1. Introduction

Inflammatory myofibroblastic tumor (IMT) is a rare soft tissue tumor of mesenchymal origin that falls under the umbrella of inflammatory pseudotumor (IPT) disorders, encompassing a broad range of non-neoplastic and neoplastic entities. These include inflammatory myofibroblastic tumor (IMT), pseudosarcomatous myofibroblastic proliferations (PMPs) of the genitourinary tract, postinfectious/reparative disorders, and IPTs affecting various anatomical sites such as the lymph node, spleen, and orbit [

1]. IPTs are characterized by an inflammatory infiltrate comprising lymphocytes, plasma cells, histiocytes, and varying proportions of fibroblasts and myofibroblasts [

1,

2].

In a comprehensive review of the literature, Badahori and Liebow (1973) reported 40 cases of this entity, initially opting for the terminology "plasma cell granuloma" to better reflect the lesion's histological characteristics [

3,

4]. Subsequent reports of 27 cases by Spencer in 1984 [

5] and 32 cases by Matsubara et al. in 1988 [

6] further explored this condition, referring to it as "plasma cell-histiocytoma complex" when examining the clinical and pathological features of these cases.

Historically, terms such as inflammatory myofibrohistiocytic proliferation, pseudosarcomatous myofibrohistiocytic proliferation, and inflammatory fibrosarcoma have been used to describe this entity. The first documented incidence of IMT dates back to 1939, as reported by Brunn [

7]. The clinical course of IMTs can vary widely, ranging from benign behavior to metastasis, local tissue invasion, or malignant transformation. This diverse spectrum of presentations may manifest as cough, hemoptysis, constitutional symptoms, dyspnea, or remain asymptomatic in approximately half of cases [

8].

Given its nonspecific clinical presentation and unpredictable nature, the diagnosis and management of inflammatory myofibroblastic tumors pose significant challenges. IMTs are notably rare in adults, constituting less than 1% of all adult lung tumors [

9]. The varied clinical course and potential for aggressive behavior involved in diagnosing and treating these unique entities warrant a multidisciplinary approach coupled with strong clinical suspicion.

2. Case Report

A 26-year-old male presented with a history of dyspnea persisting for 2 months, prompting medical evaluation. Following diagnosis of an Inflammatory Myofibroblastic Tumor (IMT), the patient underwent a lobectomy of the right lower lobe to address the condition. Subsequent imaging in the form of a post-operative chest CT revealed the presence of residual soft tissue mass surrounding the right bronchus, leading to a referral to our institution for further management.

The patient's medical history was unremarkable, with no significant past medical conditions or family history of malignant diseases. Additionally, cranial MRI did not reveal any pathological findings. Prior imaging conducted at the previous healthcare facility had identified a pleural mass in the lower lobe of the right lung through chest radiography and CT scans.

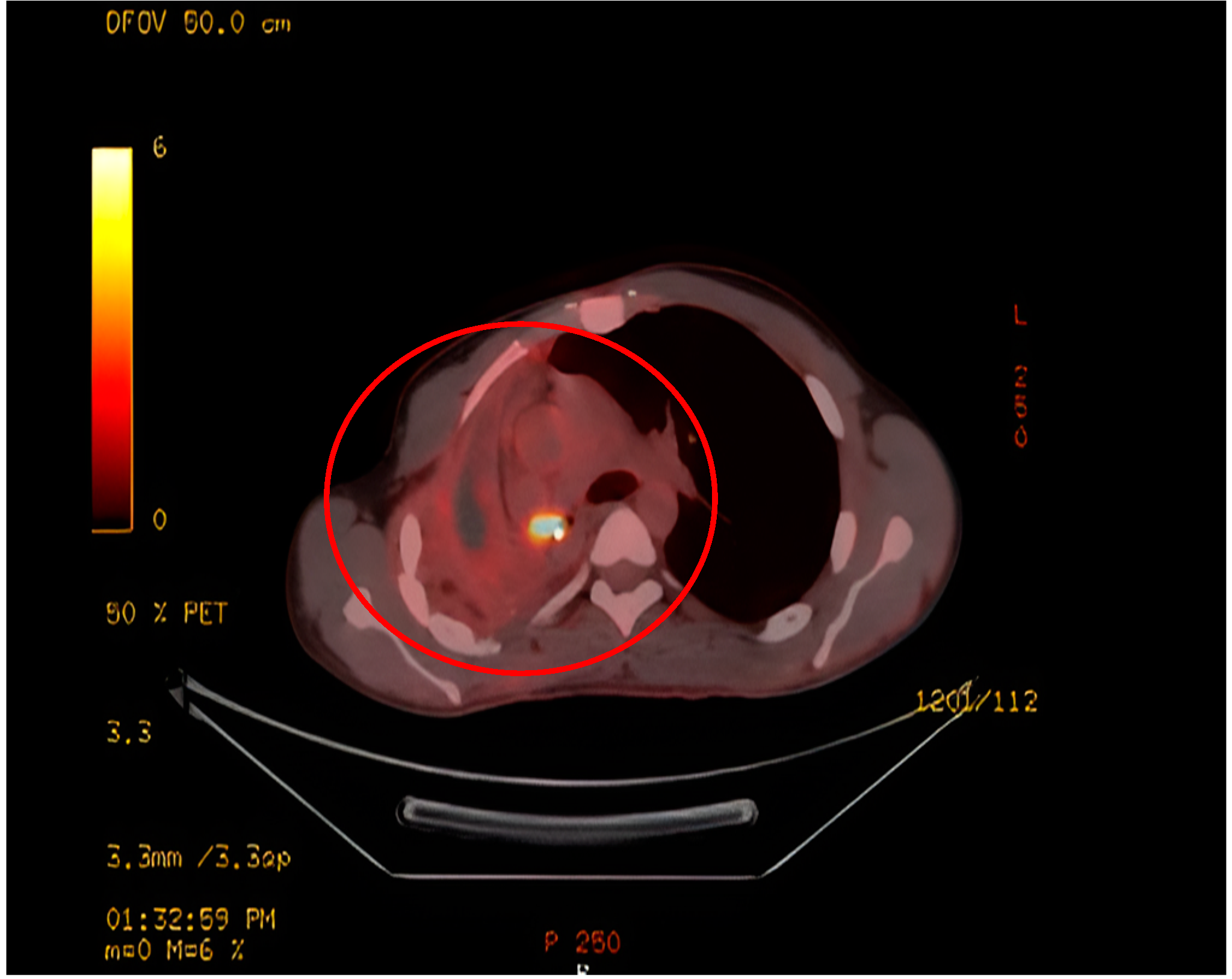

Upon evaluation at our institution, a chest radiograph displayed a sizable homogenous opacity in the right inferior mediastinum, prompting the ordering of a PET scan. The PET scan unveiled a hypermetabolic lesion located in the right main bronchus, as illustrated in

Figure 1. Subsequent examination via flexible bronchoscopy exposed a fistula in the right bronchus intermedius and an elongated bronchial stump on the right side extending towards the secondary carina. Despite these findings, the patient's general clinical examination was unremarkable.

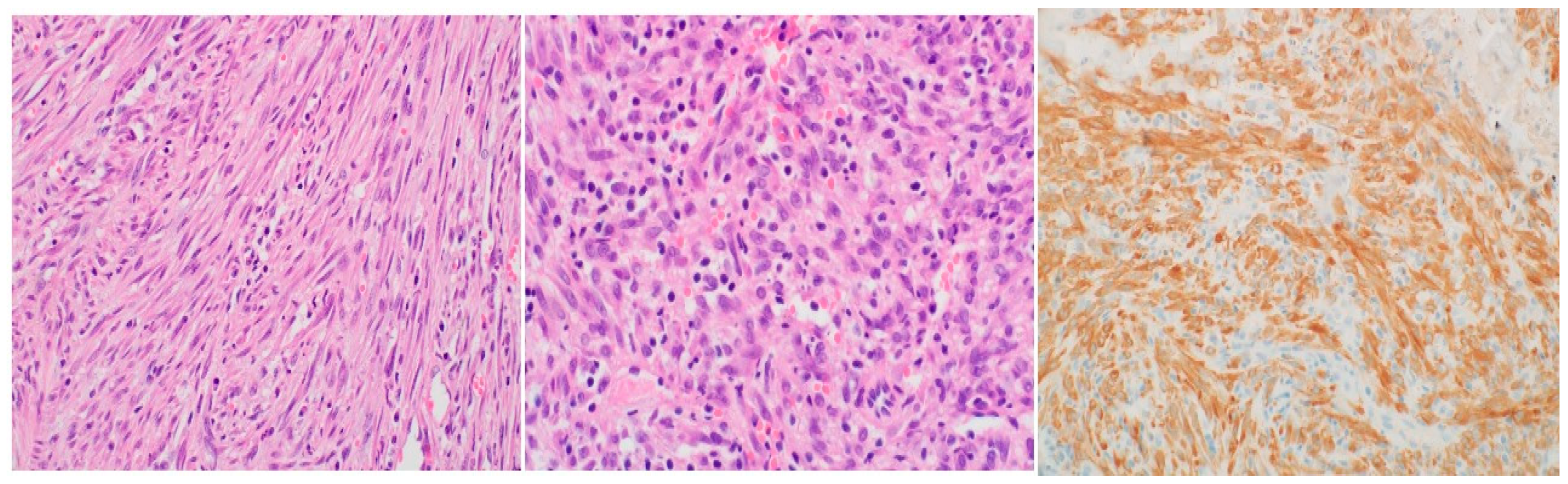

Histopathological analysis utilizing hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining exhibited a proliferation of spindle cells infiltrated by lymphocytes and plasma cells (

Figure 2). Immunohistochemistry further revealed neoplastic cells positive for ALK, focally positive smooth muscle actin (SMA), and negative CD34 and desmin, ultimately confirming the diagnosis of IMT based on the histological examination. Following a review of the histopathology from the primary hospital and validation of the IMT diagnosis by our lung pathologist, a decision was made to proceed with a re-resection of the tumor and revision of the right main bronchus stump that had been previously divided at the flush with the carina.

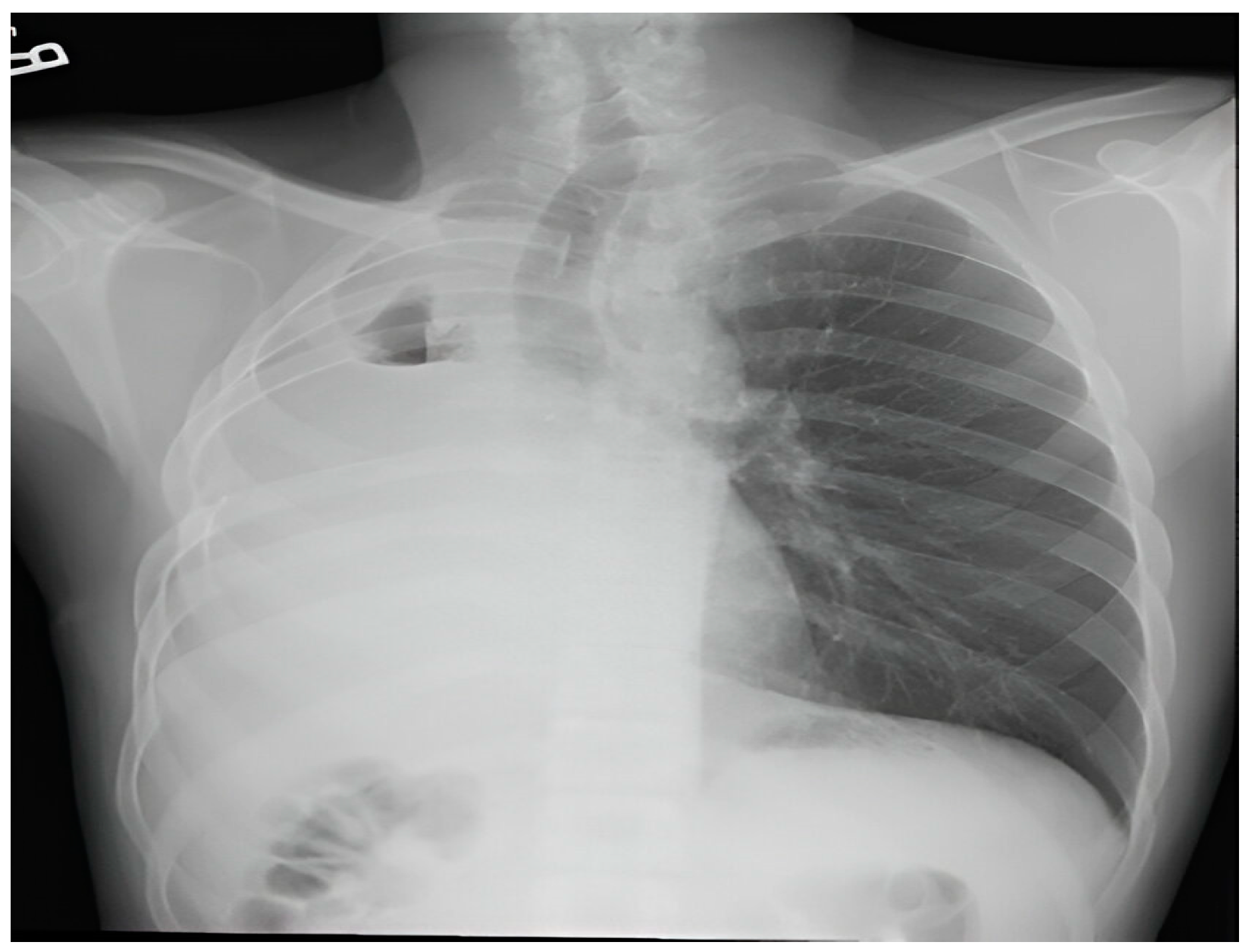

The patient's recovery following surgery was uncomplicated, and he was discharged on the fifth day post-operation. Subsequent follow-up examinations indicated no lymph node involvement and showed the patient to be asymptomatic with satisfactory findings on follow-up X-rays conducted at weeks 4 and 12 post-discharge (

Figure 3).

3. Discussion

The inflammatory myofibroblastic tumor (IMT), first documented in the lung in 1939, is a rare benign lesion, comprising just 0.7% of all lung tumors [

10]. Historically, it has been referred to by various names such as inflammatory pseudotumor, plasma cell granuloma, histiocytoma, or fibroxanthoma, which has led to confusion in understanding its natural history [

10].As a result, Umiker and Iverson proposed grouping these lesions under the term inflammatory pseudotumor [

11].

Morphologically, IMTs simulate a tumor and are histologically composed of inflammatory cells with complete fibroblast maturity. Although typically reported in pediatric age groups, particularly in children under 16 years old without gender predilection, it is noteworthy that our case involved a 26-year-old male, which is atypical [

10]. Common symptoms include cough, chest pain, dyspnea, and occasional hemoptysis [

10]. However, in our case, the patient presented primarily with shortness of breath, without fever or chest pain.

The etiology and pathogenesis of IMT remain unclear, although it is often linked to a post-inflammatory process [

12]. Histopathologically, Coffin et al. described three distinct patterns: compact spindle cell, vascular/myxoid, and hypocellular fibrous patterns, with the spindle cell pattern predominating overall [

2] and in our case . The diagnosis of IMT can be challenging based on a single biopsy, necessitating complete resection for definitive diagnosis [

12].

Despite their benign nature, IMTs can exhibit invasive behavior or metastasis [

12]. While most cases are associated with exaggerated inflammatory response to tissue damage and subsequently pseudotumor formation, some exhibit clonal chromosomal changes, such as chromosome 2p23 and ALK gene activation, suggesting a neoplastic origin [

13]. Approximately half of IMT patients present with cytogenetic translocations at 2p23, leading to ALK protein overexpression, as seen in our case [

9].Recent studies have linked these chromosomal abnormalities to aggressive tumor behavior and local recurrence, reinforcing the classification of IMT as a neoplasm rather than a reactive condition [

9].

Radiologically, IMTs present with variable and nonspecific features depending on their location [

14]. On CT, Pulmonary IMTs show heterogeneous enhancement and may be associated with atelectasis and/or pleural effusions. Amorphous or dystrophic calcifications in pulmonary IMTs are frequently present, usually in children more than adults [15, 16]. MRI can reveal heterogeneous signal intensities, and FDG-PET scan demonstrates high uptake [

14]. In this case, there was intense FDG uptake noted in a circular pattern beneath the right main bronchus.

Complete surgical resection remains the treatment of choice for IMT, offering an excellent prognosis when achieved [

14]. For more extensive cases, lobectomy or pneumonectomy may be necessary to ensure radical excision [

14]. ALK RTK inhibitors such as crizotinib, alectinib, and ceritinib have been noted to be effective in both extrapulmonary and pulmonary IMTs if ALK rearrangement is present, and crizotinib may be effective if ROS1 kinase fusions are present [

17]. Prognosis depends on the quality of surgical resection and tumor size [

14]. Differential diagnoses include organized pneumonia, lymphoma, and solitary fibrous tumor, differentiated by specific markers and histological features [

18,

19]. The mode of tumor growth, the low mitotic index, the polyclonality of lymphoid markers and the negativity of CD34 usually remove most of these diagnoses. Other differential diagnoses are desmoid fibromatosis, angiomyofibroblastoma, fibrosarcoma, leiomyoma, and malignant fibrous histiocytoma. [18, 19]

The recurrence rate varies significantly based on tumor location, with lower rates in pulmonary IMTs (< 2%) compared to extrapulmonary sites, particularly those associated with abdominopelvic locations, multinodular masses, or incomplete resection [

20]. Vigilant post-surgical monitoring is crucial due to the potential for recurrence, which can occur years after initial treatment [

9]. Metastasis appears more likely in cases lacking ALK reactivity [

7].

4. Conclusion

In summary, IMT poses challenges in both diagnosis and treatment due to its diverse presentation and potential for aggressive behavior. Understanding its histopathological and genetic characteristics is essential for accurate diagnosis and optimal management decisions, ensuring favorable outcomes for patients.

Inflammatory myofibroblastic tumor is an uncommon lung tumor that rarely affects adults. Due to non-specific symptoms and imaging features, the diagnosis is challenging. Treatment of IMT involves complete resection and follows a good prognosis in majority of cases; nonetheless, long-term follow-up is crucial as IMT can recur. Consequently, diagnosis of IMT should be considered in the list of differential diagnoses in young patients presenting with lung nodules or masses.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.A., B.H., and W.S.; writing—original draft preparation, M.A., B.H., A.A, and W.S.; writing—review and editing, M.A., B.H., A.A., S.M., and K.A., supervision: M.A., W.S., S.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethical review and approval were waived for this case report: due to the nature of this article (case report).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from the patient involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Available upon reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Surabhi VR, Chua S, Patel RP, Takahashi N, Lalwani N, Prasad SR. Inflammatory Myofibroblastic Tumors: Current Update. Radiol Clin North Am. 2016 May;54(3):553-63. Epub 2016 Mar 12. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coffin CM, Hornick JL, Fletcher CD. Inflammatory myofibroblastic tumor: comparison of clinicopathologic, histologic, and immunohistochemical features including ALK expression in atypical and aggressive cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 2007 Apr;31(4):509-20. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bahadori M, Liebow AA. Plasma cell granulomas of the lung. Cancer. 1973 Jan;31(1):191-208. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Siminovich M, Galluzzo L, López J, Lubieniecki F, de Dávila MT. Inflammatory myofibroblastic tumor of the lung in children: anaplastic lymphoma kinase (ALK) expression and clinico-pathological correlation. Pediatr Dev Pathol. 2012 May-Jun;15(3):179-86. Epub 2012 Jan 26. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spencer H. The pulmonary plasma cell/histiocytoma complex. Histopathology. 1984 Nov;8(6):903-16. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matsubara O, Tan-Liu NS, Kenney RM, Mark EJ. Inflammatory pseudotumors of the lung: progression from organizing pneumonia to fibrous histiocytoma or to plasma cell granuloma in 32 cases. Hum Pathol. 1988 Jul;19(7):807-14. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brunn, H. (1939). "TWO INTERESTING BENIGN LUNG TUMORS OF CONTRADICTORY HISTOPATHOLOGY: Remarks on the Necessity for Maintaining the Chest Tumor Registry." Journal of Thoracic Surgery 9(2): 119-131.

- Demirhan O, Ozkara S, Yaman M, Kaynak K. A rare benign tumor of the lung: Inflammatory myofibroblastic tumor - Case report. Respir Med Case Rep. 2013 Feb 4;8:32-5. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Braham Y, Migaou A, Njima M, Achour A, Ben Saad A, Cheikh Mhamed S, Fahem N, Rouatbi N, Joobeur S. Inflammatory myofibroblastic tumor of the lung: A rare entity. Respir Med Case Rep. 2020 Nov 11;31:101287. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Haldar S, Datta S, Hossain MZ, Chakrabarty U, Pal M, Dasbaksi K, Saha S, Khurram M, Mukhopadhyay D. Inflammatory myofibroblastic tumor of lung in an adult female-a rare case. Indian J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2019 Jan;35(1):85-88. Epub 2018 Aug 16. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- UMIKER WO, IVERSON L. Postinflammatory tumors of the lung; report of four cases simulating xanthoma, fibroma, or plasma cell tumor. J Thorac Surg. 1954 Jul;28(1):55-63. [PubMed]

- Kuipers ME, Dik H, Willems LNA, Hoppe BPC. Inflammatory myofibroblastic tumor of the lung: A rare endobronchial mass. Respir Med Case Rep. 2020 Nov 10;31:101285. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Sachdev R, Mohapatra I, Goel S, Ahlawat K, Sharma N. Core Biopsy Diagnosis of ALK Positive Inflammatory Myofibroblastic Tumor of Lung: An Interesting Case. Turk Patoloji Derg. 2020;36(2):173- 177. English. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ekinci GH, Haciomeroglu O, Sen AC, Alpay L, Guney PA, Yilmaz A. Inflammatory Myofibroblastic Tumor of the Lung. J Coll Physicians Surg Pak. 2016 Apr;26(4):331-3. [PubMed]

- Patnana M, Sevrukov AB, Elsayes KM, et al. Inflammatory pseudotumor: the great mimicker. AJR Am J Roentgenol 2012;198:W217–27. [CrossRef]

- Agrons GA, Rosado-de-Christenson ML, Kirejczyk WM, Conran RM, Stocker JT. Pulmonary inflammatory pseudotumor: radiologic features. Radiology. 1998 Feb;206(2):511-8. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parker NC, Singanallur P, Faiek S, Gao J, White P. Inflammatory Myofibroblastic Tumor After Receiving Treatment for Non-small Cell Carcinoma. Cureus. 2024 Apr 30;16(4):e59359. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Pinilla I, Herrero Y, Torres MI, Nistal M, Pardo M. Tumor inflamatorio miofibroblástico pulmonar [Myofibroblastic inflammatory tumor of the lung]. Radiologia. 2007 Jan-Feb;49(1):53-5. Spanish. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang Y, Dong ZJ, Zhi XY, Liu L, Hu M. Inflammatory myofibroblastic tumor in lung with osteopulmonary arthropathy. Chin Med J (Engl). 2009 Dec 20;122(24):3094-6. [PubMed]

- Na YS, Park SG. Inflammatory myofibroblastic tumor of the pleura with adjacent chest wall invasion and metastasis to the kidney: a case report. J Med Case Rep. 2018 Sep 9;12(1):253. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).