1. Introduction

Health professionals increasingly face more stressful situations as a result of internal factors and persistent challenges in the modern healthcare system [

1,

2]. Specifically, nurses faced high levels of stress and burnout during and after the COVID-19 pandemic due to work overload, staffing shortages, and health issues [

1]. The few studies that have analyzed COVID-19-related perceived stress in health students and professionals highlight its association with sociodemographic variables such as sex, age, religion [

3,

4], years of work experience, work area [

5], personal and family history of epidemiological infection [

6], fears, worries, and coping strategies [

7].

Coping is defined as a psychological construct that groups together a wide variety of thoughts, feelings, and behaviors that individuals use to manage internal or external demands from stressful situations that exceed their own skills [

8,

9,

10]. Coping strategies comprise specific actions aimed at modifying the stimulus that a stressful situation generates and controlling the emotions that this stimulus produces in individuals [

8,

9,

11].

Initially, Folkman and Lazarus [

12] proposed to classify coping strategies based on the coping focus: problem-focused coping (strategies aimed at actively solving stressful situations) and emotion-focused coping (strategies aimed at managing or reducing the emotions and feelings caused by stressful situations). Subsequently, Carver et al., [

13] proposed a distinction based on how they are used: approach coping (strategies aimed at actively coping with stress or related emotions) and avoidance coping (strategies aimed at avoiding stressful situations). Finally, taking into account the outcomes of using coping strategies, we have adaptive coping (more likely leading to desired and favorable outcomes for health) and maladaptive coping (leading to possible benefits in the short term, but more likely to undesired outcomes in the long term) [

14]. However, the outcome of a coping strategy in this last classification varies among individuals and according to their context [

13,

15]. Thus, nurses can cope with a stressful situation and its emotional consequences by actively and directly approaching or avoiding problems [

16].

Based on the after mentioned theoretical models, several scales have been developed to measure coping strategies. The two most commonly used scales are the Ways of Coping Questionnaire (WCQ) developed by Folkman and Lazarus [

17] and the Coping Orientation to Problems Experienced (COPE) designed by Carver et al., [

13]. Likewise, scales have been developed to measure situational or stress-related coping strategies; these include the Pain Coping Questionnaire (PCQ) validated by Reid et al., [

18] to assess the pain coping strategies of children and adolescents; the Multidimensional Coping Inventory (MCI) proposed by Endler and Parker [

19]; and the Coping Inventory for Stressful Situations (CISS) suggested by Endler and Parker [

20]. Although valid and reliable in the sample studied, they are very long scales (39 to 66 items), which would not favor the measurement of associated variables and could limit their use in long research protocols.

One of the most widely used scales to measure coping strategies is the Brief-COPE inventory (BCI). This multidimensional scale made up of 52 items (14 scales) was originally developed by Carver et al., [

13]. Subsequently, based on the theoretical model of Folkman and Lazarus’ WCQ and the model of behavioral self-regulation, the BCI was reduced to 28 items (14 scales). In the healthcare context, numerous psychometric studies have empirically proved that the BCI has adequate psychometric properties for measuring coping strategies in patients in India [

21] and China [

22], family caregivers in the United Kingdom (23), and health professionals in Italy [

15]. It is worth noting that the range of items and factor structure varies widely.

Similarly, during the COVID-19 pandemic, several psychometric studies were conducted to validate the BCI with nurses from different countries. In the United Arab Emirates, Abdul Rahman et al. [

1] found that this scale presented inadequate fit indexes when evaluating four previous models; therefore, they validated a version of 22 items grouped into two factors, using a second-order model. Likewise, in Italy, Bongelli et al. [

15] carried out psychometric studies that reported the validity of a scale of 21 items (seven were eliminated) grouped into six factors (McDonald’s omega = 0.811). Scales validated with nurses reported varied compositions.

Although the BCI is one of the most used scales thanks to its adequate psychometric properties in different contexts and populations, it has not been validated with nurses in Latin America. Therefore, the aim of this study was to analyze the psychometric properties of the BCI—which assesses coping strategies—and to determine its concurrent validity by exploring its association with perceived stress in Peruvian nurses, based on models that include sociodemographic variables and fear of COVID-19.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Sample and Procedures

We conducted a psychometric study with 434 Peruvian nurses to determine the psychometric properties of the BCI by means of a confirmatory factor analysis (CFA). In addition, we implemented three stepwise variable selection regression models to analyze the factors associated with perceived stress and its dimensions.

The study sample consisted of nurses working in health facilities across different cities in Peru, all of whom had access to an electronic device with internet. It excluded nurses who only held a teaching position. We set the minimum sample size according to the classic criterion of ten participants for each item of the questionnaire [

24], for a total of 300 participants. However, we collected data of 450 nurses to increase statistical power. We employed the non-probability convenience sampling method.

Data for this psychometric study were collected through a Google Forms virtual questionnaire between November 2021 and February 2022, during the third wave of COVID-19 infections in Peru. After participants provided informed consent, they were asked about their sociodemographic information (age, sex, marital status) and job-related information (work area, years of work experience, whether they had received stress management training, and whether they had taken care of COVID-19 patients during the last month).

2.2. Measurement Tools

2.2.1. Brief-COPE Inventory

The BCI was based on the COPE [

13] and it was validated by expert judgment with the participation of Peruvian nurses involved in health care and university teaching activities. After calculating the concordance index according to the content validity coefficient by [

25] , we found good concordance (CVC = 0.8250). Subsequently, we did a pilot test with 65 nurses and obtained an adequate reliability (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.910) [

26]. The 30-item Likert scale has four response alternatives ranging from 1 (Seldom) to 4 (Almost always).

2.2.2. Fear of COVID-19 Scale

We used the Fear of COVID-19 Scale validated in Peruvian population [

27]. This seven-item Likert scale has an optimal level of internal consistency (comparative fit index [CFI] = 0.988). Its response alternatives vary between 1 (Strongly disagree) and 5 (Strongly agree). Thus, the higher the score on the scale, the higher the fear. Another study carried out with Peruvian nurses reported that this scale has adequate reliability (McDonald’s omega coefficient = 0.87) [

28].

2.2.3. Perceived Stress Scale

We used the COVID-19-Related Perceived Stress Scale (PSS-10-C)—a modified version of the Perceived Stress Scale (PSS-10)—validated with Colombian nurses [

29]. The PSS-10 was also used with students and health science professionals in Ecuador [

6] y Spain [

30]. The PSS-10-C is a Likert scale with five response options ranging from 1 (Never) to 5 (Always); four of its ten items are reverse coded; and it has an adequate reliability (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.86). We used the 33rd and 66th percentiles for determining stress levels (high, medium, and low). Finally, this scale comprises two dimensions: stress perception (five items) and stress coping (five items) [

31].

2.3. Analysis

In order to meet the objectives of this study, we first performed a reliability analysis of the BCI through a CFA. We did not perform an exploratory factor analysis because the CFA is appropriate when there is a theoretical structure derived from the conceptual framework [

32,

33]. Given the ordinal nature of the data, we used weighted least squares means and variances in the CFA. The fitting criteria were the following: x2/gl ratio lower than 3; CFI and Tucker–Lewis index (TLI) higher than 0.95; root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) lower than 0.08; and standardized root mean square (SRMS) lower than 0.08. The first model—just as it was estimated—did not reach a good fit and, therefore, we saw the need to allow residuals in items 19, 20, and 23 to correlate with each other. Since these items referred to criteria associated with the participants’ religion, it was possible to assume the presence of residual variance not necessarily related to coping strategies. The resulting model is presented in the Results section together with its respective fit indicators. Then, for measuring the reliability of the instrument, we calculated the McDonald’s omega coefficient (ώ) based on the estimated confirmatory model.

Furthermore, for determining the variables associated with perceived stress in nurses, we performed three series of stepwise variable selection regression models as follows: the first series for the total perceived stress scale; the second series for the stress perception scale; and the third series for the stress coping scale. In the three cases, we entered the variables to the model following a three-step sequence: in the first step, the sociodemographic variables (age, sex, marital status, work area, years of work experience, taking care of COVID-19 patients, and having received stress management training); in the second step, the fear of COVID-19 predictor; and in the third step, the dimensions of coping strategies (problem-focused coping, emotion-focused coping, and avoidance coping). Subsequently, we evaluated the significance of the increase in explained variance (R2) with the purpose of comparing the relative fit of these models. Regarding the assumptions of the models, we assessed the normality and homogeneity of variances and the multicollinearity for all cases, and we were able to confirm that these assumptions were correct. Finally, we checked Cook’s D indicators for possible outliers and we identified none in any of the models. We run all these statistical analyses in the R v4.2.1 software [

34].

3. Results

After verifying the filled-out questionnaires, we eliminated sixteen of them because they had at least one unanswered question. Accordingly, the sample for analysis comprised 434 nurses, predominantly female (90.55%). The mean age of the participants was 39.68 years old (SD = 10.17).

Table 1 shows the other characteristics of the sample.

3.1. Confirmatory Factor Analysis of the Coping Strategies Questionnaire

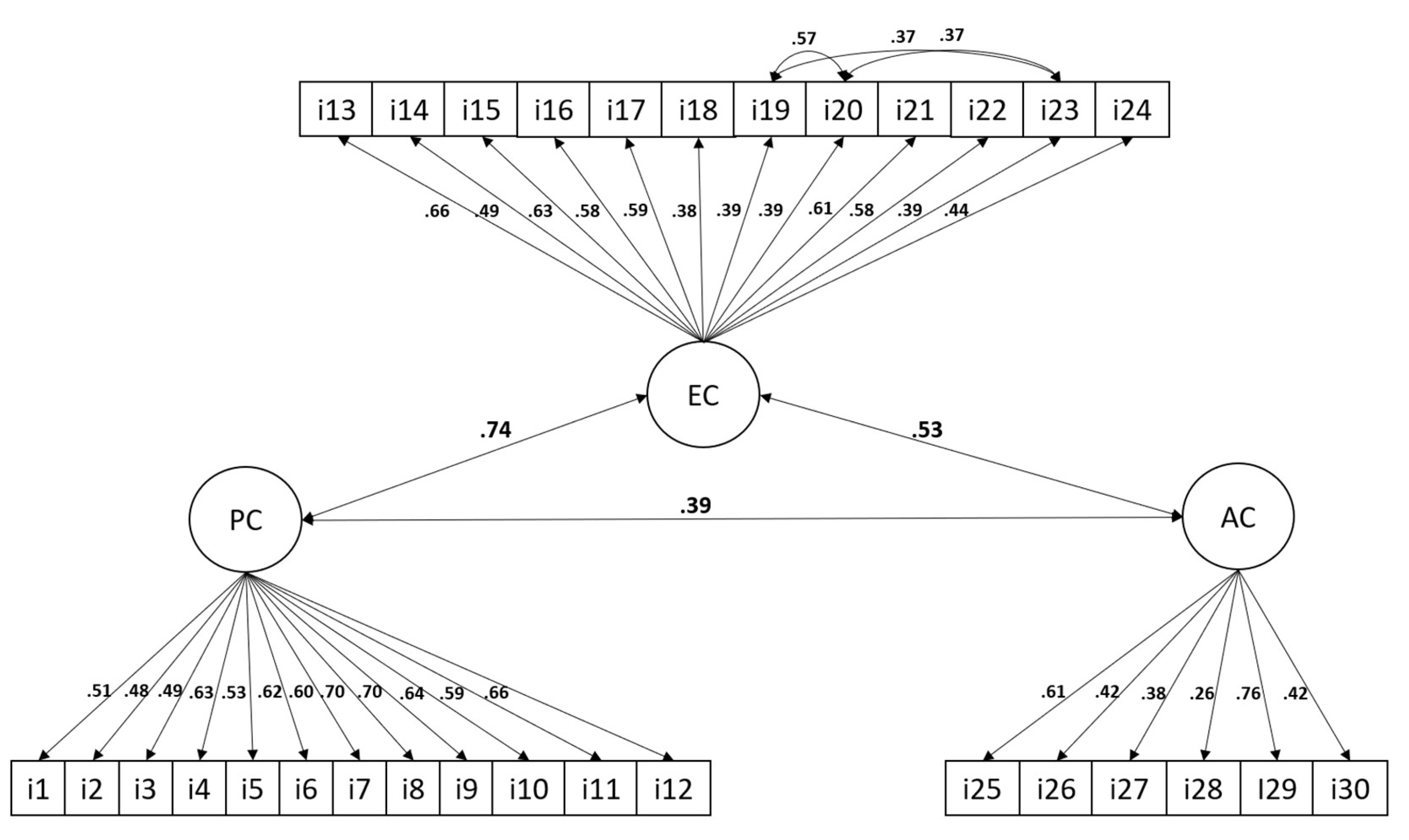

Figure 1 shows the factor model of the BCI. According to the fit indicators of this model, an adequate fit was achieved by allowing residual variances of items 19, 20, and 23 to correlate with each other. Particularly, we observed that the x2/gl ratio was 2.45; both the CFI and the TLI were 0.95; the RMSEA was 0.052 (95% CI: 0.048 - 0.057); and the SRMS was 0.068. When observing the factor loadings of the items on each of the estimated dimensions, we can see that all of them showed standardized factor loadings greater than 0.26, indicating that all the items had considerable loadings on the estimated factors. The correlated residual variances were all significant and higher than 0.37, indicating that items 19, 20, and 23 share a variance that cannot be explained by emotion-focused coping. As for the correlation of coping dimensions, we can observe that problem-focused coping had a very strong and positive correlation with emotion-focused coping (r = 0.74), while keeping a strong correlation with avoidance coping (r = 0.39). For its part, emotion-focused coping had a very strong and positive correlation with avoidance coping (r = 0.53). Lastly, the McDonald’s omega coefficient resulting from the model was 0.90, which indicated that the instrument had an overall excellent internal consistency.

Regarding perceived stress, 36.41% of the sample (158 participants) presented a medium level; 34.79% (151 participants), a low level; and only 28.0% (125 participants), a low high.

3.2. Predictive Models of Perceived Stress

Table 2 shows the series of stepwise regression models for the prediction of total perceived stress. More specifically, we can point out that the first model—which only included sociodemographic variables—explained 5% of variance (R2 = 0.05, p < 0.001). For its part, the model that included the fear of COVID-19 predictor showed an increase in explained variance by 21% (Δ R2 = 0.21, p < 0.001). Finally, the model that included coping strategies presented a 1% increase in explained variance (Δ R2 = 0.01, p = 0.037) and, for this reason, we interpreted this third model as indicated below.

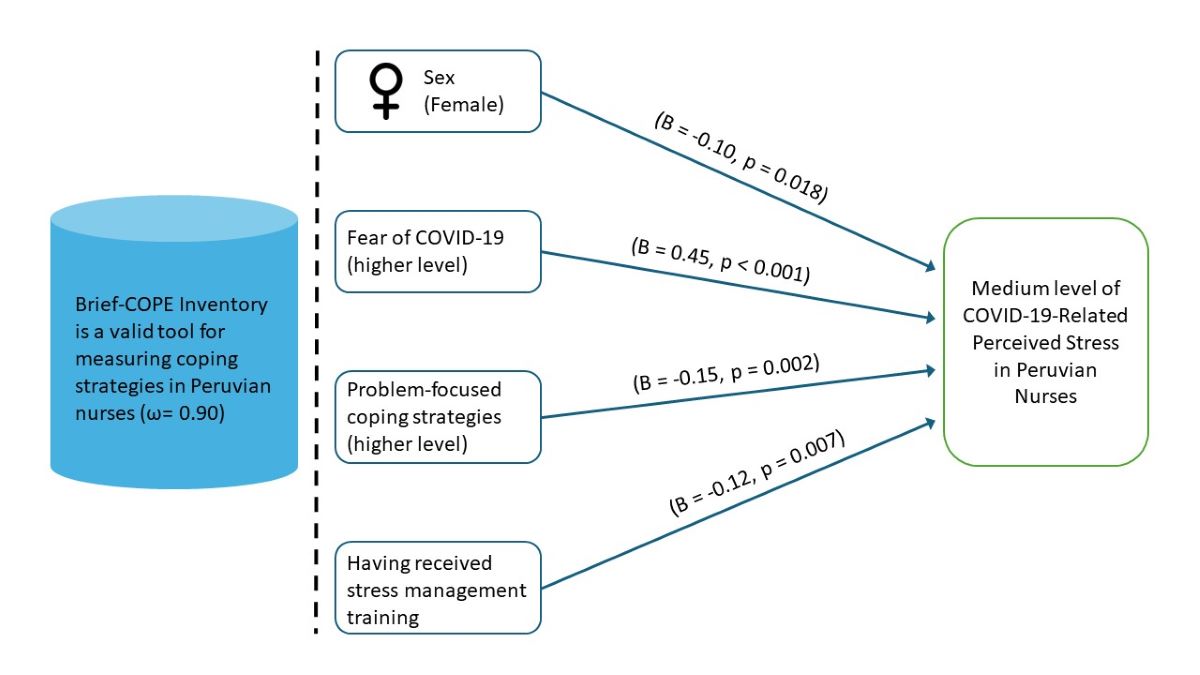

In this model, we identified that, as participants were older, their perceived stress significantly decreased (B = -0.15, p = 0.026). Similarly, we observed that men showed lower levels of perceived stress than women did (B = -0.10, p = 0.018). In addition, people who had received stress management training had lower levels of perceived stress than those who had not (B = -0.12, p = 0.007). We also noted that participants who showed higher levels of fear of COVID-19 also showed higher levels of perceived stress (B = 0.45, p < 0.001). Lastly, participants who reported higher levels of problem-focused coping also reported lower perceived stress scores (B = -0.15, p = 0.002).

Figure 1 shows

Table 3 shows the stepwise regression models estimated for the prediction of the perceived stress dimension Stress perception. Specifically, we can see that the first model including only the sociodemographic variables showed explained 3% of variance (R2 = 0.03, p = 0.005). Then, the model in which we entered the fear of COVID-19 predictor presented a 25% increase in explained variance (Δ R2 = 0.28, p < 0.001). Finally, the model including coping strategies did not reveal a significant increase in explained variance (Δ R2 = 0.00, p = 0.341). Therefore, we interpreted the model of the second step, without coping strategies.

In the model of the second step, we identified that, as participants were older, stress perception decreased significantly (B = -0.14, p = 0.032). Similarly, men reported lower levels of stress perception than women did (B = -0.12, p = 0.004). Finally, we observed that participants who reported higher levels of fear of COVID-19 also showed higher levels of perceived stress (B = 0.50, p < 0.001). No other variable was shown to have significant predictive effects on perceived stress.

Table 4 shows the stepwise regression models estimated to predict the perceived stress dimension Stress coping. It can be observed that the first model explained 3% of variance (R2 = 0.03, p = 0.012). The second model, in which we included fear of COVID-19 as a predictor, increased explained variance by only 4% (Δ R2 = 0.04, p < 0.001). The third model, in which we entered coping strategies, also increased explained variance by 4% (Δ R2 = 0.04, p < 0.001). Considering this result, we interpreted this third model.

Particularly, this model showed that nurses working in the emergency department reported higher levels of stress coping than those working in the intensive care unit (B = 0.11, p = 0.047). Similarly, those who had received stress management training had higher levels in the stress coping dimension than their counterparts who had not received such training (B = -0.11, p = 0.015). Likewise, participants who reported higher levels of fear of COVID-19 showed lower levels of stress coping (B = -0.21, p < 0.001). Lastly, participants who reported higher levels of problem-focused coping also showed higher scores on the stress coping dimension (B = 0.21, p < 0.001). We observed no other significant effects in the present model.

4. Discussion

This study provides important evidence of the adequate psychometric properties of the BCI in a sample of Peruvian nurses. It demonstrates concurrent validity because of the association found with perceived stress, thus providing substantial support for its use in assessing coping strategies in this population. This finding is consistent with previous studies that have validated BCI with different populations and contexts, including healthcare professionals in Italy [

15] and family caregivers in the United Kingdom [

23], as well as specific stressful contexts such as the COVID-19 pandemic [

1].

The CFA supported the presence of three factors or dimensions of the inventory: Problem-focused coping, Emotion-focused coping, and Avoidance coping. This finding is in line with the theory underlying the coping model of Folkman and Lazarus [

12], as well as with the distinctions proposed by Carver et al. [

13] regarding how coping strategies are used. However, it differs from other studies where different dimensions of coping strategies have been found [

1,

15]. These differences between studies conducted in different contexts suggest that coping strategies are strongly dependent on cultural and contextual factors, which makes studies such as the present one necessary to have context-specific validated instruments.

In the same vein, it is important to note that the confirmatory model showed a good fit only when the residual variances of three items related to religion as a coping strategy were correlated. This finding suggests that religion may play a crucial role in stress coping among Peruvian nurses, which is consistent with previous studies that have highlighted the importance of religion and spirituality in stress coping among various populations [

5,

35,

36]. Overall, these studies indicate that religion can provide emotional support, meaning, and a sense of resilience that help nurses cope with perceived stress and thrive in their profession. However, it is important to note that these items had significant and strong factor loadings on the emotion-focused coping factor, demonstrating a correlation between spirituality and emotions as a coping mechanism.

Similarly, the association between stress and coping strategies reported in this study is consistent with several studies conducted among nurses in Korea [

37] and China [

38], nursing students in Colombia [

3], and people in general in China [

39]. Moreover, the regression analysis showed that participants with higher levels of problem-focused coping had lower stress scores, which is in line with a study conducted with nurses working in psychiatric hospitals in Egypt [

40]. This indicates that if nursing professionals cope with and actively solve stressors, their stress levels could be significantly reduced [

38].

The other predictors of perceived stress found in the regression analysis were sex, having received stress management training (which only explained 5% of the variance), and fear of COVID-19. These findings are consistent with numerous studies reporting associations between stress and sex [

7] and stress and fear [

41,

42,

43]. But contrasts with a study that report that sex is not a predictor of stress in nurses [

44]. These associations show the need to target educational interventions towards nurses who report high levels of fear. Programs aimed at strengthening the ability to cope with stress through the use of various self-management techniques and cognitive strategies would help enhance nurse participation and establish protocols for stress prevention. In addition, it would allow nurses to adopt a proactive and positive attitude to directly address stressors.

Assessing health professionals’ perceived stress and coping skills is of great importance from a neuroscience and mental health perspective. Numerous scientific studies have demonstrated that the work environment of health professionals, such as physicians and nurses, is associated with high levels of stress attributed to the demands and pressure of patient care and critical decision-making during crisis situations [

37,

38]. Consequently, a thorough and current assessment of these factors can offer valuable insights into the emotional well-being and coping skills of such professionals, which may significantly impact the quality of patient care they provide and their own mental health and well-being.

Perceived stress related to the COVID-19 pandemic has been a significant factor in health professionals’ lives, particularly frontline nurses. Assessing coping strategies and their associated factors among these professionals is critical to understanding how they deal with the challenges of this unusual context. Therefore, designing and validating a psychometrically sound scale may have significant implications for psychology and nursing practice.

This study has some limitations. First, given that data were collected through self-reporting, the results could be affected by common method and social desirability bias, thus requiring that the reported findings be verified by additional studies. The second limitation of this study is that by using non-probability sampling, the study results cannot be generalized to the entire Peruvian population. Finally, since we only performed the CFA based on a theoretical framework, other studies are required to confirm this structure in studies that consider different samples.

5. Conclusions

This psychometric study demonstrated that a three-factor BCI is a valid tool to measure coping strategies in Peruvian nurses. It showed an adequate fit to the model (RMSEA = 0.052, SRMS = 0.068, CFI = 0.95, and TLI = 0.95), excellent reliability (ώ = 0.90), and concurrent validity with perceived stress.

Nursing professionals reported medium levels of perceived stress. Regarding the predictive model, the first analysis (5% of explained variance) found sex and stress management training to be predictor variables. Likewise, in the second analysis (26% of explained variance), fear of COVID-19 and professional experience were also found to be predictors. Lastly, in the third analysis (27% of explained variance), the problem-focused coping strategies score was reported as a predictor factor.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.A.Z., C.C.F., O.M. and S.C.B.; methodology, S.C.B., T.J.V., H.C., S.H.A., O.M. and R.Z.; validation, C.C.F., T.J.V., H.C. and S.H.R.; formal analysis, E.F.; investigation, J.A.Z., C.C.F. and S.C.B.; data curation, J.A.Z. and E.F.; Resources, R.Z.; Visualization, R.Z.; writing—original draft preparation, J.A.Z., S.C.B., and E.F.; writing—review and editing, E.F., T.J.V., H.C., S.H.A., O.M. and R.Z.; project administration, J.A.Z. and R.Z. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was financed by the authors themselves.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The Ethics and Research Committee of the School of Medicine of the Universidad Nacional Mayor de San Marcos approved the study (Minutes No. 065-2020). Before answering the questionnaire, each participant gave their free and informed consent. To protect the privacy of the information and give the researchers exclusive access to the data, the survey data were coded to remove any identifying information.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained online from all study participants.

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Abdul Rahman, H.; Bani Issa, W.; Naing, L. Psychometric properties of brief-COPE inventory among nurses. BMC Nurs. 2021, 20, 73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robertson, H.D.; Elliott, A.M.; Burton, C.; Iversen, L.; Murchie, P.; Porteous, T.; Matheson, C. Resilience of primary healthcare professionals: a systematic review. Br. J. Gen. Pract. 2016, 66, e423–e433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bohórquez Moreno, C.; Hernández-Escolar, J.; Muvdi Muvdi, Y.; Malvaceda Frías, E.; Mendoza Sánchez, X.; Madero Zambrano, K.; Asociación entre estrés percibido y estrategias de afrontamiento en estudiantes de enfermería en tiempos de COVID-19. Metas enferm. 2022. Available online: https://www.enfermeria21.com/revistas/metas/articulo/81942/ (accessed on 18 July 2024).

- Muvdi Muvdi, Y.; Malvaceda Frías, E.; Barreto Vásquez, M.; Madero Zambrano, K.; Mendoza Sánchez, X.; Bohorquez Moreno, C. Estrés percibido en estudiantes de enfermería durante el confinamiento obligatorio por Covid-19. Rev. Cuid. 2021, 12, e1330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omar, D.I.; Amer, S.A.; Abdelmaksoud, A.E. Fear of COVID-19, Stress and Coping Strategies among Nurses during the COVID-19 Pandemic's Second Wave: A Quasi-Intervention Study. Clin. Pract. Epidemiol. Ment. Health 2023, 19, e174501792212200 https://. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velasco Yanez, R.J.; Cunalema Fernández, J.A.; Franco Coffre, J.A.; Vargas Aguilar, G.M. Estrés percibido asociado a la pandemia por COVID-19 en la ciudad de Guayaquil, Ecuador. Bol. Malariol. Salud Ambient. 2021, 38–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olórtegui-Yzú, A.; Vega-Dienstmaier, J.M.; Fernández-Arana, A. Relationship between depression, anxiety, and perceived stress in health professionals and their perceptions about the quality of the health services in the context of COVID-19 pandemic. Brain Behav. 2023, 13, e2816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández-Martín, F.D.; Flores-Carmona, L.; Arco-Tirado, J.L. Coping Strategies Among Undergraduates: Spanish Adaptation and Validation of the Brief-COPE Inventory. Psychol. Res. Behav. Manag. 2022, 15, 991–1003 https://. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Folkman, S.; Moskowitz, J.T. Coping: pitfalls and promise. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2004, 55, 745–774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazarus, R.S. Coping theory and research: past, present, and future. Psychosom. Med. 1993, 55, 234–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandín, B. El estrés: un análisis basado en el papel de los factores sociales. Int. J. Clin. Health Psychol. 2003, 3, 141–157. [Google Scholar]

- Folkman, S.; Lazarus, R.S. An Analysis of Coping in a Middle-Aged Community Sample. J. Health Soc. Behav. 1980, 21, 219–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carver, C.S.; Scheier, M.F.; Weintraub, J.K. Assessing coping strategies: a theoretically based approach. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1989, 56, 267–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meyer, B. Coping with Severe Mental Illness: Relations of the Brief COPE with Symptoms, Functioning, and Well-Being. J. Psychopathol. Behav. Assess. 2001, 23, 265–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bongelli, R.; Fermani, A.; Canestrari, C.; Riccioni, I.; Muzi, M.; Bertolazzi, A.; Simonetti, C.; Zimbaro, G.; Romaniello, C.; Nardi, B.; et al. Italian validation of the situational Brief Cope Scale (I-Brief Cope). PLoS One 2022, 17, e0278486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Monzani, D.; Steca, P.; Greco, A.; D'Addario, M.; Cappelletti, E.; Pancani, L. The Situational Version of the Brief COPE: Dimensionality and Relationships With Goal-Related Variables. Eur. J. Psychol. 2015, 11, 295–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Folkman, S.; Lazarus, R.S. Manual for the ways of coping questionnaire; Consulting Psychologists Press: Palo Alto, CA, USA, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Reid, G.J.; Gilbert, C.A.; McGrath, P.J. The Pain Coping Questionnaire: preliminary validation. Pain 1998, 76, 83–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Endler, N.S.; Parker, J.D. Multidimensional assessment of coping: a critical evaluation. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1990, 58, 844–854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Endler, N.S.; Parker, J.D.A. Assessment of multidimensional coping: Task, emotion, and avoidance strategies. Psychol. Assess. 1994, 6, 50–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohanraj, R.; Jeyaseelan, V.; Kumar, S.; Mani, T.; Rao, D.; Murray, K.R.; Manhart, L.E. Cultural adaptation of the Brief COPE for persons living with HIV/AIDS in southern India. AIDS Behav. 2015, 19, 341–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, X.Y.; Lau, J.T.; Mak, W.W.; Choi, K.C.; Feng, T.J.; Chen, X.; Liu, C.L.; Liu, J.; Liu, D.; Chen, L.; et al. A preliminary validation of the Brief COPE instrument for assessing coping strategies among people living with HIV in China. Infect. Dis. Poverty 2015, 4, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooper, C.; Katona, C.; Livingston, G. Validity and reliability of the brief COPE in carers of people with dementia: the LASER-AD Study. J. Nerv. Ment. Dis. 2008, 196, 838–843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kline, R.B. Principles and Practice of Structural Equation Modeling, 4th ed.; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Hernández-Nieto, R.; Pulido, M.J.E. Instrumentos de Recolección de Datos en Ciencias Sociales y Ciencias Biomédicas: Validez y Confiabilidad. Diseño y Construcción. Normas y Formatos; Universidad de Los Andes: Mérida, Venezuela, 2011; 370p. [Google Scholar]

- Flores Rodríguez, C.C. Estrategias de afrontamiento al estrés de los profesionales de enfermería que laboran en hospitales de Lima y Callao en tiempos de pandemia COVID 19, 2021. Universidad Nacional Mayor de San Marcos: Lima, Peru, 2023. Available online: https://cybertesis.unmsm.edu.pe/handle/20.500.12672/19393 (accessed on 1 August 2023).

- Huarcaya-Victoria, J.; Villarreal-Zegarra, D.; Podestà, A.; Luna-Cuadros, M.A. Psychometric Properties of a Spanish Version of the Fear of COVID-19 Scale in General Population of Lima, Peru. Int. J. Ment. Health Addict. 2020, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zeladita-Huaman, J.A.; Zegarra-Chapoñan, R.; Castro-Murillo, R.; Surca-Rojas, T.C. Worry and fear as predictors of fatalism by COVID-19 in the daily work of nurses. Rev. Latino-Am. Enfermagem 2022, 30, e3605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campo-Arias, A.; Pedrozo-Cortés, M.J.; Pedrozo-Pupo, J.C. Escala de estrés percibido relacionado con la pandemia de COVID-19: una exploración del desempeño psicométrico en línea. Rev. Colomb. Psiquiatr. 2020, 49, 229–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Becerra-García, J.A.; Valdivieso, I.; Barbeito, S.; Calvo, A.; Sánchez-Gutiérrez, T. Psychometric properties of the COVID-19 related Perceived Stress Scale online version in the Spanish population. J. Affect. Disord. Rep. 2024, 15, 100716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campo-Arias, A.; Pedrozo-Pupo, J.C.; Herazo, E. Review of the COVID-19 Pandemic-related Perceived Stress Scale (PSS–10–C). Rev. Colomb. Psiquiatr. 2021, 50, 156–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Byrne, B.M. Factor Analytic Models: Viewing the Structure of an Assessment Instrument From Three Perspectives. J. Pers. Assess. 2005, 85, 17–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Worthington, R.L.; Whittaker, T.A. Scale Development Research: A Content Analysis and Recommendations for Best Practices. Couns. Psychol. 2006, 34, 806–838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- R Core Team. R: The R Project for Statistical Computing. 2022. Available online: https://www.r-project.org/ (accessed on 18 July 2024).

- Bakibinga, P.; Vinje, H.F.; Mittelmark, M. The Role of Religion in the Work Lives and Coping Strategies of Ugandan Nurses. J. Relig. Health 2014, 53, 1342–1352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yiin, J.J.; Chen, Y.Y.; Lee, K.C. Fatigue and Vigilance-Related Factors in Family Caregivers of Patients With Advanced Cancer: A Cross-sectional Study. Cancer Nurs. 2022, 45, E621–E627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jang, M.H.; Gu, S.Y.; Jeong, Y.M. Role of Coping Styles in the Relationship Between Nurses' Work Stress and Well-Being Across Career. J. Nurs. Scholarsh. 2019, 51, 699–707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, Y.; Guo, X.; Yin, H. A structural equation model of the relationship among occupational stress, coping styles, and mental health of pediatric nurses in China: a cross-sectional study. BMC Psychiatry 2022, 22, 416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xue, P.; Zhang, Y.; Wei, F.; Zhou, L.; Fang, X.; Hu, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Ji, W.; Wu, L.; Xu, Y.; et al. Associations of Occupational Stress and Coping Styles with Well-Being Among Couriers — Three Cities, Zhejiang Province, China, 2021. China CDC Wkly. 2023, 5, 446–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hasan, A.A.; Elsayed, S.; Tumah, H. Occupational stress, coping strategies, and psychological-related outcomes of nurses working in psychiatric hospitals. Perspect. Psychiatr. Care 2018, 54, 514–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- D'emeh Waddah Mohammad; Yacoub, M. I.; Shahwan, B.S. Work-Related Stress and Anxiety Among Frontline Nurses During the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Cross-Sectional Study. J. Psychosoc. Nurs. Ment. Health Serv. 2021, 59, 31–42. [CrossRef]

- Ekingen, E.; Teleş, M.; Yıldız, A.; Yıldırım, M. Mediating effect of work stress in the relationship between fear of COVID-19 and nurses' organizational and professional turnover intentions. Arch. Psychiatr. Nurs. 2023, 42, 97–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Galletta, M.; Piras, I.; Finco, G.; Meloni, F.; D'Aloja, E.; Contu, P.; Campagna, M.; Portoghese, I. Worries, Preparedness, and Perceived Impact of Covid-19 Pandemic on Nurses' Mental Health. Front. Public Health 2021, 9, 566700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeladita-Huaman, J.A.; Cruz-Espinoza, S.L.D.L.; Samillán-Yncio, G.; Castro-Murillo, R.; Franco-Chalco, E.; Zegarra-Chapoñan, R. Perceptions, maltreatment and religion as predictors of the psycho-emotional impact on nurses during the COVID-19 pandemic. Rev. Bras. Enferm. 2023, 76, e20220768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).