Submitted:

23 July 2024

Posted:

26 July 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1.Introduction

2. Material and Methods

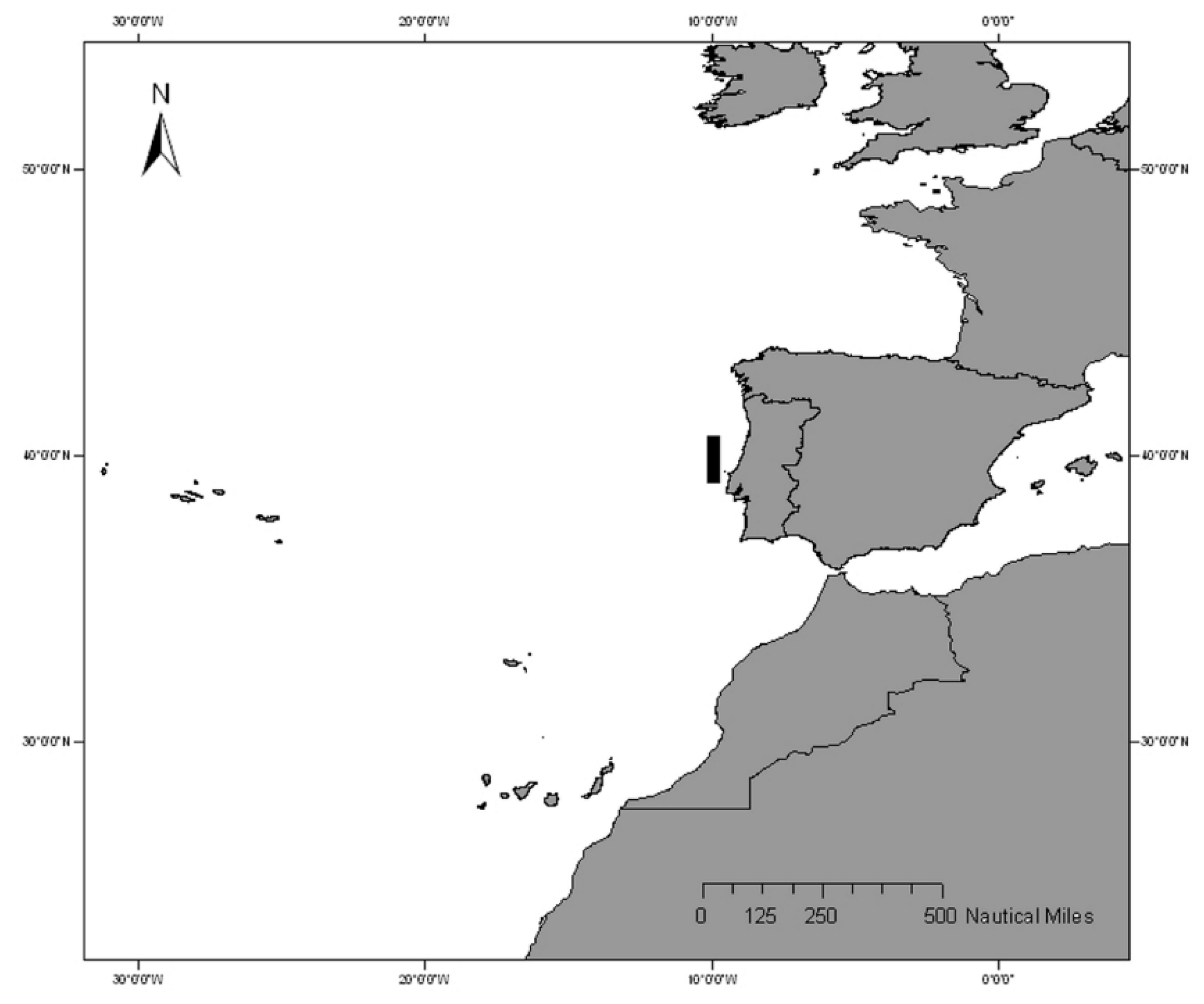

2.1. Sampling

2.2. Age and Growth

2.3. Reproduction

3. Results

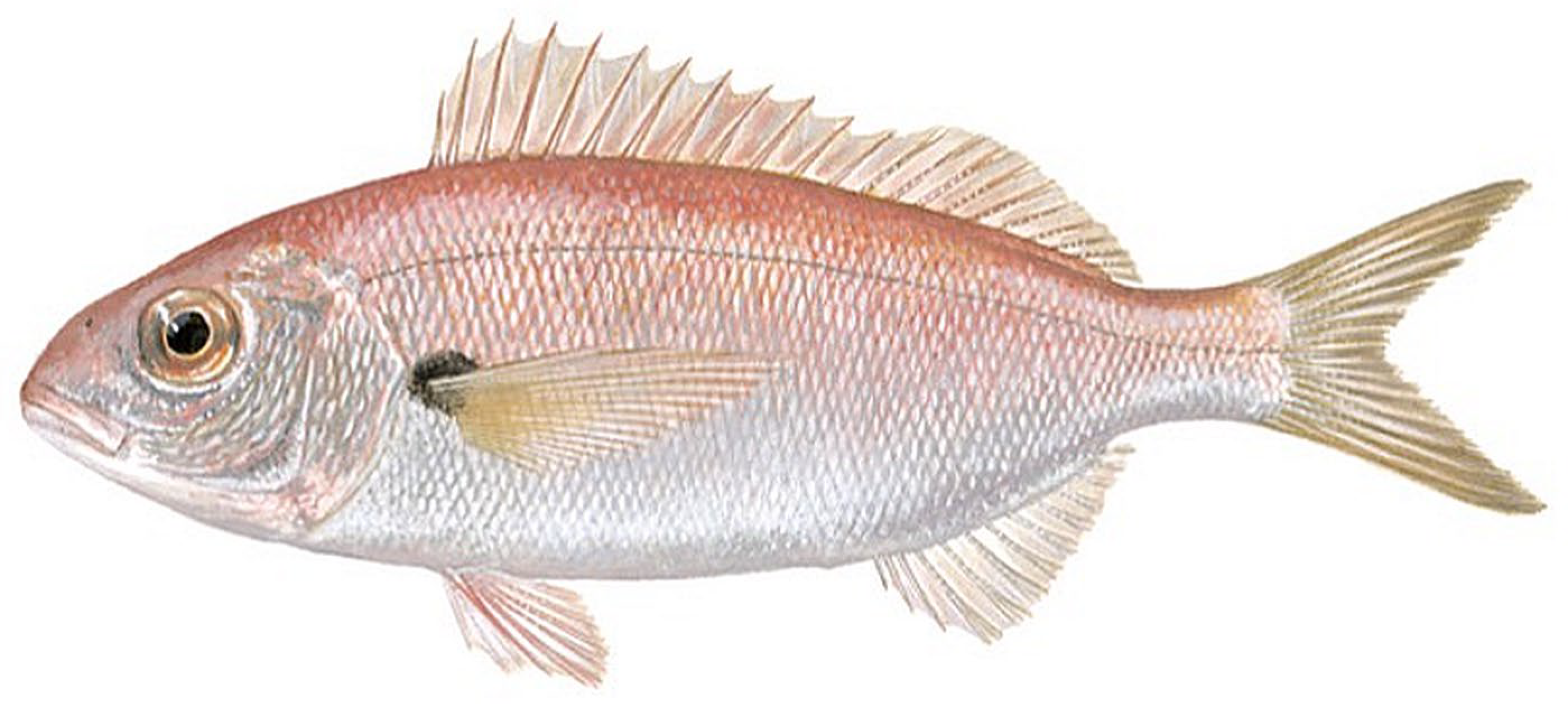

3.1. Age and Growth

3.1.1. Length-Weight Relationship

3.1.2. Ageing Methodology, Precision, and Bias

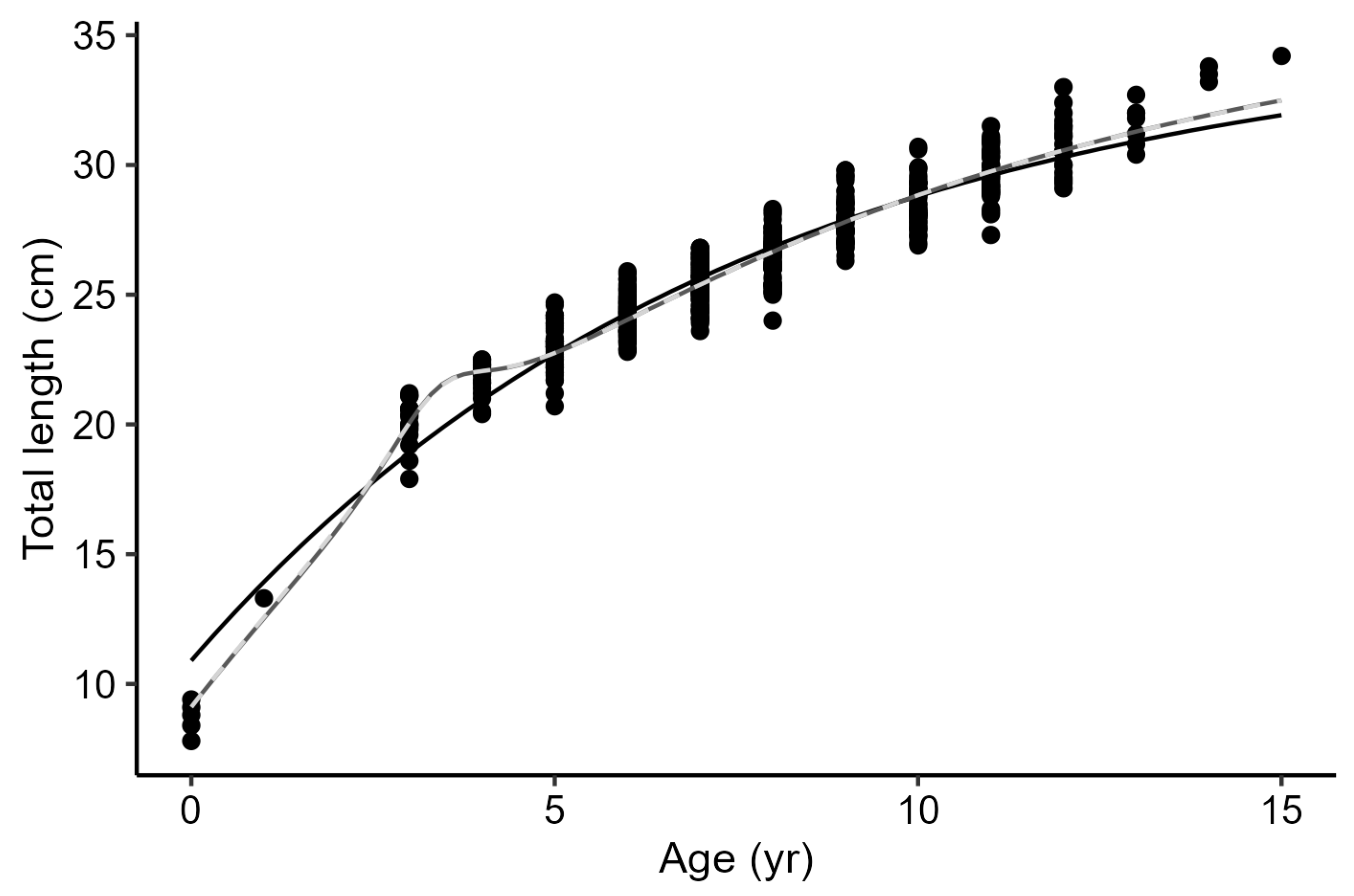

3.1.3. Growth Model

3.2. Reproduction

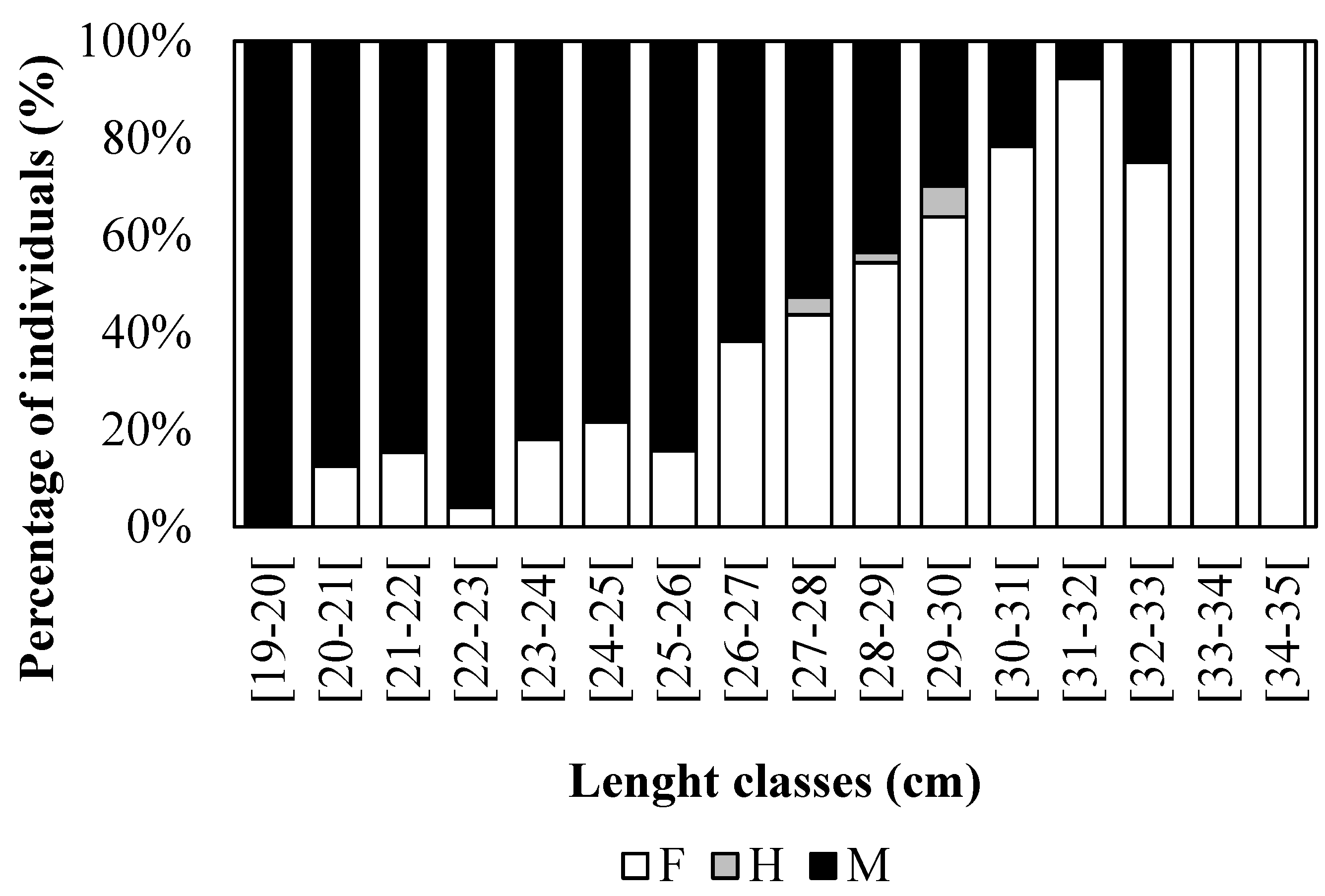

3.2.1. Sample Characterization

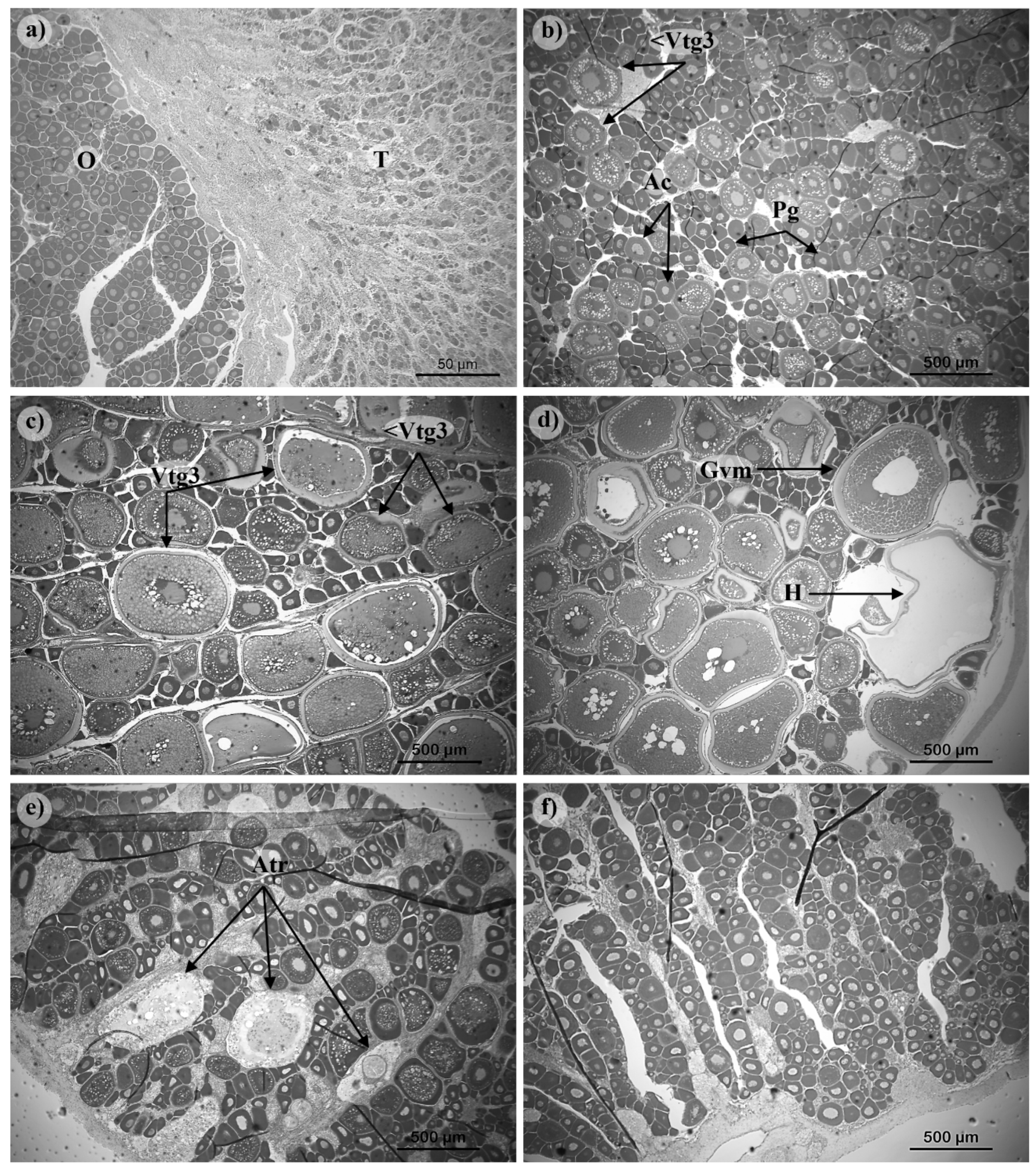

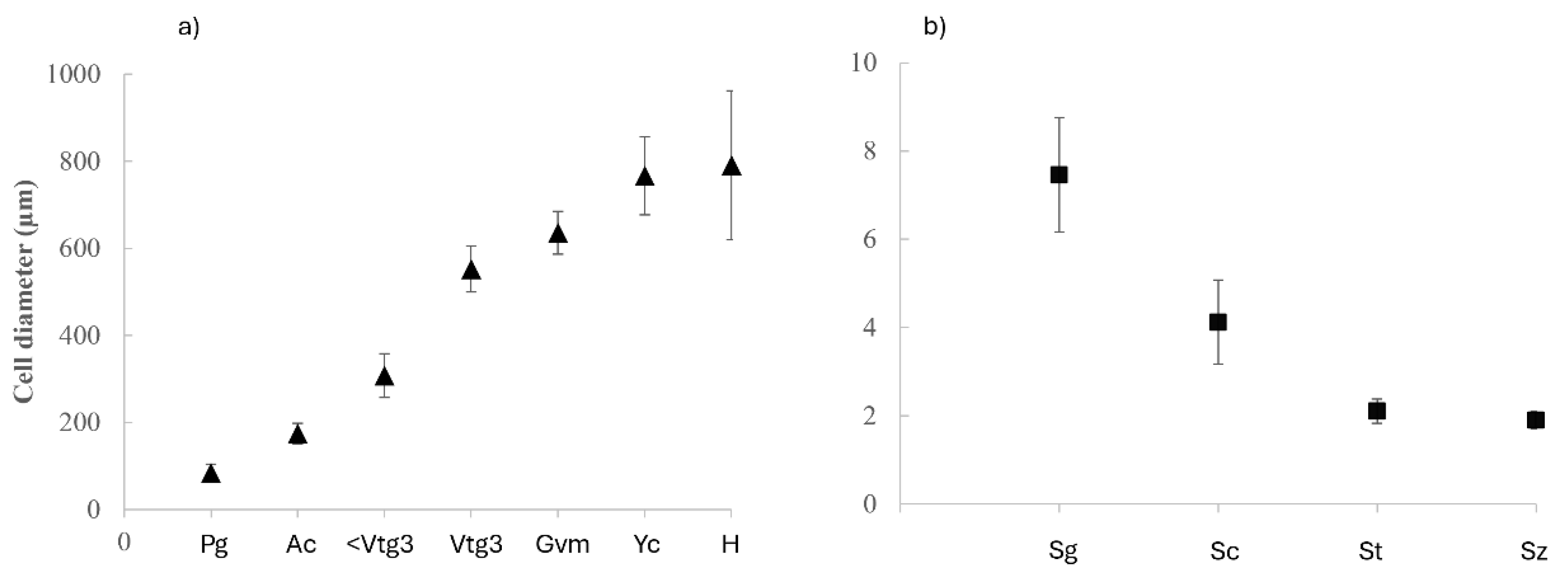

3.2.2. Structure of Ovaries and Testicles

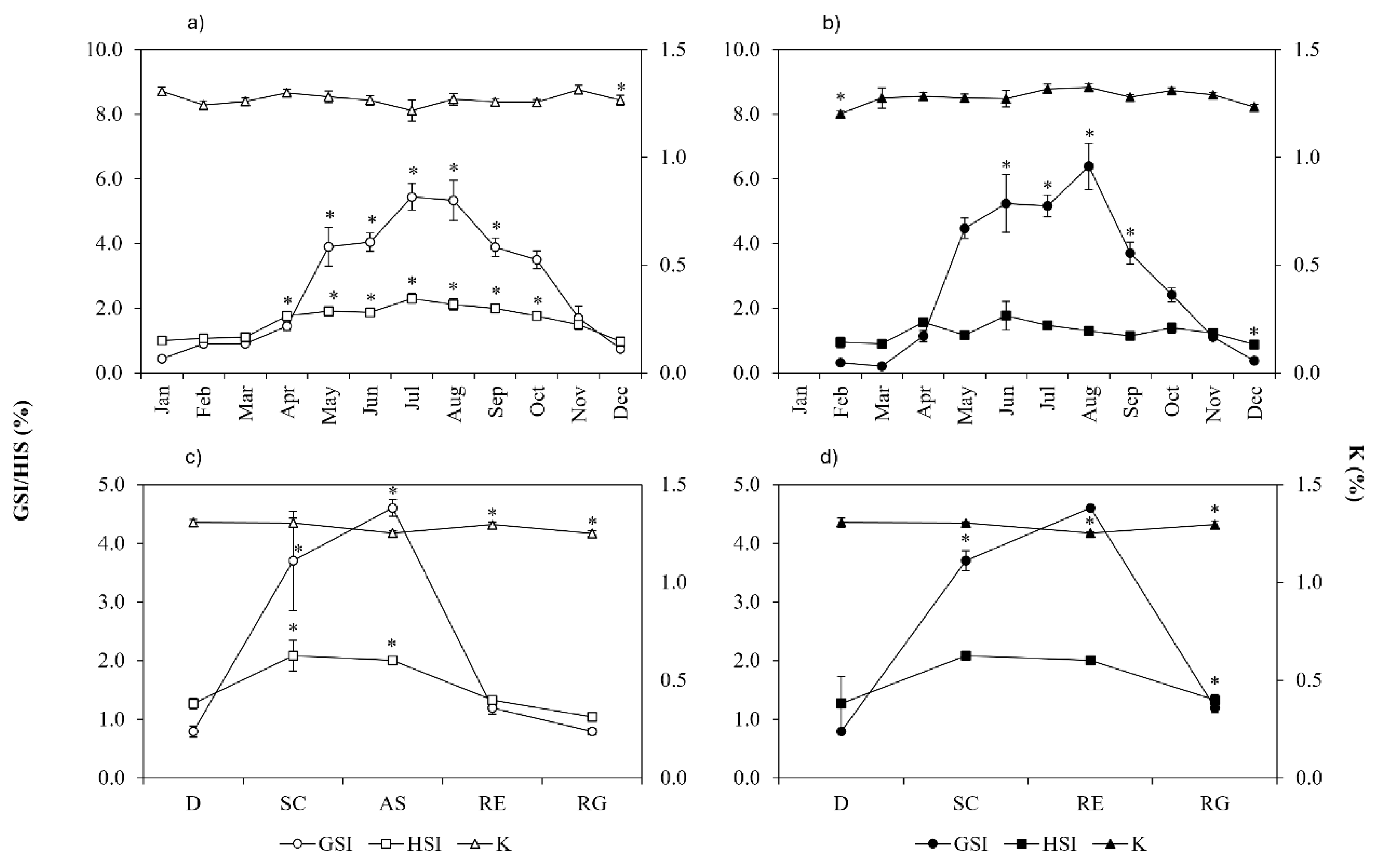

3.2.3. Sexual Cycle

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Russell, B.; Carpenter, K.E.; Pollard, D. Pagellus acarne. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species, 2014, e.T170229A1297432. https://www.iucnredlist.org/species/170229/1297432.

- Di Maio, F.; Geraci, M.; Scannella, D.; Falsone, F.; Colloca, F.; Vitale, S.; Rizzo, P.; Fiorentino, F. Age structure of spawners of the axillary seabream, Pagellus Acarne (Risso, 1827), in the central Mediterranean Sea (strait of Sicily). Reg Stud Mar Sci 2020, 34, 101082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erzini, K.; Bentes, L.; Coelho, R.; Correia, C.; Lino, P.G.; Monteiro, P.; Ribeiro, J.; Gonçalves, J.M.S. Fisheries biology and assessment of demersal species (Sparidae) from the South of Portugal. Commission of the European Communities DG XIV/C/1, Final Report. 2001, Ref. 98/082, 263 pp.

- Santos, M.M.; Monteirom, C.; Erzinim, K. Aspects of the biology and gillnet selectivity of the axillary seabream (Pagellus acarne, Risso) and common pandora (Pagellus erythrinus, Linnaeus) from the Algarve (south Portugal). Fish Res 1995, 23, 223–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- INE (2023). Estatísticas da Pesca 2022. Lisboa, Portugal: INE, Instituto Nacional de Estatística. Available online: https://www.ine.pt/xportal/xmain?xpid=INE&xpgid=ine_publicacoes&PUBLICACOESpub_boui=66322600&PUBLICACOESmodo=2 (accessed on 31 May 2023).

- Velasco, E.M.; Jiménez-Tenorio, N.; Del Árbol, J.; Bruzón, M.A.; Baro, J.; Sobrino, I. Age, growth and reproduction of the axillary seabream, Pagellus acarne, in the Atlantic and Mediterranean waters off southern Spain. JMBA 2011, 91, 1243–1253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bensahla Talet, L.; Gherram, M.; Dalouche, F.; Bensahla Talet, A.; Boutiba, Z. Reproductive biology of Pagellus acarne (Risso, 1927) (Teleostei: Sparidae) off western Algerian waters (Western Mediterranean). CBM 2017, 58, 443–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soykan, O.; İlkyaz, A.; Metin, G.; Kınacıgil, H. Growth and reproduction of Boops boops, Dentex macrophthalmus, Diplodus vulgaris, and Pagellus acarne (Actinopterygii: Perciformes: Sparidae) from east-central Aegean Sea, Turkey. AleP 2015, 45, 39–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ilhan, D. Age, growth, and diet of axillary seabream, Pagellus acarne (Actinopterygii: Perciformes: Sparidae), in the central Aegean Sea. AleP 2018, 48, 329–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bentata-Keddar, I.; Abid-Kachour, S.; Bouderbala, M.; Mouffok, S. Reproduction and growth of Axillary seabream Pagellus acarne (Risso, 1827) (Perciformes Sparidae) from the Western Algerian coasts. Biodivers J 2020, 11, 351–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali-Basha, N.; Hamwi, N.; Saad, A. Age, growth, Mortality and Exploitation of the Axillary seabream, Pagellus acarne (Risso, 1826) (Sparidae) from the Syrian marine waters. Damascus Uni J Agric Sci 2023, 39, 161–172. [Google Scholar]

- Pajuelo, B.J.G.; Lorenzo, J.M. Reproduction, age, growth and mortality of axillary seabream, Pagellus acarne (Sparidae), from the Canarian archipelago. J Appl Ichthyol 2000, 16, 41–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coelho, R.; Bentes, L.; Gonçalves, J.; Correia, C.; Lino, P.; Monteiro, P. Age, growth and reproduction of the axillary seabream, Pagellus acarne (Risso, 1827), from the South coast of Portugal. Thalassas 1999, 21, 77–84. [Google Scholar]

- Abecasis, D.; Bentes, L.; Coelho, R.; Correia, C.; Lino, P.G.; Monteiro, P.; Gonçalves, J.M.S.; Ribeiro, J.; Erzini, K. Ageing seabreams: A comparative study between scales and otoliths. Fish Res 2008, 89, 37–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Figueiredo, T. Montesinho and the Mountains of Northern Portugal. In Natural Heritage from East to West; Evelpidou, N., Figueiredo, T., Mauro, F., Tecim, V., Vassilopoulos, A., Eds.; Springer: Berlin, Heidelberg, 2010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardoso, P.G.; Dolbeth, M.; Sousa, R.; Relvas, P.; Santos, R.; Silva, A.; Quintino, V. Chapter 7 - The Portuguese Coast. In World Seas: an Environmental Evaluation (Second Edition); Sheppard, C., Ed.; Academic Press, p. 2019; pp. 189–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neto, C.S. Circulação de ar na península de Tróia e costa da Galé. Finisterra 2000, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gamito, R.; Vinagre, C.; Teixeira, C.M.; Costa, M.J.; Cabral, H.N. Are Portuguese Coastal Fisheries Affected by River Drainage? Aquat. Living Resour. 2016, 29, 102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beamish, R.J.; Fournier, D.A. A method for comparing the precision of a set of age determinations. Can J Fish Aquat Sci 1981, 38, 982–983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, W.Y.B. A statistical method for evaluating the reproducibility of age determination. Can J Fish Aquat Sci 1982, 39, 1208–1210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campana, S.E.; Annand, M.C.; McMillan, J.I. Graphical and statistical methods for determining the consistency of age determinations. Trans Am Fish Soc 1995, 124, 131–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoenig, J.M.; Morgan, M.J.; Brown, C.A. Analysing differences between two age determination methods by tests of symmetry. Can J Fish Aquat Sci 1995, 52, 364–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogle, D.H.; Doll, J.C.; Wheeler, A.P.; Dinno, A. (2023). _FSA: Simple Fisheries Stock Assessment Methods_. R package version 0.9.4, <https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=FSA>.

- Williams, T.; Bedford, B.C. The use of otoliths for age determination. In The Ageing of Fish; Bagenal, T.B., Ed.; Gresham Press: Old Woking, England, 1974; pp. 114–123. [Google Scholar]

- Soriano, M.; Moreau, J.; Hoenig, J.M.; Pauly, D. New functions for the analysis of two-phase growth of juvenile and adult fishes, with application to Nile Perch. Transactions of the American Fisheries Society 1992, 121, 486–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- R Core Team (2023). R: A language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria. URL https://www.R-project.org/.

- Baty, F.; Ritz, C.; Charles, S.; Brutsche, M.; Flandrois, J.-P.; Delignette-Muller, M.-L. A Toolbox for Nonlinear Regression in R: The Package nlstools. Journal of Statistical Software 2015, 66, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown-Peterson, N.J.; Wyanski, D.M.; Saborido-Rey, F.; Macewicz, B.J.; Lowerre-Barbieri, S.K. A standardized terminology for describing reproductive development in fishes. Marine and Coastal Fisheries: Dynamics, Management, and Ecosystem Science 2011, 3, 52–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadovy, Y.; Shapiro, D.Y. Criteria for the diagnosis of hermaphroditism in fishes. Copeia 1987, 136–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunn, O.J. Multiple comparisons using rank sums. Technometrics 1964, 6, 241–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campana, S.E. Accuracy, precision and quality control in age determination, including a review of the use and abuse of age validation methods. J Fish Biol 2001, 59, 197–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahé, K.; Bellamy, E.; Delpech, J.P.; et al. Evidence of a relationship between weight and total length of marine fish in the North-eastern Atlantic Ocean: physiological, spatial and temporal variations. J Mar Biol Assoc UK 2018, 98, 617–625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biolé, F.G.; Valpedo, A.V.; Thompson, G.A. Length-weight and length-length relationship for three marine fish species of commercial importance from southwestern Atlantic Ocean coast. Lat Am J Aquat Res 2020, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, K.L.; Honsey, A.E.; Moe, B.; Venturelli, P.; Reynolds, J. Growing the biphasic framework: Techniques and recommendations for fitting emerging growth models. Methods in Ecology and Evolution 2017, 9, 822–833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carbonara, P.; et al. Biphasic versus monophasic growth curve equation, an application to common sole (Solea solea, L.) in the northern and Central Adriatic Sea. Fisheries Research 2023, 263, 106694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lowerre-Barbieri, S.K.; Brown-Peterson, N.J.; Murua, H.; Tomkiewicz, J.; Wyanski, D.M.; Saborido-Rey, F. Emerging issues and methodological advances in fisheries reproductive biology. Mar Coast Fish [dnlm] 2011, 3, 32–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, H.R.; Peter, R.E. Hormones and Spawning in Fish. Asian Fish Sci 1996, 9, 21–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GLORYS12V1. E.U. Copernicus Marine Service Information (CMEMS). Marine Data Store (MDS). https://doi.org/10.48670/moi-00021 (Accessed on 10-07-2024). [CrossRef]

- Mcbride, R.S.; Somarakis, S.; Fitzhugh, G.R.; Albert, A.; Yaragina, N.A.; Wuenschel, M.J.; Alonso-Fernández, A.; Basilone, G. Energy acquisition and allocation to egg production in relation to fish reproductive strategies. Fish Fish 2015, 16, 23–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Model | Number of parameters | Equation |

|---|---|---|

| 3p VBGM | 3 | |

| Hyper L∞ | 5 | |

| Hyper k | 5 |

| Length class (cm) | Age (yr) | ||||||||||||||||

| 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | Total | |

| 7-8 | 1 | 1 | |||||||||||||||

| 8-9 | 2 | 2 | |||||||||||||||

| 9-10 | 2 | 2 | |||||||||||||||

| 13-14 | 1 | 1 | |||||||||||||||

| 17-18 | 1 | 1 | |||||||||||||||

| 18-19 | 1 | 1 | |||||||||||||||

| 19-20 | 4 | 4 | |||||||||||||||

| 20-21 | 7 | 2 | 1 | 10 | |||||||||||||

| 21-22 | 3 | 7 | 4 | 14 | |||||||||||||

| 22-23 | 10 | 15 | 3 | 28 | |||||||||||||

| 23-24 | 19 | 16 | 2 | 37 | |||||||||||||

| 24-25 | 7 | 28 | 18 | 1 | 54 | ||||||||||||

| 25-26 | 10 | 34 | 15 | 59 | |||||||||||||

| 26-27 | 19 | 31 | 5 | 1 | 56 | ||||||||||||

| 27-28 | 17 | 21 | 12 | 1 | 51 | ||||||||||||

| 28-29 | 3 | 13 | 21 | 7 | 44 | ||||||||||||

| 29-30 | 8 | 15 | 19 | 5 | 47 | ||||||||||||

| 30-31 | 2 | 11 | 7 | 2 | 22 | ||||||||||||

| 31-32 | 3 | 7 | 2 | 12 | |||||||||||||

| 32-33 | 2 | 3 | 5 | ||||||||||||||

| 33-34 | 1 | 3 | 4 | ||||||||||||||

| 34-35 | 1 | 1 | |||||||||||||||

| N | 5 | 1 | - | 16 | 19 | 46 | 57 | 73 | 67 | 47 | 51 | 41 | 22 | 7 | 3 | 1 | 456 |

| TL mean (cm) | 8.7 | 13.3 | - | 20.1 | 21.8 | 23.0 | 24.2 | 25.4 | 26.4 | 28.0 | 28.5 | 29.6 | 30.8 | 31.6 | 33.5 | 34.2 | |

| TL SD (cm) | 0.6 | - | - | 0.9 | 0.6 | 0.9 | 0.8 | 0.8 | 0.9 | 0.9 | 0.9 | 0.9 | 1.0 | 0.8 | 0.3 | - | |

| Parameters | 3p VBGM | Hyper L∞ | Hyper k |

|---|---|---|---|

| L∞ (cm) | 35.22 | 36.79 | 36.70 |

| K (years-1) | 0.13 | 0.12 | 0.12 |

| t0 (years-1) | -2.78 | -2.26 | -2.24 |

| h | - | -0.16 | -0.24 |

| th (years) | - | 3.36 | 3.40 |

| AIC | 1275.36 | 1189.00 | 1189.45 |

| ∆AIC | 86.36 | 0.00 | 0.45 |

| Reference | Region | LWR | Amax (year) | L∞ (cm) | k (year-1) | t0 | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M | F | C | M | F | C | M | F | C | M | F | C | |||||||

| Santos et al. (1995) | Portugal South Coast (Atlantic) | Positive allometry | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | ||||

| Pajuelo & Lorenzo (2000) | Southwest Gran Canaria (Atlantic) | Positive allometry | - | - | 10 | 28.0 | 33.9 | 33.0 | 0.27 | 0.21 | 0.22 | -0.67 | -0.99 | -0.87 | ||||

| Coelho et al. (2005) | Portugal South Coast (Atlantic) | Positive allometry | 13 | 18 | - | 28.8 | 32.3 | 32.1 | 0.29 | 0.18 | 0.18 | -1.47 | -2.56 | -2.91 | ||||

| Abecasis et al. (2008) | Portugal South Coast (Atlantic) | - | - | - | 18 | - | - | 31.8 | - | - | 0.19 | - | - | -2.86 | ||||

| Velasco et al. (2011) | Gulf of Cadiz (Mediterranean) | Positive allometry | - | - | 12 | - | - | 31.7 | - | - | 0.21 | - | - | -1.76 | ||||

| Velasco et al. (2011) | Alboran Sea (Mediterranean) | Positive allometry | - | - | 12 | - | - | 32.1 | - | - | 0.17 | - | - | -2.69 | ||||

| Soykan et al. (2015) | Aegean Sea (Mediterranean) | Isometry | - | - | 6 | - | - | 27.7 | - | - | 0.32 | - | - | - | ||||

| Ílhan (2018) | Aegean Sea (Mediterranean) | Positive allometry | - | - | 4 | 22.5 | 27.8 | 25.6 | 0.34 | 0.2 | 0.25 | -1.55 | -2.35 | -1.94 | ||||

| Di Maio et al. (2020) | Strait of Sicily - Tunisian Coast (Central Mediterranean) | Positive allometry | 6 | 7 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | ||||

| Bentata-Keddar et al. (2020) | Western Algerian coasts (Western Mediterranean) | - | - | - | - | 28.4 | 29.8 | 30.0 | 0.42 | 0.5 | 0.41 | -0.13 | -0.04 | -0.34 | ||||

| Ali-Basha et al. (2023) | Syrian waters | Positive allometry | - | - | 5 | 23.0 | 21.5 | 19.8 | 0.18 | 0.32 | 0.23 | -0.24 | -0.24 | -0.04 | ||||

| Reference | Region | Spawning season | L50 (cm) | LSI (cm) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M | F | ||||||

| Santos et al. (1995) | Portugal South Coast (Atlantic) | May to August | 19.7 | 20.9 | 15-23 | ||

| Pajuelo & Lorenzo (2000) | Southwest Gran Canaria (Atlantic) | October to March | 15.8 | 19.4 | 15-23 | ||

| Coelho et al. (2005) | Portugal South Coast (Atlantic) | May to November | 18.1 | 17.6 | 20-24 | ||

| Abecasis et al. (2008) | Portugal South Coast (Atlantic) | ||||||

| Velasco et al. (2011) | Gulf of Cadiz (Mediterranean) | Autumn, spring and beginning summer (peak April to June) | 18.0 | 21.7 | 23.5 | ||

| Velasco et al. (2011) | Alboran Sea (Mediterranean) | May to October | 17.7 | 20.1 | 21.5 | ||

| Soykan et al. (2015) | Aegean Sea (Mediterranean) | June to September | 13.9 | 14.5 | |||

| Bensahla Talet et al. (2017) | Western Algerian coasts (Western Mediterranean) | April to June andNovember to January | 15.9 | 12.8 | 17.5-26.3 | ||

| Ílhan (2018) | Aegean Sea (Mediterranean) | ||||||

| Di Maio et al. (2020) | Strait of Sicily - Tunisian Coast (Central Mediterranean) | October | 22 | ||||

| Bentata-Keddar et al. (2020) | Western Algerian coasts (Western Mediterranean) | Late spring and autumn | 16.9 | 18.6 | |||

| Ali-Basha et al. (2023) | Syrian waters | ||||||

| This study | Portugal West Coast (Atlantic) | Apr-Oct | 27-31 | ||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).