1. Introduction

1.1. Definition and Importance

Medication adherence, or the degree to which patients follow a prescribed medication regimen, was declared “a problem of striking magnitude” by the World Health Organization (WHO) in 2003 [

1].An estimated 50% or fewer US adults adhere to medication guidelines, contributing to as many as 125,000 deaths and between 33% to 69% of hospital admissions annually [

2,

3,

4].The problem is growing, with medication nonadherence increasing across all age, sex, and racial groups [

5].

The WHO states that enhancing the efficacy of medication adherence interventions could have a considerably greater impact on population health than advancements in any specific medical treatments [

6]. With more medications taken at home than in hospitals and clinics combined, better home medication management may be critical to improving medication adherence [

7].

1.2. Medication Adherence

Barriers to medication adherence include medication cost, access to pharmacies, low health literacy, and patient-prescriber relationships [

8,

9,

10,

11,

12].Adherence can be influenced by factors that evolve as a patient progresses through different medication-taking phases [

13].The Ascertaining Barriers to Compliance (ABC) taxonomy identifies the stages of adherence as (1) initiation, the consumption of the first dose of a prescribed medication, (2) implementation, adherence to the prescribed dosing regimen from initiation until the last dose of the medication, and (3) discontinuation, which is cessation for any reason [

14]. The taxonomy further includes intentional and unintentional nonadherence to depict the complex nature of adherence [

15]. A common unintentional reason for nonadherence is forgetfulness [

16].

Throughout the stages of the medication lifecycle, healthcare providers have multiple opportunities to offer guidance to patients to establish or improve medication management practices. Given their in-depth knowledge of patients and the trust patients place in them, they are arguably among the best sources for this guidance [

17,

18]. Interventions to improve adherence also include pharmacist counseling, which includes the promotion of safe and appropriate use of medications and can even include home visits to provide tailored guidance on medication regimens [

19,

20,

21]. However, opportunities for patients to receive guidance are limited due to restrictions on provider time and intervention cost. Guidance can also come from family and friends. A qualitative analysis suggested that leveraging social contacts to engage patients in the routine aspects of purchasing and administering medication may effectively promote medication adherence [

22]. For family and friends to be helpful necessitates prior experience with adherence and comfort with and availability for medication communication.

Most often, patients are on their own to devise and implement home medication management practices, encompassing where and how to store medication, how to develop routines, and how to select containers, devices, or apps to aid with adherence. Determining optimal medication storage locations is an understudied area [

23]. Current research and patient guidelines related to storage focus on safety, including safe storage of medication when there are children or pets in the home [

13]; avoiding heat, humidity, and light that affect medication stability [

24]; preventing medication error [

14]; and reducing the risk of medication misuse due to poor medication management [

15].

We describe our efforts to identify and categorize home medication management practices as a step towards developing interventions to improve medication adherence in the home [

29]. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study that identifies commonly used home storage locations and reports on which locations are associated with medication adherence.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Sample

Given the exploratory nature of this study, we designed a survey to learn about home medication management. Data were collected via participant self-report through an online survey that was administered in English using Google Forms, an online survey platform that uses data encryption and advanced malware protection to protect user responses [

30]. The survey was developed by the Digital Health Research Group at Tufts University School of Medicine and deployed between November 18 and December 14, 2021. Participants were recruited using social media platforms including Twitter, LinkedIn, Facebook, and Instagram, and through the electronic mailing list at Tufts University’s Osher Lifelong Learning Institute. Eligible participants were 18 years of age or older and had access to an internet-enabled electronic device. Those who completed the survey were eligible to win a

$25 Amazon gift card by random draw. The Tufts University Health Sciences Institutional Review Board reviewed and approved all study protocols.

2.2. Procedures

A total of 1,966 survey responses were collected. Of those, 1,673 (85%) responses were deemed valid after screening for exclusion criteria (n=293, 15%). Responses were dropped if they had any of the following qualities: consecutive sets of identical responses reported at the same time (n=132); suspicious responses including identical open-text responses from the same day (n=83); non-English responses (n=59); or responses reported using an abnormal email address containing long strings of numbers, which were suspected to be fraudulently generated (n=19).

2.3. Measures

Items included in our survey were designed to learn about respondents’ experiences with management of their medication in the home. Multiple choice, 5-point Likert scale, and free-text open-ended questions were used to collect participant experiences related to medication storage locations, self-reported medication adherence, perceived importance of adherence, and demographic variables.

2.4. Demographic Variables

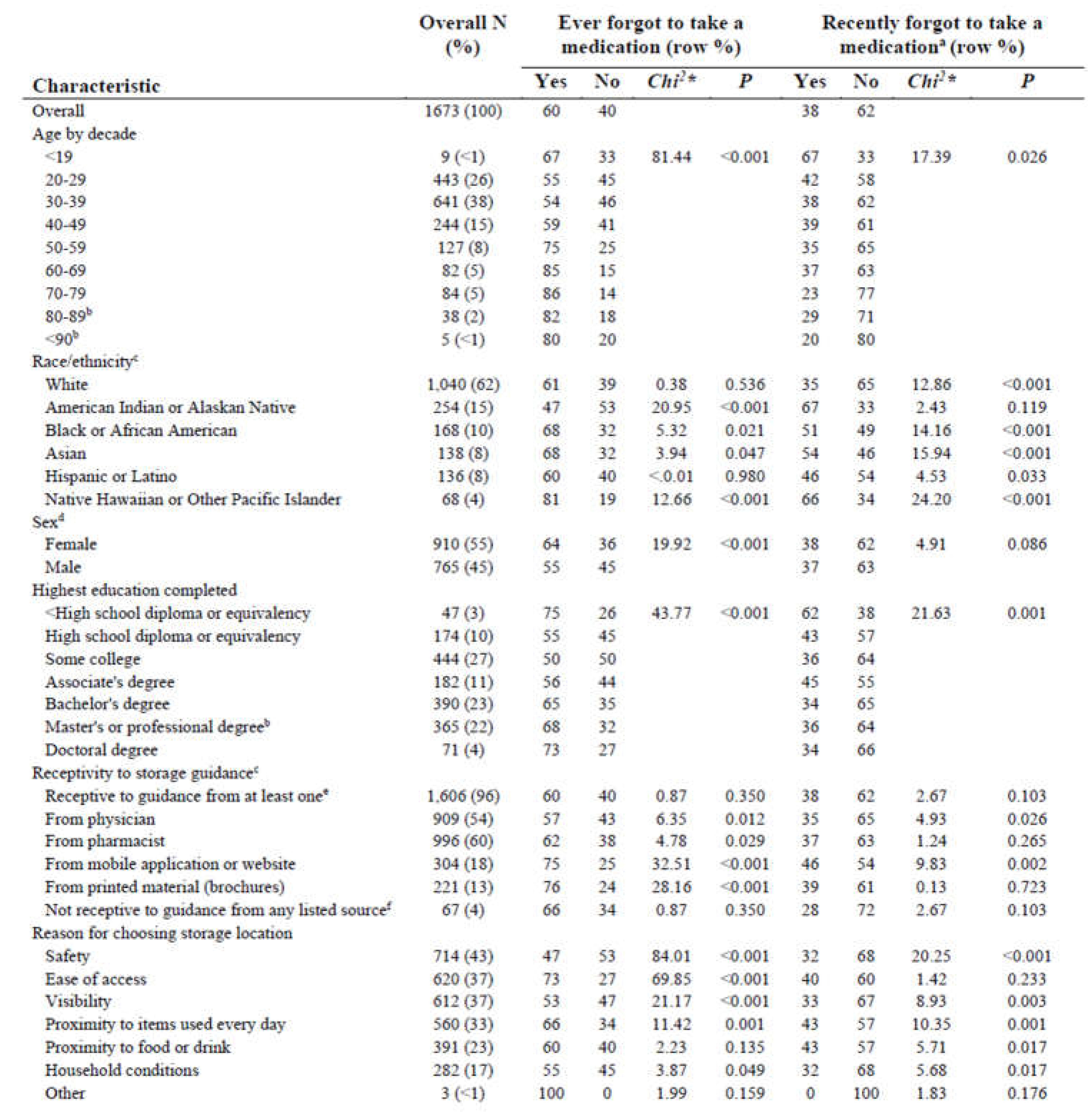

Data were collected pertaining to age, race and ethnicity, sex, and highest level of education completed. The demographic distribution of the sample can be seen in

Table 1. Most respondents (65%) were between the ages of 20 and 39 years, and a little over half (55%) were female. Most respondents were White (62%) and most (87%) had at least some college coursework experience.

Table 1.

Sample characteristics by self-reported adherence (n = 1673).

Table 1.

Sample characteristics by self-reported adherence (n = 1673).

2.5. Medication Storage Location

The question, “Where in your home do you store your prescriptions that you take on a regular basis?” was used to learn where respondents stored their medications that they took regularly. Because multiple locations might be used, respondents could select one or more locations from the list of options, which were: “Kitchen table,” “Kitchen cabinet,” “Kitchen counter,” “Kitchen drawer,” “In the refrigerator,” “On the bathroom vanity,” “In the vanity drawer or cabinet,” “Bathroom medicine cabinet,” “On top of the bedroom nightstand,” “In the nightstand drawer,” “Desk,” “Dining room table,” “Backpack, purse, or bag,”, “Closet”, and an open-text selection for unlisted locations. Open-text responses were categorized indicating use of already existing values via consensus coding to promote interrater reliability.

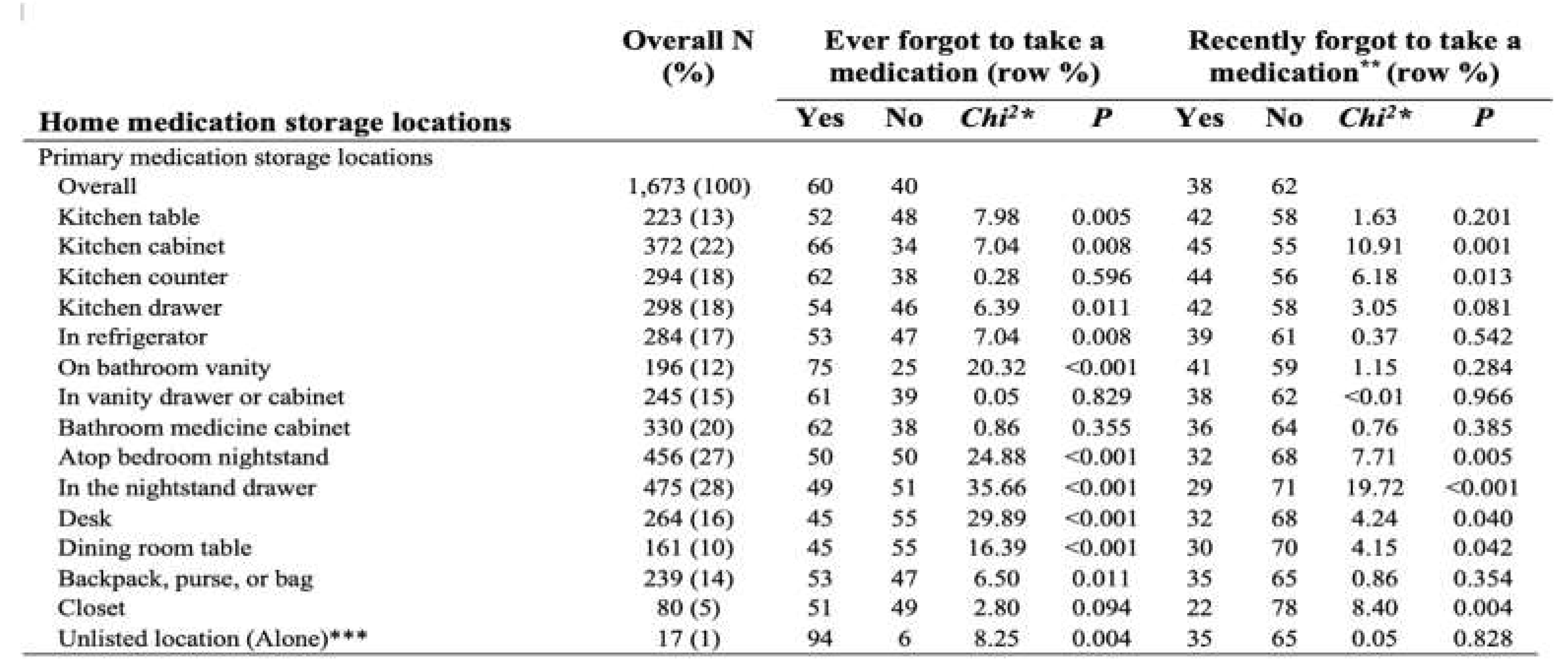

Table 2 displays the storage selection distribution for our sample.

Table 2.

Home medication storage by self-reported adherence (n= 1,673).

Table 2.

Home medication storage by self-reported adherence (n= 1,673).

We also assessed where respondents stored medications that they didn’t take regularly, asking, “Where in your home do you store medications other than the ones that you take on a regular basis (such as over-the-counter medications, an extra supply of your medications, vitamins etc.)?” Respondents could select from the same options provided above.

2.6. Analysis

We assessed relative frequencies for all sample characteristics and variables listed in our Measures subsection. Bivariate analyses were performed for medication storage locations currently in use by respondents, perceived importance of medication adherence, and variables indicating adherent behavior to medications taken regularly. Bivariate analyses included chi2 tests of homogeneity of proportions and bivariate logistic regression models.

3. Results

3.1. Sample Characteristics

Of the 1,673 total respondents, respondents ranged from 18 to over 90 years old with most (65%) between the ages of 20 and 39 years, a majority self-identified as White (62%), and over half (55%) female. Most (87%) had at least some college coursework experience with 45%) identified as having obtained a bachelor’s, master’s, or professional degree (

Table 1).

3.2. Receptivity to Storage Guidance

Over 1,600 respondents (N=1,606, 96%) reported that they would be receptive to guidance on medication storage, with more than half (54%) saying that they would be open to receiving guidance if it was from a physician. More respondents (60%) said that they would be receptive to guidance from a pharmacist. Fewer said that they would be open to receiving guidance from a mobile application or website (18%), and less said that they would be receptive to printed material, such as brochures (13%). Nearly two-thirds (65%) of those who reported being receptive to guidance from a physician said that they had not recently forgotten to take a medication (P=0.026), while 54% of those who were open to guidance from a mobile application or website self-reported that they hadn’t recently forgotten to take a medication (P=0.002).

3.3. Storage Location

The most common reason respondents chose their medication storage locations was found to be related to self-reported medication adherence. The majority of those who chose a storage location due to safety (P<0.001), visibility (P=0.003), proximity to items used daily (P=0.001), proximity to food or drink (P=0.017), and household conditions (P=0.017) reported that they hadn’t recently forgotten to take their medication. Those who chose safety were also less likely to report ever forgetting to take their medication (P<0.001).

The most common home storage location for primary medications was in nightstand drawers (N=475, 28%) followed closely by atop bedroom nightstands (N=456, 27%). Other common storage locations for primary medications were kitchen cabinets (N=372, 22%) and bathroom medicine cabinets (N=330, 20%). Among these commonly reported storage locations, atop bedroom nightstands (P=0.005), nightstand drawers (P<0.001), and kitchen cabinets (P= 0.001), significantly fewer respondents reported recently forgetting to take their medication. Other storage locations for primary medications that had significantly fewer respondents recently forget to take their medication included the kitchen counter (P=0.013), desk (P=0.040), dining room table (P=0.042), and closet (P=0.004).

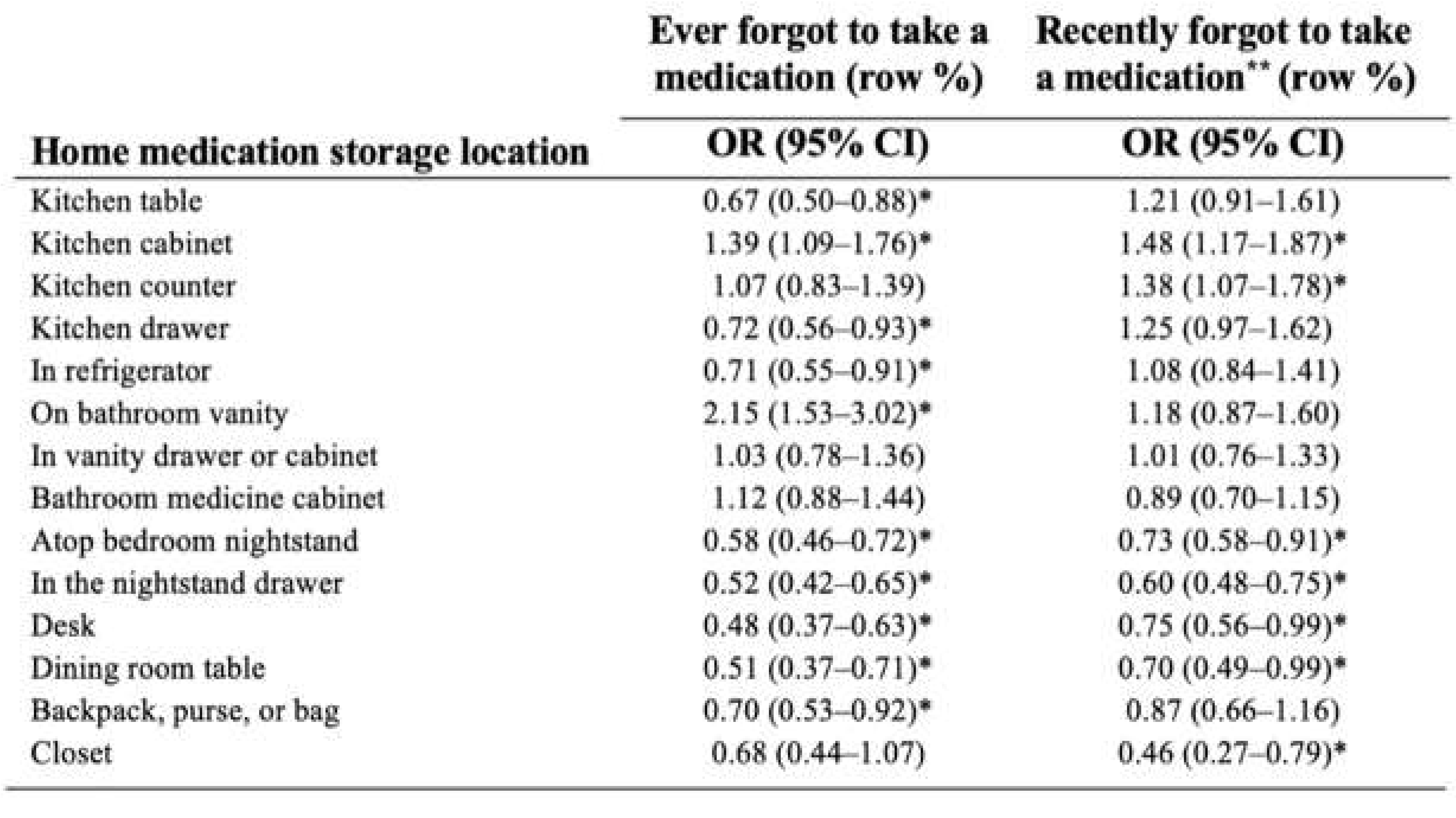

Bivariate Analyses

Medication Storage Location and Medication Adherence

Many home medication storage locations were significantly associated with decreased odds of having ever forgotten to take a medication, including kitchen tables (OR: 0.67, 95% CI: 0.50–0.88), kitchen drawers (OR: 0.72, 95% CI: 0.56–0.93), in the refrigerator (OR: 0.71, 95% CI: 0.55–0.91), atop the bedroom nightstand (OR: 0.58, 95%CI: 0.46–0.72), in the nightstand drawer (OR: 0.52, 95% CI: 0.42–0.65), desks (OR: 0.48, 95% CI: 0.37–0.63), dining room tables (OR: 0.51, 95% CI: 0.37–0.71) and backpack, purse, or bag (OR: 0.70, 95% CI: 0.53–0.92). Two home medication storage locations were significantly associated with increased odds of having ever forgotten to take a medication: kitchen cabinets (OR: 1.39, 95% CI: 1.09–1.76) and bathroom vanities (OR: 2.15, 95% CI: 1.53–3.02).

Five home medication storage locations were significantly associated with having decreased odds of forgetting to take a medication within the two weeks prior to survey: atop bedroom nightstand (OR: 0.73, 95% CI: 0.58–0.91), in the nightstand drawer (OR: 0.60, 95% CI: 0.48–0.75), desk (OR: 0.75, 95% CI: 0.56–0.99), on the dining room table (OR: 0.70, 95% CI: 0.49–0.99), and in the closet (OR: 0.46, 95% CI: 0.27–0.79). Two locations were significantly associated with increased odds of forgetting to take a medication in the two weeks prior to survey: kitchen cabinets (OR: 1.48, 95% CI: 1.17–1.87) and kitchen counters (OR: 1.38, 95% CI: 1.17–1.78) (

Table 3).

Table 3.

Bivariate associations between home medication storage location and self-reported medication adherence.

Table 3.

Bivariate associations between home medication storage location and self-reported medication adherence.

4. Discussion

4.1. Receptivity to Storage Guidance

More than half (54%) of the sample reported that they would be open to receiving storage guidance from a physician, and nearly two-thirds (65%) of those respondents said that they had not recently forgotten to take a medication. Changes to the health system resulting from the COVID-19 pandemic, such as shorter doctor’s visits and increased mail-order medications, may pose a barrier to the guidance that patients receive. While storage guidance may be something respondents want and are receptive to, there are fewer opportunities for patients to receive this type of counseling, which could have an impact on medication adherence.

4.2. Storage Location

Those who chose a storage location due to safety (43% of the sample) reported the highest rate of medication adherence (for both past and recent categories). Visibility was also found to be associated with self-reported adherence, with 67% of those who said that they chose their medication storage location for visibility purposes reported that they hadn’t recently forgotten to take a medication.

The two most significant goals we had for this study were to determine which storage locations people use, and to learn if any of those locations were associated with adherence. Nightstands were the most common location for respondents to store their medications. Half of the sample reported that they kept their medication atop their bedroom nightstand, and an additional 28% reported storing their prescription inside of their nightstand drawer. Among these commonly reported locations, both atop bedroom nightstands and within nightstand drawers were found to be significantly associated with recent medication adherence. These findings might inform the guidance patients are given on where to store their medication and may inform the design of devices tailored for specific storage locations. The characteristics of the location—such as whether a storage location is in a personal or a shared space, its visibility, and ease of access—should be incorporated into counseling on home medication management.

5. Future Directions

There are numerous opportunities for patients to receive guidance on medication storage. Conversations with a physician, interactions with a pharmacist, or advice at home can all impact the way an individual takes their medications.

5.1. Role of Physicians

With over half of respondents indicating that they would be receptive to guidance from their physician (54%), office visits are another place where discussions around medication storage could occur. However, such information may be difficult to fit into an appointment that often already has limited time. Future research is needed to determine the source of guidance that would have the most impact on changing a patient’s medication storage location and whether this would affect adherence.

5.2. Role of Pharmacists

Most respondents (96%) indicated interest in receiving guidance about where to store their home medications. The majority (60%) said that they would be interested in receiving this guidance from a pharmacist. This data indicates the potential for interventions around changing the standard discourse between patients and pharmacists while picking up prescriptions. Paired with records indicating how often a patient is refilling their prescriptions, it may be possible to electronically identify individuals who are potentially prone to frequently missed medications. Future interventions could use these indicators to prompt a pharmacist to provide guidance about home medication storage. More research is needed to determine the plausibility of such an intervention and whether guidance from a pharmacist would increase adherence among patients over time. However, guidance may require a different format for the almost 25% of the US population who have their medications shipped directly to their home, thereby removing opportunities for face-to-face interaction between patients and pharmacists [

31].

5.3. Better Home and Device Design to Support Adherence

With the common use of nightstands for medication storage, additional consideration should be given to their design and how they might be built to support medication adherence. There are currently nightstands on the market with a spectrum of features designed to support various activities, such as working on one’s laptop in bed with an extendable lap desk while charging devices [

32], or optimally charging devices using a refrigerated drawer with multiple charging ports and a wireless charging station for smartphones [

33]. From a design perspective, there may be opportunities to further support medication adherence with the use of nightstands, which we found to be the most common place for respondents to store their medications and was significantly associated with recent medication adherence.

Other locations in the home could similarly be redesigned to accommodate pill containers and support medication adherence. Two examples are moving built-in medicine cabinets to a less warm and humid environment or designing a kitchen cabinet specifically for medication in the same ways spice cabinets are designed for visibility and ease of use as well as holding specific sized containers.

Understanding how and where patients store their medication could lead to the design of location-specific containers or devices in the same way that a desk lamp is different from a living room lamp. Many digital devices use auditory or visual cues to provide time-based reminders to patients to take their medication, but these devices only work if you can hear or see them [

34]. Such devices may need to be designed to accommodate individual patterns of home use so that notifications are heard or seen. Lastly, we are exploring reminder approaches other than time-based ones, specifically ones based on common routines, to provide reminders only when needed. Our motivation in doing so is to reduce notification fatigue. Our designs follow the same principle as car seatbelts, which emit an auditory notification if the seatbelt is unlatched when the ignition is turned on.

6. Limitations

Using social media as our primary survey dissemination method likely limited respondents to those active on the platforms we utilized. Another limitation was that the use of survey methodology was valuable for learning what respondents report, but it was not useful for determining the underlying complexities of choices and behaviors. We suspect that there is more to uncover about the relationship between medication adherence and the reason respondents chose their medication storage locations that we were unable to capture with the survey. For example, the reason an individual chooses their storage location may also be related to who they live with, which we did not account for when measuring the association between storage location and self-reported adherence. Despite this, we were able to identify significant bivariate relationships between several rationales respondents cited for their choice of medication storage locations and their self-reported adherence.

7. Conclusions

This survey uncovered where people store their medications and which of those locations are associated with medication adherence. Other important results center on how pills are stored, use of reminders, receptivity to guidance from a physician or pharmacist, and factors that influenced a patient to choose a medication storage location. Ongoing research will be informed by and built on these results. To explore some of these results in more depth, we conducted a follow-up study which utilized in-depth interviews as the primary study method [

35]. The interview methodology provided deeper insights into the complex nature of the myriad of decisions patients make and allows us to further explain some of the associations between medication storage locations and adherent behaviors. The survey results themselves may lead to the design of interventions for healthcare professionals to provide better adherence guidance to patients and innovative approaches to the design of homes, furnishings, or devices tailored for home medication management.

Author Contributions

LG initiated this research project, was responsible for developing and deploying the survey, and contributed to writing this paper. ES and MS performed the primary analysis for the survey results and contributed to writing this paper. BE and MS contributed to writing this paper. All authors approved the submitted version.

Funding

This research was funded in part by Tufts University through the Springboard Program, and in part by the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, National Institutes of Health, Award Number UL1TR002544. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by Tufts University Health Sciences Institutional Review Board in Boston, MA. Written informed consent for participation was not required for this study in accordance with the national legislation and the institutional requirements.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author, LG, upon reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

The authors offer their appreciation to the students at Tufts University School of Medicine who were instrumental in the discussions and literature reviews that led to this survey, most especially Avi Patel. The authors thank the students who contributed to the design of the survey and provided feedback on the paper, including Deelia Wang, In Baek, Justin Barton, Cheryl Croll, and Ricardo Boschetti.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- World Health Organization. Adherence to long-term therapies : evidence for action. Published online 2003. https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/42682.

- Bouwman L, Eeltink CM, Visser O, Janssen JJWM, Maaskant JM. Prevalence and associated factors of medication non-adherence in hematological-oncological patients in their home situation. BMC Cancer. 2017;17(1):739. [CrossRef]

- Stawarz K, Gardner B, Cox A, Blandford A. What influences the selection of contextual cues when starting a new routine behaviour? An exploratory study. BMC Psychol. 2020;8(1):29. [CrossRef]

- Desai R, Thakkar S, Fong HK, et al. Rising Trends in Medication Non-compliance and Associated Worsening Cardiovascular and Cerebrovascular Outcomes Among Hospitalized Adults Across the United States. Cureus. Published online August 14, 2019. [CrossRef]

- Investing in Medication Adherence Improves Health Outcomes and Health System Efficiency: Adherence to Medicines for Diabetes, Hypertension, and Hyperlipidaemia. Vol 105.; 2018. [CrossRef]

- Brown MT, Bussell JK. Medication Adherence: WHO Cares? Mayo Clin Proc. 2011;86(4):304-314. [CrossRef]

- Medicine I, Services BHC, Errors CIPM, et al. Preventing Medication Errors. National Academies Press; 2007.

- Kaul S, Avila JC, Mehta HB, Rodriguez AM, Kuo YF, Kirchhoff AC. Cost-related medication nonadherence among adolescent and young adult cancer survivors. Cancer. 2017;123(14):2726-2734. [CrossRef]

- McQuaid EL, Landier W. Cultural Issues in Medication Adherence: Disparities and Directions. J Gen Intern Med. 2018;33(2):200-206. [CrossRef]

- Park Y, Raza S, George A, Agrawal R, Ko J. The Effect of Formulary Restrictions on Patient and Payer Outcomes: A Systematic Literature Review. J Manag Care Spec Pharm. 2017;23(8):893-901. [CrossRef]

- Wroe, AL. Wroe AL. Intentional and unintentional nonadherence: a study of decision making. J Behav Med. 2002;25(4):355-372. [CrossRef]

- Lindquist LA, Go L, Fleisher J, Jain N, Friesema E, Baker DW. Relationship of health literacy to intentional and unintentional non-adherence of hospital discharge medications. J Gen Intern Med. 2012;27(2):173-178. [CrossRef]

- Aslani P, Schneider MP. Adherence: the journey of medication taking, are we there yet? Int J Clin Pharm. 2014;36(1):1-3. [CrossRef]

- Vrijens B, De Geest S, Hughes DA, et al. A new taxonomy for describing and defining adherence to medications: New taxonomy for adherence to medications. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2012;73(5):691-705. [CrossRef]

- Khan MU, Aslani P. Exploring factors influencing initiation, implementation and discontinuation of medications in adults with ADHD. Health Expect. 2021;24(S1):82-94. [CrossRef]

- Gadkari AS, McHorney CA. Unintentional non-adherence to chronic prescription medications: how unintentional is it really? BMC Health Serv Res. 2012;12:98. [CrossRef]

- 2023 Edelman Trust Barometer. Edelman. Accessed October 18, 2023. https://www.edelman.com/trust/2023/trust-barometer. 18 October.

- McHugh J. The Prescription of Trust-FINAL.pdf. Columbia University Mailman School of Public Health. Published January 11, 2022. Accessed October 22, 2023. https://d17f9hu9hnb3ar.cloudfront.net/s3fs-public/2022-01/The%20Prescription%20of%20Trust-FINAL.pdf.

- Pharmacist-Provided Medication Therapy Management in Medicaid.

- Papastergiou J, Luen M, Tencaliuc S, Li W, Van Den Bemt B, Houle S. Medication management issues identified during home medication reviews for ambulatory community pharmacy patients. Can Pharm J Rev Pharm Can. 2019;152(5):334-342. [CrossRef]

- Flanagan PS, Barns A. Current perspectives on pharmacist home visits: do we keep reinventing the wheel? Integr Pharm Res Pract. 2018;Volume 7:141-159. [CrossRef]

- Scheurer D, Choudhry N, Swanton KA, Matlin O, Shrank W. Association between different types of social support and medication adherence. Am J Manag Care. 2012;18(12):e461-467.

- Abstracts of the 26th Annual Meeting of ESPACOMP, the International Society for Medication Adherence, Berlin, Germany, 17–19 November 2022. Int J Clin Pharm. 2023;45(1):250-280. [CrossRef]

- Funk OG, Yung R, Arrighi S, Lee S. Medication Storage Appropriateness in US Households. Innov Pharm. 2021;12(2):10.24926/iip.v12i2.3822. [CrossRef]

- Deelia Wang, Lisa Gualtieri. Searching for Medication Adherence Devices. In: ; in press.

- Kini V, Ho PM. Interventions to Improve Medication Adherence: A Review. JAMA. 2018;320(23):2461-2473. [CrossRef]

- Choudhry NK, Krumme AA, Ercole PM, et al. Effect of Reminder Devices on Medication Adherence: The REMIND Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Intern Med. 2017;177(5):624. [CrossRef]

- Nguyen E, Bugno L, Kandah C, et al. Is There a Good App for That? Evaluating m-Health Apps for Strategies That Promote Pediatric Medication Adherence. Telemed J E-Health Off J Am Telemed Assoc. 2016;22(11):929-937. [CrossRef]

- Gualtieri, L, Wang, D. (2023) Hosting a Co-Design Workshop: Older Adults Ideate Medication Adherence Solutions. 27th Annual Meeting of ESPACOMP, the International Society for Medication Adherence, Budapest, Hungary, December 1, 2023. 1 December.

- Google Forms: Online Form Creator | Google Workspace. Accessed August 7, 2023. https://www.google.com/forms/about/. 7 August.

- Rupp, MT. Rupp MT. Attitudes of Medicare-Eligible Americans Toward Mail Service Pharmacy. J Manag Care Pharm. 2013;19(7):564-572. [CrossRef]

- Inbox Zero Evadna Manufactured Wood Nightstand & Reviews | Wayfair. Accessed August 7, 2023. https://www.wayfair.com/furniture/pdp/inbox-zero-evadna-185-tall-1-drawer-nightstand-in-white-w007843079.html. 7 August.

- Livtab Smart End Table with Fridge and Built-In Outlets & Reviews | Wayfair. Accessed August 7, 2023. https://www.wayfair.com/furniture/pdp/livtab-smart-end-table-with-fridge-and-built-in-outlets-cvta1002.html.

- Gualtieri L, Shaveet E, Estime B, Patel A. The role of home medication storage location in increasing medication adherence for middle-aged and older adults. Front Digit Health. 2022;4.

- Gualtieri L, Rigby M, Wang D., Mann E. Medication Management Strategies of Older Adults to Support Medication Adherence: Results from an Interview Study. Interact J Med Res. 2024 Jun 20. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).