Submitted:

25 July 2024

Posted:

26 July 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

Developing a Draft Proactive Deprescribing Process of Steps and Activities

Validation of the Proactive Deprescribing Process of Steps and Activities

Survey Development

Survey Distribution

Sample Size Justification

Analysis

3. Results

Developing a Draft Process of Proactive Deprescribing Steps and Activities

Validation of the Proactive Deprescribing Process of Steps and Activities

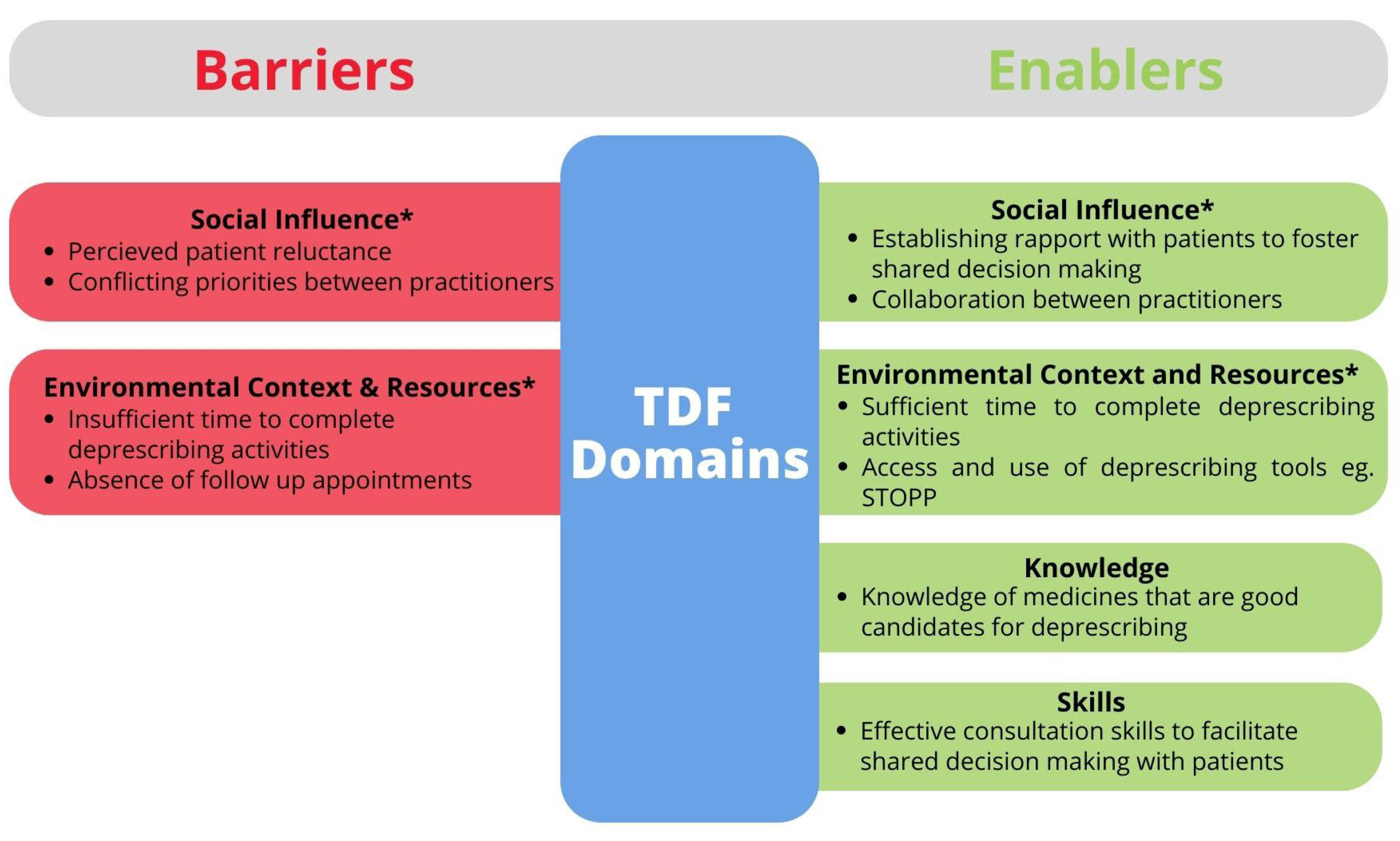

“Patients may have been started and told they need to be on [the medicine] for life ... They may also worry that their condition will deteriorate, and this is more of a concern than potential side effects that may or may not occur.”Pharmacist

“Most challenging are colleagues of other specialties who in some instances are reluctant to stop some medications that are potentially harmful.”Doctor

“Having a multidisciplinary team approach as well as patient engagement. Good communication between primary and secondary care is also important.”Pharmacist

“I need sufficient time, resources and ability to stop medicines successfully on a daily basis.”Pharmacist

4. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

Appendix B

References

- Scott IA, Hilmer SN, Reeve E, Potter K, Le Couteur D, Rigby D, et al. Reducing inappropriate polypharmacy: the process of deprescribing. JAMA Internal Medicine 2015;175:827–34.

- Scott S, Clark A, Farrow C, May H, Patel M, Twigg MJ, et al. Deprescribing admission medication at a UK teaching hospital; a report on quantity and nature of activity. International Journal of Clinical Pharmacy 2018;40:991–6. [CrossRef]

- Anderson K, Stowasser D, Freeman C, Scott I. Prescriber barriers and enablers to minimising potentially inappropriate medications in adults: a systematic review and thematic synthesis. BMJ Open 2014;4:e006544. [CrossRef]

- Scott S, Twigg MJ, Clark A, Farrow C, May H, Patel M, et al. Development of a hospital deprescribing implementation framework: a focus group study with geriatricians and pharmacists. Age and Ageing 2020;49:102–10. [CrossRef]

- General Medical Council. Good practice in prescribing and managing medicines and devices 2021.

- McDonald EG, Wu PE, Rashidi B, Wilson MG, Bortolussi-Courval É, Atique A, et al. The MedSafer study—electronic decision support for deprescribing in hospitalized older adults: a cluster randomized clinical trial. JAMA Internal Medicine 2022;182:265–73.

- Thillainadesan J, Gnjidic D, Green S, Hilmer SN. Impact of deprescribing interventions in older hospitalised patients on prescribing and clinical outcomes: a systematic review of randomised trials. Drugs & Aging 2018;35:303–19. [CrossRef]

- Thio SL, Nam J, van Driel ML, Dirven T, Blom JW. Effects of discontinuation of chronic medication in primary care: a systematic review of deprescribing trials. British Journal of General Practice 2018;68:e663–72. [CrossRef]

- Medication Without Harm 2017.

- Schuling J, Gebben H, Veehof LJG, Haaijer-Ruskamp FM. Deprescribing medication in very elderly patients with multimorbidity: the view of Dutch GPs. A qualitative study. BMC Family Practice 2012;13:1–7. [CrossRef]

- O’Mahony D, Gudmundsson A, Soiza RL, Petrovic M, Cruz-Jentoft AJ, Cherubini A, et al. Prevention of adverse drug reactions in hospitalized older patients with multi-morbidity and polypharmacy: the SENATOR* randomized controlled clinical trial. Age and Ageing 2020;49:605–14. [CrossRef]

- Scott S, Wright DJ, Bhattacharya D. The role of behavioural science in changing deprescribing practice. Br J Clin Pharmacol 2021;87:39–41. https://doi.org/10.1111/bcp.14595.

- Skivington K, Matthews L, Simpson SA, Craig P, Baird J, Blazeby JM, et al. A new framework for developing and evaluating complex interventions: update of Medical Research Council guidance. Bmj 2021;374.

- Reeve E, Shakib S, Hendrix I, Roberts MS, Wiese MD. Review of deprescribing processes and development of an evidence-based, patient-centred deprescribing process. British Journal of Clinical Pharmacology 2014;78:738–47.

- Elwyn G, Frosch D, Thomson R, Joseph-Williams N, Lloyd A, Kinnersley P, et al. Shared decision making: a model for clinical practice. Journal of General Internal Medicine 2012;27:1361–7. [CrossRef]

- Alexander GC, Sayla MA, Holmes HM, Sachs GA. Prioritizing and stopping prescription medicines. CMAJ 2006;174:1083–4. [CrossRef]

- Bain KT, Holmes HM, Beers MH, Maio V, Handler SM, Pauker SG. Discontinuing medications: a novel approach for revising the prescribing stage of the medication-use process. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society 2008;56:1946–52. [CrossRef]

- Brandt N, Stefanacci R. Discontinuation of unnecessary medications in older adults. The Consultant Pharmacist® 2011;26:845–54. [CrossRef]

- Gordon SF, Dainty C, Smith T. Why and when to withdraw drugs in the elderly and frail. Prescriber 2012;23:47–51. [CrossRef]

- Hardy JE, Hilmer SN. Deprescribing in the last year of life. Journal of Pharmacy Practice and Research 2011;41:146–51.

- Le Couteur D, Gnjidic D, McLachlan A. Deprescribing. Australian Prescriber 2011;34.

- Meeks TW, Culberson JW, Horton MS. Medications in long-term care: when less is more. Clinics in Geriatric Medicine 2011;27:171–91. [CrossRef]

- Ostini R, Hegney D, Jackson C, Tett SE. Knowing how to stop: ceasing prescribing when the medicine is no longer required. Journal of Managed Care Pharmacy 2012;18:68–72. [CrossRef]

- Scott IA, Gray LC, Martin JH, Mitchell CA. Minimizing inappropriate medications in older populations: a 10-step conceptual framework. The American Journal of Medicine 2012;125:529–37. [CrossRef]

- Woodward MC. Deprescribing: achieving better health outcomes for older people through reducing medications. Journal of Pharmacy Practice and Research 2003;33:323–8. [CrossRef]

- Gordon RA. Social desirability bias: A demonstration and technique for its reduction. Teaching of Psychology 1987;14:40–2. [CrossRef]

- Anthoine E, Moret L, Regnault A, Sébille V, Hardouin J-B. Sample size used to validate a scale: a review of publications on newly-developed patient reported outcomes measures. Health and Quality of Life Outcomes 2014;12:2. [CrossRef]

- Scott S, Clark A, Farrow C, May H, Patel M, Twigg MJ, et al. Attitudinal predictors of older peoples’ and caregivers’ desire to deprescribe in hospital. BMC Geriatrics 2019;19:1–11.

- Diamond IR, Grant RC, Feldman BM, Pencharz PB, Ling SC, Moore AM, et al. Defining consensus: a systematic review recommends methodologic criteria for reporting of Delphi studies. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology 2014;67:401–9. [CrossRef]

- Mayring P. Qualitative content analysis. A Companion to Qualitative Research 2004;1:159–76.

- O’Mahony D, O’Sullivan D, Byrne S, O’Connor MN, Ryan C, Gallagher P. STOPP/START criteria for potentially inappropriate prescribing in older people: version 2. Age and Ageing 2014;44:213–8. [CrossRef]

- Weir KR, Ailabouni NJ, Schneider CR, Hilmer SN, Reeve E. Consumer attitudes towards deprescribing: a systematic review and meta-analysis. The Journals of Gerontology: Series A 2021. [CrossRef]

- Weir K, Nickel B, Naganathan V, Bonner C, McCaffery K, Carter SM, et al. Decision-making preferences and deprescribing: perspectives of older adults and companions about their medicines. The Journals of Gerontology: Series B 2018;73:e98–107. [CrossRef]

- Martin P, Tamblyn R, Benedetti A, Ahmed S, Tannenbaum C. Effect of a pharmacist-led educational intervention on inappropriate medication prescriptions in older adults: the D-PRESCRIBE randomized clinical trial. Jama 2018;320:1889–98.

- Okeowo D, Patterson A, Boyd C, Reeve E, Gnjidic D, Todd A. Clinical practice guidelines for older people with multimorbidity and life-limiting illness: what are the implications for deprescribing? Therapeutic Advances in Drug Safety 2018;9:619–30.

- Kocurek B. Promoting medication adherence in older adults… and the rest of us. Diabetes Spectrum 2009;22:80–4. [CrossRef]

- Reeve E, To J, Hendrix I, Shakib S, Roberts MS, Wiese MD. Patient barriers to and enablers of deprescribing: a systematic review. Drugs & Aging 2013;30:793–807. [CrossRef]

- Bloomfield HE, Greer N, Linsky AM, Bolduc J, Naidl T, Vardeny O, et al. Deprescribing for community-dwelling older adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of General Internal Medicine 2020;35:3323–32. [CrossRef]

- Mudge A, Radnedge K, Kasper K, Mullins R, Adsett J, Rofail S, et al. Effects of a pilot multidisciplinary clinic for frequent attending elderly patients on deprescribing. Australian Health Review 2015;40:86–91. [CrossRef]

- Michie S, Johnston M, Rothman AJ, de Bruin M, Kelly MP, Carey RN, et al. Developing an evidence-based online method of linking behaviour change techniques and theoretical mechanisms of action: a multiple methods study. Health Services and Delivery Research 2021;9:1–168. [CrossRef]

- Sherman SJ, Corty E. Cognitive heuristics. 1984.

- Dalton K, O’Mahony D, Cullinan S, Byrne S. Factors affecting prescriber implementation of computer-generated medication recommendations in the SENATOR trial: a qualitative study. Drugs & Aging 2020;37:703–13. [CrossRef]

- Dowding D, Merrill JA. The development of heuristics for evaluation of dashboard visualizations. Applied Clinical Informatics 2018;9:511–8. [CrossRef]

- Bekker HL. The loss of reason in patient decision aid research: do checklists damage the quality of informed choice interventions? Patient Education and Counseling 2010;78:357–64.

- Scott S, May H, Patel M, Wright DJ, Bhattacharya D. A practitioner behaviour change intervention for deprescribing in the hospital setting. Age and Ageing 2021;50:581–6. [CrossRef]

- Scott S, Atkins B, Kellar I, Taylor J, Keevil V, Alldred DP, et al. Co-design of a behaviour change intervention to equip geriatricians and pharmacists to proactively deprescribe medicines that are no longer needed or are risky to continue in hospital. Research in Social and Administrative Pharmacy 2023;19:707–16. [CrossRef]

- Grindell C, Coates E, Croot L, O’Cathain A. The use of co-production, co-design and co-creation to mobilise knowledge in the management of health conditions: a systematic review. BMC Health Services Research 2022;22:877. [CrossRef]

- Gillam SJ, Siriwardena AN, Steel N. Pay-for-performance in the United Kingdom: impact of the quality and outcomes framework—a systematic review. The Annals of Family Medicine 2012;10:461–8. [CrossRef]

- Linsky A, Zimmerman KM. Provider and system-level barriers to deprescribing: interconnected problems and solutions. Public Policy & Aging Report 2018;28:129–33. [CrossRef]

- Bradley N. Sampling for Internet Surveys. An Examination of Respondent Selection for Internet Research. Market Research Society Journal 1999;41:1–10. [CrossRef]

- Cane J, Richardson M, Johnston M, Ladha R, Michie S. From lists of behaviour change techniques (BCTs) to structured hierarchies: Comparison of two methods of developing a hierarchy of BCTs. British Journal of Health Psychology 2015;20:130–50. [CrossRef]

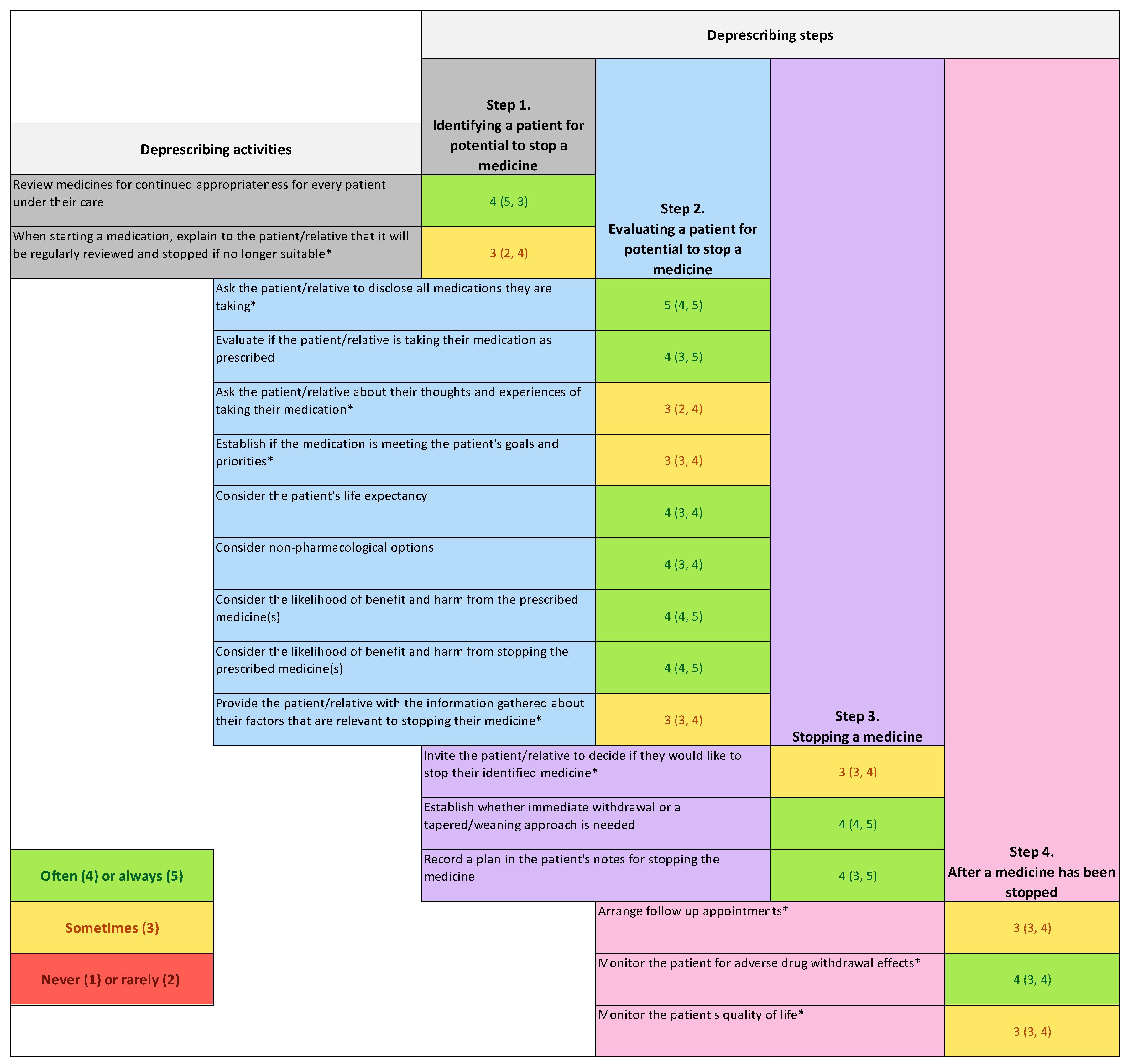

| Proactive deprescribing step | Activities |

| Step 1. Identify a patient for potential stop of a medicine | Review medicines for continued appropriateness for every patient under their care [17,19,22,25] When starting a medication, explain to the patient/relative that it will be reviewed regularly and stopped if no longer suitable* [21,23] |

| Step 2. Evaluate a patient for potential stop of a medicine | Ask the patient/relative to disclose all medications they are taking* [16,20,24,25] Evaluate if the patient/relative is taking their medication as prescribed [25] Ask the patient/relative about their thoughts and experiences of taking their medication* [25] Establish if the medication is meeting the patient’s goals and priorities* [20,24] Consider the patient’s life expectancy [20,24] Consider alternative non-pharmacological options [16] Consider the likelihood of benefit and harm from continuing to prescribe the medicine(s) [17,18,24] Consider the likelihood of benefit and harm from stopping the medicine(s) [17] Provide the patient/informal caregiver with the information gathered about their factors that are relevant to stopping their medicine* [25] |

| Step 3. Stop a medicine(s) | Invite the patient/informal caregiver to decide if they would like to stop their identified medicine* [22] Establish whether immediate withdrawal or a tapered or weaning approach is needed [23] Recording a plan for stopping the medicine in the patient’s notes or record [17,18] |

| Step 4. After a medicine has been stopped | Arrange follow up appointments* [20] Monitoring the patient for adverse drug withdrawal effects* [17] Monitoring the patient’s quality of life* [24] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).