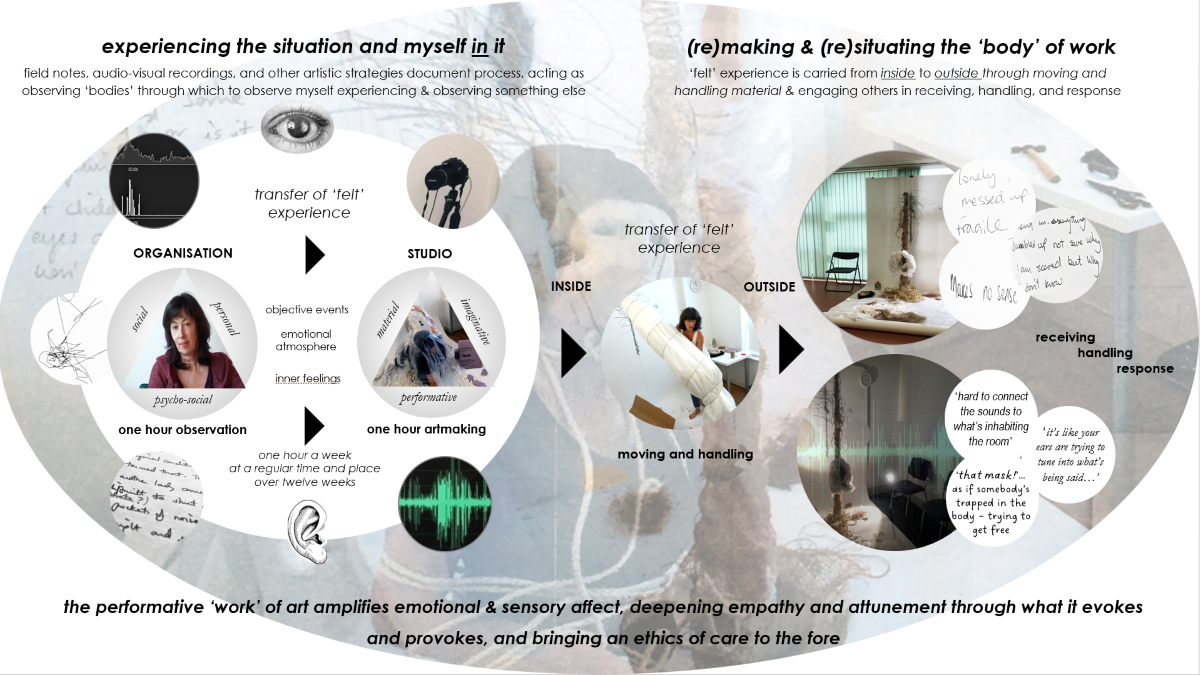

Twelve Weeks: Twelve Hours + Twelve Hours + 2

Practically, the project involves setting up a twelve-week observational placement and a separate private studio space in which I assemble a range of materials as well as audio-visual and other recording devices to document my process. Much like the psychotherapeutic setting, this is about establishing a safe, contained space, psychologically as much as physically (Townsend 2019). Following the psychoanalytic model, I attend the neurorehabilitation day service for one hour a week at a regular time over twelve consecutive weeks, on a day allocated for people living with the residual effects of stroke. With a wide range of hearing and vision, I sit in full view in the same place each week, on the edge of a communal area, at a time when service-users arrive, are settled, and attended to by nursing and support staff, and a range of healthcare professionals. I do not observe individual treatment processes which take place in private.

I adopt an attitude of ‘evenly suspended attention’ and open interest (Freud 2001 [1912]), without engaging directly with anyone except to respond sensitively and respectfully. More than observation as ‘just looking’, which suggests an objective distance (Walker 2016), I am concerned with experiencing the situation and myself in it; taking something from the outside inside and allowing the experience to inhabit, touch, and affect me. Indeed, during the first observation I am suddenly overcome with feelings of nausea and disorientation as, in what is a generally quiet setting apart from the TV, sounds and voices merge into one nonsensical noise.

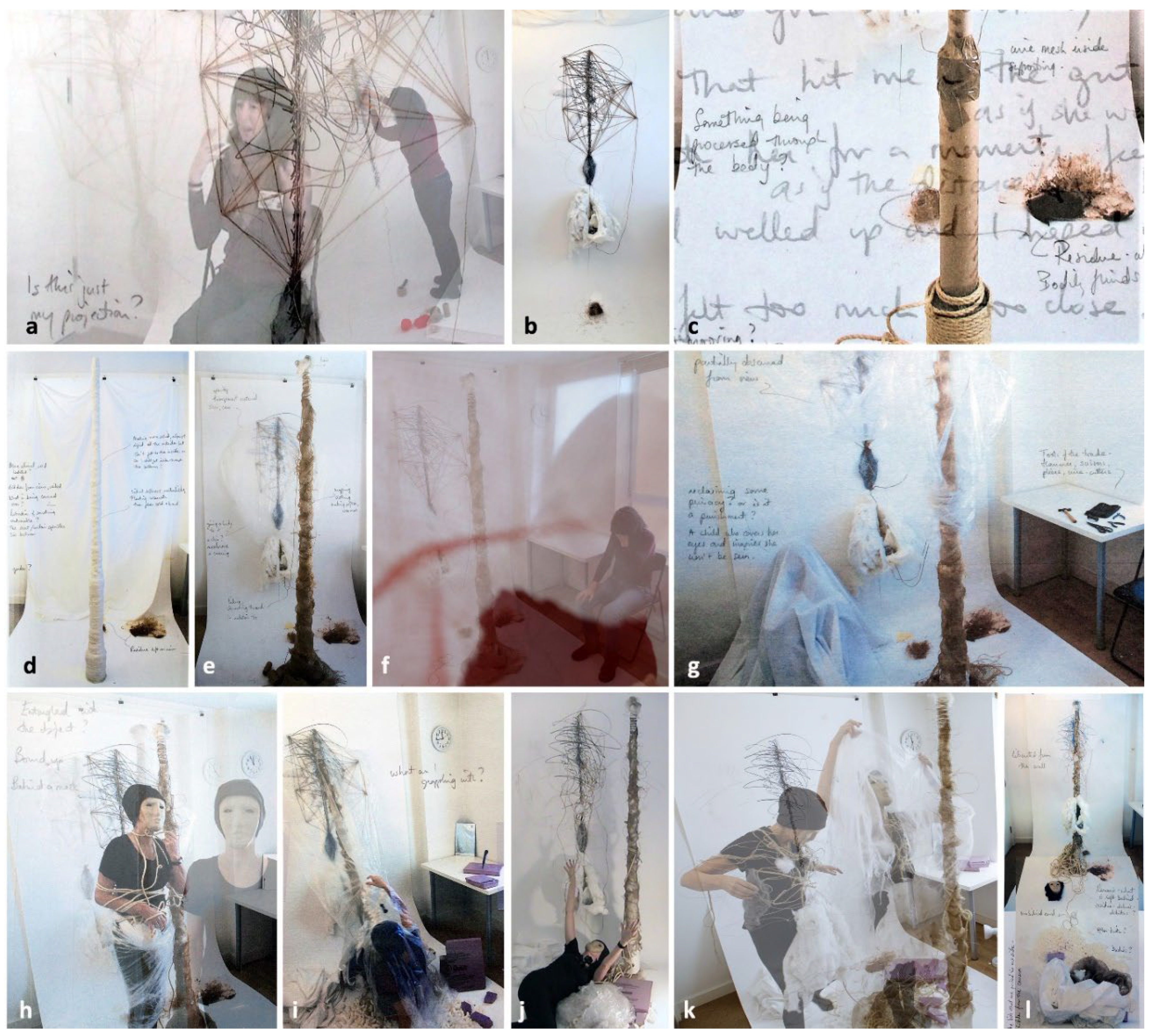

Each ‘observation’ in the organisation is then followed by one hour ‘making’ in the studio – an immediate transfer of ‘felt’ experience from one place to another. I have no plan other than to engage with the space and art materials on impulse, using whatever is to hand (Milner 2010 [1950]). Transferring my experience of the first observation to the studio, and feeling somewhat lost, I sit and talk to the cameras, as if they are witnesses to something I cannot repeat (

Figure 1a). When the words run out I turn to mark the paper backdrop with a graphite stick. This moves me into a less conscious, non-verbal, frame as drawing transitions to wire and string drawn across and between nails hammered into the wall, forming a tight network over the graphite scribble beneath which wire mesh hangs on a level with my gut. While the process brings associations to a spinal cord, networks of connections, ends trailing off, and ‘cotton wool brain’, it is only later that my use of a hammer takes on meaning through its resonance with ‘Homes under the Hammer’ playing on the ward TV, the impact of stroke, and the assault on my senses which disorientates and confuses.

Experiencing the Situation and Myself in It

The general atmosphere is warm, and friendly. Flurries of activity when service-users arrive and when they are collected for treatment contrast with quiet, sleepy periods when the pace is slow, chairs are empty, and nothing much seems to happen. Still, the intensity of experience surprises me as I continue to experience significant emotional and sensory disturbance including feelings of isolation, anxiety, sleepiness, sadness, and emotional disconnectedness, as well as powerful identifications and impulses to help or leave.

I do not plan to make a ‘body’ however the studio-based material insists with early associations to head, gut, and womb. In the studio after Observation III, I feel sick, as if there is something difficult to digest (

Figure 1b). The ethical responsibility of bearing witness to emotional vulnerability and pain weighs heavily as I imagine the ‘body’ – locked in and pinned to the studio wall – screaming at me to ‘let it go, set it free, take its constraints off’ (Michaels 2022:87)

3. Then, what it might mean to be imprisoned or locked in one’s body, as it might feel for some in the rehabilitation centre. ‘How difficult to judge the level of support a body might need, a physiotherapist explains to a service-user; if there is too much support the body may just collapse into it’ (pp. 87-88). During the following observation I watch another woman, partially paralysed and unable to produce words, become distressed in her helplessness as she struggles with her coat, only to be hushed by the man accompanying her. It is hard to witness. Shortly afterwards the sudden realisation that my name is shared with a relatively young woman close by hits me in the gut, momentarily collapsing the space between us (

Figure 1c). It is hard to contain the powerful emotion within which urges me to leave the room. Later, in the studio, I voice a concern about something getting lost – a memory.

I feel as if I’ve cut off from the intensity of this morning […] It’s almost as if I can’t talk about it […] It’s like I feel paralysed to do anything […] I just need to sit here with it (p. 84).

In the studio I construct a somewhat unstable structure that brings associations to a pipe, conduit, or transmitter, with various material residues reminiscent of bodily fluids. Then, by week V, I feel the constraints of the task tightening, as familiarity of routine sets in.

To say it fills me with dread is not quite right, but […] there is something really very difficult […] I couldn’t be here all day and maintain this level of connection with what I am feeling and, of course, if I was working here […]I’d be getting on with a different task (p. 95).

Observation V presents nothing notable, although my attention is caught again by a chair-raiser and I imagine the legs trying to break free from their constraints. In the studio, I wrap the unstable structure with plaster bandage to strengthen it (

Figure 1d). The repetitive gesture feels calming and comforting – ‘non-thinking’ – but fleeting thoughts of ‘limbless joints’ and ‘body parts’ seem at odds with the material that comes alive through the warmth it emits in its transformation from soft to hard, before turning cold. The following day, a disturbing emotional deadness overcomes me and I wonder if, through the repetition and routine, I enact something; if the method has merely become a protocol I follow each week.

[…] layers of protection around a vulnerable core. It makes it stronger – more rigid and stable – but I can’t get to the inside. The softer, more vulnerable parts are hidden, covered over. The overall picture […] appears more clinical – cold – lifeless (p. 96).

The deadened, numb feeling is not altogether unfamiliar through its echo with earlier traumas and personal losses, reminding me of the ease with which one might become anaesthetised to another’s pain as well as one’s own (Elkins 1996). Indeed, the repeating pull towards sleepiness and anaesthesia at the rehabilitation centre is, at times, reminiscent of ‘tiptoeing around a sleeping baby so as not to wake it’ (Michaels, 2022: 102). Yet, held in tension with the desire to ‘not feel’ is an ethics of attention and ‘attending to’ that brings matters of vulnerability, care, and responsibility to the fore. Perhaps the intensity of feeling and my desire to escape the situation is an identification both with the underlying trauma and loss suffered by those who attend the rehabilitation centre, and with staff who are confronted with the limits to what they can offer on a daily basis. A distraction from the situation perhaps, TV conversations relating to the ‘before’ and ‘after’ of house renovations, and whispered conversations at the nursing station concerning cosmetic surgery and makeovers seem to speak to a struggle to live with what is lost and cannot be recovered. Many who visit the rehabilitation centre face massive trauma and catastrophic change, affecting personality, identity, behaviour, and emotions as well as control over bodily function. While some new neural pathways may be formed after a stroke through repetition of movement, there is often a limit to the restoration and recovery of function. Something in the brain dies. But, as a service-user remarks, ‘is it better to have a body that doesn’t function properly or to “lose your marbles?”’ At the time she opts for the former.

The following week I continue with the task I have set myself, becoming involved in wrapping and covering the different parts of the body in the studio, as if giving it a skin. The tall, rigid, structure, now connected by a thread to the soft white mass suspended on the wall, develops hair at its top and wires reminiscent of feelers or antenna (Fig 1e). However, during observation VIII, and still working through the emotional turmoil after a challenging Ph.D. seminar, I feel ‘out of it – unable to hear properly or concentrate on fully being there’ (p.107). Responding to the ‘raw’ material I present at the seminar, a fellow researcher and healthcare practitioner remarks on the exposure of emotional vulnerability, commenting ‘I feel it’s things I’ve felt that I’d never dare say out loud’ (p. 113). Yet, the emotional content is quickly passed over in favour of artistic and professional critique, leaving me feeling acutely exposed and vulnerable, silenced, and under intense pressure to follow a different set of rules; a pressure I resist.

Returning my mind to the task, I observe a nearby conversation between a nurse and relative about the woman who sits between them, unable to speak, and am relieved when the woman is, once again, included through their attention. Still, in the studio I feel inhibited – stripped of a skin. I cover my face from the scrutiny of the cameras, then cover their lenses, working in silence although my actions are still audible (

Figure 1f). Uncovering the cameras later, I sit next to the ‘body’, now partially obscured beneath a polythene dressing. Covering myself with a white sheet I imagine a child who, in covering her eyes, believes she cannot be seen although, of course, she can (

Figure 1g). I am also being observed – caught in the gaze, not only of the documentary devices in the studio and the gaze of the academic institution, but also the service-users and staff in the neuro-rehabilitation centre, some of whom are curious about what I am doing, as I do not conform to a familiar role. Indeed, as one service-user remarks, I appear to be ‘doing’ nothing each week except watching the telly!

In the studio after observation IX, and catching an earlier thought about ‘becoming faceless’, I change clothes to those akin to a mime artist – all black with a mask. Unlike the previous week, I stand defiantly in front of the cameras with a blank stare before entangling myself with the ‘body’, unsure of the significance of what I am doing except that I feel ‘caught up in something’ (

Figure 1h). The following week, and feeling like an object, my mind turns to how we label and value people and things. I long for some human contact but there is none. In the studio I sit underneath a polythene sheet amidst seemingly worthless bits and pieces of material, hopelessly trying to thread something together that makes sense. What may once have been spoken in words has now become unintelligible noise – guttural expressions of rage at the senselessness of it all (

Figure 1i). There is something very difficult to articulate – to capture in words; the rage at what is lost and cannot be recovered resonates through my body along with the anger at having to adapt to different ways, and the ‘frustration with the body when it won’t do what you want it to’ (p. 120).

In Observation XI, I watch a staff member tidy up the magazines on the tables and my leaflets with them. Like the leaflets, I feel as if I have also disappeared from view – been absorbed into the organisational culture. Small changes catch my eye; different staff, things not where they were before, and empty spaces where people had been but are no longer. In the studio my hands lead my body in a gestural dance around the ‘body’, accompanied by my voice – at times thick and guttural, at others more akin to singing – evoking a mourning ritual (

Figure 1j). Reviewing the time-lapse video later, the photographs appear over-exposed for no apparent reason and I feel saturated – ‘at the limit of what I can absorb’ (p. 125).

The final observation feels like the death of something and I struggle to stay in the present. A nurse catches my eye, ‘I’m just saying why you’re here’. Moments later a student nurse approaches. ‘No-one seems to know what you are doing’ she says, listening intently as I explain that I am here to get the ‘feel’ of the place. I note an impulse to move my chair to create more distance between myself and whoever might arrive at the table nearby. Incidental marks on the floor draw my attention; seemingly insignificant, but there nonetheless. I feel as if I am watching a film while simultaneously being in the drama. As I prepare to leave, a television report considers the dilemma of when and how the life of a sick body is ended. It seems poignant. In the studio, I liberate the ‘body’ from the wall, entangling myself in its threads for the last time, before disentangling myself and attaching its threads to the tall pole-like thing to stand independently (Figs 1k & l). Writing up the session the following day I stop suddenly, feeling nauseous. It is a struggle to refocus on what has now passed, ‘as if a part of me wants to ‘forget – go to sleep […] but the work is not yet finished’ (p. 103).

(Re)making the ‘Body’ of Work 4

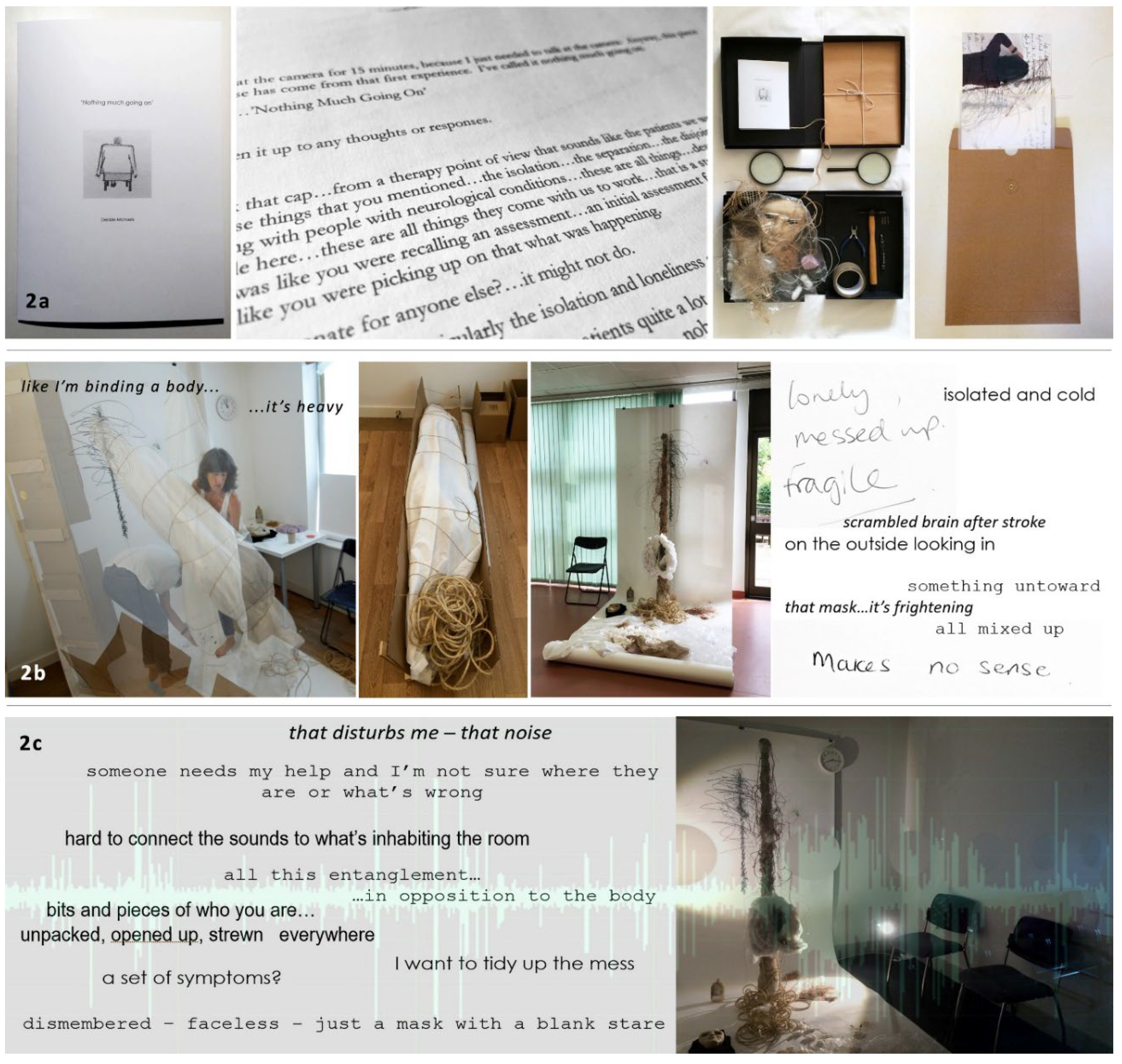

Some months later I invite the team at the rehabilitation service to respond to a piece of prose based on my experiences during the first observation (

Figure 2a).

5 Commenting on my references to feelings of isolation and disjointedness, one staff member remarks‘it was like you were recalling […] an initial assessment for treatment […] picking up on what was happening’ (p. 141). For another it resonates with those who have communication difficulties. ‘[…] they wish someone would talk to them but they don’t want to talk’ (ibid).

Then, an invitation to explore photographs of my studio process and various materials shifts the conversation to the emotional landscape.

A ‘[…] in order to survive and do our jobs we have to either – we feel it – but then we have to tuck it away somewhere […] because you have to keep doing your job, […] and you are perhaps witnessing some of the stuff that we have to deal with naturally every day.’

B ‘I suppose you like go into another mode – like acting.’

C ‘[…] you have to put on a brave face and carry on.’ (p. 145)

Later still, I move the residual ‘body’ of material out of the studio, resituating it in the place from where I had observed – a process that touches and moves me in unexpected ways through the care and attention it demands and the evocation of carrying a body in a shroud (

Figure 2b). Interrupting the normal flow of proceedings in the organisation I invite responses to its silent presence. Some ignore the ‘body’ while others tentatively share thoughts of ‘flotsam and jetsam’, and of a mask that is “frightening”, “something untoward”, “not nice”, and “doesn’t belong there”’ (p. 158). Anonymous written responses range from a ‘load of materials found on a beach or in a shed’, to ‘reaching out to something that is difficult to grasp’ (ibid). Reflecting on the installation in a subsequent focus group, staff share their struggle to understand the work which, for some, is ‘just a pile of materials’ (p. 160). Then, as I respond to their questions and speak again about the ‘making’ process and how it has ‘moved and continues to move’ me, the atmosphere in the meeting also moves. There is acknowledgement of the tendency to ‘react’ adversely when something is hard to understand, and several remark on how uncomfortable the mask or ‘face’ made them feel; it was hard to explain, but it felt ‘disconnected emotionally’ – ‘deathly’ (p. 161).

Although not made at the time, I would have struggled with the ethics of exposing people at the neuro-rehabilitation service to the-voice-of-its-making because of its disturbing resonance.

6 A soundtrack formed from twelve layered audio-recordings of my studio process, the sounds are hard to make sense of as, divorced from the original site of making, all structure and meaning disappears. Still, reworking the material reframes my original experience, amplifying it in the process. ‘It’s like your ears are trying to tune into what’s being said – to make sense of something’ one delegate remarks encountering the ‘body’ with ‘the-voice-of-its-making’ in a small room at a healthcare-related conference.

7 ‘It’s like somebody’s been tied up and left in a certain way, suffering, in distress – trying to escape a situation, to be set free from the body, but I don’t know where they are or what’s wrong’. Others speak of ‘dismemberment’ – just the ‘bits and pieces of who you are, unpacked, opened up, strewn everywhere’. The hands evoke ghostly associations, as if grasping at, or being called to ‘do’ something, while the mask brings thoughts of anonymity, the facelessness of some insitutions and the idea that, underneath the mask there is a ‘mangled mess’ (p. 176).