1. Introduction

Padel, known for its dynamic ball interactions and adaptable playing space,1 is experiencing rapid global growth. It currently boasts representation in over 60 countries through the International Padel Federation.2 Similar to other net/wall sports, padel involves players projecting an object (ball) to prevent its retrieval by the opposing pair.3 Its simplicity in rules and flexibility in demands make it accessible to players of all ages and skill levels, contributing to its widespread popularity.4-6 In addition, recently there has been a significant increase in scientific research on padel, focusing on performance analysis,7-9 and psychophysiological aspects.10-13

Within the domain of technical-tactical analysis in padel, research predominantly focuses on examining the final shots of each point.14-16 Some of these studies categorize shots simply as winners or errors,14,17 while others distinguish between winners, forced errors, and unforced errors.18-19 It is worth noting that a forced error from one pair is caused by a generator of forced error from the opposing pair,20 a reason why we also considered this shot’s effectiveness.

Research has also explored the differences between winning and losing pairs in professional padel.21-23 These studies suggest that match-winning pairs win more points,23 and make more winners,22,24 fewer errors (both forced and unforced), and more winners using the smash and the volleys.22 Moreover, winning pairs commonly excel in prolonged points (lasting over 11 seconds) and refrain from making unforced errors within the initial four seconds of the point,21 score more points and make fewer unforced errors at the net.25 Regarding shot distribution, winning pairs play more shots without bounce (i.e., smash, bandeja, volley).26 Concerning the score, winning pairs produce more break points and win more points of this type,22,23 as well as win more golden points.23,27 It is worth noting that in our study, we adopted the set, rather than the match, as the unit of measurement, consistent with previous studies.7,28 According to the regulations,2 a padel match is determined by the pair that secures victory in two sets before the opponent. Consequently, in a three-set match, the findings could potentially induce confusion since each pair would claim one set before contesting a third and decisive set.

While professional padel has garnered considerable attention, the field of high-level performance analysis in the sport remains relatively unexplored.15,29-30 Moreover, existing research predominantly focuses on Spanish players, despite the growing global popularity of the sport.2 Limited literature exists comparing winning and losing pairs at this level.15,29 These studies reveal noteworthy disparities, indicating that winning pairs execute a notably higher proportion of winners, particularly cross-court smashes and volleys from offensive positions.29 Furthermore, winning pairs demonstrate a prevalence of winners at the net and fewer baseline errors.15 Additionally, the strategic analysis underscores the significance of maintaining net positions during the last two shots of each rally, with the most common sequences involving groundstroke-volley and lob-smash combinations, thereby enhancing the likelihood of victory.15

Given the lack of performance analysis research on high-level male padel players from nationalities other than Spain, the present study aimed to describe and distinguish shot characteristics between set-winning and losing pairs in high-level male padel players from Finland. The following hypotheses were established: 1) winning players will produce more winners and commit fewer errors (forced and unforced, respectively) than losing players, 2) winning players will produce more winners and generators of forced error through overhead shots and volleys while losing players will commit more forced and unforced errors through any type of shot.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Research Design

The design of this research is framed under empirical methodology and more specifically it is a study with a descriptive strategy. Likewise, it is included within the observational category, being nomothetic, punctual, and multidimensional.31

2.2. Sample

4,469 points were analyzed from 38 matches (18 pressure training matches and 20 official competition matches). Only full sets were examined. In other words, if the third set was a supertiebreak, it was not considered. The matches took place in 2022 and 2023 in Finland. All the competition matches belonged to tournaments of the highest category. The obtained points counted for the ranking of the Finnish Federation. The male players (n = 30) were top 60 in the ranking of the Finnish Padel Federation. All procedures were conducted according to the ethical standards in sport and exercise science research32 and the local ethics committee.

2.3. Study Variables

The following variables were defined and analyzed based on their categorical core and degree of openness:33

- Match type: a difference was made between pressure training matches and official competition matches.

- Set outcome: a difference was made between set-winning and set-losing players.

- Effectiveness of the last shot: winner, forced error, or unforced error. These categories are defined based on previous studies.19

- Generator of forced error: shot which induces a forced error in the opposing pair. This variable was used in previous studies.20

- Shot type: a difference was made among bandeja, smash, fake smash, recovery smash, forehand volley, backhand volley, forehand bajada, backhand bajada, forehand, backhand, back wall forehand, back wall backhand, side wall forehand, side wall backhand, double wall forehand, double wall backhand, first serve, second serve, return, contrapared and other (cadete, willy...). The definition of each of these categories was based on previous studies.14,17

2.4. Procedure

The players were informed by the coach that they would undergo pressure training. Pressure training refers to an intervention designed to assist athletes in performing under pressure by deliberately exposing them to stressors during training sessions.34-36 In our study, players were recorded during the practice matches while their technical-tactical performance was evaluated by the head coach of the first-ever professional padel team of Finland.

An observer, a PhD student in Sports Sciences, certified padel coach, and with a considerable number of published scientific research related to the topic of study, observed the matches live and recorded the study variables through an ad-hoc instrument. At the end of the collection process, an intra-observer reliability analysis was performed to ensure the veracity of the data collected. The observer reanalyzed a random sample of 6 matches (matches were recorded) to ensure enough relevant data to represent 10-20% of the study sample.37 The mean intra-observer reliability was 0.90, considered almost perfect.38 In addition, another observer, a PhD in Sports Sciences, certified padel coach, and with a large number of published scientific research related to the topic of study, also analyzed a random sample of 6 matches to calculate the average inter-observer reliability, which was 0.84.38

2.5. Statistical Analysis

An inferential analysis was used to create contingency tables. Chi-square (χ2) test was used to obtain the association between variables. The strength of association between variables was also calculated, for which Cramer's V coefficient (Vc) was used.39 Research has differentiated the strength of association according to the value, considering a small (<0.100), low (0.100-0.299), moderate (0.300-0.499), or high (>0.500) association.40 Subsequent Z-tests were performed to compare column proportions, adjusting for p values <0.05 according to Bonferroni. Contingency tables allowed the identification of associations between variable categories through corrected standard residuals (CSR). Residuals > |1.96| betrayed cells with more or fewer cases than there should be.39 The significance level was set at p <0.05 and statistical analysis was performed using the SPSS 27.0 statistical package for Windows.

3. Results

Table 1 shows the differences in the effectiveness of the last shot in different contexts. There was a relationship between the effectiveness of the last shot and the set outcome (X2 = 59.953; df = 2; p < 0.001; V = 0.165) in pressure training matches and (X2 = 46.914; df = 2; p < 0.001; V = 0.144) in competitive matches.

The set-winning players produced more winners (pressure training matches: CSR = 7.7; competition matches: CSR = 6.8) and committed less forced (pressure training matches: CSR = 4.2; competition matches: CSR = 2.8) and unforced errors (pressure training matches: CSR = 4.0; competition matches: CSR = 4.3) than the set losing players.

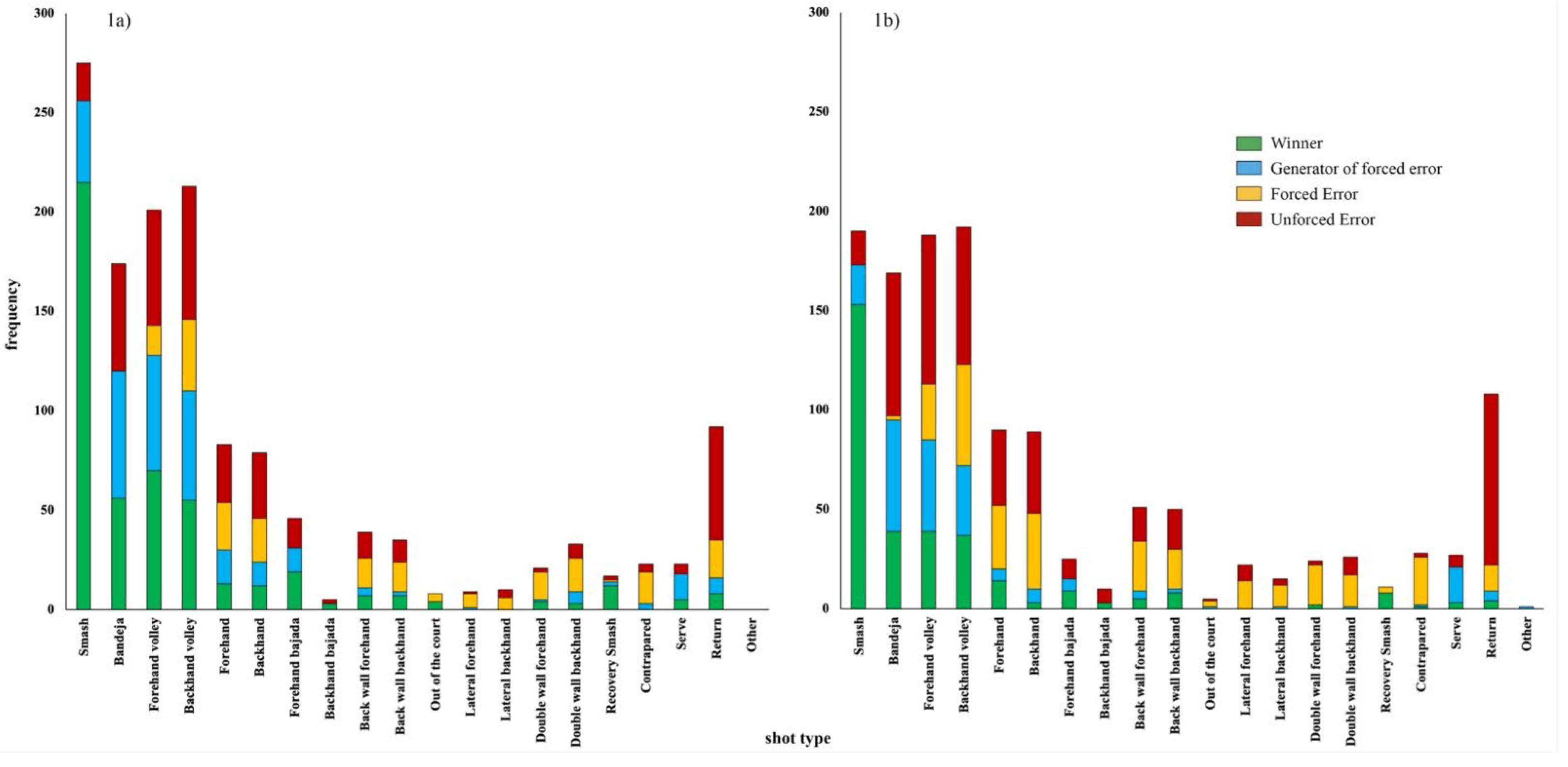

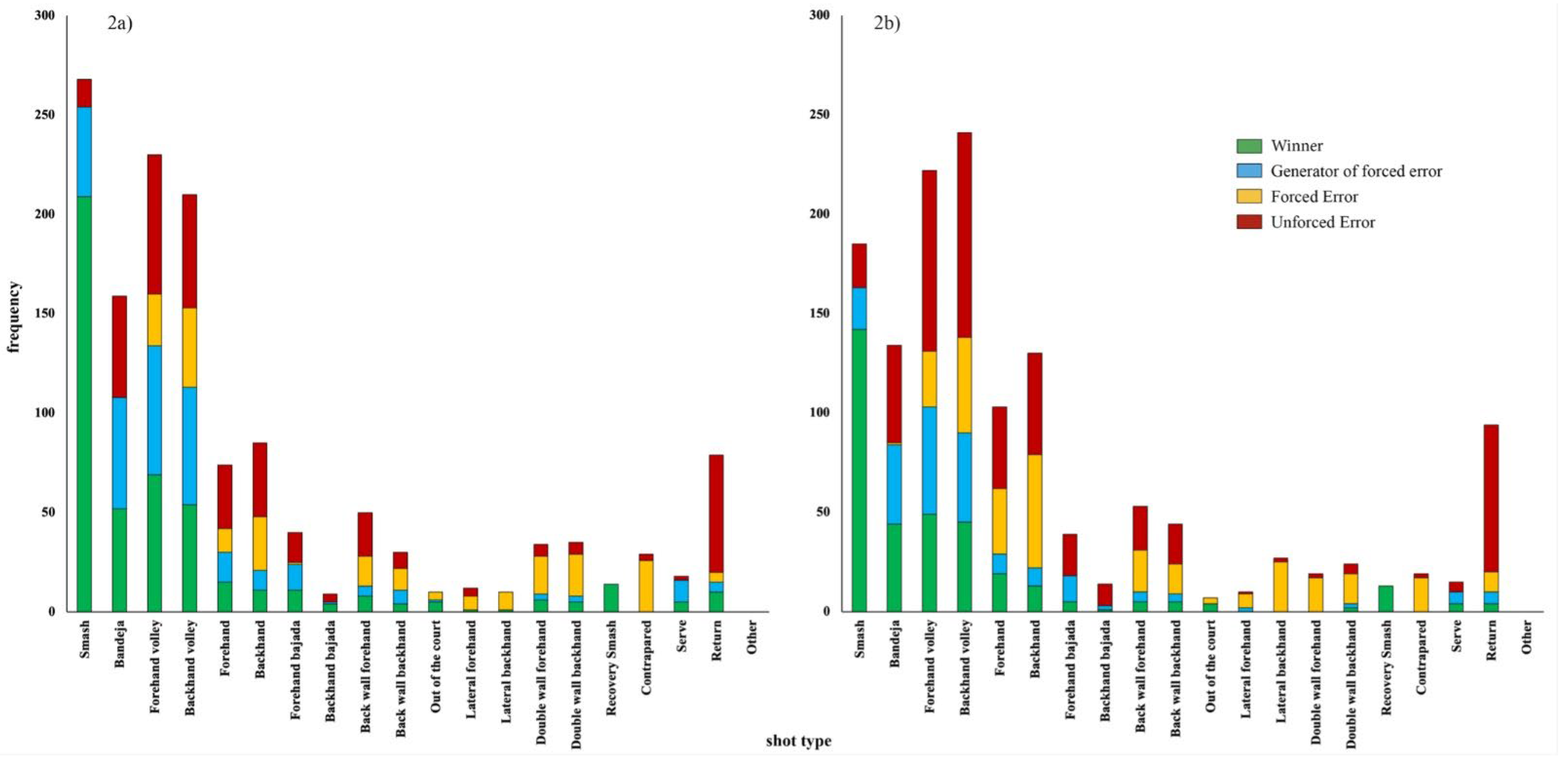

As shown in

Figure 1 and

Figure 2, irrespective of the match type, winning players finished the point with the smash more often than losing players, with the unforced errors very similar in absolute terms in all cases. Moreover, with the rest of the no-bounce shots (bandeja and volleys), winning players obtained more points through winners and generators of forced error. Winning players also made fewer errors with these shots, especially with the volleys. It is also worth highlighting that losing players made more errors with the forehand, backhand, and return than winning players.

Table 2 shows the differences in winners between set-winning and set-losing players. There was no relationship in pressure training matches between the shot type and the set outcome (X2 = 13.937; df = 16; p = 0.603; V = 0.130) in winners. Furthermore, there was no relationship in tournament matches between the shot type and the set outcome (X2 = 15.810; df = 17; p = 0.537; V = 0.137) in winners. Both winning and losing players can achieve winners with the same probability regardless of the type of shot they execute.

Table 3 shows the differences in generators of forced error. There was no relationship in pressure training matches between the shot type and the set outcome (X2 = 20.297; df = 18; p = 0.316; V = 0.200) in generators of forced error. Furthermore, there was no relationship in tournament matches between the shot type and the set outcome (X2 = 12.197; df = 15; p = 0.664; V = 0.153) in generators of forced error. In pressure training matches, losing players played more generators of forced error with the serve.

Table 4 shows the differences in forced errors between winners and losers depending on the shot type. There was no relationship in pressure training matches between the shot type and the set outcome (X2 = 10.726; df = 14; p = 0.707; V = 0.145) in forced errors. In addition, there was a relationship in tournament matches between the shot type and the set outcome (X2 = 27.287; df = 14; p = 0.018; V = 0.229) in forced errors. In pressure training matches, winning players made more forced errors with the return. In competition matches, losing players made more forced errors with the forehand, backhand, and side wall backhand. Winning players made more forced errors with the contrapared.

Table 5 shows the difference in unforced errors between set-winning and set-losing players according to the shot type. There was no relationship in pressure training matches between the shot type and the set outcome (X2 = 18.052; df = 18; p = 0.452; V = 0.144) in unforced errors. Moreover, there was no relationship in pressure training matches between the shot type and the set outcome (X2 = 20.930; df = 16; p = 0.181; V = 0.151) in unforced errors. In pressure training matches, losing players committed more unforced errors with the side wall forehand. In competition matches, losing players committed more unforced errors with the backhand volley.

4. Discussion

The present research aimed to describe and distinguish shot characteristics between set-winning and losing pairs in high-level male padel players from Finland. The novelty of this study stems from examining how the point ends in high-level players from Finland, considering also the generators of forced error.

4.1. Differences in Last-Shot Effectiveness Between Winning and Losing Pairs

As an initial hypothesis, it was established that winning players would produce more winners and commit fewer forced and unforced errors compared to losing players. Our hypothesis was fully accepted. Regardless of the match situation (pressure training match or competition match), winning players significantly produced more winners and committed fewer forced and unforced errors compared to losing players (see

Table 1). These results underscore the intrinsic link between efficient shot execution and set outcome, highlighting the pivotal role of winner production and error minimization in determining success within the realm of high-level padel competition. Such findings contribute to a deeper understanding of the performance dynamics inherent to padel, thereby informing coaching strategies and player development initiatives aimed at optimizing on-court performance. Previous research conducting similar studies has solely distinguished between winners and errors, neglecting to differentiate between forced and unforced errors or to consider the shots that generate forced errors.14,17,24,29 In each instance, these studies consistently concluded that the winning pair makes more winners while the losing pair makes more errors.

4.2. Decisive Shots Distribution

Based on the findings of this study (see

Figure 1 and

Figure 2), high-level male padel players achieved more winners, and generated more forced errors, regardless of match type or set outcome, using shots that involve no bounce (smash, bandeja, and volleys). Nonetheless, a notable number of errors (both forced and unforced) are committed with the bandeja and volleys (forehand and backhand). Furthermore, it is worth highlighting the large occurrence of errors (forced and unforced) in shots following a bounce, particularly in the forehand, backhand, and return.

Concerning the overhead shots (i.e., the smash and bandeja), previous studies reported that they account for approximately 52 to 58% of the winning actions in professional padel.14,17,19 Additionally, research has shown that players commonly secure winners through their smashes when these are flat or topspin (spin), down the line (direction), by three or four meters (outcome),41 and when they are executed proximate to the net (area), while their shots typically result in errors when executed with slice spin (that is commonly named bandeja), directed cross-court, causing the ball to either stay within their court (without passing the net) or land directly on the fence or glass in the opponent's court, particularly when hit from a distance away from the net. Furthermore, it has also been shown that the bandeja is the predominant shot among padel players,42 with a percentage of continuity of almost 90%, whereas flat and topspin smashes were identified as the primary shots for securing winners. Therefore, high-level male padel players should treat the bandeja as a conservative shot, aiming to maintain net dominance while minimizing unforced errors. In less challenging scenarios, the objective should be to compel the opposing pair into executing uncomfortable shots. In addition, it is recommended for these players to view smashes as finishing shots, employed to secure winners and generate forced errors in their opponents.

Concerning volleys (forehand and backhand), in addition to being prominent shots through which high-level male padel players achieve numerous winners and generate forced errors, they were also the shots most associated with both forced and unforced errors. Prior studies, which have undertaken analogous investigations into the effectiveness of the different shot types in men's professional padel, similarly suggest that volleys are among the technical-tactical actions through which players secure numerous winners. Nevertheless, they are equally associated with a higher frequency of errors (both forced and unforced).14,17 Hence, when positioned at the net, players should prioritize volleying to maintain the initiative. Only in favorable circumstances (e.g., a high ball at the net or an easy incoming ball with the opponents in a bad position), players should seek to generate forced errors or secure winners. Conversely, during challenging situations (e.g., a low ball to the net, or a very fast incoming ball to the body), players should adopt a more conservative approach to mitigate errors (both forced and unforced) and prevent giving up easy opportunities to opponents, thus increasing the chances of preserving net dominance.

When considering shots played off one bounce, it is important to highlight the frequency of forced and unforced errors committed by players when executing shots without using the wall (i.e., forehand and backhand). This is particularly evident among losing pairs. Previous studies have also indicated that men tend to commit more errors (both forced and unforced) when playing forehands or backhands compared to other types of shots.14,17 Perhaps these types of shots are usually played in the back of the court.43 Thus, padel players should reduce the number of unforced errors by focusing on targeted training for these strokes. For instance, in favorable tactical scenarios, players should aim to seize control of the point (e.g., by disguising their intentions, faking that they are going to play a chiquita and, instead, playing a deep lob to surpass the opponents) with sufficient margin to minimize unforced errors. It is also worth mentioning the considerable number of unforced errors with the return (that is, the first shot of the pair that is not serving). High-level male padel players should allocate more time to training this crucial aspect of the game. Winning a set needs breaking the serve one more time than the opposing pair, rendering it particularly challenging if the return fails to be put into play.

Differences in last-shot effectiveness and shot type between winning and losing pairs

It was also hypothesized that winning players would produce more winners and generators of forced error through overhead shots and volleys while losing players would commit more forced and unforced errors through any type of shot. Although in absolute terms this seems true (see

Figure 1 and

Figure 2), when comparing each shot’s effectiveness between winning and losing pairs (see

Table 2,

Table 3,

Table 4 and

Table 5), there are barely any differences in relative terms. Differences were only found in generators of forced errors (

Table 3), forced errors (

Table 4), and unforced errors (

Table 5) in a few technical-tactical actions. Concerning generators of forced errors, losing players executed more generators of forced errors with the serve. Linked to this, regarding forced errors, in pressure training matches, winning players committed more forced errors with the return. This trend could potentially be attributed to the strategic response of losing players, who may opt for more aggressive serves in their bid to regain control or shift momentum in the set. The serving pair has a significant advantage in the point since it allows the pair to occupy areas close to the net.44 In competition matches, losing players committed more forced errors with the forehand, backhand, and side wall backhand. This could be attributed to winning players executing more offensive actions compared to losing players.26 It is plausible that losing players may struggle with performing their shots effectively, as this scenario increases the players’ anxiety,13,45 leading to a higher incidence of generators of forced errors from the winning players. On their part, winning players committed a higher frequency of forced errors with the contrapared, a shot typically utilized as an emergency response. This observation may underscore the proactive and determined approach of winning players, who tend to demonstrate a willingness to engage fully in every rally, even using emergency shots when necessary, which will increase their self-confidence.13,45 Regarding unforced errors, in pressure training matches, losing players committed more unforced errors with the side wall forehand. And, in competition matches, losing players committed more unforced errors with the backhand volley. Thus, these findings enable us to identify the specific shot types with which losing players tend to commit more unforced errors.

4.3. Strengths

This study possesses several notable strengths. Firstly, it stands among the pioneering studies that explore the technical-tactical performance of high-level players from Finland, specifically distinguishing between winning and losing players. Secondly, this study represents a pioneering endeavor in differentiating between forced and unforced errors, while also examining the shots accountable for generating forced errors.

4.4. Limitations and Future Studies

It is crucial to acknowledge certain limitations inherent in this study. Only high-level male padel players from Finland were examined. Future studies should analyze both male and female players from different skill levels and nationalities. The difference in the set score was not considered. Future studies should consider this difference. Regarding the technical-tactical actions, this study analysed the effectiveness of the last shot and generator of forced error, in case there was one. Future studies should consider every shot of the rally, and the players’ position on-court, as well as evaluate the decision-making and execution of each one of these shots.

5. Conclusions

Compared to their losing counterparts, high-level male winning padel players tend to produce more winners and make fewer forced and unforced errors, irrespective of the match type (pressure training matches or competition matches). Specifically, these players (regardless of the result) achieve more winners and generate more forced errors with shots that do not involve a bounce (smash, bandeja, forehand volley, and backhand volley). However, errors (both forced and unforced) are also common with the bandeja and volleys (forehand and backhand). Furthermore, it is worth highlighting the large number of errors (forced and unforced) in shots following a bounce, particularly in the forehand, backhand, and return. Nevertheless, if the set outcome is considered, differences were observed only in generators of forced errors, forced errors, and unforced errors, in a few technical-tactical actions.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.C. and B.S.A.; methodology, B.S.A.; software, R.C.; validation, I.M.M., A.E.T. and R.C.; formal analysis, M.C.; investigation, A.B.S.; resources, A.B.S.; data curation, M.C.; writing—original draft preparation, R.C.; writing—review and editing, B.S.A; supervision, B.S.A. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Ethics Committee of University of Extremadura (protocol code 163/2023 and 08/02/2024).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Blázquez D, Hernández J. Clasificación o taxonomías deportivas. Barcelona: Monografía. INEF; 1984.

- International Padel Federation. List of countries associated with the International Padel Federation, https://www.padelfip.com/es/federaciones/ (2024, accessed March 09, 2024).

- Siedenton D. Introduction to sport, fitness, and physical education. Palo Alto, CA: Mayfield; 1990.

- Courel-Ibáñez, J.; Cordero, J.; Muñoz, D.; Sánchez-Alcaraz, B.; Grijota, F.; Robles, M. Fitness benefits of padel practice in middle-aged adult women. Sci. Sports 2018, 33, 291–298 . [CrossRef]

- García-Benítez, S.; Courel-Ibáñez, J.; Pérez-Bilbao, T.; Felipe, J.L. Game Responses During Young Padel Match Play: Age and Sex Comparisons. J. Strength Cond. Res. 2018, 32, 1144–1149 . [CrossRef]

- Pradas, F.; Sánchez-Pay, A.; Muñoz, D.; Sánchez-Alcaraz, B.J. Gender Differences in Physical Fitness Characteristics in Professional Padel Players. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Heal. 2021, 18, 5967 . [CrossRef]

- Conde-Ripoll, R.; Muñoz, D.; Sánchez-Alcaraz, B.J.; Escudero-Tena, A. Analysis and prediction of unforced errors in men’s and women’s professional padel. Biol. Sport 2024, 41, 3–9 . [CrossRef]

- Martín-Miguel, I.; Escudero-Tena, A.; Muñoz, D.; Sánchez-Alcaraz, B.J. Performance Analysis in Padel: A Systematic Review. J. Hum. Kinet. 2023, 89, 213–230 . [CrossRef]

- Ungureanu, A.N.; Lupo, C.; Contardo, M.; Brustio, P.R. Decoding the decade: Analyzing the evolution of technical and tactical performance in elite padel tennis (2011–2021). Int. J. Sports Sci. Coach. 2024, 19, 1306–1313 . [CrossRef]

- Bustamante-Sánchez, .; Sebastián, A.A.d.S.; Padilla-Crespo, A. El set disputado influye en la variabilidad de la frecuencia cardiaca en jugadores de pádel de élite. Padel Sci. J. 2024, 2, 139–150 . [CrossRef]

- Bustamante-Sánchez, .; Ramírez-Adrados, A.; Iturriaga, T.; Fernández-Elías, V.E. Effects on strength, jumping, reaction time and perception of effort and stress in men´ s top-20 World Padel Competitions. Padel Sci. J. 2024, 2, 7–19 . [CrossRef]

- Conde-Ripoll, R.; Escudero-Tena, A.; Bustamante-Sánchez, .; Conde-Ripoll, R.; Escudero-Tena, A.; Bustamante-Sánchez, . Pre and post-competitive anxiety and self-confidence and their relationship with technical-tactical performance in high-level men's padel players. Front. Sports Act. Living 2024, 6, 1393980 . [CrossRef]

- Conde-Ripoll, R.; Escudero-Tena, A.; Suárez-Clemente, V.J.; Bustamante-Sánchez, . Precompetitive anxiety and self-confidence during the 2023 Finnish Padel championship in high level men’s players. Front. Psychol. 2023, 14, 1301623 . [CrossRef]

- Escudero-Tena, A.; Almonacid, B.; Martínez, J.; Martínez-Gallego, R.; Sánchez-Alcaraz, B.J.; Muñoz, D. Analysis of finishing actions in men’s and women’s professional padel. Int. J. Sports Sci. Coach. 2022, 19, 1384–1389 . [CrossRef]

- Ramón-Llín, J.; Guzmán, J.; Muñoz, D.; Martínez-Gallego, R.; Sánchez-Pay, A.; Sánchez-Alcaraz, B. Análisis secuencial de golpeos finales del punto en pádel mediante árbol decisional. Rev. Int. De Med. Y Cienc. De La Act. Fis. Y Del Deport. 2022, 22, 933–947 . [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Alcaraz, B.; Jiménez, V.; Muñoz, D.; Ramón-Llin, J. EFICACIA Y DISTRIBUCIÓN DE LOS GOLPES FINALISTAS DE ATAQUE EN PÁDEL PROFESIONAL. Rev. Int. De Med. Y Cienc. De La Act. Fis. Y Del Deport. 2022, 22, 635–648 . [CrossRef]

- Escudero-Tena, A.; Muñoz, D.; Sánchez-Alcaraz, B.J.; García-Rubio, J.; Ibáñez, S.J. Analysis of Errors and Winners in Men’s and Women’s Professional Padel. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 8125 . [CrossRef]

- Mellado Arbelo Ó, Baiget E, Vivés M. Análisis de las acciones de juego en pádel masculino profesional. Cult_Ci_Dep. 2019;14(42):191-201.

- Sánchez-Alcaraz BJ, Jiménez V, Muñoz D, Ramón-Llin J. External training load differences between male and female professional padel. J Sport Health Res. 2021;13(3):445–454.

- Ripoll, R.C.; Genevois, C. Forehand footwork variability in the attacking situation at elite level. ITF Coach. Sport Sci. Rev. 2022, 30, 22–24 . [CrossRef]

- Courel-Ibáñez, J.; Martínez, B.J.S.-A.; Cañas, J. Game Performance and Length of Rally in Professional Padel Players. J. Hum. Kinet. 2017, 55, 161–169 . [CrossRef]

- Escudero-Tena, A.; Sánchez-Alcaraz, B.J.; García-Rubio, J.; Ibáñez, S.J. Analysis of Game Performance Indicators during 2015–2019 World Padel Tour Seasons and Their Influence on Match Outcome. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Heal. 2021, 18, 4904 . [CrossRef]

- Martín-Miguel, I.; Muñoz, D.; Escudero-Tena, A.; Toro-Román, V.; Sánchez-Alcaraz, B.J. Differences in performance parameters between winning and losing pairs in men's and women's professional padel. Int. J. Sports Sci. Coach. 2023, 19, 1339–1348 . [CrossRef]

- Lupo, C.; Condello, G.; Courel-Ibáñez, J.; Gallo, C.; Conte, D.; Tessitore, A. Efecto del género y del resultado final del partido en competiciones profesionales de pádel. [Effect of gender and match outcome on professional padel competition].. RICYDE. Rev. Int. de Cienc. del Deport. 2018, 14, 29–41 . [CrossRef]

- Courel-Ibáñez, J.; Sánchez-Alcaraz, J.B.; Cañas, J. Effectiveness at the net as a predictor of final match outcome in professional padel players. Int. J. Perform. Anal. Sport 2015, 15, 632–640 . [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Alcaraz, B.J.; Courel-Ibáñez, J.; Muñoz, D.; Infantes-Córdoba, P.; de Zumarán, F.S.; Sánchez-Pay, A. Análisis de las acciones de ataque en el pádel masculino profesional. Apunt. Educ. Fis. Y Deport. 2020, 29–34 . [CrossRef]

- Muñoz, D.; Toro-Román, V.; Vergara, I.; Romero, A.; Fuente, A.I.F.d.O.; Sánchez-Alcaraz, B.J. Análisis del punto de oro y su relación con el rendimiento en jugadores profesionales de pádel masculino y femenino (Analysis of the gold point and its relationship with performance in male and female professional padel players). Retos 2022, 45, 275–281 . [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Alcaraz BJ, Courel-Ibáñez J, Díaz J, Grijota FJ, Muñoz D. Efectos de la diferencia en el marcador e importancia del punto sobre la estructura temporal en pádel en primera categoría. J Sport Health Res. 2019;11(2):151-160.

- Ramón-Llin, J.; Guzmán, J.; Martínez-Gallego, R.; Muñoz, D.; Sánchez-Pay, A.; Sánchez-Alcaraz, B.J. Stroke Analysis in Padel According to Match Outcome and Game Side on Court. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Heal. 2020, 17, 7838 . [CrossRef]

- Ramón-Llin, J.; Guzmán, J.; Martínez-Gallego, R.; Muñoz, D.; Sánchez-Pay, A.; Sánchez-Alcaraz, B.J. Análisis de la situación en la pista de los jugadores en el saque y su relación con la dirección, el lado de la pista y el resultado del punto en pádel de alto nivel (Analysis of the situation on the court of the players in the serve and its relationship. Retos 2020, 399–405 . [CrossRef]

- Thomas JR, Martin P, Etnier JL, Silverman SJ. Research methods in physical activity. Champaign:Human Kinetics; 2022.

- Harriss, D.; MacSween, A.; Atkinson, G. Ethical Standards in Sport and Exercise Science Research: 2020 Update. Int. J. Sports Med. 2019, 40, 813–817 . [CrossRef]

- Anguera MT, Hernández-Mendo A. Avances en estudios observacionales de Ciencias del Deporte desde los mixed methods. Cuad Psicol Dep. 2016;16(1):17-30.

- Bell, J.J.; Hardy, L.; Beattie, S. "Enhancing mental toughness and performance under pressure in elite young cricketers: A 2-year longitudinal intervention": Correction to Bell et al. (2013).. Sport, Exerc. Perform. Psychol. 2013, 2, 297–297 . [CrossRef]

- Driskell, T.; Sclafani, S.; Driskell, J.E. Reducing the Effects of Game Day Pressures through Stress Exposure Training. J. Sport Psychol. Action 2014, 5, 28–43 . [CrossRef]

- Stoker M, Lindsay P, Butt J, Bawden M, Maynard IW. Elite coaches’ experiences of creating pressure training environments. Int J Sport Psychol. 2016; 47:262–281.

- Igartua JJP. Métodos cuantitativos de investigación en comunicación. Bosh; 2006.

- Landis JR, Koch GG. The measurement of observer agreement for categorical data. Biometrics. 1977;33(1):159-174.

- Field A. Discovering Statistics Using IBM SPSS Statistics. 5th ed. London: SAGE Publications Ltd; 2018.

- Crewson P. Applied statistics handbook. London:AcaStat Software; 2006. 103-123.

- Escudero-Tena A, Parraca JA, Sánchez-Alcaraz BJ, Muñoz D, Sánchez-Pay A, García-Rubio J, Ibáñez SJ. Análisis de los remates finalistas en pádel profesional. E-balonmano com. 2023;19(2):117-126.

- Sánchez-Alcaraz, B.J.; Perez-Puche, D.T.; Pradas, F.; Ramón-Llín, J.; Sánchez-Pay, A.; Muñoz, D. Analysis of Performance Parameters of the Smash in Male and Female Professional Padel. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Heal. 2020, 17, 7027 . [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Alcaraz BJ, Muñoz D, Escudero-Tena A, Martín-Miguel I, García JM. Análisis de las zonas de golpeo en pádel profesional. Rev Kronos. 2022;21(2):1-9.

- Sánchez-Alcaraz, B.J.; Muñoz, D.; Pradas, F.; Ramón-Llin, J.; Cañas, J.; Sánchez-Pay, A. Analysis of Serve and Serve-Return Strategies in Elite Male and Female Padel. Appl. Sci. 2020, 10, 6693 . [CrossRef]

- Conde-Ripoll, R.; Muñoz, D.; Escudero-Tena, A.; Courel-Ibáñez, J. Sequential Mapping of Game Patterns in Men and Women Professional Padel Players. Int. J. Sports Physiol. Perform. 2024, 19, 454–462 . [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).