Submitted:

02 August 2024

Posted:

02 August 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

Introduction

Tumor Microenvironment of PDAC

Targeting the Desmoplastic Barrier in PDAC

Neutralizing Immunosuppressive Cells

Overcoming Metabolic Barriers

Blocking Immune Checkpoints

Potential Novel Approaches to PDAC Immunotherapy

Enhancing Antigen Presentation

Cancer Vaccines

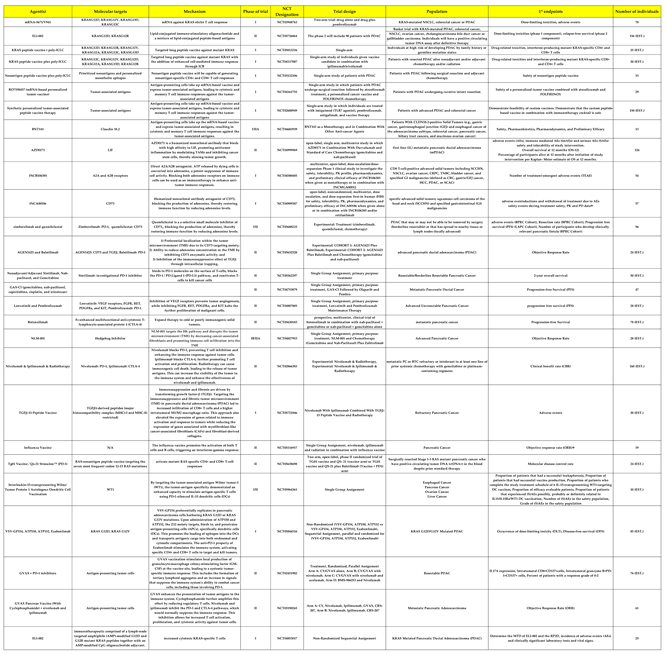

Neoantigen-Based Peptide Vaccines for Patients with Advanced Pancreatic Cancer Refractory to Standard Treatment

Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- “Annual Cancer Facts & Figures | American Cancer Society.” Accessed: Jul. 01, 2024. [Online]. Available: https://www.cancer.org/research/cancer-facts-statistics/all-cancer-facts-figures.html.

- L. Marstrand-Daucé, D. Lorenzo, A. Chassac, P. Nicole, A. Couvelard, and C. Haumaitre, “Acinar-to-Ductal Metaplasia (ADM): On the Road to Pancreatic Intraepithelial Neoplasia (PanIN) and Pancreatic Cancer,” Int. J. Mol. Sci., vol. 24, no. 12, p. 9946, Jun. 2023. [CrossRef]

- V. Tonini and M. Zanni, “Pancreatic cancer in 2021: What you need to know to win,” World J. Gastroenterol., vol. 27, no. 35, pp. 5851–5889, Sep. 2021. [CrossRef]

- D. R. Principe, P. W. Underwood, M. Korc, J. G. Trevino, H. G. Munshi, and A. Rana, “The Current Treatment Paradigm for Pancreatic Ductal Adenocarcinoma and Barriers to Therapeutic Efficacy,” Front. Oncol., vol. 11, p. 688377, Jul. 2021. [CrossRef]

- L.-H. Truong and S. Pauklin, “Pancreatic Cancer Microenvironment and Cellular Composition: Current Understandings and Therapeutic Approaches,” Cancers, vol. 13, no. 19, p. 5028, Oct. 2021. [CrossRef]

- A. N. Hosein, R. A. Brekken, and A. Maitra, “Pancreatic cancer stroma: an update on therapeutic targeting strategies,” Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol., vol. 17, no. 8, pp. 487–505, Aug. 2020. [CrossRef]

- J. S. Bowers, S. R. Bailey, M. P. Rubinstein, C. M. Paulos, and E. R. Camp, “Genomics meets immunity in pancreatic cancer: Current research and future dire4ctions for pancreatic adenocarcinoma immunotherapy,” Oncol. Rev., vol. 13, no. 2, Aug. 2019. [CrossRef]

- S. K. Daniel, K. M. Sullivan, K. P. Labadie, and V. G. Pillarisetty, “Hypoxia as a barrier to immunotherapy in pancreatic adenocarcinoma,” Clin. Transl. Med., vol. 8, no. 1, p. e10, Dec. 2019. [CrossRef]

- S. K. Gautam, S. K. Batra, and M. Jain, “Molecular and metabolic regulation of immunosuppression in metastatic pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma,” Mol. Cancer, vol. 22, no. 1, p. 118, Jul. 2023. [CrossRef]

- J. Fan, M.-F. Wang, H.-L. Chen, D. Shang, J. K. Das, and J. Song, “Current advances and outlooks in immunotherapy for pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma,” Mol. Cancer, vol. 19, no. 1, p. 32, Dec. 2020. [CrossRef]

- T. Murakami, Y. Hiroshima, R. Matsuyama, Y. Homma, R. M. Hoffman, and I. Endo, “Role of the tumor microenvironment in pancreatic cancer,” Ann. Gastroenterol. Surg., vol. 3, no. 2, pp. 130–137, Mar. 2019. [CrossRef]

- B. Ren et al., “Tumor microenvironment participates in metastasis of pancreatic cancer,” Mol. Cancer, vol. 17, no. 1, p. 108, Dec. 2018. [CrossRef]

- M. Huber et al., “The Immune Microenvironment in Pancreatic Cancer,” Int. J. Mol. Sci., vol. 21, no. 19, p. 7307, Oct. 2020. [CrossRef]

- M. Pascual-García et al., “LIF regulates CXCL9 in tumor-associated macrophages and prevents CD8+ T cell tumor-infiltration impairing anti-PD1 therapy,” Nat. Commun., vol. 10, no. 1, p. 2416, Jun. 2019. [CrossRef]

- R. Akbani et al., “Genomic Classification of Cutaneous Melanoma,” Cell, vol. 161, no. 7, pp. 1681–1696, Jun. 2015. [CrossRef]

- M. Łuksza et al., “Neoantigen quality predicts immunoediting in survivors of pancreatic cancer,” Nature, vol. 606, no. 7913, pp. 389–395, Jun. 2022. [CrossRef]

- Australian Pancreatic Cancer Genome Initiative et al., “Identification of unique neoantigen qualities in long-term survivors of pancreatic cancer,” Nature, vol. 551, no. 7681, pp. 512–516, Nov. 2017. [CrossRef]

- M. Feng et al., “PD-1/PD-L1 and immunotherapy for pancreatic cancer,” Cancer Lett., vol. 407, pp. 57–65, Oct. 2017. [CrossRef]

- W. Zou and L. Chen, “Inhibitory B7-family molecules in the tumour microenvironment,” Nat. Rev. Immunol., vol. 8, no. 6, pp. 467–477, Jun. 2008. [CrossRef]

- J. Tao et al., “Targeting hypoxic tumor microenvironment in pancreatic cancer,” J. Hematol. Oncol.J Hematol Oncol, vol. 14, no. 1, p. 14, Jan. 2021. [CrossRef]

- Q. Hu et al., “UHRF1 promotes aerobic glycolysis and proliferation via suppression of SIRT4 in pancreatic cancer,” Cancer Lett., vol. 452, pp. 226–236, Jun. 2019. [CrossRef]

- M. Erkan et al., “The role of stroma in pancreatic cancer: diagnostic and therapeutic implications,” Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol., vol. 9, no. 8, pp. 454–467, Aug. 2012. [CrossRef]

- K. Yamamoto et al., “Autophagy promotes immune evasion of pancreatic cancer by degrading MHC-I,” Nature, vol. 581, no. 7806, pp. 100–105, May 2020. [CrossRef]

- K. Yamamoto, A. Venida, R. M. Perera, and A. C. Kimmelman, “Selective autophagy of MHC-I promotes immune evasion of pancreatic cancer,” Autophagy, vol. 16, no. 8, pp. 1524–1525, Aug. 2020. [CrossRef]

- I. A. York and K. L. Rock, “ANTIGEN PROCESSING AND PRESENTATION BY THE CLASS I MAJOR HISTOCOMPATIBILITY COMPLEX,” Annu. Rev. Immunol., vol. 14, no. 1, pp. 369–396, Apr. 1996. [CrossRef]

- N. Pu et al., “Cell-intrinsic PD-1 promotes proliferation in pancreatic cancer by targeting CYR61/CTGF via the hippo pathway,” Cancer Lett., vol. 460, pp. 42–53, Sep. 2019. [CrossRef]

- E. Hessmann et al., “Microenvironmental Determinants of Pancreatic Cancer,” Physiol. Rev., vol. 100, no. 4, pp. 1707–1751, Oct. 2020. [CrossRef]

- S. Tsukita and M. Furuse, “The Structure and Function of Claudins, Cell Adhesion Molecules at Tight Junctions,” Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci., vol. 915, no. 1, pp. 129–135, Dec. 2000. [CrossRef]

- S. Tsukita, H. Tanaka, and A. Tamura, “The Claudins: From Tight Junctions to Biological Systems,” Trends Biochem. Sci., vol. 44, no. 2, pp. 141–152, Feb. 2019. [CrossRef]

- T. Otani and M. Furuse, “Tight Junction Structure and Function Revisited,” Trends Cell Biol., vol. 30, no. 10, pp. 805–817, Oct. 2020. [CrossRef]

- K. J. Hewitt, R. Agarwal, and P. J. Morin, “The claudin gene family: expression in normal and neoplastic tissues,” BMC Cancer, vol. 6, no. 1, p. 186, Dec. 2006. [CrossRef]

- U. Sahin et al., “Claudin-18 Splice Variant 2 Is a Pan-Cancer Target Suitable for Therapeutic Antibody Development,” Clin. Cancer Res., vol. 14, no. 23, pp. 7624–7634, Dec. 2008. [CrossRef]

- W. Cao et al., “Claudin18.2 is a novel molecular biomarker for tumor-targeted immunotherapy,” Biomark. Res., vol. 10, no. 1, p. 38, Dec. 2022. [CrossRef]

- H. Bähr-Mahmud et al., “Preclinical characterization of an mRNA-encoded anti-Claudin 18.2 antibody,” OncoImmunology, vol. 12, no. 1, p. 2255041, Dec. 2023. [CrossRef]

- K. P. Papadopoulos et al., “A phase I/II dose escalation and expansion trial to evaluate safety and preliminary efficacy of BNT141 in patients with claudin-18.2-positive solid tumors.,” J. Clin. Oncol., vol. 41, no. 16_suppl, pp. TPS2670–TPS2670, Jun. 2023. [CrossRef]

- K. Shitara et al., “Zolbetuximab plus mFOLFOX6 in patients with CLDN18.2-positive, HER2-negative, untreated, locally advanced unresectable or metastatic gastric or gastro-oesophageal junction adenocarcinoma (SPOTLIGHT): a multicentre, randomised, double-blind, phase 3 trial,” The Lancet, vol. 401, no. 10389, pp. 1655–1668, May 2023. [CrossRef]

- S. S. Diebold, T. Kaisho, H. Hemmi, S. Akira, and C. Reis E Sousa, “Innate Antiviral Responses by Means of TLR7-Mediated Recognition of Single-Stranded RNA,” Science, vol. 303, no. 5663, pp. 1529–1531, Mar. 2004. [CrossRef]

- Z. Zhang et al., “Structural Analysis Reveals that Toll-like Receptor 7 Is a Dual Receptor for Guanosine and Single-Stranded RNA,” Immunity, vol. 45, no. 4, pp. 737–748, Oct. 2016. [CrossRef]

- G. Landskron, M. De La Fuente, P. Thuwajit, C. Thuwajit, and M. A. Hermoso, “Chronic Inflammation and Cytokines in the Tumor Microenvironment,” J. Immunol. Res., vol. 2014, pp. 1–19, 2014. [CrossRef]

- G. A. Gastl et al., “Interleukin-10 production by human carcinoma cell lines and its relationship to interleukin-6 expression,” Int. J. Cancer, vol. 55, no. 1, pp. 96–101, Aug. 1993. [CrossRef]

- R. Inamoto, N. Takahashi, and Y. Yamada, “Claudin18.2 in Advanced Gastric Cancer,” Cancers, vol. 15, no. 24, p. 5742, Dec. 2023. [CrossRef]

- W. L. Byrne, K. H. G. Mills, J. A. Lederer, and G. C. O’Sullivan, “Targeting Regulatory T Cells in Cancer,” Cancer Res., vol. 71, no. 22, pp. 6915–6920, Nov. 2011. [CrossRef]

- V. Fleming et al., “Targeting Myeloid-Derived Suppressor Cells to Bypass Tumor-Induced Immunosuppression,” Front. Immunol., vol. 9, p. 398, Mar. 2018. [CrossRef]

- Y. Ohue and H. Nishikawa, “Regulatory T (Treg) cells in cancer: Can Treg cells be a new therapeutic target?,” Cancer Sci., vol. 110, no. 7, pp. 2080–2089, Jul. 2019. [CrossRef]

- J.-E. Jang, C. H. Hajdu, C. Liot, G. Miller, M. L. Dustin, and D. Bar-Sagi, “Crosstalk between Regulatory T Cells and Tumor-Associated Dendritic Cells Negates Anti-tumor Immunity in Pancreatic Cancer,” Cell Rep., vol. 20, no. 3, pp. 558–571, Jul. 2017. [CrossRef]

- I. M. Stromnes et al., “Targeted depletion of an MDSC subset unmasks pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma to adaptive immunity,” Gut, vol. 63, no. 11, pp. 1769–1781, Nov. 2014. [CrossRef]

- R. Trovato et al., “Immunosuppression by monocytic myeloid-derived suppressor cells in patients with pancreatic ductal carcinoma is orchestrated by STAT3,” J. Immunother. Cancer, vol. 7, no. 1, p. 255, Dec. 2019. [CrossRef]

- E. Eriksson, J. Wenthe, S. Irenaeus, A. Loskog, and G. Ullenhag, “Gemcitabine reduces MDSCs, tregs and TGFβ-1 while restoring the teff/treg ratio in patients with pancreatic cancer,” J. Transl. Med., vol. 14, no. 1, p. 282, Dec. 2016. [CrossRef]

- Y. Shi et al., “Targeting LIF-mediated paracrine interaction for pancreatic cancer therapy and monitoring,” Nature, vol. 569, no. 7754, pp. 131–135, May 2019. [CrossRef]

- F. Peng, J. Zhou, W. Sheng, D. Zhang, and M. Dong, “ [Expression and significance of leukemia inhibitory factor in human pancreatic cancer],” Zhonghua Yi Xue Za Zhi, vol. 94, no. 2, pp. 90–95, Jan. 2014.

- D. Wang et al., “Prognostic value of leukemia inhibitory factor and its receptor in pancreatic adenocarcinoma,” Future Oncol., vol. 16, no. 3, pp. 4461–4473, Jan. 2020. [CrossRef]

- E. Borazanci et al., “Phase I, first-in-human study of MSC-1 (AZD0171), a humanized anti-leukemia inhibitory factor monoclonal antibody, for advanced solid tumors,” ESMO Open, vol. 7, no. 4, p. 100530, Aug. 2022. [CrossRef]

- R. L. Williams et al., “Myeloid leukaemia inhibitory factor maintains the developmental potential of embryonic stem cells,” Nature, vol. 336, no. 6200, pp. 684–687, Dec. 1988. [CrossRef]

- C. J. Halbrook, M. Pasca Di Magliano, and C. A. Lyssiotis, “Tumor cross-talk networks promote growth and support immune evasion in pancreatic cancer,” Am. J. Physiol.-Gastrointest. Liver Physiol., vol. 315, no. 1, pp. G27–G35, Jul. 2018. [CrossRef]

- D. Saka et al., “Mechanisms of T-Cell Exhaustion in Pancreatic Cancer,” Cancers, vol. 12, no. 8, p. 2274, Aug. 2020. [CrossRef]

- F. Marcon et al., “NK cells in pancreatic cancer demonstrate impaired cytotoxicity and a regulatory IL-10 phenotype,” OncoImmunology, vol. 9, no. 1, p. 1845424, Jan. 2020. [CrossRef]

- R. Yang et al., “Conversion of ATP to adenosine by CD39 and CD73 in multiple myeloma can be successfully targeted together with adenosine receptor A2A blockade,” J. Immunother. Cancer, vol. 8, no. 1, p. e000610, May 2020. [CrossRef]

- D. Zahavi and J. Hodge, “Targeting Immunosuppressive Adenosine Signaling: A Review of Potential Immunotherapy Combination Strategies,” Int. J. Mol. Sci., vol. 24, no. 10, p. 8871, May 2023. [CrossRef]

- C. Kang, “Retifanlimab: First Approval,” Drugs, vol. 83, no. 8, pp. 731–737, Jun. 2023. [CrossRef]

- H. Wang et al., “Abstract LB157: Discovery and characterization of INCB106385: a novel A2A/A2B adenosine receptor antagonist, as a cancer immunotherapy,” Cancer Res., vol. 81, no. 13_Supplement, pp. LB157–LB157, Jul. 2021. [CrossRef]

- N. Bach, R. Winzer, E. Tolosa, W. Fiedler, and F. Brauneck, “The Clinical Significance of CD73 in Cancer,” Int. J. Mol. Sci., vol. 24, no. 14, p. 11759, Jul. 2023. [CrossRef]

- S. Stewart et al., “Abstract LB174: Discovery and preclinical characterization of INCA00186, a humanized monoclonal antibody antagonist of CD73, as a cancer immunotherapy,” Cancer Res., vol. 81, no. 13_Supplement, pp. LB174–LB174, Jul. 2021. [CrossRef]

- M. Hori and M. Kitakaze, “Adenosine, the heart, and coronary circulation.,” Hypertension, vol. 18, no. 5, pp. 565–574, Nov. 1991. [CrossRef]

- L. Belardinelli et al., “The A2A adenosine receptor mediates coronary vasodilation,” J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther., vol. 284, no. 3, pp. 1066–1073, Mar. 1998.

- B. Allard, S. Pommey, M. J. Smyth, and J. Stagg, “Targeting CD73 Enhances the Antitumor Activity of Anti-PD-1 and Anti-CTLA-4 mAbs,” Clin. Cancer Res., vol. 19, no. 20, pp. 5626–5635, Oct. 2013. [CrossRef]

- F. S. Regateiro et al., “Generation of anti-inflammatory adenosine byleukocytes is regulated by TGF-β,” Eur. J. Immunol., vol. 41, no. 10, pp. 2955–2965, Oct. 2011. [CrossRef]

- A. W. Tolcher et al., “Phase 1 first-in-human study of dalutrafusp alfa, an anti–CD73-TGF-β-trap bifunctional antibody, in patients with advanced solid tumors,” J. Immunother. Cancer, vol. 11, no. 2, p. e005267, Feb. 2023. [CrossRef]

- X. He and C. Xu, “Immune checkpoint signaling and cancer immunotherapy,” Cell Res., vol. 30, no. 8, pp. 660–669, Aug. 2020. [CrossRef]

- S. Lim et al., “Interplay between Immune Checkpoint Proteins and Cellular Metabolism,” Cancer Res., vol. 77, no. 6, pp. 1245–1249, Mar. 2017. [CrossRef]

- M. E. Keir, M. J. Butte, G. J. Freeman, and A. H. Sharpe, “PD-1 and Its Ligands in Tolerance and Immunity,” Annu. Rev. Immunol., vol. 26, no. 1, pp. 677–704, Apr. 2008. [CrossRef]

- J. B. A. G. Haanen and C. Robert, “Immune Checkpoint Inhibitors,” in Progress in Tumor Research, vol. 42, O. Michielin and G. Coukos, Eds., S. Karger AG, 2015, pp. 55–66. [CrossRef]

- J. R. Brahmer et al., “Safety and Activity of Anti–PD-L1 Antibody in Patients with Advanced Cancer,” N. Engl. J. Med., vol. 366, no. 26, pp. 2455–2465, Jun. 2012. [CrossRef]

- K. D. McCoy and G. Le Gros, “The role of CTLA-4 in the regulation of T cell immune responses,” Immunol. Cell Biol., vol. 77, no. 1, pp. 1–10, Feb. 1999. [CrossRef]

- F. A. Schildberg, S. R. Klein, G. J. Freeman, and A. H. Sharpe, “Coinhibitory Pathways in the B7-CD28 Ligand-Receptor Family,” Immunity, vol. 44, no. 5, pp. 955–972, May 2016. [CrossRef]

- A. Rotte, “Combination of CTLA-4 and PD-1 blockers for treatment of cancer,” J. Exp. Clin. Cancer Res., vol. 38, no. 1, p. 255, Dec. 2019. [CrossRef]

- M. Nishio et al., “First-line nivolumab plus ipilimumab in metastatic non-small cell lung cancer: 5-year outcomes in Japanese patients from CheckMate 227 Part 1,” Int. J. Clin. Oncol., vol. 28, no. 10, pp. 1354–1368, Oct. 2023. [CrossRef]

- F. S. Hodi et al., “Improved Survival with Ipilimumab in Patients with Metastatic Melanoma,” N. Engl. J. Med., vol. 363, no. 8, pp. 711–723, Aug. 2010. [CrossRef]

- M. Gao et al., “Direct therapeutic targeting of immune checkpoint PD-1 in pancreatic cancer,” Br. J. Cancer, vol. 120, no. 1, pp. 88–96, Jan. 2019. [CrossRef]

- N. Pu, W. Lou, and J. Yu, “PD-1 immunotherapy in pancreatic cancer: current status,” J. Pancreatol., vol. 2, no. 1, pp. 6–10, Mar. 2019. [CrossRef]

- L. Zhang, W. Mai, W. Jiang, and Q. Geng, “Sintilimab: A Promising Anti-Tumor PD-1 Antibody,” Front. Oncol., vol. 10, p. 594558, Nov. 2020. [CrossRef]

- J. S. Brown, R. Sundar, and J. Lopez, “Combining DNA damaging therapeutics with immunotherapy: more haste, less speed,” Br. J. Cancer, vol. 118, no. 3, pp. 312–324, Feb. 2018. [CrossRef]

- C. J. Langer et al., “Carboplatin and pemetrexed with or without pembrolizumab for advanced, non-squamous non-small-cell lung cancer: a randomised, phase 2 cohort of the open-label KEYNOTE-021 study,” Lancet Oncol., vol. 17, no. 11, pp. 1497–1508, Nov. 2016. [CrossRef]

- R. M. Poole, “Pembrolizumab: First Global Approval,” Drugs, vol. 74, no. 16, pp. 1973–1981, Oct. 2014. [CrossRef]

- E. D. Deeks, “Olaparib: First Global Approval,” Drugs, vol. 75, no. 2, pp. 231–240, Feb. 2015. [CrossRef]

- Z. Hao and P. Wang, “Lenvatinib in Management of Solid Tumors,” The Oncologist, vol. 25, no. 2, pp. e302–e310, Feb. 2020. [CrossRef]

- M. Kudo et al., “Lenvatinib versus sorafenib in first-line treatment of patients with unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma: a randomised phase 3 non-inferiority trial,” The Lancet, vol. 391, no. 10126, pp. 1163–1173, Mar. 2018. [CrossRef]

- M. Schlumberger et al., “Lenvatinib versus Placebo in Radioiodine-Refractory Thyroid Cancer,” N. Engl. J. Med., vol. 372, no. 7, pp. 621–630, Feb. 2015. [CrossRef]

- P. Waterhouse et al., “Lymphoproliferative Disorders with Early Lethality in Mice Deficient in Ctla-4,” Science, vol. 270, no. 5238, pp. 985–988, Nov. 1995. [CrossRef]

- E. A. Tivol, F. Borriello, A. N. Schweitzer, W. P. Lynch, J. A. Bluestone, and A. H. Sharpe, “Loss of CTLA-4 leads to massive lymphoproliferation and fatal multiorgan tissue destruction, revealing a critical negative regulatory role of CTLA-4,” Immunity, vol. 3, no. 5, pp. 541–547, Nov. 1995. [CrossRef]

- A. Bullock et al., “LBA O-9 Botensilimab, a novel innate/adaptive immune activator, plus balstilimab (anti-PD-1) for metastatic heavily pretreated microsatellite stable colorectal cancer,” Ann. Oncol., vol. 33, p. S376, Jun. 2022. [CrossRef]

- R. Balsano, V. Zanuso, A. Pirozzi, L. Rimassa, and S. Bozzarelli, “Pancreatic Ductal Adenocarcinoma and Immune Checkpoint Inhibitors: The Gray Curtain of Immunotherapy and Spikes of Lights,” Curr. Oncol., vol. 30, no. 4, pp. 3871–3885, Mar. 2023. [CrossRef]

- G. Germano et al., “Inactivation of DNA repair triggers neoantigen generation and impairs tumour growth,” Nature, vol. 552, no. 7683, pp. 116–120, Dec. 2017. [CrossRef]

- T. Macarulla Mercade et al., “331P Phase Ib/IIa study to evaluate safety and efficacy of priming treatment with the hedgehog inhibitor NLM-001 prior to gemcitabine and nab-paclitaxel plus zalifrelimab as first-line treatment in patients with advanced pancreatic cancer: NUMANTIA study,” Ann. Oncol., vol. 35, pp. S139–S140, Jun. 2024. [CrossRef]

- S. S. Karhadkar et al., “Hedgehog signalling in prostate regeneration, neoplasia and metastasis,” Nature, vol. 431, no. 7009, pp. 707–712, Oct. 2004. [CrossRef]

- G. Feldmann et al., “Blockade of Hedgehog Signaling Inhibits Pancreatic Cancer Invasion and Metastases: A New Paradigm for Combination Therapy in Solid Cancers,” Cancer Res., vol. 67, no. 5, pp. 2187–2196, Mar. 2007. [CrossRef]

- D. M. Berman et al., “Widespread requirement for Hedgehog ligand stimulation in growth of digestive tract tumours,” Nature, vol. 425, no. 6960, pp. 846–851, Oct. 2003. [CrossRef]

- S. V. Outram, A. Varas, C. V. Pepicelli, and T. Crompton, “Hedgehog Signaling Regulates Differentiation from Double-Negative to Double-Positive Thymocyte,” Immunity, vol. 13, no. 2, pp. 187–197, Aug. 2000. [CrossRef]

- S. L. Topalian et al., “Safety, Activity, and Immune Correlates of Anti–PD-1 Antibody in Cancer,” N. Engl. J. Med., vol. 366, no. 26, pp. 2443–2454, Jun. 2012. [CrossRef]

- A. Hoos et al., “Development of Ipilimumab: Contribution to a New Paradigm for Cancer Immunotherapy,” Semin. Oncol., vol. 37, no. 5, pp. 533–546, Oct. 2010. [CrossRef]

- F. S. Hodi et al., “Nivolumab plus ipilimumab or nivolumab alone versus ipilimumab alone in advanced melanoma (CheckMate 067): 4-year outcomes of a multicentre, randomised, phase 3 trial,” Lancet Oncol., vol. 19, no. 11, pp. 1480–1492, Nov. 2018. [CrossRef]

- H. A. Tawbi et al., “Combined Nivolumab and Ipilimumab in Melanoma Metastatic to the Brain,” N. Engl. J. Med., vol. 379, no. 8, pp. 722–730, Aug. 2018. [CrossRef]

- M. A. Postow et al., “Nivolumab and Ipilimumab versus Ipilimumab in Untreated Melanoma,” N. Engl. J. Med., vol. 372, no. 21, pp. 2006–2017, May 2015. [CrossRef]

- I. M. Chen et al., “Randomized Phase II Study of Nivolumab With or Without Ipilimumab Combined With Stereotactic Body Radiotherapy for Refractory Metastatic Pancreatic Cancer (CheckPAC),” J. Clin. Oncol., vol. 40, no. 27, pp. 3180–3189, Sep. 2022. [CrossRef]

- A. Valachis et al., “Improved survival without increased toxicity with influenza vaccination in cancer patients treated with checkpoint inhibitors,” OncoImmunology, vol. 10, no. 1, p. 1886725, Jan. 2021. [CrossRef]

- X. Wu, T. Li, R. Jiang, X. Yang, H. Guo, and R. Yang, “Targeting MHC-I molecules for cancer: function, mechanism, and therapeutic prospects,” Mol. Cancer, vol. 22, no. 1, p. 194, Dec. 2023. [CrossRef]

- H. Salmon et al., “Expansion and Activation of CD103+ Dendritic Cell Progenitors at the Tumor Site Enhances Tumor Responses to Therapeutic PD-L1 and BRAF Inhibition,” Immunity, vol. 44, no. 4, pp. 924–938, Apr. 2016. [CrossRef]

- A. R. Sánchez-Paulete et al., “Cancer Immunotherapy with Immunomodulatory Anti-CD137 and Anti–PD-1 Monoclonal Antibodies Requires BATF3-Dependent Dendritic Cells,” Cancer Discov., vol. 6, no. 1, pp. 71–79, Jan. 2016. [CrossRef]

- S. Khubchandani, M. S. Czuczman, and F. J. Hernandez-Ilizaliturri, “Dacetuzumab, a humanized mAb against CD40 for the treatment of hematological malignancies,” Curr. Opin. Investig. Drugs Lond. Engl. 2000, vol. 10, no. 6, pp. 579–587, Jun. 2009.

- P. W. Johnson et al., “A Cancer Research UK phase I study evaluating safety, tolerability, and biological effects of chimeric anti-CD40 monoclonal antibody (MAb), Chi Lob 7/4.,” J. Clin. Oncol., vol. 28, no. 15_suppl, pp. 2507–2507, May 2010. [CrossRef]

- H. J. McKenna, “Role of hematopoietic growth factors/flt3 ligand in expansion and regulation of dendritic cells:,” Curr. Opin. Hematol., vol. 8, no. 3, pp. 149–154, May 2001. [CrossRef]

- K. T. Byrne and R. H. Vonderheide, “CD40 Stimulation Obviates Innate Sensors and Drives T Cell Immunity in Cancer,” Cell Rep., vol. 15, no. 12, pp. 2719–2732, Jun. 2016. [CrossRef]

- L. Miao, Y. Zhang, and L. Huang, “mRNA vaccine for cancer immunotherapy,” Mol. Cancer, vol. 20, no. 1, p. 41, Dec. 2021. [CrossRef]

- M. Saxena, S. H. Van Der Burg, C. J. M. Melief, and N. Bhardwaj, “Therapeutic cancer vaccines,” Nat. Rev. Cancer, vol. 21, no. 6, pp. 360–378, Jun. 2021. [CrossRef]

- D. Fioretti, S. Iurescia, V. M. Fazio, and M. Rinaldi, “DNA Vaccines: Developing New Strategies against Cancer,” J. Biomed. Biotechnol., vol. 2010, pp. 1–16, 2010. [CrossRef]

- W. Liu, H. Tang, L. Li, X. Wang, Z. Yu, and J. Li, “Peptide-based therapeutic cancer vaccine: Current trends in clinical application,” Cell Prolif., vol. 54, no. 5, p. e13025, May 2021. [CrossRef]

- Y. Yuan, F. Gao, Y. Chang, Q. Zhao, and X. He, “Advances of mRNA vaccine in tumor: a maze of opportunities and challenges,” Biomark. Res., vol. 11, no. 1, p. 6, Jan. 2023. [CrossRef]

- Z. Wijfjes, F. J. Van Dalen, C. M. Le Gall, and M. Verdoes, “Controlling Antigen Fate in Therapeutic Cancer Vaccines by Targeting Dendritic Cell Receptors,” Mol. Pharm., vol. 20, no. 10, pp. 4826–4847, Oct. 2023. [CrossRef]

- U. Sahin et al., “An RNA vaccine drives immunity in checkpoint-inhibitor-treated melanoma,” Nature, vol. 585, no. 7823, pp. 107–112, Sep. 2020. [CrossRef]

- S. S. Rosa, D. M. F. Prazeres, A. M. Azevedo, and M. P. C. Marques, “mRNA vaccines manufacturing: Challenges and bottlenecks,” Vaccine, vol. 39, no. 16, pp. 2190–2200, Apr. 2021. [CrossRef]

- X. Huang, G. Zhang, T.-Y. Tang, X. Gao, and T.-B. Liang, “Personalized pancreatic cancer therapy: from the perspective of mRNA vaccine,” Mil. Med. Res., vol. 9, no. 1, p. 53, Oct. 2022. [CrossRef]

- Y. L. Vishweshwaraiah and N. V. Dokholyan, “mRNA vaccines for cancer immunotherapy,” Front. Immunol., vol. 13, p. 1029069, Dec. 2022. [CrossRef]

- T. Uehata and O. Takeuchi, “RNA Recognition and Immunity—Innate Immune Sensing and Its Posttranscriptional Regulation Mechanisms,” Cells, vol. 9, no. 7, p. 1701, Jul. 2020. [CrossRef]

- L. A. Rojas et al., “Personalized RNA neoantigen vaccines stimulate T cells in pancreatic cancer,” Nature, vol. 618, no. 7963, pp. 144–150, Jun. 2023. [CrossRef]

- A. Wadhwa, A. Aljabbari, A. Lokras, C. Foged, and A. Thakur, “Opportunities and Challenges in the Delivery of mRNA-Based Vaccines,” Pharmaceutics, vol. 12, no. 2, p. 102, Jan. 2020. [CrossRef]

- U. Sahin, K. Karikó, and Ö. Türeci, “mRNA-based therapeutics — developing a new class of drugs,” Nat. Rev. Drug Discov., vol. 13, no. 10, pp. 759–780, Oct. 2014. [CrossRef]

- M. Diken et al., “Selective uptake of naked vaccine RNA by dendritic cells is driven by macropinocytosis and abrogated upon DC maturation,” Gene Ther., vol. 18, no. 7, pp. 702–708, Jul. 2011. [CrossRef]

- H. Kato and T. Fujita, “RIG-I-like receptors and autoimmune diseases,” Curr. Opin. Immunol., vol. 37, pp. 40–45, Dec. 2015. [CrossRef]

- A.-K. Minnaert et al., “Strategies for controlling the innate immune activity of conventional and self-amplifying mRNA therapeutics: Getting the message across,” Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev., vol. 176, p. 113900, Sep. 2021. [CrossRef]

- H.-G. Hu and Y.-M. Li, “Emerging Adjuvants for Cancer Immunotherapy,” Front. Chem., vol. 8, p. 601, Jul. 2020. [CrossRef]

- S. Van Lint et al., “Preclinical Evaluation of TriMix and Antigen mRNA-Based Antitumor Therapy,” Cancer Res., vol. 72, no. 7, pp. 1661–1671, Apr. 2012. [CrossRef]

- M. H. Andersen, “Novel immune modulatory vaccines targeting TGFβ,” Cell. Mol. Immunol., vol. 20, no. 5, pp. 551–553, Mar. 2023. [CrossRef]

- H. Sugiyama, “Wilms’ Tumor GeneWT1: Its Oncogenic Function and Clinical Application,” Int. J. Hematol., vol. 73, no. 2, pp. 177–187, Feb. 2001. [CrossRef]

- Y. Oji et al., “Overexpression of the Wilms’ tumor gene WT1 in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma,” Cancer Sci., vol. 95, no. 7, pp. 583–587, Jul. 2004. [CrossRef]

- M. Shourian, J.-C. Beltra, B. Bourdin, and H. Decaluwe, “Common gamma chain cytokines and CD8 T cells in cancer,” Semin. Immunol., vol. 42, p. 101307, Apr. 2019. [CrossRef]

- J. Leonard, J.-X. Lin, and J. J. O’Shea, “The γc Family of Cytokines: Basic Biology to Therapeutic Ramifications,” Immunity, vol. 50, no. 4, pp. 832–850, Apr. 2019. [CrossRef]

- E. Belnoue et al., “Targeting self- and neoepitopes with a modular self-adjuvanting cancer vaccine,” JCI Insight, vol. 4, no. 11, p. e127305, Jun. 2019. [CrossRef]

- D. T. Le et al., “Evaluation of Ipilimumab in Combination With Allogeneic Pancreatic Tumor Cells Transfected With a GM-CSF Gene in Previously Treated Pancreatic Cancer,” J. Immunother., vol. 36, no. 7, pp. 382–389, Sep. 2013. [CrossRef]

- E. J. Lipson et al., “Safety and immunologic correlates of Melanoma GVAX, a GM-CSF secreting allogeneic melanoma cell vaccine administered in the adjuvant setting,” J. Transl. Med., vol. 13, no. 1, p. 214, Dec. 2015. [CrossRef]

- D. Laheru et al., “Allogeneic Granulocyte Macrophage Colony-Stimulating Factor–Secreting Tumor Immunotherapy Alone or in Sequence with Cyclophosphamide for Metastatic Pancreatic Cancer: A Pilot Study of Safety, Feasibility, and Immune Activation,” Clin. Cancer Res., vol. 14, no. 5, pp. 1455–1463, Mar. 2008. [CrossRef]

- D. T. Le et al., “Safety and Survival With GVAX Pancreas Prime and Listeria Monocytogenes –Expressing Mesothelin (CRS-207) Boost Vaccines for Metastatic Pancreatic Cancer,” J. Clin. Oncol., vol. 33, no. 12, pp. 1325–1333, Apr. 2015. [CrossRef]

- D. T. Le et al., “A Live-Attenuated Listeria Vaccine (ANZ-100) and a Live-Attenuated Listeria Vaccine Expressing Mesothelin (CRS-207) for Advanced Cancers: Phase I Studies of Safety and Immune Induction,” Clin. Cancer Res., vol. 18, no. 3, pp. 858–868, Feb. 2012. [CrossRef]

- Z. Chen et al., “A Neoantigen-Based Peptide Vaccine for Patients With Advanced Pancreatic Cancer Refractory to Standard Treatment,” Front. Immunol., vol. 12, p. 691605, Aug. 2021. [CrossRef]

- C. J. M. Melief and S. H. Van Der Burg, “Immunotherapy of established (pre)malignant disease by synthetic long peptide vaccines,” Nat. Rev. Cancer, vol. 8, no. 5, pp. 351–360, May 2008. [CrossRef]

- S. Pant et al., “First-in-human phase 1 trial of ELI-002 immunotherapy as treatment for subjects with Kirsten rat sarcoma (KRAS)-mutated pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma and other solid tumors.,” J. Clin. Oncol., vol. 40, no. 16_suppl, pp. TPS2701–TPS2701, Jun. 2022. [CrossRef]

- D. Cullinan et al., “Preliminary Results Of A Phase Ib Clinical Trial Of A Neoantigen Dna Vaccine For Pancreatic Cancer,” HPB, vol. 22, pp. S12–S13, 2020. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).