Introduction

Emerging in China in November 2019, coronavirus SARS-CoV-2 has provoked the first pandemic of the 21st century: COVID-19 (coronavirus disease 2019) has spread worldwide within a few months and still imposes an enormous burden on health systems and the economy. Transmission of the virions mainly occurs via droplet infection. Still, as they remain infective for up to 3 days, depending on the environmental conditions, they may also reach their hosts via everyday objects like computer keyboards, door handles, or furniture, finally entering cells of the oral or nasal mucosa or via the conjunctiva of the eye [1].

There is a wide variety in the clinical manifestation of COVID-19, ranging from symptomless infections through intermediate courses of the disease to life-threatening manifestations with severe pneumonia, multiorgan failure, and death. Both mild and severe forms of COVID-19 may also lead to so-called “Post Covid Syndrome (PCS)” a term used for various symptoms caused by the disease that continues for months after the initial infection [2].

Globally, mortality of the disease is about 3.4 % [3], reaching up to 4.3% in Wuhan (China), where COVID-19 has its origins [4]. Comorbidities, mainly hypertension and diabetes, are directly linked to poor disease outcomes [5]. As no effective treatment options against COVID-19 have been developed, only symptomatic approaches are used in managing this disease. Antiviral drugs examined so far have not yet revealed convincing clinical efficacy [6] or still need extensive investigation, such as ivermectin [7]. Most (80%) of symptomatic patients do not experience life-threatening manifestations of COVID-19. Still, moderate disease courses can quickly become severe, leading to acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) with multiorgan failure and death when no medical treatment occurs. Therefore, patients with moderate symptoms should also receive supportive treatment, including antiviral and/or antiphlogistic drugs, to prevent an aggravation of the disease. The treatment options under investigation include arbidol, chloroquine phosphate, ribavirin, favipiravir, ivermectin, interferon alpha-2b, and treatment with dexamethasone. Remedies with the plasma of convalescents or monoclonal antibodies like etesevimab and bamlanivimab are investigated for their safety and efficacy in COVID-19 patients [6,7]. However, as mentioned above, treatment is restricted to supportive and adjuvant care [9–11].

SARS-CoV-2 is comparable to the influenza virus in many respects, as both are RNA viruses that provoke respiratory symptoms ranging from very mild to highly severe forms that may result in a fatal course of the disease. Severe pathologies are often linked to overshooting reactions of the hosts’ immune system, mirrored by the so-called "cytokine storm." This phenomenon is known for pathogens like the influenza virus or the gram-negative bacterium Francisella tularens. It leads to pneumonia or hypercoagulation and is also observed in COVID-19 disease. Consequently, therapeutically suppressing the inflammatory immune response or the systemic use of active anticoagulants may represent promising approaches to managing COVID-19 symptoms [8].

Interestingly, it is not only the ARDS mentioned above that is associated with a poor outcome of the disease: in hospitalized COVID-19 patients, myocardial problems and kidney failure are observed that contribute to a fatal course of the disease [12–14]. However, the basic pathophysiological mechanisms of SARS-CoV-2 infections, which are responsible for the damage of the various tissue types, are not entirely understood yet [15]. Coagulation processes are essential in this context [16,17]. Still, a systematic description of the underlying coagulatory and fibrinolytic processes and their relationship to the outcome of the disease has yet to be accomplished [18,19]. Therefore, the exact mechanisms by which SARS-CoV-2 induces coagulatory and inflammatory responses and the interaction between these pathways during COVID-19 disease are unclear.

Generally, cessation and resolution of inflammatory processes depend on active strategies, which are largely driven by lipid mediator (LM) molecules, the specialized pro-resolving mediators (SPM) [20]. They are synthesized by cells of the innate immune system, which utilize the essential fatty acids arachidonic acid (ARA), eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA), n-3-docosapentaenoic acid (DPA), and docosahexaenoic acid (DHA) as substrates for enzymatic conversion to form four families of SPMs: lipoxins, resolvins, protectins and maresins [22,23]. All SPMs are involved in actively regulating and enforcing the resolution of inflammatory processes. Due to their action, for example, the amount of pro-inflammatory cytokines and chemokines is reduced at infected sites, and the influx of neutrophils is actively limited. Furthermore, macrophages are stimulated to enhance phagocytosis, killing bacteria and clearance of cell debris [20,22,23]. In animal disease models, an organ-protective action of SPMs has also been demonstrated [22]. Of particular interest in the present context is the observation that SPMs also seem to positively impact the alveolar fluid clearance (AFC) in ARDS, thereby supporting the reconstitution of the physiological function of the lung [24].

When lung tissue is injured, an immune response is triggered, which leads to an increase in the amount of pro-inflammatory molecules at the site of injury, followed by the entrance of immunocompetent cells into the alveolar space [25]. The influenza-A-virus demonstrated a direct correlation between its virulence and the profound and continuous induction of the inflammatory response.

Its ability to disseminate into different tissues was not only associated with strong activation of genes encoding for crucial elements of the pro-inflammatory cascade. Still, it was also accompanied by a down-regulation of genes responsible for the lipoxin-mediated anti-inflammatory signaling pathways, thereby reducing the pro-resolutive capacity and protective role of the SPM [26]. Also, for SARS-CoV-2 patients, a relationship between lipid mediator profile and severity of the disease has been demonstrated recently. Striking differences between the lipid profiles and the abundance of certain LM derivatives were observed between severe and moderate courses of illness. A relationship between pre-existing comorbidities like BMI, diabetes, heart disease and lipid profile changes has been described. It was speculated whether those risk factors led to a pre-existing imbalance in the LM profiles that might finally contribute to the severity of COVID-19 due to the decreased ability to counteract the inflammatory response induced by SARS-CoV-19 infection [27].

In most cases, COVID-19 patients feel better within a few days or weeks of the first symptoms’ appearance and fully recover within 12 weeks. However, for some people, symptoms can persist for weeks or months following the infection. The long-term effects of COVID-19 affect several body systems, including pulmonary, cardiovascular, and nervous systems, as well as psychological effects. These effects appear to occur irrespective of the initial severity of infection; even in mild or moderate cases, the disease can cause long-term organ damage but occurs more frequently in middle-aged women and those who initially show more symptoms (World Health Organization. 2021) [28].

Post Covid Syndrome, also known as long-term COVID, occurs in individuals with a history of probable or confirmed SARS-CoV-2 infection, usually three months from the onset of COVID-19. Symptoms last at least two months and cannot be explained by an alternative diagnosis. Symptoms may appear following initial recovery from an acute COVID-19 episode or the initial SARS-CoV-2 infection. Symptoms may also fluctuate or relapse over time [28].

An exacerbated inflammatory response is recognized as a central component in many chronic diseases, including vascular diseases, metabolic syndromes, and neurologic diseases. The acute inflammatory response can be divided into two different processes, initiation and resolution, a process that, for many years, was considered passive [29]. Only after the discovery of the first mediators with pro-resolution capabilities the processes that lead to the resolution of the acute inflammatory response begin to be considered as active once [30,31]. The anti-inflammatory properties of the Omega-3 fatty acids have been known for a long time. These fatty acids compete with the arachidonic acid, leading to lower levels of pro-inflammatory eicosanoids. During the resolution process, the Omega-3 fatty acids produce signaling molecules such as resolvins, protectins, and lipoxins, specialized pro-resolution mediators known as SPMs. These SPMs are agonists that shorten the resolution of the inflammatory response via the stimulation of resolution key events, stopping the flow of neutrophils, improving the elimination of the apoptotic cells and bacterial death [32–34].

The food supplement studied is enriched inmonohydroxylated SPMs. Previous studies have shown that it can raise SPMs in serum and plasma in various physiological and pathological circumstances. During inflammation caused by a trauma or an infection, there is a deficit of SPMs. The administration of this new formula could significantly improve the SPM levels in plasma and serum, as well as the ratio between the SPMs and inflammatory prostaglandins.

Previous studies used high doses of EPA and DHA [35] or this new formula [36]. The common grounds for all the studies were:

Considering the available data, the use of food supplements rich in Omega-3 fatty acids will not be related to the onset of adverse reactions, and the expected rise of SPMs will be associated with a clinical improvement in the symptoms of patients with PCS, which, in turn, could endorse the use of the supplement as an addition for the management of the disease.

The measurement of the plasma and serum concentrations of pro-inflammatory (prostaglandins and leukotrienes) and pro-resolving lipid mediators (lipoxins, resolvins, protectins, maresins, and monohydroxylated mediators derived from EPA and DHA) in patients with PCS, provided precious information about the immunological response of the patients regarding the inflammatory condition caused by the infection.

The study aimed at describing the immunological capacity and inflammatory response of this supplement on PCS patients on the lipidome level and on the clinical entities dyspnea and fatigue compared to healthy individuals by establishing profiles of the LM and their precursor molecules in plasma and serum of the test groups and analyzing the clinical devolvement of the patients.

Material and Methods

The study was designed as a randomized, double-blind, with four parallel supplement groups and a placebo-controlled trial to assess the efficacy of a food supplement enriched in SPMs in patients with PCS. The measurements included the pro-inflammatory and pro-resolution lipid mediators’ levels and the perceived fatigue and dyspnoea measured through subjective questionnaires. The safety and tolerability of the investigational product (IP) was also evaluated.

The study was planned as a proof of concept; it is a pilot study that aimed to determine the effect of increasing food supplement doses. Two different amounts of the supplement were tested and controlled with a placebo. An additional low-dose group was added, independent of the other 2, that was not regulated with the same objectives, to test the supplement’s effect on the levels of pro-inflammatory and pro-resolving lipid mediators.

Patients who were willing to participate signed the informed consent (IC) form, fulfilled all the inclusion criteria (and none of the exclusion criteria) were randomized to one of the four treatment options, 3 of which correspond to the double-blind placebo-controlled trial (A, B, C), and the fourth independent, non-controlled, low dose group (X).

No follow-up phase was planned after the study.

The following procedures were done during each visit of the study.

Screening visit – V0 (Day-7/Day-3)

Anamnesis and physical exam

Measure the body temperature, Blood pressure, and heart rate

Offer the participation in the study

Give oral and written information and obtain informed consent

Check the inclusion/exclusion criteria

Review the current concomitant medication

Randomization visit – V1 (Day1)

This visit took place between 3-7 days after the screening visit.

Check the inclusion/exclusion criteria

Physical exam

Measure the body temperature, Blood pressure, and heart rate

Blood sample

Pregnancy test (if applicable)

Fatigue Severity Scale (FSS) test

Modified Medical Research Council (mMRC) verificated Dyspnoea Scale

Randomization

Record of Adverse Events (AEs)

Concomitant medication

Record of intercurrent or concomitant illness

Provide the IP(s)

Provide the patient’s diary

Provide instructions about the completion of the diary

Interim visit – V2 (Day28±3):

Four weeks after the beginning of the treatment (± 3 days), the patients returned to the centreto attend the interim visit.

Physical exam

Measure the body temperature, Blood pressure, and heart rate

Blood sample

Fatigue Severity Scale (FSS) test

Modified Medical Research Council (mMRC) Dyspnea Scale

Record of Adverse Events (AEs)

Concomitant medication

Record of intercurrent or concomitant illness

Return of the empty and unused product containers

Patient’s diary review

Provide the IP(s)

End of Study visit - V3 (Day84±3)

Twelve weeks after the first administration of the IP, the patients returned to the centre for the final visit.

Physical exam

Measure the body temperature, Blood pressure, and heart rate

Blood sample

Fatigue Severity Scale (FSS) test

Modified Medical Research Council (mMRC) Dyspnea Scale

Record of Adverse Events (AEs)

Concomitant medication

Record of intercurrent or concomitant illness

Return of the empty and unused product containers

Patient’s diary review

Study Population

The study was conducted in 53 adult patients with PCS. The subjects included must have had a positive COVID-19 test (PCR, fast antigen test, or serologic test) and persistent symptoms related to COVID-19 at least 12 weeks before their enrolment in the study. The candidates were selected by the centres directly among the patients that were treated in each canter. The centres informed the potential candidates about the survey and offered them to participate.

No study procedure was conducted before the patient gave written consent, including their signature, name, and surname. The investigation team member providing the information on the study had to sign the informed consent sheet, too.

The trial protocol was designed and conducted following the ethical principles defined in the Declaration of Helsinki, and all procedures were consistent with GCP and the applicable regulatory rules.

Supplement Allocation

The IP was a food supplement enriched in SPMs, formulated as capsules. Each softgel contained 500 mg of a marine lipid fraction (Lipinova®), standardized to 17-HDHA, 14-HDHA and 18-HEPE (manufactured by Solutex GC SL; Spain). Both the investigational product and the placebo were manufactured, packed, and labelled by Laboratorios Liconsa SL; Spain).

The study’s sponsor provided all the investigational products adequately masked, except for group X, who were not blinded and, thus, not masked.

The treatment allocation was made by randomly assigning each subject to the treatment or placebo group. The randomization ratio was 3:3:1:3 [16/16/5/16])

The dosage was the following:

Group A = 3000 mg/day

Group B = 1500 mg/day

Group C = placebo

Group X = 500 mg/day

Ethical approval

The ethical committee approved the investigational trial and centres: Comité de Ética de la Investigación Santiago-Lugo with the number 2012/097.

Clinical Trial Registry: ISRCTN13270662

Primary Endpoint

Blood samples from PCS patients

Analytical Procedure

Blood samples were drawn on three days, each treated as a mono-replicate. They were separated into plasma and serum, subjected to standard preparation procedures, and stored at -80°C until further analytical processing. All samples were analysed individually, and the results were used for statistical analysis (see chapter below).

Extraction and profiling of lipids and lipid mediators by LC-MS/MS

In this study, the lipid mediator laboratory analyses were conducted at Solutex GC SL (for methodology see ref (PMID: 38003333). In brief, the extraction of lipid mediators from plasma and serum samples involved a solid phase extraction (SPE) process. Plasma or serum samples were mixed with internally deuterium-labeled standard solutions at 500pg, enabling quantification of analytes. After protein removal through precipitation and centrifugation, SPE was performed using established protocols. Following elution from the SPE column using organic solvents, extracts were dried and resuspended before injection into an LC-MS/MS system.

The LC-MS/MS system employed a Qtrap 5500 (Sciex) equipped with a Shimadzu LC-20AD HPLC pump. A Kinetex Core-Shell LC-18 column was utilized with a binary eluent system. The elution gradient program and flow rate were carefully controlled. Negative ionization mode and scheduled Multiple Reaction Monitoring (MRM) acquisition were used for analysis. Quantification was achieved by calculating the area under the peaks, and identification employing MS/MS matching signature ion fragments for each molecule using a library, as well as retention times for each lipid mediator compared to Internal standards. The study ensured optimization of lipid mediator parameters for accurate quantification.

Statistical Analysis

Arithmetic means, standard error, and minimum and maximum values were calculated and displayed for each patient and analyte. GraphPad Prism Software version 9.0.2 (San Diego, California, USA) was used for outlier exclusion with default parameters ROUT (Q=1%).

A ratio between pro-inflammatory and pro-resolutive parameters was calculated to establish a measure for the balance between the pro-inflammatory and pro-resolutive axes of the underlying physiological processes.

A one-tailed t-test was used for all statistical comparisons, and p-values below 0.05 were rated statistically significant as there was no adjustment for multiple testing. The data presented here is merely explorative and descriptive.

Analysed lipids and lipids mediators.

The following analytes were determined.

Polyunsaturated fatty acids: EPA, DHA, ARA, DPA.

Monohydroxylated SPMs: 17-HDHA, 18-HEPE, 14-HDHA.

SPMs: Resolvins (RvE1, RvD1, RvD2, RvD3, RvD4, RvD5), Maresins (MaR1, MaR2), Protectins (PD1, PDX), Lipoxins (LXA4, LXB4.

Pro-inflammatory eicosanoid lipid mediators: Prostaglandins (PGE2, PGD2, PGF2α.), Thromboxanes (TxB2), Leukotrienes (LTB4)

Secondary Endpoint

As a secondary efficacy objective, the evolution of the above-mentioned parameters until the fourth week of treatment (day 28) was calculated.

Other secondary efficacy variables are:

Fatigue Severity Scale (FSS) test: The FSS test measures fatigue on a unidimensional scale. It consists of 9 questions with seven possible answers, quantifying each item on a 1 to 7 scale. The evolution of the mean scores from baseline to visit 2 (4th week of treatment, day 28) and to the end of the study (day 84 of treatment) is calculated.

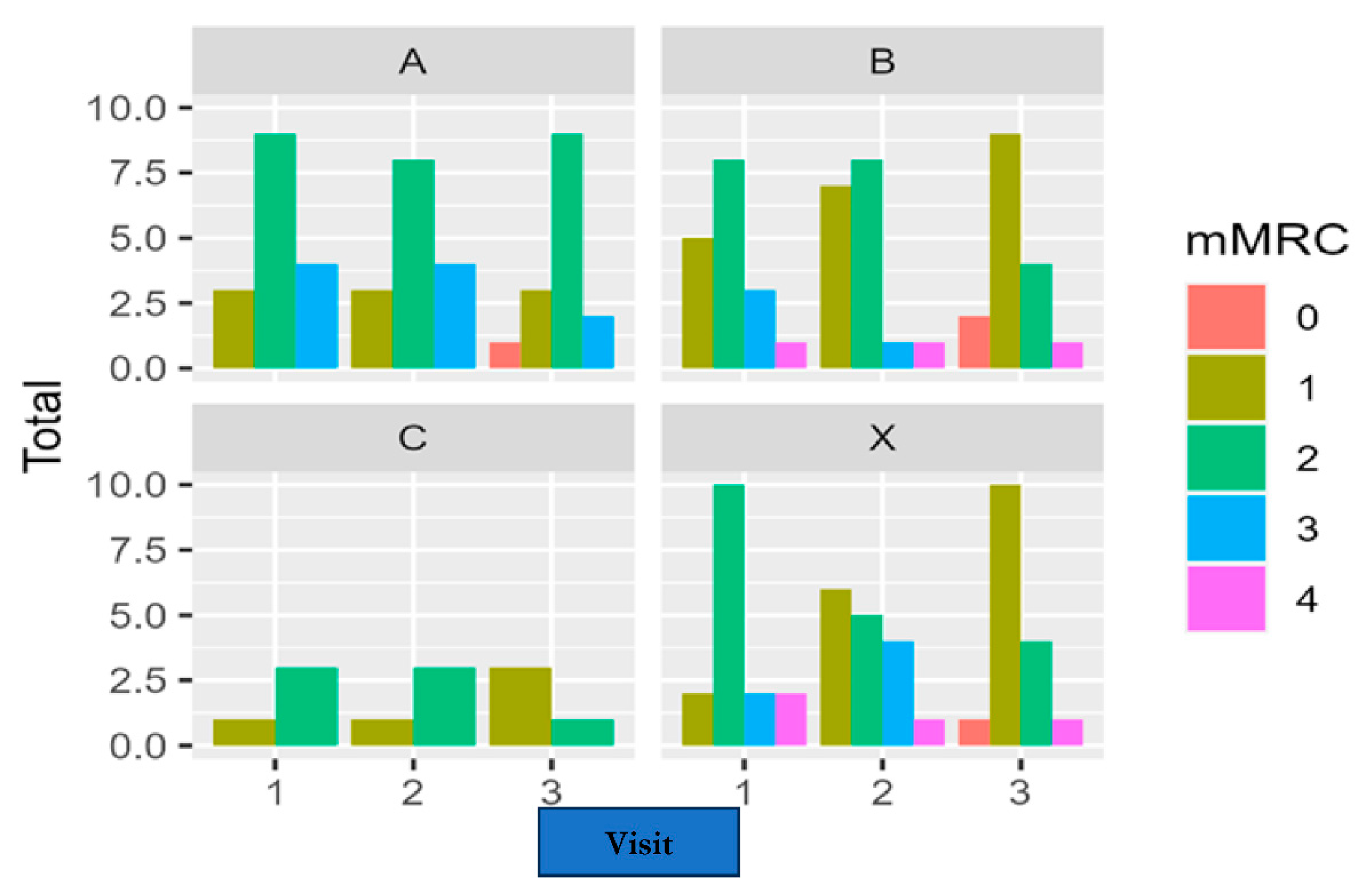

Modified Medical Research Council (mMRC) Dyspnea Scale: The scale includes 5 degrees of physical activity that could cause dyspnea. The scale punctuates the dyspnea from 0 (No exercise causes dyspnea) to 4 (the dyspnea prevents the patients from leaving the house or performing routine daily activities like dressing up. The baseline results are compared to the scores at visit 2 (day 28) and the end of the study (day 84).

Safety

To assess the safety of the IP, all Adverse Events (AEs) that occurred to the participants during the study, since the first administration of the IP up to the last visit (treatment-emergent AEs), were collected, assessed, and recorded in the CRF, regardless of their relationship to the study product. The events that would have begun before the supplementation were included in the subject’s clinical history.

The AEs could be clinically significant abnormalities found in the vital signs (body temperature, heart rate, or blood pressure) or during the physical exam or could be reported directly by the subjects to the investigators either during the visits or through their diaries. The investigators had to record the AEs in the CRF and assess their intensity, seriousness, and casual relationship with the IP using their best medical judgment and experience.

Results

Laboratory changes

In this observational study, we observe that the quantification of each parameter was detectable in the sera but not in the same way in the participants’ plasma.

This study aimed to quantify the Targeted SPM -Eicosanoid lipidomics in human plasma and serum profiles. We measured ARA, DHA, and the EPA metabolome using the "state of the art" targeted LC-MS/MS metabololipidomics after the intake of 3 different dosages of the marine oil enriched solution containing the daily dose of 500, 1500, or 3000 mg.

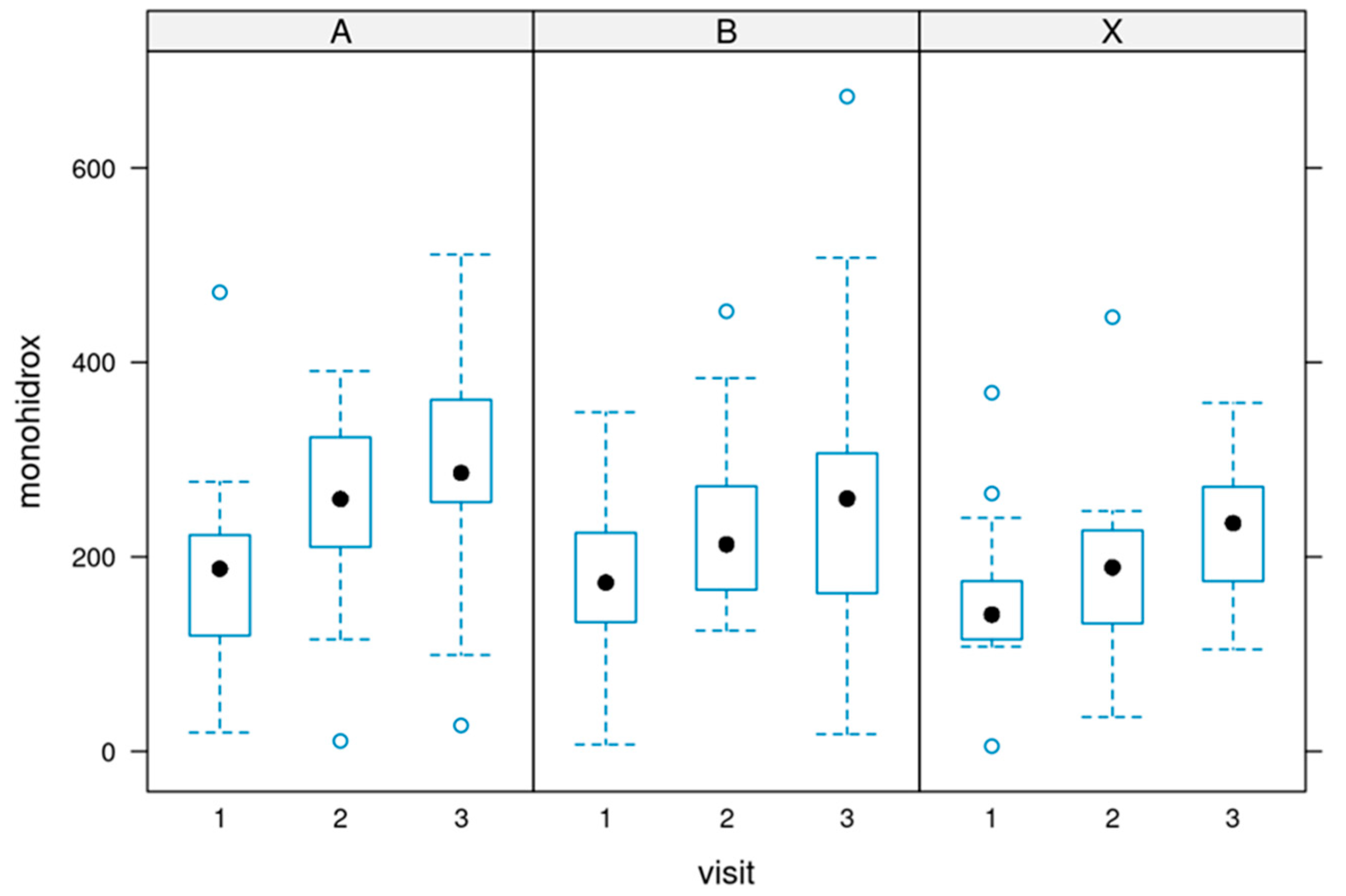

After quantitation, summation of total-derived pro-resolutive mediators resulted in a statistically significant increase (p<0.05) comparing each of the three metabolites: 14-HDHA + 17-HDHA + 18-HEPE [ng/ml] in the serum of the patients at all dosages.

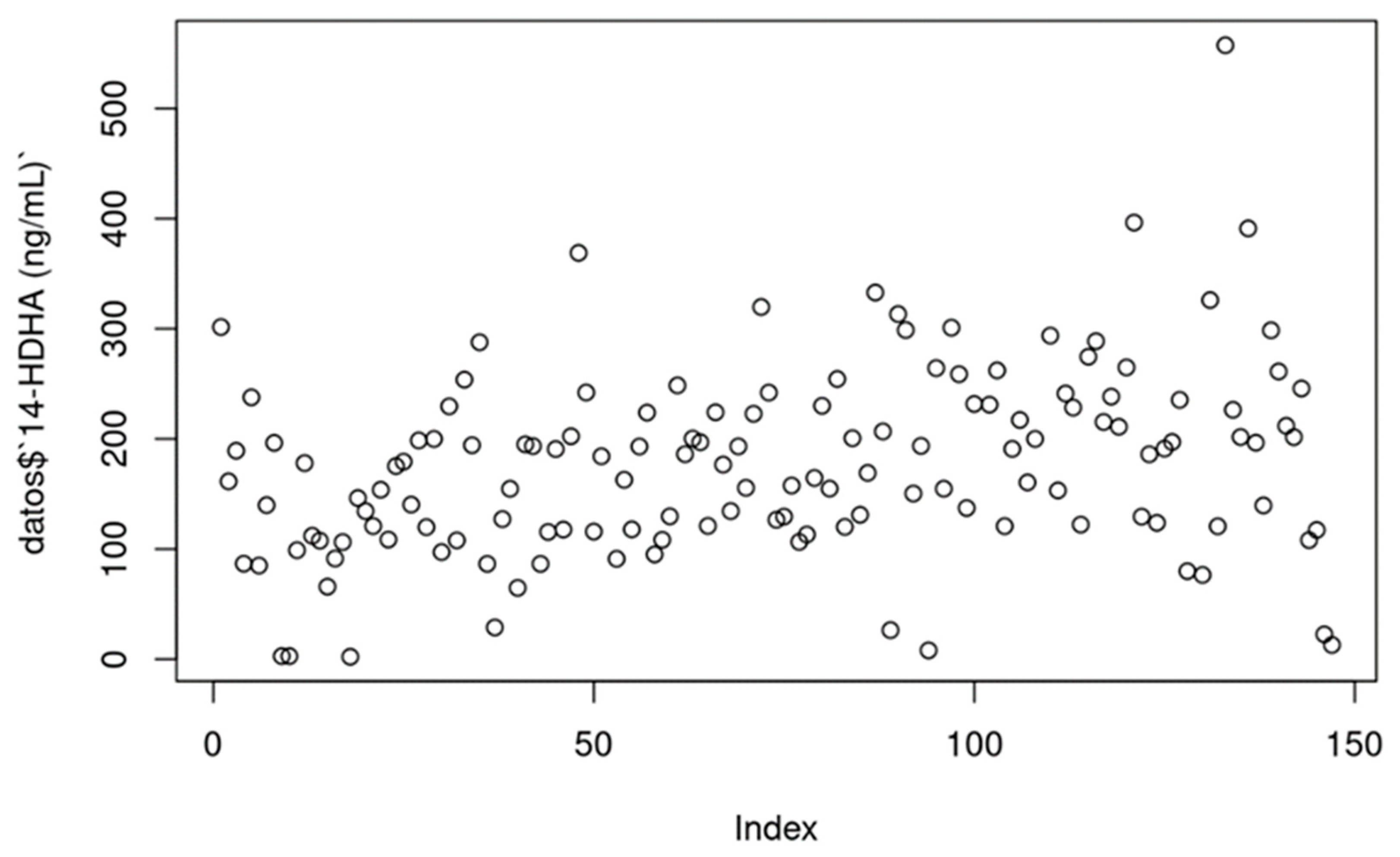

Values for 14-HDHA

14-HDHA [ng/ml]: Serum concentrations of 14-HDHA ranged from 0 to 300 ng/ml in most cases (treatments per week), with a few values above these numbers. The increase could be seen throughout the 12 weeks of use.

Figure 1 and

Figure 2 depict the values. P-value = 0.002.

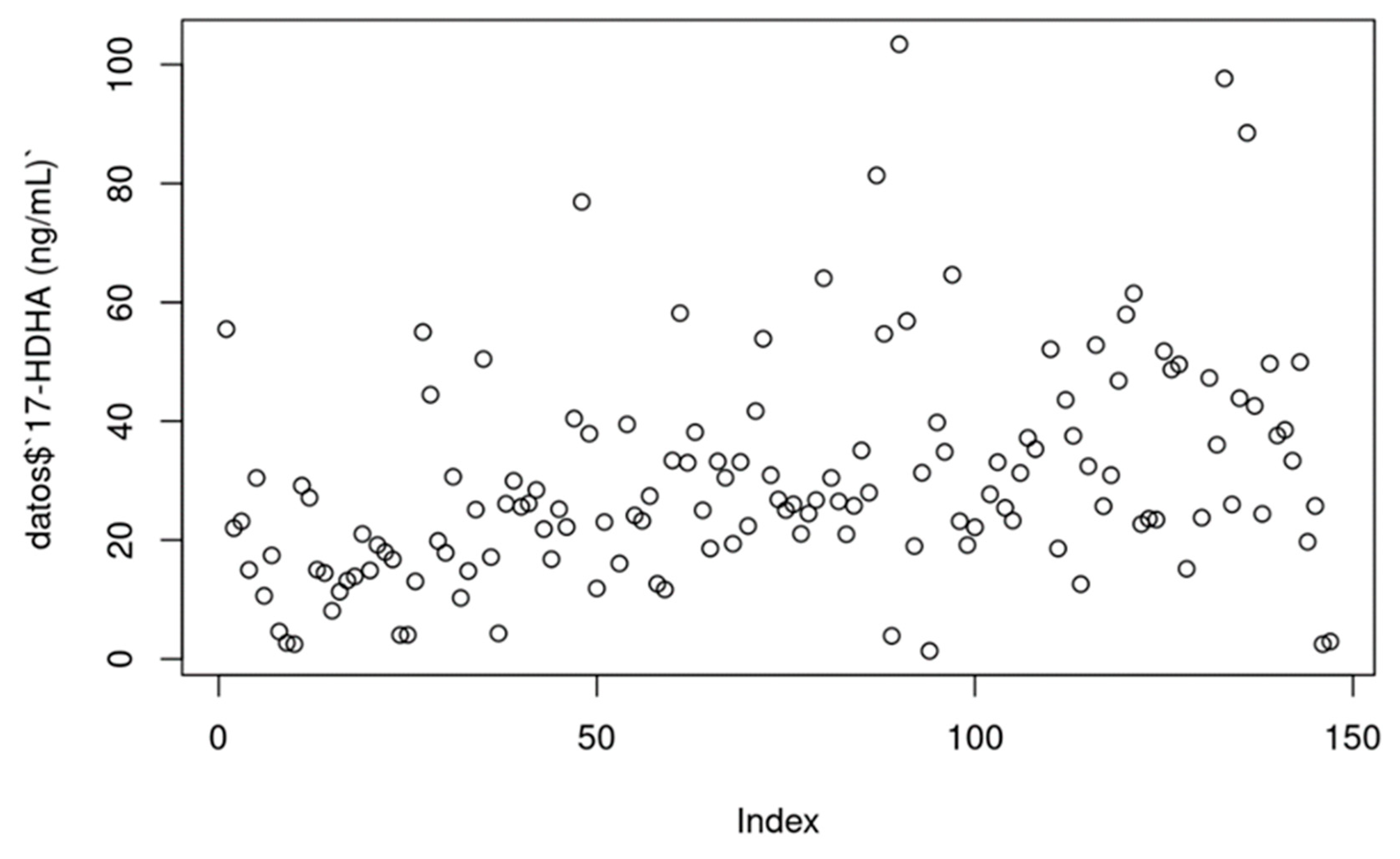

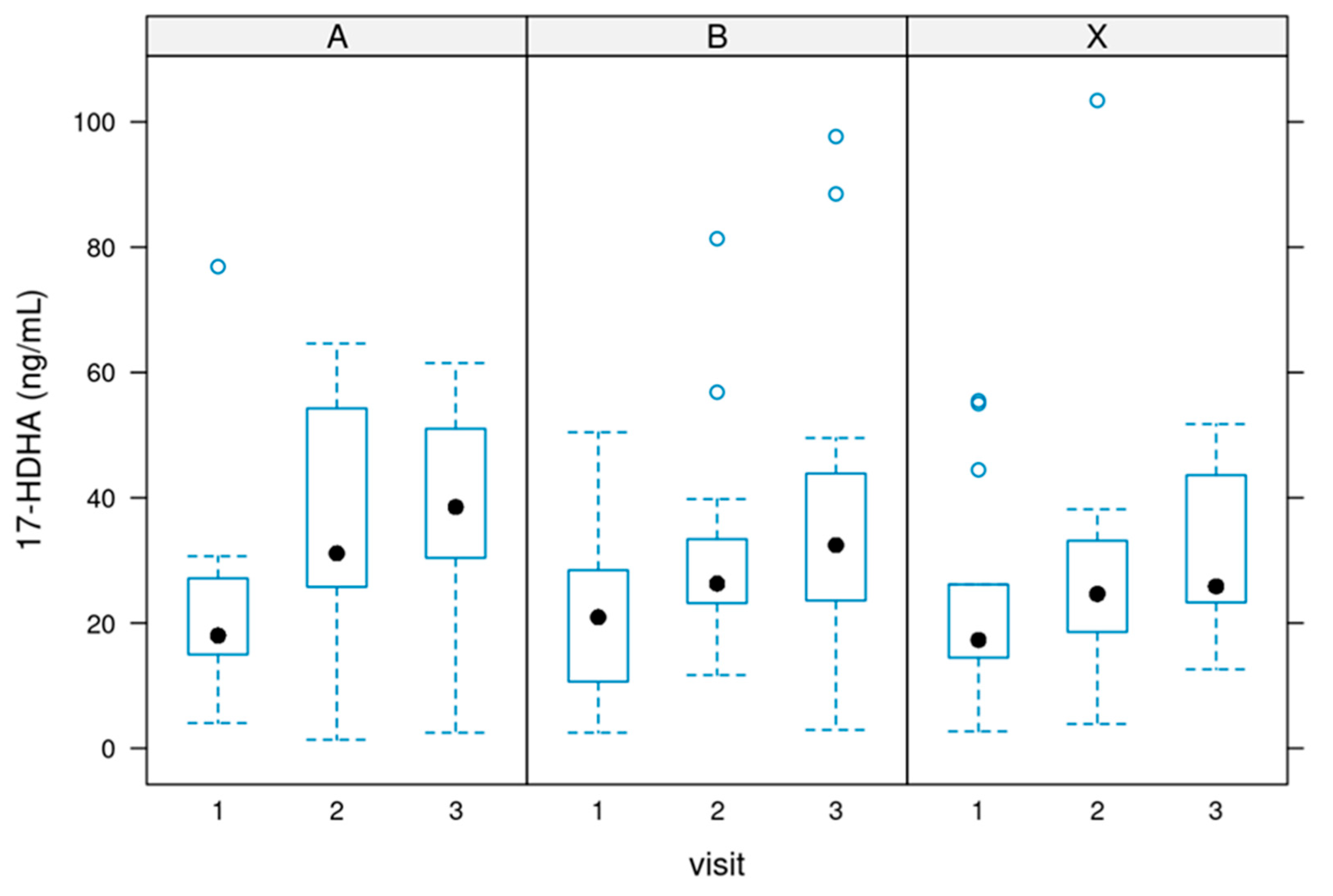

Values for 17-HDHA

17-HDHA [ng/ml]: In most cases, serum 17-HDHA concentrations ranged from 0 to 100 ng/mL. P value = 0.000746.

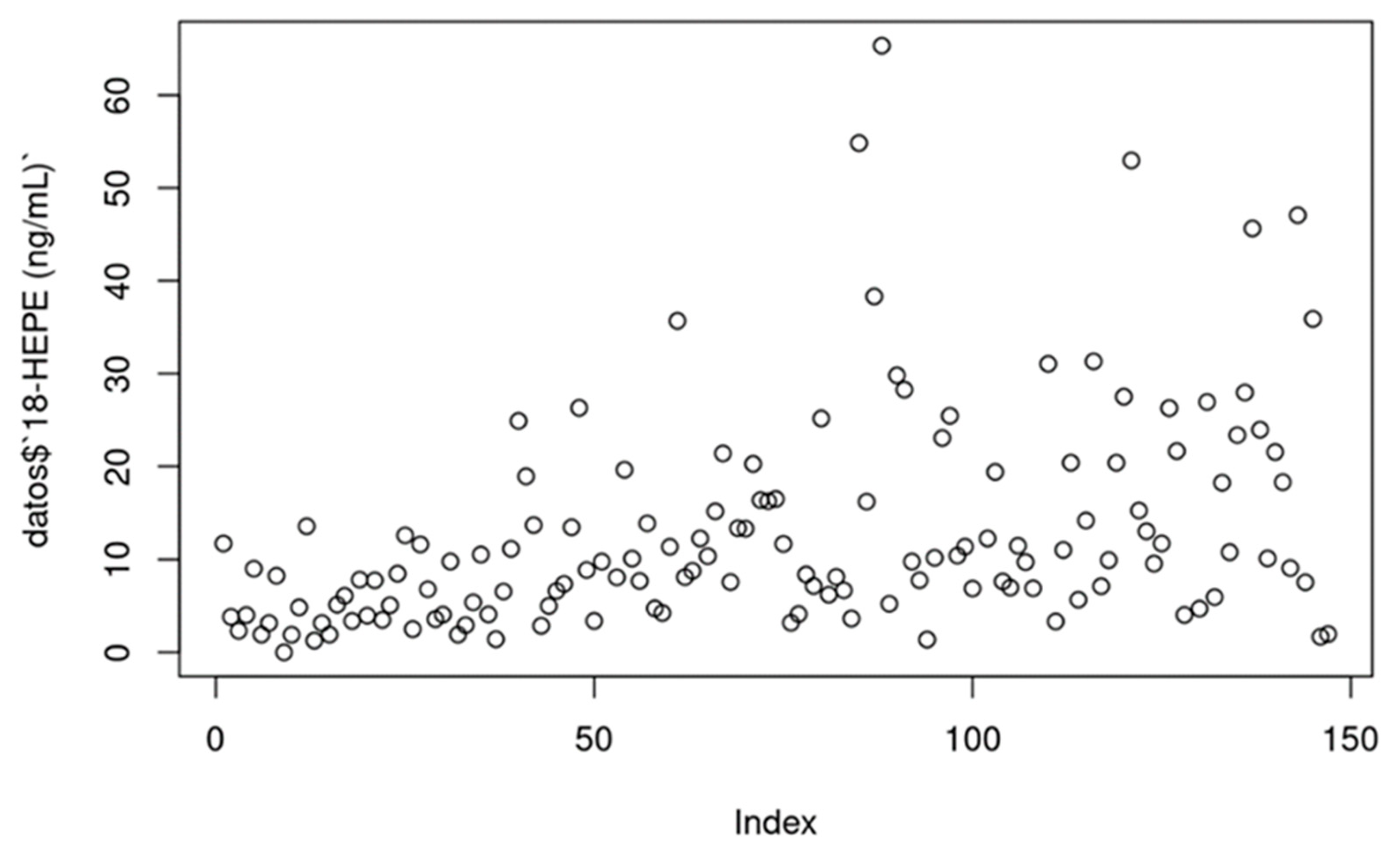

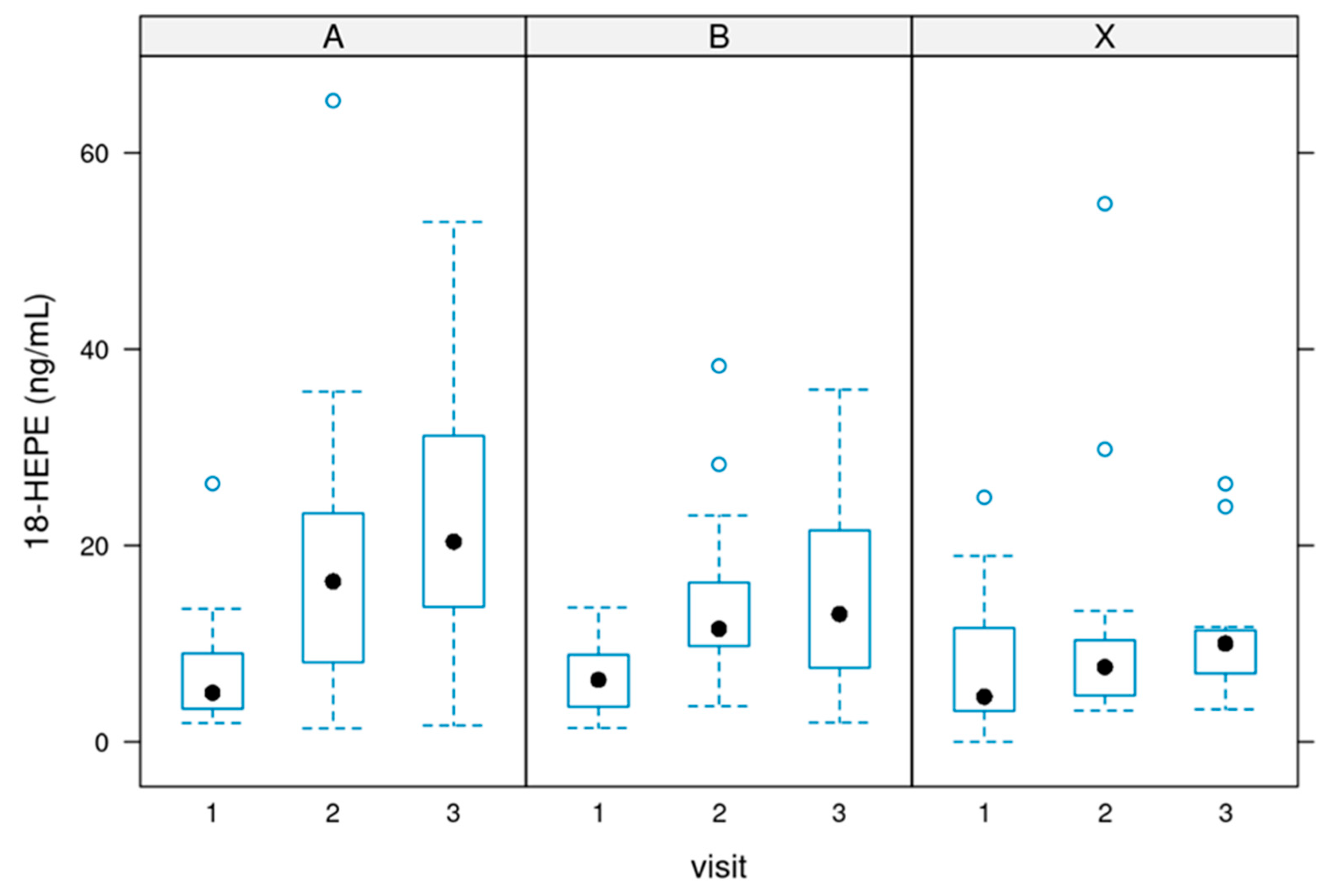

Values of 18-HEPE

18-HEPE [ng/ml]: Serum concentrations of 18-HEPE ranged from 0 to 50 ng/ml in most cases (treatments per week). P value = 0.0000133.

The total amount of the three monohydroxylates

During the supplementation, there was a significant increase in the sum of all three parameters. This shows the efficacy of the supplementation. The differences before and after the supplementation were significant.

Figure 7 depicts the data (p-value of 0.000459).

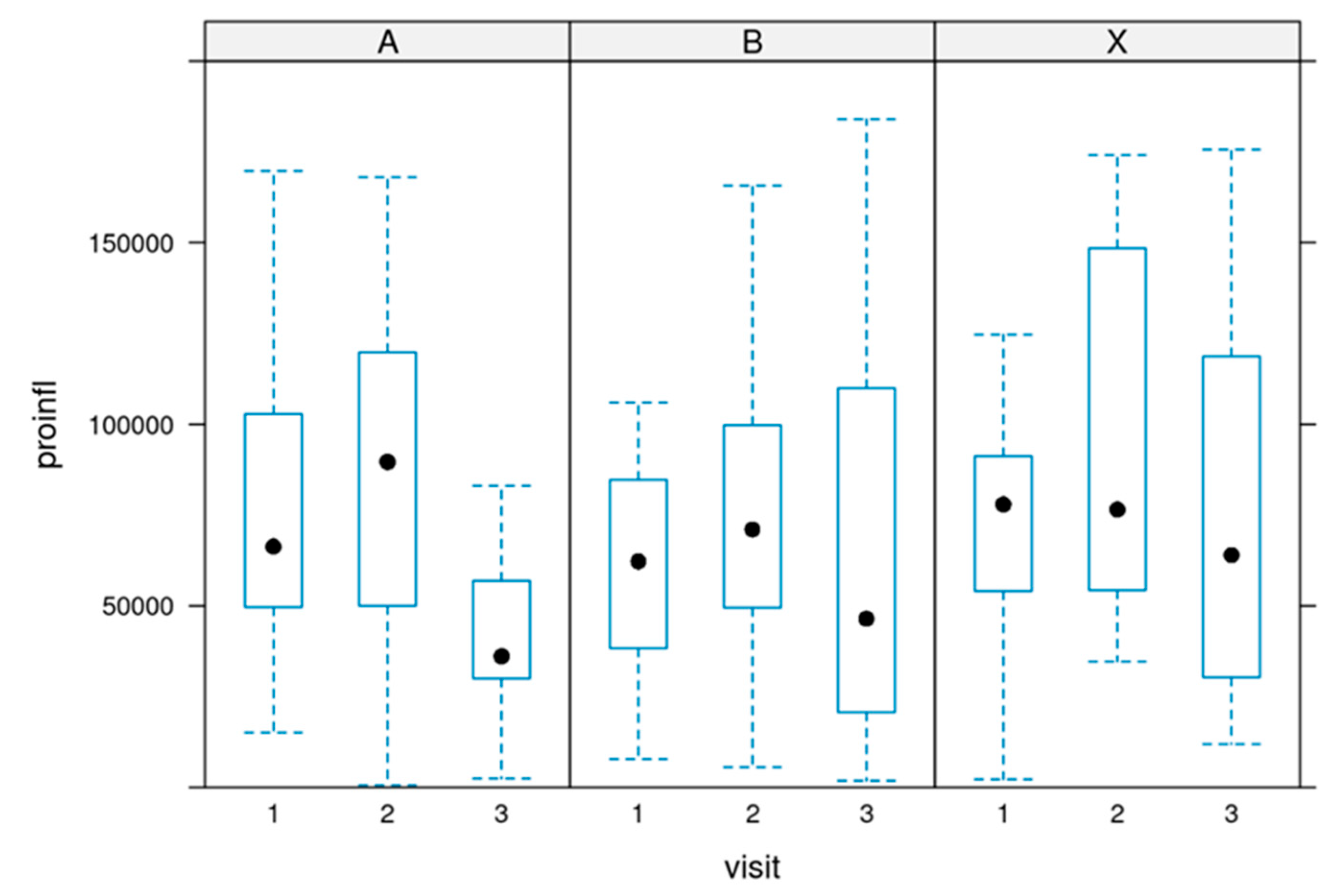

The sum of pro-inflammatory values:

The sum of pro-inflammatory markers was calculated by adding the values of PGE2 + PGD2 + PGF2α + TXB2 + LTB4 [pg/ml] in each register:

The cumulative sum of all measured pro-inflammatory markers did not change significantly during the supplementation. There was a slight trend in a reduction. P value = 0.232.

Figure 8 depicts the development in all three groups.

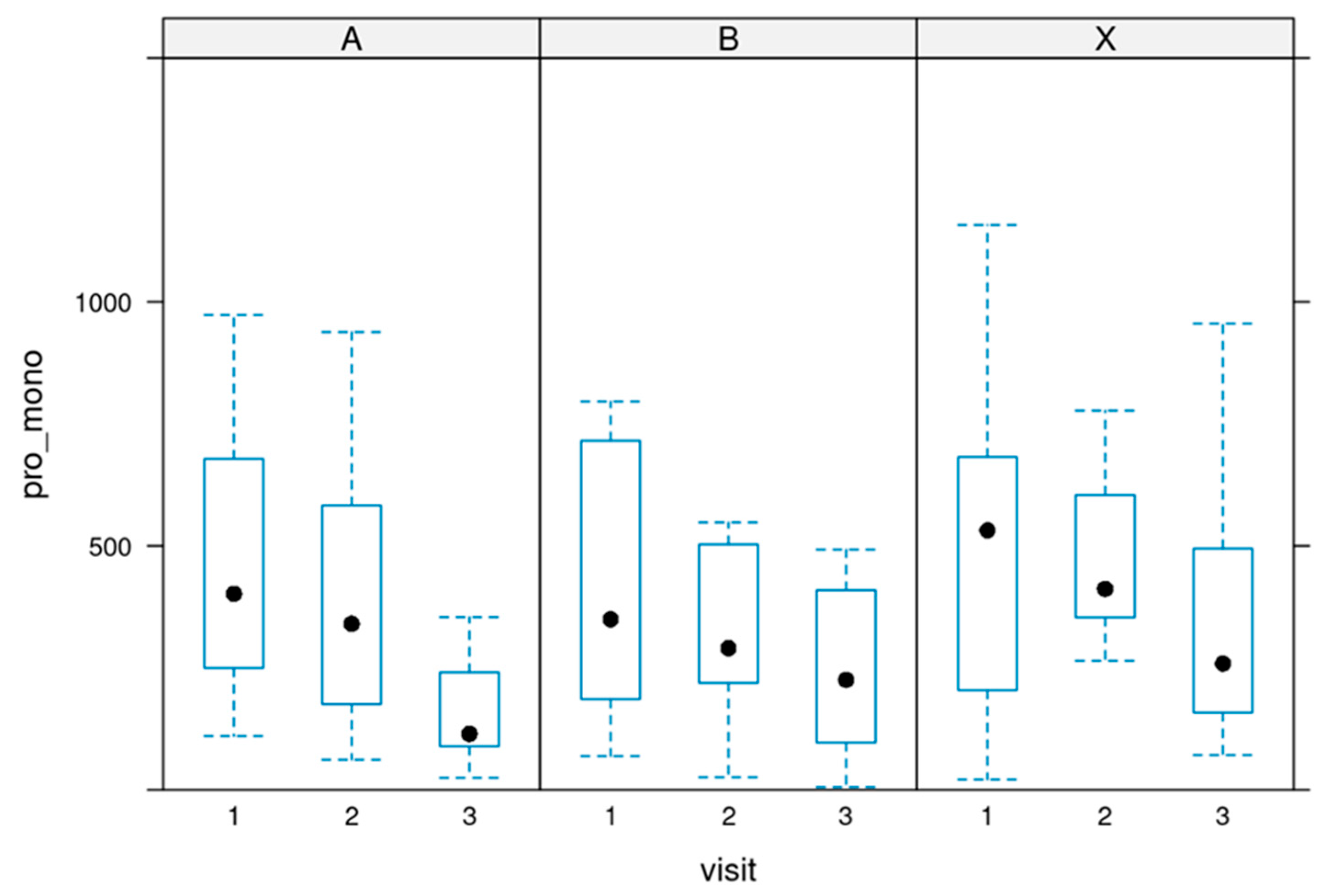

The ratio between pro-inflammatory and pro-resolutive markers.

Pro-inflammatory/monohydroxylated ratio: The ratio between pro-inflammatory (sum) and monohydroxylated (sum) markers was calculated for each record.

There was a significant change in the ratio. During the supplementation, an improvement in the ratio in all three groups could be observed, showing the high efficacy of the supplementation.

The ratios decreased after the first four weeks and continued to decline until the end of the 12-week of supplementation.

Figure 9 depicts the ratio.

These changes were significant, with a p-value of 0.025.

Clinical changes

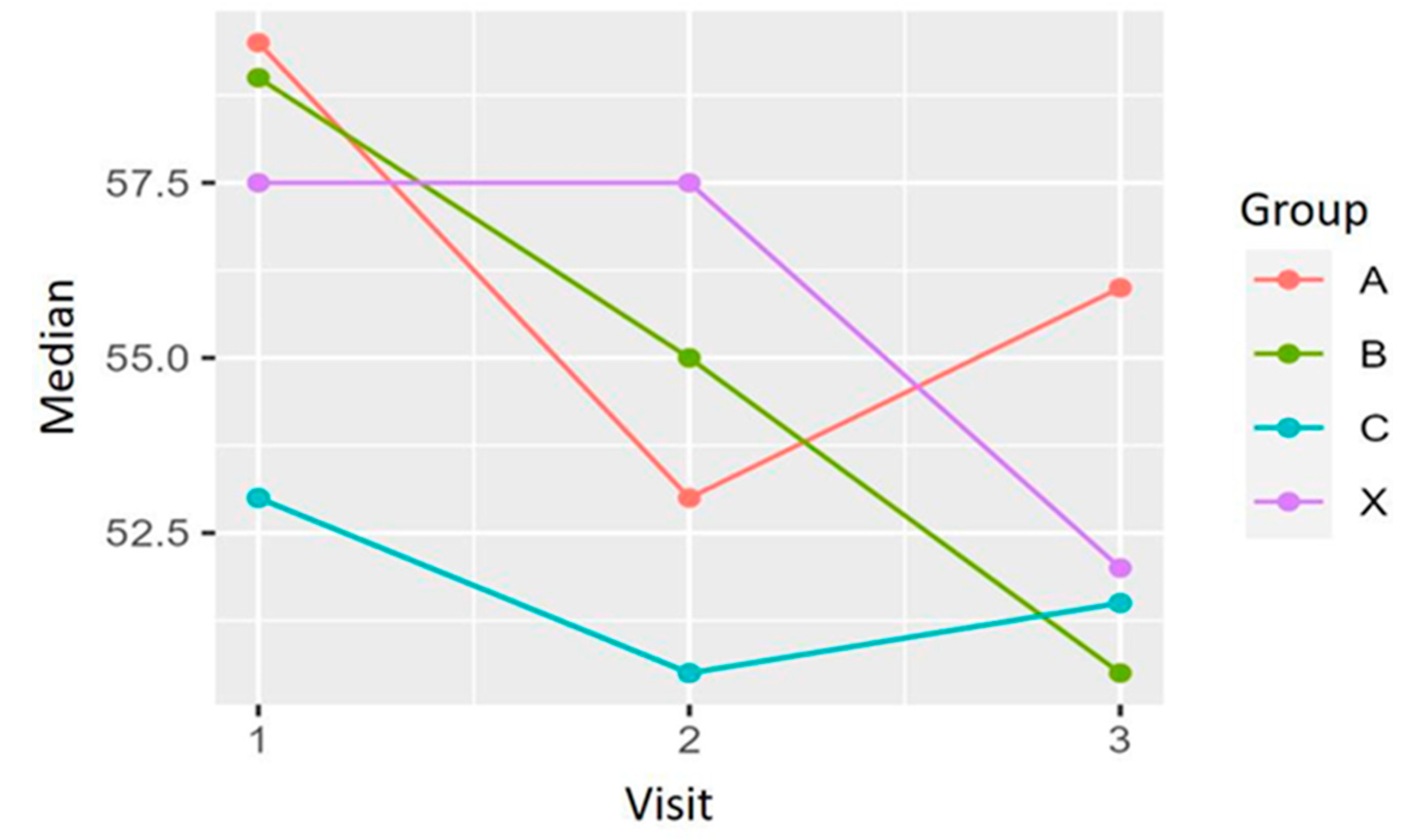

To determine the effect of the investigated product on the clinical manifestation of long COVID-19, as secondary objectives of the study, its impact on the patients’ fatigue and dyspnoea, two of the most prevalent symptoms observed in these patients, were assessed. The secondary efficacy variables are:

Both scales are commonly used and validated methods to assess either fatigue or the degree of functional disability due to dyspnoea.

The evolution of these clinical variables, including the four treatment groups, was analysed using a mixed general linear model.

Fatigue

The differences between the baseline FSS scores and 4 and 12 weeks after treatment were calculated. All groups tend to improve the fatigue symptoms included in the FSS questionnaire. No significant differences are detected among the four treatment groups, but a clear trend in the improvement can be seen in group X, which used 500 mg of marine oil per day.

An improvement of 9 % in the mean value for fatigue could be observed between weeks 4 and 12 for the patients in the 500 mg daily.

Dyspnea

Differences between baseline and weeks 4 and 12 in the mMRC scale scores were calculated for each patient. The Chi-squared was used for the analysis of the differences between treatments. For the differences between baseline and week 12, X-squared = 8.2496 and p-value = 0.509; between baseline and week 4, X-squared = 7.3615 and p-value = 0.600. A slight improvement can be observed for each group regarding the frequency and percentage of patients in each grade of the scale. However, there were no significant differences in the evolution of the mMRC scores among the four treatment groups during the study.

Figure 11 shows the development of the mMRC scores for each treatment group at baseline (1), after four weeks of treatment (2), and at the end of the study, after 12 weeks of treatment (3). Data revealed an overall slight improvement in the MMRC scale in all groups at the end of the study. Most of the patients included experienced none or 1 point of improvement. Analysis revealed no differences among the study groups (see

Table 1).

Discussion

The present work observed a significant difference in the amount of the lipid mediators 14-HDHA, 17-HDHA, and 18-HEPE after supplementing with a marine oil-enriched formulation in patients with a Post Covid Syndrome.

Given that there were no statistically significant differences between the dosages of 500mg, 1500mg, and 3000mg, a clear trend in favouring the 500 mg use per day can be postulated.

SARS-CoV-2 and PCS can lead to a robust inflammatory response, represented by a high abundance of pro-inflammatory signalling molecules like Interleukin-6, C-reactive protein, an increased erythrocyte sedimentation rate, and fibrinogen levels [40].

It was demonstrated by the evaluation of LC-MS/MS data that the ratio between (pro-inflammatory) eicosanoid derivatives and pro-resolutive lipid mediator molecules was significantly improved by using the lipid mediators.

Previous studies showed that the pro-inflammatory markers were higher in SARS-CoV-2-affected subjects than in healthy ones [41]. In recent work, the lipidomes of COVID-19 patients with severe symptoms, such as ARDS, were compared to the lipid profiles of only moderately affected patients. In that case, the lipid mediator products of ALOX12 and COX2 decreased, while those of ALOX5 and cytochrome P450 increased [27].

The pro-thrombotic alterations observed in COVID-19 patients may derive from processes initiated by the damage of virus-infected cells. In patients who require intensive care treatment, high levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines were detected compared to subjects with a moderate manifestation of the disease [17]. Those extensive inflammatory processes may lead to aggravated coagulatory reactions.

An important diagnostic parameter for induction of coagulation is the increase in D-Dimer levels, and for COVID-19, it has become an indicator of the severity of the disease. Subjects who develop DIC (disseminated intravasal coagulopathy) or sepsis have a high mortality risk [42–44]. The processes leading to these severe coagulopathies are not entirely understood yet. However, the underlying inflammation gives rise to coagulatory alterations instead of the virus.

On the other hand, hemorrhagic bleeding disorders are not observed in the context of SARS-CoV-2 infections, which contrasts with other single-stranded RNA viruses, such as Ebola [3]. Also, data from Wuhan support the conception that the inflammatory host response leads to coagulopathies via interlinked signaling pathways.

A comprehensive cohort study demonstrated a relationship between activated neutrophils, platelets, and the dysregulated coagulation cascade that finally led to immunothrombotic damage in various tissues. Utilizing coagulation tests with peripheral blood samples and histopathological analyses, the scientists identified the systemic hypercoagulability with microvascular thrombosis observed in several organs as characteristic key contributors for severe manifestations of ARDS in COVID-19. Consequently, platelet and neutrophil counts and signs for coagulation cascade activation were suggested as valuable pharmaceutical targets for the treatment of COVID-19 [45]. Therefore, the systematic surveillance of coagulation processes combined with prophylactic anticoagulant therapy has become essential for managing COVID-19-affected patients.

The pure elimination of the infectious agent may not be sufficient to re-establish homeostasis in affected patients. Still, a relatively active cessation of the inflammatory processes and clearing the infection sites is required.

It has been demonstrated in mouse models that thrombi were markedly reduced when the factor resolving D4 (RvD4) was applied. The treatment also led to decreased neutrophil infiltration and a higher abundance of monocytes in a pro-resolutive state and cells in the early stages of apoptosis. RvD4 also triggered enhanced biosynthesis of further pro-resolutive resolvins of the D-series family. The SPMs, mainly RvD4, were shown to be important modulators of the gravity of thrombo-inflammatory processes while furthering the resolution of thrombi [46].

Interestingly, in patients with coronary arterial disease, certain pro-resolutive SPMs are reduced compared to healthy subjects. However, when treated with pharmacological doses of EPA and DHA for one year, a clear shift in lipid mediator profile compared to non-treated patients was observed with a decrease in triglyceride levels and pro-inflammatory prostaglandins and a significant increase in certain pro-resolutive SPMs. The SPM-triggered macrophage-based phagocytosis of clots was enhanced in patients treated with the SPM precursors [35].

The first studies of this nutritional supplement have demonstrated its effectiveness in raising SPMs in plasma in different physiological and pathological conditions.

Having detected a significant deficit of SPMs in conditions of inflammation, and as described in the protocol, it is estimated that applying this new formulation will substantially improve both the SPMs in plasma and serum and the ratio between SPMs and prostaglandins.

In one study [36] it was possible to see that the ideal doses of DHA, EPA and the monohydroxylates layed between 1500 mg and 3000 mg. The commune to all studies was:

(a) zero incidence of side effects, and

(b) the substantial increase in SPMs.

To further shed light on the role of SPMs in COVID-19 disease, it will be informative to validate our data in clinical trials. This supplementation might be beneficial by preventing the cytokine storm observed in severe manifestations of COVID-19 disease, as the SPMs may enforce the pro-resolutive axis of inflammatory processes. This also helps improve chronic courses associated with heart and lung tissue inflammation. Also, supplementation with SPMs or their precursor metabolites may improve pathologic conditions for recovered or vaccinated subjects. As demonstrated in the present study, the increase in SPMs observed in sera of PCS patients might be effective in managing this chronic situation.

Also, the improvement in fatigue and dyspnoea is promising. The supplementation with this marine oil enriched in SPMs hence represents an approach in managing PCS patients.

Clinical Trial Registry: ISRCTN13270662

Author Contributions

Asun Gracia Aznar: Investigation, data curation, Project administration; Pilar Rodriguez-Ledo: Investigation; Isabel Nerin: Investigation; Pedro Antonio Regidor: Conceptualization, supervision, writing-original draft; Fernando Moreno Egea: Project administration, visualization; Rafael Gracia Banzo. Resources; Rocio Gutierrez: Software; formal analyses; writing-review; Jose Miguel Rizo: Project administration, funding acquisition. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The study was funded by Insud Pharma.

References

- Wu YC, Chen CS, Chan YJ. Overview of the 2019 Novel Coronavirus (2019-nCoV): The Pathogen of Severe Specific Contagious Pneumonia (SSCP). Journal of the Chinese Medical Association 2020; 11: 217-220. [CrossRef]

- Huang C, Wang Y, Li X, Ren L, Zhao J, Hu Y, Zhang L, Fan G, Xu J, Gu X, Cheng Z, Yu T, Xia J, Wei Y, Wu W, Xie X, Yin W, Li H, Liu M, Xiao Y, Gao H, Guo L, Xie J, Wang G, Jiang R, Gao Z, Jin Q, Wang J, Cao B. Clinical features of patients infected with 2019 novel coronavirus in Wuhan, China. Lancet 2020; 395: 497-506. [CrossRef]

- Max Roser, Hannah Ritchie and Esteban Ortiz-Ospina. Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19)-Statistics and Research. https://ourworldindata.org/coronavirus.

- Wang D, Hu B, Hu C, Zhu F, Liu X, Zhang J, Wang B, Xiang H, Cheng Z, Xiong Y, Zhao Y, Li Y, Wang X, Peng Z. Clinical Characteristics of 138 Hospitalized Patients With 2019 Novel. Coronavirus-Infected Pneumonia in Wuhan, China. JAMA 2020; 323: 1061-1069. [CrossRef]

- Zhou F, Yu T, Du R, Fan G, Liu Y, Liu Z, Xiang J, Wang Y, Song B, Gu X. Clinical course and risk factors for mortality of adult inpatients with COVID-19 in Wuhan, China: a retrospective cohort study. The Lancet 2020; 395: 1054-1062. [CrossRef]

- Sanders JM, Monogue ML, Jodlowski TZ, Cutrell JB. Pharmacologic Treatments for Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) JAMA 2020; 323: 1824-1836. [CrossRef]

- Krolewiecki A, Lifschitz A, Moragas M, Travacio M, Valentini R, Alonso DF et al. Antiviral effect of high-dose ivermectin in adults with COVID-19: A proof-of-concept randomized trial. E Clinical Medicine 2021; 37, 100959. [CrossRef]

- D’Elia RV, Harrison K, Oyston PC, Lukaszewski RA, Clark GC. Targeting the "cytokine storm" for therapeutic benefit. Clin Vaccine Immunol 2013; 20: 319–327. [CrossRef]

- Wu Z, McGoogan JM. Characteristics of and important lessons from the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) outbreak in China: summary of a report of 72 314 cases from the Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention. JAMA 2020; 323: 1239-1242. [CrossRef]

- Cao B, Wang Y, Wen D, Liu W, Wang J, Fan G, Ruan L, Song B, Cai Y, Wei M, Li X, Xia J, Chen N, Xiang J, Yu T, Bai T, Xie X, Zhang L, Li C, Yuan Y, Chen H, Li H, Huang H, Tu S, Gong F, Liu Y, Wei Y, Dong C, Zhou F, Gu X, Xu J, Liu Z, Yi Y, Li H, Shang L, Wang K, Li K, Zhou X, Dong X, Qu Z, Lu S, Hu X, Ruan S, Luo S, Wu J, Peng L, Cheng F, Pan L, Zou J, Jia C, Wang J, Liu X, Wang S, Wu X, Ge Q, He J, Zhan H, Qiu F, Guo L, Huang C, Jaki T, Hayden FG, Horby PW, Zhang D, Wang C. A trial of lopinavir-ritonavir in adults hospitalized with severe Covid-19. New England Journal of Medicine 2020; 382: 1787-1799. [CrossRef]

- Guan W-J, Ni Z-Y, Hu Y, Liang W-H, Ou C-Q, He J-X, Liu L, Shan H, Lei C-L, Hui DSC, Du B, Li L-J, Zeng G, Yuen K-Y, Chen R-C, Tang C-L, Wang T, Chen P-Y, Xiang J, Li S-Y, Wang J-L, Liang Z-J, Peng Y-X, Wei L, Liu Y, Hu Y-H, Peng P, Wang J-M, Liu J-Y, Chen Z, Li G, Zheng Z-J, Qiu S-Q, Luo J, Ye C-J, Zhu S-Y, Nan-Shan Zhong N-S. Clinical characteristics of coronavirus disease 2019 in China. New England Journal of Medicine. 2020:1708-1720. [CrossRef]

- Cheng Y, Luo R, Wang K, Zhang M, Wang Z, Dong L, Li J, Yao Y, Ge S and Xu G. Kidney disease is associated with in-hospital death of patients with COVID-19. Kidney international 2020; 97:829-83. [CrossRef]

- Guo T, Fan Y, Chen M, Wu X, Zhang L, He T, Wang H, Wan J, Wang X, and Lu Z. Cardiovascular Implications of Fatal Outcomes of Patients with Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19). Jama Cardiology 2020: 811-818. [CrossRef]

- Shi S, Qin M, Shen B, Cai Y, Liu T, Yang F, Gong W, Liu X, Liang J, Zhao Q, Huang H, Yang B and Huang C. Association of Cardiac Injury with Mortality in Hospitalized Patients With COVID-19 in Wuhan, China. Jama Cardiology 2020: 802-810. [CrossRef]

- Xu Z, Shi L, Wang Y, Zhang J, Huang L, Zhang C, Liu S, Zhao P, Liu H, Zhu L. Pathological findings of COVID-19 associated with acute respiratory distress syndrome. The Lancet respiratory medicine 2020; 8:420-422. [CrossRef]

- Wang T, Chen R, Liu C, Liang W, Guan W, Tang R, Tang C, Zhang N, Zhong N, Li S. Attention should be paid to venous thromboembolism prophylaxis in managing COVID-19. The Lancet Haematology 2020; 362-363. [CrossRef]

- Tang N, Bai H, Chen X, Gong J, Li D, Sun Z. Anticoagulant treatment is associated with decreased mortality in severe coronavirus disease 2019 patients with coagulopathy. Journal of thrombosis and hemostasis 2020; 18:1094-1099. [CrossRef]

- Han H, Yang L, Liu R, Liu F, Wu KL, Li J, Liu XH, Zhu CL. Prominent changes in blood coagulation of patients with SARS-CoV-2 infection. Clinical chemistry and laboratory medicine. 2020:1116-1120. [CrossRef]

- Cui S, Chen S, Li X, Liu S, Wang F. Prevalence of venous thromboembolism in patients with severe novel coronavirus pneumonia. Journal of Thrombosis and Haemostasis. 2020; 18:1421-1424. [CrossRef]

- Serhan CN, Dalli J, Colas RA, Winkler JW, Chiang N. Protectins and maresins: New pro-resolving families of mediators in acute inflammation and resolution bioactive metabolome. Biochim Biophys Acta 2015; 1851:397-413.

- Wang Q, Zheng X, Cheng Y, Zhang YL, Wen HX, Tao Z, Li H, Hao Y, Gao Y, Yang L-M, Smith FG, Huang C-J, Jin S-W. Resolvin D1 stimulates alveolar fluid clearance through alveolar epithelial sodium channel, Na, K-ATPase via ALX/cAMP/PI3K pathway in lipopolysaccharide-induced acute lung injury. J Immunol 2014; 192:3765-3777. [CrossRef]

- Serhan, CN. Treating inflammation and infection in the 21st century: new hints from decoding resolution mediators and mechanisms. FASEB J 2017; 31:1273–1288. [CrossRef]

- Serhan CN, Chiang N. Resolution phase lipid mediators of inflammation: agonists of resolution. Curr Opin Pharmacol 2013;13(4):632–40. [CrossRef]

- Wang Q, Yan SF, Hao Y, Jin SW. Specialized Pro-resolving Mediators Regulate Alveolar Fluid Clearance during Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome. Chinese Medical Journal 2018; 131(8): 982-989. [CrossRef]

- Matthay MA, Ware LB, Zimmerman GA. Acute respiratory distress syndrome. J Clin Invest 2012; 122: 2731-2740. [CrossRef]

- Cilloniz C, Pantin-Jackwood MJ, Ni C, Goodman AG, Peng X, Proll SC, Carter VS, Rosenzweig ER, Szretter KJ, Katz JM, Korth MJ, Swayne DE, Tumpey TM, Katze MG. Lethal dissemination of H5N1 influenza virus is associated with dysregulation of inflammation and lipoxin signaling in a mouse infection model. J Virol 2010; 84:7613–7624. [CrossRef]

- Schwarz B, Sharma L, Roberts L, Peng X, Bermejo S, Leighton I, Casanovas-Massana A, Minasyan M, Farhadian S, Ko AI, Yale IMPACT Team, Dela Cruz CS, Bosio CM. Cutting Edge: Severe SARS-CoV-2 Infection in Humans Is Defined by a Shift in the Serum Lipidome, Resulting in Dysregulation of Eicosanoid Immune Mediators. J Immunol. 2020 Dec 04; ji2001025. [CrossRef]

- WHO/2019-nCoV/Post_COVID-19_condition/Clinical_case_definition/2021. A clinical case definition of post COVID-19 condition by a Delphi consensus. 6 October 2021.

- Tabas I, Glass CK. Anti-inflammatory therapy in chronic disease: challenges and opportunities. Science 2013;339(6116):166–72. [CrossRef]

- Serhan CN, Clish CB, Brannon J, Colgan SP, Chiang N, Gronert K. Novel Functional Sets of Lipid-derived Mediators with Antiinflammatory Actions Generated from Omega-3 Fatty Acids via Cyclooxygenase 2–Nonsteroidal Antiinflammatory Drugs and Transcellular Processing. J. Exp. Med. Volume 192, Number 8, October 16, 2000 1197–1204.

- Serhan CH, Hong S, Gronert K, Colgan SP, Devchand PR, Mirick G, Moussignac RL. Resolvins: A Family of Bioactive Products of Omega-3 Fatty Acid Transformation Circuits Initiated by Aspirin Treatment that Counter Proinflammation Signals. J. Exp. Med. Volume 196, Number 8, October 21, 2002, 1025–1037.

- Bannenberg GL, Chiang N, Ariel A, Arita M, Tjonahen E, Gotlinger KH, Hong S, Serhan CH. Molecular circuits of resolution: formation and actions of resolvins and protectins. J Immunol 2005 Apr 1;174(7):4345-55. [CrossRef]

- Spite M, Norling LV, Summers L, Yang R, Cooper D, Petasis NA, Flower RJ, Perretti M, Serhan CH. Resolvin D2 is a potent regulator of leukocytes and controls microbial sepsis. Nature. 2009 October 29; 461(7268): 1287–1291. [CrossRef]

- Chiang N, Fredman G, Bäckhed F, Oh SF, Vickery T, Schmidt BA, Serhan CN. Infection Regulates Pro-Resolving Mediators that Lower Antibiotic Requirements. Nature: 484(7395): 524–528. [CrossRef]

- Elajami, TK, Colas RA, Dalli J, Chiang N, Serhan CN, Welty FK. Specialized pro-resolving lipid mediators in patients with coronary artery disease and their potential for clot remodeling. FASEB J. 2016; 30: 2792-2801. [CrossRef]

- Souza PR, Marques RM, Gomez EA, et al. Enriched marine oil supplements increase peripheral blood specialized pro-resolving mediators concentrations and reprogram host immune responses: a randomized double-blind placebo-controlled study. Circ Res. 2020;126(1):75–90.

- Colas RA, Shinohara M, Dalli J, Chiang N, Serhan CN. Identification and signature profiles for pro-resolving and inflammatory mediators in human tissue. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 2014; 307(1): C9-C57. [CrossRef]

- English JT, Norris PC, Hodges RR, Dartt DA, Serhan CN. Identifying and profiling specialized pro-resolving mediators in Human Tears by Lipid Mediator Metabolomics. Prostaglandins Leukot Essent Fatty Acids 2017 Feb; 117:17-27. [CrossRef]

- Dalli J, Colas RA, Walker ME, Serhan CN. Lipid Mediator Metabolomics Via LC-MS/MS Profiling and Analysis. Editor. Martin Giera. Clinical Metabolomics pp 59-72. 2018. [CrossRef]

- Chen G, Wu D, Guo W, Cao Y, Huang D, Wang H, Wang T, Zhang X, Chen H, Yu H, Zhang X, Zhang M, Wu S, Song J, Chen T, Han M, Li S, Luo X, Zhao J, Ning Q. Clinical and immunologic features in severe and moderate coronavirus disease 2019. J Clin Invest. 2020 May 01;130(5):2620-2629. [CrossRef]

- Regidor PA, De La Rosa X, Santos FG, Rizo JM, Gracia Banzo R, Silva RS. Acute severe SARS-COVID-19 patients produce pro-resolving lipids mediators and eicosanoids. Europe Review Med and Pharmacol Sciences. 2021; 25: 6782-6796.

- Tang N, Li D, Wang X, Sun Z. Abnormal coagulation parameters are associated with poor prognosis in patients with novel coronavirus pneumonia. J Thromb Haemost. 2020 Apr; 18(4): 844–847. [CrossRef]

- Thachil J, Tang N, Gando S, Falanga A, Cattaneo M, Levi M, Clark C, Iba T. ISTH interim guidance on recognizing and managing coagulopathy in COVID-19. J Thromb Haemost. 2020 May;18(5):1023-1026. [CrossRef]

- Taylor FB Jr, Toh CH, Hoots WK, Wada H, Levi M. Towards definition, clinical and laboratory criteria, and a scoring system for disseminated intravascular coagulation. Thromb Haemost. 2001; 86(5): 1327-1330.

- Nicolai L, Leunig A, Brambs S, Kaiser R, Weinberger T, Weigand M, Muenchhoff M, Hellmuth JC, Ledderose S, Schulz H, Scherer C, Rudelius M, Zoller M, Höchter D, Keppler O, Teupser D, Zwißler B, Bergwelt-Baildon M, Kääb S, Massberg S, Pekayvaz K, Stark K. Immunothrombotic Dysregulation in COVID-19 Pneumonia is Associated with Respiratory Failure and Coagulopathy. Circulation. 2020; 142: 1176–1189. [CrossRef]

- Cherpokova D, Jouvene CC, Libreros S, DeRoo EP, Chu L, de la Rosa X, Norris PC, Wagner DD, Serhan CN. Resolvin D4 attenuates the severity of pathological thrombosis in mice. Blood. 2019 Oct 24;134(17):1458-1468. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).