Submitted:

13 September 2024

Posted:

15 September 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

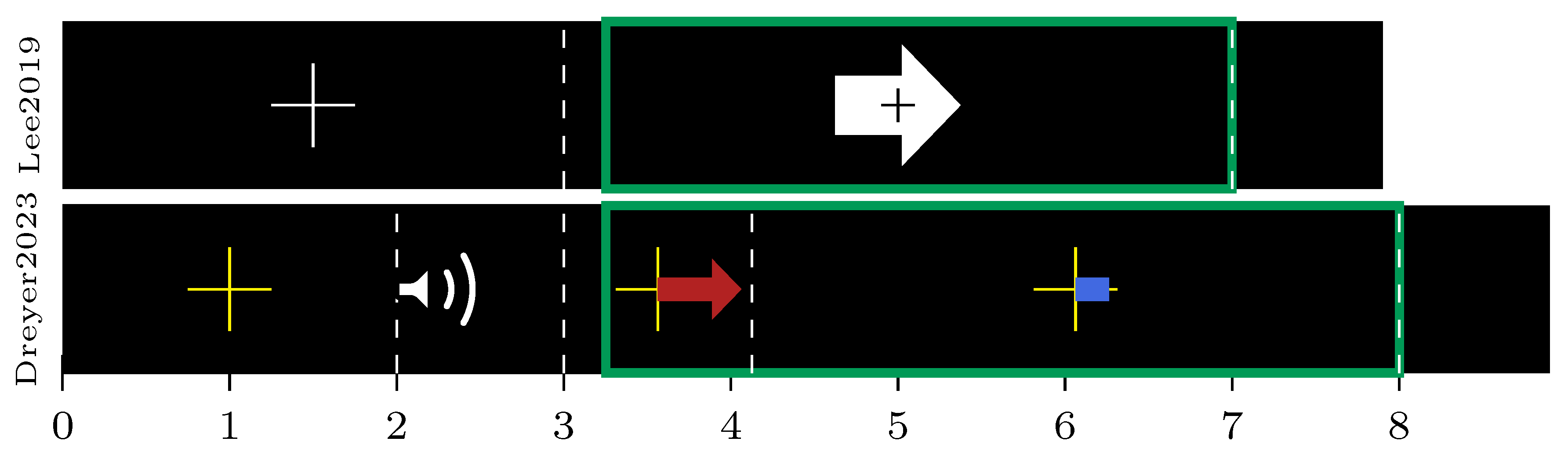

2.1. Datasets

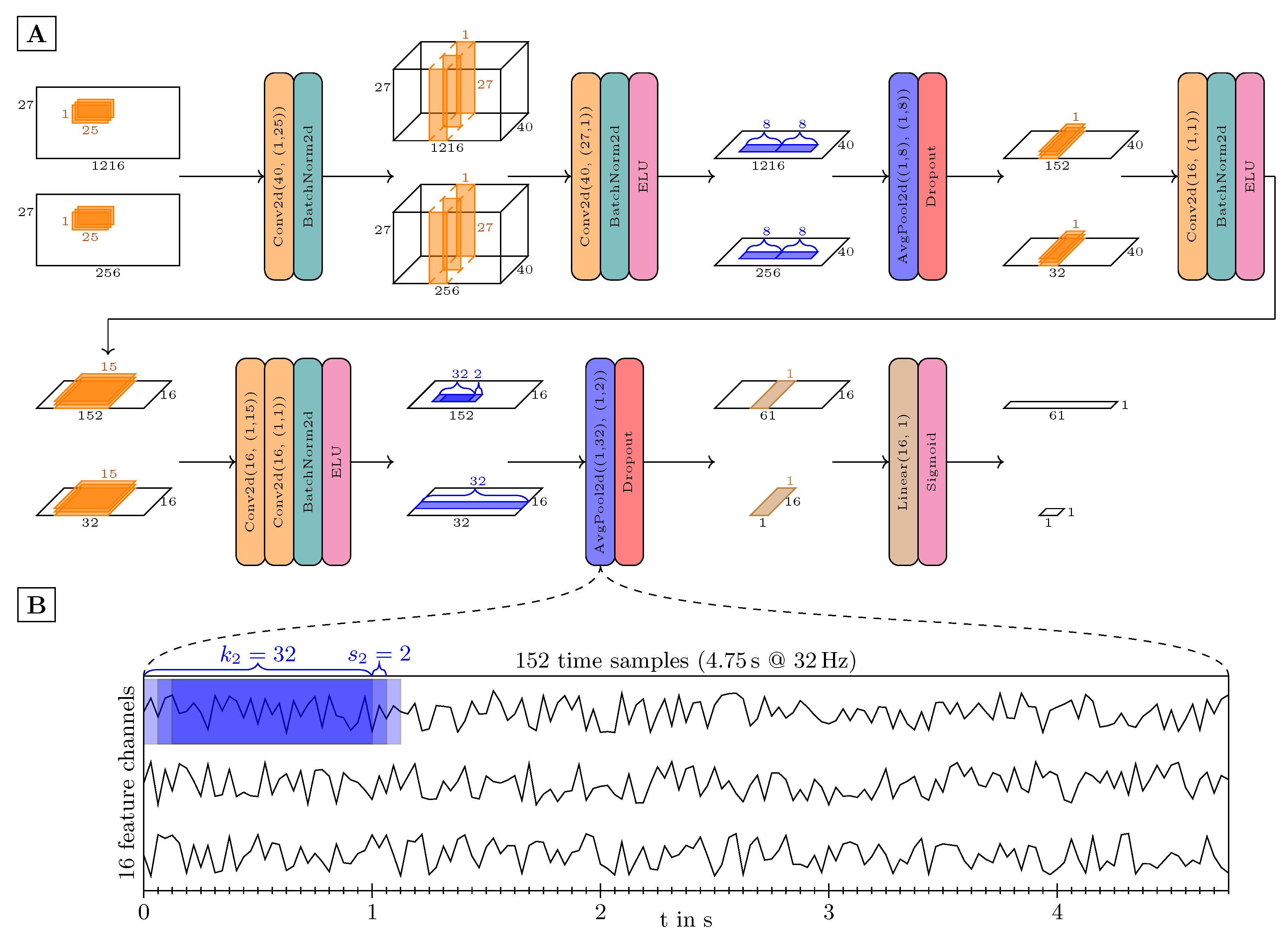

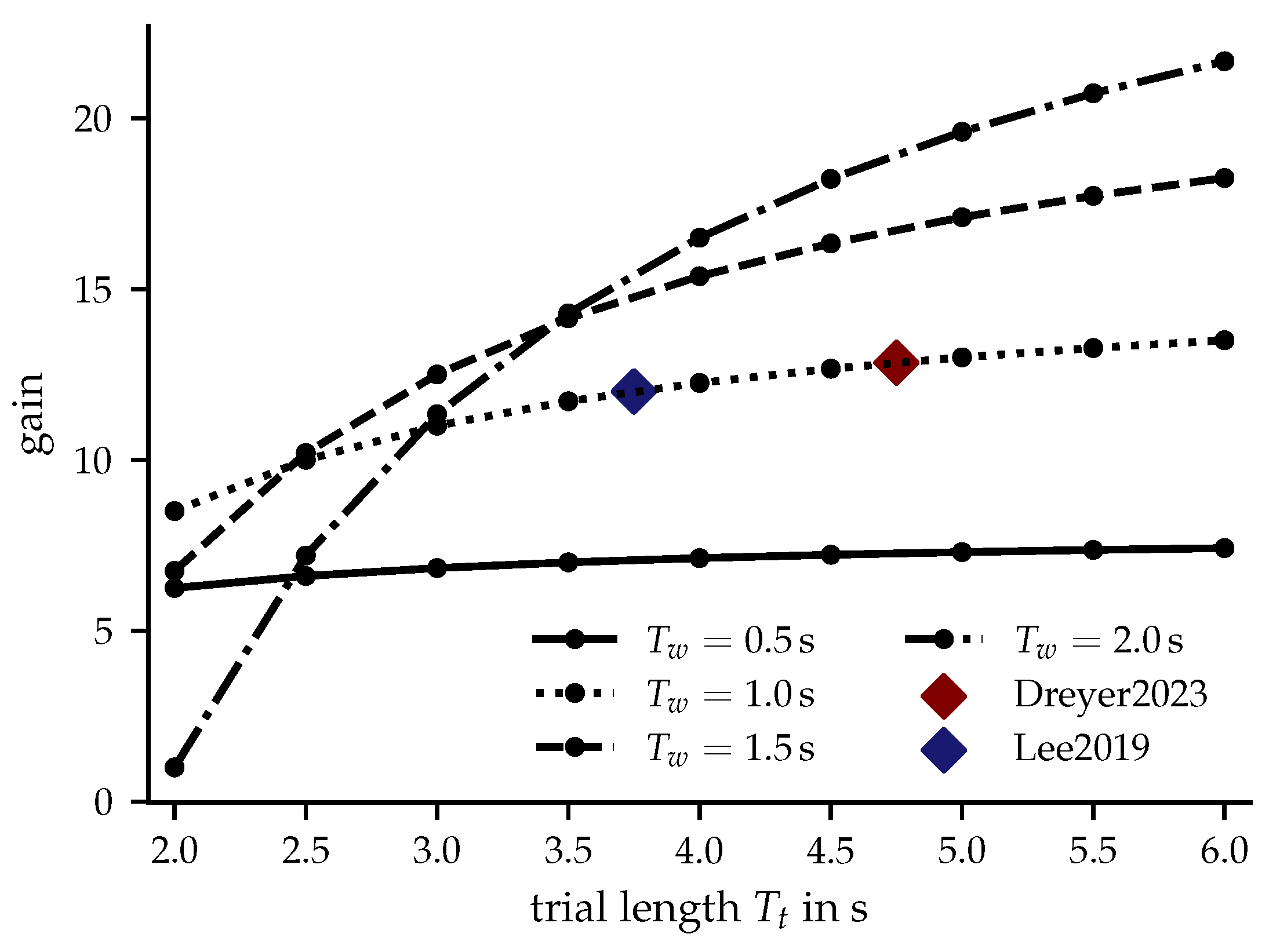

2.2. Real-Time Adaptive Pooling

2.3. Training

2.3.1. Data Split

2.3.2. Training Procedure

2.4. Evaluation

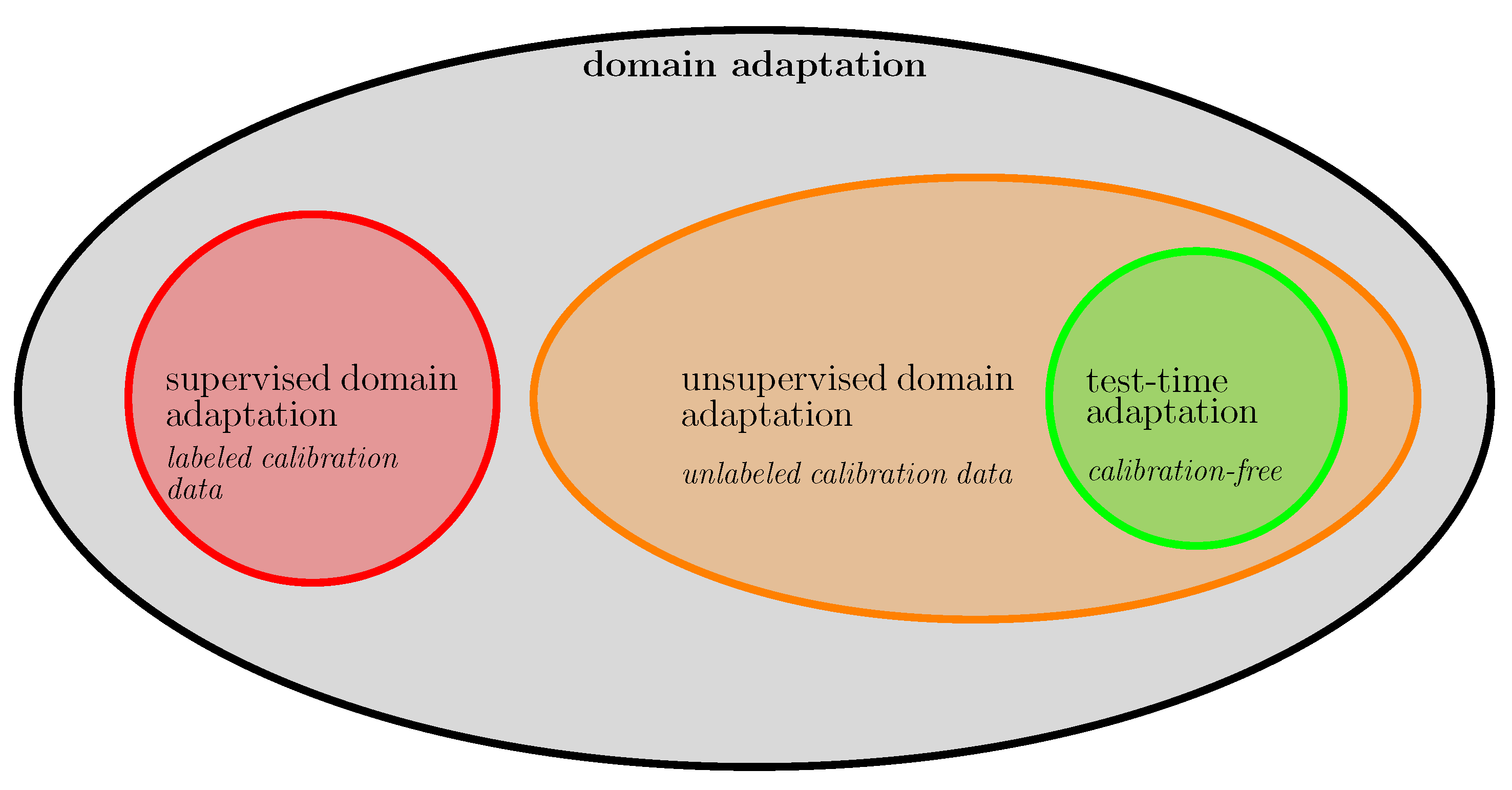

2.5. Transfer Learning and Domain Adaptation

2.6. Alignment

2.7. Adaptive Batch Normalization

2.8. Entropy Minimization

2.9. Benchmark Method

3. Results

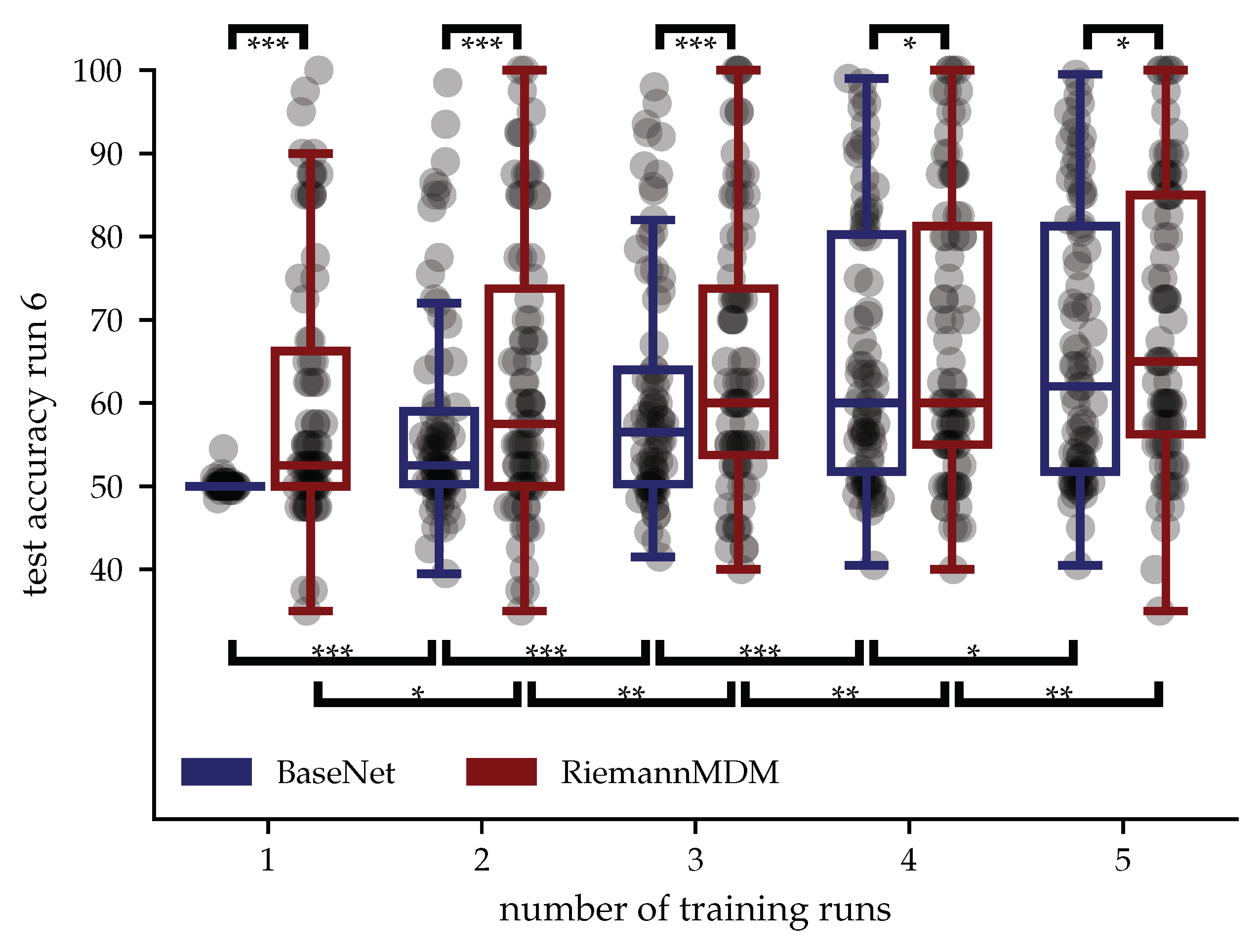

3.1. Within-Subject

3.2. Cross-Subject

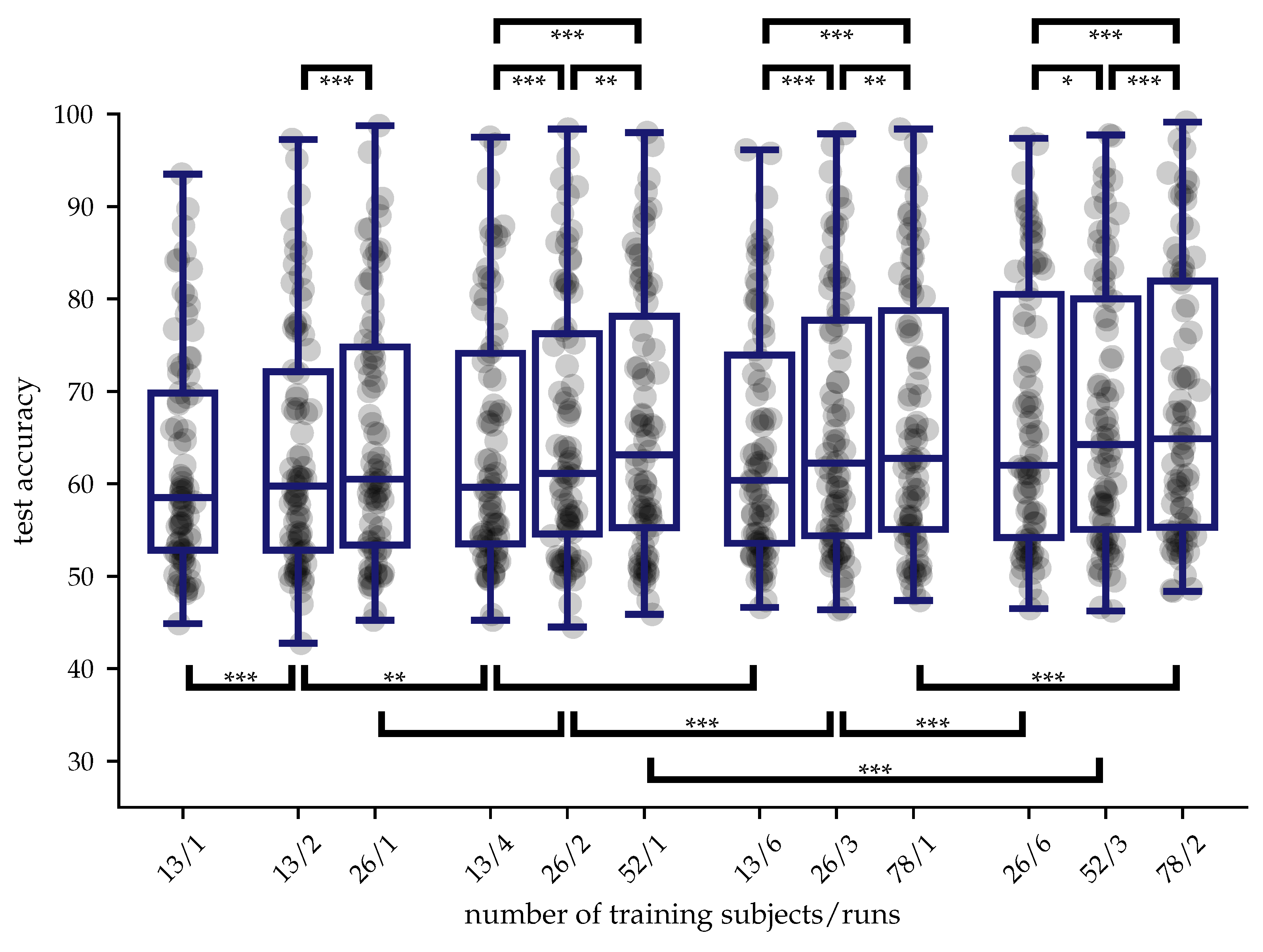

3.2.1. Amount and Diversity of Training Data

3.2.2. Domain Adaptation Settings

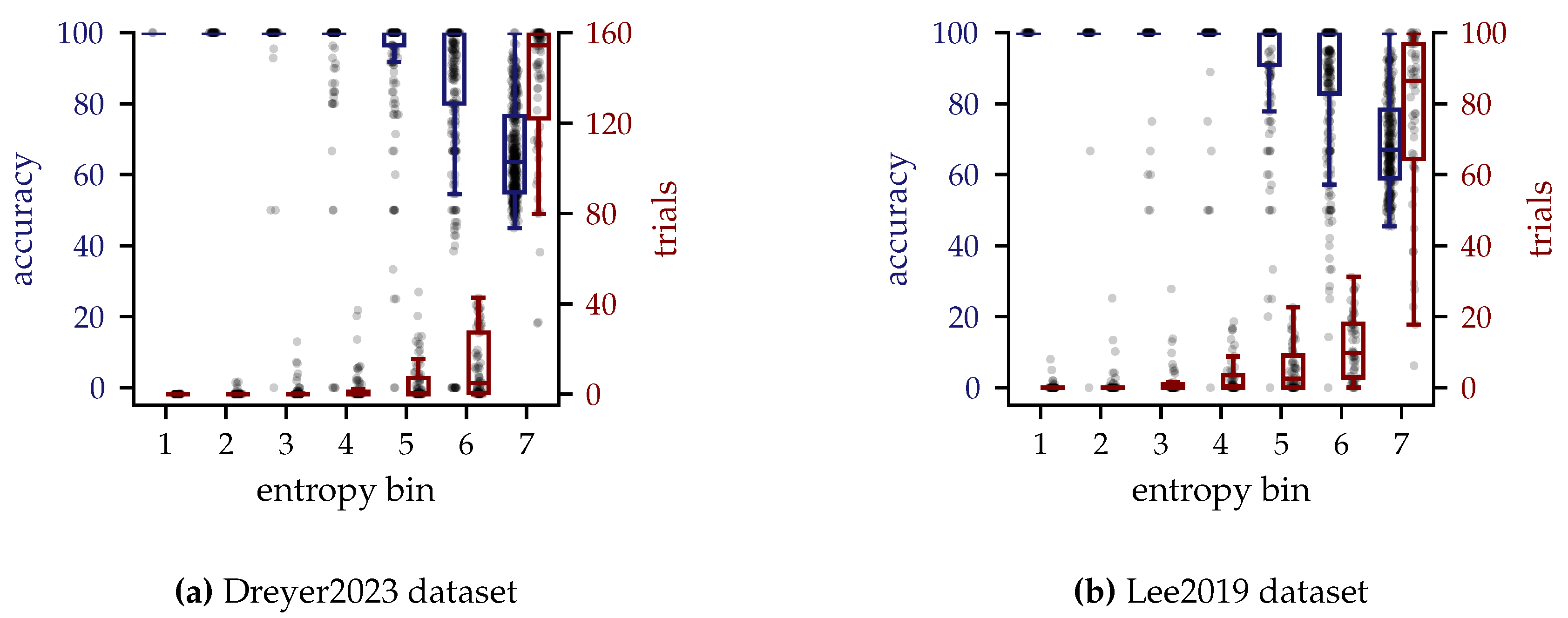

3.2.3. Entropy

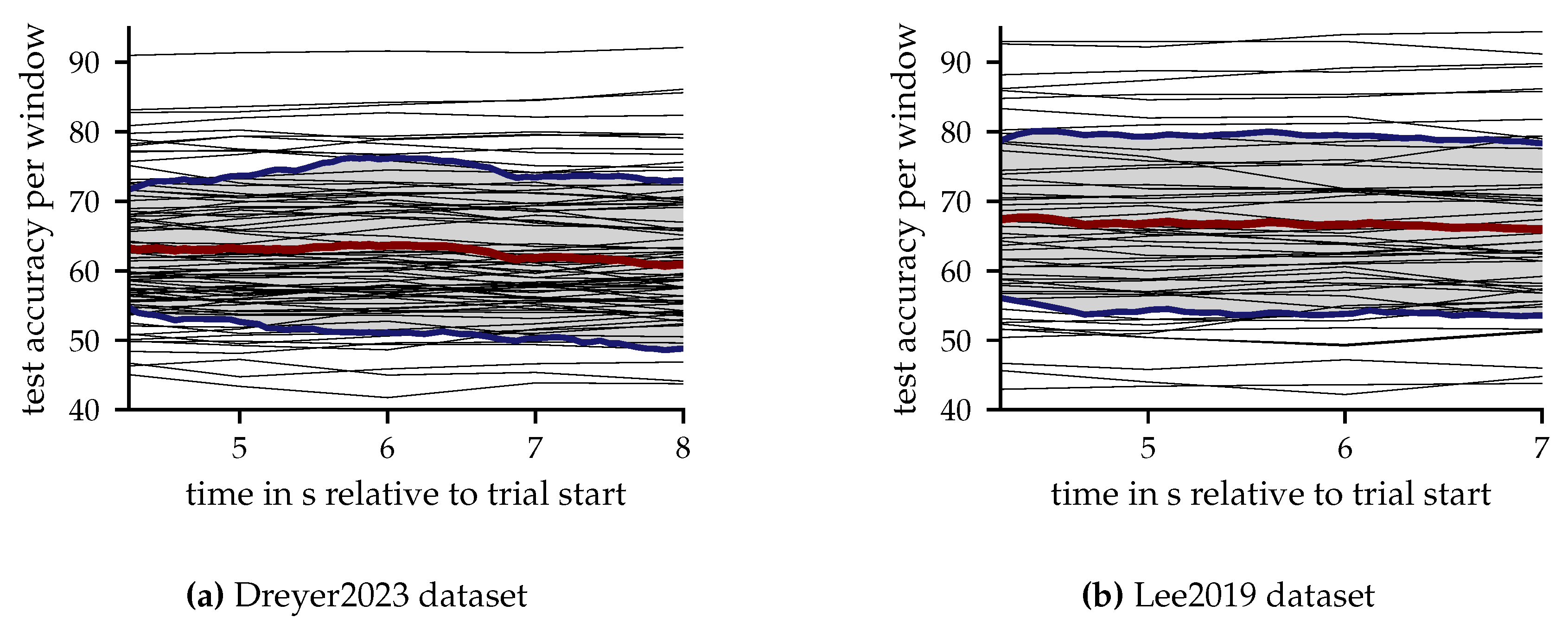

3.2.4. Results per Window

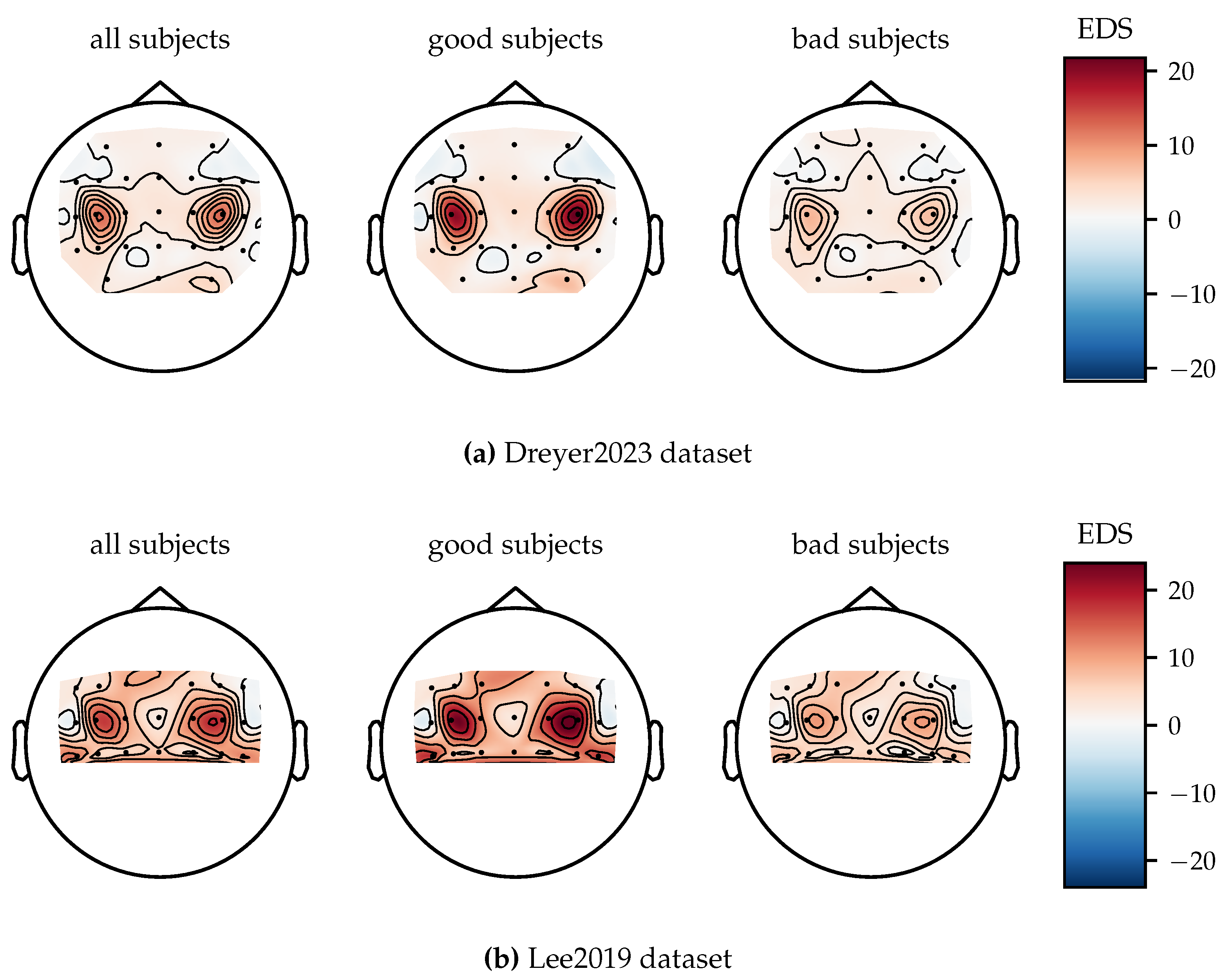

3.2.5. Spatial Patterns

4. Discussion

4.1. Data Availability and Data Composition

4.2. Domain Adaptation

4.3. Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A.

Appendix A.1. Dataset and RAP Hyperparameters

| dataset | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dreyer2023 | 1 | 256 | 32 | 16 | [8, 32] | [8, 2] | 61 | |

| Lee2019 | 1 | 256 | 32 | 16 | [8, 32] | [8, 2] | 45 |

Appendix A.2. Within-Subject

References

- Peksa, J. & Mamchur, D. State-of-the-Art on Brain-Computer Interface Technology. Sensors. 23, 6001 (2023). [CrossRef]

- Cervera, M., Soekadar, S., Ushiba, J., Millán, J., Liu, M., Birbaumer, N. & Garipelli, G. Brain-computer interfaces for post-stroke motor rehabilitation: a meta-analysis. Annals Of Clinical And Translational Neurology. 5, 651-663 (2018).

- Soekadar, S., Witkowski, M., Mellinger, J., Ramos, A., Birbaumer, N. & Cohen, L. ERD-based online brain-machine interfaces (BMI) in the context of neurorehabilitation: optimizing BMI learning and performance. IEEE Transactions On Neural Systems And Rehabilitation Engineering. 19, 542-549 (2011). [CrossRef]

- Decety, J. The neurophysiological basis of motor imagery. Behavioural Brain Research. 77, 45-52 (1996). [CrossRef]

- Lee, M., Kwon, O., Kim, Y., Kim, H., Lee, Y., Williamson, J., Fazli, S. & Lee, S. EEG dataset and OpenBMI toolbox for three BCI paradigms: An investigation into BCI illiteracy. GigaScience. 8, giz002 (2019). [CrossRef]

- Sannelli, C., Vidaurre, C., Müller, K. & Blankertz, B. A large scale screening study with a SMR-based BCI: Categorization of BCI users and differences in their SMR activity. PloS One. 14, e0207351 (2019). [CrossRef]

- Zhang, R., Li, F., Zhang, T., Yao, D. & Xu, P. Subject inefficiency phenomenon of motor imagery brain-computer interface: Influence factors and potential solutions. Brain Science Advances. 6, 224-241 (2020). [CrossRef]

- Perdikis, S., Tonin, L., Saeedi, S., Schneider, C. & Millán, J. The Cybathlon BCI race: Successful longitudinal mutual learning with two tetraplegic users. PLoS Biology. 16, e2003787 (2018). [CrossRef]

- Korik, A., McCreadie, K., McShane, N., Du Bois, N., Khodadadzadeh, M., Stow, J., McElligott, J., Carroll, Á. & Coyle, D. Competing at the Cybathlon championship for people with disabilities: long-term motor imagery brain–computer interface training of a cybathlete who has tetraplegia. Journal Of NeuroEngineering And Rehabilitation. 19, 95 (2022). [CrossRef]

- McFarland, D. & Wolpaw, J. Brain–computer interface use is a skill that user and system acquire together. PLoS Biology. 16, e2006719 (2018).

- Shenoy, K. & Carmena, J. Combining decoder design and neural adaptation in brain-machine interfaces. Neuron. 84, 665-680 (2014). [CrossRef]

- Orsborn, A., Moorman, H., Overduin, S., Shanechi, M., Dimitrov, D. & Carmena, J. Closed-loop decoder adaptation shapes neural plasticity for skillful neuroprosthetic control. Neuron. 82, 1380-1393 (2014). [CrossRef]

- Sitaram, R., Ros, T., Stoeckel, L., Haller, S., Scharnowski, F., Lewis-Peacock, J., Weiskopf, N., Blefari, M., Rana, M., Oblak, E. & Others Closed-loop brain training: the science of neurofeedback. Nature Reviews Neuroscience. 18, 86-100 (2017). [CrossRef]

- Kober, S., Witte, M., Ninaus, M., Neuper, C. & Wood, G. Learning to modulate one’s own brain activity: the effect of spontaneous mental strategies. Frontiers In Human Neuroscience. 7 pp. 695 (2013).

- Gaume, A., Vialatte, A., Mora-Sánchez, A., Ramdani, C. & Vialatte, F. A psychoengineering paradigm for the neurocognitive mechanisms of biofeedback and neurofeedback. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews. 68 pp. 891-910 (2016). [CrossRef]

- Mladenović, J., Mattout, J. & Lotte, F. A generic framework for adaptive EEG-based BCI training and operation. Brain–Computer Interfaces Handbook. pp. 595-612 (2018).

- Craik, A., He, Y. & Contreras-Vidal, J. Deep learning for electroencephalogram (EEG) classification tasks: a review. Journal Of Neural Engineering. 16, 031001 (2019). [CrossRef]

- Vavoulis, A., Figueiredo, P. & Vourvopoulos, A. A Review of Online Classification Performance in Motor Imagery-Based Brain-Computer Interfaces for Stroke Neurorehabilitation. Signals. 4, 73-86 (2023). [CrossRef]

- Tayeb, Z., Fedjaev, J., Ghaboosi, N., Richter, C., Everding, L., Qu, X., Wu, Y., Cheng, G. & Conradt, J. Validating deep neural networks for online decoding of motor imagery movements from EEG signals. Sensors. 19, 210 (2019). [CrossRef]

- Jeong, J., Shim, K., Kim, D. & Lee, S. Brain-controlled robotic arm system based on multi-directional CNN-BiLSTM network using EEG signals. IEEE Transactions On Neural Systems And Rehabilitation Engineering. 28, 1226-1238 (2020). [CrossRef]

- Karácsony, T., Hansen, J., Iversen, H. & Puthusserypady, S. Brain computer interface for neuro-rehabilitation with deep learning classification and virtual reality feedback. Proceedings Of The 10th Augmented Human International Conference 2019. pp. 1-8 (2019).

- Stieger, J., Engel, S., Suma, D. & He, B. Benefits of deep learning classification of continuous noninvasive brain–computer interface control. Journal Of Neural Engineering. 18, 046082 (2021). [CrossRef]

- Forenzo, D., Zhu, H., Shanahan, J., Lim, J. & He, B. Continuous tracking using deep learning-based decoding for noninvasive brain–computer interface. PNAS Nexus. 3, pgae145 (2024). [CrossRef]

- Schirrmeister, R., Springenberg, J., Fiederer, L., Glasstetter, M., Eggensperger, K., Tangermann, M., Hutter, F., Burgard, W. & Ball, T. Deep learning with convolutional neural networks for EEG decoding and visualization. Human Brain Mapping. 38, 5391-5420 (2017). [CrossRef]

- Lawhern, V., Solon, A., Waytowich, N., Gordon, S., Hung, C. & Lance, B. EEGNet: a compact convolutional neural network for EEG-based brain-computer interfaces. Journal Of Neural Engineering. 15, 056013 (2018). [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S., Alawieh, H., Racz, F., Fakhreddine, R. & Millán, J. Transfer learning promotes acquisition of individual BCI skills. PNAS Nexus. 3, pgae076 (2024). [CrossRef]

- Dreyer, P., Roc, A., Pillette, L., Rimbert, S. & Lotte, F. A large EEG database with users’ profile information for motor imagery brain-computer interface research. Scientific Data. 10, 580 (2023). [CrossRef]

- Sartzetaki, C., Antoniadis, P., Antonopoulos, N., Gkinis, I., Krasoulis, A., Perdikis, S. & Pitsikalis, V. Beyond Within-Subject Performance: A Multi-Dataset Study of Fine-Tuning in the EEG Domain. 2023 IEEE International Conference On Systems, Man, And Cybernetics (SMC). pp. 4429-4435 (2023).

- Wimpff, M., Gizzi, L., Zerfowski, J. & Yang, B. EEG motor imagery decoding: A framework for comparative analysis with channel attention mechanisms. Journal Of Neural Engineering. (2024). [CrossRef]

- Wimpff, M., Zerfowski, J. & Yang, B. Towards calibration-free online EEG motor imagery decoding using Deep Learning. ESANN 2024 Proceedings (2024), accepted.

- Wu, D., Jiang, X. & Peng, R. Transfer learning for motor imagery based brain–computer interfaces: A tutorial. Neural Networks. 153 pp. 235-253 (2022). [CrossRef]

- Ko, W., Jeon, E., Jeong, S., Phyo, J. & Suk, H. A survey on deep learning-based short/zero-calibration approaches for EEG-based brain–computer interfaces. Frontiers In Human Neuroscience. 15 pp. 643386 (2021). [CrossRef]

- Kostas, D. & Rudzicz, F. Thinker invariance: enabling deep neural networks for BCI across more people. Journal Of Neural Engineering. 17, 056008 (2020). [CrossRef]

- Sultana, M., Reichert, C., Sweeney-Reed, C. & Perdikis, S. Towards Calibration-Less BCI-Based Rehabilitation. 2023 IEEE International Conference On Metrology For EXtended Reality, Artificial Intelligence And Neural Engineering (MetroXRAINE). pp. 11-16 (2023).

- Han, J., Wei, X. & Faisal, A. EEG decoding for datasets with heterogenous electrode configurations using transfer learning graph neural networks. Journal Of Neural Engineering. 20, 066027 (2023). [CrossRef]

- Jiménez-Guarneros, M. & Gómez-Gil, P. Custom Domain Adaptation: A new method for cross-subject, EEG-based cognitive load recognition. IEEE Signal Processing Letters. 27 pp. 750-754 (2020). [CrossRef]

- He, H. & Wu, D. Different set domain adaptation for brain-computer interfaces: A label alignment approach. IEEE Transactions On Neural Systems And Rehabilitation Engineering. 28, 1091-1108 (2020). [CrossRef]

- Han, J., Wei, X. & Faisal, A. EEG decoding for datasets with heterogenous electrode configurations using transfer learning graph neural networks. Journal Of Neural Engineering. 20, 066027 (2023). [CrossRef]

- Gu, X., Han, J., Yang, G. & Lo, B. Generalizable Movement Intention Recognition with Multiple Heterogeneous EEG Datasets. 2023 IEEE International Conference On Robotics And Automation (ICRA). pp. 9858-9864 (2023).

- Ju, C., Gao, D., Mane, R., Tan, B., Liu, Y. & Guan, C. Federated transfer learning for EEG signal classification. 2020 42nd Annual International Conference Of The IEEE Engineering In Medicine & Biology Society (EMBC). pp. 3040-3045 (2020).

- Mao, T., Li, C., Zhao, Y., Song, R. & Chen, X. Online test-time adaptation for patient-independent seizure prediction. IEEE Sensors Journal. (2023). [CrossRef]

- Wang, K., Yang, M., Li, C., Liu, A., Qian, R. & Chen, X. Privacy-Preserving Domain Adaptation for Intracranial EEG Classification via Information Maximization and Gaussian Mixture Model. IEEE Sensors Journal. (2023). [CrossRef]

- Xia, K., Deng, L., Duch, W. & Wu, D. Privacy-preserving domain adaptation for motor imagery-based brain-computer interfaces. IEEE Transactions On Biomedical Engineering. 69, 3365-3376 (2022). [CrossRef]

- Li, S., Wang, Z., Luo, H., Ding, L. & Wu, D. T-TIME: Test-time information maximization ensemble for plug-and-play BCIs. IEEE Transactions On Biomedical Engineering. (2023). [CrossRef]

- Wimpff, M., Döbler, M. & Yang, B. Calibration-free online test-time adaptation for electroencephalography motor imagery decoding. 2024 12th International Winter Conference On Brain-Computer Interface (BCI). pp. 1-6 (2024).

- Guetschel, P. & Tangermann, M. Transfer Learning between Motor Imagery Datasets using Deep Learning–Validation of Framework and Comparison of Datasets. ArXiv Preprint ArXiv:2311.16109. (2023).

- Ouahidi, Y., Gripon, V., Pasdeloup, B., Bouallegue, G., Farrugia, N. & Lioi, G. A Strong and Simple Deep Learning Baseline for BCI MI Decoding. ArXiv Preprint ArXiv:2309.07159. (2023).

- Xie, Y., Wang, K., Meng, J., Yue, J., Meng, L., Yi, W., Jung, T., Xu, M. & Ming, D. Cross-dataset transfer learning for motor imagery signal classification via multi-task learning and pre-training. Journal Of Neural Engineering. 20, 056037 (2023). [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y., Huang, X. & Lan, Q. Selective cross-subject transfer learning based on riemannian tangent space for motor imagery brain-computer interface. Frontiers In Neuroscience. 15 pp. 779231 (2021). [CrossRef]

- An, S., Kim, S., Chikontwe, P. & Park, S. Few-shot relation learning with attention for EEG-based motor imagery classification. 2020 IEEE/RSJ International Conference On Intelligent Robots And Systems (IROS). pp. 10933-10938 (2020).

- Junqueira, B., Aristimunha, B., Chevallier, S. & Camargo, R. A systematic evaluation of Euclidean alignment with deep learning for EEG decoding. Journal Of Neural Engineering. (2024). [CrossRef]

- Liu, S., Zhang, J., Wang, A., Wu, H., Zhao, Q. & Long, J. Subject adaptation convolutional neural network for EEG-based motor imagery classification. Journal Of Neural Engineering. 19, 066003 (2022). [CrossRef]

- Duan, T., Chauhan, M., Shaikh, M., Chu, J. & Srihari, S. Ultra Efficient Transfer Learning with Meta Update for Continuous EEG Classification Across Subjects.. Canadian Conference On AI. (2021). [CrossRef]

- Ouahidi, Y., Lioi, G., Farrugia, N., Pasdeloup, B. & Gripon, V. Unsupervised Adaptive Deep Learning Method For BCI Motor Imagery Decoding. ArXiv Preprint ArXiv:2403.15438. (2024).

- Xu, L., Ma, Z., Meng, J., Xu, M., Jung, T. & Ming, D. Improving transfer performance of deep learning with adaptive batch normalization for brain-computer interfaces. 2021 43rd Annual International Conference Of The IEEE Engineering In Medicine & Biology Society (EMBC). pp. 5800-5803 (2021).

- Gu, X., Han, J., Yang, G. & Lo, B. Generalizable Movement Intention Recognition with Multiple Heterogeneous EEG Datasets. 2023 IEEE International Conference On Robotics And Automation (ICRA). pp. 9858-9864 (2023).

- Bakas, S., Ludwig, S., Adamos, D., Laskaris, N., Panagakis, Y. & Zafeiriou, S. Latent Alignment with Deep Set EEG Decoders. ArXiv Preprint ArXiv:2311.17968. (2023).

- Zhuo, F., Zhang, X., Tang, F., Yu, Y. & Liu, L. Riemannian transfer learning based on log-Euclidean metric for EEG classification. Frontiers In Neuroscience. 18 pp. 1381572 (2024). [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W. & Wu, D. Manifold embedded knowledge transfer for brain-computer interfaces. IEEE Transactions On Neural Systems And Rehabilitation Engineering. 28, 1117-1127 (2020).

- He, H. & Wu, D. Transfer learning for brain–computer interfaces: A Euclidean space data alignment approach. IEEE Transactions On Biomedical Engineering. 67, 399-410 (2019).

- Xu, L., Xu, M., Ke, Y., An, X., Liu, S. & Ming, D. Cross-dataset variability problem in EEG decoding with deep learning. Frontiers In Human Neuroscience. 14 pp. 103 (2020). [CrossRef]

- Zoumpourlis, G. & Patras, I. Motor imagery decoding using ensemble curriculum learning and collaborative training. 2024 12th International Winter Conference On Brain-Computer Interface (BCI). pp. 1-8 (2024).

- Zanini, P., Congedo, M., Jutten, C., Said, S. & Berthoumieu, Y. Transfer learning: A Riemannian geometry framework with applications to brain–computer interfaces. IEEE Transactions On Biomedical Engineering. 65, 1107-1116 (2017). [CrossRef]

- Li, Y., Wang, N., Shi, J., Liu, J. & Hou, X. Revisiting batch normalization for practical domain adaptation. ArXiv Preprint ArXiv:1603.04779. (2016).

- Schneider, S., Rusak, E., Eck, L., Bringmann, O., Brendel, W. & Bethge, M. Improving robustness against common corruptions by covariate shift adaptation. Advances In Neural Information Processing Systems. 33 pp. 11539-11551 (2020).

- Döbler, M., Marsden, R. & Yang, B. Robust mean teacher for continual and gradual test-time adaptation. Proceedings Of The IEEE/CVF Conference On Computer Vision And Pattern Recognition. pp. 7704-7714 (2023).

- Marsden, R., Döbler, M. & Yang, B. Universal test-time adaptation through weight ensembling, diversity weighting, and prior correction. Proceedings Of The IEEE/CVF Winter Conference On Applications Of Computer Vision. pp. 2555-2565 (2024).

| Method | TAcc(%) | uTacc(%) | WAcc(%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| RiemannMDM (p<0.001) | |||

| BaseNet | |||

| RiemannMDM (p=0.065) | |||

| BaseNet |

| Method | TAcc(%) | uTacc(%) | WAcc(%) | |

| BaseNet | ||||

| supervised | RiemannMDM+PAR | |||

| BaseNet*** | ||||

| BaseNet+EA*** | ||||

| BaseNet+RA*** | ||||

| unsupervised | RiemannMDM | |||

| BaseNet+EA*** | ||||

| BaseNet+RA*** | ||||

| BaseNet+AdaBN** | ||||

| BaseNet+EA+AdaBN*** | ||||

| BaseNet+RA+AdaBN*** | ||||

| online | RiemannMDM+GR | |||

| BaseNet+EA* | ||||

| BaseNet+RA** | ||||

| BaseNet+AdaBN (p=0.125) | ||||

| BaseNet+EA+AdaBN** | ||||

| BaseNet+RA+AdaBN** |

| Method | TAcc(%) | uTacc(%) | WAcc(%) | |

| BaseNet | ||||

| supervised | RiemannMDM+PAR | |||

| BaseNet*** | ||||

| BaseNet+EA*** | ||||

| BaseNet+RA*** | ||||

| unsupervised | RiemannMDM | |||

| BaseNet+EA*** | ||||

| BaseNet+RA*** | ||||

| BaseNet+AdaBN*** | ||||

| BaseNet+EA+AdaBN*** | ||||

| BaseNet+RA+AdaBN*** | ||||

| online | RiemannMDM+GR | |||

| BaseNet+EA*** | ||||

| BaseNet+RA*** | ||||

| BaseNet+AdaBN* | ||||

| BaseNet+EA+AdaBN*** | ||||

| BaseNet+RA+AdaBN*** |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).