Submitted:

30 July 2024

Posted:

02 August 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

1.1. Adversity, Stress, and Development in Youth

1.2. Need for Strengths-Based Approaches

1.2.1. Self-Determination Theory and Basic Psychological Needs

1.2.2. Solution Focused Brief Therapy

1.2.3. Positive Youth Development

1.3. Summary

2. Mental Skills Training (MST)

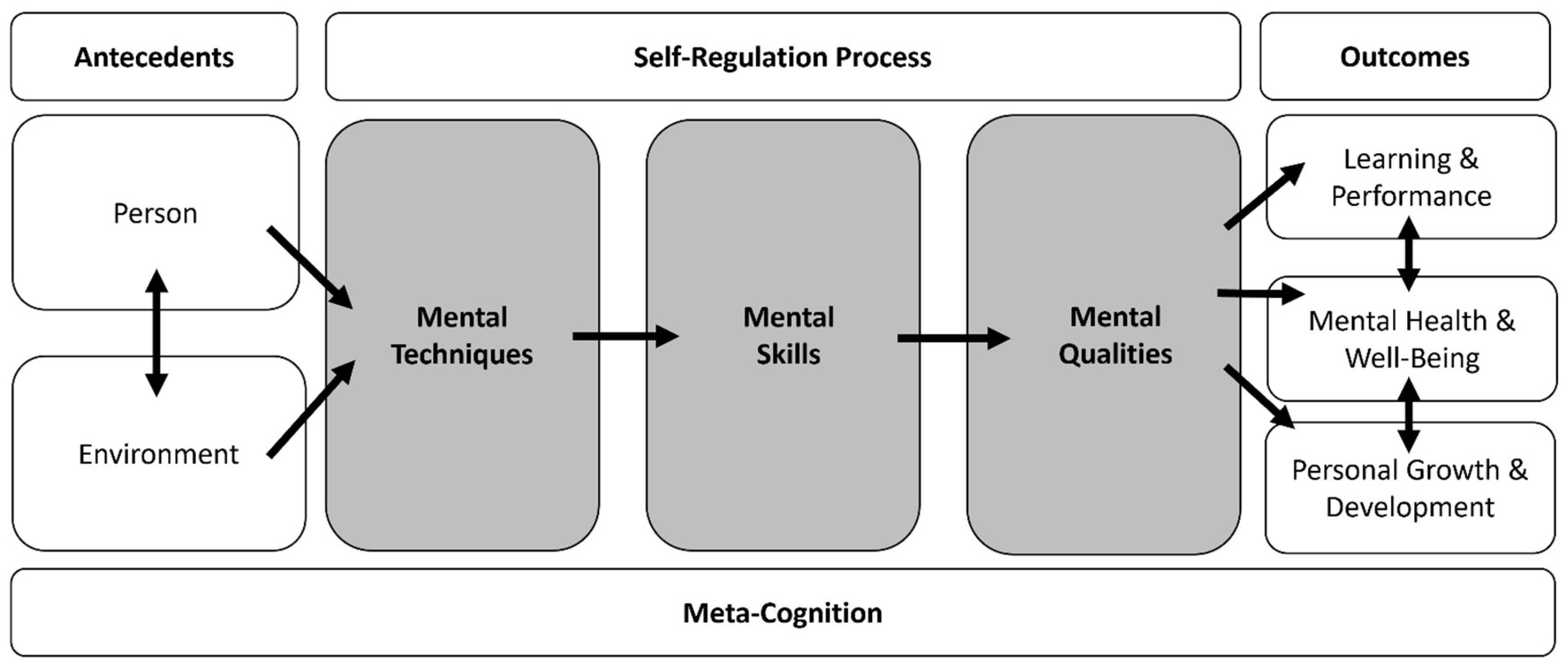

| Term | Definition | Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Mental techniques | Cognitive or behavioural techniques used to build mental skills and qualities [63]. | Action planning Goal-setting Positive self-talk Support seeking |

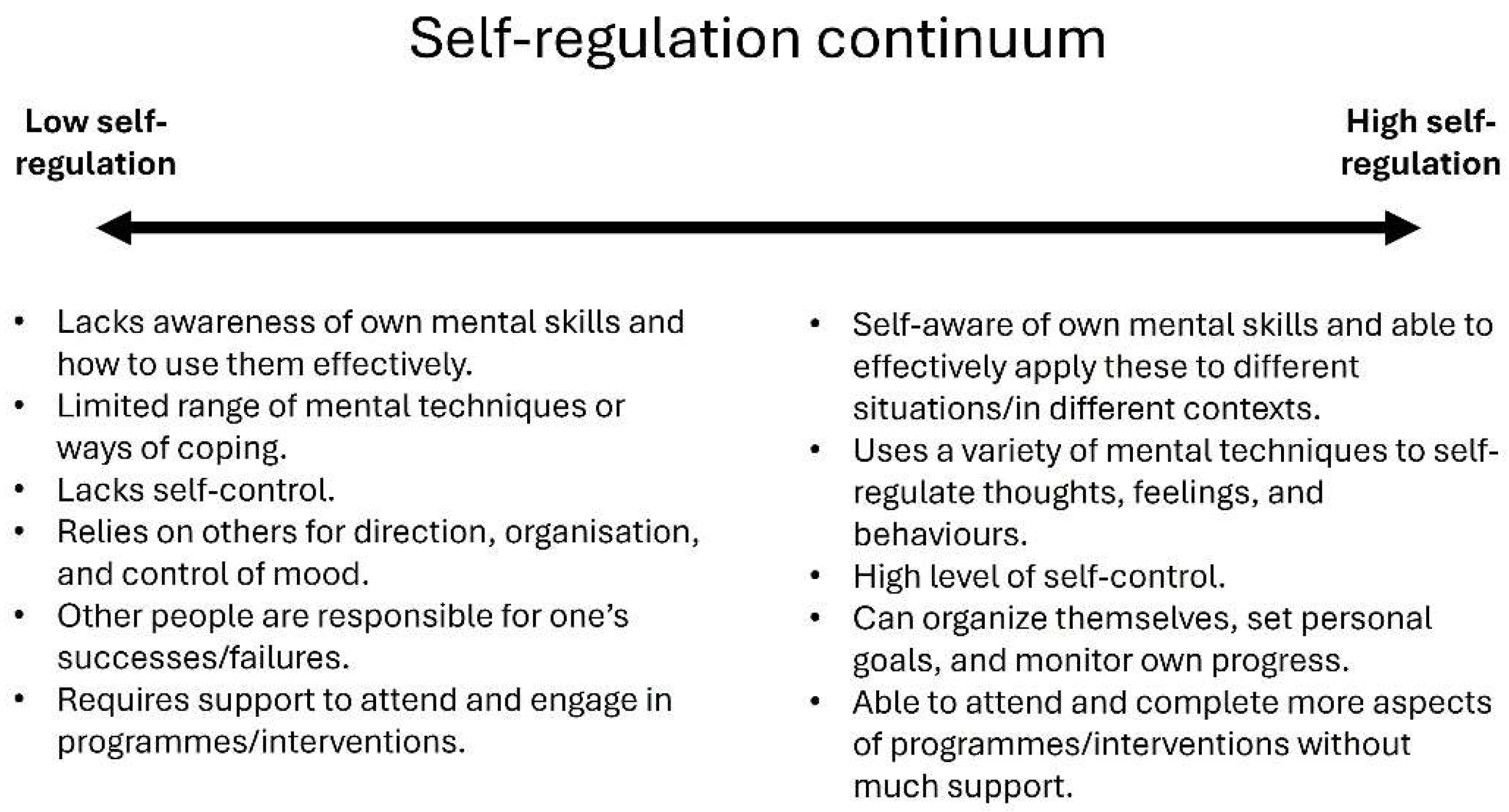

| Mental skills | The capacity to intentionally self-regulate thoughts, emotions, and behaviours [63]. | Focusing attention Handling pressure Self-awareness Self-control |

| Mental qualities | Positive intrapersonal and/or interpersonal characteristics displayed by or within an individual [63]. | Intrinsic motivation Resilience Self-confidence Self-worth |

| Mental skills transfer | The application of mental skills developed in one context and then applied to a new one. | Learning positive self-talk from support worker and then using positive self-talk before a job interview. |

| Mental skills training | The systematic development, application, and implementation of mental techniques for developing mental skills to promote the mental qualities needed for well-being and optimal development [55,63]. |

LifeMatters [64] MST4Life™ [55] |

2.1. How MST Works

2.2. LifeMatters

2.3. My Strengths Training for Life™ (MST4Life™)

| Characteristics | LifeMatters | MST4Life™ |

|---|---|---|

|

Yes [74,75,77] | Yes [55,62] |

|

Unclear | Yes [55,62,68] |

|

Unclear | Yes [87] |

|

Yes [74] | Yes [55,94] |

|

Yes [77] | Yes [55,86,90] |

|

Unclear1 | Yes [55,90] |

3. Discussion

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Moreton, R.; Welford, J.; Collinson, B.; Greason, L.; Milner, C. Improving access to mental health services for those experiencing multiple disadvantage. Housing, Care and Support 2022. [CrossRef]

- Sandu, R.D. Defining severe and multiple disadvantage from the inside: Perspectives of young people and of their support workers. Journal of Community Psychology 2021, 49, 1470–1486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rankin, J.; Regan, S. Meeting complex needs: The future of social care; London, UK, 2004.

- Bramley, G.; Fitzpatrick, S. Hard Edges: Mapping severe and multiple disadvantage; London, UK, 2015.

- Moreton, R.; Welford, J.; Howe, P. Evaluation of Fulfilling Lives: Why we need to invest in multiple disadvantage; 2021.

- Prince, D.M.; Rocha, A.; Nurius, P.S. Multiple disadvantage and discrimination: Implications for adolescent health and education. Social Work Research 2018, 42, 169–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Centrepoint. Summary report: The youth homeless databank 2022-2023; London, UK, 2023.

- Homeless Link. We have a voice, follow our lead: Young and homeless 2020; Homeless Link: London, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Homeless Link. Young & Homeless 2018; Homeless Link: London, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Bevington, D.; Fuggle, P.; Fonagy, P. Applying attachment theory to effective practice with hard-to-reach youth: the AMBIT approach. Attachment & Human Development 2015, 17, 157–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cameron, L.D.; Carroll, P.; Hamilton, W.K. Evaluation of an intervention promoting emotion regulation skills for adults with persisting distress due to adverse childhood experiences. Child Abuse & Neglect 2018, 79, 423–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dowding, K.; Murphy, D.; Everitt, G.; Tickle, A. Use of one-to-one psychotherapeutic interventions for people experiencing severe and multiple disadvantages: An evaluation of two regional pilot projects. Counselling and Psychotherapy Research 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hauser, M.D. How early life adversity transforms the learning brain. Mind, Brain, and Education 2021, 15, 35–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blakemore, S.-J.; Robbins, T.W. Decision-making in the adolescent brain. Nature Neuroscience 2012, 15, 1184–1191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blakemore, S.J.; Choudhury, S. Development of the adolescent brain: implications for executive function and social cognition. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry 2006, 47, 296–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brindle, R.C.; Pearson, A.; Ginty, A.T. Adverse childhood experiences (ACEs) relate to blunted cardiovascular and cortisol reactivity to acute laboratory stress: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews 2022, 134. [Google Scholar]

- Shonkoff, J.P.; Garner, A.S.; Child, C.o.P.A.o.; Family Health, C.o.E.C. , Adoption,; Dependent Care; Developmental, S.o.; Pediatrics, B.; Siegel, B.S.; Dobbins, M.I.; Earls, M.F.; et al. The lifelong effects of early childhood adversity and toxic stress. Pediatrics 2012, 129, e232–e246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Felitti, V.J. Adverse childhood experiences and adult health. Academic pediatrics 2009, 9, 131–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hackman, D.A.; Farah, M.J.; Meaney, M.J. Socioeconomic status and the brain: mechanistic insights from human and animal research. Nature reviews. Neuroscience 2010, 11, 651–659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murray, D.W.; Rosanbalm, K.; Christopoulos, C.; Hamoudi, A. Self-regulation and toxic stress: Foundations for understanding self-regulation from an applied developmental perspective; Office of Planning, Research and Evaluation, Administration for Children and Families, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services: Washington, DC, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- McEwen, B.S.; Gianaros, P.J. Central role of the brain in stress and adaptation: Links to socioeconomic status, health, and disease: Central links between stress and SES. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences 2010, 1186, 190–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Willingham, D.T. Ask the cognitive scientist: Why does family wealth affect learning? American Educator 2012, 36, 33–39. [Google Scholar]

- Eldesouky, L.; Gross, J.J. Emotion regulation goals: An individual difference perspective. Social and Personality Psychology Compass 2019, 13, e12493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gestsdottir, S.; Lerner, R.M. Positive development in adolescence: The development and role of intentional self-regulation. Human Development 2008, 51, 202–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rapp-Paglicci, L.; Stewart, C.; Rowe, W. Can a self-regulation skills and cultural arts program promote positive outcomes in mental health symptoms and academic achievement for at-risk youth? Journal of Social Service Research 2011, 37, 309–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahranavard, S.; Miri, M.R.; Salehiniya, H. The relationship between self-regulation and educational performance in students. J Educ Health Promot 2018, 7, 154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Palmer, L.; Richardson, E.W.; Goetz, J.; Futris, T.G.; Gale, J.; DeMeester, K. Financial self-efficacy: mediating the association between self-regulation and financial management behaviors. Journal of Financial Counseling and Planning 2021, 32, 535–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moffitt, T.E.; Arseneault, L.; Belsky, D.; Dickson, N.; Hancox, R.J.; Harrington, H.; Houts, R.; Poulton, R.; Roberts, B.W.; Ross, S. A gradient of childhood self-control predicts health, wealth, and public safety. Proceedings of the national Academy of Sciences 2011, 108, 2693–2698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Compas, B.E.; Connor-Smith, J.K.; Saltzman, H.; Thomsen, A.H.; Wadsworth, M.E. Coping with stress during childhood and adolescence: problems, progress, and potential in theory and research. Psychological bulletin 2001, 127, 87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wadsworth, M.E. Development of maladaptive coping: A functional adaptation to chronic, uncontrollable stress. Child Development Perspectives 2015, 9, 96–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Evans, G.W.; Kim, P. Childhood poverty and young adults’ allostatic load: The mediating role of childhood cumulative risk exposure. Psychological science 2012, 23, 979–983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thompson, J.R.; Shogren, K.A.; Wehmeyer, M.L. Supports and support needs in strengths-based models of intellectual disability. In Handbook of Research-Based Practices for Educating Students with Intellectual Disability, 1st ed.; Shogren, K.A., Ed.; Routledge: New York, NY, 2016; pp. 39–57. [Google Scholar]

- Sweeney, A.; Filson, B.; Kennedy, A.; Collinson, L.; Gillard, S. A paradigm shift: relationships in trauma-informed mental health services. BJPsych advances 2018, 24, 319–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Magwood, O.; Leki, V.Y.; Kpade, V.; Saad, A.; Alkhateeb, Q.; Gebremeskel, A.; Rehman, A.; Hannigan, T.; Pinto, N.; Sun, A.H. Common trust and personal safety issues: a systematic review on the acceptability of health and social interventions for persons with lived experience of homelessness. PloS one 2019, 14, e0226306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Caiels, J.; Milne, A.; Beadle-Brown, J. Strengths-based approaches in social work and social care: Reviewing the evidence. Journal of Long Term Care 2021, 401–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rapp, C.A.; Saleebey, D.; Sullivan, W.P. The future of strengths-based social work. Advances in Social Work 2006, 6, 79–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgan, A.; Ziglio, E. Revitalising the evidence base for public health: An assets model. Promotion & Education 2007, 14, 17–22. [Google Scholar]

- Lerner, R.M. The positive youth development perspective: Theoretical and empirical bases of strengths-based approach to adolescent development. In Oxford Handbook of Positive Psychology, 2nd ed.; Lopez, S.J., Snyder, C.R., Eds.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, 2009; pp. 149–163. [Google Scholar]

- Grant, J.G.; Cadell, S. Power, pathological worldviews, and the strengths perspective in social work. Families in Society 2009, 90, 425–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scerra, N. Scerra, N. Strengths-based practices: An overview of the evidence. Developing Practice: The Child, Youth and Family Work Journal 2012, 43-52.

- Simmons, C.A.; Shapiro, V.B.; Accomazzo, S.; Manthey, T.J. Strengths-based social work: A meta-theory to guide social work research and practice. In Theoretical Perspectives for Direct Social Work Practice, 3rd ed.; Coady, N., Lehmann, P., Eds.; Springer: New York, NY, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Bartholomew, K.J.; Ntoumanis, N.; Ryan, R.M.; Bosch, J.A.; Thøgersen-Ntoumani, C. Self-determination theory and diminished functioning: The role of interpersonal control and psychological need thwarting. Personality and social psychology bulletin 2011, 37, 1459–1473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deci, E.L.; Ryan, R.M. Self-determination research: Reflections and future directions. In Handbook of Self-Determination Research, Deci, E.L., Ryan, R.M., Eds.; University of Rochester Press: 2002; pp. 431–441.

- Ryan, R.M.; Deci, E.L. The darker and brighter sides of human existence: Basic psychological needs as a unifying concept. Psychological inquiry 2000, 11, 319–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vansteenkiste, M.; Ryan, R.M.; Soenens, B. Basic psychological need theory: Advancements, critical themes, and future directions. Motivation and Emotion 2020, 44, 1–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franklin, C.; Ding, X.; Kim, J.; Zhang, A.; Hai, A.H.; Jones, K.; Nachbaur, M.; O’Connor, A. Solution-focused brief therapy in community-based services: A meta-analysis of randomized controlled studies. Research on Social Work Practice 2024, 34, 265–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coulter, S. The applicability of two strengths-based systemic psychotherapy models for young people following Type 1 Trauma. Child Care in Practice 2014, 20, 48–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joubert, J.; Guse, T. A solution-focused brief therapy (SFBT) intervention model to facilitate hope and subjective well-being among trauma survivors. Journal of Contemporary Psychotherapy 2021, 51, 303–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ratner, H.; George, E.; Iveson, C. Solution focused brief therapy: 100 key points and techniques; Routledge: Hove, East Sussex, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- de Shazer, S.; Dolan, Y.; Korman, H.; Trepper, T.; McCollum, E.; Kim Berg, I. More than miracles: The state of the art of solution-focused brief therapy, 2nd ed.; Routledge: New York, 2021; p. 200. [Google Scholar]

- Gestsdóttir, S.; Urban, J.B.; Bowers, E.P.; Lerner, J.V.; Lerner, R.M. Intentional self-regulation, ecological assets, and thriving in adolescence: A developmental systems model. New Directions for Child and Adolescent Development 2011, 2011, 61–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gestsdóttir, S.; Geldhof, G.J.; Lerner, J.V.; Lerner, R.M. What drives positive youth development? Assessing intentional self-regulation as a central adolescent asset. International Journal of Developmental Science 2017, 11, 69–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Napolitano, C.M.; Bowers, E.P.; Gestsdóttir, S.; Chase, P.A. The development of intentional self-regulation in adolescence: Describing, explaining, and optimizing its link to positive youth development. In Advances in Child Development and Behavior, Lerner, R.M., Lerner, J.V., Benson, J.B., Eds.; JAI: 2011; Volume 41, pp. 19–38.

- Tidmarsh, G.; Thompson, J.L.; Quinton, M.L.; Cumming, J. Process evaluations of positive youth development programmes for disadvantaged young people: A systematic review. Journal of Youth Development 2022, 17, 106–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cumming, J.; Whiting, R.; Parry, B.J.; Clarke, F.J.; Holland, M.J.G.; Cooley, S.J.; Quinton, M.L. The My Strengths Training for Life program: Rationale, logic model, and description of a strengths-based intervention for young people experiencing homelessness. Evaluation and Program Planning 2022, 91, 102045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vealey, R. Future directions in psychological skills training. The Sport Psychologist 1998, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orlick, T. Pursuit of Excellence, 5th ed.; Human Kinetics: Champaign, IL, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Estanol, E.; Shepherd, C.; MacDonald, T. Mental skills as protective sttributes against eating disorder risk in dancers. Journal of Applied Sport Psychology 2013, 25, 209–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golby, J.; Wood, P. The effects of psychological skills training on mental toughness and psychological well-being of student-athletes. Psychology 2016, 07, 901–913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danish, S.J.; Forneris, T.; Wallace, I. Sport-based life skills programming in the schools. Journal of Applied School Psychology 2005, 21, 41–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharp, L.-A.; Woodcock, C.; Holland, M.J.G.; Cumming, J.; Duda, J.L. A qualitative evaluation of the effectiveness of a mental skills training program for youth athletes. The Sport Psychologist 2013, 27, 219–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cumming, J.; Clarke, F.J.; Holland, M.J.G.; Parry, B.J.; Quinton, M.L.; Cooley, S.J. A feasibility study of the My Strengths Training for Life (MST4Life) Program for young people experiencing homelessness. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 2022, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Holland, M.J.G.; Cooley, S.J.; Cumming, J. Understanding and assessing young athletes’ psychological needs. In Sport psychology for young athletes, 1st ed.; Knight, C.J., Harwood, C.G., Gould, D., Eds.; Routledge: London, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Hanrahan, S.J. LifeMatters: Using physical activities and games to enhance the self-concept and well-being of disadvantaged youth. In Positive Psychology in Sport and Physical Activity, 1st ed.; Brady, A., Grenville-Cleave, B., Eds.; Routledge: London, 2017; Volume 7, pp. 170–181. [Google Scholar]

- Fisher, R. Thinking about thinking: Developing metacognition in children. Early Child Development and Care 1998, 141, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holland, M.J.; Woodcock, C.; Cumming, J.; Duda, J.L. Mental qualities and employed mental techniques of young elite team sport athletes. Journal of Clinical Sport Psychology 2010, 4, 19–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vealey, R. Mental skills training in sport. In Handbook of Sport Psychology, 3 ed.; Tenenbaum, G., Eklund, R., Eds.; John Wiley and Sons: Chichester, 2007; pp. 287–309. [Google Scholar]

- Cooley, S.J.; Quinton, M.L.; Holland, M.J.G.; Parry, B.J.; Cumming, J. The experiences of homeless youth when using strengths profiling to identify their character strengths. Frontiers in Psychology 2019, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanrahan, S.J. Using games to enhance life satisfaction and self-worth of orphans, teenagers living in poverty, and ex-gang members in Latin America. In Case studies in sport development: Contemporary stories promoting health, peace and social justice, Schinke, R.J., Lidor, R., Eds.; Fitness Information Technology: Morgantown, WV, 2013; pp. 89–101. [Google Scholar]

- Ryan, R.M.; Deci, E.L. Self-determination theory and the facilitation of intrinsic motivation, social development, and well-being. Am Psychol 2000, 55, 68–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lerner, R.M.; Lerner, J.V.; Almerigi, J.B.; Theokas, C.; Phelps, E.; Gestsdóttir, S.; Naudeau, S.; Jelicic, H.; Alberts, A.; Ma, L.; et al. Positive youth development, participation in community youth development programs, and community contributions of fifth-grade adolescents: Findings from the first wave of the 4-H study of positive youth development. The Journal of Early Adolescence 2005, 25, 17–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanrahan, S.J.; Francke Ramm, M.D.L. Improving life satisfaction, self-concept, and happiness of former gang members using games and psychological skills training. Journal of Sport for Development 2015, 3, 41–47. [Google Scholar]

- Catalano, R.F.; Skinner, M.L.; Alvarado, G.; Kapungu, C.; Reavley, N.; Patton, G.C.; Jessee, C.; Plaut, D.; Moss, C.; Bennett, K.; et al. Positive youth development programs in low- and middle-income countries: A conceptual framework and systematic review of efficacy. J Adolesc Health 2019, 65, 15–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McMahon, M.G.; Hanrahan, S.J. Life Matters: Exploring the influence of games and mental skills on relatedness and social anxiety levels in disengaged adolescent students. Journal of Applied Sport Psychology 2019, 32, 205–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanrahan, S.J.; Tshube, T. Developing Batswana coaches’ competencies through the LifeMatters programme: Teaching mental skills through games. Botswana Notes and Records 2018, 50, 189–198. [Google Scholar]

- Page, D.; Hanrahan, S.; Buckley, L. Positive youth development program for adolescents with disabilities: A pragmatic trial. International Journal of Disability, Development and Education 2024, 71, 451–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, D.T.; Hanrahan, S.; Buckley, L. Real-world trial of positive youth development program “LifeMatters” with South African adolescents in a low-resource setting. Children and Youth Services Review 2023, 146, 106818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mygind, L.; Kjeldsted, E.; Hartmeyer, R.; Mygind, E.; Bølling, M.; Bentsen, P. Mental, physical and social health benefits of immersive nature-experience for children and adolescents: A systematic review and quality assessment of the evidence. Health & Place 2019, 58, 102136. [Google Scholar]

- Dewey, J. Dewey, J. Experience and Education; Macmillian: New York, NY, 1963 (Original work published 1938).

- Kolb, D.A. Experiential learning: Experience as the source of learning and development.; Prentice-Hall: Englewood Cliffs, New Jersey, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Quinton, M.L.; Tidmarsh, G.; Parry, B.J.; Cumming, J. A Kirkpatrick Model Process Evaluation of Reactions and Learning from My Strengths Training for Life™. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 2022, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parry, B.J.; Quinton, M.; Cumming, J. Mental skills training toolkit: A resource for strengths-based development; University of Birmingham, 2020.

- Quinton, M.; Parry, B.J.; Cumming, J. Mental skills training toolkit: Ensuring psychologically informed delivery; University of Birmingham, 2020.

- Clarke, F.J.; Parry, B.J.; Quinton, M.; Cumming, J. Mental skills training commissioning and evaluation toolkit: Improving outcomes in young people experiencing homelessness; University of Birmingham, 2020.

- Lethem, J. Brief Solution Focused Therapy. Child and Adolescent Mental Health 2002, 7, 189–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tidmarsh, G.; Whiting, R.; Thompson, J.L.; Cumming, J. Assessing the fidelity of delivery style of a mental skills training programme for young people experiencing homelessness. Evaluation and Program Planning 2022, 94, 102150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parry, B.J.; Quinton, M.L.; Holland, M.J.G.; Thompson, J.L.; Cumming, J. Improving outcomes in young people experiencing homelessness with My Strengths Training for Life (TM) (MST4Life (TM)): A qualitative realist evaluation. Children and Youth Services Review 2021, 121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parry, B.J.; Thompson, J.L.; Holland, M.J.G.; Cumming, J. Promoting personal growth in young people experiencing homelessness through an outdoors-based program. Journal of Youth Development 2021, 16, 157–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quinton, M.L.; Clarke, F.J.; Parry, B.J.; Cumming, J. An evaluation of My Strengths Training for Life for improving resilience and well-being of young people experiencing homelessness. J Community Psychol 2021, 49, 1296–1314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tidmarsh, G.; Thompson, J.L.; Quinton, M.L.; Parry, B.J.; Cooley, S.J.; Cumming, J. A platform for youth voice in MST4Life: A vital component of process evaluations. Sport and Exercise Psychology Review 2022, 17, 73–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jabbour, L.; Siu, J. Outcome and economic evaluation of the My Strengths Training for Life™ programme with St Basils; University of Birmingham: 2019.

- Cumming, J.; Clarke, F.J.; Holland, M.J.G.; Parry, B.J.; Quinton, M.L.; Cooley, S.J. A Feasibility Study of the My Strengths Training for Life™ (MST4Life™) Program for Young People Experiencing Homelessness. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 2022, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rapp, C.A.; Saleebey, D.; Sullivan, W.P. The future of strengths-based social work. Advances in social work: Special issue on the futures of social work 2006, 6, 79–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quinton, M.L.; Tidmarsh, G.; Parry, B.J.; Cumming, J. A Kirkpatrick model process evaluation of reactions and learning from my strengths training for life™. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 2022, 19, 11320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Page, D.T. The LifeMatters program implemented in South Africa. The University of Queensland, 2022.

- Geldhof, G.J.; Bowers, E.P.; Boyd, M.J.; Mueller, M.K.; Napolitano, C.M.; Schmid, K.L.; Lerner, J.V.; Lerner, R.M. Creation of short and very short measures of the Five Cs of Positive Youth Development. Journal of Research on Adolescence 2014, 24, 163–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomez-Baya, D.; Martin-Barrado, A.D.; Muñoz-Parralo, M.; Roh, M.; Garcia-Moro, F.J.; Mendoza-Berjano, R. The 5Cs of positive youth development and risk behaviors in a sample of spanish emerging adults: A partial mediation analysis of gender differences. European Journal of Investigation in Health, Psychology and Education 2023, 13, 2410–2427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kirkpatrick, J.; Kirkpatrick, W. An introduction to the new world Kirkpatrick model. Available online: https://www.kirkpatrickpartners.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/11/Introduction-to-The-New-World-Kirkpatrick%C2%AE-Model.pdf (accessed on 12 July 2024).

- Sukhera, J. Narrative reviews: Flexible, rigorous, and practical. Journal of Graduate Medical Education 2022, 14, 414–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| 1 | Abbreviations: MST, mental skills training; MST4Life™, My Strengths Training™ for Life; ACEs, adverse childhood experiences; SFBT, solution-focused brief therapy; PYD, positive youth development; HPA, hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal; SDT, Self-determination theory; BPNT, basic psychological needs theory; NEET, not in education, employment, or training; EET, education, employment, or training; CARES, Competence, Autonomy, Relatedness, Engagement, Structure; PYD-SF, Positive Youth Development Short Form; RCT, randomised control trial. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).