1. Introduction

Ever since the COVID-19 pandemic, online learning has gained attention from academics in South Africa. Despite this, university’s characteristics still have an impact on how successful online learning is (Siemens, Gašević, & Dawson, 2015). There is disparity among South African universities; some are comprised of developed features, while others are comprised of developing traits (Archer, 2017). It is not common practice to designate certain universities in South Africa as "developing universities." On the other hand, the concept of developing universities characterises those that were historically disadvantaged and continue to exhibit indicators of disadvantage following South Africa's transition to democracy (Badat & Sayed, 2014). According to Trahar et al. (2020), institutions in South Africa that cater mostly to black students and are situated in rural or economically deprived areas are classified as developing universities. Among these universities are Walter Sisulu University, University of Limpopo, University of Fort Hare, University of Venda, and University of Zululand. As historically disadvantaged institutions (HDIs) or previously disadvantaged institutions (PDIs), these universities were adversely affected by apartheid and have been allocated resources and attention to mitigate educational disparities, including addressing educational inequalities (Yakobi et al. 2022).

The adoption of ICT in developing universities in South Africa remains a challenge because these institutions lack sufficient digital infrastructure and resources, including reliable access to the internet and computers or mobile devices for online learning (Aruleba & Jere, 2022; Chisango & Marongwe, 2021; Nyahodza & Higgs, 2017). These challenges consistently made it more difficult for educators and students to participate in online learning activities successfully before the advent of COVID19 (Takalani, 2008). Despite the recent widespread use of online resources in developing universities, a considerable proportion of students still lacks access to reliable internet connections or personal computers because of their economic status (Mpungose, 2020). Online learning support in South African developing universities continues to face a number of challenges even after the COVID 19 period. These challenges are mostly shared by developing countries but are exacerbated by South Africa's unique socioeconomic environment (Dube, 2020). Students from low-income backgrounds are disproportionately affected by the digital gap, which also makes already-existing disparities in educational access exacerbated (Nyahodza & Higgs, 2017). Azionya and Nhedzi (2021) state that costs and affordability is a major obstacle for a large number of South African students, especially when it comes to online learning where they could have to pay for data bundles or access online resources. Due to this, a large number of students were either unable to participate completely in online courses or were forced to make decisions on how to meet their basic needs before they could access educational materials (Landa, Zhou & Marongwe, 2021). The fact that the majority of students at developing universities come from low-income families and find it difficult to pay for study materials, housing, and tuition is another major issue that many of them encounter (Walker, 2020). According to Nguyen, Kramer, and Evans (2019), financial aid and scholarship possibilities are essential for providing these students with the support they need to concentrate on their studies.

The main problem addressed in this paper is a limited research on how online learning support as a pedagogical strategy contributed to students' learning experiences in the context of developing universities in South Africa. The purpose of this paper is to investigate the extent of online learning support as a pedagogical strategy for student learning at developing universities. The paper is structured as follows: An overview of student learning context in a developing university is presented in

Section 2. The research methodology is explained in

Section 3. Literature review findings and results are provided in

Section 4. Conclusions and recommendations are made in

Section 5.

2. Student Learning Context in a Developing Universities

There are some observable structural components that clearly define the developing universities in South Africa, these components are connected to their historical context and organisational culture. The outcomes of the university merger and incorporation process to most of the developing universities in South Africa came about when the government of South Africa proposed institutional change and institutional consolidation of higher education institutions between the period of 2004 and 2008 (Hall, 2015). According to Badat (2009), “social-structural and conjunctural variables should be taken into account while theorising institutional transformation, particularly the merger and incorporation of institutions”. The synchronisation of learning and teaching activities, however, still suffers from a lack of smooth transition and transformation. From the beginning of merger and incorporation, the university's vision and mission's goals for learning and teaching were hampered by the organisational setting's complexity and culture. According to Barnett's (2005), managing a university will always entail managing complexity. Just a few of the characteristics of universities as organisations include systems, infrastructure, values, information, income streams, knowledge, structures, disciplines, discourses, and activities. Mostly, the developing universities struggle with the harmonisation of organisational systems to the point that some of them, after 19 years of merger and incorporation, are still thinking of applying a process of rationalisation and consolidation of faculties.

In South Africa, developing universities continues to also struggle with a variety of issues related to legacy systems that have a direct impact on teaching and learning (Mouton, Louw & Strydom, 2013). For example, developing universities in South Africa continue to face challenges related to poor infrastructure, which includes antiquated buildings, limited financial resources for libraries, and inadequate laboratory equipment (Nyahodza & Higgs, 2017). This regularly compromises students' access to high-quality education and real-world learning opportunities. Even though these universities employ committed educators, the general calibre of teaching varies constantly (Alkaabi et al., 2023). The quality of teaching and learning can be impacted by a number of issues, including high student-to-teacher ratios, few opportunities for lecturers to pursue professional development, and a lack of funding for research (Kawuryan, Sayuti, and Dwiningrum, 2021).

In the developing universities there is prevalent academic staff politics and prejudice because of the legacy systems caused by merger and incorporation of institutions (Rensburg, 2020). For instance, some academic staff members have a research-driven viewpoint and feel that learning and teaching should be informed by research activities, whilst others do not see the importance of participating in research activities as a contributing factor to better learning and teaching. Young (2008) strongly believes that the enhancement of teaching with the explicit goal of boosting student learning is a crucial part of academic progress.

As rightfully noted by Kandlbinder (2014) it is important for instruction to be well planned to involve students in learning activities that maximise their chances of reaching intended outcomes, and evaluation tasks should be planned to allow for accurate evaluations of how well those outcomes have been achieved. A considerable number of educators and students lack familiarity with digital technologies and online learning platforms, which makes it challenging for them to use these resources efficiently (Bagarukayo & Kalema, 2015; Takalani, 2008). Roddy et al. (2017) suggest that training and support for both students and educators are still essential in developing universities to ensure they can make the most of online learning opportunities.

3. Online Learning in Developing Universities

The fact that online learning depends on technology, such as the internet and computers, is the most obvious difficulty educators at developing universities come across daily (Agormedah et al., 2020). In some cases, interruptions or other system faults that occurred during classes prevented students from using the internet or computers (Gonzales, McCrory Calarco & Lynch, 2020). In many instances, there isn't actually a computer lab that is equipped, set up, and ready to be used in support of student learning or even for assessment purposes (Hamilton, 2022). Rapanta et al. (2020) confirm that limited computer labs within the universities create complexities for developing universities to promote online learning space. The number of functioning computers in the labs is always limited. As a result, during COVID19 lockdown some educators usually let students utilise the computers they were given as responsive mechanism, when practically all universities were turning to online education (Mishra, Gupta & Shree, 2020). However, such attempts to provide laptops were abandoned after COVID19 lockdown restrictions were lifted; as a result, many students still lack access to the devices needed for online learning, including laptops, tablets, and mobile devices (Hlatshwayo, 2022; Mpungose, 2020). As per Banerjee, M. (2022), students from lower-income households and those who reside in rural areas are disproportionately impacted by this digital gap. The majority of students also frequently deal with challenges such frequent load-shedding that impede communication and inadequate network coverage (internet connection) brought on by their rural locations (Simelane, 2021).

Another significant obstacle is reliable internet connection, particularly in many South African regions, especially rural ones, where internet infrastructure is either non-existent or insufficient (Johnson, 2013). The cost of data bundles can make numerous participation in online learning unaffordable, even in urban locations (Kreutzer, 2009). In relation to income levels, South Africa has among of the highest data bundle costs globally. Due to this, using online learning platforms frequently and for extended periods of time can be costly for many families (Mukuna & Aloka, 2020). According to Tate and Warschauer (2022), the majority of students cannot afford enough data to participate in online assessments, download resources, or attend virtual classes. According to Mbaleki et al. (2023), ESKOM power outages and unstable energy supplies are often encountered in rural areas, which negatively affects students' capacity to regularly participate in online learning activities. Due to a lack of online learning support, students are also somewhat prone to getting distracted, losing focus, or missing deadlines (Luburić et al., 2021).

According to a study by Norman et al. (2022) and Raes, et al. (2020), a large number of students, especially those from underprivileged backgrounds, do not have the necessary digital literacy skills to use digital resources and navigate online learning environments. Software licences, digital textbooks, and other materials that might not be easily accessible or reasonably priced are among the extra expenses that come with online learning, in addition to internet connection and devices (Haleem et al., 2022). According to Krishnan et al. (2020), students whose first language is not English may find it difficult to access online learning resources in languages other than English. South Africa is a multilingual country, with 11 official languages. A host of researchers (Asfour et al., 2020; Charamba, 2020; Kepe, 2022; Stroud & Kerfoot, 2021; Yafele, 2024; & Yafele, 2021) unanimously agree that language barriers can pose significant challenges for students accessing online resources, especially if materials are predominantly available in English, which may not be their first language. Providing resources in multiple languages can help address this issue (Stroud & Kerfoot, 2021). Transitioning from traditional face-to-face teaching to online learning requires significant pedagogical adaptation (Souleles, Laghos & Savva, 2020). According to Archambault, Leary & Rice (2022), many educators lacks the training or resources needed to design effective online courses and engage students in meaningful ways in the online environment. Online learning can be isolating, particularly for students who are already vulnerable or facing additional stressors (Drane, Vernon & O’Shea, 2021). As such, developing universities need to provide adequate social and emotional support services to help students cope with the challenges of online learning and maintain their mental well-being (Huang & Zhang, 2022). Sabrina et al. (2022) indicate that ensuring the integrity of assessments in the online environment can be challenging, particularly in contexts where resources for proctoring or plagiarism detection are limited. Developing robust assessment strategies that promote academic integrity while also being accessible and fair is crucial (Sotiriadou et al., 2020).

4. Research Methodology

The main research question to be answered in this article is

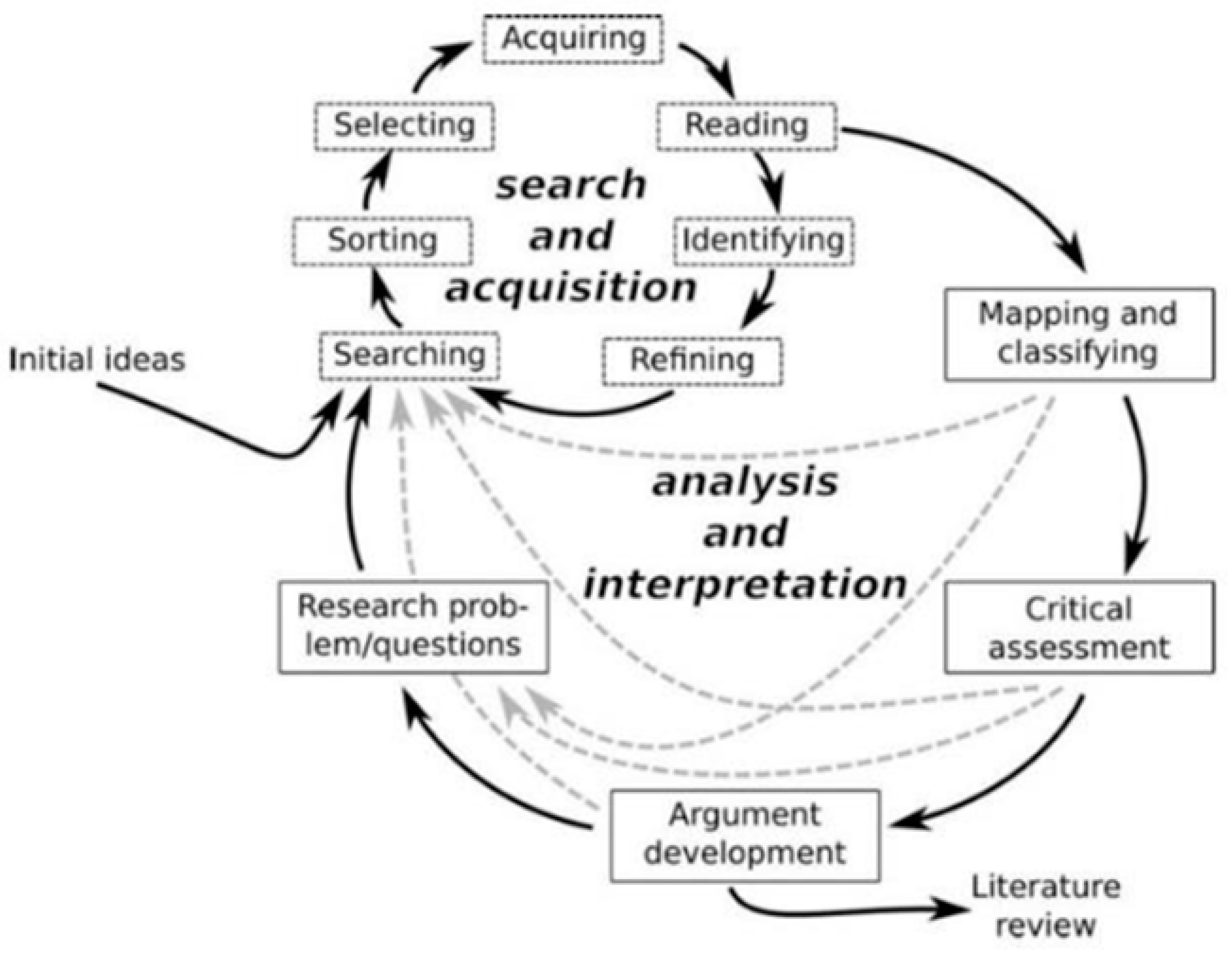

“How does online learning support contribute to student learning experiences at the developing universities in South Africa”?. The hermeneutics framework was adopted to guide the analysis and interpretation of literature and the search for literature. The hermeneutics methodology adopted followed four steps proposed by Boell & Cecez-Kecmanovic (2014) as shown in

Figure 1. These steps include reading, mapping and classifying, critical assessment, and argument development.

The study draws on literature studies that were published by authors on the aspect of online learning support for students learning experiences in the context of South African developing universities. The material used included peer-reviewed journal articles, book chapters, government reports, and theses on “online learning." The research design of this study was a literature review of South African published work from 2000 to 2024. To conduct the literature review, the researcher reviews publications across databases including Google Scholar, Web of Science, and Scopus.

In a process of hermeneutic approach, conducting literature reviews and searches involved the interpretation and understanding of texts in their broader contexts rather than just extracting information. The understanding of texts was done within their historical, cultural, and social contexts. The researcher carefully considered the background and context of each study or piece of literature. Instead of simply summarizing findings, hermeneutics encourages interpretative reading. This helped the study critically analyse texts to uncover underlying meanings, assumptions, and implications. According to the hermeneutic framework, texts converse with the reader. In the context of literature reviews, this entailed figuring out how various texts or studies connect to one another, expanding on earlier findings, or refuting accepted theories. Keep in mind how each study's or work of literature's context affects its conclusions and findings. This entailed taking into account elements including the historical period, geographical location, disciplinary perspective, and theoretical framework. Understand that interpretation is personal and shaped by the researcher's prejudices, experiences, and background. Hermeneutics in this study promoted reflexivity so that these impacts could be recognized and dealt with. An iterative process of reading, interpreting, and re-evaluating texts was considered. This made it possible to comprehend issues more deeply and improve interpretations over time. The author has accumulated a number of years’ experience as a lecturer and possesses this experience in developing universities. So, the ideas emanate from personal observations and real-world context analysis.

5. Review Results

The literature review resulted into five emerging themes and these themes were shown in

Figure 2 using Atlas.ti network diagram to show relationships. The literature analysis and interpretation resulted to five key emerging themes that could be used to inform the approaches aimed at developing online policies, practices, strategies and frameworks for developing universities. The following themes emerged from reviewing the secondary data:

The themes as shown in

Figure 2 are presented in the next section.

6. Analysis and Discussion of Results

Figure 2 presents Atlas.ti network diagram of the codes and themes identified from the topic related to online learning through literature review process. The code related to lack of digital infrastructure that developing universities faces is that one of obsolete facilities and equipment which include outdated laboratory with insufficient equipment such as computers. There are currently problems of determining the scalability in creating ability of developing universities to grow and adapt their infrastructure, resources, and programmes to meet increasing demands and changing needs. Effective scalability has become a crucial aspect for accommodating more students, expanding programmes, and integrating new technologies at developing universities (Matthew, Kazaure & Okafor, 2021). Internet connectivity is linked to unreliability problems which are associated with a lack of access to high-speed broadband infrastructure, relying instead on slower or less reliable connections. The developing universities also need to work with telecommunications providers to extend affordable and reliable broadband access to campuses and surrounding areas in rural villages. Implementing and sustaining digital infrastructure has been complicated by a significant issue with aging infrastructure and subpar physical facilities (Elam, 2020). However, investment in upgrading computer labs, servers, networking equipment, and other ICT infrastructure to support modern digital learning and administrative needs is fundamental. There is also a need to utilize cloud computing services as part of back-up system to reduce the burden of maintaining on-premises infrastructure and improve scalability (Sehgal, Bhatt & Acken, 2020).

According to a study by González-Zamar et al. (2020), ICT policies and strategies are indispensable to higher education institutions because they enable institutions to use technology for research, teaching, learning, and administrative purposes. According to Maphalala and Adigun's (2021), developing universities in South Africa encounter various obstacles while formulating their ICT policies and strategies. For example, developing universities need a strong digital infrastructure that will be responsive through network infrastructure, computer facilities, and high-speed internet access to assist teaching, research, and administration (Huda, 2024). Faloye and Ajayi's (2022) study indicates that issues with digital infrastructure persist in South Africa's developing universities, despite ongoing attempts to give access to technology and digital resources. Therefore, it is important to consider increasing funding specifically earmarked for improving digital infrastructure. There is a dire need for expertise during the development and implementation of ICT policies that will prioritise digital infrastructure development and support initiatives. For instance, sufficient funding is needed for investment in local infrastructure, such as fiber-optic networks, to improve connectivity. The main barriers to the growth of computer labs, data centers, and other digital resources in South African developing universities are a lack of space, electricity, and cooling systems (Mawonde & Togo, 2019). Therefore, the implementation of reliable power backup systems such as generators or solar power will mitigate the impact of frequent power outages on digital operations.

Insufficient funding is linked to a main theme of budget constraints that can limiting to the ability of implementing these systems effectively, potentially compromising the integrity of assessments. There is a great deal of high cost of establishing and maintaining robust internet infrastructure which has created problems for online learning, particularly for developing universities which often have limited budgets. The high cost of software licenses and subscriptions can also be prohibitive for developing universities, limiting access to essential software tools for academic and research purposes. There are other additional high costs that can create limitations to online learning such as students accommodation costs, lack of affordability on tuition fees, costs of data bundles, study material costs (Mukuna & Aloka, 2020). Open-source alternatives may offer cost-effective solutions but may require additional training and support. Developing universities often face budget constraints, limiting their ability to invest in modern digital infrastructure (Nyahodza & Higgs, 2017). Insufficient funding in developing universities is a common issue that contributes immensely to a number of challenges, including outdated equipment, inadequate internet connectivity, and a lack of access to essential software and tools (Adam, 2003; Simamora et al. 2020). A study conducted by Rice and Dunn (2023) suggest that it important to ensure equitable access to online education requires investment in accessibility tools, such as assistive technologies and alternative formats for content. Insufficient funding has created barriers for students with disabilities or those from disadvantaged backgrounds who may not have access to necessary devices or internet connectivity. Developing universities should monitor and maintain the quality of online courses for assessment tools, learning analytics, and continuous improvement processes (Macfadyen et al., 2014). There should be endeavours to ensure reliable online assessments, which require specialized infrastructure and technologies for remote proctoring and exam administration (Serutla, Mwanza & Celik, 2024).

Establishing clear ICT governance structures is always an essential initiative to ensure that ICT investments align with the university's strategic objectives (González-Zamar et al., 2020). This includes defining roles and responsibilities, decision-making processes, and accountability mechanisms. Maphalala and Adigun's (2021) indicate that establishing comprehensive ICT policies and guidelines is essential for promoting responsible and ethical use of technology in student learning. For instance, the developing universities in South Africa lack clear governance frameworks to address issues like acceptable use of digital resources, data privacy, cybersecurity, and intellectual property rights (Elam, 2020). Ensuring the security of ICT systems and data is critical to protecting against cyber threats. Universities need to implement security measures such as firewalls, antivirus software, and data encryption, as well as develop policies and procedures for data protection and incident response (Villegas-Ch, Ortiz-Garcés & Sánchez-Viteri, 2021). Weak cybersecurity measures leave digital infrastructure vulnerable to cyber threats such as malware, phishing attacks, and data breaches (Aslan et al., 2023). In this regard, compliance with relevant regulations and standards should be ensured. Ensuring compliance with data privacy regulations and protecting sensitive information should be a priority in developing universities. Inadequate data governance frameworks and privacy policies may expose institutions to legal and reputational risks. Promoting digital literacy and skills development among students is a key aspect of ICT governance for student learning. Developing universities lack the resources and expertise needed to implement robust cybersecurity protocols and respond effectively to security incidents (Thakur, 2024). Therefore, the ICT governance frameworks should further incorporate performance indicators, metrics, and feedback mechanisms to measure the impact of technology-enabled teaching and learning strategies.

It is crucial to increase the skills of educators and students with ICT tools and technology (Kaur, 2023). Developing universities should strive to provide workshops and training courses that will enhance students' ICT and digital literacy. It's possible that plenty of instructors and students lack the digital literacy skills needed to make the most of digital tools and resources for learning, teaching, and research. Insufficient guidance and assistance regarding digital literacy at developing universities impede the use of technology-based teaching methodologies. A redesign of the curriculum to include courses or modules on digital literacy, online research techniques, and digital communication skills will help integrate ICT skills development across academic fields (Hays & Kammer, 2023). It is of pivotal importance that, firstly, educators at developing universities be funded to improve their ICT competencies by enrolling in extensive training programs that cover topics such as digital assessment tools, learning management system (LMS) usage, and online teaching strategies. Offer seminars and guidance sessions to students in order to acquaint them with digital collaboration tools, online learning environments, and efficient methods for conducting internet research. The ICT-related departments should provide comprehensive online guides, FAQs, and troubleshooting resources to empower users to resolve common technical problems independently (Enakrire, 2019). Furthermore, to enable educators and students to exchange information, resources, and best practices on ICT for online learning, developing universities should establish peer learning networks and communities of practice.

It is imperative to guarantee that ICT services and resources are accessible and inclusive of all students, including those with disabilities, in order to foster equality of opportunity and inclusivity in the classroom (Dipace, 2013). Differences in students' access to technology are a contributing factor to educational inequality, especially in South African developing universities. While certain students could have access to smartphones and personal computers, others might only use the outdated or restricted resources offered by the institution. For students who cannot afford laptops or tablets, developing universities should strive to provide loan equipment or financial assistance. According to West (2015), there should be an increase students' access to dependable internet connectivity in underdeveloped and rural locations by partnering with telecommunications companies or government initiatives. ICT policies and regulations should also prioritise facilitating research activities by giving users access to high-performance computing resources, online research databases, and collaborative tools (Maphalala & Adigun's, 2021). To accommodate students with different language backgrounds, the universities should promote the use of simple language and deliver instructions in many languages (Charamba, 2020). Moreover, provide students with technical support for online learning platforms and digital tools by setting up a dedicated help desk or support staff that is actively involved. It is fundamental to provide academic assistance and guidance for students who might find it difficult to learn online by offering virtual tutoring sessions and mentoring programs (Gregg & Shin, 2021). To support students' mental health and wellbeing while they are learning online, offer online counseling services and wellness resources. Higgins and Maxwell (2021) suggest that the use of Universal Design for Learning (UDL) principles for creating accessible course designs that take into account students' varied learning preferences and skill levels helps to address imbalances.

7. Conclusions

Overall, developing universities in South Africa can benefit greatly from well-designed ICT policies and strategies that are aligned with their institutional goals and priorities. These universities often receive additional government funding and support to improve infrastructure, enhance academic programs, and promote research and development. The developing universities in South Africa play a crucial role in widening access to higher education and addressing historical inequalities in South Africa's education system. Even though they may face numerous challenges, they are integral to the country's efforts towards social and economic development. Governance structures of these universities should prioritise investments in transforming digital infrastructure, educational technology tools, software licenses, training programs, and support services. Monitoring and evaluation mechanisms should be established to assess the effectiveness of ICT initiatives in supporting student learning outcomes. Adequate funding and resource allocation are necessary to support ICT initiatives that enhance student learning outcomes. The ICT governance frameworks in developing universities should support initiatives to integrate technology into the curriculum, provide training opportunities for students, and foster the development of digital competencies relevant to academic and professional success. These initiatives should be iterative and responsive to changing needs and technological advancements. Regular reviews, assessments, and updates to ICT governance frameworks will ensure that developing universities remain relevant and effective in promoting student learning in a rapidly evolving digital landscape. Embracing e-learning technologies will enhance the quality and accessibility of education. Developing universities should develop a rigorous online courses, learning management systems (LMS), and virtual classrooms to support distance learning and blended learning approaches. The collaboration with government agencies, industry partners, and other universities can help developing universities access funding, share best practices, and leverage expertise to enhance their ICT capabilities. Lastly, regular monitoring and evaluation of ICT policies and strategies are essential to assess their effectiveness and identify areas for improvement.

References

- Adam, L. (2003). Information and communication technologies in higher education in Africa: Initiatives and challenges. Journal of Higher Education in Africa/Revue de l'enseignement supérieur en Afrique, 195-221. [CrossRef]

- Agormedah, E. K., Henaku, E. A., Ayite, D. M. K., & Ansah, E. A. (2020). Online learning in higher education during COVID-19 pandemic: A case of Ghana. Journal of Educational Technology and Online Learning, 3(3), 183-210. [CrossRef]

- Alkaabi, A., Qablan, A., Alkatheeri, F., Alnaqbi, A., Alawlaki, M., Alameri, L., & Malhem, B. (2023). Experiences of university teachers with rotational blended learning during the COVID-19 pandemic: A qualitative case study. Plos one, 18(10), e0292796. [CrossRef]

- Archer, S. (2017). The function of a university in South Africa: Part 1. South African Journal of Science, 113(5-6), 1-6.

- Archambault, L., Leary, H., & Rice, K. (2022). Pillars of online pedagogy: A framework for teaching in online learning environments. Educational Psychologist, 57(3), 178-191. [CrossRef]

- Aruleba, K., & Jere, N. (2022). Exploring digital transforming challenges in rural areas of South Africa through a systematic review of empirical studies. Scientific African, 16, e01190. [CrossRef]

- Asfour, F., Ndabula, Y., Chakona, G., Mason, P., & Oluwole, D. O. (2020). Using Translanguaging in Higher Education to Empower Students' Voices and Enable Epistemological Becoming. Alternation. [CrossRef]

- Aslan, Ö., Aktuğ, S. S., Ozkan-Okay, M., Yilmaz, A. A., & Akin, E. (2023). A comprehensive review of cyber security vulnerabilities, threats, attacks, and solutions. Electronics, 12(6), 1333. [CrossRef]

- Azionya, C. M., & Nhedzi, A. (2021). The digital divide and higher education challenge with emergency online learning: Analysis of tweets in the wake of the COVID-19 lockdown. Turkish Online Journal of Distance Education, 22(4), 164-182. [CrossRef]

- Badat, S., & Sayed, Y. (2014). Post-1994 South African education: The challenge of social justice. The ANNALS of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, 652(1), 127-148.

- Banerjee, M. (2022). The digital divide and smartphone reliance for disadvantaged students in higher education. Journal of Systemics, Cybernetics and Informatics, 20(3), 31-39. [CrossRef]

- Bagarukayo, E., & Kalema, B. (2015). Evaluation of elearning usage in South African universities: A critical review. International Journal of Education and Development using ICT, 11(2).

- Boell, S. K., & Cecez-Kecmanovic, D. (2014). A hermeneutic approach for conducting literature reviews and literature searches. Communications of the Association for information Systems, 34(1), 12. [CrossRef]

- Charamba, E. (2020). Translanguaging in a multilingual class: a study of the relation between students’ languages and epistemological access in science. International Journal of Science Education, 42(11), 1779-1798. [CrossRef]

- Chisango, G., & Marongwe, N. (2021). The digital divide at three disadvantaged secondary schools in Gauteng, South Africa. Journal of Education (University of KwaZulu-Natal), (82), 149-165. [CrossRef]

- Dipace, A. (2013). Inclusive education: strategies and opportunities for preparing teachers through the use of ICT in the Italian compulsory school. Journal of e-Learning and Knowledge Society, 9(2).

- Dube, B. (2020). Rural online learning in the context of COVID 19 in South Africa: Evoking an inclusive education approach. REMIE: Multidisciplinary Journal of Educational Research, 10(2), 135-157. [CrossRef]

- Drane, C. F., Vernon, L., & O’Shea, S. (2021). Vulnerable learners in the age of COVID-19: A scoping review. The Australian Educational Researcher, 48(4), 585-604. [CrossRef]

- Elam, A. G. (2020). The obstacles that smaller healthcare facilities face from subpar cybersecurity (Master's thesis, Utica College).

- Enakrire, R. T. (2019). ICT-related training and support Programmes for information professionals. Education and Information technologies, 24(6), 3269-3287. [CrossRef]

- Faloye, S. T., & Ajayi, N. (2022). Understanding the impact of the digital divide on South African students in higher educational institutions. African Journal of Science, Technology, Innovation and Development, 14(7), 1734-1744. [CrossRef]

- Gonzales, A. L., McCrory Calarco, J., & Lynch, T. (2020). Technology problems and student achievement gaps: A validation and extension of the technology maintenance construct. Communication research, 47(5), 750-770. [CrossRef]

- González-Zamar, M. D., Abad-Segura, E., López-Meneses, E., & Gómez-Galán, J. (2020). Managing ICT for sustainable education: Research analysis in the context of higher education. Sustainability, 12(19), 8254. [CrossRef]

- Gregg, D., & Shin, S. J. (2021). Why We Will Not Return to Exclusively Face-to-Face Tutoring Post-COVID: Improving Student Engagement Through Technology. Learning Assistance Review, 26(2), 53-79.

- Hall, M. (2015). Institutional culture of mergers and alliances in South Africa. Mergers and alliances in higher education: International practice and emerging opportunities, 145-173.

- Haleem, A., Javaid, M., Qadri, M. A., & Suman, R. (2022). Understanding the role of digital technologies in education: A review. Sustainable operations and computers, 3, 275-285. [CrossRef]

- Hamilton, B. (2022). Integrating technology in the classroom: Tools to meet the needs of every student. International Society for Technology in Education.

- Hays, L., & Kammer, J. (Eds.). (2023). Integrating digital literacy in the disciplines. Taylor & Francis.

- Higgins, A. K., & Maxwell, A. E. (2021). Universal Design for Learning in the geosciences for access and equity in our classrooms. The Journal of Applied Instructional Design, 10(1), 69-83.

- Hlatshwayo, M. (2022). Online learning during the South African COVID-19 lockdown: University students left to their own devices. Education as Change, 26(1), 1-23. [CrossRef]

- Huang, L., & Zhang, T. (2022). Perceived social support, psychological capital, and subjective well-being among college students in the context of online learning during the COVID-19 pandemic. The Asia-Pacific Education Researcher, 31(5), 563-574. [CrossRef]

- Huda, M. (2024). Between accessibility and adaptability of digital platform: investigating learners' perspectives on digital learning infrastructure. Higher education, skills and work-based learning, 14(1), 1-21. [CrossRef]

- Johnson, D. L. (2013). Re-architecting internet access and wireless networks for rural developing regions. University of California, Santa Barbara.

- Kaur, K. (2023). Teaching and Learning with ICT Tools: Issues and Challenges. International Journal on Cybernetics & Informatics. [CrossRef]

- Kawuryan, S. P., Sayuti, S. A., & Dwiningrum, S. I. A. (2021). Teachers Quality and Educational Equality Achievements in Indonesia. International Journal of Instruction, 14(2), 811-830. [CrossRef]

- Kepe, M. H. (2022). The English Language Limits Me! Connecting Third Space to Curriculum Transformation in a South African University, Expanding Epistemological Landscapes?. Rupkatha Journal on Interdisciplinary Studies in Humanities, 14(4). [CrossRef]

- Kreutzer, T. (2009). Generation mobile: online and digital media usage on mobile phones among low-income urban youth in South Africa. Retrieved on March, 30(2009), 903-920.

- Krishnan, I. A., Ching, H. S., Ramalingam, S., Maruthai, E., Kandasamy, P., De Mello, G., ... & Ling, W. W. (2020). Challenges of learning English in 21st century: Online vs. traditional during Covid-19. Malaysian Journal of Social Sciences and Humanities (MJSSH), 5(9), 1-15.

- Landa, N., Zhou, S., & Marongwe, N. (2021). Education in emergencies: Lessons from COVID-19 in South Africa. International Review of Education, 67(1), 167-183. [CrossRef]

- Luburić, N., Slivka, J., Sladić, G., & Milosavljević, G. (2021). The challenges of migrating an active learning classroom online in a crisis. Computer applications in engineering education, 29(6), 1617-1641. [CrossRef]

- Macfadyen, L. P., Dawson, S., Pardo, A., & Gašević, D. (2014). Embracing big data in complex educational systems: The learning analytics imperative and the policy challenge. Research & Practice in Assessment, 9, 17-28.

- Maphalala, M. C., & Adigun, O. T. (2021). Academics' Experience of Implementing E-Learning in a South African Higher Education Institution. International Journal of Higher Education, 10(1), 1-13. [CrossRef]

- Matthew, U. O., Kazaure, J. S., & Okafor, N. U. (2021). Contemporary development in E-Learning education, cloud computing technology & internet of things. EAI Endorsed Transactions on Cloud Systems, 7(20), e3-e3. [CrossRef]

- Mawonde, A., & Togo, M. (2019). Implementation of SDGs at the university of South Africa. International Journal of Sustainability in Higher Education, 20(5), 932-950.

- Mbaleki, C., Elegbeleye, F. A., Esan, O. A., & Rabotapi, T. (2023). Power supply rationing in an era of e-learning: evidence from the rural university. EUREKA: Social and Humanities, (6), 3-12. [CrossRef]

- Mishra, L., Gupta, T., & Shree, A. (2020). Online teaching-learning in higher education during lockdown period of COVID-19 pandemic. International journal of educational research open, 1, 100012. [CrossRef]

- Mouton, N., Louw, G. P., & Strydom, G. L. (2013). Restructuring and mergers of the South African post-apartheid tertiary system (1994-2011): A critical analysis.

- Mpungose, C. B. (2020). Emergent transition from face-to-face to online learning in a South African University in the context of the Coronavirus pandemic. Humanities and social sciences communications, 7(1), 1-9. [CrossRef]

- Mukuna, K. R., & Aloka, P. J. (2020). Exploring educators' challenges of online learning in COVID-19 at a rural school, South Africa. International Journal of Learning, Teaching and Educational Research, 19(10), 134-149.

- Nguyen, T. D., Kramer, J. W., & Evans, B. J. (2019). The effects of grant aid on student persistence and degree attainment: A systematic review and meta-analysis of the causal evidence. Review of educational research, 89(6), 831-874. [CrossRef]

- Norman, H., Adnan, N. H., Nordin, N., Ally, M., & Tsinakos, A. (2022). The educational digital divide for vulnerable students in the pandemic: Towards the new agenda 2030. Sustainability, 14(16), 10332. [CrossRef]

- Nyahodza, L., & Higgs, R. (2017). Towards bridging the digital divide in post-apartheid South Africa: a case of a historically disadvantaged university in Cape Town. South African Journal of Libraries and Information Science, 83(1), 39-48. [CrossRef]

- Raes, A., Vanneste, P., Pieters, M., Windey, I., Van Den Noortgate, W., & Depaepe, F. (2020). Learning and instruction in the hybrid virtual classroom: An investigation of students’ engagement and the effect of quizzes. Computers & Education, 143, 103682. [CrossRef]

- Rapanta, C., Botturi, L., Goodyear, P., Guàrdia, L., & Koole, M. (2020). Online university teaching during and after the Covid-19 crisis: Refocusing teacher presence and learning activity. Postdigital science and education, 2, 923-945. [CrossRef]

- Rensburg, I. (2020). Transformation of higher education in South Africa, 1995–2016: Current limitations and future possibilities. In Transforming Universities in South Africa (pp. 20-38). Brill.

- Rice, M. F., & Dunn, M. (Eds.). (2023). Inclusive online and distance education for learners with dis/abilities: Promoting accessibility and equity. Taylor & Francis.

- Roddy, C., Amiet, D. L., Chung, J., Holt, C., Shaw, L., McKenzie, S., ... & Mundy, M. E. (2017, November). Applying best practice online learning, teaching, and support to intensive online environments: An integrative review. In Frontiers in Education (Vol. 2, p. 59). Frontiers Media SA. [CrossRef]

- Sabrina, F., Azad, S., Sohail, S., & Thakur, S. (2022). Ensuring academic integrity in online assessments: a literature review and recommendations. [CrossRef]

- Sehgal, N. K., Bhatt, P. C. P., & Acken, J. M. (2020). Cloud computing with security and scalability. Springer, https://link. springer. com/book/10.1007/978-3-031-07242-0.

- Serutla, L., Mwanza, A., & Celik, T. (2024). Online Assessments in a Changing Education Landscape. In Reimagining Education-The Role of E-Learning, Creativity, and Technology in the Post-Pandemic Era. IntechOpen.

- Siemens, G., Gašević, D., & Dawson, S. (2015). Preparing for the digital university: A review of the history and current state of distance, blended and online learning.

- Simelane, T. (2021). Uj Undergraduate Students’ Experiences of Online Learning: Lessons from the COVID-19 Pandemic (Master's thesis, University of Johannesburg (South Africa)).

- Simamora, R. M., De Fretes, D., Purba, E. D., & Pasaribu, D. (2020). Practices, challenges, and prospects of online learning during Covid-19 pandemic in higher education: Lecturer perspectives. Studies in Learning and Teaching, 1(3), 185-208. [CrossRef]

- Souleles, N., Laghos, A., & Savva, S. (2020). From face-to-face to online: assessing the effectiveness of the rapid transition of higher education due to the coronavirus outbreak. In ICERI2020 proceedings (pp. 927-934). IATED.

- Sotiriadou, P., Logan, D., Daly, A., & Guest, R. (2020). The role of authentic assessment to preserve academic integrity and promote skill development and employability. Studies in Higher Education, 45(11), 2132-2148. [CrossRef]

- Stroud, C., & Kerfoot, C. (2021). Decolonizing higher education: Multilingualism, linguistic citizenship and epistemic justice. Language and decoloniality in higher education: Reclaiming voices from the South, 19-46.

- Takalani, T. (2008). Barriers to e-learning amongst postgraduate black students in higher education in South Africa (Doctoral dissertation, Stellenbosch: Stellenbosch University).

- Tate, T., & Warschauer, M. (2022). Equity in online learning. Educational Psychologist, 57(3), 192-206. [CrossRef]

- Thakur, M. (2024). Cyber security threats and countermeasures in digital age. Journal of Applied Science and Education (JASE), 4(1), 1-20. [CrossRef]

- Trahar, S., Timmis, S., Lucas, L., & Naidoo, K. (2020). Rurality and access to higher education. Compare: A Journal of Comparative and International Education, 50(7), 929-942.

- Villegas-Ch, W., Ortiz-Garcés, I., & Sánchez-Viteri, S. (2021). Proposal for an implementation guide for a computer security incident response team on a university campus. Computers, 10(8), 102. [CrossRef]

- Walker, M. (2020). The well-being of South African university students from low-income households. Oxford Development Studies, 48(1), 56-69. [CrossRef]

- West, D. M. (2015). Digital divide: Improving Internet access in the developing world through affordable services and diverse content. Center for Technology Innovation at Brookings, 1, 30.

- Yafele, S. (2024). Exploring views on praxis possibilities of multilingualism in university literacy pedagogies. Reading & Writing-Journal of the Literacy Association of South Africa, 15(1), 451. [CrossRef]

- Yafele, S. (2021). Translanguaging for academic reading at a South African university. Southern African Linguistics and Applied Language Studies, 39(4), 404-424. [CrossRef]

- Yakobi, S., Yakobi, K., Lose, T., & Kwahene, F. (2022). E-Assessment Implementation and Implications for the Success of Historically Disadvantaged Institutions (HDIs) in South Africa. Journal of Educational Studies, 21(4), 110-122.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).