1. Introduction

According to a socio-cognitive perspective of individual development and functioning [

1,

6] individual characteristics, environmental characteristics, and behaviors are strictly interconnected with each other in predicting positive or negative developmental pathways. This perspective emphasized the moderating role that individuals’, and youths’, beliefs and reasonings can have in the relation between individual characteristics, such as dispositional susceptibilities, temperamental impairments, or personality vulnerabilities, and the development of maladaptive behavioral responses, such as oppositive, antisocial or aggressive conducts [

2,

4,

7]. Despite this topic was extensively studied in offline contexts within adolescent populations [

8,

9], very few studies examined the role of personal beliefs in the associations between individual susceptibility, irritability, and aggressive behaviors in online contexts [

2,

10] as the relative novelty of the issue. Most of the few existing studies focused their examination on domains of self-efficacy beliefs more related to the extent to which individuals feel capable of using the internet and technological devices, rather than considering the extent to which individuals feel adequately capable of controlling and effortfully orienting their behaviors while they are navigating through social media [

11,

12,

13,

14,

15]. Therefore, the present study aimed to overcome this gap, by investigating the concurrent and differential role of self-regulatory self-efficacy beliefs as mediators of the associations between impulsivity and online/offline aggressive behaviors in adolescent boys and girls, taking into account their gender and their background characteristics.

1.1. Online and Offline Aggressions in Adolescence: Individual and Behavioral Factors

Impulsivity can be defined as a core temperamental and formal characteristic of human functioning that concerns the rapidity/slowness of responding to internal or external stimulation in neutral or provoking conditions, linked to unplanned actions and to lack in the evaluations of consequences of personal actions [

8,

9,

16]. This basic tendency was well documented to be associated with a variety of related behavioral processes, such as risk-taking, inadequate decision-making and problem-solving, high sensation-seeking, and hedonic well-being [

7,

9,

17,

18]. The developmental period of adolescence is of particular interest for this tendency because adolescents are normatively more inclined to engage in risky behavior decisions, their emotional susceptibility increases, and activating self-regulating skills becomes more [

7,

19,

20,

21,

22].

Associations between impulsivity and aggressive behaviors are widely documented [

8,

9,

23,

24]. In particular, cognitive perspectives and

social-information processing models [

25,

26] underlined the importance of cognitive pre-existing hostile schemas that can activate in impulsive children and adolescents as instruments to cope with aroused and ambiguous relational stimuli, that in turn exacerbate their probability to engage in aggressive responses [

16,

27,

28,

29]. Thus, youths who are more inclined to behave impulsively showed many difficulties in evaluating the possible negative consequences of their actions, and they also showed less cognitive and self-regulative abilities to inhibit predominant behavioral responses preferring a more adaptive behavior [

16,

30].

In this scenario, research well established how gender plays a crucial role in individuals’ adaptive or maladaptive behavioral responses [

31,

32,

33]. Young girls tended to express especially covert aggressive behaviors, while young boys tended to show overt and manifested aggression [

8,

27]. These gender differences can be ascribable to the different cognitive processes that each aggressive response leads in people: girls on average are more inclined to evaluate the consequences of their actions before behaving and to experience guilt and shame as negative emotions in response to aggressive behavior, while boys on average are more incline to act the first and immediate behavioral response, due to a higher loss of control over their actions and behaviors, that lead them to behave more impulsively and aggressively than girls [

29,

34].

Mechanisms that connect impulsive tendencies to aggressive behaviors are quite similar in offline and online contexts [

35,

36,

37]. Impulsive tendencies, especially those concerning low control of internal stimuli and impulses, have been firmly linked to high involvement in aggressive and deviant behaviors, offline and online [

10,

17,

30]. According to classical perspectives, impulsivity problems, which pertaining to low self-control, high stimuli sensitivity, the tendency to interpret external stimulation as potentially harmful to the self, and impairments in adaptive emotion and behavioral regulation, may predispose people, especially the younger, to act in a reactive aggressive way, independently from the contexts [

38,

39,

40]. Impulsive people would tend to engage in aggressive behaviors in different offline contexts, such as in academic, work, or relational situations [

30,

41], and this behavioral pattern would replicate similarly in online contexts, such as while navigating on Social Networks [

17,

35,

36]. However, in the light of newer perspectives, such as the

online disinhibition effect theory or communication theories on

computer-mediated-communications [

42,

43], pointed out that online environments have peculiar characteristics that make them different from any other offline environment, such as the potential anonymity of perpetrators, or the a-synchronicity of relational interactions between the perpetrator and the victim/s which did not allow the perpetrator to obtain an immediate response and reward from his/her actions. Therefore, it would be controversial to affirm that impulsivity would play a similar role in predicting offline and online aggressive conduct [

10,

39]. In addition, the limited existing studies that focused on the role of impulsivity in online aggression considered mostly aggressive behaviors related to cyberbullying [

36,

44], and a very limited number of research focused on other forms of online aggression, such as online hate, cyber-stalking, engaging in “shitstorms” (i.e., a collective form of online aggression in which a group of people intentionally planned and leave hateful and aggressive comments directed to a specific individual or social account [

45], online sexual violent harassment [

10], swearing, trolling and flaming [

46].

1.2. The Moderating Role of Self-Regulatory Self-Efficacy Beliefs

Adaptive self-regulative abilities can help youths in modulating and manipulating their experiences, and individuals’ perceptions of their abilities to manipulate and control situations represent one of the most effective determinants of adjustment [

1,

3,

47]. Within the socio-cognitive perspective, Bandura conceptualized these perceptions as self-efficacy beliefs, that represent “dynamic constructs that can be enhanced through mastery experiences as a result of individuals’ capacities to reflect and learn from experience” ([

47] p. 1). Self-efficacy beliefs can orient habits and tendencies, accounting for the proactive role that individuals have in controlling their own lives based on cognitive self-regulation and reflective thinking, which can also influence motivations and goal orientation [

3]. These beliefs help individuals modulate their goal-oriented behaviors when they are exposed to experiences or situations that they feel are challenging [

1,

47]. Consequently, individuals who feel capable of activating their self-regulating abilities have more probability of effectively achieving their aspirations and objectives, because these beliefs represent one of the most predictive factors of success [

1,

3]. A core characteristic of self-efficacy beliefs is that they are not a general construct, but they vary according to the domain of functioning involved, so there are a variety of self-efficacy beliefs for each context that people perceive as challenging [

48]. In this sense, the extent to which individuals feel adequately capable of effortfully regulating behaviors toward transgressive activities or feel adequately able to activate self-regulatory skills against peer pressure to behave transgressively is an example of self-regulatory efficacy [

1]. Several previous studies attested that self-regulatory self-efficacy beliefs can operate as a vehicle from individual to contextual influences on adaptive or maladaptive behavioral responses [

49].

In doing so, for youths’ adjustment, these capabilities can become fundamental skills to adequately organize their behaviors toward others, in offline and online contexts, such as in school settings or while youths navigate social networks [

2,

47,

50,

51,

52]. Previous studies evidenced the crucial importance of adequate levels of self-regulatory self-efficacy beliefs in protecting youths and adults from engaging in aggressive behaviors and antisocial conduct offline (see [

53] an extensive meta-analysis). Adolescents with higher self-regulatory self-efficacy beliefs engage in more prosocial behaviors, show higher psycho-social well-being, are more protected from internalizing and/or externalizing problems, perform better in school settings, and engage in less aggressive conduct [

47,

53,

54]. On the contrary, adolescents with low self-regulatory self-efficacy beliefs are more inclined to engage in risky activities, are more vulnerable to substance use and/or abuse, show academic problems, and tend to engage in more aggressive behaviors, offline and online, and more incline of being cyberbullies [

54,

55]. Thus, adequate levels of self-regulatory self-efficacy could represent a key protective factor, that may mitigate the effects of impulsivity on the expression of aggressive tendencies, in both online and offline relational contexts [

53,

55].

1.3. The Present Study

According to the above-mentioned theoretical premises [

2,

10,

53], research well attested the role of self-regulatory self-efficacy beliefs as a protective factor that can mitigate the negative effects of impulsive tendencies on the exercise of aggressive responses in relational contexts, but very limited studies investigated these effects in the online contexts [

10,

36]. Understanding these mechanisms in the online contexts represents a crucial and one of the most challenging aims nowadays, because of the huge spreading of online aggressive conduct, such as cyberbullying, hate speech, flaming, and so on [

10,

45,

46]. Youths are not only the most vulnerable target for engaging in aggressive conduct because of their higher sensitivity to negative emotions and lower self-regulative abilities [

56,

57,

58], but also because younger people use the most technological devices, so they show higher vulnerability to incur in online risks [

17,

59]. In analyzing these associations in online and offline contexts, it is important to take into account also the gender of the youths, as most research evidenced crucial differences in engaging in aggressive behaviors in this regard [

31,

56].

Therefore, the general aim of the present study is to fill the gap in the literature by investigating the role of self-regulatory self-efficacy beliefs in mediating the effects of impulsivity in aggressive responses, not only in traditional offline contexts [

8,

9] but also analyzing the specific associations between impulsivity and aggressions in the online contexts [

17]. To answer our general research question, we tested the potential mediating and protective role of self-regulatory self-efficacy, differently in the associations between impulsivity and offline aggression, and impulsivity and online aggression, and the kind of these associations in adolescent boys and girls, to analyze the moderating role of youths’ gender [

56]. Regarding offline aggressive behaviors, we hypothesized that high impulsivity would predict higher aggressive responses in both adolescent boys and girls, and, according to socio-cognitive theory, the protective role of self-regulatory self-efficacy beliefs would be stronger in boys who are the most vulnerable to these associations [

3,

53]. As regards online aggressive behaviors, considering the limited literature on this topic, our work had an exploratory aim, but we would hypothesize a similar effect of impulsivity on online aggressions, according to the limited previous research [

10,

39]. In particular, according to the online disinhibition theory and the computer-mediated-communication theory [

42,

43] that emphasized the specificity of the online context, which allows anonymity and wider space to externalize aggressive tendencies, we hypothesized a stronger effect of impulsivity on online aggressive behaviors, compared with the offline counterpart of these associations. We are not aware of previous studies that investigated the potential protective role of self-regulatory self-efficacy in the association between impulsivity and online aggression, but taking in mind that online aggression, compared with offline aggression, pertained to more girls, the protective role of self-efficacy beliefs could also emerge for adolescent girls, but this is an exploratory hypothesis.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants and Procedures

Participants were drawn for a wider longitudinal national project that was carried out in a junior high school located in Rome, that was a school-based intervention with the twofold aim of preventing online problematic behaviors while promoting positive behaviors in the online and offline social contexts [

5]. For the purposes of the present study, we considered youths who completed both pre- and post-intervention assessments (i.e., Wave 1 and Wave 2). A total sample of 318 adolescents was considered, from 14 to 18 years old (M

age=15.21;

SD=.51). Most of the youths involved in the present study enrolled in the second grade of junior high school (88% of the total sample), and they were mostly on time with their academic pathways (only 1% of students repeated one or more year of instruction). As regards their gender, youths were mostly distributed across the feminine (N = 156; 40% of the total sample) and the masculine (N = 225; 57% of the total sample) genders, and a small percentage of youths to the third gender (N = 11; 3% of the total sample). Youths mostly declared a heterosexual orientation (87% of the total sample), small percentages of other sexual orientations were registered (respectively, 1% homosexual, 4% bi-sexual, 3% queer, and 5% of other LGB+ sexual orientations), and they mostly declared of being single (70% of the total sample).

As regards youths’ socio-economic status, most of the youths involved in the study lived with spoused parents (79% of the sample), of which 88% of mothers and 97% of fathers had a full- or part-time occupation. Parents mostly declared an average-to-high educational level (36% of mothers and 37% of fathers had a high school diploma, and 44% of mothers and 39% of fathers had a bachelor’s or a master’s degree).

2.2. Measures

2.2.1. Background Characteristics

Descriptive information about the sample, such as youths’ age, gender, sexual orientation, years of formal instruction completed, and socio-economic status, was collected in the first Wave. Gender was coded as 0 for adolescent boys and 1 for adolescent girls, and sexual orientation was coded as 1 for heterosexual, 2 for homosexual, 3 for bisexual, and 4 for other LGB+ orientations. Years of formal instruction completed were directly asked to each student and recorded considering five years of primary school, three years of the first grade of secondary school, and each year of the second grade of secondary school completed (i.e., for those who enrolled in the second year of junior high school, were considered 5 + 3 + 2). The socioeconomic status of youths involved in the study was computed considering parents’ education and work occupation. Detailed information about the correlations among the study variables is reported in Table A1. Information about continuous variables is provided below.

2.2.2. Self-Regulatory Self-Efficacy

To assess adolescents’ perception of their own self-efficacy beliefs regarding their capabilities to self-regulate and orient behaviors we used six items derived from the Self-Regulatory Self-Efficacy Beliefs Scale [

60,

61], which assesses perceived abilities to resist peer pressure in engaging risky and transgressive behaviors, as well as to orient their behavior in a self-consciousness way to achieve planned goals [

49,

62]. Each item was rated on a 5-point Likert scale from 1, Not well at all, to 5, Very well (e.g., “How well can you resist peer pressure to do things that can get you in trouble?”, or “How well can you avoid behaving in a transgressive manner even when the risk for a punishment is very limited?”). A larger body of research firmly establishes the psychometric properties of this scale, both cross-culturally and longitudinally across different phases of adolescence [

61]. In our study, internal consistency was good (ω = .843, and α = .842; see Table A1).

2.2.3. Impulsivity

Youths’ self-evaluations of their impulsivity levels were assessed at Wave 1 adopting the Barratt Impulsiveness Scale – Brief [

18,

63] scale was developed and used to measure different aspects of Impulsivity, such as difficulties in self-regulatory processes, motor and attentive impulsivity, and lack of perseverance. Each item was rated on a 4-point Likert scale, from 1, Never, to 4, almost always/always (e.g., “I do things without thinking”, or “I don’t pay attention”). This scale is one of the most used worldwide to assess Impulsivity levels and a variety of previous research supported the validity of this instrument [

63,

64]. In our study, internal consistency was acceptable (ω = .710, and α = .772; see Table A1).

2.2.4. Online and Offline Aggressive Behaviors

Two different scales were considered to assess online and offline aggressive behaviors at Wave 2. To measure offline aggression we used five items derived from the Youth Self-Report (YSR; [

65]), which assesses the type of aggressive behaviors acted by the individual within the last six months, using a 3-point scale ranging from 0 “Not true”, to 2 “Very often true” (e.g., “I am cruelty, I bullied, or meanness to others”, “I physically attack people”). To measure online aggressive behaviors, we used the Online Aggression Scale [

66], a four-item instrument developed to assess a variety of online aggressive behaviors acted by the individual within the last 30 days, such as threatening others, insulting or stalking other people, each of them rated on a 4-point Likert scale ranging from 0 “Never”, to 3 “very often” (e.g., “Make rude or nasty comments about someone else online”, or “Use the Internet to threaten or embarrass someone”). The YSR measure was largely and widely adopted worldwide, and there is strong evidence of its cross-cultural and longitudinal validity [

67,

68]. In our study, internal consistency was good (ω = .916, and α = .911; see

Table 1). The Online Aggression Scale was a relatively new instrument and was adopted especially in Asian countries [

37,

69], so no Italian validation of the instrument is available to our knowledge. Despite these limitations, in our study, the internal consistency of this measure was good (ω = .814, and α = .804; see Table A1).

2.3. Statistical Approach

All analyses were run within Mplus 8.11, and to test our hypotheses, we adopted the following steps.

First, we examined the relations among the study variables in the general sample using a simple mediation model, considering impulsivity as the direct predictor of online and offline aggressive behaviors, and self-regulatory self-efficacy beliefs as the possible mediator of these associations [

70].

Then, we analyzed these relations in separate gender groups. Considering the smaller percentage of the third gender in our sample (3% of the total sample), we only considered the masculine and the feminine gender, so we tested our models separately in adolescent boys and girls, running a multiple-group mediation model, considering youths’ gender as a grouping variable, controlling for youths’ sexual orientation, age, socioeconomic status, and the years of formal instruction completed by students [

71].

We used Robust Maximum Likelihood Estimation (MLR) for continuous variables [

72] and considered the following criteria to evaluate the goodness of fit: χ2 Likelihood Ratio Statistic, the Comparative-Fit Index (CFI), and the Tucker-Lewis-Fit Index (TLI) greater than .95 [

73], the Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA) with associated confidence intervals lower than .05, and the Standardized Root Mean Square Residual (SRMR) lower than .06 [

74]. We first ran a model in which we fully constrained all the parameters to be equal across groups, and then a model in which we freely estimated all the parameters, comparing these two models using the Chi-square difference test [

74]. We released one constraint per comparison until the Chi-square difference test showed a non-significant increase in the chi-square, adopting a cutoff for the significance of p < .01 (given that obtaining a significant chi-square becomes increasingly likely with large sample sizes; [

74]).

3. Results

Preliminary descriptive and exploratory analyses were adopted on all the study variables to investigate means and standard deviations, skewness and kurtosis, internal consistency of the utilized constructs, and correlations among all the variables. Detailed information on these procedures is provided in Table A1 and in the Appendix.

3.1. Mediation-Moderation Model in the Full Sample

As the first step of our statistical approach, we ran the proposed mediation-moderation SEM model in the full sample, to analyze the hypothesized associations in the whole sample, controlling for youths’ age, sexual orientation, socioeconomic status, and the years of formal instruction completed by students [

70,

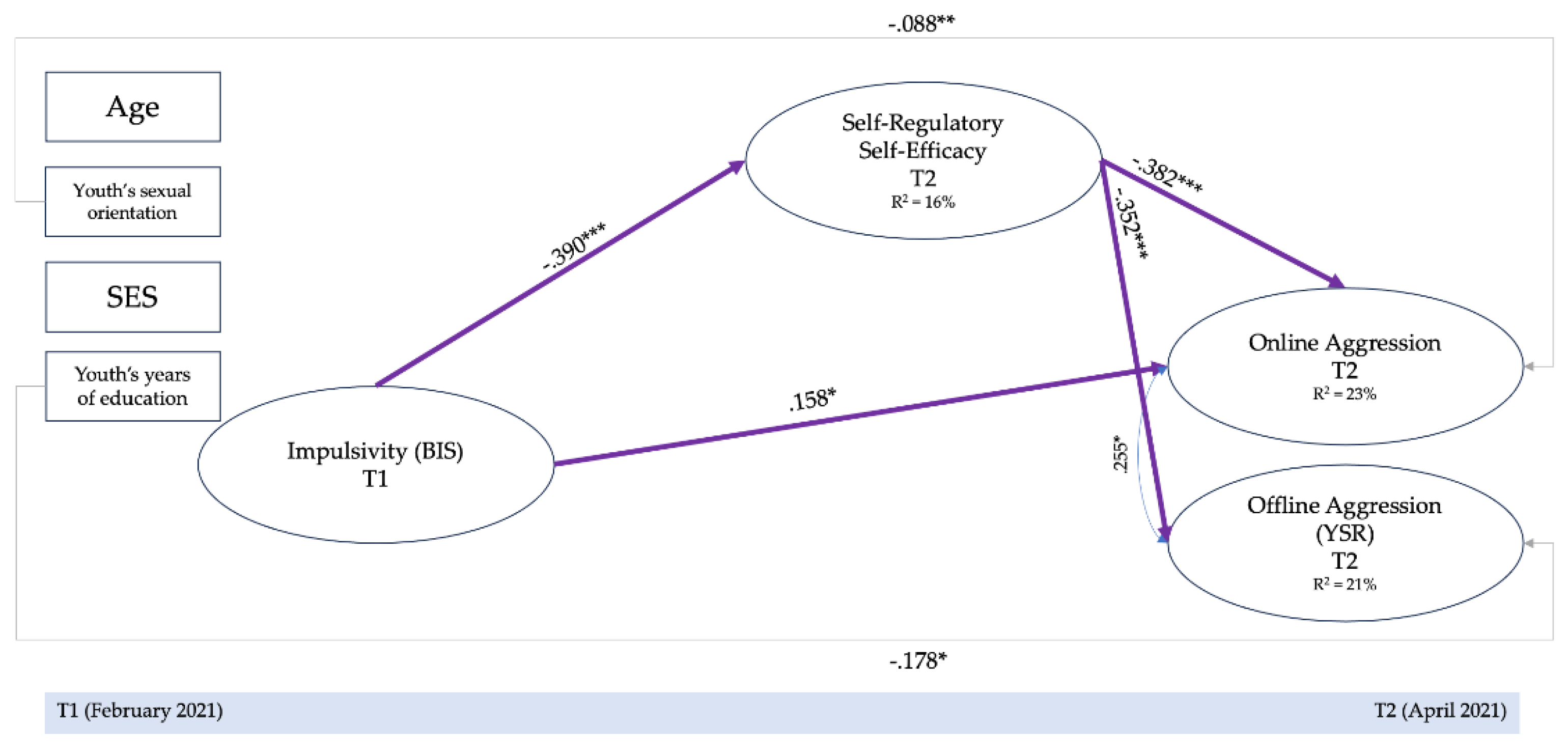

71]. The results of this model are shown in

Figure 1.

This model showed an adequate fit [χ

2 (Df = 295) = 358.209,

p <.005; RMSEA = .026 (C.I. = .014 - .035); CFI = .974, TLI = .969; SRMR = .050], as shown in

Table 1. For what concerns direct effects, higher impulsivity directly predicted higher aggression, only in the online context (

β = .16; p < .01), and self-regulatory self-efficacy beliefs predicted both lower online (

β = -.38; p < .001), and offline (

β = -.35; p < .001) aggression. As regards indirect effects, impulsivity indirectly predicted both online (

β = .15; p < .001) and offline aggression (

β = .14; p < .001), through the effects of self-regulatory self-efficacy.

3.2. Mediation-Moderation Models in Adolescent Boys and Girls

As the second step of our analyses, we estimated the same model examined in the previous paragraph, within a multiple-group framework, to analyze the emerged associations separately in the adolescent boys’ and adolescent girls’ samples, to test whether there were possible differences in direct and/or indirect effects emerged in the full sample model [

71].

The models estimated separately in the boys [χ

2 (Df = 295) = 400.366,

p <.001; RMSEA = .044 (C.I. = .033 - .055); CFI = .932, TLI = .920; SRMR = .065], and in the girls sample [χ

2 (Df = 295) = 347.693,

p = n.s.; RMSEA = .037 (C.I. = .016 - .052); CFI = .951, TLI = .943; SRMR = .080], showed an adequate fit, especially in the girls sample. Thus, we then estimated the multiple-group model in which we freely estimated all the parameters [χ

2 (Df = 628) = 872.141,

p < .001; RMSEA = .050 (C.I. = .042 - .058); CFI = .907, TLI = .898; SRMR = .080], to compare it with a nested model, in which we constrained all the parameters to be equal across the two groups [χ

2 (Df = 657) = 912.119,

p < .001; RMSEA = .049 (C.I. = .041 - .057); CFI = .906, TLI = .901; SRMR = .096]. The Chi-square difference test [

74] revealed that several parameters should be released across the two groups [χ

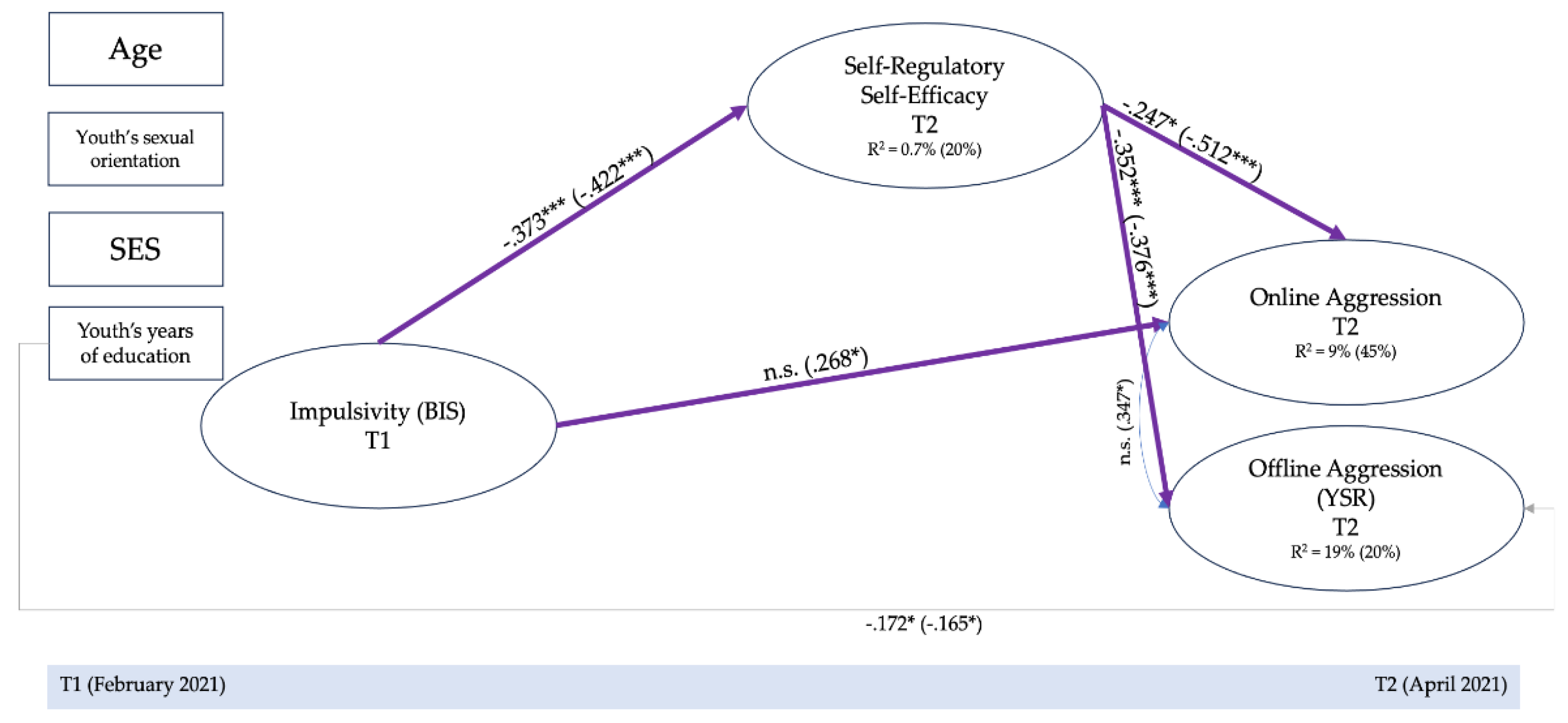

2 diff (25) = 39.247; p = .034], as reported in

Table 1. Therefore, considering the modification indices values, we released one parameter per time to compare the model with the previous one until this difference test became non-significant for p values higher than .05 [

74]. The final multi-group mediation-moderation model [χ

2 (Df = 654) = 902.634,

p < .001; RMSEA = .050 (C.I. = .041 - .057); CFI = .906, TLI = .901; SRMR = .096] reported an adequate fit. In particular, we freely estimated the indirect effect of impulsivity on online aggression, the indirect effect of impulsivity on offline aggression, and a correlation between the second and the fifth item of the self-regulatory self-efficacy scale. The results of this procedure are reported in

Table 1.

Notes:

χ2 = Chi-square Goodness of Fit;

Df = degrees of freedom; Scal. Corr. = Scaling Correction Factor; CFI=Comparative Fit Index; RMSEA = Root-Mean-Square Error of Approximation. All Δ _index comparisons were made comparing the model with the previous one.

Partial constraints a = indirect effects of impulsivity on offline aggression; indirect effects of impulsivity on online aggression; correlation among the second and the fifth item of self-regulatory self-efficacy beliefs (not depicted in

Figure 2). *

p < .050; **

p < .010; ***

p < .001.

As reported in

Figure 2, we did not find significant direct effects from impulsivity to offline aggression, confirming this result in the full sample model. Direct effects from impulsivity to online aggression were significant only for adolescent girls (

β = -.27; p < .05). Direct effects of self-regulatory self-efficacy to offline (

βboys = -.35; p < .001;

βgirls = -.38; p < .001) and online (

βboys = -.25; p < .001;

βgirls = -.51; p < .001) aggression were confirmed and were equal across the two groups.

As regards indirect effects, impulsivity indirectly predicted both online (β = .22; p < .001) and offline aggression (β = .16; p < .001), through the effects of self-regulatory self-efficacy only for adolescent girls, while the protective role of self-regulatory self-efficacy beliefs was significant in adolescent boys only in the offline context (β = .13; p < .01).

4. Discussion

The present study contributed to filling the existing gap in the literature that extensively focused on associations among individual characteristics (i.e., impulsivity and self-efficacy beliefs) in predicting transgressive and maladaptive behaviors in offline contexts [

9,

53,

54], and understudied these effects on online contexts [

17]. In particular, we examined whether the associations between impulsivity and aggressive behaviors would be mitigated by the effects of self-regulatory self-efficacy beliefs, similarly or differently in online and offline contexts, and if in these relations the gender of the youths involved may play a role [

8,

34]. Our preliminary evidence supported the differential role that self-efficacy has in reducing aggressive behaviors online and offline, and its mediating role in the relation between temperamental impulsivity and online aggressions in adolescent girls [

2,

10].

As regards offline aggressive behaviors, our results did not evidence any significant and direct association between impulsivity and aggressive conduct, analyze this association in the full sample nor consider the moderating role of gender. This result was contrary to our hypothesis and the large body of previous studies that underlined how higher impulsivity predicts higher aggressive behaviors in different offline contexts, such as in school settings or at-home relational exchanges [

41,

75]. Thus, we found a significant indirect effect of impulsivity on offline aggressive behaviors through the effect of self-regulatory self-efficacy beliefs, both in the full sample as well as when we considered the moderating role of gender, which was stronger in adolescent girls than boys. Thus, in our sample, both adolescent boys and girls who possessed higher impulsivity, especially regarding difficulties in emotion regulation and delay-discounting, did not directly show higher aggressive tendencies in offline contexts, such as in relation to others or in school settings [

30,

41]. However, when adolescents manifested high difficulties in regulating their emotions and behaviors and showed impairments in coping with potentially aroused and ambiguous stimuli, but at the same time felt sufficiently capable of effectively regulating their behaviors adaptively, they tended to act less aggressively, rather than when they felt them as not adequately capable of regulating their own behavior [

47,

54,

55]. Unexpectedly, this pattern is especially true in adolescent girls rather than boys. We reasoned that this result could be ascribable to the low mean levels of offline aggressive behaviors in our sample, which in turn could not represent a concrete risk in our sample, so there would be any reasons to activate individual beliefs of behavioral agency to contrast temperamental impairments regarding impulsive tendencies [

3,

49].

As regards online aggressive behaviors, overall, according to our hypothesis and to those theoretical approaches that investigated aggressive conduct online [

42,

43], we found stronger associations between impulsivity and these forms of aggression, and a more important mediating role of self-regulatory self-efficacy beliefs compared with associations found regarding offline aggression. In the full sample, we found a significant direct effect of impulsivity on online aggression, and, analyzing the moderating role of adolescents’ gender, that pattern was deeply identified as typical in adolescent girls, rather than in their male counterparts. This difference between the results in the full sample and the results of the multiple-group comparisons could be ascribable to the limited sample size, which could affect the strength of the association between impulsivity and online aggression [

76]. Thus, in our sample, impairments in impulsivity predispose, especially adolescent girls, to be more inclined to act aggressively while they are online, such as using social to threaten or embarrass someone or making rude/nasty comments about others on social media [

10,

46,

66]. Also, in this case, self-regulatory self-efficacy beliefs had a strong impact in directly reducing these online aggressive tendencies in both genders. In addition, adolescent girls who showed impulsive tendencies but who possess adequate self-regulatory self-efficacy beliefs were more protected from engaging in online aggressive conduct, as a proof of the crucial buffering role of individual self-efficacy beliefs in protecting people, especially the younger, from behavioral dysregulations [

1,

47,

52]. These results supported the protective role of individual agency, as a vehicle to support adaptive adolescents’ development, rather than considering only emotional and/or behavioral difficulties which may increase their risk of incurring maladaptive developmental patterns [

16,

22,

25].

4.1. Limitations

Our work represents an important step in understanding individual mechanisms that lead adolescents to behave aggressively, but we had to evidence several limitations of this study.

For one, we referred only to adolescents’ self-evaluation of their own impulsive tendencies, their self-efficacy beliefs, and their aggressive behaviors. No other sources of information, such as the perception of teachers or of their parents, were considered. Also, we could not include any genetic or neurophysiological indicators of impulsivity, despite mechanisms involved in dopaminergic circuitry that have been shown to undergo epigenetic modification in people who are exposed to social networks and the Internet and play an important role in impulsive responses [

18,

77,

78]. Several studies supported the view of aggressive behaviors as complex behavioral responses, of which younger people frequently did not have a clear and exhaustive view, as the sensitivity of those behaviors for social desirability, and the uniqueness of individual points of view [

32,

79,

80]. Therefore, future research should include other informants of youths’ behavioral responses, to have a more fine-grained picture of aggressive tendencies and behaviors, online as well as offline.

Another limitation of our work is the limited sample size, which could influence the strength, and the kind, of the emerged associations [

76]. Future research could benefit from larger sample sizes to test with more precision and accuracy our hypothesis. Lastly, despite we considered longitudinal predictions of impulsivity on offline and online aggressive behaviors, our time frame was short, as we considered only a 2-month interval to test our hypothesis. Therefore, our findings should be confirmed within a wider longitudinal framework, to deeply analyze long-term associations among behavioral impulsivity, self-regulatory self-efficacy, and aggressive conduct in adolescents. In addition, future research could consider also other cultures, testing the cross-cultural validity and replicability of these results [

81].

5. Conclusions

Despite several limitations of this study, our results took an important first step in that field of study that focuses on the examination of how temperamental vulnerabilities can predispose youths and adolescents to be more inclined to act in aggressive ways, offline and online [

8,

10,

38,

41].

This work extended previous studies that focused on the effects of self-regulatory self-efficacy beliefs in offline contexts as a vehicle for contrasting aggressive and transgressive tendencies (see [

53] for a review) and on the vulnerability of masculine populations to aggressive conduct [

8].

In particular, our findings evidenced that impulsivity directly predicts more online aggression, but adequate levels of self-regulatory self-efficacy beliefs can protect youths in online environments, by affecting this relation because it indirectly predicts lower online aggression over time. In addition, our findings evidenced the protective role of self-efficacy also in offline contexts, because adequate levels of self-regulatory self-efficacy beliefs can mitigate the indirect effects of impulsivity impairments.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at:

www.mdpi.com/xxx/s1, Table A1: Descriptive statistics and zero-order correlations of all the study variables.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.F., C.L., A.T.V., P.P., and T.Q.; methodology, A.F., C.L., and T.Q.; formal analysis, A.F., C.L., and A.T.V.; investigation, A.F., F.C.; writing—original draft preparation, A.F, A.T.V., L.C., P.P.; writing—review and editing, A.F., C.L., A.T.V., and L.C.; supervision, A.F., and P.P.; project administration, A.F., and F.C.; funding acquisition, A.F., and F.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was partly carried out thanks to a grant funded by the Department of Educational Policies, Roma Capitale, Grant Number: QM20210010648.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Institutional Review Board of Academic Foundation Policlinic Agostino Gemelli IRCCS (09/21/2021).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

We thank the junior high school for its willingness to participate in the intervention, and all families, students, teachers, and the school staff who helped us to carry out the project.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Bandura, A., Caprara, G. V., Barbaranelli, C., Gerbino, M., & Pastorelli, C. (2003). Role of affective self-regulatory efficacy in diverse spheres of psychosocial functioning. Child Development, 74(3), 769–782. [CrossRef]

- LaRose, R., Kim, J., & Peng, W. (2010). Social networking: Addictive, compulsive, problematic, or just another media habit? In Z. Papacharissi (Ed.), A networked self (pp. 67–89). Routledge.

- Bandura, A., Caprara, G. V., Barbaranelli, C., Pastorelli, C., & Regalia, C. (2001). Socio-cognitive self-regulatory mechanisms governing transgressive behavior. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 80(1), 125–135. [CrossRef]

- Muris, P. (2006). Freud was right about the origins of abnormal behavior. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 15(1), 1–12. [CrossRef]

- Favini, A., Culcasi, F., Cirimele, F., Remondi, C., Plata, M. G., Caldaroni, S., Virzì, A. T., & Luengo Kanacri, B. P. (2023). Smartphone and social network addiction in early adolescents: The role of self-regulatory self-efficacy in a pilot school-based intervention. Journal of Adolescence, 1–15. [CrossRef]

- Bronfenbrenner, U., & Morris, P. A. (2006). The Bioecological Model of Human Development. In Lerner, R. M. (Ed.) Handbook of Child Psychology. Volume 1: Theoretical Models of Human Development. John Wiley & Sons.

- Steinberg, L. (2007). Risk Taking in Adolescence: New Perspective From Brain and Behavioral Science. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 16(2), 55-59. [CrossRef]

- Bettencourt, B., Talley, A., Benjamin, A. J., & Valentine, J. (2006). Personality and aggressive behavior under provoking and neutral conditions: a meta-analytic review. Psychological bulletin, 132(5), 751-777. [CrossRef]

- Piko, B. F., & Pinczés, T. (2014). Impulsivity, depression and aggression among adolescents. Personality and individual differences, 69, 33-37. [CrossRef]

- Zych, I., Kaakinen, M., Savolainen, I., Sirola, A., Paek, H.J., Oksanen, A. (2023). The role of impulsivity, social relations online and offline, and compulsive Internet use in cyberaggression: A four-country study. New Media & Society, 25(1), 181-198. [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y., Rogers, R., (2020). Development and validation of the Online Learning Self-Efficacy Scale (OLSS): A structural equation modeling approach. American Journal of Distance Education, 35(1), 184-199. [CrossRef]

- Page Hocevar, C., Flanagin, A. J., Metzger, M. J. (2014). Social media self-efficacy and information evaluation online. Computers in Human Behavior, 39, 254-262. [CrossRef]

- Jokisch, M. R., Schmidt, L. I., Doh, M., Marquard, M., & Wahl, H. W. (2020). The role of internet self-efficacy, innovativeness and technology avoidance in breadth of internet use: Comparing older technology experts and non-experts. Computers in Human Behavior, 111, 106408. [CrossRef]

- Cannito, L.; Annunzi, E.; Viganò, C.; Dell’Osso, B.; Vismara, M.; Sacco, P.L.; Palumbo, R.; D’Addario, C. The Role of Stress and Cognitive Absorption in Predicting Social Network Addiction. Brain Sci. 2022, 12, 643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alqurashi, E. (2016). Self-Efficacy in Online Learning Environments: A Literature Review. Contemporary Issues in Education Research, 9(1), 45-52. [CrossRef]

- Velotti, P., Garofalo, C., Petrocchi, C., Cavallo, F., Popolo, R., & Dimaggio, G. (2016). Alexithymia, emotion dysregulation, impulsivity and aggression: A multiple mediation model. Psychiatry research, 237, 296-303. [CrossRef]

- Kaakinen, M., Sirola, A., Savolainen, I., Oksanen, A. (2020). Impulsivity, internalizing symptoms, and online group behavior as determinants of online hate. PLoS ONE 15(4):e0231052. [CrossRef]

- Steinberg, L., Sharp, C., Stanford, M. S., & Tharp A. T. (2013). New Tricks for an Old Measure: The Development of the Barratt Impulsiveness Scale-Brief (BIS-Brief). Psychological Assessment, 25(1), 216-226. [CrossRef]

- Cassey, B. J., Jones, R. M., & Hare, T. A. (2008). The adolescent brain. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 1124, 111–126. [CrossRef]

- Compas, B. E., & Reeslund, K. L. (2009) Processes of Risk and Resilience During Adolescence. In Lerner, R. M. & Steinberg, L. (Eds.) Handbook of Adolescent Psychology. John Wiley & Sons. [CrossRef]

- Cannito L, Ceccato I, Annunzi E, Bortolotti A, D’Intino E, Palumbo R, D’Addario C, Di Domenico A and Palumbo R (2023) Bored with boredom? Trait boredom predicts internet addiction through the mediating role of attentional bias toward social networks. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 17:1179142. [CrossRef]

- Hyatt, C. S., Zeichner, A., & Miller, J. D. (2019). Laboratory aggression and personality traits: A meta-analytic review. Psychology of Violence, 9(6), 675–689. [CrossRef]

- Bresin, K. (2019). Impulsivity and aggression: A meta-analysis using the UPPS model of Impulsivity. Aggression and Violent Behavior, 48, 124-140. [CrossRef]

- Dvorak, R. D., Lamis, D. A., & Malone, P. S. (2013). Alcohol use, depressive symptoms, and impulsivity as risk factors for suicide proneness among college students. Journal of Affective Disorders, 149, 326–334. [CrossRef]

- Crick, N. R.,&Dodge, K. A. (1994). A review and reformulation of social information-processing mechanisms in children’s social adjustment. Psychological Bulletin, 115(1), 74-101. [CrossRef]

- Serin, R. C., & Kuriychuk, M. (1994). Social and cognitive processing deficits in violent offenders: Implications for treatment. International Journal of Law and Psychiatry, 17(4), 431-441. [CrossRef]

- Farrington, D. P. (2009). Conduct Disorder, Aggression, and Delinquency. In Lerner, R. M. & Steinberg, L. (Eds.) Handbook of Adolescent Psychology. John Wiley & Sons. [CrossRef]

- Seager, J. A. (2005) Violent Men: The Importance of Impulsivity and Cognitive Schema. Criminal Justice and Behavior, 32(1), 26-49. [CrossRef]

- Smith, P., & Waterman, M. (2006). Self-reported aggression and impulsivity in forensic and non-forensic populations: The role of gender and experience. Journal of Family Violence, 21, 425-437. [CrossRef]

- Farrington, D. P., Ttofi, M. M., Crago, R. V., Coid, J. W. (2015). Intergenerational similarities in risk factors for offending. Journal of Developmental and Life-course Criminology, 1, 48–62. [CrossRef]

- Cross, C. P., Copping, L. T., Campbell, A. (2011). Sex differences in impulsivity: A meta-analysis. Psychological Bulletin, 137(1), 97-130. [CrossRef]

- d'Acremont, M., Van der Linden, M. (2005). Adolescent Impulsivity: Findings From a Community Sample. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 34, 427–435. [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, M. R., & Potenza, M. N. (2015). Importance of sex differences in impulse control and addictions. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 6, 24. [CrossRef]

- Breuer, J., & Elson, M. (2017). Frustration-aggression theory. The Wiley Handbook of Violence and Aggression (pp. 1-12). Chichester: Wiley Blackwell. [CrossRef]

- Kim, E. J., Namkoong, K., Ku, T., Kim, S. J. (2008) The relationship between online game addiction and aggression, self-control and narcissistic personality traits. European Psychiatry, 23, 212-218.

- Nocentini, A., Zambuto, V., Menesini E. (2015). Anti-bullying programs and Information and Communication Technologies (ICTs): A systematic review. Aggression and Violent Behavior, 23, 52-60. [CrossRef]

- Udris, R. (2016). Psychological and Social Factors as Predictors of Online and Offline Deviant Behavior among Japanese Adolescents. Deviant Behavior, 38(7), 792–809. [CrossRef]

- Berkowitz, L. (1993). Aggression: Its causes, consequences, and control. Mcgraw-Hill Book Company.

- Graf, D., Yanagida, T., Runions, K., Spiel, C. (2022). Why did you do that? Differential types of aggression in offline and in cyberbullying. Computers in Human Behavior, 128, 107107. [CrossRef]

- Howard, R. C. (2011). The quest for excitement: A missing link between personality disorder and violence? Journal of Forensic Psychiatry and Psychology, 22(5), 692–705. [CrossRef]

- Franco, C., Amutio, A., López-González, L., Oriol, X., & Martínez-Taboada, C. (2016). Effect of a mindfulness training program on the impulsivity and aggression levels of adolescents with behavioral problems in the classroom. Frontiers in Psychology, 7, 1385. [CrossRef]

- Runions, K. C. (2013). Toward a conceptual model of motive and self-control in cyberaggression: Rage, revenge, reward, and recreation. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 42(5), 751–771. [CrossRef]

- Suler, J. (2004). The online disinhibition effect. CyberPsychology and Behavior, 7(3), 321–326. [CrossRef]

- Guo S (2016) A meta-analysis of the predictors of cyberbullying perpetration and victimization. Psychology in the Schools, 53, 432–453. [CrossRef]

- Rost, K., Stahel, L., Frey, B. S. (2016). Digital Social Norm Enforcement: Online Firestorms in Social Media. PLoS ONE 11(6): e0155923. [CrossRef]

- Turel, O., & Qahri-Saremi, H. (2018). Explaining unplanned online media behaviors: Dual system theory models of impulsive use and swearing on social networking sites. New Media & Society, 20(8), 3050-3067. [CrossRef]

- Caprara, G. V., Di Giunta, L., Eisenberg, N., Gerbino, M., Pastorelli, C., & Tramontano, C. (2008). Assessing regulatory emotional self-efficacy in three countries. Psychological assessment, 20(3), 227.

- Caprara, G. V. (2001). La valutazione dell'autoefficacia. Costrutti e strumenti. Edizioni Erickson.

- Caprara, G. V., Regalia, C., & Bandura, A. (2002). Longitudinal Impact of Perceived Self-Regulatory Efficacy on Violent Conduct. European Psychologist, 7(1), 63-69. [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y., Gao, Q. (2023). Effects of Social Media Self-Efficacy on Informational Use, Loneliness, and Self-Esteem of Older Adults. International Journal of Human–Computer Interaction, 39(5), 1121-1133. [CrossRef]

- Eastin, M. S., & LaRose, R. (2000). Internet self-efficacy and the psychology of the digital divide. Journal of computer-mediated communication, 6(1), JCMC611. [CrossRef]

- Hocevar, K. P., Flanagin, A. J., & Metzger, M. J. (2014). Social media self-efficacy and information evaluation online. Computers in Human Behavior, 39, 254–262. [CrossRef]

- Alessandri, G., Tavolucci, S., Perinelli, E., Eisenberg, N., Golfieri, F., Caprara, G: V., Crocetti, E. (2023). Regulatory emotional self-efficacy beliefs matter for (mal)adjustment: A meta-analysis. Current Psychology, 42, 31004-31023. [CrossRef]

- Gomez-Plata, M., Laghi, F., Cirimele, F., Thartori, E., Paba Barbosa, C., Ruiz-Garcia, M., Uribe Tirado, L. M., Pastorelli, C. (2020). The protective role of regulatory and parental self-efficacy in substance use in Colombian adolescents. In 26th Biennal Meeting of the International Society for the Study of Behavioural Development (ISSBD).

- Paciello, M., Corbelli, G., Di Pomponio, I., Cerniglia, L. (2023). Protective Role of Self-Regulatory Efficacy: A Moderated Mediation Model on the Influence of Impulsivity on Cyberbullying through Moral Disengagement. Children, 10(2), 219. [CrossRef]

- Henriksen, M., Skrove, M., Hoftun, G. B., Lydersen, S., Stover, C., Kalvin, C. B., & Sukhodolsky, D. G. (2023). Sex Differences and Similarities in Risk Factors of Physical Aggression in Adolescence. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 32(4), 1177-1191. [CrossRef]

- Hyatt, C. S., Zeichner, A., & Miller, J. D. (2019). Laboratory aggression and personality traits: A meta-analytic review. Psychology of Violence, 9(6), 675–689. [CrossRef]

- Sadeghi-Bahmani, D., Brand, S. (2022). Sleep Medicine Reviews “Stay hungry, stay foolish, stay tough and sleep well!”; why resilience and mental toughness and restoring sleep are associated. Sleep Medicine Reviews, 62, 101618. [CrossRef]

- Cheng, C., Lau, Y., Chan, L., & Luk, J. W. (2021). Prevalence of social media addiction across 32 nations: Meta-analysis with subgroup analysis of classification schemes and cultural values. Addictive Behaviors, 117, 106845. [CrossRef]

- Bandura, A., Barbaranelli, C., Caprara, G. V., & Pastorelli, C. (1996). Multifaced impact of self-efficacy beliefs on academic functioning. Child Development, 67, 1206-1222. [CrossRef]

- Pastorelli, C., Caprara, G. V., Barbaranelli, C., Rola, J., Rozsa, S., & Bandura, A. (2001). The structure of children's perceived self-efficacy: A cross-national study. European Journal of Psychological Assessment, 17(2), 87–97. [CrossRef]

- Vecchio, G. M., Gerbino, M., Pastorelli, C., Del Bove, G., & Caprara, G. V. (2007) Multi-faceted self-efficacy beliefs as predictors of life satisfaction in late adolescence. Personality and Individual Differences, 43, 1807-1818. [CrossRef]

- Fossati, A., Di Ceglie, A., Acquarini, E., & Barratt, E. S. (2001). Psychometric properties of an Italian version of the Barratt Impulsiveness Scale-11 (BIS-11) in nonclinical subjects. Journal of clinical psychology, 57(6), 815-828. [CrossRef]

- Fossati, A., Barratt, E. S., Acquarini, E., & Ceglie, A. D. (2002). Psychometric properties of an adolescent version of the Barratt Impulsiveness Scale-11 for a sample of Italian high school students. Perceptual and Motor Skills, 95, 621–635. [CrossRef]

- Achenbach, T. M. (1991). Integrative guide for the 1991 CBCL/4-18, YSR and TRF profiles. Burlington, VT: Department of Psychiatry, University of Vermont.

- Werner, N. E., Bumpus, M. F., & Rock, D. (2010). Involvement in Internet Aggression During Early Adolescence. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 39, 607-619. [CrossRef]

- Achenbach, T. M., Becker, A., Döpfner, M., Heiervang, E., Roessner, V., Steinhausen, H. C., & Rothenberger, A. (2008). Multicultural assessment of child and adolescent psychopathology with ASEBA and SDQ instruments: research findings, applications, and future directions. Journal of child psychology and psychiatry, 49(3), 251-275. [CrossRef]

- Frigerio, A., Cattaneo, C., Cataldo, M. G., Schiatti, A., Molteni, M., & Battaglia, M. (2004). Behavioral and emotional problems among Italian children and adolescents ages 4 to 18 years as reported by parents and teachers. European Journal of Psychological Assessment, 20, 124–133. [CrossRef]

- Xu, B., Xu, Z., & Li, D. (2016). Internet aggression in online communities: a contemporary deterrence perspective. Information Systems Journal, 26(6), 641-667. [CrossRef]

- Hayes, A. F., & Preacher, K. J. (2014). Statistical mediation analysis with a multicategorical independent variable. British journal of mathematical and statistical psychology, 67(3), 451-470. [CrossRef]

- Deng, L., & Yuan, K. H. (2015). Multiple-group analysis for structural equation modeling with dependent samples. Structural equation modeling: a multidisciplinary journal, 22(4), 552-567. [CrossRef]

- Maydeu-Olivares, A. (2017). Maximum likelihood estimation of structural equation models for continuous data: Standard errors and goodness of fit. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal, 24(3), 383-394. [CrossRef]

- Hu, L. T., & Bentler, P. M. (1999). Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural equation modeling: a multidisciplinary journal, 6(1), 1-55. [CrossRef]

- Kline, R. B. (2023). Principles and practice of structural equation modeling (5th ed.). New York: Guilford Press. https://www.guilford.com/books/Principles-and-Practice-of-Structural-Equation-Modeling/Rex-Kline/9781462551910.

- Dubas, J. S., Baams, L., Doornwaard, S. M., & van Aken, M. A. (2017). Dark personality traits and impulsivity among adolescents: Differential links to problem behaviors and family relations. Journal of abnormal psychology, 126(7), 877- 889. [CrossRef]

- Wolf, E. J., Harrington, K. M., Clark, S. L., & Miller, M. W. (2013). Sample size requirements for structural equation models: An evaluation of power, bias, and solution propriety. Educational and psychological measurement, 73(6), 913-934. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S., Hu, S., Hu, J., Wu, P. L., Chao, H. H., & Li, C. S. R. (2015). Barratt impulsivity and neural regulation of physiological arousal. PLoS One, 10(6), e0129139. [CrossRef]

- Annunzi, E., Cannito, L., Bellia, F. et al. Mild internet use is associated with epigenetic alterations of key neurotransmission genes in salivary DNA of young university students. Sci Rep 13, 22192 (2023). [CrossRef]

- De Los Reyes, A. (2011). Introduction to the special section: More than measurement error: Discovering meaning behind informant discrepancies in clinical assessments of children and adolescents. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology, 40(1), 1–9. [CrossRef]

- Poltavski, D., Van Eck, R., Winger, A. T., & Honts, C. (2018). Using a polygraph system for evaluation of the social desirability response bias in self-report measures of aggression. Applied psychophysiology and biofeedback, 43, 309-318. [CrossRef]

- Hoefer, C., Eisenberg, N. (2008). Emotion-Related Regulation: Biological and Cultural Bases. In M., Vandekerckhove, C., von Scheve, S., Ismer, S., Jung and S., Kronast (Eds.), Regulating Emotions: Culture, Social Necessity, and Biological Inheritance, pp. 61-82. Blackwell Publishing Ltd.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).