1. Introduction

Corticosteroids (CSs) play an important role in managing a variety of medical illnesses, particularly those involving inflammation and immune-mediated disorders [

1,

2]. CSs exert the pharmacological effect by reducing symptoms, easing disease severity, and improving the quality of life [

3]. However, it is critical to recognize the hazards associated with the long-term utilization of corticosteroids, mainly infections, osteoporosis, hyperglycemia, cardiovascular diseases, and immunosuppression [

1,

4]. It is extremely integral to assess the therapeutic benefits with the potential dangers before prescribing corticosteroids in clinical practice [

2]. To achieve the appropriate and professional decision, corticosteroids must be prescribed and monitored with caution through choosing the right drug, correct dosage, and appropriate duration. Healthcare providers must critically evaluate individual patient's past and present medical history, and other pertinent considerations [

5]. Furthermore, regular monitoring of side effects and adjusting the treatment plan accordingly are crucial to mitigate potential harm.

Awareness of corticosteroid dosage recommendations and associated dangers among patients and healthcare professionals is critical for achieving optimal therapeutic benefits. Structured communication, tailored education, and collaboration between patients and healthcare providers contribute to safer and more successful therapeutic strategies in medical practice [

5,

6]. For an effective administration of corticosteroid drugs, effective collaboration and integration between physicians and pharmacists play an integral and complementary role in improving medical practice with minimal toxicity [

7]. Physicians provide the clinical knowledge and expertise in prescribing, monitoring, and changing treatment plans, while pharmacists contribute to dispensing appropriate medications, raising patient education, and enhancing the reporting of drug interactions [

8,

9]. This joint effort assures comprehensive care and improves patient outcomes. Accordingly, continuing education and professional development are essential for healthcare professionals to advance their expertise and keep abreast of medical practices [

10]. This continuous commitment to learning ensures delivery of the best treatment standard with exposure to minimal adverse effects associated with the use of corticosteroids [

11,

12].

Assessing physicians’ awareness and experience can shed light on the current prescribing practices [

13]. Understanding the challenges or misunderstandings provides a valuable tool to guide future actions that are targeted at increasing prescription accuracy, appropriateness, and adherence to recommendations. This strategy serves as a foundational direction to conduct targeted educational efforts, which leads to improved practices, strengthened confidence, and enhanced patient outcomes in the context of corticosteroid prescribing and dispensing [

14,

15]. In a study based on population data, less than one-third of patients received regular clinical and biological monitoring prior to initiating CS, indicating a deficiency in prescribers' awareness of potential risks [

16]. On the other hand, Kang et al. noted that Korean community pharmacists possess ample knowledge and awareness to advise patients on the proper usage of CS [

17]. In contrast, an Egyptian study revealed that pharmacists possess insufficient knowledge and defective practices concerning CS in asthma management [

18].

Additionally, assessing fear or concerns about prescribing and dispensing corticosteroids is important for understanding the psychological barriers that healthcare professionals may face [

5]. This information can guide the development of supportive resources and strategies to alleviate concerns and build confidence. However, the scarcity and inconsistent nature of existing research addressing the perceptions of healthcare workers about CS reveal a significant gap in the literature, which has the potential to impair the safe and effective use of these drugs in clinical practice. By addressing these considerations and given the scarcity of data offering a full assessment of knowledge, experience, and fears regarding CS among healthcare workers, this research endeavors aimed to assess the knowledge, experiences, and fear towards prescribing corticosteroids among Jordanian healthcare physicians.

2. Materials and Methods

An online questionnaire was employed in this cross-sectional investigation. Data was gathered between March and August 2023, using social media such as Facebook, LinkedIn, and WhatsApp. The questionnaire was intended to be a self-administered tool. Any licensed physician who practices in Jordan and is willing to answer the questionnaire is eligible to participate. Participation was anonymous and entirely optional. Each participant received study details at the beginning of the questionnaire, along with an online consent form to complete if they wished to proceed with the questionnaire. The Faculty of Pharmacy, Applied Science Private University, Amman, Jordan's Institutional Review Board (or Ethics Committee) has obtained ethical approval (Approval number: 2022-PHA-24).

2.1. Sample size

The sample size has been calculated using Open-Source Epidemiologic Statistics for Public Health (OpenEpi) Version 3.01, with a margin of error of 5% and a confidence level of 90%. The approach of practical snowball sampling was employed to recruit participants. For this study, considering that there are 42,364 registered physicians in Jordan [

20] and a 95% confidence interval, the minimal sample size needed is 170 participants [

19].

2.2. Study Tool

The study questionnaire was developed utilizing the essential principles for efficient survey design [

21],and based upon previous validated surveys in the literature [

22,

23,

24,

25]. Combining data from multiple sources resulted in a pool of questions relevant to the objectives of the study. Five academics assessed the content validity of the study tool prepared in English. The questionnaire was piloted on 10 participants (physicians) to ensure the clarity of all items, and linguistic adjustments were made as necessary based on the participants' feedback. The final analyses did not take the pilot responses into account. Then, the final version of the questionnaire was distributed electronically. Cronbach's alpha was also checked (=0.85), accordingly the scale's reliability and internal consistency were confirmed.

The questionnaire comprised four sections with multiple choice questions: section I comprised of sociodemographic characteristics (5 questions), section II included the assessment of knowledge about CS (11 questions), section III covered the experience with CS prescription (5 questions), and section IV assessed fears and preferences toward CS prescription (10 questions).

Regarding the 11 knowledge assessment items were used to compute the cumulative knowledge score. Physicians received 1 point for each correct answer and 0 points for each incorrect answer, resulting in a knowledge score that can range from 0 to 11. Additionally, participants' responses regarding the fear score were documented using a Likert scale with a maximum of five points, with options including "strongly disagree" (1), "disagree" (2), "neutral" (3), "agree" (4), and "strongly agree" (5).

2.3. Statistical Analyses

Data were extracted from Google Forms as an Excel sheet and were then exported to Statistical Package for Social Sciences version 25.0 (IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, version 25 (IBM Corp., Armonk, N.Y., USA) for statistical analysis. The descriptive analyses were conducted using median and Interquartile Range (IQR) for continuous variables and frequency and percentages for categorical variables. Univariate linear regression analysis investigated independent factors that may affect the participants’ knowledge and fears about CS. Variables were selected after checking their independence, where tolerance values > 0.1 and Variance Inflation Factor (VIF) values < 10 were checked to indicate the absence of multicollinearity between the independent variables in regression analysis. Variables that were found to be significant on a single predictor level (p < 0.25) were entered into multiple linear regression analyses. None of the included variables showed multicollinearity; thus, none was eliminated. Statistical significance was considered at p ≤ 0.05.

3. Results

3.1. Sociodemographic Characteristics of the Study Participants

In this research, 171 physicians volunteered to participate. Their median age was 31.0 years, with an interquartile range of 8.0. Most were male, accounting for 105 individuals (61.4%), and nearly two-thirds were working in central Jordan, totaling 111 participants (64.9%). In terms of their medical specialties, approximately one-third of the physicians were general practitioners (GPs) (n= 64, 37.4%), while 12.3% of them were family medicine specialists (n= 21). Further information on their sociodemographic characteristics can be found in

Table 1.

3.2. Physicians’ Experience with Prescribing Corticosteroids

Regarding the experience of physicians in prescribing CS, as indicated in

Table 2, a significant majority of them, totaling 148 individuals (86.5%), reported having such experience. Among those who had dispensed CS, the most frequently prescribed dosage form was topical (123 out of 148, 83.1%), followed by injectable forms (121 out of 148, 81.8%). Furthermore, the primary reasons for physicians prescribing CS were related to treating respiratory diseases (129 out of 148, 87.2%), followed by dermatological conditions (122 out of 148, 82.4%). Additionally, the most prevalent side effects of CS experienced by patients, as reported by the physicians, included diabetes (84 out of 148, 56.8%), increased appetite (82 out of 148, 55.4%), and high blood pressure (62 out of 148, 41.9%).

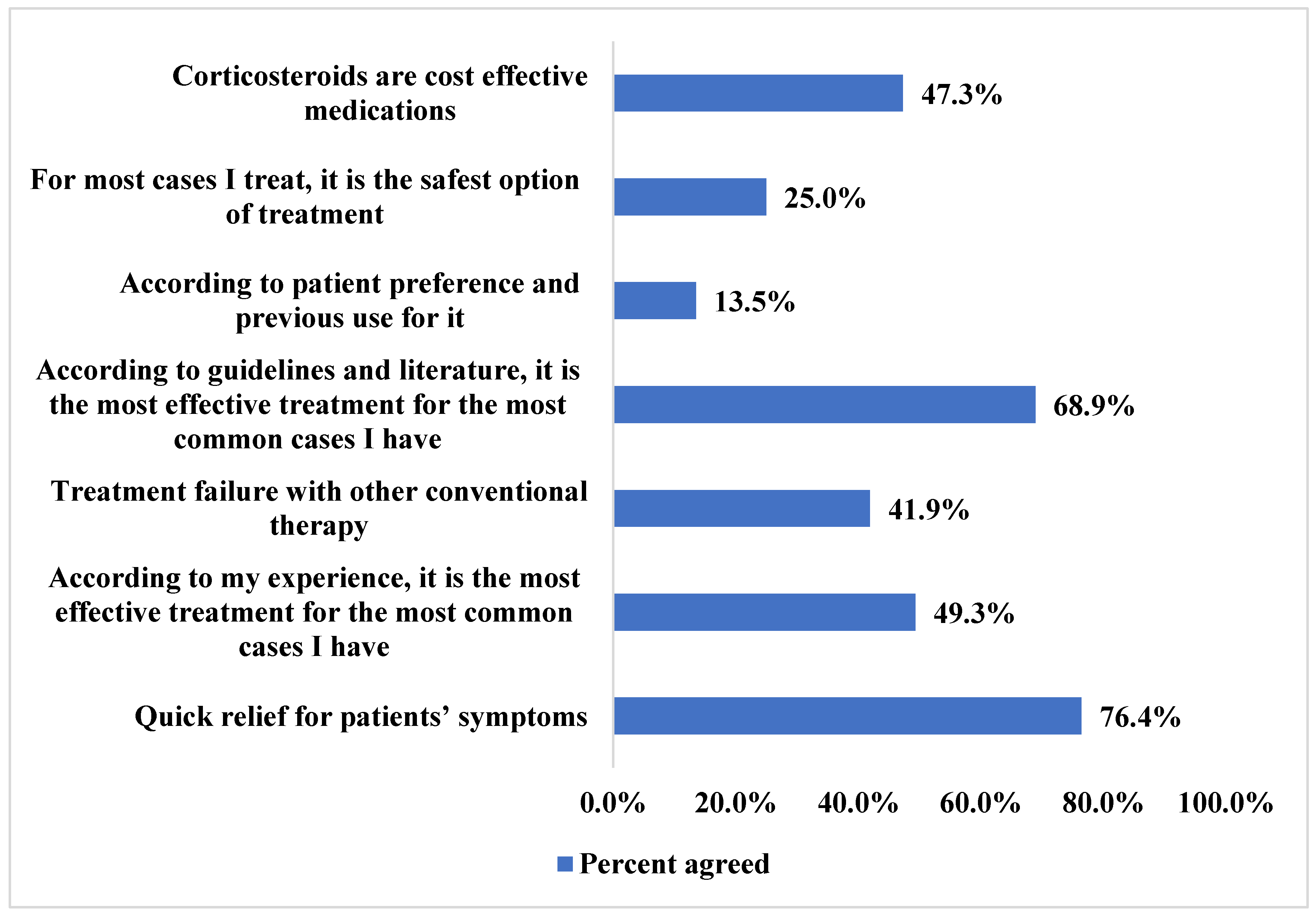

Physicians reported the main reasons for choosing to prescribe CS to their patients. First and foremost, the ability of CS to rapidly alleviate patients' symptoms was a major factor, with 113 out of 148 physicians (76.4%) identifying this as a key consideration. Additionally, many physicians noted that CS were deemed the most effective treatment options for their patients' conditions, aligning with recommendations found in treatment guidelines, as reported by 102 out of 148 physicians (68.9%). Additional reasons can be found in

Figure 1.

3.3. Physicians’ Knowledge about Corticosteroids

Overall, physicians demonstrated a high level of knowledge about CS, as indicated in

Table 3. Their median knowledge score was 11.0 out of a maximum of 11.0, with an IQR of 1.0. The majority of physicians were well-informed, with 170 out of 171 (99.4%) correctly recognizing that CS can lead to weight gain. Additionally, 168 out of 171 physicians (98.2%) were aware that prolonged treatment with high doses of CS could pose problems for certain individuals. Furthermore, 167 out of 171 (97.7%) understood that when discontinuing long-term CS use, the doses should be reduced gradually over several weeks or months.

3.4. Physicians’ Fears toward Corticosteroids Prescribing

Physicians displayed a high fear score with a median score of 3.5 out of a possible 5.0 (IQR= 0.8) concerning the prescribing of CS, as shown in

Table 4. The primary concerns that physicians had when it came to prescribing CS were related to the risk of osteoporosis in their patients, with 126 out of 171 (73.7%) expressing this fear, as well as the risk of hyperglycemia, which was a concern for 114 out of 171 (66.7%) physicians. Additionally, physicians were apprehensive about the potential risk of elevated blood pressure among their patients, with 108 out of 171 (63.2%) indicating this as a source of fear.

3.5. Predictors of Factors Affecting Physicians’ Knowledge about Corticosteroids

The regression analysis conducted to assess the factors influencing physicians' knowledge about CS, as presented in

Table 5, revealed that none of the examined sociodemographic factors (including age, gender, site of work, and location of work) had a significant impact on physicians' knowledge about CS.

3.6. Predictors of Factors Affecting Physicians’ Fears towards Corticosteroids

Furthermore, the regression analysis conducted to examine the factors affecting physicians' fears of CS, as shown in

Table 6, indicated that none of the sociodemographic factors under consideration (such as age, gender, site of work, and location of work) had a significant influence on physicians' fear of CS.

4. Discussion

This cross-sectional study is the first of its kind to assess the knowledge, experiences, and fear of prescribing corticosteroids among Jordanian healthcare physicians. This approach allowed any licensed physician to participate in the study, which helped provide a broad spectrum of viewpoints, perspectives, and experiences.

The results showed that more than 86% of the doctors had prescribed corticosteroids in the form of topical preparations, injections, inhalers, tablets, and, to a lesser extent, drops. This indicates that most of the participating physicians were exposed to corticosteroids during their work and thus must have information about these medications’ indications, dosage, and possible side effects.

These medications were mostly prescribed for respiratory and dermatological conditions. This is similar to what was reported in a study conducted in Egypt, where the most common reasons to prescribe corticosteroids were dermatological or respiratory conditions [

5]. Additionally, in a study conducted in the Republic of Kosovo, it was found that corticosteroids were mostly prescribed to treat allergies, urticaria, atopic dermatitis and bronchial asthma [

26]. Moreover, in a study conducted in the United States to explore the short-term use of corticosteroids, it was found that upper respiratory tract infections, spinal conditions, and allergies were the most common indications for the prescription of corticosteroids [

27]. Similarly, respiratory diseases were the most frequently recorded indication for oral corticosteroid treatment, as found in a study conducted in the United Kingdom [

28].

The prescription of topical preparations of corticosteroids was found to be the most commonly prescribed dosage form in the Republic of Kosovo [

26], similar to the findings of this study. Additionally, topical or inhalational dosage forms were found to be the most commonly prescribed dosage forms in Egypt [

5]. In this study, the side effects reported by the patients to the physicians in Jordan were increased appetite, hyperglycemia, and hypertension. Increased appetite, mood changes, swings, and depression were reported as the most common side effects noted by COVID-19 patients who were treated with corticosteroids in six Arab countries, including Egypt, Iraq, Jordan, Saudi Arabia, Sudan, and Syria [

6]. However, in Egypt, physicians reported an increased risk of infection and hypertension as the most noted side effects of corticosteroids that their patients suffered from [

5]. Similarly, in the United States, it was reported that the use of corticosteroids was linked with an increase in the rates of sepsis, venous thromboembolism, and fracture [

27].

The physicians participating in this study stated that corticosteroids effectively treated their patients’ complaints and/or were the drug of choice, as stated in the guidelines. Similar findings were reported by physicians in Egypt [

5], and the physicians in the Republic of Kosovo [

26], who reported that treatments with corticosteroids were successful.

The physicians participating in this study showed high knowledge regarding corticosteroids as the median knowledge score was 11 out of 11, with an IQR of 1.0. Physicians were also found to have good knowledge regarding corticosteroids in studies conducted in Egypt [

5,

6] and Iraq [

6], unlike the physicians in Saudi Arabia [

6,

10] and in Maiduguri, which is in North-eastern Nigeria [

29], where physicians were found to have inadequate knowledge about corticosteroids.

In this study, osteoporosis, hyperglycemia and hypertension were the most common side effects that the physicians feared when prescribing corticosteroids. Adrenal insufficiency, hyperglycemia and hypertension were also reported as the main reasons that physicians in Egypt feared prescribing corticosteroids to their patients [

5]. Physicians in the Republic of Kosovo [

26] were also found to have concerns when prescribing corticosteroids regardless of its efficiency. These results are also in accordance with the findings that around 40% of the doctors in the Republic of Macedonia have concerns regarding the use of topical corticosteroids [

30].

The results of this study showed that although Jordanian physicians fear the side effects of corticosteroids, they are willing to prescribe them to their patients if they are the treatment of choice to alleviate their patients’ complaints. They also know about these medications’ indications, proper use, and side effects, regardless of age, gender, specialty, and practice location. This high knowledge can be since physicians in Jordan are required to engage in continuing professional development (CPD) education in order to renew their license every five years, which helps them to keep their medical information up to date [

31].

5. Conclusions

This cross-sectional study sheds light on Jordanian healthcare physicians' knowledge, experiences, and fears regarding corticosteroid prescriptions. With a diverse sample, the study reveals a prevalent use of corticosteroids, primarily for respiratory and dermatological conditions. Despite the high fears of side effects, including osteoporosis, hyperglycemia, and hypertension, physicians remain willing to prescribe corticosteroids when deemed the optimal treatment. Moreover, the study underscores the high knowledge level of Jordanian physicians, attributed to mandatory continuing professional development. Finally, this research emphasizes the critical role of ongoing medical education in fostering physicians' confidence and knowledge. The insights gained can inform targeted interventions to address concerns and optimize corticosteroid use in Jordan's healthcare landscape.

Author Contributions

Muna Barakat: Concept and Design, Data Acquisition, Data Analysis, Manuscript Drafting, Approval of Final Version. Rana Abu-farha: Concept and Design, Data Acquisition, Data Analysis, Manuscript Drafting, Approval of Final Version. Samar Thiab: Concept and Design, Data Acquisition, Data Analysis, Manuscript Drafting, Approval of Final Version. Nesreen Salim: Data Acquisition, Manuscript Drafting, Approval of Final Version. Anas O. Alshweiki: Concept and Design, Data Acquisition, Manuscript Drafting, Approval of Final Version. Diana Malaeb: Manuscript Drafting, Approval of Final Version. Malik Salam: Manuscript Drafting, Approval of Final Version. Roa'a Thaher: Data Acquisition, Data Analysis, Manuscript Drafting, Approval of Final Version.

Funding

The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Institutional Review Board (or Ethics Committee) of Faculty of Pharmacy, Applied Science Private University, Amman, Jordan (Approval number:2022-PHA-24)

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data will be made available by the corresponding author upon request.

Acknowledgments

In this section, you can acknowledge any support given which is not covered by the author contribution or funding sections. This may include administrative and technical support, or donations in kind (e.g., materials used for experiments).

Conflicts of Interest

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

References

- Liu D, Ahmet A, Ward L, Krishnamoorthy P, Mandelcorn ED, Leigh R, et al. A practical guide to the monitoring and management of the complications of systemic corticosteroid therapy. Allergy, asthma clinical immunology. 2013;9:1-25. Available from: https://aacijournal.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/1710-1492-9-30.

- Hodgens A, Sharman T. Corticosteroids. StatPearls [Internet]: StatPearls Publishing; 2022. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK554612/.

- Mahdy A, Hussain N, Al Khalidi D, Said AS. Knowledge, attitude, and practice analysis of corticosteroid use among patients: A study based in the United Arab Emirates. National Journal of Physiology, Pharmacy Pharmacology. 2017;7(6):562-. Available from: https://www.bibliomed.org/?mno=252653.

- Buchman AL. Side effects of corticosteroid therapy. Journal of clinical gastroenterology. 2001;33(4):289-94. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/11588541/.

- Barakat M, Mansour NO, Elnaem MH, Thiab S, Farha RA, Sallam M, et al. Evaluation of knowledge, experiences, and fear toward prescribing and dispensing corticosteroids among Egyptian healthcare professionals: A cross-sectional study. Saudi Pharmaceutical Journal. 2023;31(10):101777. Available from: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1319016423002724.

- Barakat M, Elnaem MH, Al-Rawashdeh A, Othman B, Ibrahim S, Abdelaziz DH, et al., editors. Assessment of Knowledge, Perception, Experience and Phobia toward Corticosteroids Use among the General Public in the Era of COVID-19: A Multinational Study. Healthcare; 2023: MDPI. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/36673623/#:~:text=Around%2061.9%25%20had%20been%20infected,high%20score%20in%20all%20countries.

- Sami SA, Marma KKS, Chakraborty A, Singha T, Rakib A, Uddin MG, et al. A comprehensive review on global contributions and recognition of pharmacy professionals amidst COVID-19 pandemic: Moving from present to future. Future journal of pharmaceutical sciences. 2021;7(1):119. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/34150911/.

- McGivney MS, Meyer SM, Duncan–Hewitt W, Hall DL, Goode J-VR, Smith RB. Medication therapy management: its relationship to patient counseling, disease management, and pharmaceutical care. Journal of the American Pharmacists Association. 2007;47(5):620-8. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/17848353/.

- Yasir M, Goyal A, Sonthalia S. Corticosteroid adverse effects Internet: Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2018 [updated 2022 Jul 4. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK531462/.

- Alsukait SF, Alshamlan NA, Alhalees ZZ, Alsuwaidan SN, Alajlan AM. Topical corticosteroids knowledge, attitudes, and practices of primary care physicians. Saudi medical journal. 2017;38(6):662. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5541192/.

- Do Nascimento IJB, Pizarro AB, Almeida JM, Azzopardi-Muscat N, Gonçalves MA, Björklund M, et al. Infodemics and health misinformation: a systematic review of reviews. Bulletin of the World Health Organization. 2022;100(9):544. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC9421549/.

- Jose J, AlHajri L. Potential negative impact of informing patients about medication side effects: a systematic review. International Journal of Clinical Pharmacy. 2018;40:806-22. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30136054/.

- Mucklow J, Bollington L, Maxwell S. Assessing prescribing competence. British journal of clinical pharmacology. 2012;74(4):632-9. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3477331/#:~:text=The%20aim%20of%20a%20high,practice%20faced%20by%20the%20candidates.

- Behar-Horenstein LS, Guin P, Gamble K, Hurlock G, Leclear E, Philipose M, et al. Improving patient care through patient-family education programs. Hospital topics. 2005;83(1):21-7. Available from: https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.3200/HTPS.83.1.21-27.

- Marcus C. Strategies for improving the quality of verbal patient and family education: a review of the literature and creation of the EDUCATE model. Health Psychology Behavioral Medicine. 2014;2(1):482-95. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4346059/.

- Fardet L, Petersen I, Nazareth I. Monitoring of patients on long-term glucocorticoid therapy: a population-based cohort study. Medicine. 2015;94(15). Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/25881838/.

- Kang MJ, Park JH, Park S, Kim NG, Kim EY, Yu YM, et al. Community pharmacists’ knowledge, perceptions, and practices about topical corticosteroid counseling: A real-world cross-sectional survey and focus group discussions in Korea. PLoS One. 2020;15(7):e0236797. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7390350/.

- Said AS, Hussain N, Kharaba Z, Al Haddad AH, Abdelaty LN, Hussein RR. Knowledge, attitude, and practice of pharmacists regarding asthma management: a cross-sectional study in Egypt. Journal of pharmaceutical policy practice. 2022;15(1):35. Available from: https://joppp.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s40545-022-00432-0.

- Dean AG SK, Soe MM. OpenEpi: Open Source Epidemiologic Statistics for Public Health, Version 3 2013 [Available from: www.OpenEpi.com.

- Mustafa MI. JMA warns against unlicenced medical centres, syndicate to take legal action. The Jordan Times. 2023.

- Boynton PM. Administering, analysing, and reporting your questionnaire. British Medical Journal. 2004;328(7452):1372-5. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/15178620/.

- Ahmad DS, Wazaify MM, Albsoul-Younes A. the role of the clinical pharmacist in the identification and management of corticophobia–an Interventional Study. Tropical Journal of Pharmaceutical Research. 2014;13(3):445-53. Available from: https://www.ajol.info/index.php/tjpr/article/view/103760.

- Barakat M, Elnaem MH, Al-Rawashdeh A, Othman B, Ibrahim S, Abdelaziz DH, et al. Assessment of Knowledge, Perception, Experience and Phobia toward Corticosteroids Use among the General Public in the Era of COVID-19: A Multinational Study. Healthcare. 2023;11(2):255. PubMed PMID: doi:10.3390/healthcare11020255. Available from: https://www.mdpi.com/2227-9032/11/2/255.

- Choi E, Chandran NS, Tan C. Corticosteroid phobia: a questionnaire study using TOPICOP score. Singapore Medical Journal. 2020;61(3):149. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7905116/.

- El Hachem M, Gesualdo F, Ricci G, Diociaiuti A, Giraldi L, Ametrano O, et al. Topical corticosteroid phobia in parents of pediatric patients with atopic dermatitis: a multicentre survey. Italian journal of pediatrics. 2017 Feb 28;43(1):22. PubMed PMID: 28245844. PMCID: PMC5330138. Epub 2017/03/02. eng Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5330138/#:~:text=Conclusion,of%20TCS%20should%20be%20implemented.

- Behluli E, Nikoloski M, Spahiu L, Dodov MG. Evaluation of attitudes of health care professionals towards the use of corticosteroids in the Republic of Kosovo. Maced Pharm Bull. 2017;63:73-7. Available from: chrome-extension://efaidnbmnnnibpcajpcglclefindmkaj/https://bulletin.mfd.org.mk/volumes/Volume%2063_2/63_2_008.pdf.

- Waljee AK, Rogers MA, Lin P, Singal AG, Stein JD, Marks RM, et al. Short term use of oral corticosteroids and related harms among adults in the United States: population based cohort study. British Medical Journal. 2017;357. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/28404617/.

- Van Staa T-P, Leufkens H, Abenhaim L, Begaud B, Zhang B, Cooper C. Use of oral corticosteroids in the United Kingdom. QJM: An International Journal of Medicine. 2000;93(2):105-11. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/10700481/#:~:text=Over%201.6%20million%20oral%20corticosteroid,and%2079%20years%20of%20age.

- Yerima A, Adamu A, Bakki B, Muhammad M, Amali A, Hassan A. Corticosteroids Use: A survey on the level of knowledge and prescription pattern of doctors in Maiduguri, North-eastern Nigeria. Kanem Journal of Medical Sciences 2021;15(1):65-72. Available from: https://kjmsmedicaljournal.com/publications/issues/kjms_vol15_issue1/151h.pdf.

- Glavas-Dodov M, Simonoska-Crcarevska M, Sulevski V, Raicki RS, Starova A. Assessment of attitudes towards the use of topical corticosteroids among patients, prescribers and pharmacists in the Republic of Macedonia. Macedonian Pharmaceutical Bulletin. 2016;62(1). Available from: chrome-extension://efaidnbmnnnibpcajpcglclefindmkaj/https://bulletin.mfd.org.mk/volumes/Volume%2062/62_002.pdf.

- Younes NA, AbuAlRub R, Alshraideh H, Abu-Helalah MA, Alhamss S, Qanno' O. Engagement of Jordanian physicians in continuous professional development: current practices, motivation, and barriers. International Journal of General Medicine. 2019;24(12):475-83. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/31920365/.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).