Submitted:

05 August 2024

Posted:

06 August 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

Financial Innovation and Stability

Technological Innovation and Sustainable Development

Market Dynamics and Competitive Advantage

3. Data

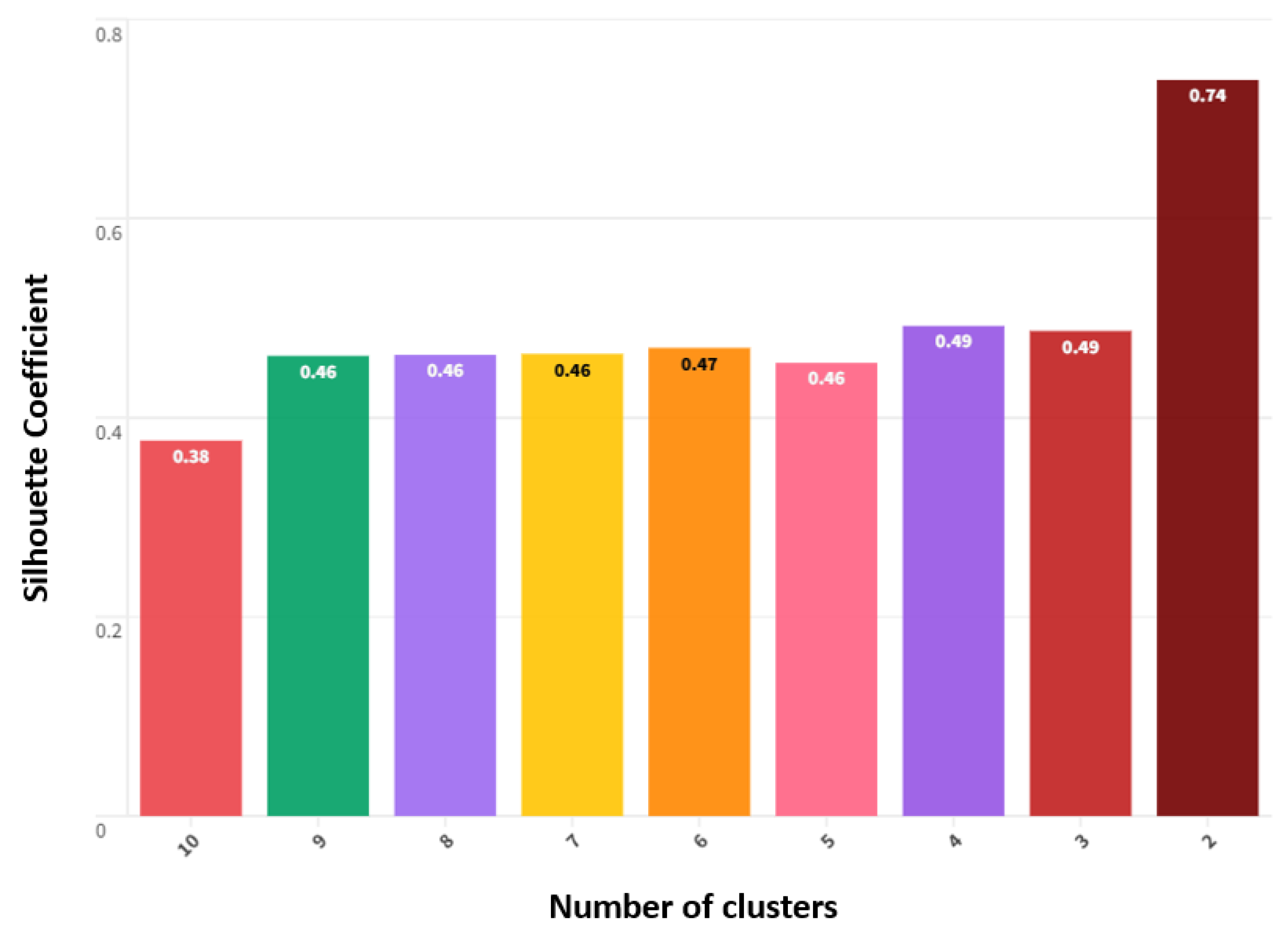

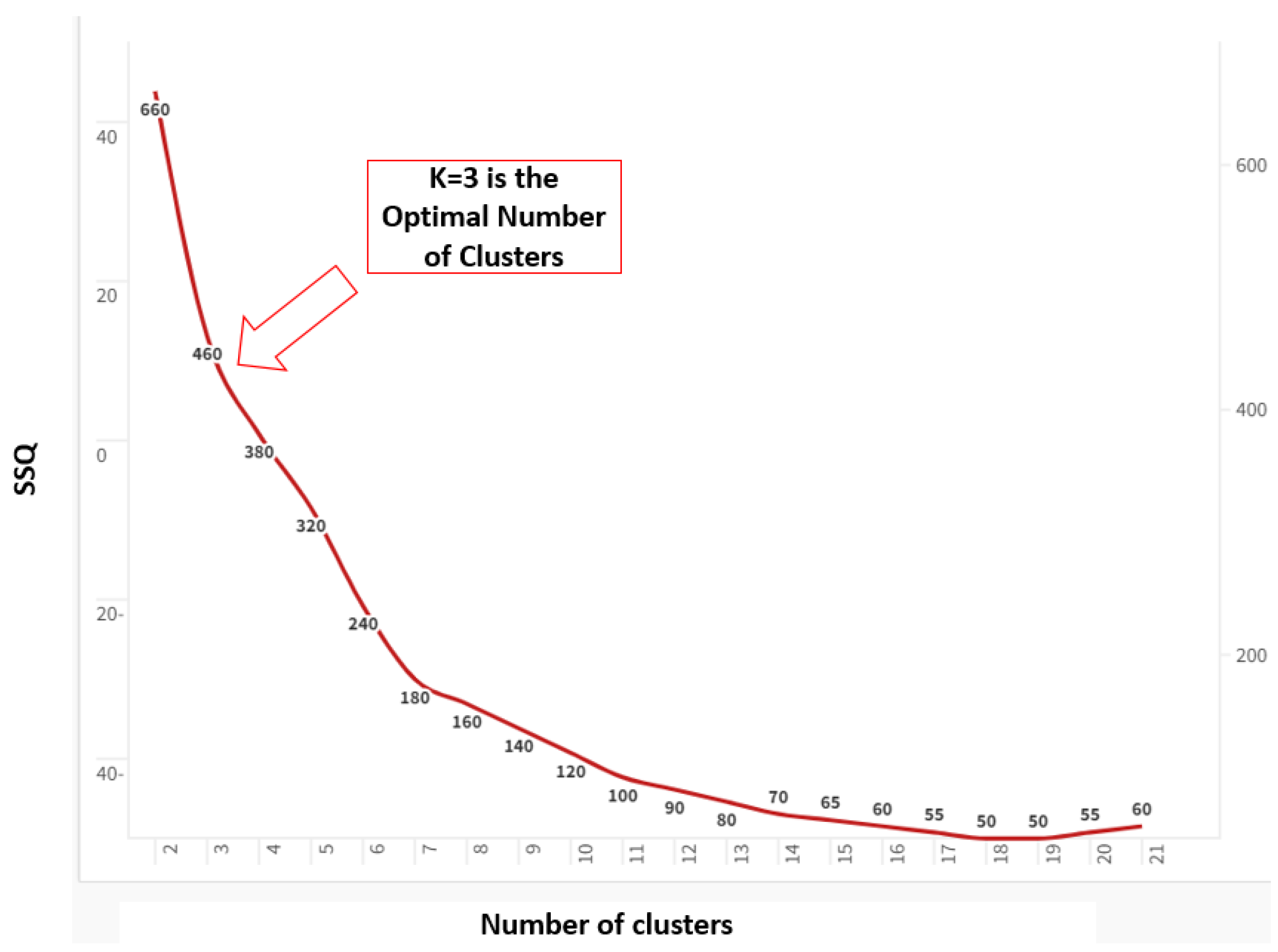

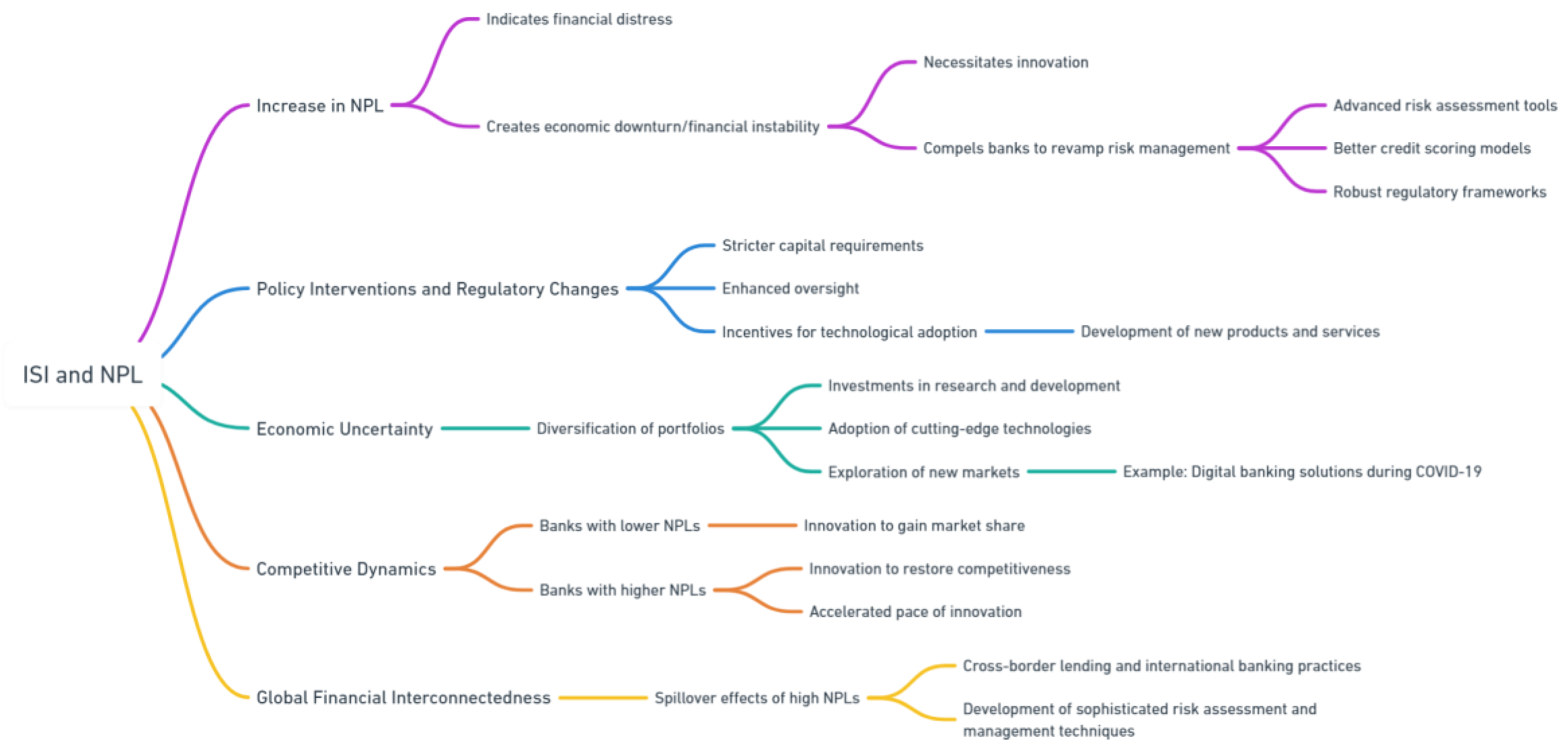

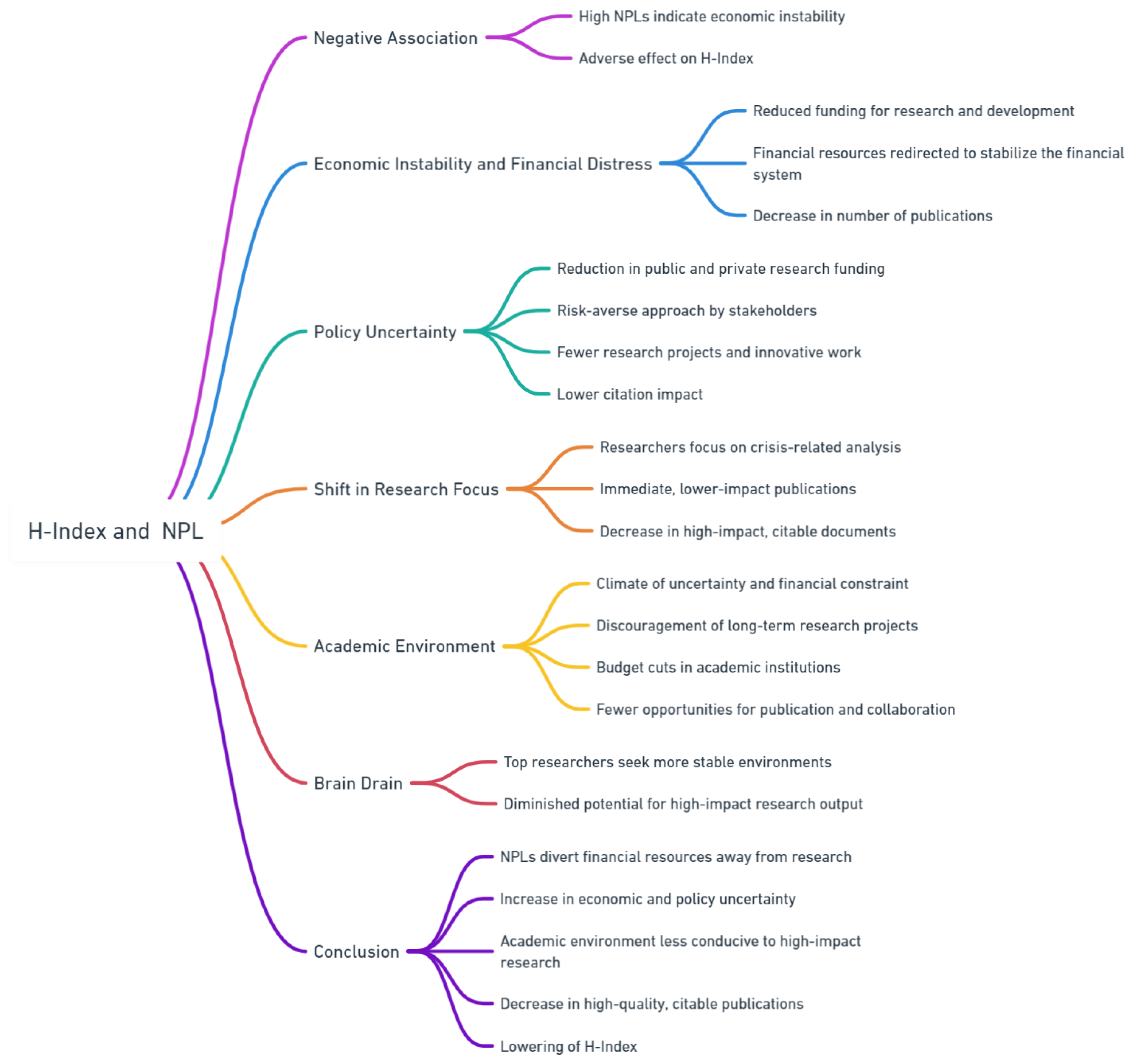

4. Clusterization with k-Means algorithms

5. Policy Implications

6. Conclusions

Appendix

- C1= Afghanistan, Albania, Algeria, Angola, Antigua and Barbuda, Argentina, Armenia, Australia, Austria, Bangladesh, Barbados, Belarus, Belgium, Bhutan, Bolivia, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Botswana, Brazil, Brunei Darussalam, Bulgaria, Cambodia, Cameroon, Canada, Chile, China, Colombia, Congo Dem. Rep., Congo Rep., Costa Rica, Croatia, Curacao, Czechia, Denmark, Djibouti, Dominica, Dominican Republic, Ecuador, El Salvador, Estonia, Eswatini, Ethiopia, Fiji, Finland, France, Gabon, Gambia, Georgia, Germany, Ghana, Grenada, Guatemala, Guinea, Honduras, Hong Kong SAR, Hungary, Iceland, India, Indonesia, Iraq, Ireland, Israel, Italy, Jordan, Kazakhstan, Kenya, Korea Rep., Kosovo, Kuwait, Kyrgyz Republic, Latvia, Lebanon, Lesotho, Lithuania, Luxembourg, Macao SAR, China, Madagascar, Malawi, Malaysia, Maldives, Malta, Mauritius, Mexico, Micronesia Fed. States, Moldova, Monaco, Montenegro, Mozambique, Namibia, Nepal, Netherlands, Nicaragua, Nigeria, North Macedonia, Norway, Pakistan, Panama, Papua New Guinea, Paraguay, Peru, Philippines, Poland, Portugal, Romania, Russian Federation, Rwanda, Samoa, Saudi Arabia, Seychelles, Singapore, Sint Maarten (Dutch part), Slovak Republic, Slovenia, Solomon Islands, South Africa, Spain, Sri Lanka, St. Lucia, St. Vincent and the Grenadines, Sweden, Switzerland, Tanzania, Thailand, Tonga, Trinidad and Tobago, Turkey, Uganda, United Arab Emirates, United Kingdom, United States, Uruguay, Uzbekistan, Viet Nam, West Bank and Gaza, Zambia.

- C2 = Central African Republic, Chad, Comoros, Cyprus, Equatorial Guinea, Greece, San Marino, St. Kitts and Nevis, Tajikistan, Ukraine.

- C1: Afghanistan, Albania, Algeria, Angola, Antigua and Barbuda, Bangladesh, Barbados, Belarus, Bhutan, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Bulgaria, Cameroon, Congo, Rep., Croatia, Curacao, Djibouti, Dominica, Eswatini, Gabon, Gambia, The, Ghana, Guinea, Hungary, India, Iraq, Ireland, Italy, Kazakhstan, Kenya, Kyrgyz Republic, Lebanon, Madagascar, Malawi, Maldives, St. Vincent and the Grenadines, Mozambique, Moldova, St. Lucia, Portugal, Slovenia, Romania, Nigeria, Pakistan, Tanzania, Sint Maarten (Dutch part), Russian Federation, Zambia, Solomon Islands, Montenegro, North Macedonia.

- C2: Ukraine, Greece, Tajikistan, Comoros, Cyprus, Chad, St. Kitts and Nevis, Central African Republic, Equatorial Guinea, San Marino.

- C3: Austria, Argentina, Armenia, Belgium, Australia, Guatemala, Fiji, Brunei Darussalam, Cambodia, Colombia, France, Congo, Dem. Rep., Honduras, Denmark, Grenada, Brazil, Ecuador, Hong Kong SAR, Jordan, Dominican Republic, El Salvador, Iceland, Costa Rica, Finland, Estonia, Czechia, Canada, China, Israel, Bolivia, Germany, Botswana, Ethiopia, Georgia, Indonesia, Chile, South Africa, Malta, Micronesia, Fed. Sts., Saudi Arabia, Poland, Lithuania, Panama, Luxembourg, Philippines, Latvia, Peru, Spain, Kuwait, Paraguay, Norway, Macao SAR, China, Netherlands, Samoa, Lesotho, Nepal, Rwanda, Mauritius, Namibia, Nicaragua, Papua New Guinea, Malaysia, Slovak Republic, Mexico, Kosovo, Singapore, Seychelles, Monaco, Korea, Rep., Uruguay, United Kingdom, West Bank and Gaza, Uzbekistan, Trinidad and Tobago, United Arab Emirates, Switzerland, Sri Lanka, Turkey, United States, Uganda, Thailand, Tonga, Viet Nam, Sweden.

Abbreviations

| Abbreviation | Definition |

| NPL | Non-Performing Loans |

| AMCs | Asset Management Companies |

| CSR | Corporate Social Responsability |

| EU | European Union |

| IMF | International Monetary Fund |

| FSB | Financial Stability Board |

| GACS | Garanzia Cartolarizzazione Sofferenze |

| R&D | Research and Development |

| SMEs | Small and Medium Enterprises |

| GII | Global Innovation Index |

| SSQ | SSQ |

| CCSE | Cultural and creative services exports, % total trade |

| ICTEXP | ICT services exports, % total trade |

| ICTIMP | ICT services imports, % total trade |

| ICT | Information and communication technologies (ICTs) |

| SDGs | Sustainable Development Goals |

| BRICS | Brazil, Russia, India, China, South Africa |

| OECD | Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development |

References

- Aglietta, M., & Scialom, L. (2009). Permanence and innovation in central banking policy for financial stability. In Financial Institutions and Markets: 2007–2008—The Year of Crisis (pp. 187-211). New York: Palgrave Macmillan US.

- Aiyar, M. S., Bergthaler, M. W., Garrido, J. M., Ilyina, M. A., Jobst, A., Kang, M. K. H., ... & Moretti, M. M. (2015). A strategy for resolving Europe's problem loans. International Monetary Fund.

- Akbar, A., Usman, M., & Lin, T. (2024). Institutional dynamics and corporate innovation: A pathway to sustainable development. Sustainable Development, 32(3), 2474-2488.

- Alandejani, M., & Asutay, M. (2017). Nonperforming loans in the GCC banking sectors: Does the Islamic finance matter?. Research in International Business and Finance, 42, 832-854.

- Aleksandrova, A., & Khabib, M. D. (2022). The role of information and communication technologies in a country’s GDP: A comparative analysis between developed and developing economies. Economic and Political Studies, 10(1), 44-59.

- Ali, A., Sabir, H. M., Sajid, M., & Taqi, M. (2014). Do non performing loan affect bank performance? evidence from listed banks at Karachi stock exchange (KSE) of Pakistan. International Journal of Research in Social Sciences, 4(1), 363-377.

- An, H., Yang, R., Ma, X., Zhang, S., & Islam, S. M. (2021). An evolutionary game theory model for the inter-relationships between financial regulation and financial innovation. The North American Journal of Economics and Finance, 55, 101341.

- Anning-Dorson, T., Hinson, R. E., & Amidu, M. (2018). Managing market innovation for competitive advantage: how external dynamics hold sway for financial services. International Journal of Financial Services Management, 9(1), 70-87.

- Ashraf, B. N., & Shen, Y. (2019). Economic policy uncertainty and banks’ loan pricing. Journal of Financial Stability, 44, 100695.

- Azarenkova, G., Shkodina, I., Samorodov, B., & Babenko, M. (2018). The influence of financial technologies on the global financial system stability. Investment Management & Financial Innovations, 15(4), 229.

- Balkaran, L. (2007). Directory of global professional accounting and business certification. John Wiley & Sons.

- Bayar, Y. (2019). Macroeconomic, institutional and bank-specific determinants of non-performing loans in emerging market economies: A dynamic panel regression analysis. Journal of Central Banking Theory and Practice, 8(3), 95-110.

- Beck, T. (2018). Financial innovation and regulation. In Achieving Financial Stability: Challenges to Prudential Regulation (pp. 249-259).

- Ben Bouheni, F., Obeid, H., & Margarint, E. (2022). Nonperforming loan of European Islamic banks over the economic cycle. Annals of Operations Research, 313(2), 773-808.

- Berger, A. N., & DeYoung, R. (1997). Problem loans and cost efficiency in commercial banks. Journal of Banking & Finance, 21(6), 849-870.

- Borio, C. (2011). Rediscovering the macroeconomic roots of financial stability policy: Journey, challenges, and a way forward. Annual Review of Financial Economics, 3(1), 87-117.

- Boudriga, A., Boulila Taktak, N., & Jellouli, S. (2009). Banking supervision and nonperforming loans: a cross-country analysis. Journal of financial economic policy, 1(4), 286-318.

- Boz, E., & Mendoza, E. G. (2014). Financial innovation, the discovery of risk, and the US credit crisis. Journal of Monetary Economics, 62, 1-22.

- Brühl, V. (2021). Green Finance in Europe — Strategy, Regulation and Instruments. Intereconomics, 56(6), 323-330.

- Cerruti, C., & Neyens, R. (2016). Public asset management companies: a toolkit. World Bank Publications.

- Chien, F., Pantamee, A. A., Hussain, M. S., Chupradit, S., Nawaz, M. A., & Mohsin, M. (2021). Nexus between financial innovation and bankruptcy: evidence from information, communication and technology (ICT) sector. The Singapore Economic Review, 1-22.

- Çifter, A. (2015). Bank concentration and non-performing loans in Central and Eastern European countries. Journal of Business Economics and Management, 16(1), 117-137.

- Dash, R. K., & Parida, P. C. (2012). Services trade and economic growth in India: an analysis in the post-reform period. International Journal of Economics and Business Research, 4(3), 326-345.

- De Roest, K., Ferrari, P., & Knickel, K. (2018). Specialisation and economies of scale or diversification and economies of scope? Assessing different agricultural development pathways. Journal of Rural Studies, 59, 222-231.

- Degl'Innocenti, M., Grant, K., Šević, A., & Tzeremes, N. G. (2018). Financial stability, competitiveness and banks' innovation capacity: Evidence from the Global Financial Crisis. International Review of Financial Analysis, 59, 35-46.

- Delimatsis, P. (2013). Transparent financial innovation in a post-crisis environment. Journal of International Economic Law, 16(1), 159-210.

- Dimitrios, A., Helen, L., & Mike, T. (2016). Determinants of non-performing loans: Evidence from Euro-area countries. Finance Research Letters, 18, 116-119.

- Duong, K. D., Huynh, T. N., Van Nguyen, D., & Le, H. T. P. (2022). How innovation and ownership concentration affect the financial sustainability of energy enterprises: evidence from a transition economy. Heliyon, 8(9).

- Fofack, H. (2005). Nonperforming loans in Sub-Saharan Africa: causal analysis and macroeconomic implications (Vol. 3769). World Bank Publications.

- Fostel, A., Geanakoplos, J., & Phelan, G. (2017). Global collateral: How financial innovation drives capital flows and increases financial instability.

- García-Romero, A., Navarrete Cortés, J., Escudero, C., Fernández López, J. A., & Chaichío Moreno, J. A. (2009). Measuring the influence of clinical trials citations on several bibliometric indicators. Scientometrics, 80, 747-760.

- Githaiga, P. N. (2020). Revenue diversification and quality of loan portfolio. Journal of Economics and Management, 42(4), 5-19.

- Goswami, A. G., Gupta, P., & Mattoo, A. (2012). A cross-country analysis of service exports: lessons from India. Exporting Services-A Developing Country Perspective, 81-119.

- Goswami, A. K., Gupta, C. P., & Singh, G. K. (2011). Minimization of voltage sag induced financial losses in distribution systems using FACTS devices. Electric Power Systems Research, 81(3), 767-774.

- Gouvea, R., & Vora, G. (2016). Global trade in creative services: an empirical exploration. Creative Industries Journal, 9(1), 66-93.

- Gouvea, R., & Vora, G. (2018). Creative industries and economic growth: stability of creative products exports earnings. Creative Industries Journal, 11(1), 22-53.

- Gubler, Z. J. (2011). The financial innovation process: Theory and application. Delaware Journal of Corporate Law, 36, 55.

- Gürler, M. (2023). The effect of digitalism on the economic growth and foreign trade of creative, Information and Communication Technology (ICT) and high-tech products in OECD countries. The European Journal of Research and Development, 3(2), 54-79.

- Gutiérrez-López, C., & Abad-González, J. (2020). Sustainability in the Banking Sector: A Predictive Model for the European Banking Union in the Aftermath of the Financial Crisis. Sustainability, 12(6), 2566.

- Hagsten, E., & Kotnik, P. (2017). ICT as facilitator of internationalisation in small-and medium-sized firms. Small Business Economics, 48, 431-446.

- Hassania, S., & Eghdami, E. (2023). Investigating the moderating role of corporate governance in the relationship between innovation and financial stability with the growth of banks listed on the Tehran stock exchange. Financial and Banking Strategic Studies, 1(2), 126-138.

- He, D. (2004). The role of KAMCO in resolving nonperforming loans in the Republic of Korea. In Bank Restructuring and Resolution (pp. 348-368). London: Palgrave Macmillan UK.

- He, D., Miao, P., & Qureshi, N. A. (2022). Can industrial diversification help strengthen regional economic resilience?. Frontiers in Environmental Science, 10, 987396.

- Holden, G. (2013). Kenya's Fertile Ground for Tech Innovation. Research-technology Management, 56(7).

- Huljak, I., Martin, R., Moccero, D., & Pancaro, C. (2022). Do non-performing loans matter for bank lending and the business cycle in euro area countries?. Journal of Applied Economics, 25(1), 1050-1080.

- Ihebuluche, M. F. C., Adekunle, M. W., Katanga, M. S., Joshi, S., Parimoo, D., & Sangal, A. (2022). Nexus between financial innovation and central bank independence: Evidence from some selected OECD countries. Journal of Positive School Psychology, 3418-3430.

- Illy, O., & Ouedraogo, S. (2020). West African Economic and Monetary Union. The Political Economy of Bank Regulation in Developing Countries, 1.

- Iris, H. Y. (2017). A rational regulatory strategy for governing financial innovation. European Journal of Risk Regulation, 8(4), 743-765.

- Ismanto, H., Wibowo, P. A., & Shofwatin, T. D. (2023). Bank stability and fintech impact on MSMES’credit performance and credit accessibility. Banks and Bank Systems, 18, 105-115.

- Jakubík, P., & Reininger, T. (2013). Determinants of nonperforming loans in Central, Eastern and Southeastern Europe. Focus on European Economic Integration, (3), 48-66.

- Jenkins, C. (2001). Manuscripts submitted by corresponding authors residing outside the United States. American Journal of Roentgenology, 177(4), 746-746.

- Jenkinson, N., Penalver, A., & Vause, N. (2008). Financial innovation: What have we learnt?. Bank of England Quarterly Bulletin, (2008), Q3.

- Jeong, H., Shin, K., Kim, E., & Kim, S. (2020). Does open innovation enhance a large firm’s financial sustainability? A case of the Korean food industry. Journal of Open Innovation: Technology, Market, and Complexity, 6(4), 101.

- Jia, Z., Mehta, A. M., Qamruzzaman, M., & Ali, M. (2021). Economic policy uncertainty and financial innovation: Is there any affiliation?. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 631834.

- Jianing, P., Bai, K., Solangi, Y. A., Magazzino, C., & Ayaz, K. (2024). Examining the Role of Digitalization and Technological Innovation in Promoting Sustainable Natural Resource Exploitation. Resources Policy, 92, 105036.

- Katsampoxakis, I., & Basdekis, C. (2022). Factors Affecting Non-Performing Loans in Europe Before and After Global Financial Crisis. International Journal of Managerial Studies and Research.

- Khalatur, S., Pavlova, H., Vasilieva, L., Karamushka, D., & Danileviča, A. (2022). Innovation management as basis of digitalization trends and security of financial sector. Entrepreneurship and Sustainability Issues, 9(4), 56.

- Kim, H., Batten, J. A., & Ryu, D. (2020). Financial crisis, bank diversification, and financial stability: OECD countries. International Review of Economics & Finance, 65, 94-104.

- Kim, M., & Park, J. (2017). Do Bank Loans To Financially Distressed Firms Lead To Innovation?. The Japanese Economic Review, 68(2), 244-256.

- Klein, N. (2013). Non-performing loans in CESEE: Determinants and impact on macroeconomic performance. International Monetary Fund.

- Koch, C. (2004). Innovation networking between stability and political dynamics. Technovation, 24(9), 729-739.

- Kolodiziev, O., Chmutova, I., & Biliaieva, V. (2016). Selecting a kind of financial innovation according to the level of a bank's financial soundness and its life cycle stage. Banks and Bank Systems, 11(4).

- Korepanov, G., Yatskevych, I., Popova, O., Shevtsiv, L., Marych, M., & Purtskhvanidze, O. (2020). Managing the financial stability potential of crisis enterprises. International Journal of Advanced Research in Engineering and Technology, 11(4).

- Kossele, T. P. Y., & Shan, L. (2018). Economic Security and the Political Governance Crisis in Central African Republic. African Development Review.

- Kurniawati, M. (2020). The role of ICT infrastructure, innovation and globalization on economic growth in OECD countries, 1996-2017. Journal of Science and Technology Policy Management, 11(2), 193-215.

- Lane, D. A. (2011). Complexity and innovation dynamics. In Handbook on the economic complexity of technological change. Edward Elgar Publishing.

- Laryea, E., Ntow-Gyamfi, M., & Alu, A. A. (2016). Nonperforming loans and bank profitability: evidence from an emerging market. African Journal of Economic and Management Studies, 7(4), 462-481.

- Lauretta, E. (2018). The hidden soul of financial innovation: An agent-based modelling of home mortgage securitization and the finance-growth nexus. Economic Modelling, 68, 51-73.

- Le, T. D., Nguyen, V. T., & Tran, S. H. (2020). Geographic loan diversification and bank risk: A cross-country analysis. Cogent Economics & Finance, 8(1), 1809120.

- Lee, C. C., Wang, C. W., & Ho, S. J. (2020). Financial innovation and bank growth: The role of institutional environments. The North American Journal of Economics and Finance, 53, 101195.

- Lee, J., & Rosenkranz, P. (2020). Nonperforming loans in Asia: Determinants and macrofinancial linkages. In Emerging market finance: new challenges and opportunities (pp. 33-53). Emerald Publishing.

- Li, L., & Sun, Q. (2019, February). Research on the Factors of China's Cultural and Creative Products Export Trade: An Empirical Analysis Based on Constant Market Share Model. In Proceedings of the 2019 5th International Conference on E-Business and Applications (pp. 110-113).

- López-Cálix, J. (2020). Leveraging export diversification in fragile countries: the emerging value chains of Mali, Chad, Niger, and Guinea. World Bank Publications.

- López-Penabad, M. C., Iglesias-Casal, A., & Neto, J. F. S. (2021). Competition and financial stability in the European listed banks. Sage Open, 11(3), 21582440211032645.

- Lumpkin, S. (2010). Regulatory issues related to financial innovation. OECD Journal: Financial Market Trends, 2009(2), 1-31.

- Ma, G., & Fung, B. S. (2006). Using asset management companies to resolve non-performing loans in China. Journal of Financial Transformation, 18, 161-169.

- Magazzino, C., Alola, A. A., & Schneider, N. (2021b). The Trilemma of Innovation, Logistics Performance, and Environmental Quality in 25 topmost Logistics Countries: A Quantile Regression Evidence. Journal of Cleaner Production, 322, 129050.

- Magazzino, C., Mele, M., & Santeramo, F. G. (2021a). Using an Artificial Neural Networks experiment to assess the links among financial development and growth in agriculture. Sustainability, 13, 5, 2828.

- Magazzino, C., Santeramo F. G., & Schneider, N. (2024). The credit-output-productivity nexus: A comprehensive review. International Review of Environmental and Resource Economics, 18, 1-2, 77-121.

- Magazzino, C., & Santeramo, F. G. (2023). Financial Development, Growth, and Productivity. Journal of Economic Studies.

- McFerson, H. M. (2009). Governance and Hyper-corruption in Resource-rich African Countries. Third World Quarterly, 30(10), 1529-1547.

- Michalopoulos, S., Laeven, L., & Levine, R. (2009). Financial innovation and endogenous growth. National Bureau of Economic Research, w15356.

- Mikhaylov, A., Dinçer, H., & Yüksel, S. (2023). Analysis of financial development and open innovation oriented fintech potential for emerging economies using an integrated decision-making approach of MF-X-DMA and golden cut bipolar q-ROFSs. Financial Innovation, 9(1), 4.

- Minto, A., Voelkerling, M., & Wulff, M. (2017). Separating apples from oranges: Identifying threats to financial stability originating from FinTech. Capital Markets Law Journal, 12(4), 428-465.

- Molochko, A. F. (2001). Basic direction of energy saving policies in the Republic of Belarus. International Journal of Global Energy Issues, 16(1), 6-14.

- Mpofu, T. R., & Nikolaidou, E. (2018). Determinants of credit risk in the banking system in Sub-Saharan Africa. Review of Development Finance, 8(2), 141-153.

- Msomi, T. S. (2022). Factors affecting non-performing loans in commercial banks of selected West African countries. Banks and Bank Systems, 17(1), 1.

- Nesvetailova, A. (2008). Three facets of liquidity illusion: Financial innovation and the credit crunch. German Policy Studies, 4(3).

- Nimbrayan, P. K., Tanwar, N., & Tripathi, R. K. (2018). Pradhan mantri jan dhan yojana (PMJDY): The biggest financial inclusion initiative in the world. Economic Affairs, 63(2), 583-590.

- Obadire, A. M., Moyo, V., & Munzhelele, N. F. (2022). Basel III capital regulations and bank efficiency: Evidence from selected African Countries. International Journal of Financial Studies, 10(3), 57.

- Okrah, J., & Hajduk-Stelmachowicz, M. (2020). Political stability and innovation in Africa. Journal of International Studies (2071-8330), 13(1).

- Onyshchenko, V., Yehorycheva, S., Maslii, O., & Yurkiv, N. (2020, June). Impact of innovation and digital technologies on the financial security of the state. In International Conference Building Innovations (pp. 749-759). Cham: Springer International Publishing.

- Osuji, O. (2012). Asset management companies, non-performing loans and systemic crisis: A developing country perspective. Journal of Banking Regulation, 13, 147-170.

- Ozili, P. K. (2019). Non-performing loans and financial development: new evidence. The Journal of Risk Finance, 20(1), 59-81.

- Ozili, P. K., & Iorember, P. T. (2023). Financial stability and sustainable development. International Journal of Finance & Economics.

- Pan, X., Uddin, M. K., Han, C., & Pan, X. (2019). Dynamics of financial development, trade openness, technological innovation and energy intensity: Evidence from Bangladesh. Energy, 171, 456-464.

- Park, C. Y., & Shin, K. (2020). The Impact of Nonperforming Loans on Cross-Border Bank Lending: Implications for Emerging Market Economies. Asian Development Bank, 136.

- Pernell, K. (2020). Market governance, financial innovation, and financial instability: lessons from banks’ adoption of shareholder value management. Theory and Society, 49(2), 277-306.

- Pierri, M. N., & Timmer, M. Y. (2020). Tech in fin before fintech: Blessing or curse for financial stability?. International Monetary Fund.

- Pradhan, R. P., Arvin, M. B., Nair, M., Bennett, S. E., Bahmani, S., & Hall, J. H. (2018). Endogenous dynamics between innovation, financial markets, venture capital and economic growth: Evidence from Europe. Journal of Multinational Financial Management, 45, 15-34.

- Priem, R. (2022). A European distributed ledger technology pilot regime for market infrastructures: finding a balance between innovation, investor protection and financial stability. Journal of Financial Regulation and Compliance, 30(3), 371-390.

- Próchniak, M., & Wasiak, K. (2016). The impact of macroeconomic performance on the stability of financial system in the EU countries. Collegium of Economic Analysis Annals, (41), 145-160.

- Punhani, A., Faujdar, N., Mishra, K. K., & Subramanian, M. (2022). Binning-based silhouette approach to find the optimal cluster using K-means. IEEE Access, 10, 115025-115032.

- Radicchi, F., & Castellano, C. (2013). Analysis of bibliometric indicators for individual scholars in a large data set. Scientometrics, 97, 627-637.

- Rubini, L., & Wang, T. (2020). State-owned enterprises. In Handbook of deep integration agreements (pp. 463-502). The World Bank.

- Saha, M., & Dutta, K. D. (2021). Nexus of financial inclusion, competition, concentration and financial stability: Cross-country empirical evidence. Competitiveness Review: An International Business Journal, 31(4), 669-692.

- Salleo, C. (2018). How technological innovation will reshape financial regulation. In Achieving Financial Stability: Challenges to Prudential Regulation (pp. 279-291).

- Santos-Arteaga, F. J., Tavana, M., Torrecillas, C., & Di Caprio, D. (2020). Innovation dynamics and financial stability: A European Union perspective. Technological and Economic Development of Economy 26.6 (2020): 1366-1398.

- Savchuk, N., Bludova, T., Leonov, D., Murashko, O., & Shelud’ko, N. (2021). Innovation imperatives of global financial innovation and development of their matrix models. Innovations, 18(3), 312-326.

- Saydaliev, H. B., Kamzabek, T., Kasimov, I., Chin, L., & Haldarov, Z. (2022). Financial inclusion, financial innovation, and macroeconomic stability. In Innovative Finance for Technological Progress (pp. 27-45). Routledge.

- Serrano, A. S. (2021). The impact of non-performing loans on bank lending in Europe: An empirical analysis. The North American Journal of Economics and Finance, 55, 101312.

- Shapoval, Y. (2021). Relationship between financial innovation, financial depth, and economic growth. Investment Management and Financial Innovations, 18(4), 203-212.

- Shen, L., He, G., & Yan, H. (2022). Research on the impact of technological finance on financial stability: Based on the perspective of high-quality economic growth. Complexity, 2022(1), 2552520.

- Sinha, A. (2018). Impact of ICT exports and internet usage on carbon emissions: a case of OECD countries. International Journal of Green Economics, 12(3-4), 228-257.

- Škarica, B. (2014). Determinants of non-performing loans in Central and Eastern European countries. Financial Theory and Practice, 38(1), 37-59.

- Smits, J., & Permanyer, I. (2019). The subnational human development database. Scientific Data, 6(1), 1-15.

- Solangi, Y. A., Alyamani, R., & Magazzino, C., (2024). Assessing the Drivers and Solutions of Green Innovation Influencing the Adoption of Renewable Energy Technologies. Heliyon, 10, 9, E30158.

- Thaci, L. G. (2013). Economic growth in Kosovo and in other countries in terms of globalization of world economy. Academicus International Scientific Journal, 4(08), 231-242.

- Tmava, Q., Avdullahi, A., & Sadikaj, B. (2018). Loan portfolio and nonperforming loans in Western Balkan Countries. International Journal of Finance & Banking Studies (2147-4486), 7(4), 10-20.

- Ülgen, F. (2014). Schumpeterian economic development and financial innovations: a conflicting evolution. Journal of Institutional Economics, 10(2), 257-277.

- Ullah, A., Pinglu, C., Ullah, S., Qian, N., & Zaman, M. (2023). Impact of intellectual capital efficiency on financial stability in banks: Insights from an emerging economy. International Journal of Finance & Economics, 28(2), 1858-1871.

- Vogiazas, S., & Nikolaidou, E. (2011). Investigating the Determinants of Nonperforming Loans in the Romanian Banking System: An Empirical Study with Reference to the Greek Crisis. Economics Research International, 2011, 1-13.

- Wahab, S., Imran, M., Safi, A., Wahab, Z., & Kirikkaleli, D. (2022). Role of financial stability, technological innovation, and renewable energy in achieving sustainable development goals in BRICS countries. Environmental Science and Pollution Research, 29(32), 48827-48838.

- Wang, M., & Choi, C. (2018). How information and communication technology affect international trade: a comparative analysis of BRICS countries. Information Technology for Development, 25(4), 455-474.

- Warue, B. N. (2013). The effects of bank specific and macroeconomic factors on nonperforming loans in commercial banks in Kenya: A comparative panel data analysis. Advances in Management and Applied Economics, 3(2), 135.

- Weißbach, R., & von Lieres und Wilkau, C. (2010). Economic capital for nonperforming loans. Financial Markets and Portfolio Management, 24, 67-85.

- Welfens, P., & Perret, J. (2014). Information & communication technology and true real GDP: economic analysis and findings for selected countries. International Economics and Economic Policy, 11(1), 5-27.

- Wijayanto, G., Novandalina, A., & Rivai, Y. (2023). The uniting innovation and stability: The key to business flexibility. Ambidextrous: Journal of Innovation, Efficiency and Technology in Organization, 1(01), 09-17.

- Wolde, F., & Geta, E. (2015). Determinants of growth and diversification of micro and small enterprises: the case of Dire Dawa, Ethiopia. Developing Country Studies, 5(1), 61-75.

- Wu, B., & Gong, C. (2019). Impact of open innovation communities on enterprise innovation performance: A system dynamics perspective. Sustainability, 11(17), 4794.

- Xu, S., Qamruzzaman, M., & Adow, A. H. (2021). Is financial innovation bestowed or a curse for economic sustainability: the mediating role of economic policy uncertainty. Sustainability, 13(4), 2391.

- Yuan, C., & Yang, H. (2019). Research on K-value selection method of K-means clustering algorithm. J, 2(2), 226-235.

- Yun, J. J., Won, D., & Park, K. (2018). Entrepreneurial cyclical dynamics of open innovation. Journal of Evolutionary Economics, 28(5), 1151-1174.

- Zouari, G., & Abdelmalek, I. (2020). Financial innovation, risk management, and bank performance. Copernican Journal of Finance & Accounting, 9(1), 77-100.

| Macro theme | References |

|---|---|

| inancial Innovation and Stability | Santos-Arteaga et al. (2020); Priem (2022); Shapoval (2021); Chien et al. (2021); Lee et al. (2020); Shen et al. (2022); Ozili and Iorember (2023); Wijayanto et al. (2023); Jeong et al. (2020); López-Penabad et al. (2021); Ihebuluche et al. (2022); Korepanov et al. (2020); Duong et al. (2022); Hassania and Eghdami (2023); Xu et al. (2021); Zouari and Abdelmalek (2020); Kim et al. (2020); Pernell (2020); Ullah et al. (2023); Saha and Dutta (2021); Degl'Innocenti et al. (2018); Saydaliev et al. (2022); Koch (2004); Fostel et al. (2017); Aglietta and Scialom (2009); Ülgen (2013). |

| Technological Innovation and Sustainable Development | Wahab et al. (2022); Pan et al. (2019); Khalatur et al. (2022); Salleo (2018); Jeong et al. (2020); Akbar et al. (2024); Michalopoulos et al. (2009); Gubler (2011); Mikhaylov et al. (2023); Anning-Dorson et al. (2018); Kolodiziev et al. (2016); Boz and Mendoza (2014); Lane (2011); Okrah and Hajduk-Stelmachowicz (2020); Beck (2018); Jenkinson et al. (2008); Jia et al. (2021); Wu and Gong (2019); Nesvetailova (2008); Savchuk et al. (2021); An et al. (2021); Onyshchenko et al. (2020); Magazzino et al., (2024); Magazzino and Santeramo (2023); Magazzino et al., (2021a); Magazzino et al. (2021b); Solangi et al., (2024); Jianing et al., (2024). |

| Market Dynamics and Competitive Advantage | Pradhan et al. (2018); Gubler (2011); Lauretta (2018); Yun et al. (2018); Okrah and Hajduk-Stelmachowicz (2020); Ülgen (2014); Khalatur et al. (2022); Akbar et al. (2024); Pan et al. (2019); Beck (2018); Jia et al. (2021); Mikhaylov et al. (2023); Wu and Gong (2019); Nesvetailova (2008); Delimatsis (2013); Salleo (2018). |

| Variable | Definition | Acronym | Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bank non-performing loans to total gross loans (%) | A financial indicator that measures the proportion of NPLs relative to the total gross loans issued by a bank. This ratio is a key metric for assessing the health and quality of a bank's loan portfolio and its exposure to credit risk. A loan is classified as non-performing when the borrower fails to make scheduled payments of interest or principal for a significant period, typically 90 days or more. Additionally, a loan may be considered non-performing if it is deemed unlikely that the debt will be repaid in full without the bank having to seize the collateral. Total gross loans, on the other hand, refer to the aggregate value of all loans granted by the bank, without deducting any allowances for potential losses or write-downs. This includes all categories of loans issued, from mortgages and personal loans to commercial and industrial loans. The non-performing loans to total gross loans (%) ratio is calculated by dividing the value of non-performing loans by the total gross loans and multiplying the result by 100 to express it as a percentage. It reflects the bank's vulnerability to credit risk, as a large number of non-performing loans can erode profitability, deplete capital reserves, and ultimately affect the bank's ability to operate effectively (Jakubík and Reininger, 2013; Mpofu and Nikolaidou, 2018). | NPL | World Bank |

| Citable documents H-Index | A bibliometric indicator that evaluates both the productivity and citation impact of the published academic work of a researcher, institution, or journal. The H-Index represents the highest number of papers (h) that have been cited at least h times each. This metric specifically focuses on the subset of documents that are most likely to be cited, excluding non-scholarly items such as editorials, notes, or letters to the editor. This index provides a balanced measure that combines both quantity (number of citable documents) and quality (citations per document), offering a more nuanced view of academic impact than simple citation counts or publication numbers alone. It is particularly useful for comparing the impact of researchers, journals, or institutions across different fields, as it accounts for variations in citation practices among disciplines (García-Romero et al., 2009; Radicchi and Castellano, 2013). | H-Index | Global Innovation Index |

| Cultural and creative services exports, % total trade | The portion of a country's total trade that is derived from the exportation of goods and services related to cultural and creative industries. The measurement of cultural and creative services exports as a percentage of total trade involves calculating the value of these exports relative to the total value of all exports (both goods and services) from a country. This percentage provides insight into the economic significance and contribution of the cultural and creative sectors to a country's overall trade activity. The export of cultural and creative services also helps to enhance a country's cultural influence and soft power on the global stage (Gouvea and Vora, 2016; 2018; Li and Sun, 2019). | CCSE | Global Innovation Index |

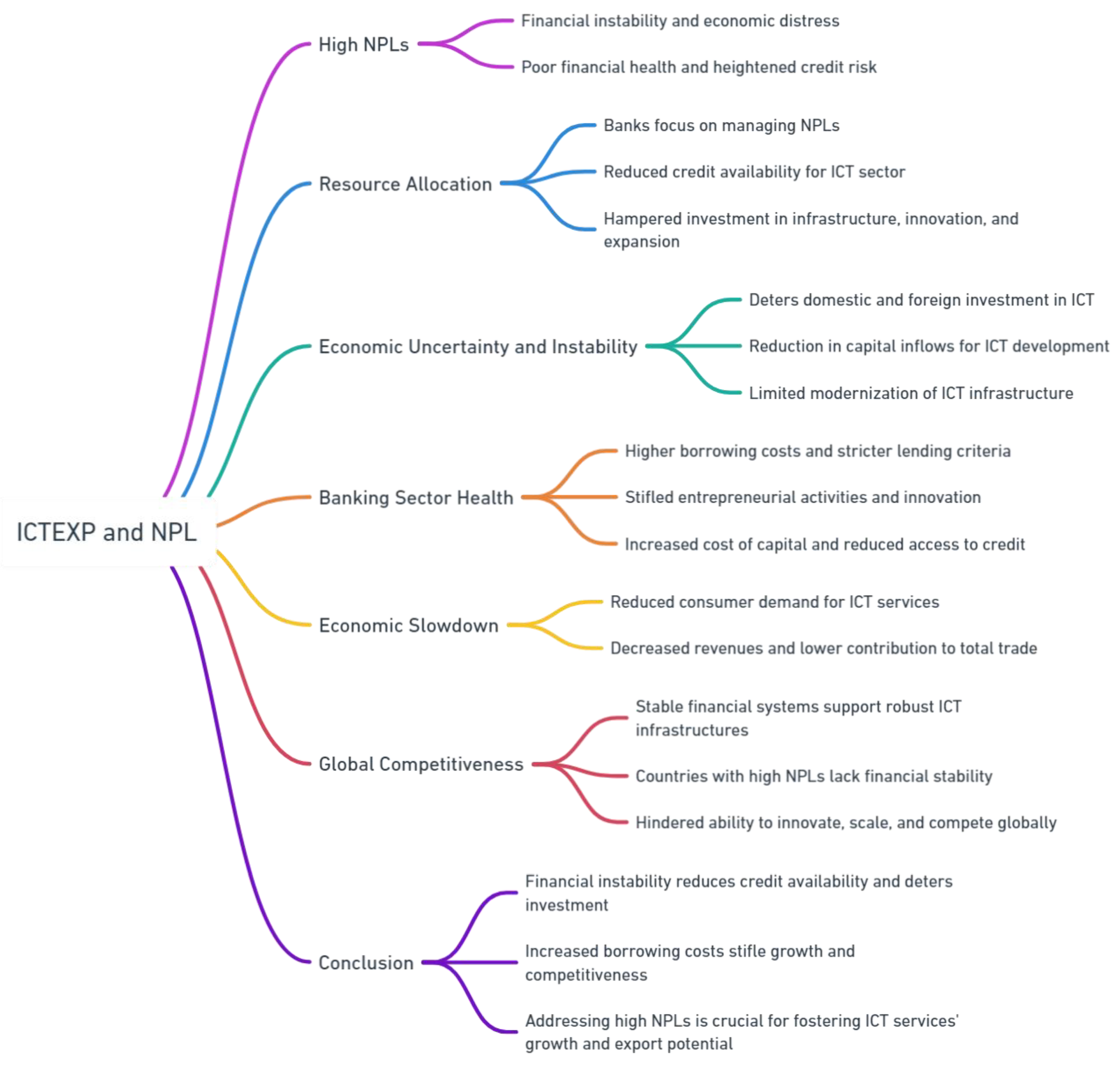

| ICT services exports, % total trade | The proportion of a country's total exports that come from the ICT sector. This metric highlights the significance of ICT services within the broader context of a nation's trade activities. ICT services encompass a range of activities, including software development, telecommunications, data processing, IT consulting, and other computer-related services. To calculate this percentage, the value of ICT services exports is divided by the total value of all exports (both goods and services) from a country and then multiplied by 100 (Hagsten and Kotnik, 2017; Sinha, 2018; Gürler, 2023). | ICTEXP | Global Innovation Index |

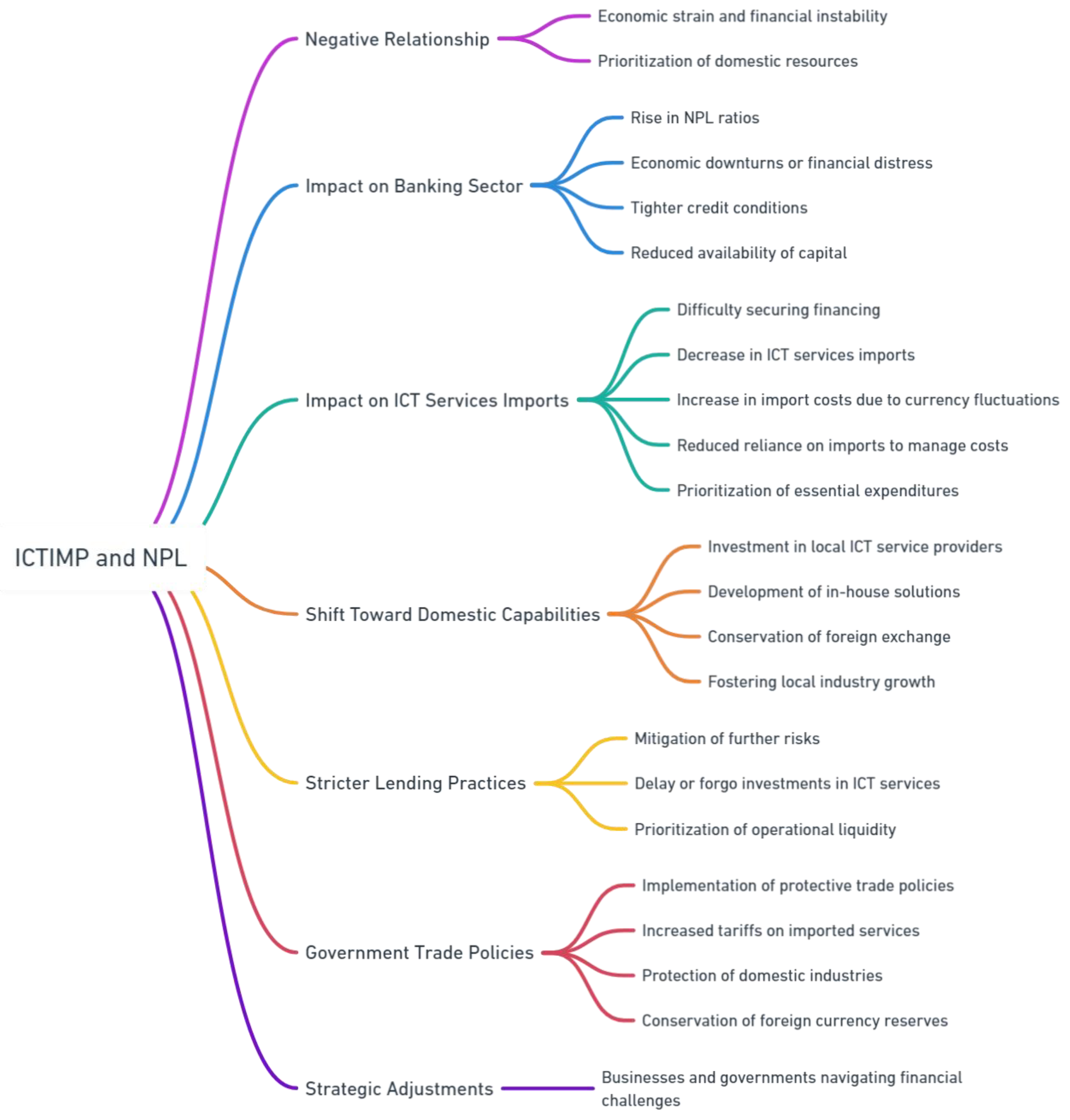

| ICT services imports, % total trade | The proportion of a country's total imports that come from the ICT sector. This metric indicates the importance and reliance on ICT services within the broader framework of a nation's trade activities. To calculate this percentage, the value of ICT services imports is divided by the total value of all imports (both goods and services) into a country, and then multiplied by 100. This calculation provides a clear understanding of how significant ICT services are to the country's overall import profile (Welfens and Perret, 2014; Wang and Choi, 2018; Aleksandrova and Khabib, 2022). | ICTIMP | Global Innovation Index |

| Information and communication technologies (ICTs) | ICTs refer to a comprehensive range of technologies that facilitate the creation, storage, transmission, and management of information. These technologies include digital tools and resources such as computers, mobile phones, the internet, and cloud computing, as well as traditional communication media like radio, television, and telephony (Kurniawati, 2020). | ICT | Global Innovation Index |

| Innovation Input Sub-Index | The Innovation Input Sub-Index is a crucial component of the Global Innovation Index (GII), which evaluates the innovation performance of countries and economies worldwide. This sub-index assesses the elements within an economy that enable and facilitate innovative activities. It is composed of five key pillars: Institutions, which capture the political, regulatory, and business environments; Human Capital and Research, which includes education, tertiary education, and research & development (R&D); Infrastructure, which assesses information and communication technologies (ICT), general infrastructure, and ecological sustainability; Market Sophistication, which looks at credit, investment, and trade and competition; and Business Sophistication, which evaluates knowledge workers, innovation linkages, and knowledge absorption. These pillars collectively provide a comprehensive view of the inputs necessary for fostering innovation within a country or economy. The Innovation Input Sub-Index, used in conjunction with the Innovation Output Sub-Index, which measures actual innovation outputs, contributes to the overall Global Innovation Index score. | ISI | Global Innovation Index |

| Fixed Effects | Random Effects | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | Coefficient | Std. Error | t-ratio | Coefficient | Std. Error | t-ratio |

| Costant | 9.39100** | 4.28037 | 2.194 | 7.68287*** | 2.17854 | 3.527 |

| H-Index | -0.238110*** | 0.0894702 | -2.661 | -0.0977559*** | 0.0352393 | -2.774 |

| CCSE | 0.0270613*** | 0.00963331 | 2.809 | 0.0277375*** | 0.00908887 | 3.052 |

| ICTEXP | -0.0294091** | 0.0130346 | -2.256 | -0.0206465* | 0.0121918 | -1.693 |

| ICTIMP | -0.0317156** | 0.0133400 | -2.377 | -0.0302631** | 0.0126215 | -2.398 |

| ICT | -0.0703288*** | 0.0167553 | -4.197 | -0.0791516*** | 0.0155227 | -5.099 |

| ISI | 0.162938** | 0.0724317 | 2.250 | 0.125901** | 0.0495078 | 2.543 |

| Statistics | SSR: 6226.843 SER: 3.319783 Log-likelihood: -1701.586 AIC: 3617.172 SBIC: 4099.769 HQIC: 3804.075 |

SSR: 35189.77 SER: 7.268940 Log-likelihood: -2283.499 AIC: 4580.999 SBIC: 4612.571 HQIC: 4593.226 |

||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).