Submitted:

27 July 2024

Posted:

30 July 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Experimental Protocols

2.1. Material

2.2. Electrochemical/Cathodic Charging and Electrolyte

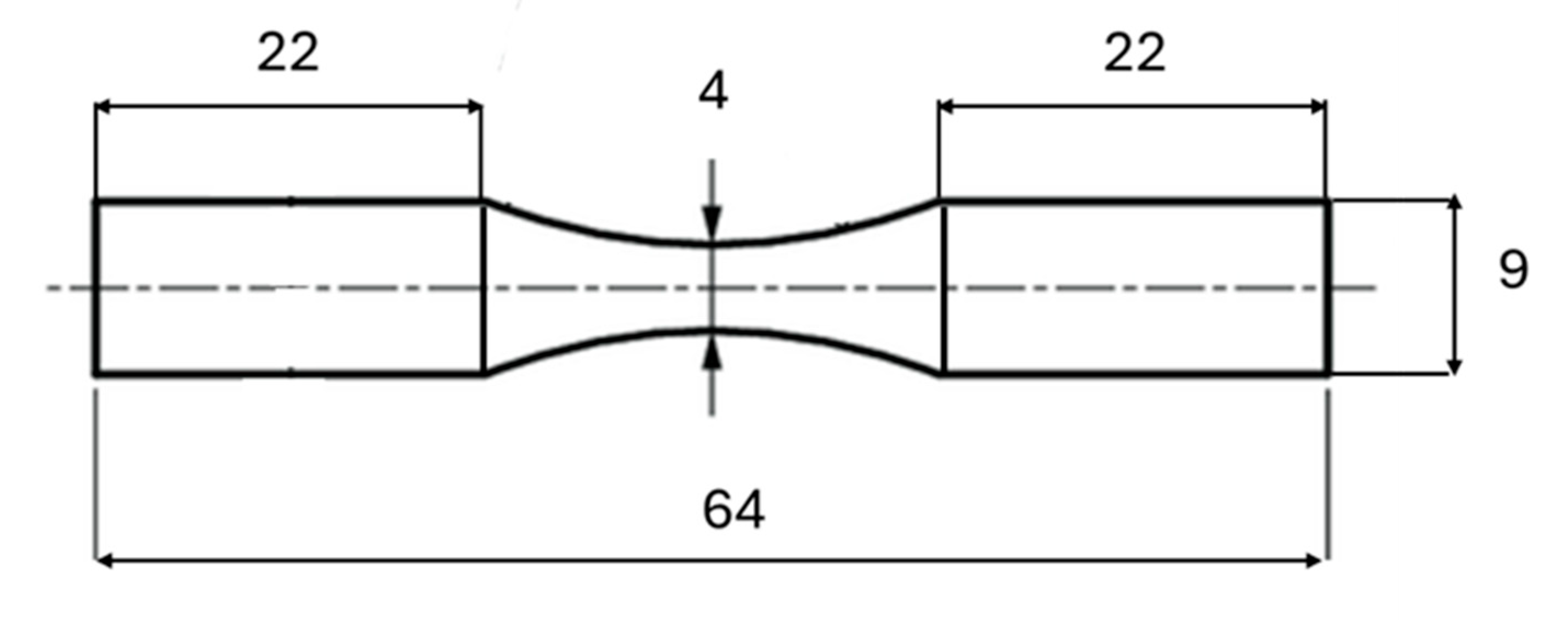

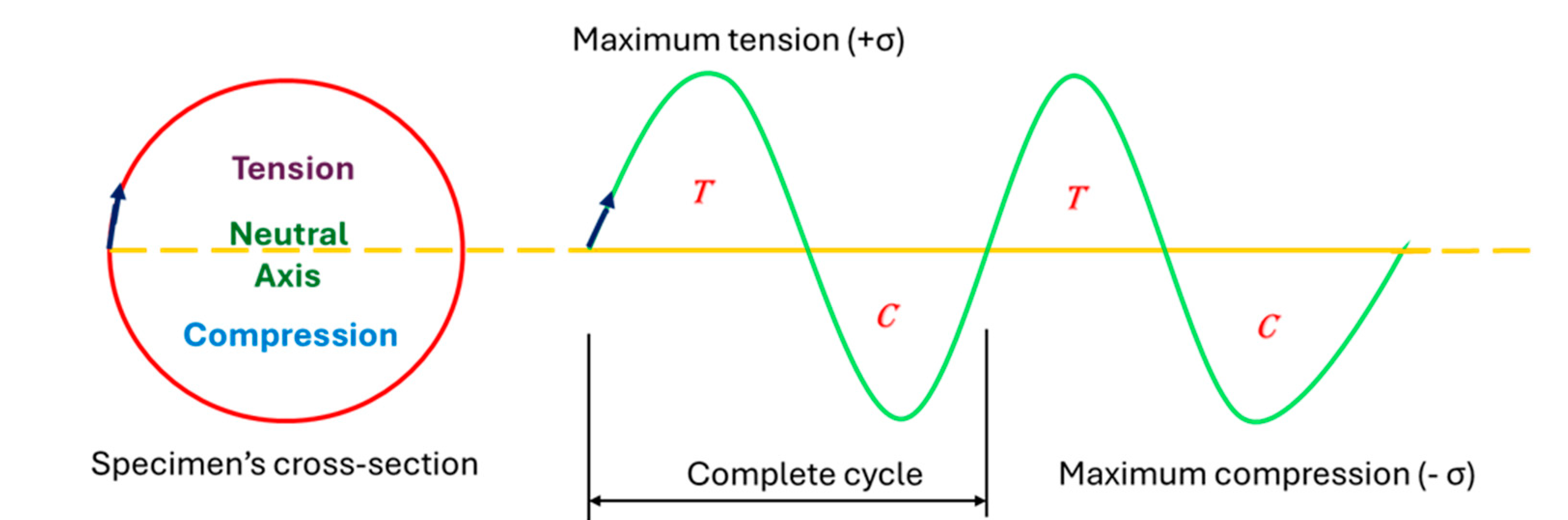

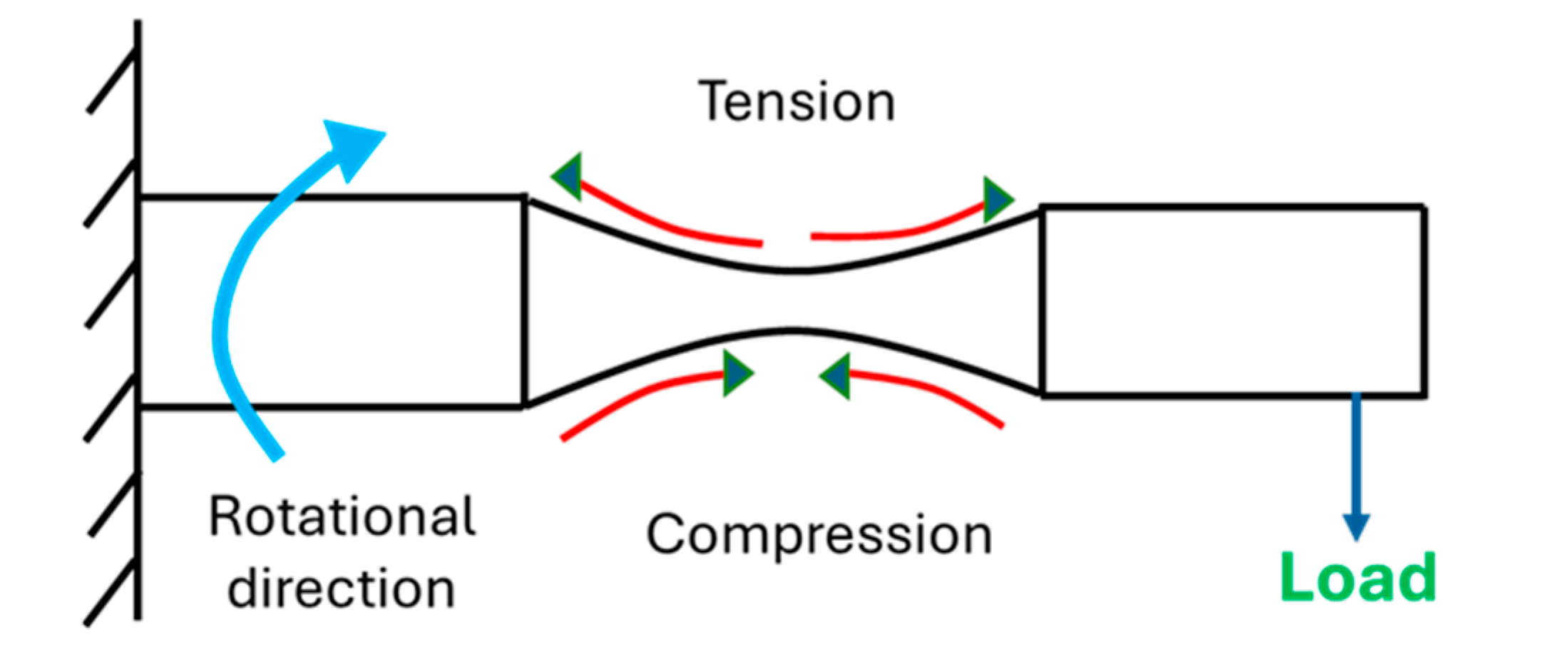

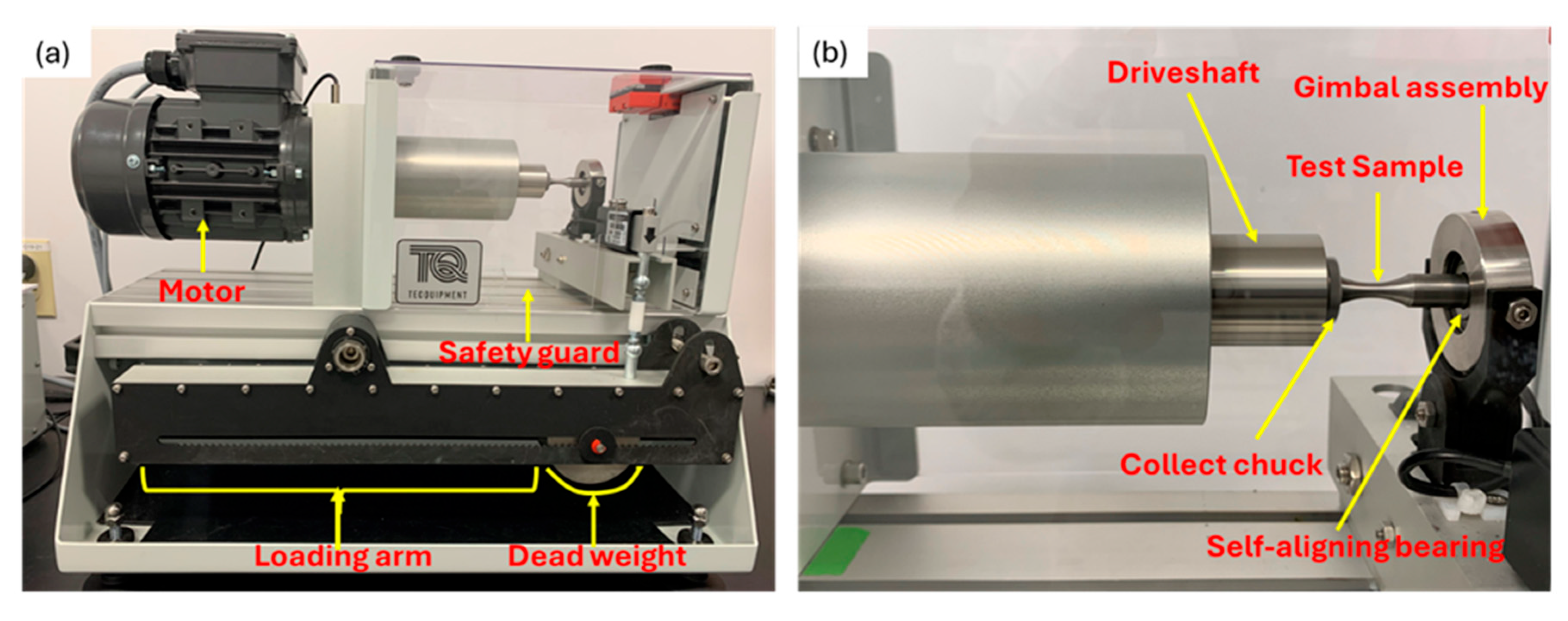

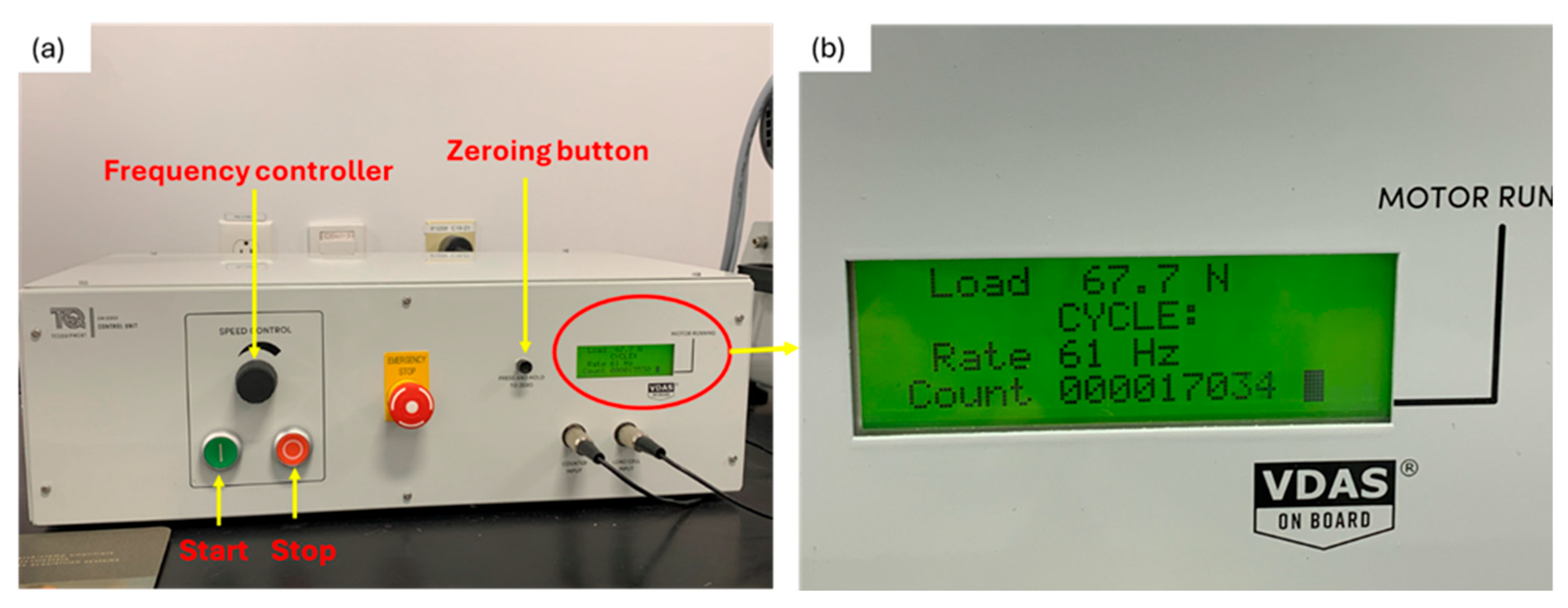

2.3. Fatigue Testing

3. Results and Discussion

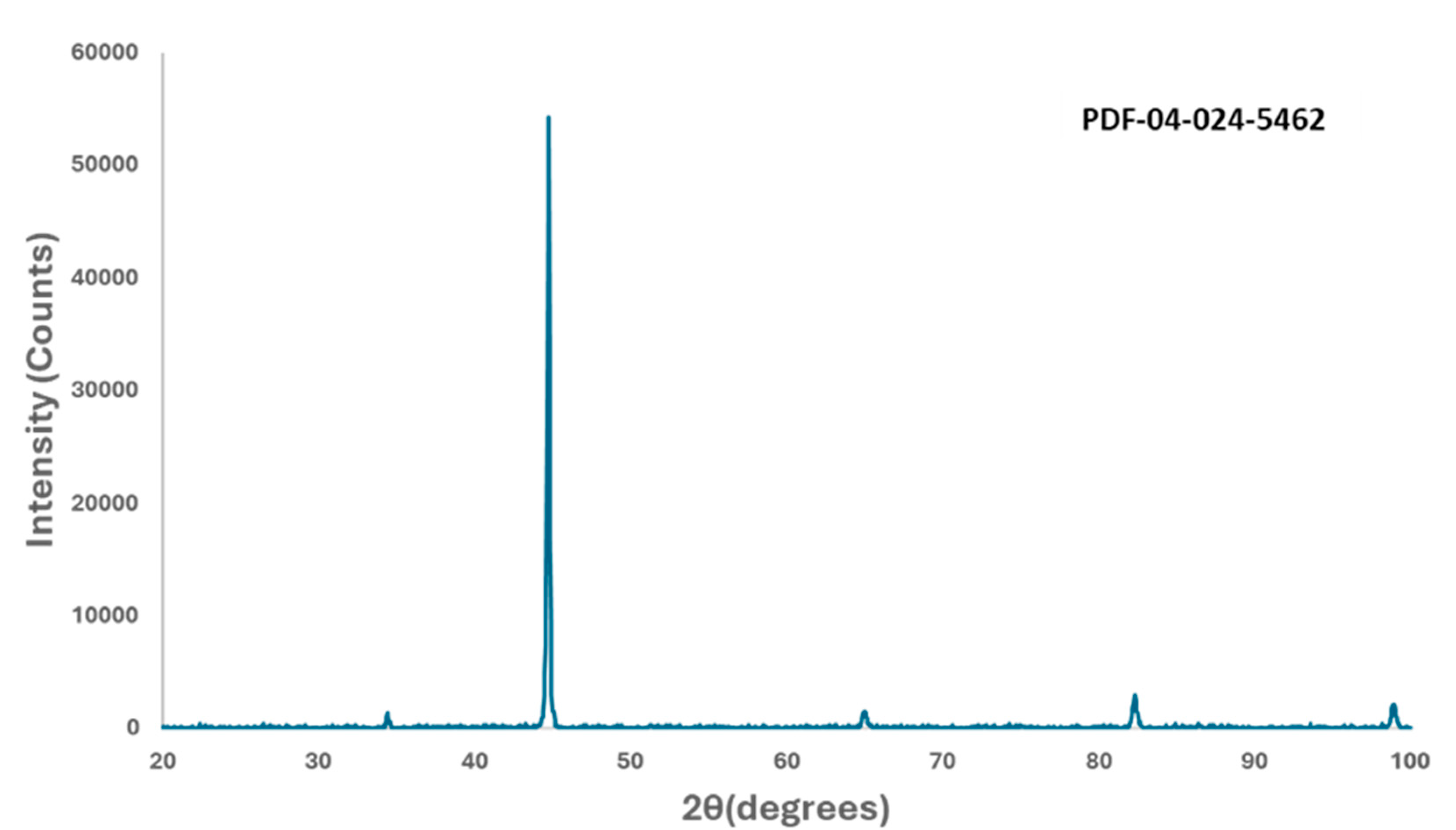

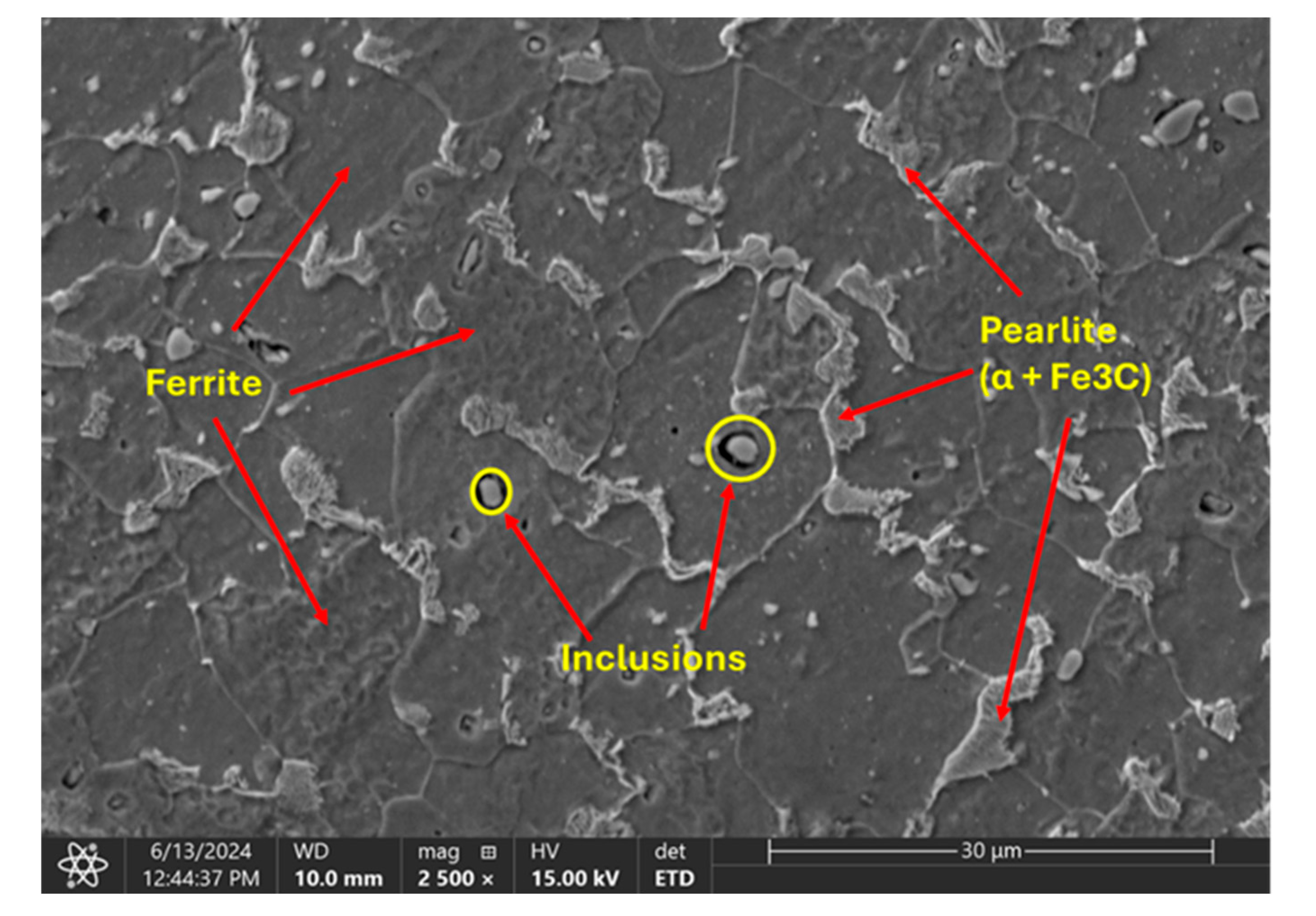

3.1. Microstructure

3.2. Fatigue Response to Varying Hydrogenating Conditions

3.3. Analysis of Fracture Surfaces

3.3.1. Uncharged Specimen

3.3.2. Moderately Charged Samples

3.3.3. Highly Charged Samples

| Net Counts | |||

| Element | Point 1 | Point 2 | Point 3 |

| C | 15100 | 1923 | 1281 |

| F | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| S | 220886 | 6126 | 781 |

| Mn | 95305 | 51447 | 11177 |

| Fe | 11571 | 17232 | 21256 |

| Si | 0 | 175 | 0 |

4. Conclusions

- This study on the fatigue behavior of cold-finished mild steel under varying conditions of hydrogen charging has provided substantial understandings into the material's response to hydrogen permeation.

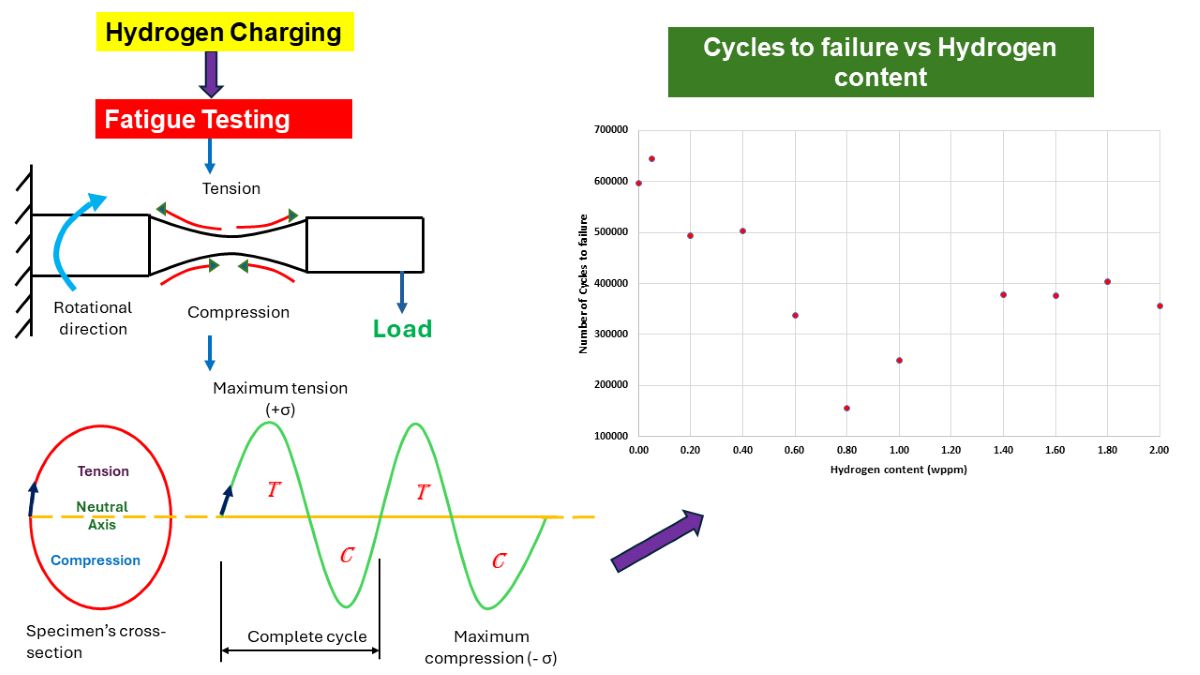

- The experimental results established that the number of cycles to failure initially decreased with increasing hydrogen concentration, dropping from 596,057 cycles for uncharged samples (0.00 wppm) to 154,925 cycles at an intermediate hydrogen concentration (0.80wppm). This decline highlights the damaging impact of hydrogen embrittlement, which accelerates fatigue crack initiation and propagation.

- Interestingly, at very high hydrogen concentrations, the number of cycles to failure showed an unexpected increase in number of cycles to failure of 249,775 for 1.00wppm through to 355,407 for 2.00wppm.

- This suggests the presence of a threshold beyond which additional hydrogen may alter the dominant fatigue mechanisms, possibly due to changes in crack propagation behavior or the saturation of hydrogen-related defects and mechanisms such as HELP and HEDE.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Nagao, A.; Dadfarnia, M.; Somerday, B.P.; Sofronis, P.; Ritchie, R.O. Hydrogen-Enhanced-Plasticity Mediated Decohesion for Hydrogen-Induced Intergranular and “Quasi-Cleavage” Fracture of Lath Martensitic Steels. J. Mech. Phys. Solids 2018, 112, 403–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Troiano, A.R. The Role of Hydrogen and Other Interstitials in the Mechanical Behavior of Metals. Metallogr. Microstruct. Anal. 2016, 5, 557–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Liu, C.; Wang, X.; Dai, Y.; Zhan, M.; Liu, Y.; Yang, K.; He, C.; Wang, Q. Effect of Microstructure on Small Fatigue Crack Initiation and Early Propagation Behavior in Super Austenitic Stainless Steel 654SMO. Int. J. Fatigue 2024, 179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brem, J.C.; Barlat, F.; Dick, R.E.; Yoon, J.-W. Characterizations of Aluminum Alloy Sheet Materials Numisheet 2005.; United States, 2005; Vol. 778.

- Xue, Y.; Solanki, K.; Steele, G.; Horstemeyer, M.; Newman, J. Quantitative Uncertainty Analysis for a Mechanistic Multistage Fatigue Model. In. 2012,. [CrossRef]

- Park, J.Y.; Park, Y.C.; Kim, H.-K. A Methodology for Fatigue Reliability Assessment Considering Stress Range Distribution Truncation. Int. J. Steel Struct. 2018, 18, 1242–1251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huffman, P.J.; Correia, J.A.F.O.; Mourão, A.; Bittencourt, T.; Calçada, R. Predicted Distribution in Measured Fatigue Life from Expected Distribution in Cyclic Stress–Strain Properties Using a Strain-Energy Based Damage Model. In Proceedings of the Structural Integrity and Fatigue Failure Analysis; Lesiuk, G., Szata, M., Blazejewski, W., Jesus, A.M.P. de, Correia, J.A.F.O., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, 2022; pp. 65–71. [Google Scholar]

- Koster, M.; Lis, A.; Lee, W.J.; Kenel, C.; Leinenbach, C. Influence of Elastic–Plastic Base Material Properties on the Fatigue and Cyclic Deformation Behavior of Brazed Steel Joints. Int. J. Fatigue 2016, 82, 49–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Čanžar, P.; Tonković, Z.; Kodvanj, J. Microstructure Influence on Fatigue Behaviour of Nodular Cast Iron. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2012, 556, 88–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ponson, L.; Bonamy, D. Crack Propagation in Brittle Heterogeneous Solids: Material Disorder and Crack Dynamics. In Proceedings of the IUTAM Symposium on Dynamic Fracture and Fragmentation; Ravi-Chandar, K., Vogler, T.J., Eds.; Springer Netherlands: Dordrecht, 2010; pp. 21–31. [Google Scholar]

- Song, S.W.; Kwon, Y.J.; Lee, T.; Lee, C.S. Effect of Al Addition on Low-Cycle Fatigue Properties of Hydrogen-Charged High-Mn TWIP Steels. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2016, 677, 421–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Ma, L.; Xie, H.; Zhao, F.; Ye, Y.; Zhang, L. Effects of External Hydrogen on Hydrogen-Assisted Crack Initiation in Type 304 Stainless Steel. Anti-Corros Methods M. 2020, 67, 331–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pal, S.; Singh Raman, R.K. Determination of Threshold Stress Intensity Factor for Stress Corrosion Cracking (KISCC) of Steel Heat Affected Zone. Corros. Sci. 2009, 51, 2443–2449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Pannemaecker, A.; Fouvry, S.; Brochu, M.; Buffiere, J.Y. Identification of the Fatigue Stress Intensity Factor Threshold for Different Load Ratios R: From Fretting Fatigue to C(T) Fatigue Experiments. In Proceedings of the International Journal of Fatigue; Elsevier Ltd, January 1 2016; Vol. 82; pp. 211–225. [Google Scholar]

- Kitahara, G.; Asada, T.; Matsuoka, H. Effects of Diffusible Hydrogen on Fatigue Life of Spot Welds in High-Tensile-Strength Steel Sheets. ISIJ Int. 2023, 63, 889–898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Djukic, M.B.; Bakic, G.M.; Sijacki Zeravcic, V.; Sedmak, A.; Rajicic, B. The Synergistic Action and Interplay of Hydrogen Embrittlement Mechanisms in Steels and Iron: Localized Plasticity and Decohesion. Eng. Fract. Mech. 2019, 216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Örnek, C.; Şeşen, B.M.; Ürgen, M.K. Understanding Hydrogen-Induced Strain Localization in Super Duplex Stainless Steel Using Digital Image Correlation Technique. Met. Mater. Int. 2022, 28, 475–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neikter, M.; Colliander, M.; de Andrade Schwerz, C.; Hansson, T.; Åkerfeldt, P.; Pederson, R.; Antti, M.L. Fatigue Crack Growth of Electron Beam Melted TI-6AL-4V in High-Pressure Hydrogen. Materials 2020, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beachem, C.D. A New Model for Hydrogen-Assisted Cracking (Hydrogen “Embrittlement”);

- Lynch, S. Hydrogen Embrittlement Phenomena and Mechanisms. Corros. Rev. 2012, 30, 105–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oag-bvg Independent Auditor’s Report | 2022 Reports of the Commissioner of the Environment and Sustainable Development to the Parliament of Canada Hydrogen’s Potential to Reduce Greenhouse Gas Emissions H 2.; 2022.

- Davis, M.; Okunlola, A.; Di Lullo, G.; Giwa, T.; Kumar, A. Greenhouse Gas Reduction Potential and Cost-Effectiveness of Economy-Wide Hydrogen-Natural Gas Blending for Energy End Uses. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2023, 171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Si, X.; Lu, R.; Zhao, Z.; Yang, X.; Wang, F.; Jiang, H.; Luo, X.; Wang, A.; Feng, Z.; Xu, J.; et al. Catalytic Production of Low-Carbon Footprint Sustainable Natural Gas. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, T.; Shrestha, E.; Hamburg, S.P.; Kupers, R.; Ocko, I.B. Climate Impacts of Hydrogen and Methane Emissions Can Considerably Reduce the Climate Benefits across Key Hydrogen Use Cases and Time Scales. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2023. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Standard Guide for Preparation of Metallographic Specimens 1. [CrossRef]

- Designation: E407 − 07 (Reapproved 2015) ´1 Standard Practice for Microetching Metals and Alloys 1. [CrossRef]

- Standard Test Method for Rockwell Hardness of Plastics and Electrical Insulating Materials 1. [CrossRef]

- Designation: E18 − 20 Standard Test Methods for Rockwell Hardness of Metallic Materials 1,2. [CrossRef]

- Sey, E.; Farhat, Z.N. Evaluating the Effect of Hydrogen on the Tensile Properties of Cold-Finished Mild Steel. Crystals (Basel) 2024, 14, 529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Ghadiani, H.; Jalilvand, V.; Alam, T.; Farhat, Z.; Islam, M.A. Hydrogen Impact: A Review on Diffusibility, Embrittlement Mechanisms, and Characterization. Materials 2024, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lipski, A. Rapid Determination of the Wöhler’s Curve for Aluminum Alloy 2024-T3 by Means of the Thermographic Method. In Proceedings of the AIP Conference Proceedings; American Institute of Physics Inc., October 20 2016; Vol. 1780. [Google Scholar]

- Mlikota, M.; Schmauder, S.; Božić, Ž. Calculation of the Wöhler (S-N) Curve Using a Two-Scale Model. Int. J. Fatigue 2018, 114, 289–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wasim, M.; Djukic, M.B.; Ngo, T.D. Influence of Hydrogen-Enhanced Plasticity and Decohesion Mechanisms of Hydrogen Embrittlement on the Fracture Resistance of Steel. Eng. Fail. Anal. 2021, 123, 105312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shibata, A.; Yonemura, T.; Momotani, Y.; Park, M.; Takagi, S.; Madi, Y.; Besson, J.; Tsuji, N. Effects of Local Stress, Strain, and Hydrogen Content on Hydrogen-Related Fracture Behavior in Low-Carbon Martensitic Steel. Acta. Mater. 2021, 210, 116828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsunaga, H.; Takakuwa, O.; Yamabe, J.; Matsuoka, S. Hydrogen-Enhanced Fatigue Crack Growth in Steels and Its Frequency Dependence. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. A 2017, 375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Traidia, A.; Chatzidouros, E.; Jouiad, M. Review of Hydrogen-Assisted Cracking Models for Application to Service Lifetime Prediction and Challenges in the Oil and Gas Industry. Corros. Rev. 2018, 36, 323–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polyanskiy, V.A.; Belyaev, A.K.; Sedova, Yu.S.; Yakovlev, Yu.A. Mesoeffect of the Dual Mechanism of Hydrogen-Induced Cracking. Phys. Mesomech. 2022, 25, 466–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, W.; Trtik, P.; Ma, F.; Jia, Y.; Li, J.; Bertsch, J. Hydrogen Diffusion and Precipitation under Non-Uniform Stress in Duplex Zirconium Nuclear Fuel Cladding Investigated by High-Resolution Neutron Imaging. J. Nucl. Mater. 2022, 570, 153971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Element | Fe | C | Mn | Si | S | Cu | Ni | Cr |

| Composition (wt%) | 98.14 | 0.14 | 0.47 | 0.25 | 0.004 | 0.08 | 0.04 | 0.07 |

| Element | Point 1 | Point 2 | Point 3 |

|---|---|---|---|

| C | 17068 | 15750 | 19599 |

| Si | 3393 | 1731 | 1585 |

| S | 193066 | 181111 | 156222 |

| Mn | 89306 | 85520 | 75365 |

| Fe | 12081 | 16520 | 28773 |

| Weight % | |||||||

| Element | Point 4 | Point 5 | Point 6 | Point 7 | Region 8 | Region 9 | Region 10 |

| C | 6.7 | 9.2 | 5.6 | 17.0 | 5.7 | 0.0 | 5.9 |

| Al | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| Si | 0.1 | 0.2 | 0.3 | 0.2 | 0.1 | 0.2 | 0.2 |

| S | 0.0 | 0.1 | 0.6 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.0 | 0.1 |

| Mn | 0.8 | 0.9 | 0.9 | 1.0 | 0.7 | 0.6 | 0.7 |

| Fe | 92.4 | 89.6 | 92.6 | 81.7 | 93.4 | 99.2 | 93.1 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).