Submitted:

31 July 2024

Posted:

05 August 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

1.1. Literature Review Geospatial and Temporal Patterns of Disasters

2. Methods

2.1. Hypothetical Framework

2.2. Data Collection and Preparation

2.2. Analyses

- Analysis of the geographical distribution of disasters by continents for the period from 1900 to 2024. This included calculating the total number and percentage of different types of disasters on each continent. The geographical distribution was analyzed to identify regions with the highest frequency of disasters and to determine the specific characteristics of disasters in those regions.

- Detailed analysis of the frequency of disasters by countries, including the identification of countries most affected by different types of disasters. The analysis included quantifying the number of events by country and assessing their impact on human and economic resources.

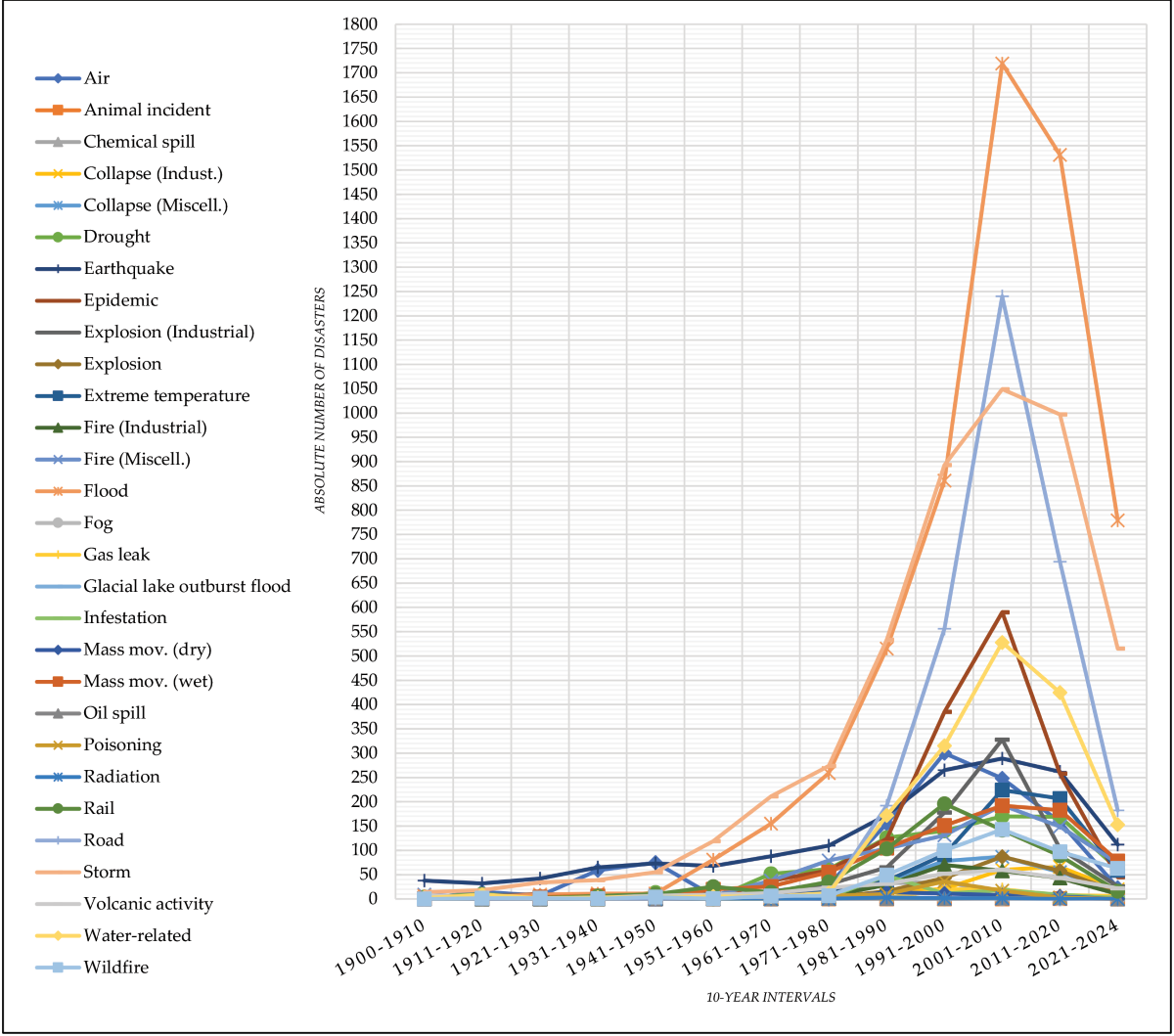

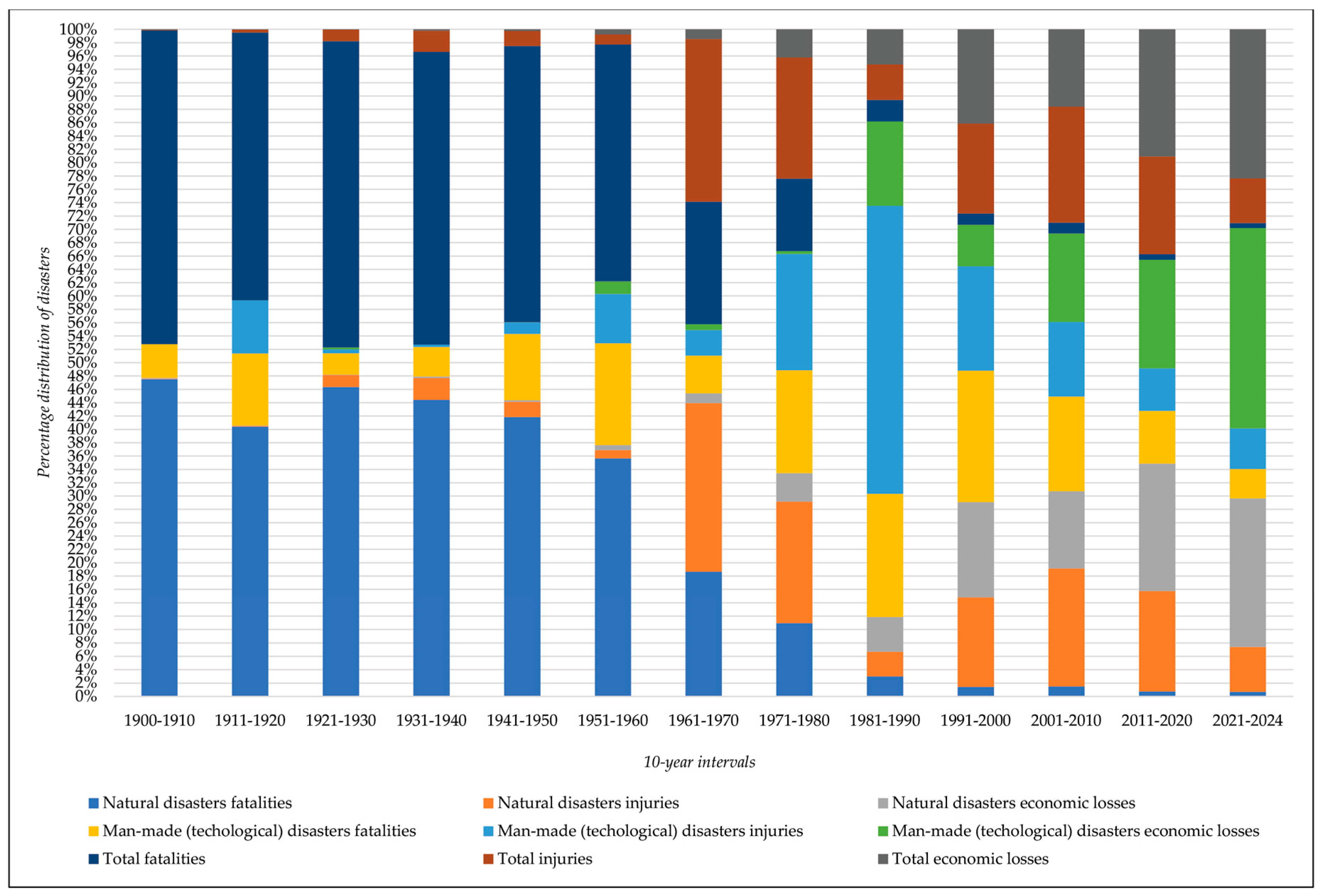

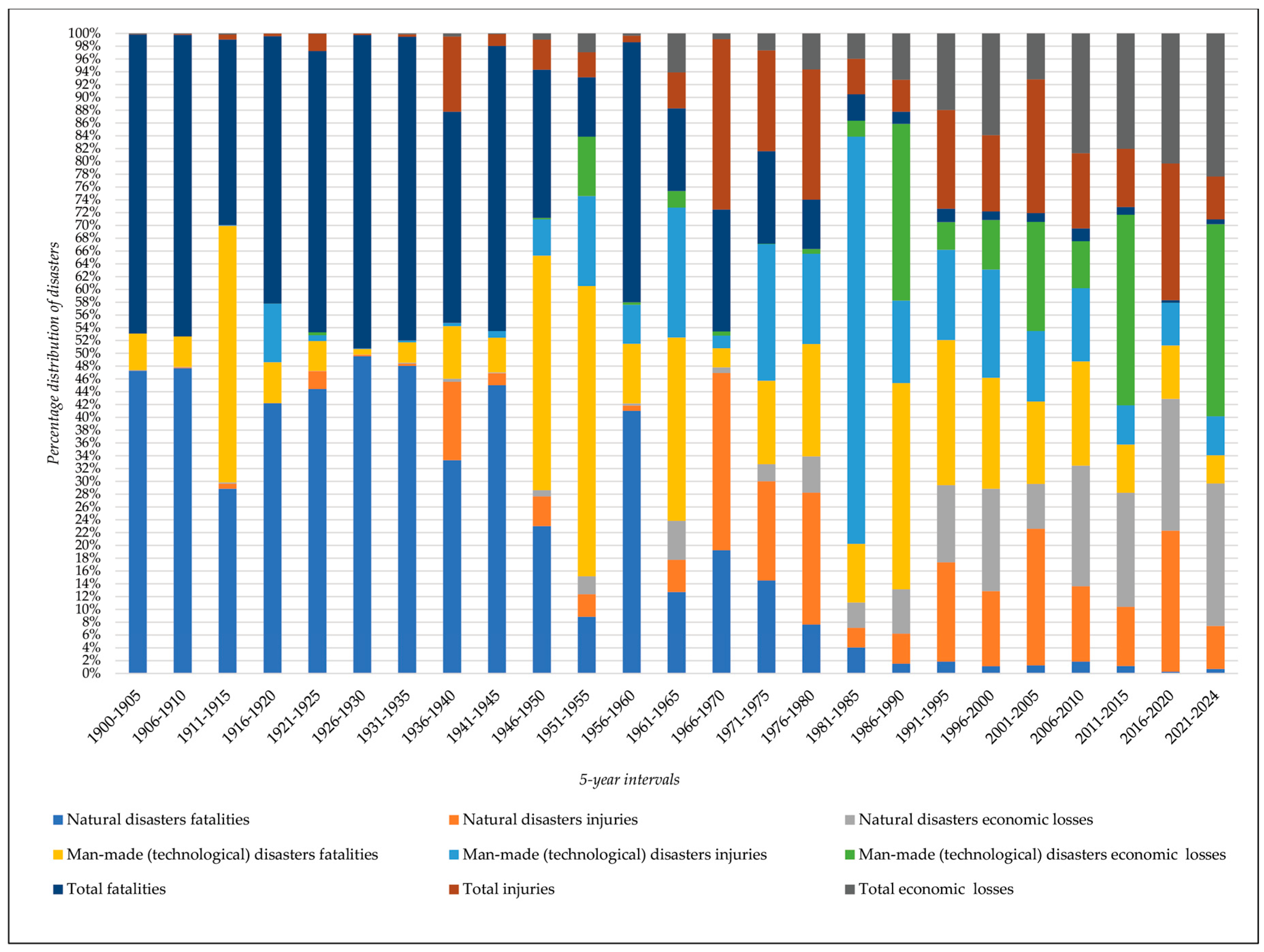

- Analysis of temporal trends in the frequency of natural and technological disasters in 10- and 5-year intervals. This analysis enabled the identification of changes in the frequency and types of disasters over time, as well as the identification of periods with the highest disaster frequency.

3. Results

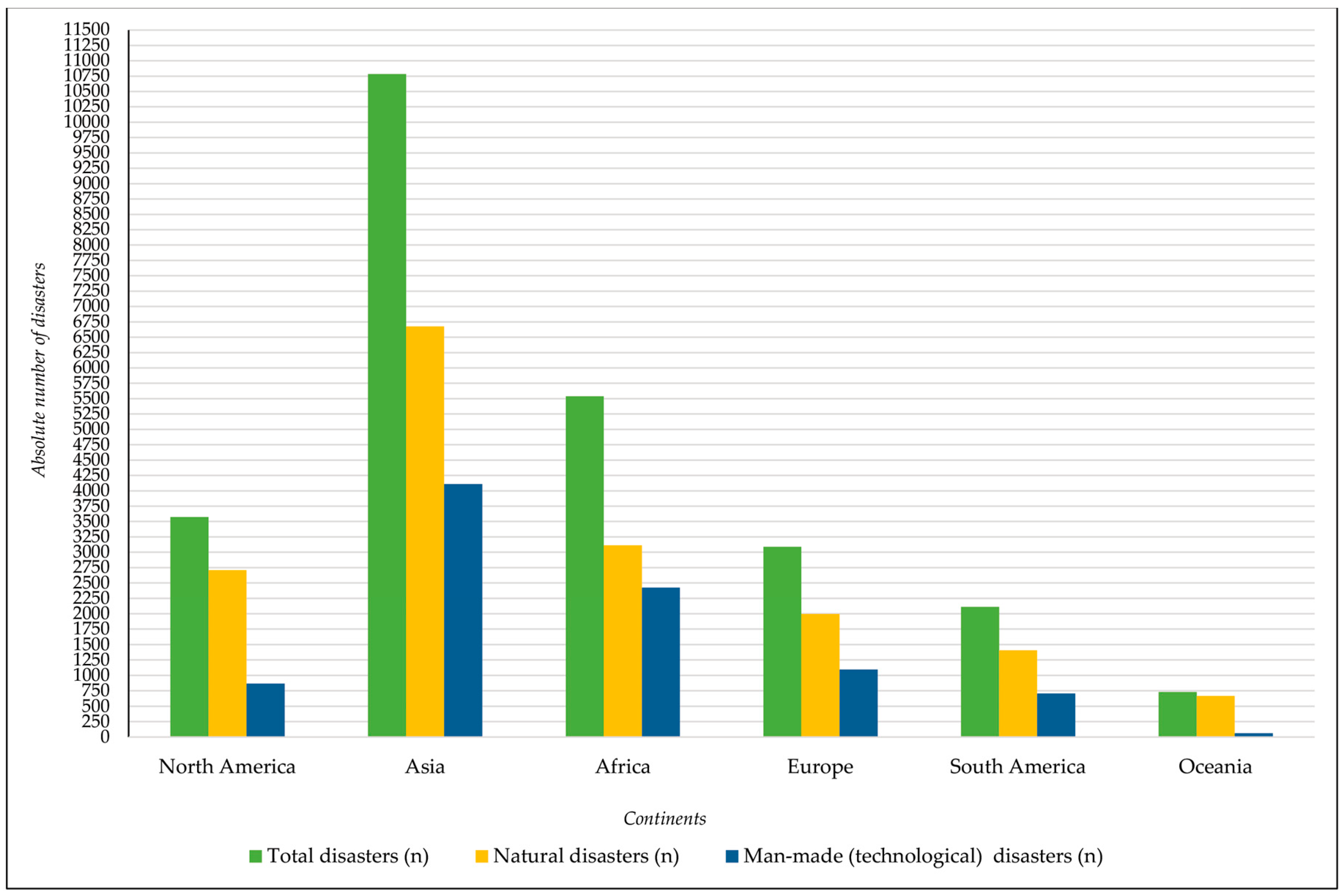

3.1. Geographical Distribution of Natural and Man-Made (Technological) Disasters

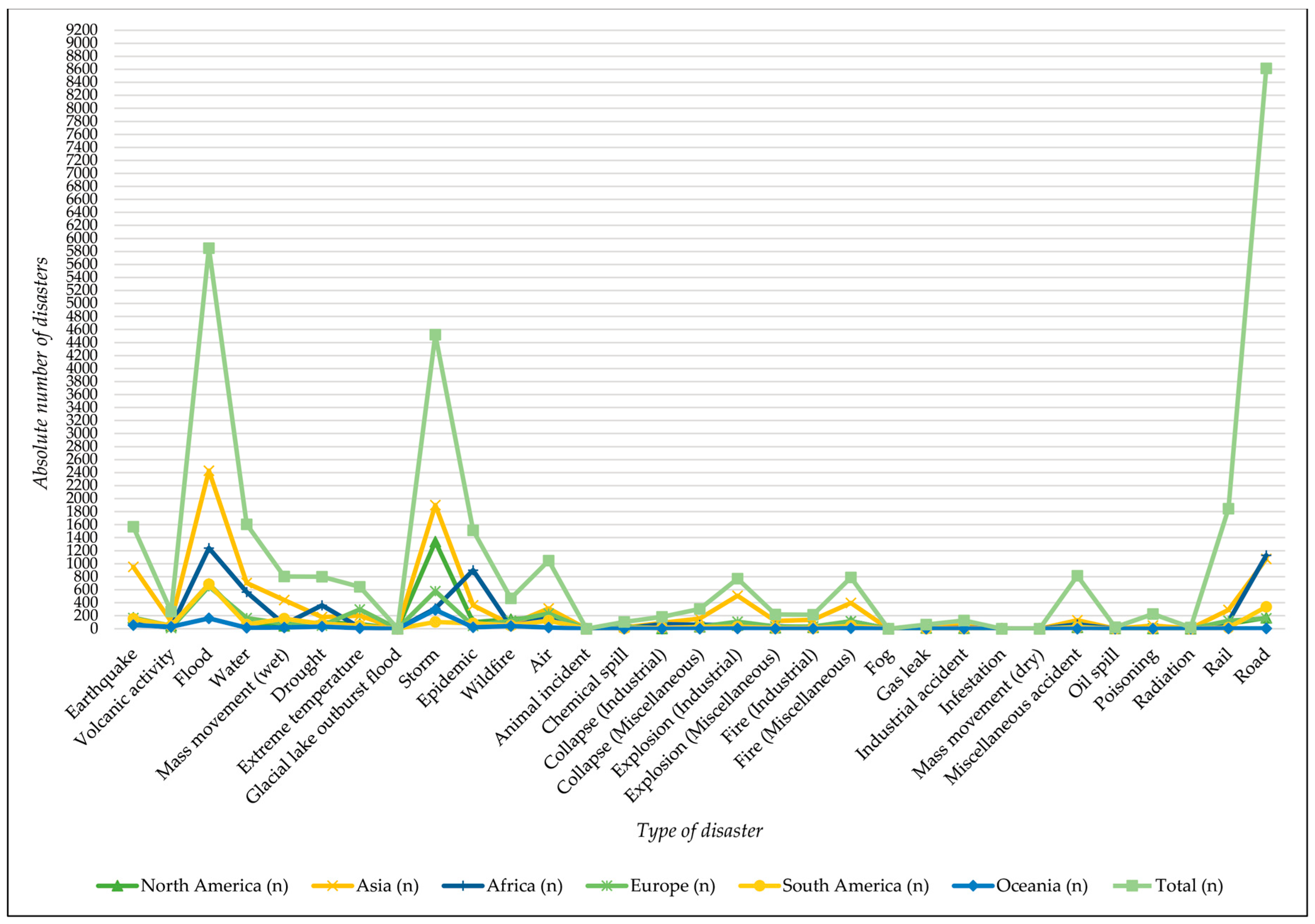

3.1.1. In-Depth Analysis of Disaster Distribution by Continent with Comprehensive Supporting Data

- a)

- Earthquakes: Asia recorded the highest number of earthquake events with 951 events (3.68% of the total), followed by Europe with 163 events (0.63%) and North America with 167 events (0.65%). Oceania experienced the fewest earthquakes, with 57 events (0.22%);

- b)

- Volcanic activity: volcanic activity was most prevalent in Asia with 112 events (0.43%), while North America and South America each reported 45 events (0.17%). Europe had the least volcanic activity, with 11 events (0.04%);

- c)

- Floods: most frequent were in Asia, accounting for 2,429 events (9.40%), with significant occurrences in Africa (1,240 events, 4.80%) and North America (688 events, 2.66%). Oceania had the fewest flood events, with 160 events (0.62%);

- d)

- Water-related disasters1: these disasters were predominantly seen in Asia with 703 events (2.72%), followed by Africa with 561 events (2.17%) and North America with 99 events (0.38%). Oceania experienced the least, with 14 events (0.05%);

- e)

- Mass movement (wet): Asia experienced the most mass movement (wet) events, with 440 events (1.70%), followed by South America with 155 events (0.60%) and Africa with 68 events (0.26%). Oceania had the fewest, with 18 events (0.07%);

- f)

- Drought: Africa reported the highest number of droughts with 361 events (1.40%), while Asia had 179 events (0.69%) and North America had 102 events (0.39%). Oceania recorded the least, with 34 events (0.13%);

- g)

- Extreme temperature: Europe led in extreme temperature events with 297 events (1.15%), followed by Asia with 200 events (0.77%) and North America with 70 events (0.27%). Oceania had the fewest events, with 8 events (0.03%);

- h)

- Storms: North America experienced the most storms with 1,338 events (5.18%), followed by Asia with 1,899 events (7.35%) and Europe with 576 events (2.23%). South America reported the least, with 105 events (0.41%);

- i)

- Epidemics: most common were in Africa with 899 events (3.48%), followed by Asia with 361 events (1.40%) and North America with 100 events (0.39%). Oceania recorded the fewest, with 24 events (0.09%);

- j)

- Wildfires: North America led in wildfire events with 145 events (0.56%), followed by Europe with 123 events (0.48%) and South America with 49 events (0.19%). Asia had the fewest wildfires, with 69 events (0.27%).

- a)

- Air disasters: Asia reported the highest number of air disaster events with 312 events (1.21%), followed by Europe with 233 events (0.90%) and North America with 187 events (0.72%). Oceania had the fewest, with 21 events (0.08%);

- b)

- Chemical spills: North America recorded the most chemical spill events with 47 events (0.18%), while Asia reported 20 events (0.08%). Oceania had the least, with 1 incident (0.00%);

- c)

- Industrial and miscellaneous collapses: Asia led in industrial collapses with 88 events (0.34%) and miscellaneous collapses with 156 events (0.60%). Africa followed with 70 industrial collapses (0.27%) and 61 miscellaneous collapses (0.24%);

- d)

- Explosions: industrial explosions were most frequent in Asia with 509 events (1.97%), while miscellaneous explosions were also highest in Asia with 118 events (0.46%). Oceania had the fewest events in both categories, with 4 industrial explosions and 0 miscellaneous explosions;

- e)

- Fires (industrial and miscellaneous): North America recorded the most industrial fire events with 22 events (0.09%) and miscellaneous fire events with 111 events (0.43%). Oceania had the fewest events in both categories, with 0 industrial fires and 7 miscellaneous fires;

- f)

- Gas leaks and oil spills: gas leaks were most common in Asia with 38 events (0.15%), while oil spills were rare globally, with North America and Asia each reporting only a few events (3 and 2, respectively);

- g)

- Poisoning and radiation events: Poisoning events were highest in Asia with 50 events (0.19%), and radiation events were minimal worldwide, with North America and Asia each reporting only a few events (1 and 4, respectively);

- h)

- Rail and road disasters: road disasters were highly prevalent in Asia with 1,073 events (4.15%) and in Africa with 1,129 events (4.37%). Rail disasters were more common in Asia with 288 events (1.11%) and in Europe with 122 events (0.47%).

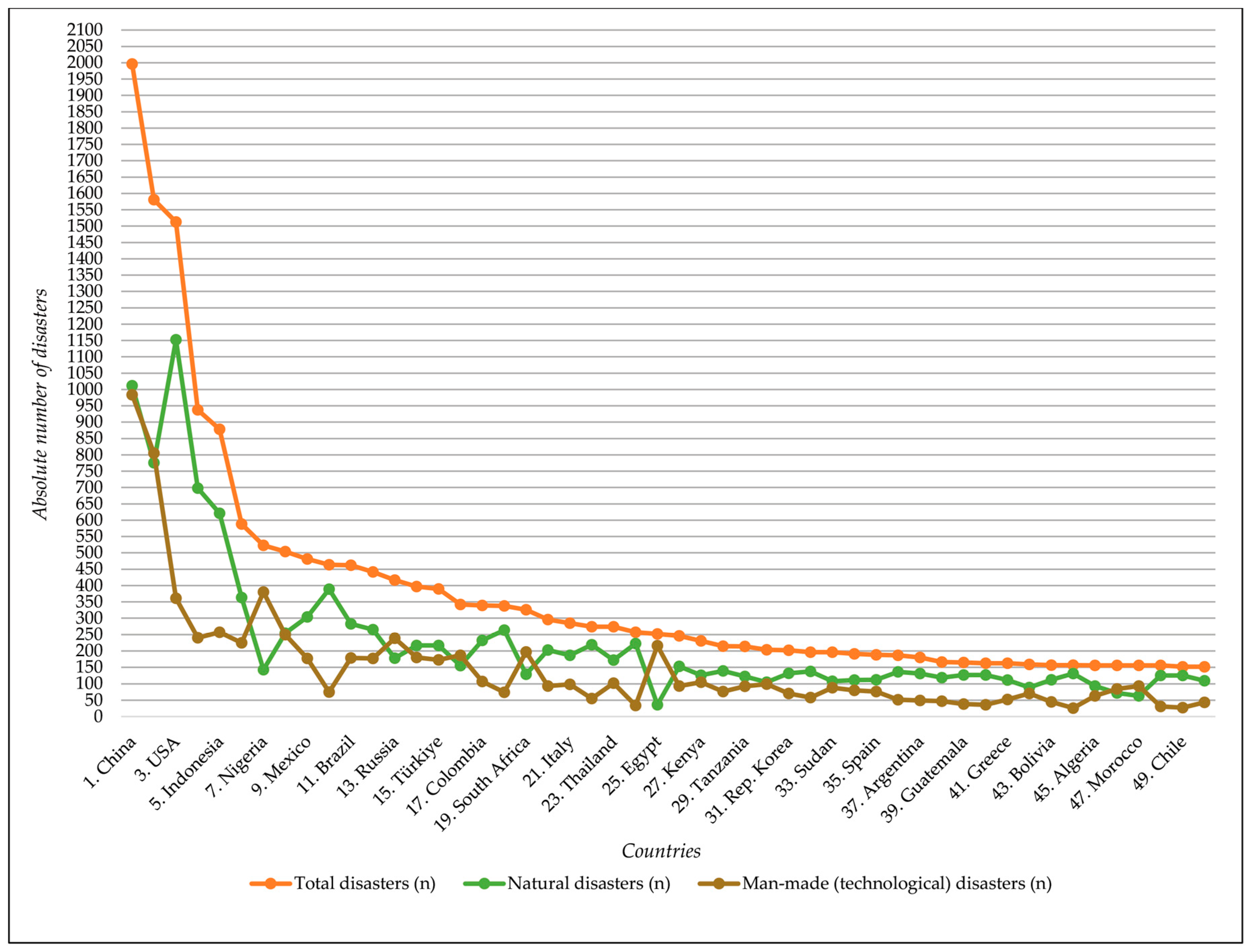

3.1.2. In-Depth Analysis of Disaster Distribution by Country with Comprehensive Supporting Data

- 1)

- China ranks first with a total of 1,996 disaster events, comprising 7.54% of the global total. Natural disasters make up 50.70% (1,012 events) of China's total, while man-made (technological) disasters account for 49.30% (984 events). The top five disasters in China include Industrial Accidents (15.08%), Storms (14.73%), Floods (14.53%), Droughts (14.28%), and Epidemics (14.23%);

- 2)

- India follows with 1,581 disaster events (5.97% of the global total). Natural disasters represent 49.08% (776 events), and man-made (technological) disasters 50.92% (805 events). The most frequent disasters are Epidemics (15.50%), Industrial Accidents (14.86%), Droughts (14.80%), Floods (14.29%), and Epidemics again (14.17%);

- 3)

- The USA is third with 1,513 disaster events (5.72% of the global total). Natural disasters dominate with 76.14% (1,152 events), and man-made (technological) disasters constitute 23.86% (361 events). The top disasters include Epidemics (15.27%), Industrial Accidents (14.87%), Droughts (14.47%), Floods (14.41%), and Wildfires (13.88%);

- 4)

- The Philippines ranks fourth with 938 disaster events (3.54% of the global total). Natural disasters account for 74.41% (698 events), and man-made (technological) disasters 25.59% (240 events). The leading disasters are Industrial Accidents (16.10%), Storms (14.71%), Droughts (14.50%), Epidemics (14.39%), and Wildfires (14.18%);

- 5)

- Indonesia is fifth with 878 disaster events (3.32% of the global total). Natural disasters make up 70.73% (621 events), while man-made (technological) disasters account for 29.27% (257 events). The most common disasters are Floods (16.40%), Earthquakes (15.15%), Droughts (15.03%), Epidemics (14.81%), and Wildfires (13.44%);

- 6)

- Bangladesh ranks sixth with 588 disaster events (2.22% of the global total). Natural disasters constitute 61.73% (363 events), and man-made (technological) disasters 38.27% (225 events). The top disasters include Floods (15.99%), Droughts (15.14%), Industrial Accidents (15.14%), Epidemics (14.97%), and Storms (13.27%);

- 7)

- Nigeria is seventh with 523 disaster events (1.98% of the global total). Man-made disasters are prevalent, accounting for 72.66% (380 events), while natural disasters make up 27.34% (143 events). The leading disasters are Wildfires (16.63%), Storms (16.44%), Industrial Accidents (14.72%), Epidemics (14.53%), and Droughts (13.38%);

- 8)

- Pakistan is eighth with 504 disaster events (1.90% of the global total). Natural disasters represent 50.40% (254 events), and man-made (technological) disasters 49.60% (250 events). The most frequent disasters include Floods (15.08%), Wildfires (15.08%), Storms (14.88%), Industrial Accidents (14.29%), and Epidemics (13.89%);

- 9)

- Mexico ranks ninth with 481 disaster events (1.82% of the global total). Natural disasters make up 63.20% (304 events), and man-made (technological) disasters 36.80% (177 events). The top disasters are Wildfires (17.88%), Epidemics (15.59%), Floods (15.18%), Droughts (13.51%), and Epidemics again (12.89%);

- 10)

- Japan is tenth with 464 disaster events (1.75% of the global total). Natural disasters are dominant, comprising 83.84% (389 events), while man-made (technological) disasters account for 16.16% (75 events). The leading disasters include Wildfires (17.24%), Earthquakes (15.73%), Storms (15.09%), Droughts (14.44%), and Industrial Accidents (13.79%).

3.2. Temporal Distribution of Natural and Man-Made (Technological) Disasters

3.2.1. Yearly and Monthly Trends in Occurrences of Natural and Man-Made Disasters

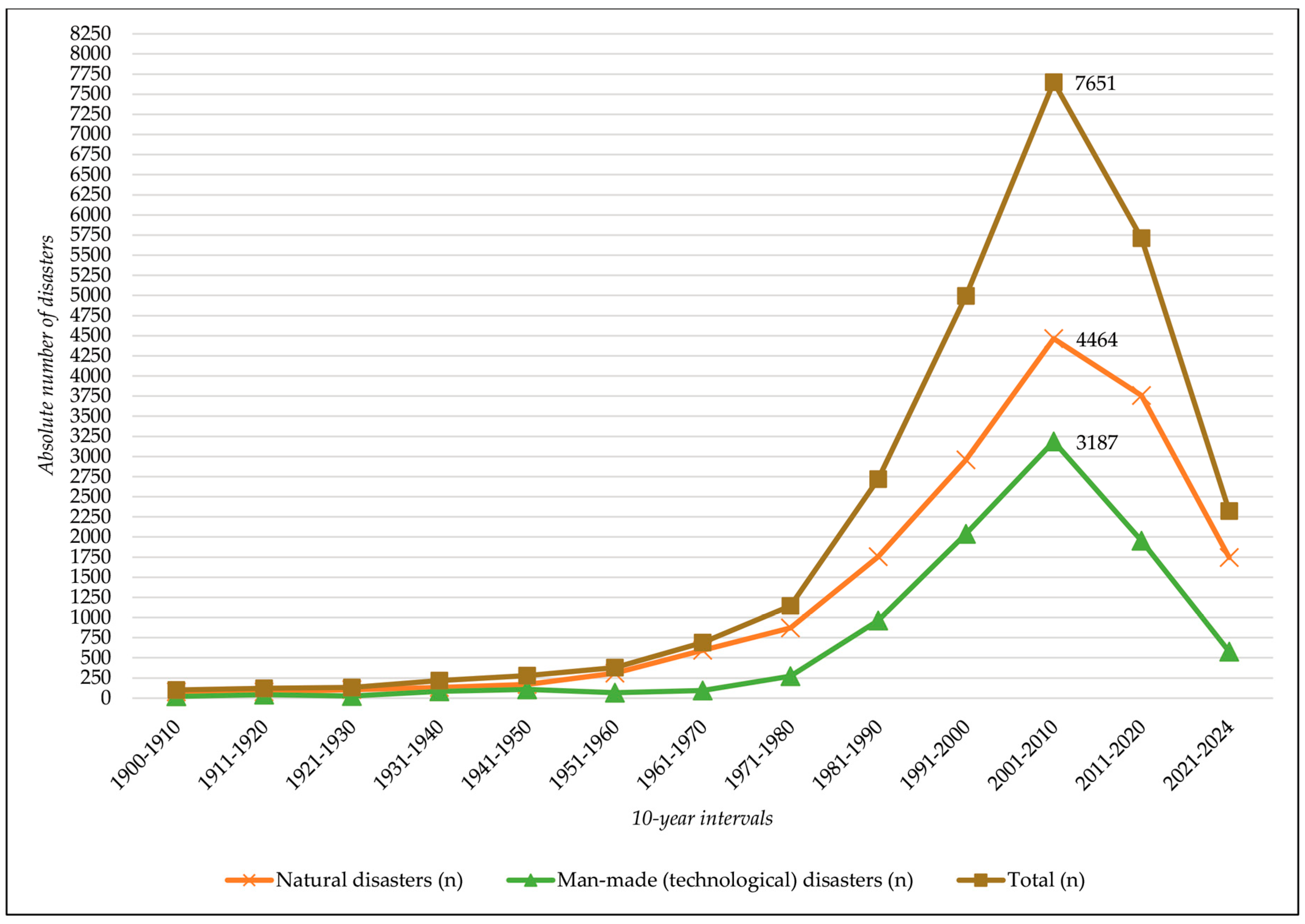

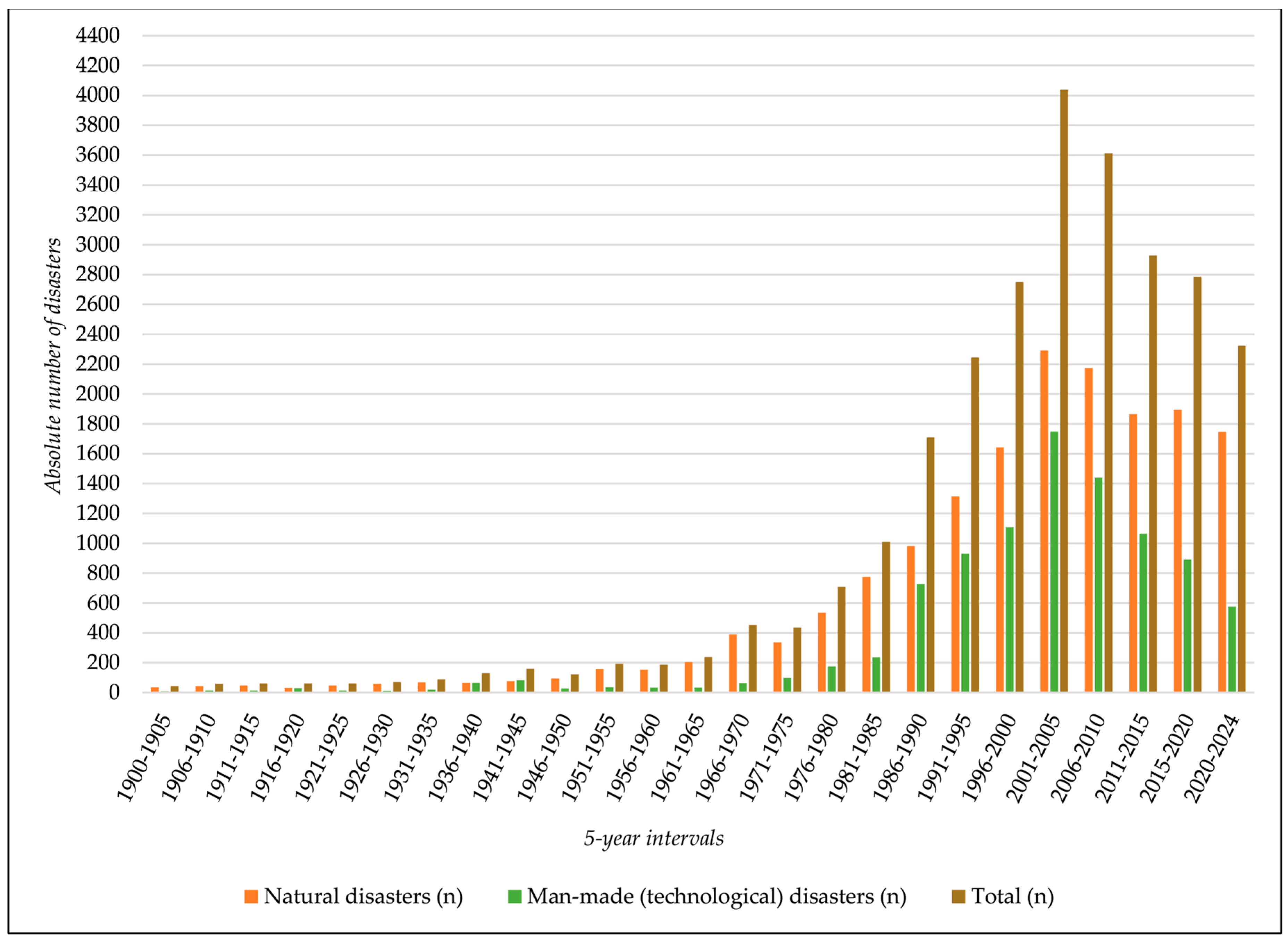

- a)

- From 1900-1910, there were 101 total disaster events, with natural disasters comprising 78.22% (79 events) and man-made (technological) disasters 21.78% (22 events). The overall trend was stable, with no significant change in the rate of disasters;

- b)

- Between 1911-1920, a total of 121 disaster events were recorded, showing an increase of 19.57% from the previous decade. Natural disasters made up 64.46% (78 events), while man-made (technological) disasters accounted for 35.54% (43 events). This decade marks the beginning of an upward trend in disaster events;

- c)

- During the 1921-1930 period, the number of disaster events increased to 132, a 7.40% rise from the previous decade. Natural disasters constituted 80.30% (106 events), and man-made (technological) disasters 19.70% (26 events). The upward trend continued;

- d)

- From 1931-1940, there were 217 disaster events, representing a significant increase of 42.20%. Natural disasters made up 61.29% (133 events), while man-made (technological) disasters accounted for 38.71% (84 events). This decade saw a substantial rise in the number of disasters;

- e)

- In the 1941-1950 decade, the number of disasters increased to 281, an 11.73% rise from the previous decade. Natural disasters comprised 60.85% (171 events), and man-made (technological) disasters 39.15% (110 events). The trend of increasing disaster events persisted;

- f)

- From 1950-1960, there were 378 disaster events, marking a 10.05% increase. Natural disasters accounted for 82.01% (310 events), while man-made (technological) disasters were 17.99% (68 events). This decade continued the upward trend;

- g)

- The 1961-1970 period saw the number of disasters rise to 690, a 13.59% increase. Natural disasters constituted 86.09% (594 events), and man-made (technological) disasters 13.91% (96 events). The trend of increasing disasters continued;

- h)

- Between 1970-1980, a total of 1,144 disaster events were recorded, a 6.10% rise from the previous decade. Natural disasters made up 76.14% (871 events), while man-made (technological) disasters accounted for 23.86% (273 events). The upward trend in disaster frequency persisted;

- i)

- From 1981-1990, the number of disasters significantly increased to 2,718, a 5.33% rise from the previous decade. Natural disasters constituted 64.57% (1,755 events), and man-made (technological) disasters 35.43% (963 events). This decade saw a substantial rise in disaster events;

- j)

- In the 1991-2000 period, there were 4,995 disaster events, a 1.71% increase. Natural disasters made up 59.20% (2,957 events), while man-made (technological) disasters were 40.80% (2,038 events). The trend of increasing disasters continued;

- k)

- From 2001-2010, the number of disasters rose to 7,651, a 0.70% increase. Natural disasters accounted for 58.35% (4,464 events), while man-made (technological) disasters were 41.65% (3,187 events). This decade continued the upward trend;

- l)

- Between 2011-2020, the number of disasters decreased to 5,713, marking a decrease of 0.44%. Natural disasters made up 65.78% (3,758 events), and man-made (technological) disasters 34.22% (1,955 events). This decade saw the beginning of a downward trend;

- m)

3.2.2. Yearly and Monthly Trends in Consequences of Natural and Man-Made Disasters

4. Discussion

5. Recommendations

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Cvetković, Vladimir, and Vanja Šišović. "Understanding the Sustainable Development of Community (Social) Disaster Resilience in Serbia: Demographic and Socio-Economic Impacts." Sustainability 16, no. 7 (2024): 2620. [CrossRef]

- Cvetković, Vladimir M., Goran Grozdanić, Miško Milanović, Slobodan Marković, and Tin Lukić. "Seismic Hazard Resilience in Montenegro: A Comprehensive Qualitative Analysis of Local Preparedness and Response Mechanisms." (2024).

- Cvetković, Vladimir. "Essential Tactics for Disaster Protection and Resque." Scientific-Professional Society for Disaster Risk Management, Belgrade, 2024.

- Cvetković, Vladimir, Neda Nikolić, and Tin Lukić. "Exploring Students' and Teachers' Insights on School-Based Disaster Risk Reduction and Safety: A Case Study of Western Morava Basin, Serbia." Safety 10, no. 2 (2024): 2024040472. [CrossRef]

- Tanasić, Jasmina, and Vladimir Cvetković. "The Efficiency of Disaster and Crisis Management Policy at the Local Level: Lessons from Serbia." Scientific-Professional Society for Disaster Risk Management, Belgrade, 2024.

- Cvetković, V. Disaster Risk Management. Belgrade: Scientific-Professional Society for Disaster Risk Management.

- UNISDR. "UNISDR, Terminology on Disaster Risk Terminology on Disaster Risk Reduction." 2017.

- Cvetkovic, Vladimir M., Nemanja Boškovic, and Adem Öcal. "Individual Citizens' Resilience to Disasters Caused by Floods: A Case Study of Belgrade." Academic Perspective Procedia 4, no. 2 (2021): 9-20. [CrossRef]

- Perić, Jovana, and Cvetković Vladimir. "Demographic, Socio-Economic and Phycological Perspective of Risk Perception from Disasters Caused by Floods: Case Study Belgrade." International Journal of Disaster Risk Management 1, no. 2 (2019).

- Cvetković, Vladimir, Paolo Tarolli, Giulia Roder, Aleksandar Ivanov, Kevin Ronan, Adem Ocam, and Rana Kutub. "Citizens Education About Floods: A Serbian Case Study." Paper presented at the VII International scientific conference Archibald Reiss days 2017.

- Cvetković, V., G. Roder, A. Öcal, P. Tarolli, and S. Dragićević. "The Role of Gender in Preparedness and Response Behaviors Towards Flood Risk in Serbia." International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 15, no. 12 (2018): 2761. [CrossRef]

- Iftikhar, A., and J. Iqbal. "The Factors Responsible for Urban Flooding in Karachi (a Case Study of Dha)." International Journal of Disaster Risk Management 5, no. 1 (2023): 81-103. [CrossRef]

- Starosta, D. "Raised under Bad Stars: Negotiating a Culture of Disaster Preparedness." International Journal of Disaster Risk Management 5, no. 2 (2023): 1-16. [CrossRef]

- Zareian, M. "Social Capitals and Earthquake: A Study of Different Districts of Tehran, Iran." International Journal of Disaster Risk Management 5, no. 2 (2023): 17-28. [CrossRef]

- Islam, F. "Anticipated Role of Bangladesh Police in Disaster Management Based on the Contribution of Bangladesh Police During the Pandemic Covid 19." International Journal of Disaster Risk Management 5, no. 2 (2023): 45-56. [CrossRef]

- Ulal, S. Saha S. Gupta S., and D. Karmakar. "Hazard Risk Evaluation of Covid-19: A Case Study." International Journal of Disaster Risk Management 5, no. 2 (2023): 81-101.

- El-Mougher, M. M., D. S. A. M. Abu Sharekh, M. R. F. Abu Ali, and D. E. A. A. M. Zuhud. "Risk Management of Gas Stations That Urban Expansion Crept into in the Gaza Strip." International Journal of Disaster Risk Management 5, no. 1 (2023): 13-27.

- Cvetković, Vladimir, Saša Romanić, and Hatidža Beriša. "Religion Influence on Disaster Risk Reduction: A Case Study of Serbia." International Journal of Disaster Risk Management 5, no. 1 (2023): 66-81. [CrossRef]

- Cvetković, Vladimir M., Aleksandar Dragašević, Darko Protić, Bojan Janković, Neda Nikolić, and Predrag Milošević. "Fire Safety Behavior Model for Residential Buildings: Implications for Disaster Risk Reduction." International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction (2022): 102981. [CrossRef]

- Mohammed, El-Mougher, and Jarour Maysaa. "International Experiences in Sheltering the Syrian Refugees in Germany and Turkey." International Journal of Disaster Risk Management 4, no. 1 (2022): 1-15.

- Sergey, Kachanov, and Nigmetov Gennadiy. "Methodology for the Risk Monitoring of Geological Hazards for Buildings and Structures." International Journal of Disaster Risk Management 4, no. 1 (2022): 41-49.

- Dukiya, Jehoshaphat Jaiye, and Oghenah Benjamine. "Building Resilience through Local and International Partnerships, Nigeria Experiences." International Journal of Disaster Risk Management 3, no. 2 (2021): 11-24.

- Cvetković, Vladimir M., Jasmina Tanasić, Adem Ocal, Želimir Kešetović, Neda Nikolić, and Aleksandar Dragašević. "Capacity Development of Local Self-Governments for Disaster Risk Management." International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 18, no. 19 (2021): 10406. [CrossRef]

- Thennavan, Edison, Ganapathy Ganapathy, S. Chandrasekaran, and Ajay %J International Journal of Disaster Risk Management Rajawat. "Probabilistic Rainfall Thresholds for Shallow Landslides Initiation – a Case Study from the Nilgiris District, Western Ghats, India." 2, no. 1 (2020).

- Kaur, Baljeet %J International Journal of Disaster Risk Management. "Disasters and Exemplified Vulnerabilities in a Cramped Public Health Infrastructure in India." 2, no. 1 (2020).

- Al-ramlawi, A, M El-Mougher, and M %J International Journal of Disaster Risk Management Al-Agha. "The Role of Al-Shifa Medical Complex Administration in Evacuation & Sheltering Planning." 2, no. 2 (2020).

- Chakma, U. K, A Hossain, K Islam, G. T Hasnat, and Kabir %J International Journal of Disaster Risk Management. "Water Crisis and Adaptation Strategies by Tribal Community: A Case Study in Baghaichari Upazila of Rangamati District in Bangladesh." 2, no. 2 (2020).

- Smith, Keith. Environmental Hazards: Assessing Risk and Reducing Disaster. New York: Routledge, 2013. [CrossRef]

- Mearns, Kathryn. "Chapter Four - Human Factors in the Chemical Process Industries." In Methods in Chemical Process Safety, edited by Faisal Khan, 149–200: Elsevier, 2017.

- Mannan, Sam, ed. Lees' Loss Prevention in the Process Industries (Third Edition). Burlington: Butterworth-Heinemann, 2005.

- Perrow, Charles. Normal Accidents: Living with High Risk Technologies: Princeton University Press, 2011.

- Han, Aiai, Wen Yuan, Wu Yuan, Jianwen Zhou, Xueyan Jian, Rong Wang, and Xinqi Gao. "Mining Spatial-Temporal Frequent Patterns of Natural Disasters in China Based on Textual Records." Information 15, no. 7 (2024): 372. [CrossRef]

- Ghosh, Chandan. "Gis and Geospatial Studies in Disaster Management." In International Handbook of Disaster Research, 701-08: Springer, 2023.

- Wang, Xiaowei. "Temporal Changes and Spatial Pattern Evolution of Marine Disasters in China from 1736 to 1911 Based on Geospatial Models: A Multiscalar Analysis." Journal of Coastal Research 108, no. SI (2020): 83-88. [CrossRef]

- Wei, Cuixia, Bing Guo, Hailing Zhang, Baomin Han, Xiangshen Li, Huihui Zhao, Yuefeng Lu, Chao Meng, Xiangzhi Huang, and Wenqian Zang. "Spatial–Temporal Evolution Pattern and Prediction Analysis of Flood Disasters in China in Recent 500 Years." Earth Science Informatics (2022): 1-15. [CrossRef]

- Rahmi, Rahmi, Hideo Joho, and Tetsuya Shirai. "An Analysis of Natural Disaster-Related Information-Seeking Behavior Using Temporal Stages." Journal of the Association for Information Science and Technology 70, no. 7 (2019): 715-28.

- Ruiz, Itxaso, Sérgio H. Faria, and Marc B. Neumann. "Climate Change Perception: Driving Forces and Their Interactions." Environmental science & policy 108 (2020): 112-20. [CrossRef]

- Sättele, Martina. Quantifying the Reliability and Effectiveness of Early Warning Systems for Natural Hazards. Technische Universität München, 2015.

- Shen, Guoqiang, and Seong Nam Hwang. "Spatial–Temporal Snapshots of Global Natural Disaster Impacts Revealed from Em-Dat for 1900-2015." Geomatics, Natural Hazards and Risk (2019). [CrossRef]

- Summers, J. K., A. Lamper, C. McMillion, and L. C. Harwell. "Observed Changes in the Frequency, Intensity, and Spatial Patterns of Nine Natural Hazards in the United States from 2000 to 2019." Sustainability 14, no. 7 (2022): 4158. [CrossRef]

- Tian, Cong-shan, Yi-ping Fang, Liang Emlyn Yang, and Chen-jia Zhang. "Spatial-Temporal Analysis of Community Resilience to Multi-Hazards in the Anning River Basin, Southwest China." International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction 39 (2019): 101144. [CrossRef]

- Vibhas, Sukhwani, Adu Gyamfi Bismark, Zhang Ruiyi, Mohammed AlHinai Anwaar, and Shaw %J International Journal of Disaster Risk Management Rajib. "Understanding the Barriers Restraining Effective Operation of Flood Early Warning Systems." 1, no. 2 (2019): In press.

- Wagner, Melissa A., Soe W. Myint, and Randall S. Cerveny. "Geospatial Assessment of Recovery Rates Following a Tornado Disaster." IEEE transactions on geoscience and remote sensing 50, no. 11 (2012): 4313-22. [CrossRef]

- Makwana, Nikunj. "Disaster and Its Impact on Mental Health: A Narrative Review." Journal of family medicine and primary care 8, no. 10 (2019): 3090-95. [CrossRef]

- Augusterfer, Eugene F., Richard F. Mollica, and James Lavelle. "Leveraging Technology in Post-Disaster Settings: The Role of Digital Health/Telemental Health." Current Psychiatry Reports 20 (2018): 1-8. [CrossRef]

- Stanley, Sharon A. R., Susan Bulecza, and Sameer Vali Gopalani. "Psychological Impact of Disasters on Communities." Annual Review of Nursing Research 30, no. 1 (2012): 89-123. [CrossRef]

- Buszta, Julia, Katarzyna Wójcik, Celso Augusto Guimarães Santos, Krystian Kozioł, and Kamil Maciuk. "Historical Analysis and Prediction of the Magnitude and Scale of Natural Disasters Globally." Resources 12, no. 9 (2023): 106. [CrossRef]

- Mijalković, Saša, and V. Cvetković. "Viktimizacija Ljudi Prirodnim Katastrofama: Geoprostorna I Vremenska Distribucija Posledica1." Temida 17, no. 4 (2014): 19-42.

- Neelakantan, R. "Geo-Environment and Related Disasters–a Geo-Spatial Approach." J. Environ. Nanotechnol 8, no. 1 (2019): 01-05.

- Zheng, Zhuo, Yanfei Zhong, Junjue Wang, Ailong Ma, and Liangpei Zhang. "Building Damage Assessment for Rapid Disaster Response with a Deep Object-Based Semantic Change Detection Framework: From Natural Disasters to Man-Made Disasters." Remote Sensing of Environment 265 (2021): 112636. [CrossRef]

- Cvetković, Vladimir., and J. Martinović. "Inovative Solutions for Flood Risk Management." International Journal of Disaster Risk Management 2, no. 2 (2020).

- Nikolić, Neda, Vladimir Cvetković, and Aleksandar Ivanov. "Human Resource Development for Environmental Security and Emergency Management." Scientific-Professional Society for Disaster Risk Management, Belgrade, 2023.

- Cvetković, Vladimir, Milica Čvorović, and Hatidža Beriša. "The Gender Dimension of Vulnerability in Disaster Caused by the Corona Virus (COVID-19)." NBP 28, no. 2 (2023): 32-54.

- Cvetković, V. M., S. Romanić, and H. Beriša. "Religion Influence on Disaster Risk Reduction: A Case Study of Serbia." International Journal of Disaster Risk Management 5, no. 1 (2023): 66-81. [CrossRef]

- Cvetković, Vladimir. "A Predictive Model of Community Disaster Resilience Based on Social Identity Influences (Modersi)." International Journal of Disaster Risk Management 5, no. 2 (2023): 57-80. [CrossRef]

- Cvetković, Vladimir, Boban Milojković, and Dragan Stojković. "Analysis of Geospatial and Temporal Distribution of Earthquakes as Natural Disasters." Vojno delo 66, no. 2 (2014): 166-85. [CrossRef]

- Cvetković, Vladimir M., Jasmina Gačić, and Vladimir Jakovljević. "Geospatial and Temporal Distribution of Forest Fires as Natural Disasters." Vojno delo 68, no. 2 (2016): 108-27. [CrossRef]

- Ivanov, Aleksandar, and Vladimir Cvetković. "Prirodne Katastofe - Geoprostorna i vremenska distribucija (Natural Disasters - Geospatial and Temporal Distribution)." Fakultet za bezbednost, Skopje, 2016.

- Cvetković, V., and D. Stojković. "Analysis of Geospatial and Temporal Distribution of Storms as a Natural Disaster." In International Scientific Conference - Criminalistic Education, Situation and Perspectives 20 Years after Vodinelic. Skopje: Faculty of Security, University St. Kliment Ohridski - Bitola in collaboration with Faculty of detectives and Security, FON University, 2015.

- Cvetković, Vladimir. "Geoprostorna i Vremenska Distribucija Vulkanskih Erupcija." NBP–Žurnal za kriminalistiku i pravo 2, no. 2014 (2014): 150-65.

- Cvetković, Vladimir M., and Vanja Šišović. "Community Disaster Resilience in Serbia." Scientific-Professional Society for Disaster Risk Management, Belgrade, 2024.

- Cvetković, V., & Filipović, M. (2017). Risk management of natural disasters: Concepts and Methods. International Scientific Conference “New directions and challenges in transforming societies through a multidisciplinary approach” 6th June, 2017, MIT University, City Gallery, Skopje, Republic of Macedonia.

- Cvetković, Vladimir "Innovative Solutions for Disaster Early Warning and Alert Systems: A Literary Review." Paper presented at the XI International scientific conference Archibald Reiss days, November 9-10, 2021At: Belgrade, University of Criminal Investigation and Police Studies 2021.

- Cools, Jan, Demetrio Innocenti, and Sarah O’Brien. "Lessons from Flood Early Warning Systems." Environmental science & policy 58 (2016): 117-22.

- Cvetković, Vladimir. "Innovative Solutions for Disaster Early Warning and Alert Systems: A Literary Review." 2021.

- Cvetković, Vladimir, and Marko Nikolić. "The Role of Social Networks in Disaster Risk Reduction: A Case Study Belgrade (Uloga Društvenih Mreža U Smanjenju Rizika Od Katastrofa: Studija Slučaja Beograd)." Bezbednost 61, no. 3 (2021): 25-42.

- Cvetković, Vladimir M., Marina Filipović, Slavoljub Dragićević, and Ivan Novković. "The Role of Social Networks in Disaster Risk Reduction." Eight International Scientific Conference “Archibald Reiss Days” , Belgrade, October 2–3, 2018.

- Cvetković, Vladimir, and Aleksandra Nikolić. "The Role of Social Media in the Process of Informing the Public About Disaster Risks." Preprint (2023): 10-20944. [CrossRef]

- Myint, S. W., M. Yuan, R. S. Cerveny, and C. Giri. "Categorizing Natural Disaster Damage Assessment Using Satellite-Based Geospatial Techniques." Natural Hazards and Earth System Sciences 8, no. 4 (2008): 707-19. [CrossRef]

- Cvetković, Vladimir, Jasmina Tanasić, Adem Ocal, Mirjana Živković-Šulović, Nedeljko Ćurić, Stefan Milojević, and Snežana Knežević. "The Assessment of Public Health Capacities at Local Self-Governments in Serbia." Lex localis - Journal of Local Self Government 21, no. 4 (2023): 1201-34. [CrossRef]

- Cvetković, Vladimir M. "A Predictive Model of Community Disaster Resilience Based on Social Identity Influences (Modersi)." International Journal of Disaster Risk Management 5, no. 2 (2023): 57-80. [CrossRef]

- Cvetković, Vladimir, and Jelena Planić. "Earthquake Risk Perception in Belgrade: Implications for Disaster Risk Management." International Journal of Disaster Risk Management 4, no. 1 (2022): 69-89. [CrossRef]

- Kragh Andersen, Per, Maja Pohar Perme, Hans C. van Houwelingen, Richard J. Cook, Pierre Joly, Torben Martinussen, Jeremy M. G. Taylor, Michal Abrahamowicz, and Terry M. Therneau. "Analysis of Time-to-Event for Observational Studies: Guidance to the Use of Intensity Models." Statistics in medicine 40, no. 1 (2021): 185-211.

- Melkov, Dmitry, Vladislav Zaalishvili, Olga Burdzieva, and Aleksandr Kanukov. "Temporal and Spatial Geophysical Data Analysis in the Issues of Natural Hazards and Risk Assessment (in Example of North Ossetia, Russia)." Applied Sciences 12, no. 6 (2022): 2790. [CrossRef]

- Chen, Ning, Zhige Zhang, Yingchao Ma, An Chen, and Xiaohui Yao. "Assessment and Clustering of Temporal Disaster Risk: Two Case Studies of China." Intelligent Decision Technologies 16, no. 1 (2022): 247-61. [CrossRef]

- Coronese, Matteo, Francesco Lamperti, Klaus Keller, Francesca Chiaromonte, and Andrea Roventini. "Evidence for Sharp Increase in the Economic Damages of Extreme Natural Disasters." Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 116, no. 43 (2019): 21450-55. [CrossRef]

- Cvetković, Vladimir, and Slavoljub Dragicević. "Spatial and Temporal Distribution of Natural Disasters." Journal of the Geographical Institute Jovan Cvijic, SASA 64, no. 3 (2014): 293-309. [CrossRef]

- Chen, Baoxin, Kan Chen, Xi Wang, and Xu Wang. "Spatial and Temporal Distribution Characteristics of Rainstorm and Flood Disasters around Tarim Basin." Polish journal of environmental studies 31, no. 3 (2022). [CrossRef]

- Herrera, Daissy, and Edier Aristizábal. "Spatial and Temporal Distribution of Precipitation and Its Relationship with Landslides within the Aburrá Valley, Northern Colombian Andes." Copernicus Meetings, 2024.

- Peng, Yu, Shaofen Long, Jiangwen Ma, Jingyi Song, and Zhengwei Liu. "Temporal-Spatial Variability in Correlations of Drought and Flood During Recent 500 Years in Inner Mongolia, China." Science of the Total Environment 633 (2018): 484-91. [CrossRef]

- Martínez–Álvarez, Francisco, and A. Morales–Esteban. "Big Data and Natural Disasters: New Approaches for Spatial and Temporal Massive Data Analysis." 38-39: Elsevier, 2019. [CrossRef]

- Ge, Xingtong, Yi Yang, Jiahui Chen, Weichao Li, Zhisheng Huang, Wenyue Zhang, and Ling Peng. "Disaster Prediction Knowledge Graph Based on Multi-Source Spatio-Temporal Information." Remote Sensing 14, no. 5 (2022): 1214. [CrossRef]

- Kumar, Amit, Dominik H. Lang, Hasibullah Ziar, and Yogendra Singh. "Seismic Vulnerability Assessment of Non-Structural Components-Methodology, Implementation Approach and Impact Assessment in South and Central Asia." Journal of Earthquake Engineering 26, no. 3 (2022): 1300-24.

- Nawaz, Ahsan, Xing Su, Qaiser Mohi Ud Din, Muhammad Irslan Khalid, Muhammad Bilal, and Syyed Adnan Raheel Shah. "Identification of the H&S (Health and Safety Factors) Involved in Infrastructure Projects in Developing Countries-a Sequential Mixed Method Approach of Olmt-Project." International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 17, no. 2 (2020): 635. [CrossRef]

- Eriksson, Per Erik, Stefan Olander, Henrik Szentes, and Kristian Widén. "Managing Short-Term Efficiency and Long-Term Development through Industrialized Construction." Construction management and Economics 32, no. 1-2 (2014): 97-108. [CrossRef]

- Busby, Joshua W., Todd G. Smith, and Nisha Krishnan. "Climate Security Vulnerability in Africa Mapping 3.0." Political Geography 43 (2014): 51-67. [CrossRef]

- Forzieri, Giovanni, Luc Feyen, Simone Russo, Michalis Vousdoukas, Lorenzo Alfieri, Stephen Outten, Mirco Migliavacca, Alessandra Bianchi, Rodrigo Rojas, and Alba Cid. "Multi-Hazard Assessment in Europe under Climate Change." Climatic Change 137 (2016): 105-19. [CrossRef]

- Garcia, Carolina, and Carina J. Fearnley. "Evaluating Critical Links in Early Warning Systems for Natural Hazards." Environmental Hazards 11, no. 2 (2012): 123-37. [CrossRef]

- Satyanarayana, Behara, Tom Van der Stocken, Guillaume Rans, Kodikara Arachchilage Sunanda Kodikara, Gaétane Ronsmans, Loku Pulukkuttige Jayatissa, Mohd-Lokman Husain, Nico Koedam, and Farid Dahdouh-Guebas. "Island-Wide Coastal Vulnerability Assessment of Sri Lanka Reveals That Sand Dunes, Planted Trees and Natural Vegetation May Play a Role as Potential Barriers against Ocean Surges." Global Ecology and Conservation 12 (2017): 144-57. [CrossRef]

- Pidgeon, Nick, and Mike O'Leary. "Man-Made Disasters: Why Technology and Organizations (Sometimes) Fail." Safety Science 34, no. 1-3 (2000): 15-30. [CrossRef]

- Wilby, Robert L., and Rod Keenan. "Adapting to Flood Risk under Climate Change." Progress in physical geography 36, no. 3 (2012): 348-78. [CrossRef]

- Tseng, Chun-Pin, and Cheng-Wu Chen. "Natural Disaster Management Mechanisms for Probabilistic Earthquake Loss." Natural Hazards 60 (2012): 1055-63. [CrossRef]

- Glago, Frank Jerome. "Flood Disaster Hazards; Causes, Impacts and Management: A State-of-the-Art Review." Natural hazards-impacts, adjustments and resilience (2021): 29-37.

- Munawar, Hafiz Suliman, Ahmed W. A. Hammad, and S. Travis Waller. "Remote Sensing Methods for Flood Prediction: A Review." Sensors 22, no. 3 (2022): 960. [CrossRef]

- Raikes, Jonathan, Timothy F. Smith, Claudia Baldwin, and Daniel Henstra. "Disaster Risk Reduction and Climate Policy Implementation Challenges in Canada and Australia." Climate Policy 22, no. 4 (2022): 534-48. [CrossRef]

- Pucher, John, Zhong-ren Peng, Neha Mittal, Yi Zhu, and Nisha Korattyswaroopam. "Urban Transport Trends and Policies in China and India: Impacts of Rapid Economic Growth." Transport reviews 27, no. 4 (2007): 379-410. [CrossRef]

- Carby, Barbara. "Integrating Disaster Risk Reduction in National Development Planning: Experience and Challenges of Jamaica." Environmental Hazards 17, no. 3 (2018): 219-33. [CrossRef]

- Stanganelli, Marialuce. "A New Pattern of Risk Management: The Hyogo Framework for Action and Italian Practise." Socio-Economic Planning Sciences 42, no. 2 (2008): 92-111. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Jieh-Jiuh. "Post-Disaster Cross-Nation Mutual Aid in Natural Hazards: Case Analysis from Sociology of Disaster and Disaster Politics Perspectives." Natural Hazards 66 (2013): 413-38. [CrossRef]

- Yumul Jr, Graciano P., Nathaniel A. Cruz, Nathaniel T. Servando, and Carla B. Dimalanta. "Extreme Weather Events and Related Disasters in the Philippines, 2004–08: A Sign of What Climate Change Will Mean?" Disasters 35, no. 2 (2011): 362-82.

- Rauscher, Natalie, and Welf Werner. "Why Has Catastrophe Mitigation Failed in the Us?" ZPB Zeitschrift für Politikberatung 8, no. 4 (2022): 149-73.

- Iuchi, Kanako, Yasuhito Jibiki, Renato Solidum Jr, and Ramon Santiago. "Natural Hazards Governance in the Philippines." In Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Natural Hazard Science, 2019.

- Ebi, Kristie L., and Jordana K. Schmier. "A Stitch in Time: Improving Public Health Early Warning Systems for Extreme Weather Events." Epidemiologic reviews 27, no. 1 (2005): 115-21. [CrossRef]

- Mashi, Sani Abubakar, Obaro Dominic Oghenejabor, and Amina Ibrahim Inkani. "Disaster Risks and Management Policies and Practices in Nigeria: A Critical Appraisal of the National Emergency Management Agency Act." International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction 33 (2019): 253-65. [CrossRef]

- Goncalves Filho, Anastacio Pinto, and Patrick Waterson. "Maturity Models and Safety Culture: A Critical Review." Safety Science 105 (2018): 192–211.

- Prothi, Amit, Mona Chhabra Anand, and Ratnesh Kumar. "Adaptive Pathways for Resilient Infrastructure in an Evolving Disasterscape." 3-4: Taylor & Francis, 2023. [CrossRef]

- Buck, Kyle D., Kevin J. Summers, Stephen Hafner, Lisa M. Smith, and Linda C. Harwell. "Development of a Multi-Hazard Landscape for Exposure and Risk Interpretation: The Prism Approach." Current environmental engineering 6, no. 1 (2019): 74-94. [CrossRef]

- Prior, Tim, Michel Herzog, Tabea Kaderli, and Florian Roth. "International Civil Protection: Adapting to New Challenges." ETH Zurich, 2016.

- Cutter, Susan L., and Christina Finch. "Temporal and Spatial Changes in Social Vulnerability to Natural Hazards." Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 105, no. 7 (2008): 2301-06.

- Krausmann, Elisabeth, Valerio Cozzani, Ernesto Salzano, and Elisabetta Renni. "Industrial Accidents Triggered by Natural Hazards: An Emerging Risk Issue." Natural Hazards and Earth System Sciences 11, no. 3 (2011): 921-29. [CrossRef]

- Evan, William M., and Mark Manion. Minding the Machines: Preventing Technological Disasters: Prentice Hall Professional, 2002.

- Brauch, Hans Günter. "Urbanization and Natural Disasters in the Mediterranean: Population Growth and Climate Change in the 21st Century." Building safer cities 149 (2003).

- Forzieri, Giovanni, Alessandra Bianchi, Filipe Batista e Silva, Mario A. Marin Herrera, Antoine Leblois, Carlo Lavalle, Jeroen C. J. H. Aerts, and Luc Feyen. "Escalating Impacts of Climate Extremes on Critical Infrastructures in Europe." Global environmental change 48 (2018): 97-107. [CrossRef]

- Harrison, Sara, Sally Potter, Raj Prasanna, Emma H Doyle, and David Johnston. "Identifying the Impact-Related Data Uses and Gaps for Hydrometeorological Impact Forecasts and Warnings." Weather, Climate, and Society 14 (2022): 155–76. [CrossRef]

- Bean, Hamilton, Jeannette Sutton, Brooke F. Liu, Stephanie Madden, Michele M. Wood, and Dennis S. Mileti. "The Study of Mobile Public Warning Messages: A Research Review and Agenda." Review of Communication 15, no. 1 (2015): 60-80. [CrossRef]

- Dengler, Lori, James Goltz, Johanna Fenton, Kevin Miller, and Rick Wilson. "Building Tsunami-Resilient Communities in the United States: An Example from California." TsuInfo Alert 13, no. 2 (2011): 1-14.

- Shahriar, Hossain, and Mohammad Zulkernine. "Mitigating Program Security Vulnerabilities: Approaches and Challenges." ACM Computing Surveys (CSUR) 44, no. 3 (2012): 1-46.

- Waugh, John D. Neighborhood Watch: Early Detection and Rapid Response to Biological Invasion Along Us Trade Pathways: IUCN, 2009.

- Brauch, Hans Günter. "Concepts of Security Threats, Challenges, Vulnerabilities and Risks." In Coping with Global Environmental Change, Disasters and Security: Threats, Challenges, Vulnerabilities and Risks, 61-106: Springer, 2011.

- Coleman, Les. "Frequency of Man-Made Disasters in the 20th Century." Journal of contingencies and crisis management 14, no. 1 (2006): 3-11.

- Granot, Hayim. "The Dark Side of Growth and Industrial Disasters since the Second World War." Disaster Prevention and Management: An International Journal 7, no. 3 (1998): 195-204. [CrossRef]

- Zinn, Jens O. "Towards a Better Understanding of Risk-Taking: Key Concepts, Dimensions and Perspectives." 99-114: Taylor & Francis, 2015.

- Bouwer, Laurens M. "Have Disaster Losses Increased Due to Anthropogenic Climate Change?" Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society 92, no. 1 (2011): 39-46.

- Lei, Yongdeng, and Jing’ai Wang. "A Preliminary Discussion on the Opportunities and Challenges of Linking Climate Change Adaptation with Disaster Risk Reduction." Natural Hazards 71 (2014): 1587-97.

- Mata-Lima, Herlander, Andreilcy Alvino-Borba, Adilson Pinheiro, Abel Mata-Lima, and José António Almeida. "Impacts of Natural Disasters on Environmental and Socio-Economic Systems: What Makes the Difference?" Ambiente & Sociedade 16 (2013): 45-64. [CrossRef]

- Peters, Katie, Laura E. R. Peters, John Twigg, and Colin Walch. "Disaster Risk Reduction Strategies." London: Overseas Development Institute (2019).

- Klein, Julia A., Catherine M. Tucker, Cara E. Steger, Anne Nolin, Robin Reid, Kelly A. Hopping, Emily T. Yeh, Meeta S. Pradhan, Andrew Taber, and David Molden. "An Integrated Community and Ecosystem-Based Approach to Disaster Risk Reduction in Mountain Systems." Environmental science & policy 94 (2019): 143-52.

- Albright, Elizabeth A., and Deserai A. Crow. "Capacity Building toward Resilience: How Communities Recover, Learn, and Change in the Aftermath of Extreme Events." Policy Studies Journal 49, no. 1 (2021): 89-122. [CrossRef]

- Walia, Ajinder. "Community Based Disaster Preparedness: Need for a Standardized Training Module." Australian Journal of Emergency Management, The 23, no. 2 (2008): 68-73.

- Haddow, George, and Kim S. Haddow. Disaster Communications in a Changing Media World: Butterworth-Heinemann, 2013.

- Curtis, Carey, and Jan Scheurer. "Planning for Sustainable Accessibility: Developing Tools to Aid Discussion and Decision-Making." Progress in planning 74, no. 2 (2010): 53-106. [CrossRef]

- Alexander, David. "The Study of Natural Disasters, 1977–97: Some Reflections on a Changing Field of Knowledge." Disasters 21, no. 4 (1997): 284-304.

- Scott, Allen J. A World in Emergence: Cities and Regions in the 21st Century: Edward Elgar Publishing, 2012.

- Brunn, Stanley D., Jack Francis Williams, and Donald J. Zeigler. Cities of the World: World Regional Urban Development: Rowman & Littlefield, 2003.

- Haddad, Edson, Pablo F. Aguilar Alcalá, and Jorge Luiz Nobre Gouveia. "Environmental and Technological Disasters and Emergencies." Luiz Augusto C. Galvão Jacobo Finkelman: 629.

- Duarte Santos, Filipe, and Filipe Duarte Santos. "Anthropocene, Technosphere, Biosphere, and the Contemporary Utopias." Time, Progress, Growth and Technology: How Humans and the Earth are Responding (2021): 381-542.

- Ahmad, Najid, Liu Youjin, Saša Žiković, and Zhanna Belyaeva. "The Effects of Technological Innovation on Sustainable Development and Environmental Degradation: Evidence from China." Technology in Society 72 (2023): 102184. [CrossRef]

- Trautman, Lawrence J., and Peter C. Ormerod. "Industrial Cyber Vulnerabilities: Lessons from Stuxnet and the Internet of Things." U. Miami L. Rev. 72 (2017): 761.

- Keim, Mark E. "The Role of Public Health in Disaster Risk Reduction as a Means for Climate Change Adaptation." Global climate change and human health: From science to practice 35 (2015).

- Quansah, Joseph E., Bernard Engel, and Gilbert L. Rochon. "Early Warning Systems: A Review." Journal of Terrestrial Observation 2, no. 2 (2010): 5.

- Mal, Suraj, R. B. Singh, Christian Huggel, and Aakriti Grover. "Introducing Linkages between Climate Change, Extreme Events, and Disaster Risk Reduction." Climate change, extreme events and disaster risk reduction: Towards sustainable development goals (2018): 1-14.

- Wagner, Philip, and Michael R. Reich. "Technological Hazards." Regions of Risk: A Geographical Introduction to Disasters (2014): 91.

- de Souza Porto, Marcelo Firpo, and Carlos Machado de Freitas. "Major Chemical Accidents in Industrializing Countries: The Socio-Political Amplification of Risk." Risk analysis 16, no. 1 (1996): 19-29.

- Clarke, Ben, Friederike Otto, Rupert Stuart-Smith, and Luke Harrington. "Extreme Weather Impacts of Climate Change: An Attribution Perspective." Environmental Research: Climate 1, no. 1 (2022): 012001. [CrossRef]

- Duffey, Romney, and John Saull. Know the Risk: Learning from Errors and Accidents: Safety and Risk in Today's Technology: Elsevier, 2002.

- Brooks, Nick, and Neil W. Adger. "Country Level Risk Measures of Climate-Related Natural Disasters and Implications for Adaptation to Climate Change." (2003).

- Schipper, Lisa, and Mark Pelling. "Disaster Risk, Climate Change and International Development: Scope for, and Challenges to, Integration." Disasters 30, no. 1 (2006): 19-38. [CrossRef]

- Berg, Monika, and Veronica De Majo. "Understanding the Global Strategy for Disaster Risk Reduction." Risk, Hazards & Crisis in Public Policy 8, no. 2 (2017): 147-67. [CrossRef]

- Bankoff, Greg, Georg Frerks, and Dorothea Hilhorst. Mapping Vulnerability: Disasters, Development and People: Routledge, 2013.

- Hannigan, John. Disasters without Borders: The International Politics of Natural Disasters: John Wiley & Sons, 2013.

| 1. | The category includes a wide range of water-related disasters, not just floods. It also covers incidents like glacial lake outburst floods and coastal erosion. The common thread is that water plays a crucial role in causing these events. |

| Continent | Total disasters | Natural disasters | Man-made (tech.) disasters |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | n | % | |

| North America | 3,575 | 13.84 | 2,708 | 75.75 | 867 | 24.25 |

| Asia | 10,786 | 41.75 | 6,675 | 61.89 | 4,111 | 38.11 |

| Africa | 5,540 | 21.44 | 3,114 | 56.21 | 2,426 | 43.79 |

| Europe | 3,091 | 11.96 | 1,995 | 64.54 | 1,096 | 35.46 |

| South America | 2,114 | 8.18 | 1,407 | 66.56 | 707 | 33.44 |

| Oceania | 730 | 2.83 | 668 | 91.51 | 62 | 8.49 |

| Total | 25,836 | 100 | 16,567 | 69.41 | 9,269 | 30.59 |

| Disaster type | North America |

Asia | Africa | Europe | South America | Oceania | Total | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (n) | (%) | (n) | (%) | (n) | (%) | (n) | (%) | (n) | (%) | (n) | (%) | (n) | (%) | |

| Earthquake | 167 | 0.65 | 951 | 3.68 | 75 | 0.29 | 163 | 0.63 | 154 | 0.60 | 57 | 0.22 | 1567 | 6.07 |

| Volcanic activity | 45 | 0.17 | 112 | 0.43 | 19 | 0.07 | 11 | 0.04 | 45 | 0.17 | 32 | 0.12 | 264 | 1.00 |

| Flood | 688 | 2.66 | 2429 | 9.40 | 1240 | 4.80 | 650 | 2.52 | 685 | 2.65 | 160 | 0.62 | 5852 | 22.65 |

| Water-related | 99 | 0.38 | 703 | 2.72 | 561 | 2.17 | 163 | 0.63 | 63 | 0.24 | 14 | 0.05 | 1603 | 6.19 |

| Mass movement (wet) | 45 | 0.17 | 440 | 1.70 | 68 | 0.26 | 77 | 0.30 | 155 | 0.60 | 18 | 0.07 | 803 | 3.10 |

| Drought | 102 | 0.39 | 179 | 0.69 | 361 | 1.40 | 49 | 0.19 | 74 | 0.29 | 34 | 0.13 | 799 | 3.09 |

| Extreme temperature | 70 | 0.27 | 200 | 0.77 | 20 | 0.08 | 297 | 1.15 | 48 | 0.19 | 8 | 0.03 | 643 | 2.49 |

| Glacial lake outburst flood | 0 | 0.00 | 3 | 0.01 | 0 | 0.00 | 1 | 0.00 | 0 | 0.00 | 0 | 0.00 | 4 | 0.01 |

| Storm | 1338 | 5.18 | 1899 | 7.35 | 311 | 1.20 | 576 | 2.23 | 105 | 0.41 | 290 | 1.12 | 4519 | 17.49 |

| Epidemic | 100 | 0.39 | 361 | 1.40 | 899 | 3.48 | 44 | 0.17 | 84 | 0.33 | 24 | 0.09 | 1512 | 5.86 |

| Wildfire | 145 | 0.56 | 69 | 0.27 | 38 | 0.15 | 123 | 0.48 | 49 | 0.19 | 41 | 0.16 | 465 | 1.81 |

| Air | 187 | 0.72 | 312 | 1.21 | 169 | 0.65 | 233 | 0.90 | 124 | 0.48 | 21 | 0.08 | 1046 | 4.04 |

| Animal incident | 0 | 0.00 | 0 | 0.00 | 0 | 0.00 | 0 | 0.00 | 0 | 0.00 | 0 | 0.00 | 0 | 0.00 |

| Chemical spill | 47 | 0.18 | 20 | 0.08 | 4 | 0.02 | 29 | 0.11 | 3 | 0.01 | 1 | 0.00 | 104 | 0.40 |

| Collapse (Industrial) | 3 | 0.01 | 88 | 0.34 | 70 | 0.27 | 7 | 0.03 | 15 | 0.06 | 0 | 0.00 | 183 | 0.71 |

| Collapse (Miscellaneous) | 29 | 0.11 | 156 | 0.60 | 61 | 0.24 | 30 | 0.12 | 25 | 0.10 | 2 | 0.01 | 303 | 1.18 |

| Explosion (Industrial) | 57 | 0.22 | 509 | 1.97 | 59 | 0.23 | 108 | 0.42 | 32 | 0.12 | 4 | 0.02 | 769 | 2.98 |

| Explosion (Miscellaneous) | 17 | 0.07 | 118 | 0.46 | 40 | 0.15 | 35 | 0.14 | 10 | 0.04 | 0 | 0.00 | 220 | 0.86 |

| Fire (Industrial) | 22 | 0.09 | 137 | 0.53 | 15 | 0.06 | 35 | 0.14 | 7 | 0.03 | 0 | 0.00 | 216 | 0.85 |

| Fire (Miscellaneous) | 111 | 0.43 | 395 | 1.53 | 117 | 0.45 | 117 | 0.45 | 42 | 0.16 | 7 | 0.03 | 789 | 3.05 |

| Fog | 0 | 0.00 | 0 | 0.00 | 0 | 0.00 | 0 | 0.00 | 0 | 0.00 | 0 | 0.00 | 0 | 0.00 |

| Gas leak | 13 | 0.05 | 38 | 0.15 | 0 | 0.00 | 10 | 0.04 | 0 | 0.00 | 1 | 0.00 | 62 | 0.24 |

| Industrial accident | 7 | 0.03 | 89 | 0.34 | 16 | 0.06 | 5 | 0.02 | 8 | 0.03 | 1 | 0.00 | 126 | 0.48 |

| Infestation | 0 | 0.00 | 0 | 0.00 | 0 | 0.00 | 0 | 0.00 | 0 | 0.00 | 0 | 0.00 | 0 | 0.00 |

| Mass movement (dry) | 0 | 0.00 | 0 | 0.00 | 0 | 0.00 | 0 | 0.00 | 0 | 0.00 | 0 | 0.00 | 0 | 0.00 |

| Miscellaneous accident | 23 | 0.09 | 129 | 0.50 | 68 | 0.26 | 31 | 0.12 | 19 | 0.07 | 1 | 0.00 | 813 | 2.10 |

| Oil spill | 3 | 0.01 | 2 | 0.01 | 0 | 0.00 | 2 | 0.01 | 1 | 0.00 | 0 | 0.00 | 24 | 0.03 |

| Poisoning | 6 | 0.02 | 50 | 0.19 | 6 | 0.02 | 10 | 0.04 | 4 | 0.02 | 0 | 0.00 | 228 | 0.29 |

| Radiation | 1 | 0.00 | 4 | 0.02 | 0 | 0.00 | 0 | 0.00 | 1 | 0.00 | 0 | 0.00 | 18 | 0.01 |

| Rail | 74 | 0.29 | 288 | 1.11 | 111 | 0.43 | 122 | 0.47 | 15 | 0.06 | 5 | 0.02 | 1845 | 2.38 |

| Road | 168 | 0.65 | 1073 | 4.15 | 1129 | 4.37 | 159 | 0.62 | 338 | 1.31 | 5 | 0.02 | 8616 | 11.21 |

| Country (rang) | Total disasters |

Natural disasters |

Man-made (tech.) disasters |

Top 5 disasters by country | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (n) | (%) | (n) | (%) | (n) | (%) | 1th | 2th | 3th | 4th | 5th | |

| 1. China | 1,996 | 7.54 | 1,012 | 50.70 | 984 | 49.30 | IA (15.08) | S (14.73) | F (14.53) | D (14.28) | E (14.23) |

| 2. India | 1,581 | 5.97 | 776 | 49.08 | 805 | 50.92 | E (15.50) | IA (14.86) | D (14.80) | F (14.29) | E (14.17) |

| 3. USA | 1,513 | 5.72 | 1,152 | 76.14 | 361 | 23.86 | E (15.27) | IA (14.87) | D (14.47) | F (14.41) | W (13.88) |

| 4. Philippines | 938 | 3.54 | 698 | 74.41 | 240 | 25.59 | IA (16.10) | S (14.71) | D (14.50) | E (14.39) | W (14.18) |

| 5. Indonesia | 878 | 3.32 | 621 | 70.73 | 257 | 29.27 | F (16.40) | E (15.15) | D (15.03) | E (14.81) | W (13.44) |

| 6. Bangladesh | 588 | 2.22 | 363 | 61.73 | 225 | 38.27 | F (15.99) | D (15.14) | IA (15.14) | E (14.97) | S (13.27) |

| 7. Nigeria | 523 | 1.98 | 143 | 27.34 | 380 | 72.66 | W (16.63) | S (16.44) | IA (14.72) | E (14.53) | D (13.38) |

| 8. Pakistan | 504 | 1.90 | 254 | 50.40 | 250 | 49.60 | F (15.08) | W (15.08) | S (14.88) | IA (14.29) | E (13.89) |

| 9. Mexico | 481 | 1.82 | 304 | 63.20 | 177 | 36.80 | W (17.88) | E (15.59) | F (15.18) | D (13.51) | E (12.89) |

| 10. Japan | 464 | 1.75 | 389 | 83.84 | 75 | 16.16 | W (17.24) | E (15.73) | S (15.09) | D (14.44) | IA (13.79) |

| 11. Brazil | 462 | 1.75 | 283 | 61.26 | 179 | 38.74 | E (15.15) | IA (15.15) | W (14.94) | D (14.72) | F (14.50) |

| 12. Iran | 442 | 1.67 | 265 | 59.95 | 177 | 40.05 | D (17.87) | E (15.61) | W (15.16) | IA (14.48) | F (13.35) |

| 13. Russia | 417 | 1.58 | 178 | 42.69 | 239 | 57.31 | E (17.27) | W (15.35) | S (15.11) | D (14.63) | IA (13.43) |

| 14. Peru | 397 | 1.50 | 217 | 54.66 | 180 | 45.34 | F (15.87) | E (15.37) | E (14.36) | S (14.11) | IA (13.85) |

| 15. Türkiye | 390 | 1.47 | 217 | 55.64 | 173 | 44.36 | D (16.67) | IA (15.13) | W (15.13) | S (14.36) | F (13.33) |

| 16. Congo | 342 | 1.29 | 155 | 45.32 | 187 | 54.68 | S (17.54) | W (14.91) | D (14.04) | IA (14.04) | E (13.45) |

| 17. Colombia | 339 | 1.28 | 232 | 68.44 | 107 | 31.56 | IA (16.52) | E (16.22) | D (14.45) | E (14.45) | S (14.45) |

| 18. Viet Nam | 338 | 1.28 | 264 | 78.11 | 74 | 21.89 | S (16.86) | E (16.57) | D (15.98) | W (15.38) | F (14.79) |

| 19. South Africa | 326 | 1.23 | 129 | 39.57 | 197 | 60.43 | D (16.56) | S (15.64) | F (14.72) | IA (14.72) | E (14.42) |

| 20. France | 296 | 1.12 | 203 | 68.58 | 93 | 31.42 | W (20.27) | IA (14.53) | E (14.19) | D (13.85) | S (13.51) |

| 21. Italy | 285 | 1.08 | 187 | 65.61 | 98 | 34.39 | F (17.54) | IA (17.54) | S (15.44) | D (13.68) | E (13.33) |

| 22. Afghanistan | 274 | 1.04 | 219 | 79.93 | 55 | 20.07 | E (17.88) | F (16.06) | S (14.60) | D (14.23) | W (13.14) |

| 23. Thailand | 274 | 1.04 | 172 | 62.77 | 102 | 37.23 | E (20.07) | W (17.88) | E (13.50) | S (13.14) | D (12.77) |

| 24. Australia | 257 | 0.97 | 223 | 86.77 | 34 | 13.23 | E (17.51) | D (15.18) | F (14.01) | S (14.01) | E (13.23) |

| 25. Egypt | 252 | 0.95 | 36 | 14.29 | 216 | 85.71 | E (20.24) | E (15.08) | IA (13.89) | W (13.49) | S (12.70) |

| 26. Canada | 246 | 0.93 | 153 | 62.20 | 93 | 37.80 | F (17.89) | D (15.04) | S (14.23) | E (13.82) | IA (13.82) |

| 27. Kenya | 231 | 0.87 | 126 | 54.55 | 105 | 45.45 | IA (17.75) | F (16.88) | E (16.02) | S (13.85) | D (13.42) |

| 28. Nepal | 215 | 0.81 | 139 | 64.65 | 76 | 35.35 | E (18.14) | S (16.74) | D (14.88) | E (14.88) | IA (12.56) |

| 29. Tanzania | 214 | 0.81 | 122 | 57.01 | 92 | 42.99 | W (20.56) | IA (16.36) | E (14.49) | F (14.49) | E (13.08) |

| 30. Great Britain | 204 | 0.77 | 105 | 51.47 | 99 | 48.53 | E (19.12) | E (15.69) | F (15.69) | D (14.22) | W (13.24) |

| 31. Rep. Korea | 202 | 0.76 | 132 | 65.35 | 70 | 34.65 | E (17.82) | F (17.82) | W (14.85) | E (13.86) | IA (13.37) |

| 32. Haiti | 196 | 0.74 | 138 | 70.41 | 58 | 29.59 | W (18.37) | IA (17.35) | E (14.80) | F (13.78) | E (13.27) |

| 33. Sudan | 196 | 0.74 | 108 | 55.10 | 88 | 44.90 | IA (18.88) | S (18.37) | F (15.82) | D (14.29) | E (12.76) |

| 34. Uganda | 191 | 0.72 | 111 | 58.12 | 80 | 41.88 | S (17.80) | F (16.23) | E (15.18) | IA (13.61) | D (12.57) |

| 35. Spain | 188 | 0.71 | 112 | 59.57 | 76 | 40.43 | F (17.55) | E (14.89) | E (14.36) | S (14.36) | W (13.83) |

| 36.Taiwan | 187 | 0.71 | 136 | 72.73 | 51 | 27.27 | IA (18.18) | W (14.97) | F (14.44) | D (13.90) | E (13.37) |

| 37. Argentina | 180 | 0.68 | 131 | 72.78 | 49 | 27.22 | W (19.44) | E (18.33) | D (14.44) | F (13.33) | IA (13.33) |

| 38. Ecuador | 166 | 0.63 | 119 | 71.69 | 47 | 28.31 | E (15.06) | E (15.06) | F (15.06) | W (15.06) | IA (13.86) |

| 39. Guatemala | 165 | 0.62 | 127 | 76.97 | 38 | 23.03 | W (16.97) | D (15.76) | S (15.76) | E (13.94) | E (13.33) |

| 40. Ethiopia | 163 | 0.62 | 127 | 77.91 | 36 | 22.09 | D (20.25) | E (17.18) | E (14.72) | F (14.72) | S (14.11) |

| 41. Greece | 163 | 0.62 | 111 | 68.10 | 52 | 31.90 | S (19.02) | E (16.56) | W (15.95) | E (14.11) | IA (12.27) |

| 42. Myanmar | 159 | 0.60 | 89 | 55.97 | 70 | 44.03 | E (18.24) | D (17.61) | F (15.09) | IA (14.47) | S (13.21) |

| 43. Bolivia | 157 | 0.59 | 112 | 71.34 | 45 | 28.66 | F (15.92) | IA (14.65) | W (14.65) | D (14.01) | E (14.01) |

| 44. Sri Lanka | 157 | 0.59 | 131 | 83.44 | 26 | 16.56 | E (21.02) | W (15.92) | S (14.65) | D (14.01) | E (13.38) |

| 45. Algeria | 156 | 0.59 | 93 | 59.62 | 63 | 40.38 | E (16.03) | W (16.03) | S (15.38) | D (14.74) | F (14.74) |

| 46. Belgium | 156 | 0.59 | 72 | 46.15 | 84 | 53.85 | E (17.31) | IA (17.31) | E (14.74) | D (14.10) | F (14.10) |

| 47. Morocco | 156 | 0.59 | 63 | 40.38 | 93 | 59.62 | W (17.31) | E (16.67) | IA (16.03) | S (16.03) | D (11.54) |

| 48. Mozambique | 156 | 0.59 | 125 | 80.13 | 31 | 19.87 | D (19.23) | E (15.38) | F (15.38) | W (14.74) | S (13.46) |

| 49. Chile | 152 | 0.57 | 125 | 82.24 | 27 | 17.76 | F (18.42) | E (15.79) | D (14.47) | E (14.47) | W (13.16) |

| 50. Malaysia | 152 | 0.57 | 109 | 71.71 | 43 | 28.29 | IA (21.05) | S (19.74) | F (15.79) | D (13.82) | W (13.82) |

| Decade | Natural disasters |

Man-made (technological) disasters |

Total | Trend | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (n) | (%) | (n) | (%) | (n) | (%) | Rate (%) | |

| 1900-1910 | 79 | 78.22 | 22 | 21.78 | 101 | 0.38 | Stable (0.00%) |

| 1911-1920 | 78 | 64.46 | 43 | 35.54 | 121 | 0.46 | Increasing (19.57%) |

| 1921-1930 | 106 | 80.30 | 26 | 19.70 | 132 | 0.50 | Increasing (7.40%) |

| 1931-1940 | 133 | 61.29 | 84 | 38.71 | 217 | 0.82 | Increasing (42.20%) |

| 1941-1950 | 171 | 60.85 | 110 | 39.15 | 281 | 1.06 | Increasing (11.73%) |

| 1951-1960 | 310 | 82.01 | 68 | 17.99 | 378 | 1.43 | Increasing (10.05%) |

| 1961-1970 | 594 | 86.09 | 96 | 13.91 | 690 | 2.61 | Increasing (13.59%) |

| 1971-1980 | 871 | 76.14 | 273 | 23.86 | 1144 | 4.32 | Increasing (6.10%) |

| 1981-1990 | 1755 | 64.57 | 963 | 35.43 | 2718 | 10.27 | Increasing (5.33%) |

| 1991-2000 | 2957 | 59.20 | 2038 | 40.80 | 4995 | 18.87 | Increasing (1.71%) |

| 2001-2010 | 4464 | 58.35 | 3187 | 41.65 | 7651 | 28.91 | Increasing (0.70%) |

| 2011-2020 | 3758 | 65.78 | 1955 | 34.22 | 5713 | 21.59 | Decreasing (−0.44%) |

| 2021-2024 | 1747 | 75.20 | 576 | 24.80 | 2323 | 8.78 | Decreasing (−2.49%) |

| Period (5-year intervals) |

Natural disasters |

Man-made (technological) disasters |

Total | Trend | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (n) | (%) | (n) | (%) | (n) | (%) | (%) | |

| 1900-1905 | 35 | 81.40 | 8 | 18.60 | 43 | 0.16 | Stable (0.00%) |

| 1906-1910 | 44 | 75.86 | 14 | 24.14 | 58 | 0.22 | Increasing (34.88%) |

| 1911-1915 | 47 | 77.05 | 14 | 22.95 | 61 | 0.23 | Increasing (5.17%) |

| 1916-1920 | 31 | 51.67 | 29 | 48.33 | 60 | 0.23 | Decreasing (−1.64%) |

| 1921-1925 | 47 | 77.05 | 14 | 22.95 | 61 | 0.23 | Increasing (1.67%) |

| 1926-1930 | 59 | 83.10 | 12 | 16.90 | 71 | 0.27 | Increasing (16.39%) |

| 1931-1935 | 68 | 77.27 | 20 | 22.73 | 88 | 0.33 | Increasing (23.94%) |

| 1936-1940 | 65 | 50.39 | 64 | 49.61 | 129 | 0.49 | Increasing (46.59%) |

| 1941-1945 | 77 | 48.12 | 83 | 51.88 | 160 | 0.60 | Increasing (24.03%) |

| 1946-1950 | 94 | 77.69 | 27 | 22.31 | 121 | 0.46 | Decreasing (−24.38%) |

| 1951-1955 | 157 | 81.77 | 35 | 18.23 | 192 | 0.73 | Increasing (58.68%) |

| 1956-1960 | 153 | 82.26 | 33 | 17.74 | 186 | 0.70 | Decreasing (−3.12%) |

| 1961-1965 | 204 | 85.71 | 34 | 14.29 | 238 | 0.90 | Increasing (27.96%) |

| 1966-1970 | 390 | 86.28 | 62 | 13.72 | 452 | 1.71 | Increasing (89.92%) |

| 1971-1975 | 336 | 77.24 | 99 | 22.76 | 435 | 1.64 | Decreasing (−3.76%) |

| 1976-1980 | 535 | 75.46 | 174 | 24.54 | 709 | 2.68 | Increasing (62.99%) |

| 1981-1985 | 774 | 76.71 | 235 | 23.29 | 1009 | 3.81 | Increasing (42.31%) |

| 1986-1990 | 981 | 57.40 | 728 | 42.60 | 1709 | 6.46 | Increasing (69.38%) |

| 1991-1995 | 1314 | 58.53 | 931 | 41.47 | 2245 | 8.48 | Increasing (31.36%) |

| 1996-2000 | 1643 | 59.75 | 1107 | 40.25 | 2750 | 10.39 | Increasing (22.49%) |

| 2001-2005 | 2291 | 56.72 | 1748 | 43.28 | 4039 | 15.26 | Increasing (46.87%) |

| 2006-2010 | 2173 | 60.16 | 1439 | 39.84 | 3612 | 13.65 | Decreasing (−10.57%) |

| 2011-2015 | 1864 | 63.66 | 1064 | 36.34 | 2928 | 11.06 | Decreasing (−18.94%) |

| 2015-2020 | 1894 | 68.01 | 891 | 31.99 | 2785 | 10.52 | Decreasing (−4.88%) |

| 2020-2024 | 1747 | 75.20 | 576 | 24.80 | 2323 | 8.78 | Decreasing (−16.59%) |

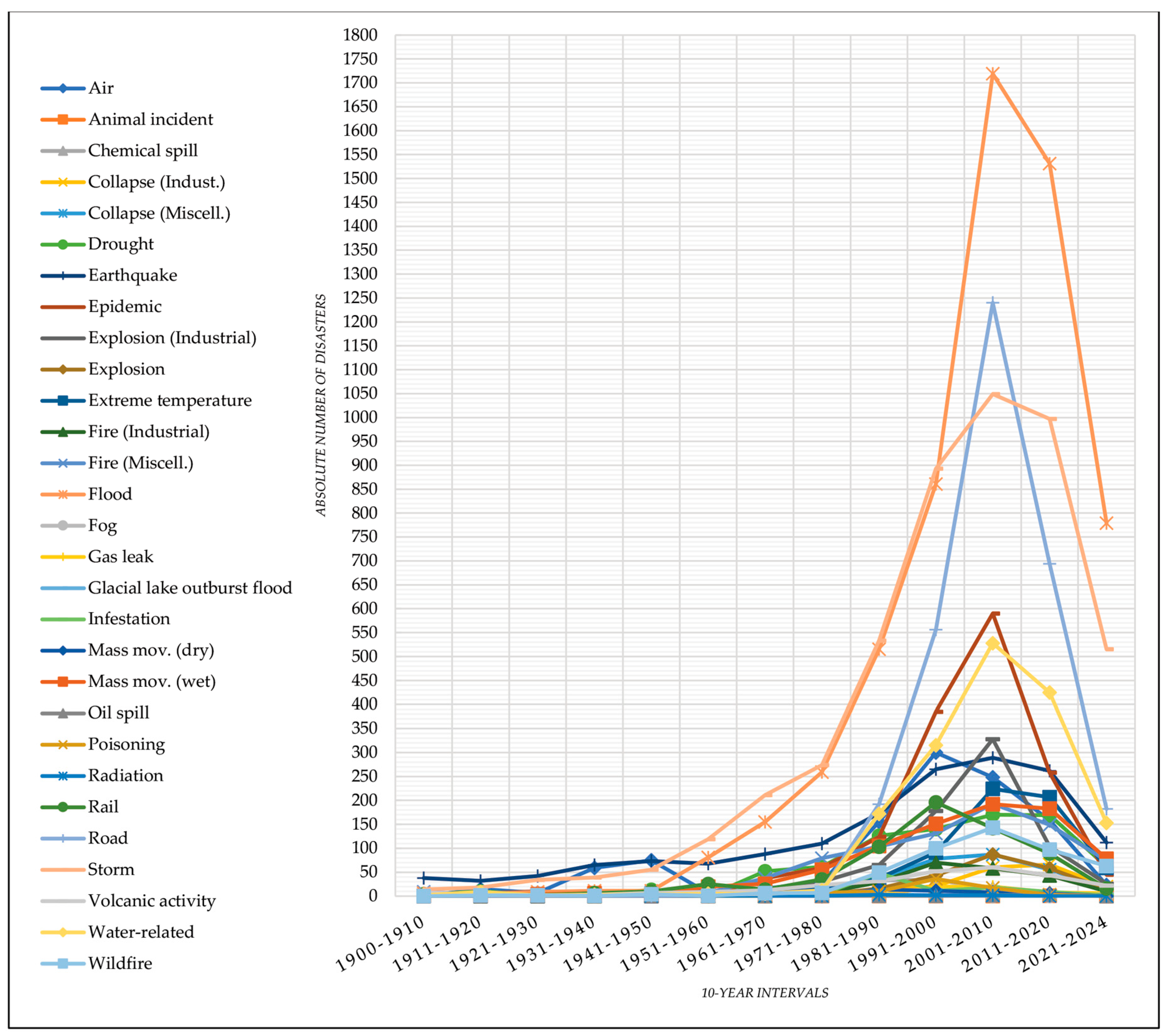

| Disaster type | 1900-1910 | 1911-1920 | 1921-1930 | 1931-1940 | 1941-1950 | 1951-1960 | 1961-1970 | 1971-1980 | 1981-1990 | 1991-2000 | 2001-2010 | 2011-2020 | 2021-2024 | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Air | 0 | 15 | 7 | 59 | 75 | 6 | 16 | 29 | 155 | 300 | 248 | 158 | 23 | 1091 |

| Animal incident | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Chemical spill | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 17 | 33 | 34 | 16 | 7 | 0 | 108 |

| Collapse (Indust.) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 2 | 12 | 21 | 60 | 66 | 20 | 184 |

| Collapse (Miscell.) | 1 | 3 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 7 | 16 | 36 | 78 | 87 | 55 | 16 | 305 |

| Drought | 4 | 10 | 4 | 2 | 13 | 0 | 52 | 61 | 126 | 140 | 170 | 169 | 62 | 813 |

| Earthquake | 38 | 32 | 42 | 65 | 73 | 68 | 88 | 110 | 173 | 265 | 289 | 262 | 112 | 1617 |

| Epidemic | 5 | 6 | 10 | 2 | 3 | 2 | 37 | 59 | 124 | 385 | 590 | 258 | 45 | 1526 |

| Explosion (Industrial) | 5 | 7 | 9 | 10 | 8 | 11 | 6 | 30 | 65 | 178 | 328 | 104 | 26 | 787 |

| Explosion | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 16 | 43 | 87 | 58 | 14 | 222 |

| Extreme temperature | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 8 | 9 | 15 | 37 | 91 | 224 | 207 | 59 | 652 |

| Fire (Industrial) | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 6 | 29 | 70 | 58 | 43 | 10 | 220 |

| Fire (Miscell.) | 9 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 8 | 7 | 38 | 79 | 104 | 131 | 193 | 149 | 74 | 804 |

| Flood | 6 | 4 | 9 | 11 | 11 | 81 | 155 | 259 | 515 | 861 | 1719 | 1531 | 779 | 5941 |

| Fog | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Gas leak | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 5 | 2 | 20 | 20 | 8 | 6 | 62 |

| Glacial lake outburst flood | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 4 |

| Infestation | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 48 | 11 | 18 | 9 | 2 | 95 |

| Mass mov. (dry) | 3 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 14 | 11 | 8 | 5 | 0 | 45 |

| Mass mov. (wet) | 1 | 2 | 4 | 6 | 4 | 20 | 26 | 55 | 105 | 151 | 192 | 183 | 78 | 827 |

| Oil spill | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 0 | 8 |

| Poisoning | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 1 | 7 | 10 | 36 | 17 | 3 | 0 | 76 |

| Radiation | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 9 |

| Rail | 2 | 6 | 2 | 6 | 10 | 25 | 14 | 35 | 103 | 196 | 142 | 89 | 16 | 646 |

| Road | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 4 | 11 | 192 | 556 | 1240 | 694 | 182 | 2882 |

| Storm | 14 | 18 | 34 | 39 | 55 | 119 | 211 | 274 | 533 | 893 | 1049 | 997 | 515 | 4751 |

| Volcanic activity | 8 | 3 | 1 | 3 | 7 | 9 | 12 | 23 | 31 | 52 | 60 | 43 | 22 | 274 |

| Water-related | 2 | 9 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 5 | 12 | 172 | 315 | 528 | 425 | 153 | 1635 |

| Wildfire | 0 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 4 | 1 | 6 | 7 | 49 | 100 | 143 | 97 | 63 | 475 |

| Total | 100 | 121 | 132 | 216 | 278 | 378 | 691 | 1121 | 2688 | 4941 | 7490 | 5624 | 2281 | 26061 |

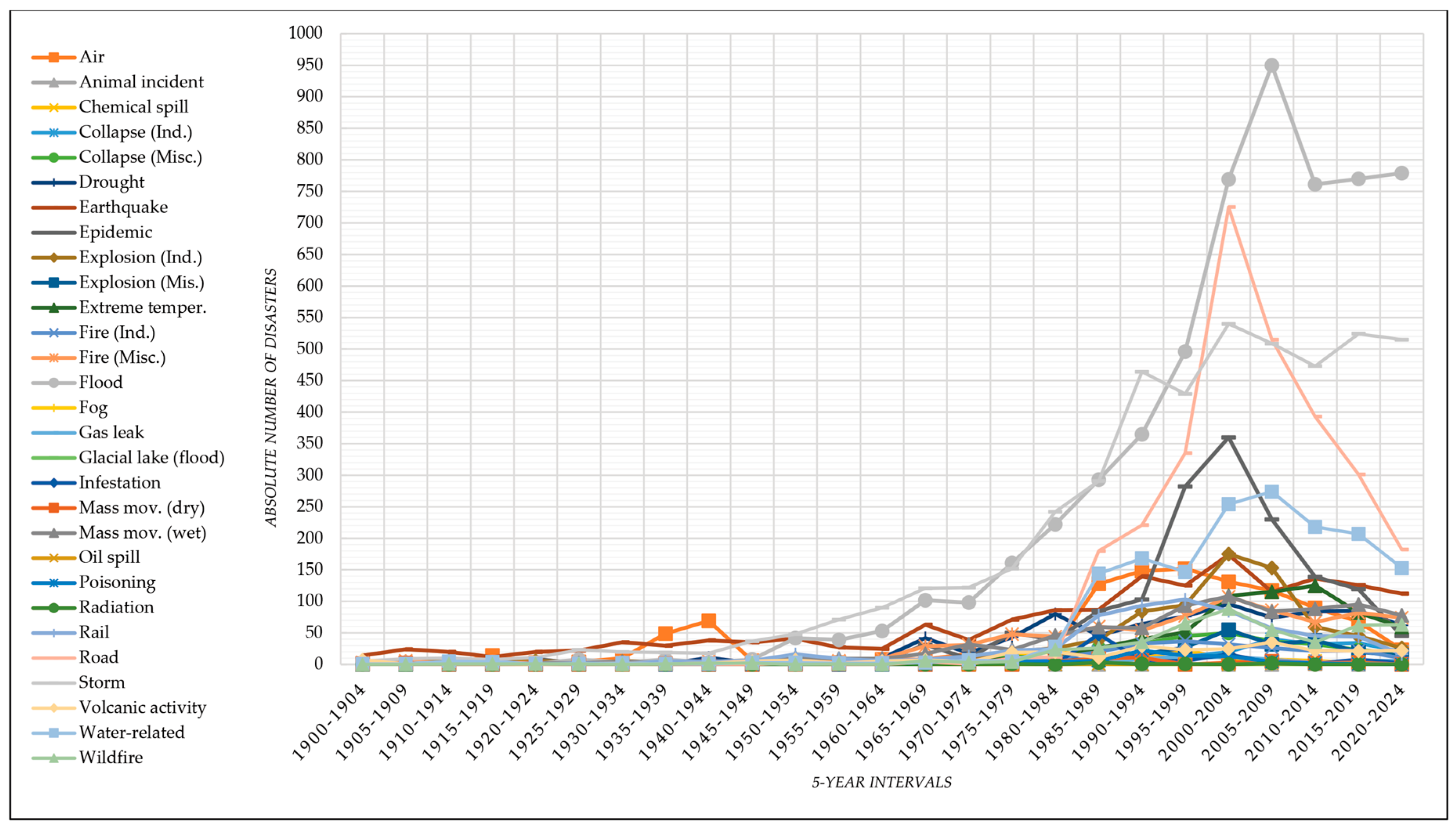

| Disaster Type |

1900-1904 | 1905-1909 | 1910-1914 | 1915-1919 | 1920-1924 | 1925-1929 | 1930-1934 | 1935-1939 | 1940-1944 | 1945-1949 | 1950-1954 | 1955-1959 | 1960-1964 | 1965-1969 | 1970-1974 | 1975-1979 | 1980-1984 | 1985-1989 | 1990-1994 | 1995-1999 | 2000-2004 | 2005-2009 | 2010-2014 | 2015-2019 | 2020-2024 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Air | 0 | 0 | 1 | 14 | 3 | 4 | 10 | 49 | 69 | 6 | 3 | 3 | 8 | 8 | 17 | 12 | 27 | 128 | 148 | 152 | 131 | 117 | 90 | 68 | 23 |

| Animal incident | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Chemical spill | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 16 | 20 | 13 | 11 | 23 | 8 | 8 | 6 | 1 | 0 |

| Collapse (Ind.) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 5 | 7 | 9 | 12 | 20 | 40 | 32 | 34 | 20 |

| Collapse (Misc.) | 0 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 3 | 4 | 3 | 3 | 13 | 10 | 26 | 33 | 45 | 50 | 37 | 32 | 23 | 16 |

| Drought | 3 | 1 | 9 | 1 | 3 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 11 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 10 | 42 | 18 | 43 | 80 | 46 | 64 | 76 | 96 | 74 | 84 | 85 | 62 |

| Earthquake | 14 | 24 | 20 | 12 | 20 | 22 | 35 | 30 | 38 | 35 | 41 | 27 | 25 | 63 | 39 | 71 | 86 | 87 | 140 | 125 | 174 | 115 | 136 | 126 | 112 |

| Epidemic | 2 | 3 | 1 | 5 | 9 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 6 | 31 | 9 | 50 | 39 | 85 | 103 | 282 | 360 | 230 | 139 | 119 | 45 |

| Explosion (Ind.) | 1 | 4 | 5 | 2 | 6 | 3 | 5 | 5 | 2 | 6 | 6 | 5 | 3 | 3 | 10 | 20 | 26 | 39 | 84 | 94 | 175 | 153 | 59 | 45 | 26 |

| Explosion (Mis.) | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 1 | 9 | 7 | 16 | 27 | 55 | 32 | 38 | 20 | 14 |

| Extreme temper. | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 5 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 9 | 11 | 26 | 40 | 51 | 109 | 115 | 125 | 82 | 59 |

| Fire (Ind.) | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 4 | 9 | 20 | 33 | 37 | 32 | 26 | 21 | 22 | 10 |

| Fire (Misc.) | 3 | 6 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 5 | 3 | 1 | 6 | 9 | 29 | 31 | 48 | 44 | 60 | 54 | 77 | 107 | 86 | 67 | 82 | 74 |

| Flood | 3 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 8 | 3 | 8 | 3 | 8 | 42 | 39 | 53 | 102 | 98 | 161 | 222 | 293 | 365 | 496 | 769 | 950 | 761 | 770 | 779 |

| Fog | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Gas leak | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 3 | 2 | 0 | 10 | 10 | 12 | 8 | 2 | 6 | 6 |

| Glacial lake (flood) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 4 |

| Infestation | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 3 | 0 | 48 | 5 | 6 | 16 | 2 | 1 | 8 | 2 |

| Mass mov. (dry) | 1 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 5 | 9 | 11 | 0 | 3 | 5 | 2 | 3 | 0 |

| Mass mov. (wet) | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 4 | 2 | 1 | 3 | 11 | 9 | 9 | 17 | 32 | 23 | 46 | 59 | 58 | 93 | 108 | 84 | 88 | 95 | 78 |

| Oil spill | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 0 |

| Poisoning | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 3 | 4 | 4 | 6 | 22 | 14 | 13 | 4 | 2 | 1 | 0 |

| Radiation | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Rail | 1 | 1 | 1 | 5 | 0 | 2 | 1 | 5 | 4 | 6 | 16 | 9 | 6 | 8 | 13 | 22 | 25 | 78 | 93 | 103 | 85 | 57 | 45 | 44 | 16 |

| Road | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 1 | 10 | 12 | 180 | 221 | 335 | 725 | 515 | 393 | 301 | 182 |

| Storm | 5 | 9 | 10 | 8 | 11 | 23 | 20 | 19 | 18 | 37 | 48 | 71 | 90 | 121 | 122 | 152 | 242 | 291 | 464 | 429 | 540 | 509 | 473 | 524 | 515 |

| Volcanic activity | 7 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 5 | 7 | 2 | 5 | 7 | 4 | 19 | 20 | 11 | 29 | 23 | 25 | 35 | 22 | 21 | 22 |

| Water-related | 1 | 1 | 5 | 4 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 7 | 5 | 28 | 144 | 168 | 147 | 254 | 274 | 218 | 207 | 153 |

| Wildfire | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 6 | 3 | 4 | 23 | 26 | 35 | 65 | 88 | 55 | 35 | 62 | 63 |

| Total | 86 | 114 | 122 | 120 | 122 | 142 | 176 | 256 | 318 | 238 | 384 | 372 | 474 | 908 | 848 | 1394 | 1990 | 3386 | 4434 | 5448 | 7910 | 7070 | 5746 | 5502 | 4562 |

| Disaster Type | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Total | Trend | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (n) | (%) | ||||||||||||||

| Air | 36 | 20 | 40 | 66 | 26 | 16 | 744 | 39 | 31 | 30 | 24 | 19 | 1091 | 4.123 | AA |

| Animal incident | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0.004 | BA |

| Chemical spill | 0 | 2 | 1 | 7 | 0 | 0 | 86 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 108 | 0.408 | BA |

| Collapse (Industrial) | 7 | 7 | 13 | 18 | 17 | 6 | 62 | 9 | 6 | 9 | 21 | 9 | 184 | 0.695 | BA |

| Collapse (Miscellaneous) | 15 | 12 | 14 | 14 | 7 | 11 | 181 | 15 | 2 | 13 | 13 | 8 | 305 | 1.153 | BA |

| Drought | 44 | 326 | 77 | 34 | 30 | 18 | 46 | 64 | 40 | 43 | 61 | 30 | 813 | 3.072 | BA |

| Earthquake | 197 | 92 | 316 | 190 | 48 | 37 | 201 | 185 | 91 | 32 | 83 | 145 | 1617 | 6.11 | AA |

| Epidemic | 63 | 75 | 75 | 42 | 49 | 220 | 701 | 57 | 38 | 83 | 79 | 44 | 1526 | 5.766 | AA |

| Explosion (Industrial) | 24 | 23 | 32 | 70 | 39 | 30 | 411 | 34 | 26 | 25 | 46 | 27 | 787 | 2.974 | BA |

| Explosion (Miscellaneous) | 12 | 8 | 13 | 13 | 10 | 9 | 99 | 20 | 16 | 7 | 7 | 8 | 222 | 0.839 | BA |

| Extreme temperature | 98 | 81 | 35 | 34 | 10 | 10 | 280 | 49 | 11 | 5 | 6 | 33 | 652 | 2.464 | BA |

| Fire (Industrial) | 7 | 6 | 11 | 16 | 6 | 7 | 121 | 8 | 11 | 9 | 8 | 10 | 220 | 0.831 | BA |

| Fire (Miscellaneous) | 38 | 35 | 44 | 60 | 19 | 20 | 440 | 35 | 24 | 26 | 30 | 33 | 804 | 3.038 | BA |

| Flood | 592 | 304 | 390 | 306 | 290 | 192 | 2072 | 400 | 403 | 374 | 356 | 262 | 5941 | 22.449 | AA |

| Fog | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0.004 | BA |

| Gas leak | 0 | 2 | 2 | 10 | 2 | 8 | 28 | 6 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 62 | 0.234 | BA |

| Glacial lake outburst flood | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 0.015 | BA |

| Impact | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0.004 | BA |

| Industrial accident (General) | 8 | 6 | 4 | 15 | 8 | 6 | 40 | 11 | 6 | 4 | 11 | 7 | 126 | 0.476 | BA |

| Infestation | 0 | 8 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 71 | 8 | 3 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 95 | 0.359 | BA |

| Mass movement (dry) | 2 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 37 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 45 | 0.17 | BA |

| Mass movement (wet) | 51 | 61 | 43 | 44 | 34 | 19 | 427 | 41 | 23 | 29 | 24 | 31 | 827 | 3.125 | A |

| Miscellaneous accident | 16 | 21 | 23 | 33 | 5 | 15 | 85 | 15 | 14 | 14 | 20 | 15 | 276 | 1.043 | BA |

| Oil spill | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 8 | 0.03 | BA |

| Poisoning | 0 | 5 | 8 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 56 | 0 | 1 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 76 | 0.287 | BA |

| Radiation | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 6 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 9 | 0.034 | BA |

| Rail | 13 | 13 | 28 | 44 | 13 | 11 | 453 | 24 | 7 | 17 | 19 | 4 | 646 | 2.441 | BA |

| Road | 166 | 95 | 140 | 128 | 109 | 135 | 1326 | 189 | 153 | 158 | 166 | 117 | 2882 | 10.89 | AA |

| Storm | 345 | 184 | 344 | 259 | 349 | 95 | 2146 | 217 | 191 | 218 | 211 | 192 | 4751 | 17.953 | AA |

| Volcanic activity | 17 | 2 | 5 | 11 | 7 | 67 | 120 | 4 | 9 | 3 | 10 | 19 | 274 | 1.035 | BA |

| Water-related | 94 | 72 | 106 | 152 | 62 | 62 | 718 | 75 | 71 | 84 | 89 | 50 | 1635 | 6.178 | AA |

| Wildfire | 26 | 15 | 28 | 21 | 15 | 12 | 239 | 55 | 20 | 20 | 11 | 13 | 475 | 1.795 | BA |

| Decade | Natural disasters | Man-made (tech.) disasters | Total | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fatalities | Injuries | Economic losses | Fatalities | Injuries | Economic losses | Fatalities | Injuries | Economic losses | |

| 1900-1910 | 4,472,477 | 2,549 | 1,373,800 | 5,766 | 2 | 0 | 4,478,243 | 2,551 | 1,373,800 |

| 1911-1920 | 3,334,004 | 2,955 | 600,000 | 10,752 | 9,306 | 2,500 | 3,344,756 | 12,261 | 602,500 |

| 1921-1930 | 8,561,918 | 109,109 | 1,004,230 | 7,139 | 1,596 | 100,000 | 8,569,057 | 110,705 | 1,104,230 |

| 1931-1940 | 4,629,968 | 112,403 | 3,342,000 | 5,579 | 511 | 0 | 4,635,547 | 112,914 | 3,342,000 |

| 1941-1950 | 3,878,897 | 69,329 | 3,136,700 | 11,165 | 2,258 | 6,000 | 3,890,062 | 71,587 | 3,142,700 |

| 1951-1960 | 2,127,944 | 24,642 | 6,090,480 | 10,979 | 6,241 | 218,000 | 2,138,923 | 30,883 | 6,308,480 |

| 1961-1970 | 1,751,347 | 784,522 | 18,633,100 | 6,446 | 5,155 | 159,972 | 1,757,793 | 789,677 | 18,793,072 |

| 1971-1980 | 998,508 | 552,541 | 53,753,225 | 17,244 | 22,809 | 76,193 | 1,015,752 | 575,350 | 53,829,418 |

| 1981-1990 | 796,062 | 317,353 | 183,523,629 | 58,382 | 159,620 | 6,469,293 | 854,444 | 476,973 | 189,992,922 |

| 1991-2000 | 527,413 | 1,588,807 | 701,281,224 | 86,149 | 80,174 | 4,410,769 | 613,562 | 1,668,981 | 705,691,993 |

| 2001-2010 | 839,418 | 3,282,010 | 892,099,162 | 97,166 | 89,617 | 14,746,682 | 936,584 | 3,371,627 | 906,845,844 |

| 2011-2020 | 503,400 | 3,241,477 | 1,706,627,174 | 62,715 | 59,375 | 20,969,701 | 566,115 | 3,300,852 | 1,727,596,875 |

| 2021-2024 | 199,314 | 627,655 | 861,127,190 | 15,132 | 24,593 | 16,750,000 | 214,446 | 652,248 | 877,877,190 |

| 5-year period |

Natural disasters | Man-made (tech.) disasters | Total | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fatalities | Injuries | Economic Losses | Fatalities | Injuries | Economic Losses |

Fatalities | Injuries | Economic Losses |

|

| 1900-1905 | 1523244 | 251 | 535000 | 2230 | 2 | 0 | 1525474 | 253 | 535000 |

| 1906-1910 | 2949233 | 2298 | 838800 | 3536 | 0 | 0 | 2952769 | 2298 | 838800 |

| 1911-1915 | 311175 | 2828 | 275000 | 5232 | 20 | 0 | 316407 | 2848 | 275000 |

| 1916-1920 | 3022829 | 127 | 325000 | 5520 | 9286 | 2500 | 3028349 | 9413 | 327500 |

| 1921-1925 | 5065612 | 103900 | 663000 | 6412 | 1500 | 100000 | 5072024 | 105400 | 763000 |

| 1926-1930 | 3496306 | 5209 | 341230 | 727 | 96 | 0 | 3497033 | 5305 | 341230 |

| 1931-1935 | 3772100 | 9045 | 1629000 | 3021 | 324 | 0 | 3775121 | 9369 | 1629000 |

| 1936-1940 | 857868 | 103358 | 1713000 | 2558 | 187 | 0 | 860426 | 103545 | 1713000 |

| 1941-1945 | 3569724 | 48909 | 1325500 | 5208 | 1181 | 0 | 3574932 | 50090 | 1325500 |

| 1946-1950 | 309173 | 20420 | 1811200 | 5957 | 1077 | 6000 | 315130 | 21497 | 1817200 |

| 1951-1955 | 86802 | 11243 | 3775180 | 5377 | 1949 | 178000 | 92179 | 13192 | 3953180 |

| 1956-1960 | 2041142 | 13399 | 2315300 | 5602 | 4292 | 40000 | 2046744 | 17691 | 2355300 |

| 1961-1965 | 124667 | 16119 | 8163881 | 3394 | 2818 | 49759 | 128061 | 18937 | 8213640 |

| 1966-1970 | 1626680 | 768403 | 10469219 | 3052 | 2337 | 110213 | 1629732 | 770740 | 10579432 |

| 1971-1975 | 623353 | 218953 | 15582333 | 6779 | 12990 | 3843 | 630132 | 231943 | 15586176 |

| 1976-1980 | 375155 | 333588 | 38170892 | 10465 | 9819 | 72350 | 385620 | 343407 | 38243242 |

| 1981-1985 | 633887 | 155979 | 84139472 | 17264 | 140392 | 761976 | 651151 | 296371 | 84901448 |

| 1986-1990 | 162175 | 161374 | 99384157 | 41118 | 19228 | 5707317 | 203293 | 180602 | 105091474 |

| 1991-1995 | 299078 | 818151 | 264087752 | 44158 | 32120 | 1363916 | 343236 | 850271 | 265451668 |

| 1996-2000 | 228335 | 770656 | 437193472 | 41991 | 48054 | 3046853 | 270326 | 818710 | 440240325 |

| 2001-2005 | 435658 | 2437898 | 331597225 | 54143 | 54209 | 11607124 | 489801 | 2492107 | 343204349 |

| 2006-2010 | 403760 | 844112 | 560501937 | 43023 | 35408 | 3139558 | 446783 | 879520 | 563641495 |

| 2011-2015 | 418756 | 1087793 | 871742990 | 32710 | 31140 | 20964701 | 451466 | 1118933 | 892707691 |

| 2016-2020 | 84644 | 2153684 | 834884184 | 30005 | 28235 | 5000 | 114649 | 2181919 | 834889184 |

| 2021-2024 | 199314 | 627655 | 861127190 | 15132 | 24593 | 16750000 | 214446 | 652248 | 877877190 |

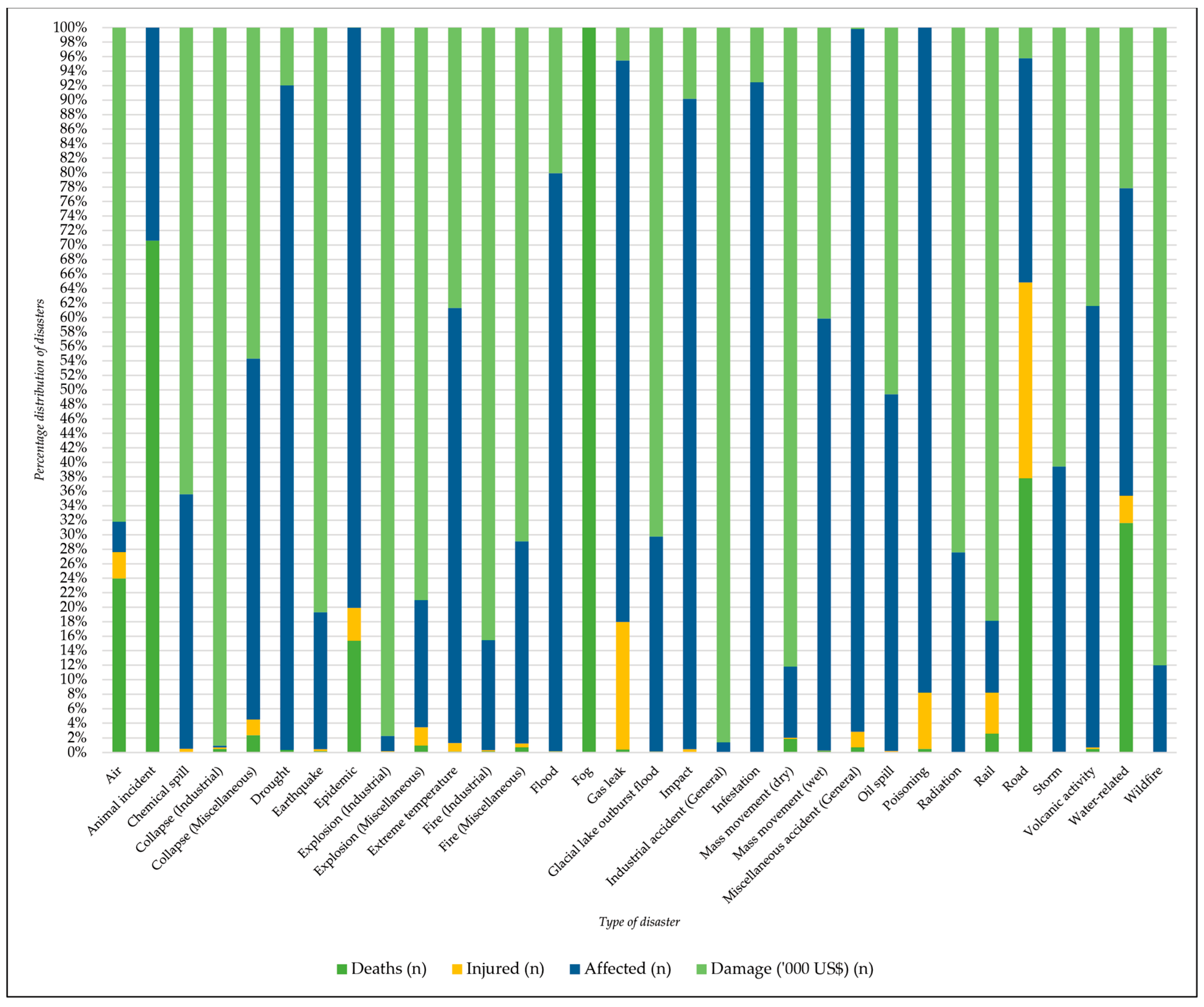

| Disaster Type | Deaths | Injured | Affected | Damage ('000 US$) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (n) | (%) | (n) | (%) | (n) | (%) | (n) | (%) | |

| Air | 50,689 | 0.154 | 7,620 | 0.068 | 8,846 | 0.0 | 144,100 | 0.003 |

| Animal incident | 12 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 5 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 |

| Chemical spill | 610 | 0.002 | 8,773 | 0.078 | 652,981 | 0.008 | 1,198,954 | 0.027 |

| Collapse (Industrial) | 7,099 | 0.022 | 2,450 | 0.022 | 3,353 | 0.0 | 1,335,000 | 0.03 |

| Collapse (Miscellaneous) | 14,830 | 0.045 | 13,024 | 0.117 | 309,514 | 0.004 | 283,800 | 0.006 |

| Drought | 11,734,272 | 35.54 | 32 | 0.0 | 2,964,996,768 | 34.146 | 257,581,674 | 5.728 |

| Earthquake | 2,407,717 | 7.293 | 2,945,052 | 26.35 | 228,214,673 | 2.628 | 975,785,916 | 21.701 |

| Epidemic | 9,622,343 | 29.14 | 2,836,719 | 25.38 | 50,095,829 | 0.577 | 7 | 0.0 |

| Explosion (Industrial) | 36,814 | 0.112 | 41,850 | 0.374 | 864,341 | 0.01 | 40,421,674 | 0.899 |

| Explosion (Miscellaneous) | 7,624 | 0.023 | 19,231 | 0.172 | 137,527 | 0.002 | 619,100 | 0.014 |

| Extreme temperature | 256,413 | 0.777 | 2,066,936 | 18.49 | 107,678,810 | 1.24 | 69,468,343 | 1.545 |

| Fire (Industrial) | 5,522 | 0.017 | 5,211 | 0.047 | 465,362 | 0.005 | 2,608,005 | 0.058 |

| Fire (Miscellaneous) | 36,590 | 0.111 | 24,022 | 0.215 | 1,368,383 | 0.016 | 3,485,470 | 0.078 |

| Flood | 7,011,404 | 21.23 | 1,398,042 | 12.50 | 3,997,629,671 | 46.039 | 1,007,889,805 | 22.415 |

| Fog | 4,000 | 0.012 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 |

| Gas leak | 2,906 | 0.009 | 116,280 | 1.04 | 513,932 | 0.006 | 30,000 | 0.001 |

| Glacial lake outburst flood | 439 | 0.001 | 24 | 0.0 | 88,424 | 0.001 | 210,000 | 0.005 |

| Impact | 0 | 0.0 | 1,491 | 0.013 | 301,491 | 0.003 | 33,000 | 0.001 |

| Industrial accident (General) | 5,207 | 0.016 | 1,552 | 0.014 | 135,987 | 0.002 | 9,960,407 | 0.222 |

| Infestation | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 2,802,200 | 0.032 | 229,200 | 0.005 |

| Mass movement (dry) | 4,486 | 0.014 | 373 | 0.003 | 23,117 | 0.0 | 209,000 | 0.005 |

| Mass movement (wet) | 68,636 | 0.208 | 12,705 | 0.114 | 16,823,502 | 0.194 | 11,347,044 | 0.252 |

| Miscellaneous accident (General) | 14,279 | 0.043 | 40,666 | 0.364 | 1,880,052 | 0.022 | 4,000 | 0.0 |

| Oil spill | 1 | 0.0 | 120 | 0.001 | 29,137 | 0.0 | 30,000 | 0.001 |

| Poisoning | 3,578 | 0.011 | 54,442 | 0.487 | 648,522 | 0.007 | 0 | 0.0 |

| Radiation | 86 | 0.0 | 1,958 | 0.018 | 1,064,201 | 0.012 | 2,800,000 | 0.062 |

| Rail | 28,730 | 0.087 | 61,744 | 0.552 | 109,453 | 0.001 | 903,000 | 0.02 |

| Road | 68,812 | 0.208 | 49,184 | 0.44 | 56,306 | 0.001 | 7,700 | 0.0 |

| Storm | 1,418,647 | 4.297 | 1,411,425 | 12.62 | 1,277,565,968 | 14.713 | 1,967,141,984 | 43.748 |

| Volcanic activity | 86,935 | 0.263 | 26,564 | 0.238 | 10,032,658 | 0.116 | 6,327,912 | 0.141 |

| Water-related | 111,237 | 0.337 | 13,130 | 0.117 | 149,256 | 0.002 | 77,900 | 0.002 |

| Wildfire | 5,366 | 0.016 | 15,989 | 0.143 | 18,531,582 | 0.213 | 136,368,030 | 3.033 |

| Total | 33,015,284 | 100.0 | 11,176,609 | 100.0 | 8,683,181,851 | 100.0 | 4,496,501,025 | 100.0 |

| Recommendation | Description | Short-term | Long-term | National | Local |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Integration of disaster risk reduction | Integrate strategies for disaster risk reduction into the overall national development agenda | ✓ | ↑ | ↑ | ↓ |

| Enhancement of early warning systems | Enhance early warning systems through investments in advanced technology, infrastructure improvements, and comprehensive training programs | ✓ | ✓ | ↑ | ↑ |

| Promotion of climate resilience | Focus on climate resilience by adopting sustainable practices and implementing green infrastructure projects | ✓ | ↑ | ↓ | |

| Strengthening industrial safety | Upgrade safety protocols and strengthen regulatory frameworks governing industrial operations | ✓ | ✓ | ↑ | ↓ |

| Community-based disaster risk management | Empower communities by providing education, training, and opportunities for active involvement in disaster management | ✓ | ✓ | ↓ | ↑ |

| Investing in research and development | Promote research and development to discover innovative solutions for reducing disaster risks on the basis of a better understanding of the interconnections of risks | ✓ | ↑ | ↓ | |

| Regional cooperation and information sharing | Foster international cooperation and improve data sharing mechanisms for more effective disaster preparedness and response | ✓ | ✓ | ↑ | ↓ |

| Adapting infrastructure and urban planning | Construct resilient infrastructure and apply sustainable urban planning methods to reduce disaster impacts | ✓ | ↑ | ↓ | |