1. Introduction

Significant advances, leading to the reduction of patient disability, have been made in ischemic stroke treatment over the past two to three decades. Alteplase, a tissue plasminogen activator, has been demonstrated to be effective in dissolving blood clots and restoring blood flow when administered early, thereby reducing long-term disability in stroke patients since its introduction in the mid-1990s [

1]. Additionally, mechanical treatment with endovascular thrombectomy (EVT) has been found to be beneficial in improving functional outcomes and reducing mortality in stroke cases, as evidenced by a series of randomized clinical trials in 2015 [

2]. However, the effectiveness of both treatments is highly time-dependent [

3,

4], as treatment with alteplase should begin within 30 minutes (median) of arrival at the hospital [

5,

6], and EVT should be started within 60 minutes (median) from hospital arrival. Treatment of Acute Ischemic Stroke (AIS) with both treatments is a complex process integrating the efforts of various hospital departments and multidisciplinary healthcare professionals. Improving stroke treatment efficiency [

7,

8] and increasing the proportion of ischemic stroke patients that receive treatment [

9,

10,

11] have been effortful endeavours for several decades.

Quality Improvement Collaboratives (QICs) [

12] are widely used to improve healthcare processes and patient outcomes. The first steps in Quality Improvement Collaboratives were taken by the Northern New England Cardiovascular Disease Study Group in 1986 and the Vermont Oxford Network in 1988 [

13]. The Institute for Healthcare Improvement added to this in 1995 with its Breakthrough Series [

14]. The purpose of QICs is to make improvements across multiple facilities, or specifically in this study, across multiple hospitals. The original IHI White Paper on the Breakthrough Series Collaborative Model had specified a 1-year long duration; however, in practice, the duration of this model varies. The year-long project consists of the following: recruitment of improvement teams at each site, three 2-day Learning Sessions, three Action Periods, and a closing congress. The Action Periods follow each Learning Session, which are spaced 4 months apart. Several publications address the effectiveness of QICs [

12,

15]. The QIC methodology has previously been used to improve acute stroke treatment processes with varying success [

16,

17,

18].

This study evaluates the efficacy of the modified Quality Improvement Collaborative (mQIC) in Nova Scotia (Canada) using the Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research (CFIR) [

19], which provided a clear framework for the evaluation. The primary research question guiding this study is: "What are the barriers and facilitators within each CFIR construct reported by the participants of an mQIC during an initiative to improve stroke care in the Canadian province of Nova Scotia?" Correspondingly, the aim of this study is to explore the barriers and facilitators impacting the implementation of the mQIC and how they influence stroke care in Nova Scotia.

2. Materials and Methods

This project used a mQIC that enrolled all stroke hospitals in the Canadian province of Nova Scotia. The mQIC for Nova Scotia has been described in detail previously [

20]. Briefly, the mQIC was 6 months long, and prior to the start of the mQIC, all stroke hospitals in the province assembled and enrolled teams to the mQIC; the teams were made of representatives from key professions involved in the treatment process including emergency physicians, emergency department nurses, radiologists, CT technologists, administrators, paramedics, and stroke coordinators. There were 2 full-day workshops, and the mQIC began at the first workshop and the second workshop was held approximately 2 months after the first one. The first workshop focused on presenting the evidence for alteplase treatment, EVT, and imaging for acute stroke and the second workshop focused on hearing about improvements from participating teams. Both workshops provided time for each team to plan their changes (action planning), which was reported back to the entire group. The teams were supported throughout the 6 months with site visits and webinars.

An mQIC has been conducted across the province of Nova Scotia through the ACTEAST (Atlantic Canada Together Enhancing Acute Stroke Treatment) project [

21]. Nova Scotia is a small Canadian Province of around 1 million people on the Atlantic Coast. In Nova Scotia, efforts have been dedicated to improving stroke treatment outcomes since 2005 [

22]. However, further improvements across the province were still needed to meet Canadian Best Practice guidelines for treatment of AIS. Specifically, prior to the start of this project, the median door-to-needle time (DNT) for alteplase treatment was nearly double the benchmark 30 minutes [

6] and patients outside the main city, Halifax, had poorer access to endovascular treatment. Nova Scotia has 10 designated stroke hospitals, and all suspected stroke patients are taken to one of these hospitals within 12 hours of onset by paramedics.

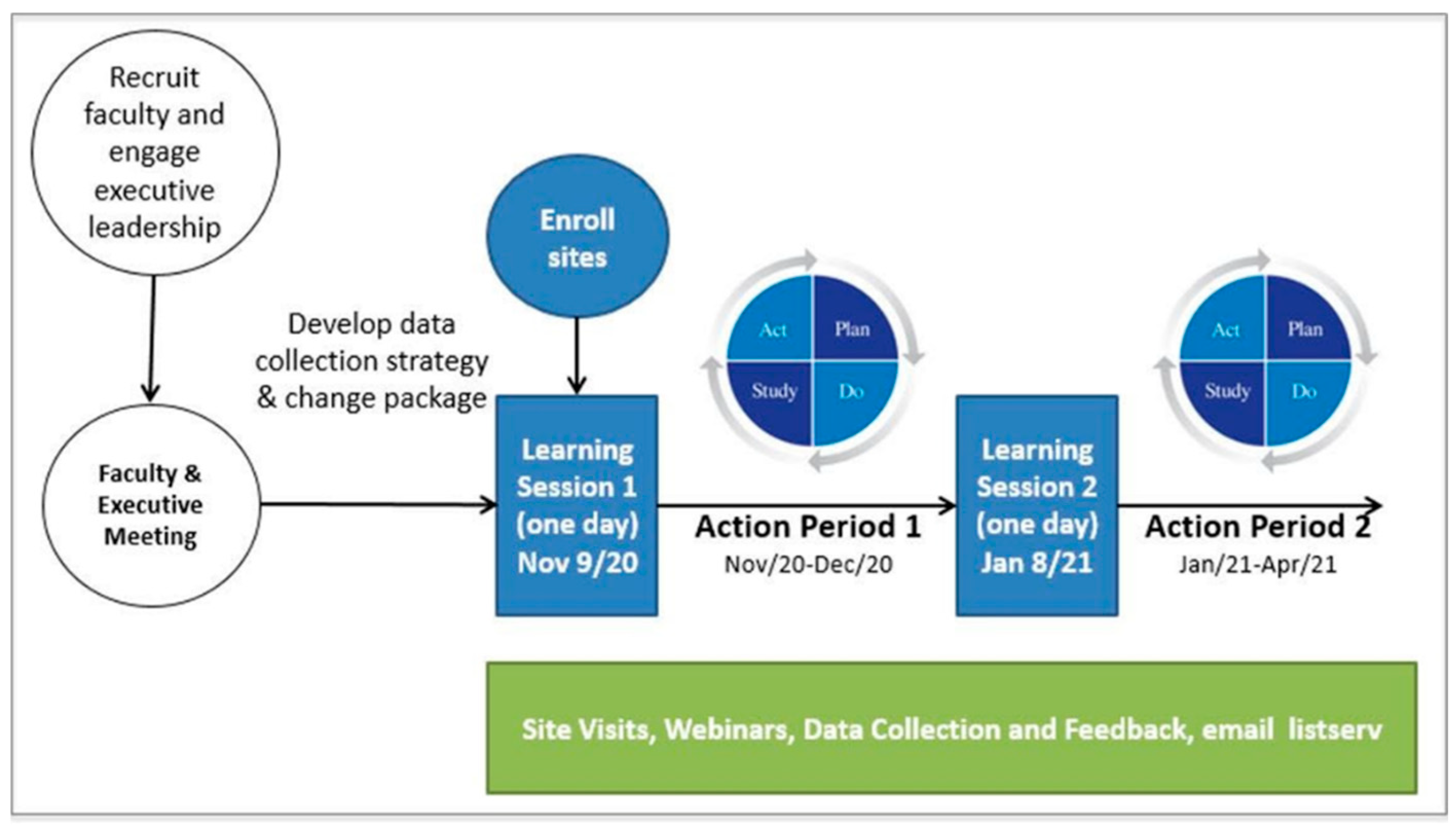

Figure 1 illustrates the mQIC in Nova Scotia under the ACTEAST initiative. Out of the eleven hospitals in the region, ten participated, with the exception being one of the smallest rural stroke centers. Two additional teams joined the mQIC: a team representing an additional urban hospital that receives many stroke patients arriving by private vehicle and provides alteplase treatment, and a team to represent the provincial ambulance service, Emergency Health Services (EHS) Nova Scotia.

A total of 98 healthcare professionals from Nova Scotia participated in the mQIC; 73 fully consented to the research study. The first Learning Session was held on November 9, 2020, in a hybrid fashion (in-person and virtual). All remaining sessions, including the second Learning Session (held on January 8, 2021), webinars, and site visits with each participating team, were held virtually. All virtual interactions were delivered using Zoom (Zoom Video Communications, v. 5.11.0, San Jose, CA, USA). The reason for moving all aspects to Zoom was due to the COVID-19 pandemic.

Implementation of the mQIC was evaluated using a validated framework called the Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research (CFIR) for the implementation of best practices. CFIR is an implementation science framework that integrates several implementation research theories [

19] and outlines key factors that can influence implementation. The CFIR is comprised of 39 constructs grouped under five domains, including innovation characteristics, outer setting characteristics, inner setting characteristics, individual characteristics, and process characteristics. CFIR was used to understand better the barriers and facilitators for implementing acute stroke treatment best practices using an mQIC in Nova Scotia and to help us evaluate the ability of the mQIC to implement stroke treatment best practices [

23].

Semi-structured interviews were conducted with participants from the ACTEAST's Nova Scotia mQIC after completion of the 6-month improvement collaborative. The evaluation team created and pre-tested a CFIR-based [

24] semi-structured interview guide of 35 main questions. The interview guide was pre-tested by a medical staff member who was previously involved in QuICR [

16], a similar initiative conducted between 2015 and 2017 in Alberta, Canada. Based on pre-testing findings and user feedback, the evaluation team edited the interview guide for language and question sequencing. The interview guide can be found in Supplementary Material 1. The interview guide was sent to all interviewees a couple of days before the interview date as part of a reminder email.

The interviews were conducted from June 2021 to October 2021. Participants were recruited from the mQIC cohort. An initial email invitation was sent to all mQIC participants, inviting them to participate in the interview. Interviews were conducted with those who volunteered in response to the email. Additionally, targeted outreach was performed to selected individuals who either played a significant role in the project or represented a category of participants that was underrepresented among the volunteers. This dual approach to recruitment, general invitation and targeted outreach ensured a diverse and comprehensive set of participants, thereby enriching the quality and scope of the data collected.

For the data collection phase, all interviews were conducted by one team member (SA), except the first interview, which two team members (SA & KM) conducted to ensure the interview guide matched the team’s and users’ expectations. As part of the initiative, SA participated in several ACTEAST Planning Meetings for Investigators and Collaborators during the project’s time. These virtual meetings included some of the interviewees. Accordingly, those participants who attended these meetings may have known the interviewer's role in the project.

Framework Analysis was employed as our analytical approach, aligning well with the CFIR framework. This method allows for a systematic yet flexible approach to qualitative data analysis, which corresponds with CFIR's comprehensive and multi-level understanding of implementation contexts [

25]. Framework Analysis involves a structured process of data management and interpretation, including familiarization with the data, identifying a thematic framework, indexing, charting, and mapping and interpretation [

26]. This systematic approach mirrors CFIR's structured method of categorizing and analyzing multiple implementation constructs across various domains [

19]. The use of Framework Analysis guided by CFIR enabled us to apply pre-existing constructs while remaining open to emerging themes, thus capturing both anticipated and unforeseen factors influencing implementation [

27]. This method allowed for a nuanced examination of our data, facilitating the identification of key barriers and facilitators to implementation within the CFIR's comprehensive framework.

Due to the constraints imposed by the COVID-19 pandemic, the interviews were conducted virtually, as it was the only viable option at the time. SA conducted the interviews from his home office, while the participants joined from various locations, predominantly their own offices. Recorded interviews were conducted through Zoom and transcribed verbatim. Field notes were taken by SA during all interviews. Transcripts were cleaned, de-identified and coded in a line-by-line fashion in NVivo 12 using a pre-defined, deductive CFIR framework codebook (

Table 1) [

24]. Each coded segment was first identified as either a facilitator or a barrier to implementation. Coding went through several iterations among all three authors (SA, KM and NK) to reach a consensus within the qualitative evaluation team. It should be noted that transcripts were not returned to participants for verification, given that they were already burdened by the demands of the COVID-19 pandemic. In addition, participants were not consulted for feedback on the findings for the same reason.

To support the rigor and validity of our findings, we used a methodological approach that included iterative coding and team discussions, with a CFIR framework codebook guiding the coding process. The main author (SA) focused solely on the qualitative evaluation of the mQIC, handling tasks from recruiting interviewees to conducting analysis, separate from the mQIC's design and implementation. This distinction ensured a rigor or trustworthy evaluation of the outcomes. NK implemented the mQIC intervention but did not participate in data collection or analysis for this study. Similarly, KM had no involvement with the mQIC intervention or its components. This separation of roles provided a clear demarcation between the mQIC intervention and the qualitative study, minimizing the risk of bias.

3. Results

Overall, there were 14 interview participants recruited (14.3% of total participants and 19.2% of consented participants) from the ACTEAST Nova Scotia mQIC. The limited number of interview participants may be attributed to the constraints imposed by the COVID-19 pandemic, which affected the availability and willingness of potential participants to engage in interviews. Detailed information about the 98 participants of the mQIC can be found in [

20]. Interviewees’ professions were distributed as follows: 29% were stroke coordinators, 29% were physicians, 21% worked in diagnostic imaging technologists and managers, and 21% were other professions such as paramedics and administrators; 64% of interviewees were women. Participants’ site’s size representation was 36% rural hospitals, 36% community hospitals, 14% large tertiary care hospitals and 14% reported no association with a specific hospital (e.g., including paramedics and provincial-level administrators). Interviews varied in length from 22 minutes to 52 minutes (mean= 35.99, SD= 9.57).

In this study, we used the CFIR framework for its comprehensive examination of constructs relevant to implementation research. Given CFIR's exhaustive nature and our limited number of interviewees, traditional data saturation was not our primary focus. This approach is justifiable because CFIR is primarily used to identify factors influencing implementation outcomes rather than generating new theories [

25]. As such, it provides a pre-defined set of constructs that guide data collection and analysis. Our primary goal was to identify key implementation factors and draw meaningful conclusions about our implementation context [

28].

After line-by-line data capture of barrier-facilitator references for each interview, we identified 454 references and coded these by their CFIR domains.

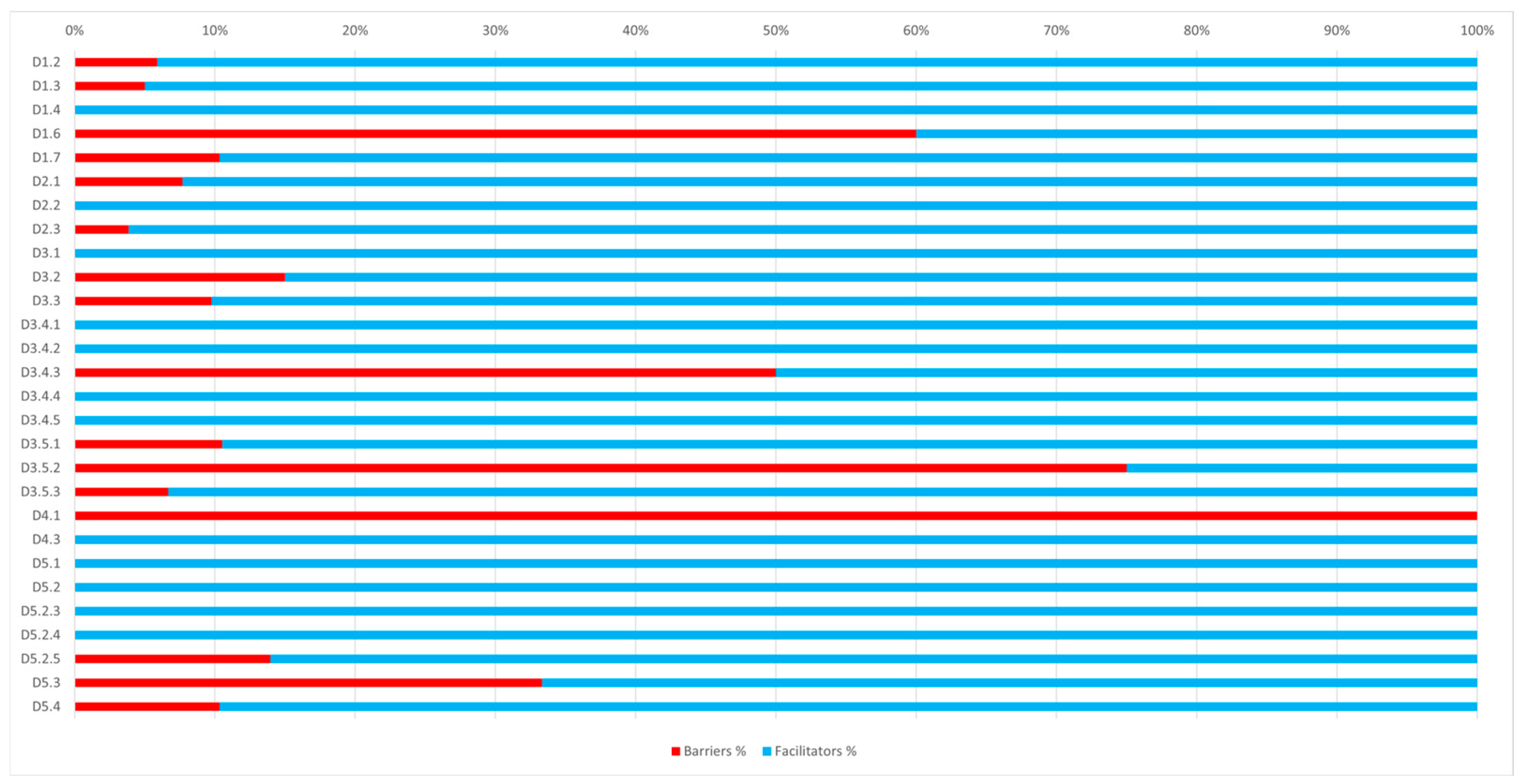

Table 2 summarizes the results of the qualitative analysis regarding the frequencies of barriers and facilitators influencing implementation. The analysis of the interview references shows that reported facilitators far outweighed barriers (384 facilitators to 74 barriers). Facilitators were mainly clustered in decreasing order of frequency in the following domains: Inner Setting> Process > Intervention Characteristics> Outer Setting Characteristics> Innovation Characteristics> Individual Characteristics (D3>D5>D2>D1>D4). The interviews revealed a general, positive disposition of participants toward the mQIC and the intervention, based on specific aspects such as the effectiveness of the collaborative approach in improving communication among healthcare teams and the value of the structured learning sessions and action periods in fostering professional development and knowledge sharing. Participants expressed particular appreciation for how the mQIC facilitated better interdisciplinary collaboration and a more patient-centered approach in acute stroke treatment.

As we will expand upon below, in the domain of Inner Settings (D3), the most frequently cited facilitators were Networks and Communications (n=51, D3.2) and Culture (n=36, D3.3). Concerning Networks and Communications, the participants reported effective dissemination of essential information regarding the various activities within the mQIC. Additionally, the interdisciplinary nature of the teams was deemed a critical success factor by the interviewees. As for the Culture aspect, the respondents highlighted the mQIC's role in fostering a culture conducive to embracing change at their respective sites, as well as the significance of maintaining an adaptive organizational culture for the successful implementation of the mQIC.

Within the Process domain (D5), the most commonly reported facilitator was the engagement of key stakeholders (n=37, D5.2.5). Besides emphasizing the value of involving stakeholders typically associated with such collaboratives, interviewees underscored the mQIC's ability to successfully engage underrepresented stakeholders, including emergency staff. This inclusive engagement was considered a vital contributor to the mQIC's success. In the context of Outer Setting Characteristics (D2), respondents predominantly identified Peer Pressure (n=26, D2.3) as a facilitative factor, noting that it fostered a positive competitive atmosphere within the mQIC.

In the domain of Innovation Characteristics (D1), Design Quality & Packaging (n=26, D1.7) emerged as the most frequently cited facilitator. Specifically, respondents praised the mQIC's adaptability in response to the constraints imposed by the COVID-19 pandemic on face-to-face interactions, and its successful transition to accommodate virtual activities. Among the Individual Characteristics (D4), respondents emphasized the Individual Stage of Change (n=9, D4.3) as a key domain. Interviewees noted the mQIC's effectiveness in enhancing various skills, including knowledge acquisition, team cohesion, collaboration, interprofessional communication, and negotiation, ultimately leading to improved patient outcomes.

On the other hand, most high frequency barriers were concentrated in the inner settings and process domains. The top of the list shows three inner settings domain constructs: resource availability, relative priority, and networks and communications. The two main resources needed by the participants were time and funding. In addition, the mQIC took place during the global COVID-19 pandemic, which led to an increase in many side-tracking responsibilities for many participants. The most frequently coded construct was Available Resources (n=19), followed by Relative Priority (n=17) references, respectively. Networks & Communications comes next with 9 references and followed by Key Stakeholders (Staff) (n=6) and Culture (n=4). Finally, Design Quality & Packaging, Reflecting & Evaluating, Complexity, Relative Advantage, Leadership Engagement and Executing come each with 3 or less references.

Figure 2 shows barriers frequencies compared to facilitators frequencies for the same constructs. In the following, the key findings are presented by domain.

3.1. (D1) Innovation Characteristics

Three significant innovation characteristics constructs were identified as facilitators. It was essential for the participants to recognize the strength of the evidence considering it as a key motivation to participate in the mQIC. This resulted in comprehending the relatively high degree of advantage of the project, which in turn led to assigning a high level of priority (inner settings domain) to the related tasks, even amidst the pressing obligations arising from the global COVID-19 pandemic. The interviewees acknowledged the design quality and packaging as another facilitative factor, particularly its adaptability in accordance with COVID-19 regulations.

3.1.1. (D1.2) Evidence Strength & Quality

The evidence presented at the Learning Sessions revealed barriers and facilitators to implementing best practices. Despite the mQIC designers' aim to present the quality and strength of the evidence, emergency medicines in one location, were not that convinced in the evidence. interviewee003 mentioned that “even though the emergency physicians are not part of the process, or there is a very small part of the process because they activate the stroke protocol and then they basically step back. I think we're still influenced by their attitudes towards tPA. And not all of them buy in to the fact that tPA is helpful, and, some of them feel it's harmful and so that may influence some of the activations”.

On the other hand, many other interviewees showed their appreciation of including the presentation of the evidence as well as the way it was presented as part of the initiative. Three participants felt their sites were aware of the evidence, but ACTEAST helped review it and improve understanding of the rationale for the team's work and the priority of re-evaluating the processes. Interviewee001 said “it's always good to review and kind of put it into context. I would say that probably, for the nurses or admin people on the team, it might have been newer information for them too, and it could help them to understand the rationale for what we were doing”. Interviewee006 mentioned that “So I think understanding the evidence and understanding the improvement’s potential for the patients made a difference. And again, really, I think it made the biggest impact for the members of our group, who are the ED group to get on board with a really rapid response in getting the specialties involved, getting radiology involved, getting everyone involved earlier”. Presenting the evidence showed the urgent nature of stroke cases and resulted in moving from a "haphazard" protocol to a "true protocol", according to interviewee009. For interviewee012, presenting the evidence improved their knowledge in the stroke treatment.

The understanding of the evidence has changed for five interviewees, as some of the information was presented in a way that was easy to directly relate to improved patient outcomes. Interviewee007 said "Putting the human behind it instead of just the numbers did give it a different lens". Interviewee002 said “those presentations in particular really expanded my understanding of the evidence around imaging and its impact in decision making”. The evidence understanding has fluctuated for interviewee010 who said “it was quite amazing to hear how different interpretation of the evidence is from a neurology perspective versus emergency medicine perspective”.

The impact of evidence strength and quality primarily influenced the implementation of the mQIC rather than direct stroke care. Skepticism among emergency medicine practitioners regarding tPA efficacy emerged as a significant barrier, affecting the activation of stroke protocols and overall buy-in for the mQIC. Conversely, positive reception and improved understanding of the evidence among other healthcare professionals acted as a facilitator, leading to enhanced engagement and adherence to structured response protocols. Additionally, the diversity in evidence interpretation between neurology and emergency medicine highlighted the challenge of aligning different medical specialties, impacting the cohesive implementation of the mQIC.

3.1.2. (D1.3) Relative Advantage

Because of the chaotic nature of emergency environments, staff understanding the direct advantages of changes is required to be compelled to implement them. Interviewee012 says “once you explain it to them, they usually get it, but it's just that change piece, that change management piece takes a little bit of time”.

One advantage of ACTEAST mentioned by an interviewee was that it had started many conversations. Interviewee010 said “I think this initiative provided us with the framework for launching at those initiatives and then opportunities of learning more from this research”. For three interviewees, the improvement team and the principal investigator discussed specific improvements that made the process more efficient and improved the DNT and stroke care. For example, interviewee012 said “it kind of brought it to the forefront. So it's not just, it's another stroke, it's OK, let's see what we can do. Let's see what we can save. You know how much you know about disease we can [improve processes to avoid] long lasting disability”.

For two interviewees, ACTEAST provided a framework for launching initiatives planned before the project started. For example, interviewee010 said “I think this initiative provided us with the framework for launching at those initiatives”.

Interviewee010 recognized how ACTEAST enabled more communication between sites and fostered broader discussions around the benefits and risks of lytics versus EVT. They said “[ACTEAST] fostered broader discussions around the benefits and risks of lytics versus EVT and imaging”.

Interviewee013 described the advantage of monitoring and analyzing data to determine where improvements must occur "then to start to really begin to critically appraise the work that we're doing and figure out where we are not achieving our goals".

Our analysis of the ACTEAST initiative shows it mainly impacted the implementation process, not directly improving stroke care. It emphasized the need for effective change management and facilitated important discussions, aiding in the adoption of better practices in emergency settings. Key impacts included improved inter-site communication, deeper treatment discussions, and strategic data use for ongoing improvement.

3.1.3. (D1.7) Design Quality & Packaging

Two interviewees preferred in-person activities. For example, interviewee003 expressed that the virtual format of many ACTEAST activities negatively influenced the project as it limited networking opportunities, and virtual activities are not healthy as they involve a lot of sitting and screen time. Interviewee003 said “and it's not always the formal part of the day, but it's the informal side conversations. It's the who you sit with at lunch and who you strike up a conversation with you. You don't get that when you're meeting online”. Nevertheless, the virtual format was the only possible option for meeting under the COVID-19 pandemic restrictions, and it was even considered a positive outcome of the pandemic, allowing gathering many stakeholders efficiently while saving expenses according to four interviewees. Interviewee001 said “I know at first whenever the decision was we're going virtual. I kind of thought I don't know how that's going to work, but really, I think it worked pretty good”. Four interviewees appreciated the design quality of the project, as all the necessary information was provided with check-ins from the Principal Investigator. For example, interviewee007 said “all the information was provided. Things were set up for us. [Principle Investigator] checked in on things”.

The design and packaging of ACTEAST activities mainly influenced its implementation, with the shift to virtual format due to COVID-19 eliciting mixed responses. Key aspects like comprehensive information provision and regular check-ins by the Principal Investigator were vital for engagement and smooth execution of the mQIC during the pandemic, despite not directly impacting stroke care.

3.2. (D2) Outer Setting

Outer settings are generally regarded as facilitators, both in terms of the project's cosmopolitanism across the entire province of Nova Scotia and the constructive competitive atmosphere among the various locations created by this provincial level collaboration.

3.2.1. (D2.1) Needs & Resources of Those Served by the Organization

Most of the references for this construct were related to improving the stroke process, specifically obtaining patient and/or family consent before starting treatment. For nine interviewees, they felt it was essential to get the patient's or family's consent to the stroke treatment. Interviewee002 pointed to how ACTEAST brought the question of consent to the forefront of discussion “And this was another not an issue at our site, but kind of something that our physicians had some questions about”.

Two interviewees stated that calling 911 or presenting to a hospital is an indirect form of consent. Interviewee010 says “From a paramedic perspective, we assume that they're consenting their care by calling 911”.

Five interviewees pointed to the emergency time-sensitive nature of a stroke case and that consent to stroke treatment should be handled the same way as a trauma case or a heart attack. Interviewee003 thought that it was unfair to ask the patient or their families to make a decision “I think it's more of a process of informing the families or the patient that this is what we would recommend. And unless you object to that, this is what we're going to do, but I don't think it's fair to ask them who are in an absolute state of crisis that you know for their opinion really”.

Interviewee004 was more concerned about managing expectations “You know there's a lot of them have seen the TV shows, even the commercials in Canadian about stroke, you know? good thing you called us early. We've cured you well, that's not reality and so managing those expectations happens through consent”. Interviewee013 said “We don't get consent to treat people who have been in a trauma. We don't get consent to treat people if they've had a heart attack”.

Interivewee005 talked about a patient who was "very upset that someone would take the time to stop and ask him if and give him their information to see if he wanted it. He said, why wouldn't I? Why would you stop and ask somebody that, when my mind wasn't processing properly?". The stroke coordinator had to explain that the treatment comes with risks and the patient had to be informed.

This aspect significantly influences the direct care of stroke patients. The assertion that consent profoundly impacts direct care of stroke patients is substantiated by the qualitative analysis of interviews, such as the insight from Interviewee003 who states “I don't think informed consent in the traditional sense is practical in that situation, because it is very much an emergency situation. And the longer you delay it, the worse they're going to do”.

The predominant focus among interviewees on the issue of obtaining patient or family consent before starting stroke treatment underlines a critical aspect of patient care. The perspectives vary, with some likening the emergency nature of stroke treatment to trauma or heart attack cases, where implicit consent is assumed. This approach is contrasted by the concerns raised about managing patient expectations and the ethical complexities of informed consent in crisis situations. These insights underscore the delicate balance in stroke care between the urgency of treatment and respecting patient autonomy.

3.2.2. (D2.2) Cosmopolitanism

Being a provincial project gave ACTEAST a level of importance in Nova Scotia, according to seven interviewees. For example, Interviewee001 said “I think because it was provincial project, it kind of gave some added value to it and gave it a level of importance”. Even though, as per interviewee003, at the province level, there was always a stroke network among the coordinators, ACTEAST was an opportunity for older participants to get to meet and know newly joined ones. Interviewee003 says “there are a lot of players that have changed in that time and I may know the stroke coordinator in an area, but they don't necessarily know the physicians, and especially the emergency physicians. So, it was really good to see all that engagement around the province. I think that was probably a big benefit from [ACTEAST]”.

Three interviewees highlighted the "invaluable" ACTEAST networking opportunities. Interviewee004 said “Those networking opportunities are invaluable”. According to interviewee002, “[ACTEAST] connected local players with each other and then connected those same players with other players across the province”. This includes local specialists that would be collaborators on some future cases. Interviewee013 mentioned that “The idea that we're all in this together and that we need to work collaboratively”.

The ACTEAST initiative, with its provincial reach, significantly enhanced the mQIC implementation in Nova Scotia. Its cosmopolitan aspect boosted the project's value and regional engagement. The initiative also established a key networking platform, promoting collaboration and knowledge exchange among healthcare professionals. This network facilitated the integration of new participants into the stroke care network, reinforcing a collaborative, province-wide approach to stroke treatment in Nova Scotia.

3.2.3. (D2.3) Peer Pressure

Four interviewees stated that seeing changes in other sites created positive competition. This allowed sites to learn from the experiences of other sites, both positive and negative. Interviewee001 says “it always, takes the question, how come they can do it and we can't? so it drives people a little bit”. Interviewee004 also said “I'm always a friend of competition”. Interviewee008 said “hearing how one of the sites in our province had their door to tPA time down to 10 minutes with just incredible because we were very impressed with that and we're doing what we could to try and improve our time to get closer to theirs”.

Seeing other sites' performance data and changes was positive for nine interviewees. For example, Interviewee005 said “I found it really gave our site new ideas to try to improve times at our own site”.

According to interviewee004, knowing what is going on at the different sites is essential for the tertiary site in terms of realizing that the referring sites are doing what is required to prepare patients before being transferred. They mentioned that “especially when we're referring to Halifax as our tertiary care site, you can see what they're doing and what we can do to get things ready for patients going there”.

Other interviewees did not feel that peer pressure played a role in implementing improvement. An interviewee pointed out that peer pressure did not have an impact because the site was already highly motivated. Interviewee006 highlighted that the overload resulting from the COVID-19 pandemic has diminished the positive effects of peer pressure by saying “just because of time and you know people not being able to actually enact anymore change because they had no time to do it because they were in this COVID meeting or in that COVID meeting”.

Interviewee002 pointed out that sites in their particular region do not like to be compared to other places, and it was tricky to consider peer pressure as positive motivation. However, the sites that had a peer pressure impact were in the same geographical zone with similar resources and sizes. Interviewee002 said “I think in [our province] we're a little bit unique, whereas when we see those numbers we kind of get our defenses up and we think we don't love to be compared to other places”. They continue to say that a certain site “is in our zone and resource wise they are relatively similar to us, so I think it's easier for folks to make the relationship between numbers there and numbers here”.

The concept of 'Peer Pressure' in the ACTEAST project played a notable role in the implementation of the mQIC, as indicated by participant feedback. Positive competition, as observed by four interviewees, encouraged sites to adopt successful practices from others, enhancing motivation and fostering a culture of continuous improvement. However, not all viewed peer pressure positively; concerns ranged from pandemic-related overload to regional differences in receptiveness to comparative performance.

3.3. (D3) Inner Setting

The inner settings domain encompassed both the most frequent facilitators and barriers. The availability of resources, including time and funds, was identified as the highest frequency barrier. The difficulty of assigning high priority to mQIC activities was another barrier, but this same construct was also seen as a frequent facilitator, indicating that sites were able to prioritize the project.

3.3.1. (D3.2) Networks & Communications

Networks and Communications is the highest mentioned ACTEAST facilitator and one of the highest mentioned barriers. Sources of information, according to all interviewees, about stroke evidence and the project included: webinars, and emails among the team members and from the site leadership, the emergency department, the stroke coordinators, and the principal investigator. Just as one example, Interviewee002 said “[Principle Investigator] was good to communicate. Our teams were fairly good to communicate as well. So we would have regular meetings with minutes and follow up action items”.

Networks and communication challenges were mentioned by three interviewees. Interviewee001 mentioned at the beginning of the project “identifying the team was challenging”. Another challenge was the disjointed teamwork at times according to Interviewee003 who said “COVID really interfered with the ability to meet and I think, had we been able to meet, maybe every two weeks in person as a group, it could have gone a lot smoother”. Interviewee005 explained how COVID-19 restrictions, and significant team change within the first couple of months negatively affected the participation in the mQIC “they were over committed, and so there was a change because some people backed out”.

According to interviewee013, the action distribution over different departments and specialties resulted in slow progress since the relationship with some departments was challenging. On the other hand, a principal part of ACTEAST was the development of multidisciplinary improvement teams and the facilitation of collaboration within the team. These were well appreciated by four interviewees. Interviewee001 said “I feel like the most beneficial part [of ACTEAT] was the fact that we had to develop the team”.

Teams worked together well, according to eleven interviewees. For example, Interviewee003 says “I would dream about them forever. They were gold”. Two interviewees attributed the excellent teamwork to the stroke coordinators and the long collaboration history before ACTEAST, as mentioned by Interviewee008 who said “I’m fortune enough that I've been around long enough to know the majority of the stakeholders in emergency department”.

The 'Networks & Communications' element was pivotal in the implementation of the mQIC within the ACTEAST project. Effective communication channels, such as webinars and emails, facilitated information dissemination, as noted by all interviewees. However, challenges like team formation, disjointed teamwork during COVID-19, and turnover posed significant barriers. Despite these, the development of multidisciplinary teams and collaboration was highly valued, contributing to the project's success.

3.3.2. (D3.3) Culture

The relationship between the sites’ cultures and ACTEAST was bidirectional. On the one hand, open culture at some sites helped accept the changes introduced by ACTEAST. On the other hand, ACTEAST helped at some sites in making the culture more open to changes. The 'Culture' of healthcare sites significantly influenced the implementation of the mQIC in the ACTEAST project. The interviewees spoke about a culture that resisted change. Three interviewees expressed the difficulty of making changes and resistance to change. Interviewee002 said: "I think any suggestion or changes meshed initially with we can't do that and then so it takes a while to breakdown that barrier, [which] is a characteristic of our culture here". A concrete example of this kind of difficulty was given by Interviewee012 who said “in meetings with our imaging department, things like trying to convince the radiologists to call the ED doc right after the image is done. Something as simple as that. Yes, we can't do that”. Interviewee013 described the culture at their site to be “the culture of a busy, highly stressed emergency department has challenged the ACTEAST process to become more efficient”.

ACTEAST helped culture to change over time at one site and became very open. Interviewee001 said that the culture “has probably changed a little bit over time [to become] open and willing to try new things”. Intervewee009 explains how most of the younger and nursing staff were open to change while doctors were not by saying “So I think that the nursing staff on the most part and the extra staff were open to a little bit of change. Doctors not so much. And then the also, the younger people younger staff were open to changes, [so] culture is better”.

Adopting changes was welcomed by the teams and leadership at five sites. For example, Interviewee007 pointed to how the change of the leadership led to a more open culture “We had a bit of a change of leadership in the middle, so nearer to the end, everyone was very welcoming”. However, even with everybody onboard, changes still needed a lot of collaboration within sites and accordingly dealing with each sites' own cultures, according to Interviewee010 who said “a lot of collaboration was needed with sites and working with other kind of settings and their cultures and how care is provided”. Moreover, Interviewee007 said “if a process change impacts a lot of departments, there can be a lot of risk in that, and so people are adverse to just jumping into something that does have more global impact. So we do have processes clearly set up to implement change appropriately”.

However, to EHS, despite some challenges, change is welcome. Interviewee007 stated, "prehospital care is an ever-changing environment, so we are always willing to change, but don't love change". In addition, Interviewee010 says “within Paramedicine in Nova Scotia we have a focus on evidence based medicine and we have a history of collaborations with emergency medicine”.

3.3.3. (D3.4) Implementation Climate

The 'Implementation Climate' within different sites played a crucial role in the implementation of the mQIC as part of the ACTEAST project. Eight sites did not prioritize stroke management, often due to their site’s culture and due to COVID-19. However, three sites maintained stroke as the top priority, employing strategies like dedicated staff and leadership collaboration. On the other hand, feedback was provided through virtual site visits which were generally positive, as they allowed discussion of site-specific issues and boosted team morale, though some participants struggled to engage or did not find them impactful.

3.3.3.1. (D3.4.3) Relative Priority

At eight sites, stroke was not a priority. For example, Interviewee003 says “it's still not seen as important as acute MI or trauma”. Additionally, according to Interviewee013, leadership welcomed changes if they did not disturb other processes or require funding. Interviewee013 says “if our process is going to cause delays in another part of the system, they want no part of it. If it's going to cause an excessive expenditure of money, they don't want any part of it”.

At other sites, individual role tasks of some participants were prioritized over some ACTEAST activities. Interviewee003 pointed that “part of the issue is that the people who are on these teams are typically the people who are on lots of teams […] so they have lots of things on their table”.

COVID-19 and the different pandemic waves were getting the highest priority at five sites. Interviewee002 said “engagement was a little bit tough in part because people had their priorities [during the pandemic lockdown]”. One interviewee thought that the pandemic priorities were even used as an excuse for not achieving improvement in reducing DNT. The extra load resulting from COVID-19 led interviewee006 to a feeling of failure in dealing with competing priorities as they say “Towards the end it was a major issue and I feel like I was drowning”.

According to four interviewees, dedicating staff to managing the ACTEAST activities was the way to keep it prioritized. For example, Interviewee012 says “having [someone] dedicated to it […] was amazing”.

At three sites, stroke always had the highest priority. For example, Interviewee004 says “I didn't really find any competing priorities”. Ways mentioned by interviewees to address competing priorities included face-to-face conversations and following up, dedicated staff, regular meetings, updating senior leadership, collaborating with other sites on the leadership level, and negotiation. For one interviewee, dealing with competing priorities needs openness about the pressures and the barriers and trying the best to work around them.

The 'Relative Priority' of stroke management across various sites notably affected the implementation of the mQIC in the ACTEAST project. While some sites de-emphasized stroke care due to competing healthcare needs or resource constraints, others, particularly during COVID-19, faced challenges in maintaining focus on stroke initiatives. In contrast, dedicated staffing and consistent prioritization helped keep stroke care as a primary focus, demonstrating varied approaches to managing competing priorities in healthcare settings.

3.3.3.2. (D3.4.5) Goals and Feedback

Feedback was provided to the mQIC participating sites via a virtual site visit. One interviewee explained how the virtual visit allowed for discussing project-related topics with a site outsider. Interviewee004 said “maybe get some critique from somebody from the outside [principal investigator]”. Interviewee006 explained how it boosted the team's morale, generated ideas, and engaged new participants and noticed that specific site struggles and solutions were discussed during the visit by saying “it kind of had a boost on the morale of the team and I think it gave them some ideas of things because it's one thing in a large group session when people are talking about generic ideas that can be done, but it is helpful when somebody [principal investigator] either face to face or virtually is visiting directly with you learning about the struggles you're having, the problems you're having and coming up with specific solutions for those”. However, for interviewee001, the virtual visit was the most challenging part of the project to engage people with as it was hard to understand its benefit. Interviewee001 said “This was probably the piece of the project that I struggled to get the most people engaged with […], maybe it was harder for us all to understand the benefit of this piece”. Accordingly, interviewee001 reported that the virtual visits were not impactful.

The provision of feedback via virtual site visits played a crucial role in the implementation of the mQIC within the ACTEAST project. These visits facilitated valuable external critique and insights and were instrumental in boosting team morale and generating tailored solutions to site-specific challenges.

3.3.4. (D3.5) Readiness for Implementation

Leadership engagement was critical for implementation, with some interviewees highlighting the importance of support from higher positions such as Interviewee001 who said “I mean obviously if they [the managers] didn't support it would have been hard to move ahead with it”. Other interviewees emphasized a collective leadership approach as was the case with Interviewee004 who said “I mean, they just want us to do what you need to do. Let us know if you need some help so there's no issues anywhere along the way”.

Time was a scarce resource, often due to competing commitments like COVID-19. Interviewee002 said “there were times when I felt like I was asking a lot of other people, so I would just do it myself and then it was a lot for myself”, and Interviewee005 said, “I think people are busy and changes to the system take time. You need time to educate and then you need to evaluate the things and then change again if needed”. Solutions included task prioritization and efficient planning.

3.3.4.1. (D3.5.1) Leadership Engagement

The interviewees felt that leadership engagement had a significant impact on their results. For interviewee013, the mQIC did not result in a significant impact because the team could not engage people in higher positions with authority to implement the planned changes. Interviewee003 said “one of the other reasons it didn't have a big impact is that we were not able to engage other people and mostly people in higher positions who have the authority to implement the changes that we want to change”. Conversely, one interviewee mentioned that prior roles and good relationships with their leadership resulted in getting the buy-in from leadership and everyone down as Interviewee006 says “because of some prior roles that I've had, I have a good relationship with the leadership at the hospital anyway, so we had buy-in from the site lead at the hospital and really from everyone on down”. On the other hand, Interviewee013 felt that leadership is provided by all employees, "We are the leadership. I must say we don't spend a lot of time talking to people who work at levels above us just because they don't have the power to make to effect change". In addition, Interviewee014 explained that there is no need for processes that go through several levels of authority in a small hospital by saying “We don't need to multi-level processes, we decide what we're going to do between us and the emergency department and the internists and we are able to implement those without bureaucracy”.

Leadership engagement emerged as a pivotal element in the implementation of the mQIC in the ACTEAST project. The ability to engage higher-level authorities significantly impacted the implementation outcomes. Furthermore, a few interviewees highlighted a more grassroots approach to leadership, with decisions made locally and swiftly, especially in smaller hospital settings.

3.3.4.2. (D3.5.2) Available Resources

Time was the most limited resource for six interviewees. Accordingly, Interviewee002 mentioned that actions had been carried out by a small group of participants “you get folks volunteering for teams and then they can't really dedicate as much time as it required so couple people end up doing more than others, that becomes taxing”. In addition, participants backed out as per Interviewee005’s citation mentioned above. One interviewee expressed that some participants, physicians in particular, already had busy schedules as mentioned by Interviewee003 “So [the mQIC] was difficult to fit into an already very busy schedule”. Time was limited because some participants volunteered for many projects or the COVID-19 extra meetings.

To work around the busy schedule, prioritizing tasks and a task-oriented operation with specified deadlines were adopted as per Interviewee004. The same interviewee recognized the excellent planning and organization of the mQIC allowed for a smoother time commitment. Other mentions of limited resources by three interviewees included limitations of financial resources, particularly for a stroke coordinator position and other required material. For example, Interviewee003 said “it was a lot of things that we need significant financial or other resources to implement”. Time constraints significantly impacted the implementation of the mQIC. Limited time availability, exacerbated by the COVID-19 pandemic and other commitments, often resulted in a few participants handling the majority of the workload. Effective strategies, such as prioritizing tasks and setting clear deadlines, were essential for managing these time challenges. Financial limitations for critical roles and resources also posed challenges.

3.3.4.3. (D3.5.3) Access to Knowledge and Information

The information and access to knowledge provided by the mQIC was found to be both beneficial and challenging. For Interviewee012, education of the operational team is a challenge in implementing changes as they need to understand the rationale. Interviewee012 said “the biggest hurdle is getting everybody educated, not that they're not on board or not that they don't understand because we usually do a pretty good job of front ending that information, so it's getting them to change, actually, physically change their practice”.

According to Interviewee009, the information and knowledge acquired through the project resulted in tuning protocols to the sites' particular needs. The interviewee says “fine tuning a protocol to your site specifically that was set for me”.

The webinars conducted during the mQIC were a source of knowledge and information. According to six interviewees, the topics covered in the webinars were excellent, even with varied attendance because experts were available in webinars for comments and questions, even when they were not presenting. For example, interviewee001 said “I thought the topics that were covering were important. We didn't always have great attendance that are from our sites. It kind of varied, but what was good about them was that though, it's like learning what's happening to other sites, but also having the experts available for comments and questions. So even if the you know experts weren't presenting, you had neurology or interventional neuroradiology on the call, making comments and answering questions”.

According to Interviewee011, webinars helped realize the positive effect of speeding up the processes. An interviewee from a presenting site expressed that even when the webinars were not locally beneficial as a learning opportunity for the site, they still increased the overall process efficiency. Interviewee006 explained how webinars that presented successful outcomes for patients transferred for EVT had rejuvenated physicians to take the transfer decision.

Two interviewees explained that the topics and conflicting meetings presented challenges to attending the webinars. For example, Interviewee006 said “I missed a number of these [webinars] because of having to be at conflicting meetings”. Interviewee002 suggested having external experts presenting, as opposed to local, as local initiatives can sometimes be limited in their progress. The interviewee said “sometimes local initiatives can't be progressed further. Unless you've got expert coming in saying this is where we need to go”.

Effective knowledge dissemination was key for implementation. Challenges included educating teams about practice change and issues like inconsistent attendance at beneficial webinars, which faced scheduling conflicts. However, the value of tailoring protocols to specific site needs was highlighted.

3.4. (D4) Individual Characteristics

Most of the individual characteristic references were facilitators and related to the stage of change of the participants. These references mainly pertained to the new knowledge or skills acquired through the mQIC.

3.4.1. (D4.3) Individual Stage of Change

The interviews revealed that participants of the mQIC were at different stages of implementing improvements. According to six interviewees, ACTEAST helped build up and improve skills in terms of “knowledge base and understanding what's actually happening” (Interviewee001), “bring teams together” (Interviewee002 and Interviewee004), “collaboration” (Interviewee006), “interprofessional communication” (Interviewee008) and “advocate for the patients” (Interviewee009). For five interviewees, no skills related to acute stroke treatment were built or improved. Interviewee014 attributed this to the excellent stroke training as a radiologist at one of the participating hospitals.

In the mQIC, participant progress varied across different stages, affecting the overall project implementation. While some interviewees credited ACTEAST with skill enhancement vital for stroke treatment improvements, others perceived no new skill development.

3.5. (D5) Process

Engaging key stakeholders was a frequently identified facilitator. In general, stakeholders or champions recognized the benefits and importance of the mQIC and actively participated or identified other stakeholders to involve.

3.5.1. (D5.1) Planning

The interviews revealed that the action planning provided during the Learning Sessions of the mQIC was integral to planning improvements. Interviewee001 said “I really liked having that time. As opposed to, you know, here's your learning session and you know, maybe you guys can get together at some point later on. I think this way we were kind of not forced into doing it, but it's built into your meeting”. interviewees thought the action planning was impactful even though not perfect because of COVID-19, according to interviewee005 who said “not that it was perfect either because again, same caveats as previously with COVID really throwing a wrench in some things”. For Interviewee009, it helped focus efforts and provided a framework and a list of actions. The interviewee said “It did help focus our efforts and provide us with that framework for improving our care over that six month period. Gave us a list of things we wanted to work on”. Interviewee007 explained how having several departments at the table with the right stakeholders involved allowed for better process streamlining. The interviewee said “different departments at the table who were all invested in this, it let us develop some processes a little more streamlined and with the right people involved and the right stakeholders. And because of that we were able to move some changes along faster than we would have if we didn't have the collaborative”. At Interviewee013’s site, different communication and coordination issues resulted in inefficient action plan, as the interviewee explained “They came up with things that needed to be fixed. Then for some things, they determined actions that should be taken. Didn't really assign them to people and they didn't really set a date when they should be done”.

Interviews revealed that structured planning during the mQIC's Learning Sessions was key to its implementation, especially amidst COVID-19 challenges. Participants appreciated the clear framework and goal-setting, along with the advantages of involving multiple departments in process streamlining. However, some coordination issues impacting planning efficiency were also identified.

3.5.2. (D5.2) Engaging

Five interviewees found engaging certain departments challenging, while having influential participants and involving emergency staff and EHS physicians were seen as key to success.

3.5.2.1. (D5.2.5) Key Stakeholders (Staff)

For five interviewees, engaging particular departments was challenging because of attitudes or competing priorities. For example, Interviewee002 said “getting DI engaged was tough. We ended up getting a CT tech but we couldn't get a radiologist involved”. Interviewee003 said “the nurses in the emergency department are not engaged, and I'm not sure if that's related to the physician's attitude or they're just overworked!” and Interivewee012 said “physician engagement is tough here, and it's not that they don't agree. It's not that they don't understand the data, obviously they do […], [in a small hospital], physicians time is very precious and it's difficult to get somebody committed to an improvement process like this”.

According to four interviewees, appropriate participants were able to influence their departments. For example, Interviewee001 said “we had appropriate people that are sitting at […] our tables and so if you got the buy in from everyone at the table, really they went back to their own department or specific team in the hospital”. Interviewee001 mentioned that the mQIC had created an environment where everyone felt efficient. The interviewee said “I feel like everyone that was involved was influential on their own right because they really pushed things in their own departments”. For two interviewees, engaging emergency staff and EHS physicians was a key to success. For example, Interviewee012 said “the biggest thing is the engagement from who needs to be engaged from EHS to DI to the physicians to the staff, you know, so it's just reaching out and you know making sure everybody has what they need and has the information they need to get them there”.

Stakeholder engagement, particularly among staff from various departments, was essential for the mQIC's implementation. Challenges in engaging certain departments due to competing priorities or attitudes were noted. However, having influential staff who could effectively communicate within their departments significantly aided the initiative’s success.

3.5.3. (D5.4) Reflecting & Evaluating

Reflection and evaluation of the mQIC showed mixed feelings about the mQIC. For Interviewee005, everything related to the ACTEAST mQIC was stressful due to added daily work. The interviewee said about the mQIC “It was almost like adding another, you know 25% onto an already 100% job that's you know. So there were times that it left me stressed”.

Eight interviewees expressed that all or most parts of the mQIC and the resulting changes will stay after the end of the mQIC because of its positive outcomes. For example, Interviewee013 said "Programs of research like ACTEAST are vital to make sure that a systems change can actually take place". For Interviewee013, the mQIC is an ongoing process, as there are always things to fix and improve. The interviewee says “I'm not sure that the collaboration is ended. It's an ongoing process, right? Because there are always things to fix and to improve upon”. Interviewee013 was a stroke neurologist and all the ACTEAST mQIC activities and tasks were part of their daily job. Still, for that same interviewee, sustaining the changes and operationalizing the work was challenging. Interviewee013 reported that further follow-up after the mQIC ended and continuous data feedback would be excellent by saying “be nice to follow up with the [Principle Investigator] and kind of hear, next steps”.

4. Discussion

Through this study, we identified various facilitators and barriers for improving the utilization and efficiency of AIS treatment in Nova Scotia through an mQIC. Ultimately, the goal of identifying the barriers and facilitators is to investigate the perceived impact and future implementability of the mQIC in different sites and/or settings. To answer these research questions, semi-structured interviews, containing qualitative questions were conducted with fourteen mQIC participants and analyzed with CFIR.

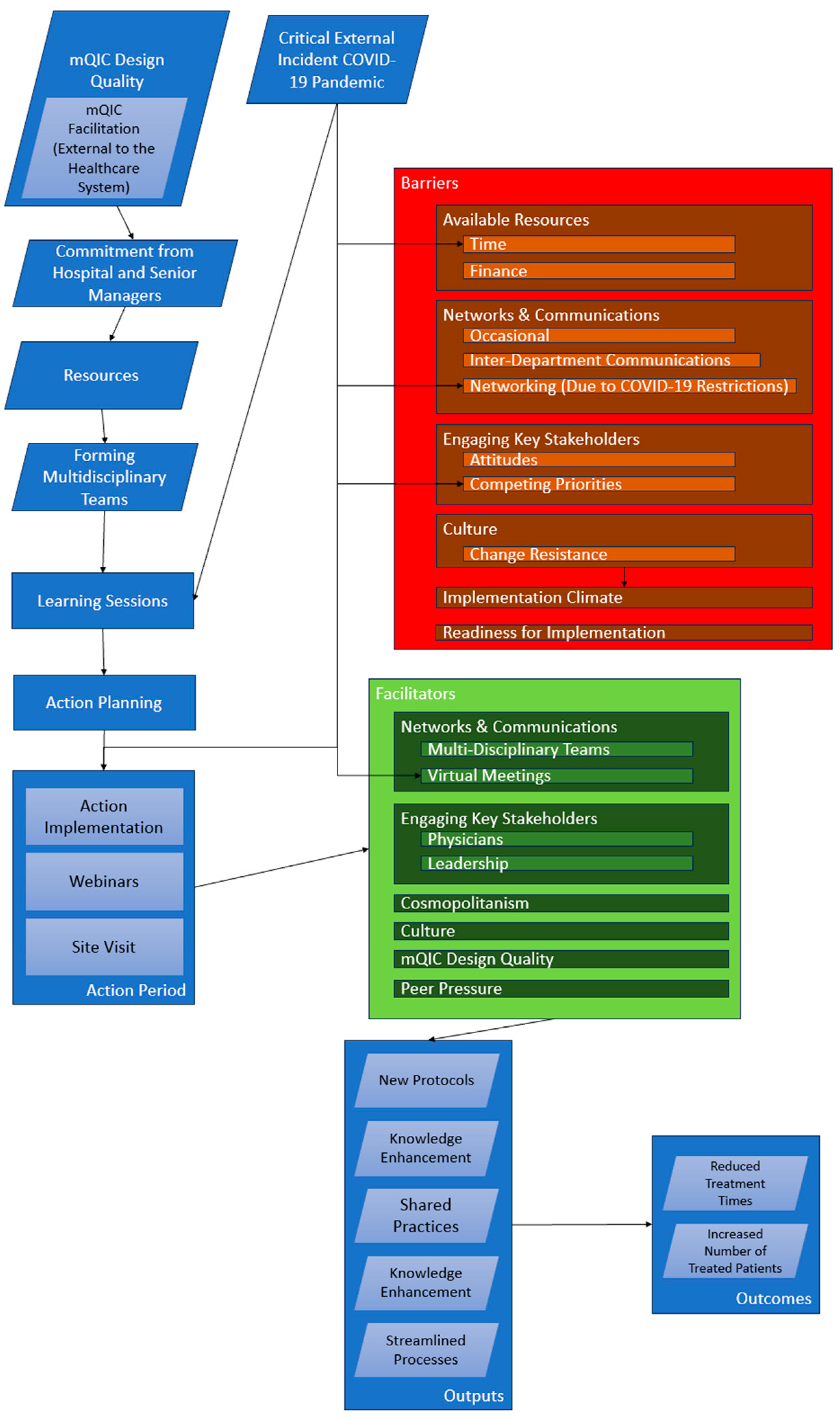

Figure 3 depicts a post-study logic model of the mQIC, integrating key findings from the initiative's evaluation. Inputs included healthcare professionals' expertise and resources for conducting virtual learning sessions, crucial during the COVID-19 pandemic. Activities such as learning sessions, action planning, and webinars aimed to improve stroke treatment protocols. Outputs reflected enhanced knowledge and shared practices among participants. Outcomes targeted improved treatment processes and reduced treatment times. The model incorporates external influences like the pandemic, which necessitated virtual engagement and influenced the effectiveness of activities. Facilitators highlighted in the model include effective communication and stakeholder engagement, while barriers involve time and funding constraints. This post-study logic model thus succinctly encapsulates the interplay between the initiative's elements, facilitators, and barriers, providing a clear framework for understanding the mQIC's impact on stroke care improvement.

The barriers most often reported by participants related to available resources, namely the lack of available time and financial resources to undertake implementation. While financial obstacles require more effort and time to overcome, some participants handled time limitations with planning and prioritizing. This provides important insight into future use of an mQIC to improve acute stroke treatment, as providing participating teams with strategies and support for planning and prioritization (i.e. project management) can mitigate time constraints that are ever present in healthcare settings; however, supports from the health system and hospital to protect time while participating in quality improvement initiative should not be overlooked. This is consistent with studies pointing out that extra resources are required to carry out quality improvement [

29,

30,

31] or explicitly point to limited resources as barriers [

15,

32]. Of note was the fact that COVID-19 was not considered a competing priority by interviewees in sites where stroke has already prioritized. However, for those whose roles were not devoted to stroke treatment and management and thus involved in COVID-19 related tasks, implementation reportedly caused a massive workload increase, leading to feelings of failure in managing competing priorities.

Even though barriers related to networks and communications were among the highest barrier frequencies, this construct was also the highest frequently mentioned facilitator. In some sites, this construct was an occasional barrier, for example, during the team creation phase or because of team changes during the mQIC. Teams' multi-disciplinarity [

32] was considered by many interviewees a facilitator. Still, some signaled the difficulty of communication among different departments. While team formation and dynamics were at times complex, a finding also raised in previous work [

15,

30], the collaboration within the multidisciplinary teams was much appreciated by our study participants. This shows the importance of creating an interdisciplinary team involving individuals from all areas involved in care during the first hours of the stroke (paramedics, emergency department nurse, emergency physician, radiologist, and CT technologist) to guide improvements. This critical first step, while challenging, was critical to implementing best practices in our study. The formation of an interdisciplinary team was identified as a critical pre-determinant to successful implementation [

33]. Having an interdisciplinary team in place is a pre-condition for effective implementation of the mQIC in Nova Scotia. The team's diverse skill set and collaborative approach significantly facilitated the implementation process, setting the stage for the success of the mQIC from the outset.

Engaging key stakeholders has previously been identified as a major barrier [

30]. For ACTEAST, physicians were the most impactful stakeholders to engage; their points of view about the treatment influenced the level of their departments' engagement. Also, leadership engagement has been identified in other work as a facilitator [

29,

32]; this was also a factor appreciated by our study participants during ACTEAST. Communication was not only considered a facilitator on the site level, but the project’s cosmopolitanism was also considered a key facilitator, providing communication and experience sharing among different sites [

15].

Some interviewees identified initial change resistance culture as a barrier. Initial change resistance can be defined as the initial reluctance or opposition that individuals or organizations could exhibit when faced with changes or new initiatives. ACTEAST mQIC was reported to have a positive culture change. The mQIC design quality was appreciated, and the provincial-level collaboration was reported to frequently create a positive, friendly competitive environment. The interviewees reported that the changes implemented during the mQIC will be sustained. Most interviewees expressed their satisfaction with the design quality, including the virtual format of activities, which was the only possible way to meet at the time due to COVID-19 gathering restrictions. Still, a few participants noted the lack of networking opportunities and the unhealthiness of extended screen times. Webinars were felt to be the least beneficial aspects of the mQIC, followed by site visits. In future, the number of webinars can potentially be limited to a few critical topics. Additionally, further consideration should be given to the site visits, as they can be time-consuming for both the mQIC organizers and the sites. If done, the site visits should be organized in a mutually beneficial manner, while allowing the opportunity to connect with each site. Similar thoughts on-site visits during the ACTEAST mQIC were found in other studies; however, they found that having participants play a more active role in the site visit helped enhance their utility [

34].

The mQIC created some peer pressure to improve their acute stroke treatment processes. Most interviewees agreed on the positive impact of peer pressure created by implementation efforts. Only a few sites had reservations. The use of peer pressure in healthcare is not new, and several studies have found it to influence improvements [

35,

36,

37,

38].

The results identified 'Relative Priority' and 'Available Resources' as major challenges, highlighting the need for focused strategies on resource allocation and QIC prioritization within the organization. The cyclical nature of these challenges, where low priority could lead to reduced resources, further lowering priority, is noted. This interplay between prioritization and resource allocation aligns with the findings in [

39] on the importance of systematic resource prioritization.

In addition, other barriers mentioned related to 'Readiness for Implementation' and 'Engaging Key Stakeholders.' It is clear that an organization's readiness for implementation could be directly influenced by the level of engagement from key stakeholders. A lack of stakeholder engagement could signify a lack of organizational readiness and vice versa. This observation aligns with findings from [

40], where organizational readiness is linked to stakeholder engagement.

Similarly, Barriers related to 'Available Resources' and 'Engaging Key Stakeholders' were also prevalent. The availability of resources could be a significant factor in the ability to engage key stakeholders. Insufficient resources may lead to inadequate engagement activities, which in turn could affect the overall success of the mQIC. This aligns with the findings from [

41] that suggest that effective stakeholder engagement relies on clear objectives and the identification of necessary resources.

Other barriers were noted in 'Networks & Communications' and 'Implementation Climate'. Ineffective communication networks within an organization can create an unfavorable implementation climate, as poor connections and information gaps among team members can cause misunderstandings about mQIC objectives, impacting the implementation climate. This is supported by findings in [

42] that link poor communication to decreased performance and productivity, affecting both the work environment and implementation climate. In addition, barriers related to 'Relative Priority' and 'Networks & Communications' were found. The relative priority given to the mQIC within the organization could be influenced by the effectiveness of internal communications. If the mQIC is not effectively communicated as a priority, it may not receive the attention or resources it needs for successful implementation. According to [

43], communication has a major role in employee engagement and morale during change programs, which can affect how initiatives like the ACTAEST mQIC are prioritized.

Also, barriers related to 'Culture' and 'Implementation Climate' were cited by Interviewees 2 and 12. The organizational culture could have a direct impact on the implementation climate. A culture that is resistant to change or innovation may create a climate that is not conducive to implementing new initiatives like the mQIC. In [

44], the organizational culture, especially in terms of flexibility and adaptability, can significantly influence the implementation climate, affecting productivity levels.

Employing the CFIR framework, we coded interview data into constructs, domains, and subdomains, facilitating our coding and synthesis processes. Our thematic synthesis, based on CFIR, highlighted how these constructs influenced broader themes such as organizational dynamics in implementation. This approach provided a detailed view of the various factors affecting the mQIC implementation, encompassing both internal and external influences. The interview questions were framed in a positive manner to explore the perceived impact and effectiveness of the mQIC on acute stroke treatment. Additionally, this study recognizes limitations in recruitment and data saturation. While our approach in these aspects was aligned with our research objectives, it may have influenced the nature and analysis of the responses. Future studies will aim to overcome these limitations.

5. Conclusions

In this study, we described the use of the CFIR to evaluate the implementation of an mQIC aiming to improve ischemic stroke treatment in Nova Scotia, Canada. In our study, interviewees expressed that the mQIC was effective in implementing improvements to acute stroke treatment processes. The virtual format as a facilitator eliminated the need for travel and reduced time commitments, thereby facilitating greater participation. However, the lack of available time was a barrier to prioritizing the work, which can be mitigated by providing strategies to assist teams in prioritization and planning. The study showed the importance of creating an interdisciplinary improvement team, which may be critical when improving acute stroke treatment processes. Additionally, the potential benefits of peer pressure between sites can also be key to acute stroke improvement efforts.

The study also revealed ways that the mQIC could be improved to be even more beneficial. Webinars should only be conducted in areas of keen interest to the participants; quality over quantity should be central when conducting webinars. Additionally, site visits should be planned in a manner that makes the visits more beneficial to the site participants. However, most aspects of the mQIC were found to be beneficial.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org, The interview guide.

Author Contributions

NK conceived of the ACTEAST project, obtained funding for it, managed all the activities related to the mQIC, and provided edits to the manuscript. SA conducted all the interviews, analyzed the data, and wrote the manuscript. KJM conceived the qualitative evaluation, oversaw the qualitative study, and provided edits to the manuscript. Conceptualization, Noreen Kamal; Data curation, Shadi Aljendi; Formal analysis, Shadi Aljendi and Noreen Kamal; Funding acquisition, Noreen Kamal; Investigation, Shadi Aljendi; Methodology, Shadi Aljendi, Kelly Mrklas and Noreen Kamal; Project administration, Noreen Kamal; Resources, Noreen Kamal; Validation, Shadi Aljendi, Kelly Mrklas and Noreen Kamal; Visualization, Shadi Aljendi; Writing – original draft, Shadi Aljendi; Writing – review & editing, Shadi Aljendi, Kelly Mrklas and Noreen Kamal.

Funding

This research was funded by the Canadian Institutes for Health Research (CIHR) Project Grant #PJT -169124.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was approved by the NS Health Research Ethics Board (REB# 1025460).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Tissue Plasminogen Activator for Acute Ischemic Stroke. New England Journal of Medicine 1995, 333, 1581–1588. [CrossRef]

- Goyal, M.; Menon, B.K.; Zwam, W.H. van; Dippel, D.W.J.; Mitchell, P.J.; Demchuk, A.M.; Dávalos, A.; Majoie, C.B.L.M.; Lugt, A. van der; Miquel, M.A. de; et al. Endovascular thrombectomy after large-vessel ischaemic stroke: a meta-analysis of individual patient data from five randomised trials. The Lancet 2016, 387, 1723–1731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emberson, J.; Lees, K.R.; Lyden, P.; Blackwell, L.; Albers, G.; Bluhmki, E.; Brott, T.; Cohen, G.; Davis, S.; Donnan, G.; et al. Effect of treatment delay, age, and stroke severity on the effects of intravenous thrombolysis with alteplase for acute ischaemic stroke: a meta-analysis of individual patient data from randomised trials. The Lancet 2014, 384, 1929–1935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bourcier, R.; Goyal, M.; Liebeskind, D.S.; Muir, K.W.; Desal, H.; Siddiqui, A.H.; Dippel, D.W.J.; Majoie, C.B.; van Zwam, W.H.; Jovin, T.G.; et al. Association of Time From Stroke Onset to Groin Puncture With Quality of Reperfusion After Mechanical Thrombectomy: A Meta-analysis of Individual Patient Data From 7 Randomized Clinical Trials. JAMA Neurology 2019, 76, 405–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamal, N.; Benavente, O.; Boyle, K.; Buck, B.; Butcher, K.; Casaubon, L.K.; Côté, R.; Demchuk, A.M.; Deschaintre, Y.; Dowlatshahi, D.; et al. Good is not Good Enough: The Benchmark Stroke Door-to-Needle Time Should be 30 Minutes. Canadian Journal of Neurological Sciences 2014, 41, 694–696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boulanger, J.; Lindsay, M.; Gubitz, G.; Smith, E.; Stotts, G.; Foley, N.; Bhogal, S.; Boyle, K.; Braun, L.; Goddard, T.; et al. Canadian Stroke Best Practice Recommendations for Acute Stroke Management: Prehospital, Emergency Department, and Acute Inpatient Stroke Care, 6th Edition, Update 2018. International Journal of Stroke 2018, 13, 949–984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamal, N.; Smith, E.E.; Jeerakathil, T.; Hill, M.D. Thrombolysis: Improving door-to-needle times for ischemic stroke treatment – A narrative review. International Journal of Stroke 2018, 13, 268–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kamal, N.; Sheng, S.; Xian, Y.; Matsouaka, R.; Hill, M.D.; Bhatt, D.L.; Saver, J.L.; Reeves, M.J.; Fonarow, G.C.; Schwamm, L.H.; et al. Delays in Door-to-Needle Times and Their Impact on Treatment Time and Outcomes in Get With The Guidelines-Stroke. Stroke 2017, 48, 946–954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gropen, T.I.; Gagliano, P.J.; Blake, C.A.; Sacco, R.L.; Kwiatkowski, T.; Richmond, N.J.; Leifer, D.; Libman, R.; Azhar, S.; Daley, M.B. Quality improvement in acute stroke. Neurology 2006, 67, 88–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwamm, L.H.; Ali, S.F.; Reeves, M.J.; Smith, E.E.; Saver, J.L.; Messe, S.; Bhatt, D.L.; Grau-Sepulveda, M.V.; Peterson, E.D.; Fonarow, G.C. Temporal Trends in Patient Characteristics and Treatment With Intravenous Thrombolysis Among Acute Ischemic Stroke Patients at Get With the Guidelines–Stroke Hospitals. Circulation: Cardiovascular Quality and Outcomes 2013, 6, 543–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katzan, I.L.; Hammer, M.D.; Furlan, A.J.; Hixson, E.D.; Nadzam, D.M. Quality Improvement and Tissue-Type Plasminogen Activator for Acute Ischemic Stroke. Stroke 2003, 34, 799–800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zamboni, K.; Baker, U.; Tyagi, M.; Schellenberg, J.; Hill, Z.; Hanson, C. How and under what circumstances do quality improvement collaboratives lead to better outcomes? A systematic review. Implementation Sci 2020, 15, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Are quality improvement collaboratives effective? A systematic review | BMJ Quality & Safety. Available online: https://qualitysafety.bmj.com/content/27/3/226.abstract (accessed on Jul 4, 2024).

- Anonymous The Breakthrough Series: IHI’s Collaborative Model for Achieving Breakthrough Improvement. Diabetes Spectrum 2004, 17, 97–101. [CrossRef]