Submitted:

26 July 2024

Posted:

29 July 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

2.2. Synthesis

2.3. Characterization

3. Results

3.1. Element Chemical Analysis

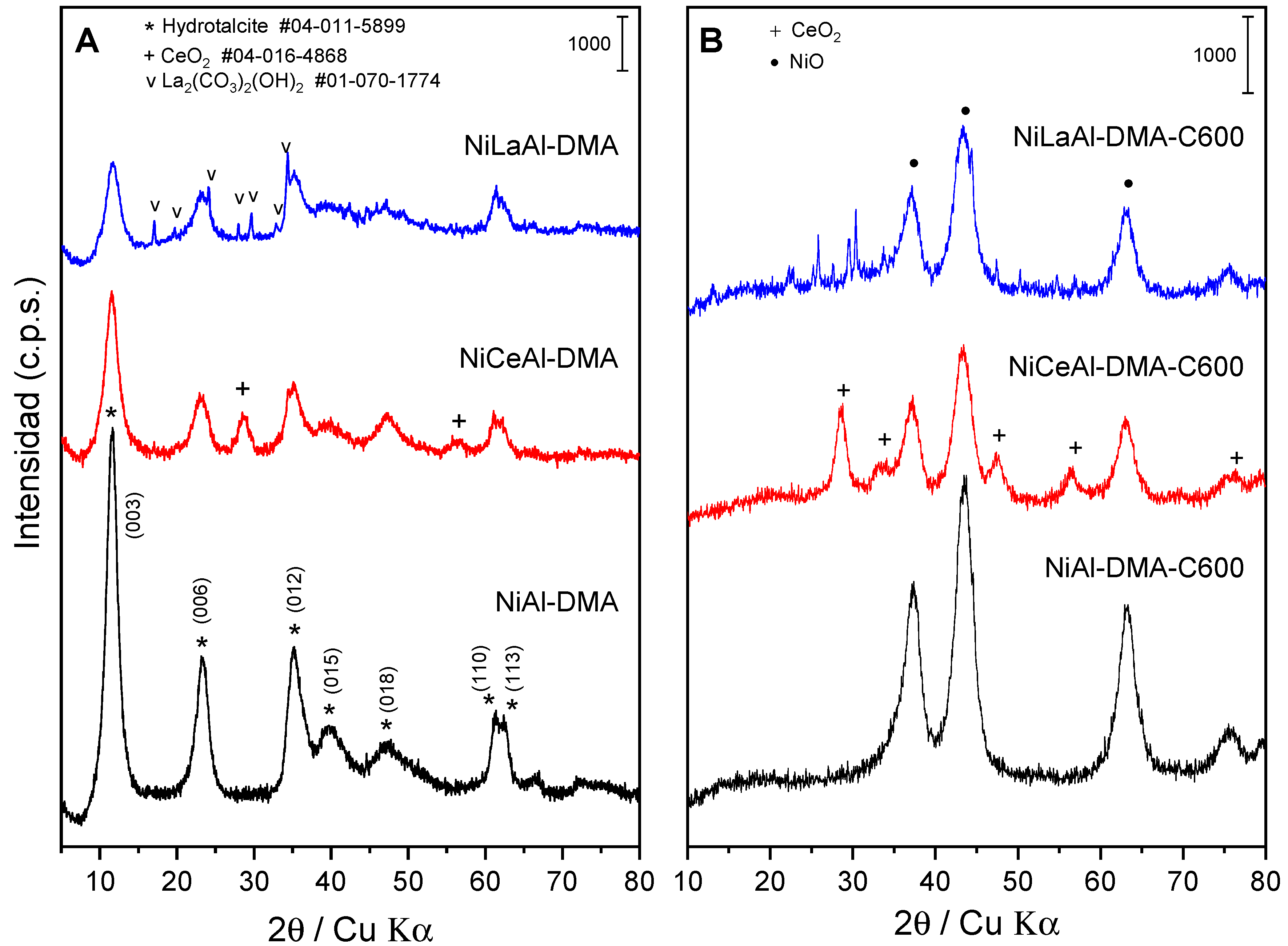

3.2. Powder X-ray Diffraction (PXRD)

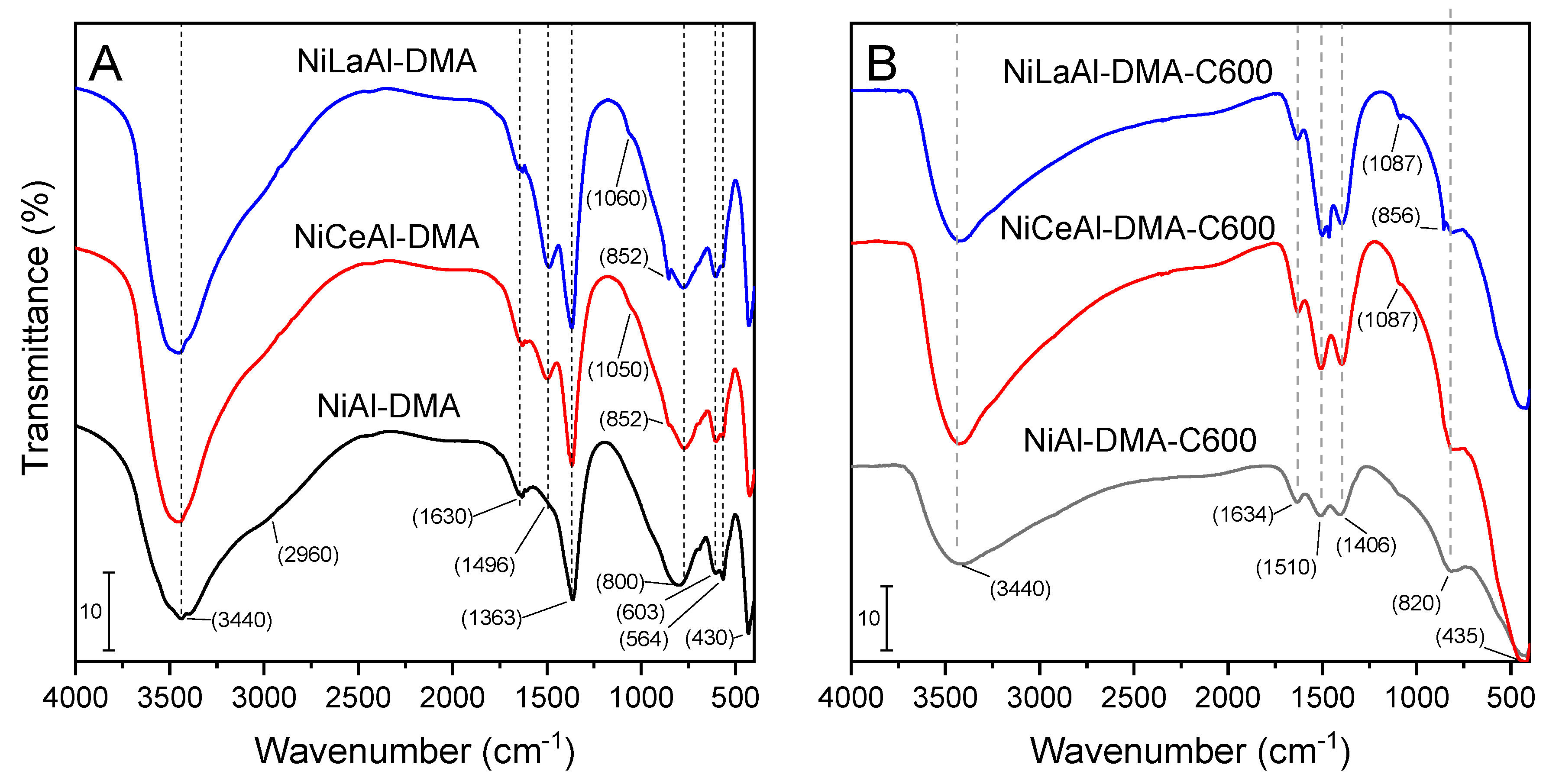

3.3. FT-IR Spectroscopy

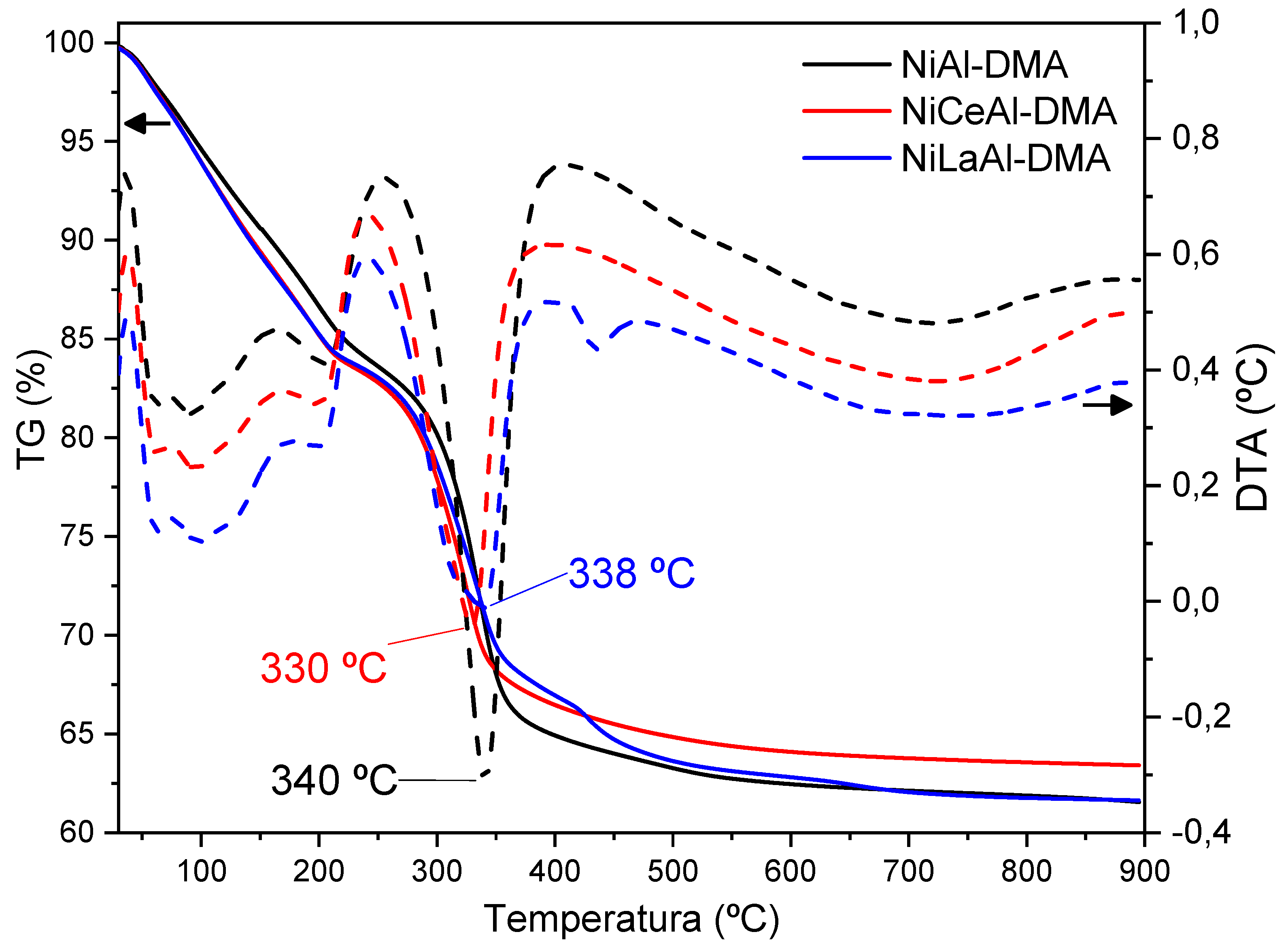

3.4. Thermal Analysis

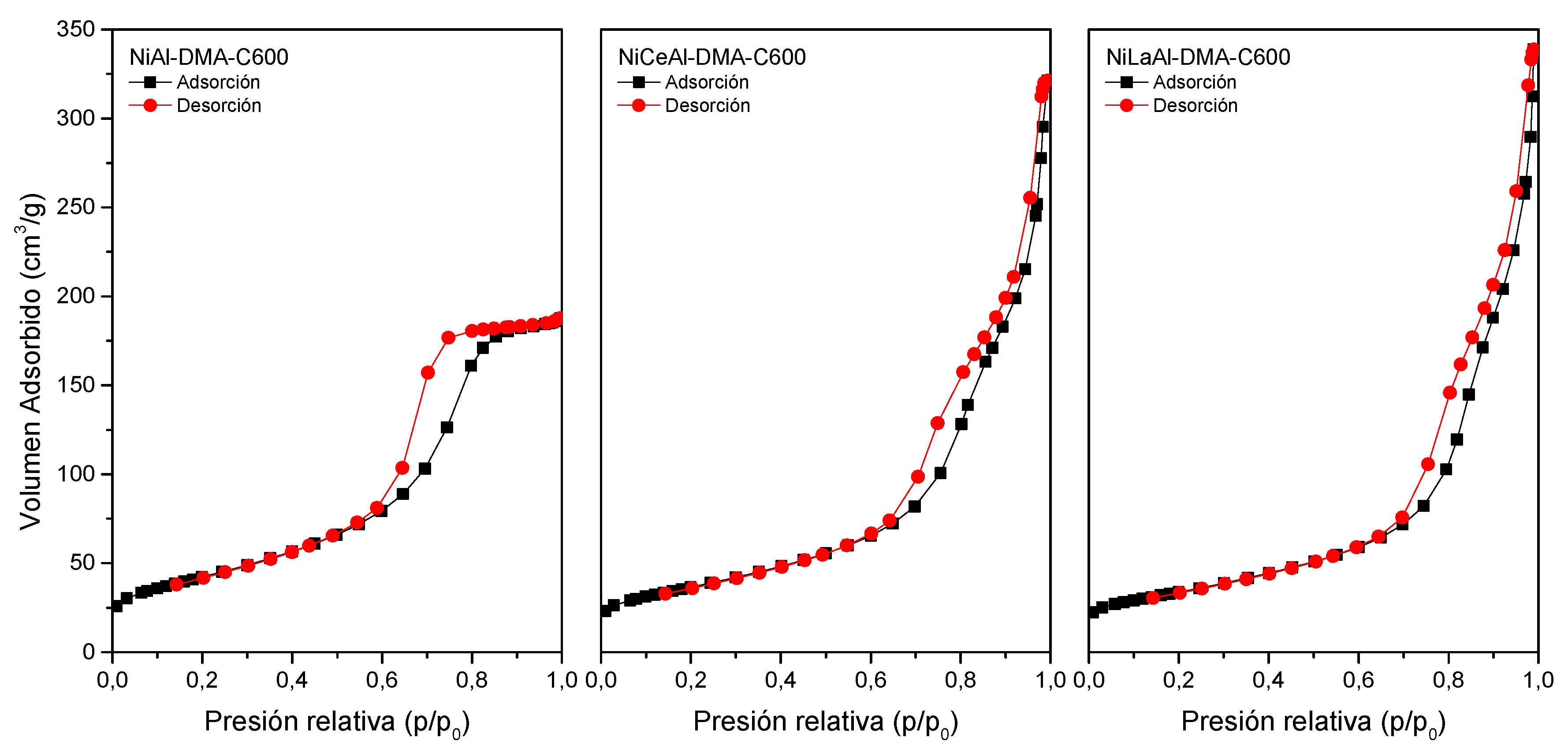

3.5. Specific Surface Area and Porosity

3.6. UV-Visible Diffuse Reflectance Spectroscopy

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

References

- Alivisatos, A.P. Semiconductor Clusters, Nanocrystals, and Quantum Dots. Science (1979) 1996, 271, 933–937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fasol, G. Nanowires: Small Is Beautiful. Science (1979) 1998, 280, 545–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salavati-Niasari, M.; Mohandes, F.; Davar, F.; Mazaheri, M.; Monemzadeh, M.; Yavarinia, N. Preparation of NiO Nanoparticles from Metal-Organic Frameworks via a Solid-State Decomposition Route. Inorganica Chim Acta 2009, 362, 3691–3697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.Y.; Kim, H.M.; Shin, D.H.; Ihn, K.J. Synthesis of CdS Nanoparticles Dispersed within Poly(Urethane Aerylate-Co-Styrene) Films Using an Amphiphilic Urethane Acrylate Nonionomer. Macromol Chem Phys 2006, 207, 925–932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jun, Y.W.; Jung, Y.Y.; Cheon, J. Architectural Control of Magnetic Semiconductor Nanocrystals. J Am Chem Soc 2002, 124, 615–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peng, X. Mechanisms for the Shape-Control and Shape-Evolution of Colloidal Semiconductor Nanocrystals. Advanced Materials 2003, 15, 459–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manna, L.; Scher, E.C.; Li, L.S.; Alivisatos, A.P. Epitaxial Growth and Photochemical Annealing of Graded CdS/ZnS Shells on Colloidal CdSe Nanorods. J Am Chem Soc 2002, 124, 7136–7145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aricò, A.S.; Bruce, P.; Scrosati, B.; Tarascon, J.-M.; Van Schalkwijk, W. Nanostructured Materials for Advanced Energy Conversion and Storage Devices; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Ansari, F.; Bazarganipour, M.; Salavati-Niasari, M. NiTiO3/NiFe2O4 Nanocomposites: Simple Sol-Gel Auto-Combustion Synthesis and Characterization by Utilizing Onion Extract as a Novel Fuel and Green Capping Agent. Mater Sci Semicond Process 2016, 43, 34–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salavati-Niasari, M.; Davar, F.; Fereshteh, Z. Synthesis of Nickel and Nickel Oxide Nanoparticles via Heat-Treatment of Simple Octanoate Precursor. J Alloys Compd 2010, 494, 410–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salavati-Niasari, M.; Mir, N.; Davar, F. Synthesis and Characterization of NiO Nanoclusters via Thermal Decomposition. Polyhedron 2009, 28, 1111–1114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, L.; Su, G.; Liu, W.; Cao, L.; Wang, J.; Dong, Z.; Song, M. Optical and Electrochemical Properties of Cu-Doped NiO Films Prepared by Electrochemical Deposition. Appl Surf Sci 2011, 257, 3974–3979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khodair, Z.T.; Ibrahim, N.M.; Kadhim, T.J.; Mohammad, A.M. Synthesis and Characterization of Nickel Oxide (NiO) Nanoparticles Using an Environmentally Friendly Method, and Their Biomedical Applications. Chem Phys Lett 2022, 797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, W.; Chandra Bhatt, S.; Verma, M.; Kumar, V.; Kim, H. A Review on Current Trends in the Green Synthesis of Nickel Oxide Nanoparticles, Characterizations, and Their Applications. Environ Nanotechnol Monit Manag 2022, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhas, S.D.; Maldar, P.S.; Patil, M.D.; Nagare, A.B.; Waikar, M.R.; Sonkawade, R.G.; Moholkar, A.V. Synthesis of NiO Nanoparticles for Supercapacitor Application as an Efficient Electrode Material. Vacuum 2020, 181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christian Enger, B.; Lødeng, R.; Holmen, A. A Review of Catalytic Partial Oxidation of Methane to Synthesis Gas with Emphasis on Reaction Mechanisms over Transition Metal Catalysts. Appl Catal A Gen 2008, 346, 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, P.H.; Sanghez De Luna, G.; Ospitali, F.; Fornasari, G.; Vaccari, A.; Benito, P. Open-Cell Foams Coated by Ni/X/Al Hydrotalcite-Type Derived Catalysts (X = Ce, La, Y) for CO2 Methanation. Journal of CO2 Utilization 2020, 42, 101327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, P.H.; Sanghez De Luna, G.; Poggi, A.; Nota, M.; Rodríguez-Castellón, E.; Fornasari, G.; Vaccari, A.; Benito, P. Ru−CeO2 and Ni−CeO2 Coated on Open-Cell Metallic Foams by Electrodeposition for the CO2 Methanation. Ind Eng Chem Res 2021, 60, 6730–6741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, P.H.; de Luna, G.S.; Angelucci, S.; Canciani, A.; Jones, W.; Decarolis, D.; Ospitali, F.; Aguado, E.R.; Rodríguez-Castellón, E.; Fornasari, G.; et al. Understanding Structure-Activity Relationships in Highly Active La Promoted Ni Catalysts for CO2 Methanation. Appl Catal B 2020, 278, 119256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, P.; Zhu, M.; Tian, Z.; Han, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Zhou, T.; Kang, L.; Dan, J.; Guo, X.; Yu, F.; et al. Two-Dimensional Layered Double Hydroxide Derived from Vermiculite Waste Water Supported Highly Dispersed Ni Nanoparticles for CO Methanation. Catalysts 2017, 7, 79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Li, P.; Zhu, M.; Tian, Z.; Dan, J.; Li, J.; Dai, B.; Yu, F. Ultralow-Weight Loading Ni Catalyst Supported on Two-Dimensional Vermiculite for Carbon Monoxide Methanation. Chin J Chem Eng 2018, 26, 1873–1878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosny, N.M. Synthesis, Characterization and Optical Band Gap of NiO Nanoparticles Derived from Anthranilic Acid Precursors via a Thermal Decomposition Route. Polyhedron 2011, 30, 470–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, M.; Qiu, T.; Tang, B.; Zhang, G.; Yao, R.; Xu, W.; Chen, J.; Fu, X.; Ning, H.; Peng, J. Temperature-Controlled Crystal Size of Wide Band Gap Nickel Oxide and Its Application in Electrochromism. Micromachines 2021, 12, 80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, T.Y.; Ho, M.K.; Hsu, T.E.; Chiu, H.H.; Wu, K.T.; Peng, J.C.; Wu, C.M.; Chan, T.S.; Vijaya Kumar, B.; Muralidhar Reddy, P.; et al. Antiferromagnetic Spin Correlations above the Bulk Ordering Temperature in NiO Nanoparticles: Effect of Extrinsic Factors. Appl Surf Sci 2022, 578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Napari, M.; Huq, T.N.; Maity, T.; Gomersall, D.; Niang, K.M.; Barthel, A.; Thompson, J.E.; Kinnunen, S.; Arstila, K.; Sajavaara, T.; et al. Antiferromagnetism and P-Type Conductivity of Nonstoichiometric Nickel Oxide Thin Films. InfoMat 2020, 2, 769–774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Purushothaman, K.K.; Joseph Antony, S.; Muralidharan, G. Optical, Structural and Electrochromic Properties of Nickel Oxide Films Produced by Sol-Gel Technique. Solar Energy 2011, 85, 978–984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danial, A.S.; Saleh, M.M.; Salih, S.A.; Awad, M.I. On the Synthesis of Nickel Oxide Nanoparticles by Sol–Gel Technique and Its Electrocatalytic Oxidation of Glucose. J Power Sources 2015, 293, 101–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gondal, M.A.; Saleh, T.A.; Drmosh, Q.A. Synthesis of Nickel Oxide Nanoparticles Using Pulsed Laser Ablation in Liquids and Their Optical Characterization. Appl Surf Sci 2012, 258, 6982–6986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Kemary, M.; Nagy, N.; El-Mehasseb, I. Nickel Oxide Nanoparticles: Synthesis and Spectral Studies of Interactions with Glucose. Mater Sci Semicond Process 2013, 16, 1747–1752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Yan, R.; Xiao, B.; Liang, D.T.; Lee, D.H. Preparation of Nano-NiO Particles and Evaluation of Their Catalytic Activity in Pyrolyzing Biomass Components. Energy and Fuels 2008, 22, 16–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Algarou, N.A.; Slimani, Y.; Almessiere, M.A.; Alahmari, F.S.; Vakhitov, M.G.; Klygach, D.S.; Trukhanov, S.V.; Trukhanov, A.V.; Baykal, A. Magnetic and Microwave Properties of SrFe12O19/MCe0.04Fe1.96O4 (M = Cu, Ni, Mn, Co and Zn) Hard/Soft Nanocomposites. Journal of Materials Research and Technology 2020, 9, 5858–5870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trukhanov, A.V.; Algarou, N.A.; Slimani, Y.; Almessiere, M.A.; Baykal, A.; Tishkevich, D.I.; Vinnik, D.A.; Vakhitov, M.G.; Klygach, D.S.; Silibin, M.V.; et al. Peculiarities of the Microwave Properties of Hard–Soft Functional Composites SrTb0.01Tm0.01Fe11.98O19–AFe2O4 (A = Co, Ni, Zn, Cu, or Mn). RSC Adv 2020, 10, 32638–32651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, L.; Cheng, B.; Zhang, L.; Yu, J. In Situ Irradiated XPS Investigation on S-Scheme TiO2 @ZnIn2S4 Photocatalyst for Efficient Photocatalytic CO2 Reduction. Small 2021, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, Q.; Zhang, L.; Cheng, B.; Fan, J.; Yu, J. S-Scheme Heterojunction Photocatalyst. Chem 2020, 6, 1543–1559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richard, D.; Errico, L.A.; Rentería, M. Electronic, Structural, and Hyperfine Properties of Pure and Cd-Doped Hexagonal La2O3 Semiconductor. Comput Mater Sci 2015, 102, 119–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohmi, S.; Kobayashi, C.; Kashiwagi, I.; Ohshima, C.; Ishiwara, H.; Iwai, H. Characterization of La2O3 and Yb2O3 Thin Films for High-k Gate Insulator Application. J Electrochem Soc 2003, 150, F134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ismail, W.; Belal, A.; Abdo, W.; El-Shaer, A. Investigating the Physical and Electrical Properties of La2O3 via Annealing of La(OH)3. Sci Rep 2024, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Quan, Y.; Liu, M.; Wu, H.; Tian, X.; Dou, L.; Ren, C.; Wang, Z. Construction of La2O3/AgCl S-Scheme Heterojunction with Interfacial Chemical Bond for Efficient Photocatalytic Degradation of Bisphenol A. Appl Surf Sci 2024, 664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balavi, H.; Samadanian-Isfahani, S.; Mehrabani-Zeinabad, M.; Edrissi, M. Preparation and Optimization of CeO2 Nanoparticles and Its Application in Photocatalytic Degradation of Reactive Orange 16 Dye. Powder Technol 2013, 249, 549–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, T.; Wang, X.; Feng, G. Synthesis of Novel CeO2 Microspheres with Enhanced Solar Light Photocatalyic Properties. Mater Lett 2013, 100, 36–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, P.; Chen, X.; Li, Y.; Schwank, J.W. A Review on Oxygen Storage Capacity of CeO2-Based Materials: Influence Factors, Measurement Techniques, and Applications in Reactions Related to Catalytic Automotive Emissions Control. Catal Today 2019, 327, 90–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, C.H.; Xie, S.; Yu, M.; Yang, Y.; Lu, X.; Tong, Y. Facile Synthesis of Large-Area CeO2/ZnO Nanotube Arrays for Enhanced Photocatalytic Hydrogen Evolution. J Power Sources 2014, 247, 545–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faisal, M.; Bahadar Khan, S.; Rahman, M.M.; Jamal, A.; Akhtar, K.; Abdullah, M. Role of ZnO-CeO2 Nanostructures as a Photo-Catalyst and Chemi-Sensor; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Li, C.; Zhang, X.; Dong, W.; Liu, Y. High Photocatalytic Activity Material Based on High-Porosity ZnO/CeO2 Nanofibers. Mater Lett 2012, 80, 145–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Chen, R.; Zhang, X.; Shu, S.; Xiong, J.; Zheng, Y.; Dong, W. Electrospinning of CeO2-ZnO Composite Nanofibers and Their Photocatalytic Property. Mater Lett 2011, 65, 1327–1330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sherly, E.D.; Vijaya, J.J.; Kennedy, L.J. Effect of CeO2 Coupling on the Structural, Optical and Photocatalytic Properties of ZnO Nanoparticle. J Mol Struct 2015, 1099, 114–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, C.; Jiang, G.; Li, Y.; Jin, Z. NiO and Co1.29Ni1.71O4 Derived from NiCo LDH Form S-Scheme Heterojunction for Efficient Photocatalytic Hydrogen Evolution. J Alloys Compd 2022, 904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cavani, F.; Trifirò, F.; Vaccari, A. Hydrotalcite-Type Anionic Clays: Preparation, Properties and Applications. Catal Today 1991, 11, 173–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rives, V. Study of Layered Double Hydroxides by Thermal Methods. In Layered Double Hydroxides: Present and Future; Rives, V., Ed.; NOVA Science Publishers, Inc: New York, 2001; pp. 127–152. [Google Scholar]

- Kameliya, J.; Verma, A.; Dutta, P.; Arora, C.; Vyas, S.; Varma, R.S. Layered Double Hydroxide Materials: A Review on Their Preparation, Characterization, and Applications. Inorganics 2023, 11, 121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; O’hare, D. Recent Advances in the Synthesis and Application of Layered Double Hydroxide (LDH) Nanosheets. Chem Rev 2012, 112, 4124–4155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rives, V. Layered Double Hydroxides: Present and Future; NOVA Science Publishers, Inc: New York, 2001; ISBN 978-1-61209-289-8. [Google Scholar]

- Mandal, S.; Patil, V.S.; Mayadevi, S. Alginate and Hydrotalcite-like Anionic Clay Composite Systems: Synthesis, Characterization and Application Studies. Microporous and Mesoporous Materials 2012, 158, 241–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, P.; Ma, R.; Ma, W.; Wu, J.; Wang, K.; Sasaki, T.; Zhu, H. Highly Selective Charge-Guided Ion Transport through a Hybrid Membrane Consisting of Anionic Graphene Oxide and Cationic Hydroxide Nanosheet Superlattice Units. NPG Asia Mater 2016, 8, e259-10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dutta, K.; Das, S.; Pramanik, A. Concomitant Synthesis of Highly Crystalline Zn-Al Layered Double Hydroxide and ZnO: Phase Interconversion and Enhanced Photocatalytic Activity. J Colloid Interface Sci 2012, 366, 28–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Song, F.; Hu, X. Exfoliation of Layered Double Hydroxides for Enhanced Oxygen Evolution Catalysis. Nat Commun 2014, 5, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fan, G.; Li, F.; Evans, D.G.; Duan, X. Catalytic Applications of Layered Double Hydroxides: Recent Advances and Perspectives. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2014, 43, 7040–7066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fan, M.T.; Miao, K.P.; Lin, J.D.; Zhang, H.Bin; Liao, D.W. Mg-Al Oxide Supported Ni Catalysts with Enhanced Stability for Efficient Synthetic Natural Gas from Syngas. Appl Surf Sci 2014, 307, 682–688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, A.I.; Lei, L.; Norquist, A.J.; O’Hare, D. Intercalation and Controlled Release of Pharmaceutically Active Compounds from a Layered Double Hydroxide. Chemical communications 2001, 2342–2343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peng, F.; Wang, D.; Cao, H.; Liu, X. Loading 5-Fluorouracil into Calcined Mg/Al Layered Double Hydroxide on AZ31 via Memory Effect. Mater Lett 2018, 213, 383–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, R.; Park, J.T.; Patel, M.; Dash, J.K.; Gowd, E.B.; Karpoormath, R.; Mishra, A.; Kwak, J.; Kim, J.H. Transition-Metal-Based Layered Double Hydroxides Tailored for Energy Conversion and Storage. J Mater Chem A Mater 2018, 6, 12–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saifullah, B.; Hussein, M.Z. Inorganic Nanolayers: Structure, Preparation, and Biomedical Applications. Int J Nanomedicine 2015, 10, 5609–5633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prasad, C.; Tang, H.; Liu, Q.Q.; Zulfiqar, S.; Shah, S.; Bahadur, I. An Overview of Semiconductors/Layered Double Hydroxides Composites: Properties, Synthesis, Photocatalytic and Photoelectrochemical Applications. J Mol Liq 2019, 289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asghar, H.; Maurino, V.; Iqbal, M.A. Development of Highly Photoactive Mixed Metal Oxide (MMO) Based on the Thermal Decomposition of ZnAl-NO3-LDH. Eng 2024, 5, 589–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.Bin; Ko, E.H.; Park, J.Y.; Oh, J.M. Mixed Metal Oxide by Calcination of Layered Double Hydroxide: Parameters Affecting Specific Surface Area. Nanomaterials 2021, 11, 1153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prabagar, J.S.; Vinod, D.; Sneha, Y.; Anilkumar, K.M.; Rtimi, S.; Wantala, K.; Shivaraju, H.P. Novel GC3N4/MgZnAl-MMO Derived from LDH for Solar-Based Photocatalytic Ammonia Production Using Atmospheric Nitrogen. Environmental Science and Pollution Research 2023, 30, 90383–90396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kloprogge, J.T.; Hickey, L.; Frost, R.L. The Effects of Synthesis PH and Hydrothermal Treatment on the Formation of Zinc Aluminum Hydrotalcites. J Solid State Chem 2004, 177, 4047–4057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, P.; Yu, F.; Altaf, N.; Zhu, M.; Li, J.; Dai, B.; Wang, Q. Two-Dimensional Layered Double Hydroxides for Reactions of Methanation and Methane Reforming in C1 Chemistry. Materials 2018, 11, 221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hwang, S.; Hong, U.G.; Lee, J.; Seo, J.G.; Baik, J.H.; Koh, D.J.; Lim, H.; Song, I.K. Methanation of Carbon Dioxide over Mesoporous Ni-Fe-Al2O3 Catalysts Prepared by a Coprecipitation Method: Effect of Precipitation Agent. Journal of Industrial and Engineering Chemistry 2013, 19, 2016–2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Misol, A.; Labajos, F.M.; Morato, A.; Rives, V. Synthesis of Zn,Al Layered Double Hydroxides in the Presence of Amines. Appl Clay Sci 2020, 189, 105539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, J.G. X-Rays and Their Applications; Plenum/Ros.; Plenum Publishing Corporation: New York, 1966; ISBN 0-306-20021-X. [Google Scholar]

- Jenkins, R.; de Vries, J.L. Worked Examples in X-Ray Analysis, 2nd ed.; Springer: New York, NY, 1970; ISBN 978-1-4899-2649-4. [Google Scholar]

- Brunauer, S.; Emmett, P.H.; Teller, E. Adsorption of Gases in Multimolecular Layers. J Am Chem Soc 1938, 60, 309–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lowell, S.; Shields, J.E.; Thomas, M.A.; Thommes, M. Characterization of Porous Solids and Powders: Surface Area, Pore Size and Density; Springer: The Netherlands, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Makuła, P.; Pacia, M.; Macyk, W. How To Correctly Determine the Band Gap Energy of Modified Semiconductor Photocatalysts Based on UV–Vis Spectra. J Phys Chem Lett 2018, 9, 6814–6817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tauc, J.; Grigorovici, R.; Vancu, A. Optical Properties and Electronic Structure of Amorphous Germanium. physica status solidi (b) 1966, 15, 627–637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drits, V.A.; Bookin, A.S. Crystal Structure and X-Ray Identification of Layered Double Hydroxides. In Layered Double Hydroxides: Present and Future; Rives, V., Ed.; NOVA Science Publishers, Inc: New York, 2001; pp. 41–100. [Google Scholar]

- Miyata, S. Anion-Exchange Properties of Hydrotalcite-Like Compounds. Clays Clay Miner 1983, 31, 305–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, P.H.; de Luna, G.S.; Angelucci, S.; Canciani, A.; Jones, W.; Decarolis, D.; Ospitali, F.; Aguado, E.R.; Rodríguez-Castellón, E.; Fornasari, G.; et al. Understanding Structure-Activity Relationships in Highly Active La Promoted Ni Catalysts for CO2 Methanation. Appl Catal B 2020, 278, 119256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huheey, J.E.; Keiter, E.A.; Keiter, R.L. Inorganic Chemistry: Principles of Structure and Reactivity, 4th ed.; HarperCollins College Publishers: New York, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Wierzbicki, D.; Debek, R.; Motak, M.; Grzybek, T.; Gálvez, M.E.; Da Costa, P. Novel Ni-La-Hydrotalcite Derived Catalysts for CO2 Methanation. Catal Commun 2016, 83, 5–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daza, C.E.; Gallego, J.; Moreno, J.A.; Mondragón, F.; Moreno, S.; Molina, R. CO2 Reforming of Methane over Ni/Mg/Al/Ce Mixed Oxides. Catal Today 2008, 133–135, 357–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández, J.M.; Barriga, C.; Ulibarri, M.A.; Labajos, F.M.; Rives, V. New Hydrotalcite-like Compounds Containing Yttrium. Chemistry of Materials 1997, 9, 312–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drits, V.A.; Bookin, A.S. Crystal Structure and X-Ray Identification of Layered Double Hydroxides. In Layered Double Hydroxides: Present and Future; Rives, V., Ed.; NOVA Science Publishers, Inc: New York, 2001; pp. 41–100. [Google Scholar]

- Cavani, F.; Trifirò, F.; Vaccari, A. Hydrotalcite-Type Anionic Clays: Preparation, Properties and Applications. Catal Today 1991, 11, 173–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bookin, A.S.; Drits, V.A. Polytype Diversity of the Hydrotalcite-like Minerals I. Possible Polytypes and Their Diffraction Features. Clays Clay Miner 1993, 41, 551–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- JCPDS, F. Joint Committee on Powder Diffraction Standards; International Centre for Diffraction Data: Pennsylvania, U.S.A, 1977. [Google Scholar]

- Labajos, F.M.; Rives, V.; Ulibarri, M.A. Effect of Hydrothermal and Thermal Treatments on the Physicochemical Properties of Mg-Al Hydrotalcite-like Materials. J Mater Sci 1992, 27, 1546–1552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, X.; Li, P.; Zhang, X.; Yu, B.; Lv, C.; Zeng, N.; Luo, J.; Zhang, Z.; Song, J.; Liu, Y. Ni-Based Catalyst Derived from NiAl Layered Double Hydroxide for Vapor Phase Catalytic Exchange between Hydrogen and Water. Nanomaterials 2019, 9, 1688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kovanda, F.; Rojka, T.; Bezdička, P.; Jirátová, K.; Obalová, L.; Pacultová, K.; Bastl, Z.; Grygar, T. Effect of Hydrothermal Treatment on Properties of Ni-Al Layered Double Hydroxides and Related Mixed Oxides. J Solid State Chem 2009, 182, 27–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meza-Fuentes, E.; Rodriguez-Ruiz, J.; Rangel, M.D.C. Characteristics of NiO Present in Solids Obtained from Hydrotalcites Based on Ni/Al and Ni-Zn/Al. Dyna (Medellin) 2019, 86, 58–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakamoto, K. Infrared and Raman Spectra of Inorganic and Coordination Compounds. Part A: Theory and Applications in Inorganic Chemistry, 6th ed.; John Wiley and Sons Inc.: Hoboken, New Jersey, 2009; ISBN 9780471743392. [Google Scholar]

- Kloprogge, J.T.; Wharton, D.; Hickey, L.; Frost, R.L. Infrared and Raman Study of Interlayer Anions CO32−, NO3−, SO42− and ClO4− in Mg/Al-Hydrotalcite. American Mineralogist 2002, 87, 623–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kloprogge, J.T.; Frost, R.L. Fourier Transform Infrared and Raman Spectroscopic Study of the Local Structure of Mg-, Ni-, and Co-Hydrotalcites. J Solid State Chem 1999, 146, 506–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kooli, F.; Kosuge, K.; Tsunashima, A. Mg-Zn-Al-CO3 and Zn-Cu-Al-CO3 Hydrotalcite-like Compounds: Preparation and Characterization. J Mater Sci 1995, 30, 4591–4597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mališová, M.; Horňáček, M.; Mikulec, J.; Hudec, P.; Jorík, V. FTIR Study of Hydrotalcite. Acta Chimica Slovaca 2018, 11, 147–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benito Martín, P. Influencia de La Radiación Microondas En El Proceso de Síntesis de Compuestos Tipo Hidrotalcita y Óxidos Relacionados, Universidad de Salamanca, 2007.

- Abdolmohammad-Zadeh, H.; Kohansal, S.; Sadeghi, G.H. Nickel-Aluminum Layered Double Hydroxide as a Nanosorbent for Selective Solid-Phase Extraction and Spectrofluorometric Determination of Salicylic Acid in Pharmaceutical and Biological Samples. Talanta 2011, 84, 368–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jayakumar, G.; Irudayaraj, A.A.; Raj, A.D. Investigation on the Synthesis and Photocatalytic Activity of Activated Carbon–Cerium Oxide (AC–CeO2) Nanocomposite. Appl Phys A Mater Sci Process 2019, 125, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, P.R.; Maharajan, T.M.; Chinnasamy, M.; Prabu, A.P.; Suthagar, J.A.; Kumar, K.S. Hydroxyl Radical Scavenging Activity of La2O3 Nanoparticles. The Pharma Innovation Journal 2019, 8, 759–763. [Google Scholar]

- Patil, S.P.; Jadhav, L.D.; Dubal, D.P.; Puri, V.R. Characterization of NiO-Al2O3 Composite and Its Conductivity in Biogas for Solid Oxide Fuel Cell. Materials Science- Poland 2016, 34, 266–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, G.Bin; Chen, S.F.; Liu, L.; Jiang, J.; Yao, H.Bin; Xu, A.W.; Yu, S.H. 1,3-Diamino-2-Hydroxypropane-N,N,N′,N′-Tetraacetic Acid Stabilized Amorphous Calcium Carbonate: Nucleation, Transformation and Crystal Growth. CrystEngComm 2010, 12, 234–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Shih, K.; Gao, Y.; Li, F.; Wei, L. Dechlorinating Transformation of Propachlor through Nucleophilic Substitution by Dithionite on the Surface of Alumina. J Soils Sediments 2012, 12, 724–733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadav, S.K.; Jeevanandam, P. Synthesis of NiO-Al2O3 Nanocomposites by Sol-Gel Process and Their Use as Catalyst for the Oxidation of Styrene. J Alloys Compd 2014, 610, 567–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeevanandam, P.; Koltypin, Y.; Gedanken, A. Preparation of Nanosized Nickel Aluminate Spinel by a Sonochemical Method; 2002; Volume 90. [Google Scholar]

- Culica, M.E.; Chibac-Scutaru, A.L.; Melinte, V.; Coseri, S. Cellulose Acetate Incorporating Organically Functionalized CeO2 NPs: Efficient Materials for UV Filtering Applications. Materials 2020, 13, 2955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kabir, H.; Nandyala, S.H.; Rahman, M.M.; Kabir, M.A.; Stamboulis, A. Influence of Calcination on the Sol–Gel Synthesis of Lanthanum Oxide Nanoparticles. Appl Phys A Mater Sci Process 2018, 124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thommes, M.; Kaneko, K.; Neimark, A.V.; Olivier, J.P.; Rodriguez-Reinoso, F.; Rouquerol, J.; Sing, K.S.W. Physisorption of Gases, with Special Reference to the Evaluation of Surface Area and Pore Size Distribution (IUPAC Technical Report). Pure and Applied Chemistry 2015, 87, 1051–1069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brunauer, S.; Deming, L.S.; Deming, W.E.; Teller, E. On a Theory of the van Der Waals Adsorption of Gases. J Am Chem Soc 1940, 62, 1723–1732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrett, E.P.; Joyner, L.G.; Halenda, P.P. The Determination of Pore Volume and Area Distributions in Porous Substances. I. Computations from Nitrogen Isotherms. J Am Chem Soc 1951, 73, 373–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Sample | Ni a | X a | Al a | M2+/M3+ b | Formulae |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NiAl-DMA | 0.643 | - | 0.310 | 2.07 | [Ni0.68Al0.32(OH)2](CO3)0.16 · 0.99 H2O |

| NiCeAl-DMA | 0.625 | 0.026 | 0.247 | 2.29 | [Ni0.70Ce0.03Al0.27(OH)2](CO3)0.15 · 1.04 H2O |

| NiLaAl-DMA | 0.596 | 0.042 | 0.233 | 2.17 | [Ni0.68La0.05Al0.27(OH)2](CO3)0.16 · 1.05 H2O |

| Sample | c (Å) | (Å) | D (nm) |

|---|---|---|---|

| NiAl-DMA | 22.96 | 3.028 | 4.7 |

| NiCeAl-DMA | 23.09 | 3.037 | 3.9 |

| NiLaAl-DMA | 23.00 | 3.019 | 3.7 |

| Sample | (Å) | D (nm) |

|---|---|---|

| NiAl-DMA-C600 | 4.168 | 3.7 |

| NiCeAl-DMA-C600 | 4.178 | 3.8 |

| NiLaAl-DMA-C600 | 4.186 | 3.6 |

| Sample | SBET (m²/g) | VP (mm3/g) | BJH average desorption pore diameter (nm) |

|---|---|---|---|

| NiAl-DMA-C600 | 150 | 290 | 5.6 |

| NiCeAl-DMA-C600 | 130 | 460 | 11.3 |

| NiLaAl-DMA-C600 | 120 | 480 | 13.1 |

| Sample | Slope below | Fundamental peak | Eg (eV) |

|---|---|---|---|

| NiAl-DMA-C600 | y = - 0.10939 + 0.04658 x | y = - 1.86911 + 0.55943 x | 3.43 |

| NiCeAl-DMA-C600 | y = - 0.1369 + 0.05688 x | y = - 3.39866 + 0.98163 x | 3.53 |

| NiLaAl-DMA-C600 | y = - 0.03613 + 0.01913 x | y = - 3.29396 + 0.9276 x | 3.59 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).