1. Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic has triggered seismic shifts in how we work [

1,

2]. [

3] observes that the impact of COVID-19 on work culture arguably represents the most drastic and rapid shift to the global workforce that has been witnessed since World War II. Organizations around the world, including many in Africa, have been forced to transition from an office-centric culture to more flexible ways of working [

4]. This shift has been necessitated by associated health conditions of the pandemic and the need for safety controls for employees.

Underpinning this shift is the tacit assumption that remote work, or work-from-home (WFH) offer a certain assurance of safety for employees in what many perceive as over-exposed office spaces [

5]. Such assumptions also come with an implicit belief that all that matters for a successful and efficient functioning of a remote work regime is time away from the physical office, availability and effectiveness of computing and internet technologies that connects employees to employers.

While the availability of these essential technologies may be the most fundamental requirements for an effective and successful remote work regime it has also become increasingly evident that some of these assumptions are flawed and premised on faulty understandings of the full implications of WFH [

6]. Many organizations and their employees are yet to critically appraise what it means to work from home and what that also means to the health, wellbeing, and productivity of employees [

7].

Issues such as the suitability of the home environment from the perspective of workspaces, workstation, comfort, ergonomics, safety, supplies, health, mental state, and wellbeing conditions in the homes of employees are not considered. Most, if not all of these, are taken-for granted omissions in current remote work discussions in many organizations in Africa and even more so in Ghana where there has since been a popular embrace of remote work by some organizations as a post-pandemic work culture.

Despite its growing popularity, however, there is no real attention given to the policy and regulatory mechanisms that should protect the health, safety and wellbeing of employees who work from home. The focus so far has been on the availability of technological logistics and particularly internet connectivity, which, in many instances, is considered the most essential requirement for a successful remote work practice [

8,

9]. While these issues remain critical concerns, it is also important to acknowledge the fact that the suddenness of the pandemic and dramatic large-scale shift to a remote work culture did not allow deeper considerations of how such a shift could influence not only productivity, but also the health and wellbeing of employees [

7,

10].

Learning, therefore, has been steep and incipient as most workers and their employees navigate the new world of working from home. As learning continues, and as organizations and their employees begin to come to terms with the full implications of remote work in a post-pandemic future of work, what is also becoming clear and indeed worrying is that beyond the threat of Covid-19 and the relative safety of employees working from home, there are other emerging issues such as health, safety and overall wellbeing of employees in the home environment [

11]. For the most part in Ghana, and across Africa, these remain taken-for- granted issues which are yet to be foregrounded for critical consideration.

This study foregrounds remote work or WFH as a Covid- 19 induced organizational change practice which has influenced significant long-term changes in work culture around the world [

12]. Using Ghana as a reference, the study explores some emerging, but underestimated issues that underly remote work practices in Africa. In particular, the study highlights issues of environment, health, safety and wellbeing in current remote work practices in Africa by exploring the implications of such conditions to the future of remote work in Africa. The study is therefore guided by the question: how might current circumstances and conditions surrounding remote work inform an imagination of a post-pandemic future of work in Ghana and Africa, broadly, and how will issues of the environment, health, safety and employee wellbeing feature in such an imaginary?

In attempting to answer this question, the study takes the position that much as many employers and employees in Ghana’s formal sector have found convenience in remote work and have shown desire for its institutionalization even beyond the pandemic, there are other aspects of remote work that have been muted in current discussions. Thus, the paper explores employee impressions, experiences, and desires around remote working in Ghana. It discusses desires and expectations as an avenue to know and understand not only what challenges exist, but also what possibilities are there within current practices to facilitate bold imaginations of how an employee-focused remote work future might ensure the health and safety of employees within their home-work environments.

Histories of Remote Work Futures

Remote work as an emergent practice derives its histories from earlier practices such as telecommuting which, according to [

13] was used to define employees who, for one reason or the other, worked from their homes and used technology to connect or communicate with their offices. Other terminologies such as e-workers have been in existence to describe work away from office premises and one through which communication is primarily through electronic or digital media with limited face-to-face interactions [

14]. The terminology of mobile working, according to [

15], is used interchangeably with mobile teleworking while multilocation working is linked to working from a remote location or on the move.

Homeworking, Remote Work or Flexible Work Hours (HWH) have all been used interchangeably and are characterized by the option for employees to work from home occasionally, sometimes, or mostly [

16]. Home-based teleworking is a recent phenomenon related to the remote working domain [

17]. The recent COVID-19 global pandemic has somehow reinvented the practice of remote work to make contemporary notions of remote work more distinct, obviously because of scale and circumstances, and aided by more advanced technologies.

In all types, however, associated arrangements offer both employers and employees a diversity of advantages that are supposed to enhance work and-life balance [

17,

18,

19]. The difference between the contemporary notion of work-from-home and past notions lies in its recent origins: the COVID 19 pandemic and its unprecedented influence in institutionalizing remote work cultures at scale and across sectors. Until the pandemic, remote work as a practice was not very well known in mainstream work practices in Ghana, and Africa broadly and was somehow perceives as am ‘elitist phenomenon’ obviously because of the uniqueness and privileges it offers to a select group of employees.

This perception, however, has changed very quickly because of the pandemic and the nature of its impacts. The transition to working from home (WFH) during the pandemic and its revolutionary nature has been made possible by the widespread availability and effectiveness of modern information and communications technologies which have dramatically aided the shift in how organizations and employees think about work and the role of the physical office space. Such cultural and organizational transformation on the labor market are undoubtedly significant changes, which have occurred with unprecedented speed.

The popularity of current remote work practices from the perspective of the pandemic, the threat it posed, and the sheer numbers of people and organizations it affected somehow differentiates current notions from earlier notions. A major distinction is, COVID 19-induced work from home culture was never one of choice or expedience, but one of absolute necessity and indeed compulsion by the circumstance [

7]. Against the background of the pandemic, therefore, and associated policy calls such as mass lockdowns, social distancing, technology-aided operations, the office became the fallout place as many organizations felt compelled by the circumstance to reduce physical presence in the office to reduce operational risk.

Such decisions, as were necessitated by the threat of the pandemic, have in many ways facilitated the institutionalization of remote work practices as a necessary alternative to traditional notions of work and in the process, turning remote work into something of a normative which has grown both in preference and popularity. Even as the COVID-19 threat has come under some control in recent times to restore public confidence in a return to the office, many organizations and their employers have opted to continue working from home or opted for a hybrid system that converges both the past and the future of work in very innovative ways [

20]. Hybrid, as has also come to be known [

21], has since emerged as an option for many organizations and their employees. Its popularity has been on the increase even post the pandemic to suggest how current levels of preference by employees and employers are not necessarily influenced by the fear of a health threat or any uncertainties, but because employees like it and see value in the flexibility it offers.

While there are obvious advantages in current remote work regimes to both employers and employees, there are also some disadvantages which require attention. For example, some remote workers tend to overwork themselves by spending longer hours on work than they would usually do at the office [

22]. Others come under strict and intrusive surveillance from line-managers that put them under severe mental health stresses [

23,

24]. In addition, there is also the issue of the home environment and the fact that many homes, particularly in Africa, are not well set up for remote work so face significant workstation and ergonomic challenges that often impact employees’ health and wellbeing. All these, however, point to the challenges of an emergent practice in situations across Africa where most organizations and institutions seem to have embraced a practice that they have not fully considered its implications.

Employee Wellbeing and Remote Work in Ghana

In Ghana and across Africa, such issues as they relate to employee health and wellbeing from a WFH perspective are becoming common place but are yet to receive the requisite policy and practice attention [

11]. The focus so far has been on efficiency and productivity and of course profits, which remains the primary concern of many organizations, especially the private sector. Thus, once critical needs such as computer and internet availability are provided or addressed, the general assumption is that remote work is expected to be fully functional and without problems. The health, safety, and wellbeing of employees, as well as the suitability of the working environment have not been a priority concern for many employers in current remote work regimes in Ghana and in many other African countries.

As remote work practices grow in popularity and in preference, associated challenges are also becoming major concerns for employees requiring that some focused attention is given to the exploration of solutions. Such concerns, particularly as they relate to the suitability of the home environment, health and wellbeing of employees should be situated within the broader labor policy contexts of countries with a view to exploring possible learnings and existing gaps .The situation in Ghana is even more worrying and urgent considering the fact that the country is yet to have any policy and legislation in place to support occupational work and safety [

25]. This is against the background of growing popularity of remote work and a high likelihood of further institutionalization and embrace of the practice in Ghana and in many other African countries [

26,

27].

Despite this possibility, there has been little or no discussion on what such a transition might or should mean for both the health, safety, and wellbeing of employees. The absence of policies and regulatory mechanisms, especially in Ghana, has created a vacuum and situations where most organization choose how they want to operate without making the necessary considerations for employees’ health, safety, and wellbeing in the home environment and from the perspective of the law. The priority, as indicated earlier, has been on efficiency, productivity, and profits; however, with increases in remote work preferences and popularity in Africa, there is need for governments and employees to give issues of health and safety the needed attention by putting in place the requisite policies and regulatory mechanism’s that assure and ensure employees wellbeing [

28].

That said, as the comparative advantages of remote work continue to be widely touted and perceived generally has having the potential to define the future of office-based work [

29,

30,

31], it becomes urgently imperative that focused attention is given to what we describe in this work as the post-pandemic future of work in Africa. That imaginary has not yet happened, at least not in Ghana, as well as in many other countries across Africa. As this nascent WFH culture begins to flourish in Ghana, it is also becoming increasingly apparent and indeed worrying that some employees have faced and continue to face significant health and safety challenges as they respond to highly daunting employer expectations [

32].

The sad reality, however, is that even against the background of emerging evidence of employee’s health and safety challenges from the home environment most employees are hesitant, reluctant, or unable to voice out for different reasons. The apparent lack of labor laws on occupational health and safety and specifically on remote work practices in Ghana and many other African countries means some employees will have no choice, but to endure any health and safety challenges that come with their works at home [

33].

Conceptual Framework

The Job Demands-Resources (JD-R) model provides a detailed framework for understanding the dynamic interplay between job demands, job resources, and their impact on employee well-being and performance. Originally introduced by [

34], the model was designed to capture the dual processes that lead to either employee burnout or engagement. The JD-R model builds on earlier work by [

35] on job demands-control and [

36] on effort-reward imbalance, integrating these theories into a more comprehensive framework. In the context of remote work, this model is particularly useful for analyzing how different factors contribute to employees’ health, motivation, and productivity. Job demands refer to the physical, psychological, social, or organizational aspects of a job that require sustained effort or skills and are associated with certain physiological and psychological costs. In remote work settings, common job demands include workload, time pressure, technological challenges, and isolation. Conversely, job resources are the physical, psychological, social, or organizational aspects of the job that help achieve work goals, reduce job demands, and stimulate personal growth, learning, and development. In remote work contexts, job resources can include technological support, flexible working hours, social support from colleagues and supervisors, and ergonomic home office setups.

Further, the JD-R model posits that the balance between job demands, and job resources determine employee outcomes. High job demands can lead to strain and burnout, while adequate job resources can enhance motivation and engagement. Applying this model to remote work environments highlights several critical areas. First, technological challenges and support are crucial. During the COVID-19 pandemic, many organizations worldwide experienced a sudden shift to remote work, leading to increased technological demands. Employees had to adapt to new software, hardware, and communication tools, which created significant stress. Organizations that provided robust IT support and training were able to mitigate these challenges, enhancing employee productivity and satisfaction. In Ghana, the transition to remote work highlighted the digital divide. Many employees faced difficulties due to inadequate internet connectivity and lack of access to modern technology. Companies that invested in improving technological infrastructure and providing necessary equipment helped their employees cope better with the demands of remote work.

Second, workload and flexibility play a significant role. Research from various countries shows that remote work can blur the boundaries between work and personal life, leading to increased workload and time pressure. Employers that implemented flexible working hours and clear work-life balance policies were able to reduce employee stress and prevent burnout. In Ghana, the informal sector’s large presence means many workers juggle multiple roles. Organizations that allowed flexible scheduling and respected employees’ need for personal time saw higher levels of employee engagement and lower stress levels. Third, social isolation and support are important factors. Social isolation is a significant job demand in remote work settings. Employees miss the informal interactions and support they receive in a traditional office environment. Companies that encouraged regular virtual meetings, team-building activities, and open communication channels helped mitigate feelings of isolation and promoted a sense of belonging. A culture that values community and social interactions such as Ghana, and many across Africa, also implies the intentional creation of work opportunities and habits that that fosters virtual engagements that supports peer networking and interaction. Such a culture enhances n employees’ social connections and mental well-being. Fourth, ergonomics and physical health cannot be overlooked. The shift to remote work often led to inadequate ergonomic setups at home, contributing to physical health issues like back pain and eye strain. Companies that provided ergonomic equipment and guidelines for home office setups saw improvements in employees’ physical well-being and productivity. However, in Ghana, where many homes are not designed for office work, employees faced significant ergonomic challenges either from the lack of approximate furniture or the use of poorly designed ones. . Employers who invested in providing ergonomic furniture and educating employees on proper workspace setup significantly improved their health outcomes.

Finally, the JD-R model shows the importance of a balanced approach to managing job demands and resources in remote work settings. For organizations in Ghana and globally, it is crucial to invest in technology and training, promote work-life balance, foster social connections, and enhance ergonomic support. Ensuring all employees in remote work conditions have access to reliable internet and modern technology, flexibility in work schedules working and clear enabling policies to prevent burnout and anxieties.

In our view, organizations can better understand the complexities of remote work and develop targeted interventions to enhance employee well-being and productivity through the application of the JD-R model. This framework provides a robust foundation for analyzing and addressing the unique challenges and opportunities presented by remote work in both global and Ghanaian contexts.

2. Materials and Methods

Research Design and Procedure

This study employed a mixed-method approach, integrating both qualitative and quantitative methods to provide in in-depth understanding of the impacts of remote work on employee well-being and health and safety concerns. The study aimed to gauge the views, opinions, and experiences of remote work employees to inform a larger international comparative study in the West African sub-region. This approach was ideal for systematically collecting and analyzing data from a diverse sample of remote workers across various sectors, allowing for reliable and comparable results [

37].

Literature Review

The research began with an extensive literature review to identify relevant studies and theoretical frameworks addressing remote work and its effects on employee well-being. Searches were conducted on major academic databases, including Google Scholar and SCOPUS, yielding a broad range of studies related to WFH. The initial search returned a large number of results, which were narrowed down to focus on publications directly discussing employee well-being in the context of WFH, especially during the COVID-19 pandemic. The final selection included the most relevant articles and studies for in-depth analysis.

Sampling

Based on the insights gained from the literature review, specific study areas pertinent to understanding the nuances of remote work during the COVID-19 pandemic were identified. The target population consisted of employees from various sectors, including the private sector (corporate and technical), civil servants, multinational companies, NGOs, and academic institutions (basic, secondary, and post-secondary education). A combination of purposive and snowball sampling methods was used. Purposive sampling allowed researchers to select cases that best answered the research questions and met the research objectives. Snowball sampling enabled the recruitment of additional subjects through the initial respondents’ recommendations. A total of 200 respondents participated in the survey, exceeding the original target of 100, reflecting the popularity of the subject and widespread interest in contributing views on remote work.

Data Analysis

Data analysis followed a mixed-method framework. The quantitative data were analyzed using descriptive statistics with the aid of the Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS) Version 22. Descriptive statistics summarized the data, and inferential statistics identified patterns and correlations. Visual formats, including pie charts and bar graphs, were generated to present the data meaningfully and facilitate interpretation.

The qualitative data from open-ended questions were analyzed using thematic analysis. This process involved familiarizing with the data, coding, and identifying themes [

38]. The thematic analysis provided deeper insights into the experiences and perceptions of remote workers, enriching the quantitative findings.

3. Results

Demographics

Sex and Age

Male respondents in the survey constitute the highest proportion of respondents. They are made up of 56% of the total respondents. People within the 31-50 age bracket also make up over half (59%) of the respondent followed by those within 18 – 30 years. Respondents over 50 years constitute only 1% and in a way reflecting the high technology adoption rate among young people in the Ghanaian job market.

Remote Work Experience

As shown in

Figure 1 below, most respondents (87%) have had some remote work experience either in their current works or previous.

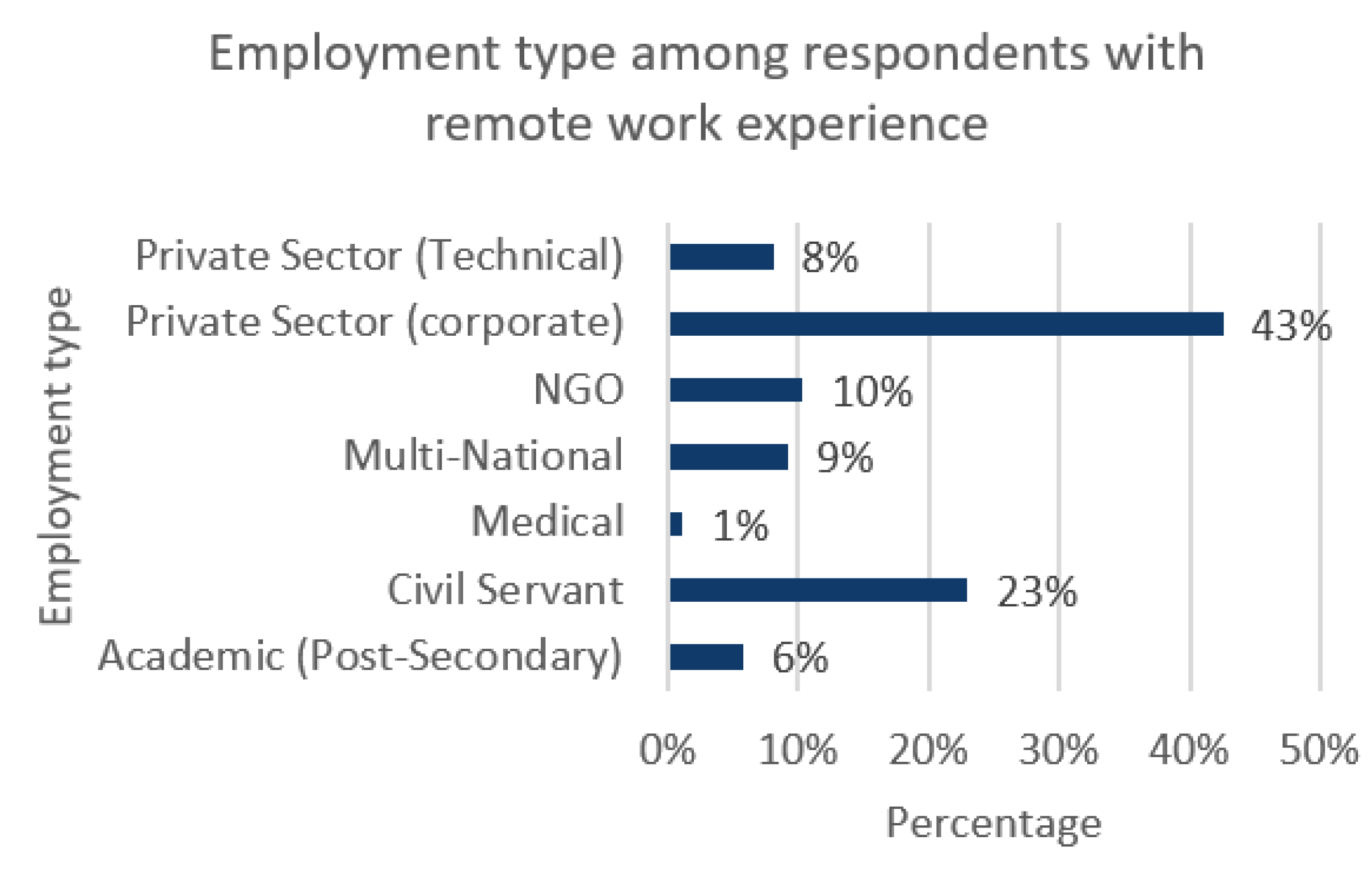

Figure 4 shows that the private sector (corporate and technical) professions constitute 43% and 8% respectively of the number of people that work remotely. This implies that remote work was more popular among the private sector than any other employment type during the covid-19 pandemic. The Civil servant (government) category forms the second highest (23%). NGOs, Multinational and Academic represent 10%, 9% and 6% respectively. Medical staff represent the least of people who work remotely and obviously because of the nature of the services they provide.

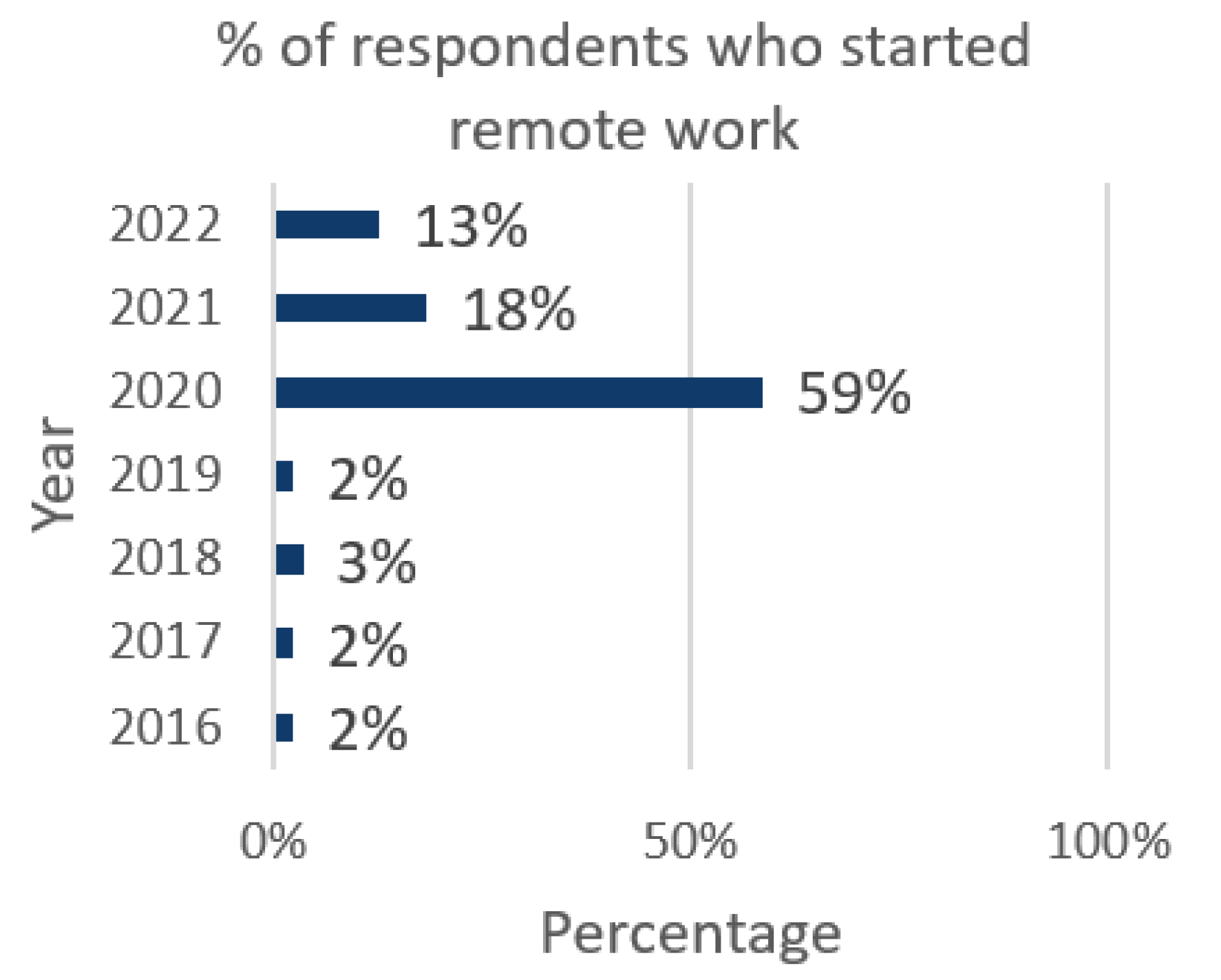

Figure 3 further shows that 2020, the year of the covid-19 outbreak in Ghana, saw the most people (59%) engaged in remote work. The trend also shows that the number of people working remotely declined to 18% in 2021 and further to 13% in middle of 2022 when there was a semblance of a slow return to normalcy after the pandemic waned.

Figure 6 establishes that 77% of respondents’ choice to work remotely was informed primarily by the covid-19 risks while the rests chose remote work for other reasons.

Figure 3.

When respondents started remote work.

Figure 3.

When respondents started remote work.

Figure 4.

Whether remote work was informed by Covid-19 pandemic.

Figure 4.

Whether remote work was informed by Covid-19 pandemic.

WFH Challenges

The challenges associated with working remotely as indicated by the respondents are demonstrated in

Table 1 below. 36% of the respondents identified no challenges associated with working remotely. However, 24% of the respondents indicated logistics issues such as poor internet connection, lack of proper working desk, power instability, etc. as major challenges so far as working from home is concerned. This is closely followed by interference and distraction at home which affect concentration and productivity. Prolonged working hours was also mentioned as a challenge and constituted 11% of total respondents to the question on WFH challenges. 3% of respondents find no difference between working from home and office. Another 3% indicated that they sometimes are required to leave home for the office just to go get a document or a device before they can complete a task. These unplanned commute between home and office are considered by respondents as distractions that cause anxieties and inconveniences. I% of respondents mentioned loneliness, lack of social interaction, boredom, and time differences between multiple countries as a challenge. Another 1% indicated low or poor supervision as a challenge.

When asked what could improve the remote work experience, respondents cited stable internet connectivity (37%), workspace (32%), stable electricity or power (11%), modern office accessories (11%), laptop (5%) and digitized documentation (5%) as illustrated in

Table 2 below.

Health and Safety Concerns Working in Home Environment

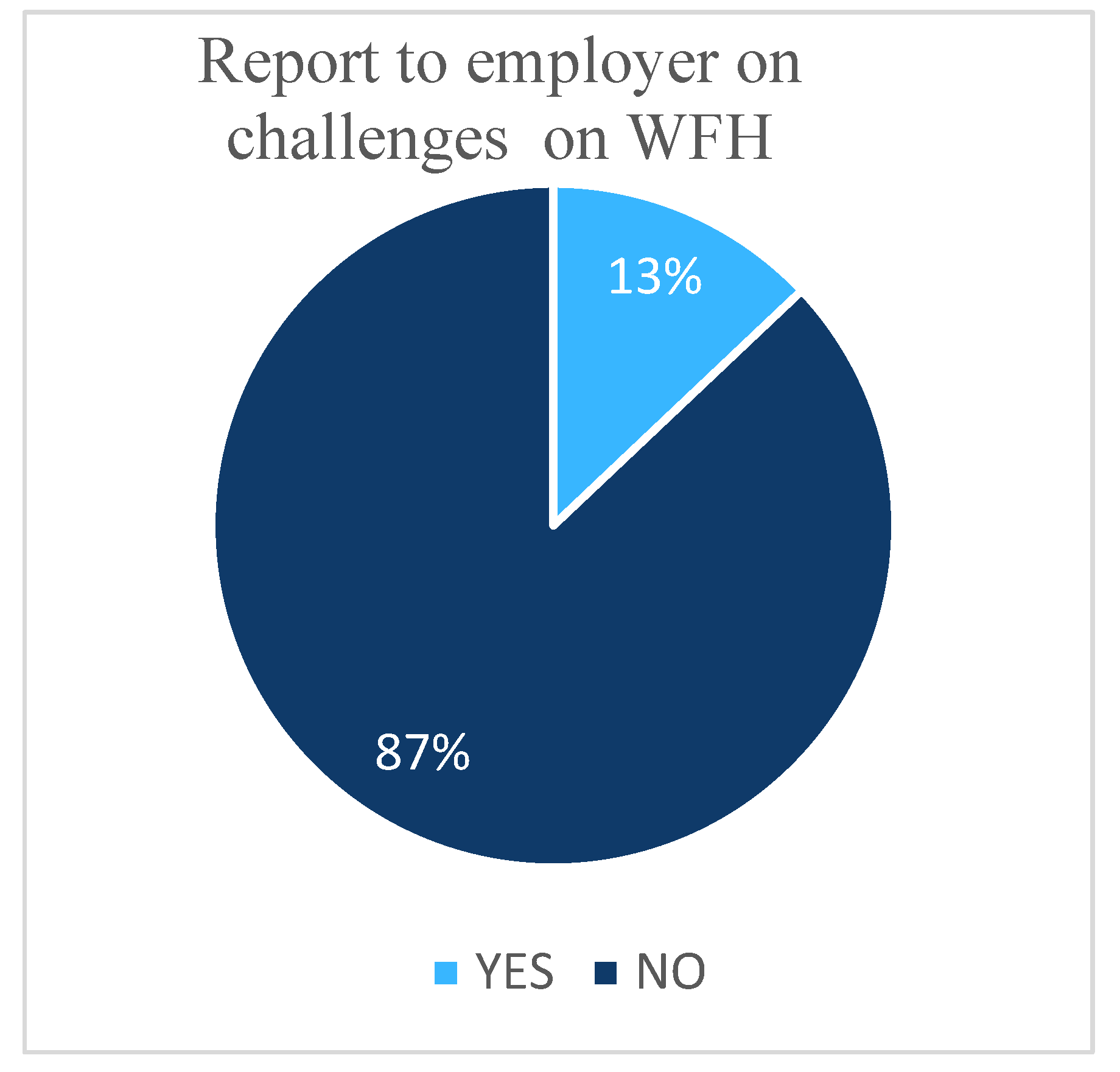

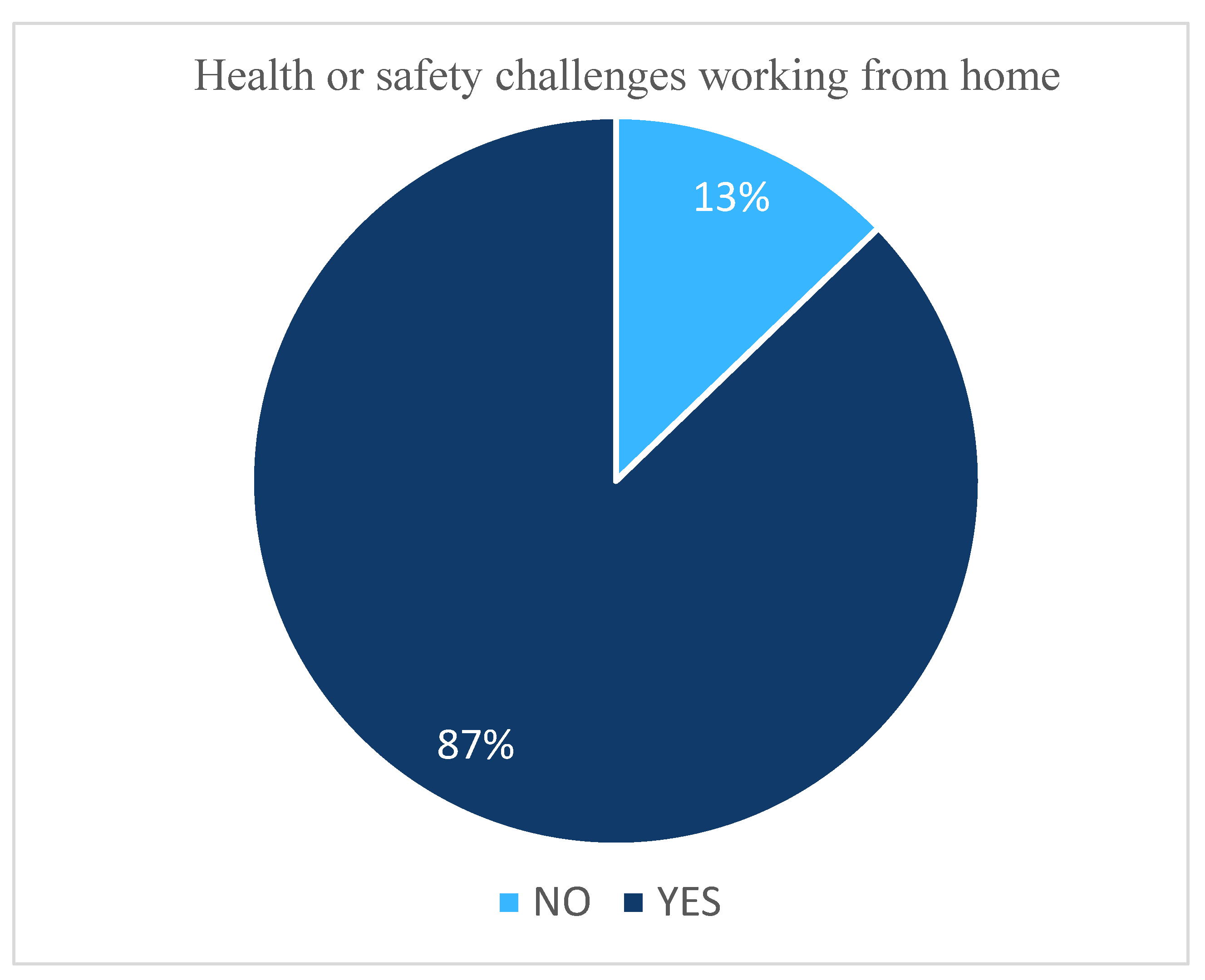

As shown in

Figure 5, 87% of the respondents indicated they experience health and safety challenges under the WFH arrangement while the rest (13%) have no such concerns. Examples of such health and safety challenges are outlined in

Table 3.

Figure 5 shows that 87% of the respondent have made the effort to report to management/employer challenges they face from WFH arrangement while 13% didn’t or had not.

Figure 6.

Report to employer on challenges on WFH.

Figure 6.

Report to employer on challenges on WFH.

Table 4 presents employers’ responses or actions to the concerns raised by employees. These complaints are largely ignored, and nothing is done (44%), dismissed (13%) or no follow-up is made (6%). In 6% of instances, the employer asks the employee to remain professional, which means to endure or to remain loyal and respectful. It was reported that about 6% of employers do not believe employee are telling the truth about the situations they complain about Another (6%) of respondents indicated that some employers address such complaints by educating employees on the need to take short breaks and walks in between work schedules from home Employers also give the option of employees coming to the office if they face an issue with my Wi-Fi at home (6%). A further 6% of respondents, however, received excellent responses to their complaints. 6% also indicated the employer was responsive to the challenges raised.

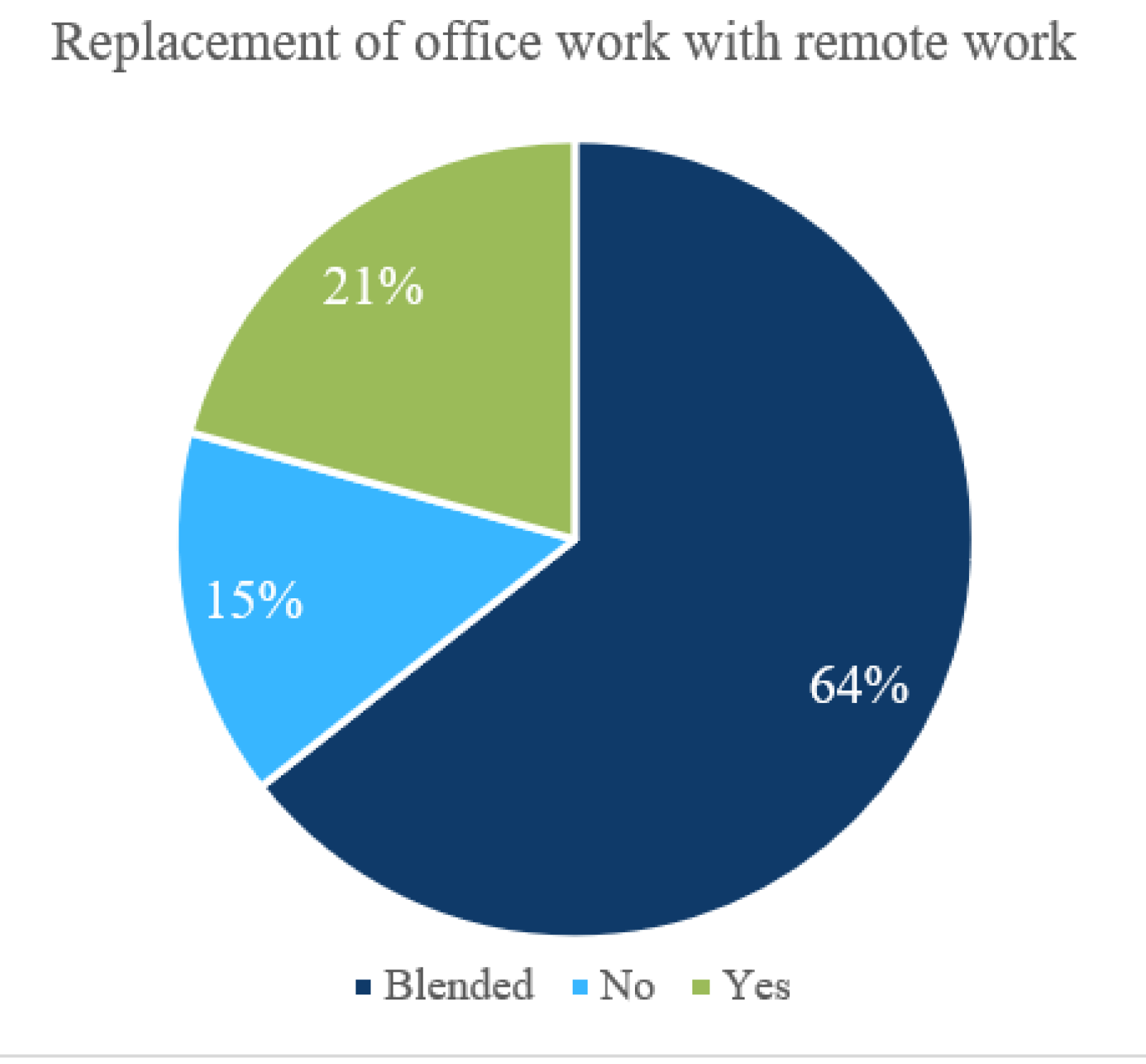

Despite the challenges associated with WFH, about one fifth (21%) of respondents want it to replace office work. However, the majority (64%) of respondents want a blended arrangement while 15% prefer fully office work.

Figure 7.

Replacement of office work with remote work.

Figure 7.

Replacement of office work with remote work.

4. Discussion

While the popularity of remote work is evident from the responses, it is also clear that most employees (respondents) and even employers are not sure of how exactly such a practice will endure and how associated challenges could be addressed going into the future. This is evident from the nature of identified challenges, complaints and how they are resolved, or not. For instance, a suggestion, as was made by an employer, for a complaining employee to take short breaks and walks signals an unprofessional response, which only points to a lack of knowledge and appreciation of the enormity of the complaint.

It is also clear from the study findings that while there has been a reduction in the number of organizations engaged in remote work practice post the pandemics, there are also a few organizations who have embraced it as part of their post-post-pandemic work culture and are still in the process of institutionalizing it at as part of the work culture [

6,

39]. Hybridism, which [

40] describes as providing a level of flexibility that allows employees the freedom to split their time between the workplace and remote working, has emerged as a preference some of these organizations and by virtue of its ability to provide a rare and much desired flexibility This kind of flexibility has somewhat endeared to most employees, who see it as a convenient approach to enjoy the benefits or even previledge of working in flexible schedules where they are able to do a number of weeks or days at home and return to the office for an equal number of days or weeks in rotations.

It is evident from study findings that even though employees tend to like the idea of flexibility in where they work, that is either remotely or in the office, they are also worried about their wellbeing, health and safety in the home working environment. These issues, some employees, believe, have either been ignored, underestimated, or taken for granted. Addressing these concerns are critical in defining the future of remote work as a policy and cultural practice and what expectations are to come with it in terms of regulations both in Ghana and across Africa. Beyond functional issues as was reported by some respondents such as loneliness, supervisor intimidations, erratic power supply, and poor internet access, there is also the issue of lack of office space and appropriate workstations. Indeed, 32% of respondents mentioned office space as a major concern and that is only second to the 37% who complained about internet-related challenges.

Implicit in the idea of the lack of office space is also the lack of proper office equipment such as ergonomic chairs and tables which should provide the requisite comfort, health, and wellbeing for employees at work in the home environment. Even though the issue of office space and its other connotations were a major concern for employees, it is also evident that most employees did not readily associate these challenges with any issues around health, safety, and well-being. This again is a matter of knowledge and the fact that some employees are ignorant about the right conditions they need to function in for maximum health and wellbeing. For instance, some respondents indicated having back problems and swollen feet and attribute that to prolonged sitting at one place without movement. These sentiments as expressed affirm what [

41] observed about sedentary behavior and the development of chronic diseases. However, what is not clear is whether employees have the awareness and understanding that these are right-based issues, which should be addressed under the conditions of service in WFH situations. This is also against the background that Ghana is yet to have any regulatory rules and mechanisms within the labor laws on remote work.

A critical examination of such issues from the perspective of the home environment and the provisions available for work gives indication of how the home environment is not well-equipped with the requisite tables and chairs and how such conditions are creating health problems for some employees. Some respondents indicated sitting for too long and getting swollen feet, others talked about working from their sofas or any available chair and table within the household and those in many ways contribute to the kinds of ergonomic challenges they experience [

42,

43,

44,

45]

As a response to the specific question of whether employees experienced any health and safety challenges, a whopping 87% of the respondents responded in the affirmative. A major complaint among respondents is the fact that they sit for too long and end up experiencing back and neck pains. It is interesting to note that as high as such complaints are among respondents, not a lot of them make direct attributions to the nature of their workstations and the furniture they use, but rather the fact that they believe they sit for too long in isolated conditions. Undoubtedly, the issue of loneliness and stationarity for longer periods could be linked to reports of employee backaches and swollen feet, however, it is also clear that what they see as physical challenges clouts their appreciation of the psychological threats or challenges that impact mental health in remote work conditions.

These concerns are significant but can easily be underrated or ignored. As indicated earlier, they are usually ignored because of ignorance or fear as some employees do not make direct attributions to their health challenges to the fact that the home environment is not properly set up for work. Others fail to act on such complaints because of power dynamics and the fact some employees dare not complain as a way of protecting their employment or livelihood. A common complaint is loneliness, which imply that most workers are used to the office environment where the presence of colleagues provide some psychological comfort to release some physiological pressures off them [

46,

47].

One employee noted that: “You get quite drained sitting for long as I tend to do more work from home”. What this means is that employees tend to do more work from home and as a result end up being drained mentally and physically. While this could be true, it could also be because their loneliness makes them feel they do more work at home than they would normally in the office. Such complaints are indicative of both mental and physical stresses, which seem to be very much at play in current remote work conditions in Ghana and in many other places with little or no attention paid to it [

6,

28].

For instance, some employees mentioned noisy neighborhoods as a major inhibiting factor in their work from home regimes. Such complain validates the earlier point made that remote work cultures in Ghana are not carefully thought through. Noise pollution is cultural in many local communities in Ghana [

48]. It is a common and taken-for-granted phenomenon in many neighborhoods in Ghana [

49]. They are usually disruptive to any function that requires full attention and concentration. If neighborhood characteristics and the likelihood of neighborhood noise levels are taken into consideration in the planning of remote work, certain decisions about remote work would have been reconsidered.

This is because there are some residential neighborhoods in Ghana, especially in urban settings, which are extremely noisy and may not be suitable for any form of WFH. The health consequences of noise pollution in communities are well-documented [

50]. It becomes even more imperative and urgent that such realities are considered in remote work situations in some African communities. Such omissions reveal the cultural dimensions of remote work or WFH and the fact that its origins and character may be alien to formats and conditions in Africa. The serenity of local places, the heavy dependence on technology, the reliability and affordability of internet and electricity are assured factors in some jurisdictions.

That, however, is not the case in most of Africa to put remote work on the same level as it pertains elsewhere. Ghana for instance does not currently have any legal instruments on occupational health and safety [

51], not to mention remote work. This therefore implies that in an unregulated environment, such as there is in Ghana, the tendency for employees’ human rights abuse in current remote work regimes is high and very likely. Thus, if all employers care about is internet connectivity and the availability of computers for functional remote work then it becomes obvious and worrying that the health, safety and wellbeing and suitability of the home environment of employees is not prioritized as an issue of concern.

Even worse is the fact that in rare instances when some employees have been bold enough to report some of these challenges as they experience them at home to their bosses for redress, nothing has been done. 44% of respondents indicated they have made complaints about health and safety challenges, but nothing has ever been done about them. 13% mentioned that their bosses have been mostly dismissive of such complaints. The ‘best’ responses some have had from their superiors is some advice, or better still, a reprimand to be ‘professional’—to get on with the job without complain—or to take short intervals of break to walk and to stretch their muscles.

In other situations, when employees have complained, the only solution available is to return to the office to work and in the process give up the privileges, opportunities, and benefits of working from home. Such an option, as solution, is at best simplistic and abusive because most employees are highly in favor of the flexibility of working from home away from the office and all they ask for is improvements in the working conditions at home for them. Indeed, that should not even be an ask from employees; it must be a precondition for effective and successful remote work.

5. Conclusions

The future of work has undoubtedly been brought forward into the present by the pandemic and with significant implications for both the employee and employer [

11]. While remote work in Ghana, like many other countries in Africa, has come about as happenstance occasioned by the suddenness and disruptiveness of the pandemic, it has also left in its wake critical lessons of the future that requires prompt learnings and urgent actions in the present. The imperative then is to touch the future in the present by putting current lessons into a futures perspective to inform a better and accurate imagination of how a preferred remote work culture might look like.

As it has become evident in many countries around the world and certainly in Ghana, even though the pandemic has officially been declared over [

52], some of its disruptive and transformational legacies have remained and will remain into the foreseeable future. Remote work, or WFH though not a new phenomenon, has since seen a renaissance which has propelled its popularity and embrace. While many organizations embrace it as an emergent practice with potential value for permanent organizational changes, there is also no doubt that the suddenness of the pandemic and the urgency for organizations to stay afloat and economically functional did not allow deeper reflection, interrogation, and consideration of the full implications of WFH.

Many organizations were therefore forced into the deep end of the pool without any guidance of what it means to work from home away from the office and what challenges may be associated with such a change. Consequently, several aspects of working from home were taken for granted and in ways that have left many employers believing that all that matters for successful remote work regime is the availability of internet and associated technologies that connect employers and employees from whatever locations. Clearly missing in the list of priorities for successful remote work, at least in Ghana, were a conducive work environment at home, appropriate ergonomic furniture for a safe and healthy workstation, reliable internet connectivity and most importantly, the mental discipline of working independently and alone at home.

The mental health, environmental and safety conditions were all not perceived as issues fundamental to a meaningful remote work regime. Responses from this study has demonstrated that most organizations failed to consider in any serious way the critical importance of employee well-being in a safe and healthy home environment. The focus seems to have been on profits and not people as obvious issues of environment, health, safety, and human rights were either ignored or underestimated. Even when such matters have emerged and became a matter for discussion, their importance and urgency have been u underestimated. Issues of noise pollution and associated emotional and psychological challenges are also not given any consideration or attention to address its mental health ramifications in remote work regimes. Most worrying is the fact that such incidents are generally under reported or not at all for fear of victimization by employees. This is particularly in relation to women as they struggle to adjust to new and unfamiliar home-based work culture with stringent and uncompromising timelines and conditions from superiors or line managers.

The imperative to learn from current practices and emerging lessons could not have been any more urgent or timely. The lack of any legislative instrument addressing issues of occupational health and safety makes it even more critical that lessons from current WFH practices are observed and documented with a view to finding culturally responsive solutions that situate the practice within clearly defined regulatory and policy mechanisms. Ultimately, a successful remote work regime must be meaningful and fulfilling and this can only be possible if the interests of employees, especially in deprived environments such as Ghana are highlighted and prioritized in such practices.

References

- Ruhle, S. and Schmoll, R. (2021). COVID-19, telecommuting, and (Virtual) sickness presenteeism: Working from home while ill during a pandemic, Frontiers in Psychology, 12. [CrossRef]

- Matli, W. (2020).The changing work landscape as a result of the Covid-19 pandemic: insights from remote workers life situations in South Africa, International Journal of Sociology and Social Policy, 40(9/10), pp. 1237–1256. [CrossRef]

- Ozimek, A. (2020) The future of remote work, Social Science Research Network [Preprint]. [CrossRef]

- Brynjolfsson, E.; et al. (2020) COVID-19 and remote work: An early look at US data. [CrossRef]

- Cahapay, M.B. (2020) Social Distancing Practices of Residents in a Philippine Region with Low Risk of COVID-19 Infection, European Journal of Environment and Public Health, 4(2), p. em 0057. [CrossRef]

- Buomprisco, G.; et al. (2021) Health and Telework: New Challenges after COVID-19 Pandemic, European Journal of Environment and Public Health, 5(2), p. em 0073. [CrossRef]

- Galanti, T.; et al. (2021) Work from home during the COVID-19 outbreak, Journal of Occupational and Environmental Medicine, 63(7), pp. e426–e432. [CrossRef]

- Ng, P.M.L. , Lit, K.K. and Cheung, C.T.Y. (2022) ‘Remote work as a new normal? The technology-organization-environment (TOE) context,’ Technology in Society, 70, p. 102022. [CrossRef]

- Eurofound, I. L. O. (2017). Working anytime, anywhere: The effects on the world of work. Luxembourg, Geneva.

- Dé, R., Pandey, N. and Pal, A. (2020) Impact of digital surge during Covid-19 pandemic: A viewpoint on research and practice, International Journal of Information Management, 55, p. 102171. [CrossRef]

- Adonu, D. , Opuni, Y.A. and Dorkenoo, C.B. (2020). Implications of COVID-19 on human resource practices: A case of the Ghanaian formal sector, Journal of Human Resource Management, 8(4), p. 209. [CrossRef]

- De Lucas Ancillo, A. and Del Val Núñez, M.T. (2020) Workplace Change Within the COVID-19 Context: A Grounded Theory Approach, Ekonomska Istrazivanja-economic Research, 34(1), pp. 2297–2316. [CrossRef]

- Nilles, J. (1975) Telecommunications and organizational decentralization. https://www.semanticscholar.org/paper/Telecommunications-and-Organizational-Nilles/3de73158e70793d147433a17865fe49e915d140f.

- Kirk, J.J. and Belovics, R. (2006) Making e-working work, Journal of Employment Counseling, 43(1), pp. 39–46. [CrossRef]

- Hislop, D. and Axtell, C. (2009) ‘To infinity and beyond?: workspace and the multi-location worker,’ New Technology Work and Employment, 24(1), pp. 60–75. [CrossRef]

- Smith, A. , & Johnson, B. (2022). The evolution of flexible work arrangements: Definitions and practices. Journal of Workplace Flexibility, 15(3), 245-260.

- Brown, L. (2023). The rise of home-based teleworking in the digital age. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 96(2), 178-195.

- Wheatley, D. (2016) ‘Employee satisfaction and use of flexible working arrangements,’ Work Employment and Society, 31(4), pp. 567–585. [CrossRef]

- Moos, M. and Skaburskis, A. (2007) ‘The characteristics and location of home workers in Montreal, Toronto and Vancouver,’ Urban Studies, 44(9), pp. 1781–1808. [CrossRef]

- Hensher, D.A., Wei, E. and Liu, W. (2023) ‘Accounting for the spatial incidence of working from home in an integrated transport and land model system,’ Transportation Research Part a Policy and Practice, 173, p. 103703. [CrossRef]

- Stewart, A. (2023) What is hybrid working?, Breathe. Available at: https://www.breathehr.com/en-gb/blog/topic/flexible-working/what-is-hybrid-working (Accessed: 05 March 2024).

- Donnelly, R. and Johns, J. (2020) ‘Recontextualising remote working and its HRM in the digital economy: An integrated framework for theory and practice,’ The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 32(1), pp. 84–105. [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. (2022). Mental health at work. World Health Organization. Retrieved February 14, 2023, from https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/mental-health-at-work.

- Mann, S. and Holdsworth, L. (2003) ‘The psychological impact of teleworking: stress, emotions and health,’ New Technology, Work and Employment, 18(3), pp. 196–211. [CrossRef]

- Annan, J. ., Addai, E.K. and Tulashie, S.K. (2015) Short Communication a Call for Action to Improve Occupational Health and Safety in Ghana and a Critical Look at the Existing Legal Requirement and Legislation. Safety and Health at Work, 6, 146-150.

http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S2093791115000025

. [CrossRef]

- INTERNATIONAL LABOUR OFFICE., (2020). EMPLOYERS’ GUIDE ON WORKING FROM HOME IN RESPONSE TO THE OUTBREAK OF COVID-19. BUREAU FOR EMPLOYERS’ ACT.

- Šmite, D. et al. (2023) ‘From forced Working-From-Home to voluntary working-from-anywhere: Two revolutions in telework,’ Journal of Systems and Software, 195, p. 111509. 1509. [CrossRef]

- Kniffin, K.M.; et al. (2021). COVID-19 and the workplace: Implications, issues, and insights for future research and action., American Psychologist, 76(1), pp. 63–77. [CrossRef]

- Xiao, Y.; et al. (2020) ‘Impacts of Working from home during COVID-19 Pandemic on Physical and Mental Well-Being of Office Workstation Users,’ Journal of Occupational and Environmental Medicine, 63(3), pp. 181–190. [CrossRef]

- Nicholas Bloom, James Liang, John Roberts, Zhichun Jenny Ying, Does Working from Home Work? Evidence from a Chinese Experiment , The Quarterly Journal of Economics, Volume 130, Issue 1, February 2015, Pages 165–218, . [CrossRef]

- Fonner, K. L. Why teleworkers are more satisfied with their jobs than are office-based workers: When less contact is beneficial. Journal of Applied Communication Research, 38(4), 336–361. [CrossRef]

- Belle, S.M. , Burley, D.L. and Long, S.D. (2014) ‘Where do I belong? High-intensity teleworkers’ experience of organizational belonging,’ Human Resource Development International, 18(1), pp. 76–96. [CrossRef]

- Ahrendt, D. , Cabrita, J., Clerici, E., Hurley, J., Leončikas, T., Mascherini, M., Riso, S. and Sándor, E., 2020. Living, working and COVID-19.

- Demerouti, E. , Bakker, A. B., Nachreiner, F., & Schaufeli, W. B. (2001). The job demands-resources model of burnout. Journal of Applied psychology, 86(3), 499.

- Karasek Jr, R. A. (1979). Job demands, job decision latitude, and mental strain: Implications for job redesign. Administrative science quarterly, 285-308.

- Siegrist, J. (1996). Adverse health effects of high-effort/low-reward conditions. Journal of occupational health psychology, 1(1), 27.

- Tourangeau, R. (2020) ‘Survey Reliability: Models, methods, and findings,’ Journal of Survey Statistics and Methodology, 9(5), pp. 961–991. [CrossRef]

- Braun, V. and Clarke, V. (2006) Using thematic analysis in psychology, Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), pp. 77–101. [CrossRef]

- Peters, P. , Ligthart, P.E., Bardoel, A. and Poutsma, E. (2016). ‘Fit’for telework’? Cross-cultural variance and task-control explanations in organizations’ formal telework practices. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 27(21), pp.2582-2603.

- Stewart, A. (2023) What is hybrid working?, Breathe. Available at: https://www.breathehr.com/en-gb/blog/topic/flexible-working/what-is-hybrid-working (Accessed: ). 05 March 2024. [Google Scholar]

- González, K. , Fuentes, J. and Márquez, J.L. (2017) Physical inactivity, sedentary behavior and chronic diseases, Korean Journal of Family Medicine, 38(3), p. 111. [CrossRef]

- Hoe, V.C.W.; et al. (2012) Ergonomic design and training for preventing work-related musculoskeletal disorders of the upper limb and neck in adults, The Cochrane Library [Preprint]. [CrossRef]

- Jensen, C.; et al. (2002) Musculoskeletal symptoms and duration of computer and mouse use, International Journal of Industrial Ergonomics, 30(4–5), pp. 265–275. [CrossRef]

- Wahlström, J. (2005) ‘Ergonomics, musculoskeletal disorders and computer work,’ Occupational Medicine, 55(3), pp. 168–176. [CrossRef]

- Raguseo, E. , Gastaldi, L. and Neirotti, P. (2016) ‘Smart work,’ Evidence-based HRM a Global Forum for Empirical Scholarship, 4(3), pp. 240–256. [CrossRef]

- Pathak, N. , Tariq, M., De, S., & Sikora, A. (2021). Analysis of student mastery of anticipated learning outcomes during a BlendFlex STEM CURE using a combination of self-reported and empirical analysis [Conference Presentation]. Biology Faculty Proceedings, Presentations, Speeches, Lectures, Article 433. https://nsuworks.nova.edu/cnso_bio_facpres/433.

- Holmes, E.A.; et al. (2020) Multidisciplinary research priorities for the COVID-19 pandemic: a call for action for mental health science, The Lancet Psychiatry, 7(6), pp. 547–560. [CrossRef]

- Buomprisco, G. et al. (2021) Health and Telework: New Challenges after COVID-19 Pandemic, European Journal of Environment and Public Health, 5(2), p. em0073. [CrossRef]

- Adorsu-Djentuh, F. Y. (2013). Ghana, A Nation of Noise Makers. Ghana Herald. Retrieved , 2013, from http://www.ghanaherald.com/ghana-a-nation-of-noise-makers/.

- E.O, A., Agyemang A, A.- and P.O., T. (2017) ‘Noise pollution at Ghanaian social gatherings: The case of the Kumasi metropolis’, International Journal of Engineering Research and Applications, 07(07), pp. 20–27. [CrossRef]

- Geravandi, S. , Takdastan, A., Zallaghi, E., Niri, M. V., Mohammadi, M. J., Saki, H., & Naiemabadi, A. (2015). Noise pollution and health effects. Jundishapur Journal of Health Sciences, 7(1).

- Asumeng, M. , Asamani, L., Afful, J. and Agyemang, C.B., 2015. Occupational safety and health issues in Ghana: strategies for improving employee safety and health at workplace. International Journal of Business and Management Review, 3(9), pp.60-79.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).