Submitted:

05 August 2024

Posted:

07 August 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Material and Methods

Animals

Oestrus Detection and Insemination

Hormone Analyses

Experimental Design

Experiment 1. Use of Triptorelin in Sows 96 Hours after Weaning with Sign of Estrus

Experiment 2. Effect of Day of the Onset of the Estrus on Reproductive and Economic Impact of Triptorelin Treatment

| Group | N | Triptorelin 96 h after weaning |

Estrus onset before 120 h after weaning |

Artificial insemination |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control | 390 | no | yes | 2-3 (0 and 24 h, 0,24,48 h) after onset sign estrus |

| Control late estrus | 25 | no | later | 2-3 (0 and 24 h, 0,24,48 h) after onset sign estrus |

| Triptorelin | 418 | yes | yes | 1 (24 h) with sign of estrus |

| Triptorelin late estrus | 24 | yes | later | 2 (0.24 h) after onset sign estrus |

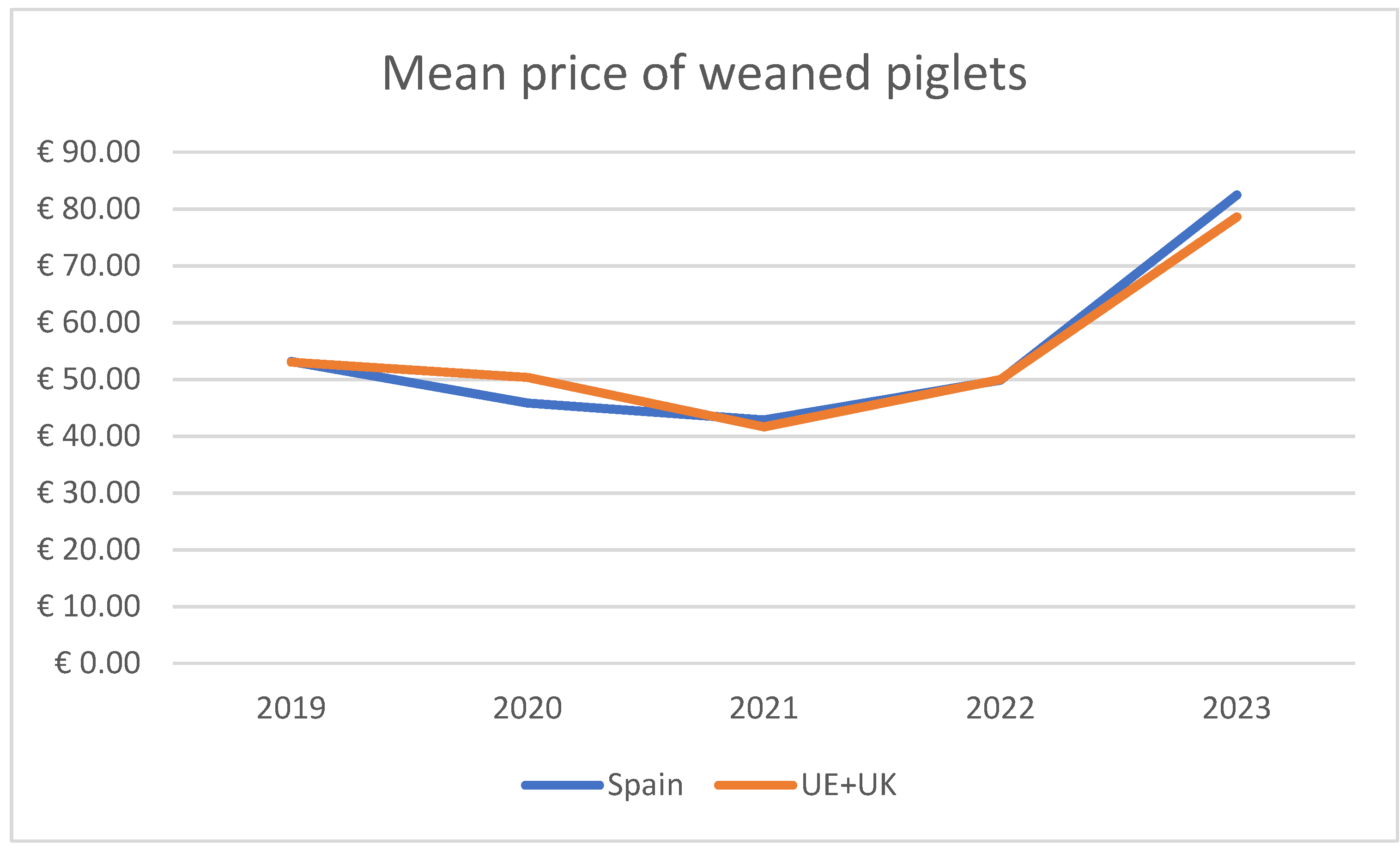

Experiment 3. Economic Impact Estimation

Calculation of AI Costs

Statistical Analysis

3. Results

Experiment 1. Use of Triptorelin in Sows 96 Hours after Weaning with Sign of Oestrus

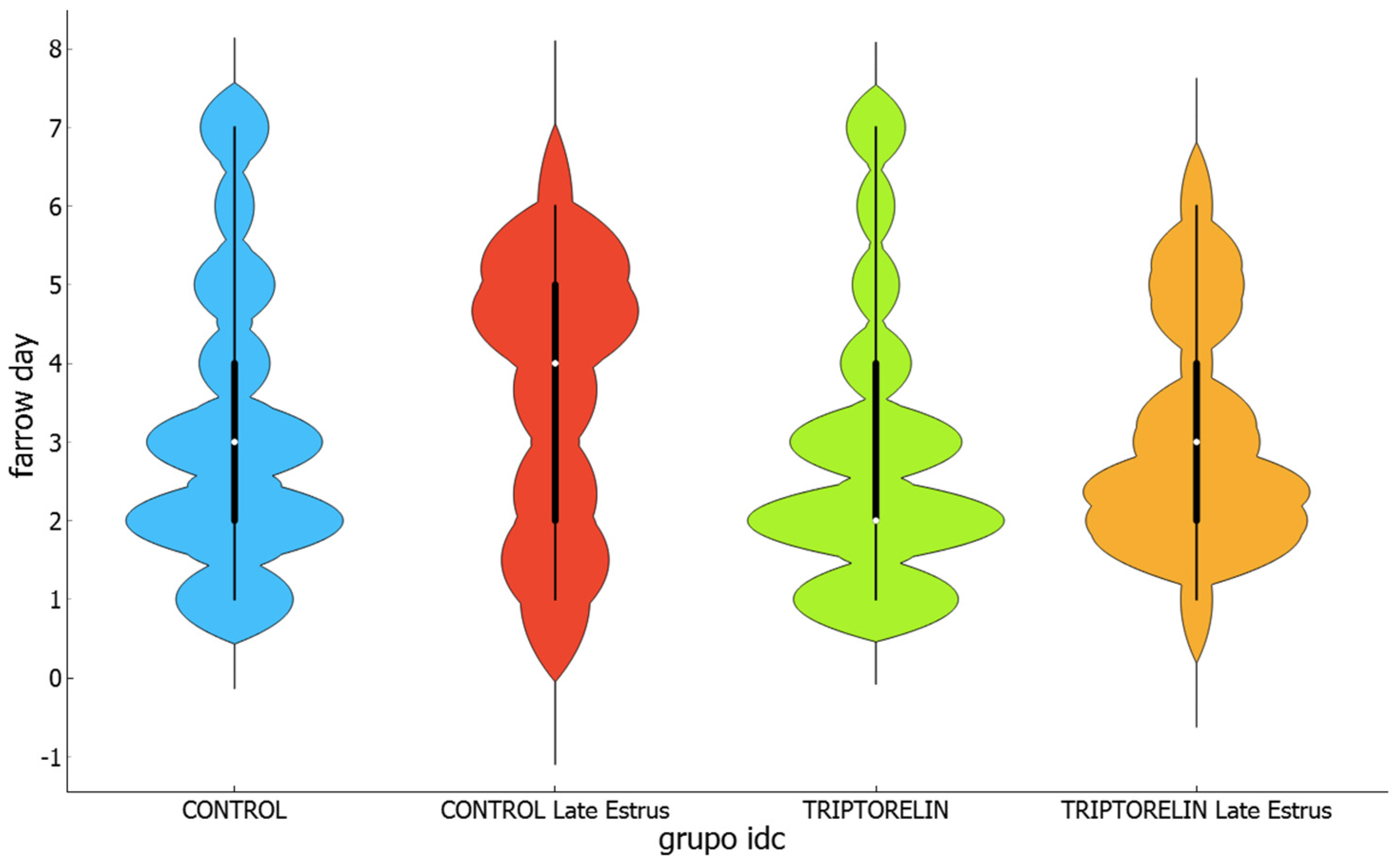

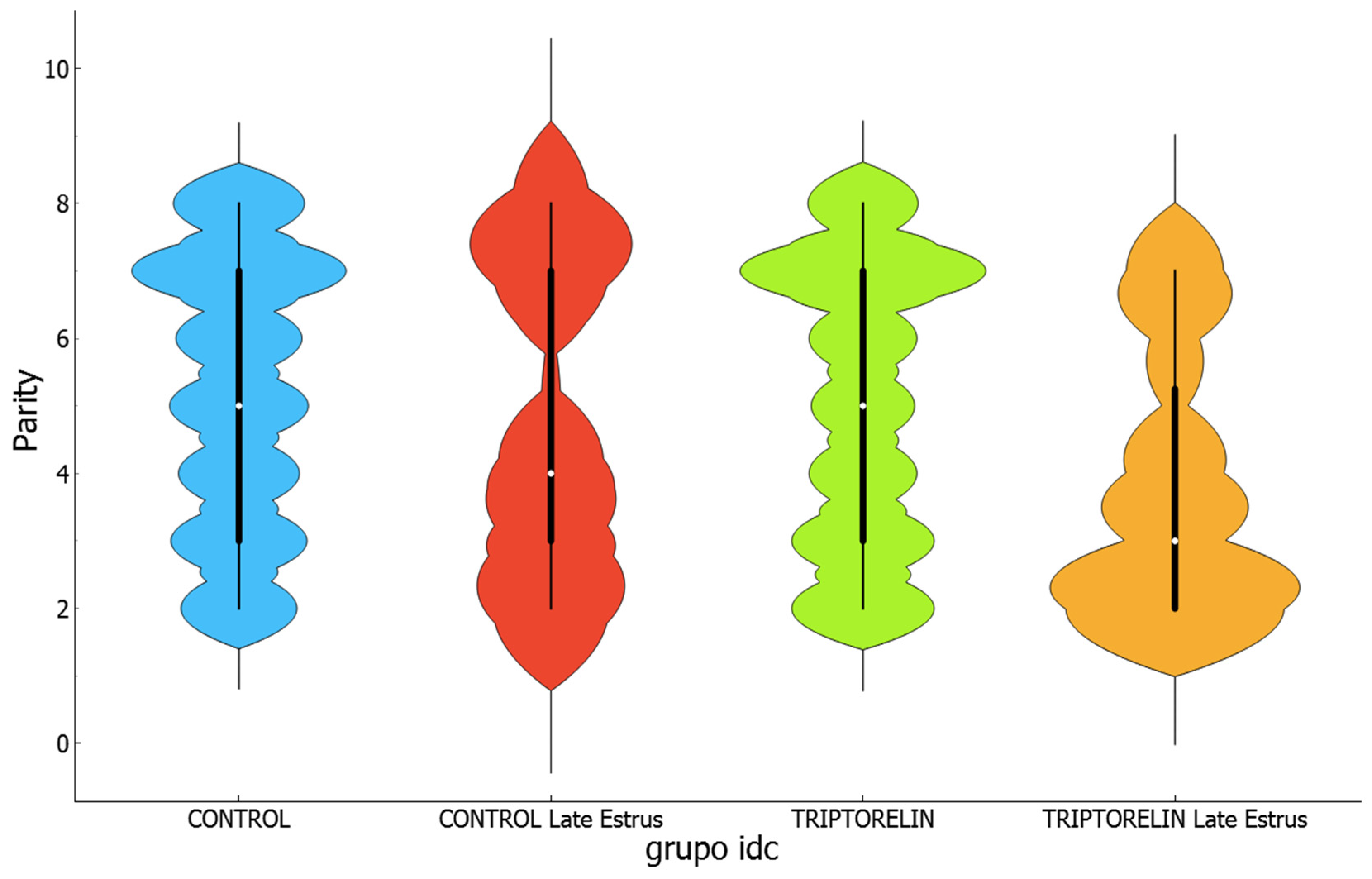

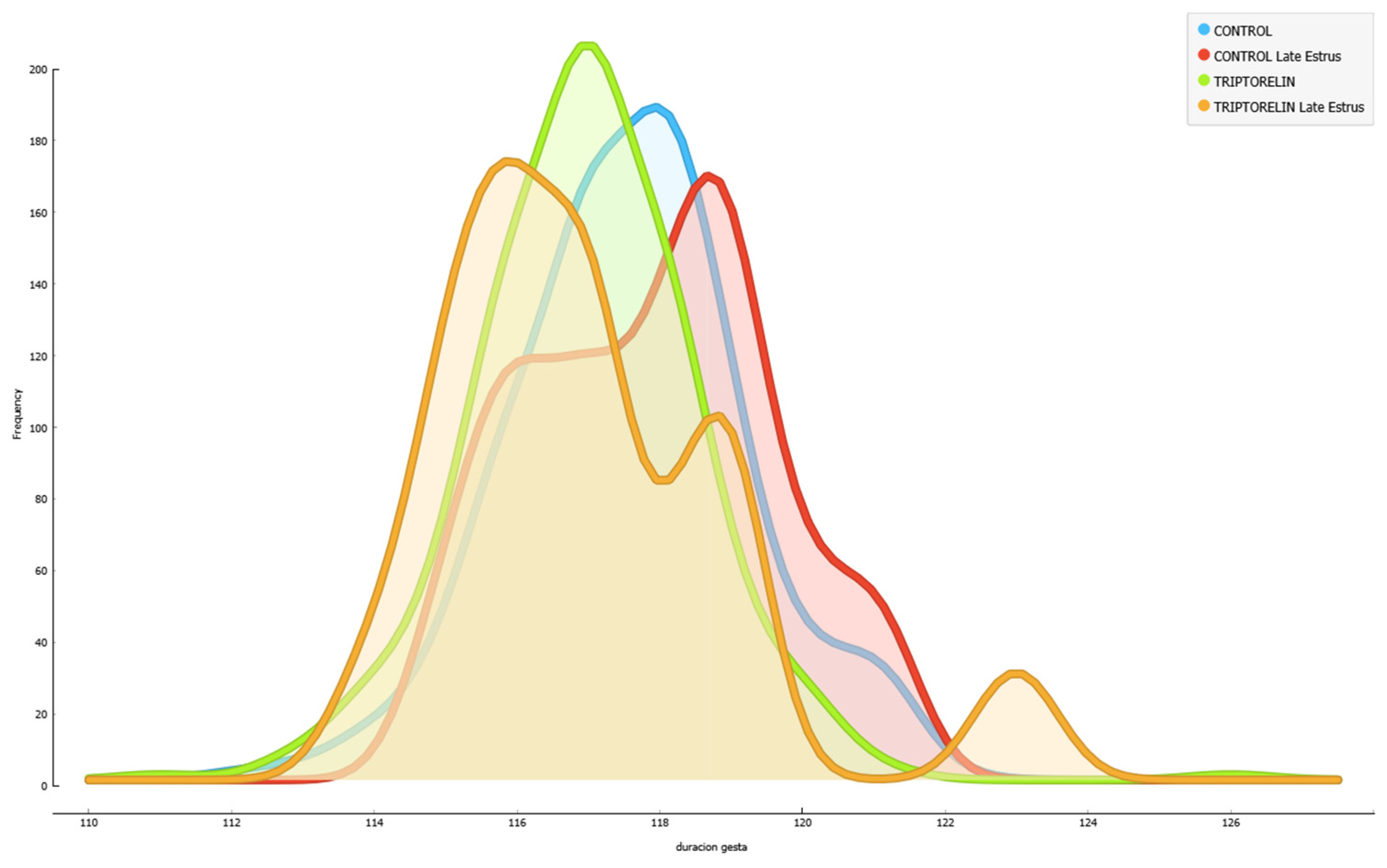

Experiment 2. Effect of Day of Estrus Onset on Reproductive and Economic Impact of Triptorelin Treatment

Experiment 3. Economic IMPACT estimation

4. Discussion

References

- Falceto, M.V.; Suarez-Usbeck, A.; Tejedor, M.T.; Ausejo, R.; Garrido, A.M.; Mitjana, O. GnRH agonists: Updating fixed-time artificial insemination protocols in sows. Reprod. Domes. Anim. 2023, 58, 571-582. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weitze, K.F.; Wagner-Rietschel, H.; Waberski, D.; Richter, L.; Krieter, J. The Onset of Heat after Weaning, Heat Duration, and Ovulation as Major Factors in AI Timing in Sows. Reprod. Domest. Anim. 2007, 29, 433-443. [CrossRef]

- Poleze, E.; Bernardi, M.L.; Amaral Filha, W.S.; Wentz, I.; Bortolozzo, F.P. Consequences of variation in weaning-to-estrus interval on reproductive performance of swine females. Livestock Science 2006, 103, 124-130. [CrossRef]

- Kemp, B.; Soede, N.M. Relationship of weaning-to-estrus interval to timing of ovulation and fertilization in sows. J Anim Sci 1996, 74, 944-949. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Knox, R.V. Recent advancements in the hormonal stimulation of ovulation in swine. Veterinary medicine (Auckland, N.Z.) 2015, 6, 309-320. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schally, A.V.; Coy, D.H.; Arimura, A. LH-RH agonists and antagonists. Int. J. Gynaecol. Obstet. 1980, 18, 318-324. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- NobelPrice.org. The Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine 1977. Available online: https://www.nobelprize.org/prizes/medicine/1977/summary/ (accessed on Fri. 15 Mar 2024. ).

- Stewart, K.R.; Flowers, W.L.; Rampacek, G.B.; Greger, D.L.; Swanson, M.E.; Hafs, H.D. Endocrine, ovulatory and reproductive characteristics of sows treated with an intravaginal GnRH agonist. Anim. Reprod. Sci. 2010, 120, 112-119. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Z.; Liu, B.S.; Wang, X.Y.; Peng, J.L.; Huang, X.Q.; Tian, H.; Wei, Q.H.; Wang, L.Q. Effects of fixed-time artificial insemination using triptorelin on the reproductive performance of pigs: a meta-analysis. Animal 2020, 14, 1481-1492. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Knox, R.V.; Taibl, J.N.; Breen, S.M.; Swanson, M.E.; Webel, S.K. Effects of altering the dose and timing of triptorelin when given as an intravaginal gel for advancing and synchronizing ovulation in weaned sows. Theriogenology 2014, 82, 379-386. [CrossRef]

- Knox, R.V.; Esparza-Harris, K.C.; Johnston, M.E.; Webel, S.K. Effect of numbers of sperm and timing of a single, post-cervical insemination on the fertility of weaned sows treated with OvuGel(®). Theriogenology 2017, 92, 197-203. [CrossRef]

- Alonso-Spilsbury, M.; Ramírez, R.; M, G.-L.; Mota-Rojas, D.; Trujillo, M. Piglet Survival in Early Lactation: A Review. Journal of Animal and Veterinary Advances 2007, 6.

- Koketsu, Y.; Iida, R.; Pineiro, C. Five risk factors and their interactions of probability for a sow in breeding herds having a piglet death during days 0-1, 2-8 and 9-28 days of lactation. Porcine Health Manag 2021, 7, 50. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tucker, B.S.; Craig, J.R.; Morrison, R.S.; Smits, R.J.; Kirkwood, R.N. Piglet Viability: A Review of Identification and Pre-Weaning Management Strategies. Animals (Basel) 2021, 11. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harper, J.; Bunter, K.L. Review: Improving pig survival with a focus on birthweight: a practical breeding perspective. animal 2023, 100914. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lamberson, W.R.; Safranski, T.J. A model for economic comparison of swine insemination programs. Theriogenology 2000, 54, 799-807. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gonzalez-Pena, D.; Knox, R.V.; Rodriguez-Zas, S.L. Contribution of semen trait selection, artificial insemination technique, and semen dose to the profitability of pig production systems: A simulation study. Theriogenology 2016, 85, 335-344. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hoste, R.; Benus, M. International Comparison of Pig Production Costs 2022: Results of InterPIG; Wageningen Economic Research: 2023.

- Suárez-Usbeck, A.; Mitjana, O.; Tejedor, M.T.; Bonastre, C.; Moll, D.; Coll, J.; Ballester, C.; Falceto, M. Post-cervical compared with cervical insemination in gilts: Reproductive variable assessments. Anim. Reprod. Sci. 2019, 211, 106207. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hernandez-Caravaca, I.; Izquierdo-Rico, M.J.; Matas, C.; Carvajal, J.A.; Vieira, L.; Abril, D.; Soriano-Ubeda, C.; Garcia-Vazquez, F.A. Reproductive performance and backflow study in cervical and post-cervical artificial insemination in sows. Anim. Reprod. Sci. 2012, 136, 14-22. [CrossRef]

- Koketsu, Y.; Tani, S.; Iida, R. Factors for improving reproductive performance of sows and herd productivity in commercial breeding herds. Porcine Health Manag 2017, 3, 1. [CrossRef]

- Ulguim, R.D.R.; Will, K.J.; Mellagi, A.P.; Bortolozzo, F.P. Does a single fixed-time insemination in weaned sows affect gestation and lactation length, and piglet performance during lactation compared with multiple insemination protocols in a commercial production setting? Anim. Reprod. Sci. 2022, 247, 107072. [CrossRef]

- Dillard, D.S.; Flowers, W.L. Reproductive performance of sows associated with single, fixed-time insemination programs in commercial farms based on either average herd weaning-to-estrus intervals or postweaning estrous activity. Applied Animal Science 2020, 36, 100-107. [CrossRef]

- Knox, R.V.; Willenburg, K.L.; Rodriguez-Zas, S.L.; Greger, D.L.; Hafs, H.D.; Swanson, M.E. Synchronization of ovulation and fertility in weaned sows treated with intravaginal triptorelin is influenced by timing of administration and follicle size. Theriogenology 2011, 75, 308-319. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hunter, R.H.F. The effects of delayed insemination on fertilization and early cleavage in the pig. J. Reprod. Fertil. 1967, 13, 133-147. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Soede, N.M.; Wetzels, C.C.; Zondag, W.; de Koning, M.A.; Kemp, B. Effects of time of insemination relative to ovulation, as determined by ultrasonography, on fertilization rate and accessory sperm count in sows. J. Reprod. Fertil. 1995, 104, 99-106. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Soede, N.M.; Nissen, A.K.; Kemp, B. Timing of insemination relative to ovulation in pigs: Effects on sex ratio of offspring. Theriogenology 2000, 53, 1003-1011. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Knox, R.V.; Stewart, K.R.; Flowers, W.L.; Swanson, M.E.; Webel, S.K.; Kraeling, R.R. Design and biological effects of a vaginally administered gel containing the GnRH agonist, triptorelin, for synchronizing ovulation in swine. Theriogenology 2018, 112, 44-52. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Broekhuijse, M.L.; Gaustad, A.H.; Bolarin Guillen, A.; Knol, E.F. Efficient Boar Semen Production and Genetic Contribution: The Impact of Low-Dose Artificial Insemination on Fertility. Reprod. Domes. Anim. 2015, 50 Suppl 2, 103-109. [CrossRef]

- Flowers, W.L.; Alhusen, H.D. Reproductive performance and estimates of labor requirements associated with combinations of artificial insemination and natural service in swine. J Anim Sci 1992, 70, 615-621. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gonzalez-Pena, D.; Knox, R.V.; Pettigrew, J.; Rodriguez-Zas, S.L. Impact of pig insemination technique and semen preparation on profitability. J Anim Sci 2014, 92, 72-84. [CrossRef]

- Rodgers, J.C.; Bird, S.L.; Larson, J.E.; Dilorenzo, N.; Dahlen, C.R.; DiCostanzo, A.; Lamb, G.C. An economic evaluation of estrous synchronization and timed artificial insemination in suckled beef cows1. Journal of Animal Science 2012, 90, 4055-4062. [CrossRef]

- Holyoake, P.K.; Dial, G.D.; Trigg, T.; King, V.L. Reducing pig mortality through supervision during the perinatal period. J Anim Sci 1995, 73, 3543-3551. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kraeling, R.R.; Webel, S.K. Current strategies for reproductive management of gilts and sows in North America. J Anim Sci Biotechnol 2015, 6, 3. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Group | N | Estrous 96 h post weaning |

Triptorelin 96 h Post weaning |

AI 96 h post weaning |

Estrous 120 h post weaning |

AI 120 h post weaning |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CONTROL | 16 | + | - | + | + | + |

| TRIPTORELIN | 33 | + | + | - | + | + |

| TRIPTORELIN NO ESTRUS | 6 | - | + | - | - | + |

| n | Parity |

Previous lactation Length |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CONTROL | 16 | 4,13±0.26a | 27,31±1.23 | |

| TRIPTORELIN | 33 | 3,88±0.19a | 27,61±1.25 | |

| TRIPTORELIN NO ESTRUS | 6 | 3,00±0.26b | 25,67±1.76 | |

| P value | 0.062 | 0.664 |

| n | Farrowing rate (%) | Gestation length (days) | Live born | Dead born | Total piglets born | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CONTROL | 14 | 87.50±8.54a | 117,14±0,29 | 18.07±0.68 | 1,14±0.25 | 19,21±0.67 |

| TRIPTORELIN | 33 | 100a | 116.±30±0.26 | 16.30±0.75 | 1,91±0.52 | 18,21±0.69 |

| TRIPTORELIN NO ESTRUS | 3 | 50±22.36b | 117±1.73 | 14.33±1.86 | 1,67±1.67 | 16,00±1.53 |

| P value | <0.001 | 0.220 | 0.195 | 0.777 | 0.269 |

| Estrogen 96h after weaning | Estrogen 120 h after weaning |

Progesterone 96h after weaning |

Progesterone 120 h after weaning |

Ratio E/P 96h after weaning |

Ratio E/P 120 h after weaning |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control (n=15) |

21.06±3.38 | 8.81±1.77 | 0.16±0.03 | 0.26±0.06 | 161.95±25.53 | 97.98±39.63 |

| TRIPTORELIN (n=14) | 28.12±4.17 | 7.09±1.90 | 0.22±0.06 | 0.33±0.09 | 206.83±49.29 | 33±98±12.65 |

| p-value | 0.278 | 0.531 | 0.306 | 0.486 | 0.417 | 0.207 |

| Parity (n) |

Previous lactation length (n) |

|

|---|---|---|

| CONTROL | 5.21±0.10 a (390) | 25.96±0.33 (389) |

| CONTROL late estrus | 4.80±0.47 ab (25) | 26.56±1.03 (25) |

| TRIPTORELIN | 5.11±0.10 a (418) | 26.11±0.25 (418) |

| TRIPTORELIN late estrus | 3.79±0.39 b (24) | 27.63±1.14 (24) |

| P value | 0.009 | 0.190 |

| Days start oestrus | Weaning insemination interval (days) | Number of AI |

Pregnancy rate (%) | Gestation length | Farrowing rate | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control | 4.50±0.03a (388) | 4.50±0.03a (388) | 2.14±0.02a (395) | 92.04±1.35 (402) | 117.60±0.09a (315) | 85.83±1.82 (367)a |

| Control late estrus | 6.31±1.21b (26) | 6.31±1.21b (26) | 2.12±0.06 a (26) | 88.46±6.39 (26) | 117.92±0.51a(12) | 66.67±11.43 (18)b |

| Triptorelin | 4.52±0.25a (421) | 5.00c (421) | 1.00 b (421) | 93.16±1.23 (424) | 116.97±0.08b (341) | 86.40±1.72 (397)a |

| Triptorelin late estrus | 8.09±0.85c (23) | 8.09±0.85b (23) | 2.00 a (24) | 83.33±7.77 (24) | 117.00±0.52ab (17) | 77.27±9.14 (22)ab |

| P value | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.296 | <0.001 | 0.085 |

| n | Live born | Dead born | Total piglets born | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CONTROL | 315 | 15.42±0.21 | 1.78±0.08 | 17.19±0.20 |

| Control late | 12 | 14.58±1.41 | 2±0.28 | 16.58±1.61 |

| TRIPTORELIN | 341 | 15.60±0.22 | 1.75±0.07 | 17.36±0.22 |

| TRIPTORELIN late OESTRUS |

17 | 14.65±0.82 | 1.94±033 | 16.59±0.85 |

| P value | 0.602 | 0.543 | 0.717 |

| Farrowing rate (%) | Alive born | Alive born*farrowing= Alive born/inseminated sow |

Weaned/inseminated sow (86 % survival) | Commercial 20 kg piglets/inseminate sow (93% survival) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CONTROL | 85,83 | 15,42 | 13,23 | 11,38 | 10,58 |

| Control late estrus | 66,67 | 14,58 | 9,72 | 8,36 | 7,77 |

| TRIPTORELIN | 86,4 | 15,6 | 13,48 | 11,59 | 10,78 |

| TRIPTORELIN late estrus | 77,27 | 14,65 | 11,32 | 9,74 | 9,06 |

| Group | No AIs | Triptorelin cost € | Reproductive cost (6€/AI) | Reproductive cost (8€/AI) | Reproductive cost (10€/AI) | Reproductive cost (12€/AI) | Increased incomes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control | 2,14 | 0 | 12.84 | 17,12 | 21,40 | 25,68 | |

| Control late estrus | 2,12 | 0 | 12.72 | 16,96 | 21,20 | 25,44 | |

| Triptorelin | 1 | 5,5 | 11.5 (-1.34€) |

13,5 (-3.62 €) |

15,50 (-5.9 €) |

17,5 (-8.18 €) |

+10.97 € |

| Triptorelin late estrus |

2 | 5,5 | 17.5 (+4.78€) |

21,5 (+4.54 €) |

25,50 (+4.30€) |

29,5 (+4.06 €) |

+70.20 € |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).