Submitted:

28 July 2024

Posted:

30 July 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

- 1)

- What challenges face cultural heritage in this period of paradigm shifts that are dictating a "back to the village" trend?

- 2)

- What contrasting features appear in Transylvania in the case of urban to rural migration of population, first to a locality with an old Saxon tradition and then to a locality with a majority Romanian population?

2. Theoretical Framework: Globalization, Rural Depopulation and Urban-Rural Migration

3. Materials and Methods

4. Study Area

5. Results

5.1. The Importance of Newcomers and the Role of NGOs

5.2. Small Entrepreneurs and Tourism

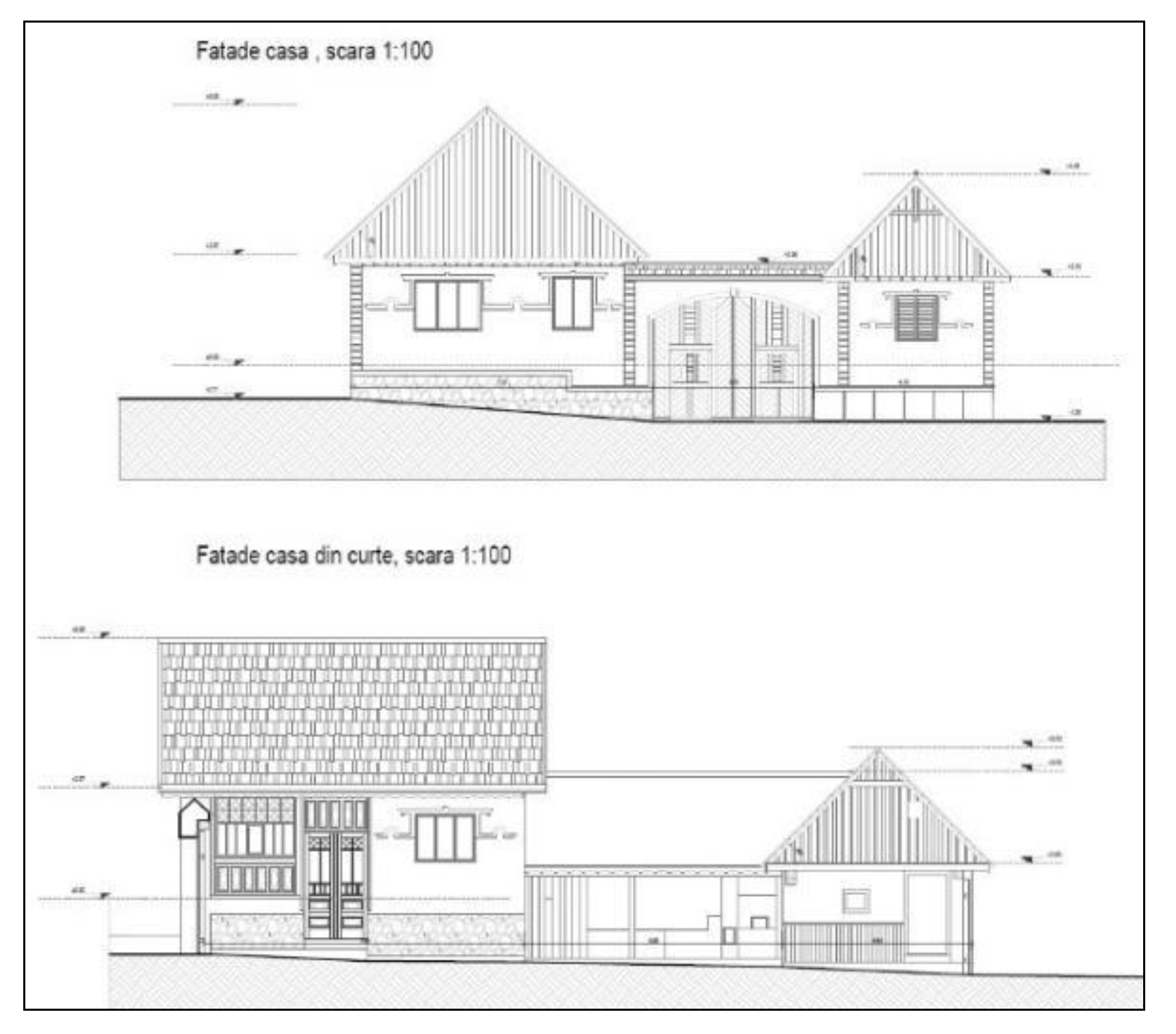

5.3. Influences on Built Heritage

"I’d like a new house, a traditional house... I don’t know what you mean. [...] I liked our old house, but it’s harder though. I’ll tell you, those windows were harder to wash. [...] Now I wouldn’t build a traditional house, if I were to build a house, I think half the walls would be glass. [...] These traditional houses really have small, narrow windows. They’re cool like that, but I don’t know... [...] Now in this century of speed, what can you do with a traditional house?"

"I love history, and I think it’s worth saving for us and for future generations; if we do it together we might attract visitors who like this kind of village." (D, 54, newcomer) Others even feel that "if I can create objects that go with the houses and the architecture of the buildings, that’s what I enjoy doing the most. You have to combine simple things with modern design, but not everyone does that well.".(F, 36, investor)

6. Discussion and Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Argent, N. Trouble in Paradise? Governing Australia’s Multifunctional Rural Landscapes. Australian Geographer, 2011, 42 (2): 183–205. [CrossRef]

- Rizzo, A. Declining, transition and slow rural territories in Southern Italy characterizing the intra-rural divides. European Planning Studies. 2016, 24(2): 231–253. [CrossRef]

- Beel, D.E.; Wallace, C.D.; Webster, G.; Nguyen, H.; Tait, E.; Macleod, M.; Mellish, C. Cultural resilience: rural community heritage production, digital archives and the role of volunteers, Journal of Rural Studies, 2017, 54, 459-468. [CrossRef]

- Mladenov, C.; Ilieva, M. The depopulation of Bulgarian villages. In Bulletin of Geography. Socio-Economic Series (Szymańska D, Ilieva M), 17 (pp 99–107), 2012, Toruń: Nicolaus Copernicus University Press. [CrossRef]

- Rîşteiu, T.N.; Creţan, R.; O’Brien, T. Contesting post-communist development: gold extraction, local community, and rural decline. Eurasian Geography and Economics, 2022, 63(4): 491-513. [CrossRef]

- Anghel, R.; Horvath, I. Sociologia Migratiei. Teorii si Studii de Caz Romanesti [Sociology of Migration. Theories and Romanian Case Studies], Polirom, Iasi, 2009, 312 p.

- Woods, M. Engaging the global countryside: Globalization, hybridity and the reconstitution of rural place. Progress in Human Geography, 2007, 31(4): 485-507. [CrossRef]

- Van der Ploeg, J.D. The new peasantries: struggles for autonomy and sustainability in an era of empire and globalization, Earthscan Publications Ltd, 2009, 386 p.

- Harvey, D. A Brief History of Neoliberalism, Oxford University Press, 2007, 254 p.

- Dragan, A.; Crețan, R.; Lungu, M.A. Neglected and Peripheral Spaces: Challenges of Socioeconomic Marginalization in a South Carpathian Area. Land 2024, 13, 1086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Brien, T. Shifting views of environmental NGOs in Spain and Romania. Southeast European and Black Sea Studies, 2009, 9 (1): 143–160. [CrossRef]

- Dragan, A.; Popa, N. Social Economy in Post-communist Romania: What Kind of Volunteering for What Type of NGOs? Journal of Balkan and Near Eastern Studies Volume, 2017, 19(3), 330-350. [CrossRef]

- Glemain, P.; Bioteau, E.; Dragan, A. Les finances solidaires et l’économie sociale en roumanie: une réponse de «proximités» à la régionalisation d’une économie en transition? Annals of Public and Cooperative Economics, 2013, 84(2), 195-217. [CrossRef]

- Drury, P.; McPherson, A. Conservation principles: policies and guidance for the sustainable management of the historic environment, 2008, English Heritage,1 Waterhouse Square, 138-142 Holborn, London 77 p.

- Wang, N. Rethinking authenticity in the tourism experience. Annals of Tourism Research. 1999, 26(2) : 349-370. [CrossRef]

- Khanom, S.; Moyle, B.; Scott, N.; Kennelly, M. Host-guest authentication of intangible cultural heritage: A literature review and conceptual model. Journal of Heritage Tourism, 2019, 14(5-6):396-408.

- Iorio, M.; Corsale, A. Rural tourism and livelihood strategies in Romania. Journal of Rural Studies, 2010, 26(2):152–162. [CrossRef]

- Opincariu, D.; Voinea, A. Cultural Identity in Saxon Rural Space of Transylvania, Acta Technica Napocensis: Civil Engineering & Architecture, 2015, 58, No. 4.

- Smith, N.Toward a Theory of Gentrification A Back to the City Movement by Capital, not People, Journal of the American Planning Association, 1979, 45:4, 538-548. [CrossRef]

- Sheppard, D.; Pemberton, S. The actions of key agents in facilitating rural super-gentrification: Evidence from the English countryside, Journal of Rural Studies, 2023, 97, 485-494.

- Darling, E. The City in the Country: Wilderness Gentrification and the Rent Gap. Environment and Planning A: Economy and Space. 2005, 37(6), 1015-1032. [CrossRef]

- Bryman, A. Social Research Methods (5th Edition). Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2016.

- INSSE, National Statistical Institute of Romania, Bucharest, available at www.statistici.insse.ro, accesed on 15 April 2024.

- https://www.turnulsfatului.ro/ accesed on 28 May 2024.

- Smith, P.; Phillips. D.A. Socio-cultural representations of greentrified Pennine rurality, Journal of Rural Studies, 2001, 17(4) 457-469. [CrossRef]

- Smith, D.P. Rural gatekeepers and ‘greentrified’ pennine rurality: Opening and closing the access gates?, Social and Cultural Geography, 2002, 3(4), 447-463. [CrossRef]

- Flippen, C.; Farrell-Bryan, D. New destinations and the changing geography of immigrant incorporation. Annual Review of Sociology 2021, 47(1): 1-23. [CrossRef]

- Flippen, C. A. The More Things Change the More They Stay the Same: The Future of Residential Segregation in America. City & Community. 2016, 15(1), 14-17. [CrossRef]

- Hofmann, E. T. Does Gender Ideology Matter in Migration? Evidence from the Republic of Georgia. International Journal of Sociology, 2014, 44(3), 23–41. [CrossRef]

- Sibiu100.ro (2023), Hosman celebrating 700 years of documentary attestation (in Romanian), available at https://sibiu100.ro/cultura/locuitorii-din-hosman-sarbatoresc-700-de-ani-de-la-prima-atestare-documentara-a-satului-natal/, accessed 02 July 2024.

- Creţan, R.; Doiciar, C. Postmemory sits in places: the relationship of young Romanians to the communist past. Eurasian Geography and Economics, 2023, 64(6): 679-704. [CrossRef]

- Light, D.; Creţan, R.; Dunca, A. Education and post-communist transitional justice: Negociating the communist past in a memorial museum, Southeast European and Black Sea Studies, 2019, 19(4):565-584. [CrossRef]

- OAR (Order of Architects of Romania) (2016) Bucovina - a cultural landscape in transformation. Suceava.

- Li, Y. Heritage Tourism: The Contradictions between Conservation and Change. Tourism and Hospitality Research, 2003, 4(3), 247-261. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Fyall, A.; Zheng, Y. Heritage and tourism conflict within world heritage sites in China: a longitudinal study. Current Issues in Tourism, 2014, 18(2), 110–136. [CrossRef]

- Ianoș, I.; Văidianu, N.; Tălângă, C. Urban and Rural Geography. 2005, Ed. Universitară, Bucharest.

- Carmo, do R.M. Albernoa revisited: Tracking social capital in a Portuguese village. Sociologia Ruralis, 2010, 50 (1): 15–30. [CrossRef]

- Corpus, A.; Kahila, P.; Dax, T.; Kovács, K.; Tagai, G.; Weber, R.; Grunfelder, J.; Meredith, D.; Ortega-Reig, M.; Piras, S.; Löfving, L.; Moodie, J.; Fritsch, M.; Ferrandis, A. European shrinking rural areas: key messages for a refreshed long-term European policy vision. TERRA: Revista de Desarrollo Local, 2021, (8) , 280-309. [CrossRef]

- Săgeată, R.; Mitrică, B.; Cercleux, A.-L.; Grigorescu, I.; Hardi, T. Deindustrialization, Tertiarization and Suburbanization in Central and Eastern Europe. Lessons Learned from Bucharest City, Romania. Land 2023, 12, 1731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colavitti, A. M. , Ilovan, O. R., Mutică, P., & Serra, S. (2021). Rural areas as actors in the project of regional systems: A comparison between Sardinia and the North-West Development Region of Romania. Contesti. Città, territori, progetti, , 2(2), 209-234.

- Muntele, I.; Istrate, M.; Horea-Șerban, R.I.; Bănică, A. Demographic resilience in the rural area of Romania. A Statistical-Territorial Approach of the Last Hundred Years. Sustainability, 2021, 13(19), 10902. [CrossRef]

- Brown, D.; Argent, N. The impacts of population change on rural society and economy. In Shucksmith, M., Brown, D. (eds.) The Routledge International Handbook of Rural Studies, 2016, (128–140). Abingdon: Routledge.

- Moldovan, I.M.; Moldovan, S.V.; Ilieș, N.M. Housing degradation in the Romanian countryside - the effect of land restitution and unemployment rate. Agriculture and Agricultural Sciences Procedia, 2016, 10: 10438-443.

- Carneiro, M. J.; Lima, J.; Silva, A. L. Landscape and the rural tourism experience: identifying key elements, addressing potential, and implications for the future. In Rural Tourism, 2018, 85-103. Routledge.

- Bell, S.; Montarzino, A.; Aspinall, P.; Penēze, Z.; Nikodemus, O. Rural society, social inclusion and landscape change in Central and Eastern Europe: A case study of Latvia. Sociologia Ruralis, 2009, 49 (3): 295–326, 2009. [CrossRef]

- Lu, L.; Chi, C.; Liu, Y. Authenticity, involvement, and image: Evaluating tourist experiences at historic districts, Tourism Management, 2015, 50, 85-96.

- Sharpley, R. Tourism, sustainable development and the theoretical divide: 20 years on. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 2020, 28(1), 1932–1946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brundtland, G.H. Our Common Future: Report of the World Commission on Environment and Development. 1987, Geneva, UN-Dokument A/42/427.

- Glorius, B.; Bürer, M.; Schneider, H. Refugee integration in rural areas and the role of the receiving society. Erdkunde, 2021, 75(1): 51-60. [CrossRef]

- Maxim, C.; Chasovski, C.E. Cultural landscape change in the built environment at World Heritage Sites: Lessons from Bucovina, Romania. Journal of Derstination Marketing& Management , 2021, 20, 100583. [CrossRef]

- Gocer, O.; Shrestha, P.; Boyacioglu, D.; Gocer, K.; Karahan, E. Rural gentrification of the ancient city of Assos (Behramkale) in Turkey. Journal of Rural Studies, 2021, 87:146-159. [CrossRef]

- Kojola, E.; McMillan Lequieu, A. Performing transparency, embracing regulations: Corporate framing to mitigate environmental conflicts. Environmental Sociology. 2020, 6(4): 364–374. [CrossRef]

- Roche, M.; Argent, N. The fall and rise of agricultural productivism? An antipodean viewpoint. Progress in Human Geography. 2015, 39 (5): 621–635. [CrossRef]

| No. | Age | Gender | Educational level | Category | Locality |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 45 | M | University degree | Newcomer/NGO | Hosman |

| 2 | 39 | M | University degree | NGO | Hosman |

| 3 | 41 | F | University degree | Newcomer/NGO | Hosman |

| 4 | 64 | M | University degree | Public administration/ Town planning officer | Hosman |

| 5 | 29 | F | University degree | Local | Hosman |

| 6 | 30 | F | High school | Local | Hosman |

| 7 | 54 | M | University degree | Newcomer/entrepreneur | Hosman |

| 8 | 56 | F | High school | Local | Hosman |

| 9 | 52 | F | Post-secondary education | Local / Town hall official | Hosman |

| 10 | 36 | M | University degree | Newcomer/Contractor/Blacksmith | Hosman |

| 11 | 39 | M | University degree | Newcomer/NGO | Hosman |

| 12 | 36 | M | University degree | Newcomer | Râu Sadului |

| 13 | 48 | M | University degree | NGO | Râu Sadului |

| 14 | 38 | F | University degree | Agro-tourism entrepreneur | Râu Sadului |

| 15 | 38 | M | University degree | Public administration/Mayor | Râu Sadului |

| 16 | 40 | M | Postgraduate qualification | Newcomer | Râu Sadului |

| 17 | 40 | F | University degree | Newcomer | Râu Sadului |

| 18 | 38 | M | University degree | Local | Râu Sadului |

| 19 | 54 | F | University degree | Local | Râu Sadului |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).