Submitted:

29 July 2024

Posted:

30 July 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Subjects

2.2. Variables

2.3. Statistical Methods

3. Results

| Characteristic | n = 67 ¹ |

|---|---|

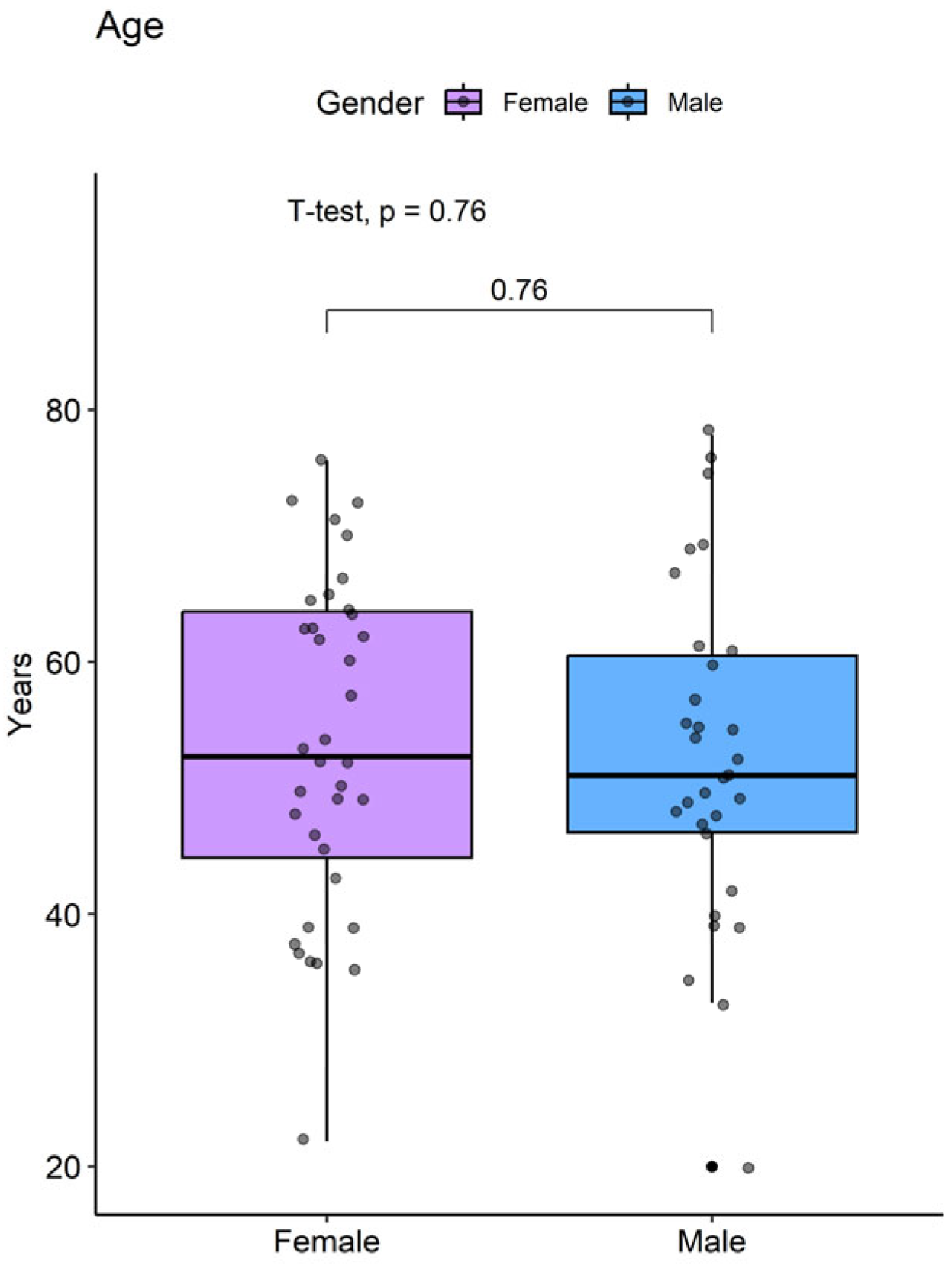

| Age | 53 ± 13 |

| Gender | |

| Female | 36 (54%) |

| Male | 31 (46%) |

| Occupation | |

| Merchant | 29 (43%) |

| Homemaker | 27 (40%) |

| Self-employed | 5 (7.5%) |

| Education | |

| Primary | 9 (13%) |

| Secondary | 37 (55%) |

| High School | 15 (22%) |

| Technical | 4 (6.0%) |

| Technological | 1 (1.5%) |

| University | 1 (1.5%) |

| Social Security | 35 (54%) |

| Regime | |

| Contributory | 32 (48%) |

| Subsidized | 3 (4.5%) |

3.1. Anthropometric Parameters and Pathological Background

3.2. Biochemical Profile

3.3. ASCVD ACC/AHA Cardiovascular Risk Profile and Renal Function

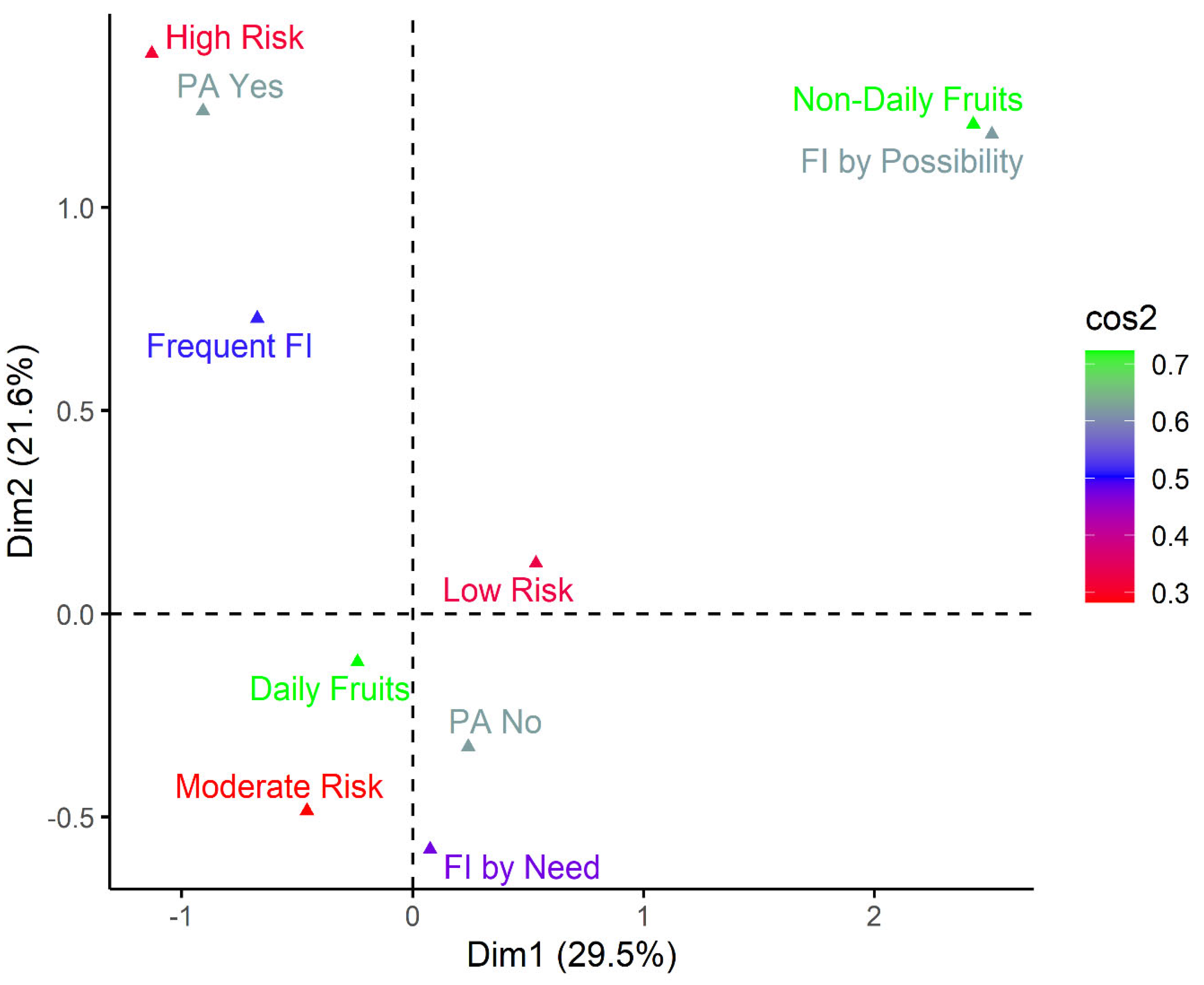

3.4. Lifestyle and ASCVD ACC/AHA Cardiovascular Risk Profile

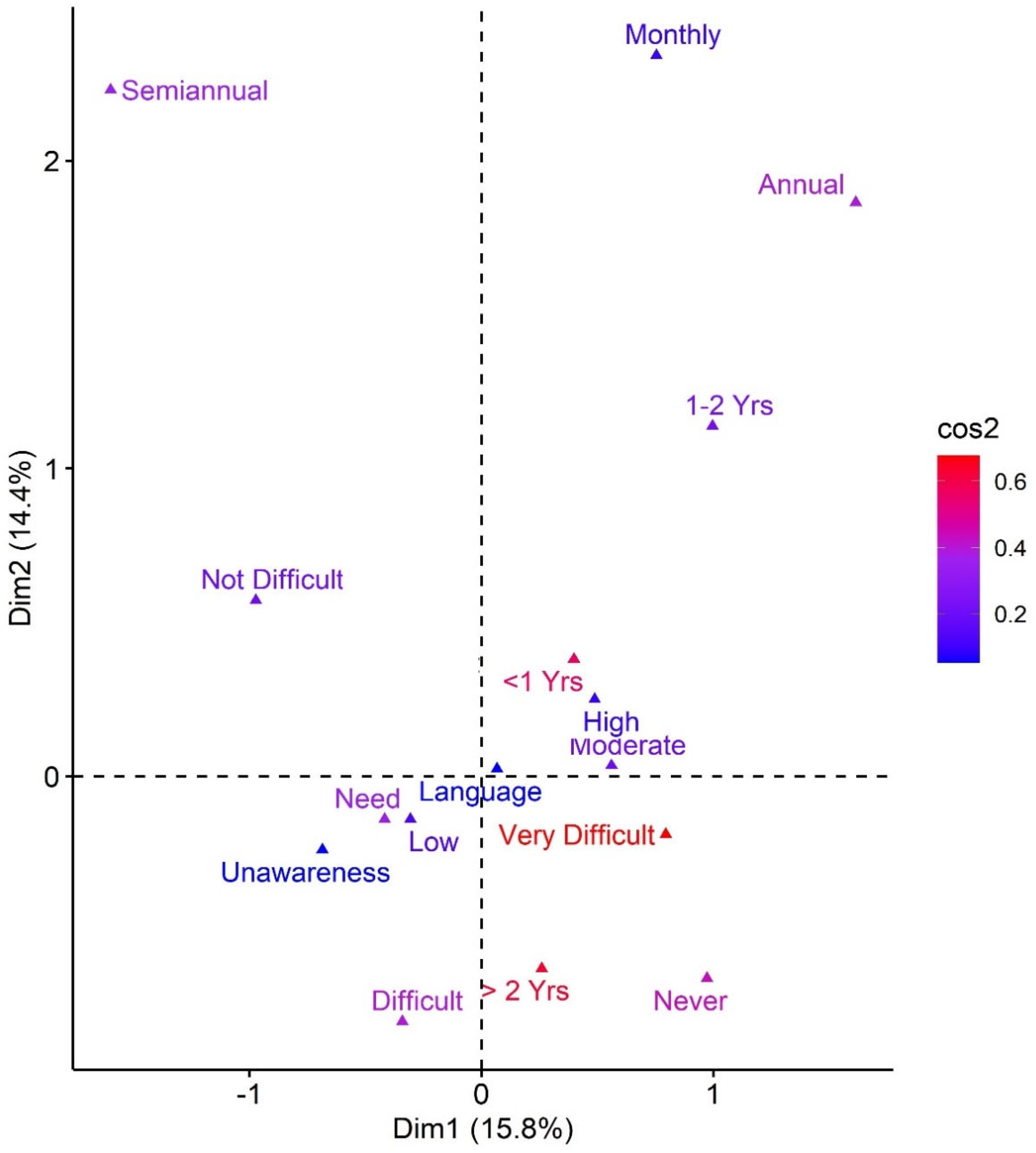

3.5. Medical Care Opportunity and ASCVD ACC/AHA Cardiovascular Risk Profile**

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Valbuena Ramírez, G.; Castellanos Caballero, E.; Cristancho Fajardo, C. East Asian Inmigration to Colombia: Chinese, Japanese, and South Korean Residents According to the 2018 National Population and Housing Census of Colombia, Universidad Externado de Colombia, 2021.

- Guerrero-Pinedo, F.; Ochoa-Zárate, L.; Salazar, C.J.; Carrillo-Gómez, D.C.; Paulo, M.; Flórez-Elvira, L.J.; Velasquez-Noreña, J.G. Association of Traditional Cardiovascular Risk Factors in Adults Younger than 55 Years with Coronary Heart Disease. Case-Control Study. SAGE open Med. 2020, 8, 2050312120932703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Wu, C.; Lu, J.; Chen, B.; Li, Y.; Yang, Y.; Hu, S.; Li, J. Cardiovascular Risk Factors in China: A Nationwide Population-Based Cohort Study. Lancet. Public Heal. 2020, 5, e672–e681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, A.L.; Le, A.D.; Li, Y.; Palaniappan, L.P.; Srinivasan, M.; Shah, N.S.; Wong, S.S.; Valero-Elizondo, J.; Elfassy, T.; Yang, E. Social Determinants of Cardiovascular Risk Factors Among Asian American Subgroups. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 2024, 13, e032509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clough, J.; Lee, S.; Chae, D.H. Barriers to Health Care among Asian Immigrants in the United States: A Traditional Review. J. Health Care Poor Underserved 2013, 24, 384–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lai, D.W.L.; Chau, S.B.Y. Predictors of Health Service Barriers for Older Chinese Immigrants in Canada. Health Soc. Work 2007, 32, 57–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gomez, D.A.; Diaz, L.M. Chinese Organizations in Colombia. Migr. y Desarro. 2016, 14, 75–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.-W. Status of Cardiovascular Disease in China. J. Geriatr. Cardiol. 2023, 20, 397–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sebastian, S.A.; Avanthika, C.; Jhaveri, S.; Carrera, K.G.; Camacho L, G.P.; Balasubramanian, R. The Risk of Cardiovascular Disease Among Immigrants in Canada. Cureus 2022, 14, e22300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodriguez-Alvarez, E.; Lanborena, N.; Borrell, L.N. Cardiovascular Disease Risk Factors in Spain: A Comparison of Native and Immigrant Populations. PLoS One 2020, 15, e0242740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sebastian, S.A.; Sethi, Y.; Padda, I.; Johal, G. Ethnic Disparities in the Burden of Cardiovascular Disease Among Immigrants in Canada. Curr. Probl. Cardiol. 2024, 49, 102059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García, J.L. China En Barranquilla. Memorias 2016, I–V. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badanta, B.; Vega-Escaño, J.; Barrientos-Trigo, S.; Tarriño-Concejero, L.; García-Carpintero Muñoz, M.Á.; González-Cano-Caballero, M.; Barbero-Radío, A.; De-Pedro-Jimenez, D.; Lucchetti, G.; de Diego-Cordero, R. Acculturation, Health Behaviors, and Social Relations among Chinese Immigrants Living in Spain. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazza, J.; Myers, M.; Orozco, M. Chinese Migration to Latin America and the Caribbean. 2016 Inter-American Dialogue 2016, 13. [Google Scholar]

- Gong, Z.; Zhao, D. Cardiovascular Diseases and Risk Factors among Chinese Immigrants. Intern. Emerg. Med. 2016, 11, 307–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koirala, B.; Turkson-Ocran, R.; Baptiste, D.; Koirala, B.; Francis, L.; Davidson, P.; Himmelfarb, C.D.; Commodore-Mensah, Y. Heterogeneity of Cardiovascular Disease Risk Factors Among Asian Immigrants: Insights From the 2010 to 2018 National Health Interview Survey. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 2021, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diaz, J.; Taboada, I.; Abreu, A.; Vargas, L.; Polanco, Y.; Zorrilla, A.; Beatty, N. Evaluating Rural Health Disparities in Colombia: Identifying Barriers and Strategies to Advancing Refugee Health. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 6948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roncancio, D.J.; Cutter, S.L.; Nardocci, A.C. Social Vulnerability in Colombia. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2020, 50, 101872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bustamante-matoma, H. Local Perspectives and Analysis of the Impact of Chinese Migration in Colombia. 2024, 15–41.

- Burnier, M.; Damianaki, A. Hypertension as Cardiovascular Risk Factor in Chronic Kidney Disease. Circ. Res. 2023, 132, 1050–1063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cipolla, M.J.; Liebeskind, D.S.; Chan, S.-L. The Importance of Comorbidities in Ischemic Stroke: Impact of Hypertension on the Cerebral Circulation. J. Cereb. Blood Flow Metab. 2018, 38, 2129–2149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jain, A.; Kumar, S.; Acharya, S.; Kabra, R.; Sawant, R. Assessment of Blood Pressure Variability in Postmenopausal Women. Cureus 2022, 14, e29471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Migneco, A.; Ojetti, V.; Covino, M.; Mettimano, M.; Montebelli, M.R.; Leone, A.; Specchia, L.; Gasbarrini, A.; Savi, L. Increased Blood Pressure Variability in Menopause. Eur. Rev. Med. Pharmacol. Sci. 2008, 12, 89–95. [Google Scholar]

- Mukamal, K.J. The Effects of Smoking and Drinking on Cardiovascular Disease and Risk Factors. Alcohol Res. Health 2006, 29, 199–202. [Google Scholar]

- Rosoff, D.B.; Davey Smith, G.; Mehta, N.; Clarke, T.-K.; Lohoff, F.W. Evaluating the Relationship between Alcohol Consumption, Tobacco Use, and Cardiovascular Disease: A Multivariable Mendelian Randomization Study. PLoS Med. 2020, 17, e1003410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pelucchi, C.; Gallus, S.; Garavello, W.; Bosetti, C.; La Vecchia, C. Cancer Risk Associated with Alcohol and Tobacco Use: Focus on Upper Aero-Digestive Tract and Liver. Alcohol Res. Health 2006, 29, 193–198. [Google Scholar]

- White, M.; Harland, J.O.; Bhopal, R.S.; Unwin, N.; Alberti, K.G. Smoking and Alcohol Consumption in a UK Chinese Population. Public Health 2001, 115, 62–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.X.; Zhao, Y.; Huang, L.X.; Xu, H.X.; Liu, X.Y.; Yang, J.J.; Zhang, P.J.; Zhang, Y.H. Effects of Smoking and Alcohol Consumption on Lipid Profile in Male Adults in Northwest Rural China. Public Health 2018, 157, 7–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagao, T.; Nogawa, K.; Sakata, K.; Morimoto, H.; Morita, K.; Watanabe, Y.; Suwazono, Y. Effects of Alcohol Consumption and Smoking on the Onset of Hypertension in a Long-Term Longitudinal Study in a Male Workers’ Cohort. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Todd, T.; Caroe, T. Newly Diagnosed Iron Deficiency Anaemia in a Premenopausal Woman. BMJ 2007, 334, 259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalasuramath, S.; S, V.C.; Kumar, M.; Ginnavaram, V.; Deshpande, D. V Impact of Anemia, Iron Deficiency on Physical and Cardio Respiratory Fitness among Young Working Women in India. Artic. Indian J. Basic Appl. Med. Res. 2015, 408–415. [Google Scholar]

- Liao, Q.; Chinese Children, P.W. & P.W.I.D.E.S.G. [Prevalence of Iron Deficiency in Pregnant and Premenopausal Women in China: A Nationwide Epidemiological Survey]. Zhonghua Xue Ye Xue Za Zhi 2004, 25, 653–657. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, W.; Xiao, J.; Yang, Z.; Ji, L.; Jia, W.; Weng, J.; Lu, J.; Shan, Z.; Liu, J.; Tian, H.; et al. Serum Lipids and Lipoproteins in Chinese Men and Women. Circulation 2012, 125, 2212–2221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Zhuang, Y.; Qiang, H.; Liu, X.; Xu, R.; Wu, Y. Relationship between Endogenous Estrogen Concentrations and Serum Cholesteryl Ester Transfer Protein Concentrations in Chinese Women. Clin. Chim. Acta 2001, 314, 77–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noronha, I.L.; Santa-Catharina, G.P.; Andrade, L.; Coelho, V.A.; Jacob-Filho, W.; Elias, R.M. Glomerular Filtration in the Aging Population. Front. Med. 2022, 9, 769329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, H.; Yan, Y.; Gong, J.; Dong, J. Prevalence of Kidney Damage in Chinese Elderly: A Large-Scale Population-Based Study. BMC Nephrol. 2019, 20, 341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodgers, J.L.; Jones, J.; Bolleddu, S.I.; Vanthenapalli, S.; Rodgers, L.E.; Shah, K.; Karia, K.; Panguluri, S.K. Cardiovascular Risks Associated with Gender and Aging. J. Cardiovasc. Dev. Dis. 2019, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, L.-Y.; Chen, W.-W.; Gao, R.-L.; Liu, L.-S.; Zhu, M.-L.; Wang, Y.-J.; Wu, Z.-S.; Li, H.-J.; Gu, D.-F.; Yang, Y.-J.; et al. China Cardiovascular Diseases Report 2018: An Updated Summary. J. Geriatr. Cardiol. 2020, 17, 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Li, C.; Carolino, E.; Sousa, J. Dietary Acculturation and Food Habit Changes among Chinese Immigrants in Portugal. Nutrients 2023, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mora, S.; Cook, N.; Buring, J.E.; Ridker, P.M.; Lee, I.-M. Physical Activity and Reduced Risk of Cardiovascular Events: Potential Mediating Mechanisms. Circulation 2007, 116, 2110–2118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alissa, E.M.; Ferns, G.A. Dietary Fruits and Vegetables and Cardiovascular Diseases Risk. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2017, 57, 1950–1962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noe-Bustamante, L.; Mora, L.; Ruiz, N.G. In Their Own Words: Asian Immigrants’ Experiences Navigating Language Barriers in the United States. Pew Res. Cent. 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Aparício, S.L.; Duarte, I.; Castro, L.; Nunes, R. Equity in the Access of Chinese Immigrants to Healthcare Services in Portugal. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Characteristic | Female (n=36) ¹ |

Male (n=31) ¹ |

p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Anthropometric | |||

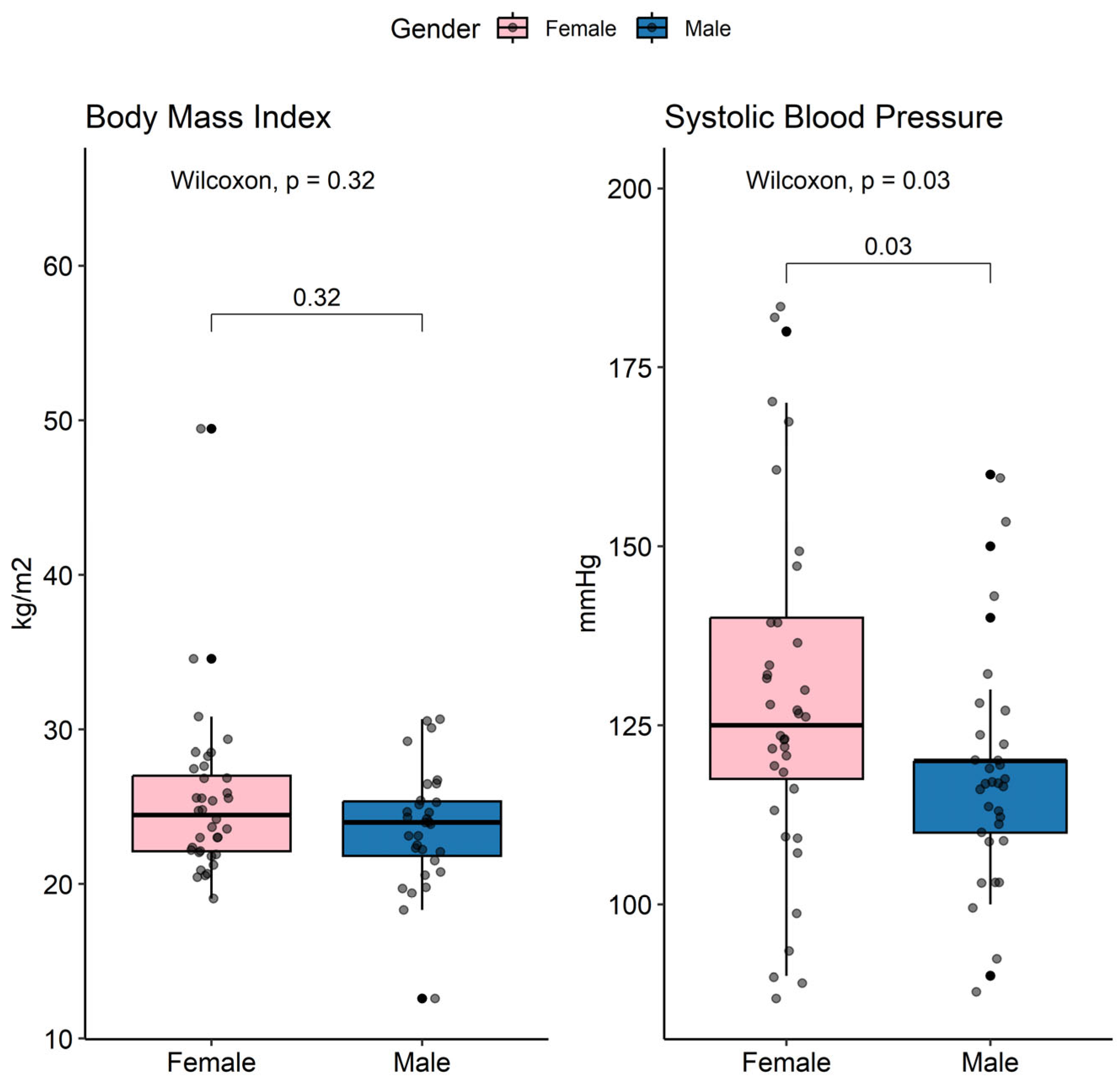

| BMI | 24.5 (19.1, 49.5) | 24.0 (12.6, 30.7) | 0.3 ² |

| BMI Status | 0.5 ³ | ||

| Normal | 18 (50%) | 19 (61%) | |

| Overweight | 15 (42%) | 9 (29%) | |

| Obesity | 3 (8.3%) | 3 (9.7%) | |

| SBP | 125 (90, 180) | 120 (90, 160) | 0.030 ² |

| DBP | 80 (60, 100) | 70 (60, 90) | 0.3 ² |

| Family History | |||

| Family HTN | 11 (33%) | 5 (17%) | 0.2 ³ |

| Family DM2 | 3 (9.7%) | 2 (6.9%) | >0.9 ³ |

| Comorbidities | |||

| Smoking | 0 (0%) | 16 (52%) | <0.001 ³ |

| Alcoholism | 1 (2.8%) | 11 (35%) | <0.001 ³ |

| HTN | 2 (5.6%) | 2 (6.5%) | >0.9 ³ |

| CAD | 0 (0%) | 1 (3.2%) | 0.5 ³ |

| AMI | 0 (0%) | 1 (3.2%) | 0.5 ³ |

| DM2 | 2 (5.6%) | 1 (3.2%) | >0.9 ³ |

| Dyslipidemia | 5 (14%) | 3 (9.7%) | 0.7 ³ |

| OSAHS | 1 (2.8%) | 0 (0%) | >0.9 ³ |

| COPD | 0 (0%) | 1 (3.2%) | 0.5 ³ |

| Lithiasis | 1 (2.8%) | 1 (3.2%) | >0.9 ³ |

| Neoplasia | 1 (2.8%) | 0 (0%) | >0.9 ³ |

| COVID-19 | 2 (5.6%) | 2 (6.5%) | >0.9 ³ |

| Surgical History | |||

| PCI | 0 (0%) | 1 (3.2%) | 0.5 ³ |

| Orthopedic Surgery | 2 (5.6%) | 1 (3.2%) | >0.9 ³ |

| Profile | Parameter | Female (n=36) ¹ |

Male (n=31) ¹ |

p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hemogram | Glucose | 90 (65, 333) | 91 (71, 337) | 0.2 ² |

| Hb (g/dl) | 13.1 (11, 15) | 15.4 (12.1, 18.2) | <0.001 ² | |

| WBC (×10³/µL) | 7,4 (4,7, 11,3) | 7,7 (4,9, 13) | 0.8 ² | |

| Platelets (×10³/µL) | 266 (160, 387) | 254 (135, 452) | 0.3 ² | |

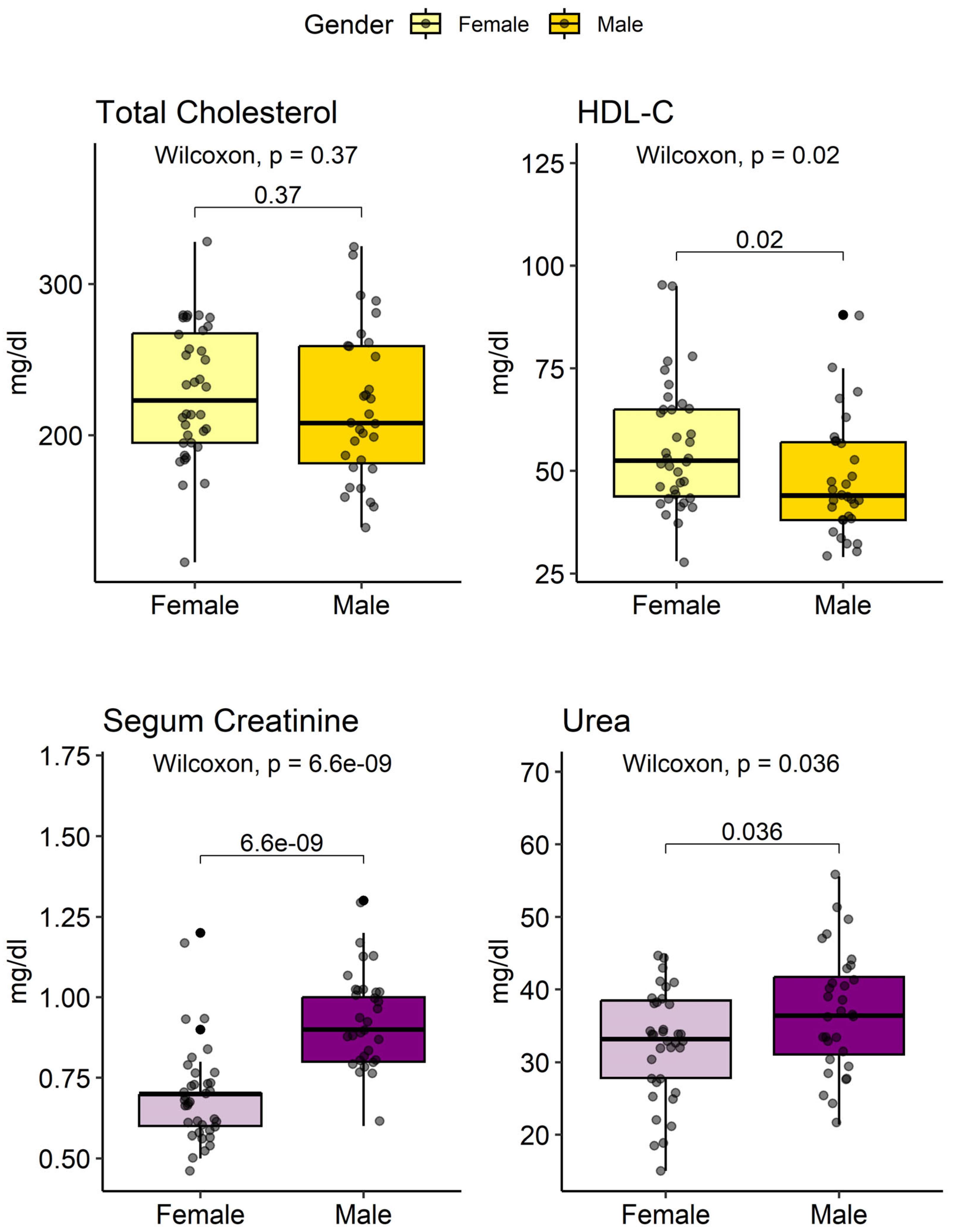

| Lipid Profile | TC (mg/dL) | 223 (116, 328) | 208 (139, 325) | 0.4 ² |

| HDL-C (mg/dL) | 53 (28, 95) | 44 (29, 88) | 0.02 ² | |

| TG (mg/dL) | 133 (44, 491) | 127 (51, 805) | 0.6 ² | |

| LDL-C (mg/dL) | 142 (53, 237) | 134 (66, 216) | 0.5 ² | |

|

Renal unction |

Cr (mg/dL) | 0.7 (0.5, 1.2) | 0.9 (0.6, 1.3) | <0.001 ² |

| eGFR (mL/min/1.73m2) | 96 (47, 147) | 93 (61, 146) | 0.2 ² | |

| BUN (mg/dL) | 15.5 (7, 21) | 17 (10, 26) | 0.036 ² | |

| Urea (mg/dL) | 33 (15, 45) | 36 (21, 56) | 0.036 ² |

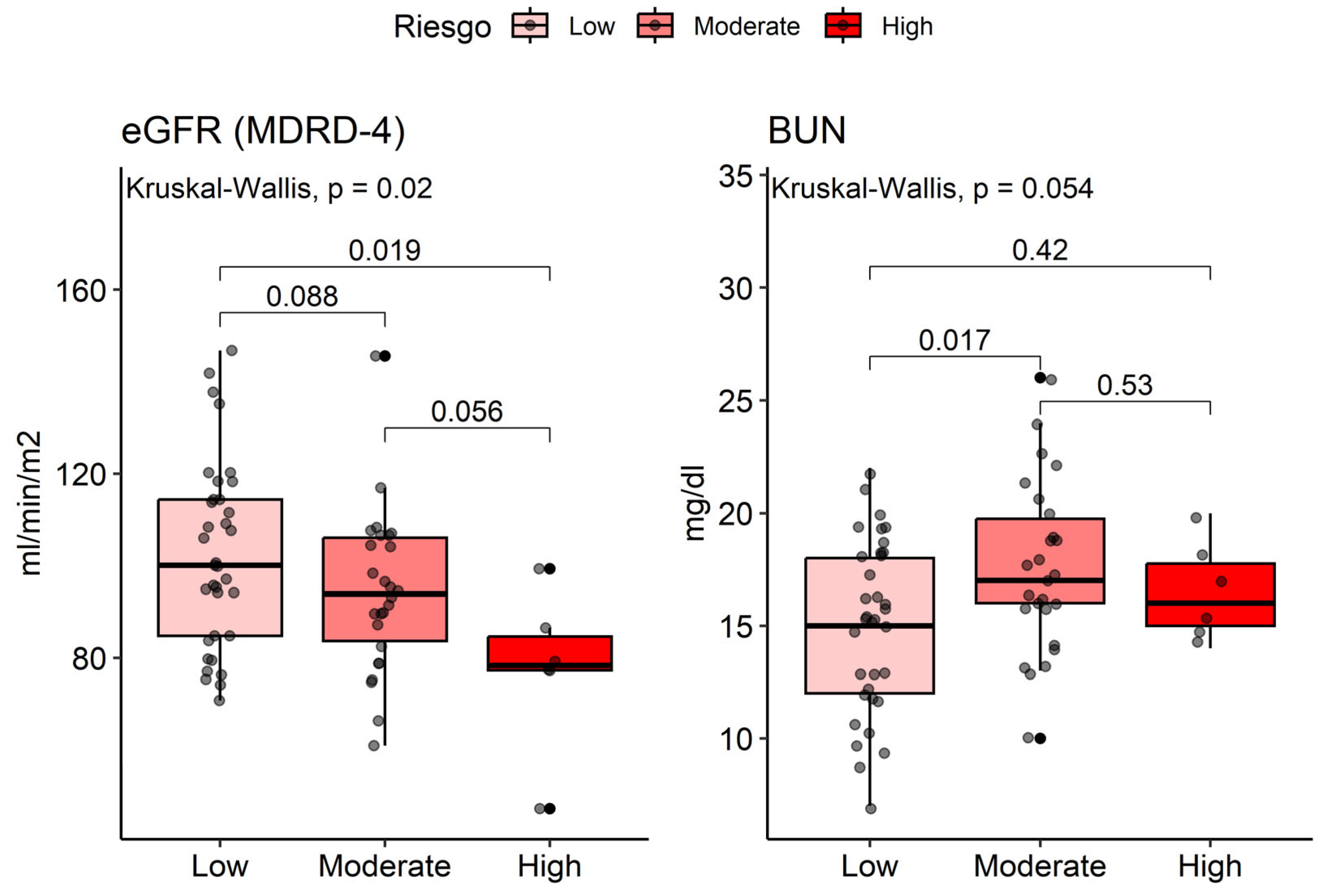

| Characteristic | ASCVD Risk | p-value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Low (n=35) ¹ |

Moderate (n=26) ¹ |

Alto (n=6) ¹ |

||

| Age | 48 (20, 67) | 61 (35, 73) | 76 (67, 78) | <0.001 ² |

| Gender | 0.040 ³ | |||

| Female | 24 (69%) | 10 (38%) | 2 (33%) | |

| Male | 11 (31%) | 16 (62%) | 4 (67%) | |

| Renal Function | ||||

| Cr (mg/dL) | 0.7 (0.5, 1.1) | 0.8 (0.6, 1.3) | 1.0 (0.7, 1.2) | 0.04 ² |

| eGFR (mL/min/1.73m2) | 100 (71, 147) | 94 (61, 146) | 78 (47, 99) | 0.02 ² |

| BUN (mg/dL) | 15 (7, 22) | 17 (10, 26) | 16 (14, 20) | 0.054 ² |

| Urea (mg/dL) | 32 (15, 47) | 36 (21, 56) | 34 (30, 43) | 0.06 ² |

| Urinalysis | ||||

| Proteinuria | 0 (0%) | 5 (14%) | 2 (7.7%) | 0.8 ³ |

| Hematuria | 0 (0%) | 10 (29%) | 8 (31%) | 0.4 ³ |

| ASCVD Score Risk (%) | 1 (1, 5) | 9 (5, 18) | 30 (20, 37) | <0.001 ² |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).