1. Introduction

The work of long-haul truck drivers (LHTD) involves the transportation of products safely across the road over long distances resulting days, weeks, and sometimes months away from home. This work is highly stressful, lonely and unhealthy because it involves low remuneration, absence of extensive career paths, low autonomy and unsafe working conditions [

1,

2,

3]. These factors negatively affect the health of these workers, contributing to the increase of Chronic Non-Communicable Diseases (CNCD) [

4,

5,

6,

7]. Faced with work requirements of more than 55 hours a week [

6] and the need to remain for long periods away from home, this reality forces LHTDs to use truck stops and rest area, available at gas stations located, in general, along highways to eat, sleep, rest, shower, exercise, connect to the internet to communicate with family and friends, as well as to prepare for another long day of driving [

4,

8,

9].

Although essential, these sites do not always offer the necessary services to meet the basic human needs (BHN) of food, sleep, leisure, safety, physical comfort, personal hygiene, recreation, socialization and physical activity for LHTDs. This situation was aggravated by the difficulty faced by LHTDs in finding parking, toilets and food during the COVID-19 pandemic, contributing to many of them consuming more caffeine and working for longer hours [

10]. Working conditions and life can affect the health of drivers [

5,

11], but few address the satisfaction or perception of workers with the services offered at truck stops and rest areas [

8,

9].

In Brazil, there are laws that protect the rights and responsibilities of LHTDs, establishing minimum standards for safety, health, and comfort in waiting, resting and rest areas [

12]; the places that can be considered as truck stops and rest areas are described in law as road stations; stops and support points; accommodation, hotels or inns; canteens of companies or third parties; and gas stations [

12]. The Special Secretariat of Social Security and Labor and the Ministry of Economy established the minimum conditions of safety, health and comfort of truck stops and rest areas [

13] and the Ministry of Infrastructure, the general procedures to recognize and issue the certification of establishments that fully meet the requirements and minimum sanitary, safety and comfort conditions [

14]. Truck drivers surveyed about what an ideal truck stop and rest area would look like, rated the following as very important: personal hygiene services (bathrooms with hot water showers and that are adapted for people with disabilities), hygiene (washing machine and dryer for laundry, utility sink for washing of other items, dumpster for trash), food (have a kitchen, stove, microwave, and space to eat food prepared in their trucks or in communal kitchens, fast food-type cafeteria, restaurant), space for rest (lounge, T.V, balcony with benches), safety (personal and load from theft and assault, surrounded parking, safety camera, entry in parking with registration or identification, lighting, maintenance of paving), communication (Wi-Fi, information about truck stop services in applications and websites), health services (medical care), exclusive spaces for women drivers, spaces for women near convenience stores, and women’s and male bathrooms that are physically distant from one another [

15].

Services offered at truck stops and rest areas for the satisfaction of basic human needs, prevention of NCCDs and to promote the health and wellbeing of LHTDs are important. Satisfying the basic human needs and having a healthy work and rest environment contributes to achieving the goals of the Global Action Plan for the Prevention and Control of Chronic Non-Communicable Diseases 2023-2030 [

16], as well as the objectives of the UN Agenda 2030 for Sustainable Development [

17]. Still, given the gap in the literature about the perception of drivers regarding the services offered in truck stops and rest areas in Brazil, there is a need for studies that foster discussion and offer support to develop public policies that lead to the construction of adequate truck stops and rest areas that meet the health and work life demands of these essential transportation sector workers -- LHTDs.

This study will support its discussion in evidence from previous studies and Maslow’s Theory of Human Motivation. This theory presents, at the base of the pyramid, the physiological needs, essential for body homeostasis, such as water and nutrients. At the higher levels are the needs of security, social, esteem and self-realization, considered fundamental for the person to feel motivated, and promote his well-being and human health [

18]. Given what is in the literature, this study presented the hypothesis that in general, truck drivers will have a negative perception about most of the services offered in Brazilian truck stops and rest areas. This study aimed to evaluate LHTDs’ perceptions about food, safety, physical activity, rest, and bathroom services offered in truck stops and rest areas in Southern Brazil.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Design

This cross-sectional, quantitative and descriptive study was conducted with LHTDs from Southern Brazil, using a convenience, non-probabilistic sample, with voluntary participation from drivers.

2.2. Ethical Considerations

In this study, ethical principles of research involving human beings were respected, according to Resolution of the National Health Council No. 466 of December 12, 2012. The study was approved by the Ethics Committee, case number 5,892,602 and Certificate of Presentation for Ethics Assessment (CAAE) number 66722622.9.0000.5316.

2.3. Sample and Setting

Inclusion criteria in the study were that participants had to be LHTD employed for greater than six months and could read and speak Portuguese. The exclusion criteria were not to be a LHTD and not able to read and speak Portuguese.

Data was collected in Southern Brazil at several truck stops and rest areas frequented by LHTDs: a dry port characterized as the second largest in Latin America, a maritime port, three truck stops and rest points, and in the waiting room of a health service of a union of road transport workers. The sample was composed of 255 drivers, 175 long-haul truck drivers, the others were excluded for transporting people or cargo in the urban and interurban sector, not making use of the truck stop and rest areas used by LHTD at the gas stations.

2.4. Data Collection

Procedures

The participants were approached in person by one of the researchers, accompanied by four nursing master’s students, four nursing academics and one in psychology academic, all of whom previously had received guidance and ongoing training on the procedures involving data collection. In this opportunity, with each contact with a potential participant, researchers explained the objectives of the study and the type of participation desired; the Free and Informed Consent Form was read and two forms were signed -- one was given to the participant and the other the researcher kept. Data collection took place from March to August 2023.

2.5. Instruments

Data collection instruments were presented LHTDs to be self-completed, in paper and pencil, however, some participants needed support in reading the items, likely due to literacy. A sociodemographic form with 25 questions and an instrument with 6 items was used to evaluate the perception of LHTD on the services of rest, food, toilets, safety and physical activity, offered at truck stops and rest areas in Brazil and if the service was free or paid. This instrument was developed by the authors and uses a Likert-type scale with 6 items about the rest, food, toilets, safety and physical activity service and about the payment of the service was free or paid ranging from terrible, bad, average, good and excellent, and an option of service unavailable in truck stops and rest areas frequented by LHTD.

A field note book was used to record the researchers’ perceptions about the environment, the organization of health care services, ports and stopping and resting points where data collection took place and it was used to support the description of the data and the data analysis.

2.6. Data Analysis

The data was entered in a Google form and then analyzed from the Excel for Windows® spreadsheet file. For each variable analyzed, the value observed in the sample (n) and the percentage (%) were expressed.

4. Discussion

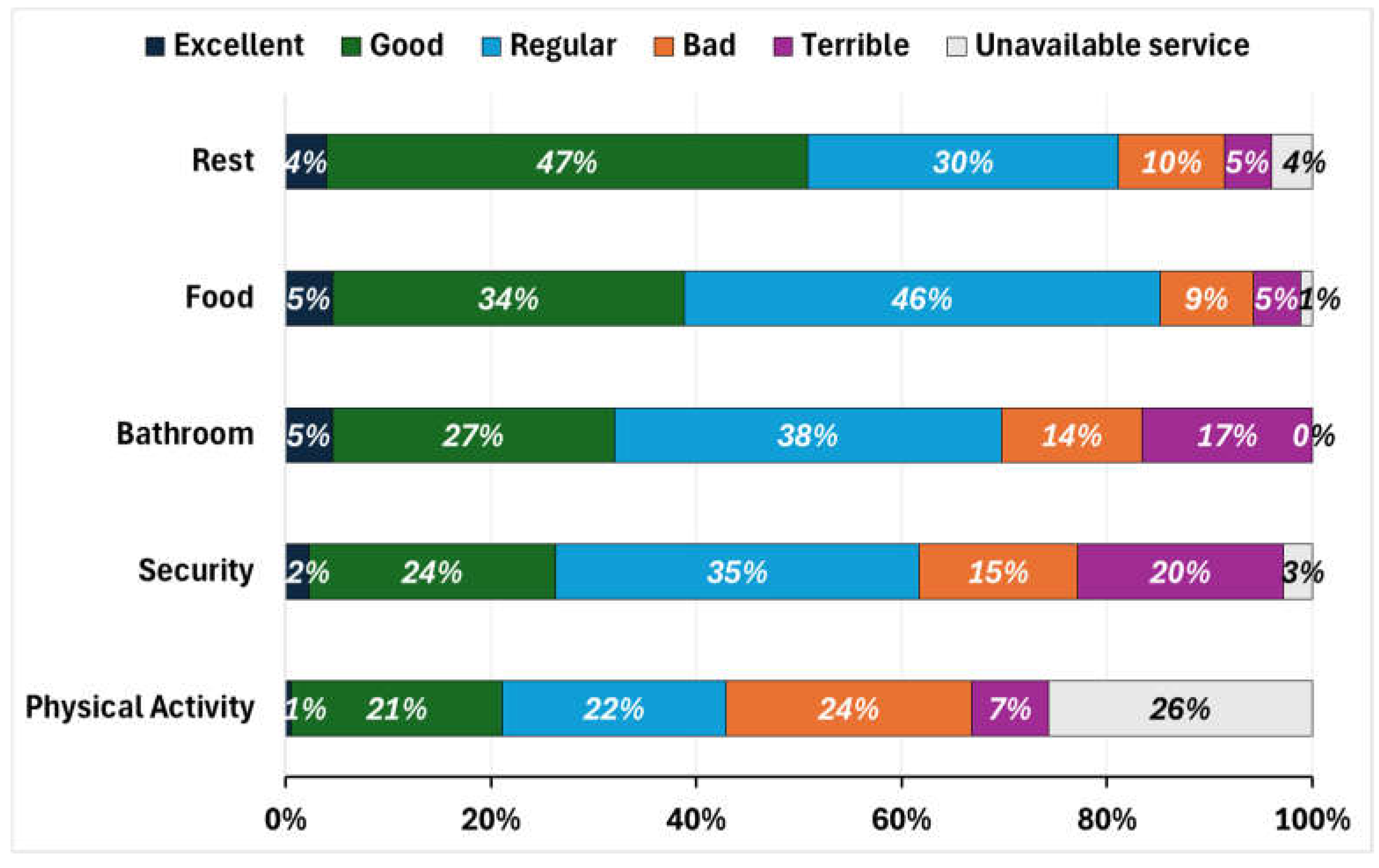

This study presented the perception of Brazilian and foreign long-haul truck drivers about the services offered at truck stops and rest areas in Brazil. This is the first known study to examine LHTDs’ perception of truck stops and rest areas in Brazil. Truck stops and rest areas are viewed as part of the occupational work environment of these workers. This study found that satisfaction with physical activity, security and bathroom services were worse than satisfaction with rest and food services. In addition, it was identified the collection for parking services and personal hygiene.

The spaces for the practice of physical activities were perceived by drivers as “bad” or “terrible”, by 30.4%, followed by “unavailable” by 27.7%. The negative evaluation may be related to the quality of the structure at truck stops and rest area for the practice of physical activity. The lack of adequate space contributes to sedentary behavior and consequently to the development of chronic diseases such as obesity, hypertension, diabetes. Previous studies have shown that drivers practice little physical activity [

19] possibly, due to the high workload and few opportunities to exercise.

Physical exercise is a physiological need laid out at the base of the hierarchy of needs pyramid [

18], and has as benefits the reduction of stress, the risk of chronic diseases, improve sleep quality, increase strength, flexibility and physical and emotional balance [

20]. The difficulty in satisfying the need for physical activity can trigger a feeling of frustration, increase depressive symptoms, obesity, hypertension and or diabetes. To make truck stops and rest area environments healthier, several researchers recommend the installation of gyms, availability of hiking trails and physical activity with supervision of health professionals at stopping and resting points [

5,

21].

The security service was perceived as “average” by 35.1%, followed by “bad” or “terrible” by 33.5% of LHTD. Safety may have different meanings, however, when referring to truck stop and rest areas, it is understood that safety should be related to aspects involving the physical structure of the truck stop and rest area such as opening hours 24 hours for 7 days a week, lighting, paving, signaling, access ramps for wheelchair users, fire extinguishers, internet access, parking area and exclusive supply for the truck, enclosed space, monitoring by cameras, surveillance service, aiming to safeguard users, trucks and cargo. Urban violence is a social phenomenon, and this may have influenced the negative perception by drivers, considering that truck stop and rest areas do not always present the minimum conditions described in the legislation of offering electronic surveillance or monitoring. As well as, the availability of enclosed parking with access control, in those that require payment for the parking service [

13]. A previous study revealed difficulties faced by North American drivers to find parking spaces on weekdays, as well as the importance of internet access, considered very important for 51% of drivers [

8].

Safety is a construct that is at the base of the hierarchy of needs pyramid, arranged in the second level, after physiological needs. It involves individual security, body, employment, resources, housing, family and health, against dangers and threats [

18]. When this need is not met, it leads to a state of stress, due to the feeling of insecurity and anxiety, which trigger neurophysiological changes, which lead to increased heart beats, blood pressure and blood glucose levels, sleep disturbance and difficulty in concentration. A previous study showed that post-traumatic stress disorder was a predictor of the use of mental health care among LHTD [

22]. Thus, the working and rest environment needs to provide safety to preserve the physical and mental health of LHTD.

The perception of drivers as to bathroom services was considered to be “average” by 36.6%, followed by “good” or “excellent” by 35.1%. This service deals with the sanitary facilities, a personal hygiene space, with basic objects and items such as sinks, taps, soap, mirrors, toilets, showers with hot and cold water, toilet paper, female absorbents, paper towel or hand dryers, trash bins, lighting and space to store belongings while doing hygiene. In Brazil, the minimum conditions for the services of truck stops and rest areas, presented in Ordinance 1,343/2019, also provides that the bathrooms are separated by sex, and that they are individualized and sanitized [

13]. This personal hygiene space, in addition to containing the basic items, is a space for satisfying a basic human need [

18] and needs to be easily accessible. The absence of hot water showers in the southern region of Brazil, whose winter is usually severe, of low temperatures, was mentioned by some drivers, when completing the form. Failure to comply with the minimum conditions, affects physiological elimination, self-care, security, privacy and therefore, its structure needs to offer an environment that meets these needs, be clean and pleasant to ensure safety and preserve the health of users. A study conducted in the United States revealed that drivers considered this service very important (62%) [

8].

The act of resting encompasses another basic need, sleep. Resting and sleeping are considered physiological needs, arranged at the base of the hierarchy of needs pyramid because they are fundamental for biological, social and physical balance [

18]. The rest service was perceived as “good” or “excellent” by more than 50% of drivers, followed by “average” by another 29.8%. This result may be related to the understanding that most consider the truck as a rest space and where they usually sleep [

23].

The perception about this service involves other aspects, possibly disregarded by the drivers, which goes beyond a calm and quiet environment for rest in the truck, which is fundamental for a good night’s sleep, considering that poor sleep hygiene was considered a predictor of stress at work [

5]. In this way, the rest service can include the environment outside the work space, in this case, outside the truck, which allows contact with nature, socialization, such as with the availability of spaces with green area, benches, networks, games, TV, internet access and hotel service. A previous study revealed that internet access was considered very important for 51% of drivers [

8]. Promoting adequate rest spaces have the potential to prevent the risk of cardiometabolic diseases, obesity, cancer, reduce social isolation, stress and increase the well-being of LHTD [

10,

21,

24]. The perception regarding the food service varied between “good” or “excellent” to 44.0%, followed by “average” for 41.4% of the drivers. This result may be related to the practice of drivers preparing their own meal on the truck, in their kitchen boxes, as mentioned by some participants, for considering healthier. While others eat ready-made snacks or diner at the truck stop and rest areas’ restaurant. Previous studies have shown that 73% of drivers used to eat food brought from home, while 37.0% regularly or always served on truck stops. To conserve and prepare food, 94% had refrigerator, 62% gas pot and 8% microwave in the truck. The items brought at home were fruits (62%), sausages (50.6%), sandwiches (38.7%), pre-ready meals (37%), sweets (35.4%) and raw vegetables (31%) [

25]. As for food quality, 88% consumed fewer vegetables than recommended, 63% consumed at least one health-damaging food per day and 65% consumed a can of sugary drink per day [

19]. It is understood that despite the positive perception of food in Brazilian truck stop and rest areas, drivers reported informally, when completing the form, that the food options available in these places often have few or no options of fruits and salads, offering options of ultra-processed foods, rich in saturated fat, or fastfoods. The literature showed a significant correlation between drivers who eat meals in restaurants with increased weight [

10]. Thus, it is understood that malnutrition is related to the quality of the foods available for consumption in truck stop and rest areas and increases the risk of overweight, obesity and other cardiometabolic diseases related to diet, bringing irreparable consequences to people, families and communities [

26].

The choice of high-energy foods may be related to the time spent on work and the lack of it to prepare and or hold balanced meals. Studies have shown that the daily workload of LHTD ranged from more than 10 hours (53%) [

21]; up to more than 13 hours per day (37.5%) [

6]. Thus, the organization of work can compromise the adoption of healthy behaviors by not respecting the human right to adequate food and satisfying the basic human need for quality food. Feeding is a physiological need, arranged at the base of the hierarchy of needs pyramid [

18]. As a result, poor diet can affect driver health by contributing to increased cholesterol levels, blood pressure and diabetes [

21]. Another factor that can influence the perception of food service is the quality of the environment to carry out the meal, which needs to be clean, comfortable, endowed with tables and chairs, as recommended by the Ministry of Economy and Labor Brazil, in Ordinance 1.343/2019 [

13], thus, adopting healthy behavior requires structural changes that provide quality food meals to LHTD.

The payment requirement to use parking and personal hygiene services was reported by 68.1% of LHTD. Brazilian legislation provides that the services of personal hygiene and parking are offered free of charge to users and if it requires the payment of a fee for the permanence of the vehicle, it must be surrounded and have access control (Ordinance 1./2019)[

13]. However, this is not the reality of most truck stop and rest areas. In this sense, charging for these services can be a stress-triggering for LHTDs, since it can compromise the security and finances of the worker. The physiological needs of physical protection and search for shelter are at the base of the hierarchy of needs pyramid [

18], and in case of impossibility of payment, the driver will need to seek another place to park after long hours of work. In addition, when facing difficulties of access to other services essential for the satisfaction of basic human needs such as personal hygiene, elimination, comfort and rest, drivers can present impairment of their health and well-being, such as that occurred during the COVID-19 pandemic [

10].

Limitations

Although this study is the first to evaluate the perception of LHTD regarding the services offered at truck stops and rest areas in southern Brazil, and the results indicated the items with the greatest fragility, other studies covering other regions of Brazil, they are necessary for a better understanding of this phenomenon among road transport workers.

Contributions to practice

It is expected that the results presented here may contribute to support the health care of drivers aiming at the prevention of chronic non-communicable diseases, as well as instigate other studies and the development of public policies for advances in the quality of services offered at the truck stop and rest areas in Brazil, aiming at the well-being and health of LHTD.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, F.L., and M.S; methodology, F.L.; software, F.L, and F.L.G; validation, F.L., M.S., R.P.G, K.R., W.T.A., F.L.G., and E.S; formal analysis, F.L., M.S., R.P.G, K.R., W.T.A., F.L.G., and E.S; investigation, F.L., M.S., R.P.G, K.R., W.T.A., F.L.G., and E.S; data curation, F.L.; writing—original draft preparation, F.L., M.S., R.P.G, K.R., W.T.A., F.L.G., and E.S.; writing—review and editing, F.L., M.S., R.P.G, K.R., W.T.A., F.L.G., and E.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.