1. Introduction

Experiential Learning (EL) is defined as learning from direct, personal experience and reflecting on that experience to gain a deeper understanding and apply it to future situations (Kolb & Kolb, 2017). Scholars spanning nearly a century have emphasized the central role of experience in human learning and development (Dewey, 1933; Lewin, 1951; Keaton & Tate, 1978; Kolb & Kolb, 2006; March, 2010). They agree that EL is a dynamic, holistic process involving the whole person and applicable at all societal levels, not limited to traditional classroom settings.

For EL to be beneficial to all participants, it must consider the student's perception of the learning opportunity. Each individual's disposition affects their experience of EL. For instance, a confident, extroverted person will experience an EL opportunity differently than an introverted person. Studies by Dyer and Schumann (1993) and Lengnick-Hall and Sanders (1997) have shown that despite differences in learning styles, experiences, academic levels, and interests, students consistently demonstrate high levels of personal and organizational effectiveness, the ability to apply course materials, and satisfaction with both course results and the learning process.

Ultimately, EL ensures individuals benefit from experiences in ways that enhance the learning of disciplinary content more effectively than traditional learning environments. Importantly, one group of students that has been less extensively studied within the context of EL is students with disabilities, particularly those with "invisible disabilities."

The present study addresses the challenges encountered by students with disabilities during their engagement in EL experiences. The aim is to gain a better understanding of these challenges, with the overarching goal of informing more inclusive pedagogical practices in EL. Such practices are essential to ensure that all students, including those who have disabilities, can equally benefit from EL programming. Certainly, pedagogical practice advocates for a conscientious and scholarly approach to course design. This necessitates thorough consideration of the diverse needs of all potential students to optimize targeted learning outcomes (Austin & Rust, 2015). Such an approach lies at the core of the Scholarship of Teaching and Learning (SoTL) community (Felten, 2013). One effective method to achieve this is by actively soliciting student perspectives on their EL experiences, which in effect encourages self-reflection (Kolb & Kolb, 2017).

Trigwell (2013) underscores the significance of this perspective, emphasizing that comprehension is best achieved through reflection both by the student as well as the instructor, where the latter can explore teaching methodologies that will best produce the desired learning outcomes (Felten, 2013; deBraga et al., 2015; Trigwell, 2013). This reflection involves a comprehensive examination of how EL experiences contribute to students' personal growth within their specific field of study (Wurdinger & Allison, 2017). Consequently, EL necessitates the full engagement of every participant to harness the maximum benefit from the experience (Bradley & Miller, 2010; Brigham et al., 2011; Burgstahler & Corey, 2010; Lawrie et al., 2017).

Research into the impact of EL has made notable strides across various disciplines, particularly in psychology and other health-related fields (Morris, 2020). However, substantial research on the direct influence of EL on the learning process remains relatively scarce (Bergsteiner et al., 2010; Brown et al., 2020; Jarvis, 2012; Morris, 2020). Nonetheless, Burgstahler (2001) has shed light on the positive influence of EL opportunities, illustrating how they correlate with career-related attitudes, knowledge, and skills among university students, including those with disabilities.

Over the years, universities have developed policies to accommodate students with a wide range of disabilities. Universal Design for Learning (UDL) principles have significantly impacted policies aimed at leveling the playing field for all university students. Rooted in flexibility, simplicity, and equity, the UDL framework stands as a pivotal force in ensuring fairness and inclusivity in education (Burgstahler et al., 2010; Edwards et al., 2022). In a recent review of the literature examining the role or impact of UDL, Cumming and Rose (2022) highlighted six key reasons as to why UDL is effective: a) recognition of learner diversity: UDL recognizes that students have unique and diverse needs, challenging the view that students learn in the same way; b) increased engagement and satisfaction: studies have shown that students, both with and without disabilities, have high satisfaction rates with UDL implementation; c) accessibility without singling out: UDL allows students with specific needs to access course materials without the need for accommodations or singling them out; d) improved teaching: Instructors who implement UDL principles in their teaching report that it improves their teaching; e) professional development and training: effective implementation of UDL requires training and support for instructors, highlighting the importance of professional development in UDL and the need for instructors to have access to UDL peer "experts" who can mentor them in applying UDL principles to their practice; and f) guidelines and resources: an emphasis of the importance of following the UDL guidelines provided by the Center for Applied Special Technology (CAST), which organize the implementation of UDL according to three core principles: multiple means of engagement, representation, and expression. These guidelines provide instructors with specific strategies and examples of how to implement UDL in their courses.

By embracing the UDL approach, educators empower themselves to craft instruction that caters to the diverse needs and learning styles of every student, thereby cultivating an environment of inclusivity and support for all learners (Cumming & Rose, 2022; Edwards et al., 2022). Such accommodations conform for the most part to the Social Model of Disability, developed by disability rights activists in the 70s and 80s. According to this model, disability resides within an “oppressive environment” rather than within an individual’s limitations. As such, it is incumbent upon society to provide appropriate services, accommodations, and universally designed environments that remove barriers and enable individuals with disabilities, as well as everyone else, to fully participate in all society has to offer. Universities created accessibility offices and services that ensured that entrances to buildings and washrooms are physically accessible to wheelchair users and now provide reasonable academic accommodations, such as extra time to write exams and submit papers, as well as visual and auditory learning aids that provide a fair and level playing field for students with disabilities (see Shakespeare, 2006 and Bruce & Aylward, 2021). Despite legal requirements of universities to accommodate, it is not always clear to what extent this needs to be effected by faculty, and if so, what their role might be (Saltes, 2020).

The nature and severity of a student's disability is likely to significantly influence their EL experiences. Kowalski et al. (2016) observed that specific disabilities were linked to negative outcomes among university students: anxiety disorders were associated with adverse physical symptoms, while physical disabilities correlated with increased depression, ostracism, and lower self-esteem. Brigham et al. (2011) reported that students with Learning Disabilities (LD) encounter difficulties across multiple domains, including information acquisition, working with numeric data, spoken or written expression, information recall, attention, and motivation—all of which are crucial for successful EL experiences. These challenges, particularly those related to spoken or written expression, can constrain these individuals' ability to demonstrate competence. Moreover, LD often coexist with other impairments, exacerbating the severity of their disabilities and further complicating their learning needs.

Hong (2015) reported that university students with disabilities often face stressors related to physical demands, mental and emotional struggles, and social stigmatization. For instance, minor distractions can trigger heightened anxiety and sensitivity in students with attention deficits or Tourette's syndrome. Additionally, students with diagnosed mental health conditions may contend with medication-related side effects, such as fatigue. These factors underscore the need for a nuanced understanding of the impact of disability on EL experiences. The more severe the symptoms of any disability, the greater the likelihood that the disability will negatively impact a student's ability to engage with and benefit from any educational program, including EL. This becomes even more apparent when considering the inherent challenges associated with a typical EL learning environment, where engagement relies on concrete experiences (Morris, 2020). Implementing such experiences is inevitably more challenging for students with disabilities.

One factor that can significantly impact EL experiences is whether students choose to disclose their disabilities. While disclosure can facilitate a student's access to necessary accommodations, the invisibility of a student's disability may hinder them from receiving the support they require (Cunnah, 2015; Kiesel et al., 2018; Versnel et al., 2008). However, opting not to disclose a disability will prevent students from qualifying for accommodations altogether and may indirectly limit instructors' ability to address explicit curriculum needs (Lund et al., 2014; Versnel et al., 2008).

Several dispositional factors, including self-esteem, locus of control, personality, and adult attachment style, can impact the quality of students with disabilities’ EL experiences. Self-esteem, defined as an individual’s self-evaluations, has been associated with job satisfaction among adults with mild intellectual disabilities, irrespective of their employment setting (Griffin et al., 1996). Additionally, when measured as core self-evaluations, self-esteem is linked to the subjective well-being of university students with disabilities. Higher core self-evaluations tend to correlate with greater acceptance of disabilities, increased social support from significant others, and elevated levels of employment-related and social self-efficacy. These factors are all positively correlated with overall life satisfaction (Smedema et al., 2022).

Locus of control refers to an individual’s attributions regarding their control over the consequences of their behavior (Rotter, 1966). Students with disabilities tend to exhibit an internal attributional style for both positive and negative events (Adams & Proctor, 2010). However, the precise impact of locus of control on the overall well-being of students with disabilities remains uncertain and warrants further investigation, as both internal and external loci have been linked to different positive outcomes (Smedema, 2014; Estrada et al., 2006).

The Big-Five personality framework is a hierarchical model that categorizes personality traits into five domains (Openness to Experience, Conscientiousness, Extraversion, Agreeableness, and Neuroticism). These traits play a role in shaping self-efficacy and outcome expectations when students with LD choose a major (Brown & Cinamon, 2016). Moreover, Big-Five factors can potentially intensify certain disability symptoms that affect EL experiences (Nigg et al., 2002). The association between Big-Five personality traits and the quality of EL experiences necessitates further investigation, with potential correlations with academic motivation and grades (Komarraju et al., 2009).

Adult attachment styles are attachment representations formed during early parent-child bonds, influence individuals' expectations of closeness or separation and subsequently impact their subjective quality of life (Hwang et al., 2009). Among individuals with physical disabilities, a secure attachment style predicts higher self-esteem and greater life satisfaction (ibid.).

Students with disabilities often exhibit lower levels of adjustment, quality of life, and well-being, making them less likely to graduate from university compared to their peers (Tansey et al., 2018). Adjustment and well-being encompass various aspects, including perceived stress, physical symptoms, subjective well-being, and psychological well-being. Perceived stress relates to individuals' perceptions of their lives as unpredictable, uncontrollable, and overwhelming (Hughes et al., 2005). University students with disabilities tend to report higher levels of perceived stress compared to their peers. Those not registered with accessibility services often experience even higher levels of perceived stress (Ardell et al., 2016).

Disability-related variables, such as the nature and severity of mobility limitations and the level of assistance required, have been identified as significant predictors of perceived stress (Hughes et al., 2005). Personality factors, including Big-Five Neuroticism, have been shown to negatively influence physical symptoms among students with disabilities, further affecting their overall well-being (Kowalski et al., 2016). Cunnah (2015) reported that students with disabilities have different experiences in university settings compared to work-based settings, where they are more likely to experience positive identities and a greater sense of inclusion.

Subjective well-being, defined as an individual's current quality of life (Antaramian, 2015), is likely to be influenced by factors such as the mode of EL delivery. Heiman and Olenik-Shemesh (2012) found that students with LD exhibit higher subjective well-being during online courses compared to their peers. This suggests that factors such as the mode of EL delivery may predict the well-being and satisfaction of students with disabilities in EL experiences, which has gained particular relevance since the COVID-19 pandemic.

Psychological well-being diverges from subjective well-being by adopting a more comprehensive perspective, incorporating elements such as identity, significance, and interconnectedness (Grant et al., 2009). Research by Koca-Atabey et al. (2011) suggests that the severity and impact of disability emerge as substantial predictors of psychological well-being among students with physical disabilities. Moreover, other factors, including gender and self-reported health, have been identified as predictors of psychological well-being among residents in assisted-living facilities (Cummings, 2002). Well-being has remained largely underexplored in studies concerning undergraduate students with disabilities, and the quality of their EL experiences even more so.

This study examined the research question: “what is the predictive relationship between disability type and severity, dispositional and well-being factors, and the quality of EL experiences among students with disabilities?” It was hypothesized that at least some demographic and dispositional factors would significantly predict the quality of EL experiences. The findings from this research can provide valuable insights for EL instructors, enhancing their understanding of the unique needs and challenges faced by students with disabilities. This understanding, in turn, can inform the design and implementation of EL courses, ultimately leading to improved experiences and learning outcomes for these students.

2. Method

2.1. Participants

Participants were American and Canadian undergraduate students who self-defined as individuals with disabilities who had taken or were in the middle of completing any of the following courses: (i) Research Opportunity Program (ROP), Independent Research Program (IRP), or thesis courses. Such courses entail a student conducting empirical research in a laboratory under the supervision of a faculty member. (ii) Experiential learning courses involving work placements. Such work-integrated learning and service learning (also recognized as community engaged learning) courses offer academic internships designed to integrate classroom academic learning with learning from practical work-based experiences. (iii) Summer abroad courses. Such courses entail the completion of program and degree credit courses at an international location relevant to the subject matter of the course. All of these courses fit within the institution’s umbrella of EL, and while these courses may differ in general form, they are all subject to the EL paradigm as defined in this study.

2.2. Procedure

EL administrators from the three campuses of the University of Toronto (instructors teaching EL courses, ROP coordinators, Summer Abroad Program officers, etc.) were contacted by email and asked to distribute a recruitment letter to potential participants. It outlined a description of the study, what participation entailed, and compensation. It also contained a link to the online survey (hosted on Qualtrics.com) which consisted of a series of questionnaires examining demographic and dispositional variables, type and severity of disability, and overall adjustment and well-being. The link to the questionnaire was also posted on LinkedIn, Facebook, and Instagram to expand recruitment beyond the University of Toronto. The survey took approximately 30 to 60 minutes to complete. Information and a consent form were provided before participants began the questionnaire. Debriefing information including the purpose and implications of this study, and researcher’s contact information was provided upon survey completion in case participants were interested in receiving study results or had any questions. The survey, procedure, consent and debriefing methods were all approved by the University of Toronto Research Ethics Board (REB).

2.3. Measures

The survey consisted of the following questionnaires: Demographics, Disability Identity, Locus of Control, Self-Esteem, Big Five Personality, Physical Symptoms, Experiential Learning Quality, Subjective Well-Being, and Psychological Well-being.

Basic demographic variables including gender, age, year of study, program(s) of study, current cumulative grade point average, and most recent semester grade point average were requested. A modified version of the Four-Factor Index (Hollingshead, 1975) was used to assess socioeconomic level. This questionnaire assessed participants’ parental occupational classification, educational attainment, and socioeconomic status (SES). A Disability Identity Questionnaire was developed and included questions pertaining to type of disability, when the disability was acquired or diagnosed, whether the disability influenced the student’s choice of specialty or area of focus, whether the disability is visible, accommodations received, reasons or concerns for accessing accommodations, and support received in the community. The World Health Organization Disability Assessment Schedule (WHODAS) 2.0 (Üstün et al., 2010) was utilized to measure severity of disability by assessing difficulties in six domains of functioning due to health or mental health conditions, including understanding and communicating, getting around, self-care, getting along with people, life activities, and participation in society.

Dispositional measures consisted of four questionnaires. The Locus of Control Questionnaire (Lefcourt et al., 1979) assessed concern for success and failure in academic experiences by assessing four sets of cognitive contributions, including internal/stable, internal/unstable, external/stable, and external/unstable. The Rosenberg’s Self-Esteem Scale (Rosenberg, 1965) was utilized to measure global self-worth. The Big Five Personality Questionnaire (John & Srivastava, 1999) assessed five major dimensions of adult personality: openness, conscientiousness, extraversion, agreeableness, and neuroticism. The Adult Attachment Questionnaire (Collins, 1996) assessed three subscales: depend, anxiety, and close.

Overall adjustment and well-being measures consisted of four questionnaires. The Perceived Stress Scale (Cohen et al., 1983) was utilized to measure the degree to which current situations in participants’ lives were appraised as stressful. The Cohen-Hoberman Inventory of Physical Symptoms (CHIPs) (Cohen & Hoberman, 1983) was utilized to assess a variety of physical symptoms and overall health. The Subjective Well-Being Scale (Diener et al., 1985) was utilized to measure satisfaction with life. The Psychological Well-Being Questionnaire (Ryff, 1989) assessed six domains of well-being: self-acceptance, positive relations with others, environmental mastery, autonomy, purpose, and personal growth.

The Experiential Learning Experiences Questionnaire was specifically developed for this study to assess the type and quality of participants’ EL experiences with a special focus on how a student’s experience was impacted by their disability. It included questions on the extent to which the EL supervisor(s) was/were accommodating and knowledgeable regarding disability issues, disability-related barriers (structural, attitudinal, systemic, etc.) both before and during the program, as well as disclosure of disability, and disability-related resources. This questionnaire contained 3 multiple choice questions, four Likert scale type questions, and four open-ended questions. The open-ended questions were used to collect qualitative data, for instance, “What advice would you give the current EL students in the same program with a similar disability?”

2.4. Analytical Strategy

A series of between-subject analyses of variance (ANOVA) were conducted comparing the mean differences in quality of EL experiences between (i) genders, (ii) the primary types of disability (physical/orthopedic, deaf/hard of hearing or hearing impaired, blind or visually impaired, cognitive disability including TBI, Autism, chronic health condition, learning disability, ADHD, psychiatric disability, and other), (iii) EL type, and (iv) EL setting.

A multiple linear regression was conducted to determine whether age, year of study, average SES, disability type, disability severity, Big-Five personality factors, attachment style, locus of control, self-esteem, physical symptoms, perceived stress, subjective wellbeing, and all domains of psychological wellbeing are predictive of the quality of EL experiences. All analyses were performed in SPSS 27.0.

3. Results

Of the 137 participants who responded, 8 were excluded for not self-identifying as having a disability and/or for not participating in an EL program. An additional 22 participants were excluded because they did not complete one or more measures, resulting in a final sample size of 107 participants. 54 (50.5%) of these were recruited through social media. There were 48 males (44.9%), 56 females (52.3%), and 3 participants who identified as non-binary (2.8%). The average age was 29.8 years (SD = 11.2). The average year of study was 3.17 years (SD = 1.39). There was no association between participants’ age and year of study. 76 participants (71.0%) identified as local students, and 31 as studying elsewhere (29.0%). Most participants (83.2%, N = 89) were from an average or above average socioeconomic background, while 18 participants (16.8%) were from a low socioeconomic background. Both the primary type of disability as well as the age of acquisition were broadly distributed.

Table 1.

Frequencies and Percentages of Participants’ Primary Type of Disability.

Table 1.

Frequencies and Percentages of Participants’ Primary Type of Disability.

| Type of disability |

n |

% |

| Physical/orthopedic |

15 |

14.0 |

| Deaf/hard of hearing or hearing impaired |

14 |

13.1 |

| Blind or visually impaired |

11 |

10.3 |

| Cognitive disability (including TBI) |

7 |

6.5 |

| Autism |

8 |

7.5 |

| Chronic health condition |

8 |

7.5 |

| Learning disability |

8 |

7.5 |

| ADHD |

11 |

10.3 |

| Psychiatric disability |

21 |

19.6 |

| Other |

4 |

3.7 |

| Totals (N = 107) |

107 |

100.0 |

Table 2.

Frequencies and Percentages of Participants’ Age of Acquiring Disability.

Table 2.

Frequencies and Percentages of Participants’ Age of Acquiring Disability.

| Age of acquiring disability |

n |

% |

| Congenital or at birth |

16 |

15.0 |

| As a child (up to age 12) |

33 |

30.8 |

| As an adolescent (age 12-18) |

36 |

33.6 |

| As an adult |

22 |

20.6 |

| Totals (N = 107) |

107 |

100.0 |

More than half (57.5%) the participants indicated that their disability had an influence on their choice of specialty or area of study. 61 participants (57.5%) indicated a visible disability, and 45 participants indicated an invisible disability (42.5%). 66 participants (62.3%) indicated that they had requested or received only formal accommodations (i.e., accommodations made through a disability services office or other official channels, including extended times for tests, alternate format books, readers, or sign language interpreters), 27 participants (25.5%) indicated that they had requested or received only informal accommodations (i.e., accommodations made through an informal agreement with a faculty member or supervisor), 6 participants (5.7%) indicated that they had requested or received both formal and informal accommodations, and 7 participants (6.6%) indicated that they had neither requested nor received any accommodation. Reasons given for not requesting or receiving accommodation included not having a diagnosis, difficulties working with the accessibility office, reluctance to disclose their disability, and not wanting to be judged by others as being lazy due to the invisibility of their disability. The average severity of disability score was 89.63 on a scale that ranges from 1 to 180 (SD = 22.35), with a higher score indicating a higher severity disability.

Participants identified several obstacles for participation before and during the EL program including inappropriate accommodations, anxiety before and during a trip (for international programs), colleagues not knowing about their disability, and difficulty navigating workplace accommodation processes. 33 of 107 (30.8%) participants indicated that they had encountered disability-related barriers during their EL experience which were either structural, attitudinal, or systemic. One participant specified that their concerns with their disability were brushed off and not taken seriously, while another participant had encountered attitudinal barriers from their instructor. Of the participants who indicated that they had disclosed their disability, 37 (34.6%) had disclosed their disability to a university disability service office, 39 (36.4%) to program faculty, 40 (37.4%) to practicum supervisors, and 27 (25.2%) to other students/non-supervisor colleagues. 28 (26.2%) stated that they had disclosed their disability during the application process.

Resources that participants found to be helpful during their EL experience included social networks (e.g., family and friends), staff working for international programs (e.g., instructors and other team members), mental health professionals (e.g., psychiatrists and psychotherapists), community groups for students with disabilities, assistive technology (e.g., noise cancelling headphones and audio recording devices), and online learning resources. Some disability-related resources that participants wished they had access to included a quiet room to write tests, the Speechify App, a hotline for mental health-related situations in the country in which they completed their EL, more university guidance regarding what resources are available for specific disability types, and better access to accommodations. Some advice that participants wanted to give the current EL students in the same program with a similar disability included speaking to advisors about studying strategies, having a strict daily schedule to follow, asking about accommodations in advance, discussing concerns before travelling to ease anxiety, making friends with people who are understanding of the student’s disability and personal struggles, staying connected with existing social networks, building a support plan with a mental health team, and being confident.

Table 3 and

Table 4 illustrate the frequencies and percentages of participants regarding the type of EL they participated in and the setting in which their EL experience was carried out.

Table 5 illustrates the average scores for each of the survey items that address the quality of the EL experience.

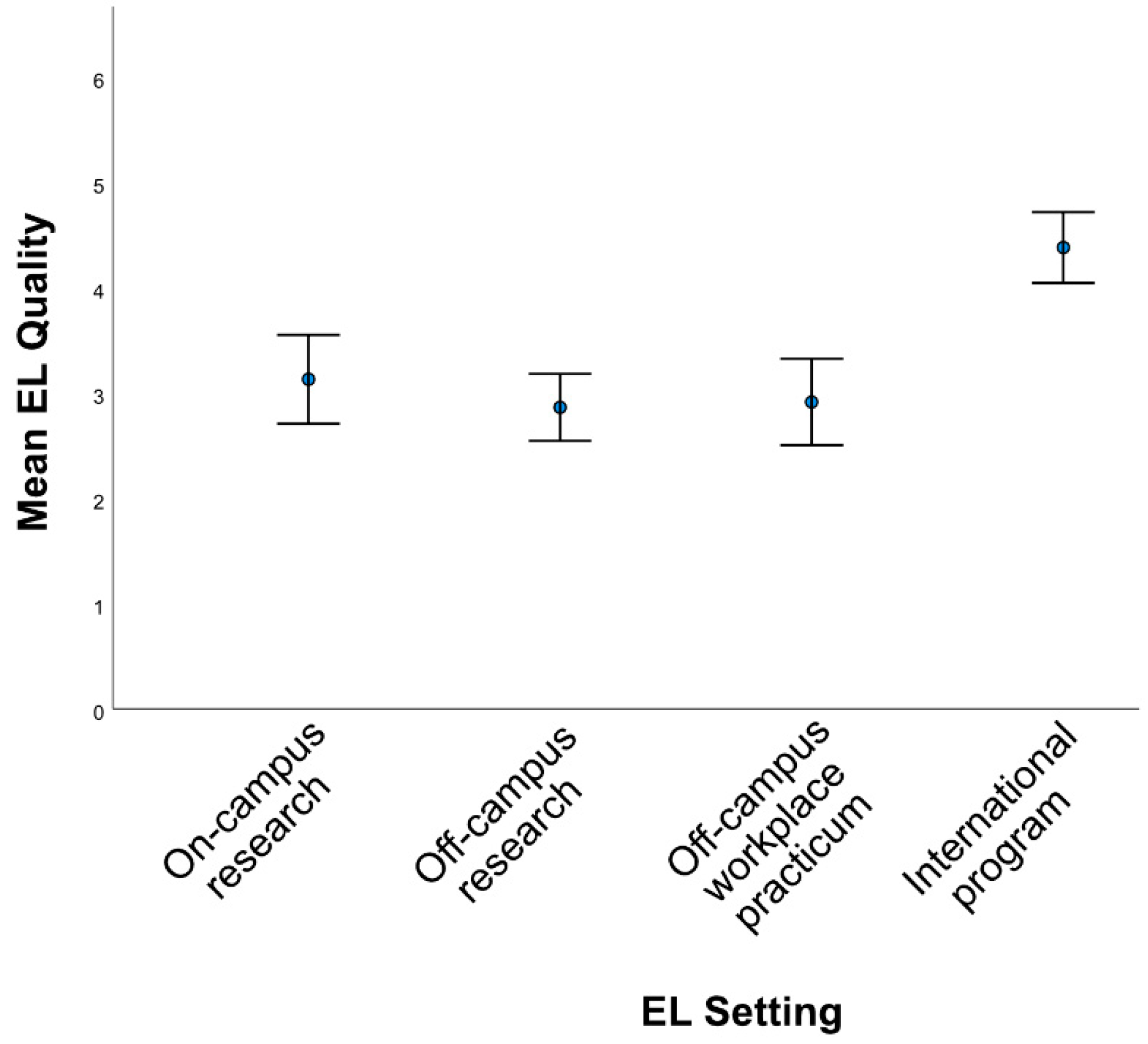

Between-subject ANOVAs comparing mean differences in the quality of EL experiences found no significant differences between genders, disability types, or EL types. However, significant differences in EL quality were found between the different types of EL settings [

F (4, 101) = 8.893,

p = .000] (see

Figure 1).

Post hoc comparisons using the least significant difference test indicated that the mean score for international programs was significantly higher than that for on-campus research (p < .001), off-campus research (p < .001), and off-campus workplace practica (p < .001).

A multiple linear regression was performed to evaluate whether age, year of study, average SES, disability type, disability severity, Big-Five personality factors, attachment style, locus of control, self-esteem, physical symptoms, perceived stress, subjective wellbeing, and all subscales of psychological wellbeing are predictive of the quality of EL experiences. The model explained 72.1% of the variance in EL quality [F(26,58) = 5.756,

p < .001]. Five variables (year of study, Big-Five Neuroticism, Big-Five Openness, subjective wellbeing, and the environmental mastery domain of psychological wellbeing) significantly predicted the quality of EL experiences. Scores for all dispositional and adjustment and wellbeing variables show reasonable variance.

Table 6.

Multiple Regression Analysis for Variables Predicting EL Quality.

Table 6.

Multiple Regression Analysis for Variables Predicting EL Quality.

| Predictor |

Unstandardized Coefficients |

Standardized Coefficients |

|

95% CI for β |

| |

β |

SE |

Beta |

t |

sig. |

Lower |

Upper |

| Subjective wellbeing |

.090 |

.022 |

.485 |

4.150 |

<.001*** |

0.46 |

.133 |

| Year of study |

.297 |

.072 |

.385 |

4.153 |

<.001*** |

.154 |

.441 |

| Big-Five Neuroticism |

.507 |

.188 |

.281 |

2.700 |

.009** |

.131 |

.883 |

| Big-Five Openness |

.761 |

.209 |

.375 |

3.640 |

<.001*** |

.343 |

1.180 |

| Psychological wellbeing – environmental mastery |

-.074 |

.037 |

-.253 |

-2.007 |

.049* |

-.147 |

.000 |

4. Discussion

The objective of this study was to determine which factors are predictive of the quality of EL experiences among students with disabilities, and whether their EL experiences differ depending on the type of disability, the type of EL, and the setting in which the EL is carried out. Our results indicate that dispositional factors and adjustment and wellbeing variables are significant predictors of the quality of EL experiences, whereas demographic factors such as gender or type and severity of disability are not. These results are consistent with existing literature examining the role of Big-Five personality domains in educational experiences, including associations with university students’ academic achievement (Komarraju et al., 2009) as well as the outcome expectations of students with LD regarding the selection of a major (Brown & Cinamon, 2016). Brown and Cinamon (2016) found that lower levels of openness were associated with higher outcome expectations from a chosen major among students with LD. This relationship between lower openness and higher outcome expectations may also apply to EL experiences, in which case individuals with lower openness may be more likely to have higher expectations of their EL experiences and thus more likely to be disappointed if those experiences do not match their high expectations. Our results reveal strong positive associations between both Big-Five Neuroticism and Big-Five Openness and the quality of EL experiences, indicating that students who score higher on the Neuroticism subscale and who are more open to new experiences are likely to be more satisfied with their EL experiences than students lower in either domain, a pattern which corresponds with the previously noted relationships between Neuroticism, Openness, and educational outcomes.

According to Tansey et al. (2018), students with disabilities are less likely to graduate from university compared to their peers without disabilities, and these lower graduation rates may be attributed to their lower quality of life and wellbeing. Our results underscore the possible impact of quality of life and wellbeing on the overall academic experiences of students with disabilities, with a strongly significant relationship between subjective wellbeing and the quality of EL experiences.

The absence of a significant relationship between EL quality and physical symptoms is intriguing, as previous work suggested that experiences of students with disabilities within higher education can be negatively affected by the stressors caused by physical demands (Hong, 2015). However, while the quantitative data do not support an effect of physical symptoms on EL quality, the qualitative data does: Students with ADHD and other LD frequently reported a need for access to a quiet room to write tests, reflecting that physical demands and stressors could still be important in the overall experiences of students with disabilities.

Our results also demonstrate that the environmental mastery dimension of psychological wellbeing is predictive of the quality of students with disabilities’ EL experiences, although to a lesser degree than the other significant predictors. Environmental mastery reflects the degree to which an individual feels competent in managing their environment, controlling an array of external activities, and an ability to create or choose contexts that meet their needs. With respect to EL, instances of environmental mastery might entail individuals entering a work-integrated learning setting and exhibiting ease in requesting directions or demonstrating confidence in seeking guidance. Given the previously described needs for environmental accommodations (e.g., quiet rooms for tests, assistive technologies, etc.), it is likely that the extent to which students feel a sense of environmental mastery in their EL experiences is at least partly determined by their ability to access appropriate accommodations. This underscores the importance of not only increasing the availability of and reducing barriers to access accommodations, but also of increasing the knowledge of instructors and supervisors regarding the various and complex needs of students with disabilities. This is precisely what Felten (2013) intended in developing his principles of SoTL and is exactly what is emphasized by Lawrie et al. (2017), who argue for collaboration between all stakeholders involved in EL programming at any given institution. In effect, each of these contributions to incorporate an inclusive approach to higher education addresses a desire to ensure that students are actual partners in the learning process and faculty must not only consider the needs of the student but must explicitly engage with students in developing the associated curriculum. In other words, recognizing that students with non-physical disabilities do not always feel comfortable disclosing their disability places greater responsibility on the instructor to build a course structure that anticipates potential obstacles for those students. Instructors and supervisors are often the main authority figures with whom students interact during the course of any academic experience and play a key role in the implementation of accommodations for students with disabilities; the more knowledgeable the instructors and supervisors are about the nature of a student’s disability, the better able they will be to ensure that the student achieves the accommodations they require, and the greater sense of environmental mastery the student will feel.

The experiences of students with disabilities have been shown to differ according to the setting in which the EL is carried out (Cunnah, 2015). Our work supports this finding, and in particular reveals that the quality of EL experiences tends to be higher in international settings. This is consistent with work by Heiman and Olenik-Shemesh (2012) showing that factors such as delivery mode at an EL setting may be predictive of students with disabilities’ wellbeing and satisfaction with their EL experience. These results are also consistent with the notion that students with disabilities are more likely to experience positive identities and feel more included at a university setting compared to a work placement (Cunnah, 2015). Since international programs are typically run by university staff, students’ experiences in such programs are likely more consistent with their experiences within a university setting. Conversely, staff in workplace settings likely do not focus on education to the same extent as university staff and as such, experiences often may be less positive.

Consistent with previous findings that the invisibility of a student’s disability may impede their access to the necessary accommodations (Cunnah, 2015; Kiesel et al., 2018; Versnel et al., 2008), the present study provides qualitative evidence that students who have an invisible disability often fear that their accessibility concerns may be disregarded. They are also concerned with being judged as lazy when they do ask for help. These anecdotal reports are consistent with previous literature showing that students with invisible disabilities are reluctant to disclose their disability due to concerns about a lack of understanding from other students and instructors (Mullins & Preyde, 2013). These reports are not representative of the EL experiences of all students with invisible disabilities, but nevertheless reveal a concerning pattern in the educational experiences of some. As discussed above, the ability to access accommodations likely has an important influence on students’ feelings of environmental mastery; if students are precluded from accessing accommodations by social stigmatization and prejudice, their psychological wellbeing is likely negatively affected.

4.1. Limitations of the Present Study

The sample included Canadian and American students from a broad range of colleges and universities, with participants engaging in various types of EL experiences; therefore, this sample is likely sufficiently representative of the EL experiences of students with disabilities more broadly. However, disability type and severity were based on subjective self-reports and the number of participants in each disability category was relatively small. As a result, comparisons between disability types lacked statistical power. Further data collection could provide deeper exploration of the impact of disability type on EL experiences. We also did not compare the quality of EL experiences between participants with and without disabilities. It is likely that the quality of EL experiences differs depending on whether students have a disability, which may also determine whether the predictors of EL quality differ between students with and without disabilities.

4.2. Implications for Educators

Several practical implications can be drawn from our results. First, the satisfaction of students with disabilities with their EL experiences may be improved by increasing their social capital through support networks. This is consistent with advice some participants made to fellow EL students with similar disabilities, which included making friends with people who are sympathetic towards disability issues and staying connected with their existing social networks. Second, the lower satisfaction of students with disabilities with off-campus research or workplace settings merits greater scrutiny from individuals who supervise EL students at the workplace, to ensure that the needs of students with disabilities are being properly met in off-campus settings. Third, providing a greater degree of training regarding the nature of disabilities, both visible and invisible, and the complex needs that accompany them, to instructors and supervisors involved in administering EL experiences may result in more inclusive EL course design and more suitable accommodations, which is in agreement with UDL practices (Burgstahler et al., 2010; Cumming & Rose, 2022). This is particularly relevant when examining the SoTL principles, which encourage student participation in the development of the relevant curriculum (deBraga et al., 2015; Felten, 2013; Hounsell et al. 2005). One study (Abualrub et al., 2013) specifically advocates for incentivizing learning by ensuring that the student perspective is accounted for. From an EL perspective, and specifically one where students with disabilities are concerned, this incentivization is synonymous with student success. In other words, given the role of the Big-Five personality traits considered in this study, ensuring an excellent partnership with the student has never been more important.

5. Conclusions

As universities continue to prioritize inclusivity in their policies, the practical application of inclusivity measures often falls short (Rankin et al., 2022). The tenets of SoTL advocate for the deliberate inclusion of students within the decision-making processes pertaining to course design, as emphasized by Felten (2013). In addition, the UDL literature also highlights the importance of establishing an environment that supports all students (Burgstahler et al., 2010; Cumming & Rose, 2022; Edwards et al., 2022). Our findings underscore that demographic factors, such as gender or the type and severity of disability, do not significantly predict the quality of EL experiences among university students with disabilities. Instead, it is dispositional factors and overall adjustment and well-being variables, such as subjective well-being and the environmental mastery dimension of psychological well-being, that emerge as significant predictors of EL quality. These results highlight the imperative of tailoring EL courses to address the unique needs and challenges faced by students with disabilities by fostering positive dispositional characteristics through accommodations and support that help develop the resilience students need to succeed. This entails educating post-secondary instructors and supervisors about the diverse and intricate needs of this student group, ensuring they possess the knowledge and resources to establish inclusive learning environments. Moreover, the results accentuate the significance of social networks and support systems in enhancing the satisfaction and well-being of students with disabilities in EL experiences.

In addition, our study reveals that the setting in which EL is conducted can influence the quality of the experience. Notably, international programs are associated with higher satisfaction levels compared to on-campus research, off-campus research, and off-campus workplace practica. This suggests that the support and accommodations offered in international programs may be more inclusive and conducive to positive experiences for students with disabilities.

Overall, our study advances our comprehension of the factors shaping the quality of EL experiences for students with disabilities. By identifying predictors of EL quality, post-secondary institutions can actively work towards fostering more inclusive and supportive environments. Such environments are indispensable for enabling students with disabilities to engage in successful and gratifying EL experiences. Through the implementation of structured programs that facilitate the development of resilience by nurturing friendships and personal growth, institutions can better equip these students to navigate the challenges presented by both their disability and academia.

Conflicts of Interest

The Authors report no conflicts of interest.

References

- Abualrub, I., Karseth, B., & Stensaker, B. (2013). The various understandings of learning environment in higher education and its quality implications. Quality in Higher Education, 19(1), 90-110. [CrossRef]

- Adams, K. S., & Proctor, B. E. (2010). Adaptation to college for students with and without disabilities: Group differences and predictors. Journal of Postsecondary Education and Disability, 22(3), 166-184.

- Antaramian, S. (2015). Assessing psychological symptoms and well-being: Application of a dual-factor mental health model to understand college student performance. Journal of Psychoeducational Assessment, 33(5), 419-429. [CrossRef]

- Austin, M. J., & Rust, D. Z. (2015). Developing an Experiential Learning Program: Milestones and Challenges. International Journal of Teaching and Learning in Higher Education, 27(1): 143-153.

- Ardell, S., Beug, P., & Hrudka, K. (2016). Perceived stress levels and support of student disability services. University of Saskatchewan Undergraduate Research Journal, 2(2), 1-10. [CrossRef]

- Bergsteiner, H., Avery, G. C., & Neumann, R. (2010). Kolb's experiential learning model: Critique from a modelling perspective. Studies in Continuing Education, 32(1), 29-46. [CrossRef]

- Bradley, J., & Miller, A. (2010). Widening participation in higher education: Constructions of “going to university”. Educational Psychology in Practice, 26(4), 401-413. [CrossRef]

- Brigham, F. J., Scruggs, T. E., & Mastropieri, M. A. (2011). Science education and students with learning disabilities. Learning Disabilities Research & Practice, 26(4), 223-232. [CrossRef]

- Brown, D., & Cinamon, R. G. (2016). Personality traits’ effects on self-efficacy and outcome expectations for high school major choice. International Journal for Educational and Vocational Guidance, 16(3), 343-361. [CrossRef]

- Brown, K., de Bie, A., Aggarwal, A., Joslin, R., Williams-Habibi, S., & Sivanesanathan, V. (2020). Students with disabilities as partners: A case study on user testing an accessibility website. International Journal for Students as Partners, 4(2), 97–109. [CrossRef]

- Bruce, C., & Aylward, M. L. (2021). Accommodating disability at university. Disability Studies Quarterly, 41(2).

- Burgstahler, S. (2001). A collaborative model to promote career success for students with disabilities. Journal of Vocational Rehabilitation, 16(3-4), 209-215.

- Burgstahler, S. E., & Cory, R. C. (Eds.). (2010). Universal design in higher education: From principles to practice. Harvard Education Press.

- Cohen, S., & Hoberman, H. M. (1983). Positive events and social supports as buffers of life change stress. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 13(2), 99-125. [CrossRef]

- Cohen, S., Kamarck, T., & Mermelstein, R. (1983). A global measure of perceived stress. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 24(4), 385–396. [CrossRef]

- Collins, N. L. (1996). Working models of attachment: Implications for explanation, emotion, and behavior. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 71(4), 810-832. [CrossRef]

- Cumming, T. M. & Rose, M. C. (2022). Exploring universal design for learning as an accessibility tool in higher education: A review of the current literature. The Australian Educational Researcher 49, 1025-1043. [CrossRef]

- Cummings, S. M. (2002). Predictors of psychological well-being among assisted-living residents. Health & Social Work, 27(4), 293-302. [CrossRef]

- Cunnah, W. (2015). Disabled students: Identity, inclusion and work-based placements. Disability & Society, 30(2), 213-226. [CrossRef]

- deBraga, M., Boyd, C., & Abdulnour, S. (2015). Using the principles of SoTL to redesign an advanced evolutionary biology course. Teaching and Learning Inquiry, 3(1), 15-29. [CrossRef]

- Dewey, J. (1933). How We Think: A Restatement of the Relation of Reflective Thinking to the Educative Process. 301pgs. Boston, MA: D.C. Heath & Co Publishers.

- Diener, E. D., Emmons, R. A., Larsen, R. J., & Griffin, S. (1985). The satisfaction with life scale. Journal of Personality Assessment, 49(1), 71-75. [CrossRef]

- Dyer, B., & Schumann, D. W., (1993). Partnering Knowledge and Experience: The Business Classroom as Laboratory. Marketing Education Review 3: 32-39. [CrossRef]

- Edwards, M., Poed, S., Al-Nawab, H., & Penna, O. (2022). Academic accommodations for university students living with disability and the potential of universal design to address their needs. Higher Education, 84, 779-799. [CrossRef]

- Estrada, L., Dupoux, E., & Wolman, C. (2006). The relationship between locus of control and personal-emotional adjustment and social adjustment to college life in students with and without learning disabilities. College Student Journal, 40(1), 43-55.

- Felten, P. (2013). Principles of good practice in SoTL. Teaching and Learning Inquiry, 1(1), 121-125. [CrossRef]

- Grant, S., Langan-Fox, J., & Anglim, J. (2009). The Big Five traits as predictors of subjective and psychological well-being. Psychological Reports, 105(1), 205-231. [CrossRef]

- Griffin, D. K., Rosenberg, H., Cheyney, W., & Greenberg, B. (1996). A comparison of self-esteem and job satisfaction of adults with mild mental retardation in sheltered workshops and supported employment. Education and Training in Mental Retardation and Developmental Disabilities, 31(2), 142–150.

- Heiman, T., & Olenik-Shemesh, D. (2012). Students with LD in higher education: Use and contribution of assistive technology and website courses and their correlation to students’ hope and well-being. Journal of Learning Disabilities, 45(4), 308-318. [CrossRef]

- Hollingshead, A. B. (1975). Four factor index of social status [Unpublished manuscript]. Department of Sociology, Yale University.

- Hong, B. S. S. (2015). Qualitative analysis of the barriers college students with disabilities experience in higher education. Journal of College Student Development, 56(3), 209-226. [CrossRef]

- Hounsell, D., McCune, V., Litjens, J., & Hounsell, J. (2005). Subject Overview Report: Biosciences. Universities of Edinburgh. http://www.etl.tla.ed.ac.uk//docs/BiosciencesSR.pdf.

- Hughes, R. B., Taylor, H. B., Robinson-Whelen, S., & Nosek, M. A. (2005). Stress and women with physical disabilities: Identifying correlates. Women's Health Issues, 15(1), 14-20. [CrossRef]

- Hwang, K., Johnston, M. V., & Smith, J. K. (2009). Adult attachment styles and life satisfaction in individuals with physical disabilities. Applied Research in Quality of Life, 4(3), 295-310. [CrossRef]

- Jarvis, P. (2012). Adult Learning in the Social Context (1st ed.). Routledge. [CrossRef]

- John, O. P., & Srivastava, S. (1999). The Big-Five trait taxonomy: History, measurement, and theoretical perspectives. Handbook of Personality: Theory and Research, 2, 102-138.

- Keeton, M. T., & Tate, P. J. (1978). Learning by Experience: What, Why, How? 109pgs. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

- Kiesel, L. R., DeZelar, S., & Lightfoot, E. (2018). Challenges, barriers, and opportunities: Social workers with disabilities and experiences in field education. Journal of Social Work Education, 54(4), 696-708. [CrossRef]

- Koca-Atabey, M., Karanci, A. N., Dirik, G., & Aydemir, D. (2011). Psychological wellbeing of Turkish university students with physical impairments: An evaluation within the stress-vulnerability paradigm. International Journal of Psychology, 46(2), 106-118. [CrossRef]

- Kolb, A. Y., Kolb, D. A. (2006). Learning Styles and Learning Spaces: A Review of the Multidisciplinary Application of Experiential Learning in Higher Education. In Learning Styles and Learning: A Key to Meeting the Accountability Demands in Education, edited by Ronald R. Sims and Serbrenia J. Sims, 45-91. New York: Nova Publishers.

- Kolb, A. Y., & Kolb, D. A. (2017). Experiential Learning Theory as a Guide for Experiential Educators in Higher Education, A Journal for Engaged Educators, 1(1), 7-44. [CrossRef]

- Komarraju, M., Karau, S. J., & Schmeck, R. R. (2009). Role of the Big Five personality traits in predicting college students' academic motivation and achievement. Learning and Individual Differences, 19(1), 47-52. [CrossRef]

- Kowalski, R. M., Morgan, C. A., Drake-Lavelle, K., & Allison, B. (2016). Cyberbullying among college students with disabilities. Computers in Human Behavior, 57, 416-427. [CrossRef]

- Lawrie, G., Marquis, E., Fuller, E., Newman, T., Qiu, M., Nomikoudis, M., Roelofs, F., & van Dam, L. (2017). Moving towards inclusive learning and teaching: A synthesis of recent literature. Teaching & Learning Inquiry, 5(1), 9-21. [CrossRef]

- Lefcourt, H. M., von Baeyer, C. L., Ware, E. E., & Cox, D. J. (1979). The multidimensional-multi-attributional causality scale: The development of a goal specific locus of control scale. Canadian Journal of Behavioural Science, 11(4), 286-304. [CrossRef]

- Lengnick-Hall, C. A., & Sanders, M. M. (1997). Designing Effective Learning Systems for Management Education: Student Roles, Requisite Variety, and Practicing What We Preach. Academy of Management Journal, 40(6): 1334-1368. [CrossRef]

- Lewin, K. (1951). Field Theory of Social Science: Selected Theoretical Papers. (Edited by Dorwin Cartwright.) 346pgs. New York: Harper & Row.

- Lund, E. M., Andrews, E. E., & Holt, J. M. (2014). How we treat our own: The experiences and characteristics of psychology trainees with disabilities. Rehabilitation Psychology, 59(4), 367–375. [CrossRef]

- March, J. (2010). The Ambiguities of Experience. 168 pgs. Ithaca: Cornell University Press.

- Morris, T. H. (2020). Experiential learning–a systematic review and revision of Kolb’s model. Interactive Learning Environments, 28(8), 1064-1077. [CrossRef]

- Mullins, L., & Preyde, M. (2013). The lived experience of students with an invisible disability at a Canadian university. Disability & Society, 28(2), 147-160. [CrossRef]

- Nigg, J., Blaskey, L., Huang-Pollock, C., & John, O. (2002). ADHD symptoms and personality traits: Is ADHD an extreme personality trait? The ADHD Report, 10(5), 6-11. [CrossRef]

- Rankin, J. C., Pearl, A. J., de St Jorre, T. J., McGrath, M. M., Dyer, S., Sheriff, S., Armitage, R., Ruediger, K., Jere, A., Zafar, S., Sedres, S., & Chaudhary, D. (2022). Delving into institutional diversity messaging: A cross-institutional analysis of student and faculty interpretations of undergraduate experiences of equity, diversity, and inclusion in university websites. Teaching & Learning Inquiry, 10. [CrossRef]

- Rosenberg, M. (1965). Society and the adolescent self-image. Princeton University Press.

- Rotter, J. B. (1966). Generalized expectancies for internal versus external control of reinforcement. Psychological Monographs, 80 (Whole No. 609).

- Ryff, C. D. (1989). Happiness is everything, or is it? Explorations on the meaning of psychological well-being. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 57(6), 1069. [CrossRef]

- Saltes, N. (2020). Disability barriers in academia: An analysis of disability accommodation policies for faculty at Canadian universities. Canadian Journal of Disability Studies, 9(1), 53-90. [CrossRef]

- Shakespeare, T. (2006). The social model of disability. The Disability Studies Reader, 2(3), 197-204.

- Smedema, S. M. (2014). Core self-evaluations and well-being in persons with disabilities. Rehabilitation Psychology, 59(4), 407-414. [CrossRef]

- Smedema, S. M., Lee, D., & Bhattarai, M. (2022). An examination of the relationship of core self-evaluations and life satisfaction in college students with disabilities. Rehabilitation Counseling Bulletin, 65(2), 129-139. [CrossRef]

- Tansey, T. N., Smedema, S., Umucu, E., Iwanaga, K., Wu, J. R., Cardoso, E. D. S., & Strauser, D. (2018). Assessing college life adjustment of students with disabilities: Application of the PERMA framework. Rehabilitation Counseling Bulletin, 61(3), 131-142. [CrossRef]

- Trigwell, K. (2013). Evidence of the impact of scholarship of teaching and learning purposes. Teaching & Learning Inquiry, 1(1), 95-105. [CrossRef]

- Üstün, T. B., Kostanjsek, N., Chatterji, S., & Rehm, J. (Eds.). (2010). Measuring health and disability: Manual for WHO Disability Assessment Schedule WHODAS 2.0. World Health Organization.

- Versnel, J., Hutchinson, N. L., Munby, H., & Chin, P. (2008). Work-based learning for adolescents with learning disabilities: Creating a context for success. Exceptionality Education International, 18(1), 113-134. [CrossRef]

- Wurdinger, S., & Allison, P. (2017). Faculty perceptions and use of experiential learning in higher education. Journal of e-learning and Knowledge Society, 13(1), 15-26.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).