Submitted:

01 August 2024

Posted:

01 August 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results

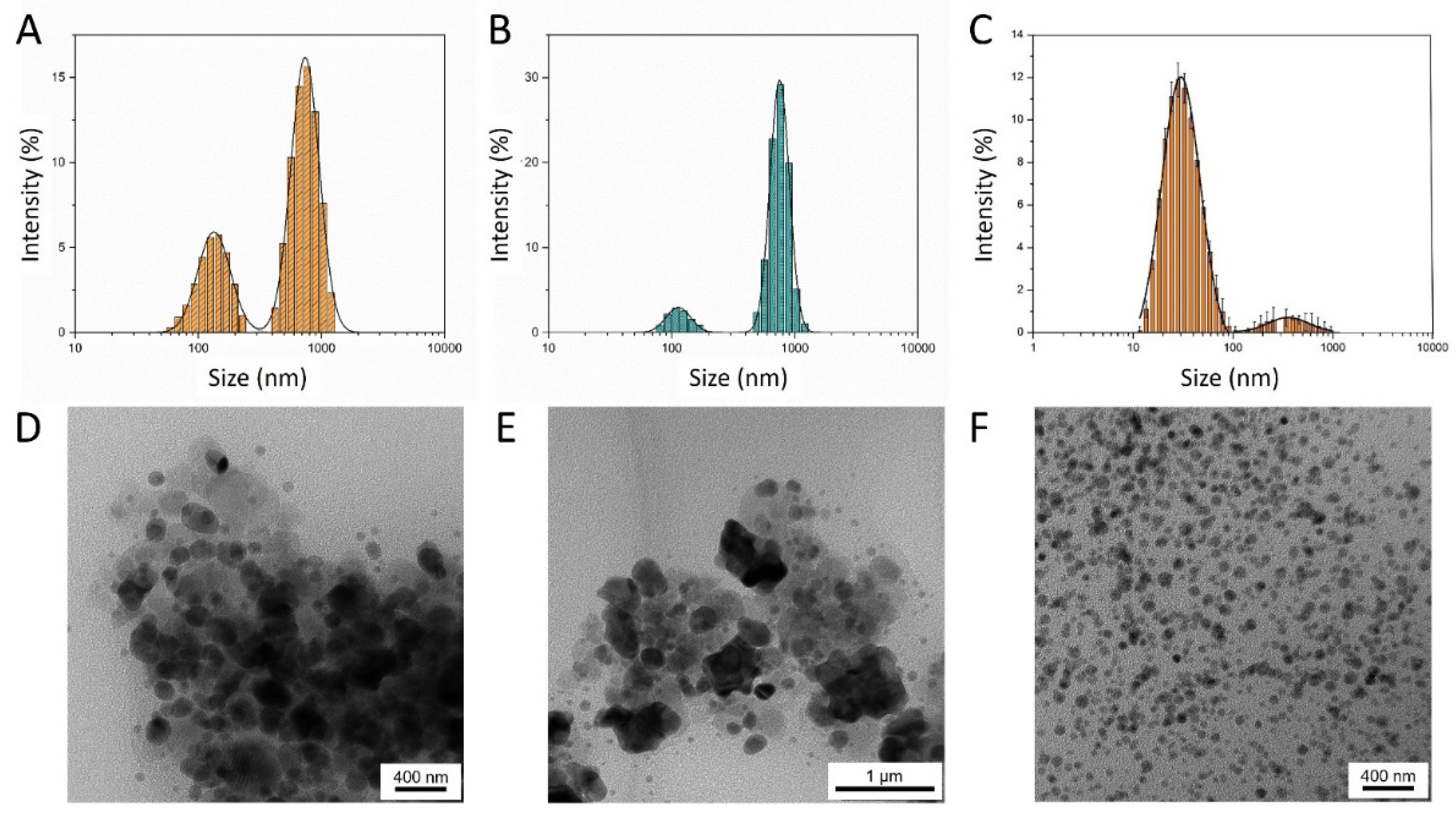

2.1. Morphologycal and Hydrodynamic Characterization

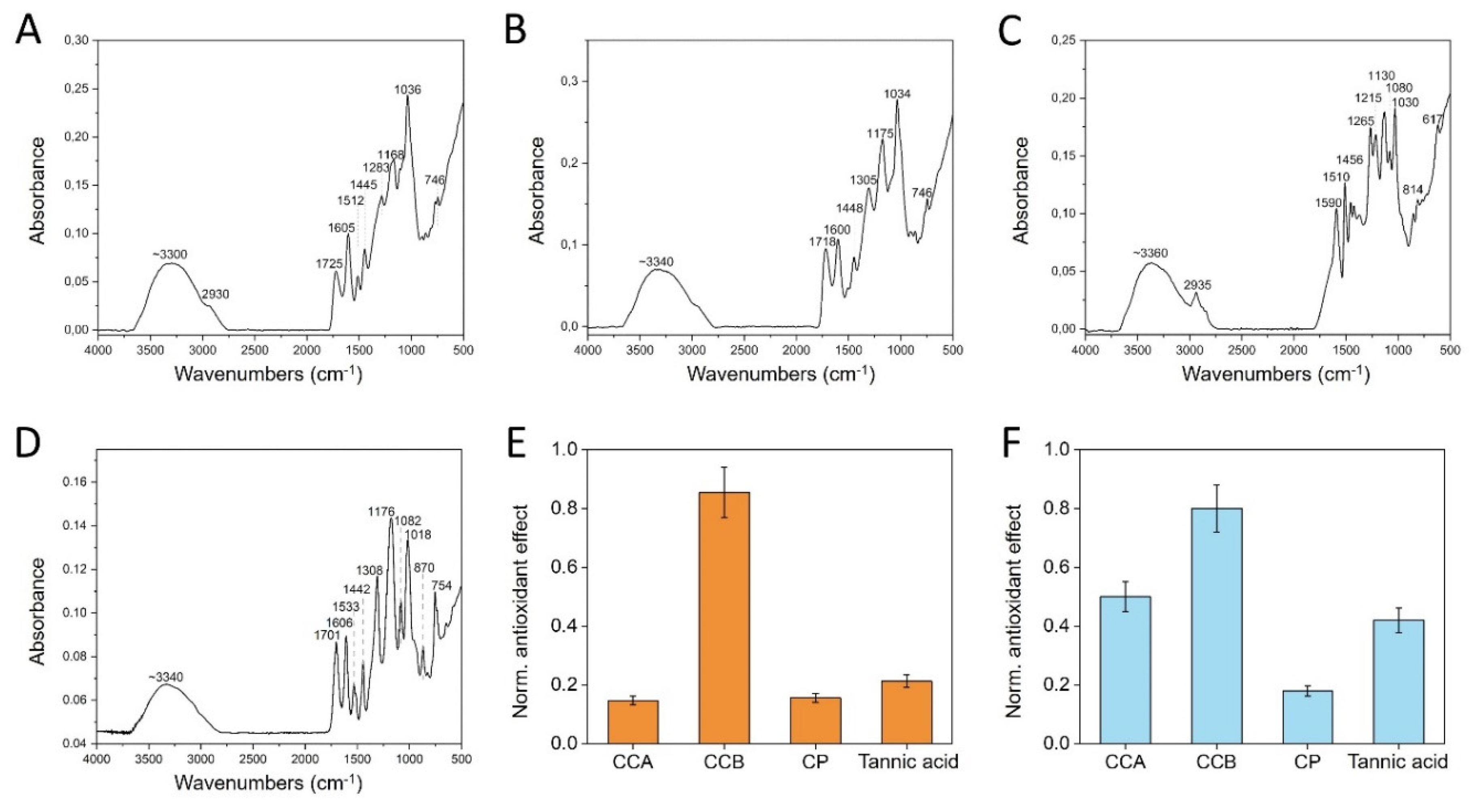

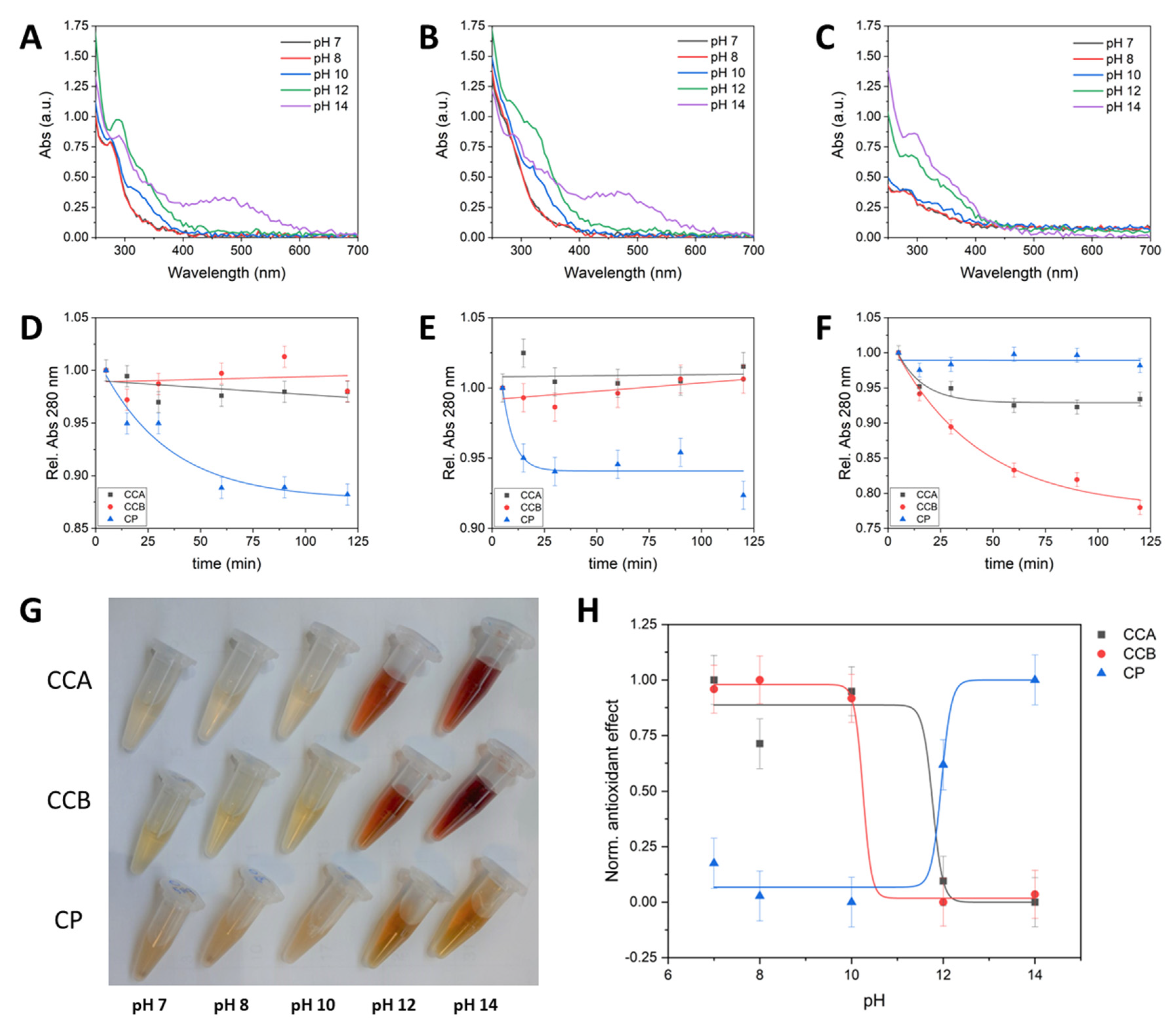

2.2. Chemical-Physical Characterization

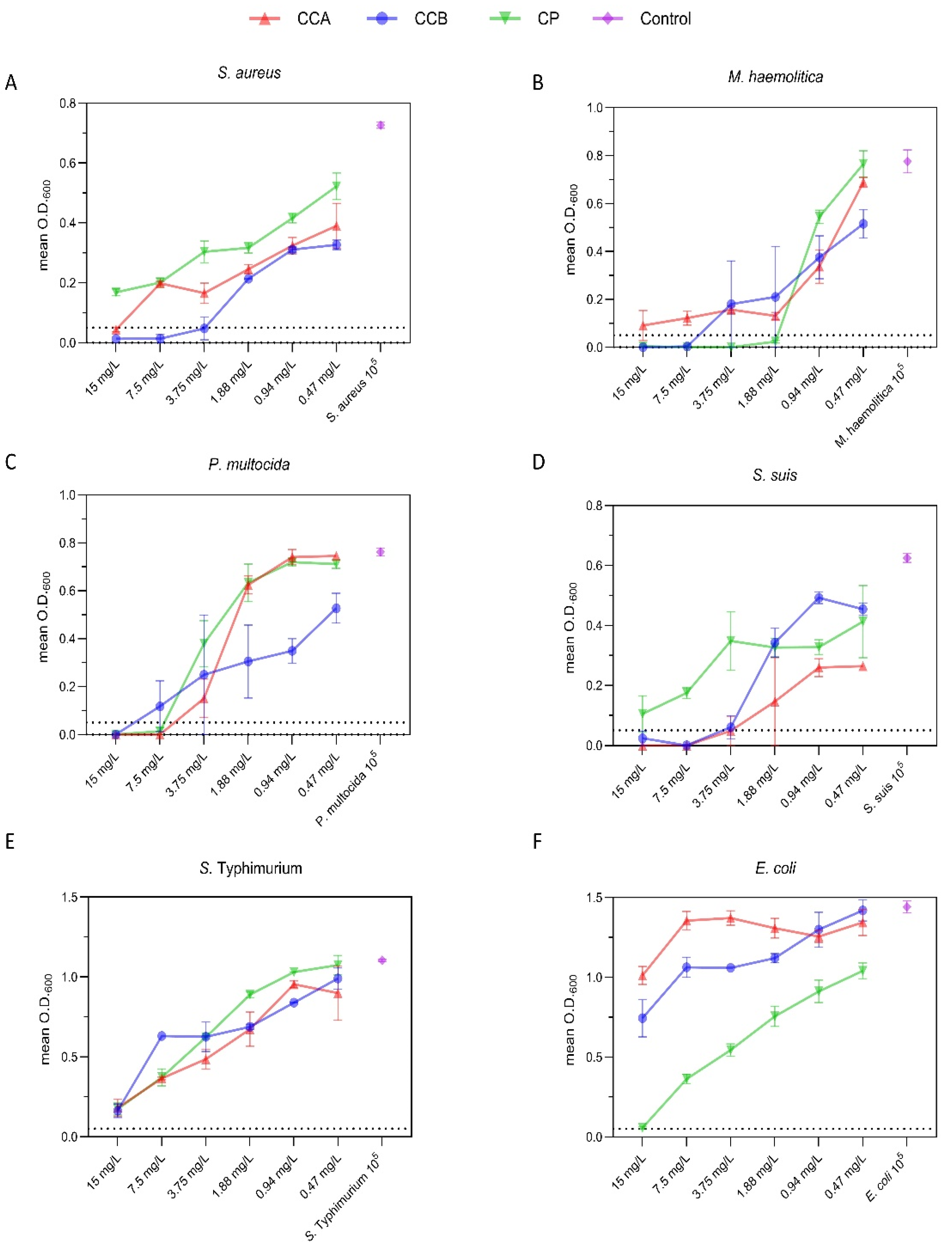

2.3. Minimum Inhibitory Concentration (MIC) of Phenolic Compounds on Selected Bacteria

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Materials

4.2. Methods

4.3. Minimum Inhibitory Concentration (MIC) Assay

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Billen, G.; Aguilera, E.; Einarsson, R.; Garnier, J.; Gingrich, S.; Grizzetti, B.; Lassaletta, L.; Le Noë, J.; Sanz-Cobena, A. Reshaping the European Agro-Food System and Closing Its Nitrogen Cycle: The Potential of Combining Dietary Change, Agroecology, and Circularity. One Earth 2021, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, A.S.; De Lencastre, H.; Garau, J.; Kluytmans, J.; Malhotra-Kumar, S.; Peschel, A.; Harbarth, S. Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus Aureus. Nature Reviews Disease Primers 2018 4:1 2018, 4, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahmad, N.; Joji, R.M.; Shahid, M. Evolution and Implementation of One Health to Control the Dissemination of Antibiotic-Resistant Bacteria and Resistance Genes: A Review. Front Cell Infect Microbiol 2023, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marshall, B.M.; Levy, S.B. Food Animals and Antimicrobials: Impacts on Human Health. Clin Microbiol Rev 2011, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Boeckel, T.P.; Brower, C.; Gilbert, M.; Grenfell, B.T.; Levin, S.A.; Robinson, T.P.; Teillant, A.; Laxminarayan, R. Global Trends in Antimicrobial Use in Food Animals. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2015, 112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scalbert, A.; Johnson, I.T.; Saltmarsh, M. Polyphenols: Antioxidants and Beyond. Am J Clin Nutr 2005, 81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Lafuente, A.; Guillamón, E.; Villares, A.; Rostagno, M.A.; Martínez, J.A. Flavonoids as Anti-Inflammatory Agents: Implications in Cancer and Cardiovascular Disease. Inflammation Research 2009, 58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Walsh, D.J.; Livinghouse, T.; Goeres, D.M.; Mettler, M.; Stewart, P.S. Antimicrobial Activity of Naturally Occurring Phenols and Derivatives Against Biofilm and Planktonic Bacteria. Front Chem 2019, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amalraj, A.; Pius, A.; Gopi, S.; Gopi, S. Biological Activities of Curcuminoids, Other Biomolecules from Turmeric and Their Derivatives – A Review. J Tradit Complement Med 2017, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villanueva, X.; Zhen, L.; Ares, J.N.; Vackier, T.; Lange, H.; Crestini, C.; Steenackers, H.P. Effect of Chemical Modifications of Tannins on Their Antimicrobial and Antibiofilm Effect against Gram-Negative and Gram-Positive Bacteria. Front Microbiol 2023, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manso, T.; Lores, M.; de Miguel, T. Antimicrobial Activity of Polyphenols and Natural Polyphenolic Extracts on Clinical Isolates. Antibiotics 2022, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Z.; Jiang, H.; Xu, C.; Gu, L. A Review: Using Nanoparticles to Enhance Absorption and Bioavailability of Phenolic Phytochemicals. Food Hydrocoll 2015, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Dong, S.; Wang, X.; Xu, H.; Yang, X.; Wu, S.; Jiang, X.; Kan, M.; Xu, C. Research Progress of Polyphenols in Nanoformulations for Antibacterial Application. Mater Today Bio 2023, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Turuvekere Vittala Murthy, N.; Agrahari, V.; Chauhan, H. Polyphenols against Infectious Diseases: Controlled Release Nano-Formulations. European Journal of Pharmaceutics and Biopharmaceutics 2021, 161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Renzetti, A.; Betts, J.W.; Fukumoto, K.; Rutherford, R.N. Antibacterial Green Tea Catechins from a Molecular Perspective: Mechanisms of Action and Structure-Activity Relationships. Food Funct 2020, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, W.; Fatehi, P. Lignin for Polymer and Nanoparticle Production: Current Status and Challenges. Canadian Journal of Chemical Engineering 2019, 97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munir, M.T.; Pailhories, H.; Eveillard, M.; Irle, M.; Aviat, F.; Dubreil, L.; Federighi, M.; Belloncle, C. Testing the Antimicrobial Characteristics of Wood Materials: A Review of Methods. Antibiotics 2020, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, V.; Agrawal, Y. Nanosuspension: An Approach to Enhance Solubility of Drugs. J Adv Pharm Technol Res 2011, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ariga, K.; Hill, J.P.; Lee, M. V.; Vinu, A.; Charvet, R.; Acharya, S. Challenges and Breakthroughs in Recent Research on Self-Assembly. In Proceedings of the Science and Technology of Advanced Materials; 2008; Vol. 9.

- Thummajitsakul, S.; Samaikam, S.; Tacha, S.; Silprasit, K. Study on FTIR Spectroscopy, Total Phenolic Content, Antioxidant Activity and Anti-Amylase Activity of Extracts and Different Tea Forms of Garcinia Schomburgkiana Leaves. LWT 2020, 134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stuart, B.H. Infrared Spectroscopy: Fundamentals and Applications. Infrared Spectroscopy: Fundamentals and Applications. [CrossRef]

- Pantoja-Castroa, M. a.; González-rodríGuez, H. Study by Infrared Spectroscopy and Thermogravimetric Analysis of Tannins and Tannic Acid. Rev Latinoam Quim 2011, 39. [Google Scholar]

- Ricci, A.; Olejar, K.J.; Parpinello, G.P.; Kilmartin, P.A.; Versari, A. Application of Fourier Transform Infrared (FTIR) Spectroscopy in the Characterization of Tannins. Appl Spectrosc Rev 2015, 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silverstein, R.M.; Webster, F.X.; Kiemle, D.J. Spectrometric Identification of Organic Compounds 7ed 2005 - Silverstein, Webster & Kiemle.Pdf. Microchemical Journal 2005, 21. [Google Scholar]

- Tondi, G.; Petutschnigg, A. Middle Infrared (ATR FT-MIR) Characterization of Industrial Tannin Extracts. Ind Crops Prod 2015, 65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herdlevær, K.M.; Løhre, C.; Nodland, E.; Barth, T. Comparison of Calibration Models for Rapid Prediction of Lignin Content in Lignocellulosic Biomass Based on Infrared and Near-Infrared Spectroscopy. Results Chem 2022, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.; Li, R.; Gao, Y.; Zheng, Y.; Liao, L.; Cao, Y.; Li, J.; Zhou, W. Encapsulation of Hydrophobic and Low-Soluble Polyphenols into Nanoliposomes by Ph-Driven Method: Naringenin and Naringin as Model Compounds. Foods 2021, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moccia, F.; Piscitelli, A.; Giovando, S.; Giardina, P.; Panzella, L.; D’ischia, M.; Napolitano, A. Hydrolyzable vs. Condensed Wood Tannins for Bio-Based Antioxidant Coatings: Superior Properties of Quebracho Tannins. Antioxidants 2020, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seong, G.; Yoko, A.; Inoue, R.; Takami, S.; Adschiri, T. Selective Chemical Recovery from Biomass under Hydrothermal Conditions Using Metal Oxide Nanocatalyst. Journal of Supercritical Fluids 2018, 133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kowalska-Krochmal, B.; Dudek-Wicher, R. The Minimum Inhibitory Concentration of Antibiotics: Methods, Interpretation, Clinical Relevance. Pathogens 2021, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balouiri, M.; Sadiki, M.; Ibnsouda, S.K. Methods for in Vitro Evaluating Antimicrobial Activity: A Review. J Pharm Anal 2016, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Ma, J.; Ruan, J.; Zhuang, X. Using Positively Charged Magnetic Nanoparticles to Capture Bacteria at Ultralow Concentration. Nanoscale Res Lett 2019, 14, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, W.W.; Wade, M.M.; Holman, S.C.; Champlin, F.R. Status of Methods for Assessing Bacterial Cell Surface Charge Properties Based on Zeta Potential Measurements. J Microbiol Methods 2001, 43, 153–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salvioni, L.; Galbiati, E.; Collico, V.; Alessio, G.; Avvakumova, S.; Corsi, F.; Tortora, P.; Prosperi, D.; Colombo, M. Negatively Charged Silver Nanoparticles with Potent Antibacterial Activity and Reduced Toxicity for Pharmaceutical Preparations. Int J Nanomedicine 2017, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zadoks, R.N.; Allore, H.G.; Barkema, H.W.; Sampimon, O.C.; Wellenberg, G.J.; Gröhn, Y.T.; Schukken, Y.H. Cow- and Quarter-Level Risk Factors for Streptococcus Uberis and Staphylococcus Aureus Mastitis. J Dairy Sci 2001, 84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grundmann, H.; Aires-de-Sousa, M.; Boyce, J.; Tiemersma, E. Emergence and Resurgence of Meticillin-Resistant Staphylococcus Aureus as a Public-Health Threat. Lancet 2006, 368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rice, J.A.; Carrasco-Medina, L.; Hodgins, D.C.; Shewen, P.E. Mannheimia Haemolytica and Bovine Respiratory Disease. Anim Health Res Rev 2008, 8. [Google Scholar]

- Griffin, D. Bovine Pasteurellosis and Other Bacterial Infections of the Respiratory Tract. Veterinary Clinics of North America - Food Animal Practice 2010, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Confer, A.W. Update on Bacterial Pathogenesis in BRD. Animal health research reviews / Conference of Research Workers in Animal Diseases 2009, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ziagham, A.; Gharibi, D.; Mosallanejad, B.; Avizeh, R. Molecular Characterization of Pasteurella Multocida from Cats and Antibiotic Sensitivity of the Isolates. Vet Med Sci 2024, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dabo, S.M.; Taylor, J.D.; Confer, A.W. Pasteurella Multocida and Bovine Respiratory Disease. Anim Health Res Rev 2008, 8. [Google Scholar]

- Punpanich, W.; Srijuntongsiri, S. Pasteurella (Mannheimia) Haemolytica Septicemia in an Infant: A Case Report. J Infect Dev Ctries 2012, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melchner, A.; van de Berg, S.; Scuda, N.; Feuerstein, A.; Hanczaruk, M.; Schumacher, M.; Straubinger, R.K.; Marosevic, D.; Riehm, J.M. Antimicrobial Resistance in Isolates from Cattle with Bovine Respiratory Disease in Bavaria, Germany. Antibiotics 2021, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Michael, G.B.; Bossé, J.T.; Schwarz, S. Antimicrobial Resistance in Pasteurellaceae of Veterinary Origin. Microbiol Spectr 2018, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Džidić, S.; Šušković, J.; Kos, B. Antibiotic Resistance Mechanisms in Bacteria: Biochemical and Genetic Aspects. Food Technol Biotechnol 2008, 46. [Google Scholar]

- Segura, M.; Aragon, V.; Brockmeier, S.L.; Gebhart, C.; de Greeff, A.; Kerdsin, A.; O’Dea, M.A.; Okura, M.; Saléry, M.; Schultsz, C.; et al. Update on Streptococcus Suis Research and Prevention in the Era of Antimicrobial Restriction: 4thinternationalworkshop on s. Suis. Pathogens 2020, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gottschalk, M.; Xu, J.; Calzas, C.; Segura, M. Streptococcus Suis: A New Emerging or an Old Neglected Zoonotic Pathogen? Future Microbiol 2010, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Apostolakos, I.; Mughini-Gras, L.; Fasolato, L.; Piccirillo, A. Assessing the Occurrence and Transfer Dynamics of ESBL/PAmpC-Producing Escherichia Coli across the Broiler Production Pyramid. PLoS One 2019, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chapa González, C.; González García, L.I.; Burciaga Jurado, L.G.; Carrillo Castillo, A. Bactericidal Activity of Silver Nanoparticles in Drug-Resistant Bacteria. Brazilian Journal of Microbiology 2023, 54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sathiyaraj, S.; Suriyakala, G.; Dhanesh Gandhi, A.; Babujanarthanam, R.; Almaary, K.S.; Chen, T.W.; Kaviyarasu, K. Biosynthesis, Characterization, and Antibacterial Activity of Gold Nanoparticles. J Infect Public Health 2021, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Almeida Roger, J.; Magro, M.; Spagnolo, S.; Bonaiuto, E.; Baratella, D.; Fasolato, L.; Vianello, F. Antimicrobial and Magnetically Removable Tannic Acid Nanocarrier: A Processing Aid for Listeria Monocytogenes Treatment for Food Industry Applications. Food Chem 2018, 267, 430–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Theophel, K.; Schacht, V.J.; Schlüter, M.; Schnell, S.; Stingu, C.S.; Schaumann, R.; Bunge, M. The Importance of Growth Kinetic Analysis in Determining Bacterial Susceptibility against Antibiotics and Silver Nanoparticles. Front Microbiol 2014, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Youssef, F.S.; El-Banna, H.A.; Elzorba, H.Y.; Galal, A.M. Application of Some Nanoparticles in the Field of Veterinary Medicine. Int J Vet Sci Med 2019, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Benzie, I.F.F.; Strain, J.J. The Ferric Reducing Ability of Plasma (FRAP) as a Measure of “Antioxidant Power”: The FRAP Assay. Anal Biochem 1996, 239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singleton, V.L.; Orthofer, R.; Lamuela-Raventós, R.M. Analysis of Total Phenols and Other Oxidation Substrates and Antioxidants by Means of Folin-Ciocalteu Reagent. Methods Enzymol 1999, 299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsai, T.H.; Tsai, T.H.; Chien, Y.C.; Lee, C.W.; Tsai, P.J. In Vitro Antimicrobial Activities against Cariogenic Streptococci and Their Antioxidant Capacities: A Comparative Study of Green Tea versus Different Herbs. Food Chem 2008, 110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Spectral identification | CCA | CCB | CP | TA |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stretching vibrations of the hydroxyl groups -OH | 3300 | 3340 | 3360 | 3350 |

| Symmetric stretching vibrations and antisymmetric -CH- |

2930 | 2935 2850 |

||

| Carbonyl group stretching C=O | 1725 | 1718 | 1701 | |

| Deformation vibrations of the aromatic backbone C-C |

1605 | 1600 1512 |

1590 1510 |

1605 1534 |

| Stretching vibrations of the aromatic backbone C-C | 1445 | 1448 | 1456 | 1443 |

| Stretching vibration of C-O | 1283 1168 |

1305 1175 |

1265 1215 1130 1080 |

1308 1175 1080 |

| Bacteria | Compound | Mean O.D. | Comparator | Mean O.D. | Mean difference | 95% CI | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| lower | upper | |||||||

| S. aureus | CCA | 0.228 | CCB | 0.155 | 0.074 | 0.005 | 0.143 | 0.031 |

| CP | 0.322 | CCA | 0.228 | 0.094 | 0.040 | 0.147 | 0.041 | |

| CP | 0.322 | CCB | 0.155 | 0.167 | 0.106 | 0.229 | 0.014 | |

| M. haemolitica | CCA | 0.255 | CCB | 0.214 | 0.040 | −0.066 | 0.146 | >0.05 |

| CP | 0.223 | CCA | 0.255 | −0.031 | −0.181 | 0.118 | >0.05 | |

| CP | 0.223 | CCB | 0.214 | 0.009 | −0.178 | 0.195 | >0.05 | |

| P. multocida | CCA | 0.410 | CCB | 0.377 | 0.032 | −0.070 | 0.135 | >0.05 |

| CP | 0.258 | CCA | 0.410 | −0.151 | −0.344 | 0.042 | >0.05 | |

| CP | 0.258 | CCB | 0.377 | −0.119 | −0.350 | 0.112 | >0.05 | |

| S. suis | CCA | 0.120 | CCB | 0.229 | −0.109 | −0.222 | 0.004 | >0.05 |

| CP | 0.283 | CCA | 0.120 | 0.163 | 0.079 | 0.247 | 0.036 | |

| CP | 0.283 | CCB | 0.229 | 0.054 | −0.117 | 0.224 | >0.05 | |

| S. typhimurium | CCA | 0.593 | CCB | 0.656 | −0.063 | −0.203 | 0.076 | >0.05 |

| CP | 0.694 | CCA | 0.593 | 0.101 | 0.005 | 0.196 | >0.05 | |

| CP | 0.694 | CCB | 0.656 | 0.037 | −0.140 | 0.215 | >0.05 | |

| E. coli | CCA | 1.275 | CCB | 1.118 | 0.157 | −0.024 | 0.339 | >0.05 |

| CP | 0.612 | CCA | 1.275 | −0.662 | −0.343 | −0.982 | 0.028 | |

| CP | 0.612 | CCB | 1.118 | −0.505 | −0.342 | −0.668 | 0.031 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).