Submitted:

31 July 2024

Posted:

02 August 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results

2.1. Respondents’ Socio-Demographic Characteristics

2.2. Sources of Drug Procurement in Study Households

2.3. Recognition of Antibiotics

- -

- Amoxicillin was the only antibiotic that was named by its drug name. The others were identified by their colours:

- -

- Amoxicillin: amoxicillin or ‘toupaye white head’

- -

- Oxytetracycline: ‘toupaye red head’

- -

- Norfloxacin: ‘toupaye chinois’ or ‘Chinese toupaye’

- -

- Ampicillin: ‘toupaye black head’

2.4. Commonly Used Antibiotics

2.5. Health Complaints Leading to ABU

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Study Context

4.2. Study Sites

4.3. Study Participants and Sampling Strategies

4.4. Data Collection Procedures

4.5. Data Processing and Analysis

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Marquardt, R.R.; Li, S. Antimicrobial resistance in livestock: Advances and alternatives to antibiotics. Anim Front. 2018, 8, 30–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Klein, E.Y.; Van Boeckel, T.P.; Martinez, E.M.; Pant, S.; Gandra, S.; Levin, S.A.; Goossens, H.; Laxminarayan, R. Global increase and geographic convergence in antibiotic consumption between 2000 and 2015. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2018, 115, E3463–E3470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Boeckel, T.P.; Brower, C.; Gilbert, M.; Grenfell, B.T.; Levin, S.A.; Robinson, T.P.; Teillant, A.; Laxminarayan, R. Global trends in antimicrobial use in food animals. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2015, 112, 5649–5654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gebeyehu, E.; Bantie, L.; Azage, M. Inappropriate use of antibiotics and its associated factors among urban and rural communities of Bahir Dar city administration, northwest Ethiopia. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0138179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barker, A.K.; Brown, K.; Ahsan, M.; Sengupta, S.; Safdar, N. Social determinants of antibiotic misuse: a qualitative study of community members in Haryana, India. BMC Public Health 2017, 17, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Afari-Asiedu, S.; Oppong, F.B.; Tostmann, A.; Ali Abdulai, M.; Boamah-Kaali, E.; Gyaase, S.; Agyei, O.; Kinsman, J.; Hulscher, M.; Wertheim, H.F.L.; et al. Determinants of inappropriate antibiotics use in rural central Ghana using a mixed methods approach. Front Public Health. 2020, 8, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- WHO. Global action plan on antimicrobial resistance; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Zanichelli, V.; Sharland, M.; Cappello, B.; Moja, L.; Getahun, H.; Pessoa-Silva, C.; Sati, H.; van Weezenbeek, C.; Balkhy, H.; et al. The WHO AWaRe (Access, Watch, Reserve) antibiotic book and prevention of antimicrobial resistance. Bull World Health Organ. 2023, 101, 290–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WHO. The WHO AWaRe (Access, Watch, Reserve) antibiotic book; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Frost, I.; Kapoor, G.; Craig, J.; Liu, D.; Laxminarayan, R. Status, challenges and gaps in antimicrobial resistance surveillance around the world. J Glob Antimicrob Resist. 2021, 25, 222–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sié, A.; Ouattara, M.; Bountogo, M.; Dah, C.; Compaoré, G.; Boudo, V.; Lebas, E.; Brogdon, J.; Nyatigo, F.; Arnold, B.F.; et al. Indication for antibiotic prescription among children attending primary healthcare services in rural Burkina Faso. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2021, 73, 1288–1291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sié, A.; Coulibaly, B.; Adama, S.; Ouermi, L.; Dah, C.; Tapsoba, C.; Bärnighausen, T.; Kelly, J.D.; Doan, T.; Lietman, T.M.; Keenan, J.D.; Oldenburg, C.E. Antibiotic prescription patterns among children younger than 5 years in Nouna district, Burkina Faso. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2019, 100, 1121–1124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Valia, D.; Ingelbeen, B.; Kaboré, B.; Karama, I.; Peeters, M.; Lompo, P.; Vlieghe, E.; Post, A.; Cox, J.; de Mast, Q.; et al. Use of WATCH antibiotics prior to presentation to the hospital in rural Burkina Faso. Antimicrob Resist Infect Control. 2022, 11, 59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organisation. Antimicrobial resistance:Key facts. 2023. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/antimicrobial-resistance (accessed on 29 July 2024).

- Dixon, J.; MacPherson, E.; Manyau, S.; Nayiga, S.; Khine Zaw, Y.; Kayendeke, M.; Nabirye, C.; Denyer Willis, L.; de Lima Hutchison, C.; Chandler, C.I.R. The ‘Drug Bag’ method: lessons from anthropological studies of antibiotic use in Africa and South-East Asia. Glob Health Action. 2019, 12:1639388.

- Olivé, F.X.; John-Langba, J.; Tran, TK.; Sunpuwan, M.; Sevene, E.; Nguyen, H.H.; Ho, P.D.; Matin, M.A.; Ahmed, S.; Karim, M,M.; Cambaco, O.; Afari-Asiedu, S.; Boamah-Kaali, E.; Abdulai, M.A.; Williams, J.; Asiamah, S.; Amankwah, G.; Agyekum, M.P.; Wagner, F.; Ariana, P.; Sigauque, B.; Tollman, S.; van Doorn, H.R.; Sankoh, O.; Kinsman, J.; Wertheim, H.F.L. Community-based antibiotic access and use in six low-income and middle-income countries: a mixed-method approach. Lancet Glob Health. 2021, 9:e610–619.

- Kretchy, J-P.; Adase ,S.K.; Gyansa-Lutterodt, M. The prevalence and risks of antibiotic self-medication in residents of a rural community in Accra, Ghana. Sci Afr. 2021, 14:e01006.

- Mabilika, R.J.; Mpolya, E.; Shirima, G. Prevalence and predictors of self-medication with antibiotics in selected urban and rural districts of the Dodoma region, Central Tanzania: a cross-sectional study. Antimicrob Resist Infect Control. 2022, 11:1–9.

- Ministry of Health BF. Liste nationale des medicaments essentiels et autres produits de santé. Ministère de la santé. 2020.

- van der Geest, S.; Whyte, S.R. The charm of medicines: Metaphors and metonyms. Med Anthropol Q. 1989, 3, 345–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poonam Khetrapal Singh. Water, sanitation, and hygiene: An essential ally in a superbug age. WHO.Int. 2017. Available online: https://www.who.int/southeastasia/news/opinion-editorials/detail/water-sanitation-and-hygiene-an-essential-ally-in-a-superbug-age (accessed on 29 July 2024).

- Pinto Jimenez, C.E.; Keestra, S.; Tandon, P.; Cumming, O.; Pickering, A.J.; Moodley, A.; Chandler, C.I.R. Biosecurity and water, sanitation, and hygiene (WASH) interventions in animal agricultural settings for reducing infection burden, antibiotic use, and antibiotic resistance: a One Health systematic review. Lancet Planet Health. 2023, 7:e418–434. e: 7.

- Bürgmann, H.; Frigon, D.; Gaze, W.H.; Manaia, C.M.; Pruden, A.; Singer, A.C.; F Smets, B.; Zhang, T. Water and sanitation: An essential battlefront in the war on antimicrobial resistance. FEMS Microbiol Ecol. 2018, 94, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Denyer Willis, L.; Chandler, C. Quick fix for care, productivity, hygiene and inequality: Reframing the entrenched problem of antibiotic overuse. BMJ Case Rep. 2019, 4, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mboya, E.A.; Davies, M.L.; Horumpende, P.G.; Ngocho, J.S. Inadequate knowledge on appropriate antibiotics use among clients in the Moshi municipality Northern Tanzania. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0239388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodrigues, C.F. Self-medication with antibiotics in Maputo, Mozambique: practices, rationales and relationships. Palgrave Commun. 2020, 6, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bloom, G.; Standing, H.; Lucas, H.; Bhuiya, A.; Oladepo, O.; Peters, D.H. Making health markets work better for poor people: The case of informal providers. Health Policy Plan. 2011, 26, 45–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Angbo-Effi, K.O.; Kouassi, D.P.; Yao, G.H.A.; Douba, A.; Secki, R.; Kadjo, A. Determinants of street drug use in urban areas. Sante Publique (Paris). 2011, 23, 455–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dagrou, A.; Chimhutu, V. I buy medicines from the streets because I am poor: A qualitative account on why the informal market for medicines thrive in Ivory Coast. Inquiry (United States). 2022, 59, 1–10.

- Tipke, M.; Diallo, S.; Coulibaly, B.; Störzinger, D.; Hoppe-Tichy, T.; Sie, A.; Müller, O. Substandard anti-malarial drugs in Burkina Faso. Malar J. 2008, 7, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hoellein, L.; Kaale, E.; Mwalwisi, .Y.H.; Schulze, M.H.; Vetye-Maler, C.; Holzgrabe, U. Emerging antimicrobial drug resistance in Africa and Latin America: search for reasons. Risk Manag Healthc Policy 2022, 15, 827–843.

- WHO. A study on public health and socioeconomic impact of substandard and falsified medicines. World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, Geneva. 2017.

- Gnegel, G.; Hauk, C.; Neci, R.; Mutombo, G.; Nyaah, F.; Wistuba, D.; Häfele-Abah, C.; Heide, L. Identification of falsified chloroquine tablets in Africa at the time of the COVID-19 pandemic. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2020, 103, 73–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- WHO. Substandard and falsified medical products - Fact sheets [Internet]. World Health Organization. 2018. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/substandard-and-falsified-medical-products (accessed on 29 July 2024).

- Monnier, A.A.; Do, N.T.T.; Asante, K.P.; Afari-Asiedu, S.; Khan, W.A.; Munguambe, K.; Sevene, E.; Tran, T.K.; Nguyen, C.T.K.; Punpuing, S.; et al. Is this pill an antibiotic or a painkiller ? Improving the identification of oral antibiotics for better use. Lancet Glob Health. 2023, 11, e1308–e1313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mira, J.J.; Ortiz, L.; Lorenzo, S.; Royuela, C.; Vitaller, J.; Pérez-Jover, V. Oversights, confusions and misinterpretations related to self-care and medication in diabetic and renal patients. Medical Principles and Practice 2014, 23, 246–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tranchard, F.; Gauthier, J.; Hein, C.; Lacombe, J.; Brett, K.; Villars, H.; Sallerin, B.; Montastruc, J.L.; Despas, F. Drug identification by the patient: Perception of patients, physicians and pharmacists. Therapie, 2019, 74, 591–598.

- Afari-Asiedu, S.; Hulscher, M.; Abdulai, M.A.; Boamah-Kaali, E.; Asante, K.P.; Wertheim, H.F.L. Every medicine is medicine; exploring inappropriate antibiotic use at the community level in rural Ghana. BMC Public Health. 2020, 20, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

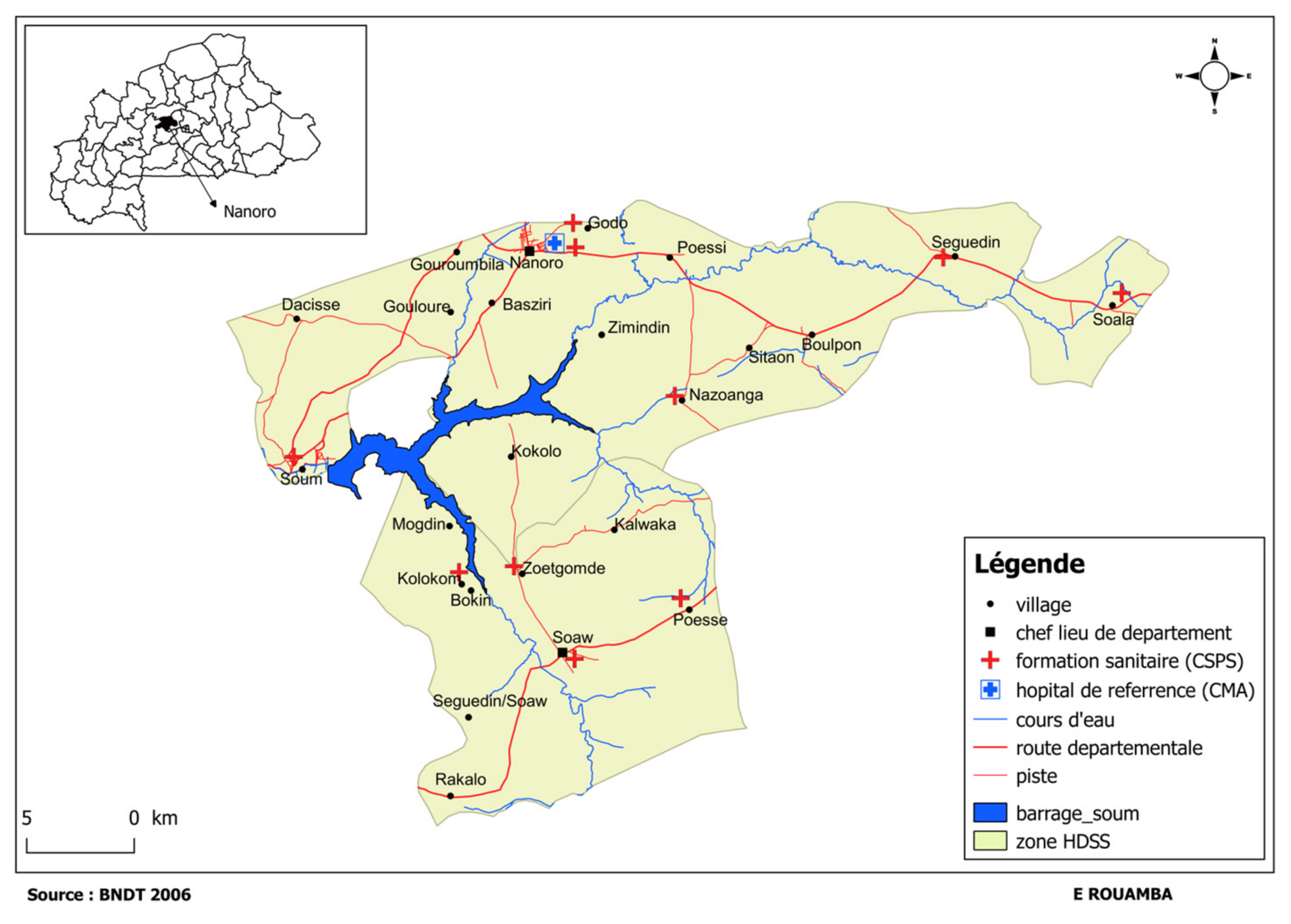

- Derra, K.; Rouamba, E.; Kazienga, A.; Ouedraogo, S.; Tahita, M.C.; Sorgho, H.; Valea, I.; Tinto, H. Profile: Nanoro health and demographic surveillance system. Int J Epidemiol. 2012, 41, 1293–1301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ministry of Health BF. Annuaire Statistique 2020. Ministère de la Santé Burkina Faso (DGESS). 2021.

- Zida, Y.; Kambou, S.H. Cartographie de la pauvreté et des inégalités au Burkina Faso. PNUD 2014. Available online: https://www.undp.org/fr/burkina-faso/publications/cartographie-de-la-pauvrete-et-des-inegalites-au-burkina-faso (accessed on 29 July 2024).

- Tinto, H.; Valea, I.; Sorgho, H.; Tahita, M.C.; Traore, M.; Bihoun, B.; Guiraud, I.; Kpoda, H.; Rouamba, J.; Ouédraogo, S.; Lompo, P.; Yara, S.; Kabore, W.; Ouédraogo, J.B.; Guiguemdé, R.T.; Binka, F.N.; Ogutu, B. The impact of clinical research activities on communities in rural Africa : the development of the Clinical Research Unit of Nanoro (CRUN) in Burkina Faso. Malar J. 2014, 13:113.

- Ministry of Health BF. Annuaire Statistique 2016. Ministère de la Santé Burkina Faso (DGESS). 2017.

- Maltha, J.; Guiraud, I.; Kaboré, B.; Lompo, P.; Ley, B.; Bottieau, E.; Van Geet, C.; Tinto, H.; Jacobs, J. Frequency of severe malaria and invasive bacterial infections among children admitted to a rural hospital in Burkina Faso. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e89103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Overall | Nanoro | Nazoanga | Gouroumbila | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | 423 | 232 | 125 | 66 | |

| Gender = Male, n (%) | 175 (41.4) | 99 (42.7) | 52 (41.6) | 24 (36.4) | |

| Main occupation, n (%): | Agriculture/farming | 271 (64.1) | 97 (41.8) | 115 (92.0) | 59 (89.4) |

| Merchant | 46 (10.9) | 44 (19.0) | 2 (1.6) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Pupils/student | 27 (6.4) | 25 (10.8) | 1 (0.8) | 1 (1.5) | |

| Others | 19 (4.5) | 12 (5.2) | 3 (2.4) | 4 (6.1) | |

| Artist | 17 (4.0) | 14 (6.0) | 2 (1.6) | 1 (1.5) | |

| Private sector officer | 16 (3.8) | 16 (6.9) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Government officer | 11 (2.6) | 9 (3.9) | 2 (1.6) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Housewife | 9 (2.1) | 9 (3.9) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | |

| None | 6 (1.4) | 5 (2.2) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (1.5) | |

| Independent | 1 (0.2) | 1 (0.4) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Level of education, n (%): | Uneducated | 243 (57.4) | 110 (47.4) | 94 (75.2) | 39 (59.1) |

| Incomplete primary school | 55 (13.0) | 29 (12.5) | 19 (15.2) | 7 (10.6) | |

| Non formal education | 38 (9.0) | 17 (7.3) | 6 (4.8) | 15 (22.7) | |

| Incomplete secondary | 48 (11.3) | 45 (19.4) | 1 (0.8) | 2 (3.0) | |

| Secondary | 17 (4.0) | 13 (5.6) | 3 (2.4) | 1 (1.5) | |

| Primary school | 12 (2.8) | 9 (3.9) | 1 (0.8) | 2 (3.0) | |

| Advanced study | 10 (2.4) | 9 (3.9) | 1 (0.8) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Drug storing, n (%): | No | 217 (51.3) | 105 (45.3) | 82 (65.6) | 30 (45.5) |

| Yes | 206 (48.7) | 127 (54.7) | 43 (34.4) | 36 (54.5) |

| Source of drug procurement* | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Primary health care facility | 324 (76.6) |

| Informal drug sellers | 259 (61.2) |

| Private drug sellers | 241 (57.0) |

| Hospital | 109 (25.8) |

| Traditional/faith healers | 8 (1.9) |

| Neighbour/friends | 5 (1.2) |

| Other family member | 2 (0.5) |

| Community health workers | 2 (0.5) |

| Antibiotics (N=423) | n | % |

|---|---|---|

| Amoxicillin tablet | 398 | 93.4 |

| Oxytetracycline tablet | 369 | 86.6 |

| Ampicillin tablet | 298 | 70.0 |

| Metronidazole tablet | 295 | 69.2 |

| Norfloxacin tablet | 293 | 68.8 |

| Amoxicillin suspension | 247 | 58.0 |

| Ciprofloxacin tablet | 210 | 49.3 |

| Cotrimoxazole tablet | 210 | 49.3 |

| Penicillin v tablet | 204 | 47.9 |

| Gentamicin eye/ear | 203 | 47.7 |

| Lincomycin tablet | 203 | 47.9 |

| Gentamicin eye | 200 | 46.9 |

| Metronidazole suspension | 191 | 44.8 |

| Cotrimoxazole suspension | 181 | 42.5 |

| Erythromycin steraete tablet | 181 | 42.5 |

| Erythromycin stereate suspension | 172 | 40.4 |

| Cipro eye/ear drop | 130 | 30.5 |

| Cloxacillin sodium suspension | 121 | 28.4 |

| Diloxanide metronidazole suspension | 104 | 24.4 |

| Clavulanic acid tablet | 89 | 20.9 |

| Cefixime suspension | 85 | 20.0 |

| Penicillin injection | 82 | 19.2 |

| Ampicillin sodique | 82 | 19.2 |

| Cloxacillin tablet | 76 | 17.8 |

| Clavulanic acid suspension | 76 | 17.8 |

| Ciprofloxacin tinidazole | 62 | 14.6 |

| Ceftriaxone injection | 60 | 14.1 |

| Cefixime tablet | 58 | 13.6 |

| Azithromycin tablet | 47 | 11.0 |

| Clavulanic acid injection | 42 | 9.9 |

| Neomycin polydexa | 40 | 9.4 |

| Clarithromycin tablet | 35 | 8.2 |

| Flucloxacin tablet | 20 | 4.7 |

| Antibiotics | N* | % |

|---|---|---|

| Amoxicillin tablet | 367 | 10.8 |

| Oxytetracycline tablet | 288 | 8.5 |

| Ampicillin tablet | 245 | 7.2 |

| Metronidazole tablet | 239 | 7.0 |

| Norfloxacin tablet | 223 | 6.6 |

| Amoxicillin suspension | 200 | 5.9 |

| Co-trimoxazole tablet | 157 | 4.6 |

| Gentamicin eye/ear (drop) | 147 | 4.3 |

| Metronidazole suspension | 142 | 4.2 |

| Ciprofloxacin tablet | 135 | 4.0 |

| Co-trimoxazole suspension | 134 | 3.9 |

| Gentamicin oeil (gouttes) | 130 | 3.8 |

| Penicillin V tablet | 127 | 3.7 |

| Lincomycin tablet | 115 | 3.4 |

| Erythromycin Stearate suspension | 107 | 3.1 |

| Erythromycin Stearate tablet | 88 | 2.6 |

| Diloxanide furoate metronidazole suspension | 74 | 2.2 |

| Cloxacillin sodium suspension | 71 | 2.1 |

| Ciprofloxacin eye/ear drop (Boncipro) | 65 | 1.9 |

| Amoxicillin/Clavulanic Acid tablet | 48 | 1.4 |

| Cefixime (Ceficap) Suspension | 48 | 1.4 |

| Amoxicillin/Clavulanic Acid suspension | 39 | 1.1 |

| Penicillin V injection | 32 | 0.9 |

| Cefixime tablet | 28 | 0.8 |

| Ceftriaxone Injection | 26 | 0.8 |

| Ampicillin Sodium (injection) | 23 | 0.7 |

| Azithromycin tablet | 19 | 0.6 |

| Amoxicillin/ Acid Clavulanic injection (Clavuject) | 18 | 0.5 |

| Ciprofloxacin Tinidazole (Ciprozole Forte) tablet | 17 | 0.5 |

| Neomycin+Polymyxine B oeil (goutte) | 15 | 0.4 |

| Clarithromycin tablet (Clariva) | 14 | 0.4 |

| Cloxacillin tablet | 14 | 0.4 |

| Flucloxacillin tablet | 6 | 0.2 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).