2.1. The Visible Hand

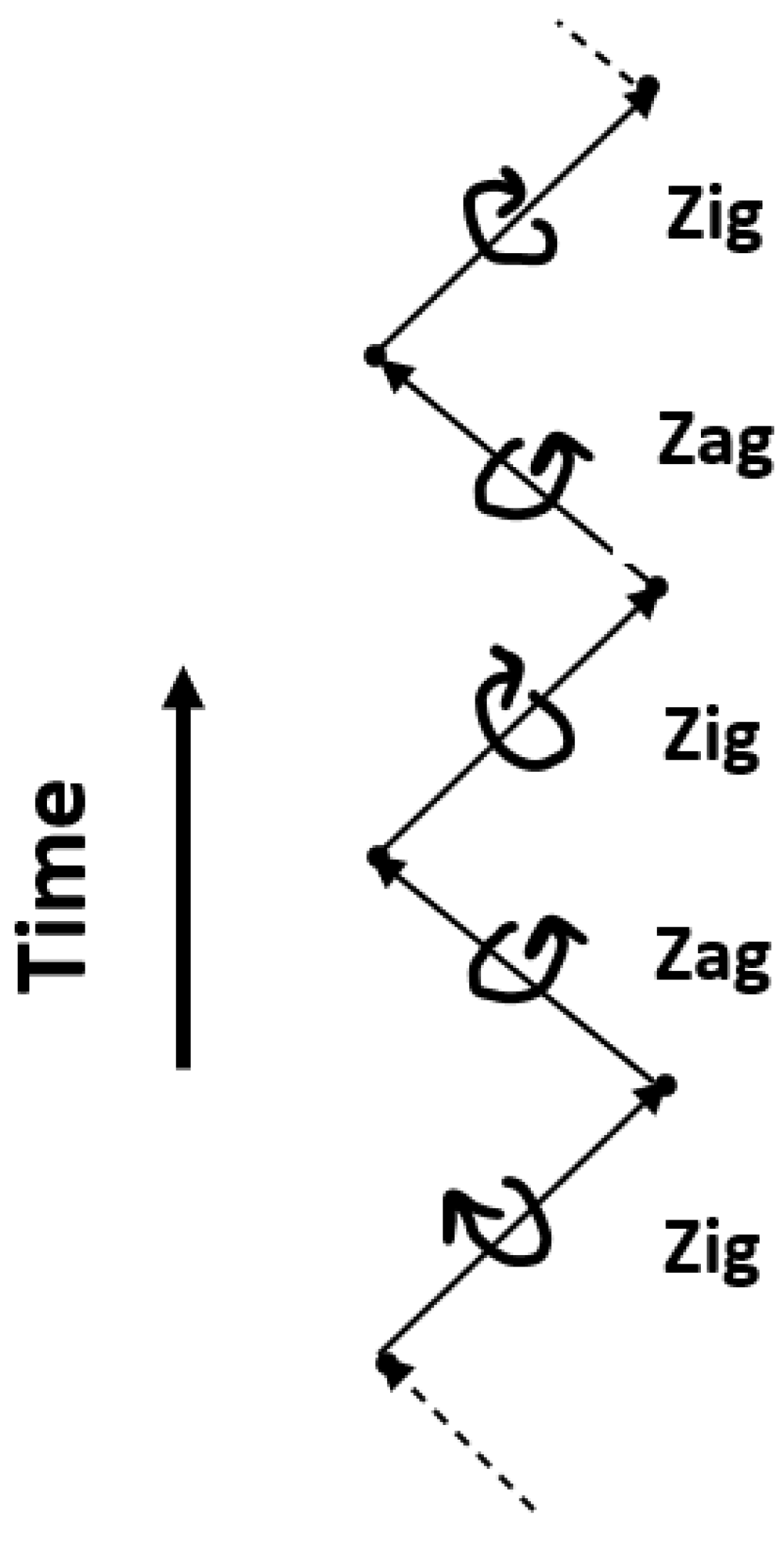

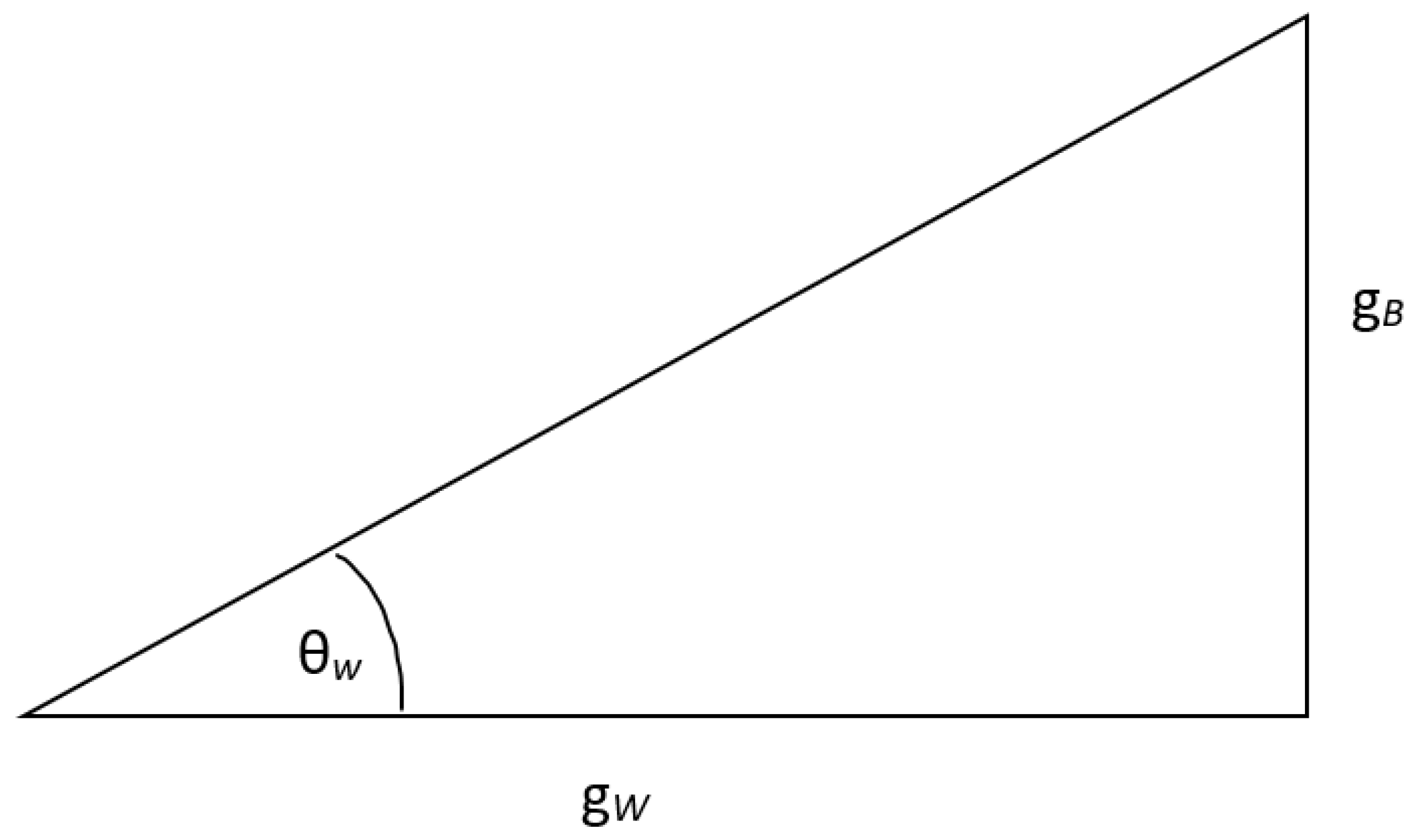

The financial market changes rapidly; speculators may go long or short, and retail investors may buy or sell at a moment's notice. At such times, accounts are active. Funds may be abundant in an account, yet action may be withheld temporarily. At these times, accounts are inactive. However, an investor can change states at any time, either pouncing like a tiger entering the fray or withdrawing after a successful surprise attack. These market behaviors are influenced by changes in participants' psychology, often affected by economic externalities, known as the visible hand. How can these phenomena be modeled, and what is the underlying mathematical structure? This article will illustrate that this visible hand can be described by weak forces in physics. Correspondingly, such moments of hesitation can be modeled by the isospin dynamics in the sub-physical standard model, with the underlying mathematical structure being SU(2) symmetry.

Capital has its weaknesses, leading to financial crises, so market regulation is essential, which is basic knowledge. Hayek advocated for completely free financial markets in his book "Denationalization of Money," but for a considerable period in history, this could only be a beautiful myth. In a previous discussion, we talked about four conditions for economic rationality, namely the four requirements for perfect competitive markets, where the fourth condition is market regulation, which is an economic externality.

More broadly, society interacts with capital, and the dynamic relationship between social fairness and profit-seeking capital is the domain of political economics, which cannot be avoided. Due to war, the economic downturn of the early 20th century gave rise to the Keynesian school of economics, advocating for state power to use economic policies (including monetary and fiscal policies) to intervene in the economy, commonly referred to as the visible hand. Two years after the 2007 global financial crisis, the situation did not improve. Princeton economist Krugman (Nobel laureate) once asked, if there really is an invisible hand, why hasn't it come out to help us yet? In fact, the invisible hand is always elusive and travels hand in hand with the visible hand. In economic life, controlling inflation, adjusting interest rates, issuing government bonds, stabilizing prices, redistributing income, providing healthcare insurance, and so forth—all require the visible hand to play a role, all require timely intervention of economic policies, and all cannot do without the involvement of economic externalities.

Clearly, the various economic externalities described above will affect market prices in different ways. At the microeconomic level, the visible hand affects people's price perception. At the meso-economic level, economic externalities affect the economic behaviors of market participants. At the macroeconomic level, economic policies affect dynamic changes on the supply side and the demand side. We will see that economic policies have their preferences for intervention.

2.2. Weak Forces and Flavor Isospin

In the previous discussion, it was mentioned that economic impulses are characterized by quarks in particle physics. Quarks have flavor isospin, such as up quark (u) and down quark (d). Economic impulses similarly have flavor isospin, namely achievement impulse and fear impulse, represented by up quark and down quark respectively, still denoted as u and d. From this, we have:

Proposition 1: Economic achievement impulse shares the same flavor isospin as the up quark, denoted as u.

Proposition 2: Economic fear impulse shares the same flavor isospin as the down quark, denoted as d.

Quantum chromodynamics tells us that quarks are confined and can only exist in bound states. Similarly, we can consider bound states of economic impulses. The proton-type impulse bound state consists of two achievement impulses and one fear impulse, denoted as uud. The neutron-type impulse bound state consists of two fear impulses and one achievement impulse, denoted as ddu. Hence, we have:

Proposition 3: The bound state composed of two economic achievement impulses and one economic fear impulse is called the proton-type impulse bound state, denoted as uud.

Proposition 4: The bound state composed of two economic fear impulses and one economic achievement impulse is called the neutron-type impulse bound state, denoted as ddu.

Heisenberg noted that these two bound states, proton uud and neutron ddu, apart from the flavor isospin of one quark being different, have the same components and binding mode, akin to twins with different names, and they can transform into each other. This is known as isospin, denoted by

Proposition 5: uud represents the proton-type impulse bound state dominated by achievement impulses with a secondary fear impulse, while ddu represents the neutron-type bound state dominated by fear impulses with a secondary achievement impulse. These two bound states form an isospin relationship, denoted as

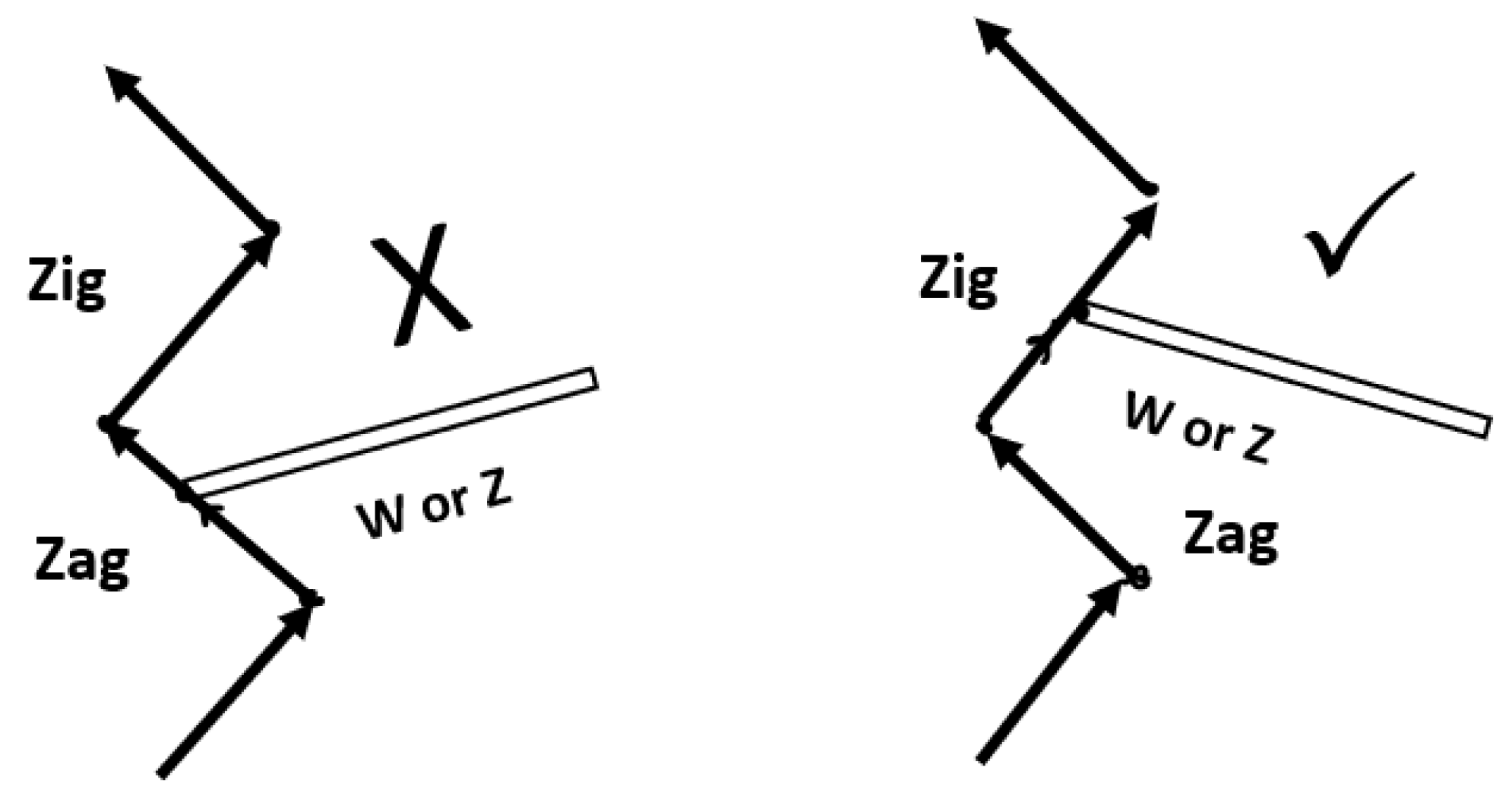

Isospin dynamics analysis involves sourced analysis, with the source termed weak isospin charge, denoted as . A neutron-type bound state, due to the action of weak forces, can decay into a proton-type bound state, i.e., ddu → uud. It can be seen, that due to the weak charge's action, we effectively have d → u, meaning weak forces change the quark's flavor isospin. Economic externalities can be described by weak forces; the reason being that economic externalities can change the flavor isospin of economic impulses, transforming a fear impulse into an achievement impulse. Hence:

Proposition 6:

Economic externalities are a form of economic weak force, denoted as . Economic weak force can act on economic impulses and change their flavor, expressed as : d→u.

Proposition 7:

Due to the action of economic weak force, economic impulses with different flavors form isospin, which is denoted by Dirac spinor

As we mentioned earlier [

1], quarks carry fractional electric charge. The upper quark carries

electric charge and the down quark carries

electric charge. It is not difficult to see that as a bound state, neutrons carry a zero charge, while protons carry an integer charge. In other words, considering the

market charge introduced in [

2] above, the neutron economic impulse bound state is price-neutral, containing zero market charge, and its market performance is conservative and onlooker. On the other hand, the proton type of economic impulse bound state carries an integer market charge, and its market performance is aggressive. We understand that one of the means of promoting economic development is to revitalize the market, and this is precisely the meaning of economic externalities (such as economic policies) affecting market prices. We can see from the isospin model that economic externalities stimulate market behavior (both consumption and supply) by changing the flavor of an economic impulse. It is a psychological mechanism by which an impulse of economic fear becomes an impulse of economic achievement.

2.3. Isospin of Market Charge and Residual Taste

Just as in chess, market behavior always leaves a residual flavor. Here, it is necessary to briefly review the concept of market charge introduced earlier. Since Marshall's "Principles of Economics" (1890), microeconomics has been able to articulate around three basic concepts: price, supply, and demand. A demand consists of two components, namely buying intentions and desired goods. We have:

Proposition 8:

Let the market price be denoted as . Demand is composed of purchasing intentions and target goods. Purchasing intentions carry a negative market charge, denoted as , and are fully sensitive to price . Similarly, supply consists of sales intentions and target goods. Sales intentions carry a positive market charge, denoted as , and are likewise fully sensitive to price .

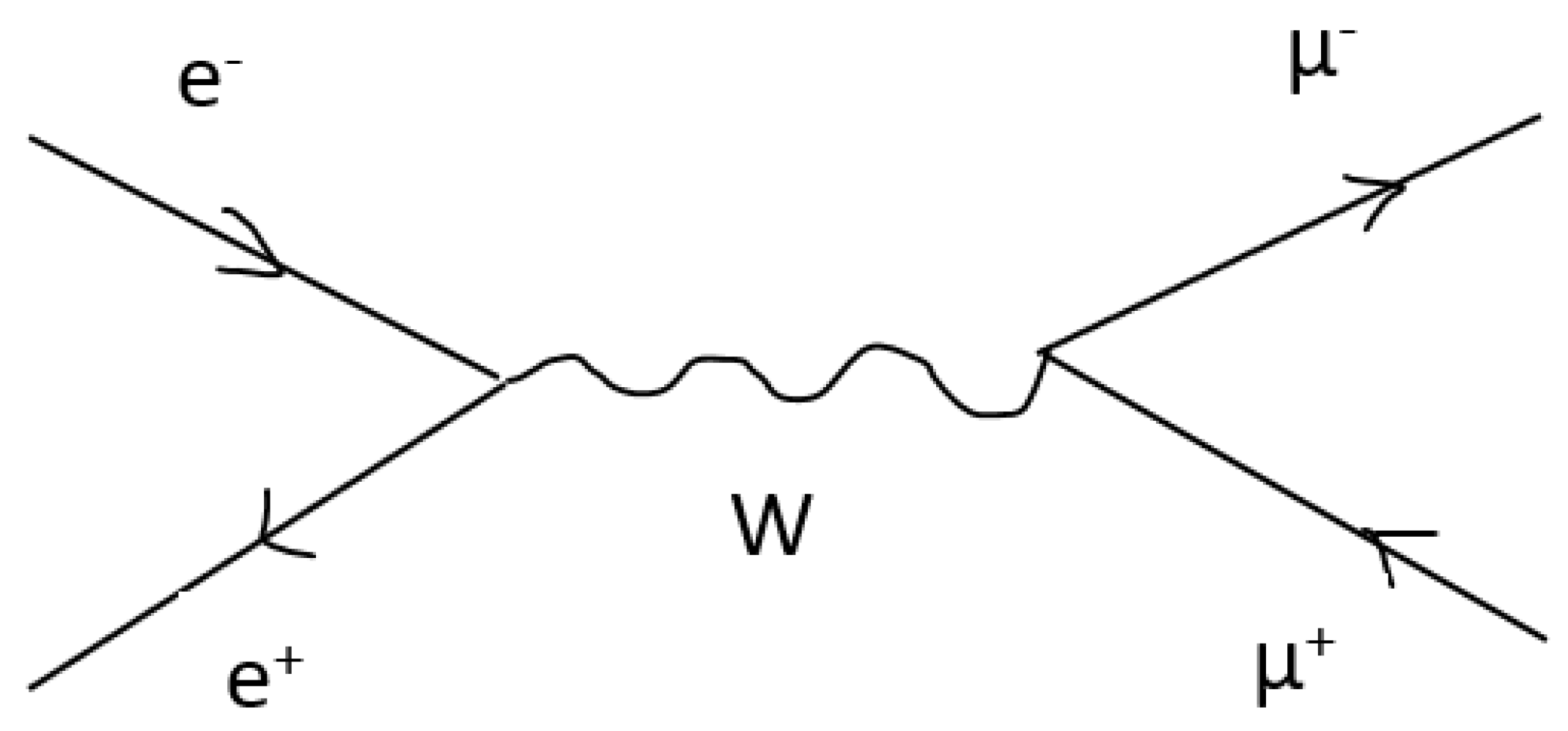

In market dynamics, positive and negative market charges are akin to positive and negative electric charges. A positron is the antiparticle of an electron. Assuming there is a price and a market, buying low and selling high is both economically rational and a natural inclination of market participants. Because buying and selling are always sensitive to price, whether to buy or not, to sell or not, market participants exhibit a hesitation phenomenon, referred to as spin. Spin hesitation is an intrinsic characteristic of market participants.

Engaging in buying and selling, discussing business, both parties have intentions to buy or sell, with shared goods goals. Based on individual buying and selling capabilities and market awareness, to facilitate market behavior, the bottom line is the negotiation of prices. Both buyers and sellers have the opportunity to trade, but not the obligation. Whether it's opening prices, inquiries, or negotiations, market participants have the right to hesitate, which is a fundamental principle of ordinary rationality.

In modern markets, in civilized society, it's common to buy rice and vegetables at supermarkets, or clothes, appliances, and daily necessities at shopping malls, as well as houses, cars, and various tickets like plane tickets, high-speed rail tickets, ballet tickets, or symphony concert tickets, all clearly priced. Payments can be made in cash, by card, or via transfer, with goods exchanged for money, accounts recognized and settled, and then both parties move on. Whatever psychological hesitation, cognitive thinking, reasoning, or decision-making occurred has already become the past. Money becomes a sunk cost. Traditional economics teaches us that economics is the study of efficiency, so forget about sunk costs. Assuming resources are scarce, economics itself seems only to study how to efficiently allocate scarce resources. Neoclassical economics warns us to follow the money and look forward. The so-called marginal analysis refers to whether investing an additional unit of scarce resources yields marginal income and marginal opportunity costs, each geometrically. If the former exceeds the latter, it is considered efficient, otherwise, it is considered inefficient. Here, "investing more" certainly looks forward. In terms of efficiency concepts alone, the corresponding mathematical concept is a derivative, and the corresponding physical concept is velocity.

However, from the perspective of economic psychology, do ordinary people completely refrain from contemplating after making a purchase? Did they get their money's worth? Today, if they happen upon a store promotion offering discounts (such as 30%, 50%, or even 70%), they might feel they made a good deal, experiencing some satisfaction, and may consider returning next time. Or, if they hear another store is selling the same item cheaper, they might feel they made a bad deal here and think not to return to this store next time. These are all remnants of market behavior. Although termed remnants, whether pondered deeply or lightly, they all involve mental effort and inevitably consume energy. Below, we will introduce how this consumer residue (likewise, supply residue) can be appropriately characterized by neutrinos from particle physics.

Economic externalities often play a significant role in creating market residue. For example, when the central bank adjusts interest rates, it has financial policy effects and even fiscal policy effects, impacting market prices. Persistent rate hikes can cause inflation, which in turn can lead to consumer dissatisfaction. This is a type of market residue, superficially seen as price residue, but deeper, it reflects policy residue.

Today, going out to refuel the car, after refueling, one can't help but sigh: gasoline prices have recently risen by nearly 30%. Maybe it's better to take public transportation from now on. This is demand-side consumer residue. Managing a farm, with intense competition, the fruits produced at home are increasingly difficult to sell at a good price. One can't help but think about switching to other productions. This is supply-side sales residue.

Weak interactions can change the flavor charge of quarks, causing a neutron to decay into a proton, i.e., ,

:

. In fact, this only tells half of the story. The complete story is formulated by the following interaction formula,

where the symbols denote electrons and electron neutrinos. Under weak interactions, electrons and electron neutrinos form another kind of isospin, denoted as

.

Neutrinos in physics and market residue in economics are remarkably similar. Firstly, both have very low energy, akin to residual energy. Therefore, neutrinos are called physical residues. Furthermore, market residue naturally pertains to buying and selling residue. Neutrinos are denoted as , and their footnote explains the close relationship between neutrinos and electrons. Additionally, neutrinos may or may not have mass, a topic still under debate in physics. As for market residue consequences, economics currently cannot confirm or deny them. Thus, both share a similar status in their respective fields. From this, we have:

Proposition 9.

In the dynamics of economic externalities, market residue is characterized by neutrinos, denoted as , where e represents market charge. Similar to the earlier discussion on the isospin of electrons and electron neutrinos, we have,

Proposition 10.

Under the influence of economic externalities, market charge and market residue form an isospin, still denoted as.

Neutrinos possess some unique properties. In gauge field theory, conventional mass concepts refer to Dirac mass, whereas neutrino mass refers to Majorana mass [

5]. Moreover, neutrinos are their own antiparticles. These characteristics provide speculative reference space for further research into market residue.