1. Introduction

The scientific study of psychological well-being has acquired considerable interest in recent decades. In this context, university students are one of the populations that is attracting most attention, due to the association of this educational stage with possible risks to mental health. Several meta-analyses highlight the increasing prevalence of depression and anxiety in university students [

1,

2], especially after the COVID-19 pandemic [

3,

4]. Academic demands, economic status, adapting to a new context, establishing new social networks, and obtaining employment all contribute to a complex web of stressors [

5,

6]. Students are forced to deal with these challenges simultaneously, which negatively affects their academic engagement and performance and increases university dropout [

7,

8].

The current mental health needs of university students, as well as the multitude of stressors they face, demonstrate the importance of examining psychological well-being in this population and determining effective psychological resources for its promotion. To this end, the present study analyzed the relationship between psychological capital, the coping strategies employed by students in response to the various stressful situations they face, and psychological well-being. Specifically, the aim was to determine whether psychological capital favors the use of adaptive coping strategies that enhance psychological well-being.

1.1. Psychological Well-Being: The Focus on Human Flourishing

The concept of well-being is multifaceted, with varying interpretations across diverse contexts. Two perspectives are currently most relevant in psychological research [

9]. On the one hand, subjective well-being, based on the hedonistic philosophy, has as components the search for pleasurable experiences that grant satisfaction, and the predominance of positive affects over negative ones [

10]. On the other hand, the eudaimonic perspective focuses on psychological well-being, based on personal development and optimal and purposeful functioning in their environment [

11].

Since the emergence of positive psychology, the study of psychological well-being has become particularly relevant. From this neophyte perspective, human flourishing is emphasized as the most genuine exponent of mental health [

12], which is understood as a desired vital state that integrates hedonic and eudaimonic aspects of well-being [

13]. Although various models of psychological well-being representing human flourishing have been proposed, they all converge in the identification of dimensions such as meaning and purpose in life, positive relationships with others, engagement, environmental mastery, self-acceptance, and positive affect [

14]. Thus, this conceptualization of well-being puts the focus on positive psychological functioning, and not only on the absence of pathology or the pursuit of pleasurable experiences [

15,

16].

Given that it represents the essence of psychological well-being, in recent years there has been an unprecedented research production on human flourishing. Regarding university students, studies yield interesting findings on its correlations with other adaptive academic variables. For example, Datu [

17] and Datu et al. [

18] identified the direct positive impact of psychological well-being on perceived performance, learning goal orientation, and delayed gratification. In the same vein, Howell [

19] evidenced that students with higher levels of psychological well-being showed a greater tendency toward self-regulated learning. In addition, psychological well-being has been associated with high levels of self-compassion and purpose in life [

20] and with improvements in mental health and emotional awareness [

21] of university students in different cultural contexts.

1.2. Coping Strategies

The commonly accepted transactional perspective of stress [

22] gives coping strategies a preponderant role in the experience of stress. In response to the innumerable strategies used by humans to cope with stressful events, different taxonomies have been proposed. One of the most widespread is the one that classifies coping strategies into two major typologies [

23]: approach and avoidance. The former would encompass those cognitive and behavioral efforts aimed at providing an active response to the stressor, directly modifying the problem (primary control) or the negative emotions derived from it (secondary control). This group includes, among others, planning, the adoption of a specific action, support-seeking (instrumental and emotional), positive re-evaluation or acceptance. Avoidance coping strategies refer to the cognitive and/or behavioral mechanisms used in an attempt to avoid the stressful situation, such as distraction, denial or desiderative thinking.

In the academic context, approach coping strategies are related to good academic, physical and psychological adjustment [

24,

25]. Thus, adaptive coping strategies show positive and significant correlations with eudaimonic components of well-being, such as self-acceptance and purpose in life [

26,

27]. In addition, adaptive coping favor engagement and academic performance in university students [

28]. In contrast, avoidant coping strategies often involve maladaptive consequences for students [

29,

30], such as higher levels of interpersonal stress [

31] and burnout in university students [

32].

In sum, research concludes the clear relationship between coping strategies and the level of psychological well-being experienced by university students [

33]. However, it is necessary to determine the positive personal resources that have an effect in promoting adaptive coping strategies over maladaptive ones. It is also worth analyzing whether the relationship between personal resources and coping strategies affects the psychological well-being of university students.

1.3. Personal Resources: Psychological Capital

Psychological Capital (PsyCap) was proposed as a paradigmatic exponent of positive organizational behavior [

34]. PsyCap is comprised of four psychological resources, self-efficacy, hope, optimism, and resilience, which act synergistically to influence psychological well-being [

35]. Indeed, a recent meta-analysis [

36] evidenced that PsyCap correlates positively with desirable attitudes in the work environment, such as satisfaction and engagement. Moreover, PsyCap constitutes a robust predictor of job performance, given that it influences workers' adaptability, competence and proactivity. In contrast, PsyCap is negatively related to cynicism, stress and anxiety [

37].

Research agrees that PsyCap is also highly functional in the academic context. For example, some studies showed that PsyCap is a decisive mediator in the relationships between positive emotions [

38], academic engagement [

39], and the teacher-student relationship [

40] with academic performance. It was also evidenced that PsyCap directly influences performance [

41] and academic adjustment in the university stage [

42]. Moreover, PsyCap also emerged as a highly adaptive resource in terms of psychological well-being [

43,

44], In addition, PsyCap was shown to be a predictor for adaptive coping in university students [

45].

1.4. The Present Study

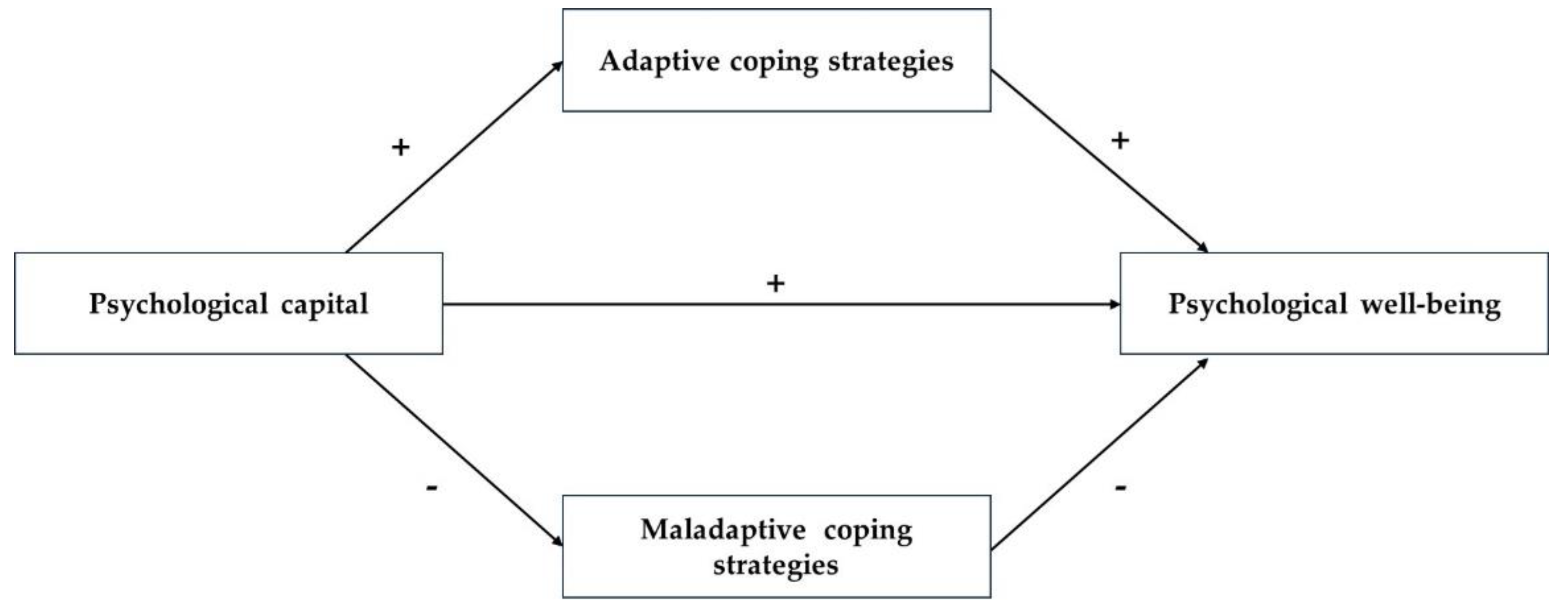

Research places PsyCap as a possible personal resource with great potential for the psychological well-being, although to date there is little existing evidence in university students. Moreover, at this academic stage students deal with numerous daily demands that may threaten their psychological well-being, requiring the use of adaptive coping strategies. Accordingly, and based on the reviewed studies, the present research aims to identify whether PsyCap and coping strategies function as personal resources for psychological well-being in university students. As specific objectives we propose to: a) Examine the relationship between PsyCap and psychological well-being; b) Determine the impact of PsyCap on coping strategies; c) Estimate the influence of coping strategies on psychological well-being; d) Analyze the mediating role of coping strategies in the relationship between PsyCap and psychological well-being. Based on the preceding research, the following hypotheses are put forward (see

Figure 1):

H1: PsyCap will show a direct positive effect on psychological well-being.

H2: PsyCap will exert a direct positive effect on adaptive coping strategies, as well as a direct negative effect on maladaptive coping strategies.

H3: Adaptive coping strategies will exert a direct positive effect on psychological well-being.

H4: Maladaptive coping strategies will exert a direct negative influence on psychological well-being.

H5: Coping strategies will partially mediate the relationship between PsyCap and psychological well-being.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

The number of participants was initially 438 students belonging to the University of A Coruña (Spain). After excluding random and incongruent participations (specifically those with a response time of less than 3 minutes or more than 40 minutes), the final sample consisted of 391 university students. The ages of male (24.30%; M = 24.44, SD = 6.68), female (71.61%; M = 23.46, SD = 6.25) and other genders (4.09%; M = 21.50, SD = 3.14) participants ranged from 18 to 59 years old.

The majority were undergraduate students belonging to the Social and Legal Sciences (n = 132, 33.76%), followed by Master's students (n = 103, 26.34%), Engineering and Architecture (n = 67, 17.13%), Health Sciences (n = 40, 10.23%), Experimental Sciences (n = 28, 7.16%), and Arts and Humanities (n = 21, 5.37%). Most of the participants were in their final year (n = 106, 27.11%), followed by first year (n = 89, 22.76%), second year (n = 49, 12.53%) and finally, third year (n = 46, 11.77%). In addition, most of the participants did not combine their studies with a job (n = 276, 70.59%), studied full-time (n = 348, 89%), did not receive a scholarship (n = 217, 55.50%) and had middle (n = 192, 49.11%) and lower middle (n = 125, 31.97%) socioeconomic status.

2.2. Instruments

The Psychological Capital in Academic Contexts Questionnaire (PCQ-12) was used to measure PsyCap. It is the adaptation of the original PCQ by Luthans et al. [

46], validated to the Spanish academic context by Martínez et al. [

47]. It is a self-administered instrument that aims to measure the four components of the PsyCap: self-efficacy (3 items), hope (4 items), resilience (3 items) and optimism (2 items). An example statement is "I feel confident sharing information about my studies with other people". For its scoring, a seven-option Likert scale was used, where participants rate their level of agreement or disagreement between 0 "Completely disagree" and 6 "Completely agree". For interpretation, the scores of each item are summed, such that the higher the score, the higher the level of academic PsyCap. In the present study, the questionnaire showed excellent psychometric properties, both in factorial validity (χ2 = 140.16; df = 49;

p < .05; GFI = .98; AGFI = .96; TLI = .93; CFI = .95; SRMR = .054; RMSEA = .07) and internal consistency (ω = .92; 95% CI [.90, .93])

Coping strategies were assessed using the Coping Strategies Inventory (CSI). It is the modified version adapted to Spanish by Cano et al. [

48] from the Coping Strategies Inventory [

49]. The instrument includes 40 items that measure the use of eight coping strategies (five items per strategy; e.g., "I went over the problem again and again in my mind and in the end, I saw things in a different way"). Four of the strategies are adaptive: problem solving (PSO), emotional expression (EEX), social support (SSU) and cognitive restructuring (CRE). The other four are maladaptive strategies: self-criticism (SCR), desiderative thinking (DTH), problem avoidance (PAV) and social withdrawal (SWI). The instrument is self-administered, using a Likert scale of five options, from 0 "Not at all" to 4 "Totally", in which the participants indicate the degree to which they used each strategy. The scores of the five items of each factor are added together, giving a minimum score of 0 and a maximum of 20. A higher score indicates a higher degree of the strategy under consideration. In the present study, both the factor structure of the model representing Adaptive Coping Strategies (PSO, EEX, SSU and CRE), and that of the model representing Maladaptive Coping Strategies (SCR, DTH, PAV and SWI), evidenced acceptable fits: χ2 = 512.391; df = 166;

p < .05; GFI = .94; AGFI = .92; TLI = .89; CFI = .90; SRMR = .08; RMSEA = .07; and χ2 = 512.391; df = 166;

p < .05; GFI = .93; AGFI = .90; TLI = .83; CFI = .85; SRMR = .09; RMSEA = .08, respectively. Regarding to internal consistency, adaptive coping strategies showed excellent values (ω = .90; 95% CI [.86, .91]) and maladaptive coping strategies achieved good scores (ω = .86; 95% CI [.84, .88]). Values for individual coping strategies were as follows: PSO (ω = .85; 95% CI [.82, .87]), SCR (ω = .88; 95% CI [.86, .90]), EEX (ω = .87; 95% CI [.85, .89]), DTH (ω = .84; 95% CI [.81, .87]), SSU (ω = .88; 95% CI [.86, .90]), CRE (ω = .83; 95% CI [.80, .86]), PAV (ω = .73; 95% CI [.69, .77]) and SWI (ω = .82; 95% CI [.79, .84]).

Psychological well-being was measured by means of the Flourishing Scale. The instrument was developed by Diener et al. [

50] and adapted to the Spanish context by Checa et al. [

51]. It consists of eight items that measure psychological well-being in various areas such as social relationships or daily activities (e.g., "I see my future with optimism"). The scale is self-administered and is scored on a seven-option Likert scale, with a range between 1 "Strongly disagree" and 7 "Strongly agree". It is scored by the sum of the answers in the eight items, which makes it possible to obtain a total of 56. The higher the score, the higher the level of well-being. In the present study, the psychometric properties of the scale were adequate in terms of factorial validity (χ2 = 65.97; df = 20;

p < .05; GFI = .99; AGFI = .99; TLI = .92; CFI = .94; SRMR = .042; RMSEA = .08) and internal consistency (ω = .86; 95% CI [.84, .88]).

2.3. Procedure

The research was conducted in accordance with the principles and standards established in the Declaration of Helsinki and the Code of Ethics of the University of A Coruña. The study was approved by the Academic Committee of the Master's Degree in Applied Psychology of the University of A Coruña. The data collection process was carried out between February and April 2024. The instruments were distributed through an online survey generated in Microsoft Forms. The link was shared through the students' institutional e-mail. The questionnaire included an informed consent section that provided students with details about the research and asked for voluntary participation, with a guarantee of anonymity and confidentiality in their responses. The average time to complete the survey was 13 minutes.

2.4. Data Analysis

The statistical analysis consisted of two sections. In the first section, the descriptive statistics of the study variables were calculated. Measures such as the arithmetic mean (

M) and standard deviation (

SD) were obtained. In addition, compliance with normality was assumed when the values of dispersion, skewness (g1) and kurtosis (g2), were in the range between [-1.5, +1.5] [

52]. For the analysis of coping strategies, the results were obtained for each individual strategy and for the groups of adaptive (consisting of PSO, EEX, SSU and CRE) and maladaptive (SCR, DTH, PAV and SWI) coping strategies. In this section we also obtained the Pearson correlation matrix between PsyCap, coping strategies and psychological well-being.

In the second section, a multiple mediation analysis was performed by constructing a Structural Equation Model (SEM). The Maximum Likelihood (ML) estimator and the Bootstrapped Confidence Intervals method of 5000 cases with a 95% confidence interval was used [

53]. In this SEM model, the direct effect of PsyCap on psychological well-being was estimated, as well as the indirect effect, through adaptive coping strategies and maladaptive coping strategies. All analyses were performed using the R programming language version 4.3.1. [

54] and the packages 'psych' [

55], 'Lavaan' [

56] and 'semhelpinghands' [

57].

In order to confirm the goodness of fit of the SEM model, the following parameters were taken into consideration [

58]: the fulfillment of non-significance (

p > .05) in the case of the Chi-square (ꭓ2); the attainment of values less than .08 in the Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA) and .06 in the Standardized Root Mean Residual (SRMR); and the attainment of values greater than .95 for the Comparative Fit Index (CFI) and the Tucker-Lewis Index (TLI).

3. Results

3.1. Descriptive Analyses

Table 1 shows the descriptive results of the variables. Apart from psychological well-being, all variables conformed to the assumption of normality in terms of skewness and kurtosis. The trend of PsyCap and psychological well-being toward the upper end of the range of possible responses suggests a moderate to high presence of these factors in the sample. Regarding coping strategies, the data indicate a pronounced tendency to use DTH (M = 13.88; SD = 4.67), followed by PSO (M = 12.31; SD = 4.17). In contrast, PAV (M = 7.37; SD = 4.44) and EEX (M = 9.68; SD = 4.96) were the least used coping strategies. In addition, the averages of adaptive coping strategies and maladaptive coping strategies were relatively similar, with a slight predominance of adaptive coping strategies (M = 43.86; SD = 13.89).

3.2. Correlational Analyses

Table 2 shows the results of the correlations between the variables assessed in the sample. The correlations between PsyCap and adaptive coping strategies were positive and significant (

p < .001), and ranged from

r(PsyCap – EEX) = .22 to

r(PsyCap – PSO) = .42. In addition, the association between PsyCap and the total construct of adaptive coping strategies was positive and moderate (

r(PsyCap – Adaptive Coping) = .43,

p < .001). On the other hand, the correlations between PsyCap and maladaptive coping strategies were inverse and significant (

p < .001), lying in the range between

r(PsyCap – DTH) = -.19 and

r(PsyCap – SCR) = -.34. The only non-significant relationship was with PAV (

r = -.05,

p = .30). As for the correlation between PsyCap and the total construct of maladaptive coping strategies, it was moderate and negative (

r(PsyCap – Maladaptive coping) = -.30,

p < .001). The correlation between PsyCap and psychological well-being (PWB) was significant, high and positive:

r(PsyCap – PWB) = .65,

p < .001.

Regarding the relationships between psychological well-being and coping strategies, all were significant (p < .001), except for the correlation with PAV (r = -.04, p = .46). Correlations with individual adaptive coping strategies ranged from r(PWB – EEX) = .23 to r(PWB – PSO and SSU) = .43. In the case of individual maladaptive strategies, the correlations were within the range r(PWB - DTH) = -.16 and r(PWB - SCR) = -.30. Accordingly, the association between psychological well-being and the total adaptive coping strategies factor was positive and moderate (r(PWB – Adaptive coping) = .51, p < .001). However, the correlation with the total factor of maladaptive coping strategies was inverse and low: r(PWB – Maladaptive coping) = -.27, p < .001.

3.3. Multiple Mediation Analysis

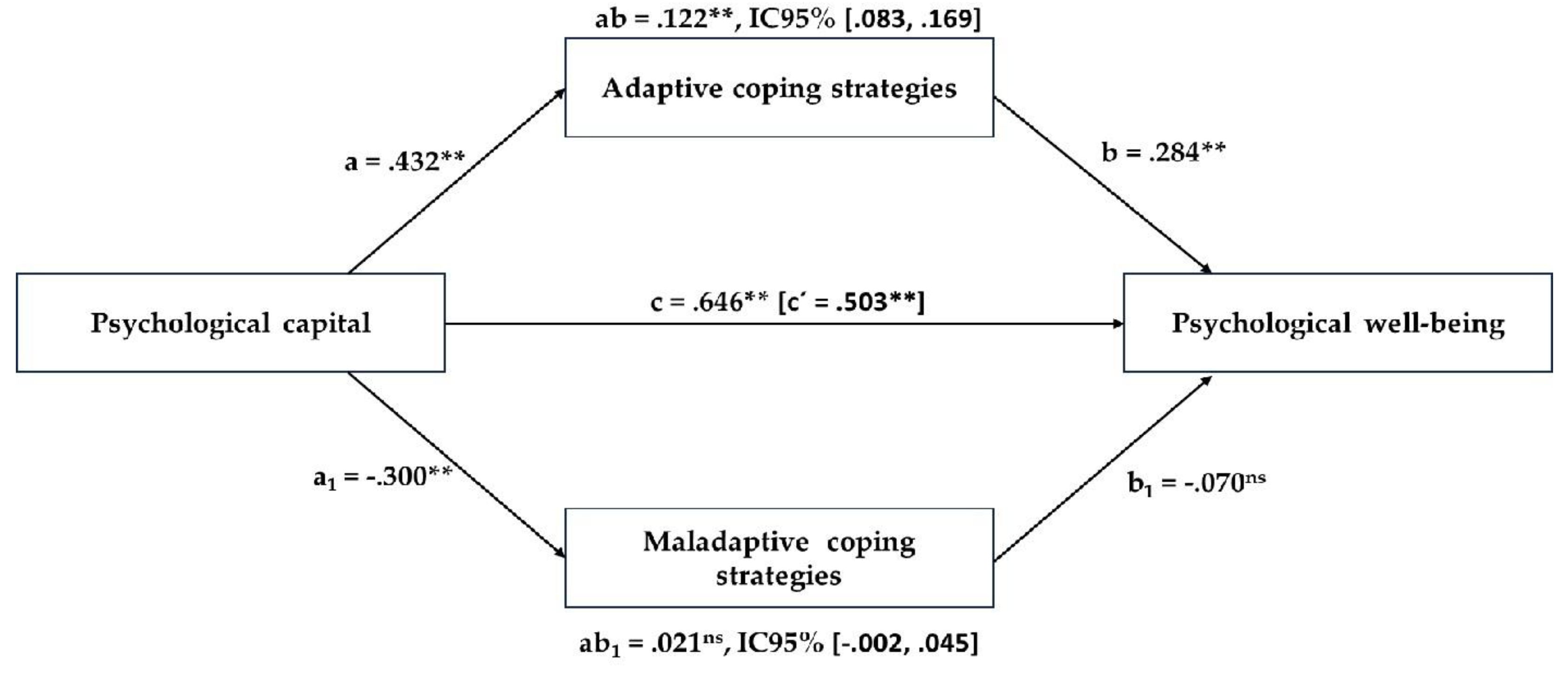

As indicated in

Table 3, PsyCap was shown to be a positive predictor of psychological well-being (

b = .646, 95% CI [.584, .701]). When analyzing indirect effects, the results indicated that adaptive coping strategies play a significant mediating role in the relationship between PsyCap and psychological well-being (

b = .122, 95% CI [.083, .169]). In contrast, the indirect effect through maladaptive strategies did not show statistical significance (

b = .021, 95% CI [-.002, .045]). PsyCap exhibited a positive and significant direct influence on adaptive coping strategies (

b = .432, 95% CI [.342, .517]). Conversely, PsyCap showed a negative and significant relationship with maladaptive coping strategies (

b = -.300, 95% CI [-.392, -.202]).

Also, adaptive coping strategies contributed directly and positively to psychological well-being (b = .284, 95% CI [.214, .355]), whereas maladaptive coping strategies did not show a significant direct effect (b = -.070, 95% CI [-.146, .006]). Finally, the findings suggest that the mediating effect of coping strategies was partial, because PsyCap exerted its direct positive influence on psychological well-being even after accounting for indirect pathways (b = .503, 95% CI [.424, .576]).

The proposed SEM model is shown graphically in

Figure 2. The fit indices indicate that the model is adequate (ꭓ2(1) = 1.301;

p > .05, RMSEA = .028; SRMR = .016, CFI = .99; TLI = .99). As in

Table 3, it is observed that the mediation of coping strategies is partial.

4. Discussion

The aim of the present research was to analyze the relationship between PsyCap, coping strategies and psychological well-being in university students. Specifically, it was explored whether the effect of PsyCap on psychological well-being was partially mediated by coping strategies.

Consistent with the first hypothesis, the results evidenced that PsyCap exerts a direct positive effect on psychological well-being. In other words, the availability of high standards of hope, optimism, self-efficacy, and resilience favors students to experience their day-to-day life in terms of flourishing. These findings validate the theoretical basis of PsyCap, which is characterized by its significant positive impact on psychological well-being [

34], and are consistent with studies highlighting the positive association between PsyCap and subjective and psychological well-being among students [

43,

44,

59].

The results also confirmed the second hypothesis, whereby it was expected that PsyCap would show a direct positive effect on adaptive coping strategies, as well as a direct negative effect on maladaptive coping strategies. This finding seems to indicate that, the higher the PsyCap of university students, the greater their tendency to cope with diverse and heterogeneous daily demands by using adaptive strategies, such as problem solving, positive reappraisal, emotional expression, or seeking social support. At the same time, a high PsyCap level decreases the recurrent use of maladaptive strategies in the face of daily stressors (self-criticism, desiderative thinking, problem avoidance, social isolation). Thus, these results align with the scarce previous existing evidence regarding the positive relationship between PsyCap and adaptive coping strategies in university students [

41,

45]. They also endorse the inverse relationship between PsyCap and use of maladaptive coping strategies, evidenced in the work context [

60,

61,

62]. Based on these findings, PsyCap appears to stand as an important personal resource in the face of the daily demands of university students, given that, not only does it promote the use of adaptive strategies, but it decreases the likelihood of resorting to dysfunctional strategies.

As a third hypothesis, the present study postulated that adaptive coping strategies would exert a direct positive effect on psychological well-being. The results obtained ratified this expectation, so that, in line with the findings of other studies [

26,

27], the valuable role played by adaptive coping with stress on students' psychological well-being seems to be confirmed. However, contrary to expectations, our fourth hypothesis did not obtain empirical endorsement. Indeed, we found no significant influence (neither positive nor negative) of maladaptive coping strategies on psychological well-being. This suggests that the use of dysfunctional coping strategies in dealing with stressful situations does not have a direct impact on psychological well-being. Although studies such as Rabenu et al. [

60] already concluded the absence of a significant effect of avoidance strategies on workers' psychological well-being, this finding could have a possible explanation. In this way, it is necessary to consider that well-being is not equivalent to the absence of ill-being [

63]. Therefore, it cannot be ruled out that the frequent use of maladaptive coping strategies is related to the experience of distress in the long term, as indicated by some studies [

64].

Finally, the fifth hypothesis was only partially confirmed, since we found a mediation effect of adaptive coping strategies (but not of maladaptive strategies) on the relationship between PsyCap and psychological well-being. According to this result, high levels of PsyCap lead to a greater use of adaptive coping strategies, which allows one to effectively manage and overcome stressful circumstances and, consequently, to experience high psychological well-being. To the best of our knowledge, this finding is unpublished in students, although it is consistent with those of other research with occupational samples [

60,

62]. Our results also align with those of Wang et al. [

65], who established that PsyCap and positive reappraisal (an adaptive coping strategy) mediate the relationship between family support and psychological well-being.

The research conducted has implications of theoretical and applied relevance. From the theoretical point of view, it seems to endorse the proposition that positive personal resources (in this case, the PsyCap components —optimism, hope, resilience and self-efficacy— and adaptive coping strategies) function as mechanisms that improve the psychological well-being of university students. This finding would be consistent with the Conservation of Resources (COR) Theory, which suggests that people tend to acquire and conserve personal resources, as their accumulation decreases the impact of stress [

66]. In this context, the resources that form the PsyCap not only promote the adoption of adaptive coping strategies to deal with stressful situations, but also appear to function as a reservoir of resources that protect psychological well-being. From a practical standpoint, the findings of this study suggest that interventions focused on PsyCap components and adaptive coping strategies could have positive effects on the psychological well-being of university students. These types of interventions have already evidenced their effectiveness in both work [

34] and academic [

67] contexts.

Without underestimating its relevance, the results of the present study should be considered in the light of its limitations. First, the sample was not selected by a probabilistic method and was concentrated only on students from one Spanish university. This makes it difficult to generalize the findings to the entire population of university students. Therefore, future research should replicate the results of the present study using more rigorous sampling procedures and in other cultural contexts. Second, the cross-sectional nature of the study does not allow the establishment of causal relationships between variables. Thus, longitudinal research analyzing the long-term influence of PsyCap and coping strategies on the psychological well-being of university students is needed. Finally, the use of self-reported instruments may introduce biases in the results (e.g., social desirability, overestimation, or underestimation of behavior).

5. Conclusions

According to the results of the present study, PsyCap demonstrates a direct and indirect positive effect (through adaptive coping strategies) on psychological well-being. Furthermore, PsyCap shows a direct positive influence on adaptive coping strategies and a negative effect on maladaptive coping strategies. The latter do not exert a direct effect on psychological well-being, nor do they function as mediators. Therefore, it is concluded that PsyCap stands as a valuable positive personal resource that improves and strengthens psychological well-being in university students. Similarly, the use of adaptive coping strategies such as problem solving, emotional expression, seeking social support and cognitive restructuring contribute to improving psychological well-being.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, E.M., M.M.F. and C.F.; methodology, E.M. and C.F.; formal analysis, E.M.; investigation, E.M., M.M.F. and C.F.; resources, M.M.F.; data curation, E.M. and C.F.; writing—original draft preparation, E.M. and C.F.; writing—review and editing, E.M., M.M.F. and C.F.; supervision, M.M.F. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Academic Committee of the Master's Degree in Applied Psychology of the University of A Coruña (MUPA/2024/01/29).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Data Availability Statement: The study data are available in the Zenodo repository (10.5281/zenodo.12774887). The dataset can be accessed upon request to the contact author of the manuscript. The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Ballester, L.; Alayo, I.; Vilagut, G.; Almenara, J.; Cebrià, A.I.; Echeburúa, E.; Gabilondo, A.; Gili, M.; Lagares, C.; Piqueras, J.A.; Roca, M.; Soto-Sanz, V.; Blasco, M.J.; Castellví, P.; Mortier, P.; Bruffaerts, R.; Auerbach, R.P.; Nock, M.K.; Kessler, R.C.; Jordi, A. Mental disorders in Spanish university students: Prevalence, age-of-onset, severe role impairment and mental health treatment. J. Affect. Disord., 2020, 273, 604–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramón-Arbués, E.; Gea-Caballero, V.; Granada-López, J.M.; Juárez-Vela, R.; Pellicer-García, B.; Antón-Solanas, I. The prevalence of depression, anxiety and stress and their associated factors in college students. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health, 2020, 17, 7001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chang, J.-J.; Ji, Y.; Li, Y.-H.; Pan, H.-F.; Su, P.-Y. Prevalence of anxiety symptom and depressive symptom among college students during COVID-19 pandemic: A meta-analysis. J. Affect. Disord., 2021, 292, 242–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, W.; Zhao, Z.; Chen, D.; Peng, Y.; Lu, Z. Prevalence and associated factors of depression and anxiety symptoms among college students: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Child Psychol. Psych., 2022, 63, 1222–1230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kandasamy, N.; Kolandaisamy, I.; Tukiman, N.A.; Khalil Kusairi, F.W.K.; Sjarif, S.I.A.; Shahrul Nizar, M.S.S. Factors that influence mental illness among students in public universities. J. Bus. Econ. Anal., 2020, 3, 77–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spence, R.; Kagan, L.; Nunn, S.; Bailey-Rodriguez, D.; Fisher, H.L.; Hosang, G.M.; Bifulco, A. Life events, depression and supportive relationships affect academic achievement in university students. J. Am. Coll. Health, 2022, 70, 1931–1935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Galve-González, C.; Bernardo, A.B.; Núñez, J.C. Academic trajectories: The role of engagement as a mediator in the decision of university dropout or persistence. Rev. Psicodidact., 2024, 29, 130–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lorenzo-Quiles, O.; Galdón-López, S.; Lendínez-Turón, A. Factors contributing to university dropout: A review. Front. Educ., 2023, 8, 1159864. [Google Scholar]

- Ryan, R.M.; Deci, E.L. On happiness and human potentials: A review of research on hedonic and eudaimonic well-being. Annu. Rev. Psychol., 2001, 52, 141–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diener, E.; Oishi, S.; Tay, L. Advances in subjective well-being research. Nat. Hum. Behav., 2018, 2, 253–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryff, C.D.; Singer, B.H. Know thyself and become what you are: A eudaimonic approach to psychological well-being. J. Happiness Stud., 2008, 9, 13–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryff, C.D.; Singer, B. Interpersonal flourishing: A positive health agenda for the new millennium. In Personality and Social Psychology at the Interface: New Directions for Interdisciplinary Research; Brewer, M.B., Ed.; Psychology Press: New York, United States of America, 2014; pp. 30–44. [Google Scholar]

- VanderWeele, T.J. On the promotion of human flourishing. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci., 2017, 114, 8148–8156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Agenor, C.; Conner, N.; Aroian, K. Flourishing: An evolutionary concept analysis. Issues Ment. Health Nurs., 2017, 38, 915–923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keyes, C.L.M. The mental health continuum: From Languishing to Flourishing in life. J. Health Soc. Behav., 2002, 43, 207–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lomas, T.; Pawelski, J.O.; VanderWeele, T.J. A flexible map of flourishing: The dynamics and drivers of flourishing, well-being, health, and happiness. Int. J. Wellbeing, 2023, 13, 3665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Datu, J.A.D. Flourishing is associated with higher academic achievement and engagement in Filipino undergraduate and high school students. J. Happiness Stud., 2018, 19, 27–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Datu, J.A.D.; Labarda, C.E.; Salanga, M.G.C. Flourishing is associated with achievement goal orientations and academic delay of gratification in a collectivist context. J. Happiness Stud., 2020, 21, 1171–1182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howell, A.J. Flourishing: Achievement-related correlates of students’ well-being. J. Posit. Psychol., 2009, 4, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, K.K.S.; Lee, J.C.-K.; Yu, E.K.W.; Chan, A.W.Y.; Leung, A.N.M.; Cheung, R.Y.M.; Li, C.W.; Kong, R.H.M.; Chen, J.; Wan, S.L.Y.; Tang, C.H.Y.; Yum, Y.N.; Jiang, D. : Wang, L.; Tse, C.Y. The impact of Compassion from others and Self-compassion on psychological distress, Flourishing, and Meaning in Life among university students. Mindfulness, 2022, 13, 1490–1498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirshberg, M.J.; Colaianne, B.A.; Greenberg, M.T.; Inkelas, K.K.; Davidson, R.J.; Germano, D.; Dunne, J.D.; Roeser, R.W. Can the academic and experiential study of Flourishing improve Flourishing in college students? A multi-university study. Mindfulness, 2022, 13, 2243–2256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazarus, R.S.; Folkman, S. Stress, Appraisal, and Coping, 2nd ed.; Springer: New York, United States of America, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Zimmer-Gembeck, M.J.; Skinner, E.A. The development of coping: Implications for psychopathology and resilience. In Developmental Psychopathology: Risk, resilience, and intervention, 3rd Edition; Cicchetti, D., Ed.; John Wiley & Sons: New York, United States of America, 2016; pp. 485–545. [Google Scholar]

- Gustems-Carnicer, J.; Calderón, C.; Calderón-Garrido, D. Stress, coping strategies and academic achievement in teacher education students. Eur. J. Teach. Educ., 2019, 42, 375–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Syed, M.; Seiffge-Krenke, I. Change in ego development, coping, and symptomatology from adolescence to emerging adulthood. J. Appl. Dev. Psychol., 2015, 41, 110–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freire, C.; Ferradás, M.M.; Núñez, J.C.; Valle, A.; Vallejo, G. Eudaimonic well-being and coping with stress in university students: The mediating/moderating role of Self-Efficacy. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health, 2019, 16, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sagone, E.; Caroli, M.E.D. A correlational study on dispositional resilience, psychological well-being, and coping strategies in university students. Am. J. Educ. Res., 2014, 2, 463–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vizoso, C.; Rodríguez, C.; Arias-Gundín, O. Coping, academic engagement and performance in university students. High. Educ. Res. Dev., 2018, 37, 1515–1529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deasy, C.; Coughlan, B.; Pironom, J.; Jourdan, D.; Mannix-McNamara, P. Psychological Distress and Coping amongst Higher Education Students: A Mixed Method Enquiry. PLOS ONE, 2014, 9, e115193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Skinner, E.A.; Pitzer, J.R.; Steele, J.S. Can student engagement serve as a motivational resource for academic coping, persistence, and learning during late elementary and early middle school? Dev. Psychol., 2016, 52, 2099–2117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coiro, M.J.; Bettis, A.H.; Compas, B.E. College students coping with interpersonal stress: Examining a control-based model of coping. J. Am. Coll. Health, 2017, 65, 177–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vizoso, C.; Arias-Gundín, O.; Rodríguez, C. Exploring coping and optimism as predictors of academic burnout and performance among university students. Educ. Psychol., 2019, 39, 768–783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatfield, S.L.; Bista, S.; DeBois, K.A.; Kenne, D.R. The association between coping strategies, resilience, and flourishing among students at large U.S. university during the COVID-19 pandemic: A mixed methods research study. Build. Health Acad. Communities J., 2022, 6, 27–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luthans, F.; Youssef-Morgan, C.M. Psychological capital: An evidence-based positive approach. Annu. Rev. Organ. Psychol. Organ. Behav., 2017, 4, 339–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luthans, F.; Avolio, B.J. Brief summary of Psychological Capital and introduction to the special Issue. J. Leadersh. Organ. Stud., 2014, 21, 125–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donaldson, S.I.; Chan, L.B.; Villalobos, J.; Chen, C.L. The generalizability of HERO across 15 nations: Positive Psychological Capital (PsyCap) beyond the US and other WEIRD countries. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health, 2020, 17, 9432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Avey, J.B.; Reichard, R.J.; Luthans, F.; Mhatre, K.H. Meta-analysis of the impact of positive psychological capital on employee attitudes, behaviors, and performance. Hum. Resour. Dev. Q., 2011, 22, 127–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carmona-Halty, M.; Salanova, M.; Llorens, S.; Schaufeli, W.B. Linking positive emotions and academic performance: The mediated role of academic psychological capital and academic engagement. Curr. Psychol., 2021, 40, 2938–2947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez, I.M.; Youssef-Morgan, C.M.; Chambel, M.J.; Marques-Pinto, A. Antecedents of academic performance of university students: Academic engagement and psychological capital resources. Educ. Psychol., 2019, 39, 1047–1067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carmona–Halty, M.; Salanova, M.; Llorens, S.; Schaufeli, W.B. How Psychological Capital mediates between study–related positive emotions and academic performance. J. Happiness Stud., 2019, 20, 605–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortega-Maldonado, A.; Salanova, M. Psychological capital and performance among undergraduate students: The role of meaning-focused coping and satisfaction. Teach. High. Educ., 2018, 23, 390–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hazan Liran, B.; Miller, P. The role of Psychological Capital in academic adjustment among university students. J. Happiness Stud., 2019, 20, 51–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prasath, P.R.; Mather, P.C.; Bhat, C.S.; James, J.K. University student well-being during COVID-19: The role of psychological capital and coping strategies. Prof. Couns., 2021, 11, 46–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selvaraj, P.R.; Bhat, C.S. Predicting the mental health of college students with psychological capital. J. Ment. Health, 2018, 27, 279–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramírez-Pérez, M.A. The relationship between academic psychological capital and academic coping stress among university students. Ter. Psicol., 2022, 40, 279–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luthans, F.; Avolio, B.J.; Avey, J.B.; Norman, S.M. Positive Psychological Capital: Measurement and relationship with performance and satisfaction. Pers. Psychol., 2007, 60, 541–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez, I.M.; Meneghel, I.; Carmona-Halty, M.; Youssef-Morgan, C.M. Adaptation and validation to Spanish of the Psychological Capital Questionnaire–12 (PCQ–12) in academic contexts. Curr. Psychol., 2021, 40, 3409–3416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cano, F.J.; Rodríguez, L.; Martínez, J. Spanish version of the Coping Strategies Inventory. Actas Esp. Psiquiatr., 2007, 35, 29–39. [Google Scholar]

- Tobin, D.L.; Holroyd, K.A.; Reynolds, R.V.; Wigal, J.K. The hierarchical factor structure of the coping strategies inventory. Cognitive Ther. Res., 1989, 13, 343–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diener, E.; Wirtz, D.; Tov, W.; Kim-Prieto, C.; Choi, D.; Oishi, S.; Biswas-Diener, R. New Well-being measures: Short scales to assess Flourishing and Positive and Negative Feelings. Soc. Indic. Res., 2010, 97, 143–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Checa, I.; Perales, J.; Espejo, B. Spanish Validation of the Flourishing Scale in the general population. Curr. Psychol., 2018, 37, 949–956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Hult, G.T.M.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M. A Primer on Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM), 3rd ed.; SAGE Publications: Thousand Oaks, United States of America, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Hayes, A.F. Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: A regression-based approach. Guilford Press: New York, United States of America, 2013.

- R: A language and environment for statistical computing. Available online: https://www.r-project.org/ (accessed on 28 March 2024).

- Psych: Procedures for Psychological, Psychometric, and Personality Research. Northwestern University. Available online: https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=psych (accessed on 31 March 2024).

- Rosseel, Y. Lavaan: An R Package for Structural Equation Modeling. J. Stat. Softw., 2012, 48, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Semhelpinghands: Helper functions for Structural Equation Modeling. Available online: https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=semhelpinghands (accessed on 31 March 2024).

- Kline, R.B. Principles and practice of structural equation modeling, 4th ed.; Guilford Press: New York, United States of America, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, P.-L. Comparison of psychological capital, self-compassion, and mental health between with overseas Chinese students and Taiwanese students in the Taiwan. Pers. Indiv. Differ., 2021, 183, 111131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rabenu, E.; Yaniv, E.; Elizur, D. The relationship between psychological capital, coping with stress, well-being, and performance. Curr. Psychol., 2017, 36, 875–887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, Q.; Zhang, L. Research on psychological capital of college graduates: The mediating effect of coping styles. Adv. Soc. Sci. Educ. Humanit. Res., 2016, 85, 1639–1645. [Google Scholar]

- Zewude, G.T.; Hercz, M. Psychological capital and teacher well-being: The mediation role of coping with stress. Eur. J. Educ. Res., 2021, 10, 1227–1245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, M.Y.; Tay, L. From ill-being to well-being: Bipolar or bivariate? J. Posit. Psychol., 2023, 18, 649–659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skinner, E.A.; Edge, K.; Altman, J.; Sherwood, H. Searching for the structure of coping: A review and critique of category systems for classifying ways of coping. Psychol. Bull., 2003, 129, 216–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, H.; Ng, T.K.; Siu, O.-L. How does psychological capital lead to better well-being for students? The roles of family support and problem-focused coping. Curr. Psychol., 2023, 42, 22392–22403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hobfoll, S.E. Conservation of resources: A new attempt at conceptualizing stress. Am. Psychol., 1989, 44, 513–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shatkin, J.P.; Diamond, U.; Zhao, Y.; DiMeglio, J.; Chodaczek, M.; Bruzzese, J.-M. Effects of a risk and resilience course on stress, coping skills, and cognitive strategies in college students. Teach. Psychol., 2016, 43, 204–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).