Submitted:

31 July 2024

Posted:

31 July 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

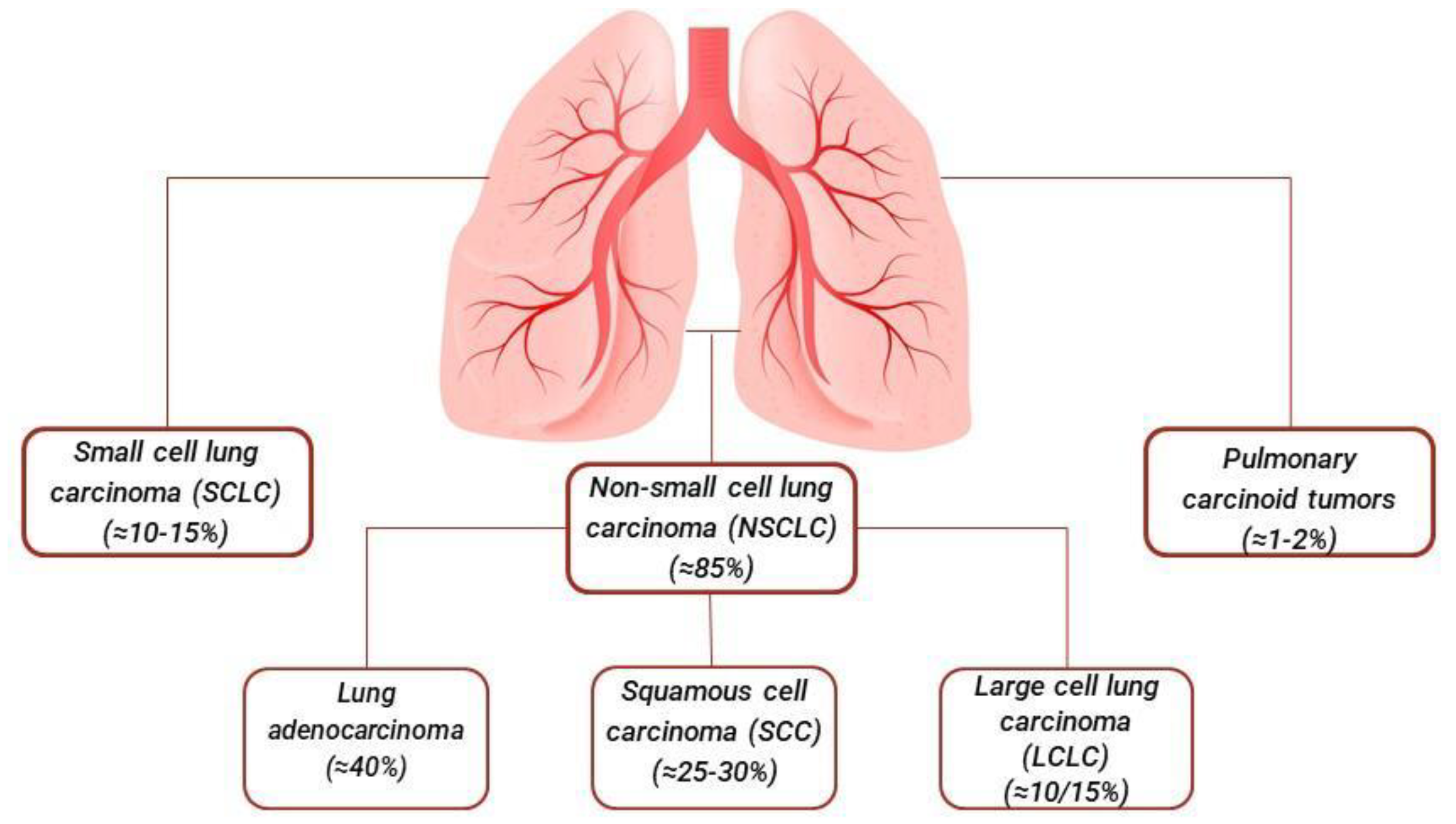

1. Introduction

1.1. Lung Adenocarcinoma

1.2. Squamous Cell Carcinoma

1.3. Large Cell Lung Carcinoma

1.4. Small Cell Lung Cancer

1.5. Other Less Common Types of Lung Cancer: Pulmonary Carcinoid Tumors

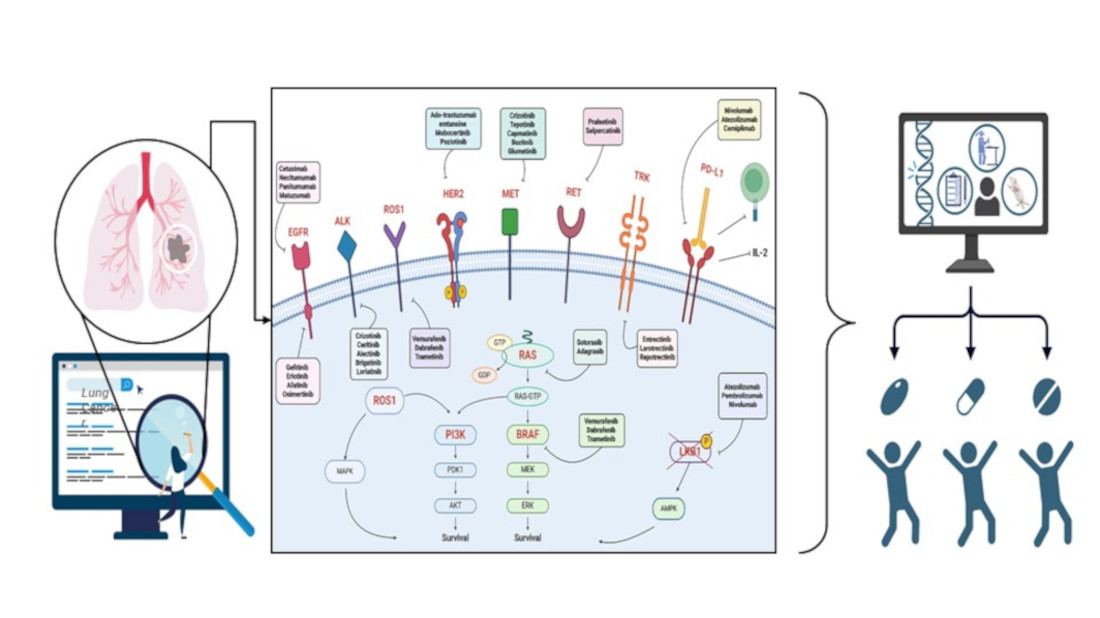

2. Genetic Landscape of Lung Cancer

2.1. Main Driver Genes

2.2. Emerging Biomarkers

3. Therapies Based on Genetic Information

3.1. Targeted Therapy

3.2. Immunotherapy

3.3. Emerging Therapy

4. Challenges and Future Prospects

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- S. H.; F. J., Global Cancer Statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN Estimates of Incidence and Mortality Worldwide for 36 Cancers in 185 Countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 2021;71(3):209-249. [CrossRef]

- S. RL.; M. KD., Cancer statistics, 2020. CA Cancer J Clin. 2020, 70(1):7-30. [CrossRef]

- GBD 2015 Tobacco Collaborators; Smoking prevalence and attributable disease burden in 195 countries and territories, 1990-2015: a systematic analysis from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2015 Lancet. 2017 7;390(10103):1644. [CrossRef]

- P. HA.; I.B., The association between smoking quantity and lung cancer in men and women. Chest. 2013, 143(1):123-129. [CrossRef]

- D. R.; P. R., Mortality in relation to smoking: 50 years' observations on male British doctors. BMJ. 2004, 26;328(7455):1519. [CrossRef]

- S. JM; A.E., Lung cancer in never smokers: clinical epidemiology and environmental risk factors. Clin Cancer Res. 2009, 15;15(18):5626-45. [CrossRef]

- S. D.; Z. P., Occupational exposure and lung cancer. J Thorac Dis. 2013, 5 Suppl 4(Suppl 4):S440-5. [CrossRef]

- L. JH.; B. JD J., Lung cancer in radon-exposed miners and estimation of risk from indoor exposure. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1995, 7;87(11):817-27. [CrossRef]

- T. WD.; B. E., Introduction to The 2015 World Health Organization Classification of Tumors of the Lung, Pleura, Thymus, and Heart. J Thorac Oncol. 2015, 10(9):1240-1242. [CrossRef]

- E. DS.; W. DE., Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer, Version 3.2022, NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2022, 20(5):497-530. [CrossRef]

- T. WD.; B. E., International association for the study of lung cancer/american thoracic society/european respiratory society international multidisciplinary classification of lung adenocarcinoma. J Thorac Oncol. 2011, 6(2):244-85. [CrossRef]

- N. M.; M. A., Small adenocarcinoma of the lung. Histologic characteristics and prognosis. Cancer. 1995, 15;75(12):2844-52. [CrossRef]

- C. S.; Z. G, Lung cancer in never smokers--a review. Eur J Cancer. 2012, 48(9):1299-311. [CrossRef]

- R. R.; C. S., Lung cancer staging: a concise update. Eur Respir J. 2018, 17;51(5):1800190. [CrossRef]

- M. N.; S. B. Lung adenocarcinoma presenting as intramedullary spinal cord metastasis: Case report and review of literature. J Clin Neurosci. 2018, 52:124-131. [CrossRef]

- P. F.; R. S., State of the art and new perspectives in surgical treatment of lung cancer: a narrative review. Transl Cancer Res. 2022, 11(10):3869-3875. [CrossRef]

- L. X.; W. J., Optimal Initial Time Point of Local Radiotherapy for Unresectable Lung Adenocarcinoma: A Retrospective Analysis on Overall Arrangement of Local Radiotherapy in Advanced Lung Adenocarcinoma. Front Oncol. 2022, 10;12:793190. [CrossRef]

- L. D.; N. N., Customized Adjuvant Chemotherapy Based on Biomarker Examination May Improve Survival of Patients Completely Resected for Non-small-cell Lung Cancer. Anticancer Res. 2017, 37(5):2501-2507. [CrossRef]

- E. GJ.; W. DE., Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer, Version 4.2024, NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2024, 22(4):249-274. [CrossRef]

- B. JE.; V. K., Targeting Metabolism to Improve the Tumor Microenvironment for Cancer Immunotherapy. Mol Cell. 2020, 18;78(6):1019-1033. [CrossRef]

- J. N.; X. X., Exploring the survival prognosis of lung adenocarcinoma based on the cancer genome atlas database using artificial neural network. Medicine (Baltimore). 2019, 98(20):e15642. [CrossRef]

- Cancer Genome Atlas Research Network; Comprehensive genomic characterization of squamous cell lung cancers. Nature. 2012, 8;491(7423):288. [CrossRef]

- T. WD.; B. E., The 2015 World Health Organization Classification of Lung Tumors: Impact of Genetic, Clinical and Radiologic Advances Since the 2004 Classification. J Thorac Oncol. 2015, 10(9):1243-1260. [CrossRef]

- S. BR.; G. DP., Squamous Cell Lung Cancer. 2024, 14. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls.

- S. GA.; G. AV., Diagnosis and management of lung cancer, 3rd ed: American College of Chest Physicians evidence-based clinical practice guidelines. Chest. 2013, 143(5 Suppl):e211S-e250S. [CrossRef]

- G. C., A. A., Recent issues in first-line treatment of advanced non-small-cell lung cancer: Results of an International Expert Panel Meeting of the Italian Association of Thoracic Oncology. Lung Cancer. 2010, 68(3):319-31. [CrossRef]

- Z. K., C. H., Treatment options and prognosis of patients with lung squamous cell cancer in situ: a comparative study of lung adenocarcinoma in situ and stage IA lung squamous cell cancer. Transl Lung Cancer Res. 2023, 30;12(6):1276-1292. [CrossRef]

- S. LM.; Large-cell carcinoma of the lung: a diagnostic category redefined by immunohistochemistry and genomics. Curr Opin Pulm Med. 2014, 20(4):324-31. [CrossRef]

- C. A.; The fine structure of large cell undifferentiated carcinoma of the lung. Evidence for its relation to squamous cell carcinomas and adenocarcinomas. Hum Pathol. 1978, 9(2):143-56. [CrossRef]

- A. KS.; T. LD., Larg cell carcinoma of the lung. Ultrastructural differentiation and clinicopathologic correlations. Cancer. 1985, 1;56(7):1618-23. [CrossRef]

- M. JE.; S. SD., Cigarette smoking and large cell carcinoma of the lung. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 1997, 6(7):477-80. [PubMed]

- X. L.; J. Y., Clinical characteristics and prognosis of pulmonary large cell carcinoma: A population-based retrospective study using SEER data. Thorac Cancer. 2020, 11(6):1522-1532. [CrossRef]

- T. Q.; Z. L., Clinical characteristics and treatments of large cell lung carcinoma: a retrospective study using SEER data. Transl Cancer Res. 2020, 9(3):1455-1464. [CrossRef]

- P. G.; B. M., Large cell carcinoma of the lung: a tumor in search of an author. A clinically oriented critical reappraisal. Lung Cancer. 2015, 87(3):226-31. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- D. M,; B. L., Diagnostic procedures for non-small-cell lung cancer (NSCLC): recommendations of the European Expert Group. Thorax. 2016, 71(2):177-84. [CrossRef]

- A.; H. K., Prospective study of adjuvant chemotherapy for pulmonary large cell neuroendocrine carcinoma. Ann Thorac Surg. 2006, 82(5):1802-7. [CrossRef]

- G,, AF.; B, PA. , Small-cell lung cancer: what we know, what we need to know and the path forward. Nat Rev Cancer. 2017, 17(12):725-737. [CrossRef]

- K. GP.; L. BW, NCCN Guidelines Insights: Small Cell Lung Cancer, Version 2.2018. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2018, 16(10):1171-1182. [CrossRef]

- W. S,; Z. S, Current Diagnosis and Management of Small-Cell Lung Cancer. Mayo Clin Proc. 2019, 94(8):1599-1622. [CrossRef]

- D. AC,; F. M., Small-cell lung cancer: ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up☆. Ann Oncol. 2021, 32(7):839-853. [CrossRef]

- F. M.; D.R. D., Small-cell lung cancer (SCLC): ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann Oncol. 2013, 24 Suppl 6:vi99-105. [CrossRef]

- K. K.; V. S., Small Cell Lung Carcinoma: Current Diagnosis, Biomarkers, and Treatment Options with Future Perspectives. Biomedicines. 2023, 13;11(7):1982. [CrossRef]

- D. AC.; F.M, Small-cell lung cancer: ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up☆. Ann Oncol. 2021 Jul;32(7):839-853. [CrossRef]

- L. SV.; R. M., Updated Overall Survival and PD-L1 Subgroup Analysis of Patients With Extensive-Stage Small-Cell Lung Cancer Treated With Atezolizumab, Carboplatin, and Etoposide (IMpower133). J Clin Oncol. 2021, 20;39(6):619-630. [CrossRef]

- C. ME; B. E.,. Pulmonary neuroendocrine (carcinoid) tumors: European Neuroendocrine Tumor Society expert consensus and recommendations for best practice for typical and atypical pulmonary carcinoids. Ann Oncol. 2015, 26(8):1604-20. [CrossRef]

- S. M.; B. S., Gene Expression Profiling of Lung Atypical Carcinoids and Large Cell Neuroendocrine Carcinomas Identifies Three Transcriptomic Subtypes with Specific Genomic Alterations. J Thorac Oncol. 2019, 14(9):1651-1661. [CrossRef]

- H. AE.; M. AM, Neuroendocrine Tumors of the Lung: Current Challenges and Advances in the Diagnosis and Management of Well-Differentiated Disease. J Thorac Oncol. 2017, 12(3):425-436. [CrossRef]

- G. M.;,M. JM., Prognostic factors in neuroendocrine lung tumors: a Spanish Multicenter Study. Spanish Multicenter Study of Neuroendocrine Tumors of the Lung of the Spanish Society of Pneumonology and Thoracic Surgery (EMETNE-SEPAR). Ann Thorac Surg. 2000, 70(1):258-63. [CrossRef]

- V. SD.;, N. A, Emerging Immunotherapeutic and Diagnostic Modalities in Carcinoid Tumors. Molecules. 2023, 22;28(5):2047. [CrossRef]

- Z. Y.; W. DC., Genome analyses identify the genetic modification of lung cancer subtypes. Semin Cancer Biol. 2017, 42:20-30. [CrossRef]

- S. Y.; F. KM., Molecular genetics of lung cancer. Annu Rev Med. 2003, 54:73-87. [CrossRef]

- C. MB.; C. PP., Clinical potential of gene mutations in lung cancer. Clin Transl Med. 2015, 4(1):33. [CrossRef]

- B. P.; H. P., Genetics of lung-cancer susceptibility. Lancet Oncol. 2011, 12(4):399-408. [CrossRef]

- L. TJ.; B. DW., Activating mutations in the epidermal growth factor receptor underlying responsiveness of non-small-cell lung cancer to gefitinib. N Engl J Med. 2004, 20;350(21):2129-39. [CrossRef]

- K. T.; Y. Y., Prognostic implication of EGFR, KRAS, and TP53 gene mutations in a large cohort of Japanese patients with surgically treated lung adenocarcinoma. J Thorac Oncol. 2009, 4(1):22-9. [CrossRef]

- M. T.; Y. Y. Mutations of the epidermal growth factor receptor gene and related genes as determinants of epidermal growth factor receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitors sensitivity in lung cancer. Cancer Sci. 2007, 98(12):1817-24. [CrossRef]

- M. SW.; K. MN., Fusion of a kinase gene, ALK, to a nucleolar protein gene, NPM, in non-Hodgkin's lymphoma. Science. 1994, 20;267(5196):316-7. [CrossRef]

- S. M.; C. YL., Identification of the transforming EML4-ALK fusion gene in non-small-cell lung cancer. Nature. 2007, 2;448(7153):561-6. [CrossRef]

- S. M.; T. S., A mouse model for EML4-ALK-positive lung cancer. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008, 16;105(50):19893-7. [CrossRef]

- T. K., C. YL., KIF5B-ALK, a novel fusion oncokinase identified by an immunohistochemistry-based diagnostic system for ALK-positive lung cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2009, 1;15(9):3143-9. [CrossRef]

- D. X.; S. Y., ALK-rearrangement in non-small-cell lung cancer (NSCLC). Thorac Cancer. 2018, 9(4):423-430. [CrossRef]

- T. Y., S. M., KLC1-ALK: a novel fusion in lung cancer identified using a formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded tissue only. PLoS One. 2012, 7(2):e31323. [CrossRef]

- C. PL; M. P., Prevalence and natural history of ALK positive non-small-cell lung cancer and the clinical impact of targeted therapy with ALK inhibitors. Clin Epidemiol. 2014, 20;6:423-32. [CrossRef]

- C. AD.; D. CJ., Ras family signaling: therapeutic targeting. Cancer Biol Ther. 2002, 1(6):599-606. [CrossRef]

- P. W.; G. N., New driver mutations in non-small-cell lung cancer. Lancet Oncol. 2011, 12(2):175-80. [CrossRef]

- P. IA.; L. PD., A comprehensive survey of Ras mutations in cancer. Cancer Res. 2012, 15;72(10):2457-67. [CrossRef]

- W. X.; R. B., Association between Smoking History and Tumor Mutation Burden in Advanced Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer. Cancer Res. 2021, 1;81(9):2566-2573. [CrossRef]

- T. J.; The clinical relevance of KRAS gene mutation in non-small-cell lung cancer. Curr Opin Oncol. 2014, 26(2):138-44. [CrossRef]

- G. A.; R. P., Current therapy of KRAS-mutant lung cancer. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 2020, 39(4):1159-1177. [CrossRef]

- B. EH., A. TC., Update on emerging biomarkers in lung cancer. J Thorac Dis. 2019, 11(Suppl 1):S81-S88. [CrossRef]

- J. H.; W. Z., Mutations in BRAF and KRAS converge on activation of the mitogen-activated protein kinase pathway in lung cancer mouse models. Cancer Res. 2007, 15;67(10):4933-9. [CrossRef]

- R. MJ.; C. MH., Mitogen-activated protein kinase pathways. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 1997, 9(2):180-6. [CrossRef]

- W. PT; G. MJ., Mechanism of activation of the RAF-ERK signaling pathway by oncogenic mutations of B-RAF. Cell. 2004, 19;116(6):855-67. [CrossRef]

- D. H., B. GR., Mutations of the BRAF gene in human cancer. Nature. 2002, 27;417(6892):949-54. [CrossRef]

- P. PK.; A. ME., Clinical characteristics of patients with lung adenocarcinomas harboring BRAF mutations. J Clin Oncol. 2011, 20;29(15):2046-51. [CrossRef]

- F. KT.; M. G., BRAF, a target in melanoma: implications for solid tumor drug development. Cancer. 2010, 1;116(21):4902-13. [CrossRef]

- W. PT.; G. MJ., Mechanism of activation of the RAF-ERK signaling pathway by oncogenic mutations of B-RAF. Cell. 2004, 19;116(6):855-67. [CrossRef]

- Y. Z.; T. NM., BRAF Mutants Evade ERK-Dependent Feedback by Different Mechanisms that Determine Their Sensitivity to Pharmacologic Inhibition. Cancer Cell. 2015, 14;28(3):370-83. [CrossRef]

- Y. Z.; Y. R., Tumours with class 3 BRAF mutants are sensitive to the inhibition of activated RAS. Nature. 2017, 10;548(7666):234-238.

- D. KD., L. AT., Identifying and targeting ROS1 gene fusions in non-small cell lung cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2012, 1;18(17):4570-9. [CrossRef]

- R. K.; G. A., Global survey of phosphotyrosine signaling identifies oncogenic kinases in lung cancer. Cell. 2007, 14;131(6):1190-203. [CrossRef]

- B. AH.; A. SL., Chromosome 3 anomalies investigated by genome wide SNP analysis of benign, low malignant potential and low grade ovarian serous tumours. PLoS One. 2011, 6(12):e28250. [CrossRef]

- L. J.; L. SE., Identification of ROS1 rearrangement in gastric adenocarcinoma. Cancer. 2013, 1;119(9):1627-35. [CrossRef]

- L. JJ.; S. AT., Recent Advances in Targeting ROS1 in Lung Cancer. J Thorac Oncol. 2017, 12(11):1611-1625. [CrossRef]

- B. K.; S. AT., ROS1 rearrangements define a unique molecular class of lung cancers. J Clin Oncol. 2012, 10;30(8):863-70. [CrossRef]

- U. A.; D. B. M., ROS1 fusions in cancer: a review. Future Oncol. 2016, 12(16):1911-28. [CrossRef]

- T. K.;, S. M., RET, ROS1 and ALK fusions in lung cancer. Nat Med. 2012, 12;18(3):378-81. [CrossRef]

- R. R. Jr; ROS1 protein-tyrosine kinase inhibitors in the treatment of ROS1 fusion protein-driven non-small cell lung cancers. Pharmacol Res. 2017, 121:202-212. [CrossRef]

- S. A.; C. F., Targeted therapies in non-small cell lung cancer: a focus on ALK/ROS1 tyrosine kinase inhibitors. Expert Rev Anticancer Ther. 2018, 18(1):71-80. [CrossRef]

- P. ER.; V. P., Comparison of Different Antibody Clones for Immunohistochemistry Detection of Programmed Cell Death Ligand 1 (PD-L1) on Non-Small Cell Lung Carcinoma. Appl Immunohistochem Mol Morphol. 2018, 26(2):83-93. [CrossRef]

- L. G.; F. X., Prognostic significance of PD-L1 expression and tumor infiltrating lymphocyte in surgically resectable non-small cell lung cancer. Oncotarget. 2017, 12;8(48):83986-83994. [CrossRef]

- S. M,; S. S., Clinical and pathologic features of lung cancer expressing programmed cell death ligand 1 (PD-L1). Lung Cancer. 2016, 98:69-75. [CrossRef]

- S. X.; W. S., PD-L1 expression in lung adenosquamous carcinomas compared with the more common variants of non-small cell lung cancer. Sci Rep. 2017, 7;7:46209. [CrossRef]

- S. KA.; F. LJ., PD-1 inhibits T-cell receptor induced phosphorylation of the ZAP70/CD3zeta signalosome and downstream signaling to PKCtheta. FEBS Lett. 2004, 10;574(1-3):37-41. [CrossRef]

- P. DM.L; The blockade of immune checkpoints in cancer immunotherapy. Nat Rev Cancer. 2012, 22;12(4):252-64. [CrossRef]

- D. P.; X. Y., Intrinsic PD-L1 Signaling in Cancer Initiation, Development and Treatment: Beyond Immune Evasion. Front Oncol. 2018, 19;8:386. [CrossRef]

- G. A.; S. DS., Interferon Receptor Signaling Pathways Regulating PD-L1 and PD-L2 Expression. Cell Rep. 2019, 10;29(11):3766. [CrossRef]

- R. NA., H. MD., Cancer immunology. Mutational landscape determines sensitivity to PD-1 blockade in non-small cell lung cancer. Science. 2015, 3;348(6230):124-8. [CrossRef]

- C. S.; P. L., CD274 (PDL1) and JAK2 genomic amplifications in pulmonary squamous-cell and adenocarcinoma patients. Histopathology. 2018, 72(2):259-269. [CrossRef]

- I. Y.; Y. K., Clinical significance of PD-L1 and PD-L2 copy number gains in non-small-cell lung cancer. Oncotarget. 2016, 31;7(22):32113-28. [CrossRef]

- K. K.; S. Y., Aberrant PD-L1 expression through 3'-UTR disruption in multiple cancers. Nature. 2016, 16;534(7607):402-6. [CrossRef]

- C. L.; Z. XZ., PD-L1 as a predictive factor for non-small-cell lung cancer prognosis. Lancet Oncol. 2024, ;25(6):e233. [CrossRef]

- T. JH.; Y. SF., MET Amplification and Exon 14 Splice Site Mutation Define Unique Molecular Subgroups of Non-Small Cell Lung Carcinoma with Poor Prognosis. Clin Cancer Res. 2016, 15;22(12):3048-56. [CrossRef]

- B. C.; B. W.,. Met, metastasis, motility and more. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2003, ;4(12):915-25. [CrossRef]

- S. L.; D. FM., Germline and somatic mutations in the tyrosine kinase domain of the MET proto-oncogene in papillary renal carcinomas. Nat Genet. 1997, 16(1):68-73. [CrossRef]

- S. M.; M. A., screening and molecular characterization of MET alterations in non-small cell lung cancer. Clin Transl Oncol. 2018, 20(7):881-888. [CrossRef]

- R. T.; L. Y., The race to target MET exon 14 skipping alterations in non-small cell lung cancer: The Why, the How, the Who, the Unknown, and the Inevitable. Lung Cancer. 2017, 103:27-37. [CrossRef]

- A. MM.; O. GR., MET Exon 14 Mutations in Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer Are Associated With Advanced Age and Stage-Dependent MET Genomic Amplification and c-Met Overexpression. J Clin Oncol. 2016, 1;34(7):721-30. [CrossRef]

- S. AB.; F. GM., Characterization of 298 Patients with Lung Cancer Harboring MET Exon 14 Skipping Alterations. J Thorac Oncol. 2016, 11(9):1493-502. [CrossRef]

- D. A.; MET Exon 14 Alterations in Lung Cancer: Exon Skipping Extends Half-Life. Clin Cancer Res. 2016, 15;22(12):2832-4. [CrossRef]

- O. K.; S. H., Met gene copy number predicts the prognosis for completely resected non-small cell lung cancer. Cancer Sci. 2008, 99(11):2280-5. [CrossRef]

- R. S.; M. A., MET Signaling Pathways, Resistance Mechanisms, and Opportunities for Target Therapies. Int J Mol Sci. 2022, 11;23(22):13898. [CrossRef]

- C. F.; M. A., Increased MET gene copy number negatively affects survival of surgically resected non-small-cell lung cancer patients. J Clin Oncol. 2009, 1;27(10):1667-74. [CrossRef]

- S. HU.; S. AM., MET amplification status in therapy-naïve adeno- and squamous cell carcinomas of the lung. Clin Cancer Res. 2015, 15;21(4):907-15. [CrossRef]

- C. M.; S. I, KIF5B-MET fusion variant in non-small cell lung cancer. Pulmonology. 2022, 28(4):315-316. [CrossRef]

- S. D.; W. W., Identification of MET fusions as novel therapeutic targets sensitive to MET inhibitors in lung cancer. J Transl Med. 2023, 25;21(1):150. [CrossRef]

- S. D.; X. X., MET fusions are targetable genomic variants in the treatment of advanced malignancies. Cell Commun Signal. 2024, 9;22(1):20. [CrossRef]

- L. X., J. Y., Next-Generation Sequencing of Pulmonary Sarcomatoid Carcinoma Reveals High Frequency of Actionable MET Gene Mutations. J Clin Oncol. 2016, 10;34(8):794-802. [CrossRef]

- T. M.; R. J., Activation of a novel human transforming gene, ret, by DNA rearrangement. Cell. 1985, 42(2):581-8. [CrossRef]

- I. CF.; Structure and physiology of the RET receptor tyrosine kinase. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2013, 1;5(2):a009134. [CrossRef]

- S. JS.; J. YS., transcriptional landscape and mutational profile of lung adenocarcinoma. Genome Res. 2012, 22(11):2109-19. [CrossRef]

- T. M.; RET receptor signaling: Function in development, metabolic disease, and cancer. Proc Jpn Acad Ser B Phys Biol Sci. 2022, 98(3):112-125. [CrossRef]

- K. T.; I. H., KIF5B-RET fusions in lung adenocarcinoma. Nat Med. 2012, 12;18(3):375-7. [CrossRef]

- J. YS., L. WC., A transforming KIF5B and RET gene fusion in lung adenocarcinoma revealed from whole-genome and transcriptome sequencing. Genome Res. 2012, 22(3):436-45. [CrossRef]

- K. T.; N. T., Beyond ALK-RET, ROS1 and other oncogene fusions in lung cancer. Transl Lung Cancer Res. 2015, 4(2):156-64. [CrossRef]

- L. D.; C. M., Identification of new ALK and RET gene fusions from colorectal and lung cancer biopsies. Nat Med. 2012, 12;18(3):382-4. [CrossRef]

- W. R.; H. H., RET fusions define a unique molecular and clinicopathologic subtype of non-small-cell lung cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2012, 10;30(35):4352-9. [CrossRef]

- R. M.; C. G. M., NTRK gene fusion testing and management in lung cancer. Cancer Treat Rev. 2024, 127:102733. [CrossRef]

- A. A.; S. A., Tropomyosin receptor kinase (TRK) biology and the role of NTRK gene fusions in cancer. Ann Oncol. 2019, 1;30(Suppl_8):viii5-viii15. [CrossRef]

- A. JC.; W. SH., Neurotrophin signaling: many exciting surprises! Cell Mol Life Sci. 2006, 63(13):1523-37. [CrossRef]

- R. EY.; G. DA., TRK Fusions Are Enriched in Cancers with Uncommon Histologies and the Absence of Canonical Driver Mutations. Clin Cancer Res. 2020, 1;26(7):1624-1632. [CrossRef]

- M. CA.; B. DC., A review of NTRK fusions in cancer. Ann Med Surg (Lond). 2022, 13;79:103893. [CrossRef]

- V. A.; L. AT., TRKing down an old oncogene in a new era of targeted therapy. Cancer Discov. 2015, 5(1):25-34. [CrossRef]

- W. CB.; K. MG., Genomic context of NTRK1/2/3 fusion-positive tumours from a large real-world population. NPJ Precis Oncol. 2021, 5(1):86. [CrossRef]

- H. G.; S. FC., NTRK fusions in lung cancer: From biology to therapy. Lung Cancer. 2021, 161:108-113. [CrossRef]

- T. AC.; I. M., Brain Metastases in Lung Cancers with Emerging Targetable Fusion Drivers. Int J Mol Sci. 2020, 21(4):1416. [CrossRef]

- L. F.; W. Y., NTRK Fusion in Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer: Diagnosis, Therapy, and TRK Inhibitor Resistance. Front Oncol. 2022, 12:864666. [CrossRef]

- K. S.; B. AG., Phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase mutations identified in human cancer are oncogenic. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005, 102(3):802-7. [CrossRef]

- O. GR., B. A., New targetable oncogenes in non-small-cell lung cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2013, 31(8):1097-104. [CrossRef]

- S. Y., V. VE., Oncogenic mutations of PIK3CA in human cancers. Cell Cycle. 2004, 3(10):1221-4. [CrossRef]

- H. CH.; M. D., The structure of a human p110alpha/p85alpha complex elucidates the effects of oncogenic PI3Kalpha mutations. Science. 2007, 318(5857):1744-8. [CrossRef]

- J. F.; W. JJ., PIK3CA mutation H1047R is associated with response to PI3K/AKT/mTOR signaling pathway inhibitors in early-phase clinical trials. Cancer Res. 2013, 73(1):276-84. [CrossRef]

- K. O.; S. H., PIK3CA mutation status in Japanese lung cancer patients. Lung Cancer. 2006, 54(2):209-15. [CrossRef]

- C. JE.; A. ME, Paik PK, Lau C, Riely GJ, Pietanza MC, Zakowski MF, Rusch V, Sima CS, Ladanyi M, Kris MG. Coexistence of PIK3CA and other oncogene mutations in lung adenocarcinoma-rationale for comprehensive mutation profiling. Mol Cancer Ther. 2012, 11(2):485-91. [CrossRef]

- W. Y.; W. Y Clinical Significance of PIK3CA Gene in Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Biomed Res Int. 2020, 17;2020:3608241. [CrossRef]

- S. M.; B. M., mutations in non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC): genetic heterogeneity, prognostic impact and incidence of prior malignancies. Oncotarget. 2015, 6(2):1315-26. [CrossRef]

- W. L.; H. H., PIK3CA mutations frequently coexist with EGFR/KRAS mutations in non-small cell lung cancer and suggest poor prognosis in EGFR/KRAS wildtype subgroup. PLoS One. 2014, 9(2):e88291. [CrossRef]

- D. JM.; J. CB., Neu differentiation factor induces ErbB2 down-regulation and apoptosis of ErbB2-overexpressing breast tumor cells. Cancer Res. 1997, 57(17):3804-11.

- A. ME.; C. JE., Prevalence, clinicopathologic associations, and molecular spectrum of ERBB2 (HER2) tyrosine kinase mutations in lung adenocarcinomas. Clin Cancer Res. 2012, 18(18):4910-8. [CrossRef]

- H. FR.; V. M., Evaluation of HER-2/neu gene amplification and protein expression in non-small cell lung carcinomas. Br J Cancer. 2002, 86(9):1449-56. [CrossRef]

- L. BT.; R. DS., HER2 Amplification and HER2 Mutation Are Distinct Molecular Targets in Lung Cancers. J Thorac Oncol. 2016, 11(3):414-9. [CrossRef]

- K. V.; G. M., Effect of HER2/neu expression on survival in non-small-cell lung cancer. Clin Lung Cancer. 2001, 2(3):216-9. [CrossRef]

- A. ME.; C. JE., Nafa K, Roy-Chowdhuri S, Lau C, Zaidinski M, Paik PK, Zakowski MF, Kris MG, Ladanyi M. Prevalence, clinicopathologic associations, and molecular spectrum of ERBB2 (HER2) tyrosine kinase mutations in lung adenocarcinomas. Clin Cancer Res. 2012, 18(18):4910-8. [CrossRef]

- M. J.; P. S., Lung cancer that harbors an HER2 mutation: epidemiologic characteristics and therapeutic perspectives. J Clin Oncol. 2013, 31(16):1997-2003. [CrossRef]

- T. K.; S. K., Prognostic and predictive implications of HER2/ERBB2/neu gene mutations in lung cancers. Lung Cancer. 2011, 74(1):139-44. [CrossRef]

- H. A.; M. D., A serine/threonine kinase gene defective in Peutz-Jeghers syndrome. Nature. 1998, 391(6663):184-7. [CrossRef]

- S. M.; P. P., Inactivation of LKB1/STK11 is a common event in adenocarcinomas of the lung. Cancer Res. 2002, 62(13):3659-62.

- C.J.; M. PP., Novel and natural knockout lung cancer cell lines for the LKB1/STK11 tumor suppressor gene. Oncogene. 2004, 23(22):4037-40. [CrossRef]

- J. H.; R. MR., LKB1 modulates lung cancer differentiation and metastasis. Nature. 2007, 448(7155):807-10. [CrossRef]

- S. DB.; S. RJ., The LKB1-AMPK pathway: metabolism and growth control in tumour suppression. Nat Rev Cancer. 2009, 9(8):563-75. [CrossRef]

- S. NJ.; K. AB., STK11 (LKB1) mutations in metastatic NSCLC: Prognostic value in the real world. PLoS One. 2020, 15(9):e0238358. [CrossRef]

- J. M.; W.S, Somatic STK11/LKB1 mutations to confer resistance to immune checkpoint inhibitors as monotherapy or in combination in advanced NSCLC.. JCO. 2018, 36, 3028-3028. [CrossRef]

- S. F.; G. ME., STK11/LKB1 Mutations and PD-1 Inhibitor Resistance in KRAS-Mutant Lung Adenocarcinoma. Cancer Discov. 2018, 8(7):822-835. [CrossRef]

- S. F.; A. K. C., Association of STK11/LKB1 genomic alterations with lack of benefit from the addition of pembrolizumab to platinum doublet chemotherapy in non-squamous non-small cell lung cancer.. JCO. 2019, 37, 102-102. [CrossRef]

- M. B.; H. S., The Importance of STK11/LKB1 Assessment in Non-Small Cell Lung Carcinomas. Diagnostics (Basel). 2021, 11(2):196. [CrossRef]

- K. S.; A. EA., STK11/LKB1 Deficiency Promotes Neutrophil Recruitment and Proinflammatory Cytokine Production to Suppress T-cell Activity in the Lung Tumor Microenvironment. Cancer Res. 2016, 76(5):999-1008. [CrossRef]

- D. S.; S. J., Mutation incidence and coincidence in non small-cell lung cancer: meta-analyses by ethnicity and histology (mutMap). Ann Oncol. 2013, 24(9):2371-6. [CrossRef]

- M. M.; I. A., or chemotherapy for non-small-cell lung cancer with mutated EGFR. N Engl J Med. 2010, 362(25):2380-8. [CrossRef]

- Z. E.; B. J., Receptor tyrosine kinase signalling as a target for cancer intervention strategies. Endocr Relat Cancer. 2001, 8(3):161-73. [CrossRef]

- M. U.; M. R., Targeted therapy in advanced non-small cell lung cancer: current advances and future trends. J Hematol Oncol. 2021, 14(1):108. [CrossRef]

- P. C.; F. M., Tyrosine Kinase Inhibitors in Cancer: Breakthrough and Challenges of Targeted Therapy. Cancers (Basel). 2020, 12(3):731. [CrossRef]

- H. RS.; F. M., Gefitinib--a novel targeted approach to treating cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2004, 4(12):956-65. [CrossRef]

- D. J.; M. JD., Erlotinib hydrochloride. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2005, 4(1):13-4. [CrossRef]

- J. DM.; Y. BY., 19 deletion mutations of epidermal growth factor receptor are associated with prolonged survival in non-small cell lung cancer patients treated with gefitinib or erlotinib. Clin Cancer Res. 2006, 12(13):3908-14. [CrossRef]

- H. YH.; T. JS., The impact of different first-line EGFR-TKIs on the clinical outcome of sequential osimertinib treatment in advanced NSCLC with secondary T790M. Sci Rep. 2021, 11(1):17646. [CrossRef]

- P. T.; T. J., Real world data of efficacy and safety of erlotinib as first-line TKI treatment in EGFR mutation-positive advanced non-small cell lung cancer: Results from the EGFR-2013-CPHG study. Respir Med Res. 2021, 80:100795. [CrossRef]

- S. LV.; Y. JC., Phase III study of afatinib or cisplatin plus pemetrexed in patients with metastatic lung adenocarcinoma with EGFR mutations. J Clin Oncol. 2013, 31(27):3327-34. [CrossRef]

- W. YL.; Z. C., Afatinib versus cisplatin plus gemcitabine for first-line treatment of Asian patients with advanced non-small-cell lung cancer harbouring EGFR mutations (LUX-Lung 6): an open-label, randomised phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2014, 15(2):213-22. [CrossRef]

- G. SL.; Osimertinib: First Global Approval. Drugs. 2016, 76(2):263-73. [CrossRef]

- Z. Y.; L. S., Overall survival benefit of osimertinib and clinical value of upfront cranial local therapy in untreated EGFR-mutant nonsmall cell lung cancer with brain metastasis. Int J Cancer. 2022, 150(8):1318-1328. [CrossRef]

- K. S.; H. CT., Analysis of potential predictive markers of cetuximab benefit in BMS099, a phase III study of cetuximab and first-line taxane/carboplatin in advanced non-small-cell lung cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2010, 28(6):918-27. [CrossRef]

- P. R.; P. JR., Cetuximab plus chemotherapy in patients with advanced non-small-cell lung cancer (FLEX): an open-label randomised phase III trial. Lancet. 2009, 373(9674):1525-31. [CrossRef]

- H. D. S.; B. Y. J., 1257O Durability of clinical benefit and biomarkers in patients (pts) with advanced non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) treated with AMG 510 (sotorasib). Ann Oncol. 2020, 31, S812. [CrossRef]

- H. DS.; F. MG., KRASG12C Inhibition with Sotorasib in Advanced Solid Tumors. N Engl J Med. 2020, 383(13):1207-1217. [CrossRef]

- R. M.; S. A., 1416TiP CodeBreak 200: A phase III multicenter study of sotorasib (AMG 510), a KRAS (G12C) inhibitor, versus docetaxel in patients with previously treated advanced non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) harboring KRAS p. G12C mutation. Ann Oncol. 2020, 31, S894-S895. [CrossRef]

- S. F.; L. BT., Sotorasib for Lung Cancers with KRAS p.G12C Mutation. N Engl J Med. 2021, 384(25):2371-2381. [CrossRef]

- F. JB.; F. JP., Identification of the Clinical Development Candidate MRTX849, a Covalent KRASG12C Inhibitor for the Treatment of Cancer. J Med Chem. 2020, 63(13):6679-6693. [CrossRef]

- H. J.; E. LD., The KRASG12C Inhibitor MRTX849 Provides Insight toward Therapeutic Susceptibility of KRAS-Mutant Cancers in Mouse Models and Patients. Cancer Discov. 2020, 10(1):54-71. [CrossRef]

- R. G. J.; O. S. I., 99O_PR KRYSTAL-1: Activity and preliminary pharmacodynamic (PD) analysis of adagrasib (MRTX849) in patients (Pts) with advanced non–small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) harboring KRASG12C mutation. J Thorac Oncol. 2021, 16(4), S751-S752. [CrossRef]

- F. PM.; R. CM, Crizotinib in the treatment of non-small-cell lung cancer. Expert Opin Pharmacother. 2012, 13(8):1195-201. [CrossRef]

- C. JJ.; T. M., Structure based drug design of crizotinib (PF-02341066), a potent and selective dual inhibitor of mesenchymal-epithelial transition factor (c-MET) kinase and anaplastic lymphoma kinase (ALK). J Med Chem. 2011, 54(18):6342-63. [CrossRef]

- H. Z.; X. Q, Efficacy and safety of crizotinib plus bevacizumab in ALK/ROS-1/c-MET positive non-small cell lung cancer: an open-label, single-arm, prospective observational study. Am J Transl Res. 2021, 13(3):1526-1534.

- L. C.; L. C., Genetic correlation of crizotinib efficacy and resistance in ALK- rearranged non-small-cell lung cancer. Lung Cancer. 2022, 171:18-25. [CrossRef]

- G. JF.; T. DS., Progression-Free and Overall Survival in ALK-Positive NSCLC Patients Treated with Sequential Crizotinib and Ceritinib. Clin Cancer Res. 2015, 21(12):2745-52. [CrossRef]

- T. RK.; Overcoming drug resistance in ALK-rearranged lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2014, 370(13):1250-1. [CrossRef]

- F. E.; K. D., Efficacy and safety of ceritinib in patients (pts) with advanced anaplastic lymphoma kinase (ALK)-rearranged (ALK+) non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC): an update of ASCEND-1. Annal Oncol. 2014, 25: iv456. [CrossRef]

- S. BJ.; M. T., First-line crizotinib versus chemotherapy in ALK-positive lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2015, 373(16):1582. [CrossRef]

- B. G.; T. J., Vemurafenib: the first drug approved for BRAF-mutant cancer. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2012, 11(11):873-86. [CrossRef]

- T. J.; L. JT., Discovery of a selective inhibitor of oncogenic B-Raf kinase with potent antimelanoma activity. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008, 105(8):3041-6. [CrossRef]

- H. DM.; P. I., Vemurafenib in Multiple Nonmelanoma Cancers with BRAF V600 Mutations. N Engl J Med. 2018, 379(16):1585. [CrossRef]

- S. V.; G. R., Efficacy of Vemurafenib in Patients With Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer With BRAF V600 Mutation: An Open-Label, Single-Arm Cohort of the Histology-Independent VE-BASKET Study. JCO Precis Oncol. 2019, 3:PO.18.00266. [CrossRef]

- K. AJ.; A. MR., Dabrafenib; preclinical characterization, increased efficacy when combined with trametinib, while BRAF/MEK tool combination reduced skin lesions. PLoS One. 2013, 8(7):e67583. [CrossRef]

- Z. R.; Trametinib. Recent Results Cancer Res. 2014, 201:241-8. [CrossRef]

- P. D.; K. TM., Dabrafenib in patients with BRAF(V600E)-positive advanced non-small-cell lung cancer: a single-arm, multicentre, open-label, phase 2 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2016, 17(5):642-50. [CrossRef]

- P. D.; S. EF., Dabrafenib plus trametinib in patients with previously untreated BRAFV600E-mutant metastatic non-small-cell lung cancer: an open-label, phase 2 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2017, 18(10):1307-1316. [CrossRef]

- B. MI.; N. J., FDA Approval Summary: Dabrafenib in Combination with Trametinib for BRAFV600E Mutation-Positive Low-Grade Glioma. Clin Cancer Res. 2024, 30(2):263-268. [CrossRef]

- S. AT.; O. SH., Crizotinib in ROS1-rearranged non-small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2014, 371(21):1963-71. [CrossRef]

- V. HG.; N. TQ., Crizotinib in the Treatment of Advanced Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer with ROS1 Rearrangement or MET Alteration: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Target Oncol. 2020, 15(5):589-598. [CrossRef]

- G. JF.; T. D., Patterns of Metastatic Spread and Mechanisms of Resistance to Crizotinib in ROS1-Positive Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer. JCO Precis Oncol. 2017, 2017:PO.17.00063. [CrossRef]

- A. MM.; K. R., Acquired resistance to crizotinib from a mutation in CD74-ROS1. N Engl J Med. 2013, 368(25):2395-401. [CrossRef]

- M. M,; A. E., Discovery of Entrectinib: A New 3-Aminoindazole As a Potent Anaplastic Lymphoma Kinase (ALK), c-ros Oncogene 1 Kinase (ROS1), and Pan-Tropomyosin Receptor Kinases (Pan-TRKs) inhibitor. J Med Chem. 2016, 59(7):3392-408. [CrossRef]

- D. A.; S. S., Entrectinib in ROS1 fusion-positive non-small-cell lung cancer: integrated analysis of three phase 1-2 trials. Lancet Oncol. 2020, 21(2):261-270. [CrossRef]

- A. E.; M. M., Entrectinib, a Pan-TRK, ROS1, and ALK Inhibitor with Activity in Multiple Molecularly Defined Cancer Indications. Mol Cancer Ther. 2016, 15(4):628-39. [CrossRef]

- Z. HY.; L. Q., PF-06463922 is a potent and selective next-generation ROS1/ALK inhibitor capable of blocking crizotinib-resistant ROS1 mutations. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2015, 112(11):3493-8. [CrossRef]

- F. E.; B. T., MA07. 11 safety and efficacy of lorlatinib (PF-06463922) in patients with advanced ALK+ or ROS1+ non-small-cell lung cancer (NSCLC). J Thorac Oncol. 2017, 12.1: S383-S384. [CrossRef]

- S.AT.; S. BJ., Lorlatinib in advanced ROS1-positive non-small-cell lung cancer: a multicentre, open-label, single-arm, phase 1-2 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2019, 20(12):1691-1701. [CrossRef]

- S.R.; Cho BC, Brahmer JR, Soo RA. Nivolumab in NSCLC: latest evidence and clinical potential. Ther Adv Med Oncol. 2015, (2):85-96. [CrossRef]

- R. D., Pembrolizumab versus Chemotherapy for PD-L1-Positive Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer. N Engl J Med. 2016, 375(19):1823-1833. [CrossRef]

- S. A.; K.S., Cemiplimab monotherapy for first-line treatment of advanced non-small-cell lung cancer with PD-L1 of at least 50%: a multicentre, open-label, global, phase 3, randomised, controlled trial. Lancet. 2021, 397(10274):592-604. [CrossRef]

- L.ES.; S.A., Analysis of Tumor Mutational Burden, Progression-Free Survival, and Local-Regional Control in Patents with Locally Advanced Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer Treated With Chemoradiation and Durvalumab. JAMA Netw Open. 2023, 6(1):e2249591. [CrossRef]

- B. JR.; L. JS., Five-Year Survival Outcomes With Nivolumab Plus Ipilimumab Versus Chemotherapy as First-Line Treatment for Metastatic Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer in CheckMate 227. J Clin Oncol. 2023, 41(6):1200-1212. [CrossRef]

- W.Y.; H. H., Immune checkpoint inhibitors alone vs immune checkpoint inhibitors-combined chemotherapy for NSCLC patients with high PD-L1 expression: a network meta-analysis. Br J Cancer. 2022, 127(5):948-956. [CrossRef]

- S.Y.; K. F., Immune Checkpoint Inhibitors in Cancer Therapy. Curr Oncol. 2022, 29(5):3044-3060. [CrossRef]

- M. F.; S. L., Adverse effects of immune-checkpoint inhibitors: epidemiology, management and surveillance. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2019, 16(9):563-580. [CrossRef]

- D. AA.; P. VG., The role of PD-L1 expression as a predictive biomarker: an analysis of all US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approvals of immune checkpoint inhibitors. J Immunother Cancer. 2019, 7(1):278. [CrossRef]

- R. B.; W. X., Association of High Tumor Mutation Burden in Non-Small Cell Lung Cancers With Increased Immune Infiltration and Improved Clinical Outcomes of PD-L1 Blockade Across PD-L1 Expression Levels. JAMA. Oncol. 2022, 8(11):1702. [CrossRef]

- M. A.; L. DT, Efficacy of Pembrolizumab in Patients With Noncolorectal High Microsatellite Instability/Mismatch Repair-Deficient Cancer: Results From the Phase II KEYNOTE-158 Study. J Clin Oncol. 2020, 38(1):1-10. [CrossRef]

- G. A.; M. DF., Nivolumab for the treatment of cancer. Expert Opin Investig Drugs. 2015, 24(2):253-60. [CrossRef]

- R. M.; R. D., Pembrolizumab Versus Platinum-Based Chemotherapy for Advanced Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer With PD-L1 Tumor Proportion Score of 50% or Greater. J Clin Oncol. 2019, 37(7):537-546. [CrossRef]

- A. M.; R. S., Al-Bozom IA. PD-L1 immunostaining: what pathologists need to know. Diagn Pathol. 2022, 17(1):50. [CrossRef]

- E. Z.; C. LE., Circulating tumour cells and PD-L1-positive small extracellular vesicles: the liquid biopsy combination for prognostic information in patients with metastatic non-small cell lung cancer. Br J Cancer. 2024 Jan;130(1):63-72. [CrossRef]

- A. TA.; The Role of Circulating Tumor Cells as a Liquid Biopsy for Cancer: Advances, Biology, Technical Challenges, and Clinical Relevance. Cancers (Basel). 2024, 16(7):1377. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- S. J.; M. J., Radiogenomic System for Non-Invasive Identification of Multiple Actionable Mutations and PD-L1 Expression in Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer Based on CT Images. Cancers (Basel). 2022, 14(19):4823. [CrossRef]

- W.C.; M. J., Non-Invasive Measurement Using Deep Learning Algorithm Based on Multi-Source Features Fusion to Predict PD-L1 Expression and Survival in NSCLC. Front Immunol. 2022, 13:828560. [CrossRef]

- K. A.; D. M., The role of genetic polymorphism within PD-L1 gene in cancer. Review. Exp Mol Pathol. 2020, 116:104494. [CrossRef]

- Y.M.; H.A., Tumor Mutational Burden and Response Rate to PD-1 Inhibition. N Engl J Med. 2017, 377(25):2500-2501. [CrossRef]

- M. L.; F. LA., FDA Approval Summary: Pembrolizumab for the Treatment of Tumor Mutational Burden-High Solid Tumors. Clin Cancer Res. 2021, 27(17):4685-4689. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- R. N. F.; J. G., 1028P BIOLUMA: A phase II trial of nivolumab in combination with ipilimumab to evaluate efficacy and safety in lung cancer and to evaluate biomarkers predictive for response – results from the NSCLC cohort. Annal Oncol. 2022, 33:S1025. [CrossRef]

- F. F.; P. R., Measuring tumor mutation burden in non-small cell lung cancer: tissue versus liquid biopsy. Transl Lung Cancer Res. 2018, 7(6):668-677. [CrossRef]

- W. D.; G. S., The prognostic value of TMB in early-stage non-small cell lung cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ther Adv Med Oncol. 2023, 15:17588359231195199. [CrossRef]

- F. L.; G. S., Tumor mutational burden quantification from targeted gene panels: major advancements and challenges. J Immunother Cancer. 2019, 7(1):183. [CrossRef]

- B. R.; L. JW., Implementing TMB measurement in clinical practice: considerations on assay requirements. ESMO Open. 2019, 4(1):e000442. [CrossRef]

- P. GF.; A. S., TMBcalc: a computational pipeline for identifying pan-cancer Tumor Mutational Burden gene signatures. Front Genet. 2024, 15:1285305. [CrossRef]

- F. L.; G. S., Tumor mutational burden quantification from targeted gene panels: major advancements and challenges. J Immunother Cancer. 2019, 7(1):183. [CrossRef]

- J. T.; B. CR., Structure and function of the components of the human DNA mismatch repair system. Int J Cancer. 2006, 119(9):2030-5. [CrossRef]

- L. DT.; U. JN., PD-1 Blockade in Tumors with Mismatch-Repair Deficiency. N Engl J Med. 2015, 372(26):2509-20. [CrossRef]

- B. M.;, L. DT., DNA mismatch repair in cancer. Pharmacol Ther. 2018, 189:45-62. [CrossRef]

- A. V.; M. G., Mechanisms of Immune Escape and Resistance to Checkpoint Inhibitor Therapies in Mismatch Repair Deficient Metastatic Colorectal Cancers. Cancers (Basel). 2021, 13(11):2638. [CrossRef]

- B. M.; L. DT., DNA mismatch repair in cancer. Pharmacol Ther. 2018, 189:45-62. [CrossRef]

- A. V.; M. G., Mechanisms of Immune Escape and Resistance to Checkpoint Inhibitor Therapies in Mismatch Repair Deficient Metastatic Colorectal Cancers. Cancers (Basel). 2021, 13(11):2638. [CrossRef]

- D. F.; C. KB., Comparison of microsatellite instability detection by immunohistochemistry and molecular techniques in colorectal and endometrial cancer. Sci Rep. 2021, 11(1):12880. [CrossRef]

- E. A.; L. G. N., Deep learning for the detection of microsatellite instability from histology images in colorectal cancer: a systematic literature review. ImmunoInformatics. 2021, 3-4:100008.

- A.V.; H. C., ctDNA response after pembrolizumab in non-small cell lung cancer: phase 2 adaptive trial results. Nat Med. 2023, 29(10):2559-2569. [CrossRef]

- P. F.; A.P., "Circulating tumor DNA (ctDNA) as predictive biomarker in NSCLC patients treated with nivolumab." Annal Oncol. 2017, 28:( ii10-ii11). [CrossRef]

- M. EJ.; L. Y., Circulating Tumor DNA Dynamics Predict Benefit from Consolidation Immunotherapy in Locally Advanced Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer. Nat Cancer. 2020, 1(2):176-183. [CrossRef]

- S. JC.; B. Y., Current and Future Clinical Applications of ctDNA in Immuno-Oncology. Cancer Res. 2022, 82(3):349-358. [CrossRef]

- K. H.; P. KU., Clinical Circulating Tumor DNA Testing for Precision Oncology. Cancer Res Treat. 2023, 55(2):351-366. [CrossRef]

- C. SA.; Liu MC, Aleshin A. Practical recommendations for using ctDNA in clinical decision making. Nature. 2023, 619(7969):259-268. [CrossRef]

- K. D.; T. A., Response to Checkpoint Inhibition in Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer with Molecular Driver Alterations. Oncol Res Treat. 2020, 43(6):289-298. [CrossRef]

- B. D., D. A. Immunotherapy in EGFR mutant non-small cell lung cancer: when, who and how? Transl Lung Cancer Res. 2019, 5):710-714. [CrossRef]

- L. C.; Z. S., The superior efficacy of anti-PD-1/PD-L1 immunotherapy in KRAS-mutant non-small cell lung cancer that correlates with an inflammatory phenotype and increased immunogenicity. Cancer Lett. 2020, ;470:95-105. [CrossRef]

- V. NI.; P. K, Le X. Efficacy of immunotherapy in oncogene-driven non-small-cell lung cancer. Ther Adv Med Oncol. 2023, 15:17588359231161409. [CrossRef]

- T. S.; Q. C., Immune Checkpoint Inhibitors in Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer: Progress, Challenges, and Prospects. Cells. 2022, 11(3):320. [CrossRef]

- M. PC.; K. MI., Targeted Next-Generation Sequencing Reveals Exceptionally High Rates of Molecular Driver Mutations in Never-Smokers With Lung Adenocarcinoma. Oncologist. 2022, 27(6):476-486. [CrossRef]

- C. A.; R. JW., Brahmer JR. Checkpoint Blockade in Lung Cancer With Driver Mutation: Choose the Road Wisely. Am Soc Clin Oncol Educ Book. 2020, 40:372-384. [CrossRef]

- N. T.; O. H., Clinical Impact of Single Nucleotide Polymorphism in PD-L1 on Response to Nivolumab for Advanced Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer Patients. Sci Rep. 2017, 7:45124. [CrossRef]

- B.E. A.; S. B., Association of single nucleotide polymorphisms with efficacy in nivolumab-treated NSCLC patients. Annal Oncol. 2017, 28: v473. [CrossRef]

- P.G.; L. L., rs822336 binding to C/EBPβ and NFIC modulates induction of PD-L1 expression and predicts anti-PD-1/PD-L1 therapy in advanced NSCLC. Mol Cancer. 2024, 23(1):63. [CrossRef]

- H. L. M.; M. A,, KIR-HLA gene diversities and susceptibility to lung cancer. Sci Rep. 2022, 12(1):17237. [CrossRef]

- M. J.; J. G., HLA class II molecule HLA-DRA identifies immuno-hot tumors and predicts the therapeutic response to anti-PD-1 immunotherapy in NSCLC. BMC Cancer. 2022, 22(1):738. [CrossRef]

- H. S.; S. R., Assessing the Host Immune Response, TILs in Invasive Breast Carcinoma and Ductal Carcinoma In Situ, Metastatic Tumor Deposits and Areas for Further Research. Adv Anat Pathol. 2017, (5):235-251. [CrossRef]

- K. D.; K. K.,Systemic inflammation and pro-inflammatory cytokine profile predict response to checkpoint inhibitor treatment in NSCLC: a prospective study. Sci Rep. 2021, 11(1):10919. [CrossRef]

- D.S.; H. T., The Gut Microbiome from a Biomarker to a Novel Therapeutic Strategy for Immunotherapy Response in Patients with Lung Cancer. Curr Oncol. 2023, 30(11):9406-9427. [CrossRef]

- S.D.; Revolutionizing Lung Cancer Treatment: Innovative CRISPR-Cas9 Delivery Strategies. AAPS PharmSciTech. 2024, 25(5):129. [CrossRef]

| Gene | Molecular alteration |

Locus | Mutational Hotspot | Drug |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| EGFR | Mutation | 7p11.2 | Deletion in exon 19 Substitution in exon 21 (L858R) |

Gefitinib Erlotinib Afatinib Osimertinib |

| KRAS | Mutation | 12p12.1 | Substitution in exon 12 (G12C), Substitution in exon 13 (G12D) Substitution in exon 61 (G12V) |

Sotorasib Adagrasib |

| ALK | Variable chromosome rearrangement | 2p23.2-p23.1 | Fusion EML4-ALK, KIF5B-ALK, TFG-ALK, KLC1-ALK | Crizotinib Ceritinib Alectinib Brigatinib Lorlatinib |

| BRAF | Mutation | 7q34 | Sostitution V600E, V600D, V600K, V600R K601N/E, L597V, G464V, G469V/R/A, G466V/A,N581S , D594N/G, G596R |

Vemurafenib Dabrafenib Trametinib |

| ROS1 | Variable chromosome rearrangement |

6q22.1 | Fusion CD74-ROS1, SLC34A2-ROS1, TPM3-ROS1, SDC4-ROS1 | Vemurafenib Dabrafenib Trametinib |

| Gene | Molecular alteration |

Locus | Mutational Hotspot | Drug |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PD-L1 | Mutation Amplification |

9p24.1 | Substitution G1268C | Nivolumab Pembrolizumab Cemiplimab Durvalumab Atezolizumab Avelumab |

| MET | Amplification Mutation Chromosome rearrangement |

7q31.2 | METex14 Fusion KIF5B-MET |

Crizotinib Tepotinib Capmatinib Bozitnib Glumetinib |

| RET | Variabel chromosome rearrangement Mutation |

10q11.21 | Fusion KIF5B-RET, CCDC6-RET, NCOA4-RET, TRIM33-RET, CUX1-RET | Pralsetinib Selpercatinib |

| NTRK | Gene fusions | 13q31.1 13q31.2 Xq27.3 3q26.1 |

Fusion SQSTM1-NTRK1, RFWD2-NTRK1, CD74-NTRK1, TRIM 24 – NTRK2 | Entrectinib Larotrectinib Repotrectinib |

| PIK3CA | Mutation Amplification |

3q26.32 | Substitution in exon 9 (E545K/E542K) Substitution in exon 20 (H1047R/H1047L) |

Gedatolisib Idelalisib |

| HER2 | Mutation Amplification Overexpression |

17q12 | Insertion in exon 20 (A775_G776insYVMA) | Ado-trastuzumab emtansine Mobocertinib Poziotinib |

| STK11 | Mutation Inactivation |

19p13.3 | Deletion of 19p13.3 | Atezolizumab Pembrolizumab Nivolumab |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).