Submitted:

05 August 2024

Posted:

05 August 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.1.1. Online Semi-Structured Interviews

2.1.2. Co-Design Workshops

2.2. Participants

- blind or partially sighted people

- above 18 years old

- have an interest in leisure travel and tourism

- no other disability that may impact their ability to travel

2.3. Data Analysis

3. Results

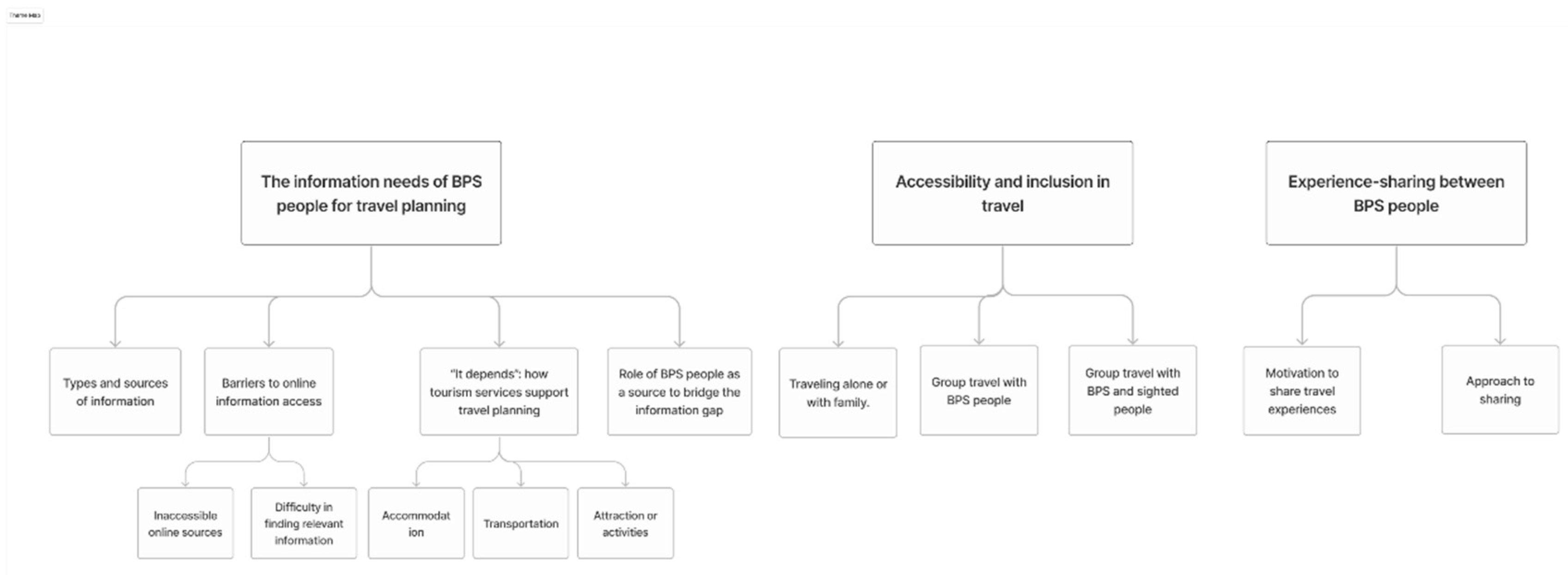

3.1. The Information Needs of BPS People for Travel Planning

3.1.1. Types and Sources of Information

3.1.2. Barriers to Online Information Access.

3.1.3. Inaccessible Online Sources

3.1.4. Difficulty in Finding Relevant Information

3.1.5. “It Depends”: How Tourism Services Support Travel Planning

3.1.6. Accommodation

3.1.7. Transportation

3.1.8. Attractions and Activities

3.1.9. Role of BPS People as a Source to Bridge the Information Gap

3.2. Accessibility and inclusion in travel

3.2.1. Traveling Alone or with Family

3.2.2. Group Travel with BPS People

3.2.3. Group Travel with BPS and Sighted People

3.3. Experience-Sharing between BPS People

3.3.1. Motivation to Share Travel Experiences

3.3.2. Approach to Sharing

4. Discussion

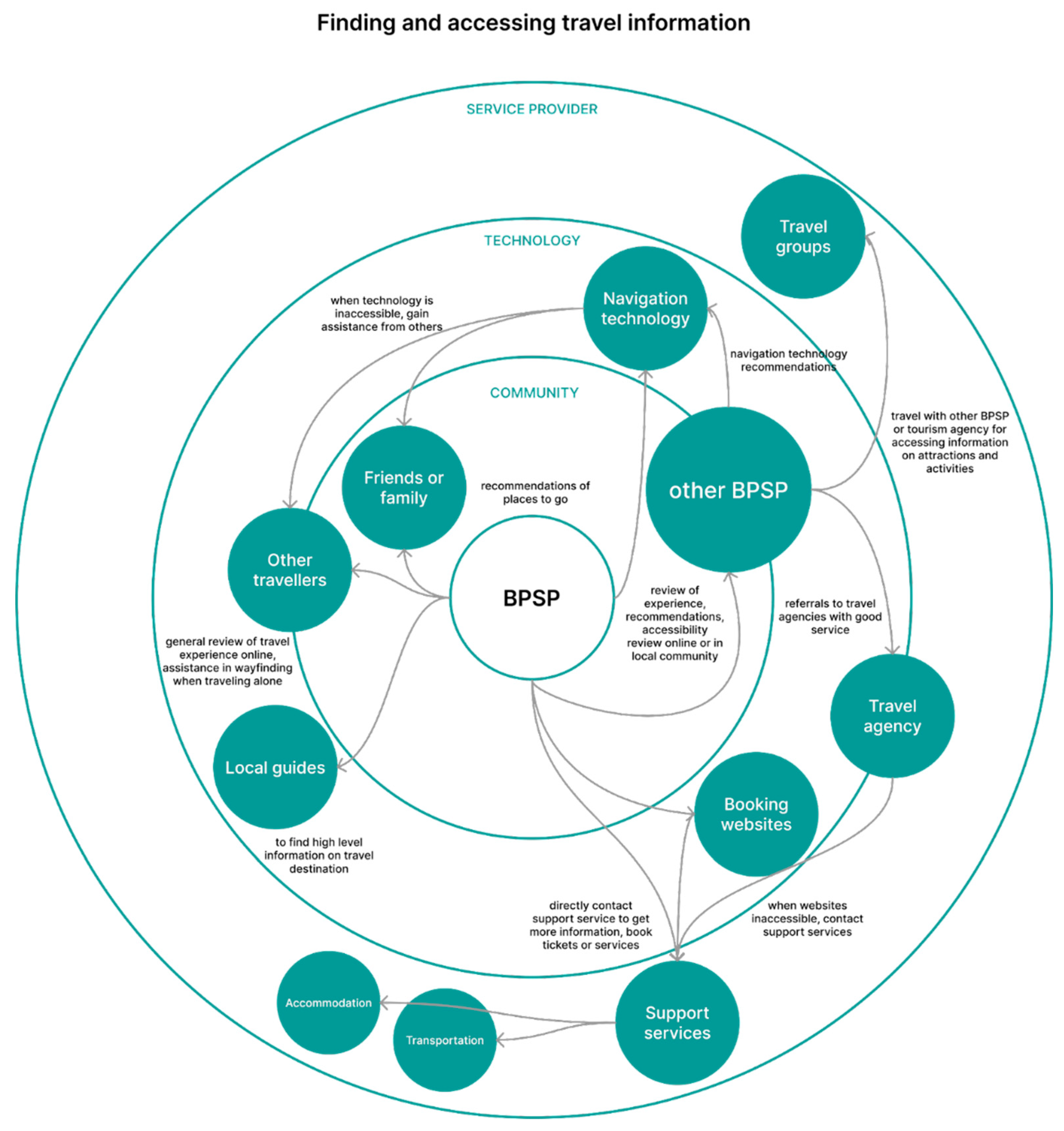

4.1. Mapping the Accessible Tourism Ecosystem

4.1.1. Community

4.1.2. Technology

4.2. Service Providers

4.2.1. Information-Seeking in and for Travel

4.3. Interdependence and Experience-Sharing in Travel

4.4. Designing Technology for Accessible Travel

4.5. Limitations & Future Work

5. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Gaurav Agrawal, Ankur Dumka, Mayank Singh, and Anchit Bijalwan. 2022. Assessing Usability and Accessibility of Indian Tourism Websites for Visually Impaired. Journal of Sensors 2022 (May 2022), e4433013. [CrossRef]

- Zehra Altinay, Tulen Saner, Nesrin M. Bahçelerli, and Fahriye Altinay. 2016. The Role of Social Media Tools: Accessible Tourism for Disabled Citizens. Journal of Educational Technology & Society 19, 1 (2016), 89–99. http://www.jstor.org/stable/jeductechsoci.19.1.89.

- Maryam Bandukda, Catherine Holloway, Aneesha Singh, and Nadia Berthouze. 2020. PLACES: A Framework for Supporting Blind and Partially.

- Sighted People in Outdoor Leisure Activities. In Proceedings of the 22nd International ACM SIGACCESS Conference on Computers and Accessibility (ASSETS ’20). Association for Computing Machinery, New York, NY, USA, 1–13. [CrossRef]

- Maryam Bandukda, Aneesha Singh, Nadia Berthouze, and Catherine Holloway. 2019. Understanding Experiences of Blind Individuals in Outdoor.

- Nature. In Extended Abstracts of the 2019 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems (Glasgow, Scotland Uk) (CHI EA ’19). Association for Computing Machinery, New York, NY, USA, 1–6. [CrossRef]

- Nikola Banovic, Rachel L. Franz, Khai N. Truong, Jennifer Mankoff, and Anind K. Dey. 2013. Uncovering information needs for independent spatial.

- learning for users who are visually impaired. In Proceedings of the 15th International ACM SIGACCESS Conference on Computers and Accessibility (ASSETS ’13). Association for Computing Machinery, New York, NY, USA, 1–8. [CrossRef]

- Natã M. Barbosa, Jordan Hayes, Smirity Kaushik, and Yang Wang. 2022. “Every Website Is a Puzzle!”: Facilitating Access to Common Website Features for People with Visual Impairments. ACM Trans. Access. Comput. 15, 3, Article 19 (jul 2022), 35 pages. [CrossRef]

- Cynthia L. Bennett, Erin Brady, and Stacy M. Branham. 2018. Interdependence as a Frame for Assistive Technology Research and Design.

- In Proceedings of the 20th International ACM SIGACCESS Conference on Computers and Accessibility. ACM, Galway Ireland, 161–173. [CrossRef]

- Bodil Stilling Blichfeldt and Jaqueline Nicolaisen. 2011. Disabled travel: not easy, but doable. Current Issues in Tourism 14, 1 (Jan. 2011), 79–102. [CrossRef]

- Nicholas Bradley and Mark Dunlop. 2005. An Experimental Investigation into Wayfinding Directions for Visually Impaired People. Personal and Ubiquitous Computing 9 (11 2005), 395–403. [CrossRef]

- Virginia Braun and Victoria Clarke. 2021. One size fits all? What counts as quality practice in (reflexive) thematic analysis? Qualitative Research in Psychology 18, 3 (2021), 328–352. [CrossRef]

- D. Buhalis and S. Darcy. 2010. Accessible Tourism: Concepts and Issues. Channel View Publications. https://books.google.co.uk/books?id=BSeyjdevpwC.

- Chun-Chu Chen and James Petrick. 2013. Health and Wellness Benefits of Travel Experiences A Literature Review. Journal of Travel Research 52 (Nov. 2013), 709–719. [CrossRef]

- Rick Crandall. 1980. Motivations for Leisure. Journal of Leisure Research 12, 1 (Jan. 1980), 45–54. [CrossRef]

- John L. Crompton. 1979. Motivations for pleasure vacation. Annals of Tourism Research 6, 4 (Oct. 1979), 408–424.

- Damiasih Damiasih, Andrea Basworo Palestho, Anak Agung Gede Raka, Hari Kurniawan, Putri Pebriani, Suhendroyono Suhendroyono, Anak.

- Agung Gede Raka Gunawarman, and Putradji Maulidimas. 2022. Comprehensive Analysis of Accessible Tourism and Its Case Study in Indonesia.

- Journal of Environmental Management and Tourism 13, 4 (July 2022), 995–1015. https://journals.aserspublishing.eu/jemt/article/view/7056 Number: 4 Publisher: ASERS Publishing.

- Margaret J. Daniels, Ellen B. Drogin Rodgers, and Brenda P. Wiggins. 2005. “Travel Tales”: an interpretive analysis of constraints and negotiations to pleasure travel as experienced by persons with physical disabilities. Tourism Management 26, 6 (Dec. 2005), 919–930. [CrossRef]

- Simon Darcy. 2003. Disabling Journeys: The tourism patterns of people with impairments in Australia. In CAUTHE 2003: Riding the Wave of Tourism and Hospitality Research. Southern Cross University, Lismore, N.S.W., 271–279.

- Simon Darcy and Tracey Dickson. 2009. A Whole-of-Life Approach to Tourism: The Case for Accessible Tourism Experiences. Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Management 16 (Dec. 2009), 32–44. [CrossRef]

- Eugenia Devile and Elisabeth Kastenholz. 2018. Accessible tourism experiences: the voice of people with visual disabilities. Journal of Policy Research in Tourism, Leisure and Events 10, 3 (Sept. 2018), 265–285. [CrossRef]

- Trinidad Domínguez Vila, Elisa Alén González, and Simon Darcy. 2020. Accessibility of tourism websites: the level of countries’ commitment. Univers. Access Inf. Soc. 19, 2 (jun 2020), 331–346. [CrossRef]

- Christin Engel, Karin Müller, Angela Constantinescu, Claudia Loitsch, Vanessa Petrausch, Gerhard Weber, and Rainer Stiefelhagen. 2020. Travelling more independently: A Requirements Analysis for Accessible Journeys to Unknown Buildings for People with Visual Impairments. In Proceedings of.

- the 22nd International ACM SIGACCESS Conference on Computers and Accessibility (ASSETS ’20). Association for Computing Machinery, New York, NY, USA, 1–11. [CrossRef]

- Arlin Epperson. 1983. Why People Travel. Journal of Physical Education, Recreation & Dance 54, 4 (April 1983), 53–55. [CrossRef]

- Celeste Eusébio, André Silveiro, and Leonor Teixeira. 2020. Website accessibility of travel agents: An evaluation using web diagnostic tools. Journal of Accessibility and Design for All 10, 2 (Nov. 2020), 180–208. [CrossRef]

- John H. Falk, Roy Ballantyne, Jan Packer, and Pierre Benckendorff. 2012. Travel and Learning: A Neglected Tourism Research Area. Annals of Tourism Research 39, 2 (April 2012), 908–927. [CrossRef]

- Cole Gleason, Patrick Carrington, Lydia B. Chilton, Benjamin M. Gorman, Hernisa Kacorri, Andrés Monroy-Hernández, Meredith Ringel Morris, Garreth W. Tigwell, and Shaomei Wu. 2019. Addressing the Accessibility of Social Media. In Companion Publication of the 2019 Conference on Computer Supported Cooperative Work and Social Computing (Austin, TX, USA) (CSCW ’19 Companion). Association for Computing Machinery, New York, NY, USA, 474–479. [CrossRef]

- Carole Goble, Simon Harper, and Robert Stevens. 2000. The travails of visually impaired web travellers. In Proceedings of the eleventh ACM on Hypertext and hypermedia. ACM, San Antonio Texas USA, 1–10. [CrossRef]

- Maksim Godovykh and Asli D. A. Tasci. 2020. Customer experience in tourism: A review of definitions, components, and measurements. Tourism Management Perspectives 35 (July 2020), 100694. [CrossRef]

- Maria José Angélico Gonçalves, Ana Paula Camarinha, António José Abreu, Sandrina Teixeira, and Amélia Ferreira da Silva. 2020. Web Accessibility in the Tourism Sector: An Analysis of the Most Used Websites in Portugal. In Advances in Tourism, Technology and Smart Systems (Smart Innovation, Systems and Technologies), Álvaro Rocha, António Abreu, João Vidal de Carvalho, Dália Liberato, Elisa Alén González, and Pedro Liberato (Eds.). Springer, Singapore, 141–150. [CrossRef]

- Jee-Hee Han and Juline Mills. 2007. Are Travel Websites Meeting the Needs of the Visually Impaired? J. of IT & Tourism 9 (06 2007), 99–113. [CrossRef]

- Maximiliano Jeanneret Medina, Denis Lalanne, Baudet Cédric, and Cédric Benoit. 2022. ”It Deserves to Be Further Developed”: A Study of Mainstream Web Interface Adaptability for People with Low Vision. In Extended Abstracts of the 2022 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems (New Orleans, LA, USA) (CHI EA ’22). Association for Computing Machinery, New York, NY, USA, Article 261, 7 pages. [CrossRef]

- Vaishnav Kameswaran, Alexander J. Fiannaca, Melanie Kneisel, Amy Karlson, Edward Cutrell, and Meredith Ringel Morris. 2020. Understanding.

- In-Situ Use of Commonly Available Navigation Technologies by People with Visual Impairments. In Proceedings of the 22nd International ACM.

- SIGACCESS Conference on Computers and Accessibility (, Virtual Event, Greece,) (ASSETS ’20). Association for Computing Machinery, New York, NY, USA, Article 28, 12 pages. [CrossRef]

- Kak-Yom Kim and Giri Jogaratnam. 2003. Travel Motivations. Journal of Travel & Tourism Marketing 13, 4 (April 2003), 61–82.

- Anna Kołodziejczak. 2019. Information as a Factor of the Development of Accessible Tourism for People with Disabilities. Quaestiones Geographicae 38, 2 (June 2019), 67–73. [CrossRef]

- Kit Ling Lam, Chung-Shing Chan, and Mike Peters. 2020. Understanding technological contributions to accessible tourism from the perspective of destination design for visually impaired visitors in Hong Kong. Journal of Destination Marketing & Management 17 (Sept. 2020), 100434. [CrossRef]

- Sooyeon Lee, Madison Reddie, and John M. Carroll. 2021. Designing for Independence for People with Visual Impairments. Proceedings of the ACM on Human-Computer Interaction 5, CSCW1 (April 2021), 149:1–149:19. [CrossRef]

- Alan A. Lew. 2018. Why travel? – travel, tourism, and global consciousness. Tourism Geographies 20, 4 (Aug. 2018), 742–749. [CrossRef]

- Yi Luo, Chiang Lanlung (Luke), Eojina Kim, Liang Rebecca Tang, and Sung Mi Song. 2018. Towards quality of life: the effects of the wellness tourism experience. Journal of Travel & Tourism Marketing 35, 4 (May 2018), 410–424. [CrossRef]

- Bob McKercher and Simon Darcy. 2018. Re-conceptualizing barriers to travel by people with disabilities. Tourism Management Perspectives 26 (April 2018), 59–66. [CrossRef]

- Vinayaraj Mothiravally, Siosen Ang, Gul Muhammad Baloch, Toney Thomas Kulampallil, and Smitha Geetha. 2014. Attitude and Perception of Visually Impaired Travelers: A Case of Klang Valley, Malaysia. Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences 144 (Aug. 2014), 366–377. [CrossRef]

- Andreia Moura, Celeste Eusébio, and Eugénia Devile. 2023. The ‘why’ and ‘what for’ of participation in tourism activities: travel motivations of people with disabilities. Current Issues in Tourism 26, 6 (March 2023), 941–957. [CrossRef]

- Karin Müller, Christin Engel, Claudia Loitsch, Rainer Stiefelhagen, and Gerhard Weber. 2022. Traveling More Independently: A Study on the.

- Diverse Needs and Challenges of People with Visual or Mobility Impairments in Unfamiliar Indoor Environments. ACM Transactions on Accessible Computing 15, 2 (May 2022), 13:1–13:44. [CrossRef]

- Tanya Packer, Jennie Small, and Simon Darcy. 2007. Tourist Experiences of Individuals with Vision Impairment. (01 2007), 18–21.

- Tanya L. Packer, Tanya L. Packer, Bob Mckercher, and Matthew K. Yau. 2007. Understanding the complex interplay between tourism, disability and environmental contexts. Disability and Rehabilitation 29, 4 (Jan. 2007), 281–292. [CrossRef]

- Dorian Peters. 2023. Wellbeing Supportive Design – Research-Based Guidelines for Supporting Psychological Wellbeing in User Experience. International Journal of Human–Computer Interaction 39, 14 (2023), 2965–2977. [CrossRef]

- Christopher Power, André Freire, Helen Petrie, and David Swallow. 2012. Guidelines are only half of the story: accessibility problems encountered by.

- blind users on the web. In Proceedings of the SIGCHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems (Austin, Texas, USA) (CHI ’12). Association for Computing Machinery, New York, NY, USA, 433–442. [CrossRef]

- Guanghui Qiao, Yating Cao, and Junmiao Zhang. 2022. Accessible Tourism – understanding blind and vision-impaired tourists’ behaviour towards inclusion. Tourism Review 78, 2 (Jan. 2022), 531–560. [CrossRef]

- Guanghui Qiao, Anja Pabel, and Nan Chen. 2021. Understanding the Factors Influencing the Leisure Tourism Behavior of Visually Impaired Travelers: An Empirical Study in China. Frontiers in Psychology 12 (06 2021). [CrossRef]

- Guanghui Qiao, Hanqi Song, Bruce Prideaux, and Songshan (Sam) Huang. 2023. The “unseen” tourism: Travel experience of people with visual impairment. Annals of Tourism Research 99 (March 2023), 103542. [CrossRef]

- Carolina Sacramento and Simone Bacellar Leal Ferreira. 2022. Accessibility on social media: exploring congenital blind people’s interaction with.

- visual content. In Proceedings of the 21st Brazilian Symposium on Human Factors in Computing Systems (Diamantina, Brazil) (IHC ’22). Association for Computing Machinery, New York, NY, USA, Article 35, 7 pages. [CrossRef]

- Jennie Small. 2015. Interconnecting mobilities on tour: tourists with vision impairment partnered with sighted tourists. Tourism Geographies 17, 1 (2015), 76–90. [CrossRef]

- Jennie Small and Simon Darcy. 2010. Chapter 5. Understanding Tourist Experience Through Embodiment: The Contribution of Critical Tourism and Disability Studies. In Accessible Tourism. 73–97. [CrossRef]

- Jennie Small, Simon Darcy, and Tanya Packer. 2012. The embodied tourist experiences of people with vision impairment: Management implications beyond the visual gaze. Tourism Management 33, 4 (Aug. 2012), 941–950. [CrossRef]

- Anjana Srikrishnan and Anirudha Joshi. 2019. Comparison of verbalized navigation by visually impaired users with navigation based on instructions.

- from Google maps. In Proceedings of the 10th Indian Conference on Human-Computer Interaction (IndiaHCI ’19). Association for Computing Machinery, New York, NY, USA, 1–6. [CrossRef]

- Kate Stephens, Matthew Butler, Leona M Holloway, Cagatay Goncu, and Kim Marriott. 2020. Smooth Sailing? Autoethnography of Recreational.

- Travel by a Blind Person. In Proceedings of the 22nd International ACM SIGACCESS Conference on Computers and Accessibility (ASSETS ’20). Association for Computing Machinery, New York, NY, USA, 1–12. [CrossRef]

- Kate Stephens, Matthew Butler, Leona M Holloway, Cagatay Goncu, and Kim Marriott. 2020. Smooth Sailing? Autoethnography of Recreational Travel.

- by a Blind Person. In Proceedings of the 22nd International ACM SIGACCESS Conference on Computers and Accessibility (<conf-loc>, <city>Virtual Event</city>, <country>Greece</country>, </conf-loc>) (ASSETS ’20). Association for Computing Machinery, New York, NY, USA, Article 26, 12 pages. [CrossRef]

- Erose Sthapit, Peter Björk, and Dafnis N. Coudounaris. 2023. Towards a better understanding of memorable wellness tourism experience. International Journal of Spa and Wellness 6, 1 (Jan. 2023), 1–27. [CrossRef]

- Sarah J. Swierenga, Jieun Sung, Graham L. Pierce, and Dennis B. Propst. 2011. Website Design and Usability Assessment Implications from a Usability Study with Visually Impaired Users. In Universal Access in Human-Computer Interaction. Users Diversity, Constantine Stephanidis (Ed.). Springer Berlin Heidelberg, Berlin, Heidelberg, 382–389.

- Pedro Teixeira, Joana Alves, Tiago Correia, Leonor Teixeira, Celeste Eusébio, Samuel Silva, and António Teixeira. 2021. A Multidisciplinary User-Centered Approach to Designing an Information Platform for Accessible Tourism: Understanding User Needs and Motivations. In Universal.

- Access in Human-Computer Interaction. Design Methods and User Experience (Lecture Notes in Computer Science), Margherita Antona and Constantine.

- Stephanidis (Eds.). Springer International Publishing, Cham, 136–150.

- Anja Thieme, Cynthia L. Bennett, Cecily Morrison, Edward Cutrell, and Alex S. Taylor. 2018. “I can do everything but see!” – How People with Vision Impairments Negotiate their Abilities in Social Contexts. In Proceedings of the 2018 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems.

- (<conf-loc>, <city>Montreal QC</city>, <country>Canada</country>, </conf-loc>) (CHI ’18). Association for Computing Machinery, New York, NY, USA, 1–14. [CrossRef]

- Nick Watson, Alan Roulstone, and Carol Thomas. 2019. Routledge Handbook of Disability Studies. Routledge, London. Google-Books-ID: eB24DwAAQBAJ.

- Michele A. Williams, Caroline Galbraith, Shaun K. Kane, and Amy Hurst. 2014. “just let the cane hit it”: how the blind and sighted see navigation differently. In Proceedings of the 16th international ACM SIGACCESS conference on Computers & accessibility (ASSETS ’14). Association for Computing Machinery, New York, NY, USA, 217–224. [CrossRef]

- Jacob O. Wobbrock, Krzysztof Z. Gajos, Shaun K. Kane, and Gregg C. Vanderheiden. 2018. Ability-based design. Commun. ACM 61, 6 (may 2018), 62–71. [CrossRef]

- Matthew Kwai-sang Yau, Bob McKercher, and Tanya L. Packer. 2004. Traveling with a disability. Annals of Tourism Research 31, 4 (Oct. 2004), 946–960.

| Study | Semi-structured interviews | Workshop 1 | Workshop 2 | |||||||||||

| Participants | P1 | P2 | P3 | P4 | P5 | P6 | P7 | P8 | P9 | P10 | P11 | P12 | ||

| Trip logistics | ||||||||||||||

| Location | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | |||||||

| Cost | x | x | x | |||||||||||

| Method of travel | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | ||||||

| Preparation | ||||||||||||||

| Accommodation | x | x | x | x | ||||||||||

| Activities | x | x | x | x | x | |||||||||

| Booking transportation | x | x | x | x | x | x | ||||||||

| Navigation route | x | x | x | x | x | |||||||||

| Support services | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | ||||||

| Other people | ||||||||||||||

| Experiences | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | |||||||

| Accessibility review | x | x | x | x | x | |||||||||

| Recommendation | x | x | x | |||||||||||

| Stages | Semi-structured interview | Workshop 1 | Workshop 2 | |||||||||

| Participants | P1 | P2 | P3 | P4 | P5 | P6 | P7 | P8 | P9 | P10 | P11 | P12 |

| Online sources | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | |||

| Friends & family | x | x | x | x | x | x | ||||||

| Travel services | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | |||||

| Travel group | x | x | ||||||||||

| Other BPS people | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | ||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).