1. Introduction

In today's digitally dominated world, screen time has become an integral part of our lives, particularly for students in the aftermath of the COVID-19 pandemic. The widespread practice of binge-watching, involving the consumption of numerous episodes or short films in one sitting, has surged in popularity, propelled by the evolution of streaming services and the easy accessibility of online content. However, the excessive screen time associated with binge-watching poses significant health risks, impacting both adults and children. Issues such as obesity, sleep disturbances, chronic neck and back pain, depression, anxiety, and even thinning of the brain cortex are recognized consequences. Despite extensive research into the sociological and psychological impacts, an aspect that has received insufficient attention is the environmental impact of binge-watching. The Shift Project, a French think tank, uncovered a concerning statistic: watching a half-hour show can result in 1.6 kilograms of carbon dioxide equivalent, akin to driving 3.9 miles ("Half-hour of," 2019). The emissions from online video streaming alone last year were equivalent to those of Spain, with the potential to double in the next six years. This carbon footprint is categorized into two primary components: internet bandwidth usage, encompassing activities like web browsing and streaming services, and the manufacturing and use of digital devices such as smartphones, tablets, computers, and laptops (Fransen, 2019). The internet, functioning as a global network of servers and data centers, demands substantial energy and water resources, contributing to a growing carbon footprint. Simultaneously, the manufacturing and transportation of digital products add to this environmental burden through emissions from mining and shipping processes. These phenomena collectively pose a significant threat to our planet by contributing to global warming. Recognizing the urgency of the situation, it is imperative to shed light on the environmental sustainability aspect of binge-watching habits. This involves understanding the conceptual dimensions and awareness levels of students regarding their binge-watching behaviors, with a specific emphasis on their knowledge of the carbon emissions associated with electronic devices. Such understanding is crucial not only for promoting responsible digital consumption but also for actively contributing to broader conversations on sustainable living. The escalating energy consumption and electronic waste generated by the booming demand for internet streaming services have raised profound concerns about environmental sustainability and carbon emissions. The intricate process involved in creating, transmitting, and utilizing digital content contributes significantly to the environmental footprint. The environmental repercussions of binge-watching are further compounded by the energy consumption of electronic devices, as well as their production and disposal.

1.1. Literature Review

In a comprehensive exploration of binge-watching behaviors among students, Moore (2015) examined the relationship between students' academic disciplines, gender, and online streaming preferences. Particularly among students in the College of Engineering and Sciences, the results highlighted a significant gender disparity in preferred genres. Furthermore, females tended to watch more episodes for longer durations than males, demonstrating notable individual variations in viewing habits, according to Seifert's (2019) analysis of gender differences in video-on-demand watching patterns. Studies conducted by Panda and Pandey (2017) and Starosta et al. (2019) provided additional insights into the reasons college students binge-watch, primarily due to the satisfaction these platforms provide. The findings showed that binge-watching led to students feeling unsatisfied, which increased their propensity to stay engaged. Furthermore, research investigated the complex variables that influence binge-watching, including friends, family, and entertainment. Students who engaged in this behavior reported negative effects on their academic performance, such as missing school, receiving failing grades, and experiencing psychological and physical effects. Binge-watching was found to be influenced by various factors, including social capital, procrastination, addiction, entertainment value, and content preferences. The effects extended beyond the individual, impacting relationships, education, and college life. Additionally, studies challenged the notion that binge-watching should only be understood as an addictive disorder, highlighting the difference between high engagement and problematic involvement (Dhanuka & Bohra, 2019; Flayelle et al., 2019; Gangadharbatla et al., 2019; Starosta & Izydorczyk, 2020). The effect of COVID-19 on environmentally friendly behavior gained prominence in light of the rapidly changing digital environment. According to Gnanasekaran et al. study from 2021, participants had a worryingly low awareness of their digital carbon footprints. The study pointed to several contributing factors, including a lack of understanding, a dearth of public information, and a lack of social awareness. In addition to offering complex insights into the motivations and behaviors behind binge-watching, this body of research highlights the importance of having a comprehensive grasp of how digital technology affects sustainable practices, especially in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic. Prioritizing the environmental impact of digital applications while pushing for high-quality user experiences aligns with the United Nations' commitment to sustainable development and environmental responsibility. As stressed by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC, 2021), there is an urgent need to significantly reduce carbon dioxide and greenhouse gas emissions. This directly supports Sustainable Development Goal 13, "climate action." Literature increasingly focuses on the negative effects of unsustainable viewing behaviors like binge-watching, multi-watching, and media multitasking in the context of rising consumption (Widdicks et al., 2019). Projections show a sharp increase in energy needs and greenhouse gas emissions related to digital services and infrastructure, especially in information and communications technology (ICT), consistent with recent studies (Belkhir et al., 2017; Morley et al., 2018; Obringer et al., 2021).

Preist et al. (2016) report that projections indicate that ICT may have an unsustainable carbon footprint due to variables such as growing data center energy demands and greater data traffic. The environmental effects of popular cloud-based services, especially video streaming, have been the subject of recent studies that have examined the interconnected infrastructure elements, including data centers, transport networks, and end devices (Marks & Przedpełski, 2022; Preist et al., 2014; Preist et al., 2016; Suski et al., 2020).

Furthermore, rebound effects, such as increased data traffic, electricity demand, and user expectations for quality of experience, availability, and connection, may result from increasing usage and unsustainable user practices (De, 2023). According to Juul et al. (2021), even seemingly harmless behaviors like "casual scrolling" contribute significantly to CO2 emissions, equivalent to driving 485 km. A study in Michigan, USA, investigating the environmental effects of watching movies found that even though digital distribution performed better than physical distribution overall, digital streaming still resulted in higher emissions (Nair, 2019). It is essential that we acknowledge the environmental effects of our digital lives as we navigate the digital landscape and actively strive toward sustainable behaviors for a more environmentally friendly future. However, environmental assessment tools revealed that the ICT industry, particularly video streaming, significantly contributes to CO2 emissions. Interdisciplinary cooperation is required to make streaming more sustainable. Thus far, in this context, several studies have integrated life cycle assessments and online surveys to predict different usage periods and gauge variables such as climate intensity. These studies have highlighted the environmental impact of streaming media, which is thought to account for 1% of global greenhouse gas emissions. They also addressed the adverse effects of 5G technology's higher electromagnetic frequencies. Researchers proposed best practices in education to inform students about these implications, as well as steps that consumers and media creators can take to mitigate this hazard (Marks & Przedpełski, 2020; Page, 2020; Suski et al., 2020). According to Hazas and Nathan (2017), Preist et al. (2016), Widdicks et al. (2019), and other researchers, there is a growing body of evidence supporting the need for a paradigm shift toward a more sustainable and human-centered approach, recognizing the increased influence of digital consumption and growing data demands on individuals, populations, and the environment. This underscores the close relationship between consumer behavior, user experience quality, and energy use. The ICT industry, especially video streaming, has a significant impact on CO2 emissions, as shown by environmental assessment tools. Understanding the importance of improving streaming sustainability, interdisciplinary cooperation becomes essential. Recent studies have combined life cycle assessments with online questionnaires to simulate consumption phases and analyze variables like climate intensity. The results indicate that streaming media accounts for about 1% of global greenhouse gas emissions. Notably, these studies also emphasized the adverse effects of 5G technology's higher electromagnetic frequencies. Researchers advocating for sustainable streaming practices have presented actionable advice for consumers and media creators to reduce environmental risks. Additionally, incorporating best practices into education is prioritized to increase awareness of the environmental impact of streaming (Marks & Przedpełski, 2020; Suski et al., 2020). These findings collectively present a strong case for a paradigm shift towards a more human-centered and sustainable approach, considering the broader effects of digital consumption and growing data demands on people, society, and the environment (Hazas & Nathan, 2017; Preist et al., 2016; Widdicks et al., 2019). This synthesis demonstrates the close relationship between energy consumption, user experience quality, and consumer behavior, emphasizing the necessity of making thoughtful decisions and collaborating to promote a more environmentally responsible and sustainable approach to digital consumption.

1.2. Rational of the Study

Current research rarely explores the depth of students' understanding regarding the environmental impact of prolonged screen time, nor does it assess their awareness of the carbon emissions resulting from the production and usage of electronic devices during extended screen time. Additionally, there is a significant lack of focus on binge-watching habits and behaviors among students, including the factors that contribute to the persistence of these habits. A critical gap in the existing literature pertains to the environmental repercussions of the widespread phenomenon of binge-watching among students. While considerable research has examined the psychological and social aspects of screen time, there is a distinct absence of studies addressing the ecological emissions linked to prolonged and frequent screen use, particularly in the context of binge-watching. This gap raises several pertinent questions: What is the level of understanding among students regarding the environmental impact of prolonged screen time, especially concerning the electronic usage of devices during binge-watching sessions? How aware are students of the environmental consequences of carbon emissions associated with the production and usage of electronic devices for extended screen time? What are the binge-watching habits and behaviors reported by students? What factors influence prolonged screen time, such as content preferences, duration, and frequency, and how do these patterns contribute to environmental impact? Finally, what potential interventions and educational initiatives could effectively reduce the environmental impact of binge-watching among students? In an era marked by advancing technology and the surging popularity of streaming services, understanding the environmental consequences of these behaviors becomes imperative. This study aims to bridge this research gap by meticulously examining the energy consumption, electronic waste generation, and carbon emissions associated with extended screen time. It seeks to highlight an often-overlooked aspect of sustainability in the digital age while assessing the prevailing awareness levels among students. The insights garnered from this research will be instrumental in developing well-informed strategies to promote sustainable screen habits among students, thereby mitigating the environmental impact of binge-watching. By doing so, the study endeavors to contribute significantly to the ongoing discourse on responsible digital consumption and environmental stewardship.

1.3. Statement of the Problem

This study, titled "Reflections of Adult Learners on Binge-Watching and its Detrimental Impact on the Environment in West Bengal, India" delves into a crucial void within existing literature concerning the environmental impacts of widespread binge-watching. While considerable research has delved into the psychological and social dimensions of screen time, there exists a significant gap in understanding the ecological ramifications of prolonged and frequent screen usage, particularly within the realm of binge-watching. This research seeks to bridge this gap by meticulously examining energy consumption, electronic waste generation, and carbon emissions linked with extended screen time, thereby illuminating an often-overlooked facet of sustainability in the digital era.

1.4. Operational Definition

Screen Time Sustainability: refers to the responsible and balanced use of screen time (the amount of time spent using a device with a screen, such as a smartphone, computer, television, or video game console) over the long term, considering the potential physical, mental, social, and environmental impacts. It involves finding a healthy balance between benefits and drawbacks, ensuring screen time doesn't compromise overall well-being or have negative consequences.

Binge Watching Habit: is the act of consuming multiple episodes of a television series or a significant amount of content from a streaming service in a single sitting or over a short period, often completing an entire season or a substantial portion of a series in one go.

Awareness: is the state of being conscious, cognizant, or knowledgeable about something, encompassing sensory, self-awareness, social, and environmental awareness, and can manifest in various forms.

Carbon Emissions: refer to the release of carbon compounds into the atmosphere, primarily in the form of carbon dioxide (CO2) and other greenhouse gases, are a result of human activities like burning fossil fuels, industrial processes, deforestation, and certain agricultural practices. These emissions contribute to the enhanced greenhouse impact, trapping heat in the Earth's atmosphere and causing global warming and climate change.

1.5. Objectives of the Study

The objectives of the present study were:

To assess the students' comprehension of the environmental impacts of prolonged screen time by analysing their electronic device usage during binge-watching sessions.

To investigate the level of awareness among students regarding the environmental consequences stemming from carbon emissions linked to the production and utilization of electronic devices during extended screen time.

To explore and analyse the reported binge-watching habits and behaviors exhibited by students.

To analyse students' understanding of how electronic devices impact on the environment, including their awareness of carbon emissions during extended screen use.

To explore students' understanding of the environmental impact, their awareness of carbon emissions by using electronic devices during extended screen use, and their habits and behaviors related to binge-watching.

To identify and examine the factors that influence prolonged screen time, including content preferences, duration, and frequency, to understand their roles in contributing to environmental impact patterns.

To explore potential interventions and educational initiatives aimed at reducing the environmental impact caused by binge-watching habits and behaviour among students.

1.6. Hypotheses

The researchers had formulated following hypotheses-

There would be a notable gender disparity regarding the depth of understanding of the environmental impact resulting from binge-watching sessions among students.

There would not be a significant difference in the awareness of male and female students regarding the environmental impact of extended screen time on carbon emissions.

Gender differences in binge-watching habits and behavior among students would be significant.

There would be a significant level of awareness among students regarding carbon emissions from electronic devices during extended screen time and their overall understanding of environmental impact related to technology usage.

Significant differences and relationship would be there among students' understanding of the environmental impact, their awareness of carbon emissions from electronic devices during extended screen time, and their habits and behaviors related to binge-watching.

1.7. Research Questions

What are learners' habits regarding screen time, and what factors influence prolonged usage, contributing to environmental impact?

What potential interventions and educational initiatives exist to mitigate the environmental impact of binge-watching?

2. Methodology

2.1. Design

In this study, researchers employed a descriptive mixed-method design. This approach combines qualitative and quantitative research approaches to give a thorough grasp of the study subject. In terms of this combined methodology, the study seeks to highlight the advantages of both qualitative and quantitative data by providing a more comprehensive and refined view than could be obtained from either approach alone. Finding patterns, trends, and correlations through the collection and analysis of numerical data is the quantitative component. This data makes it possible to extrapolate research findings to a broader population and gives a comprehensive overview of the study topic (Creswell & Clark, 2023; Schoonenboom & Johnson, 2017). Conversely, the qualitative aspect concentrates on obtaining comprehensive, narrative data that illuminates the underlying beliefs, attitudes, and intentions underpinning the trends that are being seen. This is accomplished by using techniques that allow for a thorough examination of participants' experiences and viewpoints, such as focus groups, open-ended surveys, and interviews. By combining these two strategies into a descriptive mixed-method design, data triangulation is made possible, which improves the validity and consistency of the study's conclusions (Creswell & Clark, 2017; Dejonckheere et al., 2019). It guarantees that the investigation encompasses the entire range and profundity of the research subject, offering a comprehensive, intricate, and diverse comprehension that shapes conclusions and suggestions.

2.2. Sample

In West Bengal, India, students from a variety of government and private institutions, universities, and institutes made up the sample for this study. In order to guarantee a representative and varied sample, students were chosen from a variety of geographic locations, encompassing urban, suburban, and rural areas. With this technique, we hope to capture a broad range of experiences and viewpoints that represent the state's different socioeconomic and cultural backgrounds (Jha et al., 2020). There were 525 participants in all, 150 of them were male students and 375 of them were female. This gender distribution provides insight on how male and female students may have had different experiences and perspectives. In order to provide a thorough insight of the student population in the Indian state of West Bengal, the survey included students from a variety of educational institutions and geographic regions. The assessment of potential variations in experiences and results based on the type of institution attended was made possible by the inclusion of students from both government and private institutions. As a result, the research had a strong basis thanks to the varied and well-chosen sample, which made it easier to provide findings that were both pertinent and widely applicable.

2.3. Tools

The researchers utilized self-designed standardized questionnaires to collect data. These tools consisted of thirty closed-ended items (ten per variable) and six open-ended items aimed at measuring the participants' understanding and awareness of the environmental impact of prolonged screen time and carbon emissions across genders. The assessment focused on electronic device usage during binge-watching sessions using a 'yes-no' question format. Additionally, the researchers evaluated binge-watching habits through ten 'yes-no' questions. To identify the most influential factors for binge-watching habits, the researchers employed ten questions based on a five-point Likert scale, ranging from 'not at all influential (1)' to 'extremely influential (5)' (Vagias, 2006; Zakharenko, 2023). The six open-ended items were designed to explore potential interventions, binge-watching factors, and educational initiatives to mitigate the environmental impact of binge-watching. Regarding the scoring of the three variables—understanding of the environmental impact, awareness of environmental consequences, and binge-watching habits and behaviors each correct response was assigned a score of five, while incorrect responses were scored as one. Consequently, the total scores for each questionnaire ranged from 10 to 50. These scores were further stratified into three percentage levels (Low, Moderate, and High), with each level divided into approximately 16 intervals. To ensure the standardization of the questionnaires evaluating understanding, awareness, habits, behaviors, and influential factors related to binge-watching, a meticulous approach emphasizing face validity was adopted. The questionnaires assessing understanding and awareness were administered to 32 participants, yielding Kuder-Richardson reliability coefficients of 0.76 and 0.81, respectively. For habits and behavior, Cronbach's alpha reliability was found to be 0.78.

2.4. Procedure of Data Collection

The data collection procedure for this study involved the distribution of survey questionnaires to students from various private and government colleges, universities, and institutes located in rural, suburban, and urban areas of West Bengal, India. To reach a broad and diverse student population, the researchers employed physical and digital communication channels. So far, the physical mode is concerned, researchers administered the questionnaires by one to one seating followed by sending the survey questionnaires via email and WhatsApp. This method ensured efficient and widespread dissemination of the survey tools. Before administering physically and sending out the questionnaires, the researchers provided detailed information to all potential participants about the nature of the tool, the purpose of the study, and the expected time commitment for completing the survey. This information was conveyed to ensure that participants were well informed and could make an educated decision about their involvement in the study. However, through Google Forms, a convenient online platform was used for collecting and organizing responses. Participants were given clear instructions and a timeline for submission to facilitate timely and accurate data collection (Bhalerao, 2015; Rayhan et al., 2013). Upon the conclusion of the data collection period, a total of 525 (150 male and 375 female) responses had been received in the both modes. So far, these responses are concerned we have found a distinct gender gap in our data, likely caused by the amalgamation of online and offline information. However, we emphasized the importance of obtaining consent from all participants as an ethical practice. Instead of seeking formal ethical approval from an institutional review board, the study relied on obtaining explicit consent from each participant. This consent process ensured that all participants voluntarily agreed to take part in the research, understanding their rights and the nature of their participation. This approach underscored the researchers' commitment to ethical standards and respect for the participants' autonomy.

2.5. Statistical and Nonstatistical Techniques

The quantitative data from participant responses were calculated and analyzed using various statistical methods, including frequencies, percentages, t-tests, ANOVA, and multiple correlation analyses. These techniques allowed for a comprehensive examination of the data, providing insights into the distribution, relationships, and differences within the dataset (Jennings & Cribbie, 2016; Kumar & Chong, 2018; Liu & Wang, 2021).

Similarly, the qualitative data was analyzed through a systematic examination of non-numeric data to identify patterns, themes, and meanings. The answers to the research questions were analyzed through a thorough coding process. This process involved assigning keywords and phrases to data segments to categorize them. To develop themes, related codes were grouped into categories, allowing the identification of patterns and main concepts emerging from the data. Finally, these themes were analyzed to understand their deeper meanings and implications (Brady, 2015; Naeem et al., 2023). This analysis also interpreted how the themes answered the research questions related to existing research.

2.6. Delimitation of the Study

The study was delimited to a sample of 525 students from various private and government colleges, universities, and institutes across rural, suburban, and urban areas of West Bengal, India. This diverse sample aimed to capture a comprehensive representation of the student population in the region.

3. Result

3.1. Hypothesis 1

The results for hypothesis H1, which examined whether there is a significant gender difference in understanding the environmental impact of binge-watching sessions among students, were calculated by using t test. Similarly, the scores from male and female students regarding their level of understanding of these environmental impacts were also calculated using percentage.

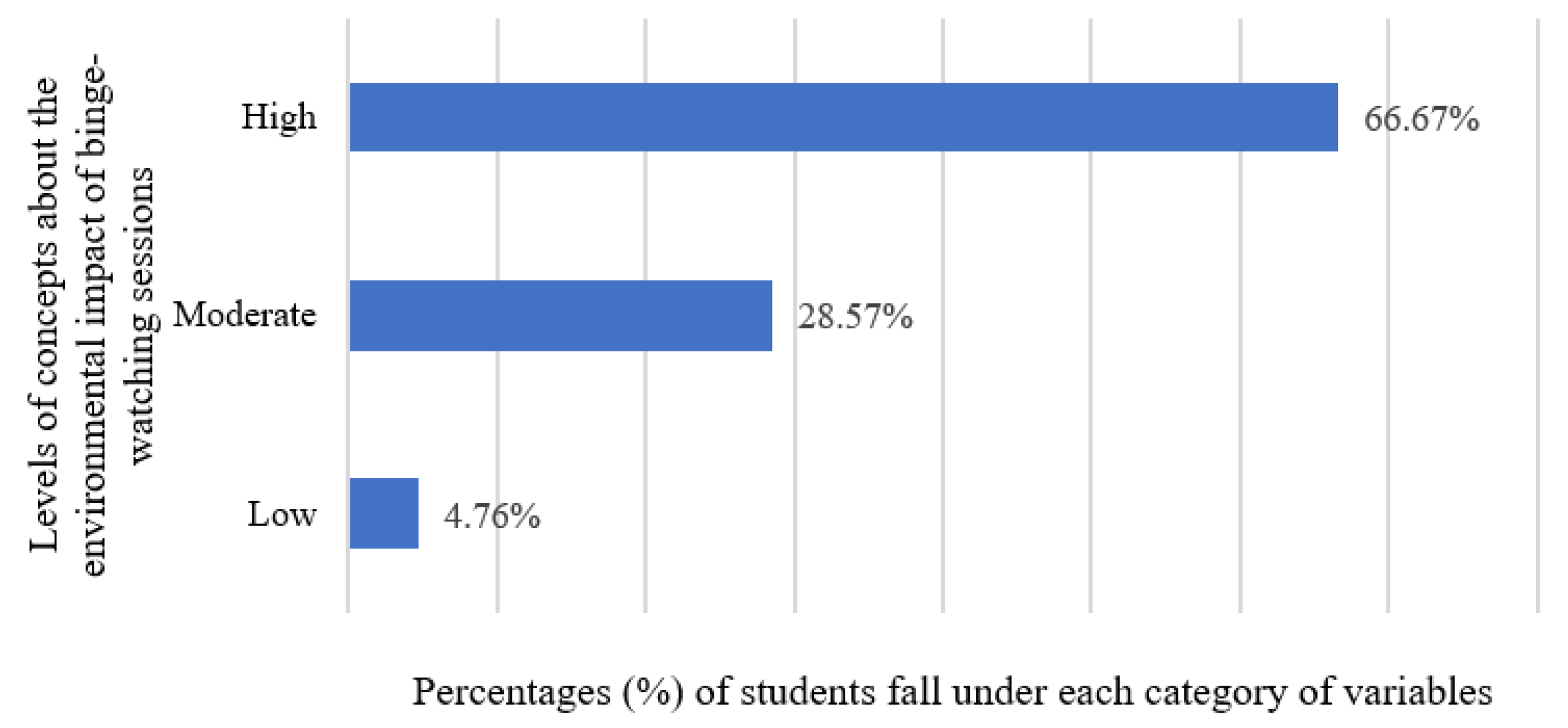

The data in

Table 1 shows 525 students, the distribution of students’ understanding of the environmental impact of binge-watching sessions is categorized into three levels: low, moderate, and high. The findings reveal that a small minority of students, 4.76%, have a low level of awareness regarding the environmental consequences of binge-watching. A larger portion, 28.57%, demonstrate a moderate understanding of these impact. The majority of students, 66.67%, exhibit a high level of awareness about the environmental impacts associated with binge-watching sessions. This distribution indicates that most students are well-informed about the potential environmental implications of their media consumption habits.

The above graphical representation

Figure 1 indicates that the majority of students (66.67%) have a high level of awareness about the environmental impact of binge-watching, with 28.57% having a moderate understanding. A small percentage (4.76%) has limited awareness, with only a small fraction (4.76%) falling under the "Low" level. This could be due to increased awareness campaigns, educational programs, or societal shifts. However, a moderate percentage suggests room for improvement in education.

The

Table 2 is reflecting the comparison of level of understanding of the environmental impact of binge-watching between female and male students and their significant differences. Female students (N=375) have a mean score (M

1) of 8.53 with a standard deviation (SD

1) of 1.85 and a standard error of the mean (SE

M1) of 0.21. Male students (N=150) have a lower mean score (M

2) of 6.83 with a standard deviation (SD

2) of 2.11 and a standard error of the mean (SE

M2) of 0.38. The standard error of the difference (SE

D) between the two groups is 0.41. With 523 degrees of freedom (

df), the t-value is calculated to be 4.08, and the

p-value is 0.000089, (<.0001) indicating that the difference in the level of understanding between female and male students is statistically significant.

3.2. Hypothesis 2

The result of formulated hypothesis (H2) that there is no significant difference in awareness about the environmental impact of extended screen time on carbon emissions between male and female students was tested. The awareness scores from male and female students were statistically analyzed using a t-test. Additionally, their awareness levels were calculated and compared using percentages.

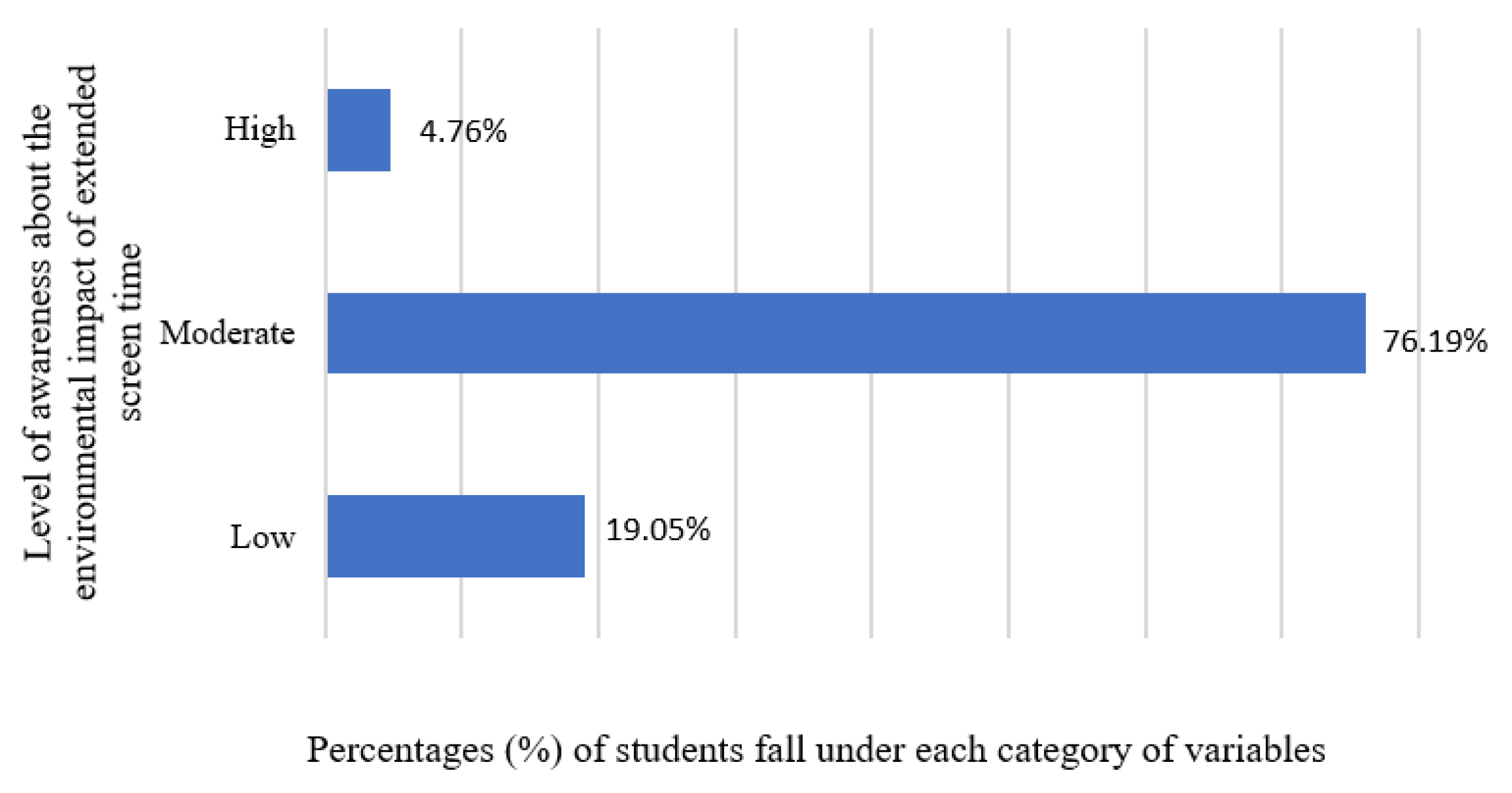

The

Table 3 reveals that 76.19% of students have moderate awareness about the environmental impact of extended screen time in relation to carbon emission. However, 19.05% of students fall under the "Low" category, indicating a lower level of awareness. Only 4.76% fall under the "High" category, indicating a small fraction of students have a high level of awareness. The data suggests that while a significant proportion of students have moderate awareness, there is room for improvement. Addressing lower awareness levels and engaging students through educational strategies can help foster a better understanding of the environmental consequences of extended screen time.

According to

Figure 2, 76.19% of students have a moderate understanding of how prolonged screen usage affects carbon emissions and the environment. Only 4.76% have a high level of awareness, compared to 19.05% who have a poor one. Although a sizable percentage of pupils exhibit intermediate awareness, the data indicates that there is still opportunity for development of environmental awareness.

As shown the

Table 4, depicts the gender difference in awareness about the environmental impact of extended screen time on carbon emissions between the group of female male and male students. Here, female students (N=375) have a mean score (M

1) of 5.06 with a standard deviation (SD

1) of 1.69 and a standard error of the mean (SE

M1) of 0.19. Male students (N=150) have a slightly higher mean score (M

2) of 5.16 with a standard deviation (SD

2) of 1.34 and a standard error of the mean (SE

M2) of 0.24. The standard error of the difference (SE

D) between the two groups is 0.34. With 523 degrees of freedom (

df), the

t-value is calculated to be 0.28, and the

p-value is 0.77, indicating that the difference in the level of understanding between female and male students is statistically not significant. Therefore, there is no significant difference between the group of female and male students in terms of their awareness about the environmental impact of extended screen time on carbon emissions.

3.3. Hypothesis 3

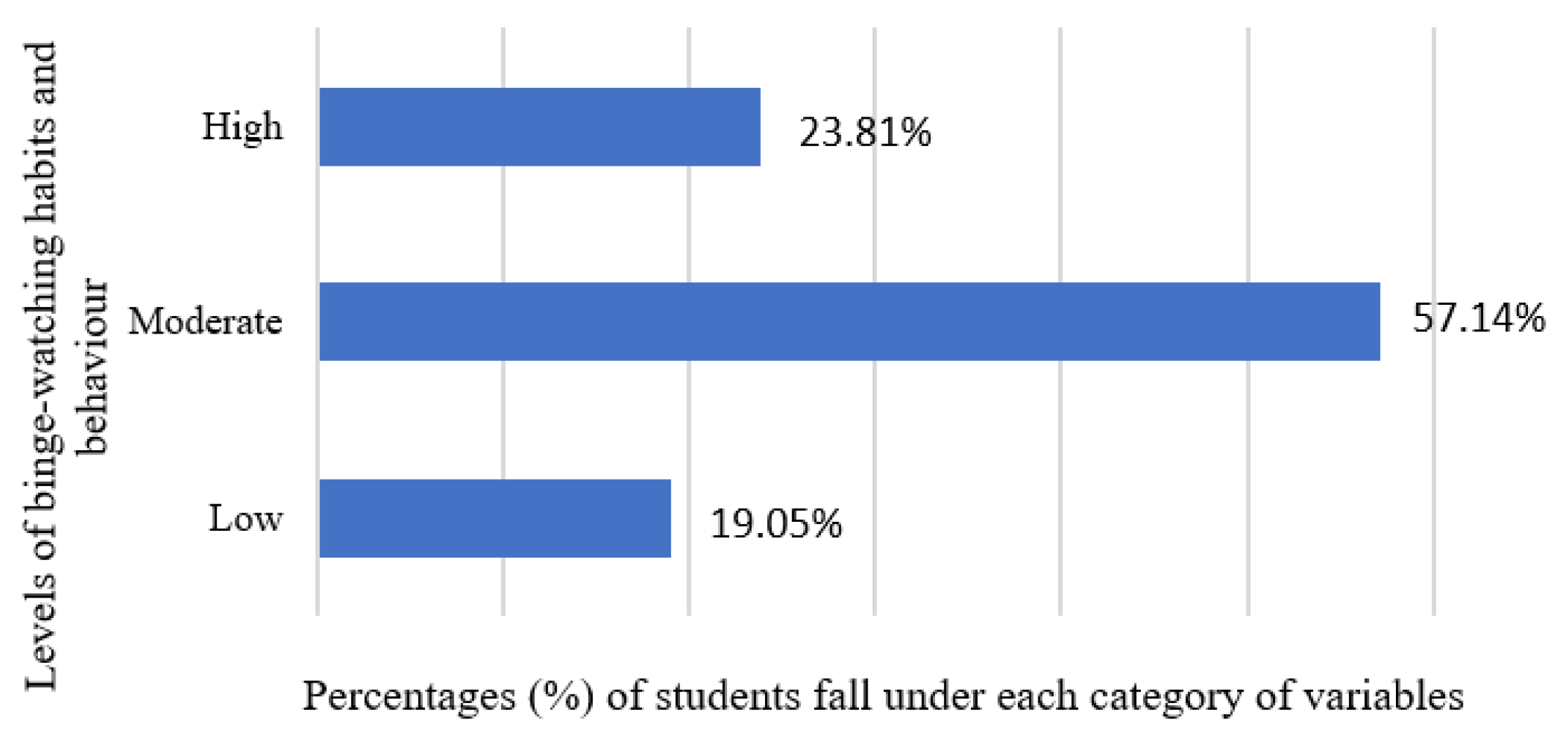

The results for hypothesis H3, which examined whether there is a significant gender difference related to binge-watching habits and behaviour among the students, the obtained scores were calculated by using t test. Similarly, the scores from male and female students regarding their level of binge-watching habits and behaviour were also calculated by using percentage.

Table 5 shows the binge-watching habits and behavior of 525 students, with percentages assigned to each category. A significant portion of students, around 57.14%, exhibit moderate binge-watching habits, suggesting it is a common behavior. About 23.81% of students fall into the high binge-watching category, indicating a substantial but not the majority of students have high levels of engagement. As a significant percentage falls into the moderate category, indicating binge-watching is a prevalent behavior. However, the distribution across the three levels indicates diversity in binge-watching habits among the surveyed students.

Figure 3 shows binge-watching habits among 525 students, with a majority of 57.14% engaging in moderate binge-watching. A small percentage, 23.81%, fall into the high binge-watching category. Moderate binge-watching is prevalent among the majority, while high binge-watching is not the dominant category.

Table 6 indicates the results of the statistical analysis unveil a compelling narrative regarding the binge-watching habits and behaviors of male and female students. Female students (N=375) have a mean score (M

1) of 5.80 with a standard deviation (SD

1) of 2.34 and a standard error of the mean (SE

M1) of 0.27. Male students (N=150) have a lower mean score (M

2) of 4.16 with a standard deviation (SD

2) of 2.54 and a standard error of the mean (SE

M2) of 0.46. The standard error of the difference (SE

D) between the two groups is 0.51. With 523 degrees of freedom (

df), the t-value is calculated to be 3.16, and the

p-value is 0.0020 (

p<.0001), indicating that the difference in the level of binge-watching habits and behaviour between the group of female male and male students is statistically significant.

3.4. Hypothesis 4

The results for hypothesis H4, which examined student awareness of carbon emissions from electronic devices during extended screen time and their overall understanding of the environmental impact of technology usage, were statistically analyzed using a t-test to determine the significance of their awareness and understanding.

Table 7 presents the statistical result comparing students' understanding of environmental impact related to technology usage and their awareness of carbon emissions from electronic devices during extended screen time. For understanding environmental impact (N=525), the mean score (M

1) is 8.05, with a standard deviation (SD

1) of 2.09 and a standard error (SE

M1) of 0.20. In contrast, the awareness of carbon emissions (N=525) has a lower mean score (M

2) of 5.10, with a standard deviation (SD

2) of 1.61 and a standard error (SE

M2) of 0.16. The standard error of the difference (SE

D) is 0.22. With 524 degrees of freedom (

df), the

t-value is 12.98, and the

p-value is <0.0001, indicating a highly significant difference between the two groups.

3.5. Hypothesis 5

The results for hypothesis H5, which investigated the significant differences and relationships among students' understanding of environmental impact, awareness of carbon emissions from electronic devices during extended screen time, and their binge-watching habits and behaviors, were analyzed. The scores obtained from the research participants were statistically treated using Multiple Correlation and ANOVA.

The

Table 8 examines the relationships between students' understanding of the environmental impact of technology use, their awareness of carbon emissions from electronic devices during extended screen time, and their binge-watching habits. The result reveals a significant but modest positive correlation between these variables. Specifically, students' understanding of the environmental impact of technology use is positively correlated with both their awareness of carbon emissions (

r = 0.23,

p < .001) and their binge-watching habits (

r = 0.30,

p < .001). Additionally, there is a positive correlation between awareness of carbon emissions and binge-watching behavior (

r = 0.26,

p < .001). The overall coefficient of multiple correlation (

R) is 0.36, indicating a moderate combined impact of these variables.

The

Table 9 is reflecting the students' comprehension of environmental impact in comparison to their awareness of carbon emissions and their binge-watching habits and behaviors are assessed using an

ANOVA analysis. A between-group sum of squares (SS) of 2824.60, degrees of freedom (

df) of 2, mean square (MS) of 1412.30,

F value of 320.10, and a

p value of 0 indicated a significant difference between the groups in the results. With 1572

df and an MS of 4.41, the within-group SS was 6935.71, resulting in a corrected total SS of 9760.32 with 1574

df and an overall MS of 6.20.

This graph (

Figure 4) depicts the

F distribution in which the black line represents the probability density function of the F distribution. This shows the likelihood of different F values occurring. The green shaded area represents the acceptance region, where the null hypothesis is not rejected. This indicates that the observed

F value falls within the range where any deviations from the expected outcome can be attributed to random chance rather than a significant effect. Whereas, the red shaded area to the right represents the rejection region (

α). This is the area where the F value is large enough to reject the null hypothesis, indicating that the observed variation is statistically significant and not likely due to chance.

3.6. Research Question 1

The qualitative analysis helps to draw the upshot of the formulated research question (RQ1) bearing three open ended items to analyse about the duration of digital screen usage, the type of content that appeals to the individuals, and whether they frequently watch a particular content, i.e., their habits of watching, and also explores factors influencing prolonged screen time, such as content preferences, duration, and frequency. The analysis also results research question (RQ2) bearing three open ended items to explore potential educational interventions to mitigate the environmental impacts of binge-watching among students.

From the

Table 10A we can revealed that the individuals exhibit a wide range of screen time habits, averaging between 4 to 10 hours daily. On college days, screen usage is higher, often between 6 to 10 hours, primarily due to online classes, homework, and social media. Screen time is utilized for various activities, including work, social media, entertainment, gaming, video watching, news, and staying connected with family and friends. Content preferences and activities suggest a blend of educational, social, and recreational uses, with the frequency and duration varying based on daily responsibilities and leisure activities.

The individuals exhibit diverse digital content preferences, including quick, entertaining videos on TikTok and Instagram, binge-watching series on Netflix and Amazon Prime, and enjoying educational videos and DIY tutorials on YouTube that is clearly reflection in the

Table 10B. Online gaming is popular, often accompanied by social media interaction. Many favor thrillers, suspense, and mystery content, while others prefer relaxing, chill, and animated content. There is also a notable interest in supernatural fiction and classic genres. Overall, their digital content consumption spans entertainment, education, gaming, and relaxation.

Table 10B.

Thematic analysis of the participant’s based on the given question. RQ1B. What kind of digital content appeals to you?

Table 10B.

Thematic analysis of the participant’s based on the given question. RQ1B. What kind of digital content appeals to you?

| Theme |

Summary |

Sample data as examples |

| Diversity of using digital content. |

The individual enjoys watching- TikTok/ Reels, Instagram, Netflix, Amazon Prime.

Educational videos, DIY tutorials.

Online games.

Prefers thrillers, suspense related content.

Relaxing content.

|

R10: “I’m really into TikTok and Instagram for quick, entertaining videos…...I mostly enjoy binge-watching series on Netflix and amazon prime.”

R11:"I love watching YouTube videos, especially educational channels and DIY tutorials…... I also spend a lot of time on social media and playing online games with friends.”

R 12: “Game…game only…YouTube…online streaming of game and shorts.”

R13: “Thriller…suspense.”

R14: “Mystery…thriller and social networking sites.”

Relaxing and Chill type content and Insta.”

R15: “Though classic attracts me most but I have fond of thiller-supense.”

R16: “Supper natural and fiction…but roaming around the social sites is more relaxing, animated movie.”

R17: “Thiller. / Social media even I like cartoons and animated movie still.”

R18: “Reel …. variety of contents. All are cool and relaxing.”

|

The

Table 10C is showing the propagation of binge-watching habits which is influenced by the nature of the program and time constraints. Individuals generally avoid repeats due to limited time, preferring to watch content that seems interesting or has nostalgic value. Variety in content and platforms is highly attractive, and active participation in social networking sites is deemed necessary. Co-watching occurs occasionally, often when someone has missed a particular show. Repetition of content is generally limited to social networking sites due to the abundance of available content and time constraints.

Table 10C.

Thematic analysis of the participant’s based on the given question. RQ1C. Do you watch a particular type of content over and over again?

Table 10C.

Thematic analysis of the participant’s based on the given question. RQ1C. Do you watch a particular type of content over and over again?

| Theme |

Summary |

Sample data as examples |

| Propagation of binge watching habit depends on the nature of programme. |

Avoids repeats due to time constraints.

Enjoys variety sites and surfing on social networking sites.

Be a co-watching occasionally.

Active in Social networking sites is very necessary now a days. |

R 19: “I do very often. As I have time issues…want to watch specially those are seemed interesting.”

R 20: “I want to repeat but not get the time, But I really want to watch the movie that have nostalgic value. But right now, I will say ‘no’ as I do not repeat.”

R 21: “Usually not…. as variety attracts me most, as there are lots of content from different platform of my favourite genre.”

R22:” Usually not but only very occasions if anyone have missed that particular show then sometimes, I had to be co-watcher.”

R23: “Reptation only the social networking sites not get that much time.”

|

3.7. Research Question 2

The

Table 10D shows extended screen time which is influenced by a multidimensional set of factors. Limited leisure options, especially in less developed or isolated areas, lead individuals to turn to digital entertainment for lack of alternatives. The convenience of digital platforms, which offer everything from social interactions to educational resources in one place, further encourages screen use. Emotional release is another key factor, as many find solace in digital content during stressful or challenging times. Parental permissiveness also plays a role, with relaxed screen time limits enabling children to binge-watch. Social dynamics, such as maintaining relationships with family and friends, fear of missing out (FOMO), and habitual behaviors, contribute significantly to extended screen use. The vast array of available content creates an engaging and sometimes addictive web, making it difficult for users to disconnect. Overall, these factors combine to make prolonged screen time a prevalent aspect of modern life.

Table 10D.

Thematic analysis of the participant’s based on the given question. RQ2A. What are the other things keep you busy on the digital screen?

Table 10D.

Thematic analysis of the participant’s based on the given question. RQ2A. What are the other things keep you busy on the digital screen?

| Theme |

Summary |

Sample data as examples |

| Multidimensional Factors influencing prolong screen time. |

Prolonged Screen Time Influences.

Limited leisure options.

Digital convenience.

Emotional release.

Permissiveness of parents triggers children's binge-watching.

Motivations include family and friend relationships.

FOMO

Habits

Complex web of entertainment.

Social dynamics.

|

R24: “I have no other option so like to spend more time on my tab. There's just not much else for me to do around here, even not a play-ground or park. "

R25:" I end up spending most of my free time playing video games or watching movies because there's nothing else to do."

R26:"There’s not much to do in our small town, and most of my friends ar6 online anyway. So, we hang out on social media or play games together virtually."

R27:” I can't always afford to take paid classes of activities. Screen time becomes a convenient and cost-effective way to keep them entertained."

R28:"My area has limited options as its progress is slow. In the meantime, residents have been spending more time on their screens due to the lack of available alternatives."

R29: "With everything available online, it's just easier to use digital options for learning and entertainment. We easily can access educational apps, games, and videos all in one place.

R30: "It's so convenient to have everything on my phone. I can chat with friends, watch videos, and do my homework without needing to switch between different devices or locations."

R31: "I find it much easier to use my tablet for reading, watching shows, and even ordering groceries. It’s all in one place, and I don’t have to go out as much."

R32: "I can stay connected with friends and entertained without having to leave my room."

R33: "This shift to digital platforms is easiest and cheapest way now-a-days."

R 34: "It's a way for me to escape and calm down when I am loaded with emotional challenges."

R35: "find that watching my favourite shows or mobile browsing help me unwind and forget about my worries for a while."

R36: "When work gets really stressful, I like to relax by browsing social media or watching funny videos online. It’s a quick and easy way to lift my mood."

R37: "Old shows and movies from my childhood days make me happy and help me to cope my low mood."

R 38: "When I'm feeling down, chatting with friends online or watching uplifting content on YouTube helps me feel better. It's like a quick pick-me-up."

R 39: "Watching favourite show provides a much-needed emotional break from the daily stresses."

R 40: "I think parents are very lenient now-a-days, they allow their child to avail digital platform. It may because of the fact that they can get some peace and ‘me-time’ to handle household chores and work from home."

R 41:"My parents don't really set any limits on how much time I can spend watching shows. Sometimes children end up binge-watching entire seasons over the weekend."

R 42:"My parents are pretty relaxed about my screen time. They don't mind if I spend hours watching Netflix, as long as I get my homework done."

R 43: "Parents often let them for binge-watch or to use their tablets without much restriction to keep them busy."

R 44: "We have family movie nights where we all sit together and watch a series or a movie marathon. It's our way of bonding and spending quality time together."

R 45: "I often stay up late playing online games with my friends. It's the main way we stay connected and have fun together, especially when we can't meet in person."

R46: "I use video calls and social media to keep in touch with my family and friends back home. It helps me feel less lonely and more connected."

R 47: "I notice many of our friends usually do constantly checking their phones and social media. It may they're afraid of missing out on what their friends are doing or the latest trends like song of black pink, BTS and many famous web series"

R 48: "I don't want to miss any updates from my friends or the latest memes.

R 49: "People constantly watch out their phone as they feel anxious about missing updates and social interactions."

R 50: "People are very active on social media. There's a strong sense of needing to stay informed about local events and discussions, leading to increased screen time."

R 50: "Screen time has become such a regular part of our routine. My kids are used to watching TV or playing on their tablets every evening after dinner. It's just what we do."

R 51: "I’ve gotten into the habit of scrolling through social media and watching YouTube videos before bed. It’s part of my nightly routine and hard to break."

R 52: I find myself doing it out of habit, even when I don’t have anything urgent to look at."

R 53: "Many of us using their phones or tablets has become a habitual behavior. They don’t realize how much time they’re spending on screens until it’s pointed out."

R 54: "The endless content keeps them glued to their screens for hours."

"There's always something new to watch or play, whether it's a trending Netflix series, a new video game release, or the latest YouTube sensation. It’s easy to get lost in the endless entertainment options."

R 55: " The variety of content available keeps me engaged for hours."

R 56: “With so many choices available, I can easily spend my entire evening exploring different shows and channels."

R 57: "Between TikTok, Instagram, YouTube, and online games, there’s always something happening, I don’t want to skip anything, makes it hard to step away."

R 58: “Available digital content—movies, series, games, social media—creates a complex web that traps us in prolonged screen time as I thought."

R 59: “The complex web of digital content captures our attention and extends screen time."

R 60: "All the other parents allow their kids to have screen time, so it’s tough to set limits. "

R 61: "If I miss out on what my friends are talking about the next day….it will be problem for me."

R 62: “Being up-to-date with the latest series or viral videos helps me fit in and socialize at work." - "Most of my social interactions happen online.”

R 63: “Staying in digital platform help me to maintain our social ties."

R 64: “I often feel socially isolated without access to digital platforms. Prolonged screen time helps them maintain their social connections and feel less lonely."

R 65: “Screen time is a way to stay connected with friends and family. We use it to socialize, share our experiences, and stay involved in each other’s lives."

R 66: "Students rely on digital platforms to stay in touch with their peers. The social aspect of being online, whether…”

|

Potential interventions and educational initiatives to mitigate the environmental impact of binge-watching focus on encouraging healthier habits and self-control found in the

Table 10E. Individuals can use screen-usage apps to monitor and limit their device time, and prioritize outdoor activities, meditation, reading, and in-person interactions with family and friends. Engaging in journaling or seeking emotional support, including professional help or adopting a pet, can provide healthier emotional outlets. Self-awareness and parental guidance about the negative impacts of binge-watching are crucial, along with government measures to combat piracy, making legitimate content more accessible. These strategies aim to reduce excessive screen time and promote a balanced lifestyle.

Table 10E.

Thematic analysis of the participant’s based on the given question. RQ2B. In what ways do you think individuals can modify their binge-watching habits to minimize environmental impact?

Table 10E.

Thematic analysis of the participant’s based on the given question. RQ2B. In what ways do you think individuals can modify their binge-watching habits to minimize environmental impact?

| Theme |

Summary |

Sample data as examples |

| Potential interventions and educational initiatives would be existed to mitigate the environmental impact of binge-watching. |

Ways that individuals can modify their binge-watching habits to minimize environmental impact.

Break excessive gadget use Habits.

Adopt healthier alternatives like outdoor activities, meditation, and reading books.

Prioritize in person interactions with family and friends.

Engage in activities like journaling or seeking emotional support.

Develop a habit of self-control and focus on personal interests.

Educate individuals about the negative impacts of binge-watching.

Call for stricter governmental measures against piracy to address financial constraints. |

R 67: “Screen-usage apps can help monitor device time and set limits that make sense.”

R 68: “Limit Binge watch time.”

R 69: “By limiting their screen time and enjoy shows and web series occasionally not regular basis like once or twice in a month.”

R 70: “…Reading More Books, Newspapers, etc.”

R 71: “... By looking at your reading habits and hobbies, you can get some relief from this habit…”

R 72: “…Being Physically Active….”

R 73: “...Taking up healthier habits like meditation or picking up a book to read, instead of diving into the gadgets for binge watching.”

R 74: “...Spending time with Loved is much...”

R 75: “…Spending more time with family/friends (in person) to avoid excessive use of electronics…”

R 76: “...being with family...”

R 77: “Developing habits like journaling or talking to a friend, for seeking emotional support...”

R 78: “…Or even reaching out for professional help, if needed. Getting a pet! Stress leads to such harmful coping mechanisms (e.g. binge watching), which might find a way to get channelized out in the presence of an emotional support furry creature...."

R 79: “…. By practicing self-control…”

R 80: “…I think focusing on yourself...”

R 81: “…They have to be self-conscious about the fact.”

R 82: “… Everyone's parents have to be more careful.”

R 83: “……parent must provide them knowledge about the negative outcomes of Binge-watching habit...”

R 84: “Government should take more strict steps to stop piracy. Because no one has money to buy subscription at this age. All that is seen is piracy from the platforms…”

|

Educational institutions should put in place thorough programs that emphasize binge-watching's detrimental impact, as shown in the

Table 10F. These programs might include educational dramas and protests that raise awareness of the negative impact of excessive screen time by showcasing real-world examples. Sports programs and training-based activities can help schools and colleges encourage healthier lifestyles. Additionally, using well-known influencers and celebrities in web series or movies can help students understand the message. Incorporating recycling and renewable energy into these initiatives can help promote a more environmental awareness. By educating and involving students, these tactics hope to inspire them to lead more ecologically conscious and balanced lives.

Table 10F.

Thematic analysis of the participant’s based on the given question. RQ2C. What types of educational programs do you think would be effective in raising awareness about the environmental consequences of binge-watching?

Table 10F.

Thematic analysis of the participant’s based on the given question. RQ2C. What types of educational programs do you think would be effective in raising awareness about the environmental consequences of binge-watching?

| Theme |

Summary |

Sample data as examples |

School, college or institution based environmental educational programme to be carried out.

|

Addressing Binge-Watching: Proposal for Educational Programmes.

Emphasizes on educational programmes depicting potential negative impact of binge-watching.

Suggests awareness campaigns incorporating educational dramas and rallies.

Urges programmes to present real-life outcomes related to excessive screen time.

Recommends implementing training-based activity programs in schools and colleges.

Proposes creating web series or movies featuring influential personalities and superstars to maximize message reach and resonance. |

R 85: “Educational programs which bring forth the actual terrorizing future might work...”

R 86: "...tv shows which.... those depicts the worst-case scenario for excessive non-renewable fuel usage..."

R 87: “Spread Awareness by educational drama, show the bad impacts of binge-watching by a rally...”

R 88: "Make Students Learn about Renewable Energy."

-"Green revolution with the help of recycling."

R 89: “.... The programmes should show case some original facts and results of binge watching…”

R 90: “…Training based activity programme in school-college etc...”

“Sports programme.”

R 91: “… Make web series or movies on this concept hiring big influencers, and superstars whom this age group of students follow religiously…”

|

However, the Tables 10A-10F revealed that individuals spend an average of 4-10 hours daily on screens, with increased usage on college days due to online classes and social media. Screen time encompasses work, social media, entertainment, gaming, and staying connected, with content preferences ranging from quick videos on TikTok and Instagram to educational YouTube tutorials and binge-watching series on Netflix and Amazon Prime. Factors influencing binge-watching include program nature, time constraints, variety, social networking, and the need for emotional release (Panda & Pandey, 2017; Tukachinsky & Eyal, 2018). Limited leisure options, digital convenience, and parental permissiveness also contribute to prolonged screen use. To mitigate the environmental impact, healthier alternatives like outdoor activities, meditation, reading, and in-person interactions should be encouraged. Educational programs highlighting the negative impact of binge-watching, awareness campaigns, and involvement of influencers can promote balanced habits (Chang & Peng, 2022; Starosta & Izydorczyk, 2020). Training-based activities, sports programs, and an emphasis on recycling and renewable energy in schools and colleges can foster environmental consciousness and reduce screen time (Merrill & Rubenking, 2019; Schmidt et al., 2012).

4. Analysis and Interpretation

4.1. Quantitative Analysis and Interpretation

4.1.1. Analysis and Interpretation of Hypothesis 1

The data in

Table 1 is showing the levels and percentages of total no of students in their level of understanding about the environmental impact for binge-watching sessions. Through this table it is clearly analysed that the majority of students (66.67%) fall under the category of "High" levels of concepts about the environmental impact of binge-watching sessions. This advocates that a significant portion of the surveyed students have a heightened awareness of the environmental consequences associated with binge-watching. On the other hand, a substantial but smaller percentage of students (28.57%) fall under the "Moderate" level. This is indicating that there is a sizable portion of the student population that has a moderate understanding of the environmental impact of binge-watching. Whereas, a relatively small percentage (4.76%) falls under the "Low" level, which shows only a small fraction of students have a limited awareness of the environmental consequences of binge-watching. However, the calculated data indicates that the majority of students have a high level of awareness regarding the environmental impact of binge-watching. That could be attributed to increase awareness campaigns, educational programs, or a general societal shift towards environmental consciousness. The moderate percentage reveals there is still room for improvement in educating a segment of the student population. The low percentage implied that a very small proportion of students might not be adequately informed about the environmental impact and impact in relation to binge-watching.

The statistical analysis using an independent samples

t-test of

Table 2 which revealed a significant difference in the levels of understanding about the environmental impact of binge-watching sessions between male and female students. With a calculated

t-value of 4.08 and a remarkably low

p-value of 0.000089 (

p<.0001), both surpassing the critical

t-values of 1.96 at the 0.05 significance level and 2.59 at the 0.01 significance level (4.08 > 1.96, 2.59) with 523 degrees of freedom (

df). However, the said values indicated that the result was significant at a 99% and 95% level of confidence which was in the 99% and 95% region of acceptance. Since the

p-value equals 0 or <.0001, it means that the chance of Type I error, rejecting a correct H

0, was too smaller. The smaller the

p-value more it supported H

1 therefore,

p value <

α, H

1 was accepted.

So, the significance difference between female and male students regarding the levels of understanding about the environmental impact of binge-watching sessions existed. This robust evidence strongly supported the conclusion that female students, with a mean level of 8.53, exhibited a significantly higher understanding compared to male students (mean level of 6.83). Hence, the result is significant at a 99% and 95% level of confidence. So, there was a significance difference between female and male students regarding the levels of understanding about the environmental impact of binge-watching sessions (Qayyoum & Malik, 2023; Starosta & Izydorczyk, 2020). These findings carry important implications for tailored educational strategies, emphasizing the need for gender-specific interventions to enhance awareness of the environmental impact and impact in relation to binge-watching among student populations. So far, this result is concerned, the schools with higher female enrolment rates might place a stronger emphasis on environmental education, and female students might be exposed to more environmental subjects in their curricula or extracurricular activities. Furthermore, gender disparities in the media sources that each gender preferred such as news programs and documentaries might have an impact on how much exposure female students received to discussions of environmental issues in the media. According to studies and surveys (Echavarren, 2023; Li et al., 2022; Xiao & McCright, 2012), women are more likely than males to exhibit concern about environmental issues. This could encourage female students to learn more and gain a deeper understanding of the subject.

4.1.2. Analysis and Interpretation of Hypothesis 2

The results given in

Table 3 reflected that the majority of students (76.19%) fall under the category of "Moderate" levels of awareness about the environmental impact of extended screen time. That suggested that a substantial proportion of the surveyed students possess a moderate level of awareness of the subject. While the majority falls under the "Moderate" category, a noteworthy percentage (19.05%) falls under the "Low" level. Which indicated that a portion of the student population had a lower level of awareness regarding the environmental impact of extended screen time. A relatively small percentage (4.76%) falls under the "High" level, suggesting that only a small fraction of students had a high level of awareness about the environmental consequences of extended screen time. However, the data revealed that while a significant proportion of students had a moderate level of awareness about the environmental impact of extended screen time, there was still room for improvement. Addressing the lower awareness levels and further engaging students through educational strategies can contribute to fostering a greater understanding of the environmental consequences associated with extended screen time.

On the other hand, as shown in

Table 4, that the calculated

t-value of 0.28, followed by the

p-value of 0.77 was smaller than the critical table value with 523 degrees of freedom at a 0.05 and 0.01 level of significance (0.28 <1.96, 2.59). Since

p-value>

α, H

0 cannot be rejected. The mean of the awareness level of the female population was assumed to be equal to the mean of the awareness level of the male population. In other words, the difference between the sample mean of the awareness of female and male was not big enough to be statistically significant. So, the means were not significantly different and the result was also not significant at

p<0.05, 0.01. It means that the chance of a Type I error, rejecting a correct H

0, was too high: 0.77. The larger the

p-value the more it supports H

0. Hence, the result was insignificant at a 95% and 1% level of confidence. So, it indicated that the observed difference in awareness between female and male students was not statistically significant. Based on the comparison of the calculated and critical

t-values, as well as the

p-value, the null hypothesis is accepted. Therefore, there is no significant difference between the group of female and male students in terms of their awareness about the environmental impact of extended screen time on carbon emissions (Kleidermacher & Olfson, 2024; Steger & Witt, 1989). These findings provide valuable insights for designing targeted educational interventions that are equally effective for both genders in enhancing awareness regarding this environmental issue. The reasons of this type of finding can be assume that the both females and males might be equally likely to engage in pro-environmental behaviors, which can correlate with higher awareness and understanding of environmental issues (Blocker & Eckberg, 1997; Kleidermacher & Olfson, 2024; Zhao et al., 2021). Psychological factors, such as empathy and future orientation, might play a role in making individuals more sensitive to the impacts of environmental issues. Empathy can drive a concern for the well-being of others and the planet, while future orientation encourages thinking about long-term consequences, leading to greater environmental consciousness. These traits can be present in both genders, contributing to similar levels of environmental awareness and pro-environmental behaviors.

4.1.3. Analysis and Interpretation of Hypothesis 3

The given data represents in the

Table 5 expressed the levels of binge-watching habits and behavior among a group of 525 students, with percentages assigned to each category. It implies that one-fifth of the surveyed students (19.05%) fall into the category of low binge-watching habits. That suggested that a minority of the students had relatively minimal engagement in binge-watching activities. The majority, around 57.14%, of the students exhibited moderate binge-watching habits. That implied that a significant portion of the student population was moderately engaged in binge-watching, suggesting that it was a common behavior among that group. About 23.81% of the students fall into the high binge-watching category. Which indicated that a substantial but not the majority of students had high levels of engagement in binge-watching activities. However, the data highlighted that a considerable portion of students falls into the Moderate category, indicating that binge-watching was a prevalent behavior among the surveyed group. While a significant percentage falls into the High category, suggesting a substantial number of students had high binge-watching habits, it was not the dominant category. The distribution across the three levels implied diversity in binge-watching habits among the surveyed students.

Correspondingly,

Table 6 indicated the results of the statistical analysis unveil a compelling narrative regarding the binge-watching habits and behaviors of male and female students. With a calculated

t-value of 3.16 and a corresponding

p-value of 0.0020 (

p<.0001), the observed difference between the two groups was strikingly significant. The critical

t-values from the table at the 0.05 and 0.01 levels of significance, with 523 degrees of freedom, are 1.96 and 2.59, (3.16 > 1.96, 2.59) respectively. However, the said values indicated that the result was significant at a 99% and 95% level of confidence which was in the 99% and 95% region of acceptance. Since the

p-value equals 0 or <.0001, it means that the chance of Type I error, rejecting a correct H

0, was too smaller. Notably, the calculated

t-value surpassed both critical values, reinforcing the robustness of the observed distinction. The smaller the

p-value more it supported H

3 therefore,

p value

<α, H

3 was accepted. Consequently, the alternative hypothesis was embraced, underscoring a noteworthy and statistically significant difference between male and female students in terms of their binge-watching habits and behaviors (Mari et al., 2023; Starosta et al., 2019; Taqiyah, 2024). This finding not only contributed valuable insights into the gender dynamics of entertainment consumption among students but also implied the potential need for gender-specific approaches in addressing and understanding binge-watching tendencies within university populations.

Numerous social, psychological, and behavioral factors could be the cause of the reported statistically significant difference in binge-watching tendencies between male and female students (Mari et al., 2023; Taqiyah, 2024). Gender disparities in time management, socialization styles, and media preferences may be quite important. While women may choose genres like drama or romance, which may be devoured differently, men may prefer genres like action or scientific fiction, which stimulate extended viewing sessions. In addition, different viewing habits may be influenced by peer pressure and cultural norms; men may binge-watch more frequently than women as a way to escape reality or create social bonds. Gender disparities may also be influenced by psychological variables, such as leisure activities and coping strategies for stress (Starosta & Izydorczyk, 2020).

4.1.4. Analysis and Interpretation of Hypothesis 4

Table 7 revealed a compelling narrative through the statistical analysis of students' understanding of environmental impact related to technology usage and their awareness of carbon emissions from electronic devices during extended screen time. The students' mean score (M

1) for understanding environmental impact was higher than their mean score (M

2) for awareness of carbon emissions. With 524 degrees of freedom (

df), the calculated

t-value was 12.98, whereas the critical t-values at the 0.05 and 0.01 significance levels were 1.96 and 2.59, respectively (12.98 > 1.96, 2.59). The

p-value was <0.0001, indicating an extremely low probability of a Type I error (rejecting a true null hypothesis). This means the result was significant at both the 99% and 95% confidence levels, well within the regions of acceptance for these significance levels. The calculated

t-value exceeded both critical values, reinforcing the robustness of the observed difference. The smaller the

p-value, the stronger the support for the alternative hypothesis (H

4). Since the

p-value was less than the significance level (

α), H

4 was accepted. Consequently, the alternative hypothesis was embraced, underscoring a noteworthy and statistically significant difference between the levels of understanding and awareness among students. This suggests that students have a significantly better understanding of the broader environmental impact of technology compared to their awareness of the specific issue of carbon emissions from extended screen time (Haleem et al., 2022; Naeem et al., 2023; Pérez-Juárez, et al., 2023). Several reasons might be explained why students had a significantly better understanding of the broader environmental impact of technology compared to their awareness of the specific issue of carbon emissions from extended screen time. In contrast, the specific topic of carbon emissions from electronic devices during extended screen time might not receive as much attention in educational programs (Kiehle et al., 2023; Versteijlen et al., 2017). Additionally, the rapid increase in screen time due to digital learning and entertainment might not yet be widely recognized as a significant environmental issue, contributing to the lower awareness among students.

4.1.5. Analysis and Interpretation of Hypothesis 5

The analysis of correlations between understanding the environmental impact of technology use, awareness of carbon emissions from electronic devices, and binge-watching habits among students, as detailed in

Table 8, reveals several notable relationships. The Pearson correlation coefficient (

r) between understanding environmental eimpact and awareness of carbon emissions is 0.23, indicating a weak positive correlation, meaning that students who are more knowledgeable about the environmental impact of technology also tend to be slightly more aware of carbon emissions (

r(523) = .23,

p < .001) (Belkhir & Elmeligi, 2018; Taufique & Vaithianathan, 2018). Furthermore, the correlation between understanding environmental impact and binge-watching habits is 0.30, suggesting a moderate positive relationship where students with greater understanding of environmental impacts are somewhat more likely to binge-watch (

r(523) = .30,

p < .001), parallel types of study also found by Hajj-Hassan et al. (2024) and Kormos & Gifford (2014). Similarly, the correlation between awareness of carbon emissions and binge-watching habits is 0.26, indicating that students aware of carbon emissions are more likely to engage in binge-watching (

r(523) = .26,

p < .001). The overall coefficient of multiple correlation (

R) is 0.36, showing that the combined understanding of environmental impact and awareness of carbon emissions accounts for a modest portion of the variance in binge-watching habits among students. These findings indeed suggesting that while there are significant relationships, they explain only a limited portion of the variance in students' binge-watching habits. In conclusion, while there are statistically significant relationships between these variables, the correlations are generally weak to moderate, suggesting that understanding and awareness of environmental impacts are related to binge-watching behavior but explain only a limited portion of its variance (Paço & Lavrador, 2017; Seger et al., 2023; Wahjoedi et al., 2023). Further research and targeted interventions are needed to enhance these correlations and promote more environmentally sustainable behaviors among students.

The results of the statistical analysis in

Table 9 focus on the understanding, awareness, and behaviors of students regarding environmental impact, carbon emissions, and binge-watching habits. The between-group variance shows a significant difference in students’ understanding of environmental impact, with a sum of squares (

SS) of 2824.60, degrees of freedom (

df) of 2, and a mean square (

MS) of 1412.30. This results in a very high

F value of 320.10 and a

p value of 0 [

p(x ≤

F) = 1], which is below the significance level (

α), indicating a very low probability of a Type I error (incorrectly rejecting a true H

0) and representing a statistically significant difference between groups. In contrast, the within-group variance related to students' awareness of carbon emissions reveals an SS of 6935.71 with 1572 degrees of freedom and an MS of 4.41, suggesting that most variability is within groups rather than between them. The corrected total variance, which includes the analysis of students' habits and behaviors related to binge-watching, has a total SS of 9760.32 across 1574 degrees of freedom and an overall MS of 6.20. The test statistic [

F(2, 1572) = 320.10,

p = 0 < 0.05, 0.01] exceeds the critical values (2.99, 4.60) at both the 95% and 99% confidence levels, reinforcing the rejection of H

0. The large observed impact size (

f = 0.64) and

η² (0.29) suggest that the differences between group means are not only statistically significant but also practically meaningful, with the groups explaining 28.9% of the variance. Specifically, the means of groups

x1 and

x2, as well as

x1 and

x3, show significant differences. This strong evidence supports the alternative hypothesis (H

1) that not all group means are equal. This comprehensive analysis demonstrates that while there are notable differences in students’ understanding of environmental impacts, their awareness of carbon emissions exhibits less variation, and their habits and behaviors concerning binge-watching contribute to the overall variance observed.

However, the disparities in education, information availability, and individual interest in environmental issues are probably the causes of the observed discrepancies in students' comprehension of environmental impacts (Zeng et al., 2023; Zsóka et al., 2013). Students who have participated in extracurricular sustainability-focused activities or taken environmental science courses may have a better understanding of these impacts. On the other hand, the general public's discussion of climate change and the extensive media coverage of carbon emissions may be responsible for the comparatively high level of awareness among various student populations (Cordero et al., 2020; Sampei & Aoyagi, 2009). The study found that there are overall differences in binge-watching habits and behaviors that can be attributed to various factors such as time management skills, social influences, availability of streaming services, and individual lifestyle choices.

4.2. Qualitative Analysis and Interpretation