Introduction

The sarcomere is the morphological and functional contractile unit in striated skeletal and cardiac muscle, and is located between two adjacent Z-discs in myofibrils. Cytoskeletal proteins such as actin and myosin help maintain the structure of the sarcomere. Alpha-actinin 2, a major component of Z-discs, forms antiparallel rod-shaped dimers that crosslink actin filaments and stabilize the contractile apparatus in the sarcomere [

1].

The synaptopodin family of proteins contains at least three members, namely synaptopodin, synaptopodin 2 and synaptopodin 2-like protein (SYNPO2L). Synaptopodin 2 and SYNPO2L are highly expressed in skeletal and cardiac muscle. These proteins localize at the Z-discs of the sarcomere and are involved in the morphogenesis and function of skeletal and heart muscle [

2]. SYNPO2L consists of two isoforms encoded by a single gene, SYNPO2La (long form, 978 amino acids) and SYNPO2Lb (short form, 749 amino acids) [

3]. Both proteins have a nuclear localization signal and SYNPO2La has an N-terminal PDZ domain. SYNPO2La is predominantly expressed in adult skeletal and heart muscle. The expression of SYNPO2Lb is mainly restricted to the early developmental stage of skeletal and cardiac muscle. Knockdown of SYNPO2La in zebrafish results in decreased heart contractility and impaired formation of skeletal muscle [

3]. Furthermore, overexpression of SYNPO2Lb in mice causes decreased muscle contractility [

3], suggesting that SYNPO2L is crucial for the formation and maintenance of the sarcomere. SYNPO2L and other members of the synaptopodin family can bind to a-actinin [

3]. However, the mechanism by which SYNPO2L interacts with actin in the Z-discs of the sarcomere remains to be clarified.

In the present study, we analyzed the interaction of SYNPO2L with actin filaments and a-actinin in vitro. We demonstrated that both SYNPO2La and SYNPO2Lb could directly bind to a-actinin, and the binding stabilized the SYNPO2L/a-actinin complex. In addition, SYNPO2L in the absence of a-actinin caused actin filaments to form bundles and also enhanced the formation of a-actinin-dependent actin bundles. These results suggest that SYNPO2L has an essential role in stabilizing the morphology of Z-discs by directly bundling actin filaments and enhancing the effect of a-actinin-mediated bundle formation.

Materials and Methods

2.Antibodies and Reagents

Rabbit anti-SYNPO2L antibody (cat# 21480-1-AP) was purchased from Proteintech Group Inc (Rosemont, IL, USA). Mouse monoclonal anti-a-actinin (clone EA-53, cat# A7811) was purchased from Merck KgaA (Darmstadt, Germany). Alexa Fluor 488-conjugated donkey anti-rabbit IgG (cat# A21206), Alexa Fluor 555-conjugated donkey anti-rabbit IgG (cat# A31572), Alexa Fluor 555-conjugated donkey anti-mouse IgG (cat# A31570), Alexa Fluor 568-conjugated donkey anti-goat IgG (cat# A11057), Alexa Fluor 488-conjugated goat anti-mouse IgG antibody (cat# A11001), Alexa Fluor 594-conjugated goat anti-rabbit IgG antibody (cat# A11037) and Alexa Fluor 488-labeled phalloidin (cat# A12379) were obtained from Thermo Fisher Scientific (MA, USA).

2.Isolation and Cell Culture of Mouse Cardiomyocytes

First, plates were prepared for cell seeding. Specifically, one sterile glass coverslip measuring 1 cm × 1 cm was placed into each well of a 24-well plate. Subsequently, 0.5 ml of a 50-fold diluted collagen solution (cat# IPC-30, KOKEN, Tokyo, Japan) was added to each well. The plates were then incubated at 37°C for 1 h, followed by several washes of the glass coverslips with distilled water and then air-drying. All animal handling and experimental procedures were approved by the Animal Care and Use Committee of Okayama University. Primary cardiomyocytes were isolated from the ventricles of neonatal mice (C57BL/6J, CLEA Japan, Shizuoka, Japan) on postnatal day Mice were euthanized by decapitation under isoflurane anesthesia, then the heart was removed and the ventricles were dissected, and the atria were removed. The ventricular tissue was subsequently cut into several fragments approximately 2 mm2 in size. These ventricular tissue fragments were gently agitated in 10 ml of phosphate-buffered saline and washed three times. The tissue was then subjected to enzymatic digestion using 0.06% trypsin (10 ml) at 37°C for 10 min with gentle agitation, and the enzyme treatment was repeated three times. The supernatant containing the suspended cells was promptly supplemented with DMEM containing 10% FCS to halt trypsinization, and cells were collected by centrifugation at 400 × g for 5 min. The cells were re-suspended in fresh DMEM containing 10% FCS and preincubated at 37°C for 45 min to remove fibroblasts. Subsequently, the cells were seeded into collagen-coated 24-well plates (5 × 104 cells per well) prepared as described above, and cultured at 37°C under 5%CO2.

2.Purification of Recombinant Proteins

His-tagged human SYNPO2La or SYNPO2Lb were expressed using a wheat germ cell-free expression system (CellFree Sciences, Matsuyama, Japan), purified by immobilized-nickel affinity chromatography with Ni Sepharose™ 6 Fast Flow (Cat#17531802, Cytiva). These proteins were resolved in 100 mM NaCl, 50 mM Tris-HCl, 500 mM imidazole, pH 8.0 and stored at 4°C until use.

2.Fluorescent Microscopy

Cultured cardiomyocytes were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde and stained by immunofluorescence as described previously [

4]. SYNPO2L, a-actinin and actin filaments were visualized by double immunofluorescence. Samples were examined using a spinning-disc confocal microscope system (X-Light Confocal Imager; CREST OPTICS S.P.A., Rome, Italy) combined with an inverted microscope (IX-71; Olympus Optical Co., Ltd., Tokyo, Japan) and an iXon+ camera (Oxford Instruments, Oxfordshire, UK). The confocal system was controlled by MetaMorph software (Molecular Devices, CA, USA). When necessary, images were processed using Adobe Photoshop 2024 or Adobe Illustrator 2024 software.

2.Electron Microscopy

For negative staining of indicated proteins, reaction mixtures containing 1 M a-actinin, SYNPO2La or SYNPO2Lb, and 4 mM actin filaments were incubated at room temperature for 3 h. Rabbit skeletal muscle-derived a-actinin (cat# AT01-A, Cytoskeleton Inc., Denver, CO, USA) was reconstituted in F buffer (100 mM KCl, 10 mM Tris-HCl, 0.2 mM CaCl2, 1 mM MgCl2, 1 mM DTT, 0.2 mM ATP, pH 7.4). Actin (APHL99, Cytoskeleton Inc.) was polymerized in F buffer for 1 h. The samples were absorbed into a Formvar- and carbon-coated copper grid and then stained with 3% uranyl acetate in ddH2O for 2 min. Electron microscopy was carried out using a Hitachi H-7650 transmission electron microscope (TEM).

2.Morphometry

To quantify actin bundle formation, the reaction mixture was negatively stained and observed by TEM. TEM images were taken at low magnification (×300). The area corresponding to actin bundles in the TEM image (512 × 512 pixels) was quantified using Image J software version 1.52a. The quantification was based on either 48 images (a-actinin/F-actin), 19 images (SYNPO2La/F-actin), 29 images (SYNPO2La/a-actinin/F-actin), 20 images (SYNPO2Lb/F-actin), or 20 images (SYNPO2Lb/a-actinin/F-actin) from three or more independent experiments.

2.High-Speed Atomic Force Microscopy (AFM)

High-speed AFM was conducted using a custom-built, tapping mode-based instrument [

5]. An Olympus microcantilever (cat# AC10, Tokyo, Japan) with a resonance frequency of approximately 500 kHz and a spring constant of approximately 0.1 N/m in liquid was used. Since the AC10 microcantilever does not have a sharpened tip, we used an amorphous carbon tip deposited by electron-beam deposition on the cantilever end. The equipment is described in detail in a previous paper [

6].

The proteins α-actinin and SYNPO2La were observed using bare mica substrates; 2 μl of α-actinin solution or SYNPO2La was placed on a freshly cleaved mica surface, incubated for 3 min, and then washed with observation buffer (5 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.0), 0.2 mM CaCl2, 0.5 mM DTT, 100 mM KCl, 2 mM MgCl2) to remove excess molecules immediately before high-speed AFM observations. To observe the interaction between α-actinin and SYNPO2La, α-actinin was first adsorbed onto the mica substrate, then SYNPO2La was added to the observation buffer during high-speed AFM, and the binding of SYNPO2La to α-actinin was observed after a few minutes.

A positively charged lipid bilayer was used as a substrate to retain actin filaments. This was to hold the negatively charged actin filaments to the substrate while preventing strong adsorption of α-actinin and SYNPO2La to the substrate. Neutral phospholipid DPPC and positively charged phospholipid DATAP were dissolved in chloroform and mixed at a molar ratio of DPPC : DPTAP = 7 : 3, after which the chloroform was evaporated. Ultra-pure water was added to adjust the concentration to 1 mg/ml, and the lipid vesicle suspension was diluted to 0.1 mg/ml with 5 mM MgCl2 solution and subjected to about 20 rounds of sonication using a tip sonicator. Then, 2 μl of the prepared lipid solution was dropped onto the mica surface, incubated for 10 minutes to develop the lipid bilayer, and then washed with 80 μl of observation buffer to remove excess vesicles. 2 μl of actin filaments were dropped onto the lipid bilayer substrate, incubated for 5 minutes, and the substrate surface was washed again with 80 μl of observation buffer. When adding α-actinin or SYNPO2La, injection was performed into the observation buffer within the cantilever holder. All observations were conducted at room temperature.

2.Ethics and Animal Use Statement

All experiments and protocols were approved by the institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Okayama University (OKU-2024424). All efforts were made to minimize animal suffering. Mice were euthanized under anesthesia before whole hearts were removed.

2.Statistical Analysis

Data were analyzed for statistical significance using KaleidaGraph software for Macintosh, version 4.1 (Synergy Software Inc., VT, USA). An analysis of variance and Tukey’s honest significant difference post-hoc test were used to compare several groups. P values of less than 0.05 (*) or 0.01 (**) were considered significant.

Results

3.SYNPO2L Colocalizes with a-Actinin and Actin Filaments at Sarcomeric Z-Discs

We first investigated the localization of SYNPO2L in cultured mouse cardiomyocytes using double immunofluorescence experiments. SYNPO2L was colocalized with actin filaments and a-actinin, a marker of sarcomeric Z-discs (

Figure 1).

Discussion

SYNPO2La and SYNPO2Lb are expressed and colocalized with a-actinin and actin filaments at sarcomeric Z-discs in mouse cardiomyocytes [

3]. In the current study, we investigated the role of SYNPO2L by determining the direct interactions between SYNPO2L, a-actinin and actin filaments

in vitro. Double immunofluorescence studies confirmed that these three proteins are colocalized at sarcomeric Z-discs in mouse cardiomyocytes (

Figure 1). Recombinant SYNPO2La or SYNPO2Lb formed complexes with a-actinin (

Figure 2). Furthermore, SYNPO2La or SYNPO2Lb caused direct bundling of actin filaments. In particular, SYNPO2La enhanced a-actinin-mediated formation of actin bundles (

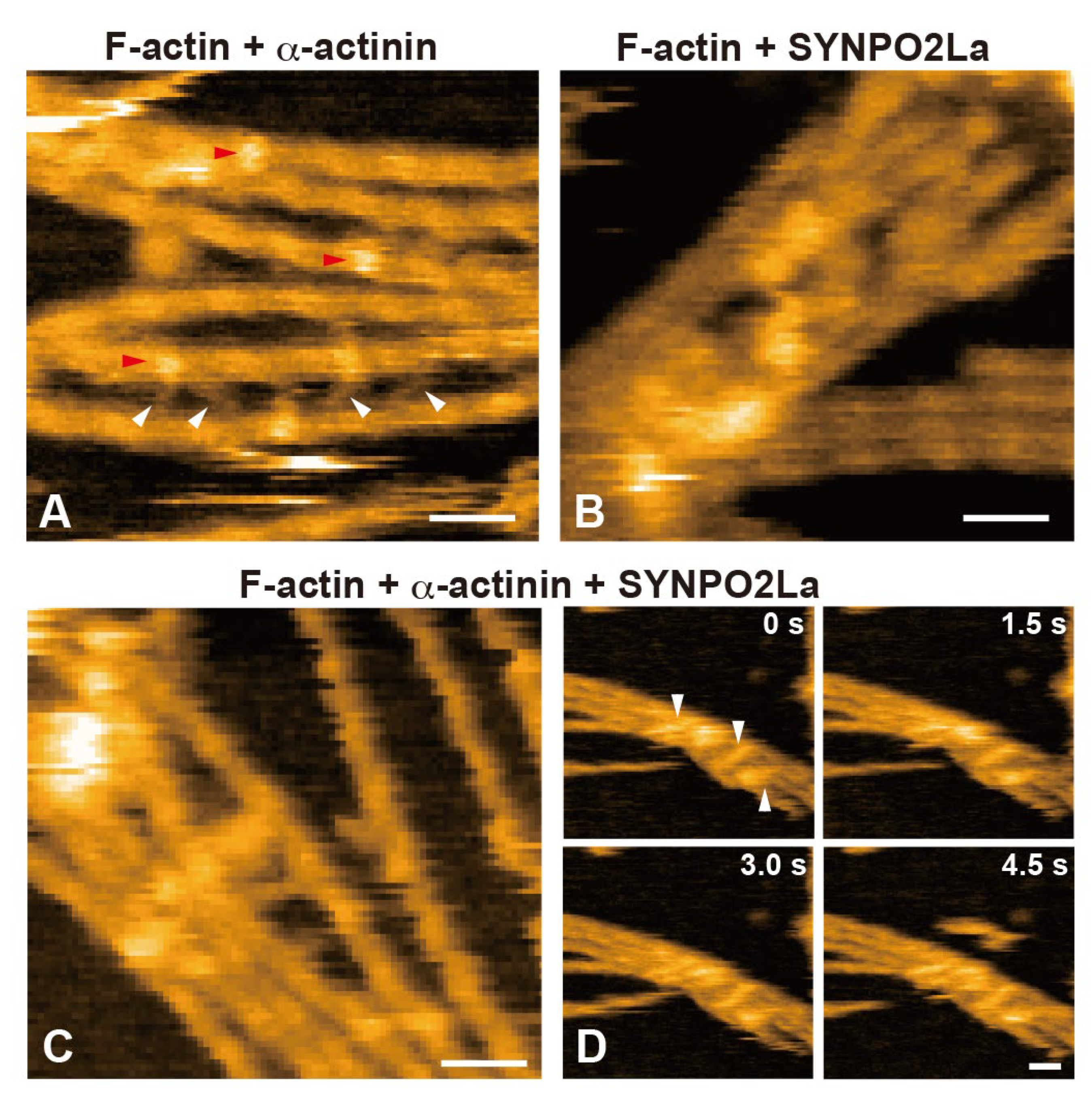

Figure 3). Finally, high-speed AFM observations showed that SYNPO2La directly bound to a-actinin (

Figure 4), and the a-actinin, SYNPO2La and SYNPO2La/a-actinin complex crosslinked adjacent actin filaments. Furthermore, SYNPO2La stabilized a-actinin on rhe actin filaments (

Figure 5).

4.SYNPO2L Directly Binds to and Bundles Actin Filaments

SYNPO2L is expressed in cardiac muscle, skeletal muscle and smooth muscle [

3]. In cardiomyocytes, SYNPO2L is localized at sarcomeric Z-discs, in which actin and actin-related proteins such as a-actinin and titin are enriched. These proteins likely regulate the actin cytoskeleton to maintain the structure of Z-discs [

9]. Beqqali and colleagues used immunoprecipitation to show that SYNPO2Lb interacts with a-actinin in COS-1 cells that overexpress SYNPO2Lb or in C2C12 myotubes [

3]. In the current study, we demonstrated that SYNPO2La or SYNPO2Lb bound directly to actin filaments, which resulted in the formation of actin bundles in vitro (

Figure 3 and 5). It seems that SYNPO2L isoforms have direct and indirect effects on actin filaments, similar to the direct and indirect effects of other synaptopodin family proteins [

10,

11,

12]. As both SYNPO2La and SYNPO2Lb could bundle actin (

Figure 3), SYNPO2L may have several actin-binding sites and/or an increase in the number of actin-binding sites caused by self-polymerization. Although both SYNPO2La and SYNPO2Lb interacted with a-actinin (

Figure 2), SYNPO2Lb did not enhance a-actinin-mediated actin bundle formation, in contrast to the additive effect observed with SYNPO2La (

Figure 3). SYNPO2Lb is expressed in the embryonic heart, while SYNPO2La is expressed mainly in the adult heart [

3]. Furthermore, overexpression of SYNPO2Lb in mice caused heart dysfunction and perturbed Z-disc morphology [

13]. Taken together, these findings suggest that the different effects of SYNPO2La and SYNPO2Lb on a-actinin-dependent formation of actin bundles may reflect the existence of isoform-specific functions, although further work is needed to clarify this hypothesis.

4.SYNPO2La May Bind to the C-Terminal Globular Domain of Antiparallel a-Actinin Dimers and Help Stabilize a-Actinin

In the present study, the binding of the globular form of SYNPO2La to a-actinin was captured by high-speed AFM (

Figure 4). Alpha-actinin forms antiparallel dimers that have a globular shape at both ends and these globular regions crosslink actin filaments [

1]. We showed that SYNPO2La bound to the globular region of a-actinin dimers (

Figure 4D and

Supplementary Movie 1), enhancing the formation and stabilization of actin bundles (

Figure 5C and D). Therefore, it is conceivable that the interaction of SYNPO2La with a-actinin might affect the crosslinking ability of a-actinin. As the a-actinin/SYNPO2La complex facilitated the formation of actin bundles, the interaction between a-actinin and SYNPO2La may contribute to the stability of a-actinin on actin filaments.

In the past several years, multiple genome-wide association studies have identified several genomic loci associated with atrial fibrillation. Especially, the loss-of-function of several actin-related proteins localized at Z-discs causes cardiac dysfunction [

14]. A recent report indicates that loss-of-function variants in the SYNPO2L gene increase the risk of atrial fibrillation. However, the precise role of SYNPO2L at Z-discs in that study was not determined [

15]. The effect of SYNPO2L on actin and a-actinin activity demonstrated in this study might represent an essential physiological function of SYNPO2L, and help elucidate the pathogenesis of atrial fibrillation, especially those forms caused by SYNPO2L variants.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org, Movie S1: live imaging of SYNPO2La by high-speed AFM, Movie S2: live imaging of SYNPO2La/a-actinin by high-speed AFM, Movie S3: Live imaging of fusion process of a-actinin to SYNPO2La by high-speed AFM.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, H.Y. and K.Takei.; investigation, H.Y., H.O., N.T., M.A., T.A., K.K., K.Takahashi, T.U.; resources, E.T.; writing—original draft preparation, H.Y. and K.T.; writing—review and editing, K.N. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Ministry of Education, Science, Sports and Culture of Japan (grant numbers 24K01309 to T. Uchihashi, 23K27170 to K. Takei, 22K06580 to T. Abe), by Okayama University Central Research Laboratory, and by Ehime University Proteo-Science Center (PROS).

Institutional Review Board Statement

All experiments and protocols were approved by the institutional animal care and use committee of Okayama University (OKU-2024424). All efforts were made to minimize animal suffering. After euthanizing mice, whole hearts were removed.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank to all people involved in Okayama University Central Research Laboratory for technical assistant.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

References

- Sjöblom, B.; Salmazo, A.; Djinović-Carugo, K. Alpha-actinin structure and regulation. Cell Mol. Life Sci. 2008, 65, 2688–2701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chalovich, J.M.; Schroeter, M.M. Synaptopodin family of natively unfolded, actin binding proteins: physical properties and potential biological functions. Biophys. Rev. 2010, 2, 181–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beqqali, A.; Monshouwer-Kloots, J.; Monteiro, R.; Welling, M.; Bakkers, J.; Ehler, E.; Verkleij, A.; Mummery, C.; Passier, R. CHAP is a newly identified Z-disc protein essential for heart and skeletal muscle function. J. Cell Sci. 2010, 123, 1141–1150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- La, T.M.; Tachibana, H.; Li, S.A.; Abe, T.; Seiriki, S.; Nagaoka, H.; Takashima, E.; Takeda, T.; Ogawa, D.; Makino, S.I.; Asanuma, K.; Watanabe, M.; Tian, X.; Ishibe, S.; Sakane, A.; Sasaki, T.; Wada, J.; Takei, K.; Yamada, H. Dynamin 1 is important for microtubule organization and stabilization in glomerular podocytes. FASEB J. 2020, 34, 16449–16463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ando, T.; Uchihashi, T.; Fukuma, T. High-speed atomic force microscopy for nano-visualization of dynamic biomolecular processes. Prog. in Surf. Sci. 2008, 83, 337–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uchihashi, T.; Kodera, N.; Ando, T. Guide to video recording of structure dynamics and dynamic processes of proteins by high-speed atomic force microscopy. Nat Protoc., 2012, 7, 1193–1206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ylänne, J.; Scheffzek, K.; Young, P.; Saraste, M. Crystal structure of the alpha-actinin rod reveals an extensive torsional twist. Structure 2001, 9, 597–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meyer, R.K.; Aebi, U. Bundling of actin filaments by alpha-actinin depends on its molecular length. J. Cell Biol. 1990, 110, 2013–2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gautel, M.; Djinović-Carugo, K. The sarcomeric cytoskeleton: from molecules to motion. J. Exp. Biol. 2016, 219, 135–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Asanuma, K.; Kim, K.; Oh, J.; Giardino, L.; Chabanis, S.; Faul, C.; Reiser, J.; Mundel, P. Synaptopodin regulates the actin-bundling activity of alpha-actinin in an isoform-specific manner. J. Clin. Invest. 2005, 115, 1188–1198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schroeter, M.M.; Beall, B.; Heid, H.W.; Chalovich, J.M. In vitro characterization of native mammalian smooth-muscle protein synaptopodin Biosci. Rep. 2008, 28, 195–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linnemann, A.; Vakeel, P.; Bezerra, E.; Orfanos, Z.; Djinović-Carugo, K.; van der Ven, P.F.; Kirfel, G.; Fürst, D.O. Myopodin is an F-actin bundling protein with multiple independent actin-binding regions. J. Muscle Res. Cell Motil. 2013, 34, 61–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van Eldik, W.; den Adel, B.; Monshouwer-Kloots, J.; Salvatori, D.; Maas, S.; van der Made, I.; Creemers, E.E.; Frank, D.; Frey, N.; Boontje, N.; van der Velden, J.; Steendijk, P.; Mummery, C.; Passier, R.; Beqqali, A. Z-disc protein CHAPb induces cardiomyopathy and contractile dysfunction in the postnatal heart. PLoS One 2017, 12, e0189139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yotti, R.; Seidman, C.E.; Seidman, J.G. Advances in the Genetic Basis and Pathogenesis of Sarcomere Cardiomyopathies. Annu. Rev. Genomics. Hum. Genet. 2019, 20, 129–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clausen, A.G.; Vad, O.B.; Andersen, J.H.; Olesen, M.S. Loss-of-Function Variants in the SYNPO2L Gene Are Associated With Atrial Fibrillation. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 2021, 8, 650667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).