Submitted:

26 July 2024

Posted:

30 July 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

1.1. Hetero-Dehumanization

1.2. Self-Dehumanization

1.3. The Current Study

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. The Questionnaires

2.3. Ethical Considerations

2.4. Analytical Plan

3. Results

3.1. Animalistic and Mechanistic Hetero-Dehumanization and Self-Dehumanization Scales

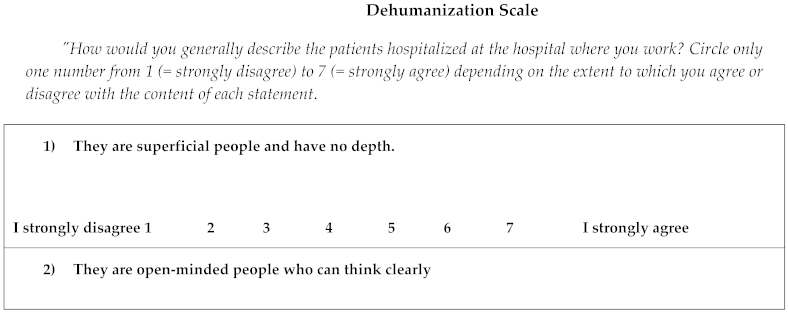

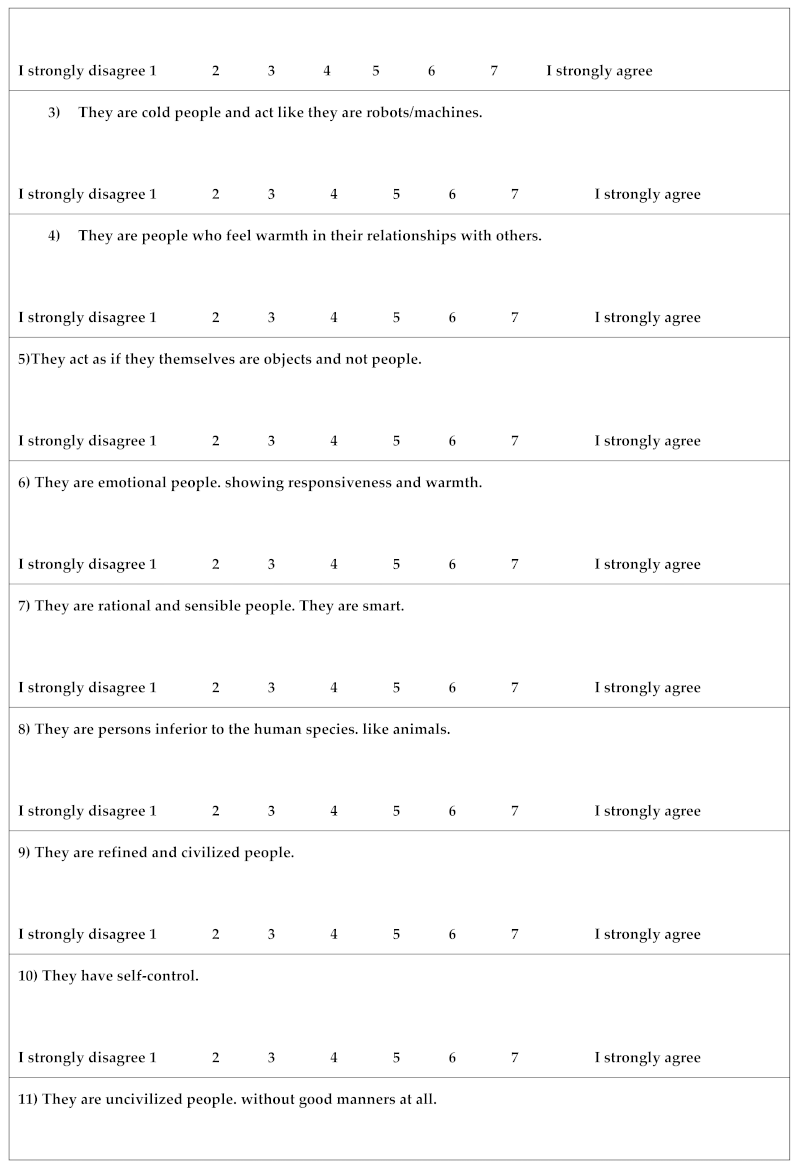

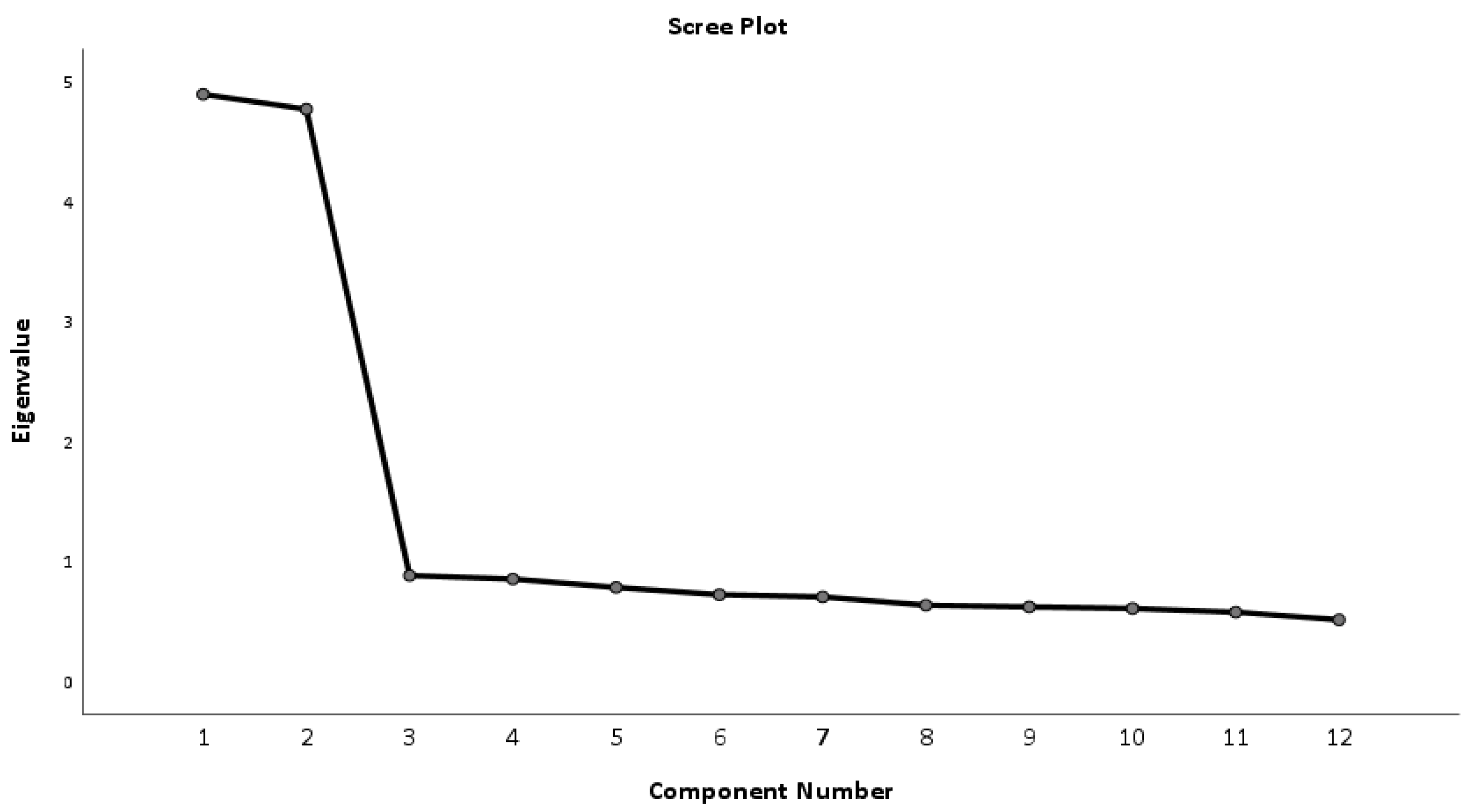

3.1.1. Animalistic and Mechanistic Hetero-Dehumanization Scale

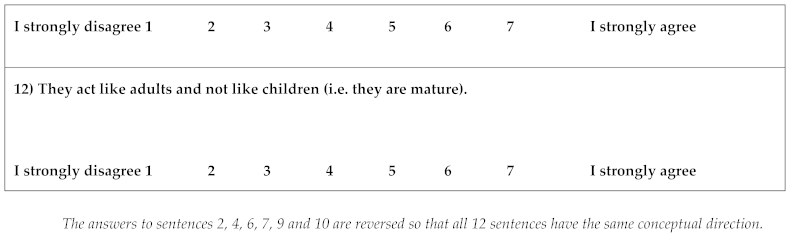

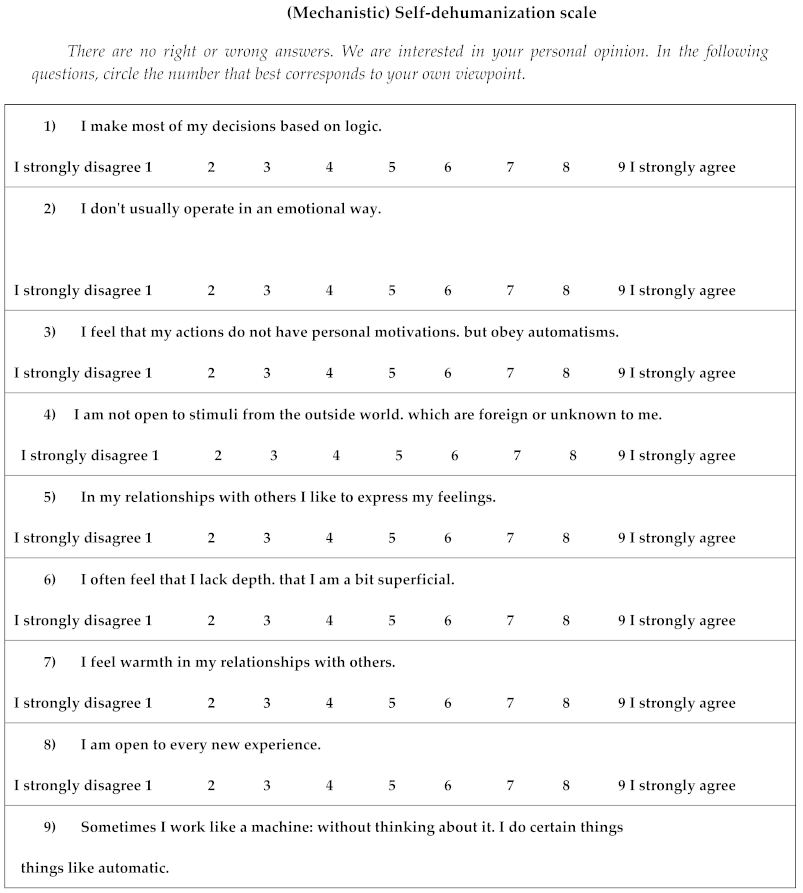

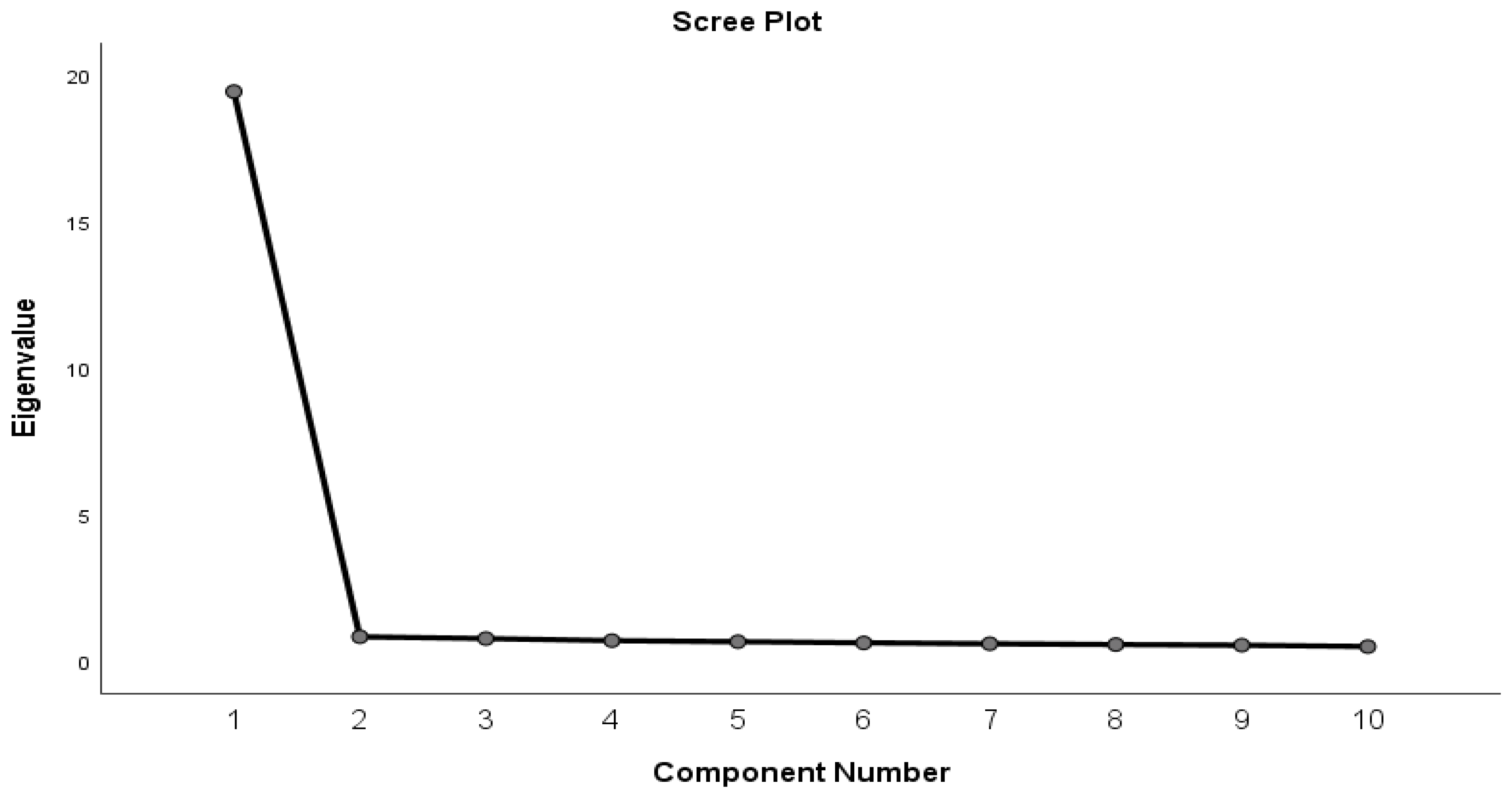

3.1.2. Mechanistic Self-Dehumanization Scale

| Raw | Rescaled | |

|---|---|---|

| Component | Component | |

| 1 | 1 | |

| SDS-1 | 1.478 | 0.882 |

| SDS-2 | 1.429 | 0.873 |

| SDS-3 | 1.045 | 0.828 |

| SDS-4 | 1.417 | 0.888 |

| SDS-5 | 1.415 | 0.873 |

| SDS-6 | 1.417 | 0.872 |

| SDS-7 | 1.410 | 0.884 |

| SDS-8 | 1.486 | 0.896 |

| SDS-9 | 1.432 | 0.884 |

| SDS-10 | 1.366 | 0.871 |

|

Extraction Method: Principal Component Analysis. SDS = Self-Dehumanization scale | ||

|

Totally Disagree |

2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | Completely Agree |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | % | N | % | N | % | N | % | N | % | N | % | N | % | |

| They are superficial people and have no depth. | 41 | 10.3 | 92 | 23.0 | 131 | 32.8 | 88 | 22.0 | 45 | 11.3 | 2 | 0.5 | 1 | 0.3 |

| They are open-minded people who can think clearly. | 49 | 12.3 | 93 | 23.3 | 130 | 32.5 | 92 | 23.0 | 34 | 8.5 | 1 | 0.3 | 1 | 0.3 |

| They are cold people and act like robots/machines. | 46 | 11.5 | 90 | 22.5 | 130 | 32.5 | 91 | 22.8 | 40 | 10.0 | 1 | 0.3 | 2 | 0.5 |

| They are people who feel warmth in their relationships with others. | 36 | 9.0 | 95 | 23.8 | 123 | 30.8 | 102 | 25.5 | 40 | 10.0 | 3 | 0.8 | 1 | 0.3 |

| They act as if they themselves are objects and not people. | 38 | 9.5 | 92 | 23.0 | 133 | 33.3 | 89 | 22.3 | 45 | 11.3 | 1 | 0.3 | 2 | 0.5 |

| They are emotional people, showing responsiveness and warmth. | 45 | 11.3 | 85 | 21.3 | 133 | 33.3 | 94 | 23.5 | 40 | 10.0 | 3 | 0.8 | 0 | 0.0 |

|

They are rational and sensible people. They are smart. |

2 | 0.5 | 1 | 0.3 | 42 | 10.5 | 89 | 22.3 | 130 | 32.5 | 88 | 22.0 | 48 | 12.0 |

|

They are people inferior to the human species, like animals. |

1 | 0.3 | 2 | 0.5 | 40 | 10.0 | 81 | 20.3 | 152 | 38.0 | 76 | 19.0 | 48 | 12.0 |

|

They are refined and civilized people. |

1 | 0.3 | 1 | 0.3 | 44 | 11.0 | 80 | 20.0 | 150 | 37.5 | 89 | 22.3 | 35 | 8.8 |

|

They have self-control. |

1 | 0.3 | 2 | 0.5 | 48 | 12.0 | 62 | 15.5 | 151 | 37.8 | 87 | 21.8 | 49 | 12.3 |

| They are uncivilized people, without good manners at all. | 1 | 0.3 | 2 | 0.5 | 46 | 11.5 | 88 | 22.0 | 144 | 36.0 | 81 | 20.3 | 38 | 9.5 |

| They act like adults and not like children (i.e. they are mature). | 2 | 0.5 | 1 | 0.3 | 47 | 11.8 | 86 | 21.5 | 128 | 32.0 | 96 | 24.0 | 40 | 10.0 |

|

Totally Disagree |

2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 |

Totally Disagree |

||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | % | N | % | N | % | N | % | N | % | N | % | N | % | N | % | N | % | |

| I make most of my decisions based on logic. | 24 | 6.0 | 18 | 4.5 | 11 | 2.8 | 111 | 27.8 | 98 | 24.5 | 104 | 26.0 | 12 | 3.0 | 10 | 2.5 | 12 | 3.0 |

| I don't usually operate in an emotional way. | 18 | 4.5 | 19 | 4.8 | 16 | 4.0 | 107 | 26.8 | 98 | 24.5 | 108 | 27.0 | 13 | 3.3 | 7 | 1.8 | 14 | 3.5 |

| I feel that my actions are not based personal motives, but are due to automatisms. | 7 | 1.8 | 12 | 3.0 | 34 | 8.5 | 118 | 29.5 | 134 | 33.5 | 61 | 15.3 | 34 | 8.5 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 |

| I am not open to stimuli from the outside world, which are alien or unknown to me. | 17 | 4.3 | 19 | 4.8 | 17 | 4.3 | 93 | 23.3 | 128 | 32.0 | 92 | 23.0 | 14 | 3.5 | 7 | 1.8 | 13 | 3.3 |

| In my relationships with others, I like to express my feelings. | 21 | 5.3 | 18 | 4.5 | 14 | 3.5 | 94 | 23.5 | 108 | 27.0 | 111 | 27.8 | 16 | 4.0 | 8 | 2.0 | 10 | 2.5 |

| I often feel that I lack depth, that I am a bit superficial. | 17 | 4.3 | 17 | 4.3 | 19 | 4.8 | 122 | 30.5 | 91 | 22.8 | 100 | 25.0 | 12 | 3.0 | 8 | 2.0 | 14 | 3.5 |

| I feel warmth in my relationships with others. | 16 | 4.0 | 19 | 4.8 | 18 | 4.5 | 104 | 26.0 | 111 | 27.8 | 98 | 24.5 | 12 | 3.0 | 11 | 2.8 | 11 | 2.8 |

| I am open to every new experience. | 21 | 5.3 | 22 | 5.5 | 10 | 2.5 | 107 | 26.8 | 103 | 25.8 | 103 | 25.8 | 10 | 2.5 | 14 | 3.5 | 10 | 2.5 |

| Sometimes I work like a machine: without thinking about it, I do certain things like an automaton. | 18 | 4.5 | 17 | 4.3 | 18 | 4.5 | 98 | 24.5 | 104 | 26.0 | 111 | 27.8 | 11 | 2.8 | 12 | 3.0 | 11 | 2.8 |

| I believe that most of my actions and choices in life come frommy own autonomous intentions and preferences. | 18 | 4.5 | 13 | 3.3 | 22 | 5.5 | 104 | 26.0 | 106 | 26.5 | 103 | 25.8 | 13 | 3.3 | 14 | 3.5 | 7 | 1.8 |

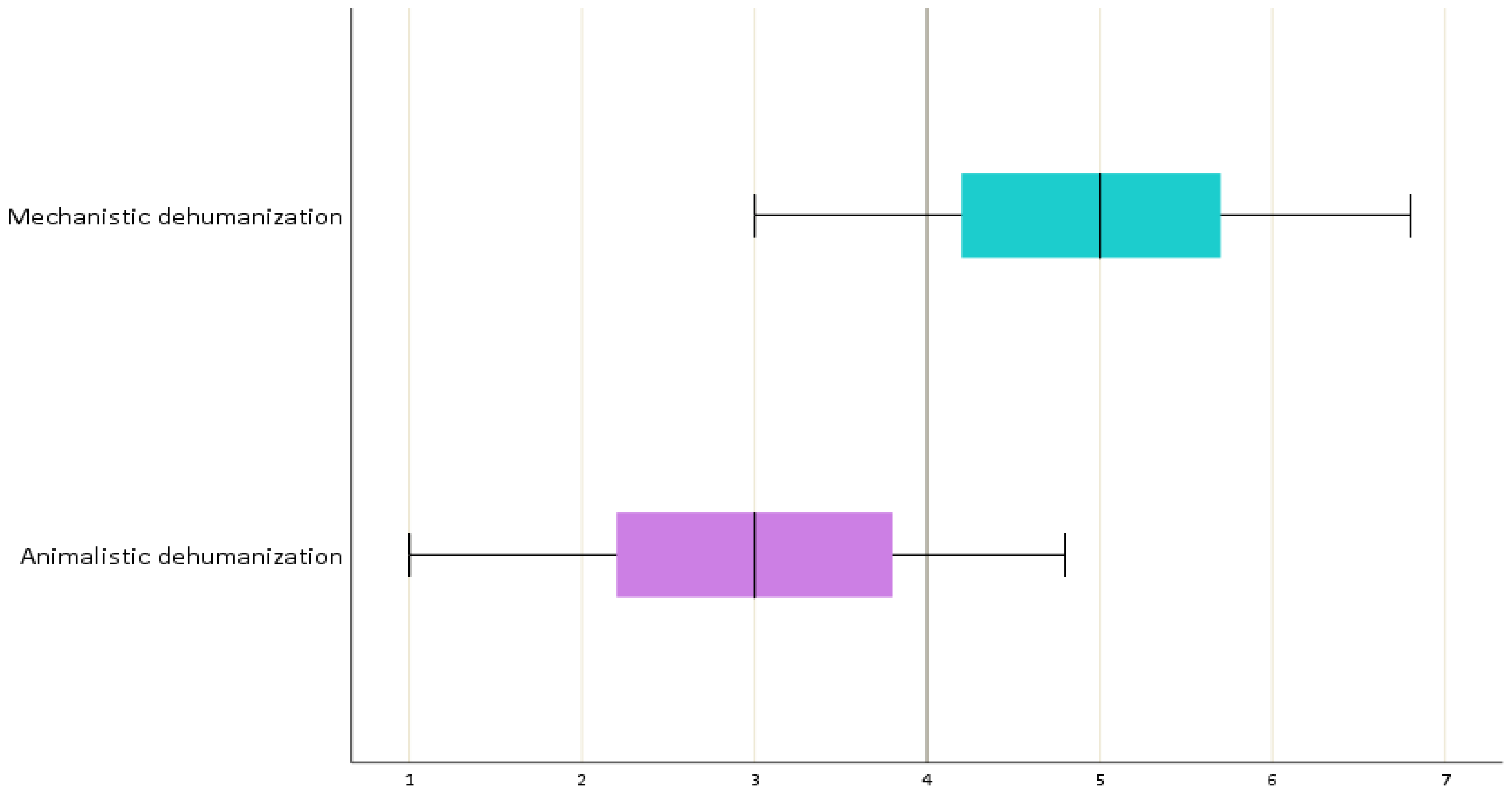

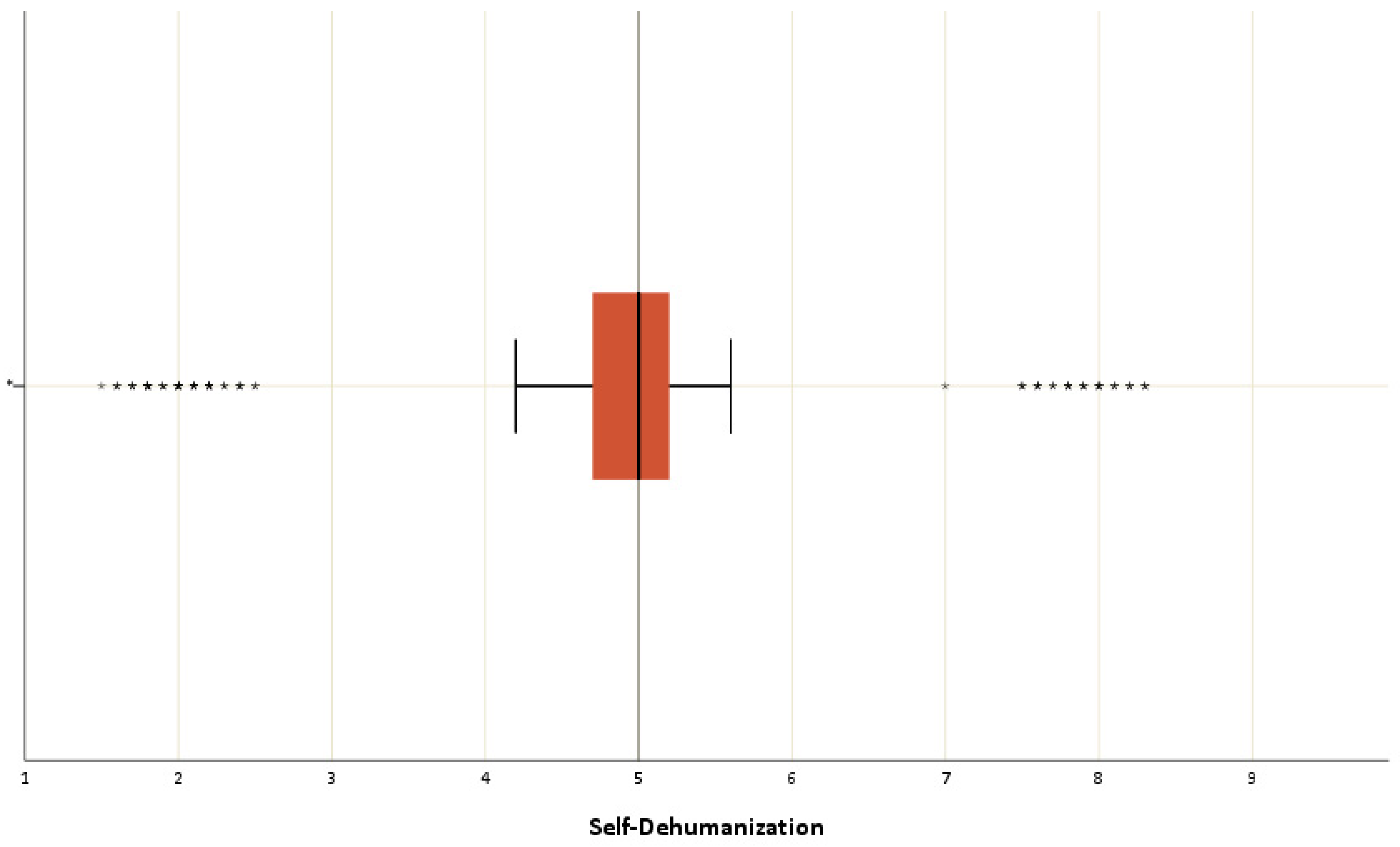

3.1.3. Means score of the Dehumanization and Self-dehumanization

4. Discussion

4.1. Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

Appendix B

References

- M. Sakalaki, C. Richardson, and K. Fousiani, "Is suffering less human? Distressing situations’ effects on dehumanizing the self and others," Hellenic Journal of Psychology, vol. 14, no. 1, pp. 39–63, 2017.

- N. Haslam, "Dehumanization: an integrative review," Pers Soc Psychol Rev, vol. 10, no. 3, pp. 252–264, 2006. [CrossRef]

- N. Haslam, S. Loughnan, C. Reynolds, and S. Wilson, "Dehumanization: A new perspective," Social and Personality Psychology Compass, vol. 1, no. 1, pp. 409–422, 2007.

- N. Haslam and P. Bain, "Humanizing the self: Moderators of the attribution of lesser humanness to others," Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, vol. 33, no. 1, pp. 57–68, 2007.

- D. L. Smith, On inhumanity: Dehumanization and how to resist it. Oxford University Press, 2020. https://books.google.com/books?hl=el&lr=&id=hXXnDwAAQBAJ&oi=fnd&pg=PP1&dq=D.+L.+Smith,+On+inhumanity:+Dehumanization+and+how+to+resist+it.+Oxford+University+Press,+2020.&ots=ohu3AoLH4k&sig=FExFByXVX-NNNaUHSeZ1d0Zr4Wo.

- H. M. Gray, K. Gray, and D. M. Wegner, "Dimensions of mind perception," science, vol. 315, no. 5812, pp. 619–619, 2007.

- K. Gray, J. Knobe, M. Sheskin, P. Bloom, and L. F. Barrett, "More than a body: mind perception and the nature of objectification.," Journal of personality and social psychology, vol. 101, no. 6, p. 1207, 2011.

- K. Gray, L. Young, and A. Waytz, "Mind Perception Is the Essence of Morality," Psychological Inquiry, vol. 23, no. 2, pp. 101–124, April 2012. [CrossRef]

- E. Trifiletti, G. A. Di Bernardo, R. Falvo, and D. Capozza, "Patients are not fully human: A nurse’s coping response to stress," Journal of Applied Social Psychology, vol. 44, no. 12, pp. 768–777, 2014.

- C. J. Hoogendoorn and N. D. Rodríguez, "Rethinking dehumanization, empathy, and burnout in healthcare contexts," Current Opinion in Behavioral Sciences, vol. 52, pp. 101285, 2023.

- M. S. Lebowitz and W. Ahn, "Effects of biological explanations for mental disorders on clinicians’ empathy," Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, vol. 111, no. 50, December 2014. [CrossRef]

- O. S. Haque and A. Waytz, "Dehumanization in medicine: Causes, solutions, and functions," Perspectives on psychological science, vol. 7, no. 2, pp. 176–186, 2012.

- J. M. Twenge, R. F. Baumeister, C. N. DeWall, N. J. Ciarocco, and J. M. Bartels, "Social exclusion decreases prosocial behavior.," Journal of personality and social psychology, vol. 92, no. 1, 2007.

- E. Elder, A. N. B. Johnston, M. Wallis, and J. Crilly, "The demoralisation of nurses and medical doctors working in the emergency department: A qualitative descriptive study," International Emergency Nursing, vol. 52, pp. 100841, September 2020. [CrossRef]

- C. Moller and E. L. Deci, "Interpersonal control, dehumanization, and violence: A self-determination theory perspective," Group Processes & Intergroup Relations, vol. 13, no. 1, pp. 41–53, January 2010. [CrossRef]

- M. Sakalaki, C. Richardson, and K. Fousiani, "Self-dehumanizing as an effect of enduring dispositions poor in humanness," Hellenic Journal of Psychology, vol. 13, no. 2, pp. 104–115, 2016.

- J. Molina-Praena, L. Ramirez-Baena, J. L. Gómez-Urquiza, G. R. Cañadas, E. I. De la Fuente, and G. A. Cañadas-De la Fuente, "Levels of Burnout and Risk Factors in Medical Area Nurses: A Meta-Analytic Study," International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, vol. 15, no. 12, December 2018. [CrossRef]

- E. Diniz, P. Castro, A. Bousfield, and S. Figueira Bernardes, "Classism and dehumanization in chronic pain: A qualitative study of nurses’ inferences about women of different socio-economic status," British Journal of Health Psychology, vol. 25, no. 1, 2020. [CrossRef]

- T. A. Eikemo et al., "Health in crises. Migration, austerity and inequalities in Greece and Europe: introduction to the supplement," Eur J Public Health, vol. 28, no. Suppl 5, pp. 1–4, December 2018. [CrossRef]

- S. Fontesse, X. Rimez, and P. Maurage, "Stigmatization and dehumanization perceptions towards psychiatric patients among nurses: A path-analysis approach," Archives of psychiatric nursing, vol. 35, no. 2, pp. 153–161, 2021.

- C. R. Cloninger, D. Stoyanov, K. K. Stoyanova, and K. K. Stutzman, "Empowerment of Health Professionals," in Person Centered Medicine, J. E. Mezzich, W. J. Appleyard, P. Glare, J. Snaedal, and C. R. Wilson Eds.,Eds., Cham: Springer International Publishing, 2023, pp. 703–723. [CrossRef]

- T. P. Reith, "Burnout in United States healthcare professionals: a narrative review," Cureus, vol. 10, no. 12, 2018.

- I. Batanda, "Prevalence of burnout among healthcare professionals: a survey at fort portal regional referral hospital," npj Mental Health Res, 6;3(1):16 2024. [CrossRef]

- G. MILAURO, "The role of outgroup dehumanization in healthcare disparities: A study with medical students," June 2024, https://thesis.unipd.it/handle/20.500.12608/31615.

- A. M. Ruiz, K. M. Moore, L. M. Woehrle, P. Kako, K. C. Davis, and L. Mkandawire-Valhmu, "Experiences of dehumanizing: Examining secondary victimization within the nurse-patient relationship among African American women survivors of sexual assault in the Upper Midwest," Social Science & Medicine, vol. 329, pp. 116029, 2023.

- M. J. Basile et al., "Humanizing the ICU patient: a qualitative exploration of behaviors experienced by patients, caregivers, and ICU staff," Critical care explorations, vol. 3, no. 6, 2021.

- N. Haslam and S. Loughnan, "Dehumanization and infrahumanization," Annual review of psychology, vol. 65, pp. 399–423, 2014.

- G. A. Boysen, R. L. Chicosky, and E. E. Delmore, "Dehumanization of mental illness and the stereotype content model.,"Stigma and Health, vol. 8, no. 2, 2023.

- D. Lekka et al.,"Dehumanization of Hospitalized Patients and Self-Dehumanization by Health Professionals and the General Population in Greece.," Cureus, vol. 13, no. 12, pp. e20182, December 2021. [CrossRef]

- M. Svoli, M. Sakalaki, and C. Richardson, "Dehumanization of the mentally ill compared to healthy targets," Hellenic Journal of Psychology, vol. 15, no. 3, 2018.

- E. P. Sands and L. T. Harris, "Culture and Dehumanization: A Case Study of the Doctor–Patient Paradigm and Implications for Global Health," στο Oxford Handbook of Cultural Neuroscience and Global Mental Health, 2021.

- K. Fousiani, M. Michaelides, and P. Dimitropoulou, "The effects of ethnic group membership on bullying at school: when do observers dehumanize bullies?," The Journal of Social Psychology, vol. 159, no. 4, pp. 431–442, July 2019. [CrossRef]

- K. Fousiani, P. Dimitropoulou, M. P. Michaelides, and S. Van Petegem, "Perceived Parenting and Adolescent Cyber-Bullying: Examining the Intervening Role of Autonomy and Relatedness Need Satisfaction, Empathic Concern and Recognition of Humanness," J Child Fam Stud, vol. 25, no. 7, pp. 2120–2129, July 2016. [CrossRef]

- B. Bastian and N. Haslam, "Excluded from humanity: The dehumanizing effects of social ostracism," Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, vol. 46, no. 1, pp. 107–113, Jan. 2010. [CrossRef]

- D. F. Polit and C. T. Beck, "The content validity index: are you sure you know what’s being reported? Critique and recommendations," Research in nursing & health, vol. 29, no. 5, 2006.

- F. Gravetter and L. Forzano, "Research methods for the behavioral sciences (Gravetter)," Belmont: Cengage Learning, 2010.

- N. Haslam and M. Stratemeyer, "Recent research on dehumanization," Current Opinion in Psychology, vol. 11, p. 25–29, 2016.

- J. Leyens, S. Demoulin, J. A. F. Vaes, R. Gaunt, and M. P. Paladino, "Infra-humanization: the wall of group diffrences," Social Issues and Policy Review, vol. 1, pp. 173–216, 2007.

- J. Vaes, J.-P. Leyens, M. Paola Paladino, and M. Pires Miranda, "We are human, they are not: Driving forces behind outgroup dehumanisation and the humanisation of the ingroup," European review of social psychology, vol. 23, no. 1, pp. 64–106, 2012.

- S. M. Adams, T. I. Case, J. Fitness, και R. J. Stevenson, "Dehumanizing but competent: the impact of gender, illness type, and emotional expressiveness on patient perceptions of doctors," Journal of Applied Social Psychology, vol. 47, no. 5, pp. 247–255, 2017.

- N. Katz, J. Jones, L. Mansfield, and M. Gold, "The Impact of Health Professionals’ Language on Patient Experience: A Case Study," Journal of Patient Experience, vol. 9, pp. 237437352210925, April 2022. [CrossRef]

- A. Bandura, "Moral disengagement in the perpetration of inhumanities," Personality and social psychology review, vol. 3, no. 3, pp. 193–209, 1999.

- C. Maddock, "The dehumanization of the American healthcare professional: The Impact of technology on the ever-evolving world of medicine," 2019.

- M. Grissinger, "Disrespectful Behavior in Health Care," P T, vol. 42, no. 2, February 2017.

- C. A. Shaw και J. K. Gordon, "Understanding Elderspeak: An Evolutionary Concept Analysis," Innov Aging, vol. 5, no. 3, July 2021. [CrossRef]

- D. Capozza, "Dehumanization in medical contexts: An expanding research field," TPM, vol. 1, no. 1, 2016. [CrossRef]

- J. L. Bastos, R. P. Duquia, D. A. González-Chica, J. M. Mesa, and R. R. Bonamigo, "Field work I: selecting the instrument for data collection," An Bras Dermatol, vol. 89, no. 6, pp. 918–923, 2014. [CrossRef]

- B. Bastian and C. Crimston, "Self-dehumanization," TPM - Testing, vol. 21, pp. 241–250, September 2014. [CrossRef]

- M. Tavakol and A. Wetzel, "Factor Analysis: a means for theory and instrument development in support of construct validity," Int J Med Educ, vol. 11, pp. 245–247, November 2020. [CrossRef]

- M. Heo, N. Kim, and M. S. Faith, "Statistical power as a function of Cronbach alpha of instrument questionnaire items," BMC Med Res Methodol, vol. 15, pp. 86, October 2015. [CrossRef]

- W. Yang, S. Jin, S. He, Q. Fan, and Y. Zhu, "The impact of power on humanity: self-dehumanization in powerlessness," PLoS One, vol. 10, no. 5, pp. e0125721, 2015. [CrossRef]

| Mean (SD) | |||

| Age | 43.8 ± 10.5 | ||

| Working experience | 9.2 ± 8.8 | ||

| N | % | ||

| Biological sex | Male | 103 | 25.7% |

| Female | 297 | 74.3% | |

| Place of residence | Village | 55 | 13.8% |

| City<150,000 inhabitants | 127 | 31.8% | |

| City>150,000 inhabitants | 218 | 54.5% | |

| Marital status | Unmarried | 131 | 32.8% |

| Married | 237 | 59.3% | |

| Divorced | 29 | 7.3% | |

| Widower | 3 | 0.8% | |

| Profession | Nursing | 294 | 73.5% |

| Medicine | 106 | 26.5% | |

| Annual income | ≤20.000 € | 343 | 85.8% |

| >20.000 € | 57 | 14.3% | |

| Post-graduate degrees | MSc | 66 | 81.5% |

| PhD | 15 | 18.5% | |

| Labour Department | Ward | 195 | 48.7% |

| Unit | 205 | 51.3% | |

| Working hours | Circular timetable | 298 | 74.5% |

| Morning/afternoon schedule | 102 | 25.5% | |

| Have you attended any psychotherapy sessions? | Yes | 66 | 16.5% |

| No | 334 | 83.5% | |

| Raw | Rescaled | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Component | Component | ||||

| 1 | 2 | 1 | 2 | ||

| DS-1 | 0.894 | 0.757 | |||

| DS-2 | 0.872 | 0.749 | |||

| DS-3 | 0.923 | 0.775 | |||

| DS-4 | 0.902 | 0.774 | |||

| DS-5 | 0.876 | 0.744 | |||

| DS-6 | 0.896 | 0.766 | |||

| DS-7 | 0.942 | 0.782 | |||

| DS-8 | 0.837 | 0.717 | |||

| DS-9 | 0.842 | 0.745 | |||

| DS-10 | 0.944 | 0.789 | |||

| DS-11 | 0.906 | 0.781 | |||

| DS-12 | 0.918 | 0.768 | |||

|

Extraction Method: Principal Component Analysis. Rotation Method: Varimax with Kaiser Normalization. |

|||||

| Age | Biological sex |

Place of residence* | Marital status | Profession | Annual income | Postgraduate degrees | Labour Department | Years of work in this department | Working hours | Have you attended any psychotherapy sessions? | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Mechanistic dehumanization |

Correlation | -0.060 | -0.013 | -0.001 | 0.019 | -0.055 | 0.017 | 0.102 | -0.072 | 0.031 | -0.001 | -0.007 |

| Sig. (2-tailed) | 0.230 | 0.802 | 0.981 | 0.699 | 0.275 | 0.729 | 0.363 | 0.149 | 0.538 | 0.986 | 0.888 | |

| N | 400 | 400 | 400 | 400 | 400 | 400 | 81 | 400 | 400 | 400 | 400 | |

| Animalistic dehumanization | Correlation | -0.075 | -0.016 | -0.019 | 0.015 | -0.050 | 0.024 | 0.097 | -0.067 | 0.008 | 0.013 | -0.017 |

| Sig. (2-tailed) | 0.132 | 0.755 | 0.699 | 0.765 | 0.316 | 0.637 | 0.390 | 0.184 | 0.880 | 0.795 | 0.739 | |

| N | 400 | 400 | 400 | 400 | 400 | 400 | 81 | 400 | 400 | 400 | 400 | |

| Self-Dehumanization | Correlation | 0.035 | 0.087 | 0.061 | -0.011 | -0.078 | -0.013 | -0.127 | 0.023 | 0.131 | -0.060 | 0.108 |

| Sig. (2-tailed) | 0.483 | 0.081 | 0.225 | 0.822 | 0.120 | 0.789 | 0.259 | 0.653 | 0.009 | 0.230 | 0.031 | |

| N | 400 | 400 | 400 | 400 | 400 | 400 | 81 | 400 | 400 | 400 | 400 | |

| Sum of Squares | df | Mean Square | F | Sig. | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mechanistic dehumanization | BetweenGroups | 0.944 | 3 | 0.315 | 0.387 | 0.762 |

| WithinGroups | 321.487 | 396 | 0.812 | |||

| Total | 322.431 | 399 | ||||

| Animalistic dehumanization | BetweenGroups | 6.041 | 3 | 2.014 | 2.556 | 0.055 |

| WithinGroups | 312.016 | 396 | 0.788 | |||

| Total | 318.057 | 399 | ||||

| Mechanistic self-dehumanization | BetweenGroups | 5.985 | 3 | 1.995 | 1.034 | 0.378 |

| WithinGroups | 764.335 | 396 | 1.930 | |||

| Total | 770.320 | 399 | ||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).