2. Materials and Methods

The WAI was used to assess the work ability of Family and Community Nurses (FNCs) in the largest Local Health Authority (LHA) of Tuscany, to evaluate an individual’s capacity to perform their work tasks, considering the demands of their job, their health status, and their mental resources. Among all nurses, FNCs were selected because they play a crucial role in providing comprehensive, continuous, and coordinated care to individuals and families within the community. Their work is integral to promoting health, preventing illness, and managing chronic conditions in a way that is culturally sensitive and tailored to the specific needs of the community. The COVID-19 pandemic has further highlighted the necessity of reducing hospital admissions to alleviate the burden on healthcare systems. FNCs are essential in this context as they can effectively manage and monitor patients in the community, reducing the need for hospital visits. The primary endpoint consists in evaluating the degree of work ability among FCNs within the territorial nursing care of the LHA. The secondary endpoint consists in identifying any changes in work ability in relation to chronological age, gender, nationality, professional age, work setting, type of professional training, job demands, and existing pathologies. We aim to conduct this assessment on a regular basis over time and eventually expand it to include all nurses working within the LHA. This intervention aims to assess the work ability of the nurses by capturing their self-reported perceptions regarding their current work ability compared to the best period of their life, the demands of their job, diagnosed illnesses, impairment due to illnesses, absenteeism due to illness, their own prognosis of work ability for the next two years, and their mental resources. The survey will provide insights into how these demographic and occupational variables influence the nurses’ work ability and will help identify factors that may impact their ability to balance personal and professional life effectively.

The WAI consists of the following items:

Current work ability compared to the best time of life (0-10 points);

Work ability in relation to job demands (2-10 points);

Number of current diagnosed diseases (1-7 points);

Reduction in work ability due to diseases estimated by the individual (1-6 points);

Absences due to illness in the last 12 months (1-5 points);

Perception of own work ability in the next two years (1, 4, 7 points);

Mental resources (1-4 points).

The index can range from 7 to 49. Based on it, different levels of work ability and goals to pursue are defined according to the following table:

Table 1.

Range of WAI.

| Score |

Work Ability |

Aim |

| 7-27 |

Poor |

Restore work capacity |

| 28-36 |

Mediocre |

Improve work capacity |

| 37-43 |

Good |

Support work capacity |

| 44-49 |

Excellent |

Maintain work capacity |

Alongside the questionnaire, additional questions were included in the census sample regarding variables such as gender, age, nationality, professional age, specific workplace location within the LHA, work setting (outpatient services, community work setting, or both), professional training (regional school -nursing schools before the transition to University system-, three-year bachelor’s degree, master’s degree in nursing, first and second level master’s degree, Ph.D.). The questionnaire was electronically administered in accordance with the GDPR (General Data Protection Regulation) 2016/679, the main European legislation on the protection of personal data. FNCs were informed that participation was voluntary, and that non-participation or withdrawal would not result in prejudice or harm to them. Within the database, data were collected anonymously. The total sample consisted of 178 full-time FCNs, and their answers were analysed using descriptive and inferential statistical tools, which allowed us not only to obtain a detailed picture of the characteristics of the FCNs personnel, but also to correlate the WAI with different variables of interest. Data analysis was performed using IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 29.0. and WAI associations with gender, chronological and professional age, work setting, and educational attainment were explored.

3. Results

Out of 481 FCNs working in the LHA, the 37% responded, determining a sample of 178 FCNs. In

Table 2, the overall chronological age is represented: the sample’s age ranges from 25 to 63 years, with a mean age of 46.7 and a SD of 10,42.

Detailed percentages for each age group within the study sample are provided based on age ranges and gender composition are provided in

Table 3:

The sample consists of 82.02% women and 17.98% men. Compared to the total, only 4 people are not of Italian nationality. As depicted in

Table 4, the 62.36% of nurses have been working for more than 20 years, 17.42% for 11-20 years, and 20.22% for less than 11 years.

Next table (

Table 5) provides details on sample’s professional training and work setting: the 38.20% of the sample attended the regional school, 15.17% hold a bachelor’s degree, and 24.16% hold a bachelor’s degree in nursing. Among these, 6 nurses have a master’s degree, 18.45% have a master’s degree, the rest in obtained a Ph.D.

Most of the sample (54,49%) works in home setting, the 11,24% works entirely in the outpatient setting, while 34.27% carry out their work in both outpatient and home settings.

"Poor" WA (1.69%), "mediocre" (24.16%), "good" (51.12%), and "excellent" WA (23.03%) are the overall results, which are also differentiated by gender. Overall, 74.15% of the sample falls within perceived WA scores of good or excellent level, while 25.85% fall within a mediocre or poor level. Women exhibit better perceived WA compared to men; in fact, 76.03% of women fall within scores of good or excellent level, whereas men in the same category constitute 65.63%. Conversely, 23.97% of women have a mediocre or poor level of perceived WA, compared to 34.38% of men.

Analysis of the individual items that constitute the WAI, as reported in

Table 7, overall and divided per gender. The mean and SD of the score for each item were calculated according to variations in chronological age and professional age. Additionally, the mean and SD of the score for each item were calculated according to variations in chronological age and divided by gender. The same was done for professional age. These results were included solely as measures reported in the comments related to the analysis of each individual item.

The type of commitment required for the job: the 2,25% of the sample declared that the commitment required is predominantly physical, the 14,61% declared it as predominantly mental, and the 83,15% declared that the nature of the commitment required is both physical and mental.

The average scores of the various items do not differ significantly between women and men.

1. Current work capacity compared to the best period of your life. Maximum work capacity has a value of 10. Respondents are called to give a score on their current work capacity. The overall mean is 7,67 and women self-assessed a 7,71 compared to 7,5 men’s mean value. This item shows a peak in the chronological age range of 36-45, and then decreases again. Regarding professional age, decreases are observed in the ranges of 6-10 and more than 20 years. There are no substantial differences between the two genders for both categories (chronological age and professional age).

2. Work capacity in relation to job demands: respondents were asked to estimate from very good and very poor (on a 5 points Likert scale). This item shows a progressive decrease of work capacities in relation to job demands with professional age, and this decrease is also observed with chronological age, particularly from the age of 46. An opposite trend is observed between the two genders for both categories (chronological age and professional age).

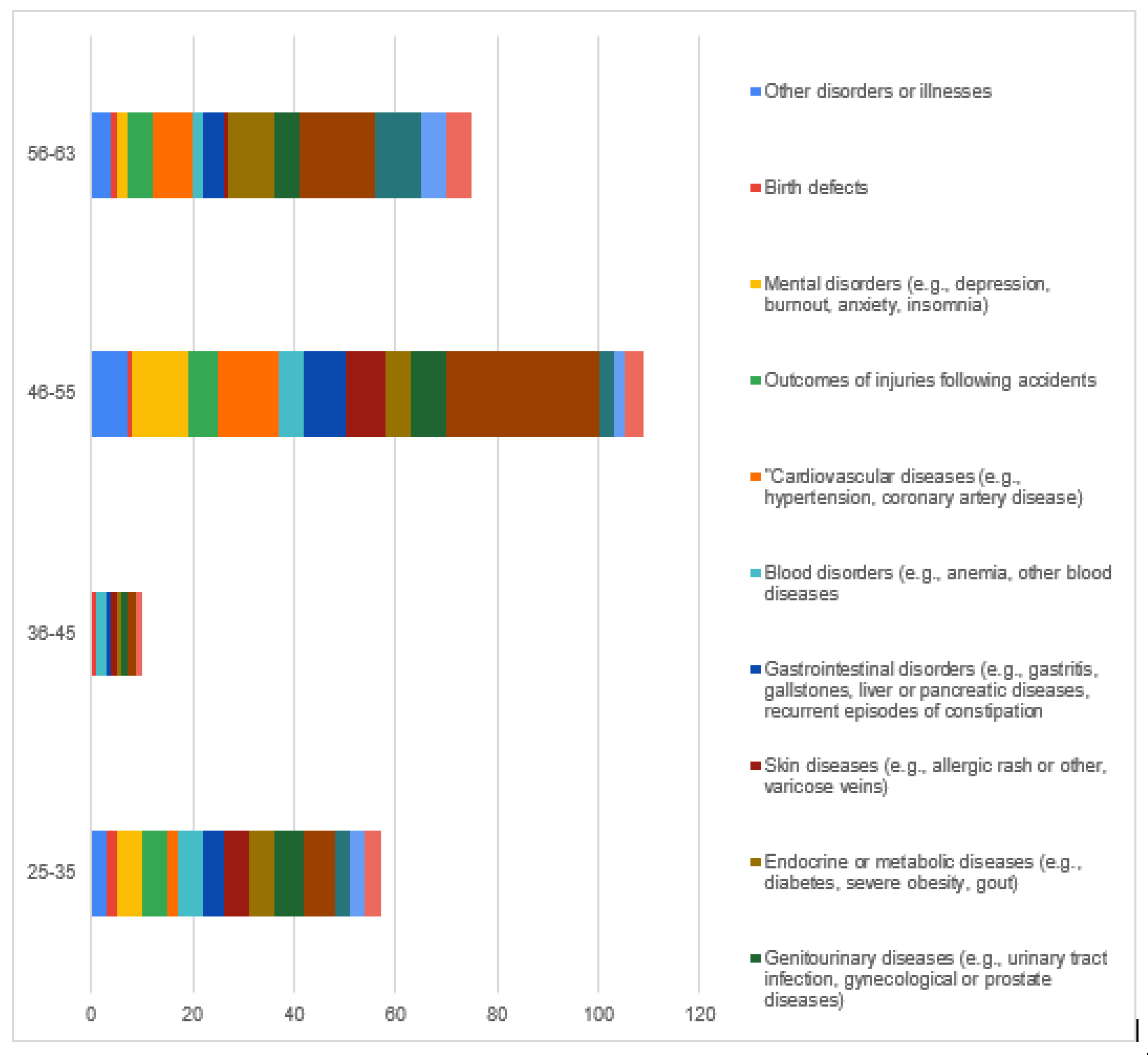

3. Number of current illnesses diagnosed by a physician. The broad categories to which respondents have responded include outcomes of injuries following accidents, musculoskeletal disorders, cardiovascular diseases, respiratory diseases, mental disorders, digestive diseases, genitourinary diseases, skin diseases, tumours, endocrine and metabolic diseases, blood disorders, birth defects. A more substantial difference exists regarding the number of currently diagnosed diseases, with women having a mean of 5.32 and men having a mean of 4.25. The peak occurs in the chronological age range of 36-45 years, followed by a progressive decrease. The trend also declines regarding professional age, after 20 years of work. As additional information, here are the percentage values related to health conditions: 38.76% of the entire sample states not to have any pathology, 36.86% have a medical diagnosis for pathologies, and 24.38% report having pathologies but without a medical diagnosis. Considering the group of subjects with medical diagnoses, the most reported pathologies are musculoskeletal disorders (21.12%), followed by cardiovascular diseases (8.76%), endocrine or metabolic diseases (7.97%), genitourinary diseases (7.57%), mental disorders (7.17%), and gastrointestinal diseases (6.77%), as reported in

Figure 1.

4. Estimate of reduced work capacity due to illness. Respondents were asked how much their current work was hindered by their health conditions. Both chronological and professional trends decrease over time, for both genders.

5. Absences due to illness in the last year. Respondents were required to indicate how many full days of work have they been absent from work due to health issues (illness, treatments, visits, diagnostic exams) choosing from: none, less than 10 days, 10 to 24 days, 25 to 99 days, 100 to 365 days. This item peaks in the chronological age range of 36-45 and then decreases again, while regarding professional age, the curve notably declines in the 11-20 range. The trend is opposite for the two genders: women decrease over time, while men increase.

6. Assessment of work capacity over the next 2 years. Considering their current health conditions, respondents were required to indicate if they felt unlikely, or not sure, or fairly sure to perform their current job in the next 2 years. The peak of “fairly sure” forecast shows two peaks in the chronological age ranges of 36-46 and in professional age within the 11-20 interval, followed by a decrease in both cases. No substantial differences are highlighted between the two genders.

7. Personal resources. Respondents were asked to self-assess their ability to perform your usual daily activities satisfactorily recently (often, quite often, sometimes, rather rarely, never). There is a decrease with advancing chronological age and a progressive decline with increasing professional age. The curves in both genders are very similar in both categories.

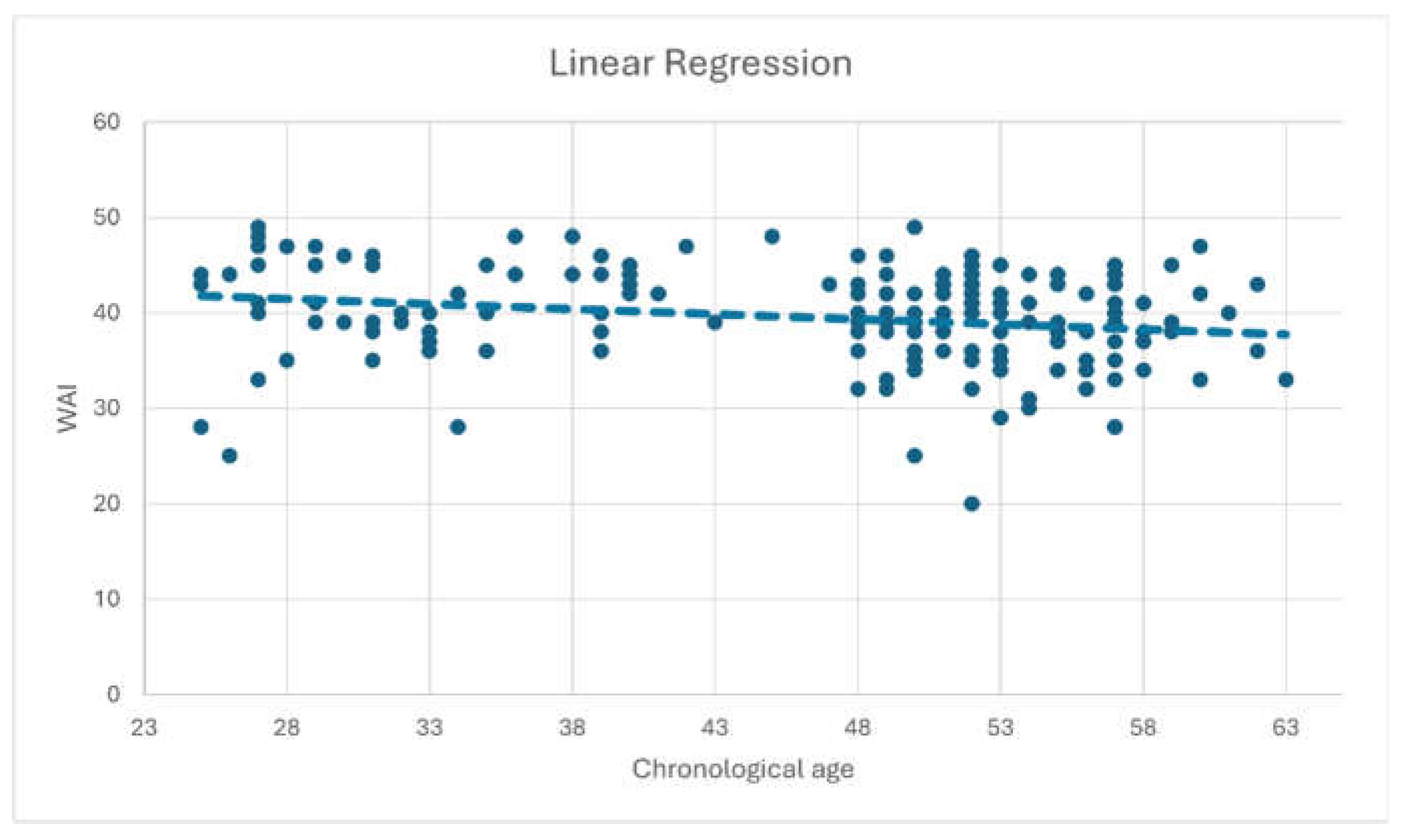

After describing the data statistically in their general form, the interrelation between the WAI and chronological age was analysed. Using the Pearson correlation coefficient (ρ), a negative correlation (p < 0.05) between the WAI and participants’ age is highlighted, as reported in

Table 8.

This indicates that as the variable of chronological age increases, lower scores are observed in relation to work ability, thus indicating a perceived lower work capacity by the individual. This means that younger nurses exhibit a higher work ability index compared to older nurses. A linear regression analysis relating the dependent variable WAI (y) to the explanatory variable chronological age (x) was performed. As depicted in

Figure 2, shows a result which is consistent with the Pearson analysis, consisting of a line with a coefficient β of -0.22 and a constant B of 44.49.

In addition, another factor we have focused on is professional age, calculating both WAI’s mean and SD for each range of years of professional experience, as shown in

Table 9:

The mean WAI index decreases with increasing professional age of the subjects involved. As shown in

Table 10, 56.70% of those who work solely in home settings report having good work ability, while 21.65% consider it mediocre. There doesn’t appear to be a significant difference in the percentages of "good" and "mediocre" work ability among those who work in ambulatory settings.

WAI’s mean and SD were calculated for the different settings, and the WAI indicates (in descending order) an average work ability index of 39.89 with a SD of 4.42 for home setting, 39.42 with a SD of 5.46 for both settings combined, and 37.45 with a SD of 6.54 for outpatient settings.

Regarding the educational attainment (

Table 11), a mediocre work ability is mostly indicated by those who attended the regional school, obtained a bachelor’s degree, or attended post-basic studies; however, most of these individuals still fall into the "good" category. For the majority of those who obtained a bachelor’s degree, a good to excellent work ability is reported, as shown in

Table 11.

From the table below (

Table 12), it can be observed that the WAI results indicate an average work ability index of 40.16 with a SD of 4.70 for individuals who report having no diagnosed pathologies, and 35.17 with a SD of 5.31 for those with diagnosed pathologies.

Additionally, the mean and SD scores were calculated for each item based on educational attainment. FNCs who attended regional school or obtained a bachelor’s degree show significantly lower current work ability compared to those with different educational backgrounds (such as a bachelor’s degree or post-basic training).