affect, B = 0.883 (SE = 0.156), t(2197) = 5.672, p < .001, 95% CI [0.577, 1.188], Model ΔR2 (due to the two-way interaction) < .009, overall Model R2 = .402, p < .001. The FAB increased with SSEIT because fading affect decreased for pleasant events as SSEIT increased (i.e.,

Figure 3). When observing positive problem-solving attitudes (IAPSA) as a predictor for the FAB, the main effects of IAPSA, initial affect intensity, and participant were significant. In addition, the results from Process Model 1 (Hayes, 2022) revealed a significant two-way interaction between IAPSA and initial event affect, B = 0.776 (SE = 0.202), t(2094) = 3.840, p < .001, 95% CI [0.380, 1.172], Model ΔR2 (due to the two-way interaction) = .004, overall Model R2 < .402, p < .001. The FAB increased with IAPSA, because fading affect decreased for pleasant events as IAPSA increased (i.e.,

Figure 3).

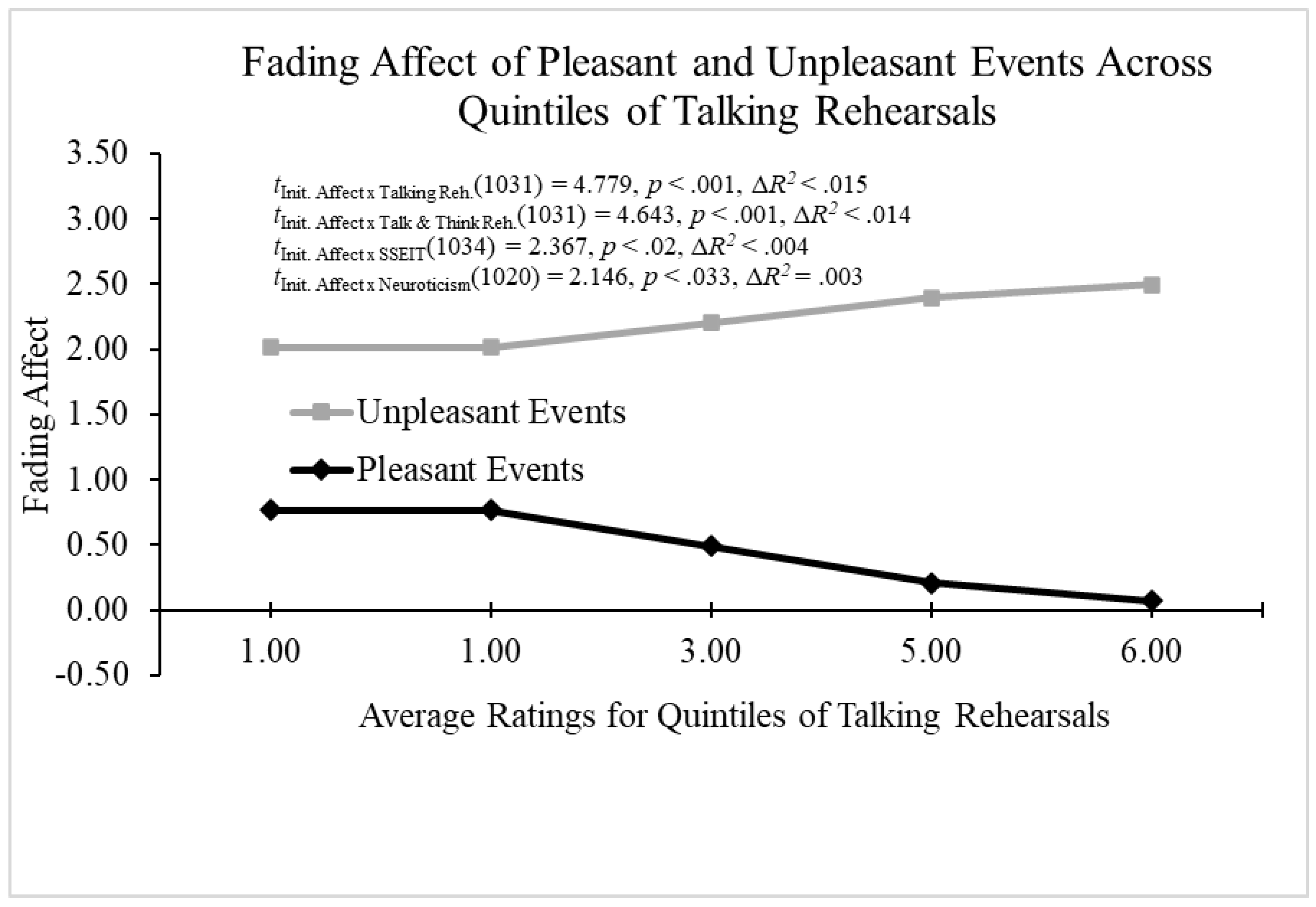

When examining talking rehearsals as a predictor of the FAB, the main effects of talking rehearsals, initial event affect, and initial affect intensity were each significant. More importantly, the results from Process Model 1 (Hayes, 2022) revealed a significant two-way interaction between talking rehearsals and initial event affect, B = 0.103 (SE = 0.032), t(2218) = 3.185, p < .002, 95% CI [0.040, 0.166], Model ΔR2 (due to the two-way interaction) < .003, overall Model R2 = .396, p < .001. The FAB increased with talking rehearsals because fading affect decreased for pleasant events and increased for unpleasant events as talking rehearsals increased (i.e.,

Figure 3). When examining both thinking and talking rehearsals combined as a predictor of the FAB, the main effects of the combined rehearsals, initial event affect, initial affect intensity, and participants were each significant. More importantly, the results from Process Model 1 (Hayes, 2022) revealed a significant two-way interaction between the combined rehearsals and initial event affect, B = 0.075 (SE = 0.034), t(2217) = 2.226, p < .027, 95% CI [0.009, 0.141], Model ΔR2 (due to the two-way interaction) < .002, overall Model R2 = .396, p < .001. The FAB increased with the combined rehearsals because fading affect decreased for pleasant events and increased for unpleasant events as the combined rehearsals increased (i.e.,

Figure 3).

When analyzing grit as a predictor of the FAB, the main effects for initial event affect, grit, and initial affect intensity were significant. In addition, the results from Process Model 1 (Hayes, 2022) revealed a significant two-way interaction between grit and initial event affect, B = 0.230 (SE = 0.094), t(2216) = 2.442, p < .015, 95% CI [0.045, 0.416], Model ΔR2 (due to the two-way interaction) < .002, overall Model R2 = .395, p < .001. The FAB increased with grit because fading affect decreased for pleasant events as grit increased (i.e.,

Figure 3).

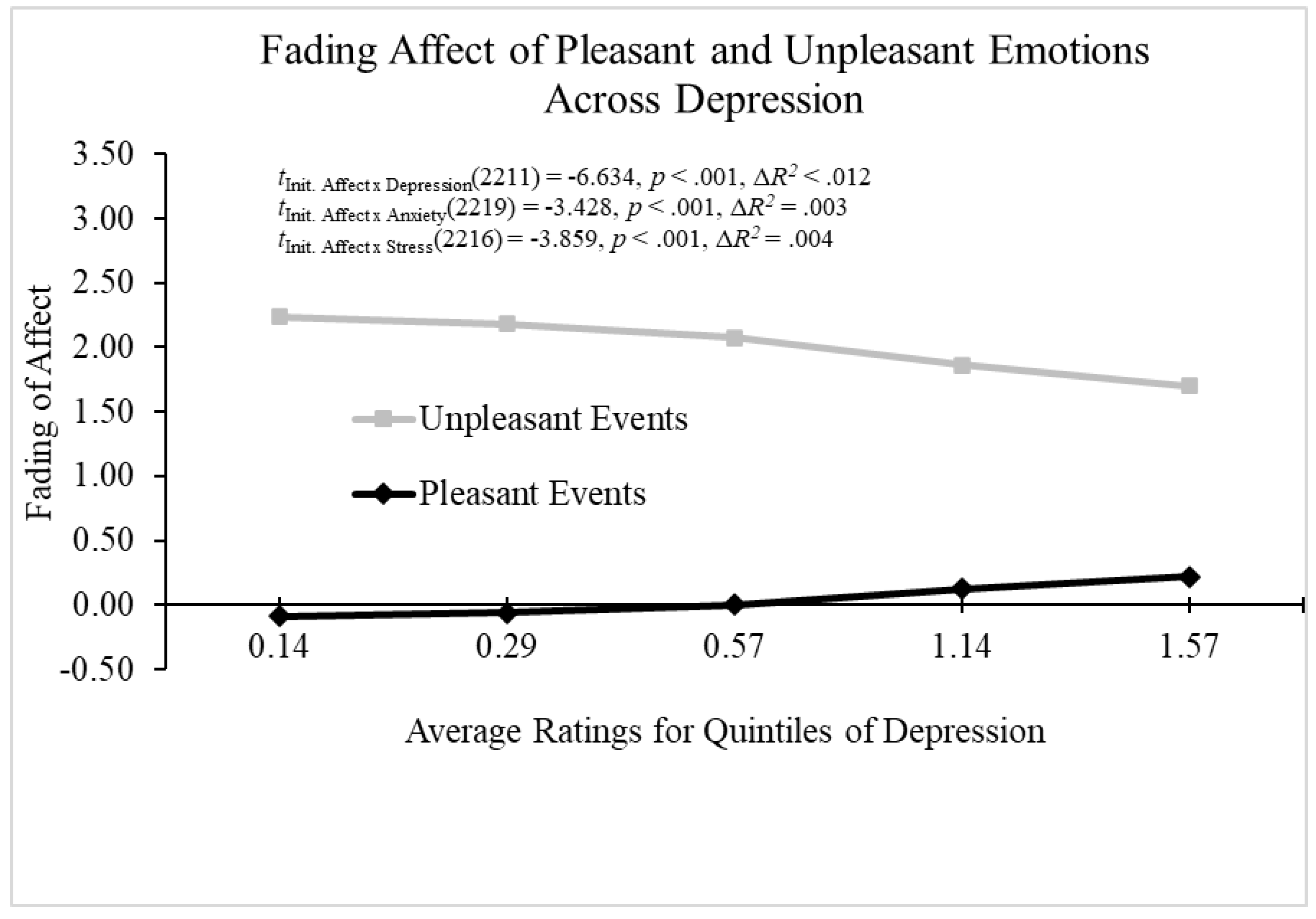

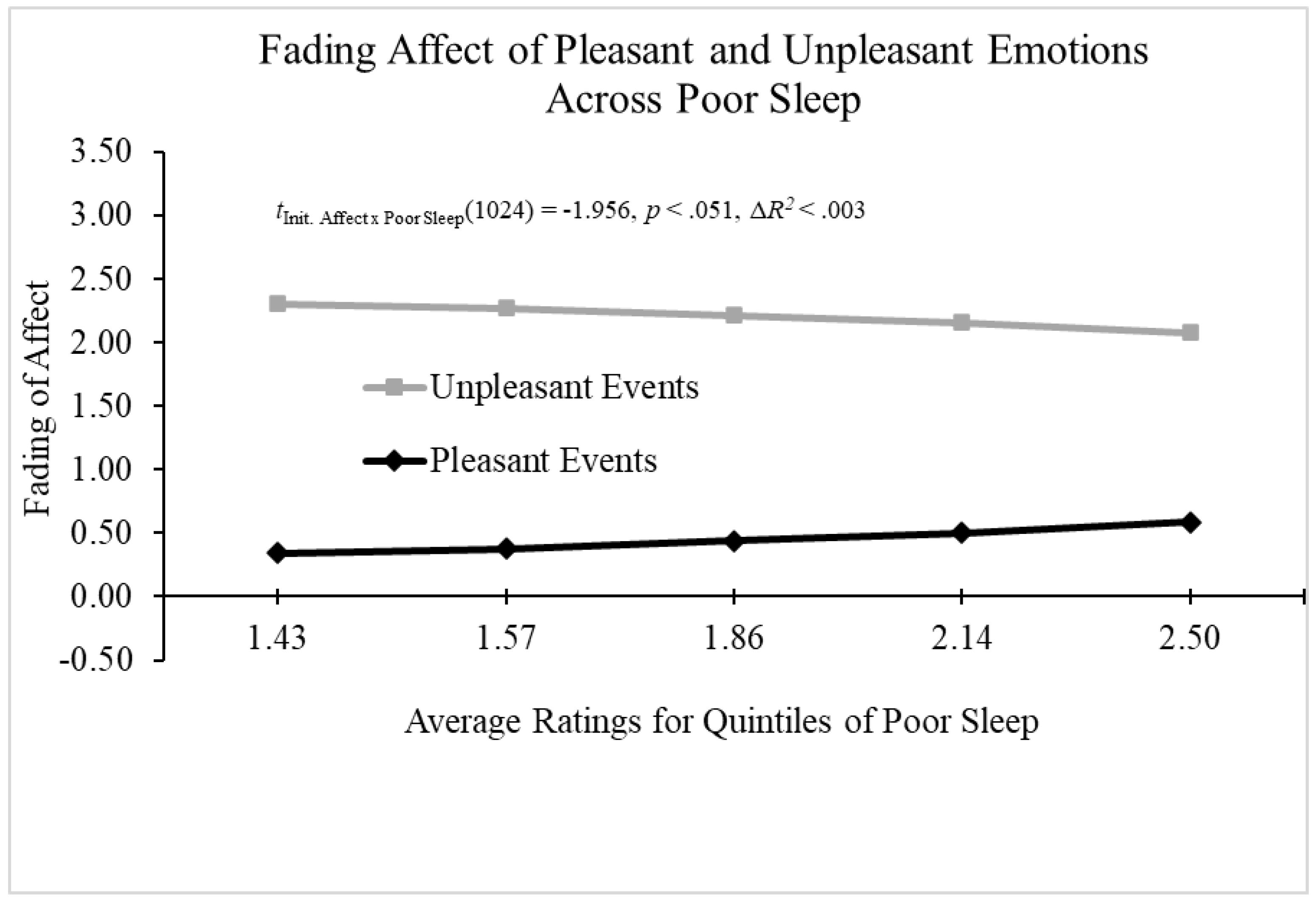

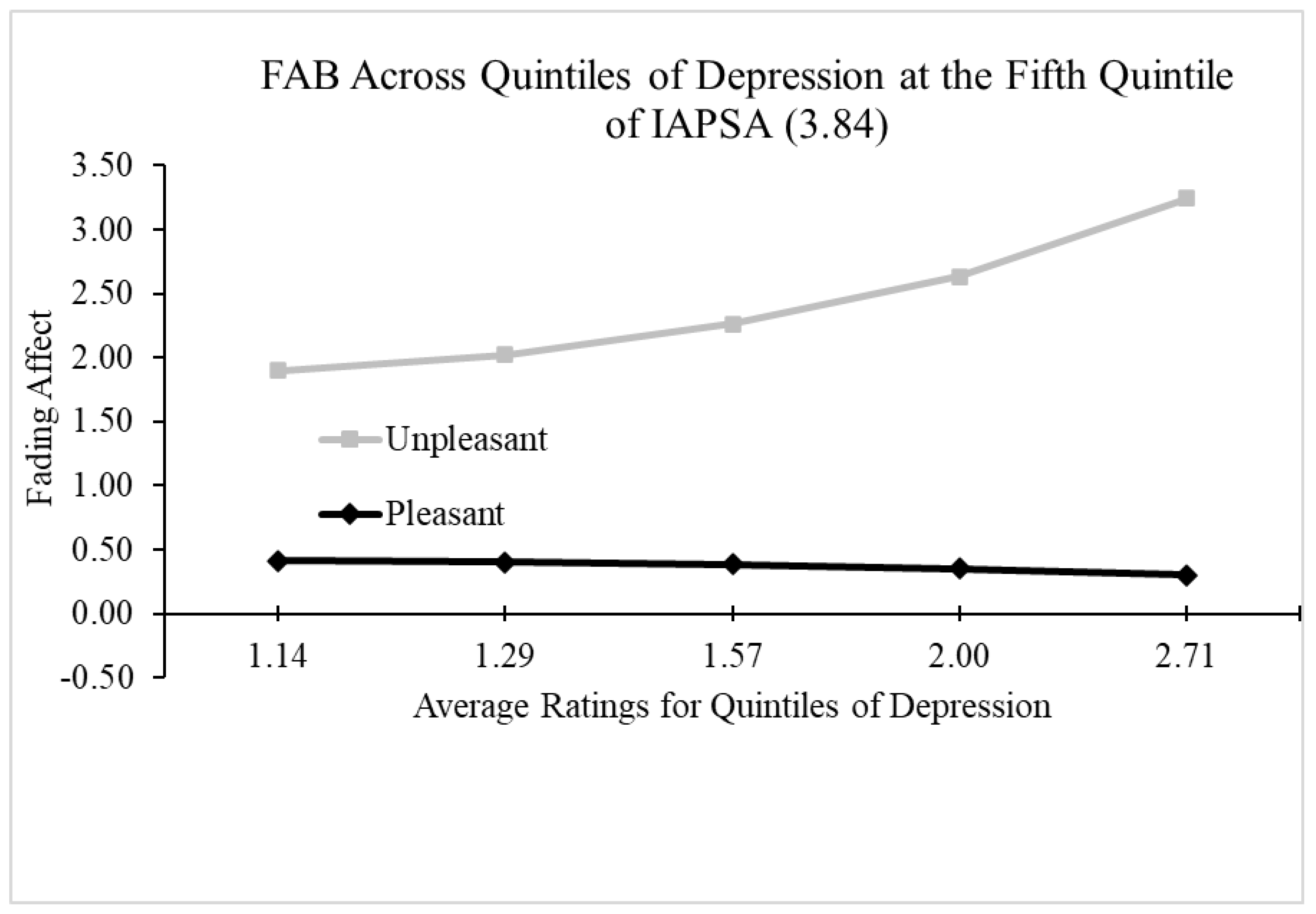

When examining depression as a predictor of the FAB, the main effect of depression and initial event affect were significant. Moreover, the results from Process Model 1 (Hayes, 2022) revealed a significant two-way interaction between depression and initial event affect, B = -0.591 (SE = 0.089), t(2211) = -6.634, p < .001, 95% CI [-0.765, -0.416], Model ΔR2 (due to the two-way interaction) < .012, overall Model R2 < .406, p < .001.

Figure 4 shows that the FAB decreased with depression because fading affect decreased for pleasant events, and it increased for unpleasant events as depression increased. When examining anxiety as a predictor of the FAB, the main effects of initial event affect, anxiety, and initial affect intensity were significant. Importantly, the results from Process Model 1 (Hayes, 2022) revealed a significant two-way interaction between anxiety and initial event affect, B = -0.323 (SE = 0.094), t(2219) = -3.428, p < .001, 95% CI [-0.508, -0.138], Model ΔR2 (due to the two-way interaction) > .003, overall Model R2 = .396, p < .001. The FAB increased with anxiety, primarily because fading affect decreased for unpleasant events as anxiety increased (i.e.,

Figure 4).

When examining stress as a predictor of the FAB, the main effects of initial event affect, stress, and initial affect intensity were significant, but the main effect of participants was not significant. Moreover, the results from Process Model 1 (Hayes, 2022) revealed a significant two-way interaction between stress and initial event affect, B = -0.394 (SE = 0.102), t(2216) = -3.859, p < .001, 95% CI [-0.594, -0.194], Model ΔR2 (due to the two-way interaction) = .004, overall Model R2 = .398, p < .001. The FAB decreased with stress primarily because fading affect decreased for unpleasant events as stress increased (i.e.,

Figure 4).

Continuous Three-Way Interactions

To test for significant three-way interactions, we used the Process macro to examine fading affect, y, among four categories of events across the continuum of the problem-solving and other individual difference variables. Specifically, Model 3 (Hayes, 2022) enabled the specification of the two-way interaction between initial event affect, x, and individual difference variables, m, while controlling for participant and initial affect intensity, conditional upon event type, levels of self-reported positive problem-solving attitudes (IAPSA) or emotional intelligence (SSEIT), w. We also used the Johnson-Neyman technique to detect where the FAB was more strongly related to an individual difference variable (i.e., positive PANAS) for one event type (e.g., problem-solving event) than for another event type, or a particular point on the positive problem-solving attitudes (IAPSA) scale or the emotional intelligence (SSEIT) scale.

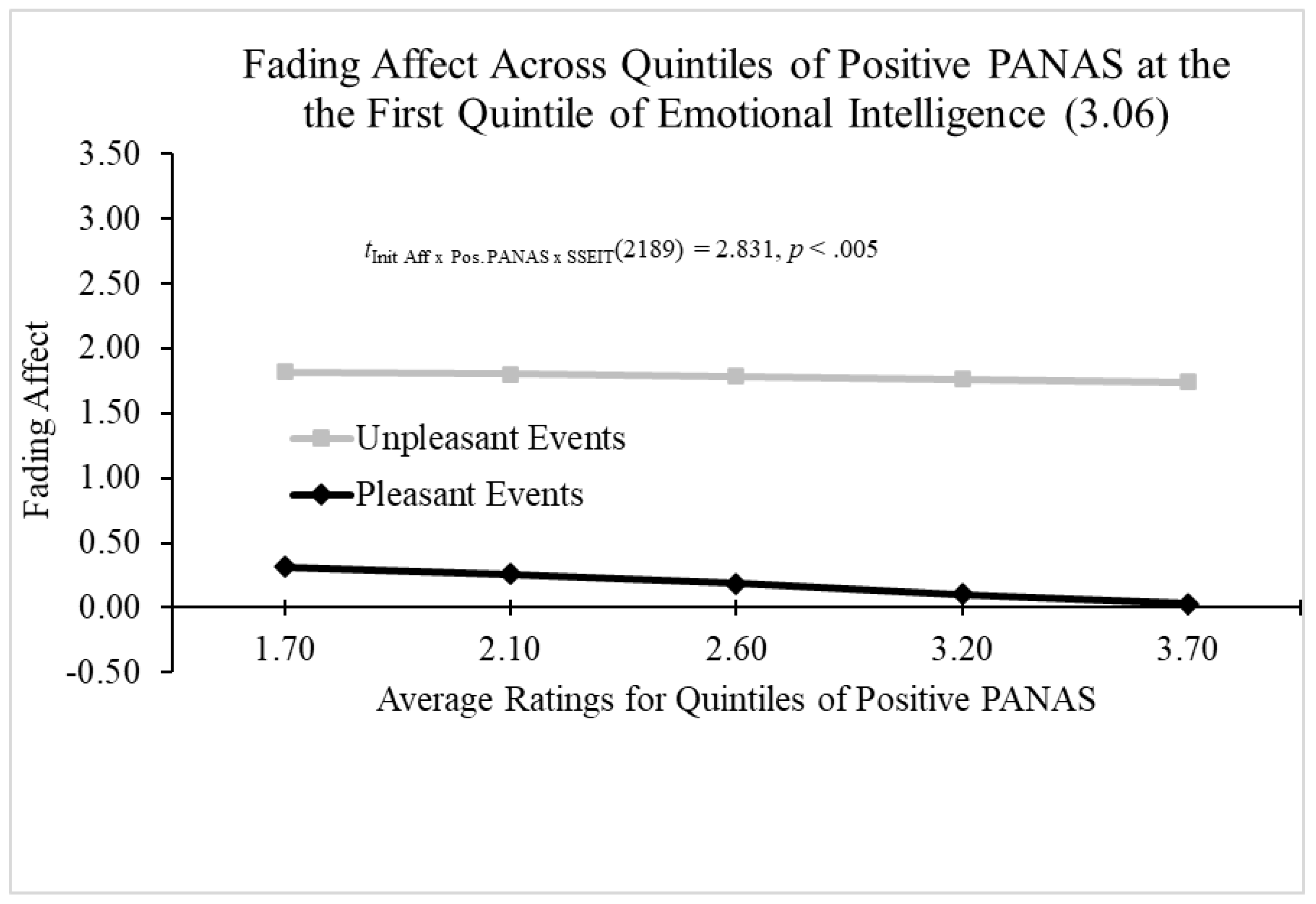

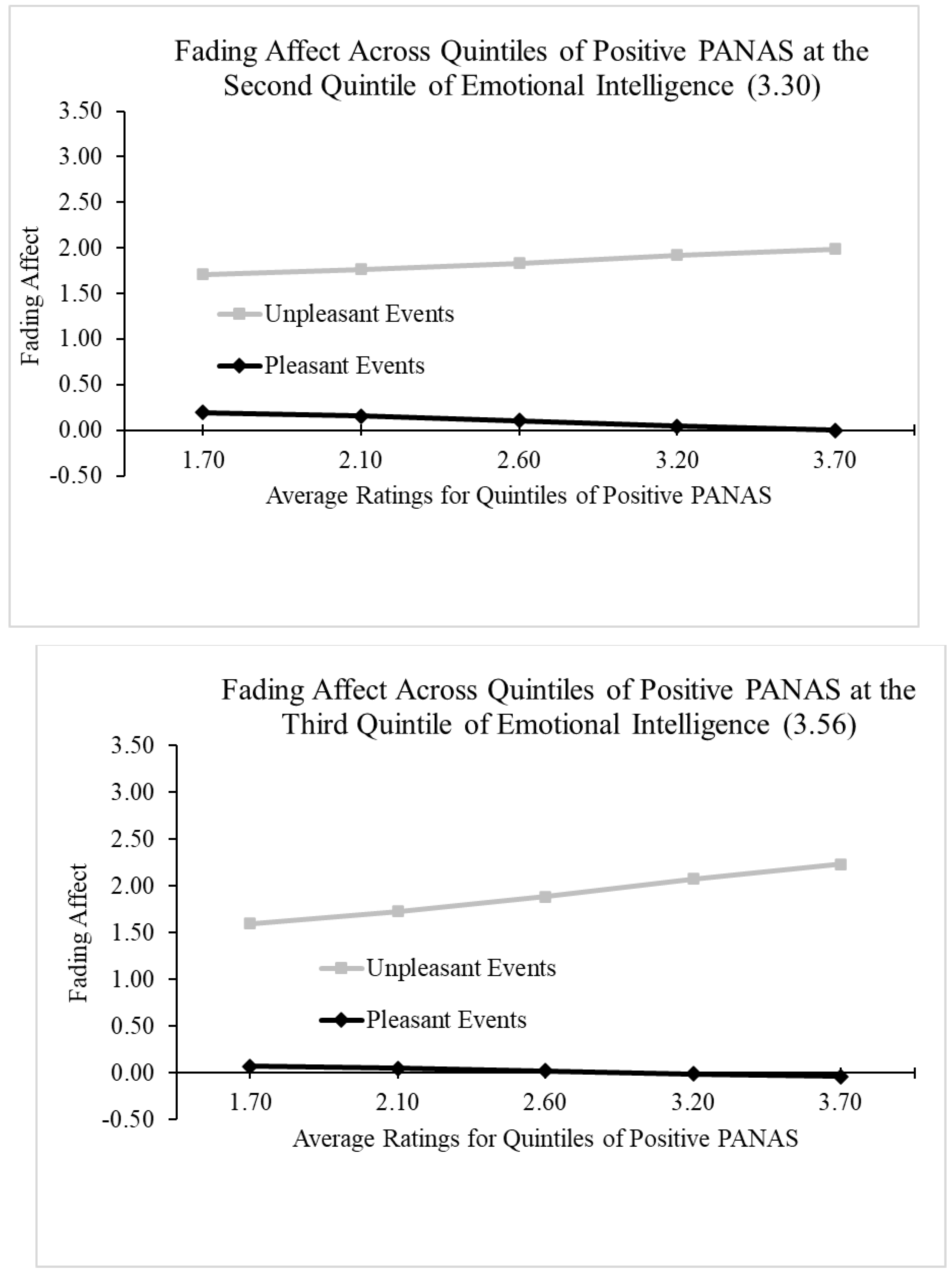

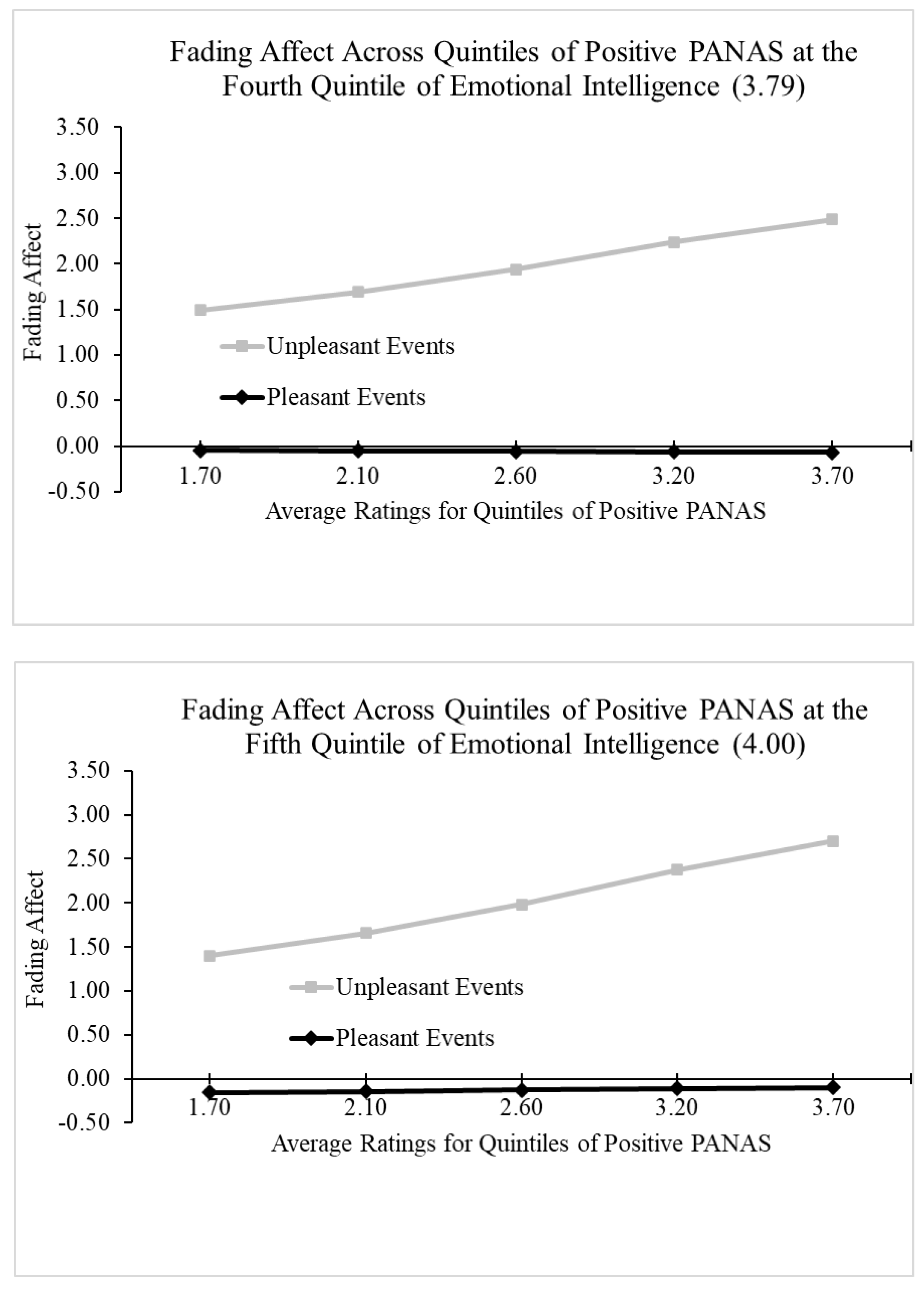

We used the Hayes Process Model 3 (Hayes, 2022) to examine the three-way interaction of initial event affect, positive PANAS, and emotional intelligence (SSEIT) while controlling for initial affect intensity and participant. The model revealed significant main effects of initial event affect, initial affect intensity, and participant, as well as a significant two-way interaction between positive PANAS and initial event affect. Moreover, a significant three-way interaction was found between emotional intelligence (SSEIT), positive PANAS, and initial event affect, B = 0.551 (SE = 0.195), t(2189) = 2.831, p < .005, 95% CI [0.169, 0.932], Model ΔR2 (due to the three-way interaction) > .002, overall Model R2 = .421, p < .001.

Figure 5a-5e and the Johnson-Neyman values showed a non-significant negative relation between FAB and positive PANAS at and after the first quintile of emotional intelligence (SSEIT). Afterward, the relation inverted forming a positive relation between FAB and positive PANAS that became significant before the second quintile of SSEIT at a rating of 3.253 and increased with SSEIT from that point.

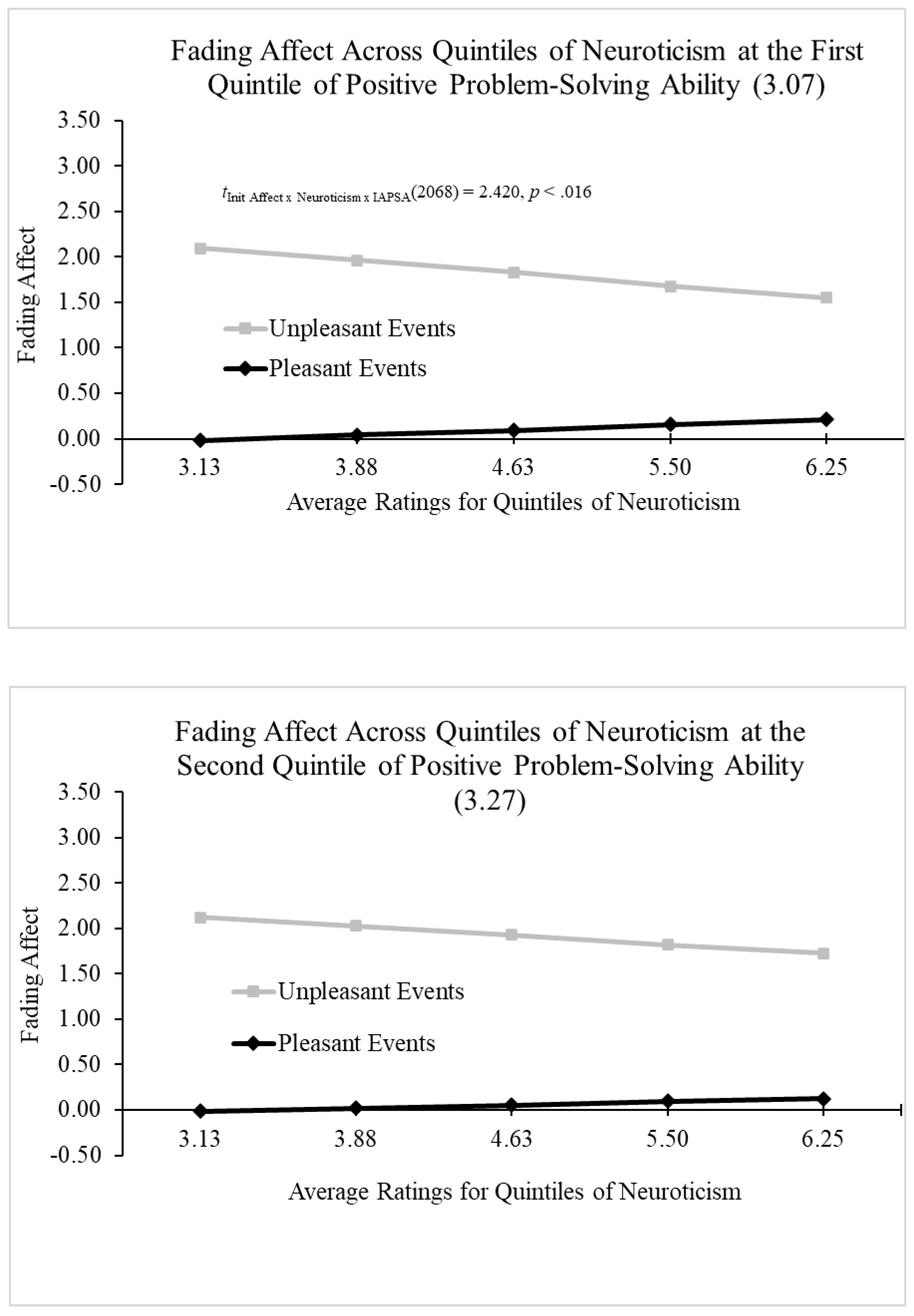

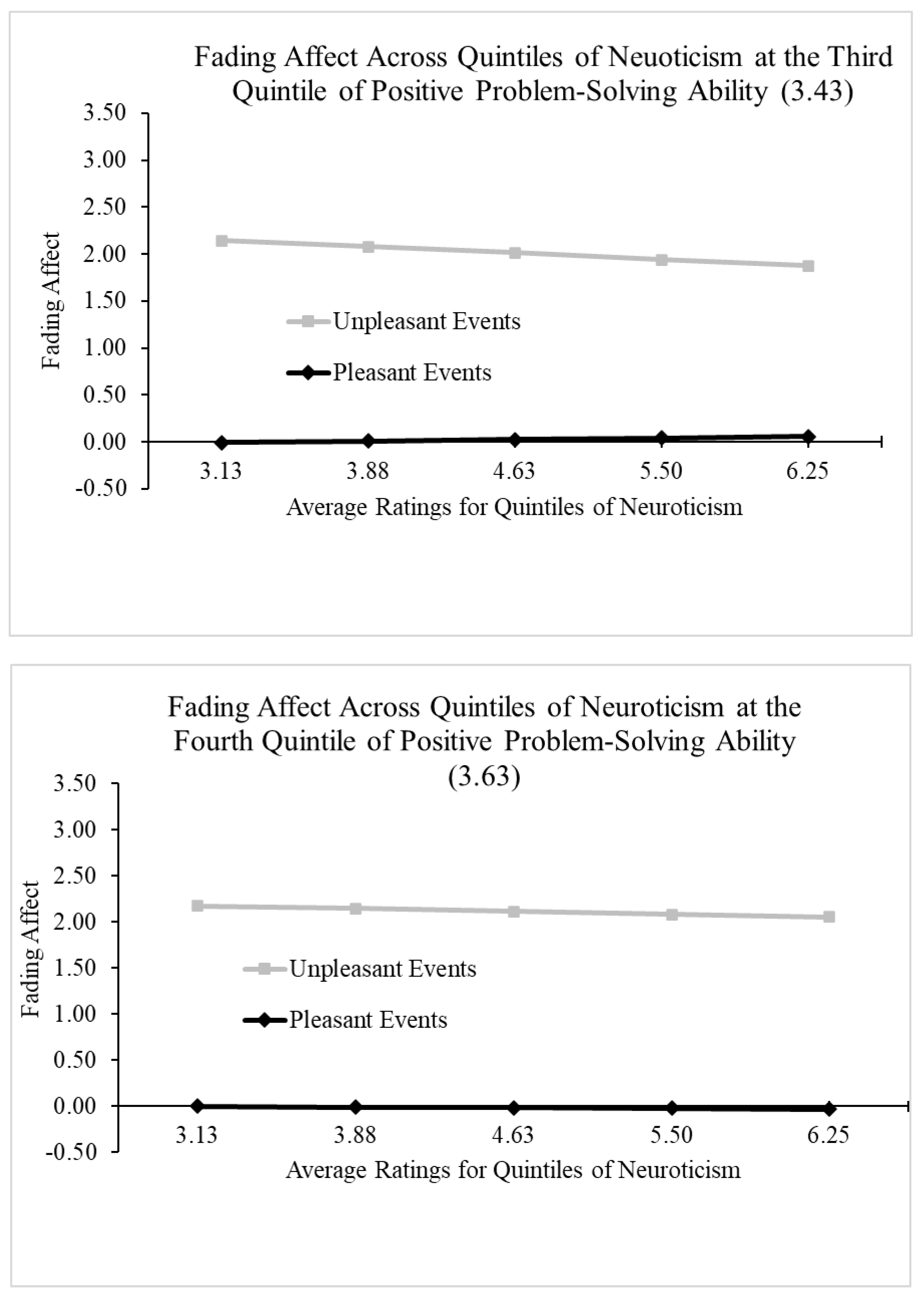

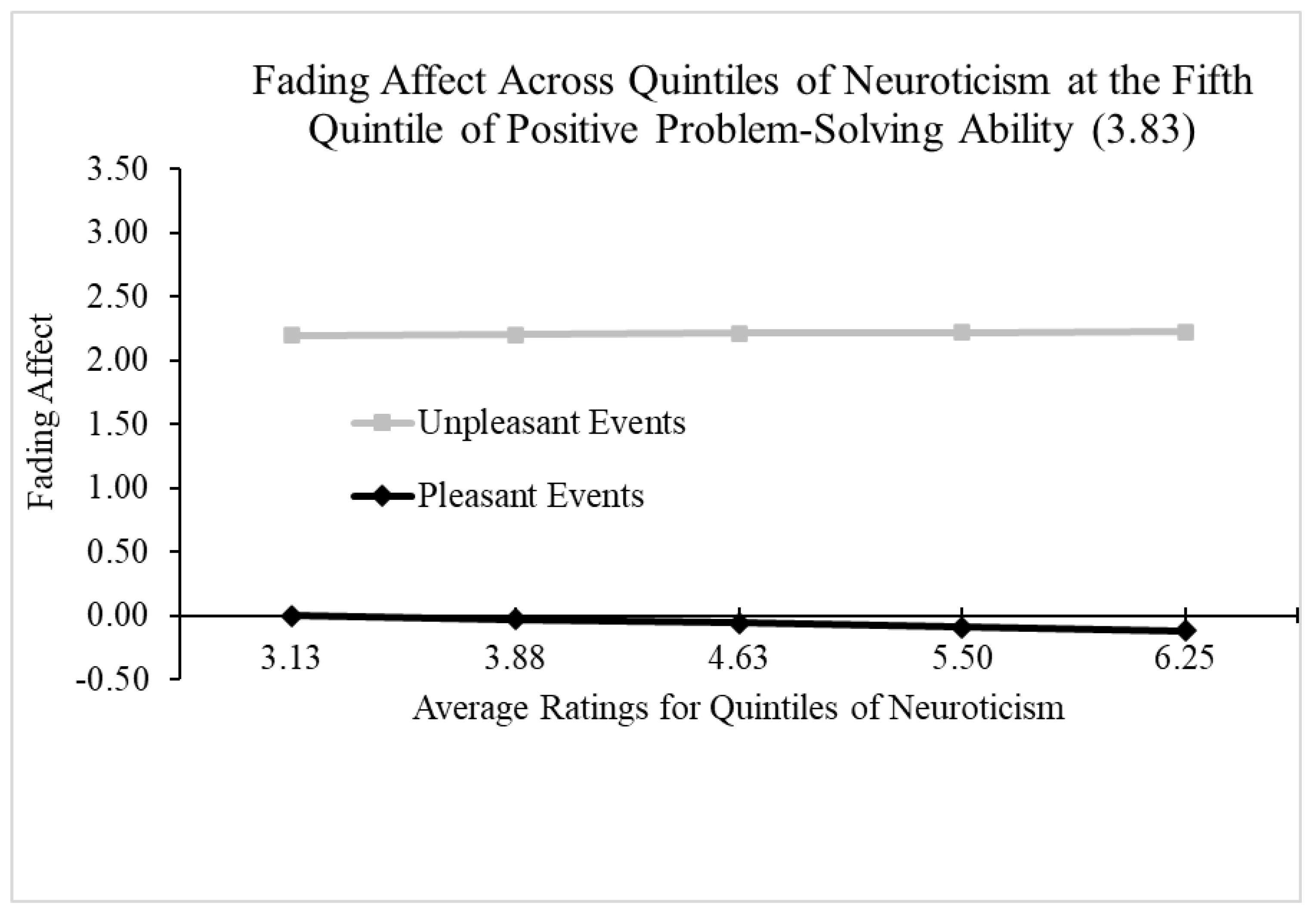

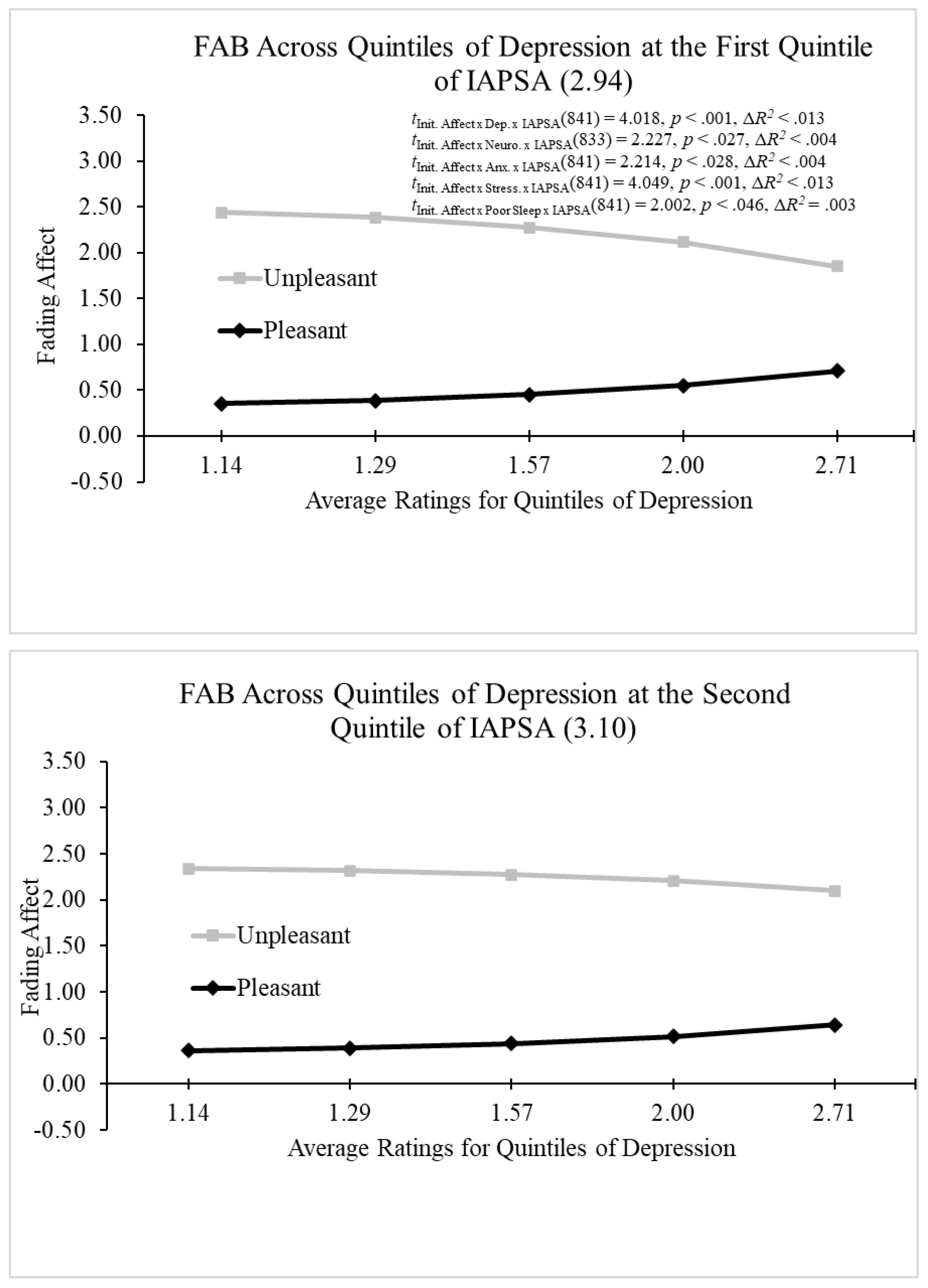

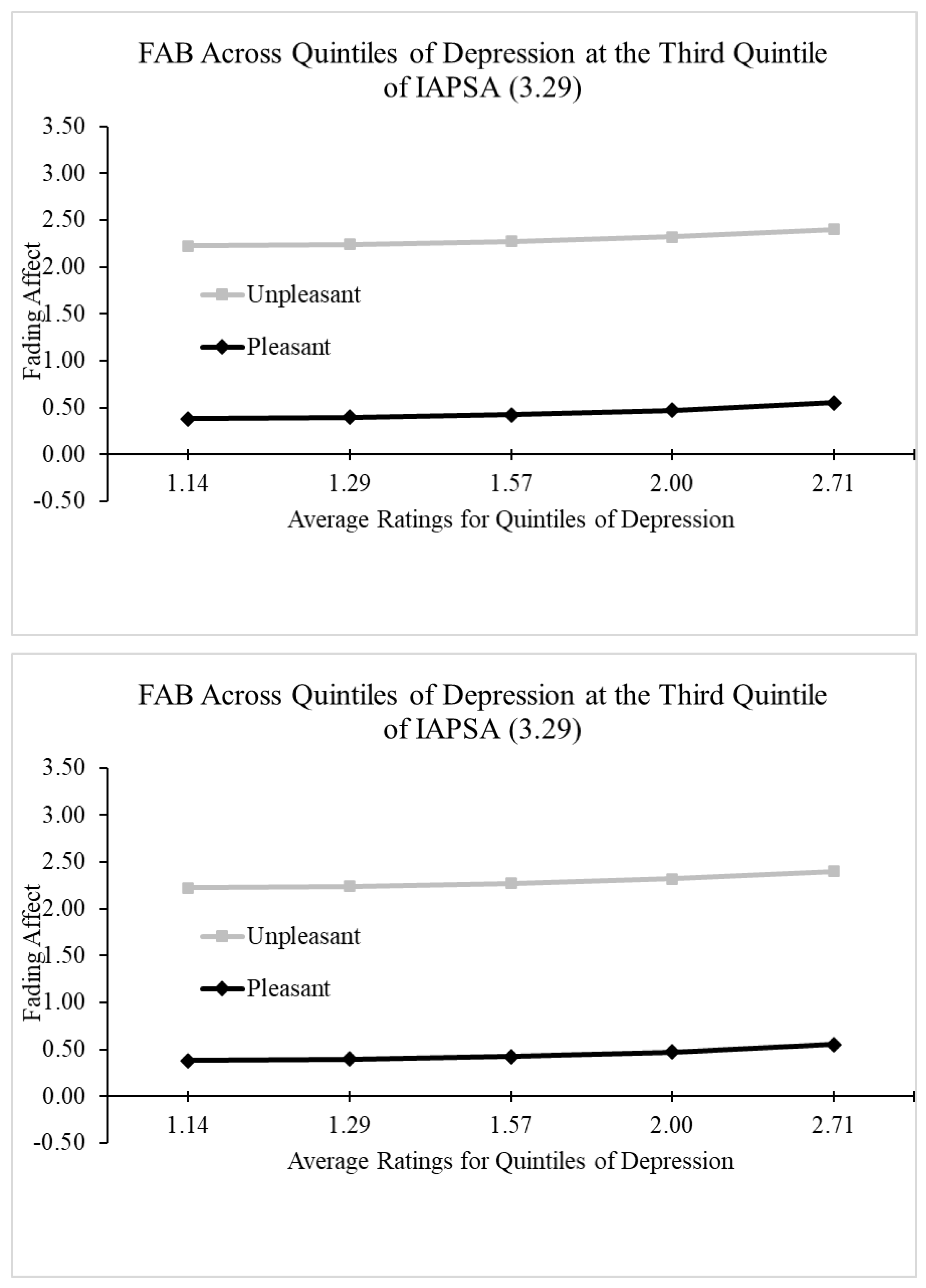

When examining the three-way interaction between initial event affect, neuroticism, and positive problem-solving beliefs (IAPSA), all the main effects were significant in the Hayes Process Model 3 (Hayes, 2022) with the exception of IAPSA. In addition, the two-way interactions were significant with the exception of the initial event affect by IAPSA interaction. More importantly, Model 3 revealed a significant three-way interaction between positive problem-solving attitudes (IAPSA), initial event affect, and neuroticism, B = 0.384 (SE = 0.159), t(2058) = 2.420, p < .02, 95% CI [0.073, 0.696], Model ΔR2 (due to the three-way interaction) < .002, overall Model R2 = .404, p < .05.

Figure 6a-6e and the Johnson-Neyman values initially demonstrated a significant negative relative between FAB and neuroticism that decreased as IAPSA increased and was last significant at IAPSA ratings of 3.434, and that negative relation inverted at IAPSA ratings of 3.792 and increased, but did not come significant, from that point.

Examining Rehearsals as Mediators of the Three-Way Interactions

Next, we found and examined the conditional indirect effects of initial event affect on fading affect for 1) positive PANAS across emotional intelligence (SSEIT) and 2) neuroticism across levels of positive problem-solving attitudes (IAPSA) through rehearsal ratings (talking, thinking, thinking and talking) using the Process Model 11 (Hayes, 2022). The three-way interaction involving fading affect, initial event affect, positive PANAS, and emotional intelligence (SSEIT) was intervened by talking rehearsals at the second and third quintiles of positive PANAS across the second and third quintiles of SSEIT. This same interaction was intervened by thinking rehearsals at the first quintiles of both positive PANAS and SSEIT, and the first and second quintiles of positive PANAS across the second and third quintiles of SSEIT. This interaction was also intervened by thinking and talking rehearsals at the fourth and fifth quintiles of positive PANAS at the first quintile of SSEIT, the second, third, and fourth quintiles of positive PANAS across the second and third quintiles of SSEIT, and the third quintile of positive PANAS at the fourth quintile of SSEIT.

The interaction involving fading affect, initial event affect, neuroticism, and positive problem-solving beliefs (IAPSA) was intervened by talking rehearsals at the second and third quintiles of neuroticism across the third quintile of IAPSA. This same interaction was intervened by thinking rehearsals at the fourth and fifth quintiles of neuroticism across the first and second quintiles of IAPSA, as well as the fifth quintile of neuroticism at the third quintile of IAPSA. The interaction was also intervened by thinking and talking rehearsals at the first and second quintiles of neuroticism across the first, second, and third quintiles of IAPSA.