UTF8gbsn

1. Introduction

In recent years, with the development of information technology, traditional information retrieval methods can no longer meet users’ query needs for knowledge in specific fields, which makes the question-answering system based on natural language processing technology an important tool for solving such problems. As a typical question-answering system, the FAQ system provides users with fast and accurate information services by collecting and retriving frequently asked questions and answers in a specific field. The core task of the FAQ system is sentence similarity measuring which is to find semantic symmetry between two sentences and retrieves questions similar to the user queries from the knowledge base.

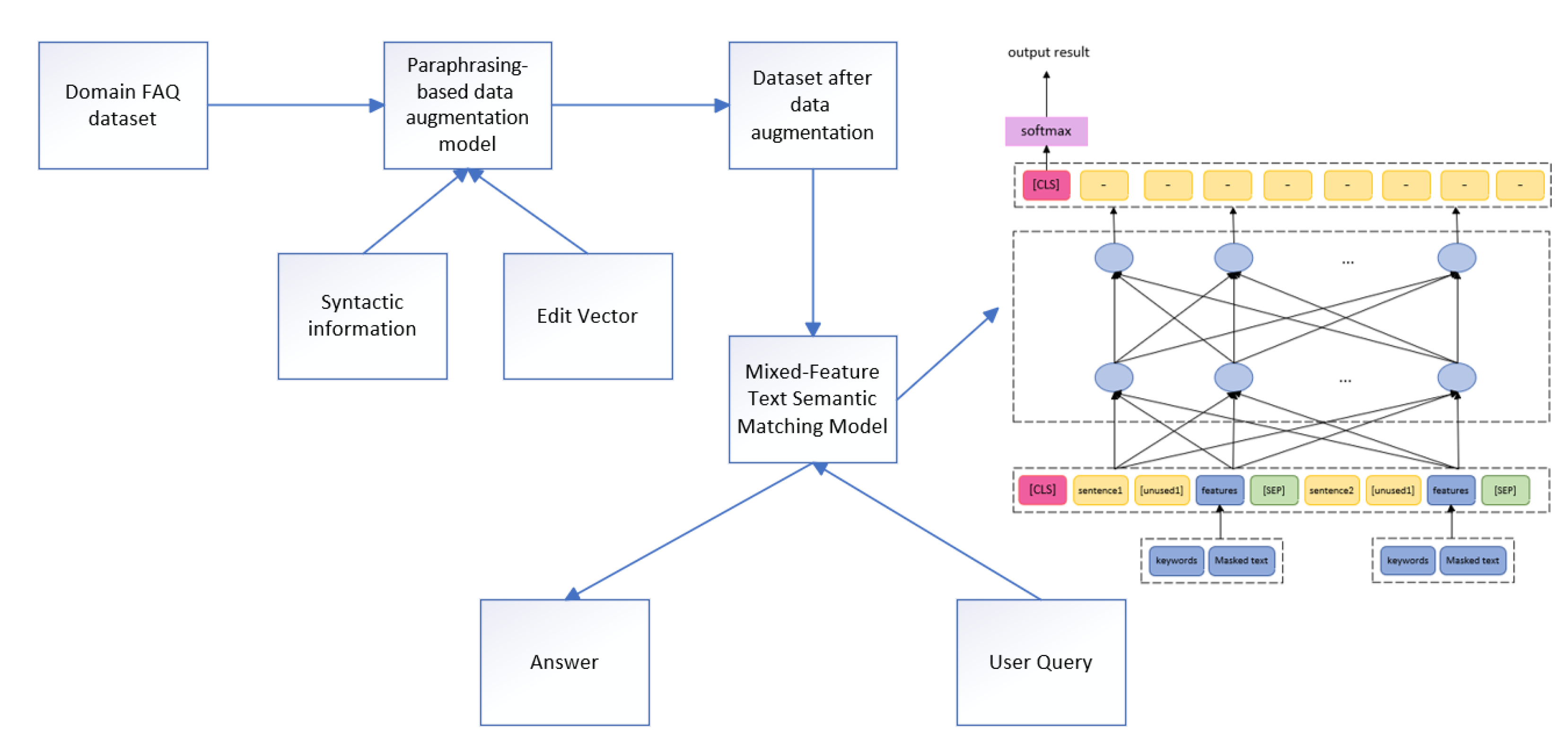

To address the challenges of insufficient training data and limited domain-specific understanding in low-resource FAQs, this paper proposes a general framework PDAM-FAQ to solve these issues, in which a paraphrasing-based data augmentation model was first used to enhance FAQ dataset and a mixed-feature semantic matching model based on SimBERT was proposed to match user queries to FAQs. The main contributions of this paper include:

(1) This paper proposes a paraphrasing-based data augmentation model based on the fusion of syntactic information and edit vectors. It can learn the semantic information features of text from a large amount of training data, use template sentences to guide the syntactic structure features of the generated paraphrase sentences, and construct edit vectors to enhance the pre-trained model to learn the mapping relationship between the original sentence and the paraphrase sentence.

(2) This paper proposes a mixed-feature semantic matching model based on SimBERT. The model enhances the learning of key semantic information by extracting keyword features from the text and replacing these keywords with special characters to construct intent features. By integrating both keyword and intent features into the semantic model, the approach significantly improves the model’s ability to capture essential semantic information.

2. Related Works

2.1. Paraphrasing-Based Data Augmentation

Data augmentation (DA) synthesizes training data to combat data scarcity, maintaining consistency with the original data distribution. Effective DA methods ensure similar semantics, crucial for tasks such as machine translation and text classification. Paraphrasing-based methods within DA generate data with minimal semantic changes but diverse syntax, bolstering dataset diversity and robustness.

Zhang et al. [

1] pioneered thesaurus-based DA, using a WordNet-derived thesaurus to replace words in sentences. Although thesaurus-based methods are easy to use, it may lead to limitations in the scope and part of speech of augmented words. Wang et al. [

2] extended this approach using word embeddings and frame embeddings, addressing limitations of replacement range and part-of-speech constraints, and achieved higher replacement hit rate and more comprehensive replacement range. However, such methods still cannot solve the ambiguity problem. With pretrained models like BERT and RoBERTa, masked language models predict masked words to alleviate ambiguity. Jiao et al. [

3] mask multiple words and generate new sentences, although this method takes contextual semantics into account and alleviates the ambiguity problem, excessive substitution may change the semantics. Coulombe et al. [

4] use regular expressions to transform sentence forms without changing semantics, but this method still suffers from low coverage and limited variation. Xie et al. [

5] perform back-translation on each sentence and obtain their paraphrases. Back-Translation has a wide range of applications and can ensure that the semantics remain unchanged. However, due to the fixed machine, it has poor controllability and limited diversity. Hou et al. [

6] introduce a Seq2Seq model using delexicalized inputs and diverse ranks to generate new utterances. Model-based data augmentation methods are highly applicable, but the model requires a large amount of training data and is difficult to train.

Controllable paraphrasing-based DA methods guide the creation of paraphrases with different syntactic structures through various syntactic factors. Kazemnejad et al. [

7] proposed the Retriever-Editor model, which uses edit vectors to control paraphrase generation, thereby achieving diversity in paraphrases. Iyyer et al. [

8] introduced the SCPN model, which uses the linearized syntactic tree of reference paraphrase sentences as a control condition to generate diverse syntactic paraphrases. Chen et al. [

9] developed the CGEN model, which extracts syntactic information from template sentences and differentiates semantic and syntactic information through multi-task learning. Both the SCPN and CGEN models rely on control conditions, and truncation of the syntactic parse tree can result in incomplete paraphrases. Kumar et al. [

10] proposed the SGCP model, which uses hierarchical syntactic structures to control paraphrasing and improve diversity. Sun et al. [

11] introduced the AESOP model, which incorporates syntactic information from retrieved template sentences into the pre-trained model to control paraphrasing. Yang et al. [

12] suggested using two encoders to separately encode the semantic features of input sentences and the stylistic features of template sentences, and proposed a content contrastive loss module to distinguish between semantics and style. Liu et al. [

13] proposed transferring knowledge from bilingual paraphrasing to monolingual paraphrase generation, using sentences from bilingual parallel corpora as syntactic templates. Yang et al. [

14] introduced the GCPG framework, which generates paraphrase sentences using lexical and syntactic conditions, avoiding direct copying of words from the templates.

2.2. Semantic Matching

Semantic matching is a crucial task in natural language processing, with applications in question-answering systems, document retrieval, sentence paraphrasing, and dialogue systems. The key is to maximize the effectiveness of text semantic matching based on specific tasks. Traditional methods primarily addressed lexical-level matching. With the development of neural networks and deep learning, semantic matching models have transitioned from traditional methods to deep learning models. These models can automatically extract features, better focus on contextual semantic information, and are categorized into representation-based and interaction-based models.

Representation-based text matching models: In 2013, Huang et al. [

15] proposed the DSSM model, which used a bag-of-words model to construct word vectors but overlooked the sequential relationships between words. To address the issue of DSSM losing contextual information, Shen et al. [

16] from Microsoft Research introduced the CDSSM model in 2014. This model used convolutional neural networks to capture contextual features through a sliding window, yet it still struggled to capture long-distance dependencies. Subsequently, Palangi et al. [

17] replaced the fully connected layer in DSSM with an LSTM network, demonstrating that LSTM can effectively capture long-distance dependencies. Wan et al. [

18] proposed the MV-LSTM model, which utilized a bidirectional LSTM network to generate position-aware sentence representations, focusing on significant local information. Huawei’s Noah’s Ark Lab developed the ARC-I model [

19], which employed convolutional neural networks to extract features from two sentences and calculated sentence similarity through a multilayer perceptron.

Interaction-based semantic matching: Interaction-based semantic matching involves allowing two segments of text to interact from the beginning, focusing on the features of words and phrases and their relative positions. This approach learns global features from local features to improve matching accuracy. In 2014, Hu et al. [

19] proposed the ARC-II interaction-based model, which performed convolution and pooling operations through a two-dimensional matrix to comprehensively analyze the semantic matching degree between sentences. The MatchPyramid model [

20] generated an interaction matrix from the interaction of word vector sequences, transforming text matching into an image recognition problem, preserving word order information, and extracting rich matching patterns. Chen et al. [

21] introduced the Tree-LSTM neural network and proposed the ESIM model, which includes an input layer, local inference modeling, and combination inference, focusing on interaction and dependency between data. The DeepRank model [

22], similar to MatchPyramid[

20], uses an interaction matrix where elements represent the contextual similarity of two words in the text.

3. Methodology

3.1. Overview of the PDAM-FAQ Framework

To address the issues of insufficient training data and limited domain-specific semantic understanding in FAQ question-answering systems, this paper proposes a paraphrasing-based data augmentation model that integrates syntactic information and edit vectors. First, a rule-based approach is used to retrieve template sentences corresponding to the original sentences from the corpus. Next, these template sentences undergo part-of-speech tagging, and special characters are used to mask words with relevant parts of speech, such as nouns, verbs, adjectives, and adverbs. Finally, Glove word vectors are used to construct edit vectors between the original and reference paraphrase sentences. These edit vectors are incorporated into the encoding layer of a pre-trained model to enhance the model’s learning of the differences between the original and reference paraphrase sentences. The augmented dataset is then used for training, validating, and testing a semantic matching model with hybrid features. The mixed-feature semantic matching model proposed in this paper, based on SimBERT, extracts keyword features from the text. Special characters replace the keywords in the text to construct intention features. The user question, keyword features, and intention features are concatenated as the model’s input.

Figure 1.

PDAM-FAQ framework

Figure 1.

PDAM-FAQ framework

3.2. Paraphrasing-based Data Augmentation Fusing Syntactic Information and Edit Vectors

3.2.1. Task Overview

Let denote a dataset,where denotes the input of the original sentence, and denotes a template sentence, and Indicates a reference to a rephrased sentence. Given an original sentence x and a template sentence e ,The goal is to learn a paraphrasing-based model for generating paraphrase sentences y and can find the maximized parameter set of the model .Where refers to the model parameter that outputs the maximum likelihood conditional value.

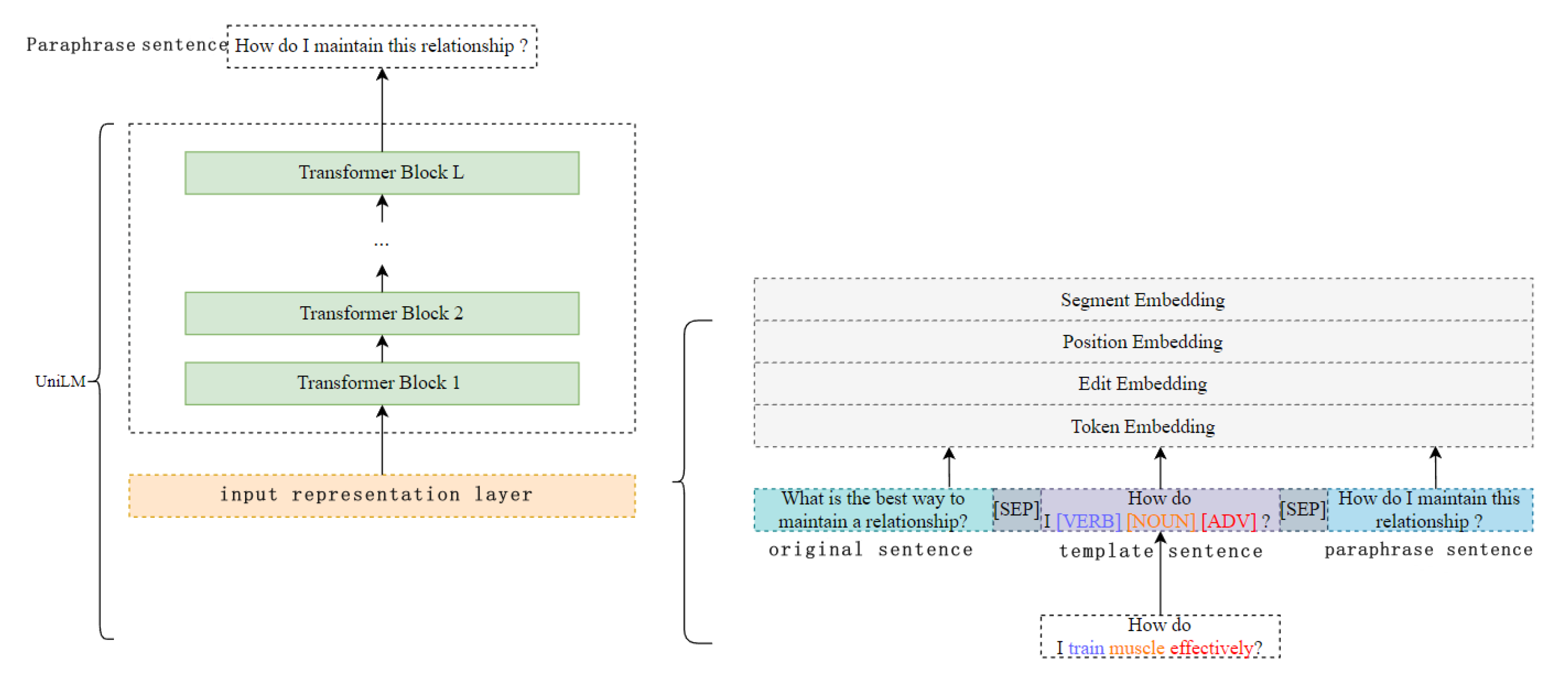

Figure 2 illustrates the framework of the proposed model. In the input layer of the pre-trained model, edit vectors are added. The input vectors are represented using token vectors, edit vectors, segment vectors, and position vectors. Edit vectors focus on the semantic information of important words between the original sentence and the paraphrase sentence. During the decoding phase, the model uses a beam search strategy to generate the corresponding paraphrase sentences.

3.2.2. Selection and Construction of Syntactic Templates

Template sentences are only used in the test set and validation set of the existing paraphrasing dataset. The model directly uses the reference paraphrase sentence to construct the syntactic template during the training phase, while the inference process requires pre-retrieval of the template sentence and then the same method is used to construct the syntactic template. The process of selecting and constructing the syntactic template is shown in

Figure 3, which is mainly divided into three steps: (1) Retrieve the template sentence from the training corpus; (2) Perform part-of-speech analysis on the words in the template sentence; (3) Use special tags to replace the words of the relevant part-of-speech.

Referring to the method of constructing template sentences by Kumar et al. [

10], this paper uses the training corpus as the retrieval library and adopts a rule-based method to retrieve the template sentences, which can ensure that the grammatical structure is consistent with the retrieval sentence. The retrieval rules of the template sentences are as follows:

(1) Neither the original sentence nor the reference paraphrase sentence can be used as a candidate template sentence;

(2) The length difference between the candidate template sentence and the reference paraphrase sentence is less than or equal to 2;

(3) The BLEU [

23] value of the candidate template sentence and the reference paraphrase sentence is less than 0.6, which is done to avoid the candidate template sentence and the reference paraphrase sentence being highly aligned;

(4) Calculate the Translation Edit Rate (TER) of the candidate template sentence and the reference paraphrase sentence and select the candidate template sentence with the smallest TER value as the final template sentence. The reason for selecting the sentence with the smallest TER value is to ensure that the candidate template sentence can have a similar syntactic structure with the reference paraphrase sentence.

When retrieving template sentences, the above four rules need to be satisfied at the same time. However, some reference paraphrases cannot satisfy the above rules at the same time when retrieving template sentences, which results in the situation where the template sentences cannot be retrieved. This paper takes this problem into consideration in practical applications. Based on the method of retrieving template sentences proposed by Kumar et al. [

10], this paper adopts the rollback method from the second rule to solve the problem of not retrieving template sentences. When there is no template sentence that meets the conditions when executing the next rule, it rolls back to the previous rule to select the template sentence. This method can ensure that the corresponding template sentence can be retrieved for each original sentence. If the retrieved complete template sentence is directly input into the model, the words in the template sentence that are inconsistent with the original sentence in semantics will affect the model’s learning of the semantic information in the original sentence. This paper draws on the method of constructing templates by Bui et al. [

24]. First, the part-of-speech tagging tool is used to analyze the part-of-speech of each word in the template sentence. Then, all the words corresponding to adjectives, verbs, nouns and adverbs in the template sentence are replaced with the corresponding part-of-speech tags. At the same time, the part-of-speech tags are added as special characters to the vocabulary of the pre-trained model. The special characters corresponding to adjectives, nouns, verbs and adverbs are "[ADJ]", "[NOUN]", "[VERB]" and "[ADV]" respectively. The granularity of identifying part-of-speech tags in the part-of-speech tagging tool is relatively coarse. For example, interrogative adverbs and adverbs are all identified as adverbs. Considering the characteristics of the actual corpus, interrogative words in the template sentence are retained, such as "How", "What" and other words. This method is applicable to template construction in both model training and model inference stages.

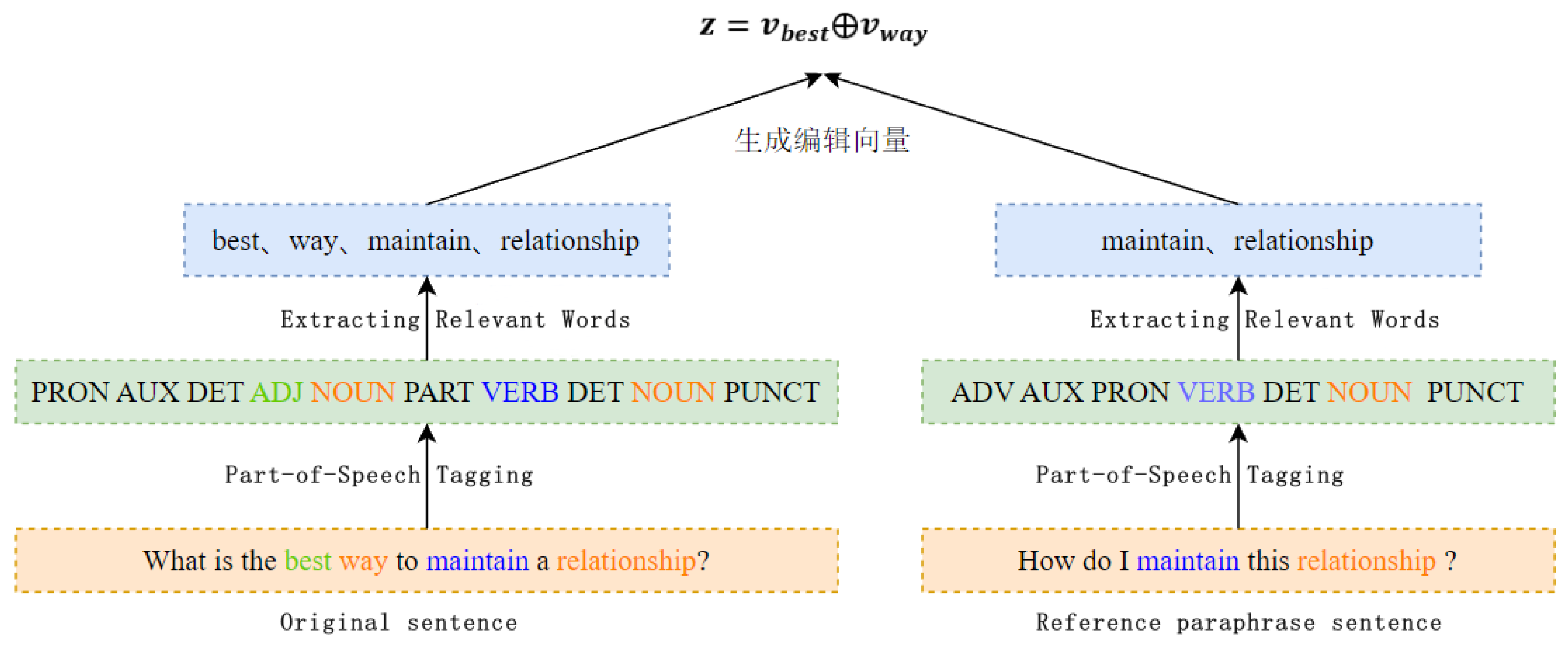

3.2.3. Extraction of Edit Vectors

In

Section 3.2.2, adjectives, verbs, adverbs, and nouns in the retrieved template sentences are replaced with special characters. This only tells the model to refer to the syntactic structure of the template sentence. However, in order to fully capture the semantic information in the original sentence and the impact of the editing operation on the sentence transformation, this paper proposes an edit vector z to enhance the model to learn the semantic information of different words between the original sentence and the reference paraphrase. This paper uses the 300-dimensional Glove word vector [

25] to represent the edit vector z. Given an original sentence x and a template sentence y, the generated edit vector z is used to infer the possibility of mapping the original sentence x to the reference paraphrase y, concentrating the probability on a few but important words.

Figure 4 shows an example diagram of the method for extracting the edit vector.

In this paper, along the lines of Guu [

26] and others,we adopt the word vectors of different words in the original sentence

x and the reference paraphrase sentence

y as the edit vectors from the original sentence

x to the reference paraphrase sentence

y . From the original sentence

x to the reference paraphrase

y can be realized through word insertion and deletion operations, in this paper, we use the word vectors of inserted and deleted words and the edit vector

z that represents the edit vector between the original sentence

x and the reference paraphrase sentence

y , where only words with related lexical properties, such as nouns, verbs, adjectives and adverbs, are considered. Formally, define

as the set added to

y and

as the set of words deleted from

y . Use the following formula to represent the difference between

x and

y:

where

denotes the word vector of the word

w and ⊕ denotes the vector splice.

The purpose of the maximum likelihood function is to use the known distribution of training set data to infer the most likely result parameter value, and this goal is exactly in line with the idea of

generating a model in this paper, generating corresponding paraphrases based on known sentences. In the training stage, the objective function of the model is:

Among them,

t is the current time step,

T is the number of generated words,

is the parameter of the UniLM model, and an optimization goal is proposed:

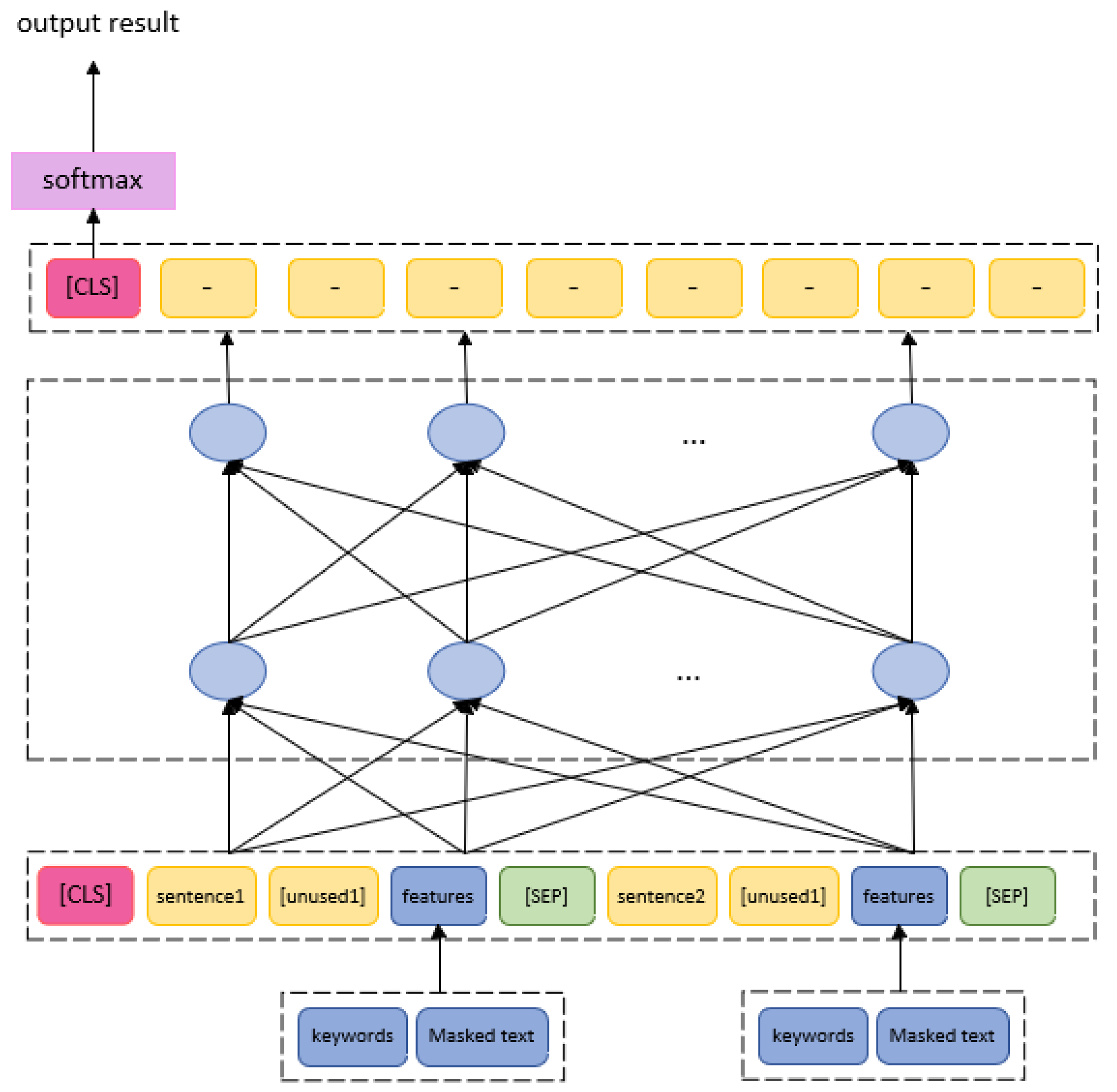

3.3. Mixed-Feature Semantic Matching Model Based on SimBERT

Since there are a large number of professional terms in different specific fields, some of which are composed of multiple nouns into a new noun, but the SimBERT pre-training model uses the WordPiece method to segment sentences, which makes it more difficult for the model to understand the deep semantics of the text. In order to enable the model to focus on the semantic information of specific words and the intention of user questions, this paper proposes a mixed-feature semantic matching model based on SimBERT, which is divided into keyword features and intent features. Keywords are representative and important words extracted from a text, which can indicate the theme of the text to a certain extent. Adding keyword features can reduce the problem of semantic focus of the model when retrieving similar questions.

Let

denote a dataset ,where

denotes the first sentence, and

denotes the second sentence.

is the similarity label.

. Given the sentence and the sentence ,the goal is to learn a text matching model for determining whether sentence

x and sentence

y are similar. A mixed-feature semantic matching model based on SimBERT is illustrated in

Figure 5, which mainly contains a text input layer, a model layer and a result output layer:

(1)Input Layer: the input layer is mainly used to splice different features, including keywords and Masked text. Below are the steps to build the input layer:

a. Keywords: Use keyword identification tools to extract keywords from the first and second sentences respectively;

b. Masked text: Use the "[MASK]" special character to replace the keywords in the sentence. For example, if the sentence is "What is the basic principle of ship anti-sinking?", the keywords are "anti-sinking, basic principle", and the masked text is "What is the [MASK] of ship [MASK]?" The keywords here get the two words with the highest scores;

c. Concatenating Input Text: Use the special token “[unused1]” from the pretrained model’s vocabulary to connect sentences, keywords, and masked text, forming the structure “sentence[unused1] keyword|masked sentence”. Between the first and second sentences, use the “[SEP]” separator to concatenate the two text segments, indicating two pieces of input text. Before the first sentence, add the special token “[CLS]”. This results in the sequence “[CLS]sentence1[unused1]keyword|masked sentence[SEP]sentence2 [unused1]keyword|masked sentence" as the input for the pretrained model. After inputting into the model, obtain the token vectors, position vectors, and segment vectors of the input text, and concatenate them into a single vector, which represents the input text’s embedding.

(2)Model Layer: In natural language processing, the length of input sequences can be very long, and different parts of the sequence may have varying levels of importance. The attention mechanism improves the model’s expressive power by dynamically assigning different weights to different parts of the input, without increasing the number of parameters. Self-attention mechanism is used to capture internal information within the sequence. It treats each position in the input sequence as a query, calculates the attention scores with other positions, and then uses these attention scores as corresponding weights. By performing a weighted sum over all positions, it obtains the representation for each position. The computation process of the self-attention mechanism is as follows:

a. Calculate the Q, K and V vectors: Denote N input messages by , the input encoder obtains the vectors and performs linear transformation to obtain Query vector, Key vector and Value vector, which are all word vectors obtained by multiplying the word vectors with the 3 parameter matrices respectively:

where

,

and

are the parameter matrices.

b. Calculate the Attention score: it is obtained from the dot product of the Query vectors corresponding to each word and the Key vectors of each word in other positions:

c. In order for the network to seek gradient stability during backpropagation, the Attention scores are divided by

, with

being the dimension of the key vector, and these scores are then subjected to a normalisation operation by softmax to ensure that these scores are equal to 1 when added together:

d. Finally, the scores for each word vector are multiplied with the corresponding Value vectors, and the larger values after the multiplication are where the model needs to pay more attention:

(3)Output layer: softmax function is added at the end of the model for classification of similar results, the ‘[CLS]’ vector output from the model represents the vector of sentences, and the category probability vector can be obtained through the softmax function, and the one with the largest prediction probability is finally selected as the predicted category.

4. Experiment

Experiments are conducted respectively on the paraphrasing-based data augmentation model, mixed-feature semantic matching model and their comprehensive application in a low-resource domain-specific FAQ.

4.1. Experimental setup

4.1.1. Setup of Paraphrasing-based Data Augmentation Module

(1)Dataset

Two datasets including LCQMC[

27] and BQ corpus[

28] are used and specific description of these two dataset are listed in

Table 1 .

(2)Hyperparameter settings

We set batch size to 64, Dropout rate to 0.1, and learning rate to 1e-5 and Adam optimizer[

29] is used in the model.

(3)Evaluation metrics

1) Metrics for the degree of alignment between the generated paraphrase sentence and the reference paraphrase sentence including BLEU, METEOR, ROUGE-1, and ROUGE-2 are used to measure the degree of overlap between the generated paraphrase sentence and the reference paraphrase sentence.

2)Metrics for syntactic control in paraphrase generation: The tree-edit distance (TED-R)[

30] between the syntactic parse trees of the generated paraphrase sentence and the reference paraphrase sentence, and the tree-edit distance (TED-E) between the syntactic parse trees of the generated paraphrase sentence and the template sentence. A smaller TED value indicates higher syntactic similarity.

(4)Baselines

Similar to Chen et al [

9], we use the original sentence and the template sentence as the generated paraphrase sentences respectively, and calculate the values of following two indexes:

1) Source-as-Output: Directly use the original sentence as the generated paraphrase sentence.

2)Exemplar-as-Output: Use the retrieved template sentence as the generated paraphrase sentence.

We also compare the paraphrasing module with (1) SCPN[

8]which employs a parse generator to output the full linearized parse tree as the style by inputting a parse template; (2) SGCP[

25] which extracts the style information directly ; (3)CGEN[

9], an approach based on variational inference.

4.1.2. Setup of Semantic Matching Module

(1)Dataset

We conduct experiments on two benchmark datasets, namely QQP-Pos[

10] and ParaNMT-small[

10]. QQP-Pos consists of 130k training, 3k testing and 3k validation quora question pairs. ParaNMT-small is a subset of ParaNMT-50M[

31] containing over 500K training, and 1.3K manually labeled datasets, and is divided into 0.8K testing and 0.5K validation.

(2)Hyperparameter settings

We set a batch size of 64, a dropout rate of 0.1, and a learning rate of 2e-5 during the training phase. The Adam optimizer is used.

(3)Evaluation metrics

Accuracy, precision, recall, and F1 are used as evaluation metrics in the experiments.

(4)Baselines

In this paper, we compare several representative text matching models, including DSSM[

15], CDSSM[

16], MatchPyramid[

20], ESIM[

21], BERT[

32], and SimBERT[

33]. These models are selected from various categories: representation-based, interaction-based, attention mechanism-based, and pre-trained model-based methods. Additionally, the parameters of the baseline models differ from those in the original papers, and fine-tuning has been conducted to optimize the models’ performance.

4.1.3. Setup of Low-Resource FAQs

Compared to modern industries, the shipbuilding domain still lags in terms of digitization and informatization, with relatively scarce digital resources. To enhance the efficiency of scientific research and engineering personnel in this field, it is crucial to develop an intelligent FAQ system. Such a system would enable quick and accurate information retrieval, significantly improving their work efficiency.

This paper first employs web crawlers to gather questions and replies related to hydrodynamics and structural safety in shipbuilding from users on technical forums such as "Longde Ship People"[

34] and "Technical Neighbors"[

35]. A FAQ dataset named ShipFAQ, containing 12,179 Q&A pairs, was constructed.

Table 2 shows examples of the constructed Q&A pairs.

4.2. Experimental Results and Analysis

4.2.1. Evaluation of Paraphrasing-based Data Augmentation

(1) Comparative experiments results and analysis

The results of the comparison experiment are shown in

Table 3, our proposed paraphrasing method significantly outperforms other baseline models on the BLEU and METEOR metrics, but does not show good performance on the ROUGE and TED metrics. And it was found that the model was ineffective in paraphrasing for long texts, which resulted in generating paraphrase sentences with syntactic structures that were less similar to the template sentences, resulting in high values of the TED metrics. The provision of template sentences better guided the results of paraphrasing for short text, which was improved in both the ROUGE and BLEU metrics, with the higher the overlap between the generated paraphrase sentences and the reference paraphrase sentences, the more accurate the generated paraphrase sentence was. Since the METEOR metric takes into account the effects of synonyms, word deformation, and sentence fluency, it is found in the results of the QQP-Pos test set that the generated paraphrase sentences contain a large number of synonyms with the same semantics as the original sentence, which also indicates that enhancing the model by editing the vector has a good effect on learning the difference between the original sentence and the reference paraphrase sentence.

(2)Ablation experiment

1)Pre-training model selection

The selected pre-training models are as follows: a. Transformer: Sequence-to-sequence model consisting of encoder and decoder; b. BERT: Using special masked language models to avoid the limitations of unidirectional language models; c. BART: A generative pre-trained model consisting of the dual encoder of BERT and the left-to-right decoder of GPT shows good performance on the text generation task; d. UniLM[

36]: The use of three special masks for the pre-training objectives allows the models to support both natural language understanding and natural language generation tasks. The pre-training models mentioned above all use the base version (BASE) and the comparison results of the different models are shown in

Table 4.

2)Impact verification of Syntactic Information and Edit Vectors UniLM was selected as the baseline pre-trained model, and several experiments were conducted on QQP-Pos dataset. As shown in

Table 5 , the effect of embedding the edit vector into the UniLM model is not obvious. This is because the word vector of each word in the pre-trained model only captures the semantic information of the smallest granularity, and cannot learn the coarse-grained semantic information and the syntactic structure information in the sentence.

4.2.2. Evaluation of Semantic Matching

(1)Comparative experiments results and analysis

Comparative experiments are carried out on LCQMC and BQ datasets, and the results of the experimental comparisons are shown in

Table 6. Due to the introduction of convolutional neural network in the CDSSM model to extract the features of the text, compared with the DSSM model, it is more capable of capturing the local features of the text. In both datasets, the pre-training model outperforms the representation-based, matching-based model due to the fact that the pre-training model learns deep semantic information in the text, while the attention mechanism in the pre-training model is more capable of obtaining semantic information between words in a sentence. Lastly, Since the SimBERT model is obtained by fine-tuning on the similar sentence task, the SimBERT-based mixed-feature semantic matching model proposed in this paper is better than the SimBERT and BERT baseline models.

4.2.3. Evaluation of Low-resource FAQ

The proposed paraphrasing model is utilized to generate paraphrase sentences for each question, the generated sentences with top2 TER values are selected to build new Q&A pairs. A new FAQ dataset named PDA-ShipFAQ is constructed by paraphrasing-based data augmentation, and the training, validation and test sets are divided according to the ratio of 8:1:1.

Table 7 shows the comparison of the two datasets.

In order to verify the effect of different features on the model, this paper conducts a comparison experiment and the results are shown in

Table 8 . The model incorporating multiple features outperforms the results of the model with other single features in terms of accuracy, recall and F1 value metrics. It can be seen that adding keyword features and intent features is effective in improving the model training effect, which proves the effectiveness of the proposed method in this paper.

There are a large number of professional words in the sentences in the shipbuilding domain FAQs, and most of the professional words are the key words in the sentences. These key words in the sentences are masked to construct the intent features, the model not only learns the information about the key semantics in the sentences, but also learns the intent in the sentences, and the method of mixing the features enhances the model’s generalization ability.

In order to test the impact of data enhancement on the performance of FAQs, this paper uses the best model SimBERT+Keyword+Maskded Text in the above experiments as the base model, respectively on the original FAQ data set ShipFAQ and the data set PDA-ShipFAQ after data augmentation. The experimental results in

Table 9 showed that after data enhancement, both recall and precision values were improved, especially the recall value.

We attribute this to the fact that the proposed paraphrasing-based data augmentation models generate augmented data with limited semantic differences from the original data, due to the restrained changes made to the sentences. The augmented data convey very similar information to the original form, which plays an important role in improving precision and recall. However, since the negative FAQs were not enhanced, the accuracy dropped slightly.

5. Conclusion

This paper addresses common issues in FAQ systems, such as insufficient training data and limited domain-specific semantic understanding, proposing two innovative methods to enhance FAQ performance. Firstly, a paraphrasing method is introduced, which integrates syntactic information and edit vectors. This method retrieves template sentences from a corpus, masks relevant words while maintaining syntactic structure, and constructs edit vectors between original sentences and paraphrase sentences. This enhances pre-trained models’ ability to learn sentence variations. Experimental results demonstrate significant improvements in automatic and human evaluation metrics on the Quora and ParaNMT-small datasets.

Secondly, the paper proposes a mixed-feature semantic matching model based on SimBERT. This model extracts text keyword features, replaces keywords with special characters to construct intent features, and concatenates user queries with these hybrid features as model inputs. Experimental validation on the LCQMC and BQ public datasets shows that this model outperforms baseline models across multiple evaluation metrics. Lastly, the proposed methods are validated in a domain-specific FAQ application. Experimental results indicate that the proposed PDAM-FAQ framework effectively enhances the performance of domain-specific FAQ systems.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, D.W.; methodology, D.W., L.W., K.T., and Q.B.; software, Y.D., S.W., and B.H.; validation, L.W., K.T., and Q.B.; formal analysis, S.W., and B.H.; investigation, D.W., Y.D., S.W., and B.H.; resources, D.W., S.W., and B.H.; data curation, D.W., and L.W.; writing—original draft preparation, D.W.; writing—review and editing, L.W., K.T., and Q.B.; supervision, Y.D., S.W., and B.H.; project administration, D.W., S.W., and B.H.; funding acquisition, D.W. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by National Natural Science Foundation of China (No.61702234) and Open Fund for Innovative Research on Ship Overall Performance (No.25422217).

Data Availability Statement

Dataset available on request from the authors.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Zhang, X.; Zhao, J.; LeCun, Y. Character-level convolutional networks for text classification. Advances in neural information processing systems 2015, 28.

- Wang, W.Y.; Yang, D. That’s so annoying!!!: A lexical and frame-semantic embedding based data augmentation approach to automatic categorization of annoying behaviors using# petpeeve tweets. Proceedings of the 2015 conference on empirical methods in natural language processing, 2015, pp. 2557–2563.

- Jiao, X.; Yin, Y.; Shang, L.; Jiang, X.; Chen, X.; Li, L.; Wang, F.; Liu, Q. Tinybert: Distilling bert for natural language understanding. arXiv preprint arXiv:1909.10351 2019.

- Coulombe, C. Text data augmentation made simple by leveraging nlp cloud apis. arXiv preprint arXiv:1812.04718 2018.

- Xie, Q.; Dai, Z.; Hovy, E.; Luong, T.; Le, Q. Unsupervised data augmentation for consistency training. Advances in neural information processing systems 2020, 33, 6256–6268.

- Hou, Y.; Liu, Y.; Che, W.; Liu, T. Sequence-to-sequence data augmentation for dialogue language understanding. arXiv preprint arXiv:1807.01554 2018.

- Kazemnejad, A.; Salehi, M.; Baghshah, M.S. Paraphrase generation by learning how to edit from samples. proceedings of the 58th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics, 2020, pp. 6010–6021.

- Iyyer, M.; Wieting, J.; Gimpel, K.; Zettlemoyer, L. Adversarial example generation with syntactically controlled paraphrase networks. arXiv preprint arXiv:1804.06059 2018.

- Chen, M.; Tang, Q.; Wiseman, S.; Gimpel, K. Controllable paraphrase generation with a syntactic exemplar. arXiv preprint arXiv:1906.00565 2019.

- Kumar, A.; Ahuja, K.; Vadapalli, R.; Talukdar, P. Syntax-guided controlled generation of paraphrases. Transactions of the Association for Computational Linguistics 2020, 8, 330–345.

- Sun, J.; Ma, X.; Peng, N. AESOP: Paraphrase generation with adaptive syntactic control. Proceedings of the 2021 conference on empirical methods in natural language processing, 2021, pp. 5176–5189.

- Yang, H.; Lam, W.; Li, P. Contrastive representation learning for exemplar-guided paraphrase generation. arXiv preprint arXiv:2109.01484 2021.

- Liu, M.; Yang, E.; Xiong, D.; Zhang, Y.; Sheng, C.; Hu, C.; Xu, J.; Chen, Y. Exploring bilingual parallel corpora for syntactically controllable paraphrase generation. Proceedings of the Twenty-Ninth International Conference on International Joint Conferences on Artificial Intelligence, 2021, pp. 3955–3961.

- Yang, K.; Liu, D.; Lei, W.; Yang, B.; Zhang, H.; Zhao, X.; Yao, W.; Chen, B. Gcpg: A general framework for controllable paraphrase generation. Findings of the Association for Computational Linguistics: ACL 2022, 2022, pp. 4035–4047.

- Huang, P.S.; He, X.; Gao, J.; Deng, L.; Acero, A.; Heck, L. Learning deep structured semantic models for web search using clickthrough data. Proceedings of the 22nd ACM international conference on Information & Knowledge Management, 2013, pp. 2333–2338.

- Shen, Y.; He, X.; Gao, J.; Deng, L.; Mesnil, G. A latent semantic model with convolutional-pooling structure for information retrieval. Proceedings of the 23rd ACM international conference on conference on information and knowledge management, 2014, pp. 101–110.

- Palangi, H.; Deng, L.; Shen, Y.; Gao, J.; He, X.; Chen, J.; Song, X.; Ward, R. Semantic modelling with long-short-term memory for information retrieval. arXiv preprint arXiv:1412.6629 2014.

- Wan, S.; Lan, Y.; Guo, J.; Xu, J.; Pang, L.; Cheng, X. A deep architecture for semantic matching with multiple positional sentence representations. Proceedings of the AAAI conference on artificial intelligence, 2016, Vol. 30.

- Hu, B.; Lu, Z.; Li, H.; Chen, Q. Convolutional neural network architectures for matching natural language sentences. Advances in neural information processing systems 2014, 27.

- Pang, L.; Lan, Y.; Guo, J.; Xu, J.; Wan, S.; Cheng, X. Text matching as image recognition. Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence, 2016, Vol. 30.

- Chen, Q.; Zhu, X.; Ling, Z.; Wei, S.; Jiang, H.; Inkpen, D. Enhanced LSTM for natural language inference. arXiv preprint arXiv:1609.06038 2016.

- Pang, L.; Lan, Y.; Guo, J.; Xu, J.; Xu, J.; Cheng, X. Deeprank: A new deep architecture for relevance ranking in information retrieval. Proceedings of the 2017 ACM on Conference on Information and Knowledge Management, 2017, pp. 257–266.

- Papineni, K.; Roukos, S.; Ward, T.; Zhu, W.J. Bleu: a method for automatic evaluation of machine translation. Proceedings of the 40th annual meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics, 2002, pp. 311–318.

- Bui, T.C.; Le, V.D.; To, H.T.; Cha, S.K. Generative pre-training for paraphrase generation by representing and predicting spans in exemplars. 2021 IEEE International Conference on Big Data and Smart Computing (BigComp). IEEE, 2021, pp. 83–90.

- Pennington, J.; Socher, R.; Manning, C.D. Glove: Global vectors for word representation. Proceedings of the 2014 conference on empirical methods in natural language processing (EMNLP), 2014, pp. 1532–1543.

- Guu, K.; Hashimoto, T.B.; Oren, Y.; Liang, P. Generating sentences by editing prototypes. Transactions of the Association for Computational Linguistics 2018, 6, 437–450.

- Liu, X.; Chen, Q.; Deng, C.; Zeng, H.; Chen, J.; Li, D.; Tang, B. Lcqmc: A large-scale chinese question matching corpus. Proceedings of the 27th international conference on computational linguistics, 2018, pp. 1952–1962.

- Chen, J.; Chen, Q.; Liu, X.; Yang, H.; Lu, D.; Tang, B. The bq corpus: A large-scale domain-specific chinese corpus for sentence semantic equivalence identification. Proceedings of the 2018 conference on empirical methods in natural language processing, 2018, pp. 4946–4951.

- Kingma, D.P.; Ba, J. Adam: A method for stochastic optimization. arXiv preprint arXiv:1412.6980 2014.

- Schwarz, S.; Pawlik, M.; Augsten, N. A new perspective on the tree edit distance. Similarity Search and Applications: 10th International Conference, SISAP 2017, Munich, Germany, October 4-6, 2017, Proceedings 10. Springer, 2017, pp. 156–170.

- Wieting, J.; Gimpel, K. ParaNMT-50M: Pushing the limits of paraphrastic sentence embeddings with millions of machine translations. arXiv preprint arXiv:1711.05732 2017.

- Devlin, J.; Chang, M.W.; Lee, K.; Toutanova, K. Bert: Pre-training of deep bidirectional transformers for language understanding. arXiv preprint arXiv:1810.04805 2018.

- Mihalcea, R.; Tarau, P. Textrank: Bringing order into text. Proceedings of the 2004 conference on empirical methods in natural language processing, 2004, pp. 404–411.

- 龙船社区. https://club.imarine.cn/, 2024. Accessed: 2024-07-21.

- 技术邻问答. https://www.jishulink.com/answer, 2024. Accessed: 2024-07-21.

- Dong, L.; Yang, N.; Wang, W.; Wei, F.; Liu, X.; Wang, Y.; Gao, J.; Zhou, M.; Hon, H.W. Unified language model pre-training for natural language understanding and generation. Advances in neural information processing systems 2019, 32.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).