1. Introduction

UO

2 and uranium-plutonium mixed oxides (U, Pu)O

2 are essential part in the nuclear fuel cycle for current nuclear industry. Actinides such as plutonium (Pu) and minor americium (Am) and neptunium (Np) are produced during UO

2 fission. The presence of these actinides has a significant impact on the structure and behavior of nuclear fuels, as well as on the cycle for nuclear fuels and reprocessing of nuclear wastes. In fast neutron reactors, such as sodium-cooled fast reactors (SFRs), that is to improve the recycling of Pu and the efficiency of UO

2 in the nuclear fuel cycle. In the meanwhile, uranium-americium mixed oxides (U, Am)O

2 are ideal nuclear fuel for the design of Generation IV fast neutron reactors [

1,

2]. Furthermore, under the storage conditions of PuO

2, owing to

241Pu decaying into

241Am and the short half-life of

241Pu, PuO

2 contains significant ingrowth of Am. Thus, it is crucial to focus on how the presence of minor actinides especially americium in nuclear fuels will degrade the structure and properties of nuclear fuels for fast reactors.

In the ideal (U, Am)O

2 mixed oxides, the random substitution of Am

4+ for U

4+ in the UO

2 lattice greatly affects the behavior of nuclear fuels. However, at the atomic scale of the mixed oxides systems, there are inevitably regions enriched in Am owing to the short decay period of Pu in nuclear wastes and current industrial procedures. In the nuclear fuel matrix of the mixed oxides (U, Am)O

2, Am is enriched in the crystal matrix of UO

2, and the influence on the structure and properties of nuclear materials cannot be ignored [

3]. Our study focuses on the bulk properties include structural, energetic, and mechanical properties of the mixed oxides (U, Am)O

2, especially for various Am aggregation contents in UO

2 nuclear fuel, in order to the understanding and prediction of the behavior of the fuel in the reactor.

Actinides such as U, Pu and Am have abundant oxidation states and many interesting physical and chemical features owing to the presence of strongly correlated 5

f orbital electrons. At present, there have been limited experimental and theoretical data on the ground state structure and properties of PuO

2 and AmO

2, including magnetic orders, electronic and mechanical properties. Noutack et al. [

6] used GGA+

U combined with the special quasirandom structures (SQS) method to study the structural and electronic properties of U

1−yAm

yO

2 under different Am contents, and obtained results consistent with the limited experimental measurements. Dorado et al. [

4] and Njifon et al. [

5] used DFT+

U method calculated the mixed oxides (U, Pu)O

2 in the difference Pu content range, and reproduced lattice shrinkage with Pu content of increased, and the obtained enthalpy of formation of UO

2 and PuO

2 was consistent with experimental values, especially the mixing enthalpy of the uranium-plutonium mixed oxides (U, Pu)O

2 was calculated to analyze the stability of the mixed oxides systems. Although the SQS method has some advantages in constructing disordered solid solution structures, the modeling at the atomic scale and the specific impact on structure and properties for uranium-americium mixed oxides are unclear as the Am aggregation content increases in UO

2 matrix. In particular, our calculations show that the volume and enthalpy of mixed oxides (U, Am)O

2 are significantly different from those of the SQS method as Am aggregation contents increases.

In the present work, the effects of different Am aggregation contents on the structure and properties of mixed oxides (U, Am)O2 are calculated using the PBEsol+U method based on first principles, mainly including architecture, energy and mechanical properties. Furthermore, as a reference, the bulk properties of the (U, Pu)O2 mixed oxides with different Pu aggregation contents are also reported in this work.

2. Methodology

In this work, all PBEsol+

U calculations were performed using the Vienna Ab initio Simulation Package (VASP) based on density functional theory (DFT) [

7,

8,

9,

10,

11]. Our previous works [

12,

13] and James et al.’s calculations [

14] show that the prediction of the structure, energy and electronic properties of actinide oxide compounds using the PBEsol+

U is better than that of other functional. The PBEsol+

U method considers the on-site coulomb interaction

U and exchange

J for the 5

f electrons of actinides U, Pu and Am [

15,

16,

17]. In this calculations,

UU = 4.5 eV and

JU = 0.51 eV [

18,

19],

UPu = 4.0 eV, and

JPu = 0.00 eV [

4,

20], as well as

UAm = 6.0 eV and

JAm = 0.75 eV were used [

21]. Moreover, the spin-orbit coupling (SOC) effect is neglected because of the efficiency of the calculations considered in our calculations. And the calculations in literatures show that SOC has no important effect on the structure and energy of formation of UO

2 and PuO

2 [

22,

23,

24,

25,

26,

27].

Although experiments show that UO

2 is 3

k-antiferromagnetic (AFM) order, DFT+

U calculations obtain a good description with 1

k-AFM order when SOC is not considered [

4,

27,

28,

29,

30]. There is no uniform conclusion on the magnetic order for PuO

2, but usually DFT+

U calculations using a 1

k-AFM order give reliable ground state results. Thus, our calculations consider the 1

k-ferromagnetic (FM) order and 1

k-antiferromagnetic (AFM) order of UO

2, PuO

2, AmO

2 and the mixed oxides (U, Am)O

2 and (U, Pu)O

2 so that stable ground state structures and properties can be obtained when building these mixed oxides structures.

The energy of formation (

Ef) is calculated from the results of the DFT+

U calculations as follows:

Whereis the PBEsol+U total energy of the UO2, PuO2 and AmO2 compounds, are the PBEsol+U chemical potential of oxygen in the molecular oxygen reference state, andis the PBEsol+U chemical potential of metallic α-U, α-Pu and α-Am reference state.

In order to obtain the reliable defect structures at the atomic scale, we have used two different supercell models, one in a 96-atom UO

2 structure that replaces U with Am (Pu), and the other in a 12-atom system. In the (U, Am)O

2 defect model for various Am aggregation contents,energetics of defects in these structures are described by energy of formation. Energy of formation of a replacement is expressed as

Whereis the PBEsol+U total energy of the lattice UO2 with Am replacement, is the calculated total energy of the perfect lattice, is the calculated chemical potential of metallic α-U reference state, and is the calculated chemical potential of metallic α-Am replacement elements.

The mixing enthalpy of the (U, Am)O

2 solid solution is determined using the calculations of the total energy in the entire Am contents of the PBEsol+

U method. The equation is expressed as

Where , , and are the calculated total energies for these oxides.

Our calculations were performed using a 2 × 2 × 2

k-point mesh in Brillouin zones for supercells (96-atom). The calculation of elastic constants for a range Am or Pu contents (25%, 50%, and 75%) were performed use of 12-atom supercells with a 6 × 6 × 6

k-point mesh. The energy cutoff of 550 eV was used for all calculations. By performing structural relaxation until the Hellmann-Feynman force of each atom is less than 0.01 eV/Å and the convergence on energy less than 10

−5 eV/atom, the stable ground state structure of the system is obtained. Moreover, the variation of the volume and

Etot of mixed oxides (U, Pu)O

2 with different Pu aggregation contents are shown in Fig. 1S and 2S. The structure and properties including the lattice parameter and band gap of the (U, Pu)O

2 defect model for various Pu aggregation contents using PBEsol+

U are shown in

Table 1S and 2S. Energy of formation of UO

2, PuO

2 and (U, Pu)O

2 using PBEsol+

U are shown in

Table 3S. The obtained elastic constants and bulk modulus of (U, Pu)O

2 are shown in

Table 4S.

3. Results and discussion

3.1. The bulk properties for (U, Am)O2 using the supercell (96-atom) defect models

The magnetic stability in the mixed oxide (U, Am)O

2 for various Am aggregation contents for the two different magnetic configurations: the 1

k-FM and 1

k-AFM orders have been considered. The obtained lattice parameter and band gap of the (U, Am)O

2 using PBEsol+

U method were shown in

Table 1. As shown in

Table 1, the energy differences obtained between the two magnetic orders are less. There is also no difference on the lattice parameters for the two magnetic orders, but almost 9% difference in the bandgap. In order to have a consistent comparison of the ground state properties for various americium aggregation concentration contents, the AFM order of the uranium-americium mixed oxides for all compositions was adopted.

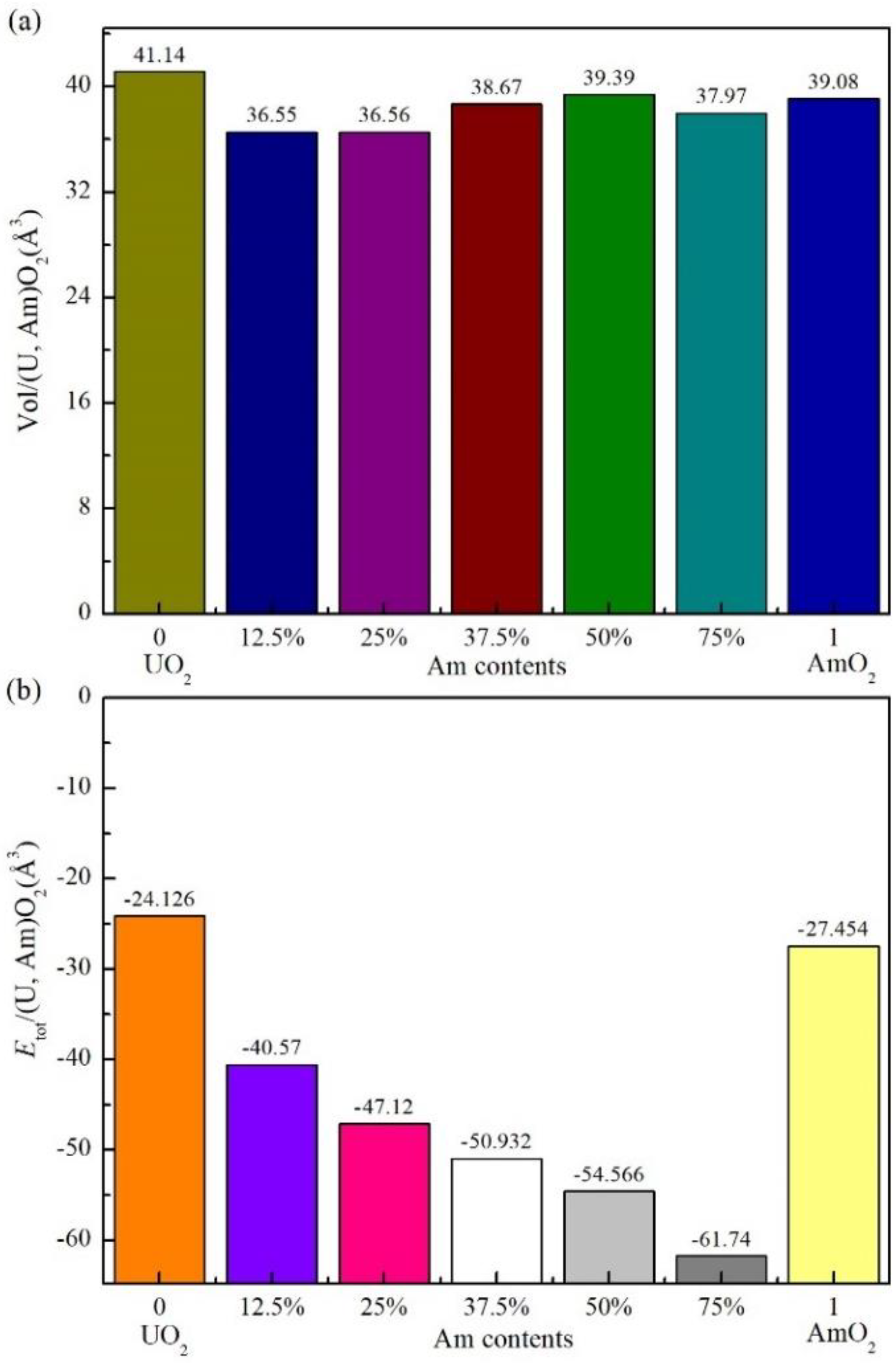

Indeed, our calculations show that there are two distinct ranges of variation in the volume of the (U, Am)O

2 mixed oxides as the amount of Am increases in UO

2. Firstly, when the Am content in UO

2 increases from 0 to 12.5%, the lattice parameter of the (U, Am)O

2 decreases from 5.48Å to 5.221Å, while the lattice parameter of the systems increases from 5.221 Å to 5.407 Å when the Am content increases from 12.5% to 50% (

Table 1 and

Figure 1). The trends of this change is significantly different with experimental observations and predictions of uranium-americium mixed oxides (U, Am)O

2 by Noutack et al. using the SQS [

6]. This difference may be mainly because the fact that the ionic radius of Am

4+ is slightly smaller than that of U

4+ ions in the cubic fluorite structure, which can also be further explained by the fact that the lattice size of AmO

2 is smaller than that of UO

2. The effects of different Am aggregation contents on the structure and properties of UO

2 will be of great significance for improving the efficiency of the mixed oxides nuclear fuel recycling and the safe storage of nuclear waste.

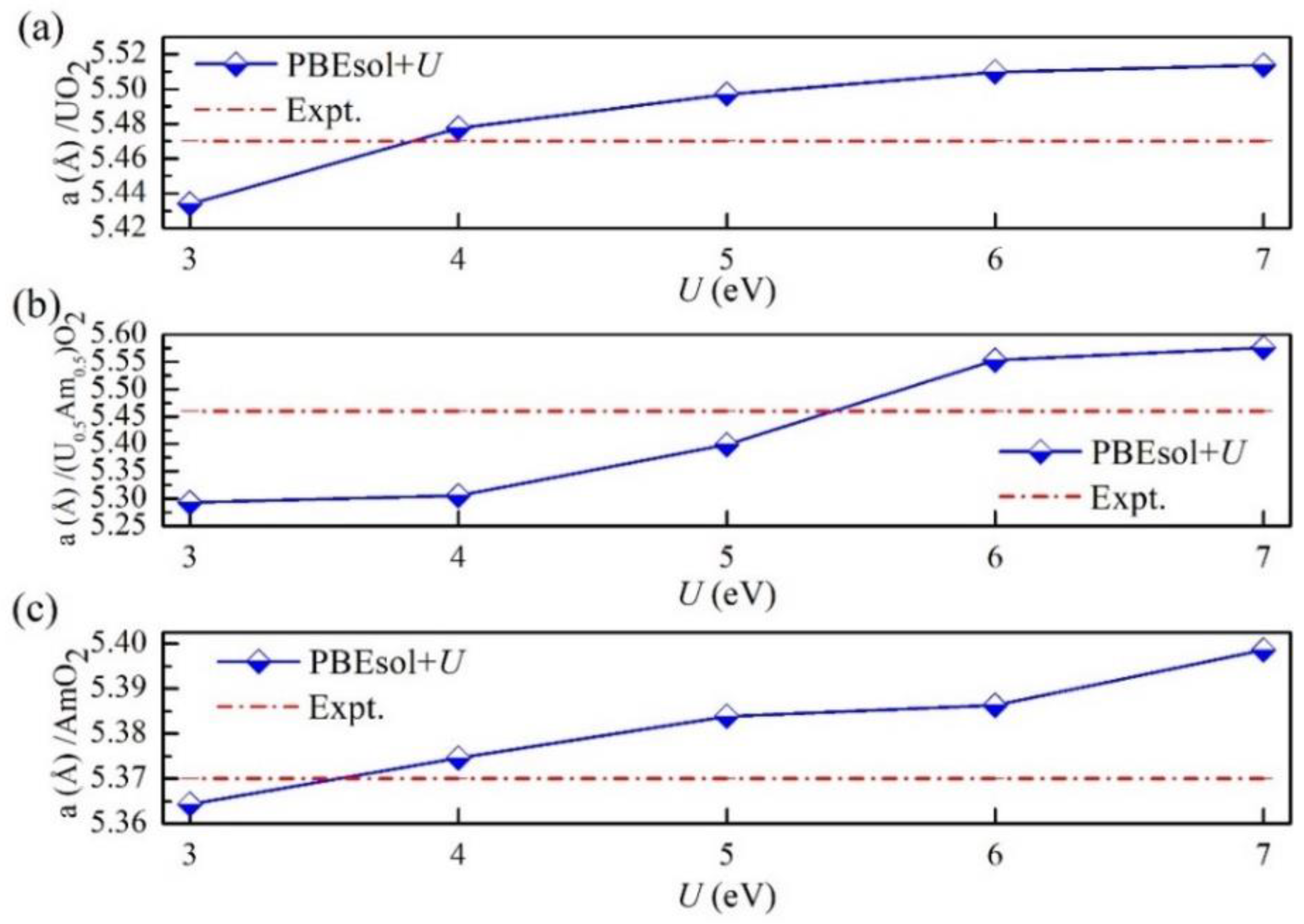

For the (U, Am)O

2 mixed oxides systems, the effect of the variation of the Hubbard parameter

U of Am

4+ cation on the structure and properties of (U, Am)O

2 is critical. In this work, the effect of the variations of the onsite Coulomb interaction parameter

U on the lattice parameter of UO

2, (U

0.5Am

0.5)O

2, and AmO

2. The values of the

J parameters are kept constant. Our results are shown in

Figure 2 and compared with experimental values. For

U= 4.0 eV, an overestimation of 1% is observed in the lattice parameter of UO

2 compared to the experimental value. Further, when

U increases from 4.0 to 7.0 eV, the lattice constant increases by 0.7%. For

U = 4.0 eV, an overestimation of 1.5% is observed in the lattice parameter of AmO

2 compared to the experimental value. Further, when

U increases from 4.0 to 6.0 eV, the lattice constant increases by 0.6%. For (U

0.5Am

0.5)O

2, when

U= 6.0 eV, the overestimations compared to the experimental values are 0.5%. Thus, a small variation of

U parameter of U and Am in (U, Am)O

2 has a negligible impact on its structural properties.

3.2. The structure and properties of (U, Am)O2 using supercell (12-atom) method

The lattice parameters, energy of formation and bandgap values and magnetic moments of the different Am contents in UO

2 including 25%, 50% and 75% as well as AmO

2 were calculated by the PBEsol+

U method, and the results are shown in

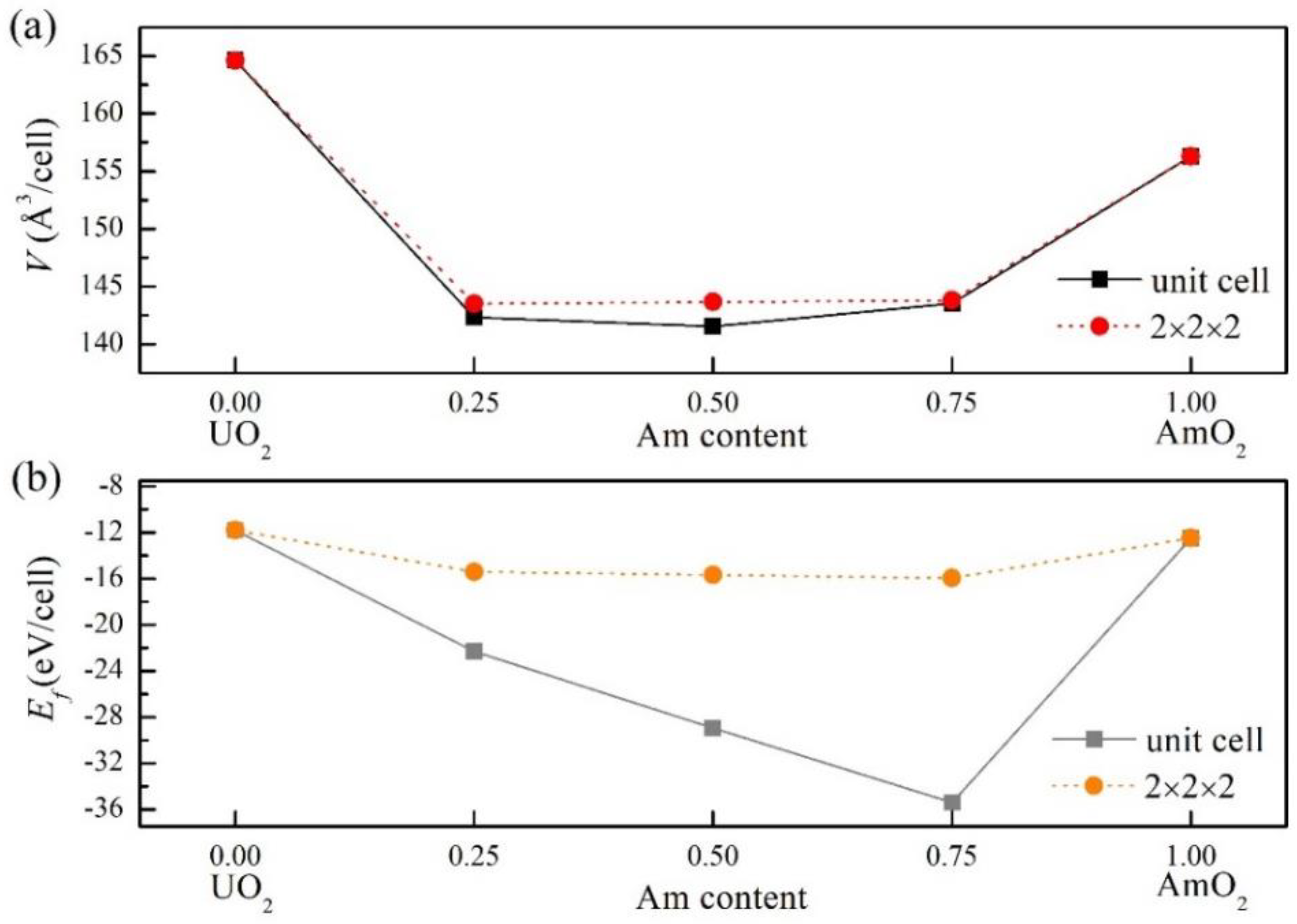

Table 2. And the volume of the mixed oxides (U, Am)O

2 of different supercells as a function of Am content is shown in

Figure 3(b). The results show that the lattice parameters of (U, Am)O

2 are reduced when Am is added to UO

2 matrix, and the supercells of different sizes had no significant effect on the volume of (U, Am)O

2. However, compared with the calculated results of (U, Pu)O

2 (Table S2), the volume of (U, Am)O

2 showed a different trend with Am content than that of Pu. As shown in Table S2, in the (U, Pu)O

2 structure, the volume of the system decreases with the increase of Pu content, while in the (U, Am)O

2 structure, the volume of the system decreases with the increase of Am, and the volume decreases to the lowest when the Am content is 50%. Subsequently, there was a slight increase with the increase of Am content. This trend is important for the understanding and application of the structure and properties of the two mixed oxides.

In order to obtain a reliable and consistent ground state structure of the magnetic orders of the mixed oxides, we investigated the lattice parameter and band gap (U, Am)O

2 defect model for various Am concentration contents in UO

2 matrix, respectively. As shown in

Table 2, the volume of the (U, Am)O

2 mixed oxides increase significantly as the increases of Am in UO

2. This change characteristics and trends are markedly different from those of Pu in UO

2. In the (U, Am)O

2 mixed oxides, although the volume of the system is the lowest when the Am content reaches 12.5%, the volume of the mixed oxide increases significantly with the increasing Am content. This difference may be mainly because the fact that the ionic radius of Pu

4+ is slightly smaller than that of U

4+ ions in the cubic fluorite structure, which can also be further explained by the fact that the lattice size of PuO

2 is smaller than that of UO

2.

In the electronic structure calculations (

Table 1 and

Table 2), the results show that the UO

2 band gap value at 1

k-antiferromagnetic is 2.0 eV, which is significantly closer to the experimental value than other results. Moreover, the calculated results of the band gap of AmO

2 are in good agreement with the experimental values. As

Table 1 and

Table 2 shown, the band gap of the mixed oxides (U, Am)O

2 is significantly reduced to 0.8 eV. And with the increase of Am content, the band gap of (U, Am)O

2 almost did not change. Compared with the band gap results of (U, Pu)O

2 (Table S1 and S2), the characteristics of the reduced bandgap of (U, Am)O

2 are consistent. A careful comparison of the electronic structure changes of the two mixed oxides shows that the reduction of the band gap in the mixed oxides structure is mainly determined by the size of the band gap between UO

2 and AmO

2 such as the strong coulomb interaction of the 5

f orbital electrons.

In

Table 2, the spin magnetic moments of UO

2 calculated by the PBEsol+

U method are 2.0

μB, which are very close to the experimental observations. Although there is no experimental result for the spin magnetic moment of AmO

2, the result of our calculation is 5.3

μB, which is consistent with the calculated results of the hybrid density functional (HSE). In the calculated results of the mixed oxides (U, Am)O

2, the spin magnetic moment is 7.1

μB, which is significantly higher than that of UO

2 and AmO

2. Therefore, the magnetic moment of UO

2 and AmO

2 calculated by using 1

k-antiferromagnetism is also closer to the experimental values, which also provides a reference for the prediction of magnetic moment for the mixed oxides (U, Am)O

2.

3.3. Energetic properties for (U, Am)O2 using PBEsol+U

The results of the energy of formation of UO

2,AmO

2 and the mixed oxides (U, Am)O

2 with different Am aggregation contents obtained using PBEsol+

U method are listed in

Table 3.

Figure 3(b) shows the relationship between the energy of formation of different supercell sizes and the Am aggregation content of (U, Am)O

2. According to the results of the energy of formation of these systems, the mixed oxides (U, Am)O

2 formed by the incorporation of different Am contents reduces the energy of formation is also low, but compared with the different Pu aggregation content in the mixed oxides (U, Pu)O

2 structure (Table S3), the effect of different Am aggregation contents on the energy of formation of (U, Am)O

2 is not the same. The energy of formation of (U, Am)O

2 is reduced with the increase of Am content.

In the defect model, with the accumulation of Am in UO2, the energy of formation of the mixed oxide system is significantly lower than that of Njifon et al. by the SQS method. In the mixed oxides (U, Pu)O2, when the Pu content is 25%, the energy of formation of (U, Pu)O2 is the lowest. However, in the mixed oxides (U, Am)O2, the energy of formation of (U, Am)O2 can continue to decrease with the increase of Am content. Although the results of different supercell sizes in calculating the energy of formation of the two mixed oxides are different, the calculated results of 2×2×2 supercells are reliable.

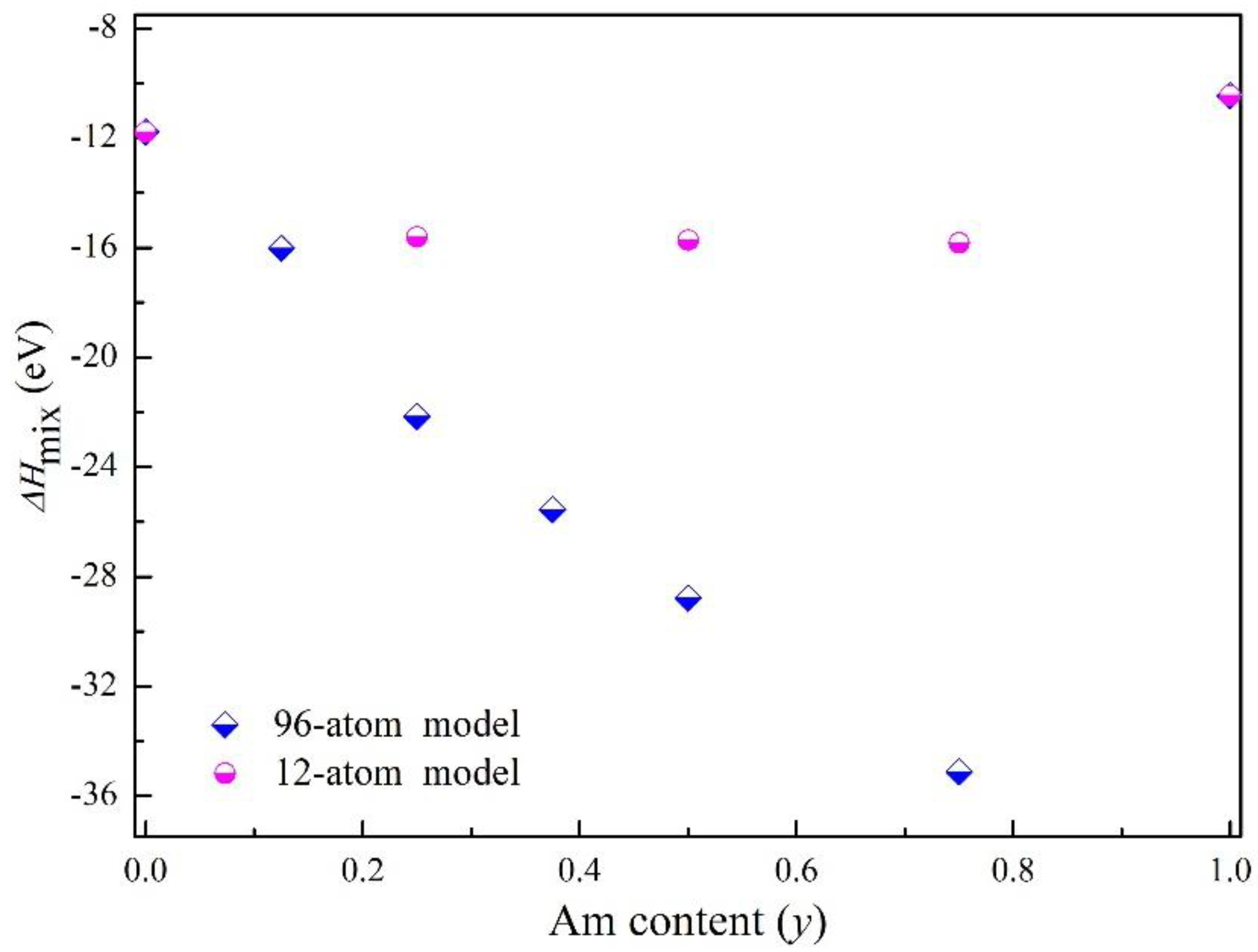

The obtained mixing enthalpy of mixed oxides (U, Am)O

2 in the entire range of Am contents using the PBEsol+

U method were shown in

Figure 5. The mixing enthalpy of (U, Am)O

2 is found negative in the entire range of Am contents using the PBEsol+

U calculations. The calculated result suggests that there is no phase separation related to the variation of Am content in the solid solution. The mixing enthalpy of (U, Am)O

2 display a regular evolution as a function of the Am content. For Am content equal to 0.75, the mixed oxide is more stable than all the other compositions.

3.4. Elastic properties of the (U, Am)O2 using PBEsol+U

As listed in

Table 4, three elastic constants

C11,

C12 and

C44 of UO

2, (U

0.25Am

0.75)O

2, (U

0.5Am

0.5)O

2 and (U

0.75Am

0.25)O

2 and AmO

2 cubic structures were calculated. Compared with the limited experimental and theoretical results, our calculated results by PBEsol+

U method are close to those of GGA at a

U value of 4.0 eV [

19]. The incorporation of different amounts of Am into UO

2 significantly reduced

C11 and approached the value of AmO

2 at 75%, while C

12 also decreased while

C44 did not change significantly. In the (U, Am)O

2 system, with the increase of Am content in the UO

2 matrix, the calculated elastic constants in the

C11 and

C12 directions decrease significantly especially in the

C11 direction, while the

C44 direction increases slightly. At the same time, the obtained bulk modulus

B0 decrease significantly with the increase of Am content in the (U, Am)O

2 system. Since there are no experimental measurements of the mechanics of the (U, Am)O

2 mixed oxides, we only compare and analyze the calculated results of DFT+

U with the experimental values of UO

2.

The bulk modulus of UO

2 calculated by the PBEsol+

U method is 212 GPa, which is very close to the experimental results. The calculated results of the bulk modulus of AmO

2 are the same as the results of Njifon et al., and slightly higher than the experimental value. However, it is very important to obtain the elastic constants of these oxide systems in different functional forms. The elastic constants

C11,

C12 and

C44 and bulk modulus

B0 of UO

2, PuO

2 and the mixed oxides (U, Pu)O

2 are listed in Table S4. Compared with the experimental values of UO

2 [

7], the calculated results of

C11 and

C12 are 383 GPa and 126 GPa respectively which are very close to the experimental results, and

C44 (72 GPa) is slightly higher than the experimental value (60 GPa).

For

Table 4 and S4, comparing the contents of different Pu and Am in UO

2, the influence of the elastic constants of the mixed oxides (U, Pu)O

2 and (U, Am)O

2 structures in different directions is different, that is, the incorporation of Pu into the UO

2 structure increases the elastic constants of (U, Pu)O

2, while the incorporation of Am into the UO

2 structure decreases the elastic constants of (U, Am)O

2, especially in the direction of

C11, and has little effect on the direction of

C12 and

C44. Thus, the elastic properties of the (U, Am)O

2 mixed oxides are reported for the first time by means of theoretical simulations, which provides theoretical support for further experimental verification and further development of nuclear fuel U-Am mixed oxides.

4. Conclusions

In this work, we calculated and analyzed the changes in the structure, energy, and elastic properties of UO2, AmO2 and mixed oxides (U, Am)O2 using PBEsol+U method. In fact, we use first principles approach to explore the influence of different defect structures of Am aggregation on the atomic-scale crystal structure of the fuel in the mixed oxides systems. First of all, we used the PBEsol+U method to obtain that the structural and energetic properties of UO2 and AmO2 are consistent with the experimental results. Then, in the calculation of the mixed oxides (U, Am)O2, the results show that the substitution of Am in the UO2 matrix will reduce the volume of the nuclear fuel and seriously affect the energy of the nuclear fuel.

In fact, when the volume of the (U, Am)O2 structure with 25% Am content is about 4.7% lower than that of UO2, the energy of formation of (U, Am)O2 is about 30% lower than that of UO2. In particular, with the increase of Am contents, there are obvious differences in the properties of the mixed oxides, especially the change trend of energy of formation. For the (U, Am)O2 mixed oxides, the lattice parameters and the energy of formation are reduced as the Pu aggregation content increases in UO2 matrix, especially the energy of formation of this mixed oxides systems.

In the meanwhile, the results of electronic structure calculations show that the bandgap value in the mixed oxides systems decreases with the increase of Am, which is very important for the thermodynamic transport of the mixed oxides fuels. The mixing enthalpy calculations showing that the (U, Am)O2 mixed oxides is a stable solid solution for all Am contents. Finally, we discussed the elastic properties of the mixed oxides (U, Am)O2, and the results showed that with the increase of the content of Am in the UO2 matrix, the elasticity of the system C11 and C44 decreased significantly. Moreover, the bulk modulus also shows the same decreasing characteristics.

Data Availability Statement

No data was used for the research described in the article.

Acknowledgments

Financial support from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 12264007) is acknowledged.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

- J.E. Kelly, Generation IV international forum: a decade of progress through international cooperation, Prog. Nucl. Energ. 77 (2014) 240-246. [CrossRef]

- D.C. Crawford, D.L. D.C. Crawford, D.L. Porter, S.L. Hayes, Fuels for sodium-cooled fast reactors: US perspective, J. Nucl. Mater. 371 (2007) 202-231. [CrossRef]

- R. Parrish, A. R. Parrish, A. Aitkaliyeva, A review of microstructural features in fast reactor mixed oxides fuels, J. Nucl. Mater. 510 (2018) 644-660. [CrossRef]

- B. Dorado, P. B. Dorado, P. Garcia, First-principles DFT+U modeling of actinide-based alloys: Application to paramagnetic phases of UO2 and (U, Pu) mixed oxides, Phys. Rev. B 87 (2013) 195139. /: https. [CrossRef]

- I.C. Njifon, M. I.C. Njifon, M. Bertolus, R, Hayn, F. Michel, Electronic structure investigation of the bulk properties of uranium-plutonium mixed oxides (U, Pu)O2, Inorg. Chem. 57 (2018) 10974-10983. [CrossRef]

- M.S.T. Noutack, G. M.S.T. Noutack, G. Jomard, M. Freyss, G. Geneste, Structural, electronic and energetic properties of uranium-americium mixed oxides U1-yAmyO2 using DFT+U calculations, J. Phys. Condens. Mat. 31 (2019) 485501. [CrossRef]

- G. Rev. B 59 (1999) 1758–1775. [CrossRef]

- P. Rev. B 50 (1994) 17953–17979. [CrossRef]

- G. Kresse, J. G. Kresse, J. Hafner, Ab initio molecular dynamics for open-shell transition metals, Phys. Rev. B 47 (1993) 558-561. [CrossRef]

- G. Kresse, J. G. Kresse, J. Furthmüller, Efficiency of ab-initio total energy calculations for metals and semiconductors using a plane-wave basis set, Comput. Mater. Sci. 6 (1996) 15-50. [CrossRef]

- G. Kresse, J. G. Kresse, J. Furthmüller, Efficient iterative schemes for ab initio total-energy calculations using a plane-wave basis set, Phys. Rev. B: Condens. Matter. 54 (1996) 11169-11186. [CrossRef]

- T. Adv. 9 (2019) 31398–31405. [CrossRef]

- T. Liu, S.C. T. Liu, S.C. Li, T. Gao, B.Y. Ao, Density functional investigation of fluorite-based Pa2O5 phases: structure and properties, Chinese J. Phys. 664 (2020) 115-122. [CrossRef]

- T.P. James, A.A. T.P. James, A.A. Xavier, S. Mark, H.L. Nora, DFT+U study of the structures and properties of the actinide dioxides, Chinese J. Phys. 492 (2017) 269-278. [CrossRef]

- J.P. Perdew, K. J.P. Perdew, K. Burke, M. Ernzerhof, Generalized gradient approximation made simple. Phys. Rev. Lett. 77 (1996) 3865-3868. [CrossRef]

- V.I. Anisimov, J. V.I. Anisimov, J. Zaanen, O.K. Andersen, Band theory and mott insulators: hubbard U instead of stoner I, Phys. Rev. B. 44 (1991) 943-954. [CrossRef]

- A.I. Liechtenstein, V.I. A.I. Liechtenstein, V.I. Anisimov, J. Zaanen, Density functional theory and strong interactions: orbital ordering in mott-hubbard insulators. Phys. Rev. B 52 (1995) 5467-5470. [CrossRef]

- E. Vathonne, J. E. Vathonne, J. Wiktor, M, Freyss, G. Jomard, M. Bertolus, DFT+U investigation of charged point defects and clusters in UO2, J. Phys. Condens. Mat. 26 (2014) 325501. [CrossRef]

- S.L. Dudarev, G.A. S.L. Dudarev, G.A. Botton, S.Y. Savrasov, Z. Szotek, W.M. Temmerman, A.P. Sutton, Electronic structure and elastic properties of strongly correlated metal oxides from first principles: LSDA+U, SIC-LSDA and EELS study of UO2 and NiO, Phys. Status. Solidi. A 166 (1998) 429-443. [CrossRef]

- A. Kotani, H. A. Kotani, H. Ogasawara, Theory of core-level spectroscopy in actinide systems, Physica B: Condensed Matter. 186-188, (1993) 16-20. [CrossRef]

- G. Rev. B 78 (2008) 075125. [CrossRef]

- M.S.T. Noutack, G. M.S.T. Noutack, G. Geneste, G. Jomard, M. Freyss, First-principles investigation of the bulk properties of americium dioxide and sesquioxides, Phys. Rev. Mater. 3(3) (2019) 035001-1-13. [CrossRef]

- D.A. Andersson, J. D.A. Andersson, J. Lezama, B.P. Uberuaga, C. Deo, S.D. Conradson, Cooperativity among defect sites in AO2+x and A4O9(A=U, Np, Pu): density functional calculations, Phys. Rev. B. 79 (2009) 024110. [CrossRef]

- B. Dorado, P. B. Dorado, P. Garcia, G. Carlot, C. Davoisne, M. Fraczkiewicz, B. Pasquet, M. Freyss, C. Valot, G. Baldinozzi, D. Simëone, M. Bertolus, First-principles calculation and experimental study of oxygen diffusion in uranium dioxide. Phys. Rev. B. 83 (2011) 035126. [CrossRef]

- J. Rev. B. 88 (2013) 024109. [CrossRef]

- I.D. Prodan, G.E. I.D. Prodan, G.E. Scuseria, J.A. Sordo, K.N. Kudin, R.L. Martin, Lattice defects and magnetic ordering in plutonium oxides: a hybrid density-functional-theory study of strongly correlated materials, J. Chem. Phys. 123 (2005) 014703. [CrossRef]

- I.D. Prodan, G.E. I.D. Prodan, G.E. Scuseria, R.L. Martin, Assessment of metageneralized gradient approximation and screened coulomb hybrid density functionals on bulk actinide oxides, Phys. Rev. B. 73 (2006) 045104. [CrossRef]

- P. Santini, S.G. P. Santini, S.G. Carretta, Amoretti, R. Caciuffo, N. Magnani, G.H. Lander, Multipolar interactions in f-electron systems: the paradigm of actinide dioxides, Rev. Mod. Phys. 81 (2009) 807-863. [CrossRef]

- R. Caciuffo, G. R. Caciuffo, G. Amoretti, P. Santini, G.H. Lander, J. Kulda, P.V.D. Plessis, Magnetic excitations and dynamical Jahn-Teller distortions in UO2, Phys. Rev. B: Condens. Matter Mater. Phys. 59 (1999) 13892-13900. [CrossRef]

- S.B. Wilkins, R. S.B. Wilkins, R. Caciuffo, C. Detlefs, J. Rebizant, E. Colineau, F. Wastin, G.H. Lander, Direct observation of electric-quadrupolar order in UO2, Phys. Rev. B. 73 (2006) 060406. [CrossRef]

- R. Laskowski, G.K.H. R. Laskowski, G.K.H. Madsen, P. Blaha, K. Schwarz, Magnetic structure and electric-field gradients of uranium dioxide: an ab initio study, Phys. Rev. B. 69 (2004) 140408. [CrossRef]

- P. Martin, S. P. Martin, S. Grandjean, C. Valot, G. Carlot, M. Ripert, P. Blanc, C. Hennig, XAS study of (U1−yPuy)O2 solid solutions, J. Alloys Compnd. 444 (2007) 410-414. [CrossRef]

- C. Hurtgen, J. C. Hurtgen, J. Fuger, Self-irradiation effects in americium oxides, Inorg. Nucl. Chem. Lett. 13 (1977) 179-188. [CrossRef]

- E.J. Huber, C.E. E.J. Huber, C.E. Holley, Enthalpies of formation of triuranium octaoxide and uranium dioxide, J. Chem. Thermodyn. 1 (1969) 267-272. [CrossRef]

- G.K. Johnson, E.H. G.K. Johnson, E.H. Van Deventer, O.L. Kruger, W. N. Hubbard, The enthalpies of formation of plutonium dioxide and plutonium mononitride, J. Chem. Thermodyn. 1 (1969) 89-98. [CrossRef]

- C. Guéneau, M. C. Guéneau, M. Baichi, D. Labroche, C. Chatillon, B. Sundman, Thermodynamic assessment of the uranium-oxygen system, J. Nucl. Mater. 304 (2002) 161-175. [CrossRef]

- C. Guéneau, C. C. Guéneau, C. Chatillon, B. Sundman, Thermodynamic modelling of the plutonium-oxygen system, J. Nucl. Mater. 378 (2008) 257-272. [CrossRef]

- R.J.M. Konings, O. R.J.M. Konings, O. Beneš, A. Kovács, D. Manara, D. Sedmidubský, L. Gorokhov, V.S. Iorish, V. Yungman, E. Shenyavskaya, and E. Osina, The thermodynamic properties of the f-elements and their compounds. Part 2. The lanthanide and actinide oxides, J. Phys. Chem. Ref. Data 43 (2014) 013101. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).